Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

An Empirical Investigation Into The Relationship Between Computer

Transféré par

Valentino ArisDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

An Empirical Investigation Into The Relationship Between Computer

Transféré par

Valentino ArisDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

AN EMPIRICALINVESTIGATIONINTOTHE

RELATIONSHIPBETWEENCOMPUTERSELF-EFFICACY,

ANXIETY,EXPERIENCE,SUPPORTAND USAGE

MARYHELENFAGAN

UnivenityofTexasatTyler,Texas

Tyler,Tens75799

STERNNEILL

UnivenityofWashington,Tacoma

Tacoma,Washington98402

BARBARAROSSWOOLDRIDGE

UnivenityofTampa

Tampa,Florida33606

ABSTRACT

Organizations make significantinvestments in information

technology. However, if individuaJs do not use infonnation

system applications as anticipated, successful implementation

can be hard to achieve. In order to investigatesome key factors

thought to affect an individual's use ofinformation technology.

this study draws 00 Bandura's Social Cognitive Theory (SCl"),

Triandis's Theory of Interpersonal Behavior (TIB). and the

computeranxiety literatUre todevelop itsconceptual model and

research hypotheses. An empirical invcstigation (0...,78) found

support for the majority ofthe hypothcses. As suggcsted by

scr. experience and suppon were positively related to

computer self-efficacy. and computer self-efficacy was

negatively related to anxiety and positively related to usage. As

suggested by TIE. experience was positively related to usage.

Furthermore.. computer anxiety was negatively related to

experience. By providing insight into these imponant

relationships. this research can help funher understanding of

theirroleintheacceptanceanduseof information h.. -chnology.

Keywords: computer self-cfficacy. computer anxiety.

computer experience, computer suppon, Social Cognitive

Theory.TheoryofInterpersonal Behavior

INTRODUCTION

Organizations make significant investments in information

technology(IT). However. if individualsdo not useinfonnation

system applications as anticipated. successful implementation

can be hard to achieve. Since the 1970s, infonnation systems

researchers have investigated a numberoffactors that influence

system usageand success(7, 22,60).andavarietyoftheoretical

and pragmatic explanations have been developed to help

understand and improve the successful deployment of IT.

Research on the factors that influenceinformationsystemsusa.ge

continuestobe thefocusof intensive,ongoingresearch(39.50).

In orderto investigatesomekeyfactorsthoughtto affectan

individual's use ofinformation technology. thjs study draws on

Bandura'sSocial Cognitive Theory (SCr), Triandis'sThcoryof

Interpersonal Behavior (11B), and the computer anxiety

lit.ernlure to develop its conceptual model and research

hypotheses. An empirical invcstiga'ion (n='i78) fouod

significant support for most ofthe hypothcsized relationships

between computer self.-efficacy. anxiety, experience, support

andusage. By combiningkeyconstructsfrom SCTand118into

one conceptual model. along wilh additional key relationships

addressingcomputeranxiety, lhis stud)' makesa contribution to

the growing literature in this area. This study provides insight

into key constructS and relalionships, and adds to the

understandingofthe role 'heyplayin 'heacceptance and uscof

informationtechnology.

This paper is organized as follows. First, background is

given on the twO theoretical perspectives. Social Cognitive

Theory and theTheory ofInlerpersonal Behavior, tha' underlie

the research. In addition, lhe literarure on computer anxiety is

briefly reviewed. Then, the study's conceptual model and

research hypothesesare presented. Nexl, derailsare providedon

the melhod and the analysis tha' support the study's empirical

investigations and its resullS. Finally. lhe outcomes and

implications of the study are discussed and conclusions are

dmwn.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

In orderto investigatesomekey factorsthoughtto affect an

individual's use ofinfonnation technology. this study draws on

two major theories from social psychology: Bandura's Social

Cognitive Theory and Triandis's llleory of Interpersonal

Behavior. In addition, the literamTe on computer an.xiety

provides support for the study's conceptual model and

hypotheses. This section pro ides a brief overview of the

relevant theoreticaJ and empirical literature that infonns this

study.

SocialCognitiveTheory

Social CognitiveTheory(SCf) is a "theoretical framework

for analyzing human motivation, thought and action" that

"embraces an interaetionaJ model of causation in which

environmental events, personal factors and behavior aU operate

as interactive determinants ofeach other" (IO. p. xi). A key

concept in SCT is perceived self-efficacy which refers to the

beliefan individual has in hislherabilityto successfuJlyperform

a certain behavior (8). Self-cfficaey is conceptualized by

Bandura as varying across tasks and situations. and has a

number ofdeterminanlS (27). Research thai has measured self

efficacy in regard. to specific tasks has proven to have more

prcdieativepower(12). Research has shown that an individual's

Winter20032004 JournalofComputerInformationSystems 95

self-efficaey has 8 direct influence on hislher choice oftaskand

persistence in achieving the task. Low self-efficacy beliefs, for

example. have been found to be negatively related to subsequent

task performance(8).

In developing an integrative framework for research on

computer selfefficaey, researchers found that Bandura and

others had identified over twenty-Lhree antecedent and

consequentfactorsthaiare theoreticallyrelaledtocomputerself-

efficacy (40). Figure I is a model ofa subset ofthe factors

related to self-efficaey, As the model illustrates, cnactive

mastery should be rdOled 10 self-efficacy since. as SCT posits,

these experiences "arc the most influential source of emeacy

information because they provide the most authentic evidence of

whetheronecan mUSIer whalever it takestn succeed" (8, p. 80).

Situational support should also be related 10 self-efficacy, since,

as SCT posits, "people who are socially persuaded that they

posses the capabilities to master difficult situations and are

provided with provisional aMs for effective action are likely to

mobilize grealer e[fort" (9, p. 198). Emotional arousal is

expected to have a negative effect on sclf-efficacy. resulting in

increased levels nfanxiety (II). Ifincreased anxiety leads to

subsequent increases in emotional arousal then a potentially

debilitating cycle ofanltiety can be CreaIed (40). Finally, high

levcls of anxicty can affect behavior. leading 10 lowered

performance(8).

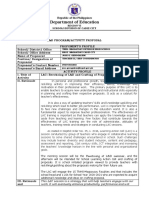

FIGURE I

Self-eflie.cyModel lAd.pledfrom M.r....... Yi andJohnson(40)1

Enactive

Mastery

Situational Self-Eflicacy

Support

..

Emotional

V

Arousal

In the lale 1980sand early 1990s a numberofInformalion

Systems (IS) researchers investigated the relationship between

self-efficacy and computer-related behaviors and attitudes. The

rela'ionship between self-efficacy and software training

behavior was explored (28, 59) as well as the rdalionship

between compuler self-efficacy and the adoption of high

technology products (31). In addition, the concepl of self-

cfficacy plays a key role in the Technology Acceptance Model

(TAM), In his discussion of the theoretical foundations of

model's constructs, Davis indicated that TAM's perceived ease

of use concept is similar to Bandura's definition of self-efficacy

(21). Subsequenl research has investigated whether a person's

perceptions of case of use are anchored to their computer self-

efficacy(33.56). In 1995. SITwasused e.xpliciUy as the basis

for a research model that tested the relationship of computer

self-efficacy and seven other factors including support. anxiety,

and usage (20). Additional research has explnred the

determinants of computer selfefficacy (26) and tbe relationship

between general and specific computer self-efficacy (I). Two

lines of ongoing research may be seen in the IS arena now: I)

research building upon the TAM literature that views computer

selfeflicacy as an determinant of TAM's perceived ease of use

and 2) research based upon SCI'thai posits a cenlra1

role for computer seLf-efficacy as 8 direct dctenninant of

behavior.

Theory of Interpersonal Behavior

Triandis developed a Theory of Interpersonal Behavior

(TIB) !hat posits !hat habits, intentions and facilitating

conditions predict the probability that an act will be performed

(55). Also, in the 11B, social factors, and perceived

consequences of performing the behavior are postulated to

determine intention. TIS is a model of behavioral intention that

Behavior

AnXiety

\ l

provides a theorelical alternative to Ajzen's Theory of Planned

Behavior (TPB) (3). A model thai shows the key factors in the

11Bisprovided in Figure2[adaptedfrom (55)].

IS researchershaveused all orpart ofthcTIBasa basis for

studyingindividual ITacceptanceandusagebehavior(4. 13. 16.

17, 44, 51, 52). In particular, two factors have been utilized

extensively in IS reseaIch: I) habil (often operationalized as

prior computerexperience) and 2) facilita,ing conditions (often

operationalized as various fOnTIS of organizationaVcompul.Cr

support). According10 Triandis, habit strength is "measured by

the number oftimes the act has already been performed by the

person" (54. p. 9) and. thus, as performance of a behavior

increa.ses, its effect on later behavior is expected to increase.

And. although past behavior plays no theoretical role in TPB,

Ajzen found. after 8 review, that "researchers may want to

include a measure of prior behavior in our modelS 10 improve

predictability oflaLcr aclion" (2, p. 120). Similarly. Triandis's

conception of facilitating conditions has influenced IS research.

Facilitating conditions includes access to time. people, money.

or other resources needed to perfonn a behavior. and is imilar

to the perceived behavioml control construel in 11lP (3). Thus,

researchers have investigated the role that habit/computer

experience and facilitating conditions/organizational suppon

play in IT usage both within models based upon 11B and when

usingmodclsbasedonotherapproachessuch asTPB.

Computer Anxiety Literature

Bandura states that otself-efficacy theory suggcslS an

alternativeway oflookingaI human anxiel)l" (10. p. 439). Self-

efficacy theory. as described above, postulates relationships

between emotional arousal. self-efficacy. anxiet)', and behavior.

Many other factors have been aJso explored in relation to

anxiety within the larger theoretical BIld empiricallitcralun:.

Winter 2003-2004 Journal ofComputerInformation ystems 96

FIGURE2

TriandisModel(Adapted from Triandis)

Affect Habit

~

Social Factor.; ~

Intention Beha\1or

.. ..

Perceived Facilitating

V V

Consequences Conditions

Wilhin lile IS research area. anumber ofresearchers have

explored anxiety,oreven fear, thatsome people may experience

when they confront the possibility of using a compuu:r.

Computer anxiety is viewed as anegative emotional reaction or

e!Tect (53) and has been studied as part ofa larger research

stream often termed technophobia orcomputerphobia (46, 47).

Computer anxiety been shown to have8 significant relationship

to key IT constructs su has attitudes toward o p u t ~ usage

intention, usage behavior, and performance(14,18,23.30,57).

IT research has also explored computer anxiety's role as a

dctenninant of perceived case of usc, a key variable in the

Technoiogy Acceptance Model [56]. While computeranxicty is

recognized as an importa1l1 factoT, much remains to be

understood about its role from a lhcorclicaJ perspective. For

example. in his review Marakas concludes: "somewhat

counterintuitive. however, is the apparent lack of global

recognition by theCSE lcomputerself-efficacy) literatureofthe

imponance of thc anxiety relationship and by the

computerphobia literature of the potential value of C E

manipulation and enhancement in reducing anxiety," and he

argues that the complementary relationship between the

computerphobia and computer self-efficacy research calls for

furtherresearcb (40, p. 148). A recentaniclethat examined the

individual I.r8..ilS that are antecedent to computer anxiety ond

computer self-efficacy has begun to address this research gap

(SO).

CO CEPTUALMODELAND RESEARCH

HYPOTHESES

This study's conceptual model and research hypotheses

build upon the SCT. TIB and the computer anxiety Iiterarure.

Based upon the SCT literaruro, the autho..expect I)computer

experienceand organizational support to be positivelyrelated to

computer scLf-.cfficacy, 2) computer self-efficacy to be

negatively related to computer anxiety and positively related to

computcr usage, and 3) computer anxiety to be negatively

related to usage. Based upon the TIB literature, the authors

expect computer experience and organizational support to both

be directly and positively related to computer usage, finally,

based upon the computer anxiety literature. the authors expect

negative relationships between computer anxiety and two

determinants: experience and suppon. The study's conceprual

model is depicted in Figure3. (Note: each ofthe hypothesesare

designated by a label that is referenced later in the iext and

annotated with a (+) to indicate a positive hypothesi.zed

relationship and a(-) to indicate anegativeone.)The remainder

ofthis section provides an overview ofthe IS literature related

to each construct in the model. and lays out the studys

bypotheses.

ComputerSelf-Efficacy

SCT expects that an individual's self-efficacy has a direct

innuence on hisfller choice of task and their persistence in

achieving the task. In the computer acceptance literature. a

numberofstudieshave found that perceivedhigh computerself-

efficacy is related to the use ofa variety oftcchnologically

advanccdproducts(IS,20, 31).Thus, the following isproposed:

!:!!: Computer self-efficacy will be positively related to

computerusage.

Researchers have also bypothesized thaI computer self-

efficacy and computer anxiety arc inversely related. and studies

have found that individuals with lower levels ofanxiety will

have higher levels ofcomputer self-efficacy (36. 37, SO. 58).

Thus.thefollowing is proposed:

H2: Computer sclf-efficacy will be negatively related to

computeranxiety.

ComputerAO.J.iety

Anxiety isan unpleasantemotional reaction experienced by

individuals in threatening situations and the use ofacomputer

appean: to provide a fertile environment for such reactions (19,

41). Since anxiety will often cause people to avoid situations

that trigger these feelings, researche.. t)'pically expect an

inverse relationship between computer anxielY and computer

use. Many studies have found SlJppon for the expected

relationships (20, 33, 34, 37, 41, 58). Thus, the following is

proposed:

IlJ.: Computer anxiety will be negatively related to

computerusage.

Computer Experieou

10 SCf.coactivemastery is posited to predict sclf-efficacy.

In IS research. prior computer experience has been shown to be

ak.ey individual difference variable that predicts computer self

efficac), in a variety of IT applications (I. 20, 33, 40).

Researchers have found, for example. that prior Internet

experience was the strongest predictor ofInternet self-efficacy

(24).Thus,the followingisproposed:

H4: Computcr experience will be positively related to

computerself..-efficacy.

Winter20032004 Journal ofComputerInformation Systems 97

Vician and Davis report mat the most consistent finding of

studies of correlations with computer anxiety is that prior

computer experience has a negative relationship with computer

anxiety (57). In general, people with less experience are more

likely to beanxious when confronted with IT with which they

are unfamiliar(34,46).Thus,the following is proposed:

ill: Computer experience will be negatively related to

computer anxiety.

Furthermore. the TIB proposes that past behavior,

especially in the form of can be a primarydeterminantof

behavior (49). In the IS discipline, a number ofstudies have

found SUppoR for a direct relationship between prior experience

and computer usage (20. 35, 40, 48, 52). One study that

hypothesized no direcl effect of computer experience on

computer usage, based upon the expectation that other variables

would mediate the relationship. found. in fact a significant

relationship between computer experience and computer usage

(33).Thus,the followingisproposed:

H6: Computer experience will be positively related to

computer usage.

fiGURE3

Research Conceptu.al Model

H6(+)

I

Computer

H4 (+)

Computer

Experience

I H5 (-)

--.;

Self-effICacy

H2 (-)

HI (+)

r

Computer

I H7 (+)

Usage

OrganiZlltiona] Computer

Support

H8 (-)

Anxiety

I

H9 (+)

(+) indicatesa positivehypothesi2edrelatIonshipand(-)a negallveone

OrganiulionalSupport

SCT posits thai situational suppon is one of lhe factors that

affecl self-cfficacy. A number of IS researchers have found

support for the proposition that support. of various types.

increases lhe ability of end-users and thus resullS in increased

self-efficacy(20, 33).Thusthefollowing is proposed:

l!l: Organizational support will be positively related to

computer self-efficacy.

Many of the approaches used to reduce computer anxiety

involve makmgsure that situational support is provided so that

an individual perceives there is somewhere 10 lurn for help (18.

53). FOT an individual who is very anxious about intCTBClion

With a particularcomputing technology, further e'posureto the

technolog) alone may not result in reduced anxiety. As an

example, Vician and Davis expect that "developing an

appropriate learning environment for a computing intensive

course will be key to providing a beneficial situation for all

learners"(57,p. 47).Thus,thefollowingisproposed:

H8: Organizational support will be negatively related '0

computer anxiety.

A number of researchers have also recognized the role

organizational support can play in computer usage. and many of

Ihese studies build upon the lIBto conceptualize the role Ihal

facilitating conditions have in infonnation systems usage (55). A

recent study found 8 significant positive relationship between

facililating conditions and computer usage (17). However, !.he

results of otht:r studies have been mixed. One study found the

relationship to be non-signific8m (52) while another found a

negative relationship (S I). Building upon the work of Triandis

andothers,thefollowing isproposed:

H9: Organizational support will be positively related to

computer usage.

THESTUDY

Subjects

The sample consists of 978 business school students

attending a major Southeastern university. Data was collected

over a one-week period. and during this timeframe the survey

was distributed in all business classes. Students were not given

ex!Ttl credilto respond to this "",eyand therefore they had no

incentive to respond to more than one survey. This study's

questions were embedded in a larger survey on the overall

evaluation of me business school. The survey had a

response rate of 4st'1ct. While me use ofstudents in research is

not without controversy (29. ]2. 42), the autho'" believe that

business students are an appropriatc population for this research.

Hughes and Gibson (32) suggest that the use ofstudents needs

to be reviewed for each study for applicability and since the

behavior thaI was measured in this study was the usage ofthe

college computcr lab. business students are appropriate subjects.

Measures and Validation

A questionnaire was dcveloped for this sludy. Most of the

measures were adapted from existing scales that had

demonstrated validity and rcliabi lily in other studies: a)

computer self-cfficacy (42). b) computer anxiety (19) and c)

computer usage (21). The $ole measuring computer

Winler2003-2004 Journ.1 ofComputerInformation Systems 98

organizational support was developed specially for the study's To assess the unidimensionaJity, the covariance matrix ofa five

computer lab environment based upon measures used in a factor model - Computer Experience, Organizational Support.

number of prior studies, and its development has been Compuler Self-Efficacy. Computer Anxiety, and Computer

documentedextensivelyelsewhere(6). Usage- wasevaluated usingL1SREL VIII (38). Thefit statistics

Thequestionnairewasdistributed duringclass.and thus the and internal consistency were examined to assess model fit..

survey length was a key issue in the design. The survey needed discriminantvalidityandreliability.

to be able to be completed within 20 minutes, and therefore Fit statistics and internal consistency estimates for the five

manyofthescaleshad tohereduced in length.Thisreductinn in factor model arereported inTahle I. Due to thescnsitivityofi

lengthofthescalestookplaceduringan extensivepreteststage. to sample size, the root mean square error ofapproximation is

reported as an assessment ofoverall fit. The model is in the

RESULTS acceptable range(.05 to .08) at .052. Thegoodncss-<>f-fit (GFI)

and the adjusted-goodncss-of-fit (AGFI) are .94 and .92,

MeasurementModel Results respectively. Because of inconsistencies due to sample

characteristics. the Tucker-Lewis lndex (TLI) and the

As recommended byAnderson and Gerbing(5), " two-step comparative fit index (CFI) are reponed. For the five factor

approach was adopted. The measurement aspect ofthe model model. the indices are ncar the .90 range (.94 llnd .95.

wasestimated priortotestinglhcstructural asPCCllO preventany respectively)which isdeemed acceptable.

interaction between the two models due to mC8Suremenl error.

TABLE I

MeasurementModel Estimates

FitStatistics

x'

df RMSEA GFI AGYI TLI CFI

655.4 17 .05 .94 .92 .94 .95

2 9

InternllConsistencyMelsures

Como.n AYE

ComputerExperience .70 .46

OrganizationalSupport .82 .48

ComputerSelf-Efficacy .93 .74

ComputerAnxiety .85 .54

Comou,crUsaoe .75 .50

Note. df degreesoffreedom. RMSEA - root mean squareerrorofapprOXimation, GFI - goodness-or-fit mdex,

AGFI- adjusted-goodness-of-fit index;TLI- Tucker-Lewisindex;CFI= comparative-fit index;Compn = compositealpha;

AVE =averagevarianceextracted

Toensurethal the model ismeasuringdistinctconSlIUclS. it StructuralModel Results

was also assessed for discriminant validity. The most stringent

test was performed by checking ifthe square ofthe parameter Toassessthe structural model, threecriteria were used: (I)

estimate between two constructs (cf) is less than the average the fit indices, (2) the significance of the completely

AVE between any two constructs(25). In all cases, discriminant standardized path estimates, and (3) the amount of variance

validitywassupported. explained in each oftheendogenous constructs. Table2 reports

To assess internal consistency. items demonstrating high the correlations among the latent constructs in the StrUcturaJ

within/across factor correlated errors (standardiz.ed residual> aspectofthe model.

2.57) were examined as' candidates for removal. Before deletion The same indices used to evaluate the measurement model

from the study. each indicator was f i ~ examined for its (RMSEA. GFI, AGFI. TLI. and CFI) were estimated for the

conceptual contribution and ifdeemed negligible was removed structural portion and assessed using the same criteria The

from the srudy. In all, seven itemswereremoved from thestudy results inTable3 indicateadequatefit for thefive-factor model.

due to high standardized residuals. As further evidence of TheS1nIcturaJ equation modelingresultsindicatethereisno

internal consistency, the composite reliability estimates arc empirical relationship berween Organizational Support and

examined (see Table I). The reliability estimates ranged from ComputerAnxiety (B8)orherween Organizational Support and

.70 to .93, indicating acceptable reliability for the constructs. Computer Usage (H9). As indicated in Table 3, seven ofthe

Also, all items have significant t-value loadings for lheir nine paths BIe significant (p < .05 or bener). One hypothesis

respective construets (p < .01). Average variance extracted (B3) is statistically significant. but not in the hypothesized

estimates are also reported (Table I). AVE estimates of.45 or direction. Figure 4 shows the hypotheses that were supported

higher are an indication ofvalidity for 8 construct's measure with asolid!.inc. alongwith theirpathestimates.

(43). Eachconstructmeetsthesecrileria.

Winter2003-2004 JournalofComputer InformationSystems 99

AdditionaJly. the strueturdl equations account for 38% of DISCUSSION

me variance in Computer SelfEfficacy. 58% ofthe variance in

ComputerAnx.iety. and 4%oflhevariance in Computer Usage. This study developed a conceptual model based upon the

The faiJure ofthe model to account for greater variation in SCf, TTB and the computer anxiety literature. Six of the

computer usage indicates a need to examine additional factors hypotheses drdwn from this theoreticaJ and empirical literature

related to use. were supported and three hypotheses were not supported. The

resultsarc summarized in Table4.

TABLE2

CorrelationsAmongConstructs

Construct 1 2 3 4 5

(I) ComputerExperience 1.00

(2) Organizational Support -0.09 1.00

(3) ComputerSelf-Efficacy 0.44 0.04 1.00

(4) ComputerAnxiety -0.39 0.02 -0.53 1.00

(5) ComputerUsage 0.01 -0.03 0.06 0.09 1.00

TABLE3

Structural Model Estimates

FitStati!Jtics

x'

df RMSEA GFI AGFI TLI CFI

655.42 179 .052 .94 .92 .94 .95

Path Patb Estimates

ComputerExperience-.Computer YII .60'

ComputerExperience-+ ComputerAnxiety:121

-.4S'

ComplttcrExperience-.ComputerUsage:131

.13'

OrganiUltional Support...ComputerSelf-Efficacy:Y,1

.07'

.00n.s.

Organizational Suppon4'ComputerAnxiety:'(21

-.02n.s.

Organizational Support...ComputerUsage: Y"

-.39'

ComputerSelf-Efficacy...CompulerAnxiety: 6"

.23'

ComputerSelf-Efficacy...CompulerUsage: p"

_26'

ComnuterAnxiety...Comnuter Usa.e:

*p< .OS: n.s. - notSIgnificant

FIGURE4

HypothesizedRelationshipsAmongLatentConstructs

. - - -

1"

6

(.13')

Computer

H4 (.60")

Computer

Experience Self-efficacy

I H5 (,.48,) -

("omputer

112(,39')

,

)II

Usage

I H7 (D7') ,

, -

OrganizationaI Computer

,

;

113 (.26')

Support Anxiety

118 (DO)

,

. 119 (,02)

---

.J\.s expected from SeT,both priorcomputerexperienceand relationship with computer usage (Hl). As expected from 11"8,

organizational supporthad apositive relarionship with computer computer experience had a positive relationship with usage

self-efficacy (H4 and H7). and computer self-efficacy had 8 (H6). As expected from the computer anxiety literature.

negative relationship with computeranxiety (H2) and a positive computer experience had anegative relationship with computer

Winter2003-2004 Journalo(ComputerInformationSystelUs 100

anxiety (H5)_

The hypothesis drawn from SCT that p<>siled that computer

anxiety would have a negative relationship 'Hith usage was nOl

supp<>rted (H3)_ In fact. computer anxiety had a p<>sitive and

significant relationship with usage. The counterintuitive effect of

H) may be due 10 the fact that we measure amount oflime in the

lab. It may take anxious students more time to accomplish the

task than a less anxious student (even when taking into account

experience and computer self-efficacy). AIs<>, our study did nol

assess whether the participants usage behavior was voluntary or

not If participants were required to usc (e.g., to do

work for a class) then individuals would nOl be able to avoid

computer use when anxious. Instead. one might find that their

anxiety results in decreased perfonnanee. and even require more

time spent using the computer. Students might be

overcompensating to Qvt."fCome lheir fear. especially if they must

adopt the technology to succeed in their future career. Further

research would have to explore these possibilities.

TABLE 4

Results of Hypotheses Tests

HVDOth..i. Results

HI: Computer self-efficacy will be positively assoeiated with computer usa'e. Suooorted

H2: Comouter self-efficacv will be nel!ativelv associated with comouter anxietv. SUDoorted

In: Computer anxiety will be assoeiated with computer US8j!;e. Not Supp<>rtcd

1-14: Comoutcr exoerience will be oosilivelv associated with comDuter self-efficacv. SUDOOrtcd

H.5: Computer experience will be nC$t8tively associated with computer anxiety. Supported

116: ComDuter cxoerience will be oositivclv associwcd with COffiouter usa2.C. SUDOOrtcd

H7: Or1!ani11u.ional supoort will be positively assoeiated with compuler self-efficacy. SUPlXlrted

H8: Organizatiooal supp<>rt will be negatively assoeiated with compuler anxiety. NOl Supp<>rted

119: Organizational supp<>rt will be posilively associaled with computer usage. Not Supp<>rted

The hypothesis drawn from TIB that p<>sited that

organizational suppon would have a direct positive relationship

with computer usage was not supported (H9). There are several

p<>ssible explanalions for these results. II may be. as Taylor and

Todd suggest, that "the absence of facilitating resources

represents barriers to usage and may inhjbit the fannalian of

intention and usage: however the presence of faciliLaLing

resources may per so, encourage usage" (48, p. 153).

Another possible reason for the non-support of this hypothesis

might be the items that were used to measure organizational

support. The organizational suppon items were developed

specifically for this study (6), and il could be that items used in

other studies to measure individual's perceptions of facilitating

conditions (33) would have yielded differenl results. This

rationale might als<> explain why the hypothesis from the

computer anxiety literature that posited that organizational

support would have a negative relationship with computer

anxiety was not supported (H8). Funher research would have to

cxplore this p<>ssibility.

The results of this study provide supp<>rt for key hyp<>theses

drawn from Bandura's SeT. Practical implicalions of these

nndings suppon the training literature that encourages efforts to

build computer sclf-efficacy. When individuals have

experiences that build their mastery of IT applicatiOns and arc in

an environment with positive situational support. they tend to

have higber levels of computer self-efficacy. High computer

scII-efficaey. in tum.,. is associated with usage. The findings that

suppon Triandis's 118 also indicate that prior experience may be

a direct detenninant of usage. One possible implication from this

result may be to suggest that computer self--cfficacy is

panicularly important when a new IT application is being

adopted. However, in 8 situation when IT application usage has

become routine or habitual (e.g., checking one's e-mail) then

prior experience may become more important in usage behavior.

The study's other findings suggcst that organizational support

influences usage indirectly, through its relationship with self-

emcacy, but not directly. and not through any influence on

anxiety. Overall, the study's results suggest that organizations

and educators focus their efforts on building computer self

efficacy, and on modifying the detenninants of computer self-

efficacy in order to achieve higher levels of user acceptance of

computer technology.

CONCLUSIONS

Organizations are making signi ficant investments in IT.

However. if individuals do not use infonnation system

applications as anticipated, successful implementation can be

hard to achieve. Theoretjcal and empirical literature in the IS

field continues to investigate the factors that inHueoce the

adoption of IT. and this study contribulCS to that growing body

of literature. This study combines SCT, TIB and compuler

anxiety literature into one conceptual model and then tests the

related bypotheses using a field survey approach. The results

provide partial supp<>rt for hypotheses derived from CT. TIB

and the computer anxiety studies that served as the research

foundation for the study. The theoretically based research model

and the supp<>rt obtained for the majority of the hypotheses

represent a contribution to this area ofstudy.

The resulls lend supp<>rt to the research literalure that

suggests that computer self-efficacy plays a key role in user

acceptance of technolOgy. For example. in training

environments. one could potentially reduce computer anxiety

and increase computer usage by interventions designed to

improve computer self-efficac)'. In the future, longitudinal

research could be designed lO lest causal hypotheses regarding

computer sclf--cfficaey and the other key fBCtOrs involved in

computer usage. By providing insight into the important

relationships between computer sclf-efficacy. anxiety.

experience. supp<>rt and usage. this research can help further

work that explores their role in the acceptance and use of

infonnation technology.

REFERENCES

1. Agarwal. R., V. Sambamurthy, and R.M. Stair. "Research

Report: The Evolving Relationship Between GeneraJ and

Specific Compuler Self-Efficacy An Empirical

Winter 2003-2004 Journal of Computer InformatioD Systems 101

Assessmenl,.. Information Systems Research, II:4, 2000,

pp.418-430.

2. Ajzen, I. "Residual Effects of Past on Later Behavior:

Habituation and Reasoned Action Perspeclives...

PersonalityandSocial Psychology Review,6:2.2002, pp.

107-122_

3. Ajzen. I. "The Theory of Planned Behavior,"

Organizational Be.bavior and Human Decision

Proc.....,50, 1991,pp. 179-211.

4. AlKhaldi, M.A. and R.S. D. Wallace. "The InOuence of

Altitudes on Personal Computer Utilization among

Knowledge Wori<ers: The Case nf Saudi Anlbia.'

Information& Management,36, 1999,pp. 185-204.

5. Anderson, J.C. and D.W. Geroing. " tructural Equation

Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-

Approach," Psycbologiul Bulktin, 103:3. 1988. pp.

411-423.

6. Author{s)(Date). Pleasenote: thedetailsofthispublication

have been withheld 10 ensure the aUlhors are anonymous

duringthereviewprocess.

7. Bailey, J.E. and S.W. Pearson. "DevelopmentofaTool for

Measuring and Analyzing Computer User Satisfaction,"

ManagementSeience,29:5. 1983, pp. 530-545.

8. Bandura. A_ Self-Efficacy: TbeElerciseofControL New

York: W.H. Freeman. 1997.

9. Bandura. A. " elf-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of

BehaYioral Change," Psycbological Review, 84:2, 1977,

pp.191-215.

10. Bandura. A Social Fouodation'ofThought and Action:

A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ:

PrenticeHal!, 1986.

11. Bandura. A. N.E. Adams. and 1. Beyer. "Cognitive

Processes Mediating Behavioral Change," Journal of

Personality and Social P.ychology, 35:3, 1977, pp. 125-

139.

12. Bandura. A. and D. DelVone. "Differential Engagement of

Self-Reactive lnfluences in Cognitive Motivation,"

Organizational Behavior and Human Decision

Proc......38:1,1986.pp. 92-113.

13. Bergeron, F.. S. Raymond. and M.F. Gara. "Determinants

of EIS Use: Testing a Bebavioral Mode!," Oecision

SupportSystems. 14. 1996.pp. 131-146.

14. Brosnan, MJ."IlleImpact ofComputerAnxiety and Self-

Efficacy Upon Performance," Journal of Computer

Assisted Learning, 14, 1998.pp. 223-234.

15. Burldtardt, M.E. and DJ. BI1lSS. "Changing Panems or

PanemsofChange:TheEffectsofaChange in Technology

on Social NetWork Structure and Power,"

SeienceQuarterly,35. 1990,pp. 104-127.

16. Chang, M.K. and W. Cheung. "Determinants of lhe

(ntention 10 Use InlemetIWWW at Work: AConfirmalory

ludy." I.form.tio.& M..agemeat,39.2001.pp. 1-14.

17. Chcung, W.. M.K. Chang, and V.S. Lai. "Prediction of

Internetand World Wide Web Usageal Work: ATestofan

ExtendedTriandisModel."DecisionSupportSy.tem>,30.

2000.pp. 83-100.

18. Coffin. RJ. and P.O. Macintyre. "Motivational InOuences

on Computerrelated Affective Slates,n Computers in

Human Behavior, 15. 1999,pp. 549-569.

19. Cohen, B.A. and G.W. Waugh. "A.se.sing Computer

Anxiety," P.ychological Reports,65. 1989.pp. 735-738.

20. Compeau. D.R. and C.A. Higgins. "Computer Self

Efficacy: DevelopmentoraMeasureand lnit.ial Test." MIS

Quarterly, 19, 1995,pp. 189-21I.

21. Davis, F. "Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease ofUse,

and User Acceptance of Information Technology," MIS

Quarterly, 13:3, 1989.pp.319340.

22. Dickson, G.W., J.A. Senn, and N.L. ChelVany. "Research

in Management Information Syslems: The MinnesoLa

Experiments,"Manageme.tSeience,23:9.pp. 913-923.

23. Durnell. A. and Z. Haag. "Computer Self..,fficacy.

Computer Anxiety, Aniludes Toward the Internet and

Reponed Experience with the Internet, by Gender, in an

East European Sample,"Computers in Human Behavior,

18,2002,pp. 521-535.

24. Eastin, M.S. and R. LaRose. "InternetSelf-Efficacyand the

Psychology ofthe Digilal Divide," Jour.alofComputer

Mediated Communications. 6:1. 2000. Online:

hnp:J/www.ascusc.orWcmdvol6lissuel/eastin.htmL

25. Farnell, C. and D.F. Latcker. "Evaluating Structural

Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and

Measurement Error." Journal of Marketing Ranrcb.

18:1,1981,pp. 39-50.

26. Gardner, W.L. and EJ. Rozell. "Computer Efficacy:

DclcnninanlS, Consequences. and Malleability," JournaJ

ofHigb Tecbnology Mageme.tResearcb. II: I, 2000.

pp. 109-136.

27. Gist. M.E. and R.T. Mitchell. "Self.Efficacy:ATheoretical

AnaJysis ofits and Malleability." Ac.ade.my

ofManagement Review, 17:2, 1992,pp. 183-21L

28. Gist. M.E., C.E. Schwoerer, and B. Rosen. "Effects of

Alternative Training Melbods on Self-efficacy and

Perfonnance in Computer Software Training.," Journal of

Applied P.ychology,74:6, 1989,pp.884-891.

29. Gordon. M.E., L.A. Slade. and N. Sehmitt, "'Ille 'Science

of the Sophomore' Revisited: From Conjecture to

Empiricisl1l.," Atldemy of Manage-ment Rniew, It: II.

1986,pp. 191-207.

30. Harrison. A.W. and R.K. Ranier. "An Examination ofthe

Factor Structures and Concurrent Validities for the

Computer Altilude Scale. the Computet Anxiety Rating

Scaleand theComputerSelf-Efficacy calc," Educational

and P'ychological Mea.urement, 52:3, 1992, pp. 735

746.

31. Hill. T. N.D. Smith. and M.F_ Mann. "Role Efficacy

Expecta1ions in PrediC1ing the Decision 10 Use Advanced

Technologies: The Case of Computers," Journal of

Applied Psycbology. 72:2. 1987.pp.307-313.

32. Hughes.C.T.and M.L. Gibson. "Studentsas urrogatesfor

Managers in a Decision-making Environment: An

Experimental Study," Journal of bnagement

InformatioaSy.tem" 8:2. 1991.pp. 153-166.

33. Igbaria, M. and J_ livara. "The Effects ofSelf-Efficacyon

ComputerUsage,"Omega.23:6.1995,pp.587-605.

34. Igbaria, M. and J. Parasuraman. "A Path Analytic Studyof

Individual Characteristics,ComputerAnxie!) and Anitudes

TowardComputers."Journ.1ofManagement, 15:3. 1989.

pp.373-388.

35. Igbaria. M., 1. Parasununan. and J. Baroudi. "A

Motivational Model ofMicrocomputer Usage,"Journalof

Manageme.t Information Sy,tem" 13:1, 1996, pp. 127-

143.

36. Igbaria, M., F.N. Payri. and S.L. Huff. "Microcomputer

Applications: An Empirical Look al Usage," Information

& Management, 16:4. 1989. pp. 187-196.

37. Johnson, R.D. and G.M. Marakas. "Research Report: The

Role of Behavioral Modeling in Computer Skills

Acquisition - Toward Refinement of the Model,"

InformationSystem.! Research. 11:4.2()(X). pp. 402-417.

38. Joreskog. K. and D. Sarhom. LlSRE!. 8: User',

Reference Guide. Chicago: Scientific Software

International. 1996.

Winter2003--2004 JournalofComputerInformationSystems 102

39. Koons. K.. '. and L.C. Liu."AFactorAnalysisofAttrihutes

Affecting Computing and Infonnation Technology Usage

for Decision Making in Small Business." Intunational

Journal of Computu Applie:ations in Technology,

12:213/4/5,1999.pp81-89.

40. Marak... G.M. M.V. Vi, and R.D. Johnson. "The

Multilcvel and Multifaceted Character ofComputer Self

Effieaey: Toward Clarification of rhe ConslIUct and an

Integrative Framc\'vork for Research.'" Information

ystemsResearch.9:2.1998.pp. 126-163.

41. Marcouldies, G.A. "Measuring Computer Anxiety: The

ComputerAnxietyScale,<>1 Educationaland Psychological

Measurement,49,1989, pp.733-739.

42. Murphy. CA.D. Coover. and S.V. Owen. "Development

and Validation of the Computer SelfEmcacy Scale."

Education and Psychological 49. 1989.

pp.893-899.

43. Nelemeyer. R.G. W.O. Bearden, and S. Sharma. Scaling

Procedure:s: Issues and Applications. Thousand oaks.

CA:Sage.2003.

44. Pare. G. and J. Elam. "Discretionary Use of Personal

Computers by KnowJedge Workers: Testing of 8 Social

Psychological Theoretical Model." Behavior and

I"formationTecbnology, 14:4, 1995,pp. 215-228.

45. Rosen, L.D. and P. Maguire. "Myths and Realities of

ComputerPhobia: A Anxiety R.esearch, 3,

1990.pp. 175-191.

46. Rosen. L.D.. D.C. Sears. and M.M. Wcil. "Treating

Technophobia: A LongilUdinal Evaluation of the

Computerphobia Reduction Progr'dm," Computers in

Human Bebavior,9,1993,pp. 27-50.

47. Sears. D.O. "College Sophomores in the Laboratory:

Influences ofaNarrow Data Base on Social Psychology's

View of Human Nature." Journal of Personality and

SocialP,yehology.51:3.1986,pp. 515-530.

48. Taylor. S. and PA Todd. "Unde=ding Information

Technology Usage: A Test of Competing Models."

InformationSystemsResearch.6:2.1995.pp. 144-176.

49. Taylor, . and PATodd. "Assessing IT Usage: The Role

ofPriorExperience; MISQuarterly, 19:4. 1995. pp. 561-

670.

50. Thatcher. J.B. and P.l. Perrewe. "An Empirical

Examination of Individual TrailS as Antecedents to

Computer Anxiety and Computer Self-Efficacy." MIS

Quarterly.26:4.2002.pp. 381-396.

51. Thompson,R.l.C.A. Higgins.andJ.M. Ho"ell."Influence

ofPersonal Experience on Personal Computer Utilization:

Tcsting a Conceptual Model" Journal of Management

Sy,tems, 11:1. 1994,pp. 167-187.

52. Thompson. R.L.. CAHiggins, andJ.M. Howell. "Personal

Computing: Toward a Conceptual Model of Utilization,"

MISQuarterly,15:1.199l.pp.I25-143.

53. Torkzadeh. G. and I.E. Angulo. "The Conccpl and

Correlates of Computer Anxiety," Behavior and

InformationTechnology, II:2, 1992. pp. 99-108.

54. Triandis. ItC. Inttrpeor5onal Behavior. Monterrey. CA:

Brooks/Cole. 1977.

55. Triandis. H.C. "Values. Altitudes and Interpersonal

Behavior'" Nebraska ymposium on Motivation. In Page.

M.M. (Ed.). !klier,Attitudes and Values. lincoln. NE:

UniversityofNebraska Press. 1980.pp. 195-259.

56. Venkatesh, V. "Determinants of Perceived Ease of Use:

IntegratingControl, Intrinsic Motivation and Emotion into

theTechnology Aceeplance Model." Information System,

Researcb, II:4,2000.pp. 342-365.

57. Vician. C. and L.R. Brown. ""Investigating Computer

Anxietyand Communication ApprehensionasPerfonnance

Antecedents in a Computinglnttnsivc Learning

Journal of Computer Information

Sy,tems,42:2.2002-2003.pp. 51-57.

58. Webster. J.. J.B. Heian. and J.E. Michelman. "Computer

Training'and ComputerAnxiety in the Educational Process:

An ExperimenlaJ Analysis.." Proceedings ofthe: Eleventh

International Conference: on Information ystems,

1990.pp. 171-182.

59. Webster, J. and J.1. Manocchio. "Microcomputer

Playfulness: Development of8 Measure with Workplace

Implications."MISQuarterly, 16:2. 1992,pp. 201-226.

60. Zmud. R.W. "Individual Differences and MIS Success. A

Review of the Empirical Literature." Management

Seienc..25:10.pp.966-979.

SCALEITEMS

Compute:rUsage(itemsstandardized beforerunningCFA)

usageI How ollendo you work in the EBA Micro-Lab?

usage2 Currentlyon averagehowmany hoursaweek doyou use the lab?

usage3 Ofyourcomputerwork for classassignments" whatpercentage isdone in the Micro-Lab?

ComputerSelf-Efliacy

cflieaI Ifeel confident callingupadalafile to viewon themonitorscreen

effica2 I feel confidentusingthecomputerto write:an essayoralener

eflieal I feel confidententeringand savingdarn(numbersorwords) inlO a file

effica4 I feel confidentmovingthecursoraround me monitorscreen

effienS Ifeel confidentmakingselectionsfrom an onscrecn menu

effica6 I fccl confidentescaping/exitingfrom aprogramorsoftware

effica7 Ifeci confidentworkingon apersonaJ computer(microcompul'cr)

effienS Ifeel confidentusingaprintertomakea"hardcopy- ofmy work

Removed

Rt.moved

Remove:d

Winter2003-2004 JournalofComputerInformationSystems 103

ComputtrADJitt}

anxiety I I am confiden, in my ability to use computers IREV)

anxiety2 I tr} to avoid using a compmer whenever possible

anxiety3 Iworry about maJcing mistakeson a computCf

anxiety4 I enjoy working with computers [REV]

anxietyS I feel o\'erwhelmed whenever I am working on a computer

anxiety6 Jfeel anxious whenever Iamusing acomputer

anxiety7 I feci tense whenever working on a computer

anx.iery8 I feel comfortable with computers [REV]

Computer Experieneo (items standardized before running CFA)

"".perill

Indicate your overall computer literacy

z x ~ r t l How many years ago did you first begin using computers?

zexperil3 How knowledgeable are you about computer and software?

Orpniutionll Support

Second-order factor comprised of five dimensions: assisUlncc, access to equipment.

atmosphere. and reliability(print dimension removed)

access I Availability of equipment when needed

access2 Waiting time for 8 computer

access) Townumberof computers

access4 Balance of Pentiums to 386/486 computers

assist I AssiSl8llcc in equipment usc

assist2 Attitudetoward students

assisL3 Suppon in assisting wiLh problems

assist4 Knowledge abou' software

assistS Knowledge about lab opera,ion

assist6 Response time to problems

assist7 Student orientation

alma! Ability laconcentrate on work

atm02 Quiet workingenvironment

atmo3 onfidemialityofwark

hours I Number afhours open

hours2 Evening hours/closing time

hoursJ Open when needed

hours4 Hours of opel'81ion on week-ends

print! Printer quality

print2 3lisfy your printing needs

printJ Printers' output quality

print4 Printer speed

relial FulVcomplele software functionality

relia2 Working order of computers

relial Maintenanceof equipment

rclia4 Reliability ofequipment

reliaS Rei iability ofsoftware

relia6 Dependability ofhardware

Removed

Removed

Removed

boutS of operation, quality of printed output,

Removed

"

Winter 2003-2004 Journal of Computer Information Systems 104

Copyright of Journal of Computer Information Systems is the property of International

Association for Computer Information Systems and its content may not be copied or

emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express

written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual

use.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Exploring The Intention To Use Computers An Empirical Investigation of The Role of Intrinsic Motivation Extrinsic Motivation and Perceived Ease of UseDocument8 pagesExploring The Intention To Use Computers An Empirical Investigation of The Role of Intrinsic Motivation Extrinsic Motivation and Perceived Ease of Usecnad73Pas encore d'évaluation

- (Thompson Et Al., 1991) Personal Computing Toward A Conceptual Model of UtilizationDocument20 pages(Thompson Et Al., 1991) Personal Computing Toward A Conceptual Model of Utilizationrhizom cruz100% (1)

- Looking Inside The "It Black Box": Technological Effects On It UsageDocument15 pagesLooking Inside The "It Black Box": Technological Effects On It UsageCiocoiu Andreea MariaPas encore d'évaluation

- Personal Computing: Toward A Conceptual Model of Utilization 1Document19 pagesPersonal Computing: Toward A Conceptual Model of Utilization 1neethu856Pas encore d'évaluation

- Assessing Individual Performance On Information Technology Adoption: A New ModelDocument16 pagesAssessing Individual Performance On Information Technology Adoption: A New Modeldiah hari suryaningrumPas encore d'évaluation

- Compeau Dan Higgins 1995 - Computer Self-Efficacy - Development of A Measure and Initial TestDocument24 pagesCompeau Dan Higgins 1995 - Computer Self-Efficacy - Development of A Measure and Initial TestmaurishsrbPas encore d'évaluation

- Yang Moon Rowley 2009-50-1Document12 pagesYang Moon Rowley 2009-50-1riki1afrPas encore d'évaluation

- Machine Learning For Public Administration ResearchDocument48 pagesMachine Learning For Public Administration ResearchCarlosEstradaPas encore d'évaluation

- Suggested Citation: Mittelstadt, Brent Daniel, Patrick Allo, Mariarosaria TaddeoDocument68 pagesSuggested Citation: Mittelstadt, Brent Daniel, Patrick Allo, Mariarosaria TaddeoTomasz SzczukaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Ethics of Algorithms Mapping The Deb PDFDocument68 pagesThe Ethics of Algorithms Mapping The Deb PDFDieWeisseLeserinPas encore d'évaluation

- Tmp1a75 TMPDocument9 pagesTmp1a75 TMPFrontiersPas encore d'évaluation

- Social Cognitive Theory and Individual Reactions To Computing Technology: A Longitudinal StudyDocument15 pagesSocial Cognitive Theory and Individual Reactions To Computing Technology: A Longitudinal StudyArysta RiniPas encore d'évaluation

- Kel - 1 Davis, Bagozzi and Warshaw - 1989 - User Acceptance of Computer Technology - A Comparison of Two Theoretical ModelsDocument24 pagesKel - 1 Davis, Bagozzi and Warshaw - 1989 - User Acceptance of Computer Technology - A Comparison of Two Theoretical ModelstantriPas encore d'évaluation

- Technology Acceptance Model PHD ThesisDocument5 pagesTechnology Acceptance Model PHD Thesisfbyhhh5r100% (2)

- Modelling and Simulation of Complex Sociotechnical Systems Envisioning and AnalysingDocument15 pagesModelling and Simulation of Complex Sociotechnical Systems Envisioning and AnalysingMubashir SheheryarPas encore d'évaluation

- System Adoption: Socio-Technical IntegrationDocument13 pagesSystem Adoption: Socio-Technical IntegrationThe IjbmtPas encore d'évaluation

- Power, Politics, and Mis Implementation: Resf - An Cok/LteutiotDocument15 pagesPower, Politics, and Mis Implementation: Resf - An Cok/LteutiotKarthik YadavPas encore d'évaluation

- Venkatesh, Davis - 2000 - A Theoretical Extension of The Technology Acceptance Model Four Longitudinal Field StudiesDocument19 pagesVenkatesh, Davis - 2000 - A Theoretical Extension of The Technology Acceptance Model Four Longitudinal Field StudiesUmmi Azmi100% (1)

- Literature Review On Ethics in Information TechnologyDocument9 pagesLiterature Review On Ethics in Information Technologyk0wyn0tykob3Pas encore d'évaluation

- Predicting User Intentions: Comparing The Technology Acceptance Model With The Theory of Planned BehaviorDocument11 pagesPredicting User Intentions: Comparing The Technology Acceptance Model With The Theory of Planned BehaviorShintya Rahayu Dewi DamayanthiPas encore d'évaluation

- Management Information Systems Research Center, University of MinnesotaDocument55 pagesManagement Information Systems Research Center, University of MinnesotaosoriohjPas encore d'évaluation

- (Venkatesh Et Al., 2003) User Acceptance of Information Technology Toward A Unified View PDFDocument54 pages(Venkatesh Et Al., 2003) User Acceptance of Information Technology Toward A Unified View PDFMohammed Haboubi100% (1)

- Literature Review On Technology Acceptance ModelDocument6 pagesLiterature Review On Technology Acceptance Modelc5swkkcnPas encore d'évaluation

- Hagendorff2021 Article LinkingHumanAndMachineBehaviorDocument31 pagesHagendorff2021 Article LinkingHumanAndMachineBehaviorNuraisyah samsudinPas encore d'évaluation

- Machine Learning in Mental Health: A Systematic Review of The HCI Literature To Support The Development of Effective and Implementable ML SystemsDocument94 pagesMachine Learning in Mental Health: A Systematic Review of The HCI Literature To Support The Development of Effective and Implementable ML Systemsmalissia2092Pas encore d'évaluation

- Direct and Indirect Use of Information Systems in Organizations: An Empirical Investigation of System Usage in A Public HospitalDocument18 pagesDirect and Indirect Use of Information Systems in Organizations: An Empirical Investigation of System Usage in A Public HospitalJecinelle Siplo PatriarcaPas encore d'évaluation

- Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology - WikipediaDocument6 pagesUnified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology - WikipediaMayoPas encore d'évaluation

- Venkatesh Et Al (2003) User Acceptance of Information TechnologyDocument54 pagesVenkatesh Et Al (2003) User Acceptance of Information TechnologyMyPas encore d'évaluation

- Applications of Data-Centric Science To Social Design: Aki-Hiro Sato EditorDocument264 pagesApplications of Data-Centric Science To Social Design: Aki-Hiro Sato Editormarcos pimentelPas encore d'évaluation

- Gender Differences in Technology Usage-A Literature Review: Ananya Goswami, Sraboni DuttaDocument9 pagesGender Differences in Technology Usage-A Literature Review: Ananya Goswami, Sraboni DuttaM jainulPas encore d'évaluation

- SSRN Id4317938Document53 pagesSSRN Id4317938Christine CheongPas encore d'évaluation

- Social Informatics: Principles, Theory, and Practice: in Remembrance of Rob King. Proceedings of The 7thDocument14 pagesSocial Informatics: Principles, Theory, and Practice: in Remembrance of Rob King. Proceedings of The 7thBonggal SiahaanPas encore d'évaluation

- User Interaction With AI-enabled Systems: A Systematic Review of IS ResearchDocument17 pagesUser Interaction With AI-enabled Systems: A Systematic Review of IS ResearchCom DigfulPas encore d'évaluation

- A Grounded Theory Approach To Information Technology AdoptionDocument31 pagesA Grounded Theory Approach To Information Technology AdoptionIyan GustianaPas encore d'évaluation

- Stibe 2015 Towards A Framework For Socially Influencing SystemsDocument13 pagesStibe 2015 Towards A Framework For Socially Influencing SystemsfsdfPas encore d'évaluation

- A Research Framework On Social Networking Sites Usage: Critical Review and Theoretical ExtensionDocument9 pagesA Research Framework On Social Networking Sites Usage: Critical Review and Theoretical ExtensionJaziel LagnasonPas encore d'évaluation

- Employee AnxietyDocument20 pagesEmployee Anxietyasstt.librarian GIFTPas encore d'évaluation

- Thesis Adoption of TechnologyDocument7 pagesThesis Adoption of Technologyfjgqdmne100% (2)

- Thompson 2016Document40 pagesThompson 2016citra utamiPas encore d'évaluation

- 10 Years of Research On Technostress Creators and Inhibitors: Synthesis and CritiqueDocument11 pages10 Years of Research On Technostress Creators and Inhibitors: Synthesis and CritiqueChaimae BOUFAROUJPas encore d'évaluation

- Factores Psicológicos Del TeletrabajoDocument10 pagesFactores Psicológicos Del TeletrabajoKaren ForeroPas encore d'évaluation

- Modeling Behavioral Activities Related To IED PerpetrationDocument8 pagesModeling Behavioral Activities Related To IED Perpetrationapi-61200414Pas encore d'évaluation

- Overview of Established Theories On User Acceptance (UTAUT, TAM, PIIT and ISSM)Document28 pagesOverview of Established Theories On User Acceptance (UTAUT, TAM, PIIT and ISSM)Megat Shariffudin Zulkifli, Dr100% (3)

- SI Theoretical Frames For Social and Ethical Analysis of IT & ICTDocument20 pagesSI Theoretical Frames For Social and Ethical Analysis of IT & ICTTimothyPas encore d'évaluation

- Task Analysis and Human-Computer Interaction: Approaches, Techniques, and Levels of AnalysisDocument9 pagesTask Analysis and Human-Computer Interaction: Approaches, Techniques, and Levels of AnalysisJoseph MuokaPas encore d'évaluation

- Tpack Survey V1point1Document19 pagesTpack Survey V1point1Franklin EinsteinPas encore d'évaluation

- Investigating Tanzania Government Employees' Acceptance and Use of Social Media: An Empirical Validation and Extension of UtautDocument20 pagesInvestigating Tanzania Government Employees' Acceptance and Use of Social Media: An Empirical Validation and Extension of UtautijmitPas encore d'évaluation

- Survey Methodological Aspects Computer Simulation Research TechniqueDocument12 pagesSurvey Methodological Aspects Computer Simulation Research TechniqueNilo EvanzPas encore d'évaluation

- A Meta-Analytic Review of Empirical Research On Online Information Privacy Concerns: Antecedents, Outcomes, and ModeratorsDocument13 pagesA Meta-Analytic Review of Empirical Research On Online Information Privacy Concerns: Antecedents, Outcomes, and ModeratorssaxycbPas encore d'évaluation

- Presented By: Abida EllahiDocument33 pagesPresented By: Abida EllahiAbi_Adrash_7442100% (1)

- Theoretical Background NewwDocument10 pagesTheoretical Background NewwMark James LanoPas encore d'évaluation

- Users and Intermediaries in Information RetrievalDocument12 pagesUsers and Intermediaries in Information RetrievalahmadPas encore d'évaluation

- Main Support Article PDFDocument27 pagesMain Support Article PDFNisrin AliPas encore d'évaluation

- Computers in Human BehaviorDocument10 pagesComputers in Human BehaviorMuhammad Junaid AzamPas encore d'évaluation

- ACC309, Lecture 3 - Management Information Systems TheoriesDocument6 pagesACC309, Lecture 3 - Management Information Systems TheoriesFolarin EmmanuelPas encore d'évaluation

- Print-Out (Penting Rujukan Masterku)Document14 pagesPrint-Out (Penting Rujukan Masterku)AneyBelovedPas encore d'évaluation

- Computer Based Information Systems and Managers' WorkDocument30 pagesComputer Based Information Systems and Managers' WorkHayyan IbrahimPas encore d'évaluation

- Conceptual Foundation of Human Factor MeasurmentDocument257 pagesConceptual Foundation of Human Factor MeasurmentSanty SanPas encore d'évaluation

- The Foundation Role For Theories of Agency in UndeDocument12 pagesThe Foundation Role For Theories of Agency in Undemehmet ali taşPas encore d'évaluation

- Financial Decision, Innovation, Profitability and Company Value: Study On Manufacturing Company Listed in Indonesian Stock ExchangeDocument7 pagesFinancial Decision, Innovation, Profitability and Company Value: Study On Manufacturing Company Listed in Indonesian Stock ExchangeValentino ArisPas encore d'évaluation

- Effect of Personal Innovativeness, Attachment Motivation and Social Norms On The Acceptance of Camera Mobile PhonesDocument22 pagesEffect of Personal Innovativeness, Attachment Motivation and Social Norms On The Acceptance of Camera Mobile PhonesValentino ArisPas encore d'évaluation

- Artikel UTAUT 2Document23 pagesArtikel UTAUT 2Natalia Shara DewantiPas encore d'évaluation

- Smidts A (2001)Document12 pagesSmidts A (2001)Valentino ArisPas encore d'évaluation

- Lit Review JMIRSDocument7 pagesLit Review JMIRSValentino ArisPas encore d'évaluation

- What Is Neo-Liberalism FINALDocument21 pagesWhat Is Neo-Liberalism FINALValentino ArisPas encore d'évaluation

- Glob and NL 02Document29 pagesGlob and NL 02Valentino ArisPas encore d'évaluation

- History of Accounting Thought-1Document13 pagesHistory of Accounting Thought-1Valentino ArisPas encore d'évaluation

- Guided Reading Plans Dra 50Document2 pagesGuided Reading Plans Dra 50api-277767090Pas encore d'évaluation

- Campus Post NewsletterDocument3 pagesCampus Post Newsletterapi-355828098Pas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson Plans Solerebels 44Document2 pagesLesson Plans Solerebels 44Айгерим Арстанбек кызыPas encore d'évaluation

- BUAD 801 SummaryDocument5 pagesBUAD 801 SummaryZainab IbrahimPas encore d'évaluation

- The Effects of Bilingualism On Students and LearningDocument20 pagesThe Effects of Bilingualism On Students and Learningapi-553147978100% (1)

- 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2006.11.003.: Enhancing Student Motivation and Engagement 0Document56 pages10.1016/j.cedpsych.2006.11.003.: Enhancing Student Motivation and Engagement 0palupi hapsariPas encore d'évaluation

- The Memory Healer ProgramDocument100 pagesThe Memory Healer Programdancingelk2189% (18)

- By Carl Greer, PHD, Psyd: Working With Symbols and ImageryDocument2 pagesBy Carl Greer, PHD, Psyd: Working With Symbols and ImageryWilliam ScottPas encore d'évaluation

- Abstract Nouns Board GameDocument2 pagesAbstract Nouns Board GameNina Ortiz BravoPas encore d'évaluation

- Pre DefenseDocument19 pagesPre DefenseTasi Alfrace CabalzaPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter One: 1.0 ForewordDocument58 pagesChapter One: 1.0 ForewordMohamed Al-mahfediPas encore d'évaluation

- False Memory SyndromeDocument6 pagesFalse Memory SyndromeZainab MansoorPas encore d'évaluation

- Existentialism ReportDocument21 pagesExistentialism ReportMerben AlmioPas encore d'évaluation

- 5 A & B English II UnitDocument2 pages5 A & B English II Unitsoumya nPas encore d'évaluation

- Semi-Detailed Lesson Plan in TLE 10 Wellness MassageDocument5 pagesSemi-Detailed Lesson Plan in TLE 10 Wellness MassageChelle Flores Casuga100% (1)

- Competency Iceberg Model 160408160233Document51 pagesCompetency Iceberg Model 160408160233Zibanex SebaloPas encore d'évaluation

- Teaching Additional Languages: by Elliot L. Judd, Lihua Tan and Herbert J. WalbergDocument28 pagesTeaching Additional Languages: by Elliot L. Judd, Lihua Tan and Herbert J. WalbergCarolinesnPas encore d'évaluation

- 3 Theories of Social InstitutionsDocument16 pages3 Theories of Social InstitutionsSze Yinn PikaaPas encore d'évaluation

- Competence of Mathematics Teachers in The Private Secondary Schools in The City of San Fernando, La Union: Basis For A Two-Pronged Training ProgramDocument245 pagesCompetence of Mathematics Teachers in The Private Secondary Schools in The City of San Fernando, La Union: Basis For A Two-Pronged Training ProgramFeljone Ragma67% (3)

- Analytics For Cross Functional Excellence: Ananth Krishnamurthy Professor Decision SciencesDocument3 pagesAnalytics For Cross Functional Excellence: Ananth Krishnamurthy Professor Decision SciencesashuPas encore d'évaluation

- Plural NounsDocument3 pagesPlural Nounsapi-440080904Pas encore d'évaluation

- Zusammenfassung YuleDocument18 pagesZusammenfassung Yulethatguythough100% (1)

- Ice-Breaking Activities For The 1st Day of SchoolDocument2 pagesIce-Breaking Activities For The 1st Day of SchoolEssam SayedPas encore d'évaluation

- EAPP - SummarizingDocument42 pagesEAPP - SummarizingELOISA CANATA100% (1)

- Spatial Working Memory Does Not Interfere With Probabilistic Cued Attention in Visual Search TasksDocument1 pageSpatial Working Memory Does Not Interfere With Probabilistic Cued Attention in Visual Search TasksKrishna P. MiyapuramPas encore d'évaluation

- Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I Have A Dream" Speech As Visual TextDocument15 pagesDr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I Have A Dream" Speech As Visual TextAdarsh AbhinavPas encore d'évaluation

- Magsaysay LAC ProposalDocument7 pagesMagsaysay LAC ProposalJose GerogalemPas encore d'évaluation

- Using Online Games For Teaching English Vocabulary For Jordanian Students Learning English As A Foreign LanguageDocument1 pageUsing Online Games For Teaching English Vocabulary For Jordanian Students Learning English As A Foreign LanguageEkha SafriantiPas encore d'évaluation

- This Study Resource WasDocument1 pageThis Study Resource WasKyralle Nan AndolanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Global Assessment of Relational Functioning GarfDocument2 pagesGlobal Assessment of Relational Functioning GarfelamyPas encore d'évaluation