Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Dental Report FINAL

Transféré par

Statesman JournalCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Dental Report FINAL

Transféré par

Statesman JournalDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Oregon Health & Science University

University of Washington

Prepared by:

Benjamin Sun, MD, MPP

Donald L. Chi, DDS, PhD

1

Emergency Department Visits

for Non-Traumatic Dental Problems

in Oregon State

Part I: Emergency Department Claims Analysis

Part II: Qualitative Interview Analysis

Report to the Oregon Oral Health Funders Collaborative

March 17, 2014

Oregon Health & Science University

University of Washington

Prepared by:

Benjamin Sun, MD, MPP

Donald L. Chi, DDS, PhD

ii

Acknowledgements

The Oral Health Funders Collaborative of Oregon and Southwest Washington determined the need for

this study and several funders pooled resources to provide a grant for this work, including The Ford Family

Foundation, Kaiser Permanente, Northwest Health Foundation, The Oregon Community Foundation,

PacifcSource Foundation for Health Improvement, Ronald McDonald House Charities of Oregon and

Southwest Washington, Ronald McDonald House Charities Global and Samaritan Health Services.

While the authors accept full responsibility for its contents, we also wish to acknowledge the intellectual

as well as the fnancial support of the Collaborative. Many members reviewed an early draft of this report

and provided valuable feedback, as well as support with the logistical challenges of recruiting hospitals and

communities to participate in the project.

Oral Health Funders Collaborative

Vision: Outstanding Oral Health for All

The Oral Health Funders Collaborative of Oregon and Southwest Washington is a partnership of ten regional

philanthropic organizations that are coordinating their eforts to identify, advocate and invest in oral health

solutions. Steering Committee members include Cambia Health Foundation, Dental Foundation of Oregon,

The Ford Family Foundation, Grantmakers of Oregon and Southwest Washington, Kaiser Permanente,

Northwest Health Foundation, The Oregon Community Foundation, Providence Health & Services, Ronald

McDonald House Charities of Oregon and Southwest Washington and Samaritan Health Services. More

information can be found at this website: http://www.oregoncf.org/ocf-initiatives/ohfc

iii

iii

Table of Contents

Section

Part 1: Executive Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . 1

Part 2: Executive Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . 2

PART 1

Background . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

Methods . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

Findings

Table 1. Top Primary Non-Trauma Dental Diagnoses, All Patients . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

Figure 1. Predictors of ED Dental Visits. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

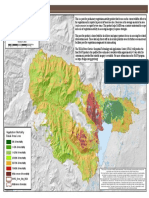

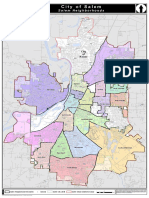

Figure 2. Number of ED Dental Visits by Patient Residential Zip Code (APAC) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

Figure 3. Number of ED Dental Visits per Patient . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

Conclusions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

ED Claims Analysis Study Team . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

Appendix

Study Methods . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

Appendix Table 1 ICD-9 Discharge Codes for Non-Traumatic Dental Problems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

Appendix Table 2 Participating and Non-Participating Hospitals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

Appendix Figure 1 Participating and Non-Participating Hospitals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

Appendix Table 3 Comparison of Participating and Non-Participating Hospitals. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .18

Appendix Table 4 Characteristics of ED Dental and Non-Dental Visits. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

Appendix Table 5 Top 20 Primary Dental Diagnoses, Discharged Patients . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

Appendix Table 6 Top Primary Dental Diagnoses, Admitted Patient . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

Appendix Table 7 Top 20 Secondary Dental Diagnoses, All Patients . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

Appendix Table 8 Top 20 Secondary Dental Diagnoses, Discharged Patients . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24

Appendix Table 9 Top 20 Secondary Dental Diagnoses, Admitted Patients . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26

Appendix Table 10 Prescription Medications Dispensed After ED Dental Visit . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

Appendix Table 11 Procedures Associated with ED Dental Visits . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

Appendix Figure 2 Number of ED Dental Visits in 2010 by Patient Residential Zip Code,

Oregon Health Plan Benefciaries (APAC) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30

Appendix Figure 3 Number of ED Dental Visits in 2010 by Patient Residential Zip Code,

All Payers (Hospital Data) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

Appendix Figure 4 Number of ED Dental Visits in 2010 by Patient Residential Zip Code,

Oregon Health Plan Benefciaries and Uninsured (Hospital Data) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

Page

iv Part 1

PART 2

Section

Background . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

Data . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

Main Findings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37

Preliminary Conceptual Model on NTDC-Related ED use . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43

Policy Recommendations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44

Conclusions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

Study Team . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46

References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47

Page

1 Part 1

Part I: Executive Summary

Part I summarizes the analysis of two complementary data sources for the year 2010: data from 24 Oregon

hospitals representing 745,348 Emergency Department (ED) visits and statewide data on insured patients

visits to Oregon hospitals representing 1,587,649 ED visits. We found:

ED visits for dental conditions are common.

Approximately 2% of Oregon ED visits were for non-traumatic dental problems. This condition is the

twelfth most common ED discharge diagnosis. Among young adults (ages 2039 years), it is the second

most common discharge diagnosis. Extrapolation to all Oregon hospitals suggests 28,000 annual

ED dental visits. Hospital admissions are uncommon (2%) but are associated with potentially

serious medical complications.

ED visits for dental conditions refect lack of access to dental care.

ED visits by uninsured Oregonians were eight times more likely to be for dental problems than were visits

by commercially-insured patients. Compared to commercially-insured Oregonians, Oregon Health Plan

(OHP) enrollees visits were four times more likely to be for dental problems.

People living closer to hospitals are more likely to seek dental care in EDs, emphasizing the importance

of providing access to dental care close to where the need is.

ED visits for dental care are unlikely to cure the patients dental problem.

The majority of patients received opioid pain medications and antibiotics, which may reduce pain and

potentially prevent progression to uncommon but serious complications.

Dental procedures are seldom performed in the ED, suggesting that most patients leave the ED still in

need of defnitive dental care.

One quarter of Oregonians who sought care in an ED for a dental problem returned to the ED for further

dental care.

Failure to provide access to dental care may add cost to the healthcare system.

The mean cost per ED dental visit was $294, greater than the cost for a years coverage in an Oregon

Dental Care Organization (average annual capitation payment $228). Extrapolation to all Oregon

hospitals suggests annual costs as high as $8 million for ED dental visits.

These fndings highlight the need for better community resources for oral health. Medicaid expansion as

part of the Afordable Care Act, combined with integration of medical and dental benefts through Oregons

Coordinated Care Organizations, provide unique opportunities to improve oral health and reduce ED dental

visits of Oregonians. However, when that care is not available, preserving ED access remains essential

to relieve the burden of pain, reduce the risk of infectious complications, and identify uncommon but

medically serious conditions associated with dental problems.

POLICY RECOMMENDATION:

Oregon should mandate ED data reporting, similar to requirements in 31 other states. ED claims

collection from individual health systems is slow, burdensome, and results in incomplete data.

A statewide, mandatory ED dataset will facilitate future health policy analyses.

2 Part 1

Part 2: Executive Summary

Part II summarizes analyses from interviews with 34 stakeholders and 17 patients in 6 Oregon communities.

We had three goals: 1) to identify the factors related to ED use for non-traumatic dental conditions (NTDCs);

2) to poll stakeholders on potential solutions that could be implemented to reduce NTDC-related ED use;

and 3) to distill research fndings into prevention-oriented policy recommendations.

The determinants of NTDC-related ED visits are multilevel and multifactorial

ED visits are related to factors at the health system, community, provider, and patient levels.

The health system is disjointed and the state Medicaid program, at the time of the interviews, had

limited dental coverage for adults.

At the community level, lack of urgent care clinics, insufcient dissemination of information on dental

care resources, and no water fuoridation contributes to NTDC-related ED visits.

At the provider level, there are few dentists who accept Medicaid, dental ofce policies are infexible

(particularly in regards to after hours emergencies), and many dentists refer patients directly to the ED.

Social and economic disadvantage, poor oral health behaviors (e.g., symptom-driven dental care use),

dental fears, and lack of a dental home were cited by patients as reasons for individuals utilizing the ED.

Even with the Afordable Care Act and Coordinated Care Organizations, there will be individuals who

do not qualify for dental coverage, leaving some vulnerable individuals susceptible to NTDC-related ED

visits.

Stakeholders ofered potential solutions to reduce ED use for NTDCs, many of which are un-

likely to systematically solve the problem

Train more dentists.

Open mode dental clinics, including urgent care clinics.

Increase availability of dentist-on-call within ED.

Enhance ED-to-dental-ofce referral system.

Assign Medicaid enrollees with primary dental care providers and case managers

Most solutions provided by stakeholders focused predominantly on improving access to dental care,

which is unlikely to meaningfully reduce NTDC-related ED visits

Reducing and preventing ED use for NTDCs involves a systematic, multilevel approach

Focus on primary prevention in adolescents to reduce subsequent ED visits by Medicaid enrollees ages

20 and 30

Develop a statewide surveillance system focusing on adolescents (Smile Survey) and implement metrics

to track progress within this high-risk population

Use the current Medicaid system and work with school nurses within junior and senior high schools to

identify and refer adolescents with dental disease and treatment needs

Educate community about changes in the Oregon Health Plan (Medicaid) and dental benefts

Distribute free toothpaste and reduce availability of sugar sweetened beverages within schools (pouring

rights)

3 Part 1

PART 1

Background

There are an estimated 2 million annual ED visits for non-traumatic dental problems (dental pain and oral

disease caused by caries, pulpitis, periodontal disease) in the United States

1

and the incidence has increased

over the past decade.

26

Use of EDs for non-traumatic dental problems generates over $110 million in

charges per year in the United States

7

. EDs are ill-equipped to provide defnitive dental care such as dental

restorations or tooth extractions

810

. Management of non-traumatic dental problems in the ED consists

primarily of temporary pain and infection control through prescriptions for analgesics and antibiotics

11

.

Elimination of Medicaid dental coverage in Oregon

12

and Maryland

13

led to increases in ED visits for

non-traumatic dental problems. Patient surveys identifed lack of insurance, lack of money, no existing

relationship with a regular dentist, and limited hours of dental care sites as reasons for seeking dental care in

an ED

14

. Multiple studies

17, 9,1117

have consistently identifed lack of insurance, Medicaid insurance, young

adult age (1844 years), and black race as predictors of visiting an ED for dental pain.

Developing interventions to improve dental access in Oregon communities requires state-specifc data but

little research has been done about dental ED use in our state. This report addresses these knowledge gaps.

A separate report, led by Donald Chi, DDS, PhD of the University of Washington, describes fndings from

qualitative analyses of dental community stakeholder interviews.

Methods

In order to characterize dental ED use throughout the entire State of Oregon as accurately as possible, we

obtained emergency department data from two sources. We requested data from a representative sample

of Oregons 58 hospitals selected based on urban/rural location, critical access designation, geographic

distribution, and annual ED visits. In addition, we obtained data from the Oregon All Payer All Claims (APAC)

database, maintained by the Oregon Health Authoritys Ofce for Oregon Health Policy and Research.

The two data sources complement each other in several ways. Despite its name, the All Payer All Claims

dataset contains data on ~6570% of ED visits. It excludes ED visits by the uninsured, as well as ED visits by

enrollees in Medicare fee-for-service plans, some other federal programs, and one commercial insurer.

Conversely, the data obtained directly from hospitals includes all ED visits to those hospitals; however, only

24 hospitals provided data. The APAC dataset includes all Oregon EDs, allowing a statewide picture for those

payer classes included in the data.

With careful attention to the strengths and limitations of each data source, we are confdent in the results

presented in this report. Where there are concerns about our ability to provide an accurate statewide

picture, we have made those limitations explicit in the Appendix, which provides further detail about the

methods used.

4 Part 1

Findings

ED visits for dental conditions are common.

There were 745,348 ED visits in 2010 to the 24 participating hospitals. Of these, 15,018 visits (2%) were

for non-traumatic dental problems. Dental conditions represent the twelfth most common ED primary

discharge diagnosis and are more frequent than headache, pneumonia, and asthma. Among young adults

(ages 2039 years), dental conditions represented the second most common discharge diagnosis.

We describe specifc dental diagnoses in Table 1. The most common diagnosis (41% of visits) was

unspecifed disorder of the teeth. The lack of precision in diagnosis may refect emergency physicians

inability to defnitively diagnose many dental conditions.

Primary Diagnosis ICD9 Code n %*

Unspecifed disorder of the teeth and supporting structures 525.9 6232 41.5

Periapical abscess without sinus 522.5 3521 23.45

Dental caries, unspecifed 521.00 2958 19.7

Acute apical periodontitis of pulpal origin 522.4 1098 7.31

Other dental caries 521.09 611 4.1

Other dental diagnoses 523.9 563 3.8

*denominator is all ED visits with primary non-trauma ED dental diagnosis (denominator = 15,018)

Table 1: Top Primary Non-Trauma Dental Diagnoses, All Patients

Although only 360 (2%) patients with dental ED visits required hospital admission, these cases illustrate the

risks of deferring dental care. Diagnoses included infectious complications of dental conditions, such as

cellulitis and abscess of face or oral soft tissues, cellulitis and abscess of the neck, pneumonia, and bacterial

endocarditis. Other patients were admitted with uncontrolled diabetes, a condition that can be aggravated

by dental infections.

Despite its limitations, the APAC database yields a similar estimate of the total number of dental ED visits

in the state. Of the 1,587,649 ED visits in the APAC database, there were 25,683 ED dental visits. Adding the

uninsured and the other groups not included in APAC supports the estimate of 28,000 dental ED visits per

year obtained from the participating hospitals.

5 Part 1

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

1.2

1.4

1.6

*Asian *Other *Hispanic white (reference) Missing Black Native American

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

Other Medicare Commercial Medicaid -

Other States

Medicaid

(formerly OHP)

Uninsured

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

Male (reference) Female

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0-14

(reference)

1

15-19 20-39 40-64 65+

ED visits for dental conditions refect lack of access to dental care.

ED visits by uninsured Oregonians were eight times more likely to be for dental problems than were visits

by commercially-insured patients (Figure 1). Compared to commercially-insured Oregonians, Oregon Health

Plan (OHP) enrollees visits were four times more likely.

Other predictors of an ED dental visit included young adult age (2039 years) and male gender. Asians,

Hispanics, and other race patients were less likely to have an ED dental visit compared to whites.

Gender

Figure 1: Predictors of ED Dental Visits

Insurance

The Y-axis represents the unadjusted relative risk that an individuals ED visit is for

a dental condition, given that they had an ED visit.

Age

Race

Other Medicare Commercial Medicaid Medicaid Uninsured

(reference) (other states) (formerly OHP)

014 1519 2039 4064 65+

(reference)

Male Female

(reference)

Asian Black Hispanic Native Other White Missing

American (reference)

6 Part 1

Figure 2. Number of ED Dental Visits by Patient Residential Zip Code (APAC)

Geographic analyses (Figure 2) show that most users of EDs for dental conditions live near hospitals. This

fnding suggests an opportunity for a solution: Locating dental safety net clinics in communities with high

dental ED use could reduce the unmet dental care needs in these high-use communities.

Non-Traumatic ED Dental Visits

0/Insufficient Data

1 - 3

4 - 13

14 - 37

38 - 300

Hospital Locations

7 Part 1

ED visits for dental care are unlikely to cure the patients dental problem.

The majority of patients received prescriptions for pain medications (56% received opioids and 9%

nonsteroidal anti-infammatory drugs). A signifcant proportion of patients received antibiotics (36%

received penicillins, 16% clindamycin, 2% macrolides, and 2% cephalosporins).

However, dental procedures were seldom performed: 7% of encounters were associated with a facial nerve

block (which provides only temporary relief of pain), while only 2% resulted in drainage of a dental abscess.

Fewer than 0.04% had a tooth extraction. These fndings confrm the perception that EDs lack the proper

equipment (e.g. panoramic dental x-ray machines) and personnel to deliver defnitive dental care.

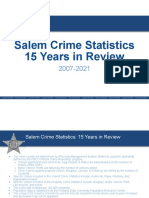

Over 25% of patients with an ED dental visit had more than one annual ED encounter for non-traumatic

dental problems, suggesting that the problem was not defnitively treated on the frst visit (Figure 3). The

estimate of repeat ED dental visitors is likely an undercount due to the exclusion of uninsured and Medicare

Fee-For-Service patients in APAC. These excluded groups are at higher risk of experiencing an ED dental visit.

Failure to provide access to dental care may add cost to the healthcare system.

In the APAC population, 25,683 ED dental visits accounted for $7.2 million in costs, at a mean cost of $293

per visit. Extrapolation to all Oregon hospitals suggests annual costs as high as $8 million associated with

ED dental visits.

Comparing the cost of ED dental care to the cost of providing an improved dental safety net is beyond the

scope of this study. However, it is striking to note that the average annual capitation payment for an Oregon

Dental Care Organization is $228, less than the $293 average cost for a single dental ED visit

15

.

Figure 3: Number of ED Dental Visits Per Patient

0

2000

4000

6000

8000

10000

12000

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80

Frequency

N

u

m

b

e

r

o

f

p

a

t

i

e

n

t

s

Number of ED Visits

0

2 0 0 0

4 0 0 0

6 0 0 0

8 0 0 0

1 0 0 0 0

1 2 0 0 0

0 1 0 2 0 3 0 4 0 5 0 6 0 7 0 8 0

F r e q u e n c y

8 Part 1

Conclusions

In summary, ED visits for non-traumatic dental problems are common, especially in patients whose

insurance status reduces their access to dental care.

Most ED visits fail to cure the dental condition, and the cost of these visits is substantial. Making available

timely and accessible care by a dental practitioner is likely to reduce dental ED use while improving the oral

health of vulnerable Oregonians.

However, when that care is not available, preserving access to emergency departments for dental conditions

remains essential to relieve the burden of pain, reduce the risk of infectious complications, and identify

uncommon but medically serious conditions associated with dental problems.

POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

Part I of this study focused on describing the extent and impact of ED dental visits, and Part II will describe

potential solutions. However, our research team noted that collecting ED data from health systems was slow,

laborious (requiring multiple institutional research and business agreement documents), and resulted in

incomplete statewide coverage. Thirty one other states have mandatory ED data reporting requirements

20

,

and similar requirements in Oregon would facilitate health policy analyses.

Oregon should mandate ED data reporting by hospitals. The state already mandates reporting of

inpatient data, and this existing reporting infrastructure could be used to collect ED data.

9 Part 1

Part I: ED Claims Analysis Study Team

Principal Investigator: Benjamin Sun, MD, MPP

Associate Professor, Department of Emergency Medicine, Center for Policy and Research in Emergency

Medicine, Oregon Health and Science University

Co-Investigators:

Robert A. Lowe, MD, MPH

Professor, Department of Medical Informatics and Clinical Epidemiology, and Department of Emergency

Medicine; Senior Scholar, Center for Policy and Research in Emergency Medicine, Oregon Health and

Science University

Eli Schwarz, DDS, MPH, PhD

Professor and Chair, Department of Community Dentistry, Oregon Health and Science University

Project Staf:

Annick Yagapen, CCRP; Susan Malveau, MPH; Zunqiu Chen, MS and Ben Chan, PhD (OHSU)

Site Recruiters:

Sankirtana Danner, MA (OHSU Oregon Rural Practice-based Research Network); Paul McGinnis, MPA

(Eastern Oregon CCO); Erin Owen, MPH (Slocum Research & Education Foundation)

Mapping Consultants:

Molly Vogt, MS (Metro); Clinton Chiavarini, MS (Metro) and Emerson Ong (Oregon Ofce of Rural Health)

10 Part 1

Appendix: Study Methods

In this section, we provide detail about the methods used for this project, including the defnition of an ED

dental visit, data sources, hospitals contributing to the ED dataset, methods used to identify dental ED visits,

methods used to determine medications and procedures associated with ED dental visits, approach to

estimating costs for ED dental care, and methods for geographic analyses of dental ED use.

Defning an ED Dental Visit

To defne an ED dental visit, we used prior research

2, 5, 11, 13, 1619

as well as the content expertise of dental

health service researchers on our study team. We identifed a set of ICD-9 discharge codes consistent with

non-traumatic dental problems. (Appendix Table 1) We focus on non-traumatic dental problems because

emergency physicians can rarely provide defnitive care for these conditions; these visits refect an unmet

need for community dental care. An ED dental visit was defned by presence of these codes as the primary

diagnosis on an ED claim.

We excluded traumatic dental problems as these may represent acute injuries, including isolated dental

injuries as well as those associated with other injuries (e.g. facial lacerations, facial bone fractures,

intracranial bleed). There may be limited alternatives other than EDs for the acute evaluation of such injuries.

Data sources

We collected 2010 data from two data sources: claims data obtained directly from hospital systems, and

the Oregon All Payer All Claims (APAC) database. We describe each dataset and how they complement each

other.

Hospital Claims Data

We requested ED claims data directly from a purposive sample of Oregon hospitals. We initially identifed

45 hospitals that were representative of all 58 Oregon hospitals, by urban/rural location, critical access

designation, geographic distribution, and annual ED visits. We contacted the CEO or CMO of all targeted

hospitals, and we signed Data Use and Business Use Agreements with all participating hospitals.

The strength of these data is the inclusion of all payer groups for the participating hospitals. We used the

hospital claims data to estimate the frequency of ED dental visits and to identify predictors of ED dental

visits.

A limitation of hospital claims data is the lack of uniform reporting on procedures, antibiotics, and costs.

In addition, these data may have limited geographic generalizability.

Of the 45 hospitals that were invited to participate in this study, 24 provided 2010 data on all ED visits.

Appendix Table 2 is a list of all Oregon hospitals sorted by participants and non-participants. Appendix

Figure 1 illustrates the locations of participants and non-participants. Appendix Table 3 uses data from the

American Hospital Association Survey and the Ofce for Oregon Health Policy and Research to illustrate the

diferences between participating and non-participating hospitals. Rural, critical access, and low volume

hospitals are under presented in our sample set. Thus, the analyses of hospital claims data may have limited

generalizability to excluded hospitals.

In Appendix Table 4, we describe the characteristics of all ED visits for both dental and non-dental problems.

The primary discharge diagnoses associated with ED dental visits are presented in the main report (Table 1).

We provide descriptive tables of primary diagnoses, stratifed by both discharged and admitted patients in

Appendix Tables 5 and 6.

11 Part 1

In addition to this descriptive reporting, we calculated the unadjusted relative risk ratios for diferent values

of age, gender, race, and payer that an ED visit would be for a dental condition. The results of these relative

risk analyses are illustrated in the main report (Figure 1).

Five hospitals within the Providence Health System (Seaside; St. Vincent; Hood River; Newberg; and Medford)

provided aggregated, rather than encounter level, data on non-dental ED visits. These hospitals, accounting

for 20% of the data, were included in descriptive reports (Appendix Table 3) but excluded from the relative

risk analysis.

Although our analyses focused on patients with a primary diagnosis of a non-traumatic dental problem,

an additional 3,551 (0.4% of all ED visits) ED visits had a secondary diagnosis of a non-traumatic dental

problem (Appendix Tables 79). The three most common associated primary diagnoses were other acute

pain, antepartum condition, and traumatic wound of tooth. This population likely includes a mixture of

patients with a primary dental problem as well as those with a unrelated primary reason for an ED visit. Our

approach of using only primary diagnoses codes to defne an ED dental visit reduces contamination by ED

visits primarily for a non-dental problem; however, it may result in an undercount of all ED dental visits. We

identifed an additional 301 hospitalizations with a secondary diagnosis of a non-traumatic dental problem;

these cases are described in the Results section and in Appendix Table 9.

The Oregon All Payer All Claims Database

The All Payer All Claims (APAC) database contains statewide information on ED visits by patients covered by

the Oregon Health Plan, commercial payers, and Medicare managed care. Our research group is among the

frst in Oregon to obtain and analyze the APAC data.

The strengths and weaknesses of APAC are the inverse of the hospital claims data. Strengths include unique

information on procedures, antibiotics, and costs. APAC can also be used to generate statewide profles of

ED dental visits.

The major limitation of APAC is the exclusion of certain payer groups. Most notably, APAC omits visits by the

uninsured that represent about 18% of Oregon ED visits, and the uninsured disproportionately use EDs for

non-traumatic dental problems. APAC also currently omits patients who are covered by Medicare Fee-For-

Service (FFS) and federal insurance (TRICARE, FEHB). Finally, one major commercial payer (Kaiser) has not yet

submitted data to APAC. Therefore, we do not rely on APAC to describe patient level characteristics such as

payer or to identify predictors of ED dental visits.

Identifying medications and procedures

With the APAC database, we identifed the top 20 non-refll prescription medication classes that were

dispensed within 3 days after an ED dental visit (Appendix Table 10). An important limitation to note is the

inability to verify that the prescriber and the ED provider were the same; it is possible that some medications

were prescribed by non ED-providers and were not related to the ED dental visit. However, the frequent

prescribing of pain medications and antibiotics noted in the APAC data is consistent with our clinical

experience.

We used billing codes (Current Procedural Terminology [CPT]) to identify procedures performed in the ED

(Appendix Table 11). This analysis excludes CPT Evaluation and Management codes that are based on the

complexity of medical decision making.

12 Part 1

Estimating costs for ED dental care

It is important to note that cost is a distinct concept from charge and payment. Charge is the billed amount,

varies greatly by hospital, and often has little relationship to cost. We did not have access to charge data.

APAC does include data on payments by insurers and patients. According to Oregon State APAC analysts,

payment data have not been verifed, and submitted Oregon Health Plan payment data are likely to be

fawed. Therefore, we do not present payment data in this report.

To estimate true costs refecting resources required to provide ED dental services, we applied the 2010

Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) national payment tables to all CPT codes associated with

an ED dental visit. CMS payment tables are commonly used to approximate actual cost of medical services

21

.

Geographic analyses

We used both hospital and APAC data to illustrate where Oregonians who use EDs for dental conditions live.

We provide maps that illustrate frequency counts by zip codes.

There are two important methodologic limitations of our mapping approach for hospital claims data. First,

our hospital claims data did not include all hospitals in Oregon. A resident in a given zip code might have

gone to a nearby ED included in our data or to another nearby ED not included in our data. To address this

limitation, we used data from the Oregon Patient Origin Dataset to identify, for each ZIP code, the market

share for all Oregon hospitals in 2010. We then weighted the counts in each zip code to account for missing

data. For example, if our dataset had 500 ED dental visits originating in zip code 97229 but we only had

hospital data that accounted for 50% of hospital visits originating from that zip code, then we would infate

by a factor of 2 (for an estimated 1000 ED dental visits) to account for missing data. This approach makes the

assumption that ED visit rates are similar in missing data as they are in observed data.

Second, we had very few or no observed data from some zip codes. This may refect a combination of

missing hospital data and low population density in rural areas. If a zip code count was zero or was missing

more than 75% of hospital market share data, then we considered data to be unreliable for that zip code.

This approach reduces the ability to make conclusions about low-population areas and areas which are

poorly represented by our data.

APAC data include all Oregon EDs but exclude patient populations that are not represented in APAC (e.g.

uninsured, Medicare Fee-For-Service). Despite statewide coverage of APAC, there were no reported ED

dental visits for a subset of low-density zip codes.

Despite diferences in data completeness and methodology, the hospital and APAC data show similar

geographic patterns, and patterns were similar for uninsured and OHP-sponsored patients compared to all

ED patients. The robustness of our geographic fndings in two diferent datasets adds to our confdence in

these results.

Because of the similarity between diferent maps of dental ED visits, we present only the APAC map in the

body of the report (Figure 2); the other maps are presented here (Appendix Figures 2-4).

13 Part 1

ICD-9 Discharge Codes For Non-Traumatic Dental Problems

Non-Traumatic Dental Problems

520.0520.9: Disorders of tooth development and eruption

521.0521.9: Diseases of the hard tissue of teeth

522.0522.9: Diseases of pulp and periapical tissues

523.0523.9: Gingival and periodontal diseases

525.0525.9,

excluding 525.11:

Other diseases and conditions of the teeth and supporting structures

Appendix Table 1: ICD-9 Discharge Codes for Non-Traumatic Dental Problems

14 Part 1

Participating Hospital Name

Health

System

Region

Rural/

Urban

Critical

Access

ED

Annual

Visits

Yes Blue Mountain Hospital

self/none

known

NE Oregon rural Yes 2989

Yes

Cottage Grove Community

Hospital

PeaceHealth SW Oregon rural Yes 11378

Yes Grande Ronde Hospital

self/none

known

NE Oregon rural Yes 12306

Yes

Kaiser Sunnyside Medical

Center

Kaiser Portland urban No 52508

Yes Lake District Hospital

Lake Health

District

Cascades

East

rural Yes 3502

Yes

Legacy Emanuel Hospital &

Health Center

Legacy Portland urban No 46485

Yes

Legacy Good Samaritan

Hospital

Legacy Portland urban No 28440

Yes

Legacy Meridian Park

Hospital

Legacy Portland urban No 30735

Yes

Legacy Mount Hood

Medical Center

Legacy Portland urban No 40138

Yes

McKenzie-Willamette

Medical Center

Community

Health Systems

SW Oregon urban No 26803

Yes Mercy Medical Center Catholic Health SW Oregon rural No 40577

Yes OHSU Hospital OHSU Portland No 40268

Yes Peace Harbor Hospital PeaceHealth SW Oregon rural Yes 7667

Yes

Providence Hood River

Memorial Hospital

Providence NE Oregon rural Yes 9341

Yes

Providence Medford

Medical Center

Providence SW Oregon urban No 28892

Yes

Providence Milwaukie

Hospital

Providence Portland urban No 35955

Yes

Providence Newberg

Hospital

Providence Pacifc rural No 18308

Yes

Providence Portland

Medical Center

Providence Portland urban No 67874

Yes

Providence Seaside

Hospital

Providence Pacifc rural Yes 9661

Yes

Providence St. Vincent

Medical Center

Providence Portland urban No 86099

Yes

Sacred Heart Medical

Center RB

PeaceHealth SW Oregon urban No 40666

Appendix Table 2: Participating and Non-Participating Hospitals

15 Part 1

Participat-

ing

Hospital Name

Health

System

Region

Rural/

Urban

Critical

Access

ED

Annual

Visits

Yes

Sacred Heart Medical

Center UD

PeaceHealth SW Oregon No 33528

Yes Sky Lakes Medical Center

self/none

known

Cascades

East

rural No 18974

Yes Tuality Healthcare Tuality Portland No 42416

No Adventist Medical Center

Adventist

Health

Portland No 44155

No

Ashland Community

Hospital

California-

based

SW Oregon rural No 9957

No Bay Area Hospital

self/none

known

SW Oregon No 25075

No

Columbia Memorial

Hospital

self/none

known

Pacifc rural Yes 13939

No Coquille Valley Hospital

self/none

known

SW Oregon rural Yes 4218

No Curry General Hospital

Curry Health

Network

SW Oregon rural Yes 3877

No

Good Samaritan Reg

Medical Center

Legacy Pacifc No 21062

No

Good Shepherd Healthcare

System

self/none

known

NE Oregon rural Yes 16183

No Harney District Hospital

self/none

known

Cascades

East

rural Yes 2430

No

Lower Umpqua Hospital

District

Lower Umpqua

Hospital

District

SW Oregon rural Yes 3436

No

Mid-Columbia Medical

Center

self/none

known

NE Oregon rural No 17223

No

Mountain View Hospital

District

Cascade

Healthcare

Community

Cascades

East

rural Yes 10375

No

Pioneer Memorial Hospital -

Heppner

Cascade

Healthcare

Community

Cascades

East

rural Yes 804

No

Pioneer Memorial Hospital -

Prineville

Cascade

Healthcare

Community

Cascades

East

rural Yes 9203

No

Providence Willamette Falls

Medical Center

WFH Portland urban No 28165

Appendix Table 2: (continued)

16 Part 1

Participat-

ing

Hospital Name

Health

System

Region

Rural/

Urban

Critical

Access

ED

Annual

Visits

No

Rogue Valley Medical

Center

Asante Pacifc urban No 37552

No Salem Hospital Salem Health Pacifc urban No 87822

No

Samaritan Albany General

Hospital

Samaritan

Health

Pacifc urban No 24421

No

Samaritan Lebanon

Community Hospital

Samaritan

Health

Pacifc rural Yes 13170

No

Samaritan North Lincoln

Hospital

Samaritan

Health

Pacifc rural Yes 10017

No

Samaritan Pacifc

Community Hospital

Samaritan

Health

Pacifc rural Yes 12539

No Santiam Memorial Hospital

self/none

known

Pacifc rural No 11408

No Silverton Hospital

Silverton

Health

Pacifc rural No 24341

No Southern Coos Hospital

self/none

known

SW Oregon rural Yes 4156

No

St. Alphonsus Medical

Center - Baker City

Catholic Health NE Oregon rural Yes 7198

No

St. Alphonsus Medical

Center - Ontario

Catholic Health NE Oregon rural No 18639

No St. Anthony Hospital Catholic Health NE Oregon rural Yes 12903

No

St. Charles Medical Center -

Redmond

St. Charles

Cascades

East

rural No 17492

No

St. Charles Medical Center

Bend

St. Charles

Cascades

East

urban No 36606

No

Three Rivers Community

Hospital

Asante SW Oregon rural No 35529

No

Tillamook County General

Hospital

Adventist

Health

Pacifc rural Yes 9722

No

VA Roseburg Healthcare

System

Federal SW Oregon urban No 13586

No

Veterans Afairs Medical

Center

Federal Portland urban No 14320

No Wallowa Memorial Hospital

self/none

known

NE Oregon rural Yes 2677

No West Valley Hospital Salem Health Pacifc rural Yes 12651

No

Willamette Valley Medical

Center

self/none

known

Pacifc rural No 24191

Appendix Table 2: (continued)

17 Part 1

Hospital Study Participation

Participated

Did Not Participate

Appendix Figure 1: Participating and Non-Participating Hospitals

18 Part 1

Variable Non-Sample Study Sample p-value*

Hospitals (n) 36 (60%) 24 (40%) n/a

AHEC Region (n, %)

Cascades East 6 (16.67%) 2 (8.33%)

0.01

NE Oregon 6 (16.67%) 3 (12.5%)

Pacifc 13 (36.11%) 2 (8.33%)

Portland 3 (8.33%) 10 (41.67%)

SW Oregon 8 (22.22%) 7 (29.17%)

Rural (n, %) 26 (72.22%) 10 (41.67%) 0.02

Critical Access Hospital: Yes (n, %) 18 (50%) 7 (29.17%) 0.1

ED Annual Visits (mean, SD) 17806.72 (16121.54) 30646.25 (20524.98) 0.01

Inpatient Beds (mean, SD) 86.08 (96.31) 171.79 (166.9) 0.02

*p<0.05 indicates a statistically signifcant diference between participants and non-participants

Appendix Table 3: Comparison of Participating and Non-Participating Hospitals

19 Part 1

Characteristics of ED Dental Visits

Variable All Other ED Visits ED Dental Visits

ED Visits (n, row %) 730,330 (98%) 15,018 (2%)

Patient Characteristics

Age in Years (n, column%)

014 84429 (15%) 560 (3%)

1519 35187 (6%) 780 (5%)

2039 181939 (31%) 9907 (66%)

4064 173797 (30%) 3555 (24%)

65+ 104070 (18%) 190 (1%)

Male (n, column %) 329,764 (45%) 7470 (49.74%)

Race (n, column %)

White 471,196 (64.52%) 10,012 (66.67%)

Asian 7900 (1.08%) 45 (0.3%)

Black 28,916 (3.96%) 747 (4.97%)

Hispanic 4357 (0.6%) 93 (0.62%)

Native American 7177 (0.98%) 232 (1.54%)

Other 47,532 (6.51%) 609 (4.06%)

Missing 163,252 (22.35%) 3280 (21.84%)

Payer (n, column %)

Missing 1991 (0.27%) 92 (0.61%)

Other 43,923 (6.01%) 176 (1.17%)

Commercial 210,957 (29.11%) 1430 (9.52%)

Medicaid - Other States 3412 (0.47%) 108 (0.72%)

Medicare 166,883 (23.03%) 873 (5.81%)

Oregon Health Plan 173,827 (23.99%) 4930 (32.83%)

Uninsured 129,337 (17.85%) 7409 (49.33%)

Patient Zip Code Measures

Below Poverty Level: mean (std) 10.89 (9.17) 17.94 (20.25)

Completed High School: mean (std) 88.54 (7.2) 86.42 (9.4)

Unemployed: mean (std) 10.78 (8.62) 10.75 (5.97)

Hospital Characteristics

AHEC Region (n, column %)

Cascades East 24018 (3.29%) 453 (3.02%)

NE Oregon 25117 (3.44%) 499 (3.32%)

Pacifc 26,896 (3.68%) 403 (2.68%)

Portland 467,617 (64.03%) 8449 (56.26%)

SW Oregon 186,682 (25.56%) 5214 (34.72%)

Rural (n, column %) 140,331 (19.21%) 3346 (22.28%)

Critical Access Hospital (n, %) 53,552 (7.33%) 1292 (8.6%)

Appendix Table 4: Characteristics of ED Dental and Non-Dental Visits

20 Part 1

Primary Diagnosis ICD9 Code n %*

Unspecifed disorder of the teeth and supporting structures 525.9 6226 41.62

Periapical abscess without sinus 522.5 3477 23.24

Dental caries, unspecifed 521.00 2957 19.77

Acute apical periodontitis of pulpal origin 522.4 1093 7.31

Other dental caries 521.09 611 4.08

Disturbances in tooth eruption 520.6 127 0.85

Chronic gingivitis, plaque induced 523.10 82 0.55

Cracked tooth 521.81 61 0.41

Teething syndrome 520.7 54 0.36

Chronic periodontitis, unspecifed 523.40 44 0.29

Other specifed disorders of the teeth and supporting structures 525.8 37 0.25

Partial edentulism, unspecifed 525.50 29 0.19

Aggressive periodontitis, localized 523.31 23 0.15

Other specifed periodontal diseases 523.8 23 0.15

Acute gingivitis, plaque induced 523.00 22 0.15

Aggressive periodontitis, unspecifed 523.30 19 0.13

Acute periodontitis 523.33 15 0.1

Acquired absence of teeth, unspecifed 525.10 11 0.07

Pulpitis 522.0 9 0.06

Unspecifed gingival and periodontal disease 523.9 4 0.03

*denominator is all ED visits with primary non-trauma ED dental diagnosis who were discharged (denominator = 14,959)

Appendix Table 5: Top 20 Primary Dental Diagnoses, Discharged Patients

21 Part 1

Primary Diagnosis ICD9 Code n %*

Periapical abscess without sinus 522.5 44 74.58

Unspecifed disorder of the teeth and supporting structures 525.9 6 10.17

Acute apical periodontitis of pulpal origin 522.4 5 8.47

Aggressive periodontitis, unspecifed 523.30 1 1.69

Dental caries, unspecifed 521.00 1 1.69

Aggressive periodontitis, localized 523.31 1 1.69

Other specifed periodontal diseases 523.8 1 1.69

*denominator is all ED visits with primary non-trauma ED dental diagnosis who were admitted (denominator = 59)

Appendix Table 6: Top Primary Dental Diagnoses, Admitted Patients

22 Part 1

Secondary Dental Diagnosis ICD9 Code n %*

Unspecifed disorder of the teeth and supporting structures 5259 1014 34.14

Dental caries, unspecifed 52100 911 30.67

Periapical abscess without sinus 5225 517 17.41

Acute apical periodontitis of pulpal origin 5224 229 7.71

Acquired absence of teeth, unspecifed 52510 222 7.47

Partial edentulism, unspecifed 52550 166 5.59

Other dental caries 52109 91 3.06

Chronic gingivitis, plaque induced 52310 84 2.83

Teething syndrome 5207 74 2.49

Other specifed disorders of the teeth and supporting structures 5258 62 2.09

Disturbances in tooth eruption 5206 36 1.21

Complete edentulism, unspecifed 52540 32 1.08

Other specifed periodontal diseases 5238 23 0.77

Cracked tooth 52181 19 0.64

Chronic periodontitis, unspecifed 52340 12 0.4

Acute gingivitis, plaque induced 52300 11 0.37

Unspecifed gingival and periodontal disease 5239 10 0.34

Erosion, unspecifed 52130 6 0.2

Other loss of teeth 52519 5 0.17

Other and unspecifed diseases of pulp and periapical tissues 5229 3 0.1

*denominator is all ED visits with NO primary non-trauma dental diagnosis AND any secondary non-trauma dental

diagnosis (denominator = 2,970)

Appendix Table 7: Top 20 Secondary Dental Diagnoses, All Patients

This table includes patients who had a non dental primary diagnosis but with a secondary

diagnosis consistent with a non-traumatic dental problem.

23 Part 1

Primary Diagnosis ICD9 Code n %*

Other acute pain 33819 324 10.91

Other current conditions classifable elsewhere of mother, antepartum

condition or complication

64893 139 4.68

Open wound of tooth (broken) (fractured) (due to trauma), without

mention of complication

87363 115 3.87

Headache 7840 94 3.16

Cellulitis and abscess of face 6820 83 2.79

Swelling, mass, or lump in head and neck 7842 70 2.36

Other acute postoperative pain 33818 69 2.32

Unspecifed disease of the jaws 5269 53 1.78

Acute pharyngitis 462 49 1.65

Other and unspecifed diseases of the oral soft tissues 5289 42 1.41

Issue of repeat prescriptions V681 42 1.41

Fever, unspecifed 78060 40 1.35

Otalgia, unspecifed 38870 40 1.35

Acute upper respiratory infections of unspecifed site 4659 37 1.25

Unspecifed otitis media 3829 36 1.21

Unspecifed essential hypertension 4019 31 1.04

Open wound of lip, without mention of complication 87343 29 0.98

Migraine, unspecifed, without mention of intractable migraine without

mention of status migrainosus

34690 29 0.98

Syncope and collapse 7802 27 0.91

Nausea with vomiting 78701 26 0.88

*denominator is all ED visits with NO primary non-trauma dental diagnosis AND any secondary non-trauma dental diagnosis

(denominator = 2,970)

Appendix Table 7: (continued)

This table includes patients who had a non dental primary diagnosis but with a secondary diagnosis

consistent with a non-traumatic dental problem.

24 Part 1

Secondary Dental Diagnosis ICD9 Code n %*

Unspecifed disorder of the teeth and supporting structures 5259 975 36.06

Dental caries, unspecifed 52100 848 31.36

Periapical abscess without sinus 5225 443 16.38

Acquired absence of teeth, unspecifed 52510 214 7.91

Acute apical periodontitis of pulpal origin 5224 195 7.21

Partial edentulism, unspecifed 52550 158 5.84

Other dental caries 52109 80 2.96

Chronic gingivitis, plaque induced 52310 74 2.74

Teething syndrome 5207 72 2.66

Other specifed disorders of the teeth and supporting structures 5258 50 1.85

Disturbances in tooth eruption 5206 33 1.22

Complete edentulism, unspecifed 52540 22 0.81

Cracked tooth 52181 17 0.63

Other specifed periodontal diseases 5238 14 0.52

Chronic periodontitis, unspecifed 52340 11 0.41

Acute gingivitis, plaque induced 52300 10 0.37

Erosion, unspecifed 52130 6 0.22

Unspecifed gingival and periodontal disease 5239 5 0.18

Other loss of teeth 52519 4 0.15

Anodontia 5200 2 0.07

*denominator is all ED visits with NO primary non-trauma dental diagnosis AND any secondary non-trauma dental

diagnosis AND patient discharged (denominator = 2,704)

Appendix Table 8: Top 20 Secondary Dental Diagnoses, Discharged

This table includes patients who had a non dental primary diagnosis but with a secondary

diagnosis consistent with a non-traumatic dental problem.

25 Part 1

Primary Diagnosis ICD9 Code n %*

Other acute pain 33819 324 11.98

Other current conditions classifable elsewhere of mother, antepartum

condition or complication

64893 139 5.14

Open wound of tooth (broken) (fractured) (due to trauma), without

mention of complication

87363 115 4.25

Headache 7840 94 3.48

Other acute postoperative pain 33818 68 2.51

Swelling, mass, or lump in head and neck 7842 68 2.51

Cellulitis and abscess of face 6820 67 2.48

Unspecifed disease of the jaws 5269 53 1.96

Acute pharyngitis 462 49 1.81

Issue of repeat prescriptions V681 42 1.55

Other and unspecifed diseases of the oral soft tissues 5289 41 1.52

Otalgia, unspecifed 38870 40 1.48

Fever, unspecifed 78060 38 1.41

Acute upper respiratory infections of unspecifed site 4659 37 1.37

Unspecifed otitis media 3829 36 1.33

Unspecifed essential hypertension 4019 30 1.11

Migraine, unspecifed, without mention of intractable migraine without

mention of status migrainosus

34690 29 1.07

Open wound of lip, without mention of complication 87343 28 1.04

Hemorrhage complicating a procedure 99811 25 0.92

Nausea with vomiting 78701 25 0.92

*denominator is all ED visits with NO primary non-trauma dental diagnosis AND any secondary non-trauma dental diagnosis AND

patient discharged (denominator = 2,704)

Appendix Table 8: (continued)

This table includes patients who had a non dental primary diagnosis but with a secondary diagnosis

consistent with a non-traumatic dental problem.

26 Part 1

Secondary Dental Diagnosis ICD9 Code n %*

Periapical abscess without sinus 5225 74 27.82

Dental caries, unspecifed 52100 63 23.68

Unspecifed disorder of the teeth and supporting structures 5259 39 14.66

Acute apical periodontitis of pulpal origin 5224 34 12.78

Other specifed disorders of the teeth and supporting structures 5258 12 4.51

Other dental caries 52109 11 4.14

Complete edentulism, unspecifed 52540 10 3.76

Chronic gingivitis, plaque induced 52310 10 3.76

Other specifed periodontal diseases 5238 9 3.38

Partial edentulism, unspecifed 52550 8 3.01

Acquired absence of teeth, unspecifed 52510 8 3.01

Unspecifed gingival and periodontal disease 5239 5 1.88

Disturbances in tooth eruption 5206 3 1.13

Teething syndrome 5207 2 0.75

Cracked tooth 52181 2 0.75

Dental caries extending into pulp 52103 2 0.75

Loss of teeth due to caries 52513 2 0.75

Acute periodontitis 52333 1 0.38

Other and unspecifed diseases of pulp and periapical tissues 5229 1 0.38

Chronic periodontitis, unspecifed 52340 1 0.38

*denominator is all ED visits with NO primary non-trauma dental diagnosis AND any secondary non-trauma dental diagnosis

AND patient admitted (denominator = 266)

Appendix Table 9: Top 20 Secondary Dental Diagnoses, Admitted

This table includes patients who had a non dental primary diagnosis but with a secondary

diagnosis consistent with a non-traumatic dental problem.

27 Part 1

Primary Diagnosis ICD9 Code n %*

Cellulitis and abscess of face 6820 16 6.02

Cellulitis and abscess of oral soft tissues 5283 9 3.38

Syncope and collapse 7802 7 2.63

Coronary atherosclerosis of native coronary artery 41401 5 1.88

Diabetes with ketoacidosis, type I [juvenile type], uncontrolled 25013 4 1.5

Bipolar I disorder, most recent episode (or current) depressed,

unspecifed

29650 4 1.5

Pneumonia, organism unspecifed 486 4 1.5

Other chest pain 78659 4 1.5

Other and unspecifed noninfectious gastroenteritis and colitis 5589 3 1.13

Iron defciency anemia secondary to blood loss (chronic) 2800 3 1.13

Cellulitis and abscess of neck 6821 3 1.13

Cellulitis and abscess of oral soft tissues 528.3 3 1.13

Neutropenia, unspecifed 28800 3 1.13

Other bipolar disorders 29689 3 1.13

Acute systolic heart failure 42821 3 1.13

Major depressive afective disorder, recurrent episode, severe, without

mention of psychotic behavior

29633 2 0.75

Acute and subacute bacterial endocarditis 4210 2 0.75

Poisoning by antiallergic and antiemetic drugs 9630 2 0.75

Hyposmolality and/or hyponatremia 2761 2 0.75

Fever, unspecifed 780.6 2 0.75

*denominator is all ED visits with NO primary non-trauma dental diagnosis AND any secondary non-trauma dental diagnosis AND

patient admitted (denominator = 266)

Appendix Table 9: (continued)

This table includes patients who had a non dental primary diagnosis but with a secondary diagnosis

consistent with a non-traumatic dental problem.

28 Part 1

Appendix Table 10: Prescription Medications Dispensed After ED Dental Visit

Medication Class Frequency % ED Visits*

Analgesics - Opioid 14348 56%

Penicillins 9254 36%

Clindamycin 4120 16%

Analgesics - Anti-Infammatory 2242 9%

Antidepressants 678 3%

Antihistamines 671 3%

Mouth/Throat/Dental Agents 618 2%

Antianxiety Agents 520 2%

Macrolides 513 2%

Cephalosporins 462 2%

Anticonvulsants 399 2%

Ulcer Drugs 347 1%

Antiemetics 290 1%

Antiasthmatic and Bronchodilator Agents 283 1%

Musculoskeletal Therapy Agents 279 1%

Antipsychotics/Antimanic Agents 272 1%

Antihypertensives 237 1%

Corticosteroids 204 1%

Beta Blockers 157 1%

Analgesics - Nonnarcotic 151 1%

* denominator is 25,683 ED dental visits identifed in APAC

29 Part 1

Appendix Table 11: Procedures Associated With ED Dental Visits

CPT Code Description Frequency % ED Visits*

64400 Facial Nerve Block 1794 7%

85025 Blood Test: Cell Count 1239 5%

96375 Drug Injection- Subsequent Intravenous Push 867 3%

96372 Drug Injection- Subcutaneous or Intramuscular 843 3%

80053 Blood Test: Metabolic Panel 837 3%

96374 Drug Injection- Initial Intravenous Push 649 3%

96365 Intravenous Infusion 635 2%

36415 Vein Puncture 565 2%

J1170 Hydromorphone Injection 488 2%

J2405 Ondansetron Injection 481 2%

41800 Drainage of Dental Abscess from Dental Structure 478 2%

70450 Computed Tomography of Head or Brain 471 2%

* denominator is 25,683 ED dental visits identifed in APAC

30 Part 1

Appendix Figure 2: Number of ED Dental Visits in 2010 by Patient Residential Zip

Code, Oregon Health Plan Benefciaries (APAC)

Non-Traumatic OHP ED Dental Visits

0/Insufficient Data

1 - 3

4 - 12

13 - 33

34 - 264

Hospitals Locations Hospital Locations

31 Part 1

Appendix Figure 3: Number of ED Dental Visits in 2010 by Patient Residential Zip

Code, All Payers (Hospital Data)

Non-Traumatic ED Dental Visits (Weighted)

0/Insufficient Data

1 - 6

7 - 23

24 - 104

105 - 868

Hospitals Locations Hospital Locations

32 Part 1

Appendix Figure 4: Number of ED Dental Visits in 2010 by Patient Residential Zip

Code, Oregon Health Plan Benefciaries and Uninsured (Hospital Data)

Non-Traumatic OHP/Uninsured ED Dental Visits (Weighted)

0/Insufficient Data

1 - 5

6 - 20

21 - 92

93 - 778

Hospitals Locations Hospital Locations

33 Part 1

References

1. Centers for Disease Control. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2010 Emergency

Department summary Tables. 2012; http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/nhamcs_emergency/

2010_ed_web_tables.pdf. Accessed Dec 26, 2013.

2. Hong L, Ahmed A, McCunnif M, Liu Y, Cai J, Hof G. Secular trends in hospital emergency department

visits for dental care in Kansas City, Missouri, 20012006. Public Health Rep. MarApr 2011;126(2):210219.

3. Ladrillo TE, Hobdell MH, Caviness AC. Increasing prevalence of emergency department visits for

pediatric dental care, 19972001. J Am Dent Assoc. Mar 2006;137(3):379385.

4. Lee HH, Lewis CW, Saltzman B, Starks H. Visiting the emergency department for dental problems: trends

in utilization, 2001 to 2008. American journal of public health. Nov 2012;102(11):e7783.

5. Anderson L, Cherala S, Traore E, Martin NR. Utilization of Hospital Emergency Departments for non-

traumatic dental care in New Hampshire, 20012008. Journal of community health.

Aug 2011;36(4):513516.

6. Wall T. Recent trends in dental emergency department visits in the United States:1997/1998 to

2007/2008. Journal of public health dentistry. Summer 2012;72(3):216220.

7. Nalliah RP, Allareddy V, Elangovan S, Karimbux N. Hospital based emergency department visits

attributed to dental caries in the United States in 2006. The journal of evidence-based dental practice.

Dec 2010;10(4):212222.

8. Pennycook A, Makower R, Brewer A, Moulton C, Crawford R. The management of dental problems

presenting to an accident and emergency department. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine.

Dec 1993;86(12):702703.

9. Pajewski NM, Okunseri C. Patterns of dental service utilization following nontraumatic dental condition

visits to the emergency department in Wisconsin Medicaid. Journal of public health dentistry. Aug 8 2012.

10. Davis EE, Deinard AS, Maiga EW. Doctor, my tooth hurts: the costs of incomplete dental care in the

emergency room. Journal of public health dentistry. Summer 2010;70(3):205210.

11. Hocker MB, Villani JJ, Borawski JB, et al. Dental visits to a North Carolina emergency department: a

painful problem. North Carolina medical journal. SepOct 2012;73(5):346351.

12. Wallace NT, Carlson MJ, Mosen DM, Snyder JJ, Wright BJ. The individual and program impacts of

eliminating Medicaid dental benefts in the Oregon Health Plan. American journal of public health.

Nov 2011;101(11):21442150.

13. Cohen LA, Manski RJ, Hooper FJ. Does the elimination of Medicaid reimbursement afect the frequency

of emergency department dental visits? J Am Dent Assoc. May 1996;127(5):605609.

14. Dorfman DH, Kastner B, Vinci RJ. Dental concerns unrelated to trauma in the pediatric emergency

department: barriers to care. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. Jun 2001;155(6):699703.

15. Oregon Health Plan Medicaid Demonstration. Capitation Rate Development. Dental Care Organizations

Remaining During Transition to Coordinated Care Organizations. In: Actuarial Service Unit OHA, ed2013:149.

16. Cohen LA, Manski RJ, Magder LS, Mullins CD. Dental visits to hospital emergency departments by adults

receiving Medicaid: assessing their use. J Am Dent Assoc. Jun 2002;133(6):715724; quiz 768.

34 Part 1

17. Lewis C, Lynch H, Johnston B. Dental complaints in emergency departments: a national perspective.

Annals of emergency medicine. Jul 2003;42(1):9399.

18. Lowe RA. Dental and mental conditions in rural Oregon emergency departments. 23rd Annual Oregon

Rural Health Conference. Newport, Oregon2006.

19. Mullins CD, Cohen LA, Magder LS, Manski RJ. Medicaid coverage and utilization of adult dental services.

J Health Care Poor Underserved. Nov 2004;15(4):672687.

20. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Overview of the State Emergency Department Databases.

Accessed 2/20/14. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/seddoverview.jsp

21. Muennig P. Cost-Efectiveness Analysis in Health: A Practical Approach. San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons;

2008.

35 Part 2

PART 2

Background

Recent U.S. data suggest signifcant increases in the number of patients utilizing the ED for treatment of

non-traumatic dental conditions (NTDCs) (Lee et al. 2012; Okunseri et al 2012). Studies have identifed

various factors related to NTDC-related ED use (e.g., low-income, racial/ethnic minority status, being insured

by Medicaid, having no insurance, and living in a Health Professional Shortage Area) (Hong et al. 2011;

Okunseri et al. 2008). Young adults ages 20 to 30 years appear to use the ED for NTDCs at higher rates than

other individuals (Chi et al. 2014). No studies to date have used qualitative methods to examine stakeholder

and patient perspectives on NTDC-related ED use and to identify possible strategies to reduce and prevent

ED visits.

The goals of this study were to identify the multilevel determinants of NTDC-related ED use, poll

stakeholders on potential solutions that could be implemented to reduce NTDC-related ED use, generate

a preliminary conceptual model on ED use, and distill research fndings into prevention-oriented policy

recommendations aimed at preventing ED use for NTDCs. We achieved these goals by collecting qualitative

interview data from a sample of community stakeholders and patients in Oregon. This study will help our

team plan future studies that test interventions that reduce and prevent NTDC-related ED use.

36 Part 2

Data

Location and Study Participants

We focused on 6 communities in Oregon State (5 rural and 1 urban). These communities had a history of

participating in research through the Oregon Rural Practice-based Research Network (ORPRN). From these

communities, we recruited a purposive sample of community stakeholders (N=34) and individuals with a

history of ED use for NTDCs (N=17) (Table 1). Community stakeholders were recruited through hospitals

and local dental societies. We used snowball techniques to identify additional stakeholders. The stakeholder

group included ED staf (physicians, nurses, and managers), hospital administrators, dental society leaders

and dentists, non-proft health program executives, and other relevant stakeholders. Patients were recruited

from hospitals and safety net dental clinics.

Data Collection

We generated preliminary 12-item interview scripts for stakeholders and ED utilizers. Cognitive interviewing

methods were used to pre-test the scripts with representative stakeholders and patients. The scripts were

modifed to improve clarity and fow. The scripts were used to train three interviewers. Study participants

were consented and received a $25 gift card as an incentive. Each interview was conducted in person or by

phone and digitally recorded. The study was approved by the University of Washington institutional review

board.

Data Management and Analyses

The digital data were transcribed by a professional medical transcription service. Each transcribed interview

was compared to the digital fle to ensure accuracy. A codebook was created that included three main

domains: 1) perceptions of NTDC-related ED use as a problem; 2) determinants of NTDC-related ED use;

and 3) potential solutions to reduce and prevent NTDC-related ED use. Stakeholder and patient data were

analyzed separately. For the stakeholder data, three trained Research Assistants coded a random sample

of three stakeholder transcripts to establish inter-coder agreement through subjective assessment, a

standard practice in qualitative methods. Discrepancies between the coders were discussed with a fourth

coder and resolved. The remaining 31 transcripts were divided among the three coders. Each transcript

was individually read and coded by two diferent coders using NVivo 8 qualitative data analysis software

(QSR International Pty Ltd, Victoria, Australia) to assign thematic codes to segments of the transcript text.

The two coded versions of each transcript were merged. An identical process was used to code the patient

transcripts. Based on the fndings, we generated a preliminary conceptual model of NTDC-related ED use.

37 Part 2

Main Findings

NTDC-Related ED Visits are a Problem

A number of ED health care providers and hospital administrators stated that NTDC-related ED visits were

not a problem. The main reason was the few number of patients presenting with NTDCs. It appears that

some hospital EDs see a low volume of NTDCs and less dental pain than we used to. However, there were

noted inconsistencies within communities. One potential reason is that EDs do not typically track the

number of NTDCs. In response to an ED health providers complaints about NTDCs, a regional medical center

CEO recently looked into how many dental charges I was doing and in one year discovered it was $750,000

out of a 25-bed hospitalthat was astounding. I had no ideaWe just hadnt noticed.

Other interviewees, including a community organizer, saw NTDC-related ED visits as a big problem.

One female ED patient reported that the ED physician who treated her commented on how there are more

and more people coming into the emergency room for teeth problems. A Registered Nurse with eight years

of clinical experience in the ED estimated that three to ten patients with NTDCs would present to the ED

each day. She commented that NTDCs can really screw up your fow of getting patients in and taking care

of them. An ED Director noted that triaged patients with NTDCs can cause problems in the waiting areas,

particularly when patients have been waiting for up to six hours. They become unhappy with the situation

and are vocal about it, so anybody else who is waiting [starts to develop] a negative overtone. With the

exception of occasional [drug] seekers in the ED who present with the excuse of dental pain but nothing

wrong in the mouth, patients with NTDCs really do have problems with their teeth.

All ED staf and local dentists agreed that care provided in the ED is non-defnitive, usually a combination

of administering a dental nerve block and prescribing analgesics and/or antibiotics. A number of patients

reported that a lot of times [the treating provider doesnt] wont even really look in your mouth and one

patient recalled her ED physician was annoyed at the fact that I was there for my teeth. ED clinicians

reported not having sufcient training, space, or equipment to treat NTDCs. While one ED clinic manager

stated that ED patients need to take responsibility for their own healthcare, which includes their dental

care, most ED staf were sympathetic. An ED Nurse Manager stated that it is a struggle to treat [patients

with NTDCs]you want to treat their pain. An ED physician admitted that we are not getting at the heart of

the issue, which leads to repeat ED visits over time by the same patient, also known as frequent fyers.

A young mother who reported visiting the ED two or three times for NTDCs commented that the ED staf

dont really know what theyre doing with teethor I dont think they really want to deal with itI think

they have more pressing matters. Another mother of two children, who recently went to the ED with an

NTDC as a last option, recalled that

Through the years, [dentists] have told me that [tooth decay] can fester into a bad infection and then it can actually

kill you. Soif you are that bad you need to go to the ER [emergency room]. But, then you get to the ER and they dont

know what to do. Okay, well give her something for pain, thats all we can do. They dont even refer you somewhere.

Just go to the dentist. Thats all they say. Thats pretty much going in circles. Going around and around. Its like I cant

[go to a dentist] cause I cant aford it.

The determinants of NTDC-related ED visits are multilevel and multifactorial

Health System

According to a patient who has utilized the ED multiple times in the past fve years, one reason for NTDC-

related ED visits is federal legislation that ensures access to emergency health care services regardless of an

individuals ability to pay. This retired, uninsured father of a 5-year old child said the person that needs the

help doesnt have money to pay for the [dental] care. The problem with the emergency room is that I know

38 Part 2

that if I have an emergency they have to give me care. They cant deny me. There is a law whether I have

money or not.

Stakeholders believed that a disjointed medical and dental care system prompted many patients to seek

care in the ED. It is not an integrated health solution. It [oral health] is a separate health issue. It is like your

mouth is somehowdiferentthan the rest of your body so I see it is as being treated separately...Dentistry

[is] an afterthought.

Interviewees specifcally raised problems with the Oregon Medicaid program, particularly in terms of dental

service coverage. A non-proft executive said that Medicaid in Oregon is a mirage beneft. A dental society

president who practices at a corporate dental clinic said you just get emergency. Thats it. They will not

cover fllings. Theyonly cover emergencies. A dental clinic coordinator stated that Medicaid will pay a

visit to a provider or to an ER for a dental-related problem, but not pay for the visit to the dentists ofce to

have that problem taken care of. Similarly, a general dentist working at a community health center stated

As soon as that emergency is treated, they wont cover other things which can help prevent the problems from

happening in the frst place.

A quote from an ED manager, who mistakenly believed that the Oregon Health Plan covered dental care for

adults, illustrates that some providers are confused about dental coverage and may blame the victim, the

patient who does not have access to dental care:

[most of] our patientsare on Medicaid. I dont think they understand that they have dental coverage, so some

of them have emergency dental coverage. Some of them have regular dental coverage where they can go and get

cleanings and things like this and I think they just are undereducated on what kind of coverage they have and who to

contact.

In the broader context of federal health care and state-level Medicaid reforms, a hospital director pointed

out that problems with dental provider shortages:

about 16,000 new patients [in my region]will be eligible for the Oregon Health PlanBefore it was just

emergency care for dental servicesand now [enrollees] will be eligible for exams, extractions, fllings, and cleanings

annually. So, whos going to be taking care of all these patients if you have a dentist shortage already and how are

the Dental Care Organizations preparing for that?...Who is going to care for them and how many dentists do we have

that we are going to be able to provide this coverage? Its a big job.

This hospital director went on to explain that dental insurance reform is not likely to completely eliminate

NTDC-related ED visits.

even with the Afordable Care Act and insurance exchanges, you aregoing to have a population of uninsured

people who will not qualify for coverage that are going to be coming to our emergency departments to get dental

needs metThere are going to be families who dont meet the eligibility requirementWe need to make certain we

are ready to handle that.

Community

There were three community-level factors stakeholders reported as being related to NTDC-related ED visits.

The frst was the absence of urgent care clinics. In one community, an ED charge nurse noted a lot that

could be treated at an urgent careend up coming to the emergency roomFrequently these patients