Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Acanthosis Nigricans

Transféré par

Zeliha TürksavulDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Acanthosis Nigricans

Transféré par

Zeliha TürksavulDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Official reprint from UpToDate

www.uptodate.com 2014 UpToDate

Author

Inbal Braunstein, MD

Section Editor

Jeffrey Callen, MD, FACP, FAAD

Deputy Editor

Abena O Ofori, MD

Acanthosis nigricans

All topics are updated as new evidence becomes available and our peer review process is complete.

Literature review current through: Apr 2014. | This topic last updated: Mar 26, 2014.

INTRODUCTION Acanthosis nigricans is a common condition characterized by velvety, hyperpigmented

plaques on the skin. Intertriginous sites, such as the neck and axillae, are common sites for involvement. Less

frequently, acanthosis nigricans appears in other skin sites or on mucosal surfaces.

Clinical recognition of acanthosis nigricans is important because the disorder can occur in association with a

variety of systemic abnormalities, many of which are characterized by insulin resistance. Obesity and diabetes

mellitus are among the most frequently associated disorders. Rarely, acanthosis nigricans develops as a sign of

internal malignancy.

The epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of acanthosis nigricans will be reviewed here. Specific disorders

that may present with acanthosis nigricans are reviewed in greater detail separately.

EPIDEMIOLOGY Acanthosis nigricans can affect both males and females, as well as infants, children, and

adults. Although prevalence rates of this disorder have varied among studies, it is evident that a significant

proportion of obese and diabetic individuals exhibit this finding, and that the prevalence of this disorder may differ

among ethnic groups [1-12]. In the United States, acanthosis nigricans appears to be more common in people

of Native American, African-American, and Hispanic origin than in white or Asian individuals [1,5-10,13,14].

Examples of studies that have evaluated the prevalence of acanthosis nigricans in the United States include the

following:

Increasing obesity rates are an additional factor in the prevalence of acanthosis nigricans, notably in pediatric

populations [16]; however, differing rates of obesity cannot solely account for different prevalence of acanthosis

nigricans between racial groups [8]. (See 'Obesity, endocrine, and metabolic disorders' below.)

ETIOLOGY Acanthosis nigricans may be acquired or inherited. Most, if not all, patients with acanthosis

nigricans have one of the following categories of disorders:

In a multiethnic cross-sectional study of 1730 patients aged 7 to 65 years seen in primary care settings in

a variety of sites within the United States in 2007, 19 percent had acanthosis nigricans [15].

A study of 618 children (ages 7 to 17 years) in an urban community in Illinois performed between 2001 and

2002 found that Caucasian youth were less likely than African-American or Hispanic youth to have

acanthosis nigricans on the neck [10]. In the study, 4, 19, and 23 percent of children had acanthosis

nigricans, respectively.

Among 2200 Native Americans in the Cherokee Nation (ages 5 to 40 years) evaluated between 1995 and

1999, 34 percent had acanthosis nigricans on the neck [14].

Obesity

Endocrine and metabolic disorders, particularly disorders associated with insulin resistance

Genetic syndromes with acanthosis nigricans

Familial acanthosis nigricans

Malignancy

Obesity, endocrine, and metabolic disorders Obesity and diabetes mellitus are the most common

medical disorders linked with acanthosis nigricans [1-3,5,8,17,18].

Insulin resistance likely accounts for the development of acanthosis nigricans in individuals with these

conditions (see 'Pathogenesis' below). In one study of 236 children with acanthosis nigricans and 51 overweight

children without the disorder, significant associations of acanthosis nigricans with insulin resistance and

abnormal glucose homeostasis were detected [19]. (See "Insulin resistance: Definition and clinical spectrum".)

Genetic syndromes Multiple genetic disorders have been associated with acanthosis nigricans, many of

Drug reactions

Obesity The link between acanthosis nigricans and weight was demonstrated in a study of 1133 young

patients from multiple communities in the United States in which the prevalence of acanthosis nigricans

increased with rising body mass index (BMI) [11]. Among subjects aged 7 to 19 years who were of normal

weight, overweight, or obese, acanthosis nigricans was detected in 3, 11, and 51 percent, respectively. An

increase in acanthosis nigricans with rising weight was also evident among slightly older subjects (ages

20 to 39 years); 3, 12, and 37 percent of subjects in the respective weight groups within this population

were affected. Concordantly, a smaller practice-based study found a high rate of acanthosis nigricans in

obese children; among children aged 7 to 17 years with a BMI that met or exceeded the 98 percentile,

62 percent had the skin condition [10]. (See "Measurement of growth in children", section on 'Body mass

index (BMI)'.)

th

Diabetes Type 2 diabetes mellitus is also strongly associated with acanthosis nigricans [2,6,11,15,17].

In the study of 1133 patients mentioned above, type 2 diabetes was present in 15 percent of patients with

acanthosis nigricans, compared with 4 percent of patients without the skin condition [11]. After controlling

for age, BMI, and number of diabetes risk factors, patients with acanthosis nigricans were twice as likely

to have type 2 diabetes as unaffected individuals.

In addition, a practice-based study with 1730 patients supported the association between type 2 diabetes

and acanthosis nigricans [15]. Type 2 diabetes was present in 35 versus 18 percent of patients with or

without acanthosis nigricans, respectively. Significantly higher serum levels of insulin were also detected

in the patients with acanthosis nigricans.

The prevalence of acanthosis nigricans in a population of patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes

was evaluated in a study of 216 adults in Texas in 1998 and 1999. In the study, acanthosis nigricans was

detected in 36 percent [6]. The likelihood of having acanthosis nigricans increased with the degree of

obesity, with over 50 percent of individuals with a BMI 30 mg/m demonstrating the disorder. Ethnic

differences were also evident; 50 of 95 African-American subjects (53 percent), 28 of 78 Latin-American

subjects (36 percent), 1 of 39 non-Hispanic white subjects (3 percent), and none of four Asian subjects

were affected [6]. (See 'Epidemiology' above and "Screening for and clinical evaluation of obesity in

adults", section on 'Measurement of BMI'.)

2

Polycystic ovarian syndrome Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) is associated with insulin

resistance and hyperinsulinemia, and studies suggest 5 to 33 percent of women with PCOS have

acanthosis nigricans [20,21]. Acanthosis nigricans can be seen in women with PCOS with normal BMI

and is significantly associated with insulin resistance and reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

[22].

Other disorders In a 2007 cohort of middle-aged Sri Lankan adults, acanthosis nigricans was present in

296 of 1025 subjects with metabolic syndrome (29 percent) and only 217 of 1924 subjects without the

syndrome (11 percent) [2]. In addition, hypertension and dyslipidemia, components of the metabolic

syndrome, have been linked to acanthosis nigricans in children [18,19,23-25].

Examples of other metabolic or endocrine disorders associated with acanthosis nigricans include

acromegaly and Cushings syndrome [26]. (See "The metabolic syndrome (insulin resistance syndrome or

syndrome X)".)

which are characterized by insulin resistance that results either from defects in the insulin receptor or the

production of antibodies against the insulin receptor. Acanthosis nigricans is a clinical feature that can aid in the

recognition of these genetic diseases [27]. Some, but not all, patients with acanthosis nigricans with onset in

infancy or early childhood, develop the condition as a feature of a genetic disorder [27,28].

Examples of genetic syndromes characterized by insulin resistance that can present with acanthosis nigricans

include Down syndrome, leprechaunism, Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome, congenital generalized lipodystrophy

(Berardinelli-Seip syndrome), familial partial lipodystrophy, and Alstrom syndrome [29,30]. Cutis gyrata

syndrome, Crouzon syndrome with acanthosis nigricans, thanatophoric dysplasia, Costello syndrome, and

severe achondroplasia with developmental delay and acanthosis nigricans (SADDAN) are additional genetic

syndromes that are not characterized by insulin resistance, but may also present with acanthosis nigricans

[29,31]. (See "Insulin resistance: Definition and clinical spectrum" and "Lipodystrophic syndromes", section on

'Congenital generalized lipodystrophy' and "Lipodystrophic syndromes", section on 'Familial partial

lipodystrophy' and "Craniosynostosis syndromes", section on 'Crouzon syndrome' and "Prenatal diagnosis of

the lethal skeletal dysplasias", section on 'Thanatophoric dysplasia'.)

Familial Documentation of familial, non-insulin resistance-related, nonsyndromic forms of acanthosis

nigricans are limited to reports of a few families and involve mutations in FGFR3 (fibroblast growth factor

receptor 3) [28]. The inheritance pattern is usually autosomal dominant, and the clinical findings are typically

first detected in infancy. A Pakistani family with isolated familial acanthosis nigricans with an autosomal

recessive inheritance pattern has been reported [32].

Malignancy Rarely, acanthosis nigricans occurs as a paraneoplastic disorder [33-35]. Abdominal

adenocarcinomas, particularly gastric adenocarcinomas, represent the majority of acanthosis nigricans-

associated tumors [35-39]. Patients may concurrently develop the sign of Leser-Trlat or tripe palms, which are

additional cutaneous disorders that can occur in association with internal malignancy. (See "Cutaneous

manifestations of internal malignancy", section on 'Acanthosis nigricans' and "Cutaneous manifestations of

internal malignancy", section on 'Tripe palm' and "Cutaneous manifestations of internal malignancy", section on

'Sign of Leser-Trelat'.)

Malignancy-associated acanthosis nigricans is extremely rare in children. Several cases in which children

developed acanthosis nigricans in conjunction with gastric adenocarcinoma, Wilms tumor, or osteogenic

sarcoma have been documented [16].

Medications Infrequently, acanthosis nigricans develops as a side effect of drug exposure. This most

commonly occurs in the setting of medications that promote hyperinsulinemia. Medications that have been

associated with acanthosis nigricans include systemic glucocorticoids [33], injected insulin [40], oral

contraceptives [41], niacin [42], protease inhibitors [43], palifermin (a recombinant human keratinocyte growth

factor used to manage severe chemotherapy-induced mucositis) [44,45], testosterone [46], and aripiprazole

[47].

PATHOGENESIS The pathways that lead to acanthosis nigricans are not well understood. Abnormalities

involving three types of tyrosine kinase receptors, insulin-like growth factor receptor-1 (IGFR1), fibroblast growth

factor receptors (FGFR), and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), have been proposed as potential

contributing factors [29].

The association of acanthosis nigricans with multiple disorders characterized by insulin resistance suggests

that hyperinsulinemia plays a key role in the development of acanthosis nigricans. Elevated levels of insulin may

stimulate keratinocyte and dermal fibroblast proliferation via interaction with IGFR1, resulting in the plaque-like

lesions that typify the disorder [29]. Acanthosis nigricans related to genetic syndromes of insulin resistance,

obesity, diabetes mellitus, or other disorders associated with insulin resistance may be attributable to this

theory (see 'Etiology' above). These theories are supported by the finding of inherited form of acanthosis

nigricans due to a homozygous mutation in the insulin receptor gene [32].

Other mechanisms may also be involved in acanthosis nigricans, particularly in cases in which insulin

resistance is absent. As an example, mutations in certain FGFRs may contribute to acanthosis nigricans

through the promotion of keratinocyte proliferation and survival [29]. Activating mutations in FGFR3 have been

linked to several inherited syndromes that present with acanthosis nigricans, including Crouzon syndrome,

severe achondroplasia with developmental delay, SADDAN, and thanatophoric dwarfism [28]. In addition,

FGFR3 mutations were identified in a family with familial acanthosis nigricans [28], and at least two patients

with malignancy-associated skin lesions [48].

Transforming growth factor (TGF)-, a cytokine that may exert proliferative effects via activation of EGFR, may

also contribute to the development of malignancy-associated acanthosis nigricans [49,50]. In support of this

theory is a report of a patient in whom reduction of elevated serum TGF- levels and amelioration of acanthosis

nigricans followed the removal of a malignancy [50].

The mechanisms by which other forms of acanthosis nigricans occur remain elusive. The predominant

distribution of acanthosis nigricans in skin folds suggests a contributory role for friction or irritation in the

disorder, but this has not been scientifically proven.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS Acanthosis nigricans typically presents with thickened, velvety to verrucous,

grey-brown hyperpigmented plaques on the skin. The back of the neck, sides of the neck, and axillae are the

most common sites of involvement (picture 1A-E). Other intertriginous areas, such as the anogenital region and

the inframammary, abdominal, antecubital, and inguinal skin folds, are less frequently affected (picture 2).

Additionally, severe cases may demonstrate lesions on the areola, perineum, umbilicus, lips, buccal or other

mucosa, and other non-intertriginous areas (picture 3A-C) [33].

In mild or early acanthosis nigricans, affected skin has a dirty appearance and a rough or dry texture with

minimal plaque-like elevation. As the lesions progress, the skin becomes thicker and demonstrates

accentuation of dermatoglyphics (skin lines) and papillomatous projections. Acrochordons (skin tags) may be

present within or around affected areas (picture 1E). Unlike cutaneous lesions, mucosal acanthosis nigricans

usually does not demonstrate hyperpigmentation.

Acanthosis nigricans typically develops in a symmetrical distribution. Unilateral cases of acanthosis nigricans

may instead represent a variant of epidermal nevus [51-54].

An acral form of acanthosis nigricans, characterized by hyperpigmented plaques on the knuckles of the hands,

elbows, knees, or feet, and most commonly seen in individuals of sub-Saharan African origin, has also been

described (picture 4) [16,33,55]. The term acral acanthotic anomaly has been used to refer to these lesions

[56].

Acanthosis nigricans is usually asymptomatic. However, lesions in skin folds that become macerated and

inflamed may become uncomfortable or malodorous. In particular, this may occur in the setting of secondary

bacterial colonization or yeast infection.

Malignancy-associated acanthosis nigricans The paraneoplastic form of acanthosis nigricans is most

frequently diagnosed in older individuals and patients often are not obese. The lesions can arise before or after

the detection of malignancy. In some cases, the diagnosis of acanthosis nigricans predates recognition of the

malignancy by years [38,57,58].

Features that suggest the possibility of an underlying malignancy in a patient with acanthosis nigricans include

the following:

Malignancy-associated acanthosis nigricans may be accompanied by localized or generalized pruritus [33]. In

addition, other paraneoplastic dermatoses may occur with malignancy-associated acanthosis nigricans, such

Rapid onset of skin lesions

Additional paraneoplastic findings (eg, rapid growth or inflammation of seborrheic keratoses [the sign of

Leser-Trlat] or the presence of tripe palms)

Extensive involvement

Lesions in atypical sites (eg, mucous membranes, palms, or soles)

Unexplained weight loss

Older adult

as velvety to rugose thickening of the palmar skin (tripe palms) (picture 5) and the eruptive onset of multiple

seborrheic keratoses (sign of Leser-Trlat) [59]. (See "Cutaneous manifestations of internal malignancy",

section on 'Acanthosis nigricans' and "Cutaneous manifestations of internal malignancy", section on 'Tripe palm'

and "Cutaneous manifestations of internal malignancy", section on 'Sign of Leser-Trelat'.)

HISTOPATHOLOGY Hyperkeratosis and epidermal papillomatosis are the major pathological features, and

acanthosis is relatively mild. The hyperkeratosis is primarily responsible for the clinical finding of cutaneous

hyperpigmentation; however, increased melanin in the basal layer of the epidermis also is sometimes detected

[60].

The dermis may demonstrate a mild infiltrate with lymphocytes, plasma cells and, occasionally, a few

neutrophils. However, inflammation is not a prominent feature. Biopsies of mucosal lesions exhibit mild

parakeratosis with epidermal hyperplasia and papillomatosis [61].

The histological features of acanthosis nigricans are consistent among the various forms of the condition. For

example, microscopy cannot be used to distinguish paraneoplastic acanthosis nigricans from other types of

acanthosis nigricans.

DIAGNOSIS AND PATIENT EVALUATION The clinical examination is usually sufficient to establish a

diagnosis of acanthosis nigricans. In the rare cases in which the diagnosis is uncertain, a skin biopsy can be

performed to confirm the clinical impression. (See 'Histopathology' above.)

Due to the association of acanthosis nigricans with other abnormalities, the assessment for signs or symptoms

of other disorders is an important component of the evaluation of affected patients [62]. In general, we proceed

with the following work-up in children and adults with acanthosis nigricans:

Patient history

Age of onset (onset in infancy or early childhood suggests the possibility of a syndromic or familial

disorder, and malignancy-associated acanthosis nigricans is more common in adults than in

children)

History or symptoms suggestive of an underlying endocrinopathy (this information may help to

identify the presence of type 2 diabetes, polycystic ovarian syndrome, acromegaly, Cushings

syndrome, or other endocrine disorders)

Family history of acanthosis nigricans (in the absence of other underlying causes, may suggest

familial acanthosis nigricans)

Possible exposure to drugs that may induce acanthosis nigricans (See 'Medications' above.)

Physical examination

Height and weight (used to establish the presence or absence of obesity, a common cause of

acanthosis nigricans)

Growth rate in children (abnormal growth may suggest the presence of an endocrinopathy or

genetic syndrome)

Physical signs suggestive of an underlying endocrinopathy (may help to identify the presence

of type 2 diabetes, polycystic ovarian syndrome, acromegaly, Cushings syndrome, or other

endocrine disorders)

Blood pressure assessment (assesses for hypertension, which may occur at increased frequency

in patients with acanthosis nigricans)

Laboratory studies Patients with acanthosis nigricans should be evaluated for the possibility of

diabetes mellitus. (See "Screening for type 2 diabetes mellitus", section on 'Screening tests'.) Additional

laboratory studies and other investigational tests are ordered based upon the findings on history and

physical examination and suspicion for specific disorders. For example, women with features that suggest

polycystic ovarian syndrome should be evaluated for this condition. (See "Diagnosis of polycystic ovary

The possibility of an occult malignancy should always be considered in older, non-obese adults with new-onset

acanthosis nigricans without another identifiable cause and/or clinical features suggestive of malignancy-

associated acanthosis nigricans. (See 'Malignancy-associated acanthosis nigricans' above.) However, there is

little consensus on the appropriate cancer evaluation in such patients. At minimum, patients should be

evaluated with a thorough review of symptoms, a complete physical examination, and age-appropriate cancer

screening. Because many of the associated tumors involve the gastrointestinal tract, referral to gastroenterology

is indicated.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS Multiple other cutaneous disorders share features with acanthosis nigricans.

The possibility of such disorders should be considered in patients with lesions that are not classic for

acanthosis nigricans.

Other diagnostic considerations include pregnancy-associated hyperkeratosis of the nipple [63], Hailey-Hailey

disease (picture 10A-C) (which is distinguished by the presence of inflammatory and erosive intertriginous

plaques), pellagra (which can present with hyperpigmented plaques on the neck and other sun-exposed areas),

and cutaneous hyperpigmentation related to Addisons disease.

TREATMENT Since acanthosis nigricans is a benign, often asymptomatic disorder, cosmetic concerns are

typically the primary indications for treatment. Treatment of the underlying cause, when feasible, is the preferred

method of management, and obesity-related, drug-induced, and malignancy-associated acanthosis nigricans

appear to frequently respond well to this intervention. In contrast, the likelihood for clinically significant

improvement in acanthosis nigricans following the treatment of insulin resistant states is less certain [64].

For patients in whom reversal of the underlying cause of acanthosis nigricans is impossible, in whom the degree

of improvement is unsatisfactory, or who desire accelerated improvement in the cosmetic appearance of lesions,

topical therapies that normalize epidermal proliferation, such as topical retinoids and topical vitamin D analogs,

may be of benefit. Systemic retinoids have also been utilized for this indication, but are not indicated for the

treatment of most patients.

Patient with acanthosis nigricans sometimes attempt to improve the appearance of lesions through excessive

scrubbing of the affected skin during bathing. Such behavior should be discouraged, since it may result in

lichenification (thickening of the skin) and worsening hyperpigmentation.

Treatment of underlying disorders

Obesity Weight loss has been linked to improvements in acanthosis nigricans in obese patients [65,66].

syndrome in adults" and "Definition, clinical features and differential diagnosis of polycystic ovary

syndrome in adolescents" and "Insulin resistance: Definition and clinical spectrum", section on 'Clinical

spectrum'.)

Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis of Gougerot and Carteaud This is an uncommon

disorder that typically affects young adults. Reticulated, hyperpigmented, and slightly scaly plaques occur

on the neck, chest (especially inframammary chest), and upper back (picture 6A-B).

Granular parakeratosis Granular parakeratosis is a disorder characterized by the appearance of

hyperkeratotic brown-red papules that coalesce to form plaques (picture 7). Although the axilla is the most

common site for involvement, the disorder may also occur in other intertriginous sites. Pruritus is typically

present.

Linear epidermal nevus Epidermal nevi are benign hamartomatous growths that are usually present at

birth or become evident during the first year of life. The skin lesions are well-defined and often linear

hyperpigmented, papillomatous plaques (picture 8). Epidermal nevi may become more prominent over

time.

Reticulated pigmented anomaly of the flexures (Dowling-Degos disease) This is a rare,

autosomal dominant disorder that presents with reticulated hyperpigmentation that has a predilection for

flexural areas (picture 9). Lesions typically appear in early adulthood. Some patients also exhibit

comedones and pitted facial scars.

We support and encourage weight loss efforts in patients with obesity-related acanthosis nigricans. (See

"Overview of therapy for obesity in adults" and "Management of childhood obesity in the primary care setting".)

Insulin resistance Agents that improve insulin sensitivity, such as metformin and rosiglitazone, may

have some benefit for acanthosis nigricans related to insulin resistance [64,67-72]. A small, unblinded, non-

placebo-controlled, 12-week randomized trial that compared metformin to rosiglitazone in overweight and obese

patients with acanthosis nigricans found no significant change in lesion severity, and only modest improvement

in skin texture [68]. In a separate uncontrolled study, subjective improvement in acanthosis nigricans was noted

in three out of five adolescents and adults with insulin resistance or diabetes who were treated with metformin

for six months [69]. Additional studies are necessary to explore the efficacy and safety of such agents in the

treatment of acanthosis nigricans.

Drugs Medications associated with the onset of acanthosis nigricans should be discontinued if medically

feasible. Discontinuation of the inciting drug often results in the resolution of the skin lesions [16]. (See

'Medications' above.)

Malignancy Treatment of the underlying malignancy is the preferred therapeutic intervention for patients

with malignancy-associated acanthosis nigricans. Improvement or resolution of acanthosis nigricans has been

reported in multiple patients following successful treatment of the associated malignancy [16,37-39,73-76].

Other interventions Other therapies that have been associated with improvement of acanthosis

nigricans in isolated patients include octreotide in an obese adolescent [77], and fish oil supplementation in a

patient with a lipodystrophic form of diabetes [78].

Skin-directed therapy Data on the efficacy of therapies aimed at directly improving the skin lesions of

acanthosis nigricans are limited to case reports and documentation of clinical experience. Although

improvement has been reported with several topical and systemic agents, the optimal approach to treatment,

the likelihood for treatment success, and the long-term efficacy of these interventions remains unknown.

Topical agents, such as topical retinoids, vitamin D analogs, and keratolytics are the primary agents used in the

treatment of localized lesions. Topical therapy is impractical for the management of patients with widespread

involvement, and treatment options for this population are limited.

Skin irritation is a potential adverse effect of topical retinoids and topical vitamin D analogs.

Other local therapies that have been suggested for the treatment of acanthosis nigricans include topical urea,

salicylic acid, and laser therapy [16,85]. Improvement in axillary acanthosis nigricans in a patient treated with

long-pulsed alexandrite laser therapy has been reported [85]. Greater than 95 percent clearance of the lesions

was observed after five to seven treatments.

Topical retinoids Retinoids have keratinolytic effects on the skin, and topical tretinoin 0.1% gel applied

to localized areas of acanthosis nigricans for up to two weeks has been linked to improvement in

acanthosis nigricans in a few patients [79,80].

Combination therapy with tretinoin and other agents may also be effective. Once-daily application of

tretinoin 0.05% cream and twice-daily application of 12% ammonium lactate cream or lotion for a few

months was associated with improvement in acanthosis nigricans on the front of the neck in a series of

five patients [81]. Of note, improvement was not detected on the sides of the neck, which were treated with

either agent as monotherapy. In addition, a triple combination cream containing tretinoin 0.05%,

hydroquinone 4%, and fluocinolone acetonide 0.01% applied daily for one month was effective in a patient

with limited neck and face lesions [82].

Topical vitamin D analogs Topical vitamin D analogs are capable of reducing keratinocyte proliferation,

and have been associated with lesion improvement in several patients [67,83,84]. As an example,

calcipotriol (calcipotriene) 0.005% cream applied twice daily for three months led to improvement in

acanthosis nigricans in flexural areas in an obese man with bladder cancer [83]. Moreover, twice daily use

of calcipotriol ointment for four weeks by a man with hypogonadism-associated acanthosis nigricans was

associated with complete remission of the lesions [84].

Treatment with systemic retinoids such as isotretinoin and acitretin has been associated with moderate to

marked improvement in several patients with extensive acanthosis nigricans [67,70,86,87]. However, systemic

retinoids have a wide range of potential adverse effects, and relapse appears to be common upon tapering or

discontinuation of therapy [67,70]. Treatment with these agents is not indicated in most patients.

Case reports have documented beneficial effects of pharmacologic interventions in small numbers of patients

with malignancy-associated acanthosis nigricans [88,89]. A reduction in pruritus was noted in a lung cancer

patient with treated psoralen plus ultraviolet A (PUVA) phototherapy [88], and marked improvement in signs and

symptoms of the disorder was reported in a patient with both gastric and prostate cancer who was treated with

cyproheptadine [89]. One case of improvement with liraglutide a glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) analog has

been reported [90].

PROGNOSIS Acanthosis nigricans is a chronic disorder that persists in the absence of removal of the

underlying cause or successful skin-directed therapy. In isolation, the long-term persistence of acanthosis

nigricans usually has no physical adverse consequences.

However, patients with acanthosis nigricans associated with obesity or medical disorders are subject to

disease-specific sequelae. The prognosis for malignancy-associated acanthosis nigricans often is poor since

malignancy is frequently diagnosed at an advanced stage [91].

INDICATIONS FOR REFERRAL Referral to a dermatologist is indicated if the diagnosis of skin lesions is

uncertain. Evaluation by a clinician with expertise in the management of endocrine or metabolic disorders is

indicated if such disorders are detected.

SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Acanthosis nigricans is a common, benign disorder that typically presents with velvety, hyperpigmented

plaques on the skin. Mucosal involvement is an occasional feature. Individuals of any age may be affected.

(See 'Clinical manifestations' above and 'Epidemiology' above.)

A wide variety of endocrine, metabolic, genetic, and malignant disorders may contribute to the

development of acanthosis nigricans. An evaluation for the underlying cause should always be performed.

Obesity is the most common cause of this disorder. Acanthosis nigricans may also be induced by drugs.

(See 'Etiology' above and 'Diagnosis and patient evaluation' above.)

Insulin resistance likely plays a key role in many cases of acanthosis nigricans, including cases linked to

obesity, diabetes, and some genetic syndromes. (See 'Pathogenesis' above.)

Malignancy is a rare cause of acanthosis nigricans. In particular, the possibility of an occult malignancy

should be considered in adults with extensive or atypical presentations of acanthosis nigricans or new

onset acanthosis nigricans of unknown cause. (See 'Malignancy-associated acanthosis nigricans' above

and 'Diagnosis and patient evaluation' above and "Cutaneous manifestations of internal malignancy",

section on 'Acanthosis nigricans'.)

Treatment of the clinical manifestations of acanthosis nigricans is not required since the condition does

not induce physical harm. The primary indications for treatment of the skin lesions are cosmetic concerns

of the patient. (See 'Treatment' above and 'Diagnosis and patient evaluation' above.)

Data are limited on the treatments for acanthosis nigricans. If an underlying cause is present, treatment or

removal of the inciting cause should be attempted. Obesity-related, drug-induced, and malignancy-

associated acanthosis nigricans often respond to this form of therapy. The role of agents that improve

insulin sensitivity in patients with acanthosis nigricans related to insulin resistance remains uncertain.

(See 'Treatment of underlying disorders' above.)

For patients who desire accelerated improvement of acanthosis nigricans or in whom treatment of the

underlying disorder is not possible or satisfactory, we suggest a trial of topical tretinoin or a topical vitamin

D analog, such as calcipotriol (calcipotriene) (Grade 2C). Systemic retinoids may lead to clinical

improvement in patients with extensive or severe disease, but relapse is common after treatment

discontinuation. (See 'Skin-directed therapy' above.)

ACKNOWLEDGMENT The editors of UpToDate would like to acknowledge Kathryn Schwarzenberger, MD,

who contributed to earlier versions of this topic review.

Use of UpToDate is subject to the Subscription and License Agreement.

REFERENCES

1. Hud JA Jr, Cohen JB, Wagner JM, Cruz PD Jr. Prevalence and significance of acanthosis nigricans in an

adult obese population. Arch Dermatol 1992; 128:941.

2. Dassanayake AS, Kasturiratne A, Niriella MA, et al. Prevalence of Acanthosis Nigricans in an urban

population in Sri Lanka and its utility to detect metabolic syndrome. BMC Res Notes 2011; 4:25.

3. Chang Y, Woo HY, Sung E, et al. Prevalence of acanthosis nigricans in relation to anthropometric

measures: community-based cross-sectional study in Korean pre-adolescent school children. Pediatr Int

2008; 50:667.

4. Ogbera AO, Akinlade A, Ajose O, Awobusuyi J. Prevalence of acanthosis nigricans and its correlates in a

cross-section of Nigerians with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Trop Doct 2009; 39:235.

5. Rafalson L, Eysaman J, Quattrin T. Screening obese students for acanthosis nigricans and other diabetes

risk factors in the urban school-based health center. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2011; 50:747.

6. Litonjua P, Piero-Piloa A, Aviles-Santa L, Raskin P. Prevalence of acanthosis nigricans in newly-

diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Endocr Pract 2004; 10:101.

7. Nguyen TT, Keil MF, Russell DL, et al. Relation of acanthosis nigricans to hyperinsulinemia and insulin

sensitivity in overweight African American and white children. J Pediatr 2001; 138:474.

8. Stuart CA, Pate CJ, Peters EJ. Prevalence of acanthosis nigricans in an unselected population. Am J

Med 1989; 87:269.

9. Stuart CA, Driscoll MS, Lundquist KF, et al. Acanthosis nigricans. J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol 1998;

9:407.

10. Brickman WJ, Binns HJ, Jovanovic BD, et al. Acanthosis nigricans: a common finding in overweight

youth. Pediatr Dermatol 2007; 24:601.

11. Kong AS, Williams RL, Smith M, et al. Acanthosis nigricans and diabetes risk factors: prevalence in

young persons seen in southwestern US primary care practices. Ann Fam Med 2007; 5:202.

12. Rafalson L, Pham TH, Willi SM, et al. The association between acanthosis nigricans and dysglycemia in

an ethnically diverse group of eighth grade students. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013; 21:E328.

13. Kopping D, Nevarez H, Goto K, et al. A longitudinal study of overweight, elevated blood pressure, and

acanthosis nigricans among low-income middle school students. J Sch Nurs 2012; 28:214.

14. Stoddart ML, Blevins KS, Lee ET, et al. Association of acanthosis nigricans with hyperinsulinemia

compared with other selected risk factors for type 2 diabetes in Cherokee Indians: the Cherokee Diabetes

Study. Diabetes Care 2002; 25:1009.

15. Kong AS, Williams RL, Rhyne R, et al. Acanthosis Nigricans: high prevalence and association with

diabetes in a practice-based research network consortium--a PRImary care Multi-Ethnic network (PRIME

Net) study. J Am Board Fam Med 2010; 23:476.

16. Sinha S, Schwartz RA. Juvenile acanthosis nigricans. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007; 57:502.

17. Stuart CA, Gilkison CR, Smith MM, et al. Acanthosis nigricans as a risk factor for non-insulin dependent

diabetes mellitus. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1998; 37:73.

18. Otto DE, Wang X, Tijerina SL, et al. A comparison of blood pressure, body mass index, and acanthosis

nigricans in school-age children. J Sch Nurs 2010; 26:223.

19. Brickman WJ, Huang J, Silverman BL, Metzger BE. Acanthosis nigricans identifies youth at high risk for

metabolic abnormalities. J Pediatr 2010; 156:87.

20. Dunaif A, Graf M, Mandeli J, et al. Characterization of groups of hyperandrogenic women with acanthosis

nigricans, impaired glucose tolerance, and/or hyperinsulinemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1987; 65:499.

21. Flier JS, Eastman RC, Minaker KL, et al. Acanthosis nigricans in obese women with hyperandrogenism.

Characterization of an insulin-resistant state distinct from the type A and B syndromes. Diabetes 1985;

34:101.

22. Dong Z, Huang J, Huang L, et al. Associations of acanthosis nigricans with metabolic abnormalities in

polycystic ovary syndrome women with normal body mass index. J Dermatol 2013; 40:188.

23. Brown B, Noonan C, Bentley B, et al. Acanthosis nigricans among Northern Plains American Indian

children. J Sch Nurs 2010; 26:450.

24. Ice CL, Murphy E, Minor VE, Neal WA. Metabolic syndrome in fifth grade children with acanthosis

nigricans: results from the CARDIAC project. World J Pediatr 2009; 5:23.

25. Valery PC, Moloney A, Cotterill A, et al. Prevalence of obesity and metabolic syndrome in Indigenous

Australian youths. Obes Rev 2009; 10:255.

26. Jabbour SA. Cutaneous manifestations of endocrine disorders: a guide for dermatologists. Am J Clin

Dermatol 2003; 4:315.

27. Huang-Doran I, Savage DB. Congenital syndromes of severe insulin resistance. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev

2011; 8:190.

28. Berk DR, Spector EB, Bayliss SJ. Familial acanthosis nigricans due to K650T FGFR3 mutation. Arch

Dermatol 2007; 143:1153.

29. Torley D, Bellus GA, Munro CS. Genes, growth factors and acanthosis nigricans. Br J Dermatol 2002;

147:1096.

30. Muoz-Prez MA, Camacho F. Acanthosis nigricans: a new cutaneous sign in severe atopic dermatitis

and Down syndrome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2001; 15:325.

31. Morice-Picard F, Ezzedine K, Delrue MA, et al. Cutaneous manifestations in Costello and

cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome: report of 18 cases and literature review. Pediatr Dermatol 2013; 30:665.

32. Ahmad S, Mahmoudi H, Naeem M, Betz RC. Autosomal recessive isolated familial acanthosis nigricans

in a Pakistani family due to a homozygous mutation in the insulin receptor gene. Br J Dermatol 2013;

169:476.

33. Schwartz RA. Acanthosis nigricans. J Am Acad Dermatol 1994; 31:1.

34. Talsania N, Harwood CA, Piras D, Cerio R. Paraneoplastic Acanthosis Nigricans: The importance of

exhaustive and repeated malignancy screening. Dermatol Online J 2010; 16:8.

35. Amjad M, Shah AA. Malignant acanthosis nigricans: an early diagnostic clue. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak

2010; 20:127.

36. Rigel DS, Jacobs MI. Malignant acanthosis nigricans: a review. J Dermatol Surg Oncol 1980; 6:923.

37. Anderson SH, Hudson-Peacock M, Muller AF. Malignant acanthosis nigricans: potential role of

chemotherapy. Br J Dermatol 1999; 141:714.

38. Krawczyk M, Mykaa-Ciela J, Koodziej-Jaskua A. Acanthosis nigricans as a paraneoplastic syndrome.

Case reports and review of literature. Pol Arch Med Wewn 2009; 119:180.

39. Lee SS, Jung NJ, Im M, et al. Acral-type Malignant Acanthosis Nigricans Associated with Gastric

Adenocarcinoma. Ann Dermatol 2011; 23:S208.

40. Fleming MG, Simon SI. Cutaneous insulin reaction resembling acanthosis nigricans. Arch Dermatol 1986;

122:1054.

41. Skouby SO. Update on the metabolic effects of oral contraceptives. J Obstet Gynaecol (Lahore) 1986; 6

Suppl 2:S104.

42. Stals H, Vercammen C, Peeters C, Morren MA. Acanthosis nigricans caused by nicotinic acid: case

report and review of the literature. Dermatology 1994; 189:203.

43. Mellor-Pita S, Yebra-Bango M, Alfaro-Martnez J, Surez E. Acanthosis nigricans: a new manifestation of

insulin resistance in patients receiving treatment with protease inhibitors. Clin Infect Dis 2002; 34:716.

44. Lane SW, Manoharan S, Mollee PN. Palifermin-induced acanthosis nigricans. Intern Med J 2007; 37:417.

45. Lee M, Grassi M. Acanthosis nigricans in a patient treated with palifermin. Cutis 2010; 86:136.

46. Karadag A, Kavala M, Demir F, et al. A case of hyperpigmentation and acanthosis nigricans by

testosterone injections. Hum Exp Toxicol 2014.

47. Manu P, Al-Dhaher Z, Dargani N, Correll CU. Acanthosis Nigricans During Treatment With Aripiprazole.

Am J Ther 2012.

48. Hida Y, Kubo Y, Nishio Y, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans with enhanced expression of fibroblast

growth factor receptor 3. Acta Derm Venereol 2009; 89:435.

49. Haase I, Hunzelmann N. Activation of epidermal growth factor receptor/ERK signaling correlates with

suppressed differentiation in malignant acanthosis nigricans. J Invest Dermatol 2002; 118:891.

50. Koyama S, Ikeda K, Sato M, et al. Transforming growth factor-alpha (TGF alpha)-producing gastric

carcinoma with acanthosis nigricans: an endocrine effect of TGF alpha in the pathogenesis of cutaneous

paraneoplastic syndrome and epithelial hyperplasia of the esophagus. J Gastroenterol 1997; 32:71.

51. Jeong JS, Lee JY, Yoon TY. Unilateral nevoid acanthosis nigricans with a submammary location. Ann

Dermatol 2011; 23:95.

52. Krishnaram AS. Unilateral nevoid acanthosis nigricans and neurofibromatosis 1: an unusual association.

Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2010; 76:715.

53. de Waal AC, van Rossum MM, Bovenschen HJ. Extensive segmental acanthosis nigricans form of

epidermal nevus. Dermatol Online J 2010; 16:7.

54. Ersoy-Evans S, Sahin S, Mancini AJ, et al. The acanthosis nigricans form of epidermal nevus. J Am Acad

Dermatol 2006; 55:696.

55. Schwartz RA. Acral acanthotic anomaly (AAA). J Am Acad Dermatol 1981; 5:345.

56. Schwartz RA. Acral acanthosis nigricans (acral acanthotic anomaly). J Am Acad Dermatol 2007; 56:349.

57. Brantsch KD, Moehrle M. Acanthosis nigricans in a patient with sarcoma of unknown origin. J Am Acad

Dermatol 2010; 62:527.

58. Thomas M, Radhakrishnan S, Sunny B, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans with occult primary. Indian J

Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2002; 68:371.

59. Pentenero M, Carrozzo M, Pagano M, Gandolfo S. Oral acanthosis nigricans, tripe palms and sign of

leser-trlat in a patient with gastric adenocarcinoma. Int J Dermatol 2004; 43:530.

60. Weedon D. Miscellaneous conditions. In: Weedon's Skin Pathology, 3rd ed, Elsevier Limited, 2010.

p.501.

61. Hall JM, Moreland A, Cox GJ, Wade TR. Oral acanthosis nigricans: report of a case and comparison of

oral and cutaneous pathology. Am J Dermatopathol 1988; 10:68.

62. Higgins SP, Freemark M, Prose NS. Acanthosis nigricans: a practical approach to evaluation and

management. Dermatol Online J 2008; 14:2.

63. Higgins HW, Jenkins J, Horn TD, Kroumpouzos G. Pregnancy-associated hyperkeratosis of the nipple: a

report of 25 cases. JAMA Dermatol 2013; 149:722.

64. Romo A, Benavides S. Treatment options in insulin resistance obesity-related acanthosis nigricans. Ann

Pharmacother 2008; 42:1090.

65. Kuroki R, Sadamoto Y, Imamura M, et al. Acanthosis nigricans with severe obesity, insulin resistance

and hypothyroidism: improvement by diet control. Dermatology 1999; 198:164.

66. Pasquali R, Antenucci D, Casimirri F, et al. Clinical and hormonal characteristics of obese amenorrheic

hyperandrogenic women before and after weight loss. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1989; 68:173.

67. Hermanns-L T, Hermanns JF, Pirard GE. Juvenile acanthosis nigricans and insulin resistance. Pediatr

Dermatol 2002; 19:12.

68. Bellot-Rojas P, Posadas-Sanchez R, Caracas-Portilla N, et al. Comparison of metformin versus

rosiglitazone in patients with Acanthosis nigricans: a pilot study. J Drugs Dermatol 2006; 5:884.

69. Tankova T, Koev D, Dakovska L, Kirilov G. Therapeutic approach in insulin resistance with acanthosis

nigricans. Int J Clin Pract 2002; 56:578.

70. Walling HW, Messingham M, Myers LM, et al. Improvement of acanthosis nigricans on isotretinoin and

metformin. J Drugs Dermatol 2003; 2:677.

71. Wasniewska M, Arrigo T, Crisafulli G, et al. Recovery of acanthosis nigricans under prolonged metformin

treatment in an adolescent with normal weight. J Endocrinol Invest 2009; 32:939.

72. Lee PJ, Cranston I, Amiel SA, et al. Effect of metformin on glucose disposal and hyperinsulinaemia in a

14-year-old boy with acanthosis nigricans. Horm Res 1997; 48:88.

73. Ellis DL, Kafka SP, Chow JC, et al. Melanoma, growth factors, acanthosis nigricans, the sign of Leser-

Trlat, and multiple acrochordons. A possible role for alpha-transforming growth factor in cutaneous

paraneoplastic syndromes. N Engl J Med 1987; 317:1582.

74. Vassilopoulou-Sellin R, Cangir A, Samaan NA. Acanthosis nigricans and severe insulin resistance in an

adolescent girl with thyroid cancer: clinical response to antineoplastic therapy. Am J Clin Oncol 1992;

15:273.

75. Yeh JS, Munn SE, Plunkett TA, et al. Coexistence of acanthosis nigricans and the sign of Leser-Trlat in

a patient with gastric adenocarcinoma: a case report and literature review. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000;

42:357.

76. Kebria MM, Belinson J, Kim R, Mekhail TM. Malignant acanthosis nigricans, tripe palms and the sign of

Leser-Tre'lat, a hint to the diagnosis of early stage ovarian cancer: a case report and review of the

literature. Gynecol Oncol 2006; 101:353.

77. Lunetta M, Di Mauro M, Le Moli R, Burrafato S. Long-term octreotide treatment reduced hyperinsulinemia,

excess body weight and skin lesions in severe obesity with acanthosis nigricans. J Endocrinol Invest

1996; 19:699.

78. Sherertz EF. Improved acanthosis nigricans with lipodystrophic diabetes during dietary fish oil

supplementation. Arch Dermatol 1988; 124:1094.

79. Darmstadt GL, Yokel BK, Horn TD. Treatment of acanthosis nigricans with tretinoin. Arch Dermatol 1991;

127:1139.

80. Berger BJ, Gross PR. Another use for tretinoin--pseudoacanthosis nigricans. Arch Dermatol 1973;

108:133.

81. Blobstein SH. Topical therapy with tretinoin and ammonium lactate for acanthosis nigricans associated

with obesity. Cutis 2003; 71:33.

82. Adigun CG, Pandya AG. Improvement of idiopathic acanthosis nigricans with a triple combination

depigmenting cream. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2009; 23:486.

83. Bhm M, Luger TA, Metze D. Treatment of mixed-type acanthosis nigricans with topical calcipotriol. Br J

Dermatol 1998; 139:932.

84. Gregoriou S, Anyfandakis V, Kontoleon P, et al. Acanthosis nigricans associated with primary

hypogonadism: successful treatment with topical calcipotriol. J Dermatolog Treat 2008; 19:373.

85. Rosenbach A, Ram R. Treatment of Acanthosis nigricans of the axillae using a long-pulsed (5-msec)

alexandrite laser. Dermatol Surg 2004; 30:1158.

86. Swineford SL, Drucker CR. Palliative treatment of paraneoplastic acanthosis nigricans and oral florid

papillomatosis with retinoids. J Drugs Dermatol 2010; 9:1151.

87. Katz RA. Treatment of acanthosis nigricans with oral isotretinoin. Arch Dermatol 1980; 116:110.

88. Bonnekoh B, Thiele B, Merk H, Mahrle G. [Systemic photochemotherapy (PUVA) in acanthosis nigricans

maligna: regression of keratosis, hyperpigmentation and pruritus]. Z Hautkr 1989; 64:1059.

89. Greenwood R, Tring FC. Treatment of malignant acanthosis nigricans with cyproheptadine. Br J Dermatol

1982; 106:697.

90. Malisiewicz B, Boehncke S, Lang V, et al. Epidermal Insulin Resistance as a Therapeutic Target in

Acanthosis nigricans? Acta Derm Venereol 2014.

91. CURTH HO, HILBERG AW, MACHACEK GF. The site and histology of the cancer associated with

malignant acanthosis nigricans. Cancer 1962; 15:364.

Topic 13754 Version 2.0

GRAPHICS

Acanthosis nigricans

A velvety, slightly verrucous plaque is present on the neck.

Graphic 72964 Version 1.0

Acanthosis nigricans

A mildly hyperpigmented, velvety plaque with small papillary projections is

present on the neck.

Graphic 52948 Version 1.0

Acanthosis nigricans

Hyperpigmented velvety plaques are present in the axilla.

Reproduced with permission from: www.visualdx.com. Copyright Logical

Images, Inc.

Graphic 66384 Version 3.0

Acanthosis nigricans

Close view of acanthosis nigricans on the posterior neck.

Hyperpigmented velvety plaques are present.

Reproduced with permission from: www.visualdx.com. Copyright Logical

Images, Inc.

Graphic 81693 Version 3.0

Acanthosis nigricans

A velvety hyperpigmented plaque with associated acrochordae is

present in the axilla.

Graphic 61666 Version 1.0

Acanthosis nigricans

Hyperpigmented, velvety plaques are present in the groin.

Reproduced with permission from: www.visualdx.com. Copyright Logical Images, Inc.

Graphic 76234 Version 3.0

Acanthosis nigricans

A hyperpigmented, velvety plaque is present on the umbilicus.

Reproduced with permission from: www.visualdx.com. Copyright Logical Images, Inc.

Graphic 50592 Version 4.0

Acanthosis nigricans

Verrucous changes are present on the lips.

Reproduced with permission from: www.visualdx.com. Copyright Logical Images, Inc.

Graphic 63422 Version 3.0

Acanthosis nigricans

A hyperpigmented plaque with a verrucous surface is present on the nipple.

Reproduced with permission from: www.visualdx.com. Copyright Logical Images, Inc.

Graphic 52056 Version 3.0

Acral acanthosis nigricans (acral acanthotic anomaly)

Hyperpigmented thin plaques are present on the dorsal hand. The lesions are

primarily located over the joints.

Reproduced with permission from: www.visualdx.com. Copyright Logical Images, Inc.

Graphic 70582 Version 3.0

Tripe palm

The palmar ridges show maximal accentuation, thus resembling the

mucosa of the stomach of a ruminant (tripe palm).

Reproduced with permission from: Fitzpatrick, TB, Johnson, RA, Wolff, K,

Suurmond, D. Color Atlas of Clinical Dermatology: Common and Serious

Diseases. McGraw Hill, New York 2001. p.151. Copyright 2001 McGraw Hill

Companies, Inc.

Graphic 61955 Version 3.0

Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis

Reticulated, hyperpigmented patches and thin plaques with fine scale

are present on the upper back.

Reproduced with permission from: www.visualdx.com. Copyright Logical

Images, Inc.

Graphic 67566 Version 3.0

Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis

Reticulated, hyperpigmented patches and thin plaques with mild scale

are present on the chest and inframammary areas.

Reproduced with permission from: www.visualdx.com. Copyright Logical

Images, Inc.

Graphic 76296 Version 3.0

Granular parakeratosis

Hyperkeratotic red-brown papules are present in the axilla.

Graphic 73591 Version 1.0

Epidermal nevus

A hyperpigmented, verrucous, linear plaque is present on the neck.

Reproduced with permission from: www.visualdx.com. Copyright Logical Images, Inc.

Graphic 64855 Version 3.0

Reticulated pigmented anomaly of the flexures (Dowling-

Degos disease)

A reticulated, hyperpigmented plaque is present perianally.

Reproduced with permission from: www.visualdx.com. Copyright Logical Images, Inc.

Graphic 77681 Version 3.0

Hailey-Hailey disease

Typical axillary plaque of Hailey-Hailey disease, showing superficial

erosions and crusts.

Graphic 61689 Version 2.0

Vulvar Hailey-Hailey disease

A large erythematous plaque with multiple superficial erosions involving

the vulvar and groin area in a patient with Hailey Hailey disease.

Courtesy of Lynne J Margesson, MD.

Graphic 80862 Version 3.0

Perianal Hailey-Hailey disease

Large erythematous and crusty perianal plaque in a patient with Hailey

Hailey disease.

Graphic 74552 Version 3.0

Di scl osures: Inbal Braunstein, MD Nothing to disclose. Jeffrey Callen, MD, FACP, FAAD Consultant/Advisory Boards: Xoma;

Amgen [psoriasis (etanercept)]; Lilly; Steif el, a GSK company; Auxilium. Equity Ownership/Stock Options: Celgene; Pf izer; 3M;

Johnson & Johnson; Merck; Abbott; Abbvie; Proctor & Gamble. Equity Ownership/Stock Options (spouse): 3M; Abbott; Abbvie;

Amgen; Johnson & Johnson; Proctor & Gamble. Abena O Ofori, MD Employee of UpToDate, Inc.

Contributor disclosures are reviewed f or conf licts of interest by the editorial group. When f ound, these are addressed by vetting

through a multi-level review process, and through requirements f or ref erences to be provided to support the content. Appropriately

ref erenced content is required of all authors and must conf orm to UpToDate standards of evidence.

Conflict of interest policy

Disclosures

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Gastric CancerDocument25 pagesGastric CancerAndreea SubcinschiPas encore d'évaluation

- Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, and Clinical Manifestations of Celiac Disease in Children - UpToDateDocument26 pagesEpidemiology, Pathogenesis, and Clinical Manifestations of Celiac Disease in Children - UpToDatejandagashvili2007Pas encore d'évaluation

- Acanthosis Nigricans - emedICINE.2012.2013.FCPSDocument16 pagesAcanthosis Nigricans - emedICINE.2012.2013.FCPSAbdul QuyyumPas encore d'évaluation

- Akne Obese Lipid 2009Document5 pagesAkne Obese Lipid 2009Henyta TsuPas encore d'évaluation

- Diabetes Hypertension Obesity: PathophysiologyDocument3 pagesDiabetes Hypertension Obesity: PathophysiologyDevy AndikaPas encore d'évaluation

- SJ Ijo 0800495Document23 pagesSJ Ijo 0800495Mohammad shaabanPas encore d'évaluation

- The Metabolic Syndrome in Polycystic Ovary SyndromeDocument21 pagesThe Metabolic Syndrome in Polycystic Ovary SyndromeHAVIZ YUADPas encore d'évaluation

- Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus - Prevalence and Risk Factors - UpToDateDocument36 pagesType 2 Diabetes Mellitus - Prevalence and Risk Factors - UpToDateEver LuizagaPas encore d'évaluation

- Approach To The Patient With Unintentional Weight LossDocument11 pagesApproach To The Patient With Unintentional Weight LossPetru-Emanuel DascalitaPas encore d'évaluation

- Sam CD Diabetes MellitusDocument26 pagesSam CD Diabetes MellitusDr. Muha. Hasan Mahbub-Ur-RahmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Comorbidities and Complications of Obesity in Children and Adolescents - UpToDateDocument35 pagesComorbidities and Complications of Obesity in Children and Adolescents - UpToDatemarina alvesPas encore d'évaluation

- Preamble: Podcast Interview: - Also Available On ItunesDocument18 pagesPreamble: Podcast Interview: - Also Available On ItuneswawanpecelPas encore d'évaluation

- Insulin OmaDocument17 pagesInsulin OmaRezky Faried HidayatullahPas encore d'évaluation

- Ovario Poliquistico Articulo 2011Document16 pagesOvario Poliquistico Articulo 2011nikonhpPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 s2.0 S0026049517302743 MainDocument11 pages1 s2.0 S0026049517302743 MainTeodora OnofreiPas encore d'évaluation

- Epidemiology and Pathophysiology of Colonic Diverticular DiseaseDocument8 pagesEpidemiology and Pathophysiology of Colonic Diverticular DiseaseAnonymous Hz5w55Pas encore d'évaluation

- Fatty Pancreas Clinical ImplicationsDocument6 pagesFatty Pancreas Clinical ImplicationsEngin ALTINTASPas encore d'évaluation

- Changing Trends in Peptic Ulcer Prevalence in A Tertiary Care Setting in The PhilippinesDocument3 pagesChanging Trends in Peptic Ulcer Prevalence in A Tertiary Care Setting in The PhilippinesRumelle ReyesPas encore d'évaluation

- Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Science in MedicineDocument7 pagesGestational Diabetes Mellitus: Science in MedicineNatalia_p_mPas encore d'évaluation

- Hígado Graso No AlcohólicoDocument16 pagesHígado Graso No AlcohólicoAntonio Martinez GarciaPas encore d'évaluation

- Tugas Bahasa IndonesiaDocument26 pagesTugas Bahasa IndonesiaAtha KudmasaPas encore d'évaluation

- 4 Metabolic Complications Pedersen2013 - Alan OsorioDocument15 pages4 Metabolic Complications Pedersen2013 - Alan Osoriomtz.c.erikaPas encore d'évaluation

- Periodontal Infection and Glycemic Control in Diabetes: Current EvidenceDocument5 pagesPeriodontal Infection and Glycemic Control in Diabetes: Current EvidencegarciamanuelPas encore d'évaluation

- POSITION STATEMENTPreDMsop TRTRDocument12 pagesPOSITION STATEMENTPreDMsop TRTRTony CoaPas encore d'évaluation

- Obesity - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDocument8 pagesObesity - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfWidad SalsabilaPas encore d'évaluation

- j.1365 2796.2006.01752.x20160829 29101 n3bfks With Cover Page v2Document12 pagesj.1365 2796.2006.01752.x20160829 29101 n3bfks With Cover Page v2herondalePas encore d'évaluation

- Reviews: Hyperinsulinaemia in CancerDocument16 pagesReviews: Hyperinsulinaemia in CancerThiago SartiPas encore d'évaluation

- Eating Disorders, Bulimia, AnorexiaDocument48 pagesEating Disorders, Bulimia, AnorexiaMariaPas encore d'évaluation

- Colonic Diverticulosis and Diverticular Disease Epidemiology, RiskDocument20 pagesColonic Diverticulosis and Diverticular Disease Epidemiology, RiskmohammedPas encore d'évaluation

- Pe Project Obesity: Name: Manas Kadam Class: XII A Commerce Roll No - 87Document32 pagesPe Project Obesity: Name: Manas Kadam Class: XII A Commerce Roll No - 87sahilPas encore d'évaluation

- Eating Pathology in Adolescents With Celiac Disease PDFDocument8 pagesEating Pathology in Adolescents With Celiac Disease PDFFrancisco ChristianPas encore d'évaluation

- NASH in ChildrenDocument10 pagesNASH in ChildrendrtpkPas encore d'évaluation

- Nutrients 05 02019Document9 pagesNutrients 05 02019FITYOURBODYPas encore d'évaluation

- Effect of Diet On Type 2 Diabetes MellitusDocument14 pagesEffect of Diet On Type 2 Diabetes MellitusPriya bhattiPas encore d'évaluation

- 2015 Sup 11 FullDocument5 pages2015 Sup 11 FullsebastianPas encore d'évaluation

- Obesityasadisease: Jagriti Upadhyay,, Olivia Farr,, Nikolaos Perakakis,, Wael Ghaly,, Christos MantzorosDocument21 pagesObesityasadisease: Jagriti Upadhyay,, Olivia Farr,, Nikolaos Perakakis,, Wael Ghaly,, Christos MantzorosAlejandra RamirezPas encore d'évaluation

- Definitions, Epidemiology, and Risk Factors For Inflammatory Bowel Disease - UpToDateDocument25 pagesDefinitions, Epidemiology, and Risk Factors For Inflammatory Bowel Disease - UpToDateTurma A 2019.1 Med-FCMPas encore d'évaluation

- Pe Project: Name: Aakanksh Biswas Class: XII A Commerce Roll No - 27Document28 pagesPe Project: Name: Aakanksh Biswas Class: XII A Commerce Roll No - 27sahilPas encore d'évaluation

- Summary of Andrew J. Wakefield's Waging War On The Autistic ChildD'EverandSummary of Andrew J. Wakefield's Waging War On The Autistic ChildPas encore d'évaluation

- Anorexia Nervosa in Adults and Adolescents - The Refeeding Syndrome - UpToDateDocument11 pagesAnorexia Nervosa in Adults and Adolescents - The Refeeding Syndrome - UpToDateAlejandra GarcíaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Relation of Overweight To Cardiovascular Risk Factors Among Children and Adolescents: The Bogalusa Heart StudyDocument10 pagesThe Relation of Overweight To Cardiovascular Risk Factors Among Children and Adolescents: The Bogalusa Heart StudyaocuPas encore d'évaluation

- Ulcerative Colitis in ChildrenDocument5 pagesUlcerative Colitis in ChildrentheservantPas encore d'évaluation

- البحثDocument43 pagesالبحثحسين علي ذيبان عليPas encore d'évaluation

- Diagnosis of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome in Adults - UpToDateDocument27 pagesDiagnosis of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome in Adults - UpToDatepeishanwang90Pas encore d'évaluation

- Pediatric Obesity and Gallstone Disease.18Document6 pagesPediatric Obesity and Gallstone Disease.18Merari Lugo OcañaPas encore d'évaluation

- Ovario Poliquístico/Polycystic Ovary SyndromeDocument14 pagesOvario Poliquístico/Polycystic Ovary SyndromeJosé María Lauricella100% (1)

- Dyslipidemia Journal ArticleDocument10 pagesDyslipidemia Journal ArticleJeanPas encore d'évaluation

- 2004 Metabolic Risk During Antipsychotic TreatmentDocument11 pages2004 Metabolic Risk During Antipsychotic TreatmentDiego HormacheaPas encore d'évaluation

- Gut-2006-Van Heel-1037-46Document11 pagesGut-2006-Van Heel-1037-46Codruta StanPas encore d'évaluation

- Type1 DiabetesDocument7 pagesType1 DiabetesbettyborblePas encore d'évaluation

- Colonic Diverticulosis and Diverticular Disease - Epidemiology, Risk Factors, andDocument25 pagesColonic Diverticulosis and Diverticular Disease - Epidemiology, Risk Factors, andBryan JimenezPas encore d'évaluation

- Waist and Hip Circumferences and Waist-Hip Ratio I-2Document1 pageWaist and Hip Circumferences and Waist-Hip Ratio I-2VenkatPas encore d'évaluation

- Metabolic Syndrome and StrokeDocument5 pagesMetabolic Syndrome and StrokeEmir SaricPas encore d'évaluation

- Anorexia Nervosa in Adults and Adolescents - The Refeeding Syndrome - UpToDateDocument10 pagesAnorexia Nervosa in Adults and Adolescents - The Refeeding Syndrome - UpToDatethelesphol pascalPas encore d'évaluation

- Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & MetabolismDocument11 pagesBest Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & MetabolismM Slamet RiyantoPas encore d'évaluation

- Eating Disorders - Overview of Epidemiology, Clinical Features, and Diagnosis - UpToDateDocument39 pagesEating Disorders - Overview of Epidemiology, Clinical Features, and Diagnosis - UpToDateDylanPas encore d'évaluation

- Diabetes Treatment Literature ReviewDocument7 pagesDiabetes Treatment Literature Reviewafmzatvuipwdal100% (1)

- Review of LiteratureDocument3 pagesReview of LiteraturepremPas encore d'évaluation

- ReflubDocument20 pagesReflubcantantederockPas encore d'évaluation

- Clinical Manifestations and Complications of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Children and AdolescentsDocument926 pagesClinical Manifestations and Complications of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Children and AdolescentsFlorin Calin LungPas encore d'évaluation

- Impact of Polycystic Ovary, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity on Women Health: Volume 8: Frontiers in Gynecological EndocrinologyD'EverandImpact of Polycystic Ovary, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity on Women Health: Volume 8: Frontiers in Gynecological EndocrinologyPas encore d'évaluation

- Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring in Children - UpToDateDocument17 pagesAmbulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring in Children - UpToDateZeliha TürksavulPas encore d'évaluation

- An Approach To The Patient With Drug Allergy - UpToDateDocument26 pagesAn Approach To The Patient With Drug Allergy - UpToDateZeliha TürksavulPas encore d'évaluation

- Allergic Rhinitis Clinical Manifestations Epidemiology and DDocument23 pagesAllergic Rhinitis Clinical Manifestations Epidemiology and DZeliha TürksavulPas encore d'évaluation

- Allergic Reactions To Vaccines - UpToDateDocument23 pagesAllergic Reactions To Vaccines - UpToDateZeliha TürksavulPas encore d'évaluation

- Allergic Reactions To Vaccines - UpToDateDocument23 pagesAllergic Reactions To Vaccines - UpToDateZeliha TürksavulPas encore d'évaluation

- Acute Liver Failure in Children Management - UpToDateDocument20 pagesAcute Liver Failure in Children Management - UpToDateZeliha TürksavulPas encore d'évaluation

- FINAL Standalone Pediatric Obesity GuidelineDocument44 pagesFINAL Standalone Pediatric Obesity GuidelineZeliha TürksavulPas encore d'évaluation

- Acquired Torticollis in Children - UpToDateDocument21 pagesAcquired Torticollis in Children - UpToDateZeliha TürksavulPas encore d'évaluation

- Acquired Inhibitors of Coagulation - UpToDateDocument23 pagesAcquired Inhibitors of Coagulation - UpToDateZeliha TürksavulPas encore d'évaluation

- Efficacy and Safety of Prophylactic Vaccines Against Cervical HPV Infection andDocument31 pagesEfficacy and Safety of Prophylactic Vaccines Against Cervical HPV Infection andZeliha TürksavulPas encore d'évaluation

- Surgery Mcqs Along With KeyDocument8 pagesSurgery Mcqs Along With KeyFaizan Khan100% (3)

- KD 3.4 Reading Practice - Analytical ExpositionDocument6 pagesKD 3.4 Reading Practice - Analytical ExpositionManusiaa HiduppPas encore d'évaluation

- Uses of X-Rays in Medical FieldDocument6 pagesUses of X-Rays in Medical FieldShwe Pwint Pyae SonePas encore d'évaluation

- IMMUNOCAL Projected To Become #1Document2 pagesIMMUNOCAL Projected To Become #1m_wfulton3815Pas encore d'évaluation

- Zoladex 3.6mg Implant - Summary of Product Characteristics (SMPC) - Print Friendly - (Emc)Document8 pagesZoladex 3.6mg Implant - Summary of Product Characteristics (SMPC) - Print Friendly - (Emc)KunalPas encore d'évaluation

- Gout Diet Foods To Avoid and Low-Purine Foods To Eat InsteadDocument1 pageGout Diet Foods To Avoid and Low-Purine Foods To Eat InsteadDesiree Jolly Dela CruzPas encore d'évaluation

- OB-GYN - Standardized Patient PrepDocument6 pagesOB-GYN - Standardized Patient Prepskeebs23Pas encore d'évaluation

- CHEMOTHERAPYDocument28 pagesCHEMOTHERAPYDwi CahyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Fda Approved Contrast AgentsDocument55 pagesFda Approved Contrast AgentsPoojaSolankiPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Study For Colorectal CancerDocument23 pagesCase Study For Colorectal CancerAnjanette ViloriaPas encore d'évaluation

- For Oral CancerDocument88 pagesFor Oral Cancercjane.correos25Pas encore d'évaluation

- Brain Tumors (Benign and Malignant) - Symptoms, Causes, TreatmentDocument4 pagesBrain Tumors (Benign and Malignant) - Symptoms, Causes, TreatmentThuvija DarshiniPas encore d'évaluation

- Ferrets Oncology-MainDocument26 pagesFerrets Oncology-MainJOAQUINALONZOPEREIRAPas encore d'évaluation

- Qualitative Studies On Working Students 2Document75 pagesQualitative Studies On Working Students 2Angelica MatullanoPas encore d'évaluation

- LIC - Cancer Cover - Brochure - 9 Inch X 8 Inch - Eng - Single PagesDocument10 pagesLIC - Cancer Cover - Brochure - 9 Inch X 8 Inch - Eng - Single PagesKumar KalyanPas encore d'évaluation

- What Is Radioactive PollutionDocument4 pagesWhat Is Radioactive PollutionJoy MitraPas encore d'évaluation

- Group 10Document12 pagesGroup 10Esdras DountioPas encore d'évaluation

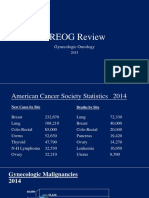

- 2015 Oncology CREOG Review PDFDocument76 pages2015 Oncology CREOG Review PDFRima HajjarPas encore d'évaluation

- AstrositomaDocument29 pagesAstrositomaFitria NurulfathPas encore d'évaluation

- AIChE Journal Vol (1) - 51 No. 12 December 2005Document229 pagesAIChE Journal Vol (1) - 51 No. 12 December 2005naraNJORPas encore d'évaluation

- Clinical Oncology PaperDocument20 pagesClinical Oncology Paperapi-633111194Pas encore d'évaluation

- 4 Interview Transcripts From The Anti Cancer Revolution 2Document72 pages4 Interview Transcripts From The Anti Cancer Revolution 2Pierre Le GrandePas encore d'évaluation

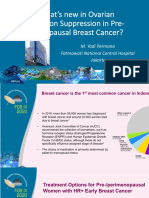

- 2.3.a DR Yadi Permana Whats New in Ovarian Function Suppression in Pre-MenopausalDocument36 pages2.3.a DR Yadi Permana Whats New in Ovarian Function Suppression in Pre-Menopausaltepat rshsPas encore d'évaluation

- InformaciónDocument14 pagesInformaciónAlondraPas encore d'évaluation

- Thời gian làm bài: 60 phút: Kỳ Thi Học Kỳ I Năm Học 2017-2018Document40 pagesThời gian làm bài: 60 phút: Kỳ Thi Học Kỳ I Năm Học 2017-2018Quynh TrangPas encore d'évaluation

- The Two Faces of Cell Division: Mitosis MeiosisDocument5 pagesThe Two Faces of Cell Division: Mitosis MeiosisJamie MakrisPas encore d'évaluation

- BiopsiesDocument13 pagesBiopsiesSubbu ManiPas encore d'évaluation

- NCM116 - Metabolic - Endocrine DisordersDocument24 pagesNCM116 - Metabolic - Endocrine DisordersDan Hizon100% (1)

- Mammo MidtermsDocument23 pagesMammo MidtermsCherie lou PizaPas encore d'évaluation