Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

DLSU AKI - Local Cooperation and Upgrading in Response To Globalization

Transféré par

Benedict RazonDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

DLSU AKI - Local Cooperation and Upgrading in Response To Globalization

Transféré par

Benedict RazonDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

LOCALCOOPERATIONANDUPGRADINGINRESPONSETO

GLOBALIZATION:THECASEOFCEBUSFURNITUREINDUSTRY

VictoriaZosa

I.INTRODUCTION

The Cebu furniture industry is not a newcomer to globalization, with an international

rattanmarketpresencedatingbacktothe1950s.Partneringwithglobalbuyers,Cebubecamea

dominantrattanfurnitureexporter untilthe1980s,afterwhichitsshareintheglobalfurniture

market steadily declined to a negligible level as exports from Malaysia, China, and Vietnam

displaced Cebus. The furniture industry, however, is still a major contributor to the Cebuano

economy,remainingoneofthetopexportearnersoftheprovince.

Theindustrysresponsetoglobalizationoverthedecadesisaninterestingcasestudyof

an established industry suddenly being put in transition. With the entry of new, lowcost

producers in the global market since the 1980s, the pressure for product upgrading mounted.

Thesenewentrantspossessmultipleadvantagessuchaslowrawmaterialcost,lowlaborcost,

governmentsupportandaccesstotechnology.Theliteratureoncompetitivenesssuggeststhat

Cebu has to take the high road of competitiveness by upgradingmaking better products,

producing them more efficiently, and moving into more skilled activities. In this regard,

cooperationamongindustrystakeholdersandglobalbuyersplaysanimportantroleinproduct

upgrading(Loebis&Schmitz,2005).

Inbroadstrokes,thisstudydiscussesthedepletionofrattanresources,Cebufurnitures

coping mechanisms and the shift toward product and process upgrading. The work has the

followingobjectives:(i)examinetheroleoflocalcooperationinproductupgradingwithrespect

to raw materials procurement, interfirm relations, knowledge diffusion, entrepreneurship,

gender and income, and business associations; (ii) determine the role of global buyers in

product and process upgrading; (iii) verify the implications of global market trends on the

Philippinefurnitureindustry.

The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 traces the evolution of the Cebu furniture

industry, defines the study objectives, and presents the data and study approach. Section 3

looks into the industry today, focusing on: (a) the use of common raw materials by

complementary industries, (b) interfirm cooperation in the cluster, (c) the role of skilled

workers in knowledge diffusion, (d) the role of local entrepreneurs, (e) the contribution of

womenintheindustry,and(f)theroleofbusinessassociationsandstrategicalliances,suchas

those with local government units. Section 4 tackles the global buyers tasks in product

upgrading and process upgrading. Section 5 outlines the Philippine experience in the global

furniture industry, and Section 6 summarizes the findings and charts future directions for

competitivenessandupgradinginthefurnitureclustersandvaluechain.

II.OVERVIEWOFTHEFURNITUREINDUSTRYANDMETHODOLOGY

A.EvolutionoftheCebuFurnitureIndustry

The evolution of this Filipino industrial sector is cast within the global value chain

framework. Figure 1 shows the furniture value chain (Kaplinsky & Morris, 2003). The cycle

proceedsasfollows:Themajorinputstotheforestrysectorareseeds,chemicals,machineries,

andwaterandextensionservices.Cutlogsarebroughttothesawmill,whichareprocessedto

sawn timber using chemicals, machinery, and logistics and quality advise. Manufacturers

transform the wood products to export furniture, with inputs of design, machinery and

chemicals and paints, adhesives, upholstery, etc. Furniture products are then sold to both

domesticandforeignbuyers.InthecaseofCebu,however,some90%ofthefurnitureproducts

areexported(OrganizationalPerformanceAssociates,Inc.,2003).Thelargefurnitureexporters

havedirectaccesstoforeignmarketsthroughthewholesalers(distributors),manufacturers,and

retailers. Small furniture exporters, for their part, turn to buying agents. Furniture exports

eventually reach consumers who, after a period of time, either recycle or dispose the furniture

asjunk.

TherootsoftheCebufurnitureclustercanbetracedtotwohistoricalcircumstances:the

MehitabelMcGuiresupplierbuyerpartnershipin1948whichintroducedCeburattanproducts

totheglobalmarket,andthe1981entryofMaitlandSmithLimitedtoCebu,exposingthelocal

craftsmenandindustryplayerstoglobalfurnituredesignandproductinnovation.Theindustry

hasexperiencedmajorsupplyside(e.g.therattanshortagestartinginthe1970s,theonandoff

log ban, exodus of skilled craftsmen to competitor countries) and demand side shocks (global

entry of lowcost newcomers such as Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, China and Vietnam from

the1980sonwards,andthepopularityofIKEAassemblytypefurniture).

Machinery

Water

Seeds

Chemicals

Design

Machinery

Extension

services

Machinery

Logistics,quality

advice

Paint,adhesives,

upholsteryetc.

Forestry

Sawmills

Furnituremanufacturers

Buyers

Domesticwholesale

Foreignretail Domesticretail

Recycling

Consumers

Source:KaplinskyandMorris(2003)

Figure 1: The Furniture Value Chain

Foreign wholesale

Cebusrattanfurniturewentglobalin1948,whenMehitabel,alocalbackyardfurniture

shop,partneredwithMcGuireFurnitureCompany,aUSbuyer.Dissatisfiedwiththequalityof

Cebu rattan furniture, McGuire initiated a breakthrough in rattan production by combining

rattanwithcowhidetoaddressthebulkstrengthproblem(processupgrading)andhiringaUS

designer(productupgrading).TheMehitabelMcGuirepartnershipbecamesuchasuccessthat

McGuire furniture was marketed in 21 US cities, Europe, and Japan. To cope with increasing

demand,MehitabelsubcontractedsomejobstoRattanArtsandRattanPacifica(Jurado,1997).

The furniture association (Chamber of Furniture Industry in the PhilippinesCebu

Chapter,orCFIPCebu)wasbornin1974,whenfurnitureexporters,unabletobuyrattanpoles

fromexporters,bandedtogethertolobbyagainsttheexportofrattanpoles.Shortlyafterwards,

the1976exportbanonrattanpoleswasimplemented;thetopfiverattanpoleexporters,inturn,

modernizeditselfbyhiringforeignconsultants,importingmachinery,andprofessionalizingits

ranksthroughoutthe1980s.

TheentryofrattanpoleexportersintothefurnitureindustrypavedthewayforCebus

furniture industry to penetrate markets in Europe, Canada, Japan, Australia, and South

America.Duringthetime,exportswereatUS$50millionannually,andrepresented60%to70%

ofallPhilippineexports;thePhilippines,alongwithTaiwan,weretheregionsbiggestfurniture

exporters.

Yettheexportbanwasnotabletoarrestthedwindlingsupplyofrattan,asanestimated

300,000 hectares of forestland were lost annually due to the massive deforestation in the late

1970sandtheearly1980s(TumanengDiete,Ferguson,&MacLaren,2005).Hence,theindustry

tapped Indonesia and Malaysia for its wood requirements. In turn, Indonesia, the worlds

largest rattan producer, eased out the Philippines as a major player in the global furniture

market by investing heavily on equipment and pirating skilled Filipino workers. On the other

hand, Malaysia, a major exporter of logs, sawn timber and wood products (plywood, veneer,

woodbased panels, wooden furniture, builders carpentry and joinery (BCJ), moldings) just

recentlybecameamajorplayerintheglobalfurnituremarket.

To protect their local furniture manufacturers, both Indonesia and Malaysia

implemented an export ban ontheir wood products, further pushing the cost of raw materials

uptoanaverageof40%ofproductioncost.Again,facedwithincreasingproductioncostsand

global markets in recession, Philippine furniture exporters again had to make institutional

adjustments.In1992,theexitof81%ofthefurniturefirmsledtotheindustrysnearcollapse;

only38outof200firmswereoperational.

The increasing costs of raw materials weighed heavily on the furniture industry

beginning in the 1980s. Fortunately in 1982, MaitlandSmith decided to locate at the Mactan

Export Processing Zone, bringing to Cebu its vast experience in design and marketing. This

markedwhatindustryplayersnowrefertoasaperiodofrenaissance.MaitlandSmithHong

Kongreproduced18

th

centuryfurnitureanddecorativeaccessories.MaitlandSmithallowedits

company designers to create signature or brand items, under strict quality control using

rattan,stonemosaic,coconutshellinlay,fauxtortoiseshell,penshellinlay,motherofpearl,faux

malachite,petrifiedwood,andfossilstone,amongothers(Nielson,2001).

Suffice it to say, MaitlandSmith was instrumental in upgrading Cebus furniture

industry. Its contributions included: (a) bringing professionals to the industry, (b) making

woodamoreprominentmaterialintheindustry,(c)initiatingthetrainingofworkersespecially

in wood working skills, (d) attracting new buyers to Cebu, (e) enabling subcontractors to

become exporters, (f) contributing to knowledge diffusion, and (g) experimenting with mixed

mediadesign.

Since 2000, the industry has faced market threats from new entrants to the global

furnitureindustry.In2003,Chinaexported1.3billionpiecesoffurniture,makingitoneofthe

worldslargestfurnitureexporters,intermsofquantity;andin2004,Chinarosetobecomethe

second leading furniture exporter in the world, next to Italy (CRI News Online, 2004). Today,

low production costs in China, Vietnam, Malaysia and Indonesia, lowpriced DIY (do it

yourself) IKEA furniture, and the creeping encroachment by China, Malaysia, Thailand and

Vietnam on the CFIs share in the global highend niche market also threaten the industrys

survival.

ThoughthePhilippinesshareintheglobalfurnituremarkethasdwindledtobelow1%,

Cebu has managed to retain a reputation as the Milan of Asia (Go, 2003). Schancknat,

German design consultant to the Cebu Furniture Industries Foundation, notes that Cebuanos

werethefirstinAsiatointroducedifferentmaterialsintoaveryuniquestyleofmixedmedia

1

.

B.DataandApproach

The industry profile is drawn from four sets of survey data: the Department of Trade

and Industrys (DTI) 1995 Benchmark Survey on the MicroCottage and Small Enterprises in

Cebu conducted by the Center for Research and CommunicationSouth (CRCSouth), the 2003

Organizational Diagnosis of Cebu Furniture Industry Foundation, Inc (CFIF) by management

consulting firm Organizational Performance Associates, Inc., the International Labour

Organizations (ILO) Case Study of Young Workers in the Furniture Industry of Cebu, and

Learning in Small Enterprise Clusters: The Role of Skilled Workers in the Diffusion of

KnowledgeinthePhilippines,aUniversityofAmsterdamPh.D.dissertation(Remedio,1996&

Beerepoot,2005).

Information on raw materials and markets were obtained from CFIF, news, and firm

websites, the National Statistics Office (NSO), and the Bureau of Export Trade Promotion

1

Mixedmediaistheharmoniousmarriageofmanmadewithnaturalmaterials;theinnovativeblendof

traditionalandthecontemporarylook;thecreativecombinationofsoft,flexiblefiberswiththesolid

sturdinessofwoodorstonesemphasizingthewiderangeofpossibilitiesthancanstillbeexploredwith

theuseoftwoormorematerials(Seno,2004).

(BETP). Data on exports generated by CITEMsponsored trade shows are included to measure

theircontributiontoexportsales.Industryspecifictrainingprogramsarelikewisefurnishedby

the CFIF. Firmlevel financial data are obtained from Top 5,000 Corporations 2002 and Top

7000Corporations2001.CFIFalsoprovidedaggregatedataontheprofitandcoststructuresof

selectedfurniturefirms.Financialratiosfromthesetwostudieswereusedasindicatorsofthe

industrys profit margin and degree of financial leverage. Female participation in the Cebu

furniture industry was gauged by using data from the 2003 DTI survey, CFIF List of Contact

Persons, and the 2000 Census of Population. The percentage share of Cebubased export

commodities, which share common raw materials and production processes with furniture

manufacturing, is used as an indicator of the extent of interfirm linkages in the cluster. In

additiontothesedata,informationregardingthedominanceofcertainfamiliesintheindustry,

resultsoftheCFIForganizationaldiagnosis,andcrosscountrystatisticsarepresented.

The industrial cluster and global value chain analysis approaches are adopted in this

study.Briefly,clusteranalysisfocusesontheroleoflocallinkagesinproductupgrading,while

the global value chain considers the role of global buyers (agents, retailers, or brandname

companies)inpushingforprocessandproductupgrading. In the context of

globalization, upgradinginnovation to increase valueaddedis a necessary condition for the

highroadtocompetitiveness.Theanalysisofindustrialclustersisfocusedontheroleoflocal

linkagesingeneratingcompetitiveadvantagesintheexportindustries(Pietrobelli&Rabellotti,

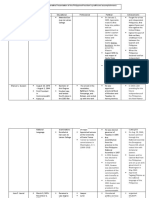

2004). Table 1 maps the different roles of clusters and value chains in governance and

upgrading(Humphrey&Schmitz,2002).

Table1:GovernanceandUpgrading:Clustersvs.ValueChains

Clusters ValueChains

Governance Horizontal. Close interfirm

cooperation and active private

andpublicinstitutions.

Vertical.Stronggovernancewithin

thechain.

Relations with

the external

world Armslengthmarkettransactions.

International trade increasingly

managed through interfirm

networks.

Upgrading Incremental upgrading (learning

by doing) and diffusion of

innovations within the cluster.

For discontinuous upgrading,

local innovation centers play an

importantrole.

Incremental upgrading made

possible through learning by doing

within the chain. Discontinuous

upgrading made possible by entry

intomorecomplexvaluechains.

Key competitive

challenge

Promoting collective efficiency

through interactions within the

cluster

Gaining access to chains and

developing linkages with major

customers.

Source:HumphreyandSchmitz,2002

Earlierstudiesprovideevidencethatclusteringenablesagroupoffirmsconcentratedin

one geographic location to achieve the gains of collective efficiency through local external

economies and joint action. Specifically, local external economies attract local suppliers, and

hencegiveclusteredfirmsbetteraccesstoinputsandrawmaterialsandcreateapoolofskilled

workers. Joint action, made possible by joining business associations, could help firms open

newmarketsandallowsmallfirmsaccesstogovernmentservices(Schmitz,1995).

Porter provides a succinct discussion on the role of clusters in economic competition.

Clusters, according to him, are critical, geographicallyconcentrated masses of unusual

competitive success in particular fields. Clusters encompass an array of linked industries and

otherentitiesimportanttocompetitionincluding,forexample,suppliersofspecializedinputs

andprovidersofspecializedinfrastructure.Clustersalsooftenextenddownstream(tochannels

and customers) and laterally (to manufacturers of complementary products and companies in

industries related by skills, technologies, or common inputs). Finally, many clusters include

government and institutions such as universities, standardssetting agencies, thinktanks,

vocationaltrainingproviders,andtradeassociationsprovidingsupportservices.

Porter also notes that clusters rarely conform to standard industrial classification

systemsbypromotingbothcompetitionandcooperation.Clusterspromotecompetitioninthree

ways: first, by increasing the productivity of clusterbased firms through (i) joint sourcing of

inputs, (ii) access to specialized information, technology and needed institutions, (iii)

complementarities among related industries, and (iv) better motivation and measurement

provided by local rivalry and peer pressure; second, by determining the direction and pace of

innovation;andthird,bystimulatingtheformationofnewbusinesses(Porter,1998)

Global value chain (GVC) emphasizes crossborder linkages between firms in global

production and distribution systems. Specifically, GVC proponents emphasize the role of

global buyers in the valueadding chain of activities carried out by different firms in different

locations. From this perspective, global buyers are instrumental in the upgrading of processes,

products,functions,andsectoralinnovations(Pietrobelli&Rabellotti,2004).

In a world of uncertainty, bounded rationality, and conflicting economic interests, the

coordination issueswhat, how, how much, and when to producehave spawned four types

ofrelationshipsinthevaluechains.Firstisthearmslengthmarketrelation,wherebuyerand

supplier do not develop close relationships and where product certification provides buyer

requirement standards. Second are networks, characterized by a more informationintensive

relationship,wherebuyersspecifycertainproductorprocessstandardsthatthesuppliershould

complywith.Thirdisthequasihierarchy,wheretheleadfirmexercisescontroloveritsdirect

suppliersandothersfurtheralongthechain.Andfourthisthehierarchy,wheretheleadfirm

takesdirectownershipofsomeoperationsinthefirm(Humphrey&Schmitz,2002).

Figure 2 illustrates the productiondemand interactions between the global value chain

andthelocalfurnitureclusterinCebu.Foreignbuyersincludewholesalers,directretailers,and

buyingagents.Productionismobilizedwhenforeignbuyersplaceanorder.Exporterssource

some of their raw materials abroad, hire freelance designers for product development (in the

absence of inhouse designers), or outsource some job processes to home workers. Buying

agents may be Filipinos or foreigners who maintain local offices tasked with organizing

production carried out by different manufacturers and subcontractors. Buying agents may fill

onecontainerwithproductscomingfromdifferentmanufacturers;freelancedesignersarehired

either by buying agents or exporters; and home workers and subcontractors tap local sources

fortheirrawmaterials.

Figure2:InternationalValueChainandLocalClusterofCebuFurnitureManufacturers

Theproductionoffurnitureexportsisafunctionofrawmaterials,thepresenceofother

firms, skilled workers, entrepreneurship, and support organizations such as business

associations, local government units, and national line agencies. From a strategic standpoint,

thePhilippinescannolongercompeteonthebasisoflowlaborcosts,cheapmaterials,andan

unregulatedlabormarket,asdoingsowilljusthastentheCebufurnitureindustrysracetothe

bottom. What the industry can and should do is take the high road: that is, product

upgrading, translating to efficiency enhancement, innovation, high quality productions,

functionalflexibility,andgoodworkingconditions(Pyke,Becattini&Sengenberger,1992).The

shift to mixed media in the use of raw materials, horizontal integration, and the reliance on

embeddedlearningaretheindustrysattemptstoimproveitselfalongtheselines.

Wholesalers Retailers

Rawmaterials,parts,

components

Buyingagents

Freelance designers

Exporters

Subcontractors

Localrawmaterials:wood,rattan,abaca,

stone, buri

Home

Workers

PHILIPPINE

ABROAD

Source: (Beerepoot, 2005)

III.THECEBUFURNITUREINDUSTRYTODAY

A.RawMaterials

In the 1980s, the Philippines was one of Asias top supplier of furniture exports (Table

2).Forinstance,thePhilippinesin1987exportedUS$173millionofwoodenfurnituretoOECD

countries, next to Taiwan and China (US$185 million) and ahead of Korea, Thailand, Hong

Kong, and Singapore. During the same year, the United Kingdom imported its furniture

requirements from developing economies, led by Taiwan, Philippines, and Singapore. The

following year, the US furniture market saw 84% of its wooden furniture imports come from

Asian countries, led by Taiwan and the Philippines. Notably, the Philippines then had 54%

(US$161 million) of the US imported rattan furniture market. The Philippines was likewise a

major supplier of rattan furniture to Japan, with an 8% market share behind Taiwan and

Indonesia(InternationalTropicalTimberOrganization,1990).

Table2:ThePhilippinesShareinFurnitureImportsofSelectedCountries,19871988

1987 1988

OECD

(inUSD

million)

(in%)

U.S.

(inUSD

million)

(in%)

TotalFurnitureImports 18,332 100.0WoodFurnitureImports 1,209.44 100.00

Asia 2,573 14.0Asia 1019.68 84.00

Taiwan 1,848 10.1Taiwan 599.189 50.00

China 186 1.0Philippines 110.401 9.00

Philippines 173 0.9Singapore 64.147 5.00

Korea,Republic 170 0.9Thailand 63.197 5.00

Thailand 140 0.8Korea,Rep. 53.854 4.00

HongKong 90 0.5HongKong 31.131 3.00

Singapore 88 0.5China 13.396 1.00

1988 1988

Japan

(inYen

million)

(in%)

U.S.

(inUSD

million)

(in%)

RattanFurnitureImports 18,631 100.0RattanFurnitureImports 161.204 100.00

Asia 18,521 99.0Asia 159.038 99.00

Taiwan 13,637 73.0Philippines 86.336 54.00

Indonesia 2,320 12.0China 34.843 22.00

Philippines 1,450 8.0Taiwan 20.915 13.00

China 627 3.0HongKong 10.901 7.00

HongKong 193 1.0

Thailand 182 1.0

Sources:OECD,UnitedStatesInternationalTradeCommission,InternationalDevelopment

AssociationoftheFurnitureIndustryofJapan.

The golden age of furniture exports in the Philippines saw the Cebu furniture

industry lead all others in generating furniture export revenues for the country, with most

coming from rattan (Tables 3 and 4). The declining market for rattan furniture exports,

however,forcedaswitchtomixedmediaproduction,wherewood,metal,stone,bamboo,and

plasticarealsoused.Table5isadetailedlistoftherawmaterialsusedbyCebufurniturefirms.

Table3:CebuFurnitureExports

Year

Cebu

(inUSDmillion)

Philippines

(inUSDmillion)

CebuShare

(in%)

RattanSharein

CebuExports

(in%)

1985 61.6 83.7 73.6 78.3

1986 63.1 89.4 70.6 79.8

1987 84.1 130.4 64.5 78.5

1988 117.4 183.7 63.9 73.8

1989 119.5 203.7 58.7 73.6

1990 103.8 189.5 54.8 66.3

1991 101.9 177.2 57.5 63.4

1992 119.2 181.2 65.8 63.6

1993 92.6 203.2 45.6 56.3

1994 86.2 238.6 36.1 32.2

2002 211.0 316.0 66.8 11.5

Sources:DTIRegionVII;Remedio,1996andBeerepoot,2005.

Table4:ValueofCebuFurnitureExports,2003

Value

(inUSD)

Percent

(%)

Wood 58,111,308 53.18

Rattan 27,165,518 24.86

Metal 16,415,086 15.02

Stone 3,703,010 3.39

PartsofFurniture 1,453,052 1.33

OtherMaterials 1,151,307 1.05

Bamboo 790,032 0.72

Plastic 334,485 0.31

Furnishings 137,746 0.13

Buri 12,566 0.01

Total 109,274,110 100.00

Source:NationalStatisticsOfficeandBureauofExportTradePromotion

Table5:RawMaterialsUsedbyCFIFMembers,2004

Woodbased Amount StonebasedAmount IndigenousAmount ManufacturedAmount

Wood 104 Stone 83 IndigenousMaterials 7 WroughtIron 97

Veneer 4 Romblon 2 AbacaWoven 17 Metal 20

Rattan 80 Ceramics 2 NaturalFibers 2 CastAluminum 6

Rattanveneer 1 Tiles 1 Cotton 1 Brass 4

CloseCane 1 PhilAlabaster 1 Anakao 1 Steel 1

Wicker 14 RecycledGlass 1 Lampakanai 3 Plastic 5

Bamboo 13 Fiberglass 17 Turnsole 1 SyntheticWicker 1

Buri 6 Seagrass 3 Dexin 2

Coconut 4 MotherofPearl 1 Prolen&Prolex 1

CastResin 6 Shells 2 Upholstery/Vinyl 2

ManMadeBoards 5 LeatherInlaid 22

MediumDensityFiber 2 Accessories 18

Lamination 1

Total 241 107 38 161

Average 1.4 0.6 0.2 0.94

Source:CebuFurnitureIndustryFoundation(CFIF)Website

1. Rattan.

RattaniseitherlocallysourcedfromneighboringislandsorimportedfromPapuaNewGuinea

andBurma.Pabuayon,RiveraandEspanto(1998)mentionedthat

Rattan products generate more than US$200 million annually in 1994, with an

estimated 4 million dependent on the sector. Major rattan production areas

include Apayao (Conner and Kabuyao), Cagayan Valley (Baggao), Palawan

(Puerto Princesa), Bukidnon (San Fernando) and plantation sites in Bislig,

SurigaodelSur(PaperIndustriesCorporationofthePhilippines)andTalacogon,

AgusandelSur(ProvidentTreeFarms).ThemajordemandareasarePampanga

(San Fernando and Angeles City), Cebu (Cebu City and Mandaue City), and

MetroManila,LagunaandQuezon.

Therattanmarketparticipantsinclude:

i) gathererswhoaremostlytribalpeopleandcouldbemembersornon

membersofagatherersassociation

ii) gatherers associations, composed of gatherers residing in particular

upland communities and organized for the purpose of obtaining a

rattancuttingpermitorundertakingotheractivities

iii) plantation owners who initiated rattan planting on their own or

throughgovernmentreforestationprogram

iv) rawmaterialtraderswhomayormaynotholdpermits

v) manufacturers who include producers of furniture and handicraft

items

vi) workerswhoincludesubcontractorsandinhouseworkers

vii) finished product traders who are engaged in trading at the domestic

orforeignmarketorboth

viii) transporterswhoincludetruckersandshipper

The study shows that the gatherers share of product value averaged only 5

21%, about 63.87% went to the manufacturers and the rest to the traders. The

shares refer to both profit and costs incurred. The higher added value of the

manufacturer refers to the associated costs of producing rattan furniture. The

addedvalueofthetraderincludesthetransportrelatedcost.Ingeneral,thecost

component of marketing margin for the market participants exceeds the profit

component. For instance, traders realize about P46.17 net return per 100 lm of

rattan shipped or P30,232 per shipment. Forest charges, which are based on

misdeclaredshipment(onlyaboutonethirdofactualvalue)compriseabout14%

of total costs, while bribes, which make underreporting possible, are about 8%.

Thefullcharges,ifpaid,wouldamounttoP64.63per100lm.Withoutthebribes,

net return would still be positive at P36.58 per lm or P25,913 per average

shipment of 65,476 lm. Transport cost comprises 19% of total cost. If it can be

lowered, then higher profit rates are possible. Another illegal practice involves

multiple uses of transport documents which means that profits are higher since

no forest charges are paid (although bribes are still paid) in second or third

shipments.

2.Wood

Lumber is available in the domestic market, with lauan and tanguile as the most

commonly used species. Plantation species like rubberwood and gemelina are used for

particleboards, while medium density fiberboard (MDF) is popular material for panels and

officefurniture.Importedwood,mainlysourcedfromMalaysia,Brazil,NewZealand,andthe

US,includeHondurasandBrazilianmahogany,pine,oak,beechcherry,andmaple.Veneer,a

thinsliceofexoticwoodorothermaterials,isappliedoverathickerbackingtomakedecorative

materialsmoredurable.

3.Stone

The stonecraft industry, originating from the neighboring island of Negros Oriental,

crossedovertoCebu,which,inturn,useditfordecorativefurniture.Stonebasedtabletopsare

made with wooden carcasses and laminated with pieces of fossilized stones colored white,

beige,gray,coral,greenandblack.Cebuanofirms,usingfossilizedstoneasarawmaterialfor

their furniture exports generally cater to the Middle East market. Nonetheless some Cebuano

furniture firms cite health hazards and the relatively high cost of stone cutting as the primary

reasonsfortheirdecisionnottomakestonebasedtabletops.Cebuisexportingfossilizedstones

asrawmaterialstoChinasfurnitureindustry.

4.MixedMedia

Mixedmedia furniture combine conventional materials like rattan, wicker, buri, wood,

metal, stone craft, bamboo, and plastic with tems such as grasses, shells, coconut lumber and

leather. For instance, lava stone designs consist of recycled waste materials laid, crushed,

compressed,andmixedwithchemicalstoresultinstonelikeproducts.Otherproductsinclude

mixedmedia sofas with metal skeletons wrapped in rattan splits; cabinets featuring bamboo

twigs encased in oak wood frames; furniture finished with signature veneers from bamboo,

sugarcane and coconut; and laminated tabletops from banana tree barks, corn husks, spliced

coconutrootsandeventermiteeatenwood(Seno,2004).

Mixed media metal furniture, on the other hand, combines wrought iron with wicker,

wood, seagrass, and other indigenous materials. Examples are Prelen and Prolex, patented

syntheticmaterialssimulatingrattan,bamboo,abaca,rustedmetal,bark,wood,willow,wicker,

hickory, and wrought iron. It is resistant to chemicals, weather, humidity, and water. Plastic

furnitureislargelydesignedforoutdooruse.

B. InterfirmCooperation

The Cebu furniture cluster fosters horizontal integration through close interfirm

cooperation.Thisisanalternativewayoforganizingthevaluechain:

The proximity of companies and institutions in one location, and the repeated

exchanges among them, fosters better coordination and trust. Thus clusters

mitigate the problems inherent in armslength relationships without imposing

theinflexibilitiesofverticalintegrationorthemanagementchallengesofcreating

and maintaining formal linkages such as networks, alliances, and partnerships.

A cluster of independent and informally linked companies and institutions

represents a robust organizational form that offers advantages in efficiency,

effectivenessandflexibility(Porter,1998).

Table6listsCebuexportsthatsharecomplementaryinputswiththefurnitureindustry,

representing 36% of total Cebu exports. Furniture exports, for example, share similar

intermediateinputswithhousewaresandgifts,toys,andhandicrafts(GTH).Thisisduetothe

use of mixed media in these industries. Aside from the use of common raw materials,

complementarities occur in the industries sharing of designs, skilled workers, machinery and

equipment, and quality control standards, among others. This allows visiting buyers to see

manyvendorsofdifferentexportproductsinasingletrip(e.g.attendingtheCebuX).

Table6:CebuExportProductsUsingComplementaryInputs,2003

(ValueinUS$1,000)

Housewares Value

Basketwork 7,156

Wickerwork

Shellcraft 467

Woodcraft 229

Ceramics/Stoneware 1

Textilearticles 38

Flowerarticles 28

Metalware 1

Glassarticles 30

Otherarticles 2,518

SubTotal 10,468

(2%)

ConsumerProducts Value

FashionAccessories 9,914

Garments 53,970

HolidayDcor 1,051

Toys 45

Giftware 8,131

Woodwork 3,461

ConsumerProducts 5,126

SubTotal 81,898

(16%)

FoodandResourceProducts Value

MarineProducts 18,855

Mineral 1,028

Coconut 2,939

ForestProducts 300

Seaweeds 37,246

Marble 144

Cutflower 6

Twine 8,518

Nonmetallicmineral 7,904

NaturalFibers 24

OtherResource 4,358

SubTotal 79,964

(15%)

Table6:CebuExportProductsUsingComplementaryInputs,2003

(ValueinUS$1,000)

IndustrialManufactures Value

Metal 540

Construction 7,755

Chemicals 7,314

Packaging 303

Others 3,241

SubTotal 19,153

(4%)

ExportsofComplementaryInputs 188,483

(36%)

CebuExports 521,791

Sources:NationalStatisticsOffice(NSO)andBureauofExportTradePromotion(BETP)

To illustrate the horizontal integration or interdependenceof different industries in the

Cebu cluster, a comparison between the furniture and fashion accessories is made in terms of

rawmaterialusage,machineryandequipmentuse,anddesignsources.AsperTable5,thetop

rawmaterialsusedinfurniturearewood(65%),wroughtiron(60%),stone(52%),rattan(50%),

leather inlaid (14%), metal (12%), accessories (11%), abaca (11%), fiberglass (11%) and wicker

(9%). To some extent, this overlaps with those most used in making fashion accessories: shells

(84%), wood (68%), coco shell (56%), resin (52%), metals (28%), bamboo (20%), chains (16%),

glassbeads(16%),glass(12%),andsemipreciousstones(12%).

An interview with a designer revealed that the excess shavings of furniture raw

materialsaresometimesusedinthemanufactureoffashionaccessories,andthatmaterialssuch

asstoneinlay,firstintroducedforsmallitemslikegiftsandtoys,arenowusedinthefurniture

industry(Interview1).WecloselywatchtheGifts,ToysandHardwaresectorfornewproduct

ideas.Inthatsector,thetrendsgomuchfaster.Theyhavetobemoreinnovativeandcomeup

withnewideasmoreoften.Wealsooftenvisitlocalandregionaltradefairsthatareorganized

by DTI. In the countryside, people are more innovative in experimenting with indigenous

materials.Ourdesignteamoftengoestotheprovincesfornewideas.Anexampleismydesk

from laminated coconutshells. At first, laminated coconut shells were only used for picture

frames.Weintroducedthematerialforfurnitureproductionandmadeanentiredeskfromit

(Beerepot,2005;Interview1)

Based on key informant interviews, interfirm cooperation takes the form of

subcontracting,endingofmaterials,sharingofbuyers,consolidationofsmallshipmentsandthe

bandwagon effect. One company interviewed, Company A, however, claims that full

cooperationisnotpossiblebecausefurnitureisajealousandsecretiveindustry(Interview2).

To avoid being drawn to discussions on pricing and raw material sources, this company shies

away from CFIFsponsored social gatherings; then again, it lends materials to other furniture

firmsandofferstheuseoftheirslowmovingmaterialstosmall,startupfurniturefirms.

In the caseof another company, Company B,subcontracting is limited to some veneer

andwoodproductsandonlytoCompanyBsMultipurposeCooperativewhosemembersare

former employees retrenched more than 10 years ago when the highcost of rattan forced the

companytodiscontinuethisproductline.CompanyBencouragedtheretrenchedemployeesto

organizeacooperative,andprovidedspaceforaworkingarea.Today,thecooperativehasits

ownbuilding,hasassetsofuptoPhp8million(someinTbills),andsuppliesthecompanywith

rattan poles and other materials, aside from labor contracting. The president of Company B

claims to be sharing materials and information with competitors A company cannot do

everything. From his 20 years of experience in operating six furniture plants, he shares with

otherindustryplayersinformationandlessonsonthedifferentstandardsforrattan,wood,etc.

(Interview3).

Table7:RawMaterialsUsedinCebuFashionAccessories:2005

Imported

Local

Direct LocalTraders

Total

Materials

No. Percent No. Percent No. Percent No. Percent

Shells 21 84.00 21 84.00

Wood 16 64.00 1 4.00 17 68.00

Cocoshell 14 56.00 14 56.00

Resin 11 44.00 2 8.00 13 52.00

Metals 4 16.00 2 8.00 1 4.00 7 28.00

Bamboo 5 20.00 5 20.00

Chains 1 4.00 2 8.00 1 4.00 4 16.00

GlassBeads 2 8.00 2 8.00 4 16.00

Glass 2 8.00 1 4.00 3 12.00

Semipreciousstones 1 4.00 2 8.00 3 12.00

Beads 1 4.00 1 4.00 2 8.00

Leather 1 4.00 1 4.00 0.00 2 8.00

Plastics 1 4.00 1 4.00 2 8.00

Raffia 2 8.00 2 8.00

Acrylics 1 4.00 1 4.00

Adhesives 1 4.00 1 4.00

Bones 1 4.00 1 4.00

Carabaobone 1 4.00 1 4.00

Chemicals 1 4.00 1 4.00

Chords 1 4.00 1 4.00

Crystals 1 4.00 1 4.00

ElasticGarters 1 4.00 1 4.00

Fiber 1 4.00 1 4.00

Horns 1 4.00 1 4.00

Metalcasting 1 4.00 1 4.00

Paint 1 4.00 1 4.00

Pearls 1 4.00 1 4.00

Sandpapersandabrasives 1 4.00 1 4.00

Silver 1 4.00 1 4.00

Sinamay 1 4.00 1 4.00

Table7:RawMaterialsUsedinCebuFashionAccessories:2005(continued)

Imported

Materials Local

Direct LocalTraders

Total

Stones 1 4.00 1 4.00

Syntheticbeads 1 4.00 1 4.00

WaxChords 1 4.00 1 4.00

Wires 1 4.00 1 4.00

Woodbeads 1 4.00 1 4.00

Source:Interviewwith25ManufacturersofFashionAccessories,January2005

Company C, serving solely Global Buyer 1, subcontracts to individuals and families to

cut down costs, with skills and disciplines handed down to subcontracting parties as part of

their cultural heritage (Interview 4). Company D, for its part, claims that depending on the

closenessofpersonalrelationships,firmssharebuyerssubjecttosomelimitations(Interview5).

CompanyEadvancesmoneytosubcontractorsandagreestoconsolidatesmallshipmentswith

its competitors (Interview 6). Company Fs owner, interestingly, set up a furniture export

businessin1983inhopesthathewillbeasaffluentasotherCebuanoexporterswere(Interview

7).

C. RoleofSkilledWorkersinKnowledgeDiffusion

ThissectiondrawsheavilyfromtheworkofBeerepot(2005),whichemphasizedtherole

of skilled workers in knowledge diffusion. Competent entrepreneurs and an adaptable, well

trainedlaborarekeystoinnovationandproductupgrading(Scase,2000).

Collective learning is a source of competitiveness for regional clusters, especially

because of the shared knowledge base of entrepreneurs and workers engaged in the local

production system that initiate innovations and upgrades (International Labour Organisation,

2002).Theknowledgeandknowhowofskilledworkersareintangibleassetsthatenhancethe

international competitiveness of regions. On that note, since an important aspect of collective

learning is the development of trust among the industrys stakeholders, it is necessary to

identify how interpersonal and interfirm relations enable the diffusion of knowledge within

theCebufurniturecluster.

1.LaborMarketSegmentation

Table 8 demonstrates the highly segmented nature of the labor market, with the co

existenceofhighlyeducatedandlearningbydoingworkers.Thislabormarketstructureisdue

to how production is organized. Beerepot (2005) further distinguishes between knowledge

protectors and knowledge transmitters. Knowledge protectors (entrepreneurs, production

managers, designers) treat their knowledge in specialized production and design skills as a

scarce good, and do not share their contacts (international buyers, subcontractors, or

productionsource)withtheirpeersintheindustry.Knowledgetransmittersareworkerswith

limitedformaleducationwholearntheirskillsprimarilyonthejob.Theyarehighlyskilledin

weaving and intricate woodcarving, for instance. Knowledge transmission occurs when these

skilledworkershireapprenticesorassistantstoincreaseproduction.Thepracticeofpiecerate

payment of skilled workers encourages the craftsmen to bring in a young helper. This

arrangement,ofcourse,hasitsdisadvantages:

Entrepreneursandproductionsupervisorshavelimitedwillingnesstoinvestin

workers skills, training and technological capacities. The fear that other

companies will pirate production workers, or that workers will start companies

for themselves, often prevents investment in training. The little attention to

trainingandskillsdevelopmentisageneraltrendindevelopingcountryclusters,

as pricebased competition is still predominant here. Several entrepreneurs in

Cebu ask leadmen in their company to start for themselves and work

exclusivelyassubcontractorsfortheircurrentemployer.Theadvantageforthe

entrepreneur is increased informal production environment. The second

advantage is that the loyalty of the subcontractor, based to a large extent on

dependency, prevents the leaking of knowledge or the stealing of ideas.

Through this process, the company can outsource production activity, but still

retain control of key knowledge. The subcontractor is, in this context, so much

weakeranddependentthatitcanbequestionedtowhatextenthecanserveasa

sourceofknowledgeorfeedbackforexporters.

Table8:LaborMarketSegmentationintheCebuFurnitureIndustryinCebu

Category

Specialskilled,

secureentrepreneurs

andworkers

Skilledsecure

workers

Skilledsecure/non

secureworkers

Semiskillednon

secureworkers

Position Entrepreneurs,

production managers,

designers,draftsmen

Supervisors, leadmen

inbigcompanies

Leadmen, sample

makers, skilled

workers

(semi) skilled work

for subcontractors,

apprentices

Education Collegedegree College degree or

vocational

High school graduate,

(some)college

Elementary graduate,

(some)highschool

Occupationalstatus Regularemployees Regularemployee Regular and

contractual

Oncall, jobouter,

piecerateworkers

Sourceofknowledge Formal training, then

experience

Experience then

formaltraining

Onthejob,experience Onthejob

Additionaltraining Yes(some) Yes(some) No No

Jobsecurity Medium Medium Medium/low Low

Payment >150% of minimum

wage

Up to 150% of

minimumwage

Minimumwage Below minimum

wage

Locallabormobility Medium Medium High Veryhigh

Knowledgetransmitter No Little Yes No(receiver)

Knowledgeprotector Yes Yes No No

Source:Beerepoot(2005)

Entrepreneurs admit that they have little control over this process of transfer of

skills among workers. The availability of a large surplus of skilled production

workers in the local labor market is generally encouraged through their easy

willingnesstoshareknowledgeandteachotherstheirskills.Mostofthesurveyed

production workers indicated that they learned their skills primarily from other

workers, their leadmen or relatives. For lower hierarchy workers, apprentices or

helpers are not seen as a threat to their own position on the labor market. The

prospectthat,eventually,thesehelperswilllookforaskilledpositionhasnotmade

them more hesitant to share their knowledge. A high labor mobility of these

workers within the local industry can bring benefits to the entire industry, as

productionknowledgebecomesmorewidelyaccessible.Skilledworkersmightnot

alwayshaveasecurepositionwithintheparticularcompanywheretheywork,but

they feel their knowledge and skills give them the opportunity to easily find

employment elsewhere in the local industry. It can be questioned if a high labor

turnovercandistortthebuiltupofdistinctiveskillsinindividualcompanieswithin

theCebucluster.Undifferentiatedbasicproductionknowledgeandtechniquesare

widely available within this cluster, but the complementary knowledge and skills

necessarytostrengthentheindustrialbasearelimited.

When workers and subcontractors are employed under circumstances of limited

security of tenure, as are most workers in category three and four, they are more

willing to share knowledge and undertake common efforts. In these groups, the

cooperative spiritexiststhatpoorpeopleshouldhelpeachother.Thiscanbeby

training a young relative in a specific craft or when subcontractors help each other

toreachadeadlinefordelivery,orshareordersduringthelowseason.Interviewed

subcontractorsclaimedthatdiscussionswithothersubcontractorswereoneoftheir

key sources of market information. These contacts are important, as they have

difficult access to formal providers of information or knowledge from outside the

cluster.Forsubcontractors,thenecessitytoprotecttheirspecificknowledgehasnot

much importance. The scope for localized learning and interventions to stimulate

learning might, therefore, have most success at lower levels in the production

hierarchy. At this level, production knowledge and skills are already transmitted

easily.Whencompaniesexpand,orpeopleenjoyrelativesecurityinthelocallabor

market, the willingness to associate or undertake collective activity that should

encourageknowledgeaccumulationdiminished(Beerrepot,2005;7891).

Beerepot (2005) demonstrated that knowledge transmission in the furniture industry is

constrained by the local mode of production, characterized by the increased outsourcing of

work to the informal sector and the prevalence of piecerate payment schemes for workers.

Localvaluechainrelationsandoutsourcingstrategiesarebasedonthedominanceofexporters,

mainly to protect their own position in the value chain. Because of this, investments in skills

and capacities necessary for product upgrading are low. Hence, the majority of the workers

acquire their skills through informal mechanisms, and only a few undergo formal training to

augment their knowledge and skills. This production setup hinders the development of a

regional culture of trust and collaboration, which is a necessary condition for a localized

learningprocess.

2.MatchingofProcessesandSkills

The 2003 CFIF Study undertook a documentation of thirteen processes in furniture

making, the quality controls done for each process, and the modes of skill acquisition. The

resultsarereportedinTable9.(However,todate,thereisnoavailableskillcertificationorany

standard against which to measure the current levels of manpower skills in the industry.) The

findings show that skills on raw material preparation; assembly and carpentry; carving,

sanding,finishing,andpolishing;roughmillingandmachining;fiberglasscasting;upholstery;

leather inlay; and stone inlay and packaging are largely selflearned, obtained from work

experiences, or acquired from coworkers. On the other hand, formal training is required for

roughmillingandmachining,metalworks,productengineering,anddesignandmaintenance.

(Collegegraduatesdothelattertasks.)

Company A, which invested in machinery to cope with big orders, employs about 700

workers.Tominimizereturnedsales,qualityinspectionisdonebeforeshipment,inthetesting

laboratoriesofforeignbuyers.Thecompanypolicyisnottohireexemployeeswholefttowork

foranIndonesianorChinesefirm.CompanyB,meanwhile,complementsitshugeinvestment

inmachinerieswith2,000workers.Tocontrolproductquality,itavoidssubcontracting,except

toacooperativerunbyretrenchedemployees.Italsohiresprofessionalmanagers,hasitsown

testing facilities, engages in product development, and allows overseas buyers to bring in

technicianstotrainworkers(particularlyinwoodworking).CompanyCstartedasasmallfirm,

with just seven workers who now have been with the firm for more than three decades.

CompanyCsworkersperformmultiplefunctionsonarotationbasisandtheylearnbydoing.

Loyalty is rewarded by nonretrenchment during times of recession, and credits its Japanese

buyers for influencing them to continuously monitor product quality. Company D employs

homebased subcontractors; company F initially hired unskilled and unschooled workers until

theydraggeddownthefirmsproductivity.

Subcontracting or local outsourcing involves the production of all or parts of a final

product specified and marketed by an export firm outside the premises of the export firm.

Subcontractors employ family labor or a few hired workers or apprentices while operating on

verylittlecapital,utilizingalowleveloftechnologyandskills,andprovidinglowandirregular

incomes(InternationalLabourOrganisation,2002).Exportersadoptlocaloutsourcingtoreduce

cost, spread risks and avoid labor disputes, and have been used by the furniture industry to

adopt restrictive labor laws. When subcontractors are unschooled and lack managerial

competencies,difficultiescanarise,soaccordingtoonecompany,reducingthecommunication

gapbetweenlaborandmanagementimmenselyimprovesqualityandproductivity.

Duringthemid1980s,asubstantialnumberoffurniturefactoriesclosedshopbecauseof

laborunionswhichwentonstrike.Thisscenarioisnolongerpresentmainlybecausethelabor

market is quite tight, and in cases when workers of furniture firms are affiliated with labor

unions,employersmaintainharmoniouslaborrelations.CompanyDsaysitisagiveandtake

proposition.

Table9:MatchingofProcessesandSkillsintheCebuFurnitureIndustry,2002

Process Description SkillsInventory

Raw Material

Preparation

Plywood and solid wood are commonly used

materials, which are bought kiln dried. The

five most common wood working equipment

are:tablesaw,bandsaw,cutoffarmsawand

circular saw. Quality control is done by

comparing the material quality against a set

standardorbyitsmoisturecontent.

A few attended training courses, mostly on

developing supervision skills. Skills were

obtainedfromworkexperiences.

Rough Milling/

Machining

Most respondents processed solid wood,

mediumdensityfiberboardandplywood.The

five most common wood working equipment

are: surface planer jointer, thickness planer,

table saw, band saw and shape molder.

Quality control is done by comparing

measurements/dimensions against wood

qualityandspecificationsbasedonthecutting

list.

Most respondents attended training on

woodworking, furniture & cabinet making

and jigs & fixtures making. Skills were

obtainedfromworkexperiences.

Assembly/

Carpentry

The five most common furniture assembly

gadgets are: jigs, clamps, assembly machine,

cabinet press and rubber bands. Quality

controlisdonebycomparingtheworkagainst

job or customer specifications, fullsize

checklists,patternsorblueprints.

Attended training on furniture assembly.

Acquired skills from previous job, supervisor,

coworker,relative,selflearnedandschool.

Carving Qualitycontrolisdonebycomparingthefull

size detailed carving against the sample

picture.

Carving skills were mostly selflearned or

acquiredfrompreviousjob.

Sanding, Finishing

andPolishing

MostSMEsdrytheirfinishedproductsinopen

areas or under the sun. Quality control is

done by adhesive test and visual inspection,

comparing the color with the color swatches

and inspecting for crackles, pinholes, bubbles

orothermarks.

Finishing skills were mostly selflearned.

Some respondents were taught by supervisor,

coworkerandfinishingconsultant.

Fiberglass and

Casting

Quality control is done by comparing the

productwithjobspecifications.

Skills were selflearned, acquired from

previous job, supervisor or training on

fiberglassmaking.

Upholstery Quality of sewing, fitting, uniformity of foam

thicknessandcolorischecked.

Attended training on upholstery; selflearned;

acquiredfromcoworkerorpreviousjob.

LeatherInlay Leather inlays are tested for bubbles, edges

andgrains.

Learningbydoing; taught by supervisor, co

workerandpreviousjob.

StoneInlay Hairlines, stone grains, stone color and

adhesiontocarcassarechecked.Thehammer

testisusedtotestthestoneinlay.

Skills acquired from coworker, previous job,

supervisor,relativesandself.

MetalWorks Qualitycontrolisdonebycomparingwiththe

jobspecificationorperformingthedroptestor

heavyloadtest.

Obtained vocational course on Mechanical

Technology;previousjobasironfabricator.

Table9:MatchingofProcessesandSkillsintheCebuFurnitureIndustry,2002(continued)

Process Description SkillsInventory

PackingandCrating Quality control is done by comparing with

buyers standards or specifications, drop test

andadhesiontest.

Learningbydoing; taught by supervisor, co

employeeandtrainingonpackingstandards.

Product Engineering

andDevelopment

Qualitycontrolisdonebyfollowingamanual

or procedure in correcting quality defects and

product inspection (random sampling, batch,

process,lotsperbatch).

College degree (Architecture, Fine Arts,

Mechanical and Industrial Engineering);

Trainings

Maintenance Manual for preventive maintenance is

followed.Repairrecordsarekept.

Maintenancetraining

Source:IndustryAnalysis,CebuFurnitureIndustriesFoundation,Inc.

C.EntrepreneurialCompetence

There is an important distinction to be made between proprietorship and

entrepreneurship.Theentrepreneurisdrivenbytheneedtoaccumulatecapital,sohisdecision

is based on business factors; the proprietor is driven by the need to earn income. Since the

latterseconomicsurplusislikelytobeusedtosustainaspecificstandardoflivingratherthan

be reinvested in business, there is little capital accumulation (Scase, 2000). Recently,

organizations such as ILO, UNIDO, and GTZ have emphasized strengthening entrepreneurial

competence.Inbuyerdrivenvaluechains,producersareexpectedtoreceivetechnicaltraining

andinformationonproductsanddesignsthroughnetworkrelationswithforeignbuyers.

Beerepot (2005) considers entrepreneurs the most privileged group in the cluster in

termsofaccesstoknowledge.Anentrepreneurabsorbsknowledgethroughfourchannels:(i)

observingsimilarproducts,(ii)negativeaction,(iii)valuechain,and(iv)jointaction.Observing

similar products of other firms is a cheap means to absorb knowledge, although the scope for

knowledge absorption is quite small. For instance, when entrepreneurs attend trade shows,

they can observe fashion developed by competitors and may copy the designs if they wish.

Negative action results from freeriding behavior of rival firms, such as poaching of workers

and designs. Though the financial costs of negative action might be small, the social costs of

these actions might be high (ostracism). Global buyers encourage local producers to create a

market brand for their designs, to invest in new machineries, and to comply with quality

standards of foreign buyers. Joint action refers to the sharing of information through both

formalandinformalmechanism,motivatedbyarelationshipoftrust.

D. ProfitabilityofFurnitureFirms

TheprofitabilityoffurniturefirmscanbegleanedfromthedataontheTop5,000/7,000

Corporationsandthe2003CFIFSurvey(Table10).TheTop5,000Corporations(2002)include

29 Cebu furniture exporters and 5 Luzon furniture exporters, collectively contributing sales of

P2.123billion.Cebubasedfirmscontribute67%oftotalsalesandaccountfor53%ofthetotal

assetsoftheTop5,000Furniturecorporations.Theyrepresent86%oftotalequityandgenerate

94% of the profits of furniture firms. In fact, the profit margin for Cebu firms (4.52%) is 7.45

times more than Luzon firms (0.61%). The difficulties of Luzon furniture firms stem mainly

from liabilities, which make up 91% of their total assets. They are, unsurprisingly, highly

leveraged,withadebttoequityratioof1043%.Insimpleterms,theimplicationisthatifthese

firms would close today and the assets were sold, the owners would only receive 9% of total

assets.

Table10:SelectedFinancialIndicatorsforTop5,000/7,000FurnitureCorporations,20012002

2002 2001

Indicator

Cebu Luzon CebuShare Cebu Luzon CebuShare

F/SData(inP1,000)

TotalAssets(TA) 2,324,176 2,065,104 53% 3,562,497 2,075,416 63%

FixedAssets(FA) 1,407,623 410,385 77%

Liabilities 1,262,493 1,884,460 40% 2,485,029 1,843,268 57%

Equity 1,071,413 180,644 86% 1,077,467 228,550 83%

Sales 4,235,958 2,123,340 67% 6,973,719 2,041,594 77%

Profit 191,636 12,896 94% 273,906 18,514 94%

FinancialRatios(in%)

ProfitMargin 4.52% 0.61% 7.45 3.93% 0.91% 4.33

AssetTurnover 182% 103% 1.77 196% 98% 1.99

ReturnonAsset 8.25% 0.62% 13.20 7.69% 0.89% 8.62

ReturnonFixedAssets 19% 5% 4.31

DebttoEquity 118% 1,043% 0.11 231% 807% 0.29

%ofFAtoTA 40% 20% 2.00

%ofLiabilitiestoTA 54% 91% 0.60 70% 89% 0.79

%ofEquitytoTA 46% 9% 5.27 30% 11% 2.75

Source:Top5000Corporations(2002)andTop7000Corporations(2001)

The Top 7,000 Corporations (2001) include 43 Cebu and 13 Luzon furniture exporters,

contributing total sales of P5.638 billion. Cebubased firms contribute 77% of total sales and

accountfor63%ofthetotalassetsofthoseTop7,000furniturecorporations.Theyclaim77%of

total fixed assets, represent 83% of total equity, and generate 94% of the profits of furniture

firms. Even in 2001, Luzon firms were highly leveraged, and reported a lower percentage of

fixed assets compared to Cebu firms. Their return on fixed assets is a lowly 4.51%, as against

19.46%forCebufirms.

The 2003 CFIF Survey disaggregates profit and cost structures by asset size (Table 11).

Theindustryisdominatedbylargefirms,whichcapture41%oftotalsales.Medium,small,and

microenterprises account for 36%, 21%, and 2% of total sales, respectively. Profit rates of

microenterprisesarethehighestat9%,whilethoseoflargefirmsarelessthan1%.Inabsolute

terms, large firms registered the highest average profits at P5 million, while microenterprises

had the lowest average profit at P1.256 million. Raw materials claim a lions share (74% of

revenues)inmicrofirms,whilethecombinedlaborandsubcontractedlaborrepresentthebulk

of expenditures of large firms (45% of revenues). Large firms had the lowest share of fixed

assets to revenues at 20%, while small firms showed the highest buildup of fixed assets to

revenuesat406%.

The data indicate that firms have a tendency to continue investing in fixed assets until

becomingclassifiedasalargecompany,uponwhichitsrateofinvestment(relativetosales)

becomes lower than microenterprises. This suggests that furniture manufacturers are acting

moreasproprietorsratherthanasentrepreneurs.

Table11:ProfitandCostStructureofSelectedFurnitureFirms,byAssetSize,2002

(inPhPmillion,%inparentheses)

Variable Micro Small Medium Large Total

No.ofFirms 2 11 5 1 19

GrossSales 28.45 270.09 457.68 530.00 1,286.22

Percent (2.21) (21.00) (35.58) (41.21) (100.00)

GrossCost 25.80 249.92 443.11 522.00 1,240.82

Taxes 0.156 5.81 4.431 3.00 13.39

AfterTaxIncome 2.51 14.36 10.14 5.00 32.02

ProfitRate(in%) (8.83) (5.32) (2.22) (0.94) (2.49)

GrossCost 25.80 249.92 443.11 522.000 1,240.815

Labor 3.80 66.50 75.500 159.00 304.80

%Labor (13.36) (24.62) (16.50) (30.00) (23.70)

SubcontractedLabor 1.83 40.58 70.24 79.50 192.15

%SubcontractedLabor (6.42) (15.03) (15.35) (15.00) (14.94)

RawMaterial 19.01 115.10 185.31 201.40 521.71

%RawMaterial (66.84) (42.95) (40.49) (38.00) (40.56)

Others 1.15 26.85 112.06 82.10 222.15

%Others (4.04) (9.94) (24.48) (15.49) (17.27)

FixedCapital 8.18 1,096.01 277.88 104.9 1,486.972

%toRevenues (28.77) (405.80) (60.71) (19.79) (115.61)

AverageFixedCapital 4.09 99.64 55.58 104.90 78.26

Source:IndustryAnalysis,CFIF,2003

What could account for the better performance of Cebu furniture firms visvis their

Luzoncounterparts?OnepossiblereasonwouldbethedominanceoffamilyfirmsinCebu.In

manydevelopingcountries,familybusinessesplayanimportantroleinthenationaleconomy.

In response to globalization, family businesses had to obtain management resources such as

financial,human,andtechnologicalresourcesfromoutsidetheirfamilies(Shimizu,2004).

E.FamilyOwnershipofFurnitureFirms

How strong are family businesses in the Cebu Furniture Cluster? A tentative answer

canbegleanedfromthemembershipinformationobtainedfromtheCFIFwebsite(Table12).It

seemsthatsomefamilieseitherownmorethanonefurniturefirm.Specifically,32%oftheCFIF

memberfirmsarecoownedbyfamilies.Some68%ofCFIFfirmslistcontactpersonswhoare

nonfamilymemberstaskedtoattendCFIFandrepresentthefirminCFIFfunctions.

Table12:ContactPersonsforCFIFActivities

ContactPersons

Numberof

Persons

Percentage

Family 55 32%

SameRepresentativeinCFIFFirms 12 7%

FamilyMemberRepresentativeinCFIFFirms 43 25%

IndependentRepresentative 116 68%

Total 171 100%

Source:CebuFurnitureIndustryFoundation(CFIF)Website

ThedesignationoffirmrepresentativesinCFIFactivitiesisshowninTable13.Fromthe

information,itcanbeinferredthatfunctionssuchasoverallmanagement,productionandsales

management, finance and designing are reserved for family members. This practice might

explain the protectionist behavior among key persons in the industry referred to by Beerepot

(2005). This, in turn, hinders the development of a regional culture of trust and collaboration,

which is a necessary precondition for localized learning processes. Another consequence of

protectionisttendenciesislowinvestmentinskillsandcapacityupgrading.(Ontheotherhand,

familyenterprisescanmakeimportantstrategicdecisionsfasterthanusual.)

Table13:CFIFRepresentatives,byPositionandGender

Position

Male Female Total

Male

(in%)

Female

(in%)

President 75 8 83 90 10

CEO 6 1 7 86 14

VicePresident/COO/OIC 7 7 14 50 50

ManagingDirector/GeneralManager 28 10 38 74 26

VPFinance/FinanceOfficer 2 5 7 29 71

Operations/ProductionManager 2 3 5 40 60

VPMarketing/MarketingManager 3 12 15 20 80

Designer 2 0 2 100 0

Total 125 46 171 73 27

Source:CebuFurnitureIndustryFoundation(CFIF)Website

All of the key informants run familyowned furniture firms. For Company A, key

positionsareheldbyfamilymemberswhohavesomeforeignheritage;policydirectionsareset

by family members, though employees who help run the company are treated as parts of the

family. This company recently ventured into Vietnam while retaining Philippine operations.

Company B, during its early years, was run by a husband and wife management team. At

present, plant managers are nonfamily members who participate in a profitsharing scheme.

Interestingly, Company B is open to transferring operations to other countries. Company C is

managed by the mother and assisted by two sons (handling marketing and accounting) and a

brother (in charge of planning, logistics, systems and control). Company D, like A, limits key

positions to family members. The highest position that an employee can reach is plant

manager. Company Es team is composed of the husband as the president, the wife as vice

president, the son as finance business manager, and the daughter as the corporate secretary.

The husband is incharge of marketing and production, while the wife oversees the finance.

Company F has a husbandwife tandem with the husband handling sales and the wife

designingtheirproducts.

F. GenderandIncome

ItisworthnotingthatwhileoverallmanagementandproductdesigninCFIFfirmsare

maledominated, finance, production, and sales work are largely handled by females. A more

comprehensive picture of the distribution of furniture workers in Cebu is given by the 2000

CensusofPopulationisused(Table14).SincetheCensusdidnotidentifytheworkersengage

specifically in the furniture industry, the following occupation codes were used as proxy

indicators: code 714 (painters and related trade workers), code 721 (metal molders, welders,

sheet metal workers), code 733 (handicraft workers in wood, textile, leather) and code 742

(woodtreaters,cabinetmakersandrelatedtrade).

The census data on the 10% sample of Cebu households show that furniture workers

comprise 14% (47,050) of the provinces total population. Stratification reveals that Mandaue

ranksfirstintermsofestimatednumberoffurnitureworkers(9,790),followedcloselybyCebu

(9,710), and Lapulapu a distant third (4,850). Contrary to perceptions of key informants,

furniture workers are predominantly male (81%). Regardless of gender, the median age of

furniture workers was 32, while the median educational attainment was Second Year High

School. The census data likewise show that child labor (below 15 years old) is a production

input,andconversely,thatthereareagedbetween90to99stillinvolvedinfurniturework.

The 2003 DTI Furniture Industry Profile also states that only 43% of the sample were

women. Only mediumsized firms hired more female workers, largely due to the presence of

semiskilledfemaleworkers.Largefirmsreportedhavingmoremaleemployees.

Table14:NumberofFurnitureWorkers,byAgeandEducation,2000

AgeofWorkers(inyears)

Location No.ofWorkers

Median Range

Education

Male Female %Female Male Female Male Female Male Female

Cebu 3,806 899 19% 32 32 1099 1187 HSII HSII

Mandaue 716 148 17% 32 33 1174 1272 HSII HSII

CebuCity 823 148 15% 33 33 1090 1567 HSIII HSIII

LapuLapuCity 422 63 13% 32 30 1580 1756 HSII HSII

Others 1845 425 19% 32 32 1299 1187 HSI HSI

Source:2000CensusofPopulation

With regard to monthly income, the information shows that wage rates among males and

females by work category do not have much variation (Table 15). For instance, the median

monthly incomes for both male and female managers are over P10,000. The median monthly

income for males is higher than females, however, for supervisory, specialist, and semiskilled

laborposts.Ontheotherhand,femalesearnahighermedianmonthlyincomeformultiskilled,

skilled, and unskilled labor. On the whole, male workers earn slightly more than female

workers(1.34%);therateofvariationbetweenmaleandfemaleworkersrangedfromalowof

4.29%forunskilledworkerstoahighof2.82%forsemiskilledworkers.

Table15:EmploymentSizeandMonthlyIncomebyPosition,2003

EmploymentSize/

MonthlyIncome

ManagerialSupervisory

Specialist/

Support

Staff

Multi

skilled

Labor

Skilled

Labor

Semi

skilled

labor

Unskilled Total

EmploymentSize

Micro:9orLess 47 36 29 17 10 21 21 181

PercentFemale 38% 44% 48% 47% 50% 62% 52% 47%

Small:10to99 8 17 10 25 32 27 11 130

PercentFemale 50% 35% 30% 36% 38% 37% 36% 37%

Medium:100to199 2 3 5 8 2 20

PercentFemale 50% 67% 60% 63% 50% 60%

Large:200andAbove 3 7 2 1 13

PercentFemale 33% 29% 0% 0% 23%

Totalofpercentsample 55 53 41 48 54 58 35 344

PercentFemale 40% 42% 44% 42% 41% 48% 46% 43%

MedianIncome(inP)

Males >10,000 7,333.83 5,653.36 5,176.97 4,750.51 4,333.83 2,375.09 5,455.05

Females >10,000 7,176.97 5,538.96 5,385.12 4,788.21 4,214.79 2,481.65 5,382.85

%Difference 2.19% 1.74% (3.86%) (0.79%) 2.82% (4.29%) 1.34%

Source:2003DTIFurnitureIndustryProfile

G.LocalSupportOrganizationsandStrategicAlliances

Localeconomicdevelopmentisenhancedwiththeestablishmentofpartnershipsbetweenlocal

governments and community and civic groups in managing existing resources, creating jobs,

andstimulatingeconomicactivity(Helmsing,2003).InEurope,clusterdevelopmentproceeded

in two stages: spontaneous growth, then institutionally enhanced growth (Gereffi, 1999). It is

in the second phase of cluster development that local support institutionsbusiness

associations,localgovernmentunits,nationallineagencies,educationandtraininginstitutions

andforeignfundingagenciesplayavitalrole.

Figure 3 depicts the sources of knowledge and its transmission. Business associations,

localgovernments,andeducationandtraininginstitutionsarethemainlearningfacilitatorsand

knowledge sources in the furniture industry. Foreign buyers, the business community, and

external sources (exhibits, the Internet, magazines, foreign donor organizations, etc.) are

contributors of knowledge in the furniture industry. The entrepreneur then transmits

knowledgetosubcontractors,rankandfileemployees,andskilledworkers.

Figure3:LearningStakeholdersatClusterLevel

1.CebuFurnitureIndustryFoundationandStrategicAlliances

Withdailyoperationshinderingfirmsfromconductingjointprojectsandinitiatives,the

business association is responsible for cooperative activities that would otherwise not be

undertaken by individual firms. In the Cebu furniture industrys case, before the CFIF, there

wastheChamberofFurnitureIndustryPhilippinesCebuestablishedin1974torespondtothe

threatofdecliningrattansupply.Theorganizationwassuccessfulinlobbyingforanexportban

on rattan. In 2002, CFIPCebu disassociated itself with CFIPManila to form CFIF due to

concerns about the Cebu furniture industrys declining US market share, the expansion of

ChinaandVietnam,andanincreasinglynegativeoutlookfortheindustryasawhole.

The following year, the CFIF held a Buyers Forum to consult with exporters, buyers,

suppliers, subcontractors, otherindustry exporters, and government. In 2004, CFIF celebrated

its 30

th

year, growing from an eightmember to a 172member business association (now

LearningFacilitatorsandKnowledgeSources

Localgovt

units

Business

associations

Educationand

traininginstitutions

Entrepreneurs Internationaloutlook

Productionorganization

Market trends

Subcontractors

*Materials

*Production

knowledge

*Reputation

ofexporters

Rankandfile

workers

*Production

skills

*Critical

enablingskills

*Labormarket

Skilledkeyworkers

*Specificjobskills

*Organizational

skills

*Accesstonetworks

ofworkersand

LABORFORCE

Source: Beerepot (2005)

including subcontractors). CFIF members are given the opportunity to join trade and study

missionstointernationalfurnitureshowsinNorthAmerica,Europe,theMiddleEast,andAsia.

CFIF organized the participation of Cebu exporters in international trade shows in Cologne

(Germany),Milan(Italy),Tokyo(Japan),Dubai(UnitedArabEmirates),andShanghai(China).

From July 2003 to June 2004, CFIF sponsored a total of 25 training programs involving

430 training hours attended by 494 participants, or an average of 20 participants per training

program(Table16).Outofthe25trainingprograms,20wereshorttermseminarswhile5were

longtermtrainingprograms.

Table16:ListofCFIFTrainingProgram,July2003June2004

ShortTermSeminars LongTermTrainingPrograms

ManagementofChange SupervisorsProductionCapabilityfor

CustomerServiceEnhancementProgram FurnitureManufacturingOperations

QualityandCostEffectiveFurnitureFinishingSeminar

ReinforcedPlasticsFurnitureManufacturing:Working

withFiberglass

FurnitureandCabinetMaking(FCM)

Technology

TotalQualityManagement(TQM)

EnvironmentalManagementSystems SupervisoryDevelopmentProgramforFurniture

StrategicCompensation ManufacturingOperations

JigsandFixturesTechnology

FocusonLeather MarketingManagement

DecorativeProcessofGoldLeafing(Gilding)

MarketingThroughPrintedSalesLiterature PrinciplesandApplicationsofManagement

BasicsofFairParticipationandBoothDesignsand

VisualMerchandising

FSCCertification&ItsImportancetotheFurniture

Industry

CompetitivePricingforMaximumMarketability

ReproductiveHealth&GenderSensitivity

DesignTrendsandMarketingUpdatingBriefing

MachineandEquipmentMaintenance

TimberandLumberDrying:FocusonSolarDrying

PEPPEnvironmentManagementWorkshop:Batch1

PEPPEnvironmentManagementWorkshop:Batch2

Source:CFIF2004AnnualReport

The CFIF 2004 Annual Report enumerates several strategic alliances with other

organizations.TheBusinessLinkagesProject(BLP),facilitatedbyDTIundertheEntrepreneur

SupportProgram(ESP)oftheCanadianInternationalDevelopmentAgency(CIDA),assistedin

institutionalstrengtheningandmarketexposure.TheEuropeanChamberofCommerceofthe

Philippines (ECCP) created and managed the CFIF website, www.furniturecebu.com. The

German government through its technical consultants from Center for International Migration

(CIM)andGermanDevelopmentServices(DED),launchedtheDualTrainingSystem(DTS)on

Furniture and Cabinet Making, a oneyear course on furniture making for operators and

supervisorsaccreditedbytheTechnicalEducationandSkillsDevelopment(TESDA).TheCarl

DuisbergFoundation(CDG),CenterforPromotionofImportsfromDevelopingCountries(CBI)

of the Netherlands, Private Enterprise Accelerated Resource Linkage (Pearl 1 and Pearl 2) of

CIDA,ASEANCenter, andJapanExport TradeOrganization(JETRO) fundedstudyandtrade

missions.

TheConfederationofPhilippineExporters(PHILEXPORT)hasjoinedCFIFinadvocacy

issuesonmattersaffectingthewholeexportsector.RegardinganissueonGiantAfricanSnails,

PHILEXPORTlobbiedfortheresumptionofacceptingshipmentsfromCebutoAustralia.CFIF

advocated making the Cebu International Port ISPScompliant by July 1, 2004. In response to

another issue, this time about toluene, the CFIF crafted two position papers for the immediate

release of detained containers by the Bureau of Customs and the decentralization of the

issuanceofPDEAlicenses,permits,andcertificationsfromManilatoitsregionalofficeinCebu.

AbusinessfriendlyMandaueCitygovernmenthasmadepossibletheemergenceofthe

Cebu Furniture Cluster. The local government processes business permits within a day, and

has allocated some 9,000 m

2

of its cityowned lot in the North Reclamation Area to house the

proposedCebuInternationalTradeandExhibitionCenter(CITEC).TheCITECTaskForcewas

organized in 2002, with members coming from the CFIF, Cebu Chamber of Commerce and

Industry (CCCI), PHILEXPORTCebu, the European Chamber of Commerce, DOST, and DTI.

TheJapanInternationalCooperationAgency(JICA)istheproposedfundingagency.CITECis

expectedtobenefit265,619SMEsbyprovidingavenuefortrainings,meetings,conferences,and

exhibitions.

The DTI has designated furniture as the product representative of Cebu in its one

product, one province campaign.

2

Company C claims that the DTI has announced the

availability of P300 million credit assistance to SMEs in the next two years based on buyers

purchaseorders.

On a related note, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR)

encouragedmandatoryselfmonitoringandcompliancewithenvironmentalstandardsthrough

the Environmental Consent Agreement. CFIF partnered with LGUs and private organizations

inthereforestationofCebusdenudedwatershedsandtherehabilitationofmangroveareasin

OlangoIsland.

2

DTI serves as the conduit for the industry to link with tradeaffiliated agencies such as Center for

InternationalTradeExpositionsandMissions(CITEM)andtheProductDevelopmentandDesignCenter

of the Philippines (PDDCP), as well as other government agencies (e.g. Furniture and Handicrafts

IndustriesResearchDevelopmentProgram(FHIRDP)oftheForestProductsResearchandDevelopment

Institute(FPRDI)oftheDepartmentofScienceandTechnology(DOST).)

The linkage with Don Bosco Technical School assures a constant supply of skilled

manpowertothefurnitureindustry.Presently,DonBoscooffersaBSinIndustrialTechnology,

major in Furniture Making. CFIF was involved in curriculum development and admission

applicationsforthecourse.CFIFalsocollaborateswiththeUniversityofthePhilippinesCebu

Campus in offering Summer Module Courses on Industrial Design. The CFIF is likewise

working with TESDA in promoting work in the industry as a career for skilled, vocational

workers. In this regard, the Cebu furniture sector can focus on developing subcontractors,

which are mostly unregistered, backyard industries. CFIF estimates that 92% of the jobs in the

furnitureindustryareoutsourcedtosubcontractors,makingthemanimportantalbeitneglected

industrialpartner.

IV.GLOBALBUYERSANDUPGRADING

Most industrial clusters in developing countries operate in a buyerdriven value

chain,i.e.,thebuyerexercisescontroloverthechainintheabsenceofownership(Gereffi,1999;

Humphrey &Schmitz, 2002). In the Cebu furniture cluster, foreign buyers or their buying

agentsarethemainsourceofinformationforentrepreneurs.Entrepreneursmeettheirforeign

buyers through participation in furniture exhibits, through wordofmouth, references,

advertisements, the Internet or intermediary organizations like CFIF or the Cebu Chamber of

Commerce.

Though the Cebu furniture cluster is widely seen as buyerdriven, furniture exporters

arenowexploringoriginaldesignmanufacturing(ODM)andhopingtoeventuallyventureinto

original brand manufacturing (OBM). Mixedmedia furniture, in particular, has become the

conduit for this functional upgrading. Toward this end, the CFIF started a Product

Development Program for FurnitureContemporary Design to assist local furniture