Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Abelard and Moore

Transféré par

lancekim21Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Abelard and Moore

Transféré par

lancekim21Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Moore's Moral Philosophy

First published Wed Jan 26, 2005; substantive revision Thu Mar 25, 2010

G.E. Moore's Principia Ethica of 1903 is often considered a revolutionary work that

set a new agenda for 20

th

-century ethics. This historical view is hard to sustain,

however. In metaethics Moore's non-naturalist position was close to that defended by

Henry Sidgwick and other late 19

th

-century philosophers such as Hastings Rashdall,

Franz Brentano, and J.M.E. McTaggart; in normative ethics his ideal

consequentialism likewise echoed views of Rashdall, Brentano, and McTaggart.

But Principia Ethica presented its views with unusual vigor and force. In particular, it

made much more of the alleged errors of metaethical naturalism than Sidgwick or

Rashdall had, saying they vitiated most previous moral philosophy. For this reason,

Moore's work had a disproportionate influence on 20

th

-century moral philosophy and

remains the best-known expression of a general approach to ethics also shared with

later writers such as H.A. Prichard, W.D. Ross, and C.D. Broad.

1. Non-naturalism and the Open-Question Argument

2. Metaethical Innovations

3. Impersonal Consequentialism

4. The Ideal

5. Influence

Bibliography

Other Internet Resources

Related Entries

1. Non-naturalism and the Open-Question Argument

Moore's non-naturalism comprised two main theses. One was the realist thesis that

moral and more generally normative judgements like many of his contemporaries,

Moore did not distinguish the two are objectively true or false. The other was the

autonomy-of-ethics thesis that moral judgements are sui generis, neither reducible to

nor derivable from non-moral, that is, scientific or metaphysical judgements. It

follows that our knowledge of moral truths is intuitive, in the sense that it is not

arrived at by inference from non-moral truths but rests on our recognizing certain

moral propositions as self-evident.

Moore expressed the realist side of his non-naturalism by saying that fundamental

moral judgements ascribe the property of goodness to states of affairs. Like others of

his time, he seems to have taken this realism for granted; he certainly did not defend it

extensively against anti-realist alternatives. In this he was doubtless influenced by the

grammar of moral judgements, which have a standard subject-predicate form. But it

may also be relevant that, at least early on, the only subjectivist view he seems to have

been aware of was the naturalist one according to which to say x is good is to report

the psychological fact that one approves of x. In his 1912 book Ethics he showed that

this view does not allow for moral disagreements, since my report that I approve

of x and your report that you disapprove of it can both be true (Ethics 5861). Late in

life he encountered the non-cognitivist emotivism of C.L. Stevenson, which says that

moral judgements express rather than report feelings and therefore can conflict. He

initially conceded that this anti-realist view had as good a claim as his own to be true

(A Reply to My Critics 54445), but shortly after reverted to his earlier non-

naturalism, saying he could not imagine what had induced him to consider

abandoning it (Ewing, G.E. Moore 251).

Especially in Principia Ethica, Moore spent much more time defending his other non-

naturalist thesis, of the autonomy of ethics, which he expressed by saying the property

of goodness is simple and unanalyzable, and in particular is unanalyzable in non-

moral terms. This meant the property is non-natural, which means that it is distinct

from any of the natural properties studied by science. Views that denied this

committed what he dubbed the naturalistic fallacy, which he found in hedonists

such as Jeremy Bentham, evolutionary ethicists such as Herbert Spencer, and

metaphysical ethicists such as T.H. Green. Moore's main argument against their view

was what has come to be known as the open-question argument. Consider a

particular naturalist claim, such as that x is good is equivalent to x is pleasure. If

this claim were true, Moore said, the judgement Pleasure is good would be

equivalent to Pleasure is pleasure, yet surely someone who asserts the former means

to express more than that uninformative tautology. The same argument can be

mounted against any other naturalist proposal: even if we have determined that

something is what we desire to desire or is more evolved, the question whether it is

good remains open, in the sense that it is not settled by the meaning of the word

good. We can ask whether what we desire to desire is good, and likewise for what is

more evolved, more unified, or whatever (Principia Ethica6269). Sidgwick had used

the same argument against Bentham and Spencer, but only in passing; Moore made it

central to his metaethics.

The open-question argument was much discussed in the 20

th

century and met with

many objections. One said the argument's persuasiveness depends on the paradox of

analysis: that any definition of a concept will, if successful, appear uninformative. If

an analysis does capture all its target concept's content, the sentence linking the two

will be a tautology; but this is hardly a reason to reject all analyses. Moore could

respond that in other cases accepting a definition leads us to see that the sentence

affirming it, while seeming informative, in fact is not. But this does not happen in the

case of good Even if we agree that only pleasure is good, no amount of reflection

will make us think Pleasure is good equivalent to Pleasure is pleasure. Another

objection, made later in the century, said the argument cannot support Moore's

conclusions about the distinctness of goodness as a property. Science, the objection

runs, uncovers many non-analytic property identities; for example, water is identical

to H

2

O even though the terms water and H

2

O are not synonymous. By analogy,

the property of goodness could be identical to that of pleasure even if good and

pleasure have different meanings. Again, however, Moore could respond. The

property of being water is that of having the underlying structure, whatever that is, of

the stuff found in lakes, rivers, and so on; when this structure turns out to be H

2

O, the

latter property fills a gap in the former and makes the two identical. But this

explanation does not extend to the case of goodness, which is not a higher-level

property with any gap needing filling: to be good is not to have whatever other

property plays some functional role. If goodness is analytically distinct from all

natural properties, it is metaphysically distinct as well. It is worth noting, however,

that Moore did not explain the open-question argument in the way later non-

cognitivists would. Following Hume, they said that moral judgements are intrinsically

motivating, so sincerely accepting x is good requires a commitment or at least some

motivation to pursue x if that is possible. But then no definition of good in purely

natural terms can ever succeed, since it cannot capture the term's action-guiding force;

nor can an evaluative conclusion be validly inferred from premises none of which

have such force. Whatever the merits of this Humean explanation, Moore did not give

it. On the contrary, the question whether moral judgements are intrinsically

motivating is not one on which he expressed clear views or apparently thought very

important.

2. Metaethical Innovations

The main elements of Moore's non-naturalism moral realism and the autonomy of

ethics had been defended earlier by Sidgwick and were well known when Moore

wrote. But Moore did add two innovations. One was his view that the fundamental

moral concept is that of goodness, which he expressed by saying that goodness is

simple and unanalyzable, even in moral terms. This had not been Sidgwick's view.

For him the central moral concept had been ought, and he defined good in terms of

ought, more specifically, as what one ought to desire. Principia Ethica took the

exactly opposite view, defining ought in terms of good, so one ought to do x

literally means x will produce the most good possible (7677, 19698). Moore was

quickly persuaded by Bertrand Russell that this last view is vulnerable to his own

open-question argument: in saying one ought to do what will produce the most good

we do not mean what will produce the most good will produce the most good. In

later work he therefore held that ought is a distinct moral property from good, and in

an uncompleted Preface to a planned second edition of Principia Ethica allowed that

it would not affect the essence of his non-naturalism if good were defined in moral

terms, say, as what one ought to desire. But he continued to prefer the view that good

is a simple concept, and there was vigorous debate on this topic in years to come, with

Brentano, Broad, and A.C. Ewing defending reductive analyses similar to Sidgwick's

while Ross held a non-reductive view like Moore's. On the Moorean view judgements

about the goodness of states of affairs are not shorthand for judgements about how we

ought to respond to those states; they are independent judgements that explain why we

ought so to respond.

Moore's second innovation was his view that the intrinsic value of a state of affairs

can depend only on its intrinsic properties, properties it has apart from any relations to

other states. Earlier writers had distinguished between goodness as an end, which they

also called intrinsic or ultimate goodness, and goodness as a means, saying the former

cannot rest just on a state's causally producing goods outside itself. But they seemed

to allow that goodness as an end can depend on other relational properties; thus they

talked as if a belief's being true, which is necessary for its being knowledge, can

increase its value, while a pleasure's being that of a bad person can make it worse.

Moore did not explicitly state his more restrictive view that intrinsic goodness can

depend only on intrinsic properties until The Conception of Intrinsic Value of 1922,

but it nonetheless guided Principia Ethica at two points. One was that book's specific

formulation of the principle of organic unities, to be discussed below. The other was

its testing for a state's intrinsic value by the method of isolation, which involves

asking whether a universe containing only that state and no other would be good

(Principia Ethica 142, 14547, 236, 256); the point of this method was precisely to

insulate judgements of intrinsic value from facts about a state's external relations.

Moore's strict view was adopted by some later writers such as Ross, while others

argued that a better theory of value results if intrinsic goodness can depend on some

relations. But Moore was the first to raise this issue clearly.

These two innovations, though not trivial, do not affect the core of a non-naturalist

metaethics. But some critics charge that Moore did change that view fundamentally,

and for the worse. They say that Sidgwick's non-naturalism was comparatively

modest, holding only that there are truths about what people ought or have reason to

do that we can know by reflection. But Moore, the objection runs, supplemented this

modest view with an extravagant metaphysics of non-natural properties inhabiting a

supersensible realm and a mysterious faculty of intuition that acquaints us with them.

These additions opened non-naturalism to entirely avoidable objections and so led to

its early demise.

These charges are hard to sustain, however. Principia Ethica actually downplayed the

metaphysical side of its non-naturalism, saying that goodness has being but does not

exist, as numbers do not exist, and in particular does not exist in any supersensible

reality (16163, 17476). Nor did its explicit talk of properties mark a significant

departure from Sidgwick: surely if the latter thought people ought to pursue pleasure,

he thought pleasure has the property of being something people ought to pursue.

Moore was similarly modest in his epistemology, saying several times, as Sidgwick

also had, that by calling our knowledge of basic moral truths intuitive he means

only that it was not derived by inference from other knowledge; he likewise denied

that moral intuition was infallible, saying that in whatever way we can cognize a true

proposition, we can cognize a false one (Principia Ethica 36, 193). Moore did

sometimes make bald assertions of self-evidence, as in his claim in Ethics that it is

self-evident that the right is always what most promotes the good (112), and some

critics have found this baldness troubling. But the contrast with earlier non-naturalists

such as Sidgwick should again not be overdrawn. It is arguable that Sidgwick, too,

gave most weight to intuitions about abstract moral principles like those Moore cited

in Ethics, citing more concrete judgements only in ad hominem arguments against

opponents. And Moore often argued in more complex ways. In Principia Ethica he

defended his claim that beauty on its own is good by appealing to intuitions about a

very specific beautiful world, and criticized the view that only pleasure is good by

arguing that it conflicts with other things we believe (13247). Moore likewise

insisted that before we make judgements of self-evidence we must make sure the

propositions we are considering are clear; failure to do so, he claimed, explained

much of the disagreement about ethics. And he took note of common opinions to the

extent of trying to explain away divergent views when he found them. Overall his

approach to establishing moral truths was very similar to Sidgwick's, appealing to

intuitive judgements that can be made at different levels of generality and that must be

brought into a coherent whole. This is not to say that his non-naturalism was beyond

objection. Any such view holds that there are truths independent of natural and logical

ones and knowable by some non-empirical means, and many find this pair of claims

unacceptable. But Moore's version of the view was arguably no more objectionable

than others. If Sidgwick's non-naturalism did not involve a problematic metaphysics

and epistemology, neither did Moore's; if Moore's was hopelessly extravagant, so was

a supposedly more modest one like Sidgwick's.

A final important feature of Moore's metaethics was its reductionism about normative

concepts. Like Sidgwick, the Moore of Principia Ethica held that there was just one

basic normative concept, though he thought it was good rather than ought; like Ross,

the later Moore held that there were just two. But this conceptual reductionism, which

was common throughout the period from Sidgwick to Ross, contrasts sharply with the

multitude of concepts recognized in much present-day ethics. First, Moore and his

contemporaries took as basic only the thin concepts good and ought rather than

thick concepts such as courage and generosity; the latter, they held, combined a thin

concept with some more or less determinate descriptive content. They were also

reductive about the thin concepts. They did not distinguish between moral oughts and

prudential or rational ones, holding that there is only the single, moral ought; this is

why for them egoism was a moral view, not a challenge to morality from outside it.

Nor did they recognize different types of value. For them goodness was a property

only of states of affairs and not, as Kantians hold, of persons and other objects. They

likewise did not accept the late 20

th

-century idea that there is a distinct concept of

well-being, or of what is good for a person; instead, they defined a person's good

as what is simply good and located in his life. Nor did they distinguish between moral

and non-moral goodness, holding that the former is just ordinary goodness when

possessed by certain objects, such as traits of character. The result was that all

normative judgements could be expressed using the two concepts good and ought,

which were therefore the only ones one needed. To some this conclusion will mean

that Moore and his contemporaries ignored important conceptual distinctions; to

others it will mean they avoided tedious conceptual debates. But it did free them to

discuss substantive questions about what is in fact good and right. On this topic

Moore's views, though not entirely novel, were again strikingly stated.

3. Impersonal Consequentialism

Moore's normative view again comprised two main theses. One was impersonal

consequentialism, the view that what is right is always what produces the greatest

total good impartially considered, or counting all people's good equally. The other

was the ideal or perfectionist thesis that what is good is not only or primarily pleasure

or desire-satisfaction, but certain states whose value is independent of people's

attitudes to them. Moore recognized several such states, but in Principia Ethica said

famously that by far the most valuable thingsare certain states of consciousness,

which may roughly be described as the pleasures of human intercourse and the

enjoyment of beautiful objects (237). According to his ideal consequentialism, what

is right is in large part what most promotes loving personal relationships and aesthetic

appreciation by all persons everywhere.

Principia Ethica took the consequentialist part of this view to be analytically true,

since it defined the right as what most promotes the good. But once Moore abandoned

this definition, he had to treat the consequentialist principle as synthetic and did so

in Ethics, which allowed that deontological views which say some acts that maximize

the good are wrong are perfectly coherent. But even there he did not argue at length

for consequentialism, simply announcing that it is self-evident (112). This in part

reflected common assumptions of his time, when a majority of philosophers accepted

some consequentialist structure. But it may also be relevant that the only alternative

he considered in Ethics was an absolute deontology like Kant's, according to which

some acts such as killing and lying are wrong no matter what their consequences. His

major ethical works did not consider a moderate deontology such as would later be

developed by Ross, in which deontological prohibitions of killing and lying often

outweigh considerations of good consequences but can themselves be outweighed if

enough good is at stake. It is not clear what Moore's response to such a moderate

deontology would have been.

Principia Ethica also took the impartialism of its view to be analytic, and in particular

claimed that egoism, which says that each person should pursue only his own good, is

self-contradictory. (Despite his interest in personal love, Moore never considered the

intermediate view that Broad would call self-referential altruism, according to which

each person should care more about the good of those close to him, such as his family

and friends.) Sidgwick had argued that if an egoist confines himself to saying that

each person's pleasure is good from that person's point of view, he cannot be argued

out of his position. But Moore said this concept of agent-relative goodness is

unintelligible (Principia Ethica 14853), and that conclusion does follow from his

view that goodness is simple and unanalyzable. If goodness is a simple property, how

can a state such as person A's pleasure have it from one point of view but not another?

(Compare squareness. An object cannot be square from one point of view but not

from another; it either is square or not.) All that can be meant by talk of the good

for a person is what is simply good and located in him; and simple goodness gives

everyone equally reason to pursue it. In Ethics Moore abandoned this argument,

saying that egoism cannot be proven false by any argument, even though he thought

its falsity was self-evident (99100). But it is not clear how he could make this

concession if he still held that goodness is a simple property. Perhaps he was tacitly

allowing, as he would in the draft Preface to Principia Ethica, that it would not

centrally damage his position if good were analyzed in terms of ought, as it had been

by Sidgwick. There is no contradiction in saying that what each person ought to desire

is different, say, just his own pleasure. But if all oughts derive from a simple property

of goodness, as Moore always preferred to hold, then all oughts must be impartial.

In applying this view, Moore gave it the form of what today is called indirect or

two-level consequentialism. In deciding how to act, people are not to assess

individual acts for their specific consequences; instead, they should follow certain

general moral rules such as Do not kill and Keep promises, which are such that

adhering to them will most promote the good over time. This policy will sometimes

mean not performing the act with the best individual outcome, but given our human

propensity to error its consequences will be better in the long run than trying to assess

acts one by one. This indirect consequentialism had again been defended earlier, by

Sidgwick and even John Stuart Mill, but Moore gave it a more conservative form,

urging adherence to the rules even in the face of apparently compelling evidence that

breaking them now would be optimific. Principia Ethica made the surprising claim

that the relevant rules would the same given any commonly accepted theory of the

good, for example, given either hedonism or its own ideal theory (207). This claim of

extensional equivalence for different consequentialist views was not new; T.H. Green,

F.H. Bradley, and McTaggart had all suggested that hedonism and ideal

consequentialism have the same practical implications. But Moore was surely

expressing the more plausible view when in Ethics he doubted that pleasure and ideal

values always go together (145). And even when he accepted the equivalence claim,

he remained intensely interested in what he called the primary ethical question of

what is good in itself (Principia Ethica 207; see also 78, 128). Like Green, Bradley,

and McTaggart, he thought the central philosophical question was

what explained why good things are good, i.e., which of their properties made them

good. That was the subject of his most brilliant piece of ethical writing, Chapter 6

of Principia Ethica on The Ideal.

4. The Ideal

One of this chapter's larger aims was to defend value-pluralism, the idea that there are

many ultimate goods. Moore thought a key bar to this view was the naturalistic

fallacy. He assumed, plausibly, that philosophers who treat goodness as identical to

some natural property will usually make this a simple property, such as just pleasure

or just evolutionary fitness, rather than a disjunctive property such as pleasure-or-

evolutionary-fitness-or-knowledge. But then any naturalist view pushes us toward

value-monism, or the view that only one state is good. Once naturalism is dropped,

however, we can see what Moore thought self-evident: that there are irreducibly many

goods. Another bar to value-pluralism was excessive demands for unity or system in

ethics. Sidgwick had used such demands to argue that only pleasure can be good,

since no theory with a plurality of ultimate values can justify a determinate scheme for

weighing them against each other. But Moore, agreeing here with Rashdall, Ross, and

others, said that to search for unity and system, at the expense of truth, is not, I

take it, the proper business of philosophy (Principia Ethica 270). If intuition reveals

a plurality of ultimate goods, then an adequate theory must recognize that plurality.

According to a famous part of Principia Ethica one of those goods is the existence of

beauty. Arguing against Sidgwick's view that all goods must be states of

consciousness, Moore asked readers to imagine a beautiful world with no minds in it:

is this world's existence not better than that of a horribly ugly world (13536)? In

answering yes, he anticipated some present-day environmental ethics, which likewise

holds that there can be value in features of the natural environment apart from any

awareness of them. But he did not insist on this view. Later in Principia Ethica he

said that beauty on its own at most has little and may have no value, and in Ethics he

denied that beauty on its own has value. There he held, with Sidgwick, that all

intrinsic goods involve some state of consciousness (10304, 148, 153). But he

continued to hold that the existence of beauty that actually exists and causes the

appreciation is better than an otherwise similar appreciation of beauty that does not

exist.

Moore also gave some weight to the hedonic states of pleasure and pain. He thought

the former a very minor good, saying that pleasure on its own at most has limited and

may have no value. But pain was a very great evil, which there was a serious duty to

prevent (Principia Ethica 26061, 27071). His view therefore involved an

asymmetry, with pain a much greater evil than pleasure was a good. This had not been

the traditional view; most hedonists had held that a pleasure of a given intensity was

exactly as good as a pain of the same intensity was evil. But Moore thought it

intuitively compelling that the pain was worse; if that made the theory of value less

systematic, so much the worse for system.

While many ideal consequentialists treated knowledge as intrinsically good, in some

cases supremely so, Principia Ethica did not, claiming that knowledge is a necessary

component of the larger good of appreciating existing beauty but has little or no value

in itself (24748). Again Ethics may have reversed this view, citing knowledge

several times as one ideal good that may be added to the hedonist's good of pleasure

(34, 14647). But Moore never saw any intrinsic value in achievement, for example in

business or politics, or indeed in any active changing of the world. As John Maynard

Keynes said, his chief goods were states of mind that were not associated with action

or achievement or with consequence. They consisted in timeless, passionate states of

contemplation and communion, largely unattached to before and after (Keynes,

My Early Beliefs, 83).

The first of these goods was the appreciation of beauty, which for Moore combined

the cognition of beautiful qualities with an appropriately positive emotion toward

them, such as enjoyment or admiration. We listen to music, say, hear beautiful

qualities in it, and love those qualities. But the value here was entirely contemplative;

Moore saw no separate worth in what the romantics had especially valued, the active

creation of beauty. Moore might claim that an artist must understand and love his

work's beauty if he is to create it, perhaps even more than someone who merely

enjoys it; but the value in the artist's work is still not distinctively creative. In

characterizing the good of aesthetic contemplation Moore gave a further reductive

analysis, this time of beauty as that the admiring contemplation of which is good in

itself (Principia Ethica 24950). Beauty, too, was not a distinct normative concept

but analyzable in terms of goodness. He did not notice, however, that this definition

again seemed to open him to an open-question argument, since it reduced the claim

that it is good to contemplate beauty to the tautology that it is good to contemplate

what it is good to contemplate.

Though Moore in Principia thought beauty good in itself, he did not insist on this

view when valuing the appreciation of beauty; the latter might be good even if the

former was not. But he still thought the existence of beauty makes a significant

difference to value. More specifically, he thought the admiring contemplation of

beauty that actually exists and causes one's contemplation is better than an otherwise

similar contemplation of merely imaginary beauty, and better by more than can be

attributed to the existence of the beauty on its own. This view involved an application

of his principle of organic unities, according to which the value of a whole need not

equal the sum of the values its parts would have on their own (Principia Ethica 78

80). If state x on its own has value a, and state y on its own has value b, the whole

combining them need not have value a + b; it may have more or less. This principle

had been accepted by Idealists such as Bradley, who gave it a characteristically anti-

theoretical formulation. They said that if x and y combine to form the whole x-plus-y,

their values, like their very identities, are dissolved in that larger whole, whose value

cannot be computed from that of its parts. It was Moore's contribution to accept the

principle in a way that rejected this anti-theoretical stance and allowed computation,

though exactly how it did depended on his view that a state's intrinsic value can

depend only on its intrinsic properties.

This strict view implies that when x and y enter into the relations that constitute the

whole x-plus-y, their own values cannot be changed by those relations. Moore

recognized this, saying, The part of a valuable whole retains exactly the same value

when it is, as when it is not, a part of that whole (Principia Ethica 81). Any

additional value in the whole x-plus-y must therefore be attributed to it as a distinct

entity from its parts, and with the relations between those parts internal to it. Moore

called this additional value the value of a whole as a whole, and said it needed to be

added to the value in the parts to arrive at the whole's value on the whole 0

(Principia Ethica 26364). Thus, if x and y have values a and b on their own, and x-

plus-y has value c as a whole, the value of x-plus-y on the whole is a + b + c. (The

value of the whole is therefore not equal to the sum of the values of its parts, but is

equal to a sum of which those values are constituents.) This holistic formulation of

the principle of organic unities is not the only possible one. One could relax the

conditions on intrinsic value so it can be affected by external relations, and say that

when x and y enter into a whole their own values change, so that, say, x's value

becomes a + c. This variability formulation can always reach the same final

conclusions as the holistic one, since whatever positive or negative value the latter

finds in the whole as a whole the former can add to one of the parts. But the two

formulations locate the additional value in different places, and sometimes one and

sometimes the other gives the intuitively better explanation of an organic value.

Moore, however, was forced by his strict view of intrinsic goodness to use only the

holistic formulation. In the aesthetic case, he held that the admiring contemplation of

beauty considered apart from the existence of its object always has the same

(moderate) value a, while the existence of beauty always has the same (minimal)

value b. But when the two are combined so a person admiringly contemplates beauty

that exists and causes his contemplation, the resulting whole has the significant

additional value c as a whole. The existence of the beauty is therefore necessary for

the significant value c, but that value is not intrinsic to it, belonging instead to the

larger whole of which it is part.

Moore made several other uses of the principle of organic unities, including in

response to an argument of Sidgwick's for hedonism. Sidgwick had claimed that there

would be no value in a world without consciousness and, more specifically, pleasure,

and had concluded that therefore pleasure is the only good. Given Principia Ethica's

view about the value of beauty, Moore rejected the premise of Sidgwick's argument,

but he also argued that, even granting that premise, Sidgwick's conclusion does not

follow. It might be that pleasure is a necessary condition for any value, but that once

pleasure is present, other states such as the awareness of beauty or love increase the

value of the resulting whole even though alone they have no worth (Principia

Ethica 14445). And of course this was precisely Moore's later view. Another

application of the principle was in explicating claims about desert. Moore endorsed

the retributive view that when a person is morally vicious it is good if he is punished,

and he expressed this view by saying that although the person's vice is bad and his

suffering pain is bad, the combination of vice and pain in the same life is good as a

whole, and sufficiently so to make the situation on the whole better than if there were

vice and no pain (Principia Ethica26364). This is in fact a point where Moore's

holistic formulation of the principle is especially appealing. The alternative variability

view must say that when a person is vicious, his suffering pain switches from being

purely bad to purely good. But this implies that the morally appropriate response to

deserved suffering is simple pleasure, which does not seem right; the better response

mixes satisfaction that justice is being done with pain at the infliction of pain, as

Moore's view implies.

Moore's other chief good of personal love also involved admiring contemplation, but

now of objects that are not just beautiful but also intrinsically good (Principia

Ethica 251). Since for Moore the main intrinsic goods were mental qualities, such

love involved primarily the admiring contemplation of another's good states of mind.

In so characterizing love Moore was applying one of four recursive principles he used

to generate higher-level intrinsic goods and evils from an initial set of such goods and

evils. The first such principle says that if state x is intrinsically good, admiringly

contemplating, or loving, x for itself is also intrinsically good. Thus, if person A's

admiringly contemplating beauty is good, person B's admiringly contemplating A's

admiration is a further good, as is C's admiration of B's admiration, and so on. A

second principle says that if x is intrinsically evil, hating x for itself is intrinsically

good; thus, B's feeling compassionate pain at A's pain is good. And two final

principles say that loving for itself what is evil, as in sadistic pleasure in another's

pain, and hating for itself what is good, as in envious pain at his pleasure, are evil.

Though Moore stated these four principles separately, they all make morally

appropriate attitudes to intrinsic goods and evils further goods and morally

inappropriate attitudes further evils. The principles were by no means unique to

Moore; they had been defended earlier by Rashdall and Brentano and would be

defended later by Ross. But Moore's formulation was in one respect distinctive.

Rashdall and Ross called the higher-level values they generated virtues and vices, as

indeed it is plausible to do; surely benevolence and compassion are virtuous and

sadism vicious. But Moore defined the virtues instrumentally, as traits that cause

goods and prevent evils, and said that as such they lacked intrinsic worth (Principia

Ethica 22026).

The recursive principles are clearly relevant to personal love, which centrally involves

concern for another's good. But Moore's particular application of the principles led to

a curiously restricted picture of love. First, as in the aesthetic case, he took the main

valuable attitude to be contemplative, involving the admiration of another's already

existing good qualities rather than any active engagement with them. This applied

even to the love of another's physical beauty. Though he did think this a crucial part of

love, he took it to involve mere passive admiration of another's beauty, as it were from

the other side of the room. There was no desire to possess or interact physically with

her beauty, that is, no active eroticism. And the same point applied more generally:

the loving attitude was one of appreciating goods in another's life rather than acting to

produce or help her achieve them. One did not do anything for or with a loved one;

one simply admired. Moreover, the list of admired goods was seriously truncated. It

did not include pleasure or happiness, since that was not a significant good, nor even

knowledge or achievement. Instead, it centered on another's admiring contemplation

of beauty, as if the supreme expression of love were What fine taste in music you

have. Finally, Moore took the qualities one admired in a loved one to be simply and

therefore impartially good. But this meant his account had no room for the special

attachments many take to be central to personal love. If I love a friend for

qualities x, y, and z, and a stranger comes along with the same qualities to a higher

degree, then on Moore's theory I should love the stranger more. This is not to say that

a more adequate account of love cannot be constructed with the same basic structure

as Moore's; it can. It will hold that personal love involves a wider range of positive

attitudes, including actively promoting as well as contemplating, to a wider range of

goods, including happiness, knowledge, and achievement, and where those goods in a

loved one's life have greater value from a lover's point of view than do similar states

of strangers. But Moore was prevented from giving this account by other features of

his view: his general emphasis on contemplative forms of love, his restricted list of

initial intrinsic goods, and his strict impartialism about value.

5. Influence

Despite not containing many large new ideas, Moore's ethical writings, and

especially Principia Ethica, were extremely influential, both outside and within

philosophy. Outside philosophy their main influence was through the literary and

artistic figures in the Bloomsbury Group, such as Keynes, Lytton Strachey, and

Leonard and Virginia Woolf, several of whom had come under Moore's influence

while members with him of the Apostles society at Cambridge. They were most

impressed by the last chapter of Principia Ethica, whose identification of aesthetic

appreciation and personal love as the highest goods very much fit their predilections.

Many of them the gay men in particular sexualized Moore's account of love,

adding an erotic element not present in his formulations. And by their own later

admission, they tended to ignore the impartial consequentialism within which Moore

embedded those goods, and so concentrated on pursuing them in their own lives rather

than encouraging their wider spread in society. Also important for Principia Ethica's

extra-philosophical appeal was its brash iconoclasm, its claiming, however,

inaccurately, to sweep away all past moral philosophy. This tone entirely fit its time,

when the death of Victoria had led many in Britain to think a new, more progressive

age was beginning.

The book's influence within philosophy was even greater. On the normative side,

views close to its ideal consequentialism remained prominent and even dominant

through the 1930s, though it is hard to know how far this is attributable to Moore,

since similar views had been widely accepted before him. In metaethics his non-

naturalism likewise remained dominant for several decades, though here Moore

played a larger role, especially for later generations, because of the vigor with which

he presented the view. He said more about its metaphysics than predecessors such as

Sidgwick had, if only by making explicit its commitment to non-natural properties.

And he defended it more extensively, by placing more weight on the open-question

argument. When Sidgwick had noticed Bentham or Spencer equating goodness with a

natural property such as pleasure, he thought it a minor slip that in charity should be

ignored; Moore thought it vitiated the philosopher's entire system. By so emphasizing

the two elements of non-naturalism its realism and commitment to the autonomy of

ethics Moore helped initiate a sequence of developments in 20

th

-century

metaethics.

The first reaction to non-naturalism, other than simple acceptance, came from

philosophers who accepted the autonomy of ethics but, often under the influence of

logical positivism, rejected its moral realism, holding that there are no facts other than

natural facts and no modes of knowing other than the empirical and the strictly

logical. They therefore developed various versions of non-cognitivism, which hold

that moral judgements are not true or false but express attitudes (emotivism) or issue

something like imperatives (prescriptivism). These views allow for moral

disagreement, since attitudes and imperatives can oppose each other. They also, their

proponents claimed, give a better explanation of the open-question argument, since

they find a distinctive emotive or action-guiding force in moral concepts and

judgements that is not present in non-moral ones. Non-cognitivism can also explain

why morality matters to us as it does. Non-naturalism implies that moral judgements

concern a mysterious type of property, but why should facts about that property be

important to us or influence our behavior? If such judgements express deep-seated

attitudes, the question answers itself.

A still later generation turned against non-cognitivism, in part for flouting the

grammar of moral judgements and our natural response to them, both of which

suggest realism, but also for a reason shared with non-naturalism. When Moore and

the other non-naturalists defended substantive moral judgements, they often said

baldly that the judgements were self-evident, so anyone who denied them was morally

blind. To the later generation this was unacceptably dogmatic, and the failing was

even more plainly present in non-cognitivism, which pictured moral debate as the

mere venting of emotions or issuing of commands. These philosophers therefore

sought an account of ethics that would better allow for rational moral discussion.

While many alternatives were canvassed, one that came to prominence in the late

1950s was a neo-Aristotelian view according to which, if it is true that one ought, say,

to relieve others' pain, this is because doing so will contribute to one's own flourishing

as a human being. Since such flourishing was to be understood in terms of humans'

biological nature, this view at least implicitly challenged the autonomy of ethics.

Many of its partisans also rejected the calculating side of Moore's consequentialism,

which identified right acts by adding up the goods and evils in their effects. Moral

principles, they said, cannot be codified or theorized in that way. And even

philosophers who did accept calculation tended to reject Moore's ideal

consequentialist values as unacceptably extravagant; if right acts promoted goods,

those had to be less contentious and more empirically measurable ones such as

preference-satisfaction. By the 1960s, it seems fair to say, Moore's moral philosophy

was about as dead as it is possible to be. It was still important to read Principia

Ethica, as having started the sequence of developments that led to the current views,

but from the standpoint of those views Moore's approach to ethics was hopelessly

mistaken.

Forty years later the situation is more favorable to Moore. A growing body of

philosophers now defend non-naturalism, some claiming to do so with less ontological

extravagance than Moore, but all embracing some account of moral truth that

separates it from scientific truth. In normative ethics, too, there is increasing sympathy

for accounts of the good with an ideal or perfectionist content, and admiration for

particular features of Moore's view, such as his valuing of personal love and his

principle of organic unities. Even Moore's style of defending moral claims, which so

outraged philosophers of the 1950s and 1960s, is in effect the standard style of

contemporary normative ethics, though it tends to take a more complex and

circumspect form. Whereas Moore sometimes claimed that certain moral propositions

are self-evident when considered on their own, philosophers today are more likely to

give coherence arguments, appealing to intuitive judgements at different levels of

generality and if possible on different topics, to arrive at an overall position with

intuitive support at many points. But the basis of this more complex procedure, which

Moore also sometimes used, is essentially the same appeal to intuitive moral

judgements. And it is possible to see it as, not arrogant, but philosophically modest.

Moore and his contemporaries from Sidgwick in the 1870s to Ross in the 1930s

believed that if one asked, for example, why we should relieve others' pain, there was

no answer: we simply should. The duty to promote others' good was an underivative

one for which no deeper explanation could be given and which could only be

recognized by intuition. In taking this stance they assumed that the more grandiose

justifications offered by philosophers, such as the neo-Aristotelian argument that

benefitting others is necessary for one's own flourishing, or the Kantian argument that

maxims contrary to it cannot be universalized, can never succeed. There is no moral

philosopher's stone, or no way of escaping the need for direct moral judgement. Their

moral methodology therefore reflected a modest belief about what philosophy can

accomplish in normative ethics, as against the intuitive reflection that is also

exercised, if less systematically, by non-philosophers. This philosophical modesty

freed them to look more closely at the details of substantive moral views than

philosophers seeking grand justifications usually do and to uncover more of their

underlying structure. In this respect contemporary ethics, which has spent several

decades remaking many of their discoveries, is returning to their path. This is another

way in which, however slowly, contemporary ethics is coming back to Moore.

6. Ethics

Abelard takes the rational core of traditional Christian morality to be

radically intentionalist, based on the following principle: the agent's intention alone

determines the moral worth of an action. His main argument against the moral

relevance of consequences turns on what has been called moral luck. Suppose two

men each have the money and the intention to establish shelters for the poor, but one

is robbed before he can act whereas the second is able to carry out his intention.

According to Abelard, to think that there is a moral difference between them is to hold

that the richer men were the better they could become this is the height of

insanity! Deed-centred morality loses any kind of purchase on what might have been

the case. Likewise, it cannot offer any ground for taking the epistemic status of the

agent into account, although most people would admit that ignorance can morally

exculpate an agent. Abelard makes the point with the following example: imagine the

case of fraternal twins, brother and sister, who are separated at birth and each kept in

complete ignorance of even the existence of the other; as adults they meet, fall in love,

are legally married and have sexual intercourse. Technically this is incest, but Abelard

finds no fault in either to lay blame.

Abelard concludes that in themselves deeds are morally indifferent. The proper

subject of moral evaluation is the agent, via his or her intentions. It might be objected

that the performance or nonperformance of the deed could affect the agent's feelings,

which in turn may affect his or her intentions, so that deeds thereby have moral

relevance (at least indirectly). Abelard denies it:

For example, if someone forces a monk to lie bound in chains between two women,

and by the softness of the bed and the touch of the women beside him he is brought to

pleasure (but not to consent), who may presume to call this pleasure, which nature

makes necessary, a fault?

We are so constructed that the feeling of pleasure is inevitable in certain situations:

sexual intercourse, eating delicious food, and the like. If sexual pleasure in marriage is

not sinful, then the pleasure itself, inside or outside of marriage, is not sinful; if it is

sinful, then marriage cannot sanctify itand if the conclusion were drawn that such

acts should be performed wholly without pleasure, then Abelard declares they cannot

be done at all, and it was unreasonable (of God) to permit them only in a way in

which they cannot be performed.

On the positive side, Abelard argues that unless intentions are the key ingredient in

assessing moral value it is hard to see why coercion, in which one is forced to do

something against his or her will, should exculpate the agent; likewise for

ignorancethough Abelard points out that the important moral notion is not simply

ignorance but strictly speaking negligence. Abelard takes an extreme case to make his

point. He argues that the crucifiers of Christ were not evil in crucifying Jesus. (This

example, and others like it, got Abelard into trouble with the authorities, and it isn't

hard to see why.) Their ignorance of Christ's divine nature didn't by itself make them

evil; neither did their acting on their (false and mistaken) beliefs, in crucifying Christ.

Their non-negligent ignorance removes blame from their actions. Indeed, Abelard

argues that they would have sinned had they thought crucifying Christ was required

and did not crucify Christ: regardless of the facts of the case, failing to abide by one's

conscience in moral action renders the agent blameworthy.

There are two obvious objections to Abelard's intentionalism. First, how is it possible

to commit evil voluntarily? Second, since intentions are not accessible to anyone other

than the agent, doesn't Abelard's view entail that it is impossible to make ethical

judgements?

With regard to the first objection, Abelard has a twofold answer. First, it is clear that

we often want to perform the deed and at the same time do not want to suffer the

punishment. A man wants to have sexual intercourse with a woman, but not to commit

adultery; he would prefer it if she were unmarried. Second, it is clear that we

sometimes want what we by no means want to want: our bodies react with pleasure

and desire independently of our wills. If we act on such desires, then our action is

done of will, as Abelard calls it, though not voluntarily. There is nothing evil in

desire: there is only evil in acting on desire, and this is compatible with having

contrary desires.

With regard to the second objection, Abelard grants that other humans cannot know

the agent's intentionsGod, of course, does have access to internal mental states, and

so there can be a Final Judgement. However, Abelard does not take ethical judgement

to pose a problem. God is the only one with a right to pass judgement. Yet this fact

doesn't prevent us from enforcing canons of human justice, because, Abelard holds,

human justice has primarily an exemplary and deterrent function. In fact, Abelard

argues, it can even be just to punish an agent we strongly believe had no evil

intention. He cites two cases. First, a woman accidentally smothers her baby while

trying to keep it warm at night, and is overcome with grief. Abelard maintains that we

should punish her for the beneficial example her punishment may have on others: it

may make other poor mothers more careful not to accidentally smother their babies

while trying to keep them warm. Second, a judge may have excellent (but legally

impermissible) evidence that a witness is perjuring himself; since he cannot show that

the witness is lying, the judge is forced to rule on the basis of the witness's testimony

that the accused, whom he believes to be innocent, is guilty. Human justice may with

propriety ignore questions of intention. Since there is divine justice, ethical notions

are not an idle wheelnor should they be, even on Abelard's understanding of human

justice, since they are the means by which we determine which intentions to promote

or discourage when we punish people as examples or in order to deter others.

There is a sense, then, in which the only certifiable sin is acting against one's

conscience, unless one is morally negligent. Yet if we cannot look to the intrinsic

value of the deeds or their consequences, how do we determine which acts are

permissible or obligatory? Unless conscience has a reliable guide, Abelard's position

seems to open the floodgates to well-meaning subjectivism.

Abelard solves the problem by taking obedience to God's willthe hallmark of

morally correct behaviour, and itself an instance of natural lawto be a matter of the

agent's intention conforming to a purely formal criterion, namely the Golden Rule

(Do to others as you would be done to). This criterion can be discovered by reason

alone, without any special revelation or religious belief, and is sufficient to ensure the

rightness of the agent's intention. But the resolution of this problem immediately leads

to another problem. Even if we grant Abelard his naturalistic ethics, why should an

agent care if his or her intentions conform to the Golden Rule? In short, even if

Abelard were right about morality, why be moral?

Abelard's answer is that our happinessto which no one is indifferentis linked to

virtue, that is, to habitual morally correct behaviour. Indeed, Abelard's project in

the Collationes is to argue that reason can prove that a merely naturalistic ethics is

insufficient, and that an agent's happiness is necessarily bound up with accepting the

principles of traditional Christian belief, including the belief in God and an Afterlife.

In particular, he argues that the Afterlife is a condition to which we ought to aspire,

that it is a moral improvement even on the life of virtue in this world, and that

recognizing this is constitutive of wanting to do what God wants, that is, to live

according to the Golden Rule, which guarantees as much as anything can (pending

divine grace) our long-term postmortem happiness.

The Philosopher first argues with the Jew, who espouses a strict observance moral

theory, namely obedience to the Mosaic Law. One of the arguments the Jew offers is

the Slave's Wager (apparently the earliest-known version of Pascal's Wager). Imagine

that a Slave is told one morning by someone he doesn't know whether to trust that his

powerful and irritable Master, who is away for the day, has left instructions about

what to do in his absence. The Slave can follow the instructions or not. He reasons

that if the Master indeed left the instructions, then by following them he will be

rewarded and by not following them he will be severely punished, whereas if the

Master did not leave the instructions he would not be punished for following them,

though he might be lightly punished for not following them. (This conforms to the

standard payoff matrix for Pascal's Wager.) That is the position the Jew finds himself

in: God has apparently demanded unconditional obedience to the Mosaic Law, the

instructions left behind. The Philosopher argues that the Jew may have other choices

of action and, in any event, that there are rational grounds for thinking that ethics is

not a matter of action in conformity to law but a matter of the agent's intentions, as we

have seen above.

The Philosopher then argues with the Christian. He initially maintains that virtue

entails happiness, and hence there is no need of an Afterlife since a virtuous person

remains in the same condition whether dead or alive. The Christian, however, reasons

that the Afterlife is better, since in addition to the benefits conferred by living

virtuously, the agent's will is no longer impeded by circumstances. In the Afterlife we

are no longer subject to the body, for instance, and hence are not bound by physical

necessities such as food, shelter, clothing, and the like. The agent can therefore be as

purely happy as life in accordance with virtue could permit, when no external

circumstances could affect the agent's actions. The Philosopher grants that the

Afterlife so understood is a clear improvement even on the virtuous life in this world,

and joins with the Christian in a cooperative endeavour to define the nature of the

virtues and the Supreme Good. Virtue is its own reward, and in the Afterlife nothing

prevents us from rewarding ourselves with virtue to the fullest extent possible.

7. Theology

Abelard held that reasoning has a limited role to play in matters of faith. That he gave

reasoning a role at all brought him into conflict with those we now call anti-

dialecticians, including his fellow abbot Bernard of Clairvaux. That the role he gave

it is limited brought him into conflict with those he called pseudo-dialecticians,

including his former teacher Roscelin.

Bernard of Clairvaux and other anti-dialecticians seem to have thought that the

meaning of a proposition of the faith, to the extent that it can be grasped, is plain;

beyond that plain meaning, there is nothing we can grasp at all, in which case reason

is clearly no help. That is, the anti-dialecticians were semantic realists about the

(plain) meaning of (religious) sentences. Hence their impatience with Abelard, who

seemed not only bent on obfuscating the plain meaning of propositions of the faith,

which is bad enough, but to do so by reasoning, which has no place either in grasping

the plain meaning (since the very plainness of plain meaning consists in its being

grasped immediately without reasoning) or in reaching some more profound

understanding (since only the plain meaning is open to us at all).

Abelard has no patience for the semantic realism that underlies the sophisticated anti-

dialectical position. Rather than argue against it explicitly, he tries to undermine it.

From his commentaries on scripture and dogma to his works of speculative theology,

Abelard is first and foremost concerned to show how religious claims can be

understood, and in particular how the application of dialectical methods can clarify

and illuminate propositions of the faith. Furthermore, he rejects the claim that there is

a plain meaning to be grasped. Outlining his method in the Prologue to his Sic et non,

Abelard describes how he initially raises a question, e.g. whether priests are required

to be celibate, and then arranges citations from scriptural and patristic authorities that

at least seem to answer the question directly into positive and negative responses.

(Abelard offers advice in the Prologue for resolving the apparent contradictions

among the authorities using a variety of techniques: see whether the words are used in

the same sense on both sides; draw relevant distinctions to resolve the issue; look at

the context of the citation; make sure that an author is speaking in his own voice

rather than merely reporting or paraphrasing someone else's position; and so on.) Now

each authority Abelard cites seems to speak clearly and unambiguously either for a

positive answer to a given question or for a negative one. If ever there were cases of

plain meaning, Abelard seems to have found them in authorities, on opposing sides of

controversial issues. His advice in the Prologue amounts to saying that sentences that

seem to be perfect exemplars of plain meaning in fact have to be carefully scrutinized

to see just what their meaning is. Yet that is just to say that they do not have plain

meaning at all; we have to use reason to uncover their meaning. Hence the anti-

dialecticians don't have a case.

There is a far more serious threat to the proper use of reason in religion, Abelard

thinks (Theologia christiana 3.20):

Those who claim to be dialecticians are usually led more easily to [heresy] the more

they hold themselves to be well-equipped with reasons, and, to that extent more

secure, they presume to attack or defend any position the more freely. Their arrogance

is so great that they think there isn't anything that can't be understood and explained

by their petty little lines of reasoning. Holding all authorities in contempt, they glory

in believing only themselvesfor those who accept only what their reason persuades

them of, surely answer to themselves alone, as if they had eyes that were unacquainted

with darkness.

Such pseudo-dialecticians take reason to be the final arbiter of all claims, including

claims about matters of faith. More exactly, Abelard charges them with holding that

(a) everything can be explained by human reason; (b) we should only accept what

reason persuades us of; (c) appeals to authority have no rational persuasive force. Real

dialecticians, he maintains, reject (a)(c), recognizing that human reason has limits,

and that some important truths may lie outside those limits but not beyond belief;

which claims about matters of faith we should accept depends on both the epistemic

reliability of their sources (the authorities) and their consonance with reason to the

extent they can be investigated.

Abelard's arguments for rejecting (a)(c) are sophisticated and subtle. For the claim

that reason may be fruitfully applied to a particular article of faith, Abelard offers a

particular case study in his own writings. The bulk of Abelard's work on theology is

devoted to his dialectical investigation of the Trinity. He elaborates an original theory

of identity to address issues surrounding the Trinity, one that has wider applicability

in metaphysics. The upshot of his enquiries is that belief in the Trinity is rationally

justifiable since as far as reason can take us we find that the doctrine makes senseat

least, once the tools of dialectic have been properly employed.

The traditional account of identity, derived from Boethius, holds that things may be

either generically, specifically, or numerically the same or different. Abelard accepts

this account but finds it not sufficiently fine-grained to deal with the Trinity. The core

of his theory of identity, as presented in his Theologia christiana, consists in four

additional modes of identity: (1) essential sameness and difference; (2) numerical

sameness and difference, which Abelard ties closely to essential sameness and

difference, allowing a more fine-grained distinction than Boethius could allow; (3)

sameness and difference in definition; (4) sameness and difference in property (in

proprietate). Roughly, Abelard's account of essential and numerical sameness is

intended to improve upon the identity-conditions for things in the world given by the

traditional account; his account of sameness in definition is meant to supply identity-

conditions for the features of things; and his account of sameness in property opens up

the possibility of there being different identity-conditions for a single thing having

several distinct features.

Abelard holds that two things are the same in essence when they are numerically the

same concrete thing (essentia), and essentially different otherwise. The Morning Star

is essentially the same as the Evening Star, for instance, since each is the selfsame

planet Venus. Again, the formal elements that constitute a concrete thing are

essentially the same as one another and essentially the same as the concrete thing of

which they are the formal constituents: Socrates is his essence (Socrates is what it is

to be Socrates). The corresponding general thesis does not hold for parts, however.

Abelard maintains that the part is essentially different from the integral whole of

which it is a part, reasoning that a given part is completely contained, along with other

parts, in the whole, and so is less than the quantity of the whole.

Numerical difference does not map precisely onto essential difference. The failure of

numerical sameness may be due to one of two causes. First, objects are not

numerically the same when one has a part that the other does not have, in which case

the objects are essentially different as well. Second, objects are numerically different

when neither has a part belonging to the other. Numerical difference thus entails the

failure of numerical sameness, but not conversely: a part is not numerically the same

as its whole, but it is not numerically different from its whole. Thus one thing is

essentially different from another when either they have only a part in common, in

which case they are not numerically the same; or they have no parts in common, in

which case they are numerically different as well as not numerically the same. Since

things may be neither numerically the same nor numerically different, the question

How many things are there? is ill-formed as it stands and must be made more

precise, a fact Abelard exploits in his discussion of the Trinity.

Essential and numerical sameness and difference apply directly to things in the world;

they are extensional forms of identity. By contrast, sameness and difference in

definition is roughly analogous to modern theories of the identity of properties.

Abelard holds that things are the same in definition when what it is to be one requires

that it be the other, and conversely; otherwise they differ in definition.

Finally, things are the same in property when they specify features that characterize

one another. Abelard offers an example to clarify this notion. A cube of marble

exemplifies both whiteness and hardness; what is white is essentially the same as what

is hard, since they are numerically the same concrete thing, namely the marble cube;

yet the whiteness and the hardness in the marble cube clearly differ in definitionbut

even so, what is white is characterized by hardness (the white thing is hard), and

conversely what is hard is characterized by whiteness (the hard thing is white). The

properties of whiteness and hardness are mixed since, despite their being different in

definition, each applies to the selfsame concrete thing (namely the marble cube) as

such and also as it is characterized by the other.

The interesting case is where something has properties that remain so completely

unmixed that the items they characterize are different in property. Consider a form-

matter composite in relation to its matter. The matter out of which a form-matter

composite is made is essentially the same as the composite, since each is the entire

material composite itself. Yet despite their essential sameness, they are not identical;

the matter is not the composite, nor conversely. The matter is not the composite, for

the composite comes to be out of the matter, but the matter does not come to be out of

itself. The composite is not the matter, since nothing is in any way a constitutive part

of or naturally prior to itself. Instead, the matter is prior to the composite since it has

the property priority with respect to the composite, whereas the composite is posterior

to its matter since it has the property posteriority with respect to its matter. Now

despite being essentially the same, the matter is not characterized by posteriority,

unlike the composite, and the composite is not characterized by priority, unlike the

matter. Hence the matter and composite are different in property; the

properties priority and posteriority are unmixedthey differ in property.

Now for the payoff. Abelard deploys his theory of identity to shed light on the Trinity

as follows. The three Persons are essentially the same as one another, since they are

all the same concrete thing (namely God). They differ from one another in definition,

since what it is to be the Father is not the same as what it is to be the Son or what it is

to be the Holy Spirit. The three Persons are numerically different from one another,

for otherwise they would not be three, but they are not numerically different from

God: if they were there would be three gods, not one. Moreover, each Person has

properties that uniquely apply to itunbegotten to the Father, begotten to the Son,

and proceeding to the Holy Spiritas well as properties that are distinctive of it, such

as power for the Father, wisdom for the Son, and goodness for the Holy Spirit. The

unique properties are unmixed in Abelard's technical sense, for the Persons differ

from one another in their unique properties, and such properties do not apply to God;

the distinctive properties are mixed, though, in that God is characterized by each (the

powerful God is the wise God is the good God). Further than that, Abelard holds,

human reason cannot go; but reason validates the analysis (strictly speaking only a

likeness or analogy) as far as it can go.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Compliance Bulletin Data PrivacyDocument1 pageCompliance Bulletin Data Privacylancekim21Pas encore d'évaluation

- DPA QuickGuidefolder 1019 PDFDocument1 pageDPA QuickGuidefolder 1019 PDFMa Mayla Imelda LapaPas encore d'évaluation

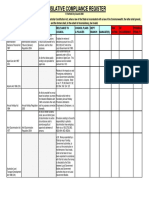

- Pub CH Compliance Management SystemsDocument40 pagesPub CH Compliance Management Systemslancekim21Pas encore d'évaluation

- Fair Lending Training ChecklistDocument1 pageFair Lending Training Checklistlancekim21Pas encore d'évaluation

- D - Introduction To Philippine Folk DanceDocument4 pagesD - Introduction To Philippine Folk DanceNicole MatutePas encore d'évaluation

- Compliance with Bank Security RulesDocument5 pagesCompliance with Bank Security Ruleslancekim21100% (1)

- Us Aers Testing and Monitoring The Fifth IngredientDocument8 pagesUs Aers Testing and Monitoring The Fifth Ingredientlancekim21Pas encore d'évaluation

- D - Introduction To Philippine Folk DanceDocument4 pagesD - Introduction To Philippine Folk DanceNicole MatutePas encore d'évaluation

- Activity 3 Interpret and TeachDocument1 pageActivity 3 Interpret and Teachlancekim21Pas encore d'évaluation

- Legal Compliance ChecklistDocument19 pagesLegal Compliance Checklistlancekim21Pas encore d'évaluation

- Legislative Compliance RegisterDocument26 pagesLegislative Compliance Registerlancekim21Pas encore d'évaluation

- Navigating The Changes To Ifrs 2020Document60 pagesNavigating The Changes To Ifrs 2020lancekim21Pas encore d'évaluation

- PNB Data Privacy Client Consent FormDocument1 pagePNB Data Privacy Client Consent Formlancekim21Pas encore d'évaluation

- RPAC - 26 July 2019Document21 pagesRPAC - 26 July 2019lancekim21Pas encore d'évaluation

- Joint Ventures in The Philippines - Nicolas & de Vega Law OfficesDocument5 pagesJoint Ventures in The Philippines - Nicolas & de Vega Law Officeslancekim21Pas encore d'évaluation

- Joint VentureDocument35 pagesJoint VentureleeashleePas encore d'évaluation

- 2019legislation - Revised Corporation Code Comparative Matrix PDFDocument120 pages2019legislation - Revised Corporation Code Comparative Matrix PDFlancekim21Pas encore d'évaluation

- Data Privacy Consent FormDocument1 pageData Privacy Consent FormAraceli Gloria100% (2)

- 2019legislation - Revised Corporation Code Comparative Matrix PDFDocument120 pages2019legislation - Revised Corporation Code Comparative Matrix PDFlancekim21Pas encore d'évaluation

- Tool Project ManagerDocument21 pagesTool Project Managersharafudheen_sPas encore d'évaluation

- Rules on Bancassurance and Variable Life InsuranceDocument24 pagesRules on Bancassurance and Variable Life Insurancelancekim21Pas encore d'évaluation

- Raci GuideDocument7 pagesRaci Guidelancekim21Pas encore d'évaluation

- Salesforce The Path Toward EqualityDocument18 pagesSalesforce The Path Toward Equalitylancekim21Pas encore d'évaluation

- 5 Money Rules The Rich Have MasteredDocument163 pages5 Money Rules The Rich Have Masteredlancekim21100% (3)

- Summary of Risk Rating Exercise Feedback IA&C v2Document54 pagesSummary of Risk Rating Exercise Feedback IA&C v2lancekim21Pas encore d'évaluation

- CL2013 33Document25 pagesCL2013 33lancekim21Pas encore d'évaluation

- Port Management and Operations PDFDocument429 pagesPort Management and Operations PDFAbdul Wahab100% (1)

- HSBC Training Deck - Income and GrowthDocument42 pagesHSBC Training Deck - Income and Growthlancekim21Pas encore d'évaluation

- CPI2017 FullDataSetDocument92 pagesCPI2017 FullDataSetDouglas EstradaPas encore d'évaluation

- Rules on Bancassurance and Variable Life InsuranceDocument24 pagesRules on Bancassurance and Variable Life Insurancelancekim21Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)