Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Labor Extra Doctrines

Transféré par

Jech TiuTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

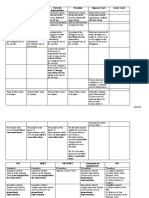

Labor Extra Doctrines

Transféré par

Jech TiuDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

PALACOL VS.

FERRER-CALLEJA

Petitioners cited Galvadores v. Trajano wherein it was ruled that no check-offs from

any amount due employees may be effected without individual written

authorizations duly signed by the employees specifically stating the amount,

purpose, and beneficiary of the deduction.

Galvadores provides "that employees are protected by law from unwarranted

practices that diminish their compensation without their knowledge and consent."

GENERAL RUBBER AND FOOTWEAR CORPORATION VS. DRILON

Generally, a judgment on a compromise agreement puts an end to a litigation and is

immediately executory. However, the Rules [of Court] require a special authority

before an attorney can compromise the litigation of [his] clients. The authority to

compromise cannot lightly be presumed and should be duly established by evidence.

As aptly held by the Secretary of Labor, the records are bereft of showing that the

individual members consented to the said agreement. Undoubtedly, the compromise

agreement was executed to the prejudice of the complainants who never consented

thereto, hence, it is null and void. The judgment based on such agreement does not

bind the individual members or complainants who are not parties thereto nor

signatories therein.

Money claims due to laborers cannot be the object of settlement or compromise

effected by a union or counsel without the specific individual consent of each laborer

concerned. The beneficiaries are the individual complainants themselves. The union to

which they belong can only assist them but cannot decide for them.

It should perhaps be made clear that the Court is not here saying that accrued

money claims can never be effectively waived by workers and employees. What the

Court is saying is that, in the present case, the private respondents never purported

to waive their claims to accrued differential pay. Assuming that private respondents

had actually and individually purported to waive such claims, a second question

would then have arisen: whether such waiver could be given legal effect or

whether, on the contrary, it was violative of public policy. Fortunately, we do not

have to address this second question here.

GENERAL MILLING CORPORATION VS. CASIO

In Malayang Samahan ng mga Manggagawa sa M. Greenfield, the Court held that

notwithstanding the fact that the dismissal was at the instance of the federation and

that the federation undertook to hold the company free from any liability resulting

from the dismissal of several employees, the company may still be held liable if it

was remiss in its duty to accord the would-be dismissed employees their right to be

heard on the matter.

LEGEND INTERNATIONAL RESORTS LIMITED VS. KILUSANG MANGGAGAWA NG LEGENDA

Once a union acquires a legitimate status as a labor organization, it continues as

such until its certificate of registration is cancelled or revoked in an independent

action for cancellation.

Section 11, Paragraph II, Rule IX of D.O. 9, which provides for the dismissal of a

petition for certification election based on the lack of legal personality of a labor

organization only in the following instances:

(1) appellant is not listed by the Regional Office or the BLR in its registry of

legitimate labor organizations; or

(2) appellant's legal personality has been revoked or cancelled with finality.

Since appellant is listed in the registry of legitimate labor organizations, and its

legitimacy has not been revoked or cancelled with finality, the granting of its

petition for certification election is proper.

SAMAHANG MANGGAGAWA SA CHARTER CHEMICAL SOLIDARITY OF UNIONS IN THE

PHILIPPINES FOR EMPOWERMENT AND REFORMS (SMCC-SUPER) VS. CHARTER CHEMCIAL

AND COATING CORPORATION.

The inclusion of the aforesaid supervisory employees in petitioner union does not

divest it of its status as a legitimate labor organization. The appellate courts

reliance on Toyota is misplaced in view of this Courts subsequent ruling in Republic

v. Kawashima Textile Mfg., Philippines, Inc. (hereinafter Kawashima). In Kawashima,

we explained at length how and why the Toyota doctrine no longer holds sway

under the altered state of the law and rules applicable to this case, viz:

Then came Tagaytay Highlands Int'l. Golf Club, Inc. v. Tagaytay Highlands Employees

Union-PGTWO in which the core issue was whether mingling affects the legitimacy

of a labor organization and its right to file a petition for certification election. This

time, given the altered legal milieu, the Court abandoned the view

in Toyota and Dunlopand reverted to its pronouncement in Lopez that while there is

a prohibition against the mingling of supervisory and rank-and-file employees in

one labor organization, the Labor Code does not provide for the effects thereof.

Thus, the Court held that after a labor organization has been registered, it may

exercise all the rights and privileges of a legitimate labor organization. Any

mingling between supervisory and rank-and-file employees in its membership

cannot affect its legitimacy for that is not among the grounds for cancellation of its

registration, unless such mingling was brought about by misrepresentation, false

statement or fraud under Article 239 of the Labor Code.

In San Miguel Corp. (Mandaue Packaging Products Plants) v. Mandaue Packing

Products Plants-San Miguel Packaging Products-San Miguel Corp. Monthlies Rank-

and-File Union-FFW, the Court explained that since the 1997 Amended Omnibus

Rules does not require a local or chapter to provide a list of its members, it would

be improper for the DOLE to deny recognition to said local or chapter on account of

any question pertaining to its individual members.

More to the point is Air Philippines Corporation v. Bureau of Labor Relations, which

involved a petition for cancellation of union registration filed by the employer in

1999 against a rank-and-file labor organization on the ground of mixed

membership: the Court therein reiterated its ruling in Tagaytay Highlands that the

inclusion in a union of disqualified employees is not among the grounds for

cancellation, unless such inclusion is due to misrepresentation, false statement or

fraud under the circumstances enumerated in Sections (a) and (c) of Article 239 of

the Labor Code

THE INSULAR LIFE ASSURANCE CO., EMPLOYEES ASSOCATION-NATU VS. THE INSULAR LIFE

ASSURANCE CO., LTD.

Interference constituting unfair labor practice will not cease to be such simply

because it was susceptible of being thwarted or resisted, or that it did not

proximately cause the result intended.

For success of purpose is not, and should not, be the criterion in determining

whether or not a prohibited act constitutes unfair labor practice.

Perhaps in an anticipatory effort to exculpate the company from charges of

discrimination in the readmission of strikers returning to work the company

delegated the power to readmit to a committee. But the company had chosen xxx to

screen the unionists reporting back to work. It is not difficult to imagine that the

chosen company employees having been involved in unpleasant incidents with

the picketers during the strike were hostile to the strikers. Needless to say, the

mere act of placing in the hands of employees hostile to the strikers the power of

reinstatement, is a form of discrimination in rehiring.

It has been held in a great number of decisions at espionage by an employer of

union activities, or surveillance thereof, are such instances of interference, restraint

or coercion of employees in connection with their right to organize, form and join

unions as to constitute unfair labor practice.

Where the strike was induced and provoked by improper conduct on the part of an

employer amounting to an 'unfair labor practice,' the strikers are entitled to

reinstatement with back pay.

And it is not a defense to reinstatement for the respondents to allege that the

positions of these union members have already been filled by replacements.

AHS/PHIIPPINES EMPLOYEES UNION (FFW) VS. NLRC

Concededly, retrenchment to prevent losses is considered a just cause for

terminating employment

22

and the decision whether to resort to such move or not

is a management prerogative.

23

Basic, however, in human relations is the precept

that "every person must, in the exercise of his rights, and in the performance of his

duties, act with justice, give everyone his due and observed honesty and good

faith."

24

Art. 284 of the Labor Code of the Philippines, as amended by Sec. 15 of Batas

Pambansa Blg. 130, provides:

Art. 284. Closure of establishment and reduction of personnel. The employer may

also terminate the employment of any employee due to the installation of labor-

saving devices, redundancy, retrenchment to present losses, or the closing or

cessation of operation of the establishment or undertaking unless the closing is for

the purpose of circumventing the provisions of this title, by serving a written notice

on the workers and the Ministry of Labor and Employment at least one [1] month

before the intended date thereof. ... In case of retrenchment to prevent losses and in

case of closure or cessation of operations of establishment or undertaking not due

to serious business losses or financial reverses, the separation pay shall be

equivalent to one [1] month or at least one-half [1/2] month pay for every year of

service, whichever is higher. A fraction of at least six [6] months shall be considered

one [1] whole year.

In the case at bar, the company offered to pay the 31 dismissed employees one

month salary in lieu of the one [1] month written notice required by law. This

practice was allowed under the termination Pay Laws whereby if the employee is

dismissed on the basis of just cause, the employer is not required to serve advance

written notice based on the number of years the employee has served the

employer, nor is the employer required to grant termination pay. It is only where

the dismissal is without just cause that the employer must serve timely notice on

the employee, otherwise the employer is obliged to pay the required termination

compensation, except where other applicable statutes provide a different

remedy.

27

Otherwise stated, it was the employer's failure to serve notice upon the

employee, not the cause for the dismissal, that rendered the employer answerable

for terminal pay.

28

Thus, notice may effectively be substituted by payment of the

termination pay.

Under the New Labor Code, however, even if the dismissal is based on a just cause

under Art. 284, the one-month written notice to both the affected employee and the

Minister labor is required, on top of the separation pay.

SHELL OIL WORKERS' UNION, PETITIONER, VS. SHELL COMPANY OF THE

PHILIPPINES, LTD., AND THE COURT OF INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS, RESPONDENTS.

Indrustrial Peace Act; Scope of management prerogative; Effect of collective

bargaining agreement.It is to be admitted that the stand of ShelI Company as to

the scope of management prerogative is not devoid of plausibility if it were not

bound by what was stipulated. The growth of industrial democracy fostered by the

institution of collective bargaining with the workers entitled to be represented by a

union of their choice, has no doubt contracted the sphere of what appertains solely

to the employer. What was stipulated in an existing collective bargaining contract

certainly precluded Shell Company from carrying out what otherwise would have

been within its prerogative if to do so would be violative thereof.

Same; Collective bargaining agreement must be respected.The crucial question is

whether the then existing collective bargaining contract running for three years

from August 1, 1966 to December 31, 1069 constituted a bar to such a decision

reached by management? The answer must be in the affirmative. As correct

stressed in the brief for the petitioner, there was specific coverage concerning the

security guard section in the collective bargaining contract, It is found not only in

the body thereof but in the two appendices concerning the age schedules as well as

the premium pay and the night compensation to which the personnel in such

section were entitled. It was thus an assurance of security of tenure, at least, during

the lifetime of the agreement. For what is involved is the integrity of the agreement

reached, terms of which should be binding on both parties. One of them may be

released, but only with the consent of the other. The right to object belongs to the

latter; and if exercised, must be respected. Such a state of affairs should continue

during the existence of the contract. Only thus may there be compliance with and

fulfillment of the covenants in a valid subsisting agreement.

Same; Failure to comply constitutes an unfair labor practice.The Shell Company, in

failing to manifest fealty to what was stipulated in an existing collective bargaining

contract, was thus guilty of an unfair labor practice. Such a doctrine first found

expression in Republic Savings Bank vs. Court of Industrial Relations, L-20303,

Sept. 27, 1967, 21 SCRA 226.

In the industrial Peace Act, an unfair labor practice is committed by a labor union or

its agent by its refusal 'to bargain collectively with the employer'. However, the

collective bargaining does not end with the execution of an agreement, being a

continuous process, the duty to bargain necessarily imposing on the parties the

obligation to live up to the terms of such a collective bargaining agreement if

entered into, it is undeniable that non-compliance therewith constitutes an unfair

labor practice.

Same; Right of labor to strike.Accordingly, the unfair labor practice strike called

by the Union did have the impress of validity. Rightly, labor is justified in making

use of such a weapon in its arsenal to counteract what is clearly outlawed by the

Industrial Peace Act. That would be one way to assure that the objectives of

unionization and collective bargaining would not be thwarted. It would, of course,

file an unfair labor practice case before the Court of Industrial Relations. It is not

precluded, however, from relying on its own resources to frustrate such an effort

on the part of an employer.

There is this categorial pronouncement from the present Chief Justice: "Again, the

legality of the strike follows as a corollary to the finding of fact, made in the

decision appealed from which is supported by substantial evidence to the

effect that the strike had triggered by the Company's failure to abide by the terms

and conditions of its collective bargaining agreement with the Union, by the

discrimination, resorted to by the company, with regard to hire and tenure of

employment, and the dismissal of employees due to union activities, as well as the

refusal of the company to bargain collectively in good faith."

It is not even required that there be in fact an unfair labor practice committed by

the employer. It suffices, if such a belief in good faith is entertained by labor, as the

inducing factor for staging a strike.

The right to self-organization so sedulously guarded by the Industrial Peace Act

explicitly includes the right "to engage in concerted activities for the purpose of

collective bargaining and to the mutual aid or protection."

As a matter of fact, a strike may not be staged only when, during the pendency of an

industrial dispute, the Court of industrial Relations has issued the proper injunction

against the laborers (section 19, Commonwealth Act No. 103, as amended).

Same; When to strike.Necessarily so, the choice as to when such an objective may

be attained by striking likewise belongs to it. There is the rejection of the concept

that an outside authority, even if governmental, should make the decisions for it as

to ends which are desirable and how they may be achieved. The assumption is that

labor can be trusted to determine for itself when the right to strike may be availed

of in order to attain a successful fruition in their disputes with management. It is

true that there is a requirement in the Act that before the employees may do so,

they must file with the Conciliation Service of the Department of Labor a notice of

their intention to strike. Such a requisite however, as has been repeatedly declared

by this Court, does not have to be complied with in case of unf air labor practice

strike, which certainly is entitled to greater judicial protection if the Industrial

Peace Act is to be rendered meaningful.

Same; How strike to be conducted.What is clearly within the law is the concerted

activity of cessation of work in order that a union's economic demands may be

granted or that an employer cease and desist from an unfair labor practice. That the

law recognizes as a right. There is though a disapproval of the utilization of force to

attain such as objective. For implicit in the very concept of a legal order is the

maintenance of peacef ul ways. A strike otherwise valid, if violent in character, may

be placed beyond the pale. Care is to be taken, however, especially where an unf air

labor practice is involved, to avoid stamping it with illegality just because it is

tainted by such acts. To avoid rendering illusory the recognition of the right to

strike, responsibility in such a case should be individual and not collective. A

different conclusion would be called for, of course, if the existence of force while the

strike lasts is pervasive and widespread, consistently and deliberately resorted to

as a matter of policy. It could be reasonably concluded then that even if justified as

to ends, it becomes illegal because of the means employed.

Except on those few days specified then, the Shell Company could not allege that

the strike was conducted in a manner other than peaceful. Under the

circumstances, it would be going too far to consider that it thereby became illegal.

This is not by any means to condone the utilization of force by labor to attain its

objectives. It is only to show awareness that is labor conflicts, the tension that fills

the air as well as the feeling of frustration and bitterness could break out in

sporadic acts of violence. If there be in this case a weighing of interests in the

balance, the ban the law imposes on unfair labor practices by management that

could provoke a strike and its requirement that it be conducted peaceably, it would

be, to repeat, unjustified, considering all the facts disclosed, to stamp the strike with

illegality. It is enough that individual liability be incurred by those guilty of such

acts of violence that call for loss of employee status.

Strikes are usually attended by "the excitement, the heat and the passion of the

direct participants in the labor dispute, at the peak thereof ...." There is the

recognition by this Court, speaking through Justice Castro, of picketing as such

being "inherently explosive." It is thus clear that not every form of violence suffices

to affix the seal of illegality on a strike or to cause the loss of employment by the

guilty party.

even if there was a mistake in good faith by the Union that an unfair labor practice

was committed by the Shell Company when such was not the case, still the

wholesale termination of employee status of all the officers of the Union, decreed by

CIR, hardly commends itself for approval. Such a drastic blow to a labor

organization, leaving it leaderless, has serious repercussions. The immediate effect

is to weaken the Union. New leaders may of course emerge. It would not be

unlikely, under the circumstances, that they would be less than vigorous in the

prosecution of labor's claims. They may be prove to fall victims to counsels of

timidity and apprehension. At the forefront of their consciousness must be an

awareness that a mistaken move could well mean their discharge from

employment. That would be to render the right to self-organization illusory.

Same; State protection to labor.The plain and unqualified constitutional command

of protection to labor should not be lost sight of. The State is thus under obligation

to lend its aid and its succor to the efforts of its labor elements to improve their

economic condition. It is now generally accepted that unionization is a means to

such an end. It should be encouraged. Thereby, labor's strength, what there is of it,

becomes solidified. It can bargain as a collectivity. Management then will not

always have the upper hand nor be in a position to ignore its just demands. That, at

any rate, is the policy behind the Industrial Peace Act. The judiciary and

administrative agencies in construing it must ever be conscious of Its implications.

Only thus may there be f idelity to what is ordained by the f undamental law. For if

it were otherwise, Instead of protection, there would be neglect or disregard. That

is to negate the fundamental principle that the Constitution is the supreme law.

The strike cannot be declared illegal, there being a violation of the collective

bargaining agreement by respondent company. Even if it were otherwise, however,

this Court cannot lend sanction of its approval to the outright dismissal of all union

officers, a move that certainly would have the effect of considerably weakening a

labor organization, and thus in effect frustrate the policy of the Industrial Peace Act

to encourage unionization.

Essentially, the freedom to manage the business remains with management. It still

has plenty of elbow room for making its wishes prevail. In much the same way that

labor unions may be expected to resist to the utmost what they consider to be an

unwelcome intrusion into their exclusive domain, they cannot justly object to

management equally being jealous of its prerogatives. More specifically, it cannot

be denied the faculty of promoting efficiency and attaining economy by a study of

what units are essential for its operation. To it belongs the ultimate determination

of whether services should be performed by its personnel or contracted to outside

agencies.

MANILA MANDARIN EMPLOYEES UNION VS. NLRC

The charge of disloyalty against Beloncio arose from her emotional remark to a

waitress who happened to be a union steward, "Wala akong tiwala sa Union ninyo."

The remark was made in the course of a heated discussion regarding Beloncio's

efforts to make a lazy and recalcitrant waiter adopt a better attitude towards his

work.

The case fell within the jurisdiction of the of the NLRC, not the BLR. The question

extended to the dismissal of Beloncio or steps leading thereto. Necessarily, when

the hotel decides the recommended dismissal, its acts would be subject to scrutiny.

Particularly, it will be asked whether it violates or not the existing CBA. Certainly,

violations of the CBA would be unfair labor practice.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Jurisdiction Criminal ProcedureDocument31 pagesJurisdiction Criminal ProcedureJech TiuPas encore d'évaluation

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Constitutional Law Reviewer Jech TiuDocument52 pagesConstitutional Law Reviewer Jech TiuJech TiuPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Jurisdiction ReviewerDocument5 pagesJurisdiction ReviewerJech TiuPas encore d'évaluation

- Jurisdiction ReviewerDocument5 pagesJurisdiction ReviewerJech TiuPas encore d'évaluation

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- CPUC DecisionDocument76 pagesCPUC DecisionJech TiuPas encore d'évaluation

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Obligations and Contracts Dean Del Castillo NotesDocument57 pagesObligations and Contracts Dean Del Castillo NotesJech Tiu100% (2)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- International Commercial ArbitrationDocument46 pagesInternational Commercial ArbitrationJech Tiu0% (1)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Ublic Nternational AW: Notes AND Discussions (2009) 2-A 2012 (FR. Joaquin Bernas)Document42 pagesUblic Nternational AW: Notes AND Discussions (2009) 2-A 2012 (FR. Joaquin Bernas)Jech TiuPas encore d'évaluation

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Evidence Digests 1 PDFDocument136 pagesEvidence Digests 1 PDFJech Tiu100% (1)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- PSB v. Lantin Extra DoctrineDocument1 pagePSB v. Lantin Extra DoctrineJech TiuPas encore d'évaluation

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Chiongbian v. OrbosDocument2 pagesChiongbian v. OrbosJech TiuPas encore d'évaluation

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Moa AdDocument3 pagesMoa AdJech Tiu100% (1)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Icaew Cfab Law 2019 Study GuideDocument28 pagesIcaew Cfab Law 2019 Study GuideAnonymous ulFku1v100% (1)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- Beg Borrow and Steal Ethics Case StudyDocument7 pagesBeg Borrow and Steal Ethics Case Studyapi-130253315Pas encore d'évaluation

- EVIDENC1Document83 pagesEVIDENC1mtabcaoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Personal and Social Leadership CompetenciesDocument2 pagesPersonal and Social Leadership CompetenciesTemur Sharopov100% (2)

- Professional MisconductDocument1 pageProfessional MisconductAnonymous Azxx3Kp9Pas encore d'évaluation

- Insurance NotesDocument48 pagesInsurance NotesAnne Meagen ManingasPas encore d'évaluation

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- Asian Resurfacing of Road Agency Pvt. Ltd. and Ors. vs. Central Bureau of Investigation (28.03.2018)Document30 pagesAsian Resurfacing of Road Agency Pvt. Ltd. and Ors. vs. Central Bureau of Investigation (28.03.2018)Rishabh Nigam100% (1)

- Role of Youth in SocietyDocument9 pagesRole of Youth in SocietyDanna Krysta Gem Laureano100% (1)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- Minutes of The DefenseDocument3 pagesMinutes of The DefenseGladys Sarah CostillasPas encore d'évaluation

- Payment of Gratuity The Payment of GratuityDocument4 pagesPayment of Gratuity The Payment of Gratuitysubhasishmajumdar100% (1)

- Group 3Document106 pagesGroup 3Princess JereyviahPas encore d'évaluation

- Definition and Nature of PlanningDocument7 pagesDefinition and Nature of PlanningCath Domingo - LacistePas encore d'évaluation

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Caparo V DickmanDocument66 pagesCaparo V Dickmannovusadvocates1Pas encore d'évaluation

- Manaloto Vs VelosoDocument11 pagesManaloto Vs VelosocessyJDPas encore d'évaluation

- SPS Borromeo Vs CADocument2 pagesSPS Borromeo Vs CAJames PagdangananPas encore d'évaluation

- Catalina of DumagueteDocument2 pagesCatalina of DumagueteJames CulanagPas encore d'évaluation

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Sison v. Ancheta - CaseDocument13 pagesSison v. Ancheta - CaseRobeh AtudPas encore d'évaluation

- Soalan xx2Document5 pagesSoalan xx2Venessa LauPas encore d'évaluation

- LG Foods V AgraviadorDocument2 pagesLG Foods V AgraviadorMaica MahusayPas encore d'évaluation

- Deadliest Prisons On EarthDocument5 pagesDeadliest Prisons On Earth105705Pas encore d'évaluation

- Grammar Practice Worksheet 1Document5 pagesGrammar Practice Worksheet 1MB0% (2)

- Ethics IndiaDocument4 pagesEthics IndialamyaaPas encore d'évaluation

- UNFPA Career GuideDocument31 pagesUNFPA Career Guidealylanuza100% (1)

- Types of Case StudiesDocument2 pagesTypes of Case Studiespooja kothariPas encore d'évaluation

- Is The Glass Half Empty or Half FullDocument3 pagesIs The Glass Half Empty or Half FullAdonis SferaPas encore d'évaluation

- Format. Hum - Functional Exploration Ofola Rotimi's Our Husband Has Gone Mad AgainDocument10 pagesFormat. Hum - Functional Exploration Ofola Rotimi's Our Husband Has Gone Mad AgainImpact JournalsPas encore d'évaluation

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Script LWR Report Noli MeDocument1 pageScript LWR Report Noli MeAngelEncarnacionCorralPas encore d'évaluation

- Good Reads ListDocument6 pagesGood Reads Listritz scPas encore d'évaluation

- The Holy Prophet's (Pbuh) Behavior Towards OthersDocument7 pagesThe Holy Prophet's (Pbuh) Behavior Towards OthersFatima AbaidPas encore d'évaluation

- Code of Business Conduct and EthicsDocument2 pagesCode of Business Conduct and EthicsSam GitongaPas encore d'évaluation