Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Agam Ben

Transféré par

anfilbiblioCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Agam Ben

Transféré par

anfilbiblioDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

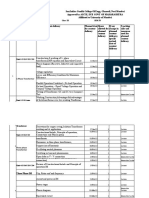

Giorgio Agamben

Giorgio Agamben

Wall painting of Agamben at the Abode of

Chaos, France

Born

22 April 1942 (age 72)

Rome, Italy

Era

Contemporary philosophy

Region

Western philosophy

School

Continental philosophy

Main interests

Aesthetics

Political philosophy

Notable ideas

Homo sacer

"state of exception"

"whatever singularity", "la vita

nuda", auctoritas, form-of-life,

the zoebios distinction as

the "fundamental categorial

pair of Western politics,"

[1]

the

"paradox of sovereignty"

[2]

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Giorgio Agamben (Italian: [aambn]; born 22 April 1942) is an Italian

Continental philosopher best known for his work investigating the concepts of

the state of exception,

[3]

form-of-life and homo sacer. The concept of biopolitics

(borrowed from Michel Foucault) informs many of his writings.

Contents [hide]

1 Biography

2 Work

2.1 The Coming Community (1993)

2.2 Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life (1995)

2.3 State of Exception (2005)

2.3.1 Auctoritas, "charisma" and Fhrertum doctrine

2.3.2 Interregnum, justitium and nomos empsuchos (the sovereign as "living

law")

2.4 Criticism of US response to 911

3 Bibliography

4 See also

5 Notes and references

6 Further reading

7 External links

7.1 Text

7.2 Video lectures

7.3 Audio lectures

7.4 Art film

Biography [edit]

Agamben was educated at the University of Rome, where he wrote an

unpublished thesis on the political thought of Simone Weil. Agamben participated

in Martin Heidegger's Le Thor seminars (on Heraclitus and Hegel) in 1966 and

1968.

[4]

In the 1970s, he worked primarily on linguistics, philology, poetics, and

topics in medieval culture. During this period, Agamben began to elaborate his

primary concerns, although their political bearings were not yet made explicit. In

19741975 he was a fellow at the Warburg Institute, University of London, due to

the courtesy of Frances Yates, whom he met through Italo Calvino. During this

fellowship, Agamben began to develop his second book, Stanzas (1977).

Agamben was close to the poets Giorgio Caproni and Jos Bergamn, and to the Italian novelist Elsa Morante, to whom he

devoted the essays "The Celebration of the Hidden Treasure" (in The End of the Poem) and "Parody" (in Profanations). He

has been a friend and collaborator to such eminent intellectuals as Pier Paolo Pasolini (in whose The Gospel According to St.

Matthew he played the part of Philip), Italo Calvino (with whom he collaborated, for a short while, as counsellor of the

publishing house Einaudi and developed plans for a journal), Ingeborg Bachmann, Pierre Klossowski, Guy Debord, Jean-Luc

Nancy, Jacques Derrida, Antonio Negri, Jean-Franois Lyotard and others.

His strongest influences include Martin Heidegger, Walter Benjamin and Michel Foucault. Agamben edited Benjamin's

collected works in Italian translation until 1996, and called Benjamin's thought "the antidote that allowed me to survive

Heidegger."

[5]

In 1981, Agamben discovered several important lost manuscripts by Benjamin in the archives of the

Bibliothque nationale de France. Benjamin had left these manuscripts to Georges Bataille when he fled Paris shortly before

his death. The most relevant of these to Agamben's own later work were Benjamin's manuscripts for his theses On the

Concept of History.

[6]

Agamben has engaged since the nineties in a debate with the political writings of the German jurist Carl

Schmitt, most extensively in the study State of Exception (2003). His recent writings also elaborate on the concepts of Michel

Foucault, whom he calls "a scholar from whom I have learned a great deal in recent years".

[7]

Agamben's political thought was originally founded on his readings of Aristotle's Politics, Nicomachean Ethics, and treatise On

the Soul, as well as the exegetical traditions concerning these texts in late antiquity and the Middle Ages. In his later work,

Agamben intervenes in the theoretical debates following the publication of Nancy's essay La communaut dsoeuvre

(1983),

[8]

and Maurice Blanchot's response, La communaut inavouable (1983). These texts analyzed the notion of

Influenced by [show]

Influenced [show]

Article Talk Read Edit

Search

Edit links

Main page

Contents

Featured content

Current events

Random article

Donate to Wikipedia

Wikimedia Shop

Interaction

Help

About Wikipedia

Community portal

Recent changes

Contact page

Tools

What links here

Related changes

Upload file

Special pages

Permanent link

Page information

Data item

Cite this page

Print/export

Create a book

Download as PDF

Printable version

Languages

Catal

etina

Dansk

Deutsch

Eesti

Espaol

Franais

Galego

Italiano

Latina

Nederlands

Polski

Portugus

Slovenina

Suomi

Svenska

Trke

Create account Log in

converted by Web2PDFConvert.com

community at a time when the European Community was under debate. Agamben proposed his own model of a community

which would not presuppose categories of identity in The Coming Community (1990). At this time, Agamben also analyzed the

ontological condition and "political" attitude of Bartleby (from Herman Melville's short story) a scrivener who does not react,

and "prefers not" to write.

Currently, Agamben is teaching at Accademia di Architettura di Mendrisio (Universit della Svizzera Italiana) and has taught at

the Universit IUAV di Venezia, the Collge International de Philosophie in Paris, and the European Graduate School in Saas-

Fee, Switzerland; he previously taught at the University of Macerata and at the University of Verona, both in Italy.

[9]

He also

has held visiting appointments at several American universities, from the University of California, Berkeley, to Northwestern

University, Evanston, and at Heinrich Heine University, Dsseldorf. Agamben received the Prix Europen de l'Essai Charles

Veillon in 2006.

[10]

Work [edit]

Much of Giorgio Agamben's work since the 1980s can be viewed to leading up to the so-called Homo Sacer-project, that

properly begins with the book Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. In this series of works, Agamben responds to

Hannah Arendt's and Foucault's studies of totalitarianism and biopolitics. Since 1995 he has been best known for this ongoing

project, the volumes of which have been published out of order, and which currently include:

[11]

Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life (1995)

State of Exception. Homo Sacer II, 1 (2003)

The Kingdom and the Glory: For a Theological Genealogy of Economy and Government. Homo Sacer II, 2 (2007)

The Sacrament of Language: An Archaeology of the Oath. Homo Sacer II, 3 (2008)

Opus Dei: An Archeology of Duty. Homo Sacer II, 5 (2013)

[12]

Remnants of Auschwitz: The Witness and the Archive. Homo Sacer III (1998).

The Highest Poverty: Monastic Rules and Forms-of-Life. Homo Sacer IV, 1

[13]

In the final volume of the series, Agamben intends to address "the concepts of forms-of-life and lifestyles." "What I call a form-

of-life," he explains, "is a life which can never be separated from its form, a life in which it is never possible to separate

something like bare life. [...] [H]ere too the concept of privacy comes in to play."

[14]

If human beings were or had to be this or that substance, this or that destiny, no ethical experience would be

possible... This does not mean, however, that humans are not, and do not have to be, something, that they are simply

consigned to nothingness and therefore can freely decide whether to be or not to be, to adopt or not to adopt this or

that destiny (nihilism and decisionism coincide at this point). There is in effect something that humans are and have

to be, but this is not an essence nor properly a thing: It is the simple fact of one's own existence as possibility or

potentiality...

[15]

The reduction of life to 'biopolitics' is one of the main threads in Agamben's work, in his critical conception of a homo sacer,

reduced to 'bare life', and thus deprived of any rights. Agamben's concept of the homo sacer rests on a crucial distinction in

Greek between 'bare life' (la vita nuda, Gk. : zo) and 'a particular mode of life' or 'qualified life.' In Part III, section 7 of

Homo Sacer, The Camp as the 'Nomos' of the Modern, he evokes the concentration camps of World War II. The camp is

the space that is opened when the state of exception begins to become the rule. Agamben says that "What happened in the

camps so exceeds (is outside of) the juridical concept of crime that the specific juridico-political structure in which those

events took place is often simply omitted from consideration." The conditions in the camps were "conditio inhumana," and the

incarcerated somehow defined outside the boundaries of humanity, under the exception laws of Schutzhaft. Where law is

based on vague, unspecific concepts such as "race" or "good morals," law and the personal subjectivity of the judicial agent

are no longer distinct.

In United States criminal law, people accused of committing crimes cannot be compelled to incriminate themselves verbally,

but can be compelled to incriminate themselves physically.

[16]

In the process of creating a state of exception these effects

can compound. In a realized state of exception, one who has been accused of committing a crime, within the legal system,

loses the ability to use his voice and represent themselves. The individual can not only be deprived of their citizenship, but

also of any form of agency over their own life. Agamben identifies the state of exception with the power of decision over life.

[17]

Within the state of exception, the distinction between bios (citizen) and zoe (homo sacer) is made by those with judicial

power. For example, Agamben would argue that Guantnamo Bay exemplifies the concept of 'the state of exception' in the

United States following 911.

Agamben mentions that basic universal human rights of Taliban individuals while captured in Afghanistan and sent to

Guantnamo Bay in 2001 were negated by US laws. In reaction to the removal of their basic human rights, detainees of

Guantnamo Bay prison went on hunger strikes. Within a state of exception, when a detainee is placed outside of the law, he

is according to Agamben, reduced to 'bare life' in the eyes of the judicial powers.

[citation needed]

Here, one can see why such

measures as hunger strikes can occur in such places as prisons. Within the framework of a system that has deprived the

individual of power, and their individual basic human freedoms, the hunger strike can be seen as a weapon or form of

converted by Web2PDFConvert.com

resistance. The body is a model which can stand for any bounded system. Its boundaries can represent any boundaries

which are threatened or precarious.

[18]

Within a state of exception the boundaries of power are precarious and threaten to

destabilize not only the law, but ones humanity, as well as their choice of life or death. Forms of resistance to the extended

use of power within the state of exception as suggested in Guantnamo Bay prison also operate outside of the law. In the

case of the hunger strike, the prisoners were threatened and endured force feeding not allowing them to die. During the

hunger strikes at Guantnamo Bay prison, accusations and founded claims of forced feedings began to surface in the

autumn of 2005. In February 2006, The New York Times reported that prisoners were being force fed in Guantnamo Bay

prison and in March 2006, more than 250 medical experts, as reported by the BBC,

[19]

voiced their opinions of the forced

feedings stating that this was a breach of the governments power and was against the rights of the prisoners.

The Coming Community (1993) [edit]

In The Coming Community, published in Italian in 1990 and translated into English by longtime admirer Michael Hardt in 1993,

Agamben describes the social and political manifestation of his philosophical thought. Employing diverse short essays he

describes the nature of whatever singularity as that which has an inessential commonality, a solidarity that in no way

concerns an essence. It is important to note his understanding of whatever not as being indifference but based on the Latin

translation of being such that it always matters.

Agamben starts off by describing The Lovable

Love is never directed toward this or that property of the loved one (being blond, being small, being tender, being

lame), but neither does it neglect the properties in favor of an insipid generality (universal love): The lover wants the

loved one with all of its predicates, its being such as it is.

[20]

In the same sense, Agamben talks about "ease" as the "place" of love, or "rather love as the experience of taking-place in a

whatever singularity", which resonates his use of the concept "use" in the later works.

In this sense, ease names perfectly that "free use of the proper" that, according to an expression of Friedrich

Hlderlin's, is "the most difficult task."

[21]

Following the same trend, he employs, among others, the following to describe the watershed of whatever:

Example particular and universal

Limbo blessed and damned

Homonym concept and idea

Halo potentiality and actuality

Face common and proper, genus and individual

Threshold inside and outside

Coming community state and non-state (humanity)

[22]

Other themes addressed in The Coming Community include the commodification of the body, evil, and the messianic.

Unlike other continental philosophers he does not reject the age-old dichotomies of subject/object and potentiality/actuality

outright, but rather turns them inside-out, pointing out the zone where they become indistinguishable.

Matter that does not remain beneath form, but surrounds it with a halo

[22]

The political task of humanity, he argues, is to expose the innate potential in this zone of indistinguishability. And although

criticised as dreaming the impossible by certain authors,

[23]

he nonetheless shows a concrete example of whatever singularity

acting politically:

Whatever singularity, which wants to appropriate belonging itself, its own being-in-language, and thus rejects all

identity and every condition of belonging, is the principal enemy of the State. Wherever these singularities peacefully

demonstrate their being in common there will be Tiananmen, and, sooner or later, the tanks will appear

[24]

Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life (1995) [edit]

Main article: Homo sacer

converted by Web2PDFConvert.com

In his main work "Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life" (1998), Giorgio Agamben analyzes an obscure

[25]

figure of

Roman law that poses some fundamental questions to the nature of law and power in general. Under the Roman Empire, a

man who committed a certain kind of crime was banned from society and all of his rights as a citizen were revoked. He thus

became a "homo sacer" (sacred man). In consequence, he could be killed by anybody, while his life on the other hand was

deemed "sacred", so he could not be sacrificed in a ritual ceremony.

Roman law no longer applied to someone deemed a Homo sacer, although they would remain "under the spell" of law.

Agamben defines it as "human life...included in the juridical order solely in the form of its exclusion (that is, of its capacity to

be killed)". Homo sacer was therefore excluded from law itself, while being included at the same time. This figure is the exact

mirror image of the sovereign (basileus) a king, emperor, or president who stands, on the one hand, within law (so he

can be condemned, e.g., for treason, as a natural person) and outside of the law (since as a body politic he has power to

suspend law for an indefinite time).

Giorgio Agamben draws on Carl Schmitt's definition of the Sovereign as the one who has the power to decide the state of

exception (or justitium), where law is indefinitely "suspended" without being abrogated. But if Schmitt's aim is to include the

necessity of state of emergency under the rule of law, Agamben on the contrary demonstrates that all life cannot be

subsumed by law. As in Homo sacer, the state of emergency is the inclusion of life and necessity in the juridical order solely in

the form of its exclusion.

[clarification needed]

Since its origins, Agamben notes, law has had the power of defining what "bare life" zoe (Gk. ), as opposed to bios (Gk.

): qualified life is by making this exclusive operation, while at the same time gaining power over it by making it the

subject of political control. The power of law to actively separate "political" beings (citizens) from "bare life" (bodies) has

carried on from Antiquity to Modernity from, literally, Aristotle to Auschwitz. Aristotle, as Agamben notes, constitutes political

life via a simultaneous inclusion and exclusion of "bare life": as Aristotle says, man is an animal born to life (Gk. , zen), but

existing with regard to the good life ( , eu zen) which can be achieved through politics.

[26]

Bare life, in this ancient

conception of politics, is that which must be transformed, via the State, into the "good life"; that is, bare life is that which is

supposedly excluded from the higher aims of the state, yet is included precisely so that it may be transformed into this "good

life". Sovereignty, then, is conceived from ancient times as the power which determines what or who is to be incorporated into

the political body (in accord with its bios) by means of the more originary exclusion (or exception) of what is to remain outside

of the political bodywhich is at the same time the source of that body's composition (zoe).

[27]

According to Agamben,

biopower, which takes the bare lives of the citizens into its political calculations, may be more marked in the modern state, but

has essentially existed since the beginnings of sovereignty in the West, since this structure of ex-ception is essential to the

core concept of sovereignty.

[28]

Agamben would continue to expand the theory of the state of exception first introduced in "Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and

Bare Life", ultimately leading "State of Exception" in 2005. During 2003, he delivered a lecture at European Graduate School

describing the eclipse that politics has undergone.

[29]

Instead of leaving a space between law and life, the space where

human action is possible, the space that used to constitute politics, he argues that politics has contaminated itself with law in

the state of exception. Because only human action is able to cut the relationship between violence and law, it becomes

increasingly difficult within the state of exception for humanity to act against the State.

[29]

State of Exception (2005) [edit]

In this book, Giorgio Agamben traces the concept of ' state of exception' (Ausnahmezustand) used by Carl Schmitt to Roman

justitium and auctoritas. This leads him to a response to Carl Schmitt's definition of sovereignty as the power to proclaim the

exception.

Agambens text State of Exception investigates the increase of power structures governments employ in supposed times of

crisis. Within these times of crisis, Agamben refers to increased extension of power as states of exception, where questions of

citizenship and individual rights can be diminished, superseded and rejected in the process of claiming this extension of power

by a government.

The state of exception invests one person or government with the power and voice of authority over others extended well

beyond where the law has existed in the past. In every case, the state of exception marks a threshold at which logic and

praxis blur with each other and a pure violence without logos claims to realize an enunciation without any real reference"

(Agamben, pg 40). Agamben refers a continued state of exception to the Nazi state of Germany under Hitlers rule. The

entire Third Reich can be considered a state of exception that lasted twelve years. In this sense, modern totalitarianism can

be defined as the establishment, by means of the state of exception, of a legal civil war that allows for the physical elimination

not only of political adversaries but of entire categories of citizens who for some reason cannot be integrated into the political

system" (Agamben, pg 2).

The political power over others acquired through the state of exception, places one government or one form or branch of

government as all powerful, operating outside of the laws. During such times of extension of power, certain forms of

knowledge shall be privileged and accepted as true and certain voices shall be heard as valued, while of course, many others

are not. This oppressive distinction holds great importance in relation to the production of knowledge. The process of both

acquiring knowledge, and suppressing certain knowledge, is a violent act within a time of crisis.

Agambens State of Exception investigates how the suspension of laws within a state of emergency or crisis can become a

converted by Web2PDFConvert.com

prolonged state of being. More specifically, Agamben addresses how this prolonged state of exception operates to deprive

individuals of their citizenship. When speaking about the military order issued by President George W. Bush on 13 November

2001, Agamben writes, What is new about President Bushs order is that it radically erases any legal status of the individual,

thus producing a legally unnameable and unclassifiable being. Not only do the Taliban captured in Afghanistan not enjoy the

status of POWs as defined by the Geneva Convention, they do not even have the status of people charged with a crime

according to American laws" (Agamben, pg 3). Many of the individuals captured in Afghanistan were taken to be held at

Guantnamo Bay without trial. These individuals were termed as enemy combatants. Until 7 July 2006, these individuals had

been treated outside of the Geneva Conventions by the United States administration.

Auctoritas, "charisma" and Fhrertum doctrine [edit]

Agamben shows that auctoritas and potestas are clearly distinct although they form together a binary system".

[30]

He

quotes Mommsen, who explains that auctoritas is "less than an order and more than an advice".

[31]

While potestas derives from social function, auctoritas "immediately derives from the patres personal condition". As such, it is

akin to Max Weber's concept of charisma. This is why the tradition ordered, at the king's death, the creation of the sovereigns

wax-double in the funus imaginarium, as Ernst Kantorowicz demonstrated in The King's Two Bodies (1957). Hence, it is

necessary to distinguish two bodies of the sovereign in order to assure the continuity of dignitas (term used by Kantorowicz,

here a synonym of auctoritas). Moreover, in the person detaining auctoritas the sovereign public life and private life

have become inseparable. Augustus, the first Roman emperor who claimed auctoritas as the basis of princeps status in a

famous passage of Res Gestae, had opened up his house to public eyes.

The concept of auctoritas played a key-role in fascism and Nazism, in particular concerning Carl Schmitt's theories, argues

Agamben:

To understand modern phenomena such as the fascist Duce or the Nazi Fhrer, it is important not to forget their

continuity with the principle of auctoritas principis {Agamben refers here to Augustus's Res Gestae}. {...} Neither does

the Duce nor the Fhrer represent constitutionally defined public charges even though Mussolini and Hitler endorsed

respectively the charge of head of government and Reich's chancellor, just as Augustus endorsed the imperium

consulare or the potestas tribunicia. The Duces or the Fhrers qualities are immediately related to the physical

person and belong to the biopolitical tradition of auctoritas and not to the juridical tradition of potestas

[32]

Thus, Agamben opposes Foucault's concept of "biopolitics" to right (law), as he defines the state of exception, in Homo sacer,

as the inclusion of life by right under the figure of ex-ception, which is simultaneously inclusion and exclusion. Following Walter

Benjamin's lead, he explains that our task would be to radically differentiate "pure violence" from right, instead of tying them

together, as did Carl Schmitt.

Agamben concludes his chapter on "Auctoritas and potestas" writing:

It is significative that modern specialists were so inclined to admit that auctoritas was inherent to the living person of

the pater or the princeps. What was evidently an ideology or a fictio aiming to be the groundwork of auctoritas '

preeminence or, at least, specific rank compared to potestas thus became a figure of right's {law "droit"} immanence

to life. (...) Although it is evident that there can't be an eternal human type that would incarnate itself each time in

Augustus, Napoleon, Hitler, but only more or less comparable ("semblables") mechanisms {"dispositif", a term often

used by Foucault} the state of exception, justitium, the auctoritas principis, the Fhrertum -, put in use in more or

less different circumstances, in the 1930s overall, but not only in Germany, the power that Weber had defined as

"charismatic" is related to the concept of auctoritas and elaborated in a Fhrertum doctrine as the original and

personal power of a leader. In 1933, in a short article intending to define the fundamental concepts of national-

socialism, Schmitt defines the Fhrung principle by the "root identity between the leader and his entourage" {"identit

de souche entre le chef et son entourage"} (we shall note the use of weberian concepts).

[33]

Agambens thoughts on the state of emergency leads him to declare that the difference between dictatorship and democracy

is thin indeed, as rule by decree became more and more common, starting from World War I and the reorganization of

constitutional balance. Agamben often reminds that Hitler never abrogated the Weimar Constitution: he suspended it for the

whole duration of the 3rd Reich with the Reichstag Fire Decree, issued on 28 February 1933. Indefinite suspension of law is

what characterizes the state of exception. Thus, Agamben connects Greek political philosophy through to the concentration

camps of 20th century fascism, and even further, to detainment camps in the likes of Guantnamo Bay or immigration

detention centers, such as Bari, Italy, where asylum seekers have been imprisoned in football stadiums. In these kinds of

camps, entire zones of exception are being formed: the state of exception becomes a status under which certain categories of

people live, a capture of life by right. Sovereign law makes it possible to create entire areas in which the application of the law

itself is held suspended, which is the basis of Bush administration's definition of an "enemy combatant".

Interregnum, justitium and nomos empsuchos (the sovereign as "living law") [edit]

converted by Web2PDFConvert.com

In the chapter preceding "Auctoritas and potestas", Agamben advances an explanation of the transformation of justitium, a

technical term referring to the state of exception, declared to cope with tumultus state (rebellion, uprising, riots...), at the end

of the Roman Republic, into a term simply referring to the mourning of the sovereign's death during interregnum periods:

The correspondence between justitium and mourning here shows its true signification. If the sovereign is a living

nomos, if then anomie and nomos coincide in his person without any left-over, then anarchy (which, at his death,

when the link attaching him to law his broken, threatens to unleash itself in the city) must be ritualized and controlled,

by the transformation of the state of exception into public mourning and of mourning into justitium (...) Before

acquiring the modern form of a decision on emergency {Schmitt's definition}, the relationship between sovereignty and

state of exception presents itself under the form of an identity between the sovereign and anomie. As living law, the

sovereign is deeply anomos (). Here also the state of exception is the life more secret and true of the law.

[34]

The first formulation of the thesis according to which "the sovereign is a living law" found its first formulation on the treatise

"On law and justice" by pseudo-Archytas, conserved by Stobaeus.

[35]

It is the first attempt to conceive a form of sovereignty

completely enfranchised from laws, being itself the source of legitimacy.

[citation needed]

This theory must be radically

distinguished from natural rights theory or Antigone's appeal to the "eternal and unwritten laws" by which even monarchs must

abide, as it is a theory of sovereignty (in fact, it is quite the reverse of Antigone's rebellion).

Pseudo-Archytas distinguished the sovereign (basileus), who is the law, from the magistrate (archn), who limits himself to

observing the law. "Identification between law and sovereign has as consequence, writes Agamben, the scission of law into a

"living" law ( , nomos empsuchos), hierarchically superior, and a written law (, gramma), which is

subordinate to the first one". He then quotes A. Delatte's Essais sur la politique pythagoricienne (Paris, 1922), himself quoting

the pseudo-Archytas:

"I say that all communities are composed of an archn (the magistrate who commands), a commanded one, and, as tierce

party, laws. Among those ones, the living one is the sovereign (ho men empsuchos ho basileus), and the inanimate one is

the letter (gramma). Law is the first element, the king is legal, the magistrate accorded to law, the commanded free and all

of the city happy; but, in case of corruption (dvoiement), the sovereign is a tyrant, the magistrate is not accorded to law

and the community is unhappy."

[citation needed]

Criticism of US response to 911 [edit]

Giorgio Agamben is particularly critical of the United States' response to 11 September 2001, and its instrumentalization as a

permanent condition that legitimizes a "state of exception" as the dominant paradigm for governing in contemporary politics.

He warns against a "generalization of the state of exception" through laws like the USA PATRIOT Act , which means a

permanent installment of martial law and emergency powers. In January 2004, he refused to give a lecture in the United

States because under the US-VISIT he would have been required to give up his biometric information, which he believed

stripped him to a state of "bare life" (zoe) and was akin to the tattooing that the Nazis did during World War II.

[36][37]

However, Agamben's criticisms target a broader scope than the US "war on terror". As he points out in State of Exception

(2005), rule by decree has become common since World War I in all modern states, and has been since then generalized and

abused. Agamben points out a general tendency of modernity, recalling for example that when Francis Galton and Alphonse

Bertillon invented "judicial photography" for "anthropometric identification", the procedure was reserved to criminals; to the

contrary, today's society is tending toward a generalization of this procedure to all citizens, placing the population under

permanent suspicion and surveillance: "The political body thus has become a criminal body". And Agamben notes that the

Jews deportation in France and other occupied countries was made possible by the photos taken from identity cards.

[38]

Furthermore, Agamben's political criticisms open up in a larger philosophical critique of the concept of sovereignty itself, which

he argues is intrinsically related to the state of exception.

Bibliography [edit]

Agamben's major books are listed in order of first Italian publication (with the exception of Potentialities, which first appeared

in English), and English translations are listed where available. There are translations of most writings in German, French,

Portuguese, and Spanish. There is also an updated list of publications including translations to other languages and links to

texts available at his faculty page . A cronological and complete bibliography (December 2013) is available here .

L'uomo senza contenuto (1970). Translated by Georgia Albert as The Man without Content (1999). 0-8047-3554-9

Stanze. La parola e il fantasma nella cultura occidentale (1977). Trans. Ronald L. Martinez as Stanzas: Word and

Phantasm in Western Culture (1992). 0-8166-2038-5

Infanzia e storia: Distruzione dell'esperienza e origine della storia (1978). Trans. Liz Heron as Infancy and History: The

Destruction of Experience (1993). 0-86091-645-6

Il linguaggio e la morte: Un seminario sul luogo della negativit (1982). Trans. Karen E. Pinkus with Michael Hardt as

Language and Death: The Place of Negativity (1991). ISBN 0-8166-4923-5

Idea della prosa (1985). Trans. Michael Sullivan and Sam Whitsitt as Idea of Prose (1995). ISBN 0-7914-2380-8

converted by Web2PDFConvert.com

La comunit che viene (1990). Trans. Michael Hardt as The Coming Community (1993). ISBN 0-8166-2235-3

Bartleby, la formula della creazione (1993, with Gilles Deleuze). Agamben's essay trans. Daniel Heller-Roazen in

Potentialities, below (1999). ISBN 0-8047-3278-7. Deleuze's essay trans. in Deleuze, Essays Clinical and Critical (1997).

ISBN 0-8166-2569-7

Homo Sacer: Il potere soverano e la vita nuda (1995). Trans. Daniel Heller-Roazen as Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and

Bare Life (1998). ISBN 0-8047-3218-3

Mezzi senza fine. Note sulla politica (1996). Trans. Vincenzo Binetti and Cesare Casarino as Means Without End: Notes

of Politics (2000). ISBN 0-8166-3036-4

Categorie italiane. Studi di poetica (1996). Trans. Daniel Heller-Roazen as The End of the Poem: Studies in Poetics

(1999). ISBN 0-8047-3022-9

Quel che resta di Auschwitz. L'archivio e il testimone (Homo sacer III) (1998). Trans. Daniel Heller-Roazen as Remnants of

Auschwitz: The Witness and the Archive. Homo Sacer III (2002). ISBN 1-890951-17-X

Potentialities: Collected Essays in Philosophy. (1999). First published in English translation and edited by Daniel Heller-

Roazen. ISBN 0-8047-3278-7. Published in the original Italian, with additional essays, as La potenza del pensiero: Saggi e

conferenza (2005).

Il tempo che resta. Un commento alla Lettera ai Romani (2000). Trans. Patricia Dailey as The Time that Remains: A

Commentary on the Letter to the Romans (2005). ISBN 0-8047-4383-5

L'aperto. L'uomo e l'animale (2002). Trans. Kevin Attell as The Open: Man and Animal (2004). ISBN 0-8047-4738-5

Stato di Eccezione. Homo sacer, 2,1 (2003). Trans. Kevin Attell as State of Exception (2005). ISBN 0-226-00925-4

Profanazioni (2005). Trans. Jeff Fort as Profanations (2008). ISBN 1-890951-82-X

Che cos' un dispositivo? (2006). Trans. David Kishik and Stefan Pedatella in What is an Apparatus? and Other Essays

(2009). ISBN 0-8047-6230-9

L'amico (2007). Trans. David Kishik and Stefan Pedatella in What is an Apparatus? and Other Essays (2009). ISBN 0-

8047-6230-9

Ninfe (2007). Trans. Amanda Minervini as "Nymphs" in Releasing the Image: From Literature to New Media, ed. Jacques

Khalip and Robert Mitchell (2011). ISBN 978-0-8047-6137-6

Il regno e la gloria. Per una genealogia teologica dell'economia e del governo. Homo sacer 2,2 (2007). Trans. Lorenzo

Chiesa with Matteo Mandarini as The Kingdom and the Glory: For a Theological Genealogy of Economy and Government

(2011). ISBN 978-0-8047-6016-4

Che cos' il contemporaneo? (2007). Trans. David Kishik and Stefan Pedatella in What is an Apparatus? and Other

Essays (2009). ISBN 0-8047-6230-9

Signatura rerum. Sul Metodo (2008). Trans. Luca di Santo and Kevin Attell as The Signature of All Things: On Method

(2009). ISBN 978-1-890951-98-6

Il sacramento del linguaggio. Archeologia del giuramento. Homo sacer 2,3 (2008). Trans. Adam Kotsko as The Sacrament

of Language: An Archaeology of the Oath (2011).

Nudit (2009). Trans. David Kishik and Stefan Pedatella as Nudities (2010). ISBN 978-0-8047-6950-1

Angeli. Ebraismo Cristianesimo Islam (ed. Emanuele Coccia and Giorgio Agamben). Neripozza, Vicenza 2009.

La Chiesa e il Regno (2010). ISBN 978-88-7452-226-2. Trans. Leland de la Durantaye as The Church and the Kingdom

(2012). ISBN 978-0-85742-024-4

La ragazza indicibile. Mito e mistero di Kore (2010, with Monica Ferrando.) ISBN 978-88-370-7717-4. Trans. Leland de la

Durantaye and Annie Julia Wyman as The Unspeakable Girl: The Myth and Mystery of Kore (2014). ISBN 978-08-574-

2083-1

Altissima povert. Regola e forma di vita nel monachesimo (2011). ISBN 978-88-545-0545-2. Trans. Adam Kotsko as The

Highest Poverty: Monastic Rules and Form-of-Life (2013). ISBN 978-08-047-8405-4

Opus Dei. Archeologia dell'ufficio (2012). ISBN 978-88-339-2247-8 (draft translation of preface ).

Pilato e Ges (2013). ISBN 978-88-745-2409-9

Il mistero del male: Benedetto XVI e la fine dei tempi (2013). ISBN 978-88-581-0831-4

Che cos' il comando? (2013). ISBN 978-88-745-2409-9

Il fuoco e il racconto (2014). ISBN 978-88-745-2500-3

Articles and essays

"Nei campi dei senza nome" . Il Manifesto (Italy). 3 November 1998. (Italian)

"Gnes et la peste" . L'Humanit (France). 27 August 2001. (French)

The State of Emergency, extract from a lecture December 10, 2002, at the Centre Roland Barthes-University of Paris

VII, Denis Diderot. Entire french text .

Philosophical Archaeology (abstract) . Law and Critique. Vol. 20, No. 3, 2009, p. 211-231.

Introductory Note on the Concept of Democracy . Theory & Event. Vol. 13, No. 1, 2010.

Se la feroce religione del denaro divora il futuro . February 16, 2012. La Repubblica.

The 451 Manifesto December 23, 2012. Le Monde . La Repubblica .

The Latin Empire should strike back . March 15, 2013, La Repubblica . March 24, 2013, Libration .

Various articles published by Multitudes, available here .

converted by Web2PDFConvert.com

Philosophy portal

See also [edit]

Agamben's explanation of auctoritas

Agamben's response to Carl Schmitt's definition of sovereignty as the power to decide state

exception

Basileus

Homo sacer

Interregnum

Justitium

Unlawful combatants

Notes and references [edit]

1. ^ Homo Sacer, Stanford UP, 1998, p. 8.

2. ^ The paradox "consists in the fact the sovereign is, at the same time, outside and inside the juridical order." (Agamben, Homo

Sacer, Stanford UP, 1998, p. 15)

3. ^ Generally speaking, "state of exception" includes German Notstand, English state of emergency and others martial law.

Agamben prefers using this term as it underlines the structure of ex-ception, which is simultaneously of inclusion and exclusion.

"Ex-ception" can be opposed to the concept of "example" as developed by Immanuel Kant.

4. ^ See Martin Heidegger, Four Seminars (Bloomington, IN: Indiana UP, 2003).

5. ^ Leland de la Durantaye, Giorgio Agamben: A Critical Introduction (Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 2009), p. 53.

6. ^ See de la Durantaye, pp. 148-49.

7. ^ The Signature of All Things: On Method (New York: Zone, 2009), p. 7.

8. ^ Nancy's essay responded to a proposal by Jean-Christophe Bailly, who put the word and concept of community, then relatively

neglected in French philosophical discourse, up for discussion. Bailley's contribution was "The community, the number," a topic

for an issue of the French magazine Ala, which was edited at that time by Christian Bourgois. Cf. Jean-Luc Nancy, La

communaut dsoeuvre (Paris: Christian Bourgois, 1983). In English transl., The Inoperative Community (Minneapolis: University

of Minnesota Press, 1991).

9. ^ See: Giorgio Agamben Faculty profile at European Graduate School

10. ^ Fondation Charles Veillon Prix Europen de lEssai. 2006

11. ^ Leland de la Durantaye, Giorgio Agamben: A Critical Introduction (2009), p. 247

12. ^ Opus Dei Stanford University Press

13. ^ The Highest Poverty Stanford University Press

14. ^ Ulrich Rauff, "An Interview with Giorgio Agamben," German LawJournal 5.5 (2004): 613. PDF available at

Germanlawjournal.com

15. ^ The Coming Community (1993), section 11.

16. ^ Agamben, Giorgio (1985). The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World . Oxford UP. p. 111. ISBN 0195049969.

17. ^ Jacques Ranciere. Who is the Subject of the Rights of Man? South Atlantic Quarterly, 2004, 103(23):297310.

18. ^ Mary Douglas. Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo (1966) London: Ark Paperbacks, 1984, p.

116

19. ^ "Doctors attack US over Guantanamo"

20. ^ The Coming Community (1993), page 2.

21. ^ The Coming Community (1993), page 25.

22. ^

a

b

The Coming Community (1993)

[page needed]

23. ^ Tony Simoes da Silva. Strip It Bare Agambens Message For A More Hopeful World. Book Review. 2005

24. ^ The Coming Community (1993), page 86.

25. ^ Homo Sacer, p. 8

26. ^ Homo Sacer, Stanford UP, 1998, p. 66.

27. ^ "Sovereign violence is in truth founded not on a pact but on the exclusive inclusion of bare life in the state." (Homo Sacer,

Stanford UP, 1998, p. 107)

28. ^ Of course, this understanding of "biopower" is distinct from Foucault's use of the term.

29. ^

a

b

Agamben, Giorgio. The State of Exception Der Ausnahmezustand. European Graduate School. Video lecture. 2003.

30. ^ State of Exception (2005)

[page needed]

31. ^ Theodor Mommsen, Rmisches Staatsrecht ("Roman Constitutional Law", volume III) (Graz, 1969)

32. ^ State of Exception, chapter 6: "Auctoritas and potestas", 7.

33. ^ State of Exception, chapter 6, 8.

34. ^ State of Exception, chapter 5, 3.

35. ^ Fragments of On Law and Justice attributed to Archytas of Tarentum by Phillip Horky

36. ^ (French) Giorgio Agamben. "Non au tatouage biopolitique "No to Bio-Political Tattooing" " . Le Monde Diplomatique. 10 January

2004.

37. ^ "No to Bio-Political Tattooing" by Giorgio Agamben, Le Monde Diplomatique, 10 January 2004

38. ^ (French) Giorgio Agamben. "Non la biomtrie ("No to Biometrics")" . Le Monde. 5 December 2005. (also available here )

Further reading [edit]

converted by Web2PDFConvert.com

Calarco, Matthew and Steven DeCaroli, eds. Giorgio Agamben: Sovereignty and Life. Stanford, CA: Stanford University

Press, 2007.

Clemens, Justin, Nicholas Heron, and Alex Murray, eds. The Work of Giorgio Agamben: Law, Literature, Life. Edinburgh:

Edinburgh University Press, 2008.

D'Alonzo Jacopo,"El origen de la nuda vida: poltica y lenguaye en el pensamiento de Giorgio Agamben", Revista Plyade

(12), 2013, pp. 93112. http://www.caip.cl/wp-content/uploads/04.-DAlonzo.pdf

de la Durantaye, Leland. Giorgio Agamben: A Critical Introduction. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2009.

Dell'Aia, Lucia (ed.), Studi su Agamben, Milano: Ledizioni, 2012 (with essays by B. Witte, V. Liska, L. Dell'Aia, R. Talamo,

E. Miranda, F. Recchia Luciani).

Derrida, Jacques. The Beast and the Sovereign, Volume 1. Ed. Michel Lisse, Marie-Louise Mallet, and Ginette Michaud.

Trans. Geoff Bennington. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009. 9196, 315334.

Dickinson, Colby. Agamben and Theology. London and New York: T&T Clark International, 2011.

Doussan, Jenny. "Time, Language, and Visuality in Agamben's Philosophy." Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

Downey, Anthony. Zones of Indistinction: Giorgio Agambens Bare Life and the Politics of Aesthetics, Third Text, issue 97,

2009.

Downey, Anthony. "Exemplary Subjects: Camps and the Politics of Representation", in "Giorgio Agamben: Legal, Political

and Philosophical Perspectives" London: Routledge, 2014. 119-142.

Fabbri, Lorenzo. "From Inoperativeness to Action: On Giorgio Agambens Anarchism" , "Radical Philosophy Review,"

Volume 4, Number 1, 2011.

Fabbri, Lorenzo. "Chronotopologies of the Exception. Agamben and Derrida before the Camps" , "Diacritics," Volume 39,

Number 3 (2009): 7795.

Galindo Hervs, Alfonso. Poltica y mesianismo. Giorgio Agamben. Biblioteca Nueva, Madrid, 2005.

Geulen, Eva. Giorgio Agamben zur Einfhrung. Hamburg: Junius Verlag, 2005.

Kishik, David. The Power of Life: Agamben and the Coming Politics. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2011.

LaCapra, Dominick. "Approaching Limit Events: Siting Agamben". In History in Transit: Experience, Identity, Critical Theory.

Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2004. 144194.

Mills, Catherine. The Philosophy of Giorgio Agamben. Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press, 2009.

Murray, Alex. Giorgio Agamben. London and New York: Routledge, 2010.

Murray, Alex and Jessica Whyte. The Agamben Dictionary. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2011.

Neal, Andrew W., Exceptionalism and the Politics of Counter-Terrorism: Liberty, Security and the War on Terror. Abingdon:

Routledge, 2010.

Norris, Andrew, ed. Politics, Metaphysics, and Death: Essays on Giorgio Agambens Homo Sacer. Durham, NC: Duke

University Press, 2005.

Ross, Alison, ed. The Agamben Effect. A special issue of the South Atlantic Quarterly, Volume 107, Number 1, Winter

2008.

Salzani, Carlo, Introduzione a Giorgio Agamben, Il Nuovo Melangolo, 2013.

Snoek, Anke. Agamben's Joyful Kafka: Finding Freedom Beyond Subordination. New York: Bloomsbury, 2012.

Tagma, Halit Mustafa. "Homo Sacer vs. homo soccer mom: Reading Agamben and Foucault in the war on terror" ,

Alternatives: Local, Global, Political. Volume: 34, No: 4, pp: 407435, 2009.

Tasis, Theofanis. "Politics of the Senses: On vision and hearing in Hannah Arendt's "Vita activa" , in: Axel Michaels,

Christoph Wulf (eds.), Exploring the Senses South Asian and European Perspectives on Rituals and Performativity

(Chapter 20), Routledge India, 2012.

Wall, Thomas Carl. Radical Passivity: Lvinas, Blanchot, and Agamben. New York: State University of New York Press,

1999.

Watkin, William. Literary Agamben: Adventures in Logopoiesis. London and New York: Continuum, 2010.

Zartaloudis, Thanos. Giorgio Agamben: Power, Law and the Uses of Criticism. London and New York: Routledge, 2010.

External links [edit]

Text [edit]

English

Quotations related to Giorgio Agamben at Wikiquote

Giorgio Agamben Faculty Page at European Graduate School

Catherine Mills. Giorgio Agamben - Entry at Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Review of Agamben, Profanations , by Daniel Ross

On Giorgio Agamben's Profanations , by Mehdi Belhaj Kacem

Interview with Giorgio Agamben Life, A Work of Art Without an Author: The State of Exception, the Administration of

Disorder and Private Life

Review of State of Exception , by Brett Neilson

(English)/(Italian) The Ripe Fruit of Redemption , by Toni Negri

converted by Web2PDFConvert.com

"Get Rid Of Yourself" with Giorgio Agamben, by Bernadette Corporation.

Apparatus, Capture, Trace: Photography and Biopolitics in: Fillip. Fall 2011.

For a theory of destituent power . By Giorgio Agamben. Public lecture in Athens, 16.11.2013. Invitation and organization

by Nicos Poulantzas Institute and SYRIZA Youth.

What is a Destituent Power? By Giorgio Agamben (translated by Stephanie Wakefield). Environment and Planning D:

Society and Space 32(1), 6574.

French

"tat d'exception" de G. Agamben , by Sandra Salomon.

"L'tat d'exception ("State of Exception")" . Le Monde (France). 12 December 2002.

"Une biopolitique mineure ("A minor biopolitic", interview with Agamben)" . Vacarme. December 1999.

Italian

(Italian) filosofico.net Italian page dedicated to Agamben

Hebrew

Review of State of Exception , Yehouda Shenhav, Sfarim Haaretz, 23.11.2005.

Croatian

An Essay on Giorgio Agamben's Homo sacer , by Mario Kopi

Video lectures [edit]

Agamben, Giorgio. Pro memoria Ivan Illich. Bologna, 12/17/2012

Agamben, Giorgio. The Archaeology of Commandment. European Graduate School. 08/19/2011

Agamben, Giorgio. Oath and the Peculiar Force of Language. 1st lecture at European Graduate School. 08/17/2011

Agamben, Giorgio. The Oath and Language. 2nd lecture at European Graduate School. 08/17/2011

Agamben, Giorgio. The Form of the Commandment. 3rd lecture at European Graduate School. 08/17/2011

Agamben, Giorgio. The Archaeology of Commandment. 4th lecture at European Graduate School. 08/17/2011

Agamben, Giorgio. Animal, Man and Language. 5th lecture at European Graduate School. 08/17/2011

Agamben, Giorgio. Language, Media and Politics. 6th lecture at European Graduate School. 08/18/2011

Agamben, Giorgio. Gesture, or the Structure of Art. 7th lecture at European Graduate School. 08/18/2011

Agamben, Giorgio. An Archaeology of Will. 8th lecture at European Graduate School. 08/18/2011

Agamben, Giorgio. Will, Responsibility, and the Free Subject. 9th lecture at European Graduate School. 08/18/2011

Agamben, Giorgio. Alternative Ethics. 10th lecture at European Graduate School. 08/19/2011

Agamben, Giorgio. Paul, Augustine, and the Will. 11th lecture at European Graduate School. 08/19/2011

Agamben, Giorgio. Religious Movements . Universit Paris 8. April 8, 2011. (French)

Agamben, Giorgio. Naissance des rgles. Rgles monastiques, pauvret et forme de vie de Basile Franois .

Universit Paris 8. March 18-April 8, 2011. (French)

Agamben, Giorgio. The Birth of Rules . Universit Paris 8. April 1, 2011. (French)

Agamben, Giorgio. I Will, I Command . Universit Paris 8. February 18, 2011. (French)

Agamben, Giorgio. "Je le veux, je lordonne!" Archologie du commandement et de la volont . Universit Paris 8.

January 14-February 18, 2011. (French)

Agamben, Giorgio. Nacktheiten. 3Sat Kulturzeit, German TV. December 3, 2010 (German)

Agamben, Giorgio. Jsus, Messie d'Isral? (later published as La Chiesa e il Regno). Notre Dame de Paris. March 3,

2009. (French)

Agamben, Giorgio. Aristotle's De Anima and the Division of Life. European Graduate School. 2009

Agamben, Giorgio. Forms of Power. European Graduate School. 2009

Agamben, Giorgio (and Judith Butler). Eichmann, Law and Justice. European Graduate School. 2009

Agamben, Giorgio. The Problem of Subjectivity. European Graduate School. 2009

Agamben, Giorgio. Liturgia and the Modern State. European Graduate School. 2009

Agamben, Giorgio. The Process of the Subject in Michel Foucault. European Graduate School. 2009

Agamben, Giorgio. Literature and the Paradox of Monasticism. European Graduate School. 2009

Agamben, Giorgio. The Relation of Rule and Life. European Graduate School. 2009

Agamben, Giorgio. A Genealogy of Monasticism. European Graduate School. 2009

Agamben, Giorgio. The Sacrifice in Liturgy. European Graduate School. 2009

Agamben, Giorgio. Desubjectivity and the Effect. European Graduate School. 2009

Agamben, Giorgio. Profanations UNSAM, 11/21/2008.

Agamben, Giorgio. On Contemporaneity. European Graduate School. 2007

Agamben, Giorgio. The Power and the Glory. Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS). 01/11/2007

Agamben, Giorgio. What is a Dispositive? European Graduate School. 2005

Agamben, Giorgio. The State of Exception Der Ausnahmezustand. European Graduate School. 2003.

Agamben, Giorgio. What is a Paradigm. European Graduate School. 2002

converted by Web2PDFConvert.com

Privacy policy About Wikipedia Disclaimers Contact Wikipedia Developers Mobile view

This page was last modified on 23 May 2014 at 04:55.

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional terms may apply. By using this site, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy

Policy. Wikipedia is a registered trademark of the Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., a non-profit organization.

[hide] v t e

Audio lectures [edit]

Agamben, Giorgio. Archologie du commandement et de la volont . Universit Paris 8. April 5, 2011. (French)

Agamben, Giorgio. What is a Commandment? Kingston University London. 2011

Art film [edit]

Agamben was interviewed in the 2003 "video-film-tract" Get Rid Of Yourself , contributing to an analysis of the Black Bloc

and anarchist participation in the 2022 July 2001 G8 Summit in Genoa, Italy.

Continental philosophy

Philosophers

Theodor W. Adorno Giorgio Agamben Louis Althusser Hannah Arendt Joxe Azurmendi Gaston Bachelard

Alain Badiou Roland Barthes Georges Bataille Jean Baudrillard Zygmunt Bauman Simone de Beauvoir

Henri Bergson Maurice Blanchot Pierre Bourdieu Judith Butler Albert Camus Ernst Cassirer

Cornelius Castoriadis Gilles Deleuze Jacques Derrida Hubert Dreyfus Terry Eagleton Johann Fichte

Michel Foucault Frankfurt School Hans-Georg Gadamer Antonio Gramsci Jrgen Habermas Georg Hegel

Martin Heidegger Edmund Husserl Roman Ingarden Karl Jaspers Immanuel Kant Sren Kierkegaard

Alexandre Kojve Leszek Koakowski Jacques Lacan Franois Laruelle Claude Lvi-Strauss Emmanuel Levinas

Gabriel Marcel Maurice Merleau-Ponty Friedrich Nietzsche Paul Ricur Avital Ronell Jean-Paul Sartre

Friedrich Schelling Carl Schmitt Arthur Schopenhauer Peter Sloterdijk Slavoj iek more...

Theories

German idealism Hegelianism Critical theory Psychoanalytic theory Existentialism Structuralism Postmodernism

Poststructuralism

Concepts

Angst Authenticity Being in itself Boredom Dasein Diffrance Difference Existential crisis Facticity

Intersubjectivity Ontic Other Self-deception Trace more...

Related articles Kantianism Phenomenology Hermeneutics Deconstruction

Category Task force Stubs Discussion

Authority control

WorldCat VIAF: 112062695 LCCN: n81077118 ISNI: 0000 0001 2148 0099 GND: 119293439 SUDOC:

026678497 BNF: cb11888160d (data) NDL: 00724041 NKC: mzk2002148169

Categories: 1942 births Critical theorists Living people People from Rome 20th-century Italian philosophers

Italian political theorists Academics of the Warburg Institute Political philosophers Emergency laws

University of Dsseldorf alumni University of Verona faculty University of California, Berkeley faculty

Northwestern University faculty European Graduate School faculty Walter Benjamin scholars

converted by Web2PDFConvert.com

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- En Wikipedia Org Wiki Grecia CantonDocument4 pagesEn Wikipedia Org Wiki Grecia CantonanfilbiblioPas encore d'évaluation

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- En Wikipedia Org Wiki TesauroDocument2 pagesEn Wikipedia Org Wiki TesauroanfilbiblioPas encore d'évaluation

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- En Wikipedia Org Wiki Oriol JunquerasDocument14 pagesEn Wikipedia Org Wiki Oriol JunquerasanfilbiblioPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Es Scribd Com Archive Plans Doc 358979573 Metadata 7B 22contDocument3 pagesEs Scribd Com Archive Plans Doc 358979573 Metadata 7B 22contanfilbiblioPas encore d'évaluation

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Es Scribd Com Upload Document Archive Doc 39805691 Escape FaDocument2 pagesEs Scribd Com Upload Document Archive Doc 39805691 Escape FaanfilbiblioPas encore d'évaluation

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- En Wikipedia Org Wiki Josep BorrellDocument8 pagesEn Wikipedia Org Wiki Josep BorrellanfilbiblioPas encore d'évaluation

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- En Wikipedia Org Wiki RPGDocument4 pagesEn Wikipedia Org Wiki RPGanfilbiblioPas encore d'évaluation

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- En Wikipedia Org Wiki Agust C3 ADn Garc C3 ADa CalvoDocument19 pagesEn Wikipedia Org Wiki Agust C3 ADn Garc C3 ADa CalvoanfilbiblioPas encore d'évaluation

- Dzone Guidetowebdevelopment 2016Document30 pagesDzone Guidetowebdevelopment 2016anfilbiblioPas encore d'évaluation

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- En Wikipedia Org Wiki Agesilaus IIDocument12 pagesEn Wikipedia Org Wiki Agesilaus IIanfilbiblioPas encore d'évaluation

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- En Wikipedia Org Wiki Hermogenes PhilosopherDocument3 pagesEn Wikipedia Org Wiki Hermogenes PhilosopheranfilbiblioPas encore d'évaluation

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- En Wikipedia OrgDocument9 pagesEn Wikipedia OrganfilbiblioPas encore d'évaluation

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- En Wikipedia Org Wiki HermogenesDocument2 pagesEn Wikipedia Org Wiki HermogenesanfilbiblioPas encore d'évaluation

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- En Wikipedia Org Wiki ShambalaDocument3 pagesEn Wikipedia Org Wiki ShambalaanfilbiblioPas encore d'évaluation

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Microservices in Java: "Using Hazelcast With Microservices"Document6 pagesMicroservices in Java: "Using Hazelcast With Microservices"Aditya ChendwankarPas encore d'évaluation

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Dzone Refcard129 RestfularchitectureupdatedDocument7 pagesDzone Refcard129 RestfularchitectureupdatedanfilbiblioPas encore d'évaluation

- Dzone Refcard Hibernatesearch UpdateDocument8 pagesDzone Refcard Hibernatesearch UpdateanfilbiblioPas encore d'évaluation

- Polanyi PDFDocument33 pagesPolanyi PDFMaría José CárdenasPas encore d'évaluation

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Apel K. O. - From Kant To Peirce PDFDocument8 pagesApel K. O. - From Kant To Peirce PDFanfilbiblioPas encore d'évaluation

- Prisa: History and ProfileDocument2 pagesPrisa: History and ProfileanfilbiblioPas encore d'évaluation

- JsDocument14 pagesJsanfilbiblioPas encore d'évaluation

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- En Wikipedia OrgDocument1 pageEn Wikipedia OrganfilbiblioPas encore d'évaluation

- Prisa: History and ProfileDocument2 pagesPrisa: History and ProfileanfilbiblioPas encore d'évaluation

- YyDocument9 pagesYyanfilbiblioPas encore d'évaluation

- Pedro (Footballer, Born July 1987) : Club CareerDocument4 pagesPedro (Footballer, Born July 1987) : Club CareeranfilbiblioPas encore d'évaluation

- ArenDocument3 pagesArenanfilbiblioPas encore d'évaluation

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- En Wikipedia OrgDocument9 pagesEn Wikipedia OrganfilbiblioPas encore d'évaluation

- TrabajoDocument2 pagesTrabajoanfilbiblioPas encore d'évaluation

- En Wikipedia OrgDocument7 pagesEn Wikipedia OrganfilbiblioPas encore d'évaluation

- AthenaDocument6 pagesAthenaanfilbiblioPas encore d'évaluation

- All About WomenDocument0 pageAll About WomenKeith Jones100% (1)

- English Test 4 PDFDocument3 pagesEnglish Test 4 PDFsofiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Related Documents - CREW: Department of State: Regarding International Assistance Offers After Hurricane Katrina: Bahamas AssistanceDocument16 pagesRelated Documents - CREW: Department of State: Regarding International Assistance Offers After Hurricane Katrina: Bahamas AssistanceCREWPas encore d'évaluation

- Attorney Email List PDFDocument5 pagesAttorney Email List PDFeric considine100% (1)

- New Member Orientation: Rey F. Bongao RC San Pedro South, D-3820Document50 pagesNew Member Orientation: Rey F. Bongao RC San Pedro South, D-3820Sy DamePas encore d'évaluation

- SF 2 Daily Attendance JUNEDocument2 pagesSF 2 Daily Attendance JUNEMark PadernalPas encore d'évaluation

- Consequences of Power Distance Orientation in Organisations: Vision-The Journal of Business Perspective January 2009Document11 pagesConsequences of Power Distance Orientation in Organisations: Vision-The Journal of Business Perspective January 2009athiraPas encore d'évaluation

- SocratesDocument9 pagesSocratesKathHinlogPas encore d'évaluation

- 036-Manila Electric Company v. Secretary of Labor, G.R. No. 127598, Jan 27, 1999Document25 pages036-Manila Electric Company v. Secretary of Labor, G.R. No. 127598, Jan 27, 1999Jopan SJPas encore d'évaluation

- Pride and PrejudiceDocument19 pagesPride and PrejudiceBogdan Si Alexa PaunPas encore d'évaluation

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- T04821Document615 pagesT04821adie rathiPas encore d'évaluation

- R.A. 9512Document11 pagesR.A. 9512Marc Keiron Farinas33% (3)

- Victim or Survivor TerminologyDocument2 pagesVictim or Survivor TerminologyRohit James JosephPas encore d'évaluation

- 4 People Vs Pambid G.R. No. 124453. March 15, 2000Document2 pages4 People Vs Pambid G.R. No. 124453. March 15, 2000EunicePas encore d'évaluation

- Single Attribute Utility TheoryDocument39 pagesSingle Attribute Utility TheorygabiPas encore d'évaluation

- Affidavit of Undertaking To Maintain The Productivity of The LandDocument3 pagesAffidavit of Undertaking To Maintain The Productivity of The LandAlexandra CastañedaPas encore d'évaluation

- James Mill A BiographyDocument500 pagesJames Mill A Biographyedwrite5470Pas encore d'évaluation

- Kida vs. SenateDocument11 pagesKida vs. SenateCassandra LaysonPas encore d'évaluation

- 10 2307@3174808 PDFDocument23 pages10 2307@3174808 PDFMaira Suárez APas encore d'évaluation

- Week 7 - The Influence of School CultureDocument22 pagesWeek 7 - The Influence of School CultureSaya Jira100% (1)

- Intro For Guest SpeakerDocument2 pagesIntro For Guest Speakerdatabasetechnology collegePas encore d'évaluation

- CHAPTER 5: Quiz On FreedomDocument19 pagesCHAPTER 5: Quiz On FreedomCatalina AsencionPas encore d'évaluation

- UntitledDocument10 pagesUntitledBrian ChukwuraPas encore d'évaluation

- Class Se Sem Iv Academic Year:2021-22Document55 pagesClass Se Sem Iv Academic Year:2021-22utkarsha sonekarPas encore d'évaluation

- Xiii. Aleatory ContractsDocument21 pagesXiii. Aleatory ContractsArmi100% (1)

- Exodus vs. BiscochoDocument2 pagesExodus vs. BiscochoJuna Aimee FranciscoPas encore d'évaluation

- Consti CasesDocument117 pagesConsti CasesNathNathPas encore d'évaluation

- Our BapuDocument69 pagesOur BapuaPas encore d'évaluation

- Polkinghorne V HollandDocument2 pagesPolkinghorne V HollandDavid LimPas encore d'évaluation

- Happiness Ben DykesDocument7 pagesHappiness Ben DykesAnonymous pgWs18GDG1100% (1)