Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Food Safety Regulations - TURKYE

Transféré par

Radu Victor TapuDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Food Safety Regulations - TURKYE

Transféré par

Radu Victor TapuDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Food Safety Regulations

and Export Responses of

Developing Countries:

The Case of Turkeys Fig

and Hazelnut Exports

by

Cemal Atici

1

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

FAO COMMODITY AND TRADE POLICY

RESEARCH WORKING PAPER No. 39

1

Economist, Trade and Markets Division. I would like to thank seminar participants at FAO-EST for their

valuable comments and Pascal Liu for his useful review and suggestions. All remaining errors are mine.

ii

The designations employed and the presentation of material in this

information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever

on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

(FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city

or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or

boundaries. The mention of specifc companies or products of manufacturers,

whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have

been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar

nature that are not mentioned.

The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and

do not necessarily refect the views or policies of FAO.

FAO 2013

FAO encourages the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this

information product. Except where otherwise indicated, material may be

copied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teaching

purposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services, provided that

appropriate acknowledgement of FAO as the source and copyright holder is

given and that FAOs endorsement of users views, products or services is not

implied in any way.

All requests for translation and adaptation rights, and for resale and other

commercial use rights should be made via www.fao.org/contact-us/licence-

request or addressed to copyright@fao.org.

FAO information products are available on the FAO website (www.fao.org/

publications) and can be purchased through publications-sales@fao.org.

iii

TABLE OF Contents

ABSTRACT iv

1. INTRODUCTION 1

2. FOOD SAFETY REGULATIONS AND EXPORT PERFORMANCE 3

3. TURKEYS EXPORT PERFORMANCE IN FIG AND HAZELNUT EXPORTS 4

4. EMPIRICAL ANALYSIS AND DATA 8

5. RESULTS 10

6. CONCLUSIONS 12

REFERENCES 13

iv

Abstract

Food safety standards are gaining importance as trade regulations. These regulations affect exports in

three main ways depending on the capacities of exporting countries: trade-impeding effects, neutral

effects, and catalyst effects. Although previous studies confrm the trade impeding effect of regulations,

recent studies show that strict regulations can stimulate developing countries through the scale effect

as in the case of some African exporters. In addition, developing countries can beneft from extensive

governmental guidance in terms of coping with standards. Harmonization of standards as a requirement

of economic integration also leads to improvement in export performance. This study outlines the

interaction between regulation and export responses by examining the change in export fow from

Turkey to the EU partners after food safety regulations of the EU were put into effect, drawing policy

implications in terms of food safety-export performance interaction. The empirical results show that

the harmonization of EU food safety regulation in 2002 positively infuenced hazelnuts exports, while

the EU food safety regulation in 2007 reduced the volume of fg exports. The rise in export unit values

indicates that Turkish primary food products responded to the EU food safety regulation with quality

improvements accompanied by higher unit prices.

Keywords: Food Safety Standards, Trade, Agriculture, Developing Countries, Turkey, EU

1

1. Introduction

Food safety regulations are gaining importance as trade instruments, and many industrialized countries

are implementing restrictive limits on food safety standards that can prevent imports (FAO, 2004; WTO,

2013). As an obligation of the WTO (2012), conventional trade barriers are being reduced, but food

safety regulations and standards are becoming considerable tools as alternative trade barriers. The EU

set maximum limits on its afatoxin within the Union in 1997 (EC-194/97) with some amendments

in 1998 (98/53/EC) as an initiative for harmonization. The EU harmonized its regulations in 2001

(EC/466/2001); these became effective in 2002. Additional regulations (2002/80/EC and 2002/679/

EC) that came into force in 2002 require a health certifcate for dried fruits from Turkey (European

Commission, 2012a). Another restrictive regulation that came into force in 2007 (2007/459/EC) requires

exporting frms of fgs and hazelnuts to obtain an afatoxin certifcate, in addition to previous regulations,

from offcial laboratories before shipment, which adds extra processing costs. This certifcation provides

information indicating that the related commodity is free of harmful toxins based on the specifcations

in the related regulation. Although a large variety of food safety regulations exist, the most prominent

and internationally recognized one is afatoxin limits for primary food products (FAO, 2004). Figure 1

presents the afatoxin limits in selected countries. The afatoxin standards are quite restrictive for EU

members, less restrictive in the U.S, and least restrictive in many of the developing countries, with the

exceptions of some such as Turkey, Chile, Egypt, and Vietnam.

The impact of food safety regulations on trade performance varies. Chen et al. (2008) found that

food safety standards imposed by importing countries had a negative effect on Chinas agricultural

exports. Similarly, it was shown that developed countries food safety standards had a deterring impact

on processed food exports of developing countries (Jongwanich, 2009). However, Maertens and

Swinnen (2008) found that Senegals vegetable exports grew signifcantly after food safety standards

were adopted due to a shift of production from smallholders to large-scale production. Another study

carried out by Anders and Caswell (2009) determined that the US standard (HACCP) has a negative

impact on developing countries but a positive impact on developed countries for US seafood imports.

This highlights the catalyst effect, which describes an exporting countrys ability to cope with restrictive

regulations. On the other hand, export performance is found to be positively related with standards

certifcation (Masakure et al., 2009). In addition, some evidence demonstrates that some countries

are utilizing high quality and safety standards to reposition themselves in global markets (Jaffee and

Henson, 2004). However, for better understanding of the impacts of private standards on developing

countries further research is necessary on particular industries and in specifc countries (Dankers, 2007).

This study will outline the interaction between regulation and export responses based on the theory

and research results. As a case study, this paper aims to examine the change in export fow from Turkey

to the EU partners after the food safety regulations of the EU are put into effect, and draws policy

implications in terms of food safety-export performance interaction.

2

F

i

g

u

r

e

1

.

A

v

e

r

a

g

e

a

f

a

t

o

x

i

n

l

i

m

i

t

s

f

o

r

u

n

p

r

o

c

e

s

s

e

d

f

o

o

d

i

n

s

e

l

e

c

t

e

d

c

o

u

n

t

r

i

e

s

,

2

0

0

4

(

m

y

c

o

t

o

x

i

n

b

1

,

l

i

m

i

t

g

/

k

g

)

S

o

u

r

c

e

:

C

o

m

p

i

l

e

d

f

r

o

m

F

A

O

,

2

0

0

4

3

2. Food Safety Regulations and Export

Performance

Food safety regulations have three main effects: the trade-impeding effect, the neutral effect, and the

catalyst effect. The trade-impeding effect occurs due to the negative impact of regulations, which leads

to trade distortion against the exporters of food products. The neutral effect mostly occurs in developed

exporting countries, where they can comply with restrictive regulations because of their research and

development expenditures and high level of standards. The catalyst effect occurs when regulations force

exporting countries to invest more in a specifc market and increase their share in world trade. Such

an effect also occurs when developed countries replace the exports of negatively affected developing

countries in world markets. The catalyst effect is composed of research and development (R&D), scale

effect, institutional effect, and efforts for harmonization. Most of the R&D is observed in the markets of

developed countries. The scale effect can be observed in emerging markets, where frm size is increased

in an effort to comply with restrictive regulations. The institutional effect is caused by institutional

governance and guidance aimed at domestic exporting frms providing market information and technical

assistance. The harmonization effects occur when a candidate country aims to join an economic union

and harmonizes its regulations according to the principles of the union (Figure 2).

Food Safety

Regulations and

Export Performance

Trade-Impeding

Effect

Neutral Effect Catalyst Effect

R&D Scale Effect

Institutional Effect

and Harmonization

Figure 2. Food Safety Regulation and Export Performance Interaction

4

3. Turkeys Export Performance in Fig and Hazelnut

Exports

Afatoxin standards are especially important for primary agricultural products such as dried fruit and

nuts (FAO, 2004). Turkey is a major world producer and exporter of dried fgs and hazelnuts (FAOSTAT,

2012; Comtrade, 2012). Turkey ranks number one in the world for fgs production (254 838 MT, 24%

of world production) and hazelnuts production (600 000 MT, 70% of world production) (FAOSTAT,

2012). In addition, Turkey ranks frst in the export of dried fgs (58 252 MT, 63 % of world export)

and shelled hazelnuts (149 605 MT, 76 % of world export) in the world markets. The EU is a major

market for Turkish food exports: Turkey exports 60% and 67% of fgs and hazelnuts, respectively,

to the EU market (Comtrade, 2012). Turkeys agricultural relationship with the EU is based on the

Ankara Agreement, signed in 1963, and the Additional Protocol of 1970. In accordance with the

Ankara Agreement, the EU made unilateral concessions in the form of tariff rate quotas and lower

tariffs for some Turkish agricultural products (tobacco, raisins, fgs, and nuts). The Additional Protocol

established a bilateral preferential system that enables lower tariffs for agricultural products. The 1995

Customs Union agreement eliminated the industry share in processed agricultural products but kept

the agricultural share (e.g., milk, sugar, and cereals), and the tariffs for unprocessed ones were kept

bilaterally (European Commission, 2012b; MARA, 2009). In addition, the EU keeps some seasonal

tariffs and non-tariff measures such as food safety standards (UPMFT, 2008). Seasonal variations in

tariffs are among the tools of protection for fruit and vegetables. Ad valorem and specifc duties as well

as entry prices vary throughout the year, so customs duties are higher during the production period in the

EU to protect domestic producers (Emlinger et al. 2008).

The change in Turkeys export values of fgs and hazelnuts are presented in Figures 3 and 4. The

total value of fg exports increased from US$ 78 million in 1995 to almost US$ 180 million in 2011.

The value of fg exports decreased slightly in 2000 but increased after that due to higher prices. Total

hazelnut exports increased from US$ 589 million to over US$ 1 billion in 2011. Although the values

of exports of fgs and hazelnuts to the EU increased over the years, the share of the EU in total exports

decreased from 74% to 60% for fgs and from 83% to 67% for hazelnuts in the same period.

The bilateral export data (Comtrade, 2012) reveal that the quantity exported to the EU was 21 000

MT and 153 000 MT in 1995 and 22.000 MT and 93 574 MT in 2011 for fgs for hazelnuts, respectively

(Figures 5-7). Although the volume of fg exports did not vary much, the value of exports to the EU

increased by 89 % between 1995 and 2011. The hazelnut export volume to the EU decreased by 38%

over the decade, but the total value of exports increased by 44%. This price increase stems from increase

in unit export value.

As shown in Figures 5 to 8, the unit export value of fgs increased from around US$ 2000 per tonne to

over US$ 3300 in 2011 (more than 50%). After 2002, export volume and value rose, unit export value

were stable or slightly up. The volume fell in 2006-2007, but partly recovered in 2008-2010, and the

unit export value almost doubled compared to pre-2007 average. On the other hand, the average unit

prices for hazelnuts doubled, from US$ 3500 in 1995 to over US$ 7400 per tonne in 2011. After 2002,

unit export value and export value rose strongly while volume remained relatively stable. After 2007

volume, value and unit export value remained relatively stable.

5

Figure 3. Turkeys Figs Export to the World and the EU, US$ and Share of the EU, %.

Source: Comtrade, 2012

Figure 4. Turkeys Hazelnuts Export to the World and the EU, US$ and Share of the EU, %.

Source: Comtrade, 2012

6

Figure 5. Change in Volume and Value of Figs Exports of Turkey to the EU

Figure 6. Unit Export Value of Turkeys Figs Export to the EU, US$/MT

7

Figure 7. Change in Volume and Value of Hazelnuts Exports of Turkey to the EU

Figure 8. Unit Export Value of Turkeys Hazelnuts Export to the EU, US$/MT

8

The higher unit value of fg exports can be attributed to factors such as quality increase, while the

increase in the unit value of hazelnut exports was caused by variations in production volume, lower

stock, and higher market prices after policy changes toward more free market pricing (AEPDI, 2012).

However, cost of quality improvements may also be an important factor that contributes to the value of

exports.

4. Empirical Analysis and Data

In order to examine the impact of afatoxin standards, an export fow model is employed utilizing the

panel of unilateral export fow data between 1995 and 2011. Developing countries are more interested

in the factors that determine their unilateral export fow in order to avoid balance of payment problems

rather than the determinants of bilateral trade fow. Recently, however, some studies have utilized single-

country models (Summary, 1989; Sohn, 2005; Lissovolik and Lissovolik, 2006).

In order to avoid the omitted variable bias (Matyas, 1997; Anderson and Van Wincoop, 2003) caused

by unobservable multilateral resistances, importer effects were included in the model.

Thus the equations can be represented as

=

se 1, otherwi

n rtificatio latoxin Ce 2007, Af 0, before

EUReg2007

jt

(2)

=

se 1, otherwi

ulation atoxin Reg ion of Afl Harmonizat 2002, before 0,

EUReg2002

jt

(1) EUReg2007 EUReg2002

rexc index lnexp lnprod lngdpc lngdpc lnE

ijt jt 7 jt 6

it 5 ijt 4 it 3 jt 2 1 it 1 j TRjt

(3) index lnexp lngdpc lnE

ijt ijt jt 2 ijt 1 j TRjt

where E

TRjt

is export fow in terms of volume from Turkey to partner EU countries;

j

denotes importer-

specifc fxed effects

ijt

denotes

time effect; gdpc

it-1

, gdpc

jt

, prod

it

, exp-index

jt

, rexc

it

, and EUReg

jt

denote

home countrys income per capita in previous year, partner countries income per capita, domestic

production level of specifed commodities, export price index of specifed commodities, real exchange

rate of Turkey, and EU regulation dummies respectively. In time fxed effect estimation of the model

multiplicative form of real incomes were utilized in order to avoid multicollinearity. Since the focus of

this regression is the effectiveness of the EUs regulations, a regulation dummy is estimated such that

a dummy variable (EUReg2002) representing harmonization of EU regulations in afatoxins takes the

value of 0 before 2002 and 1 otherwise. The EUReg2007 aims to capture the effect of the additional

regulation that requires the afatoxin certifcate in addition to the health certifcate for imported nuts and

9

fgs. In addition, a panel Chow test is performed to determine whether there is a structural change in

export fow after 2002 and 2007.

The income variable impacts the economic capacity of trade; thus, the GDPs of partner countries

positively impact trade fows. The effects of conventional trade fow variables such as GDPs of partner

countries on trade fow were signifcant in most studies (Oguledo and Macphee, 1994). Regulations

on afatoxin limits may serve as a kind of technical barrier to trade and are expected to have a negative

effect on export fow as found in some of the literature (Chen et al., 2008; Jongwanich, 2009). However,

other researchers found non-negative impacts for some countries (Maertens and Swinnen, 2008; Anders

and Caswell, 2009).

The study utilizes data over the period of 1995 to 2011. Based on the consistent data set and to

exclude the new member bias that causes the rise in exports, the estimation includes 11 members for

the fg regression (Austria, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain,

Sweden, and United Kingdom) and 12 members (11 partners plus Greece) for the hazelnut regression.

The data used in the study for 12 partner countries come from various sources. Real GDPs and exchange

rate data come from the World Bank (2012). The hazelnut and fg export data in terms of volume are

from Comtrade (2012), based on HS classifcation. Production data are from FAOSTAT (2012). The

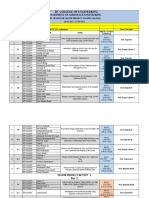

descriptive statistics of the data used in this study are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics of the Datra Used in the Study

Mean St Deviation Min. Max.

Figs Export (volume, MT)

N=187

2976 3161 37 11499

GDP

i

3.05467E11 6.12E10 2.18E11 4.22E11

GDP

j

7.15E11 6.37E11 9.52E10 2.13E12

Prod

i

258415 26700 205067 300000

Exp-index

ij

123 52.66 71.49 297.26

RExc

i

0.20 0.24 0.08 0.81

EUReg2002 0.58 0.49 0 1

EUReg2007 0.29 0.45 0 1

Hazelnuts Export (volume, MT)

N=204

8526 15175 5 87188

GDP

i

3.05467E11 6.12E10 2.18E11 4.22E11

GDP

j

6.67E11 6.30E11 9.52E10 2.13E12

Prod 529281 105499 350000 800791

Exp-index

ij

148 56.29 64.72 302.77

RExc

i

0.20 0.24 0.08 0.81

EU-Reg2002 0.58 0.49 0 1

EU-Reg2007 0.29 0.45 0 1

10

5. Results

The results of the panel regression are presented in Table 2. We cannot utilize the full set of time

dummies here because of the inclusion of time variant but partner country-fxed regulation dummies.

Considering the various control variables and model selection criteria, three models were estimated

for each commodity. As shown, the lagged value of real GDP per capita of Turkey is positive and

signifcant for fgs but insignifcant for hazelnuts. The fndings indicate that a rise in real income in

previous year positively affects the export capacity of the fgs. The explanation for insignifcant home

income for the exports of hazelnut is twofold: frst, the increase in real income in Turkey might lead

to an increased level of domestic consumption of that commodity; second, increased real income leads

to higher capacity for trade fow with non-EU partners. The partner country income is positive and

signifcant in model 2 only for the volume of fg exports but negative for the volume of hazelnut exports.

The explanation for negative partner income for the volume of hazelnut exports can be attributed to the

relatively low level of growth in the EU members in the last decade. The domestic supply capacity of

both commodities were found to be signifcant underlying the fact that export of these commodities are

related to the domestic supply fuctuations, especially for the case of fgs. Export price index is found to

be negative and signifcant for both commodities implying that rise in real unit prices will deter export.

The appreciation of Turkish Lira has no effect on the volume exports as refected by the parameter value

of the real exchange rate variable.

The impact of EUReg2002 shows that Turkish hazelnut exports are higher by [exp (0.17)-1] = 18

% after the 2002 regulation. Although fg exports are lower after the harmonization in model 2, after

controlling the year variables, the negative effect of harmonization becomes insignifcant. The impact of

EUReg2007 shows that Turkish fg exports are deterred after 2007, but hazelnut exports are not affected

signifcantly. When the fndings are compared with the Figure 5, it is interesting to note that the volume

of fg exports decreased slightly, immediately after the harmonization; however it performed well

afterwards especially in 2003 and 2006 before decreasing again in 2007 (year of afatoxin regulation).

The positive impact of harmonization on hazelnuts might stem from a few factors. First, harmonization

eliminated some very strict EU member countries regulations and therefore helped Turkish exporters

to beneft. Second, it might have caused the replacement of some ineffcient exporters that could not

comply with the regulations. On the other hand, it is clear that request for additional certifcation had a

negative effect on the volume of fg exports. The insignifcant panel Chow test statistics indicate that

there is no structural change in Turkeys food export to partner EU countries in real terms after the food

safety regulations came into effect. Based on the panel data estimates, food safety standards have had a

signifcant deterring impact on the volume of Turkish fg exports but no negative effect on the volume

of hazelnut exports.

The time effect estimation that utilizes the time dummies is presented in Table 3. This estimation

includes only the multiplicative form of the GDP per capitas and export price index variables, because

inclusion of full-year dummies does not allow for estimation of regulation dummies that are time-variant

but fxed across countries. The year dummies show that export fow of fgs decreased signifcantly

after 2002 and 2007 compared to the base year. However, the same negative effect is not observed for

the hazelnuts estimation. These results imply that hazelnut exports complied with the regulations and

performed better compared to fg exports.

11

Variables Figs Hazelnuts

[1] [2] [3] [1] [2] [3]

lngdpc

it-1

1.80

(3.71***)

- -

-0.57

(-0.65)

- -

lngdpc

jt

0.72

(1.13)

1.07

(2.60**)

0.86

(1.26)

-1.38

(-1.66*)

-1.83

(-3.24***)

-1.40

(-1.67*)

lnprod

it

0.53

(2.05**)

0.59

(2.30**)

0.47

(2.24**)

0.28

(1.40)

0.33

(1.99**)

-

lnexp-index

ijt

-0.43

(-3.01***)

- -

-0.23

(-1.67*)

-0.29

(-3.01***)

-0.37

(-2.77**)

lnrexc

it

-0.007

(-0.02)

- -

0.08

(1.65)

- -

EUReg2002

jt

-

-0.20

(-2.70**)

-0.13

(-0.99)

-

0.17

(1.80*)

0.26

(1.70*)

EUReg2007

jt

-

-0.15

(-2.37**)

-0.34

(-2.29**)

-

-0.09

(-1.22)

0.22

(1.21)

Year2002 - -

-0.15

(-1.60)

- -

0.15

(-1.31)

Year2007 - -

0.07

(1.17)

- -

0.13

(1.76*)

Trend

0.03

(1.95*)

-

0.0001

(0.0048)

- -

R

2

0.96 0.96 0.97 0.96 0.97 0.97

Chow Test (2002)

Chow Test (2007)

F(15,157) 0.16

F(15,157) 0.02

F(16, 172) 0.06

F(16, 172) 0.02

N 187 204

Table 2. Fixed Effects Panel Regression of Turkeys Figs and Hazelnuts Export to the EU

Note *, **, *** denote 10, 5, 1 percent signifcance, respectively. Numbers in parentheses are t values. Country-specifc fxed effects are not

reported.

[1-3] denote the model without regulation dummies, with regulation dummies, and with regulation dummies controlled by year effect

respectively.

12

Table 3. Time Fixed Effects Estimation of Turkeys Export Flow

Variables Parameter Estimate

Figs t value Hazelnuts t values

lngdpc

t

0.12 1.77* -0.26 -2.80**

lnexp-index - - -0.76 -1.79*

Year1996 -0.01 -0.14 -0.24 -1.39

Year1997 -0.12 -0.82 0.07 0.28

Year1998 -0.15 -0.86 0.26 0.95

Year1999 -0.05 -0.03 -0.02 -0.11

Year2000 -0.21 -1.02 0.12 0.42

Year2001 -0.20 -1.21 0.19 0.79

Year2002 -0.45 -2.25** 0.12 0.41

Year2003 -0.37 -1.67* 0.35 1.11

Year2004 -0.40 -1.41 0.98 2.04**

Year2005 -0.38 -1.14 1.44 2.13**

Year2006 -0.52 -1.34 1.32 2.20**

Year2007 -0.86 -2.03** 1.59 2.31**

Year2008 -0.96 -2.31** 1.43 2.19**

Year2009 -0.67 -1.96* 1.05 1.94*

Year2010 -0.83 -2.05** 1.47 2.30**

Year2011 -1.00 -2.19** 1.58 2.16**

R

2

0.97 0.97

LM (time efects) 2214*** 2207***

6. Conclusions

This study aimed to examine the interaction between food safety regulations and export performance

from the perspective of a developing country. Utilizing the panel data, this study analyzed the impact

of EU food safety regulations on Turkeys fg and hazelnut exports to the EU. The results show that

the 2002 regulation of afatoxin harmonization positively affected the volume of hazelnut exports. The

2007 regulation that requires certifcation signifcantly deterred fg exports; however, hazelnut exports

were not impeded after the regulations in terms of volume. Therefore, the impact of regulations varies

depending on the characteristics of the products. On the other hand, the regulations require processing

expenses, which are refected in the unit prices as can be seen in trade statistics (Comtrade, 2012).

Increased food safety may lead to a catalyst effect for some countries, because certain developing

countries react to new standards through new investments and research expenditures (Anders and

Caswell, 2009). Alternatively, the response of exporting companies to these increased standards may

result in consolidation and increased vertical coordination at different levels of the supply chain

(Maertens and Swinnen, 2008). The strategic responses to food safety standards vary across countries,

refecting capacities and perspectives on emerging requirements (Henson and Jaffee, 2008). In the

case of Turkey, the regulations in general have signifcantly deterred the volume of fg exports to the

EU (impeding effect). In terms of hazelnut exports, the instituitional adjustments and harmonization

attempts of food regulations with the EU may have had a trade facilitating catalyst effect given the

restrictive food standards, but at least these standards do not have barrier effects for some commodities.

13

Related institutions such as the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs (MARA, 2009) and the

Undersecretariat of Foreign Trade (UPMFT, 2012) provide guidance for exporting frms. As a candidate

country for full membership with the EU, Turkey has been harmonizing its regulations in line with the

accession negotiations (SGEUA, 2012). These types of institutional mechanisms may have a positive

effect on exporting frms to comply with the food safety regulations in export markets. The question

of why the institutional effect did not occur in the case of fg exports in the long run can be attributed

to the comparatively higher level of production and export of hazelnuts in Turkeys agricultural food

market. Therefore, higher levels of extension and guidance for the hazelnut sector are important factors

in maintaining export earnings. Another explanation might be the differences in processing capacities of

these two products in the marketing stages. Hazelnuts have a shell which protects them from chemical

residues while this is not the case for fgs. Thus, fgs are more vulnerable to afatoxin and only limited

quantities of fungicides can be used to treat them, otherwise there are too many residues left in the fruit

and it does not meet the regulation.

The value of exports to the EU performed well between 1995 and 2011 compared with the volume of

exports. Although this fnding can be used as an argument in favour of the export earnings, to what extent

these gains are transferred to the producers is a major concern. Especially in the marketing of fruits

and vegetables there are quite high marketing margins, and production and processing costs to comply

with the regulations might add extra cost for producers. The EU regulations that require certifcates for

imported products are refected as processing and managerial costs in export products. Therefore, it can

be argued that the standards increased the price of export commodities, resulting in higher prices for

EU consumers. On the other hand, given the fact that certain developed countries, such as the EU, have

more restrictive limits on food products than those specifed by the Codex Alimentarius (FAO, 2004)

and different limits are set at country levels (MARA, 2012), the simplifcation and harmonization of

regulations and more international collaboration are needed to further trade performance.

References

AEPDI, Agricultural Economics and Policy Development Institute (2012).Hazelnut Outlook, No: 1918.

Ankara.

Anders, S.M. and J.A. Caswell (2009). Standards as barriers versus standards as catalysts: assessing

the impact of HACCP implementation on US seafood imports. American Journal of Agricultural

Economics, 91:310-321.

Anderson, J. E. and E. van Wincoop (2003). Gravity with gravitas: a solution to the border puzzle.

American Economic Review, 93:170-192.

Chen, C., J. Yang, and C. Findlay (2008). Measuring the effect of food safety standards on Chinas

agricultural exports. Review of World Economics, 144:83-106.

Comtrade (2012). http://comtrade.un.org/db/.

Dankers, C. (2007). Private standards in the United States and European Union. Markets for fruits

and vegetables. FAO Commodity Studies, 3. Rome.

Emlinger, C., F. Jacquet, E.C. Lozza (2008). Tariffs and other trade costs: Assessing obstacles to

Mediterranean countries access to EU-15 fruit and vegetable markets. European Review of

Agricultural Economics, 35(4):409-438.

14

European Commission (2012a). Access to European Union Law.

http://eur-lex.europa.eu/en/index.htm

European Commission (2012b).

http://ec.europa.eu/enlargement/countries/detailed-country-information/turkey/index_en.htm

FAO (2004).Worldwide Regulations for Mycotoxins in Food and Feed in 2003, Rome, 2004.

FAOSTAT (2012). http://faostat.fao.org

Henson, S., and S. Jaffee (2008). Understanding developing country strategic responses to the

enhancement of food safety standards. World Economy, 31(4): 548-567.

Jaffee, S., and S. Henson (2004). Standards and agro-food exports from developing countries:

Rebalancing the debate. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 3348.

Jongwanich, J. (2009). The impact of food safety standards on processed food exports from

developing countries. Food Policy, 34: 447-457.

Lissovolik, B. and Y. Lissovolik (2006). Russia and gravity: the gravity of outsider status. IMF

Staff Papers. 53 (1):1-26.

Maertens, M., and J.F.M. Swinnen (2008). Trade, standards, and poverty: evidence from Senegal.

World Development, 37: 161-178.

MARA, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs (2009). www.tkib.gov.tr

Masakure, O., S. Henson, and J. Cranfeld (2009). Standards and exports performance in developing

countries: evidence from Pakistan. The Journal of International Trade and Economic Development,

18:385-419.

Matyas, L. (1997). The gravity model: some econometric considerations. The World Economy,

21(3):397-501.

SGEUA (2012). Republic of Turkey, Secretariat General for EU Affairs. http://www.abgs.gov.tr

Sohn, Chan-Hyun (2005). Does the gravity model explain South Koreas trade fow? The Japanese

Economic Review, 56(4):416-430

Summary, R.M. (1989). Political economic model of US bilateral trade. The Review of Economics

and Statistics, 71(1): 179-182.

UPMFT, Undersecretariat of the Prime Ministry for Foreign Trade (2012). www.dtm.gov.tr.

World Bank, WDI (2012). http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-development-indicators

WTO (2012). www.wto.org.

WTO (2013). Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures. http://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/sps_e/sps_e.htm

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Soil Atlas AFRICADocument178 pagesSoil Atlas AFRICARadu Victor Tapu100% (2)

- Unit 7: Anthropology: Q2e Listening & Speaking 4: Audio ScriptDocument6 pagesUnit 7: Anthropology: Q2e Listening & Speaking 4: Audio ScriptĐại học Bạc Liêu Truyền thông100% (1)

- Ahlstrom Naturemold Brochure enDocument3 pagesAhlstrom Naturemold Brochure enRadu Victor TapuPas encore d'évaluation

- US20120240461 PATENT - Vlado MoulisDocument6 pagesUS20120240461 PATENT - Vlado MoulisRadu Victor TapuPas encore d'évaluation

- Bas Rodenburg - The Role of Breeding and Genetics in Animal WelfareDocument38 pagesBas Rodenburg - The Role of Breeding and Genetics in Animal WelfareRadu Victor TapuPas encore d'évaluation

- Packaging For Organic Foods For WebDocument83 pagesPackaging For Organic Foods For WebRhesa PramuditaPas encore d'évaluation

- 26peaches - 2010 Unece Standard Ffv-26Document8 pages26peaches - 2010 Unece Standard Ffv-26Radu Victor TapuPas encore d'évaluation

- Evaluation of Walnut Cultivars in The Conditions of The Oltenia's Hill Area Regarding Functioning Potential V1.15.botumDocument10 pagesEvaluation of Walnut Cultivars in The Conditions of The Oltenia's Hill Area Regarding Functioning Potential V1.15.botumRadu Victor TapuPas encore d'évaluation

- Rowan Ranger Management 062014 enDocument24 pagesRowan Ranger Management 062014 enRadu Victor TapuPas encore d'évaluation

- Decorticated HazelnutsDocument11 pagesDecorticated HazelnutsRadu Victor TapuPas encore d'évaluation

- Romanian Cluster Policy and FDI - LeucutaDocument22 pagesRomanian Cluster Policy and FDI - LeucutaRadu Victor TapuPas encore d'évaluation

- ICC Global Trade and Finance Survey 2014Document144 pagesICC Global Trade and Finance Survey 2014Radu Victor Tapu100% (1)

- 16report2 ForestPolicyDocument202 pages16report2 ForestPolicyRadu Victor TapuPas encore d'évaluation

- FFIListUkraine hcm0067292Document5 pagesFFIListUkraine hcm0067292Radu Victor TapuPas encore d'évaluation

- Incoterm Quick Reference GuideDocument1 pageIncoterm Quick Reference GuideRadu Victor TapuPas encore d'évaluation

- Firme Italienesti de Consultant ADocument81 pagesFirme Italienesti de Consultant AMoldoveanu BogdanPas encore d'évaluation

- Georgia - Epi - Hazelnut Production Manual - 11 Hazelnut Production ManualDocument8 pagesGeorgia - Epi - Hazelnut Production Manual - 11 Hazelnut Production ManualRadu Victor TapuPas encore d'évaluation

- Research Concerning Estimation of Chocolate Quality With Methods of Sensorial AnalysesDocument4 pagesResearch Concerning Estimation of Chocolate Quality With Methods of Sensorial AnalysesRadu Victor TapuPas encore d'évaluation

- Cisco SDWAN Case Study Large Global WANDocument174 pagesCisco SDWAN Case Study Large Global WANroniegrokPas encore d'évaluation

- Wilcoxon Matched Pairs Signed Rank TestDocument3 pagesWilcoxon Matched Pairs Signed Rank TestDawn Ilish Nicole DiezPas encore d'évaluation

- Activity # 1 (DRRR)Document2 pagesActivity # 1 (DRRR)Juliana Xyrelle FutalanPas encore d'évaluation

- Pavement Design1Document57 pagesPavement Design1Mobin AhmadPas encore d'évaluation

- Sba 2Document29 pagesSba 2api-377332228Pas encore d'évaluation

- Principals' Leadership Styles and Student Academic Performance in Secondary Schools in Ekiti State, NigeriaDocument12 pagesPrincipals' Leadership Styles and Student Academic Performance in Secondary Schools in Ekiti State, NigeriaiqraPas encore d'évaluation

- Playful Homeschool Planner - FULLDocument13 pagesPlayful Homeschool Planner - FULLamandalecuyer88Pas encore d'évaluation

- Lecturenotes Data MiningDocument23 pagesLecturenotes Data Miningtanyah LloydPas encore d'évaluation

- B122 - Tma03Document7 pagesB122 - Tma03Martin SantambrogioPas encore d'évaluation

- Anatomy Anal CanalDocument14 pagesAnatomy Anal CanalBela Ronaldoe100% (1)

- Business Analytics Emphasis Course GuideDocument3 pagesBusiness Analytics Emphasis Course Guidea30000496Pas encore d'évaluation

- BNF Pos - StockmockDocument14 pagesBNF Pos - StockmockSatish KumarPas encore d'évaluation

- My Personal Code of Ethics1Document1 pageMy Personal Code of Ethics1Princess Angel LucanasPas encore d'évaluation

- Excon2019 ShowPreview02122019 PDFDocument492 pagesExcon2019 ShowPreview02122019 PDFSanjay KherPas encore d'évaluation

- PED003Document1 pagePED003ely mae dag-umanPas encore d'évaluation

- Presentation 11Document14 pagesPresentation 11stellabrown535Pas encore d'évaluation

- Carob-Tree As CO2 Sink in The Carbon MarketDocument5 pagesCarob-Tree As CO2 Sink in The Carbon MarketFayssal KartobiPas encore d'évaluation

- Electives - ArchitDocument36 pagesElectives - Architkshitiz singhPas encore d'évaluation

- Product CatalogsDocument12 pagesProduct Catalogscab666Pas encore d'évaluation

- Obesity - The Health Time Bomb: ©LTPHN 2008Document36 pagesObesity - The Health Time Bomb: ©LTPHN 2008EVA PUTRANTO100% (2)

- Thermally Curable Polystyrene Via Click ChemistryDocument4 pagesThermally Curable Polystyrene Via Click ChemistryDanesh AzPas encore d'évaluation

- Hamstring - WikipediaDocument21 pagesHamstring - WikipediaOmar MarwanPas encore d'évaluation

- Vendor Information Sheet - LFPR-F-002b Rev. 04Document6 pagesVendor Information Sheet - LFPR-F-002b Rev. 04Chelsea EsparagozaPas encore d'évaluation

- Application Activity Based Costing (Abc) System As An Alternative For Improving Accuracy of Production CostDocument19 pagesApplication Activity Based Costing (Abc) System As An Alternative For Improving Accuracy of Production CostM Agus SudrajatPas encore d'évaluation

- AntibioticsDocument36 pagesAntibioticsBen Paolo Cecilia RabaraPas encore d'évaluation

- Review1 ScheduleDocument3 pagesReview1 Schedulejayasuryam.ae18Pas encore d'évaluation

- AIA1800 Operator ManualDocument184 pagesAIA1800 Operator ManualZain Sa'adehPas encore d'évaluation

- Business Plan 3.3Document2 pagesBusiness Plan 3.3Rojin TingabngabPas encore d'évaluation

- QP December 2006Document10 pagesQP December 2006Simon ChawingaPas encore d'évaluation