Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Human Evolution

Transféré par

Jyotimoy Ggoi BHaiCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Human Evolution

Transféré par

Jyotimoy Ggoi BHaiDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Human evolution

Human evolution is about the origin of human beings. All humans belong to the same

species, which has spread from its birthplace in Africa to almost all parts of the world. Its

origin in Africa is proved by the fossils which have been found there.

[1][2][3]

The term 'human' in this context means the genus Homo. However, studies of human

evolution usually include other hominids, such as the Australopithecines, from which the

genus Homo had diverged (split) by about 2.3 to 2.4 million years ago in Africa.

[4][5]

The first

Homo sapiens, the ancestors of today's humans, evolved around 200,000 years ago.

[6]

It was known for a long time several centuries that man and the apes were related. At

heart, their anatomy is similar, despite many superficial differences. This was the reason why

Buffon and Linnaeus, in the 18th century, put them together in one family. Charles Darwin's

theory of evolution says that such basic structural similarity comes from the common origin

of the group. The apes and man are close relatives, and are primates: the order of mammals

which includes monkeys, apes, lemurs and tarsiers.

The great apes live in tropical rainforests. It is thought that human evolution started when a

group of apes began to live more in the savannah. Savannah is more open, with trees, shrubs

and grass. This group, the australopithecines started walking on two legs. They began to use

their hands to carry things. Life in the open was quite different, and there was a big advantage

in having better brains. Their brains grew to be much larger, and they began to make simple

tools. All this began at least 5 million years ago. We have fossils of two or three different

groups of walking apes, and one was the ancestor of humans.

The biological name for "human" or "man" is Homo. The modern human species is called

Homo sapiens. "Sapiens" means "thought". Homo sapiens means "the thinking man".

The science that is concerned with finding out how human evolution happened is called

physical anthropology or paleoanthropology. It explains how the human race developed, by

looking at ancient humans fossils, tools, and other signs of human life in the past. The

modern field of paleoanthropology began in the 19th century with the discovery of a skull of

"Neanderthal man" in 1856.

Humans are similar to great apes

By 1859, zoologists had known for a long time that humans were, in their anatomy, similar to

the great apes. There were also differences: humans can speak, for example. But the

similarities were more basic than the differences. Humans also have features with a much

older history, from early in the life of vertebrates.

[7]

The idea that species were the result of evolution had been proposed before Darwin, but his

book gave much evidence, and many were persuaded by it. The book was On the Origin of

Species by means of Natural Selection, published in November 1859. In this book, Darwin

wrote about the idea of evolution in general, rather than the evolution of humans. Light will

be thrown on the origin of man and his history, was all Darwin wrote on the subject.

Nevertheless, the implications of the theory were clear to the readers of the time.

[8]

Different people discussed the evolution of humans. Among them were Thomas Huxley and

Charles Lyell. Huxley convincingly illustrated many of the similarities and differences

between humans and apes in his 1863 book Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature. When

Darwin published his own book on the subject, The Descent of Man, and selection in relation

to sex, the idea of human evolution was already well-known. The theory was controversial.

Even some of Darwin's supporters (such as Alfred Russel Wallace and Charles Lyell) did not

like the idea that human beings have evolved their impressive mental capacities and moral

sensibilities through natural selection.

Since the 18th century, scientists thought the great apes to be closely related to human beings.

In the 19th century, they speculated that the closest living relatives of humans were either

chimpanzees or gorillas. Both live in central Africa in tropical rainforests, mainly of the

Congo. It turns out that the chimpanzee species are closest to us.

[9]

Biologists believed that

humans share a common ancestor with other African great apes and that fossils of these

ancestors would be found in Africa, which they have been. It is now accepted by virtually all

biologists that humans are not only similar to the great apes, but actually are great apes.

The issue was finally settled in modern times by studies on the sequences of proteins and

genes in apes and man. These studies showed that man shares about 98/99% of these

structures with chimpanzees. This is a much closer relationship than with any other type of

animal, and fully supports the ideas put forward in the 19th century by Darwin and Huxley.

"Currently available genetic and archaeological evidence is generally interpreted as

supportive of a recent single origin of modern humans in East Africa. However, this is where

the near consensus on human settlement history ends, and considerable uncertainty clouds

any more detailed aspect of human colonization history".

Distinguishing features

Primates have diversified in habitats such as trees and bushes. They retain many features

which are adaptations to this environment.

[12]

Here are some of those traits:

Shoulder joints which allow high degrees of movement in all directions.

[12]

Five digits on the fore and hind limbs with opposable thumbs and big toes; hands can grasp,

and usually big toes as well.

[12]

Nails on the fingers and toes (in most species).

[13]

Sensitive tactile pads on the ends of the digits.

[12]

Sockets of eyes encircled in bone.

[14]

A trend towards a reduced snout and flattened face, attributed to a reliance on vision at the

expense of smell.

[14]

A complex visual system with binocular (stereoscopic) vision, high visual acuity and color

vision.

[12]

Brain with a well developed cerebellum for good balance.

[14]

Brain large in comparison to body size, especially in simians (old world monkeys and

apes).

[12]

Enlarged cerebral cortex (brain): learning, problem solving.

[12]

Reduced number of teeth compared to primitive mammals;.

[12]

A well-developed cecum: vegetable digestion.

[14]

Two pectoral mammary glands.

[12]

Typically one young per pregnancy.

[12]

A pendulous penis and scrotal testes.

[14]

Long gestation and developmental period.

[12]

and

A trend towards holding the torso upright leading to bipedalism.

[12]

Not all primates exhibit these anatomical traits, nor is every trait unique to primates. In regard

to behavior, primates are frequently highly social, live in groups with 'flexible dominance

hierarchies'.

[15][16]

Other similarities

Closely related animals almost always have closely related parasites. This usually comes

about because parasites evolve with their hosts, and when host populations split, their

parasites split also.

[17]

It is also possible for parasites to get from one species to another. Two

of the most serious parasitic infections of humans in Africa have originated in apes. Each

may have been transferred to humans by a single cross-species event.

There are several species of mosquito, and several species of the malarial parasite

Plasmodium. The most serious type, P. falciparum, which kills many millions of people each

year, originated in gorillas.

[18]

It is now virtually certain that chimpanzees are the source of

HIV-1, the major cause of AIDS.

[19]

This information is got by the sequence analysis of the

nucleic acid of ape and human parasites.

The relevance of this to evolution is that our physiology is so close to the apes that their

parasites were able to transfer to humans with great success. Humans have much less

resistance to these parasites, which are ancient in origin, but comparatively new to our

species.

Immediate ancestors of the genus Homo

It was not until the 1920s that hominid fossils were discovered in Africa. In 1924, Raymond

Dart described Australopithecus africanus.

[20]

The specimen was called the Taung Child, an

australopithecine infant discovered in a cave deposit being mined for concrete at Taung,

South Africa. The remains were a remarkably well-preserved tiny skull and a cast of the

inside of the individual's skull. Although the brain was small (410 cm), its shape was

rounded, unlike that of chimpanzees and gorillas, and more like a modern human brain. Also,

the specimen exhibited short canine teeth, and the position of the foramen magnum was

evidence of bipedal locomotion. All of these traits convinced Dart that the Taung baby was a

bipedal human ancestor, a transitional form between apes and humans.

It took another 20 years before Dart's claims were taken seriously. This was after other

similar skeletons had been found. The most common view of the time was that a large brain

evolved before bipedality, the ability to move on two feet. It was thought that intelligence

similar to that of modern humans was a prerequisite to bipedalism.

The australopithecines are now thought to be immediate ancestors of the genus Homo, the

group to which modern humans belong.

[21]

Both australopithecines and Homo sapiens are

part of the tribe Hominini, but recent data has brought into doubt the position of A. africanus

as a direct ancestor of modern humans; it may well have been a cousin.

[22]

The

australopithecines were originally classified as either gracile or robust. The robust variety of

Australopithecus has since been reclassified as Paranthropus, although it is still regarded as a

subgenus of Australopithecus by some authors.

[23]

In the 1930s, when the robust specimens were first described, the Paranthropus genus was

used. During the 1960s, the robust variety was moved into Australopithecus. The recent trend

has been back to the original classification as a separate genus.

The genus Homo

It was Carolus Linnaeus who chose the name Homo. Today, there is only one species in the

genus: Homo sapiens. There were other species, but they became extinct.

The figure shows where some of them lived and at what time. Some of the other species

might have been ancestors of H. sapiens. Many were likely our "cousins", they developed

away from our ancestral line.

[24]

Anthropologists are still investigating the exact line of descent. A consensus on which should

count as separate species and which as subspecies has not been reached yet. In some cases

this is because there are very few fossils, in other cases it is due to the slight differences used

to classify species in the Homo genus.

The evolution of the genus Homo took place mostly in the Pleistocene. The whole genus is

characterised by its use of stone tools, initially crude, and becoming ever more sophisticated.

So much so that in archaeology and anthropology the Pleistocene is usually referred to as the

Palaeolithic, or the Stone Age.

[25][26]

Homo habilis

Homo habilils was likely the first species of Homo. It developed from the Australopithecus,

about 2.5 million years ago. It lived until about 1.4 million years ago. It had smaller molars

(back teeth) and larger brains than the Australopithecines.

Towards Homo erectus

There are two proposed species that lived from 1.9 to 1.6 million years ago. Their relation has

not been clarified. One of them is called Homo rudolfensis. It is known from a single

incomplete skull from Kenya. Scientists have suggested that this was just another habilis, but

this has not been confirmed.

[27]

The other is currently called Homo georgicus. It is from

Georgia and may be an intermediate form between H. habilis and H. erectus,

[28]

or a sub-

species of H. erectus.

[29]

Homo ergaster and Homo erectus

Homo erectus was first discovered on the island of Java in Indonesia, in 1891. The

discoverer, Eugene Dubois originally called it Pithecanthropus erectus based on its

morphology that he considered to be intermediate between that of humans and apes.

[30]

Homo

erectus lived lived from about 1.8 million to 70,000 years ago. The earlier specimens (from

1.8 to 1.2 million years ago) are sometimes seen as a different species, or a subspecies. called

Homo ergaster, or Homo erectus ergaster'.

In the Early Pleistocene, 1.51 mya, in Africa, Asia, and Europe, presumably, some

populations of Homo habilis evolved larger brains and made more elaborate stone tools; these

differences and others are sufficient for anthropologists to classify them as a new species, H.

erectus. In addition H. erectus was the first human ancestor to walk truly upright.

[31]

This was

made possible by the evolution of locking knees and a different location of the foramen

magnum (the hole in the skull where the spine enters). They may have used fire to cook their

meat.

A famous example of Homo erectus is Peking Man; others were found in Asia (notably in

Indonesia), Africa, and Europe. Many paleoanthropologists are now using the term Homo

ergaster for the non-Asian forms of this group. They reserve H. erectus only for those fossils

found in the Asian region that meet certain requirements (as to skeleton and skull) which

differ slightly from ergaster.

Neanderthal Man

Homo neaderthalensis (usually called Neanderthal man) lived from about 250,000 to about

30,000 years ago. Also, less usual, as Homo sapiens neanderthalensis: there is still some

discussion if it was a separate species Homo neanderthalensis, or a subspecies of H.

sapiens.

[32]

While the debate remains unsettled, evidence from mitochondrial DNA and Y-

chromosomal DNA sequencing indicates that little or no gene flow occurred between H.

neanderthalensis and H. sapiens, and, therefore, the two were separate species.

[33]

In 1997,

Dr. Mark Stoneking, then an associate professor of anthropology at Pennsylvania State

University, stated:

"These results [based on mitochondrial DNA extracted from Neanderthal bone] indicate that

Neanderthals did not contribute mitochondrial DNA to modern humans Neanderthals are

not our ancestors".

More investigation of a second source of Neanderthal DNA supported these findings.

[34]

A third species

A genetic analysis of a piece of finger bone found in Siberia has produced a surprise result. It

dates to about 40,000 years ago, at a time when Neanderthals and modern man were living in

the area. German researchers found its mitochondrial DNA did not match that of our species

or Neanderthals. The possibility is that the bone may belong to a previously unknown

species. The degree of difference in the DNA suggests this species split off from our family

tree about a million years ago, well before the split between our species and Neanderthals.

[35]

Homo floresiensis

Homo floresiensis, which lived about 100,00012,000 years ago has been nicknamed hobbit

for its small size. Its size may be a result of island dwarfism, the tendency for large mammals

to evolve smaller forms on islands.

[36]

H. floresiensis is intriguing both for its size and its age.

It is a concrete example of a recent species of the genus Homo that shows derived traits not

shared with modern humans. In other words, H. floresiensis share a common ancestor with

modern humans, but split from the modern human lineage and followed a different

evolutionary path. The main find was a skeleton believed to be a woman of about 30 years of

age. Found in 2003 it has been dated to approximately 18,000 years old. The living woman

was estimated to be one meter in height, with a brain volume of just 380 cm

3

This is small for

a chimpanzee and less than a third of the H. sapiens average of 1400 cm

3

.

There is an ongoing debate over whether H. floresiensis is indeed a separate species.

[37]

Some

scientists believe that H. floresiensis was a modern H. sapiens suffering from pathological

dwarfism.

[38]

Modern humans who live on Flores, the island where the skeleton was found,

are pygmies. This fact is consistent with either theory. One line of attack on H. floresiensis is

that it was found with tools only associated with H. sapiens.

[38]

Human arrival on Flores

Stone artefacts have now been found on Flores which can be dated to a million years ago.

These artefacts are proxies; which means there were no skeletons of humans, but only a

species of Homo could have made the artefacts. The artefacts are flakes and other

implements, 48 in all, some of which show signs of being worked to produce a cutting edge.

This means that humans were present on Flores by that date, but it does not tell us which

species that was.

[39]

Homo sapiens

Homo sapiens has lived from about 250,000 years ago to the present. Between 400,000 years

ago and the second warm period in the Middle Pleistocene, around 250,000 years ago, its

skull grew and more sophisticated technologies based on stone tools developed. One

possibility is that a transition between H. erectus to H. sapiens occurred. The evidence of

Java Man suggests there was an initial migration of H. erectus out of Africa. Then, much

later, a further development of H. sapiens from H. erectus in Africa. Then a subsequent

migration within and out of Africa eventually replaced the earlier H. erectus.

Out of Africa

Studies of the human genome, especially the Y-chromosome DNA and mitochondrial DNA,

have supported a recent African origin.

[40]

Evidence from autosomal DNA also supports the

recent African origin. The details of this great saga are not fully established yet, but by about

90,000 years ago they had moved into Eurasia and the Middle East. This was the area where

Neanderthals, Homo neanderthalensis, had been living for a long time (at least 350,000

years).

By about 42 to 44,000 years ago Homo sapiens had reached western Europe, including

Britain.

[41]

In Europe and western Asia, Homo sapiens replaced the Neanderthals by about

35,000 years ago. The details of how this happened are not known.

At roughly the same time Homo sapiens arrived in Australia. Their arrival in the Americas

was much later, about 15,000 years ago.

[42]

All these earlier groups of modern man were

hunter-gatherers.

Current research has established that human beings are genetically rather homogenous

(similar). The DNA of individuals is more alike than usual for most species. This may have

resulted from their relatively recent evolution or from the Toba catastrophe. Distinctive

genetic have arisen as a result of small groups of people moving into new environmental

circumstances. These adapted traits are a very small component of the Homo sapiens genome

and include such outward 'racial' characteristics as skin color and nose shape, and internal

characteristics such as the ability to breathe more efficiently at high altitudes.

H. sapiens idaltu, from Ethiopia, about 160,000 years ago, is a proposed subspecies. It is the

oldest known anatomically modern human.

Species list

This list is in chronological order by genus.

Sahelanthropus

o Sahelanthropus tchadensis

Orrorin

o Orrorin tugenensis

Ardipithecus

o Ardipithecus kadabba

o Ardipithecus ramidus

Australopithecus

o Australopithecus anamensis

o Australopithecus afarensis

o Australopithecus bahrelghazali

o Australopithecus africanus

o Australopithecus garhi

Paranthropus

o Paranthropus aethiopicus

o Paranthropus boisei

o Paranthropus robustus

Kenyanthropus

o Kenyanthropus platyops

Homo

o Homo habilis

o Homo rudolfensis

o Homo ergaster

o Homo georgicus

o Homo erectus

o Homo cepranensis

o Homo antecessor

o Homo heidelbergensis

o Homo rhodesiensis

o Homo neanderthalensis

o Homo sapiens idaltu

o Homo sapiens (Cro-magnon)

o Homo sapiens sapiens

o Homo floresiensis

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- ContentDocument1 pageContentJyotimoy Ggoi BHaiPas encore d'évaluation

- KazirangaDocument3 pagesKazirangaJyotimoy Ggoi BHaiPas encore d'évaluation

- Project Report ON HTML: Submitted byDocument8 pagesProject Report ON HTML: Submitted byJyotimoy Ggoi BHaiPas encore d'évaluation

- Indian Sports ManDocument3 pagesIndian Sports ManJyotimoy Ggoi BHaiPas encore d'évaluation

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- History of Humanity Hominid Rise CHDocument15 pagesHistory of Humanity Hominid Rise CHDurba GhoshPas encore d'évaluation

- Athreya and Ackermann 2018 Colonialism Narratives Human Origins Asia AfricaDocument33 pagesAthreya and Ackermann 2018 Colonialism Narratives Human Origins Asia Africamoni_ayalauahPas encore d'évaluation

- Human Evolution CL 2019Document56 pagesHuman Evolution CL 2019Masentle MonicaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Ascent of Man - BronowskiDocument96 pagesThe Ascent of Man - Bronowskialecloai75% (4)

- Human Evolution - Ape To ManDocument6 pagesHuman Evolution - Ape To ManAngela Ann GraciaPas encore d'évaluation

- Grade 12 Life Sciences Human Evolution WorkbookDocument21 pagesGrade 12 Life Sciences Human Evolution WorkbookMathabi AnndwelePas encore d'évaluation

- Ardipithecus KadabbaDocument29 pagesArdipithecus KadabbaDonnalin Peach VerdidaPas encore d'évaluation

- Upright The Evolutionary Key To Becoming Human-F0618302476Document225 pagesUpright The Evolutionary Key To Becoming Human-F0618302476Rupesh Sushir100% (2)

- The Family Tree of ManDocument5 pagesThe Family Tree of ManElisha Gine AndalesPas encore d'évaluation

- The 23rdian - The 23 Mystery (2022)Document84 pagesThe 23rdian - The 23 Mystery (2022)MR50% (2)

- Lone Survivors How We Came To Be The Only Humans On EarthDocument12 pagesLone Survivors How We Came To Be The Only Humans On EarthMacmillan Publishers75% (4)

- Australopithecus Africanus HandoutDocument3 pagesAustralopithecus Africanus HandoutLarissa McKnightPas encore d'évaluation

- PDU PB SearchableDocument162 pagesPDU PB SearchableAsanda DengaPas encore d'évaluation

- Human EvolutionDocument9 pagesHuman EvolutionVinod BhaskarPas encore d'évaluation

- History For 9th GradeDocument75 pagesHistory For 9th GradeMichael RodionPas encore d'évaluation

- Ape To Man TranscriptDocument26 pagesApe To Man Transcriptteume reader accPas encore d'évaluation

- Birth of AustralopithecusDocument9 pagesBirth of AustralopithecusDemetris TsimperisPas encore d'évaluation

- Forbidden Archeologys ImpactDocument126 pagesForbidden Archeologys ImpactMichael Lasley100% (8)

- The Briefing Anthology - Jonas Kyratzes and Allen Stroud PDFDocument475 pagesThe Briefing Anthology - Jonas Kyratzes and Allen Stroud PDFAnderson DePaulaPas encore d'évaluation

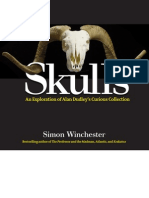

- Skulls: An Exploration of Alan Dudley's Curious Collection - Review SamplerDocument11 pagesSkulls: An Exploration of Alan Dudley's Curious Collection - Review SamplerBlack Dog & Leventhal100% (3)