Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

From The Book PINK and BLUE WORLD Gender Stereotypes and Their Consequences

Transféré par

Maura Batarilović0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

140 vues13 pagesThis document summarizes key ideas from Simone de Beauvoir's book The Second Sex regarding gender and sex. It discusses how biology alone does not determine whether someone is a woman or man, but rather society also shapes their gender roles and expectations. While sex may be evident at birth, naming a baby also implies their future gender socialization. The document argues that perceived differences between women and men are not natural or innate, but are socially and culturally constructed over time to legitimize inequality between the sexes.

Description originale:

-

Titre original

From the Book PINK and BLUE WORLD Gender Stereotypes and Their Consequences

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentThis document summarizes key ideas from Simone de Beauvoir's book The Second Sex regarding gender and sex. It discusses how biology alone does not determine whether someone is a woman or man, but rather society also shapes their gender roles and expectations. While sex may be evident at birth, naming a baby also implies their future gender socialization. The document argues that perceived differences between women and men are not natural or innate, but are socially and culturally constructed over time to legitimize inequality between the sexes.

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

140 vues13 pagesFrom The Book PINK and BLUE WORLD Gender Stereotypes and Their Consequences

Transféré par

Maura BatarilovićThis document summarizes key ideas from Simone de Beauvoir's book The Second Sex regarding gender and sex. It discusses how biology alone does not determine whether someone is a woman or man, but rather society also shapes their gender roles and expectations. While sex may be evident at birth, naming a baby also implies their future gender socialization. The document argues that perceived differences between women and men are not natural or innate, but are socially and culturally constructed over time to legitimize inequality between the sexes.

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 13

from the book PINK AND BLUE WORLD Gender Stereotypes and Their Consequences

Cvikov, Jana Jurov, Jana, eds.

Aspekt and Citizen and Democracy 2003

1

st

edition

292 pages

English translation by Eva Rieansk

Jana Cvikov

One Is Not Born a Woman or a Man

Sex and Gender

One is not born a woman, but becomes one

Simone de Beauvoir

One is not born a woman? Or a man? Is that really so? The first thing we learn after a baby is

born is her sex. Surely, the words its a boy or its a girl are statements naming some

biological reality that is usually beyond any doubt. But that is not the end of the story. The

verdict its a boy or its a girl does not concern only biological characteristics. It also

decides about the future direction of the social development of the baby as a girl and woman

or as a boy and man will head. On the one hand, the statement names the biological sex, on

the other hand it implies the gender of a person as a set of social roles and cultural norms and

expectations related to femininity and masculinity.

Gender Difference

So, is it a boy or a girl? Hansel or Gretel? Dominic or Dominique? Kim or Kim? Beautiful

Day or Sitting Bull? Stupid Hans or Cinderella?

Babies get their names so that they will not get lost in the world; so that they can become part

of human society. But there is more to a name: in most societies the name indicates the sex of

its bearer and becomes important in gender specific socialization of a child. The child is not

given just any kind of a name but a name that clearly denotes its sex. Rules about reading

names as male and female differ in different cultures. The name is a complicated cultural

construct and as such it is close to gender. In our society, naming rules are also regulated by

the law. Laws and regulations require the congruence of sex and gender and they take for

granted that sex is unambiguous (which, by the way, in a small percentage of babies is not a

clear biological given, and their parents have to choose: either a boy or a girl).

It seems that in order to run smoothly, our society needs to clearly and unequivocally

distinguish between the sexes and maintain the social distinctions between femininity and

masculinity via deliberate (e.g. the law) and unintentional (e.g. fairy tales) mechanisms. This

distinction is substantiated by the role of women and men in reproductive processes, but it

does not involve just biological characteristics: different biological functions or capacities of

the female and male body are the starting point for other imperative differences regarding the

way of life, characteristics, appearance and behaviour. At present, the definition of the role of

women and men, and the division of labour between genders is closely related to the

understanding of pregnancy and childbirth as the only womans predestination. In spite of

changed social circumstances of reproduction, gender differentiation, and considerable

polarization of interests, activities and personalities of women and men prevail in most areas

of our life; but that does not mean that these divisions are natural. The relationship between

women and men, based chiefly on concrete and variable norms of the gender role, differs

in different societies and time periods. It is not natural, but historically, socially and broadly

speaking culturally determined.

Legitimisation of Inequality

We know the rhetoric of inequality between women and men in its past socialist and

present-day variation. We have experiences with changes in gender relations in both the

public and private sphere but also with cemented prejudice about changeless femininity and

masculinity. Where is this contradiction coming from and what purpose does it serve?

We can use arguments about tradition, nature or natural order of the world and hence confirm

the domination of the male way of seeing,

1

taking for granted the existing power relations,

and believe that they are immutable. Or we can critically look at the current constructs of

masculinity and femininity, on the role of gender specific socialization of men and women in

maintain and confirming of inequality in our society and thus open up the space for changes

that can be effectively started in school.

The conviction that the dissimilarity of the female and male role naturally follows from their

biological difference is one of the most stable pillars of our culture. Its power is great. It

ignores everything that subverts it historical, social or psychological facts and it even

contravene our own experience. Through the use of stereotypes, people around us daily

convince us about the truthfulness of the statement about the strong and weak sex, which

has about as much validity as the statement that women wear skirts and wear men trousers. As

a consequence of the belief in natural gender difference we often forget what women and men

as human beings have in common, what unites them. And although the biological sex is not

completely separable from cultural gender, and gender stereotypes hinge on biological sex,

the variability of women and men within their own sex/gender is much more pronounced than

the difference between women and men as groups.

Differentiation of sexes and genders is significantly implicated in the arrangement of

relationships between women and men in society, chiefly because it legitimises this

arrangement as natural. The argument about unquestionable validity of natural laws justifies

unequal division of labour between women and men, in which women do most of unpaid or

worse paid work. It also justifies unequal distribution of power between women and men

the power to decide about themselves and the world that surrounds them.

The belief that there is some generally valid and correct masculinity and femininity puts

women and men into a narrow straightjacket of prescribed roles that do not correspond with

real needs of partnership and cooperation between people in society a do not respect the

individuality of women and men as unique human beings. Therefore, in our society the words

a boy or a girl is often a verdict putting the baby on a track leading to either the pink of

the blue world.

Two Waves of Feminism

2

Already in the 18

th

and 19

th

century, critically thinking women and men questioned the

ideology of immutability of the predestined female and male role. Mary Wollstonecraft,

Olympe de Gouges, Stuart Mill, the suffragists, Rosa Mayreder, Elena Marthy-oltsov and

others mostly critiqued the female nature that should prevent women from getting education

and the right to vote. The first wave of feminism in the 19

th

century and the beginning of the

20

th

century focused mostly on womens suffrage.

Nowadays, we take womens right to vote for granted and we do not give much thought to

whether it is unwomanly and whether its exercise requiring making independent

decisions, seriously violates womens health or morals (even the contemporary definition of

the right womanhood presumes that a woman doesnt know what she wants, asks other

for directions, lets herself being led, is dependent). Or more precisely we dont give

too much thought to the active right to vote, but we often and without hesitation comment on

the prescriptive femininity of a female politician using stereotypical female attributes.

The first country to grant women the right vote was New Zealand in 1883. In Czechoslovakia,

women gained the right to vote in 1919, in France as late as 1944. The illusion that universal

suffrage would ensure gender equality swiftly dissipated. The French writer and philosopher

Simone de Beauvoir in her iconoclastic book The Second Sex (first published in 1949)

examines deeper roots of womens subordination from the perspective of concrete family

relations and socialization of girls and boys, as well as from the perspective of transmission of

tradition and knowledge in society as a whole. The formation of a womanly passive woman

(dont be a tomboy, dont soil you dress, be a nice/good girl) and a manly active man

(boys dont cry, dont be a sissy, fight with the dragon) is constantly happening on

several levels: in fairytales a woman will learn that in order to be happy she must be loved,

and in order to be loved she must wait for her love (de Beauvoir, published in Slovak:

Aspekt 1/2000). Fairytales, stories and folk songs are filled with Sleeping Beauties,

Cinderellas, stepdaughters, and women who give, wait and suffer. In songs and fairytales

the young man adventurously sets out to look for a wife. He fights with dragons, wrestles with

giants; she is locked up in a tower, palace, garden, tied to a rock, captured, sleeping she is

waiting. (Ibid.). De Beauvoirs disillusive analysis of prevailing cultural patterns maintaining

a hierarchical relationship between women and men and putting women in the position the

second sex caused much furore and countless discussions. The book The Second Sex has

become cult reading for the second wave of feminism. The author in the book summarizes

cultural underpinnings of the female role: "One is not born, but becomes a woman. No

biological, psychological, or economic fate determines the figure that the human female

presents in society: it is civilization as a whole that produces this creature, intermediate

between, male and eunuch, which is described as feminine." (de Beauvoir, in Slovak in :

Aspekt 1/2000.)

The second wave of feminism that started in the USA in the 1960s and in Western Europe in

the 1970s

3

initially focused upon womens access to paid jobs, reproductive and sexual rights

and health. Later the spectrum of issues broadened: violence against women and children

(esp. the issue of sexualised violence), inadequate representation of women at all decision

making levels, the domination of the male perspective and indivisibility of women in

science, research and education, and others.

The feminist movement and thinking was diverse already at its beginning and with the

passage of time it has grown even more pluralistic therefore it is better to speak about

feminisms (such as ecofeminism, African-American feminism, liberal feminism, socialist

feminism, feminism of gender equality) rather than a singular feminism. These different

feminisms mutually overlap, interlink, and complement each other, but they also fight, negate

and contradict one another. Their common thread, however, is the conviction that women are

human beings and therefore they have the duties but also responsibilities and rights of a

human being.

Sex and Gender

In western countries thanks to feminist thinking the distinction between biological sex and

cultural gender has become important part of reflection in science, education and politics esp.

since the 1980s.

Feminist and later gender theories have unmasked the gender blindness of the way of seeing

that used to be regarded as gender neural. It became and more difficult to present the

domination of the male perspective as seemingly gender neutral.

From the gender perspective it has become apparent that it is not only the female gender role

but also the male gender role that is affected by ideas or even the dictate of a concrete society

in a concrete time and space. Gender-aware observations and analyses of social structures

have shown that problematic it is not only obviously disadvantaged femininity, the critique

of which already has a long tradition, but also masculinity distancing men from

relationships and their responsibility for them. No matter how diverse the gender role when

performed by individual women and men may be it is not primarily an individual matter. Its

formation is influenced by stereotypical ideas about femininity and masculinity surrounding

us and creating the setting for its performance. The stereotypes condition gender relations that

are constructed on the basis of conventional perceptions, cultural patterns and ideologies

piling up around the concept of true femininity and masculinity. The symbolic order based

on complete difference and mutual exclusivity of the two sexes as we can see it in the

expression the opposite sex implying that the man should be the opposite of the woman and

vice versa, is not limited to the mere statement about otherness of the sexes. The opposition of

sexes is linked to evaluation of this otherness, to creation of hierarchies, to assigning of

functions, and to formation of stereotypical ideas.

The Rules of Femininity and Masculinity

No matter what her individual personality and life circumstances may be, each concrete girl or

woman is confronted with the basic rule of femininity: in no case should a woman want to be

like a man. This rule creates a set of expectations that can be summed up by statements such

as she is mindful that a man doesnt feel week or inferior, she finds her self-fulfilment in

caring for others, she is sensitive, gentle, compliant or she tolerates much and forgives

a lot. The main rule of masculinity - since a man is not a woman he never does what

a woman does confronts a boy, irrespective of his individual personality and life

circumstances, with expectations that cold be summed up by statements such as he wants to

be stronger, smarter and wants to earn more money, he finds his self-fulfilment in

professional success, he is tough, never showing his feelings or he tolerates nothing and

forgives nothing.

When comparing these expectations still marked by broadly accepted stereotypical ideas

about women and men, one must ask whether it is possible for these women and men to live

in a partnership based on fair division of rights and responsibilities in both the private and

public life. They will not get away easily with breaking the basic rules they will suffer

ridicule (comedians who ridicule women or unmanly men are commonly rewarded by

appreciative bursts of laughter from their audience) and scorn (masculine women or

effeminate men are often targets of cruel despise).

This general agreement about what is funny and despicable attests to general

comprehensibility of gender stereotypes in our culture, and indicates what they are good

for. They simulate simple orientation in the world: from the perspective of short-term

effectiveness it is expedient to use what appears to us as culturally obvious. But the question

is: what price do we pay for that.

A stereotype does not have a subject it is not created and reproduced by someone. It

emerges and is reproduced in the web of expectations and those to whom stereotypes pertain

cannot influence them. Our own stereotypical expectations depend on stereotypical

expectations of others and this creates a vicious circle. For instance, from the stereotype that

women are mothers follows the stereotype that women want to take over exclusive

responsibility of childcare, and from that follows the stereotype that women seek out part-

time jobs, which in turn discriminates against all women on the labour market. Facing this

dead-end situation, people that are discriminated against usually conform to the stereotype

that lies at the root of the discriminatory situation. The impossibility to escape, forces them to

resign (McKinnon quoted in Holzleithner 2003).

The ubiquitous implicit gender hierarchy daily places us inside the limits of the stereotypical

gender role. As it seems, for the sake of social stability it is simpler to maintain the social

order based of an unjust and distorting stereotype rather than to constantly negotiate the social

order based on open communication and mutual respect.

However, the stereotypical understanding of the female and male role that would confirm and

maintain gender inequality is shaking. Its presence in the real life is not as frequent and firm

as the ideological constructs in advertising, the media, politics, fairytales, literature or text

books are trying to convince us. On the other hand, stereotypical constructs influencing social

values are arduously resisting verbal political proclamations about equality between women

and men, provisions on gender equality in the Constitution of the Slovak republic, laws

prohibiting discrimination on the basis of sex and gender in employment, as well as the reality

of changing roles of concrete women and concrete men.

The Pink and Blue Imperative.

The fixed idea about inborn femininity and masculinity glosses over the fact that children

enter a micro and macro-cosmos formed by the cultural pattern of gender duality and that in

each moment of their lives the socialization of a girl or boy takes place in this divided and

hierarchically organized world. Children enter a pre-structured world of expectations, hopes,

limits and colours, in which gender as a social category plays a very important role. In our

cultural setting, the girl is surrounded by the pink imperative and the boy the blue imperative.

The attribution of gender roles happens by means of communication, evaluation, clothing,

selection of toys and games. The decision between a doll and a car does not follow from the

biological sex of the baby but from the social evaluation of the toy as either appropriate or

inapposite for a girl or a boy. If we, as parents, decide to disrupt this strict division of toys and

give a boy, for instance, a doll to play with we are aware of the fact that our decision goes

against conventions and that it is more than likely that reactions to a boy playing with a doll

will be different from the reactions to a girl. The children are also likely to receive different

instructions on how to handle the doll. Usually no one rushes in to remind a boy playing with

a doll about how to caress it, and he will not be immediately called a father. People around

him will not get excited over his inborn fatherly instinct. On the contrary, when a girl is

playing with a doll the instructions and appreciation of the adults usually emphasize her

presumed future motherhood.

The play of both children is seemingly the same - they are playing with the same toy, but the

cultural framework of their play is gender specific. As the author of one the basic studies

about gender stereotypical socialization approaches Elena Gianini Belotti points out: A child

has an inborn capacity to play, but the rules and objects are undoubtedly the product of

culture. (Belotti, in: Aspekt1/2000.)

The repertoire of toys is just seemingly broad. Children select their toys and games

independently, but they also react to what we offer them. And this offer is already a selection

from the existing choice.

An important factor creating the existing offer and guiding parents choices is advertising.

Advertising works with stereotypes with their confirmation and subversion. In Slovakia, in

toy advertising still prevails uncritical exploitation of gender stereotypes, which leads to their

further reproduction even reinforcement. The colour design of ads copies the gender

stereotypical rules of the pink and blue world.

Let us demonstrate how this functions on concrete advertising leaflets:

For babies of up to 3 years many toys are still gender neutral. This may not be true for all

toys, but it is true for animals and building blocks. Under the slogan The best for the

youngest, the leaflet offers toys appropriate for both girls and boys it does not

discriminate on the basis of their gender. The prevailing yellow colour with no strict gender

coding is used to signal openness.

The best for the youngest

The pink and blue worlds of the other pages of the leaflet speak about different demarcation

of the space for girls and boys girls belong to the household (the private sphere), while boys

belong to the world (the public sphere); the girls should be practical while the boys should be

creative, and the like.

While the girls depicted on the pink page as small mothers (Lets pretend we are moms and

housewives) are taking care of dolls, carrying out household chores and taking care of

themselves to be pretty, the boys on the blue page are receiving their invitation to the world of

creativity and knowledge.

Lets pretend we are moms and housewives

For young scientists and constructors

While the girls on the pink page get the message that they are little dressy girls and the best

jobs for them are a seamstress, hair dresser or beautician, the boys on the opposite blue page

are setting out to conquer the world.

For small adventurers

For small seamstresses and dressy girls

Another advertising leaflet seemingly introduces us to the world of a family, as if the offer

from the private sphere to be like my mom or to be like my dad was equally addressing

both girls and boys. At a closer look, however, the situation appears to be very different: the

girl on the pink page under the slogan I want to be like my mom is doing house chores and

taking care of dolls. The boy, who wants to be like his dad identifies himself with action

figures of superheroes.

and I want to be like my father

The identification offer for girls is clear: a girl = a future mother. Directly linked to

motherhood is the female obligation to take care of their appearance and household. Given the

high female unemployment rate in our country it is remarkable that advertising based on such

reduction of the female role actually works. Pink departments of toy stores make profit;

therefore our society seems to prefer this division of labour - irrespective of the equality of

opportunities.

The identification offer for boys is much more diverse: a boy = a future professional (or

conqueror), but not a future father. The action figures of superheroes whose image is evoked

as a paternal model can hardly be considered to be preparation for fatherhood.

Nobody prevents girls and boys from becoming successful professionals or good fathers,

respectively, but nobody supports them to become so either. On the contrary, all signals are

telling them: you do not live in the same world.

At the beginning, the inquiry into mechanisms of gender stereotypes was based on the idea of

female gender stereotypical socialization as limiting and constraining (Scheu in: Aspekt

1/2000), which was understandable given the tangible discrimination against women that had

been the first impulse for critical approach to traditional roles. This approach considered the

male role - in contrast to the female role, to be the source of social privilege but also of higher

personal satisfaction. Later it became apparent that also men are constrained by gender

stereotypes (see e.g. Bernardov Schlaferov 1997).

Striking about the given advertisements examples is the fact that girls can at least partly find

some reality of the life of their mothers and other women in the presented patterns. That is

much harder for boys: the father is absent and not all men they know are scientists or

conquerors of new planets.

Games and toys do not exist in the vacuum of arbitrariness they are socially embedded and

serve to put girls and boys on the track of their conventional social role. When children react

in accordance with conventional expectations we consider that a mollifying symptom of

normality (Belotti in: Aspekt 1/2000). The selection of toys attests to the fact that children

very early know what behaviour is rewarded and what behaviour is regarded as gender

appropriate. The fact that differentiation of toys into intended for boy and for girls grows with

childrens age points to very strong cultural influences (Oakley 2000).

Gender Relations in Textbooks

If children were getting all information on gender relations in the grown-up world only from

their textbooks they wouldnt have any idea that they are living in a country in which gender

equality is guaranteed by the constitution, comments bitterly on her analysis of elementary

education textbooks the Polish author Anna Golnikowa.

In school besides official explicit curriculum we present to children also hidden curriculum.

This curriculum often reinforces existing gender stereotypes esp. gender division of labour.

The choice of life paths of boys and girls differs considerably. Rigid gender stereotypes are

not limited just to advertising as a symbol of superficial consumerism but they also dominate

in textbooks that are a symbol of generational transmission of knowledge.

When going through the pages of ABC books, primers and readers for first classes of

elementary schools we often come across stereotypical division of labour in the family:

The father is reading a newspaper

The mother is pushing a stroller with a baby.

Boba and Biba have new dolls.

Biba is pushing a stroller with her doll.

But the doll is not sleeping. She is crying: Ma-ma!

Boba is carrying her doll.

My doll is barefoot.

I will give her blue slippers.

Biba and Boba are little moms.

They are playing with their dolls.

Just like advertising, also textbooks prepare girls for their maternal role. Boys are reminded of

their paternal role only in passing, in addition to other, more important things such as a

motorcycle or football. In textbooks, boys and men represent people as such, they are

universal representatives of the humankind; girls and women are often just invisibly included.

Textbooks bring the idea about incompatibility of the image of the real man (The proper man

is interested in football) and the father who shares a common world with his children. The

image of the mother is reduced to the image of a servant as if the real woman was just a

performer of household chores. These images in textbooks have survived socialist

emancipation of women and they are still alive irrespective of the fact that their real life

validity for the whole population of Slovakia is at best dubious. This approach encodes female

fear of the public space and male incompetence in the private one, which has implications not

only for division labour in childcare and household care but also in the public life.

Examples of texts in readers:

Mother is washing laundry in a washing machine () She washes it and hangs it. The

washing machine is moms good helper. She is putting the laundry in the washing machine.

Mom was playing with my new shoe and Dads pen. I dont know why - she is a gown-up.

Even dad didnt know. He asked mom: What are you doing?

Im writing down our address so that people will know where to bring back your daughter is

she got lost at the football match, replied Mom.

But what do about it? Textbooks are very important teaching aids should we throw all of

them away?

We should not but we can speak with children about the images of women and men in

textbook and compare them with the diversity of reality. We can try to notice stereotypes in

our own approach to children and to curriculum and strive for a gender sensitive approach.

We can use subversive texts, or non-traditional interpretations of fairytales. Together with

children, we can learn to critically perceive the eternal and only truths.

What Society Does Not Know

The school and people in it are part of the whole society; therefore the school will not teach

what society does not know. The process of transformation of our society has brought about

diversification. Sometimes it seems that society, or its parts, do already know, but the school

has not learned yet. In the 1990s non-governmental womens organizations were springing up

and they were gradually opening up themes related to womens human rights and especially

to the unequal status of women and men. Feminist and gender studies programmes started to

develop and book were published.

4

Mainly in relation to the EU accession process, emerged

also the first official instruments to foster equal opportunities of women and men in society

(Department of Equal Opportunities at the Ministry of Labour, Social Affairs and Family and

the Conception of Equal Opportunities for Women and Men). The Conception approved by

the Government of the Slovak republic contains concrete provisions related to education such

as modification of the curriculum to include gender equality and non-discrimination on the

basis of gender and sex and elimination of gender stereotypes. These provisions are in line

with the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women

(CEDAW) that is binding also for the Slovak Republic. From the educational perspective

especially relevant is namely article 5 in which states committed themselves to taking all

appropriate measures to modify the social and cultural patterns of conduct of men and

women, with a view to achieving the elimination of prejudices and customary and all other

practices which are based on the idea of the inferiority or the superiority of either of the sexes

or on stereotyped roles for men and women; and also point (c) of Article 10 that commits the

states to the elimination of any stereotyped concept of the roles of men and women at all

levels and in all forms of education, in particular, by the revision of textbooks and school

programmes and the adaptation of teaching methods;

This means that the school will learn several basic things:

- Biological sex is determined by nature and its principles before the baby is born; at the

latest in the moment of childbirth the babys gender starts to shape;

- Certain differences based on biological predispositions do exist but they do not justify the

ideas about natural existence of the female and male role as given and the only correct

ones, and do not justify unequal social status of women and men.

- The process of gender specific socialization of girls and boys has many layers and is

taking place constantly; it is resistant to attempts at its conscious control. However,

teachers when creating the offer of co-ordinates of orientation and identification for their

pupils, have the power to decide whether the school will uncritically participate in the

reinforcement and reproduction of gender stereotypes or whether it will question them,

uncover their meanings and open up new spaces for both girls and boys to shape their own

forms of femininity and masculinity.

And that also means that through reflection on their own gender role and stereotypical images

of women and men, all school goers will get a change of more self-conscious orientation in

the world.

References:

Feminist cultural magazine Aspekt, especially the issue One is Not Born a Woman 1/2000.

Beauvoir, Simone de: Druh pohlavie. In: Aspekt 1/2000. (The Second Sex)

Belotti, Elena Gianini: Hra, hraky a detsk literatra In: Aspekt 1/2000. (Games, Toys and

Childrens Literature)

Bernardov, Cheryl Schlaferov, Edit: Matky dlaj mue. Jak dospvaj synov. Pragma,

Praha 1997. (Sons are Made by Mothers, How Sons Grow Up)

Golnikowa, Anna: Utrwalanie tradycyjnych rl pciowych przez szkole. In: Penym Gosem

3/1995. eFKa, Krakov.

Hevier, Daniel: Straidelnk. Kniha pre (ne)bojcne deti. Aspekt, Bratislava 1998.

Holzleithner, Elisabeth: Recht Macht Geschlecht. Legal Gender Studies. Eine Einfhrung.

WUV Universittsverlag, Viede 2002.

Jurov, Jana: Iba baba. Aspekt, Bratislava 1999.

Oakleyov, Ann: Pohlav, gender a spolenost. Portl, Praha 2000. (Sex, Gender and Society)

Scheu, Ursula: Nerodme sa ako dievat, urobia ns nimi. In: Aspekt 1/2000. (We are Not

Born Girls, They Make Us Be Them)

Endnotes:

1

The male way of seeing, in this respect, does not denote concrete individual perception of a male human

being or a concrete man, but understanding and interpretation of things from the perspective of the dominant

social status of men. This way of seeing regards the man as the universal representative of the humankind.

2

We use the plural form of the word feminism to emphasize the fact that it is a very diverse social and ideational

movement.

3

In our country we can speak about the second wave of feminism only after the year 1989. Since its beginning it

has had a different course then in the USA and the countries of western Europe but it has drawn inspiration from

their experience and theoretical reflection. At first, it was mainly focused on educational and publication

activities (the feminist cultural magazine Aspekt, the Centre for Gender Studies at Faculty of Philosophy,

Comenius University in Bratislava) and later also on human rights activities (Piata ena/The Fifth Women

violence against women, Monos voby/Pro Choice womens reproductive rights).

4

The first steps were the Lecture Series in Feminist Philosophy at the Faculty of Philosophy Comenius

University in Bratislava and the feminist cultural magazine Aspekt in Bratislava. You can find more information

on publications at www.aspekt.sk.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Invincible Family: Why the Global Campaign to Crush Motherhood and Fatherhood Can't WinD'EverandThe Invincible Family: Why the Global Campaign to Crush Motherhood and Fatherhood Can't WinÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- Benshoff - GenderDocument4 pagesBenshoff - GenderCandela Di YorioPas encore d'évaluation

- Equality for Women = Prosperity for All: The Disastrous Global Crisis of Gender InequalityD'EverandEquality for Women = Prosperity for All: The Disastrous Global Crisis of Gender InequalityÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1)

- Module 1 Topic 1 Introduction To Gender WorkbookDocument8 pagesModule 1 Topic 1 Introduction To Gender Workbookapi-218218774Pas encore d'évaluation

- Feminism Is Not MonolithicDocument6 pagesFeminism Is Not MonolithicMavis RodriguesPas encore d'évaluation

- Gender RolesDocument2 pagesGender RolesbabyPas encore d'évaluation

- Human Development: Nature or Nuture?Document9 pagesHuman Development: Nature or Nuture?Gundel Mai CalaloPas encore d'évaluation

- Women, Power and Politics AssignmentDocument5 pagesWomen, Power and Politics AssignmentsamPas encore d'évaluation

- Kamla Bhasin GenderDocument50 pagesKamla Bhasin GenderBhuvana_b100% (13)

- Gender Convergence and Role EquityDocument24 pagesGender Convergence and Role EquityJhiean IruguinPas encore d'évaluation

- The Social Construction of Gender by Judith LorberDocument7 pagesThe Social Construction of Gender by Judith LorberJamika Thomas100% (1)

- Feminism NotesDocument89 pagesFeminism NotesTanya Chopra100% (1)

- Gender Roles Thesis TopicsDocument4 pagesGender Roles Thesis Topicsdonnagallegosalbuquerque100% (2)

- Gender and Customary Law in Nigeria: The Yoruba Perspective - Chapter OneDocument15 pagesGender and Customary Law in Nigeria: The Yoruba Perspective - Chapter OneFunmilayo Omowunmi Falade100% (1)

- Final Man and WomanDocument3 pagesFinal Man and WomanNatalia JianPas encore d'évaluation

- Gender Is Socillay ConstreuctedDocument6 pagesGender Is Socillay ConstreuctedYasir HamidPas encore d'évaluation

- Notes On Gender and DevelopmentDocument4 pagesNotes On Gender and DevelopmentDei Gonzaga100% (3)

- Divorced Women RightsDocument41 pagesDivorced Women RightsAnindita HajraPas encore d'évaluation

- Ideology, Myth & MagicDocument22 pagesIdeology, Myth & MagicEdvard TamPas encore d'évaluation

- SEX-GENDER DEBATE Ge Pol SciDocument2 pagesSEX-GENDER DEBATE Ge Pol SciPrachiPas encore d'évaluation

- Soc. Sci 2Document100 pagesSoc. Sci 2Maraia Claudette ReyesPas encore d'évaluation

- Gender PresentationDocument35 pagesGender Presentation00062481Pas encore d'évaluation

- Feminist Theology NotesDocument10 pagesFeminist Theology NotesTaz KuroPas encore d'évaluation

- MG Test AnswerDocument4 pagesMG Test AnswerK41RashiGuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Reviewer Genger and Society Kulturang Popular - 124330Document44 pagesReviewer Genger and Society Kulturang Popular - 124330marj salesPas encore d'évaluation

- History of SOcial COnstructionismDocument6 pagesHistory of SOcial COnstructionismZarnish HussainPas encore d'évaluation

- Women Studies: Submitted byDocument6 pagesWomen Studies: Submitted bysangeetha ramPas encore d'évaluation

- Anna Shaw Dr. Shannon Walsh GSRP 10.24.17Document3 pagesAnna Shaw Dr. Shannon Walsh GSRP 10.24.17Anna Marie ShawPas encore d'évaluation

- Ucsp Group 1Document119 pagesUcsp Group 1Dorothy PulidoPas encore d'évaluation

- Gender and Society 1Document24 pagesGender and Society 1John Syvel QuintroPas encore d'évaluation

- "Natural, But Not Normal? Or, Normal, But Not Natural?": The Gender Free Baby Kristianne C. AnorDocument10 pages"Natural, But Not Normal? Or, Normal, But Not Natural?": The Gender Free Baby Kristianne C. AnorjustchippingPas encore d'évaluation

- Gender and Society M1Document24 pagesGender and Society M1Larsisa MapaPas encore d'évaluation

- Public HealthDocument8 pagesPublic HealthThess Cahigas - NavaltaPas encore d'évaluation

- A Womens PlaceDocument20 pagesA Womens Placeapi-358958938Pas encore d'évaluation

- Sex and GenderDocument2 pagesSex and GenderstreakofmadnessPas encore d'évaluation

- Concepts On Gender and Sex and Other Important Concepts in Gender StudiesDocument22 pagesConcepts On Gender and Sex and Other Important Concepts in Gender StudiesPetersonPas encore d'évaluation

- Essay1 FirstDocument6 pagesEssay1 Firstapi-272917333Pas encore d'évaluation

- BFTQ PatriarchyDocument41 pagesBFTQ PatriarchySaniza BanerjeePas encore d'évaluation

- Social Construction of GenderDocument19 pagesSocial Construction of GenderZoya ZubairPas encore d'évaluation

- Ndersociety g3Document4 pagesNdersociety g3John mark ObiadoPas encore d'évaluation

- Gender, Culture and Folklore: Aili NenolaDocument22 pagesGender, Culture and Folklore: Aili NenolaAnFarhanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Gas Lesson 4Document2 pagesGas Lesson 4ClarkPas encore d'évaluation

- Race and Gender Are Social Constructs: Sally Haslanger: Feminist Metaphysics (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)Document4 pagesRace and Gender Are Social Constructs: Sally Haslanger: Feminist Metaphysics (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)Poet CruzPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 2Document8 pagesChapter 2Mae PalanasPas encore d'évaluation

- How To Write A Thesis On Gender RolesDocument4 pagesHow To Write A Thesis On Gender Rolestehuhevet1l2100% (2)

- Gender CommunicationDocument16 pagesGender Communicationnobita537663Pas encore d'évaluation

- Sociology EssayDocument3 pagesSociology EssayToby HudsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction To Gender StudiesDocument11 pagesIntroduction To Gender StudiesNzube NwosuPas encore d'évaluation

- Postmodernism and FeminismDocument22 pagesPostmodernism and FeminismarosecellarPas encore d'évaluation

- Sex and SocietyDocument16 pagesSex and SocietySimeon Tigrao CokerPas encore d'évaluation

- Trans People and The Dialectics of Sex and Gender - Alyx - IoDocument11 pagesTrans People and The Dialectics of Sex and Gender - Alyx - IoKrabby KondoPas encore d'évaluation

- Me and Femininity in A Patriarchal SocietyDocument10 pagesMe and Femininity in A Patriarchal Societyapi-702729842Pas encore d'évaluation

- Feminism and GenderDocument10 pagesFeminism and GenderriyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Sociology ProjectDocument14 pagesSociology ProjectRaghavendra NadgaudaPas encore d'évaluation

- Social Construction of Masculinity and FDocument11 pagesSocial Construction of Masculinity and FnehaPas encore d'évaluation

- Socio 102 Gender and Society HandoutDocument25 pagesSocio 102 Gender and Society HandoutJ4NV3N G4M1NGPas encore d'évaluation

- Gwsmidterm PDFDocument9 pagesGwsmidterm PDFpluto nashPas encore d'évaluation

- Proposal FinalDocument6 pagesProposal Finalapi-341209146Pas encore d'évaluation

- Women and ChildrenDocument2 pagesWomen and ChildrenJustine Mae BantilanPas encore d'évaluation

- Social Construction of GenderDocument11 pagesSocial Construction of GenderKumar Gaurav100% (2)

- Ciccariello-Maher, George, & Jeff St. Andrews - Every Crook Can Govern. Prison Rebellions As A Window To The New WorldDocument12 pagesCiccariello-Maher, George, & Jeff St. Andrews - Every Crook Can Govern. Prison Rebellions As A Window To The New Worldsp369707Pas encore d'évaluation

- Sison v. Ancheta, 130 SCRA 654, G.R. L-59431Document7 pagesSison v. Ancheta, 130 SCRA 654, G.R. L-59431Arkhaye SalvatorePas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 1: Introducing Social Psychology & MethodologyDocument7 pagesChapter 1: Introducing Social Psychology & MethodologyJolene Marcus LeePas encore d'évaluation

- The Legacy of J JayalalithaaDocument2 pagesThe Legacy of J JayalalithaaSHOEJOYPas encore d'évaluation

- Reflection On The Book - Catholic Social Teaching Our Best Kept SecretDocument5 pagesReflection On The Book - Catholic Social Teaching Our Best Kept Secreteshter01Pas encore d'évaluation

- Leaflet On The 18th July Incident in Maruti Suzuki ManesarDocument2 pagesLeaflet On The 18th July Incident in Maruti Suzuki ManesarSatyam VarmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Color of WaterDocument9 pagesColor of Waterbreezygurl23Pas encore d'évaluation

- Reservation System in IndiaDocument50 pagesReservation System in IndiaVivek BhardwajPas encore d'évaluation

- Untouchability and Dalit Womens OppressionDocument2 pagesUntouchability and Dalit Womens OppressionYogesh KumarPas encore d'évaluation

- The Position of The UnthoughtDocument20 pagesThe Position of The UnthoughtJota MombaçaPas encore d'évaluation

- SOCIAL SCIENCES Quiz Bee 2019Document4 pagesSOCIAL SCIENCES Quiz Bee 2019Romeo Castro De Guzman100% (2)

- Chapter 3 Lesson 2 Becoming A Global TeacherDocument9 pagesChapter 3 Lesson 2 Becoming A Global TeacherAnthony Chan100% (3)

- In 1885, Mary Tape Had WrittenDocument1 pageIn 1885, Mary Tape Had WrittenSkittles VanportfleetPas encore d'évaluation

- Checklists Clin Exam Cns Sensory SystemDocument2 pagesChecklists Clin Exam Cns Sensory SystemSami ShouraPas encore d'évaluation

- City of Kamloops Arbitration ResultsDocument26 pagesCity of Kamloops Arbitration ResultsChristopherFouldsPas encore d'évaluation

- UP Law Complex PublicationsDocument8 pagesUP Law Complex PublicationsJr Dela CernaPas encore d'évaluation

- Masculine SpacesDocument9 pagesMasculine SpacesKapil Sikka100% (1)

- HedonismDocument41 pagesHedonismAli Abdullah MalhiPas encore d'évaluation

- EXTRA - Kobold Guide To GamemasteringDocument156 pagesEXTRA - Kobold Guide To Gamemasteringlascosas530587% (15)

- English 9 ExamDocument20 pagesEnglish 9 ExamMi Na Alamada EscabartePas encore d'évaluation

- Gender Fair LanguageDocument4 pagesGender Fair Languageairamendoza1212Pas encore d'évaluation

- Black LiberationDocument401 pagesBlack LiberationKader Kulcu100% (4)

- The Kritik: Kritik: Noun - in The Philosophical Context, Kritik (Or Critique) Refers To TheDocument4 pagesThe Kritik: Kritik: Noun - in The Philosophical Context, Kritik (Or Critique) Refers To TheNathan JohnstonPas encore d'évaluation

- p9.5 - Unfpa ManualDocument273 pagesp9.5 - Unfpa ManualYash RamawatPas encore d'évaluation

- Quantitative Techniques & Data Interpretation: QA13CMATSP01Document4 pagesQuantitative Techniques & Data Interpretation: QA13CMATSP01Meenakshi SachdevPas encore d'évaluation

- Cognitive BiasesDocument35 pagesCognitive BiasesAlicia Melgar Galán100% (1)

- Directions: This Quiz Is Composed of True/false, Multiple Choice, and Short Answer QuestionsDocument2 pagesDirections: This Quiz Is Composed of True/false, Multiple Choice, and Short Answer Questionscara_fiore2100% (2)

- Salient Features of The Barangay VAW DeskDocument68 pagesSalient Features of The Barangay VAW DeskRANI MARTINPas encore d'évaluation

- Annotated BibliographyDocument9 pagesAnnotated BibliographygrebsfluwPas encore d'évaluation

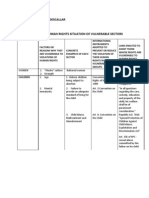

- Human Rights Chap 6-9Document14 pagesHuman Rights Chap 6-9Lucky VastardPas encore d'évaluation

- Never Chase Men Again: 38 Dating Secrets to Get the Guy, Keep Him Interested, and Prevent Dead-End RelationshipsD'EverandNever Chase Men Again: 38 Dating Secrets to Get the Guy, Keep Him Interested, and Prevent Dead-End RelationshipsÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (387)

- Unwanted Advances: Sexual Paranoia Comes to CampusD'EverandUnwanted Advances: Sexual Paranoia Comes to CampusÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (22)

- The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and LoveD'EverandThe Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and LoveÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (384)

- The Masonic Myth: Unlocking the Truth About the Symbols, the Secret Rites, and the History of FreemasonryD'EverandThe Masonic Myth: Unlocking the Truth About the Symbols, the Secret Rites, and the History of FreemasonryÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (14)

- Lucky Child: A Daughter of Cambodia Reunites with the Sister She Left BehindD'EverandLucky Child: A Daughter of Cambodia Reunites with the Sister She Left BehindÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (54)

- Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of IdentityD'EverandGender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of IdentityÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (317)

- Period Power: Harness Your Hormones and Get Your Cycle Working For YouD'EverandPeriod Power: Harness Your Hormones and Get Your Cycle Working For YouÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (25)

- Abolition Democracy: Beyond Empire, Prisons, and TortureD'EverandAbolition Democracy: Beyond Empire, Prisons, and TortureÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (5)

- Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of PlantsD'EverandBraiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of PlantsÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (1424)

- The Longest Race: Inside the Secret World of Abuse, Doping, and Deception on Nike's Elite Running TeamD'EverandThe Longest Race: Inside the Secret World of Abuse, Doping, and Deception on Nike's Elite Running TeamPas encore d'évaluation

- You Can Thrive After Narcissistic Abuse: The #1 System for Recovering from Toxic RelationshipsD'EverandYou Can Thrive After Narcissistic Abuse: The #1 System for Recovering from Toxic RelationshipsÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (16)

- Unlikeable Female Characters: The Women Pop Culture Wants You to HateD'EverandUnlikeable Female Characters: The Women Pop Culture Wants You to HateÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (18)

- Feminine Consciousness, Archetypes, and Addiction to PerfectionD'EverandFeminine Consciousness, Archetypes, and Addiction to PerfectionÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (90)

- The Courage to Heal: A Guide for Women Survivors of Child Sexual AbuseD'EverandThe Courage to Heal: A Guide for Women Survivors of Child Sexual AbusePas encore d'évaluation

- Summary: Fair Play: A Game-Changing Solution for When You Have Too Much to Do (and More Life to Live) by Eve Rodsky: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedD'EverandSummary: Fair Play: A Game-Changing Solution for When You Have Too Much to Do (and More Life to Live) by Eve Rodsky: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- Tears of the Silenced: An Amish True Crime Memoir of Childhood Sexual Abuse, Brutal Betrayal, and Ultimate SurvivalD'EverandTears of the Silenced: An Amish True Crime Memoir of Childhood Sexual Abuse, Brutal Betrayal, and Ultimate SurvivalÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (136)

- The Souls of Black Folk: Original Classic EditionD'EverandThe Souls of Black Folk: Original Classic EditionÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (441)

- The Longest Race: Inside the Secret World of Abuse, Doping, and Deception on Nike's Elite Running TeamD'EverandThe Longest Race: Inside the Secret World of Abuse, Doping, and Deception on Nike's Elite Running TeamÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (60)

- From the Core: A New Masculine Paradigm for Leading with Love, Living Your Truth & Healing the WorldD'EverandFrom the Core: A New Masculine Paradigm for Leading with Love, Living Your Truth & Healing the WorldÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (16)

- Survival Math: Notes on an All-American FamilyD'EverandSurvival Math: Notes on an All-American FamilyÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (13)

- Decolonizing Wellness: A QTBIPOC-Centered Guide to Escape the Diet Trap, Heal Your Self-Image, and Achieve Body LiberationD'EverandDecolonizing Wellness: A QTBIPOC-Centered Guide to Escape the Diet Trap, Heal Your Self-Image, and Achieve Body LiberationÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (22)

- Our Hidden Conversations: What Americans Really Think About Race and IdentityD'EverandOur Hidden Conversations: What Americans Really Think About Race and IdentityÉvaluation : 3 sur 5 étoiles3/5 (4)

- Crones Don't Whine: Concentrated Wisdom for Juicy WomenD'EverandCrones Don't Whine: Concentrated Wisdom for Juicy WomenÉvaluation : 2.5 sur 5 étoiles2.5/5 (3)