Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Self-Concept in Consumer Behavior

Transféré par

nicoleta.corbu51850 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

53 vues15 pagesarticol stiintific

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentarticol stiintific

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

53 vues15 pagesSelf-Concept in Consumer Behavior

Transféré par

nicoleta.corbu5185articol stiintific

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 15

Self-Concept in Consumer Behavior: A Critical Review

Author(s): M. Joseph Sirgy

Source: The Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 9, No. 3 (Dec., 1982), pp. 287-300

Published by: The University of Chicago Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2488624

Accessed: 09/01/2009 17:44

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless

you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you

may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at

http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ucpress.

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed

page of such transmission.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the

scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that

promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The

Journal of Consumer Research.

http://www.jstor.org

Self-Concept i n Consumer Behavi or:

A Cri ti cal Revi ew

M. JOSEPH SIRGY*

The self-concept li terature i n consumer behavi or can be characteri zed as frag-

mented, i ncoherent, and hi ghly di ffuse. Thi s paper cri ti cally revi ews self-concept

theory and research i n consumer behavi or and provi des recommendati ons for

future research.

M ost scholars seem to agree that the term "self-con-

cept" denotes the "totali ty of the i ndi vi dual's

thoughts and feeli ngs havi ng reference to hi mself as an

object" (Rosenberg 1979, p. 7). However, self-concept has

been treated from vari ous poi nts of vi ew. For example,

psychoanalyti c theory vi ews the self-concept as a self-sys-

tem i nfli cted wi th confli ct. Behavi oral theory construes the

self as a bundle of condi ti oned responses. Other vi ews,

such as organi smi c theory, treat the self i n functi onal and

developmental terms; phenomenology treats the self i n a

wholi sti c form; and cogni ti ve theory represents the self as

a conceptual system processi ng i nformati on about the self.

Symboli c i nteracti oni sm, on the other hand, vi ews the self

as a functi on of i nterpersonal i nteracti ons.

Generally, self-concept has been construed from a mul-

ti di mensi onal perspecti ve (Bums 1979; Rosenberg 1979).

A ctual self refers to how a person percei ves herself; i deal

self refers to how a person would li ke to percei ve herself;

and soci al self refers to how a person presents herself to

others. Global self-atti tude (e.g., self-esteem or self-sati s-

facti on) has been treated as a consci ous judgment regardi ng

the relati onshi p of one's actual self to the i deal or soci al

self (Bums 1979; Rogers 1951).1

There seems to be a consensus regardi ng the exi stence

and i ndependent i nfluence of at least two self-concept mo-

ti ves-self-esteem and self-consi stency (Epstei n 1980).

The self-esteem moti ve refers to the tendency to seek ex-

peri ences that enhance self-concept. The self-consi stency

moti ve denotes the tendency for an i ndi vi dual to behave

consi stently wi th her vi ew of herself. Ordi nari ly, these twi n

moti ves are harmoni ous, but under some ci rcumstances,

these same moti ves confli ct (Jones 1973; Schlenker 1975;

Shrauger and Lund 1975).2

PRODUCT SYMBOLISM

In consumer research, Tucker (1957, p. 139) argued that

consumers' personali ti es can be defi ned through product

use:

There has long been an i mpli ci t concept that consumers can

be defi ned i n terms of ei ther the products they acqui re or use,

or i n terms of the meani ngs products have for them or thei r

atti tudes towards products.

Products, suppli ers, and servi ces are assumed to have an

i mage determi ned not only by the physi cal characteri sti cs

of the object alone, but by a host of other factors, such as

packagi ng, adverti si ng, and pri ce. These i mages are also

formed by other associ ati ons, such as stereotypes of the

generali zed or typi cal user (cf. Bri tt 1960; Grubb and

Grathwohl 1967; Levy 1959).

Holman (1981) argued that there are at least three con-

*M. Joseph Si rgy i s A ssi stant Professor of Marketi ng at Vi rgi ni a

Polytechni c Insti tute and State Uni versi ty, Blacksburg, VA 24061. The

author expresses hi s grati tude to the anonymous revi ewers, to Professors

Robert Ferber and Seymour Sudman, and to the JCR staff who helped

develop the fi nal revi si on of thi s paper.

'The structure of the self-concept has been postulated to be characteri zed

along at least ni ne di mensi ons-content, di recti on, i ntensi ty, sali ence,

consi stency, stabi li ty, clari ty, veri fi abi li ty, and accuracy (Rosenberg

1979). Content refers to the i nherent aspects of di sposi ti ons, soci al i denti ty

elements, or physi cal characteri sti cs i nvolved i n the self-pi cture. Di recti on

refers to the posi ti vi ty or negati vi ty of the self-atti tude. Intensi ty refers to

the strength of the self-atti tude. Sali ence refers to the extent to whi ch a

self-atti tude i s i n the forefront of consci ousness. Consi stency i s the extent

to whi ch two or more self-atti tudes of the same i ndi vi dual are contradi c-

tory. Stabi li ty refers to the degree of whi ch a self-atti tude does not change

over ti me. Clari ty denotes the extent to whi ch a parti cular self-concept or

self-pi cture i s sharp and unambi guous. Veri fi abi li ty refers to the extent to

whi ch a gi ven self-concept i s potenti ally testable or veri fi able. A ccuracy

i s the extent to whi ch a gi ven self-concept reflects one's true di sposi ti on.

2In addi ti on to thi s di scussi on of the self-concept moti ves, the devel-

opment of the self-concept was di scussed by Rosenberg (1979). He refers

to four self-concept formati on pri nci ples-reflected apprai sals, soci al com-

pari sons, self-attri buti ons, and psychologi cal centrali ty. Each of these

pri nci ples gui des the development of an i ndi vi dual's self-concept. The

reflected apprai sal pri nci ple refers to the formati on of self-concepts based

on others' percepti ons of oneself. The soci al compari son pri nci ples refers

to the i nfluence of one's evaluati on of oneself by compari ng oneself to

si gni fi cant others. The self-attri buti on pri nci ple refers to the noti on that

self-concepts are i nferred from one's own behavi or. A nd the pri nci ple of

psychologi cal centrali ty refers to the hi erarchi cal organi zati on of the self-

concepts.

287

? JOURNA L OF CONSUMER RESEA RCH * Vol. 9 * December 1982

288 THE JOURNA L OF CONSUMER RESEA RCH

di ti ons that di sti ngui sh products as communi cati on vehi -

cles-vi si bi li ty i n use, vari abi li ty i n use, and personali za-

bi li ty. For a product to have personali ty associ ati ons, i t has

to be purchased and/or consumed conspi cuously or vi si bly.

Vari abi li ty i n use i s also i mportant because wi thout vari -

abi li ty, no di fferences among i ndi vi duals can be i nferred

on the basi s of product use. The personali zabi li ty of the

product denotes the extent to whi ch the use of a product

can be attri buted to a stereotypi c i mage of the generali zed

user. Si rgy (1979, 1980) used the personali zabi li ty char-

acteri sti c as a moderati ng vari able i n a self-concept study.

Munson and Spi vey (1980, 1981) used Katz's (1960)

"value-expressi veness" to argue for the effect of product

symboli sm on the acti vati on of consumer self-concept i n

consumpti on-related si tuati ons.

A t least four di fferent approaches can be i denti fi ed i n

self-concept studi es that deal di rectly wi th product i mage:

(1) product i mage as i t relates to the stereotypi c i mage of

the generali zed product user; (2) product i mage i n di rect

associ ati on wi th the self-concept; (3) sex-typed product i m-

age; and (4) di fferenti ated product i mages.

Many self-concept i nvesti gators argue that a product i m-

age' i s, i n essence, defi ned as the stereotypi c i mage of the

generali zed product user, usually measured on a semanti c

di fferenti al scale (e.g., Grubb and Hupp 1968; Grubb and

Stern 1971; Schewe and Di llon 1978). Other studi es mea-

sure product i mage di rectly usi ng the semanti c di fferenti al

type of methodology (e.g., Bi rdwell 1968; Munson and

Spi vey 1981; Ross 1971; Samli and Si rgy 1981; Si rgy 1979,

1980, 1981a; Si rgy and Danes 1981).

The measurement of the product i mage i n di rect associ -

ati on wi th the self-concept has employed a product-an-

chored Q-methodology. The respondent i s asked to i ndi cate

the extent to whi ch a speci fi c product i s associ ated wi th her

actual self-concept, i deal self-concept, and so forth (e.g.,

Belch and Landon 1977; Greeno, Sommers, and Kernan

1973; Landon 1974; Marti n 1973; Sommers 1964).

Sex-typed product i mage i s restri cted to those symboli c

attri butes di rectly associ ated wi th sex roles. Thi s concept

has usually been measured usi ng a bi polar

masculi ni ty-femi ni ni ty rati ng or ranki ng scale (e.g., Gentry

and Doeri ng 1977; Gentry, Doeri ng, and O'Bri en 1978;

Vi tz and Johnston 1965). Other studi es, such as Golden,

A lli son, and Clee (1979) and A lli son et al. (1980), have

employed two i ndependent constructs to measure masculi n-

i ty, femi ni ni ty, and psychologi cal androgeny i n product

percepti ons. Subjects were asked to i ndi cate the extent to

whi ch a speci fi c product i s masculi ne on a rati ng scale

rangi ng from "not at all masculi ne" to "extremely mas-

culi ne." The same product was then rated along a si mi lar

"femi ni ni ty" scale. A lli son et al. (1980) found that the

majori ty of thei r respondents percei ved masculi ne and fem-

i ni ne product i mages as two separate constructs rather than

as one di mensi on (cf. Bem 1974).

Munson and Spi vey (1980, 1981) brought out the noti on

that product i mages can be acti vated i n vari ous forms. Two

possi ble "product-expressi ve" self-constructs i nvolve (1)

self-percepti on gi ven a product preference-defi ned as how

one percei ves oneself gi ven a preference for a speci fi c prod-

uct, and (2) others' percepti on of self gi ven a product pref-

erence-defi ned as how a person beli eves other people vi ew

her gi ven a preference for a speci fi c product. However,

results showed that consumers may not be able to di sti n-

gui sh between thei r "own" feeli ngs about a product and

thei r beli efs about how they are vi ewed by others (cf. Lo-

cander and Spi vey 1978).

SELF-CONCEPT IN CONSUMER

BEHA VIOR

There i s ambi gui ty and confusi on on the preci se concep-

tuali zati on of self-concept i n the consumer behavi or li ter-

ature. A number of i nvesti gators have di scussed self-con-

cept as a si ngle vari able and have treated i t as the actual

self-concept-i .e., as the percepti on of oneself (e.g., Bel-

lenger, Stei nberg, and Stanton 1976; Bi rdwell 1968; Green,

Maheshwari , and Rao 1969; Grubb and Hupp 1968; Grubb

and Stern 1971). In thi s vei n, self-concept has been labeled

"actual self," "real self," "basi c self,'' "extant self," or

si mply "self." Wi thi n the si ngle self-construct tradi ti on,

some i nvesti gators have restri cted self-concept to percei ved

sex-role (e.g., Gentry and Doeri ng 1977; Gentry, Doeri ng,

and O'Bri en 1978; Golden et al. 1979).

More recently, Si rgy (1982a, 1982b) has employed the

constructs of self-i mage value-the degree of value at-

tached to a speci fi c actual self-concept (a concept parallel

to i deal self-concept), and self-i mage beli ef-the degree of

beli ef or percepti on strength associ ated wi th a self-i mage

(a concept equi valent to the actual self-concept). Further-

more, Schenk and Holman (1980) have argued for the con-

si derati on of the si tuati onal self-i mage, defi ned as the result

of the i ndi vi dual's repertoi re of self-i mage and the percep-

ti on of others i n a speci fi c si tuati on.

In the multi ple self-constructs tradi ti on, self-concept has

been conceptuali zed as havi ng more than one component.

Some i nvesti gators have argued that self-concept must be

treated as havi ng two components-the actual self-concept

and the i deal self-concept, defi ned as the i mage of oneself

as one would li ke to be (e.g., Belch 1978; Belch and Lan-

don 1977; Delozi er 1971; Delozi er and Ti llman 1972; Dol-

i ch, 1969). The i deal self-concept has been referred to as

the "i deal self," "i deali zed i mage," and "desi red self."

Other i nvesti gators have gone beyond the duali ty di men-

si on. Si rgy (1979, 1980) referred to actual self-i mage, i deal

self-i mage, soci al self-i mage, and i deal soci al self-i mage.

The soci al self-concept (someti mes referred to as "looki ng-

glass self" or "presenti ng self") has been defi ned as the

i mage that one beli eves others hold, whi le the i deal soci al

self-concept (someti mes referred to as "desi red soci al

self") denotes the i mage that one would li ke others to hold

(cf. Maheshwari 1974). Hughes and Guerrero (1971) talked

about the actual self-concept and the i deal soci al self-con-

cept. French and Glaschner (1971) used the actual self-

concept, the i deal self-concept, and the "percei ved refer-

ence group i mage of self" (thi s latter concept was never

formally defi ned). Dornoff and Tatham (1972) referred to

the actual self-concept, i deal self-concept, and "i mage of

SELF-CONCEPT IN CONSUMER BEHA VIOR 289

best fri end." Sommers (1964) used the actual self-concept

and "descri bed other," defi ned "as i f I were thi s person."

Sanchez, O'Bri en, and Summers (1975), on the other hand,

employed the actual self-concept, i deal self-concept, and

the "expected self," whi ch refers to that i mage somewhere

between the actual and the i deal self-concept. Munson and

Spi vey (1980) referred to the "expressi ve self," whi ch per-

tai ns to ei ther the i deal self-concept or the soci al self-con-

cept.

Self-Concept Theori es

Levy (1959) argued that the consumer i s not functi onally

ori ented and that her behavi or i s si gni fi cantly affected by

the symbols encountered i n the i denti fi cati on of goods i n

the marketplace. Hi s argument, although not regarded as

consti tuti ng a theory, di d serve to sensi ti ze consumer be-

havi or reserachers to the potenti al i nfluence of consumers'

self-concepts on consumpti on behavi or.

Followi ng Levy's proposi ti on, a number of self-concept

models were formulated to descri be, explai n, and predi ct

the preci se role of consumers' self-concepts i n consumer

behavi or. Rooted i n Rogers' (1951) theory of i ndi vi dual

self-enhancement, Grubb and Grathwohl (1967) speci fi ed

that:

1. Self-concept i s of value to the i ndi vi dual, and behavi or

wi ll be di rected toward the protecti on and enhancement

of self-concept.

2. The purchase, di splay, and use of goods communi cates

symboli c meani ng to the i ndi vi dual and to others.

3. The consumi ng behavi or of an i ndi vi dual wi ll be di rected

toward enhanci ng self-concept through the consumpti on

of goods as symbols.

Schenk and Holman's (1980) vi ew of si tuati onal self-

i mage i s based on the symboli c i nteracti oni sm school of

thought. They defi ned si tuati onal self-i mage as the meani ng

of self the i ndi vi dual wi shes others to have. Thi s si tuati on-

speci fi c i mage i ncludes atti tudes, percepti ons, and feeli ngs

the i ndi vi dual wi shes others to associ ate wi th her. The

choi ce of whi ch self (actual self, and so on) to express i s

i nfluenced by the speci fi c characteri sti cs of a gi ven si tua-

ti on. Once an i ndi vi dual deci des whi ch i mage to express

i n the soci al si tuati on, she looks for ways of expressi ng i t.

The use of products i s one means by whi ch an i ndi vi dual

can express self-i mage. Thus, products that are conspi cu-

ous, that have a hi gh repurchase rate, or for whi ch di ffer-

enti ated brands are avai lable mi ght be used by consumers

to express self-i mage i n a gi ven si tuati on.

The advantages of the concept of si tuati onal self-i mage

are that (1) i t replaces the proli ferati ng concepts of actual

self-i mage, i deal self-i mage, and so forth; (2) i t i ncludes

a behavi oral component; and (3) i t acknowledges that con-

sumers have many self-concepts. Consumpti on of a brand

may be hi ghly congruent wi th self-i mage i n one si tuati on

and not at all congruent wi th i t i n another.

More recently, Si rgy developed a self-i mage/product-i m-

age congrui ty theory (1981a, 1982a, 1982b). Product cues

i nvolvi ng i mages usually acti vate a self-schema i nvolvi ng

the same i mages. For example, a product havi ng an i mage

of "hi gh status" may acti vate both a self-schema i nvolvi ng

the self-concept "I" and a correspondi ng li nkage between

that self-concept and the i mage attri bute (self-i mage) i n-

volvi ng "status." Thi s li nkage connects the self-concept

"I" wi th the "status" self-i mage and i s referred to as self-

i mage beli ef. The self-i mage beli ef may be ei ther "I am a

hi gh status person" or "I am not a hi gh status person."

Self-i mage beli efs are characteri zed by (1) the degree of

beli ef strength connecti ng the self-concept "I" wi th a par-

ti cular self-i mage level, and (2) the value i ntensi ty associ -

ated wi th the self-i mage level (e.g., "I li ke bei ng the hi gh

status type").3

Gi ven the acti vati on of a self-schema as a result of a

product cue, Si rgy clai ms that the value placed on the prod-

uct and i ts i mage attri butes wi ll be i nfluenced by the evoked

self-schema. For i nstance, i f the product i s a luxury auto-

mobi le and i ts foremost i mage i s a "hi gh status" one, i t

can be argued that the value i nferred for the automobi le's

"hi gh status" i mage depends on the preci se nature of the

evoked self-i mage di mensi on i nvolvi ng "status." If "hi gh

status" has a posi ti ve value on the evoked self-i mage di -

mensi on, then thi s posi ti ve value wi ll be projected to the

product; i f "hi gh status" has a negati ve value, then a neg-

ati ve value wi ll be projected to the product i mage. What

i s bei ng argued here i s that the value or "meani ng" of a

product i mage i s not i ndependently deri ved but i s, rather,

i nferred from evoked self-i mage di mensi ons.

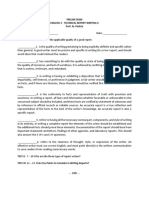

A s Exhi bi t 1 i ndi cates, a speci fi c value-laden self-i mage

beli ef i nteracts wi th a correspondi ng value-laden product-

i mage percepti on, and the result occurs i n the form of:

* Posi ti ve self-congrui ty-compari son between a posi ti ve

product-i mage percepti on and a posi ti ve self-i mage beli ef

* Posi ti ve self-i ncongrui ty-compari son between a posi ti ve

product-i mage percepti on and a negati ve self-i mage beli ef

* Negati ve self-congrui ty-compari son between a negati ve

product-i mage percepti on and a negati ve self-i mage beli ef

* Negati ve self-i ncongrui ty-compari son between a nega-

ti ve product-i mage percepti on and a posi ti ve self-i mage

beli ef.

These di fferent self-i mage/product-i mage congrui ty states

wi ll i nfluence purchase moti vati on di fferently. Posi ti ve self-

congrui ty wi ll determi ne the strongest level of purchase

moti vati on, followed by posi ti ve self-i ncongrui ty, negati ve

self-congrui ty, and negati ve self-i ncongrui ty, respecti vely.

Thi s relati onshi p i s explai ned through the medi ati on of self-

esteem and self-consi stency needs.

From a self-esteem perspecti ve, the consumer wi ll be

moti vated to purchase a posi ti vely valued product to mai n-

tai n a posi ti ve self-i mage (posi ti ve self-congrui ty condi ti on)

or to enhance herself by approachi ng an i deal i mage (pos-

i ti ve self-i ncongrui ty condi ti on). The consumer wi ll be

moti vated to avoi d purchasi ng a negati vely valued product

3The strength of the self-i mage beli ef parallels the tradi ti onal construct

of the actual self-concept, whereas the value i ntensi ty of the self-i mage

beli ef seems to be aki n to the tradi ti onal construct of i deal self-concept

(Si rgy, forthcomi ng).

290 THE JOURNA L OF CONSUMER RESEA RCH

EXHIBIT 1

THE EFFECTS OF SELF-ESTEEM A ND SELF-CONSISTENCY MOTIVES ON PURCHA SE MOTIVA TION

Medi ati ng factors

Self i mage & Product i mage result Self-i mage/ Self-esteem Self-consi stency Purchase

i n product-i mage moti vati on moti vati on moti vati on

congrui ty

leadi ng to

posi ti ve posi ti ve posi ti ve self- approach approach approach

congrui ty purchase

moti vati on

negati ve posi ti ve posi ti ve self- approach avoi dance confli ct

i ncongrui ty

negati ve negati ve negati ve self- avoi dance approach confli ct

congrui ty

posi ti ve negati ve negati ve self- avoi dance avoi dance avoi dance

i ncongrui ty purchase

moti vati on

to avoi d self-abasement (negati ve self-congrui ty and self-

i ncongrui ty condi ti ons). Self-consi stency, on the other

hand, predi cts that the consumer wi ll be moti vated to pur-

chase a product wi th an i mage (posi ti ve or negati ve) that

i s congruent wi th her self-i mage beli ef. Thi s functi ons to

mai ntai n consi stency between behavi or and self-i mage be-

li efs (posi ti ve and negati ve self-congrui ty condi ti ons) and

to avoi d di ssonance generated from behavi or/self-i mage

beli ef di screpanci es (posi ti ve and negati ve self-i ncongrui ty

condi ti ons). The resultant moti vati onal state toward a gi ven

product i s thus the net effect of the moti vati onal state ari si ng

from self-esteem and self-consi stency needs.

Self-Concept Measurement

One of the earli est attempts i n consumer self-concept

measurement was by Sommers (1964). The procedure used

was a Q-sort, whi ch groups products on di mensi ons such

as "most li ke me" to "least li ke me." Sommers' study

provi ded an i ni ti al nomologi cal vali dati on of thi s procedure.

Many self-concept i nvesti gati ons have employed the Q-

sort methodology wi th relati ve nomologi cal success

(Greeno et al. 1973; Hamm 1967; Hamm and Cundi ff 1969;

Marti n 1973). Belch and Landon (1977) modi fi ed the Q-

sort by usi ng a rati ng scale wi th a predetermi ned di stri bu-

ti on. The methodology was relati vely successful i n the

nomologi cal studi es conducted by Landon and hi s associ -

ates (Belch 1978; Belch and Landon 1977; Landon 1972,

1974). A more tradi ti onal Q-sort procedure was used i n

several studi es i n whi ch personali ty adjecti ves were sorted

along a self-concept di mensi on such as "most li ke me" to

"least li ke me" (French and Glaschner 1971; Sanchez et

al. 1975).

A nother tradi ti on i n self-concept measurement i nvolves

the semanti c di fferenti al. Thi s method entai ls havi ng the

respondent rate a speci fi c self-perspecti ve-actual self-con-

cept, for example-along a number of bi polar adjecti ve

scales (e.g., Bellenger et al. 1976; Bi rdwell 1968; Delozi er

1971; Doli ch 1969).

Other mi scellaneous measures have also been used to tap

the self-concept. These i nclude the adjecti ve check li st

(Guttman 1973), self-report atti tudi nal i tems measured on

a Li kert-type scale (Jacobson and Kossoff 1963), and other

standardi zed sex-role atti tude measures (Gentry and Doer-

i ng 1977; Gentry et al. 1978; Golden et al. 1979; Morri s

and Cundi ff 1971; Vi tz and Johnston 1965).

Self-Concept Research

A t least fi ve research tracks di rectly related to self-con-

cept have been i denti fi ed:

Self-Concept and Soci o-Psychologi cal Factors. Sommers

(1964) attempted to di fferenti ate consumers who vary i n

soci al strati fi cati on (SES) by usi ng self-concept measured

i n terms of products. A probabi li ty sample of 100 house-

wi ves and 10 generi c products yi elded results that were

basi cally consi stent wi th the followi ng hypotheses:

* Members of a hi gh SES stratum (H) descri be self si gni f-

i cantly di fferently than do members of a low stratum (L).

* Members of L demonstrate greater agreement i n descri bi ng

self than do members of H.

* Members of H demonstrate greater agreement i n descri b-

i ng other consumers than i n descri bi ng self.

* Members of L demonstrate greater agreement i n self de-

scri pti on

than do members of H.

Marti n (1973) and Greeno et al. (1973) attempted to di f-

ferenti ate consumers wi th varyi ng personali ti es by usi ng

self-concept measured i n terms of products. Marti n's study

employed a nonprobabi li ty sample of 223 students, together

wi th two sets of 50 products (one for each sex) from a Sears

Catalog. Marti n's study revealed three female clusters (per-

SELF-CONCEPT IN CONSUMER BEHA VIOR 291

sonal hygi ene, noncommi tted, and li berated) and fi ve male

clusters, of whi ch only three were reasonably i nterpretable

(conservati ve, reli gi ous, and personal hygi ene). Greeno et

al.'s study, whi ch used a probabi li ty sample of 190 house-

wi ves wi th 38 generi c products, produced si x female clus-

ters (homemakers, matri archs, vari ety gi rls, ci nderellas,

glamour gi rls, and medi a-consci ous glamour gi rls). No si g-

ni fi cant overlap was vi si ble between the female clusters i n

the two studi es, but thi s could have been due to the di fferent

populati ons (female students versus housewi ves).

Consumer Behavi or as a Functi on of Self-Concept/Prod-

uct-Image Congrui ty. The di scussi on of actual self-i mage

and product-i mage congrui ty was i ni ti ated by Gardner and

Levy (1955) and Levy (1959). The mai n attenti on was fo-

cused upon the i mage projected by vari ous products. Con-

sumers were thought to prefer products wi th i mages that

were congruent wi th thei r self-concepts.

Exhi bi t 2 i ncludes most of the studi es that have exami ned

the relati onshi p between self-concept/product-i mage con-

grui ty and consumer behavi or. The fi ndi ngs of these studi es

can be summari zed as follows:

1. The relati onshi p between actual self-i mage/product-i m-

age4 congrui ty (self-congrui ty) and consumer choi ce

(i .e., product preference, purchase i ntenti on, and/or

product usage, ownershi p, or loyalty) has been supported

by numerous studi es. Those studi es whi ch fai led to con-

fi rm thi s relati onshi p were Hughes and Guerrero (1971)

and Green et al. (1969).

2. The relati onshi p between i deal self-i mage/product-i mage

congrui ty (i deal congrui ty) and consumer choi ce (i .e.,

product preference, purchase i ntenti on, product usage,

ownershi p or loyalty) has been generally supported.

3. The relati onshi p between soci al self-i mage/product-i m-

age congrui ty (soci al congrui ty) and consumer choi ce

(li mi ted to product preference, purchase i ntenti on, and

store loyalty) has not been strongly supported (Mahesh-

wari 1974; Samli and Si rgy 1981; Si rgy 1979, 1980).

4. The relati onshi p between i deal soci al self-i mage/prod-

uct-i mage congrui ty (i deal soci al congrui ty) and con-

sumer choi ce (li mi ted to product preference, purchase

i ntenti on, and store loyalty) has been moderately sup-

ported (Maheshwari 1974; Samli and Si rgy 1981; Si rgy

1979, 1980).

5. The relati onshi p between sex-role self-i mage/sex-typed

product-i mage congrui ty (sex-role congrui ty) and con-

sumer choi ce (li mi ted only to product usage) has been

moderately supported (Gentry et al. 1978; Vi tz and John-

ston 1965).

6. The moderati ng role of product conspi cuousness5 on the

relati onshi p between self-concept/product-i mage con-

gru-i ty6 and consumer choi ce (li mi ted to product prefer-

ence, purchase i ntenti on, and/or product usage) has been

largely unsupported (Doli ch 1969; Ross 1971; Si rgy

1979). That i s, i t was expected that the i deal and/or

i deal-soci al self-concepts would be more closely related

to product preference wi th respect to hi ghly conspi cuous

products than to the actual and/or soci al self-concepts.

Wi th respect to i nconspi cuous products, i t was expected

that the actual and/or soci al self-concept would be more

closely related to product preference than to the i deal

and/or i deal-soci al self-components.

7. The moderati ng role of product conspi cuousness-soci al

class i nteracti on on the relati onshi p between self-con-

cept/product-i mage congrui ty and consumer choi ce (li m-

i ted only to product preference) has been suggested by

Munson's (1974) study. Hi s results showed that prefer-

ence for conspi cuous products was related to i deal self-

concept for upper soci al class respondents, whereas pref-

erence for lower class respondents was not related to

ei ther actual or i deal self-concepts for ei ther conspi cuous

or i nconspi cuous products.

8. The moderati ng role of product personali zati on7 on the

relati onshi p between self-concept/product-i mage con-

grui ty and consumer choi ce (li mi ted only to product

preference and purchase i ntenti on) has been suggested

by Si rgy (1979, 1980). That i s, the relati onshi p between

self-concept/product-i mage congrui ty and product pref-

erence and purchase i ntenti on seems stronger for hi gh

personali zi ng products than for low personali zi ng prod-

ucts.

9. The moderati ng role of personali ty on the relati onshi p

between self-concept/product-i mage congrui ty and con-

sumer choi ce (li mi ted to purchase i ntenti on) has been

suggested by Belch (1978). Belch's results showed that,

based on Harvey, Hunt and Schroeder's (1961) person-

ali ty typology,8 System 3 subjects' i ntenti ons were more

closely related to i deal self-concept than to actual self-

concept.

4Products as used here are not restri cted to tangi bles, but apply as well

to servi ces, organi zati ons, persons, and so on.

5Product conspi cuousness i s defi ned as the extent to whi ch a speci fi c

product i s consumed i n publi c-i .e., the extent of hi gh soci al vi si bi li ty or

hi gh conspi cuousness.

6Self-concept i s used here i n the broad sense, thus denoti ng any of the

self-perspecti ves, e.g., actual self-concept, i deal self-concept, soci al self-

concept.

7Product personali zati on refers to the extent to whi ch a product has

strong i mage or symboli c associ ati ons. Products that are hi ghly person-

ali zi ng are those whi ch have strong stereotypi c i mages for the general

user. Thi s di mensi on i s analogous to the di sti ncti on between value-ex-

pressi ve products (hi gh product personali zati on) and uti li tari an-expressi ve

products (low product personali zati on) made by Locander and Spi vey

(1978) and Spi vey (1977).

8Harvey, Hunt, and Schroeder (1961) presented a personali ty typology

based on the noti on of cogni ti ve complexi ty. Four personali ty types of

beli ef systems were deducted: System 1 persons are those who have a

si mple cogni ti ve structure and a tendency toward extreme, polari zed judg-

ments. They are characteri zed by hi gh absoluti sm, closedness of beli efs,

hi gh evaluati veness, strong adherence to rules, hi gh ethnocentri sm, dog-

mati sm, and authori tari ani sm. System 2 persons can be descri bed as hav-

i ng somewhat more di fferenti ated and abstract beli ef systems. They are

characteri zed by an anti -rule and anti -authori ty ori entati on. They have low

self-esteem and are ali enated. System 3 persons are those who have hi gh

soci al needs. System 4 persons represent the most abstract and least con-

stri cted of the four beli ef system. They are characteri zed by a hi gh task

ori entati on, ri sk taki ng, creati vi ty, and relati vi sm; they are more tolerant

of ambi gui ty and flexi ble i n thought and acti on.

292 THE JOURNA L OF CONSUMER RESEA RCH

EXHIBIT 2

STUDIES RELA TING CONSUMER BEHA VIOR WITH SELF-IMA GE/PRODUCT-IMA GE CONGRUITY

Tpe of Self

-Concept

'

Congrui ty Model refers to the method used i nmeasuri ng the

.A ctual Self _ * | | | * * | * _ | | | * | _ * | | | _ | | _ _ * | | degree of match or mi smatch between the product i mage and the

.

Ideal Self self-concept for a gi venconsumer. For further detai l refer to the

. Soci al Self di scussi onunder "Research Problems."

. Ideal Soci al Self bThe term "product" i s used i nthe broadest sense.

*Sex-Role Self

Image of Best Fri end cGroup-Level A nalysi s refers to a procedure whi ch aggregates

. Percei ved Reference Self _ across subjects across i mage attri butes; Indi vi dual-Level A nalysi s

refers to ananalysi s conducted per subject; and Image-Level A nal-

Self -Concept Measure _ _ ysi s refers to the procedure whi ch aggregates across subjects per

. Semanti c Di fferenti al i mage attri bute.

Q-tael Scales

dA number of i tems i nthese studi es were not

reported.

.Q-Sort

Methodolog--IA E

.Personali ty Inventory

.Experi mentally Mani pulated

Product

Image

Measures

. Semanti c Di fferenti al

Stapel Scales

Q-Sort

Methodology

. MDS

Experi mentally Mani pulated

-

Congrui ty Modela

.Eucli dean

.A bsolute Di fference

. Si mple Di fference

Di fference Squared

Di vi si onal Di fference

Correlati on Coeffi ci ent

MeanDi fference

Factor

A nalysi s

.Experi mentally Mani pulated -

.Other

Dependent Vari able(s)b

. Product P reference

Purchase Intenti on

Prmduct Choi ce

. Product Ownershi I

. Product Usaqe

.

Product Loyalty

Moderator Vari able(s)

P Prduct

Conspi cuousnessIM

Product Sex-Typi ng

.Product Personali zati on

*Si gni fi cant Others

.A tti tude vs Behavi or

-

Product Ownershi p

. Soci al Class

Sex

Self-Confi dence

Personali ty Type

Sample Populati on

. StudenProduct Users

.General roduct Users

*Students

* eneral Publi c

H ousewi ves

B usi nesspersons

Products

.Brand Products

.Generi c Products

B rand Stores

G eneri c Stores

*A cti vi ti es

*Servi ces

Type of A nalysi sc

Gmrup Level

Indi vi dui al Level

=* Img Level

SELF-CONCEPT IN CONSUMER BEHA VIOR 293

10. The moderati ng role of personali ty-product conspi cu-

ousness i nteracti on on the relati onshi p between self-con-

cept/product-i mage congrui ty and consumer choi ce (li m-

i ted to product preference) was suggested by Munson's

(1974) di ssertati on results. Munson used Horney's

(1937) personali ty typology. The results showed that for

compli ant subjects, preference was somewhat more

closely related to actual than to i deal self-concept for

i nconspi cuous products. Wi th respect to both compli ant

and aggressi ve subjects, preference was more closely

related to the i deal than to actual self-concept for con-

spi cuous products. No clear pattern was revealed wi th

respect to the detached subjects.

11. The moderati ng role of type of deci si on on the relati on-

shi p between self-concept/product-i mage congrui ty and

consumer choi ce (li mi ted to product preference, pur-

chase i ntenti on, and store selecti on) has been suggested

by the fi ndi ngs of Si rgy (1979, 1980) and Domoff and

Tatham (1972). Si rgy's results showed that the i deal and

i deal-soci al self-concepts were more closely related to

product preference than to purchase i ntenti on, whereas

the actual and soci al self-concepts were more closely

related to purchase i ntenti on than to product preference.

However, thi s expected fi ndi ng di d not generali ze across

all products. Dornoff and Tatham found that for routi n-

i zed deci si ons (supermarket shoppi ng), actual self-con-

cept was more closely related to store selecti on than to

i deal self-concept and "i mage of best fri end." For non-

routi ne deci si ons regardi ng speci alty store shoppi ng,

"i mage of best fri end" was more closely related to store

selecti on than to actual or i deal self-concepts. Wi th re-

spect to nonrouti ne deci si ons regardi ng department store

shoppi ng, store selecti on was more closely related to

i deal self-concept than to actual self-concept or "i mage

of best fri end."

Consumer Behavi or as a Functi on of Di rect Self-Concept

Influences. Those studi es whi ch explored thi s relati onshi p

have focused thei r attenti on on the effects of self-concept

per se rather than on self-concept/product-i mage congrui ty.

The earli est study i n thi s tradi ti on was conducted by Ja-

cobson and Kossoff (1963), who hypothesi zed that there i s

a di rect relati onshi p between consumers percei vi ng them-

selves as i nnovati ve and thei r atti tudes towards small cars.

Usi ng a self-concept atti tudi nal measure of i nnovati veness

and conservati sm, and based on a probabi li ty sample of 250

respondents, the results showed an opposi te pattern-i .e.,

consumers who saw themselves as bei ng conservati ve were

more li kely to express a posi ti ve atti tude than those who

saw themselves as i nnovati ve.

Guttman (1973) tested the hypothesi s that li ght televi si on

vi ewers percei ve themselves as achi evi ng and acti ve,

whereas heavy vi ewers percei ve themselves as more soci a-

ble. Usi ng 12 personali ty adjecti ves i n an adjecti ve check-

li st format, and based on a probabi li ty sample of 336 female

respondents, the results moderately confi rmed the hypoth-

esi s.

Wi th respect to the speci fi c effects of sex-role self-con-

cepts, Morri s and Cundi ff (1971) explored the moderati ng

role of anxi ety on product preference of hai r spray. Sex-

role self-concept was measured by the femi ni ni ty scale of

the CPI personali ty i nventory on a sample of 223 male

students. The results showed an i nteracti on effect between

sex-role self-concept and anxi ety over preference for hai r

spray. In the same vei n, Gentry and Doeri ng (1977) ex-

ami ned the effects of sex-role self-concept and sex on pref-

erence and usage of 10 lei sure acti vi ti es, 13 products and

thei r related brands, and ni ne magazi ne types and thei r re-

lated brands. Sex-role self-concept was measured usi ng the

femi ni ni ty scales of the CPI and PA Q personali ty i nven-

tori es. Usi ng a sample of 200 students, the results i ndi cated

that sex and sex-role self-concept were si gni fi cant predi c-

tors of preference and usage, but the sex vari able was the

better predi ctor. Si mi lar fi ndi ngs have been obtai ned by

Golden et al. (1979) and by A lli son et al. (1980).

Product Image as a Functi on of Consumer Behavi or. A

number of studi es i n the consumer behavi or li terature have

addressed the relati onshi p between congrui ty effects and

product-i mage percepti ons. Hamm (1967) and Hamm and

Cundi ff (1969) hypothesi zed that self-actuali zati on (as mea-

sured by the di screpancy between actual and i deal self-i m-

ages i n a product-anchored Q-sort) i s related to product-

i mage percepti ons. Usi ng a sample of 100 housewi ves and

50 products, the results provi ded moderate support to the

hypothesi s. In the same vei n, Landon (1972) hypothesi zed

that need for achi evement (as measured by the di screpancy

between actual and i deal self-i mages i n a product-anchored

Q-methodology) i s related to product-i mage percepti ons.

Usi ng a sample of 360 students wi th 12 product categori es,

the results were found to be consi stent wi th the hypothesi s.

In a retai l setti ng and usi ng a sample of 325 female stu-

dents, Mason and Mayer (1970) found that respondents

consi stently rated thei r patroni zed store as hi gh i n status

compared to nonpatroni zed stores. In a study to exami ne

store loyalty determi nants, Samli and Si rgy (1981) i nter-

vi ewed 372 respondents i n two di fferent stores (a di scount

store and a speci alty clothi ng store). One of thei r fi ndi ngs

i nvolved hi gh correlati ons between self-concept/store-i m-

age congrui ty and percepti ons and evaluati ons of functi onal

store-i mage characteri sti cs. Usi ng a sample of 307 students

and 24 products, Golden et al. (1979) and A lli son et al.

(1980) provi ded some suggesti ve evi dence concerni ng the

effects of congruence between sex-role self-concept and

sex-typed product i mage on sex-typed product percepti ons.

Thei r mai n fi ndi ng was an i nteracti on effect between sex-

role self-concept, sex, self-esteem, and product type i n re-

lati on to sex-typed product percepti ons.

It should be noted that although these studi es argued for

a causal type of relati onshi p, they provi ded correlati onal

data from whi ch causal i nferences could not easi ly be made.

Theoreti cally speaki ng, thi s relati onshi p can be explai ned

by what has been referred to i n the soci al psychology li t-

erature as "egocentri c attri buti on" and "attri buti ve projec-

ti on" (Hei der 1958; Holmes 1968; Jones and Ni sbett 1971;

Kelley and Stahelski 1970; Ross, Green, and House 1977).

That i s, attri buti ng a speci fi c i mage to a product can be

very much affected by the person's egocentri ci ty: "I use

294 THE JOURNA L OF CONSUMER RESEA RCH

i t; I am thi s ki nd of person; therefore, the product i mage

has to be li ke me."

Self-Concept as a Functi on of Behavi or Effects. Can

consumer behavi or affect self-percepti ons? Thi s si tuati on

can occur when a product i mage i s strongly establi shed and

consumers' self-concepts are not arti culately formed wi thi n

a speci fi c frame of reference. For example, a consumer may

attri bute hi s usage of a pornographi c magazi ne to hi s strong

need for sexual relati ons. The formati on of the self-i mage

"need for sexual relati ons" may have been affected by the

product i mage associ ated wi th the usage of the porno-

graphi c magazi ne. In soci al psychology, thi s phenomenon

has been explai ned by Bem's self-percepti on theory (1965,

1967).

Indi rect evi dence for thi s relati onshi p exi sts i n the con-

sumer self-concept li terature. Evans (1968) argued that

Bi rdwell's (1968) study showed that product ownershi p

may have i nfluenced both self-concept and product i mage,

resulti ng i n hi gh self-concept/product-i mage congrui ty. The

same argument appli es to the studi es by Grubb and Hupp

(1968), Grubb and Stern (1971), and Schewe and Di llon

(1978).

In an i ndi rect test of thi s relati onshi p, Belch and Landon

(1977) argued that product ownershi p i nfluences self-con-

cept measurement (although thi s was not causally demon-

strated). Furthermore, Delozi er (1971) and Delozi er and

Ti llman (1972) found that self-concept/product-i mage con-

grui ty i ncreased wi th the passage of ti me, whi ch may pos-

si bly be i ndi cati ve of the i nfluence of consumer behavi or

on self-concept changes.

RESEA RCH PROBLEMS

Proli ferati on of Self-Concept Constructs

Researchers have generated numerous constructs i n an

attempt to explai n consumer self-concept effects on con-

sumer choi ce. These i nclude i deal self-i mage, soci al self-

i mage, expected self-i mage, si tuati onal self-i mage, and so

on. The proli ferati on of self-concept constructs not only

sacri fi ces theoreti cal parsi mony but also presents theoreti cal

di ffi culti es i n descri bi ng and explai ni ng the nature of the

i nterrelati onshi p between these constructs. To what extent

are these constructs i ndependent of one another? What i s

the preci se nature of thei r i nteracti on? Under what ci rcum-

stances? Only recently have some of these i ssues been ad-

dressed.

Schenk and Holman (1980) argued that the si tuati onal

self-i mage may offer an i ntegrated and parsi moni ous ap-

proach. The si tuati onal self-i mage i s si tuati on-speci fi c and

takes i nto account the actual self-concept, the i deal self-

concept, and so on. In the same vei n, Si rgy (1981a, 1982a,

1982b, forthcomi ng) and Si rgy and Danes (1981) argued

for the use of self-i mage/product-i mage congrui ty, whi ch

takes i nto account the i nterrelati onshi p between the self and

i deal components of the self-concept, together wi th product

i mage.

Explanatory Use of Self-Concept Effects

Most self-concept studi es to date seem to be based on

the congruence noti on that consumers are moti vated to ap-

proach those products whi ch match thei r self-percepti ons,

but i t i s not clear on what theory or theori es thi s congruence

noti on i s based. Rogeri an humani sti c theory (Rogers 1951)

i s i mpli ci t i n the wri ti ngs of Landon, Grubb, and Ivan Ross.

Goffman's (1956) self-presentati on theory has been also

referenced i n a number of studi es (e.g., Schenk and Holman

1980; Holman 1981). However, most self-concept studi es

seem to be atheoreti cal (e.g., Bi rdwell 1968; Doli ch 1969;

Green et al. 1969; Hughes and Naert 1970).

The use of theory i s essenti al i n generati ng testable hy-

potheses and explai ni ng research fi ndi ngs. Consumer re-

searchers should be encouraged to generate thei r own self-

concept theori es i n consumpti on-related setti ngs. In addi -

ti on, many self-theori es i n soci al psychology can be effec-

ti vely used i n consumer research. For example, Festi nger's

(1954) soci al compari son theory can be used to explai n how

consumers evaluate themselves by compari ng what they

own and consume wi th others. Bandura's (1977) self-effi -

cacy theory can be employed to explai n the di fference be-

tween i deal congrui ty and i deal soci al congrui ty effects.

Self-concept theori es can also be used to gui de meth-

odology. Wi cklund and Frey's (1980) work on self-aware-

ness can gui de methodologi cal attempts to evoke respon-

dents' self-concepts i n the research setti ng. Bem (1967,

1972) cauti ons us agai nst self-report methods because the

i nferences made may li nk respondents' behavi or wi th self-

di sposi ti ons. Si mi larly, Deci 's (1975) cogni ti ve evaluati on

theory can be used to explai n attri buti onal mechani sms oc-

curri ng i n self-report or survey methodologi es. Jourard's

(1971) self-di sclosure theory explai ns the bi ased nature of

self-concept reports due to the i nti mate, personal, and

threateni ng nature of self-concept i nformati on.

Self-Image/Product-Image Congruence Models

Modeli ng self-i mage/product-i mage congrui ty i n relati on

to product preference and purchase i ntenti on has been, for

the most part, voi d of theory. Models most predi cti ve of

consumer choi ce or most popular i n the research li terature

have been "automati cally" adopted by self-concept re-

searchers.

The mathemati cal models of self-i mage/product-i mage

congrui ty have been exami ned by a number of i nvesti gators

i n relati on to consumer choi ce. Hughes and Naert (1970)

exami ned the followi ng atheoreti cal mathemati cal congru-

ence models i n relati on to purchase i ntenti on:

Si mple-di fference model n

>

(Si j

-

Pi j)

i = 1

Wei ghted si mple-di fference

n

model 2 Wi j (Si j -

P0j)

Si mple-di fference

(Si j

-

Pi j)

di vi si onal model E

i =1 Pi j

SELF-CONCEPT IN CONSUMER BEHA VIOR 295

Wei ghted

di vi si onal model

n

(A )

where

S = actual self-i mage (i ) of i ndi vi dual (j)

P11 = product i mage (i ) of i ndi vi dual (j)

Wo

= i mportance wei ght of i mage (i ) of i ndi vi dual (j)

The results showed that wei ghted si mple-di fference and

wei ghted di vi si onal models were equally predi cti ve of prod-

uct choi ce and more predi cti ve of product choi ce than the

unwei ghted si mple-di fference and si mple-di fference di vi -

si onal models.

Maheshwari (1974) compared the predi cti ve strength

of the Eucli dean-di stance model [E= (P11 - S11)2]112 ver-

sus the absolute-di fference model [1

I

l pi -si lS]

i n re-

lati on to product preference. The results showed no

si gni fi cant di fferences between these two congruence

models i n predi cti ng preference behavi or. Si rgy (1981a)

and Si rgy and Danes (1981) compared the predi cti ve

strength of a model emanati ng from self-i mage/product-i m-

age congrui ty theory wi th the strength of a number of tra-

di ti onally used congruence models.

Interacti ve

n

congruence model > (2PU1

-

Si j)

A bsolute-di fference

n

It

models Pi j - Si j f and E Pi j -Ii jt

Di fference-squared

n n

models E (PI1-S)2)2 and > (P11-

i = 1 i

a

1

Si mple-di fference

n n

models E (Pi - Si j) and E (Pi -I i j)

i =l_

i =

Eucli dean-di stance / 1 \1/2

models - (P1

-

Si j)2) and

n \1/2

E(Pi j-Ii )2

Si mple-di fference-

n

(Pi .-

S

i )

(P1

i 1i j)

di vi si onal models E andy

i = 1 Si j i =1 I.

where

I= i deal self-i maged (i ) of i ndi vi dual (j)

The results showed that the i nteracti ve congruence model

[n=l (2Pi j

-

Si j) I] was

generally equally

or sli ghtly

more

predi cti ve of product preference and purchase i ntenti on

when compared to the other models.

Some i nteresti ng recent developments i n communi cati ons

research have used di stance models i n multi di mensi onal

space as measures of self-concept/product-i mage congrui ty

(Woelfel and Danes 1980; Woelfel and Fi nk 1980). Con-

sumer researchers may benefi t from the appli cati on of MDS

i n modeli ng the congrui ty process.

Congruence modeli ng must be gui ded by theory. Fur-

thermore, any argument for the use of a speci fi c type of

cogni ti ve algebra i nvolved i n the congrui ty process should

be theoreti cally posi ti oned i n the context of the deci si on-

rule selecti on and deci si on-maki ng li teratures. Self-concept

researchers seem to i gnore the work of thei r colleagues who

are deci si on-maki ng researchers.

Moderator Vari ables

The use of moderator vari ables, such as personali ty di f-

ferences, soci al class, and product conspi cuousness to mod-

erate the relati onshi p between self-concept/product-i mage

congrui ty and consumer choi ce has also been relati vely voi d

of theory. For example, Ross (1971) and Doli ch (1969)

hypothesi zed that product conspi cuousness moderates the

relati onshi p between type of self-concept and preference

behavi or. Speci fi cally, the i deal self-concept was expected

to be more closely related to preference, for conspi cuous

products than actual self-concept would be, whereas the

actual self-concept was expected to be more closely related

to preference for i nconspi cuous products than i deal self-

concept would be. A lthough thi s hypothesi s sounds plau-

si ble, i t was not argued wi thi n the framework of a parti cular

theory.

A theoreti cal framework should be selected to hypoth-

esi ze the moderati ng effects of parti cular vari ables. For ex-

ample, i f we use self-i mage/product-i mage congrui ty the-

ory, i t has already been shown that type of consumer

deci si on (atti tude toward product versus atti tude towards

purchase) moderates the effects of self-i mage/product-

i mage congrui ty on purchase moti vati on (Si rgy 1979, 1980,

1982b). Wi thi n thi s theoreti cal framework, i t can be argued

that other personali ty moderator vari ables (e.g., locus-of-

control, self-moni tori ng, self-esteem, dogmati sm, soci al

approval, and achi evement moti vati on) can be used to pre-

di ct consumer choi ce. Si tuati onal moderator vari ables may

i nclude product conspi cuousness, i mage attai nabi li ty, pur-

chase conspi cuousness, product personali zabi li ty, product

vari abi li ty, and percei ved ri sk.

The Semanti c Di fferenti al

Turni ng to methodologi cal di ffi culti es, the use of the se-

manti c di fferenti al i s cri ti ci zed on many counts. No con-

sensual method i s used to select the i mage adjecti ves. Some

have used general adjecti ves extracted from personali ty i n-

ventori es (e.g., Bellenger et al. 1976; Maheshwari 1974).

Others have used attri butes most related to the products

bei ng tested (e.g., Bi rdwell 1968; Schewe and Di llon

1978). Only one study (Doli ch 1969) used terms that fi t

Osgood, Succi , and Tannenbaum's (1957) evaluati on, po-

tency, acti vi ty, stabi li ty, novelty, and recepti vi ty factors.

It i s recommended that the semanti c di fferenti al method-

ology only i nclude those i mages whi ch are most related to

the products bei ng tested.

296

THE JOURNA L OF CONSUMER RESEA RCH

Wi th the excepti on of Hughes and Naert's work (1970),

almost all the studi es that employed the semanti c di ffer-

enti al assumed equal wei ghti ng of the i mage attri butes.

Si nce these attri butes carry di fferent i mportance wei ghts for

each consumer (Maheshwari 1974), thi s assumpti on i s

clearly unwarranted. It i s therefore recommended that i m-

portance rati ngs for each attri bute be obtai ned through self-

report methods or other related techni ques.

Wi th a few excepti ons (Bellenger et al. 1976; Delozi er

1971; Delozi er and Ti llman 1972; Munson 1974; Stern,

Bush, and Hai r 1977), the majori ty of studi es employi ng

the semanti c di fferenti al fai led to provi de evi dence of re-

li abi li ty and vali di ty.

Most studi es usi ng the semanti c di fferenti al di d not test

for attri bute i nterrelati onshi ps such as dupli cati on, redun-

dancy, or overlap. Excepti ons i nclude Stern et al. (1977),

Bellenger et al. (1976), and Maheshwari (1974), who used

a factor analyti c procedure to reduce the full attri bute set.

Thi s factor analyti c techni que i s recommended for general

use wi th the semanti c di fferenti al methodology to ensure

attri bute i ndependence.

A lthough one may acknowledge that consumers may see

symboli c i mages i n products and that these i mages i nteract

wi th thei r self-i mages, i t can be argued that those i mages-

as tapped by the adjecti ve bi poles i n the semanti c di ffer-

enti al-may not be sali ent across i ndi vi duals and across

products. Only one or two out of a long li st of attri butes

may be sali ent i n a gi ven consumer's percepti on of the

product and of herself. Thus responses to the nonsali ent

attri butes may present addi ti onal methodologi cal confound-

i ng. To ensure hi gh i mage sali ency, only those i mages

whi ch are found to be hi ghly related to the product bei ng

tested should be i ncluded i n the semanti c di fferenti al. In

other words, general self-concept standardi zed scales are

not recommended.

Further, the semanti c di fferenti al methodology may be

suscepti ble to halo effects bi ases. Response to the i ni ti al

attri butes may bi as responses on followi ng attri butes. Other

methodologi es free from halo effects could be used to rep-

li cate fi ndi ngs from studi es usi ng the semanti c di fferenti al

methodology. These other methods may i nclude protocol

procedures, free eli ci tati on procedures, and so forth.

It can be argued that the use of bi polar adjecti ves assumes

that consumers can i denti fy wi th a hi gh degree of certai nty

whi ch pole of the adjecti ve descri bes them best. Breaki ng

from thi s tradi ti on, Grubb and Hupp (1968) and Si rgy

(1979, 1980) used uni polar adjecti ves i n a semanti c-di ffer-

enti al-type format for tappi ng the degree of appli cabi li ty or

certai nty of one's descri pti on of oneself along these adjec-

ti ves. The best possi ble soluti on may i nvolve both endors-

i ng an i tem between the adjecti val bi poles and also rati ng

the degree certai nty or uncertai nty felt regardi ng i tem en-

dorsement.

A lso, i t i s not clear how self-concept i nvesti gators usi ng

the semanti c di fferenti al methodology avoi d soci al desi ra-

bi li ty bi as (Edwards 1957; Crowne and Marlowe 1964). In

an attempt to compensate for soci al desi rabi li ty bi ases i n

the semanti c di fferenti al methodology, i nvesti gators are ad-

vi sed to (1) select neutral self-i mage attri butes, (2) use both

posi ti ve and negati ve self-i mage di mensi ons i f that i s not

feasi ble, and (3) i nform consumers that thei r responses wi ll

remai n anonymous (Pryor 1980).

Moreover, the self-i mage bi polar adjecti ves used i n the

semanti c di fferenti al methodology are very abstract. Bem

and A llen (1974) i ndi cated that psychologi sts measuri ng

self-concept assume that they can measure the relati ve pres-

ence of a parti cular, abstract self-i mage characteri sti c across

all persons. However, i t i s possi ble that certai n abstract

self-i mages may apply to some people but not to others.

For example, some consumers may be fri endly across a

vari ety of si tuati ons. For these consumers, fri endli ness i s

a relevant characteri sti c. Other consumers may be more or

less fri endly accordi ng to the si tuati on: for them, fri endli -

ness i s not a relevant characteri sti c. Bem and A llen (1974)

recommended at least two approaches to remedy thi s prob-

lem. One possi ble soluti on i s to make those self-i mage ad-

jecti ves si tuati on-speci fi c. Thi s can be accompli shed ei ther

by i nstructi ng consumers to respond to those self-i mage

characteri zati ons whi le thi nki ng of the product si tuati on

bei ng tested, or by phrasi ng those self-i mage adjecti ves i n

terms of sentence i tems reflecti ng a speci fi c consumpti on

si tuati on per self-i mage, and then usi ng Li kert-type scales

(i nstead of the semanti c di fferenti al scales) i n measuri ng

consumers' responses. A nother soluti on i nvolves aski ng

consumers to rate the vari ati on i n thei r self-i mage charac-

teri zati on across di fferent consumpti on-related si tuati ons.

Fi nally, i mage attri butes as represented i n the semanti c

di fferenti al methodology may create a self-di sclosure prob-

lem. One central proposi ti on i n Jourard's (1971) self-di s-

closure theory i s that generali zati ons about the self are

"i nti mate" topi cs that subjects hesi tate to di sclose. A num-

ber of possi ble soluti ons are presented that can lessen the

confoundi ng effects of the tendency to refrai n from self-

di sclosure. One possi ble soluti on i s to replace the general

personali ty characteri zati on i n the semanti c di fferenti al

methodology wi th "publi c self-i nformati on" on behavi ors.

A ccordi ng to the research of Runge and A rcher (1979) and

Feni gstei n, Schei er, and Buss (1975), publi c self-i nfor-

mati on on the form of speci fi c behavi ors i s not percei ved

to be self-reveali ng and therefore can lessen the self-di s-

closure problem.

A nother possi ble soluti on i s to mani pulate the i mmedi ate

envi ronment of the respondents to make i t more conduci ve

to self-di sclosure. Thi s can be accompli shed by (1) placi ng

the respondents i n a cozy room wi th pi ctures on the wall,

cushi oned furni ture, a rug, and soft li ghti ng (Chai ki n, Der-

lega, and Mi ller 1976); (2) usi ng an i ntervi ewer who may

be percei ved by the respondents as si mi lar to themselves

i n many respects (Chai ki n and Derlega 1974; Rohrberg and

Sousa-Poza 1976); and/or (3) hi ri ng physi cally attracti ve

i ntervi ewers to admi ni ster the questi onnai re (Brundage,

Derlega, and Cash 1977).

The Product-A nchored Q-Method

The product-anchored Q-method i s cri ti ci zed for several

shortcomi ngs. For example, some respondents may fi nd i t

di ffi cult to descri be themselves i n terms of products (French

SELF-CONCEPT IN CONSUMER BEHA VIOR 297

and Glaschner 1971). A lso, many of the products used do

not seem to have strong personali ty stereotypi c associ a-

ti ons-e.g., Greeno et al. (1973) used products such as

frozen orange jui ce, shoes, catsup, and potatoes; Belch

(1978) and Belch and Landon (1977) used products such

as coffee, cameras, and deodorant; and French and Glasch-

ner (1971) used products such as ovens, shoes, refri gera-

tors, and laundry detergent. It i s di ffi cult to concei ve how

these products may have strong personali ty stereotypi c as-

soci ati ons, or the extent to whi ch the self-concept may play

a role wi th these sorts of products i n determi ni ng consumer

choi ce. In addi ti on, the product-anchored Q-method fai ls

to di fferenti ate between product i mages and self i mages.

Thi s, i n turn, prevents attempts to model the self-concept/

product-i mage congrui ty process. A s a result of these i r-

remedi al problems, the author does not encourage the uti -

li zati on of the product-anchored Q-sort i n future consumer

self-concept i nvesti gati ons.

Standardi zed Personali ty Measures

To measure sex-role self-concept, Vi tz and Johnston

(1965) used the femi ni ni ty scales of the CPI and MMPI

personali ty i nventori es. Fry (1971) employed the CPI fem-

i ni ni ty scale, and Gentry et al. (1978) used those of the

CPI and PA Q personali ty i nventori es.

It i s not clear whether these measures tap self-percep-

ti ons-what Wyli e (1974) calls the "phenomenal self"-

or whether they tap hi dden, covert, nonconsci ous person-

ali ty trai ts and moti ves-i .e., the "nonphenomenal self."

Most consumer self-concept i nvesti gators seem to assume

that self-concept i s defi ned as "the totali ty of the i ndi vi d-

ual's thoughts and feeli ngs havi ng reference to hi mself as

an object" (Rosenberg 1979, p. 7). The i mpli ci t use of thi s

conceptual defi ni ti on of self-concept precludes the use of

these standardi zed, "cli ni cal" personali ty measures as i n-

di cators of sex-role self-concept.

Eli ci tati on of Self-A wareness

Wi cklund and Frey's (1980) self-awareness theory pos-

tulates that most people focus on the envi ronment because

the envi ronment typi cally provi des a hi gh degree of per-

ceptual sti mulati on, and that self-focused attenti on i s some-

ti mes aversi ve. Consumer product preference or purchase

i ntenti on are usually measured i n an envi ronment that does

not ensure acti vati on of the self-concept. Fai li ng to produce

a relati onshi p between the self-concept and product pref-

erence or purchase i ntenti on can therefore be attri buted to

the fact that product preference or purchase i ntenti on can

be determi ned from a vari ety of non-self factors. In order

to study self-concept i nfluences on these consumer behavi or

phenomena, a product/si tuati on that wi ll eli ci t the self-con-

cept must be used.

Pryor (1980) reported on three di fferent methods used to

create self-awareness i n soci al psychology studi es. One

method i s sensi ti zi ng a person to nuances i n hi s past be-

havi or (i .e., looki ng back). To i nduce such "retrospecti ve

self-awareness," soci al psychologi sts use vi deotape feed-

back, di ary methods, or i nstructi ons eli ci ti ng past self-re-

flecti ons. A second method i s to sensi ti ze a person to var-

i ati ons i n behavi ors as they occur (i .e., self-awareness

duri ng behavi or). Thi s i s usually accompli shed through the

use of mi rrors and/or i nstructi ons referri ng to the self. The

thi rd method sensi ti zes a person to personal characteri sti cs

duri ng the process of self-report (i .e., self-awareness duri ng

self-report). A gai n, thi s i s usually done through the use of

mi rrors and/or speci fi c wri tten or verbal i nstructi ons.

CONCLUSION

Thi s paper has attempted to cri ti cally revi ew self-concept

research. In so doi ng, vari ous conceptuali zati ons, theori es,

and models have been di scussed and measures used i n self-

concept studi es have been revi ewed. Research problems

concerni ng the theoreti cal and methodologi cal underpi n-

ni ngs of self-concept studi es have been i denti fi ed and rec-

ommended soluti ons have been proposed.

It i s di shearteni ng to conclude that, compared to con-

sumer atti tude research, consumer self-concept research i s

i n i ts i nfancy stage. Much work i s needed i n theoreti cal

generati on, model constructi on, and method development.

Interest i n consumer self-concept research wi ll i ncrease

when consumer researchers reali ze that the knowledge ex-

tracted from thi s type of research i s valuable for the appli ed

soci al sci ence researcher. Such researchers have recently

become more comfortable wi th employi ng atti tude models

i n appli ed soci al research. To date, however, the use of

atti tude models has been li mi ted to functi onal attri butes and

only rarely appli ed to symboli c or personali ty-related attri -

butes. A lthough i t would be foolhardy to advocate the use

of self-concept/product-i mage congrui ty models to the ex-

clusi on of the tradi ti onal multi attri bute atti tude models,

both types of models should be used to maxi mi ze consumer

behavi or predi cti on.

Knowledge generated from self-concept research can also

contri bute to consumer atti tude modeli ng and consumer

deci si on-maki ng research. For some unknown reason, self-

concept research has been treated as an offshoot topi c that

i s of i nterest to some and of li ttle uti li ty to others. Self-

concept research i s an i ntegral part of atti tude research and

should be consi dered as such. A tti tude theoreti ci ans and

researchers are challenged to develop atti tude theori es that

i ntegrate the soci al cogni ti ve dynami cs i nvolved wi th both

functi onal and symboli c attri butes i n explai ni ng, descri b-

i ng, and predi cti ng soci al behavi or.

[Recei ved May 1980. Revi sed February 1982.]

REFERENCES

A lli son, Nei l K., Li nda L. Golden, Gary M. Mullet, and Donna

Coogan (1980), "Sex-Typed Product Images: The Effects of

Sex, Sex-Role Self-Concept and Measurement Impli ca-

ti ons," i n A dvances i n Consumer Research, Vol. 7, ed. Jerry

Olson, A nn A rbor, MI: A ssoci ati on for Consumer Research,

604-609.

298

THE JOURNA L OF CONSUMER RESEA RCH

Bandura, A lbert (1977), "Self-Effi cacy: Toward a Uni fyi ng The-,

ory of Behavi oral Change," Psychologi cal Revi ew, 84,

191-215.

Belch, George E. (1978), "Beli ef Systems and the Di fferenti al

Role of the Self-Concept," i n A dvances i n Consumer Re-

search, Vol. 5, ed. H. Kei th Hunt, A nn A rbor, MI: A sso-

ci ati on for Consumer Research, 320-325.

and E. Lai rd Landon, Jr. (1977), "Di scri mi nant Vali di ty

of a Product-A nchored Self-Concept Measure," Journal of

Marketi ng Research, 14 (May), 252-256.

Bellenger, Danny N., Earle Stei nberg, and Wi lbur W. Stanton

(1976), "The Congruence of Store Image and Self Image,"

Journal of Retai li ng, 52 (Spri ng), 17-32.

Bem, Daryl J. (1965), "A n Experi mental A nalysi s of

Self-Persuasi on," Journal of Experi mental Soci al Psychol-

ogy, 1, 199-218.

(1967), "Self-Percepti on: A n A lternati ve Interpretati on of

Cogni ti ve Di ssonance Phenomena," Psychologi cal Revi ew,

74, 182-200.

(1972), "Self-Percepti on Theory," i n A dvances i n Exper-

i mental Soci al Psychology, Vol. 6, ed., Leon Berkowi tz,

New York: A cademi c Press.

and A ndrea A llen (1974), "On Predi cti ng Some of the Peo-

ple Some of the Ti me: The Search for Cross-si tuati onal Con-

si stenci es i n Behavi or," Psychologi cal Revi ew, 81 (Novem-

ber), 506-519.

Bem, Sarah L. (1974), "The Measurement of Psychologi cal A n-

drogyny," Journal of Consulti ng and Cli ni cal Psychology,

42, 155-162.

Bi rdwell, A l E. (1968), "A Study of Influence of Image Congru-

ence on Consumer Choi ce," Journal of Busi ness, 41 (Janu-

ary), 76-88.

Bri tt, Stewart H. (1960), The Spenders, New York: McGraw-Hi ll.

Brundage, Lani E., Valeri an J. Derlega, and Thomas F. Cash

(1977), "The Effects of Physi cal A ttracti veness and Need for

A pproval on Self-Di sclosure," Personali ty and Soci al Psy-

chology Bulleti n, 3 (Wi nter), 63-66.

Chai ki n, A lan L. and Valeri an J. Derlega (1974), "Vari ables

A ffecti ng the A ppropri ateness of Self-Di sclosure," Journal

of Consulti ng and Cli ni cal Psychology, 42 (A ugust),

588-593.

, Valeri an J. Derlega, and Sarah J. Mi ller (1976), "Effects

of Room Envi ronment on Self-Di sclosure i n a Counseli ng

A nalogue," Journal of Counseli ng Psychology, 23 (Septem-

ber), 479-481.

Crowne, W. J. and D. Marlowe (1946), The A pproval Moti ve:

Studi es i n Evaluati ve Dependence, New York: John Wi ley.

Deci , Edward L. (1975), Intri nsi c Moti vati on, New York:

Plenum, Seli gman.

Delozi er, Maynard W. (1971), "A Longi tudi al Study of the Re-

lati onshi p Between Self-Image and Brand Image," unpub-

li shed Ph.D. thesi s, Uni versi ty of North Caroli na at Chapel

Hi ll.

and Rolli e Ti llman (1972), "Self Image Concepts-Can

They Be Used to Desi gn Marketi ng Programs?" Southern

Journal of Busi ness 7(1), 9-15.

Doli ch, Ira J. (1969), "Congruence Relati onshi p Between Self-

Image and Product Brands," Journal of Marketi ng Research,

6 (February) 80-84.

Dornoff, R. J. and R. L. Tatham (1972), "Congruence Between

Personal Image and Store Image," Journal of the Market

Research Soci ety, 14, 45-52.

Edwards, A llen Loui s (1957), The Soci al Desi rabi li ty Vari able i n

Personali ty A ssessment and Research, New York: Dryden.

Epstei n, Seymour (1980), "The Self-Concept: A Revi ew and the

Proposal of an Integrated Theory of Personali ty," Person-

ali ty: Basi c Issues and Current Research, ed. Ervi n Staub,

Englewood Cli ffs, NJ: Prenti ce-Hall.

Evans, Frankli n (1968), "A utomobi les and Self Imagery: Com-

ment," Journal of Busi ness, 41 (October), 445-459.

Feni gstei n, A llan, Mi chael F. Schei er, and A rnold H. Buss

(1975), "Publi c and Pri vate Self-Consci ousness: A ssessment

and Theory," Journal of Consulti ng and Cli ni cal Psychol-

ogy, 43 (A ugust), 522-527.

Festi nger, Leon (1954), "A Theory of Soci al Compari son," Hu-

man Relati ons, 7, 117-140.

French, Warren A . and A lan B. Glaschner (1971), "Levels of

A ctuali zati on as Matched A gai nst Li fe Style Evaluati on of

Products," Proceedi ngs of the A meri can Marketi ng A ssoci -

ati on, 30, 358-362.

Fry, Joseph N. (1971), "Personali ty Vari ables and Ci garette

Brand Choi ce," Journal of Marketi ng Research, 8 (A ugust),

298-304.

Gardner, Burlei gh B. and Si dney J. Levy (1955), "The Product

and the Brand," Harvard Busi ness Revi ew, 33 (A pri l),

33-39.

Gentry, James W. and Mi ldred Doeri ng (1977), "Masculi ni ty-

Femi ni ni ty Related to Consumer Choi ce," Proceedi ngs of

the A meri can Marketi ng A ssoci ati on Educator's Conference,

10, 423-427.

, Mi ldred Doeri ng, and Terrence V. O'Bri en (1978),

"Masculi ni ty and Femi ni ni ty Factors i n Product Percepti on

and Self-Image," i n A dvances i n Consumer Research, Vol.

5, ed. H. Kei th Hunt, A nn A rbor, MI: A ssoci ati on for Con-

sumer Research, 326-332.

Goffman, Ervi ng (1956), The Presentati on of Self i n Everyday

Li fe, Edi nburgh: Uni versi ty of Edi nburgh Press.

Golden, Li nda L., Nei l A lli son, and Mona Clee (1979), "The

Role of Sex-Role Self-Concept i n Masculi ne and Femi ni ne

Product Percepti on," Proceedi ngs of the A ssoci ati on for

Consumer Research, 6, 595-605.

Green, Paul E., A run Maheshwari , and Vi thala R. Rao (1969),

"Self-Concept and Brand Preference: A n Empi ri cal A ppli -

cati on of Multi di mensi onal Scali ng," Journal of the Market

Research Soci ety, 11(4), 343-360.

Greeno, Dani el W., Montrose S. Sommers, and Jerome B. Kernan

(1973), "Personali ty and Impli ci t Behavi or Patterns," Jour-

nal of Marketi ng Research, 10 (February), 63-69.

Grubb, Edward L. and Harri son L. Grathwhohl (1967), "Con-

sumer Self-Concept, Symboli sm, and Market Behavi or: A