Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Ant 328 Final Paper

Transféré par

mmanyapuCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Ant 328 Final Paper

Transféré par

mmanyapuDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Manyapu 1

Mallika Manyapu

ANT 328

04/22/14

Title: Skirts in the Doctors Office: How Women Physicians Live in a Male-Dominated Field

Introduction: Topic and Why?

I was standing in small kitchen apartment in my uncomfortable black shoes,

uncomfortable skin-colored tights, and uncomfortable plain, black interview suit. My normally

unruly hair was neatly pulled back, my nails colorless, and my makeup absolutely minimal. This,

I was told, was how female medical school interviewees dress to impress. In my extensive

preparations for medical school interviews, I gathered all kinds of advice, from you must wear a

pant-suit to establish yourself, to you should wear a skirt in case you have some old misogynist

interviewer. While I am in no way a fashionista, I do enjoy the occasional splurge of color and

artistic self-representation through clothes and make up. What does this masculine uniform say

to young aspiring women physicians? Do we have to dress like men to be respected, or is there

no hope for the pervasive sexism and traditionalism?

While I was not so sheltered and naive to believe that women physicians live the same

kind of life as male physicians, I did begin to wonder how women physicians are treated today in

a still highly masculine field. If our appearance is placed under such scrutiny even before

reaching medical school, what does this suggest about current state of affairs of female

physicians? While men also have a uniform of sorts for interviews and within the medical field,

it seemed to me that the female uniform was even more conservative, strict, and masculine. As a

future physician, this topic was of particular interest to me. For months, people would ask me

why do you want to be a doctor? However, it was more surprising to hear the skepticism and

Manyapu 2

slight disapproval when other older females questioned my career choice. Over the course of my

medical school interview season, I discovered that while many physicians experience a certain

degree of frustration and tiredness with the job, women physicians sometimes experience this to

a higher degree. From casual conversations about lack of sleep, constant planning ahead, and a

perpetual to-do list, many of the women physicians I encountered were happy, but not ecstatic

about the growing number of women in the medical field. Thus, with these contextualization

cues, I set out to find out what female physicians deal with on a daily basis.

Background Research:

For years, women have been under-represented or under-appreciated in the field of

medicine largely because of the barriers in education and social standing. However, with recent

social changes over the past few decades, women have made a significant impact in the medical

field in treatments, healthcare delivery, research, and more (1, 4, 7). Despite these advancements,

however, many women and young females still feel some sting of stereotypes and social

expectations in certain environments, such as in interactions with unsuspecting patients who did

not expect a female physician, patriarchal driven research symposiums, white coat ceremonies

and in daily lunch conversations with colleagues (6).

According to the American Medical Womens Association (AMWA), the number of

women in the physician workforce has doubled over the past twenty years (2, 5). From 7 percent

in 1970 to near 25-30 percent in 2013, the growth rate for female physicians has been three times

that of the general physician population. This increase is evident even in the student population,

with most graduating classes from medical schools consisting of approximately half women (5).

However, there are still some apparent discrepancies between females and males within the

medical field, most evident by differences in compensation, number of hours worked, job status,

Manyapu 3

participation in academic research, and approach to patient care (1, 2, 5). For example, compared

to men, women faculty holding full professorships in medical schools is around 10 percent

compared to 30 percent of men holding full professorships (3, 4). This trend is persistent through

academic medicine, with fewer women publishing journal articles, fewer women advancing to

academic senior ranks, and female medical school faculty receiving lower compensation

compared to their male co-workers (4).

A recent survey conducted by the Physician Compensation Survey showed that male

physicians make an average 40 percent more than female physicians. There are several reasons

for why female physicians earn and achieve less than their male counterparts. One reason women

are not as involved in academic medicine as men is because of their specialty choices in mostly

primary care fields, including general practitioner, pediatrics, family medicine, psychiatry, and

internal medicine. In general, physicians in these fields focus less on academic medicine

involving research, interdisciplinary field collaboration, and treatment trials, and thus by default,

women are often excluded from such academic discussions. In addition, these physicians make

significant less income than highly specialized fields such as surgery, cardiology, and radiology,

placing physicians in these fields at a lower tier (3). Due to a variety of unproven hypotheses,

women constitute much of the primary care work force compared to men. Furthermore, female

physicians spend more time with their patients than male doctors do, contributing to a smaller

patient pool in comparison (5).

In addition to these issues, there are three key barriers preventing women from rising

through the ranks of the medical field. The first issue that women face is the traditional attitude

that prescribes women as responsible for housework, raising children, and providing care to the

family as a whole (3, 4, 6). Although this traditional gender role has morphed and changed much

Manyapu 4

over the years, there is still a pervasive, often assumed, idea that women know more about

raising family and running a house, and thus, are expected to fulfill those roles. This family role

can often make devoting time and energy to other avenues such as research or teaching much

more difficult. In contrast, male physicians are often encouraged to dedicate their lives to their

careers and thus move through the social and political spheres with much more ease (6).

The second factor contributing to womens differential success in the medical field is

unspoken and subtle hints of sexism (4, 6). While sexism has proven to impact training,

recruitment, promotion, management, and the routine work of female physicians, a 2010 survey

by the AMWA showed that women frequently experience sexist behavior with lack of

recognition, disrespect, and inappropriate sexual behavior and language. While these behaviors

have improved over the past few decades, the underlying ideas of sexism still persist and

negatively affect female physicians in their attempts to achieve success and status (4).

The third and most prominent issue that I myself have experienced as a pre-medical

student is the lack of female mentors for women. It is well known that advancement in any career

is heavily dependent on having an effective mentor and social capital force (4, 6). However,

because the number of working women has only slowly increased, there is a definite lack of

female mentors. Women in medicine have unique challenges from balancing home and work life

to interacting with certain patients that only someone with those experiences can adequately

advise. With this, the general lack of experience in the medical field that women sometimes face

compromise the issue further (6).

All of these issues affect women physicians ability to advance through the medical

sphere, manifested through unequal pay, inadequate access to academic resources, and a general

Manyapu 5

lack of experience in the medical system and structure. Besides these extrinsic factors, there is

also some evidence for differential treatment on the patient-doctor level.

Methods:

I originally wanted to focus my research and observations on the experience of minority,

female physicians. While partly for personal reasons, I was also curious about how minority,

female physicians lived with not just one differential aspect, but two: gender and ethnicity.

However, this topic proved difficult to pursue for a variety of reasons. For one, it was difficult

for me to find a female minority physician within the Emory area. Since I do not have a car for

easy transportation, I was limited to this particular area. While countless female minority

physicians do exist, I am sure, the few I approached were either uninterested or too busy to

indulge in my research. Whether the lack of interest stemmed from a busy schedule or hesitation

with the topic, I can only hypothesize. In addition to logistical issues, I also found it difficult to

differentiate between confounding variables of gender and ethnicity/race. Often times, I realized

that the differential treatment could be attributed to either gender or ethnicity/race, and analyzing

which variable came first was near impossible. I saw that real-world social and professional

interactions involve a variety of reactions that influence one another, including gender,

race/ethnicity, experience, language, accents, and location, to name just a few of what I

witnessed on frequent basis in one department of an outpatient clinic.

Consequently, with the limited amount of time I had, I chose to focus only on gender. I

shadowed one female, white American doctor, at Emorys Childrens Healthcare of Atlanta

Childrens Center and interviewed two American-born, second-year fellows. All three doctors

worked primarily in the Gastroenterology Department. I followed and observed Dr. Bethany

Manyapu 6

Smith*

1

in her clinic rotations on three separate occasions on Wednesday afternoons from

1:00PM-5:00PM, and interviewed the two fellows, Sameera Sana* and Talia Holmes*, Friday

afternoons after their own respective clinic rotations. Here, I will provide a brief background

about each person.

Dr. Smith is a middle-aged, born and raised Southern woman who has been practicing

medicine for over twenty years. She has been practicing as a part of Emory healthcare since

completing her residency at Emory and has co-authored two research publications. Dr. Smith has

two children, a 22-year-old son and an 18-year-old daughter. While other co-workers have

mentioned to me before that Dr. Smith has been married, I am not sure she is now. There is no

ring on her finger, and I did not receive explicit information suggesting she is still married.

Dr. Sana is an American-raised, born-in Pakistan-woman in her early thirties finishing up

her last year of a pediatric gastroenterology fellowship. She is married, but her husband lives in

Boston. Originally from the Northeast, Dr. Sana has been at Emory for the past two years.

Dr. Holmes is also an American-raised woman in her early thirties. While her parents

were originally from Russia, Dr. Holmes does not identify much with her Russian roots. She is

married and has a two-year-old son. Shes in her second year of medical fellowship in pediatric

gastroenterology and lives approximately half an hour away from work.

Observations:

As a pre-med student, I have had experience shadowing doctors, nurses, physician

assistants, and emergency medical technicians in various environments. However, this time I

approached my shadowing from an anthropological and sociological point of view. Instead of

paying attention to the medical jargon that was rapidly exchanged between medical

1

Starred names are pseudonyms.

Manyapu 7

professionals, I detailed how the information was being communicated and if there were

differences between male and female co-workers. Furthermore, instead of focusing on how

physicians interacted with patients, I focused on how patients treated physicians.

A typical clinic day began around 1:00 PM on a weekday afternoon, with research

coordinators, nurses, and physicians congregated in a relatively small office room sequestered

among patient rooms and open to the clinic. There were not enough chairs for every person in the

room, so I often pressed myself up against the wall and simply observed and followed Dr. Smith

without discussion. The names of all the patients who are being seen in a day are written on a

white board, and then divided among the two-three physicians, two-three nurses, and two-three

research coordinators present. At least one person from each category sees one patient. In this

particular clinic, all the nurses, one of the coordinators, and one other physician are female. This

leaves one additional male coordinator and two male physicians at any given time. Before

walking into a patients room, Dr. Smith would go over the paper chart and discuss the patient

out loud with either a nurse or another physician. Dr. Smith told me this is to refresh herself on

each patients particular case, as often she only sees a particular patient only two or three times a

year.

On one particular clinic day, a male doctor, Dr. K*, and Dr. Smith were discussing the

merits of continuing a certain treatment for a more difficult patient. The patient was technically

Dr. Smiths, but she had asked Dr. K for his input on this case previously. Their conversation

went as follows:

Dr. S: Tim* was highly resistant to (insert drug here). He does not like needles,

and this treatment requires bi-weekly shots.

Manyapu 8

Dr. K: Yes, but his disease has progressed too far for any other option to be even

plausible. If you see his x-rays and pathology, he will respond to only this drug.

Dr. S: True. I will just prescribe him this drug and hopefully, they wont cause me

too much trouble.

Dr. K: If you need help convincing, let me know.

Most conversations proceeded in some similar fashion. The conversation showed subtle

signs of hierarchy in that Dr. Ks opinions were valued more than Dr. Smiths. More so, whether

intentional or unintentional, Dr. K implied that Dr. Smith might not be able to persuade her

patient to take the appropriate drug. While on the surface, this may be because Dr. K is more

experienced, I believe the difference between Dr. K and Dr. Smith is further complicated by

gender. This conversation is just an excerpt of everyday conversations where female physicians

consulted a male physician and then ultimately agreed with the male physician. In contrast, if

there were no other physicians in the room, Dr. Smith would talk to the nurses about the case

history in a more authoritative tone. These conversations were often the nurses confirming or

denying what Dr. Smith said out loud. For example:

Dr. S: Cindy* was having severe stomach pains two weeks ago, when after ER

admittance, a scope showed bowel obstruction located approximately in the upper

colonic region.

Nurse: Yes, the scope also showed scar tissue in the lower tract regions.

Dr. S: In which, the lab reports confirmed that she had Ulcerative Colitis. What

drug did they start her on?

Nurse: Humira.

Manyapu 9

In between patients and in small openings of time, discussions would range from a recent

research article someone had read to what sport his/her child was attempting this time. In these

conversations, I noticed that there was a more academic tone to interactions between male

physicians while female physicians discussed the home life, as well. Dr. Smith, who has a

twenty-two year old son in college, was discussing his job prospects with another female

physician who also has a son. In contrast, her conversations with her male co-workers often

revolved around academic medicine. The conversations topics for female-female interactions,

and even for male-male interactions, showed a wider range than the male-female interactions.

This carried over in most aspects of medicine such as in research symposiums, lunch breaks, and

research meetings. For instance, in the few research symposiums and meetings I have attended

with Dr. K and Dr. Smith, I rarely saw a female lead the event. There were female physicians

present, and even some who participated in active discussions, but a male physician usually

began the conversation and ended the conversation. It almost seemed like the female physicians

were participant observers and not necessarily integral to the discussions.

When I asked Dr. Smith if she enjoys research, she simply stated, Usually. Its all very

tedious and time consuming, sometimes. Dr. Smith has co-authored two papers, in contrast to

Dr. K who has co-authored over ten journal articles. I remember on one occasion, Dr. K was

discussing with Dr. Smith a potential new research idea for one of his undergraduate students,

when Dr. Smith almost bitterly said, You know, you stole my patient for that last paper you

published. To which, Dr. K replied most apologetically, Oh really? You were supposed to be

an author on that paper as well On these occasions, Dr. Smith would dismiss the comment

and continue conversing about whatever previously discussed topic. While I personally believe

Dr. K did not intentionally leave Dr. Smith out of the paper, it is important to note that the only

Manyapu 10

other person he made sure to include in the paper was a male physician. Dr. Smith could have

argued for her name and reputation, but dismissed the matter as futile and commonplace. This

implies that such occurrences have happened before, where the female physician is forgotten in

academic medicine and related discussions. I see this as a veiled level of sexism.

In patient rooms, Dr. Smith encountered a variety of patients. Emorys patient pool is

quite diverse, with Atlanta metro families able to afford Emory healthcare coupled with rural

families afflicted with a rare disease that Emory specialists are best equipped to handle. Some

patients responded quite excitedly and warmly whenever Dr. Smith walked into the room.

Sometimes these patients families also shared the same enthusiasm. Dr. Smith would precede

her medical questions with casual conversation topics such as school, work, or a certain event

relevant to the patient. On one occasion, however, Dr. Smith was wary to enter the patient room.

She asked one of the male coordinators to talk with the patients family first, before she entered

the room. At first, I did not quite understand why, but upon entering the room later I could see

and feel the tension. The patient was a fourteen-year-old girl, present with her mother and father.

The family hailed from a small town in Georgia and, I was later told, owned a large farm estate.

The father did most of the talking, describing their daily activities, diet, etc. Neither mother nor

daughter gave much input unless specifically prompted by Dr. Smith. When Dr. Smith was

discussing treatment options, the father loudly contested most of the options as tedious,

expensive, or difficult. It was only with the male coordinator verbally supporting Dr. Smiths

suggested treatments and advice was Dr. Smith able to convince the patients father of the

appropriate treatment. After walking out of the room, Dr. Smith audibly sighed and absent-

mindedly shook her head in frustration. I later asked the male coordinator, who happens to be a

good friend and mentor of mine, what the background story for this particular patient was. He

Manyapu 11

shrugged and simply stated, He doesnt really listen to Dr. Smith in general. While it was

never explicitly stated, I inferred that the patients father prescribes to traditional gender roles

both at home and in public.

While I was not able to shadow the fellows on their clinic rounds, I did converse with

them about their experiences as female physicians and what they foresee for the future. Both Dr.

Sana and Dr. Holmes began with explicitly stating that they do not feel marginalized in any

shape, way, or form. In fact, Dr. Sana explained, The differences between female and male

physicians are more a product of old values. Sometimes I see the difference between an old

professor and a newer, younger colleague, but even that is really subtle. She further explained

this by citing a time when she was sharing the rough draft of her now-published paper to

colleagues and professors. She had sent it to two of her mentors, one female and one male. Her

male mentor critiqued and criticized much more than her female mentor did. She said, I

remember his email came back with a lot more red marks than her email. But I attribute this to

him being more experienced, and in the end, his harsh feedback was really helpful. Dr. Sana did

state, however, that she believes she is so successful right now because she has not had to come

home to children or a husband for the past two-three years. Although she finds it difficult to be in

a long-distance relationship, she stated that this gives her much more free time.

Dr. Holmes, who took a break between her residency and fellowship to give birth to her

now two-year old son, stated that she is often tired by Friday with taking care of her child,

working long hours, and being a fellow. She credits her mentors for helping her through the

process, and her co-workers for helping with the research and practicing side. She said, I wont

be a first author for a while probably, but it definitely does help to have someone do the work

with you. Dr. Holmes and one of her co-workers are splitting the tasks for research so that she

Manyapu 12

does not have to shoulder the entire burden of conducting the research and writing the paper. Dr.

Holmes further said that although she can see how being a woman physician is difficult with

balancing all the tasks at hand, working with more traditional male counterparts, she thinks that

her generation is changing the face of medicine all together. Everything is more collaborative

now than in previous decades. Theres really no rhyme or reason to discredit the female voice

anymore.

While both Dr. Holmes and Dr. Sana agreed that there is no way to completely eliminate

differences between female and male physicians, they each believe that in the coming years, the

traditional gender roles will be even more blurred.

Discussions:

The women I interacted with, Dr. Smith, Dr. Holmes, and Dr. Sana, always appeared

impeccably clean, professional, and put together albeit in varying ways. For instance, I rarely

saw Dr. Smith without makeup, a female flattering suit, or heels. On clinic days, I noticed little

hints of personality in her jewelry and color choice combinations. In contrast, Dr. Holmes and

Dr. Sana wore minimal makeup, and what I believe to be, more comfortable clothes that rarely

included heels or stiff pantsuits. In fact, co-workers have commented to me that Dr. Sana always

had the most comfortable and fashionable flats, while Dr. Holmes worked the indie and long

free-flowing skirts. These differences in appearance show the growing changes and trends that

female physicians face today.

Nevertheless, from these experiences, I have seen that the glass ceiling that was present

in past decades is still present today. From the unequal access to resources, significant

discrepancy in pay, and limited representation in academic areas, women physicians share issues

of pressurized adherence to typical gender roles, sexism, and lack of experienced mentors. From

Manyapu 13

an observer point of view, I witnessed a slightly, lopsided communication between male

physicians versus female physicians, where female physicians were more likely to not only

consult a male physician, but were also more likely to agree with the male physician. In fact,

there was a slight hierarchy of opinion, with the male physicians thoughts nearly always prized

more than that of female physicians. In contrast, woman-to-woman physician interactions were

often more discussion based, with back-and-forth conversation. However, I believe this male-

weighted communication is not simply because of an inherent patriarchal structure, although that

does play a role. From my observations, it is clear that because women physicians are relatively

new to the academic and medical sphere, as a whole, and women physicians are more

inexperienced when compared to male physicians. In medicine, experience and knowledge is

perhaps the most important factor for advancement, higher compensation, and a renowned

reputation, since someone elses life is quite literally in his/her hands. Thus, it makes logical

sense for an inexperienced person to refer to a more experienced person. Unfortunately, this

perpetuates the cycle in such a way that almost inevitably places the woman physician at a lower

position than a male physician. The patriarchal structures that has been in place within the

medical field for decades have naturally placed women at a disadvantage with educational and

advancement opportunities. Thus, this poses an additional challenge for women physicians who

wish to break out and establish themselves as reputable and independent physicians. For women

who hold a vital familial role at home, whether as a mother or household caretaker or more,

breaking through the glass ceiling can come at a cost. While I do believe it is possible for women

physicians to have it all, a successful career and a family life, the current hierarchal structure

and high responsibility physicians possess make achieving both aspects challenging.

Manyapu 14

However, after speaking with representatives of a younger population of physicians, I see

a slowly changing trend among the fellows. The fellows have much more access to a wide

variety of mentors, from male to female, and of all ages. This makes it easier to establish a base

and connection among the academic world. Further, the two fellows I spoke with seem to be

relatively happy with their work and home life. While often tired and sometimes stressed, the

fellows attribute this more to the job itself than to being a woman in the field. I predict that the

next generation of American-raised female physicians will have been exposed to the possibilities

of a work-home balance and will be generally less tolerant of differential treatment. This leads

me to believe that these same physicians will stretch the cycle and push up against the glass

ceiling with greater numbers and force. Through this, there may be more evident equality

manifested through salary and status. While it will be challenging to change the culture among

patient-doctor relationships and co-worker interactions, there are also signs of progress that will

perhaps turn the tide with the increasing number of female physicians. The changes in daily

wardrobe manifest this progress. Why experts still recommend medical school interviewees to

cater to some of the old ways, I am not sure, but the professional and female wardrobe seems to

be slowly evolving. More so, the current incoming medical school student population is

approximately half female and half male according to USA News. Even in this small

gastroenterology department, there are three female physicians, four male physicians, three

female fellows, and three male fellows total. In addition, with the possibility of male physicians

becoming more invested at home, as well, there is hope yet for American female physicians.

Conclusion:

There are obviously many limitations to my study due to the short period time of the

research and exposure to only one small clinic office, one physician, and two fellows. It is

Manyapu 15

impossible to assume that my observations apply to every female physician in every doctors

office or hospital. My focus was on American-raised female physicians, a select population that

has experiences vastly different from the rest of the world. Further research could include a more

widespread observation of other clinical offices and for a longer period of time. In addition, I

believe it is important to note that age does play a factor. Because of the many technological,

political, social, and cultural transformations that have occurred even in the past ten years, there

will be varying experiences in the doctors office or hospital regardless of gender or

ethnicity/race. Furthermore, interviewing male physicians, of various ages, on what they

perceive the female physician life to be like would add to a further study.

Manyapu 16

References

1. Levinson, Wendy, Susan W. Tolle, and Charles Lewis. "Women in Academic Medicine." New

England Journal of Medicine 321.22 (1989): 1511-517.

2. Mcmurray, Julia E., Mark Linzer, Thomas R. Konrad, Jeffrey Douglas, Richard Shugerman,

and Kathleen Nelson. "The Work Lives of Women Physicians. Results from the Physician Work

Life Study." Journal of General Internal Medicine 15.6 (2000): 372-80.

3. Morantz-Sanchez, Regina Markell. Sympathy & Science: Women Physicians in American

Medicine. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 2000.

4. Carr, Phyllis L. "Comparing the Status of Women and Men in Academic Medicine." Annals of

Internal Medicine 119.9 (1993): 908.

5. Rizvi, Rabab, Lindsay Raymer, Mark Kunik, and Joslyn Fisher. "Facets of Career Satisfaction

for Women Physicians in the United States: A Systematic Review." Women & Health 52.4

(2012): 403-21.

6. Rostami, Vida. "Women in Medicine." Women's Health Activist. N.p., 1 Nov. 2011. Web.

7. Tesch, B. J., H. M. Wood, A. L. Helwig, and A. B. Nattinger. "Promotion of Women

Physicians in Academic Medicine." Survey of Anesthesiology 39.5 (1995): 329.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Early Stages of Schizophrenia PDFDocument280 pagesThe Early Stages of Schizophrenia PDFJoão Vitor Moreira MaiaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5795)

- Neuropsychiatry and Behavioral NeurologyDocument302 pagesNeuropsychiatry and Behavioral NeurologyTomas Holguin70% (10)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Alveolarosteitis Andosteomyelitis Ofthejaws: Peter A. KrakowiakDocument13 pagesAlveolarosteitis Andosteomyelitis Ofthejaws: Peter A. KrakowiakPam FNPas encore d'évaluation

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Use of A Modified Matrix Band Technique To Restore Subgingival Root CariesDocument6 pagesUse of A Modified Matrix Band Technique To Restore Subgingival Root CariesDina NovaniaPas encore d'évaluation

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Coping With Addiction: 6 Dysfunctional Family RolesDocument4 pagesCoping With Addiction: 6 Dysfunctional Family RolesMy LanePas encore d'évaluation

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Loeffler SyndromeDocument19 pagesLoeffler SyndromeYama Sirly PutriPas encore d'évaluation

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- JWC Convatec Wound-Hygiene-28pp 14-Feb CA Web-LicDocument28 pagesJWC Convatec Wound-Hygiene-28pp 14-Feb CA Web-LicAjeng Kania100% (1)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

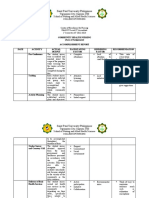

- Group 4 - Accomplishment ReportDocument5 pagesGroup 4 - Accomplishment ReportMa. Millen PagadorPas encore d'évaluation

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- 504 Morocco Fact SheetsDocument3 pages504 Morocco Fact Sheetsopiakelvin2017Pas encore d'évaluation

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- Disorders of The Upper Respiratory TractDocument3 pagesDisorders of The Upper Respiratory TractJannelle Dela CruzPas encore d'évaluation

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Riddle of DeathDocument2 pagesRiddle of DeathReka182Pas encore d'évaluation

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Handicapped ChildrenDocument36 pagesHandicapped ChildrenAbdur RehmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Johansen HutajuluDocument25 pagesJohansen HutajuluRSUD DoloksanggulPas encore d'évaluation

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- SDF Bendit - Young - WebDocument10 pagesSDF Bendit - Young - Webmadhu kakanurPas encore d'évaluation

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- 2019 Autogenous Soft Tissue Grafting For Periodontal and Peri-Implant Plastic Surgical ReconstructionDocument8 pages2019 Autogenous Soft Tissue Grafting For Periodontal and Peri-Implant Plastic Surgical Reconstructionayu calisthaPas encore d'évaluation

- Secondary Health 7 Q4 Module4Document9 pagesSecondary Health 7 Q4 Module4Rona RuizPas encore d'évaluation

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Bicipital TendonitisDocument2 pagesBicipital TendonitisJ Cheung100% (2)

- Diarrhea Nursing Care PlanDocument2 pagesDiarrhea Nursing Care PlanKrizha Angela NicolasPas encore d'évaluation

- Gerontik Setelah UtsDocument93 pagesGerontik Setelah UtsNidaa NabiilahPas encore d'évaluation

- Tubercular Meningitis in Children: Grisda Ledivia Lay, S.Ked 1508010038 Pembimbing: DR - Donny Argie, SP - BSDocument12 pagesTubercular Meningitis in Children: Grisda Ledivia Lay, S.Ked 1508010038 Pembimbing: DR - Donny Argie, SP - BSAulia PuspitaPas encore d'évaluation

- Herbal Its Project Biology.....Document52 pagesHerbal Its Project Biology.....MISHAPas encore d'évaluation

- Lansia Di Panti Jompo USADocument10 pagesLansia Di Panti Jompo USADWI INDAHPas encore d'évaluation

- DI Abdomen P 001 015 BeginingDocument15 pagesDI Abdomen P 001 015 Beginingtudoranluciana1Pas encore d'évaluation

- MCQ Immunology BasicDocument71 pagesMCQ Immunology BasicMatthew HallPas encore d'évaluation

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Aplikasi Sim Dalam Asuhan KeperawatanDocument14 pagesAplikasi Sim Dalam Asuhan KeperawatanCitra Puspita SariPas encore d'évaluation

- Temporomandibular Joint Disorders: Coverage RationaleDocument14 pagesTemporomandibular Joint Disorders: Coverage RationaleVitalii RabeiPas encore d'évaluation

- Gnadia Pasandidega1Document2 pagesGnadia Pasandidega1Craig DavisPas encore d'évaluation

- SMNR - 4... Wound HealingDocument62 pagesSMNR - 4... Wound HealingDrAmar GillPas encore d'évaluation

- SalmonellaDocument103 pagesSalmonellabrucella2308Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Mariam Burchuladze: Group 7 / Reflection EssayDocument1 pageMariam Burchuladze: Group 7 / Reflection EssayMariam BurchuladzePas encore d'évaluation

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)