Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

09 Chapter 1

Transféré par

Ali AhmedDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

09 Chapter 1

Transféré par

Ali AhmedDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

1.1 Introduction

Lndustrial sickness is an offshoot of rapid industrialisation and goes hand

in hand with industrial development. Growing competition and ever-changing

international economic environment often lead to high incidence of corporate

failure in developed market economies. The vast strides made in technological

development render old technologies obsolete, industrial recessions make some

unviable, international trade policies make some uncornpetitive and tardy progress

in some related sectors shrink markets for others. Marginal firms representing

weak and ill conceived, inefficient and mismanaged projects often disappear from

the industrial scene being unable to withstand the vicissitudes of changes and

shifts (Rai, 1993, 897).

In common parlance, industrial sickness means business failure. Like

human sickness industrial sickness is a painful reality affecting the society at

large. It aggravates the problem of unemployment, reduces the availability of

goods and services and enhances their cost . "Corporate Collapse has alwaj7s

brought about fearful mental pain to proprietors and entrepreneurs and to their

families. It al wqs meant that employees lose their jobs, shareholders lose their

savings and creditors lose cash and future business. The customer is deprived of

the p~*oduct. The local communi@ may be plunged into despair. Failure has

brought years and decades of legal wra~zgling in its wake. It ruins lives, destroys

the health of its victims, it pushes them to the edge of suicide and beyond. It has

always been so but each individual in our modern society is becoming so much

more dependent upon companies and other organisations thai the misely of failure

is now spread far and wide "(Argenti, 1976).

Industrial sickness is a cause of concern though it is bound to exist in

some form in every economic structure. For a healthy economy the loss by way of

non-productive assets and capital sunk in sick industrial units must necessarily

remain within sustainable limits. Developed economies, with their well-

established social security systems, are equipped to combat this in a better way.

But closure of industrial units in developing economies lead to serious

consequences since their limited investible resources and relatively limited

alternative employment opportunities cannot easily absorb resultant loss of jobs,

production and revenue (Mehta and Harode, 1998,711.

The sick industry syndrome in India was an isolated phenomenon in the

early sixties restricted to a few hundred units in one or two industries. In the

seventies, industrial sickness has emerged as a serious problem affecting the small,

medium and large units (Economic Survey 1987-88, P.40). A large number of

industrial units got closed down every year creating large-scale unemployment and

loss of investment ultimately slowing down the economic progress of the nation.

The statistics compiled by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) reveals that there were

2065 1 sick industrial units in India at the end of June 1978 with outstanding bank

credit of Rs. 1 1 87 crores locked up in them. By the end of March 2002 the number

Chapter I 3

of sick industrial units rose to 180597 units and the amount of outstanding bank

credit against them reached the level of Rs.26065 crores. The trend in the growing

incidence of industrial sickness and the outstanding bank credit locked up in sick

industrial units are given in Table 1.1

Table 1.1:- Industrial Sickness Trend in India

Institutional Funds

(Rs. in crores)

Period No. of Sick

Industrial Units

June 1978

December 1980

December 1985

-

March 1990

March 1995

March 1999

March 2000

March 200 1

March 2002

Source: Trend and Progress of

2065 1

24550

1 19606

. -- - -----

22 1094

271 206

309013

307399

252947

180597

Banking in India, EU3I Bombay

1187

1809

427 1

- - -

9353

13739

19464

23655

25777

26065

(Compiled from various issues).

The table shows that the number of sick industrial units in the country

have increased by 8.8 times and the amount of institutional credit by 22 times

between June 1978 and March 2002.

Taking cognizance of industrial sickness as a persisting problem affecting

the industrial development of the country, the Government of India and the

Reserve Bank of India initiated various remedial measures to put the unproductive

assets of sick industrial units to productive use. In the sixties, the Government

perceived industrial sickness as a threat to employment of labour and introduced

the policy of taking over of the units closed. It worked well since the number of

units closed was relatively low. The depressed and recessionary conditions

experienced by the country in the late sixties Iefi a large number of industrial units

sick. Rehabilitation was the only remedy available for the industrial units, which

have already become sick and are on the verge of collapse. This led to the

establishment of the industrial Reconstruction Corporation of India (IRCI) in 197 1

as the principal reconstruction agency in the country. But the number of industrial

units falling prey to industrial sickness continued unabated.

The relentless pressure of growing incidence of industrial sickness in the

country forced the Government to make drastic changes in its rehabilitation

polices. Various policy measures for the rehabilitation of sick industrial units like

the Soft Loan Scheme, Merger Policy -1977, Policy Guidelines on Sick Industrial

units-1 978, Policy Statement-1980, New Strategy- 198 1 etc., were initiated. But

many of the schemes were not so successfLl in curbing the increasing trend in

industrial sickness. The setting up of the Industrial Reconstruction Bank of India

(IRBI) in 1985 by reconstituting the erstwhile TRCI to function as the principal

credit and reconstruction agency for industrial rehabilitation in the country by

coordinating the similar work of other institutions also failed to bring about the

desired results.

This led to the enactment of the Sick Industrial Companies (Special

Provisions) Act, 1985 (popularly known as SICA, 1985). The Act aimed at the

timely detection of sick industrial companies and to expedite the revival of

potentially viable sick units. The Board for Industrial and Financial

Reconstruction (BIFR) was set up under the Act, with wide ranging powers in

respect of approval of rehabilitation schemes and their implementation. Even the

establishment of BIFR did not accelerate the process of rehabilitation of sick

industrial units. The present study aims to evaluate of the extent of success of the

BIFR in curbing industrial sickness by analysing the effectiveness of the

implementation of the rehabilitation schemes and the causes of their failure.

1.2 Statement of the Problem

The BIFR was set up in 1987 under SICA, 1985 to oversee the

rehabilitation of sick industrial units in the medium and large-scale sector. The

Act makes it mandatory for a sick industrial undertaking to report the matter to the

BIFR. The Board has wide-ranging powers for reconstruction, revival and

rehabilitation of sick industrial units. The revival measures include restructuring

of capital, sale of surplus assets, change in management, merger or amalgamation

with another healthy company, salellease of the unit and winding up of the

company where no revival is possible.

In rehabilitating a sick industrial undertaking the BIFR utilises the

services of an Operating Agency. The Financial InstitutiodBank having the

maximum stake in the sick unit is normally appointed as the Operating Agency. It

is the responsibility of the Operating Agency to study the problem of sickness in a

company, to identify the causes of sickness and to prepare a rehabilitation scheme

suggesting suitable revival proposals for the company.

Chapter I 6

The rehabilitation scheme spells out action to be taken by the

management, promoters, employees, financial institutions and Governments. The

management may be asked to restructure itself, the promoters may be asked to

provide additional capital, the employees may be asked to accept a wage freeze,

wage cut etc, for a period and the creditors or financial institutions may be asked

to grant moratorium on repayment, waive penal charges and interest and to extend

additional credit.

The BIFR became functional w.e.f I 5 May 1987. Since its inception up

to 3 1 December 2004, the BIFR had registered 5 147 references. They included

4940 private sector companies and 207 public sector companies. The total

accumulated losses of those companies stood at Rs.129144 crores and their

networth were Rs.65565 crores. There were 2473229 employees in those

companies.

Out of the 5147 registered companies, 2679 references were rejected,

recommending winding up in 1302 cases and dismissing 1377 references as non-

maintainable. Among the registered cases only 436 companies1 came out of the

'purview of the BLFR' after making their networth positive. This shows that the

success rate is only 8. 5 percent of the total number of references registered. The

low success rate shows that the performance of the B2FR in rehabilitating sick

industrial undertakings was not satisfactory. The details of the references

registered by the BiFR up to 3 1 December 2004 are given in Table 1.2, which is

self-explanatory.

' 4 1 5 private sector companies and 2 1 public sector units.

Chapter I

Table 1.2:- Details of Sick Companies Registered by the BIFR

(as on 3 I 11 2104)

I . .

Particulars Cases

Private Sector I

Central PSUs

No. of companies

No. of workers

Accumulated loss*

Networth*

Companies

No. of companies

NO. of workers

Accumulated loss*

Networth*

I State PSUS

/ NO. of companies

4940

1 443 853

101800

53414

\ No. of workers

1 Accumulated loss*

415

1 74751

3266

1 892

Total number of sick companies registered

Number of companies declared no longer sick

Number of employees employed in sick units

I -

1230

394593

10697

5484

1337

253375

26393

14393

Total accumulated loss*

65565

* Rs. in crores.

Chapter I 8

The low success rate with the BIFR may be due to the following reasons:

i. Late reporting of sickness to the BIFR

Timely identification of sickness in an industrial unit is essential for its

rehabilitation. As per the provisions of SICA, 1985 a company is considered as sick

only when its total networth2 is eroded by accumulated losses. This is a state of

imminent insolvency and it may be difficult for a sick unit to make a comeback by

implementing a revival scheme.

ii. Delay in sanctioning and implementing rehabilitation scheme

Timely implementation of a rehabilitation scheme is essential for the

revival of the sick unit. The BIFR being government machinery, the procedural

delays and its quasi-judicial nature and the consensus approach in finalising the

rehabilitation schemes make the BIFR process time consuming. It may affect the

' rehabilitation process adversely.

iii. Improper implementation of the rehabilitation scheme

The proper implementation of the rehabilitation scheme requires the

support of all participating agencies. Timely fulfillment of commitments by

various participating agencies is imperative. Often the rehabilitation schemes may

not be implemented in accordance with the original plan due to the non-

cooperation or delay in extending support by the participating agencies. This may

also reduce the chances of success of the rehabilitation schemes.

'~etworth means the sum toiaI uf the paid up capiiaI and free-reserves- Section

3( I )(ga). Free reserves mean all reserves credited out of the profits and share premium

account but do not include reserves created out of revaluation of assets, write back of

depreciation provisions and amalgamation.

iv. In berent weaknesses of the rehabilitation schemes

Proper remedial measures can be taken only if the real causes of sickness

in an industrial unit are identified. The implementation of rehabilitation schemes

without identifying the real causes of sickness in companies might have resulted in

their failure. The shortage of resources also might have affected the adoption of

proper remedial measures.

v. Lack of commitment on the part of management

Commitment on the part of the management is imperative for the

rehabilitation of a sick unit. If the BIFR reference of a sick unit is taken by the

management as an escape route to avail various relief and concessions and other

benefits, it may affect the chances of revival of the company.

vi. Incompetence of Operating Agencies

Operating Agencies should have specialised expertise in preparing the

rehabilitation schemes and monitoring their implementation. But in practice the

financial institutionbank with the maximum stake in the sick unit is normally

appointed as the Operating Agency without considering its technical and

managerial competence. This may reduce the success of the rehabilitation

schemes.

vii. Policy of the BIFR

The policy of the BIFR to take 'ameliorative' and 'remedial' measures 'in

public interest' in sick units with doubtful viability might have resulted in initiating

rehabilitation measures which in turn might have resulted in the failure of many

rehabilitation schemes.

In this context the identification of the reasons for the low success rate of the

BIFR is imperative in order to take appropriate action to fulfill the established

objectives of the BIFR in rehabilitating sick industrial units. The present study aims to

Chapter I 10

evaluate the extent of success of the BIFR in curbing industrial sickness by analysing

the effectiveness of the implementation of the rehabilitation schemes and the causes

for their failure.

1.3 Review of Literature

A number of empirical studies have been conducted to analyse the causes

of failure, to identify the symptoms of failure, to develop failure prediction models

and to evaluate various rehabilitation methods. Some of the studies related to the

rehabilitation of sick industrial units are summarised below.

Tiwari Committee (1984) in its report examined the legal and other

difficulties faced by banks and financial institutions in the rehabilitation of sick

industrial undertakings and suggested remedial measures including changes in

l a d . It recommended the need for a new enabling law and the creation of a Board

for industrial revival. A cause-wise analysis of industrial sickness was conducted

and it indicated the relief and concessions which should be provided by the

Government, sacrifices to be made by the management, labour, creditors,

shareholders and so on. The report revealed that 52 percent of the units became

sick due to deficiencies in management, 23 percent due to market recession and

environmental factors, 14 percent due to technical factors and faulty initial

planning, 9 percent due to infrastructure factors and 2 percent due to labour

trouble.

Biswasroy et a1 (1990) attempted to depict the institutional arrangements

available in India to combat the menace of industrial sickness. A detailed

evaluation of the operational performance of the Industrial Reconstruction

"zed on the recommendations of the Tiwari Committee, the Sick Industrial

Companies (Special Provisions) Act, 1985 was enacted and the Board for Industrial and

Financial Reconstruction (BIFR), a quasi-judicial body was established under the Act to

provide exclusive attention to tackle the problem of sickness in industrial units in the

medium and large sectors.

Chapter I 1 I

Corporation of India (IRCT) was made along with an empirical study selecting the

IRCI assisted units, using Altman's '2' score model to assess their revival

position.

Sriram (1990) analysed the practical problems in rehabilitating the sick

industrial units. Apart from the delay in identification of sickness and finalisation

of the rehabilitation packages, the involvement of a multiplicity of agencies made

the rehabilitation process difficult, The concurrence of promoters and of All India

Financial Institutions, respective State Financial Corporation, respective State

Industrial Development Corporation, State Electricity Board and Banks acted as a

stubborn bottleneck to finalisation, sanction and implementation of a rehabilitation

scheme.

The speech delivered by Shri. R Ganapati, the then Chairman, of the

BIFR on 9 July 1990 at Calcutta was regarded as the first off~cial deliberation

about the operating performance of the BZFR and the criticisms leveled against it.

He justified the high rate of the winding up of companies registered with BTFR

saying, ". .. the sorts of cases that come before the BIFR are almost mortuaty

cases ". He pointed out that though the preamble of SICA stated that timely

detection of sick companies as the important objective of the Act the definition of

a sick unit is too restrictive to take up remedial measures to curb sickness since

companies reported to the BIFR after the erosion of its total networth were often

mortuary cases. He suggested a change in the definition of a sick industrial

company so that the BlFR can tackle the problem of sickness in a unit at the

incipient stage itself.

Shinde (1991) made a well-accounted description of the growing

incidence of industrial sickness in Indian industries and the role of the BEFR in

rehabilitating them. He critically examined the operational performance of the

BIFR up to 3 1 October 1990 and suggested that the task that lies ahead was not the

Chapter I 12

identification of chronically sick units but the ensuring of a reasonably healthy

loan portfolio for the commercial banking system to take timely preventive action.

The Goswarni Committee (1993) was also critical of the working of the

BiFR since the process has been time consuming because of its quasi-judicial

nature and its working on the basis of consensus of all the parties having veto

power. The committee also criticised the Board's inclination towards rehabilitation

of sick units instead of going in for closure. The report emphasised the need to

make the BIFR a 'fast tract facilitator' rather than an arbitrator. The committee

was instrumental for the Sick Industrial Companies (Amendment) Act, 1993,

which incorporated radical changes in the definition of a 'Sick Industrial

Undertaking' to enable detection of sickness at the incipient stage so that the

implementation of a viable rehabilitation scheme becomes easy and effective.

Muralidharan ( 1 993) examined the adaptability of the different measures

of rehabilitation under SICA, 1985. He suggested that the amalgamation of a sick

unit with a healthy unit is the effective measure for rehabilitation where the

viability of the sick unit is doubtful and the rehabilitation of it is necessary in the

'public interest'.

Kaveri (1 994) analysed the challenges faced by the BTFR in rehabilitating

sick industrial units. He pointed out that the quasi-judicial nature of the BIFR

proceedings and the consensus approach in all stages of the preparation and

implementation of the rehabilitation schemes affected the timely implementation

of the revival schemes. He made certain structural changes that were required to

improve the efficiency in the working of the BIFR.

Singh and Kurnar (1994) pointed out that about 40 percent of companies

reported to BIFR were either denied registration aRer preliminary scrutiny of the

application or found non-maintainable aRer an enquiry by the RIFR under section

16 of SICA. They tried to find out a solution to this problem by analysing the

Chapter I 13

definition given under the Act and by interpreting the provisions of law in the light

of the BlFR and the AAIFR decisions.

Harish Parameswar (1997) put forward his view that a sick industrial unit

is not a total liability and that by a proper mix of inputs, finance and management

strategies meaningful revival packages can be worked out. In the monograph an

attempt is made to give a brief account of sick industry revival process with the

BFR and the stages through which a company passes before it is declared by the

BIFR as revived or failed. A critical evaluation of the role of Operating Agencies

in the revival process was also included. He suggested the need for the takeover

of weak units by healthy ones.

Pahwa and Puliani (2000) in 'Sick Industries and BIFR' judicially

interpreted all landmark judgments relating to rehabilitation of sick industrial

units. They included provisions of taw with detailed explanations in the light of

cases decided by the BIFR and the AAIFR. It can be used as a handbook for all

those who deal with sick industries.

However no serious attempt has been made to identify the causes of

failure of the rehabilitation schemes sanctioned by the BIFR. This study aims at

filling this vacuum.

1.4 Objectives of the Study

'nis study proposes to evaluate the effectiveness of the rehabilitation

schemes sanctioned by the BIFR. The study has the following objectives.

i. To evaluate the rate of success in rehabilitation of companies reported to the

RIFR.

ii. To evaluate the performance of the Operating Agencies in rehabilitating sick

industrial companies.

i i i . To examine whether the appointment of Operating Agencies improve the

success rate of rehabilitation schemes.

Chapter I 14

iv. To evaluate the performance of companies reported to the BIFR and for

which rehabilitation schemes were sanctioned and implemented.

v. To identify the inherent weakness, if any in the provisions of the legislation

relating to the working of the Board for Industrial and Financial

Reconstruction (BIFR) and the Appellate Authority for Industrial and

Financial Reconstruction (AAIFR).

vi. To study the impact of different variables in the rate of success of the

rehabilitation schemes.

vii. To suggest measures for improvement in the design of revival schemes and

their proper implement ation.

1.5 Hypotheses of the Study

To give a specific focus to the objectives related to the empirical aspects,

the following hypotheses have been framed.

i . The success rate of the companies reported to the BIFR with already

implemented rehabilitation schemes is higher than that of the companies with

newly formulated rehabilitation schemes.

ii. Diversification increases the success rate of rehabilitation schemes.

iii. The success rate of the rehabilitation schemes of different Operating Agencies

differs.

iv. 'The rate of success in rehabilitation schemes is influenced by various factors

such as increase in sales and scale of operation, reduction in cost of production,

diversification of activities, level of implementation of the rehabilitation

scheme, government policy, effects of globalisation, co-operation of the

Participating Agencies, financial restructuring, change in management and

defects in the rehabilitation schemes implemented.

v. The implementation of the rehabilitation schemes has made no significant

improvement in the performance of the companies.

Chapter I

1.6 Methodology

The methodology adopted for the study is described under the following

heads.

1.6.1 Nature of the Study

The study is d y t i c a l and descriptive in nature.

The effectiveness of the working of the BIFR in curbing industrial

sickness was evaluated by analysing the rate of success of the rehabilitation

schemes. The impact of different variables affecting the implementation of the

rehabilitation schemes was also analysed.

A descriptive evaluation of the various provisions of the legislation

relating to the working of the Board for Industrial and Financial Reconstruction

(BIFR) was made to examine whether there is any inherent weaknesses in the Act.

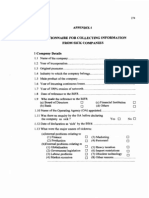

1.6.2 Data Collection

The study made use of both primary and secondary data.

Primary data were collected fimom the sick companies reported to the

BIFR. Data such as the time taken for reporting sickness, determining sickness and

sanctioning rehabilitation schemes, the different types of rehabilitation schemes

and the extent of their implementation were collected from the sick companies.

Pre-tested questionnaires were used for collecting primary data

(Appendix- 1). The census method was used for collecting primav data. As on 3 1

July 2000 there were 1855 sick companies for which Operating Agencies were

appointed. Questionnaires were sent to all sick companies but only 185 companies

responded positively providing necessary information.

Chapter 1 16

Data regarding 18 companies wound up after the failure of the

rehabilitation schemes and the performance of the Operating Agencies were

collected from the BIFR records.

Among the 203 companies selected for the study, data for only 32

companies were available in the Bombay Stock Exchange. Data regarding eight

companies were collected by personal visits and these 40 companies were selected

for analysing the tinancia1 perfomance after implementing the rehabilitation

schemes. Further, case studies of eight companies were also made. For case

studies, companies in Kerala state were selected for convenience in making the

study. Informal interviews and discussions with the Finance Managers and other

officers of the sick companies selected for the case studies were conducted to

collect primary data about the causes of sickness, viability of the company,

rehabilitation strategy and revival measures.

1.6.3 Analysis of Data

For analysis, data are presented in tables which facilitate calculations of

averages, percentages, ratios and co-efficient of variations. The performance of

sick industrial companies was analysed with help of trend ratios representing

profitability, solvency, current assets and overall performance after implementing

the rehabilitation schemes using Altman's 'Z' score4.

'The performance of the BIFR and the Operating Agencies were analysed

with the help of percentages, tables and diagrams.

Chi-square test has been used to verify the differences in the success rates

of different Operating Agencies, rehabilitation schemes of companies and that of

Operating Agencies and diversified and non-diversified cotnpanies. The variables

used for this analysis include time taken for reporting sickness, determining

-' See page no 1 5 1

sickness and sanctioning rehabilitation schemes. In order to examine the

relationship between these variables and the rate of success of rehabilitation

schemes, Karl Pearson's coefficient of correlation has been used.

The impact of different variables affecting the implementation of the

rehabilitation schemes was analysed with multiple regression using dummy

variables.

1.7 Scope and Limitation of the Study

The scope of the study is restricted to analysing the effectiveness of the

rehabilitation schemes sanctioned by the BIFR in the medium and large scale

companies. No attempt is made to go into matters such as the causes, symptoms

and the stages of sickness in industrial companies. Similarly the study does not

focus on the advisory measures adopted by the BIFR in the case of companies

reported with 'incipient sickness' under section 23 of the SICA, 1985. For the

study sick companies registered with the BIFR up to 3 1 July 2000 only were taken

into consideration. Further the study is subject to the following limitations:

a) for the analysis of performance after implementing the rehabilitation schemes

companies listed in the Bombay Stock Exchange only were considered. This

was adopted because of the availability of data about the existing as well as

companies wound up after the failure of'rehabilitation schemes,

b) companies which implemented the rehabilitation schemes sanctioned by the

BlFR are classified in to two categories. Those companies which came out of

the purview of the BIFR afier making their networth positive are classified

'declared no longer sick' and all other companies, 'not declared no longer sick'

and,

c) the sample does not include companies for which no Operating Agency has

been appointed.

Chapter I

1.8 Organisation of the Study

The study is presented in seven chapters. The first chapter gives an

introduction to the study covering the statement of the problem, review of

literature, objectives, methodology and scope and limitations of the study.

As a background to the study the various aspects of industrial sickness in

India and the role of different agencies in reviving sick industrial units are

presented in the second chapter.

The various measures for the rehabilitation of sick industrial units under

the Sick Industrial Companies (Special Provisions) Act, 1985 are included in the

third chapter together with the operational performance of the BIFR and the

Operating Agencies.

The fourth and the fifth chapters form the analysis part. They cover an

evaluation of the effectiveness of the rehabilitation schemes sanctioned by the

BIFR and the performance of companies reported to it.

Case studies of eight sick industrial companies in Kerala state are given in

the sixth chapter.

The last chapter concludes the study furnishing the summary, findings,

suggestions and the scope for further research.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Industrial SicknessDocument17 pagesIndustrial Sicknessmonirul abedinPas encore d'évaluation

- Reasons For Sickness in Ssi in IndiaDocument4 pagesReasons For Sickness in Ssi in IndiaGurmeet AthwalPas encore d'évaluation

- SicknessDocument11 pagesSicknessRuchi SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Hindalco Acquisition of NovelisDocument30 pagesHindalco Acquisition of NovelisUllasa Jha100% (2)

- KissanDocument3 pagesKissanVikas RastogiPas encore d'évaluation

- Fitbit Marketng Analysis & Strategy RecommendationsDocument22 pagesFitbit Marketng Analysis & Strategy RecommendationsYasir ArafatPas encore d'évaluation

- Non Fuel Retailing - Report - Arvind DwivediDocument87 pagesNon Fuel Retailing - Report - Arvind Dwivediarvind_dwivedi100% (4)

- Service Sector in Indian EconomyDocument5 pagesService Sector in Indian EconomyAvik SarkarPas encore d'évaluation

- Guidelines For Rehabilitation of Sick Small Scale Industrial UnitsDocument15 pagesGuidelines For Rehabilitation of Sick Small Scale Industrial UnitsIed UPPas encore d'évaluation

- Sip CotDocument8 pagesSip CotyogeshPas encore d'évaluation

- Pestel Analysis of Royal EnfieldDocument10 pagesPestel Analysis of Royal EnfieldMohanrajPas encore d'évaluation

- Cera Sanitary Ware LTDDocument15 pagesCera Sanitary Ware LTDapi-3696331100% (3)

- PESTLE Analysis of Speciality Chemical SectorDocument9 pagesPESTLE Analysis of Speciality Chemical SectorMegha Bavaskar100% (1)

- Project ReportDocument81 pagesProject Reportindianalions15100% (6)

- 1.1 Introduction About The StudyDocument37 pages1.1 Introduction About The StudyArun Kumar100% (1)

- Strategic Management Sessions 31 - 40Document7 pagesStrategic Management Sessions 31 - 40SHEETAL SINGHPas encore d'évaluation

- Cover PageDocument11 pagesCover PageTharshini KannanPas encore d'évaluation

- Small Industries Service InstitutesDocument5 pagesSmall Industries Service InstitutesShreyans Sipani100% (1)

- Surf ExcelDocument3 pagesSurf ExcelMuddasar AbbasiPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Study DiversificationDocument10 pagesCase Study DiversificationSebinKJosephPas encore d'évaluation

- Universal Print System LTD.: Vrushank Raut Rahul Satpute Milind Thakur Swapnil WaghDocument15 pagesUniversal Print System LTD.: Vrushank Raut Rahul Satpute Milind Thakur Swapnil WaghMilind ThakurPas encore d'évaluation

- Impact of Mergers On Stock PricesDocument30 pagesImpact of Mergers On Stock PricessetushardaPas encore d'évaluation

- Hand Gloves Project Report 2010Document9 pagesHand Gloves Project Report 2010karthik rPas encore d'évaluation

- Ashutosh Tiwari Final ReportDocument55 pagesAshutosh Tiwari Final Reportashutoshtiwariiilml2010100% (1)

- A Study On Inventory Management at Karnataka Soaps & Detergents LTD BangaloreDocument72 pagesA Study On Inventory Management at Karnataka Soaps & Detergents LTD BangaloreRitvik Lucky100% (1)

- Cera Sanitaryware - CRISIL - Aug 2014Document32 pagesCera Sanitaryware - CRISIL - Aug 2014vishmittPas encore d'évaluation

- Synthite IndustriesDocument29 pagesSynthite IndustriesPrashant yadavPas encore d'évaluation

- Hindustan Lever's Foray Into Network MarketingDocument33 pagesHindustan Lever's Foray Into Network MarketingSimran JoharPas encore d'évaluation

- Management of Financial Services and Institutions: Topic:-SIDBI (Small Industrial Development Bank of India)Document15 pagesManagement of Financial Services and Institutions: Topic:-SIDBI (Small Industrial Development Bank of India)seemagupta_11118018Pas encore d'évaluation

- Grohe India PVTDocument34 pagesGrohe India PVTRaju PatowaryPas encore d'évaluation

- Indian Edible Oil Market: Trends and Opportunities (2014-2019) - New Report by Daedal ResearchDocument13 pagesIndian Edible Oil Market: Trends and Opportunities (2014-2019) - New Report by Daedal ResearchDaedal ResearchPas encore d'évaluation

- Prestige Private LimitedDocument28 pagesPrestige Private Limitedlery.aryPas encore d'évaluation

- Bird's Eye - Group 1Document18 pagesBird's Eye - Group 1Saswata BanerjeePas encore d'évaluation

- Presentation On FMCG Sector in IndiaDocument13 pagesPresentation On FMCG Sector in IndiaAmitPas encore d'évaluation

- Business PlanDocument12 pagesBusiness PlanyounoussouPas encore d'évaluation

- To Study Product Awareness and Its Acceptance by The Customers For PureDocument65 pagesTo Study Product Awareness and Its Acceptance by The Customers For PureBharat LuthraPas encore d'évaluation

- Agri Implements IndustryDocument81 pagesAgri Implements IndustryNirav Joshi100% (1)

- Report On Motivation With Reference To J K TyreDocument89 pagesReport On Motivation With Reference To J K TyreChandan ArmorPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit 3 NotesDocument12 pagesUnit 3 NotesLakshay DhamijaPas encore d'évaluation

- Dream Company ITCDocument9 pagesDream Company ITCamandeep152Pas encore d'évaluation

- SM ReportDocument8 pagesSM ReportAbhijit DharPas encore d'évaluation

- Metlife Summer Mkt.Document60 pagesMetlife Summer Mkt.anilk5265Pas encore d'évaluation

- Financial Plan For MyMuesli (Only Market Research)Document14 pagesFinancial Plan For MyMuesli (Only Market Research)mevasaPas encore d'évaluation

- KSFC ProjectDocument26 pagesKSFC ProjectsrinPas encore d'évaluation

- Oxyrich FinalDocument15 pagesOxyrich FinalTanveer KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Research On The Effects COVID19 in Nigeria.Document4 pagesResearch On The Effects COVID19 in Nigeria.Marvellous WilhelmPas encore d'évaluation

- FinalDocument60 pagesFinalSANKET BANDYOPADHYAYPas encore d'évaluation

- MAGGI Case StudyDocument4 pagesMAGGI Case StudyGarima DhimanPas encore d'évaluation

- Batch 2015 - 2018Document63 pagesBatch 2015 - 2018Manisha NagpalPas encore d'évaluation

- Guidelines For TEV Consultant PDFDocument6 pagesGuidelines For TEV Consultant PDFSatyanarayana Moorthy PiratlaPas encore d'évaluation

- Team 1 - ROOTS INDUSTRIESDocument32 pagesTeam 1 - ROOTS INDUSTRIESChibi RajaPas encore d'évaluation

- Deccan PumpsDocument43 pagesDeccan PumpsManoj KumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Income Effects of Alternative Cost Accumulation SystemsDocument29 pagesIncome Effects of Alternative Cost Accumulation Systems潘伟杰Pas encore d'évaluation

- Swot Analysis of ItcDocument14 pagesSwot Analysis of Itcsamarth agarwalPas encore d'évaluation

- Discovery Channel - Discovering IndiaDocument11 pagesDiscovery Channel - Discovering IndiaYogita Ghag GaikwadPas encore d'évaluation

- The Indian Marketing EnvironmentDocument15 pagesThe Indian Marketing EnvironmentHeena Ferry AroraPas encore d'évaluation

- Video AdCampaign of AsianPaintsDocument8 pagesVideo AdCampaign of AsianPaintsSamarthPas encore d'évaluation

- SEBI Vs Nirvana Holdings (Heritage Foods)Document9 pagesSEBI Vs Nirvana Holdings (Heritage Foods)DealCurryPas encore d'évaluation

- Strategic Management 1Document28 pagesStrategic Management 1Magesh MuralidharanPas encore d'évaluation

- Industrial Sickness: Business EnvironmentDocument28 pagesIndustrial Sickness: Business EnvironmentAmar SarafPas encore d'évaluation

- SpeechesDocument2 pagesSpeechesAli AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- Cab o Sil M 5p MsdsDocument8 pagesCab o Sil M 5p MsdsAli AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- COA ClonazepamDocument1 pageCOA ClonazepamAli AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- 5 DR Farhat MoazamDocument9 pages5 DR Farhat MoazamAjit Govind SonnaPas encore d'évaluation

- Heparin Sodium USPDocument1 pageHeparin Sodium USPAli AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- Outlook 2007 ShortcutDocument4 pagesOutlook 2007 ShortcutAli AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- History of Cabot-SanmarDocument1 pageHistory of Cabot-SanmarAli AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- Heparin Sodium PH - Eur. DRAFTDocument1 pageHeparin Sodium PH - Eur. DRAFTAli AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- Outlook 2010 ShortcutDocument3 pagesOutlook 2010 ShortcutAli AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- List of Halal and HaramDocument14 pagesList of Halal and HaramMohd AliPas encore d'évaluation

- 16 BibliographyDocument7 pages16 BibliographyAli AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- List of Tables: Description No India Details Companies byDocument3 pagesList of Tables: Description No India Details Companies byAli AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- Questionnaire Information From Sick Companies: For CollectingDocument6 pagesQuestionnaire Information From Sick Companies: For CollectingAli AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- 12 Chapter 4Document33 pages12 Chapter 4Ali AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- Rehabilitation Under Sick Industrial COMPANIES (Special Provisions) ACT, 1985Document30 pagesRehabilitation Under Sick Industrial COMPANIES (Special Provisions) ACT, 1985Ali AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- Ramadan The Month of Fasting (Tamil) : For More Information, ContactDocument2 pagesRamadan The Month of Fasting (Tamil) : For More Information, ContactAli AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- Performance of Sick Companies Reported To The: and HasDocument39 pagesPerformance of Sick Companies Reported To The: and HasAli AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- Of Diagrams And: List ChartsDocument1 pageOf Diagrams And: List ChartsAli AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- List Abbreviations: AAI Appellate FinancialDocument1 pageList Abbreviations: AAI Appellate FinancialAli AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- Fffectivenes.s Of: The Rehabilitation SchemesDocument1 pageFffectivenes.s Of: The Rehabilitation SchemesAli AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- Acknowledgements: I Take Sincere in SuccessfulDocument2 pagesAcknowledgements: I Take Sincere in SuccessfulAli AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- 05 - Table of ContentsDocument6 pages05 - Table of ContentsAli AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- Shampooing & Cond. DrapingDocument22 pagesShampooing & Cond. DrapingAli Ahmed100% (3)

- AN Evaluation of The Effectiveness of The Rehabilitation Schemes of The BifrDocument1 pageAN Evaluation of The Effectiveness of The Rehabilitation Schemes of The BifrAli AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- Caste and Social Hierarchy Among Indian MuslimsDocument16 pagesCaste and Social Hierarchy Among Indian MuslimsAli Ahmed100% (1)

- Islamic ArtDocument8 pagesIslamic ArtAli AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- Scanning A Document & and Making A PDF in Adobe AcrobatDocument2 pagesScanning A Document & and Making A PDF in Adobe AcrobatAli AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- 225,226, Msds Isolan Gi 34 eDocument8 pages225,226, Msds Isolan Gi 34 eAli AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson Plan in Explicirt Teaching in Oral Lnguage and Grammar (Checked)Document3 pagesLesson Plan in Explicirt Teaching in Oral Lnguage and Grammar (Checked)Lovella GacaPas encore d'évaluation

- Sexuality Disorders Lecture 2ND Sem 2020Document24 pagesSexuality Disorders Lecture 2ND Sem 2020Moyty MoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Observation: Student: Liliia Dziuda Date: 17/03/21 Topic: Movie Review Focus: Writing SkillsDocument2 pagesObservation: Student: Liliia Dziuda Date: 17/03/21 Topic: Movie Review Focus: Writing SkillsLiliaPas encore d'évaluation

- Position Paper Guns Dont Kill People Final DraftDocument6 pagesPosition Paper Guns Dont Kill People Final Draftapi-273319954Pas encore d'évaluation

- Pugh MatrixDocument18 pagesPugh MatrixSulaiman Khan0% (1)

- Transportation Research Part F: Andreas Lieberoth, Niels Holm Jensen, Thomas BredahlDocument16 pagesTransportation Research Part F: Andreas Lieberoth, Niels Holm Jensen, Thomas BredahlSayani MandalPas encore d'évaluation

- DBI Setup Steps For Procurement IntelligenceDocument4 pagesDBI Setup Steps For Procurement IntelligenceAnubhav.MittalPas encore d'évaluation

- 1574 PDFDocument1 page1574 PDFAnonymous APW3d6gfd100% (1)

- Eco - Module 1 - Unit 3Document8 pagesEco - Module 1 - Unit 3Kartik PuranikPas encore d'évaluation

- Of Bones and Buddhas Contemplation of TH PDFDocument215 pagesOf Bones and Buddhas Contemplation of TH PDFCPas encore d'évaluation

- World Bank Case StudyDocument60 pagesWorld Bank Case StudyYash DhanukaPas encore d'évaluation

- Your ManDocument5 pagesYour ManPaulino JoaquimPas encore d'évaluation

- Paleontology 1Document6 pagesPaleontology 1Avinash UpadhyayPas encore d'évaluation

- 7A Detailed Lesson Plan in Health 7 I. Content Standard: Teacher's Activity Students' ActivityDocument10 pages7A Detailed Lesson Plan in Health 7 I. Content Standard: Teacher's Activity Students' ActivityLeizel C. LeonidoPas encore d'évaluation

- 001 Ipack My School BagDocument38 pages001 Ipack My School BagBrock JohnsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Use of ICT in School AdministartionDocument32 pagesUse of ICT in School AdministartionSyed Ali Haider100% (1)

- Impact of E-Banking in India: Presented By-Shouvik Maji PGDM - 75Document11 pagesImpact of E-Banking in India: Presented By-Shouvik Maji PGDM - 75Nilanjan GhoshPas encore d'évaluation

- Anthropology Chapter 2 ADocument17 pagesAnthropology Chapter 2 AHafiz SaadPas encore d'évaluation

- Uprooted Radical Part 2 - NisiOisiN - LightDocument307 pagesUprooted Radical Part 2 - NisiOisiN - LightWillPas encore d'évaluation

- Why The Sea Is SaltDocument3 pagesWhy The Sea Is SaltVictor CiobanPas encore d'évaluation

- John Galsworthy - Quality:A Narrative EssayDocument7 pagesJohn Galsworthy - Quality:A Narrative EssayVivek DwivediPas encore d'évaluation

- Asymetry Analysis of Breast Thermograma Using Automated SegmentationDocument8 pagesAsymetry Analysis of Breast Thermograma Using Automated Segmentationazazel17Pas encore d'évaluation

- (Dr. Mariam) NT40103 AssignmentDocument11 pages(Dr. Mariam) NT40103 AssignmentAhmad Syamil Muhamad ZinPas encore d'évaluation

- Business Enterprise Simulation Quarter 3 - Module 2 - Lesson 1: Analyzing The MarketDocument13 pagesBusiness Enterprise Simulation Quarter 3 - Module 2 - Lesson 1: Analyzing The MarketJtm GarciaPas encore d'évaluation

- Canine HyperlipidaemiaDocument11 pagesCanine Hyperlipidaemiaheidy acostaPas encore d'évaluation

- Course-Outline EL 102 GenderAndSocietyDocument4 pagesCourse-Outline EL 102 GenderAndSocietyDaneilo Dela Cruz Jr.Pas encore d'évaluation

- RARC Letter To Tan Seri Razali Ismail July 26-2013Document4 pagesRARC Letter To Tan Seri Razali Ismail July 26-2013Rohingya VisionPas encore d'évaluation

- 05 The Scriptures. New Testament. Hebrew-Greek-English Color Coded Interlinear: ActsDocument382 pages05 The Scriptures. New Testament. Hebrew-Greek-English Color Coded Interlinear: ActsMichaelPas encore d'évaluation

- Kepimpinan BerwawasanDocument18 pagesKepimpinan BerwawasanandrewanumPas encore d'évaluation

- Capital Structure: Meaning and Theories Presented by Namrata Deb 1 PGDBMDocument20 pagesCapital Structure: Meaning and Theories Presented by Namrata Deb 1 PGDBMDhiraj SharmaPas encore d'évaluation