Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Adolescent Social Support Network Student Academic Success As It Relates To Source and Type of Support Received

Transféré par

Mark Smith0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

88 vues138 pagesAdolescent social support network student academic success as it relates to source and type of support received in kids and adolescents

Titre original

Adolescent Social Support Network Student Academic Success as It Relates to Source and Type of Support Received

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentAdolescent social support network student academic success as it relates to source and type of support received in kids and adolescents

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

88 vues138 pagesAdolescent Social Support Network Student Academic Success As It Relates To Source and Type of Support Received

Transféré par

Mark SmithAdolescent social support network student academic success as it relates to source and type of support received in kids and adolescents

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 138

ADOLESCENT SOCIAL SUPPORT NETWORK:

STUDENT ACADEMIC SUCCESS AS IT RELATES TO

SOURCE AND TYPE OF SUPPORT RECEIVED

by

Maryanna Fezer

April 3, 2008

A dissertation submitted to the

Faculty of the Graduate School of

the State University of New York at Buffalo

in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the

degree of

Doctor of Philosophy

Department of Counseling, School and Educational Psychology

UMI Number: 3307683

3307683

2008

UMI Microform

Copyright

All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against

unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code.

ProQuest Information and Learning Company

300 North Zeeb Road

P.O. Box 1346

Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346

by ProQuest Information and Learning Company.

ii

Acknowledgements

There were many supportive individuals who assisted me throughout this process.

Their belief in me carried me through my course work and completion of my dissertation. Their

presence in my life was invaluable. I would like to extend my gratitude to those individuals.

First, I would like to thank God for giving me the ability to accomplish this degree and

for giving me my family. Heartfelt thanks to my parents, Steve and Rosaline Fezer, for instilling

in me my value of education, desire to learn, and drive to excel. With their love, support and

prayers, this arduous project was made possible. Thanks Mom and Dad. My brothers, Steve,

Andrew, Peter, thanks for keeping me grounded and reminding me not to forget about other

important things in life.

I would like to thank my advisor Dr.Tom Frantz for his patience, support, and advice.

For the past year, he gladly met with me and walked me through the process as I wrote each

paragraph, organized each chapter, and analyzed my statistics. You made this an enjoyable

process. I was very lucky to have you as my advisor.

Thank you to Dr. Jim Donnelly and Dr. Scott Meier for being on my committee. The

material you taught, in various classes throughout the years, assisted me to write this dissertation.

Your wisdom and humor were greatly appreciated.

Dr Susan Horrocks, thanks for being my student mentor, advising me on classes and

being my role model, as well as for the hours you and Mr. Horrocks spent on data entry. It

would have been a near impossible task without your assistance. Thanks to Dr. Sue Gerber for

all of the assistance with SPSS. Because of you, I learned to enjoy data analysis.

Finally, thank you to Superintendent Dr.George Batterson, Superintendent Dr. Barbara

Peters, Assistant Superintendent Mrs. Mary Beth Scullion, Assistant Superintendent Peter

iii

Michaelsen, Principal Mrs. Susan Frey, and to my Board of Education. By granting my

sabbatical, I was able to complete my necessary classes, collect my data, and begin my

dissertation. Thank you for valuing my education. Your encouragement and support will be

remembered and appreciated always.

iv

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements................................................................................................................ ii

List of Statistic Tables ...........................................................................................................vii

Abstract ..................................................................................................................................ix

Chapter 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................1

Definition of Social Support ..................................................................................................2

Models of Social Support.......................................................................................................3

Benefits of Social Support .....................................................................................................6

Social Support and Academics ..............................................................................................7

Measuring Social Support......................................................................................................8

Research Questions................................................................................................................9

Chapter II Review of the Literature....................................................................................11

Social Support A Multifaceted Construct ..........................................................................11

Purpose of Support Buffering or Main Effect.....................................................................11

Importance Verses Frequency of Social Support...................................................................16

Sources of Support .................................................................................................................17

Types of Support....................................................................................................................25

Gender and Developmental Differences................................................................................28

Adolescent Perceptions of Social Support .............................................................................30

Conclusion .............................................................................................................................31

Research Questions and Predictions ......................................................................................32

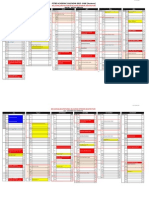

Summary Chart of Social Support Studies ............................................................................36

v

Chapter III Methodology ....................................................................................................38

Introduction............................................................................................................................38

Subjects..................................................................................................................................38

Variables ................................................................................................................................39

Instrumentation ......................................................................................................................40

Child and Adolescent Social Support Scale (CASSS)...........................................................41

Demographic Survey .....................................................................................44

Data Collection Procedure.........................................................................................45

Research Questions and Data Analysis .....................................................................46

Chapter IV Results Of Data Analysis .................................................................................49

Introduction............................................................................................................................49

Preliminary Analysis..............................................................................................................49

Analysis of Hypotheses..........................................................................................................52

Summary of the Results .........................................................................................................59

Chapter V Discussion .........................................................................................................62

Introduction............................................................................................................................62

Summary and Conclusions ....................................................................................................64

Importance Versus Frequency ...............................................................................................65

Age and Gender Differences..................................................................................................66

Types of Support....................................................................................................................68

Sources of Support .................................................................................................................71

Sources and Type Together ...................................................................................................74

Importance of Support ...........................................................................................................76

vi

Regression Predictions...........................................................................................................77

Limitations and Future Research ...................................................................82

References..............................................................................................................................85

Appendix A Statistic Tables ...............................................................................................96

Appendix B Graph and Histograms....................................................................................111

Appendix C Demographic Survey......................................................................................115

Appendix D Child and Adolescent Social Support Scale...................................................118

Appendix E - Internal Review Board Requirements .............................................................123

vii

List of Statistic Tables

1 Cronbachs Alpha Coefficients - Descriptive Statistics for Test Items ..................96

2 One Way ANOVA Impact of Grade Level (Importance and Frequency Scales .96

3 Independent t Tests Impact of Gender (Importance and Frequency Scales.........97

3a Descriptive Statistics CASSS Importance Scale................................................98

3b Descriptive Statistics CASSS Frequency Scale.................................................99

4 Descriptive Statistics Ranking Sources of Support .............................................100

5 Descriptive Statistics Ranking Types of Support ................................................100

6 Correlation - Frequency Scale and Importance Scale for Support Sources............101

7 Correlation -Frequency Scale and Importance Scale for Support Types................101

8 Friedman Analyses Significant Differences within Each Source........................102

9 Friedman - Rank Order of Social Support ..............................................................102

10 Paired t Tests Significant Differences for Females Rank of Support ................103

11 Paired t Tests Significant Differences for Males Rank of Support....................103

12 Descriptive Statistics - Types and Sources of Support .........................................104

13 Correlations Type and Sources of Support with Dependent Variables .............104

13a Summary of Correlations - Support Type with Dependent Variables ................105

13bSummary of Correlations - Support Source with Dependent Variables ..............105

14 Correlations - Types of Support from Sources of Support with Dependent Variables

for Males ..............................................................................................................106

15 Correlations - Types of Support from Sources of Support with Dependent Variables

for Females...........................................................................................................107

16 Summary of Correlations- (Table 14 and 15) Types of Support from Sources of

viii

Support with Dependent Variables for Males and Females.................................107

17 Regression Analysis Predictions for Social Support .........................................108

17aSummary for Regression Predictions...................................................................109

ix

Abstract

Social support is a multifaceted construct offering a multitude of benefits. The purpose

of this study is to assess the impact of social support on high school adolescents and their success

in school. The focus was on the source of support and on the type of support given. The sources

of social support were: teachers, parents, close friends, classmates, and the school. The types of

support were: emotional, informational, instrumental, and appraisal support. These types of

support from specific sources were believed to have an impact on important indicators of

academic success including; academic average, school attendance, school satisfaction, and

behavior. In addition, preliminary analyses were conducted to assess the variables of gender and

grade level to determine if they have an impact on perceived social support.

A total of 471 high school adolescents from grades 9 to 12 from a suburban school

district participated in this study. The subjects completed the Child and Adolescent Social

Support Scale (Malecki, Demaray, & Elliott, 2000) and a demographic questionnaire. The

students self reported the frequency and importance of social support received and their

indicators of success.

The findings indicated that females perceive more support than males from all of the

sources and of all types of support given. Though they perceive more support, it appeared they

were not receiving the type of support that contributed to their school success, instrumental and

appraisal support. Though males perceived less support overall, emotional support had the

greatest contribution to their school success and was the type most frequently given. Close

friend support was perceived most frequently however, supportive behaviors from parents had

the strongest correlations with the dependent variables. Finally, though teacher informational

x

support was perceived frequently, teacher emotional support contributed to student success in

school.

The conclusions of this study are intended to heighten awareness of the importance and

the impact of a social support network for the adolescent. Each source in the network has some

form of support that can be offered, impacting various aspects of the adolescents behavior and

success. Investigations of students perceptions of social support will assist educators and

parents identify crucial supportive behaviors that can be targeted for interventions.

1

Chapter 1

Introduction

Educational attainment is a necessity for todays youth. It is a significant predictor of

individual outcomes and general wellbeing (Dryfoos, 1990; Rumberger, 1995). The deleterious

consequences of dropping out of school include unemployment, criminal activity, delinquency

and poverty (Rumberger, 1995). Alarmingly, it is predicted that 10% to 30 % of United States

students will not complete their high school education on time, and in urban areas, more than

50% will drop out of school (Karam, 2006). In 1983, the National Commission of Excellence in

Education published A Nation At Risk indicating that students from other nations were out

performing US students in a number of educational measures. Education At a Glance indicated

that the US had fallen behind other nations in terms of high school diplomas earned, ranking

tenth among other industrialized nations (Study: US lags in high school diplomas, 2004).

Nearly a generation since A Nation at Risk was first published and the search for a solution to

this dilemma continues.

A students decision to drop out of school is a cumulative consequence of several factors;

lack of academic motivation, lack of achievement, and low parent and teacher support (Bean,

1985, Rumberger, 1995; Tidwell, 1988). Researchers, acknowledging the value of social

support, have begun to investigate its benefits as it relates to academic attainment. Scales &

Taccogna (2001) believe social support is a key asset contributing to academic success, and

Malecki & Demaray (2003) support the theory that educational attainment needs social

connections. Interpersonal relationships promote student motivation by enhancing a sense of

belonging and facilitating interest in academic success (Wentzel, 1994). To address the lack of

2

academic success of our youth, it is important to analyze the value of social support and its

impact on academic success.

Definitions of Social Support

Prior to understanding the academic benefits of social support for students, it is essential

to define the concept. Social support has been defined and measured in various ways. Some

researchers believed the concept to be too vague to be applied in scientific studies (Barrera,

1986). The lack of conceptual clarity was an impediment in the development of instruments

used to measure the construct (Procidano & Heller, 1983). Initially definitions were simple, but

grew to be more specific and encompassing. Caplan (1974) defined social support as a range of

significant interpersonal relationships that were considered important to an individuals

functioning. Barrera (1986) used three general categories, social embeddedness, perceived social

support, and enacted supports. Dunn, Putallaz, Sheppard and Lindstrom (1987) emphasized the

sources, as friends and family, within an individuals environment. Flaherty & Richmond (1989)

defined social support as one type of social exchange between network members.

Tardy (1985) believed that social support was a multifaceted construct and reduced its

lack of conceptual clarity by proposing a model of social support (Figure 1). He included five

salient aspects of the construct: direction, disposition, description/evaluation, content, and

network. Direction pertained to the path of social support; it is received from others, or provided

to others. Disposition referred to available or enacted social support. Available support was

quantity or quality of support that was accessible, and enacted support referred to actual

utilization of the social support resource. Description/evaluation represents two aspects.

Description refers to the qualitative characteristics of social support where as evaluation assesses

ones satisfaction with social support received. The fourth aspect was content, a description of

3

the nature or type of support. Last was network, critical people giving or receiving social

support.

Social Support Model

DISPOSITION

Provided

~

Available Enacted

~

Described Evaluated

DIRECTION Received

DESCRIPTION/

EVALUATION

NETWORK

Community

Professionals

_

CONTENT

Co-Workers

Figure 1. Tardy's model of aspects of social support.

4

Tardy incorporated the ideas of House (1981) into his model, for the aspect of content of

support (Nolton, 1994). Houses types of support were: emotional, instrumental, informational,

and appraisal support. Emotional support reflects caring, and refers to the provision of love,

empathy and trust. Instrumental support refers to the provision of helping behaviors as offering

of financial support, time or skills. Informational support refers to the provision of advice.

Appraisal support refers to evaluative feedback.

Tardys model/definition of social support, with the help of House, was adopted by many

researchers. The multifaceted definition had tremendous impact in assisting researchers to

measure the construct.

The definition of social support for the current study is based on the model of support

from Tardy. Social support is an individuals perception of general support or specific

supportive behaviors (available or enacted on) from people in their social network, which

enhances their functioning or may buffer them from some adverse outcomes (Malecki &

Demaray, 2002, p. 2).

Models of Social Support

How and when does social support assist an individual? There are two distinct

theoretical models of social support that both focus on the benefits provided; the stress buffering

and the main effect model. The stress buffering model based on the ideas of Cassel (1974) states

that support is beneficial in times of illness and stress, acting as a buffering mechanism. The

stressful life experience, psychological or physical, would be lessened under conditions of social

support, allowing for a better outcome (Cohen, Gottlieb, & Underwood, 2000). Under this

model the perception of the individual enables support to work in several ways; reducing the

negative affect surrounding the stressful event, reducing the perceived severity of the event, or

5

by increasing the problem solving ability of the individual. For example, some studies have

found significant negative correlations between social support and anxiety (Demaray & Malecki,

2002; White, Bruce Farrell & Kliewer, 1998), depression, (Cheng, 1997, 1998; Compas, Slavin,

Wagner & Vanatta, 1986; Demaray & Malecki, 2002) and drug use in adolescence ( Piko, 2000;

Frayenglass, Routh, Pantin, & Mason, 1997; Licitra-Kleckler & Waas, 1993).

The main effect model is based on the idea that support can be beneficial to all people at

any time, in the presence or absence of stress. As a main effect, support improves ones overall

psychological well being therefore reducing psychological problems (Cohen et al., 2000; Cohen

& Willis, 1985). According to Cohen et al., (2000) these benefits of social support are gained in

two ways; first, when a person is integrated in a social support network, and second, when an

individual perceives support availability. Being integrated in a support network can give one a

sense of belonging, stability, and security encouraging ones sense of self worth. This

integration can also reduce stress by providing helpful information and by being a source of

positive affect. Secondly, the perception that support is available if needed can be emotionally

and mentally satisfying. The perception of its availability can result in security and stability and

aid in a positive outcome when an individual is in distress.

The current study was guided by the main effect model. Social support from the network

of parents, teacher, close friend, classmate, and school can give a student a sense of security,

belonging, and a positive affect. It offers benefits to students at all times, in the presence or

absence of stress. This social support network, perceived or enacted, can impact the students

academic outcome.

6

Benefits of Social Support

Research on the concept of social support is not new. It has proven advantageous for a

multitude of psychological and physical problems for a variety of subjects. Varri, Barani,

Wallander, Roe and Frasier (1989) analyzed social support and its impact on self-esteem and

psychological adjustment for youth with diabetes. Both peer and family support were predictors

of externalizing and internalizing behaviors. Young children were best able to cope with their

illness when they received support from family, while adolescents coped best with support from

peers. Cauce, Felner and Primavera (1982) investigated the affect of support on self-concept

with high risk adolescents. They found that a higher perception of overall support was related to

better peer self-concept for adolescents in lower socioeconomic, inner city environments.

Coldwell, Antonucci, Jackson, Wolford, and Osofsky (1997) were interested in the relationship

between social support and depression. A negative correlation was found indicating that when

children and adolescents perceived higher levels of support, depression was low. If the subjects

did not perceive support, depression increased. Other internalizing behaviors, as anxiety,

somatization, interpersonal sensitivity, and depression were also found to be negatively

correlated with childrens overall satisfaction with social support, while Obsessive Compulsive

Disorder was unaffected (Compas, Slavin, Wagner, and Vanatta, 1986)

While some researchers were interested in social support as an independent variable,

others were equally interested in the variables that impacted social support. Researchers

analyzed the effects of race, age and gender on social support. White, Bruce, Farrell, and

Kliewer (1998) found a stronger negative relationship for African Americans than Whites when

looking at anxiety and family support. Demaray and Malecki (2002) looked at the difference

between, Native Americans, African Americans, Hispanics and Whites and their reaction to

7

social support. Native Americans reported less perceived social support from parents,

classmates, and friends than all others. African Americans perceived higher support than

Whites, who perceived higher support than Hispanics. In addition, younger children reported

more social support than older children from the sources of parents and teachers, and older girls

reported significantly more support from friends than males (Demaray et al., 2002).

Social Support and Academics

The concept of social support as it relates to academic success is far less researched, yet

has proven advantageous. Results have been documented in peer reviewed literature,

unpublished dissertations, and by not-for profit institutions.

The not- for profit Search Institute in Minneapolis, Minnesota has done extensive

research on asset building on nearly 100,000 students from 6th through 12th grade, from 213

American communities. In 1989, the Search Institute began studying the concept of assets in

youth, and in 1996, they developed a framework of forty developmental assets. Developmental

assets, or building blocks, are necessary for children to develop as healthy, responsible, caring

individuals (Keith, Huber, Griffin, & Villarruel, 2002: Scales, 1999; Hillaker, 2004). In general,

youth who possess many assets are more likely to report multiple thriving indicators including

school success, maintaining good health, resisting danger, impulse control, over coming

adversity, as well as avoid dangerous risk-taking behaviors (Search Institute, 2005).

The 40 assets are divided into two main categories, representing External and Internal

assets. Support, an External asset, is divided into: Family Support, Positive Family

Communication, Other Adult Relationships, Caring School Climate, and Parental Involvement in

Schooling. These Support assets have a major impact on school success. Strong, nurturing

8

relationships support youth, engage them in learning, and focus them on positive thinking and

behavior (Scales & Taccogna, 2001, p. 35).

Other researchers have analyzed specific variables of academic success and social

support. Forman (1988) believes that social support and educational placement is a predictor of

scholastic competence, conduct, athletic competition, physical appearance, general self worth

and self esteem. Malecki and Elliott (1999) also found a positive relationship between academic

performance, educational focus, social skills, self concept and social support. Wenz-Gross and

Siperstein, (1997) discovered that students with learning disabilities sought problem-solving

support less often than non-disabled students from family and peers. While Forman (1988)

found that if students with learning problems or disabilities sought support, they had higher

scores on self worth.

Measuring Social Support

To fully understand social support, and reap its benefits, a global view is not adequate,

specifics are important. Nolton (1994) measured various sources of adolescent social support,

parent, teacher close friend, and classmate, and how these sources impacted the success of

elementary and middle school students. Furthering this research, Malecki and Demaray (2003)

analyzed of the same sources of support, and included an additional dimension, type of support.

They investigated the affects of emotional, informational, appraisal, and instrumental support,

from the sources of parent, teacher close friend, classmate, and school, for middle school

children. By viewing these specifics of the construct, source and type, greater detail of the

impact of social support was discovered.

The current study will analyze the source and type of social support perceived by the high

school adolescent. The sources are parent, teacher, classmate, close friend, and school. The

9

types are emotional, informational, appraisal, and instrumental. Each source of support offers

varying forms of support, impacting various aspects of the adolescents behavior and success.

These relationships will be correlated with indicators of academic success; grade point average,

school satisfaction, behavior, attendance, and extracurricular participation.

An understanding of these variables of support, and how they relate to the indicators of

success, can assist parents, educators, and other professionals to identify supportive behaviors as

tools for intervention. Methods of teaching, parenting practices, clinical services and

preventative educational programs, can be improved from the knowledge gained through the

analysis of adolescent social support networks.

Research Questions

There are nine main research questions. The scores analyzed are from both frequency

and importance ratings, and from the type and source of support. The main questions are:

1.) What source of support (parent, teacher, classmate, close friend, or school) is

perceived most frequently?

2.) What source of support (parent, teacher, classmate, close friend, or school) is

perceived to be the most important?

3.) What type of support (emotional, informational, appraisal, or instrumental) is

perceived most frequently?

4.) What type of support (emotional, informational, appraisal, or instrumental) is

perceived to be the most important?

5.) What types of support (emotional, informational, appraisal, or instrumental) do the

students most frequently perceive from within each source of support (parent, teacher, class mate

10

close friend, and school)? This question will be addressed separately for males and females, and

for each of the grade levels.

6.) What types of support (emotional, informational, appraisal, or instrumental) do the

students consider most important from within each source of support (parent, teacher, class mate

close friend, and school)? This question will be addressed separately for males and females, and

for each of the grade levels.

7.) Are certain types of social support, (emotional, informational, appraisal, or

instrumental) related to students academic success, attendance, extra curricular participation,

behavior, and school satisfaction indicators? This question will be addressed separately for

males and females, and for each of the grade levels.

8.) Are certain sources of support (parent, teacher, close friend, classmate, or school)

related to students academic success, attendance, extra curricular participation, behavior, and

school satisfaction indicators? This question will be addressed separately for males and females,

and for each of the grade levels.

9.) Are certain types of social support, (emotional, informational, appraisal, or

instrumental) from specific sources (parent, teacher, close friend, classmate, or school) related to

students academic success, attendance, extra curricular participation, behavior, and school

satisfaction indicators? This question will be addressed separately for males and females, and

for each of the grade levels.

11

Chapter 2

Literature Review

Social Support - A Multifaceted Construct

Social support is a multi faceted construct, allowing for multiple forms of analysis.

Researchers have used numerous angles of examination. Social support has been examined as a

buffering agent, helping individuals through stressful situations, and as a resiliency agent

assisting individuals to excel. Components of social support have been investigated including

source (parents, teachers, friends, and classmates) and content (emotional, informational,

appraisal, and instrumental). The quantity and quality of the construct have been examined,

answering questions on frequency and importance of support. It has been analyzed as both a

criterion variable and a predictor variable. Considerations have been given to the effects of age,

gender, race, and group affiliation. The multifaceted nature of social support has contributed to

the opportunities for researchers to investigate the construct using a multitude of hypotheses.

Purpose of Support Buffering or Main Effect

A review of the literature, on social support for children, indicated that the traditional

focus of support was on the stress buffering model. Researchers analyzed factors that placed

children at risk for developing emotional, cognitive, and behavioral difficulties (Malecki and

Demaray, 2002). For example, Cowen, Pedro-Carroll, and Gillis (1990) researched the effects of

social support for children of divorce, revealing that it can lead to more positive outcomes.

Some looked at the benefits of social support as it is applied to children with learning disabilities

(Forman, 1988; Kloomok & Cosden, 1994; Rothman & Cosden, 1995; Wenz-Gross &

Siperstein, 1997). Others looked at the buffering effects of social support for high risk or

disadvantaged children (Cauce, Felner & Primavera, 1982) gifted children (Dunn, Putallaz,

12

Sheppard, & Lindstrom, 1987) and children victims of war (Llabre and Hadi, 1997).

Considerable evidence has encouraged others to examine the relationship between stressful

events or chronic life strain and mental or physical outcomes (Cohen & Willis, 1985).

Stress Buffering Studies of Social Support

Llabre and Hadi (1997) looked at the effect of social support on children who were

victims of the Gulf Crisis in Kuwait. Two years after the crisis, they examined the role of social

support in relation to trauma, psychological and physical distress. Participants were Kuwaiti

children who were exposed to various aspects of the war and varying degrees of trauma. The

results indicated social support did not mediate the relations between trauma and the outcome of

distress for boys, but it did for girls.

Foreman (1988) analyzed the buffering effects of social support and educational

placement on self esteem. She hypothesized that students with learning disabilities who

perceived access to support from parents, teachers, and peers would demonstrate higher levels of

self-concept compared to learning disabled students who perceived less access to social support.

She also predicted that students, placed in a special education program, would have better self-

concept than students who were not yet placed in a special education program.

The subjects in the Foreman study included 51 students, all diagnosed with learning

disabilities. There were 34 boys and 17 girls located in several elementary schools. The

instruments in the study included the Self-perception Profile for Learning Disabled Children

(SPPLD; Harter, 1985a), and the Social Support Scale for Children (SSSC; Harter, 1985b).

Results indicated that social support was a significant predictor of behavioral conduct,

athletic competence, scholastic competence, physical appearance, and general self-worth. Each

source of support, parents, teachers, and peers, had various effects on the out come variables.

13

High levels of classmate support had the greatest predictive impact on the students self-worth,

athletic competence, scholastic achievement, and physical appearance. Parental support had the

greatest predictive impact on students behavior. High levels of support from several sources

were predictive of high levels of self-esteem in various domains. Interestingly, social support

from teachers or close friends did not appear to have any statistically significant affect on the

students.

Cauce, Felner, and Primavera, (1982) examined social support as a buffering agent for

children at risk hypothesizing that support would help with adjustment for children from lower

socioeconomic and inner-city backgrounds. They examined dimensions of perceived support,

relationships between support and characteristics of the child, and indices of personal and

academic adjustment. Two hundred and fifty ninth and eleventh grade students were

administered the Social Support Rating Scale (SSRS; U. S. Department of Health, Education,

and Welfare, 1975). The scale measured the perceived helpfulness of teachers, clergy, friends,

and others.

Results were mixed. Support from the total network of sources was not significantly

related to achievement or self-concept, and support from friends was negatively correlated to

academic averages and greater absenteeism. Overall, family support was positively correlated

with scholastic self concept. For males, perceived support from teachers, counselors, and clergy

was associated with higher self-concept. Though results varied, in general, perceived social

support was positively related to the adjustment abilities of the at risk adolescents.

Main Effect Studies of Social Support

Recently, however, there has been increasing interest in studying the benefits of social

support under the main effect model, offering protective factors that promote resiliency in all

14

children (Brooks, 1994). The co-occurrence of support and life satisfaction in adolescents

(Suldo & Huebner, 2005), and peer support and adolescent happiness (Dew and Huebner, 1994)

have been analyzed. For the children in these studies, support assisted them to avoid problems,

find happiness, and obtain success.

Suldo and Huebener (2005) looked at difference in degrees of satisfaction and its

associations to adaptive functioning or maladaptive functioning in adolescents. Six hundred

ninety-eight students from three middle and two high schools were analyzed through the use of

seven self report instruments. Based on a life satisfaction report, adolescents were identified as

having extremely high, average, or low life satisfaction. Satisfaction was defined in terms of

interpersonal variables (social support from numerous sources), intrapersonal variables

(temperament and psychopathology) and cognitive variables (self-efficacy) (Suldo et al., 2005).

Results indicated that high life satisfaction co-occurred with high social support from

parents, close friends, classmates and teachers. Specifically, social support from classmates was

more closely related to high satisfaction than close friend support, and students who had high

teacher support also had high life satisfaction. Students who did not have high teacher support

had average and medium life satisfaction. The relationship between strong support from

classmate and teacher with high satisfaction suggests the school environment has a strong impact

on the life satisfaction of an adolescent. The schools made an important contribution to the well-

being of the adolescents.

Continuing with the main effect model of support, Demaray and Malecki, (2002a)

examined the levels of perceived social support and their impact on academic, social, and,

behavioral indicators considered important for the overall adjustment of children and adolescents

15

in school. They operationalized the construct into three levels of support; low, average, and,

high. The study consisted of students in grades 3 -12 from seven states (N = 1,711).

First, the researchers looked at the over all effects of perceived social support. Total

support had a high statistically significant negative relationship with both externalizing and

internalizing problem behaviors; a low but significant relationship with academic competence;

and moderately significant relationships with self-concept and adaptive skills.

Next, students categorized as low, average, or high recipients of support were compared.

The results indicated that overall, there was almost no difference between students with average

and high support regarding the academic, behavioral, and, social indicators. Both students with

high and average support had far fewer problematic indicators than students with low perceived

support. Students with high support were distinguished from students with average support by

their significantly higher scores on self-concept and student rated social skills.

Researchers suggested that there is a critical level of perceived support that is adequate

with regard to relationships with other indicators and there is not a significant difference beyond

this average or adequate level. High levels of support did not significantly improve scores on

indicator variables (Malecki et al., p 236, 2002).

In summary, social support has been thoroughly investigated as a buffering agent,

assisting children to overcome unfortunate difficulties, trials, and tribulations of life. Far less

research has focused on the benefits of social support for all individuals as they go about daily

activities accomplishing normal developmental tasks. Based on the overall benefits social

support has provided as a buffering agent, it has proven to be a valuable construct that should be

investigation further as an enhancer of performance, behavior, academics, and a catalyst for

success.

16

Importance Verses Frequency of Social Support

There is a difference between frequency of social support and importance of social

support. Frequency pertains to how often one reports obtaining social support and importance

refers to the value one places on social support. Prior studies focused on the frequency and paid

little attention to what students considered important. One may receive little support from a

classmate, which may be detrimental to one individual, or a group of individuals, but irrelevant

to another. Almost all research on social support has investigated individuals perception of the

frequency with which they receive socially supportive behaviors from individuals in their social

network. Virtually no data are available that indicate what socially supportive behaviors are

important to the students (Demaray and Malecki, p 109, 2003). This critical role of importance

has been overlooked, ignoring a valuable form of social validity (Wolf, 1978). Recent research

suggests that students of various groups rate the frequency and importance scores differently

(Demaray and Malecki, 2003).

In 2001, Demaray and Elliott targeted a specific group of students as they investigated

the importance of support. A total of 94 boys, 48 diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity

Disorder (ADHD) and 46 without the disorder, reported on the importance and frequency of

social support with the use of the Student Social Support Scale (Nolton, 1994). Results indicated

that the boys with ADHD received overall less support than the boys without the disorder. The

importance of social support, however, did not differ. Both groups of boys considered social

support as important.

In 2003, Demaray targeted middle school students grouped as bullies, victims,

victim/bullies, or as a control group. Subjects, 499 students 6th through 8th grade, were given

the Child and Adolescent Social Support Scale (Malecki, Demaray, and Elliott, 2000), and a

17

bully questionnaire based on the Bully Survey (Swearer, 2001). Results indicated that the

frequency of social support was highest for the control group. The Importance of social support

was rated highest for the victim or victim/bullies group of students.

In 1999, Malecki and Elliott analyzed importance of social support for 198 students from

7 through 12 grade. No particular group was targeted. They used the Social Support Scale for

Students (Nolten, 1994), measuring sources of support from parents, teachers, classmates and

close friends, and types of support, emotional, informational, appraisal, instructional.

Results indicated that frequency and importance scores correlated significantly but

moderately with each other. Inspection of the top10 ranked items indicated that close friend

support was the most important source (4 out of 10 items), and emotional support was the most

important type of support (6 out of 10 items). Though importance and frequency were

moderately correlated, the researchers considered them as two distinct values of the construct.

In summary, research typically ignored importance and focused on the frequency of

support. The above mentioned studies however, considered importance and frequency as

separate and valuable research constructs. Differences have been discovered regarding

importance verses frequency scores for social support based on ones gender, grade levels, race

and disability status (Demaray and Malecki, 2003).

Sources of Support

Traditionally, overall global support was analyzed for adults and children. More recently

various sources of support have been taken into consideration. Social development of

adolescents is best considered in the contexts in which it occurs; that is relating to peers, family,

school, work, and community (American Psychological Association, 2002, p. 64). When the

factor of source is not included in a study, a researcher runs the risk of misinterpreting results.

18

Overall support may not be significant but further analysis of the benefits provided by the

various sources may prove significant. Researchers have gained valuable data on the construct

of support by analyzing support from various sources.

Peer Support

A natural progression in adolescents is the shift of focus from the importance of the

family to the importance of the peer group. As an adolescent attempts to establish a sense of

independence, he or she spends less time with parents and family, and more time with his or her

friends. For the adolescent, peers are a valuable and influential factor in everyday life, and

support from peers has a variety of consequences. A peer group has a function and an

importance that no other means of support can provide.

Friends and classmates function as a reference point for adolescents as their identity

develops. Through this identification with peers they begin to develop moral judgments and

refine values (Bishop & Inderbitzen, 1995). Psychosocial adjustments have been linked to

positive peer relations during adolescents. Simultaneously, peer rejection and social isolation

has resulted in a variety of negative behaviors and poor psychosocial adjustment (American

Psychological Association, 2002).

Friends and classmates also function as a source of powerful reinforces of ones

popularity, status, prestige, and acceptance. Acceptance by peers has a short term affect as well

as a long range impact, lasting well into adulthood. Bagwell, Newcomb, & Bukowski, (1998)

found that an adult, who as a fifth grader, had at least one close friend, had better self-worth

compared to an adult who had been friendless as a child.

East, Hess, and Lerner (1987) hypothesized that students of different sociometric groups

varied in regard to perceived peer social support, behavioral, psychosocial, and academic

19

achievement. One hundred and one sixth graders, categorized as peer-rejected, peer-neglected,

popular, or controversial, were included in this study. Their results indicated that students

rejected by peers experienced significantly less social support from peers, than did popular

children. Teacher ratings indicated that peer rejected children received significantly lower

scholastic and classroom conduct scores than controversial and popular children. Peer rejected

students also experienced more adjustment problems than popular students and exhibited

significantly lower self worth than popular students. The researchers suggested that rejected

childrens awareness of their status encouraged their social withdrawal, resulting in diminished

social support.

Several studies, already discussed, further support the importance of the adolescent peer

group. They found positive effects of classmate support on self worth (Foreman, 1998) and life

satisfaction (Suldo et al., 2005). Some believed that classmate support was consistently stronger

in its predictive abilities than any other source of support (Nolton 1994). In one study,

adolescents rated close friend support as the most important source (Malecki et al.,1999), and in

another, classmate and close friend support was rated highly by students with disabilities

(Demaray et al.,2003). Not all peer support was positive. Cauce et al., (1982) found that support

from friends was linked to lower academic averages and greater absenteeism.

No study of adolescent support should ignore the value, impact, or enormous influence of

peer group members. Thus, this study takes into account the effects of social support from peers.

It assesses the emotional, instrumental, appraisal, and instrumental support offered by classmates

and close friends to high school peers.

20

Parental Support

The parents of an adolescent may often feel that their ability to impact their son or

daughter is limited. Their adolescent is more interested in listening to the advice given by his or

her peers. Increased peer contact among teens is a healthy developmental stage, not an

indication that parents are less important to them (OKoon, 1997). In fact, teens often strive,

sometimes covertly, to identify with a parent (American Psychological Association, 2002).

Parents need to be aware of the continued value they have, the role they play, and that the

support they offer is crucial for the continued healthy development of their adolescent.

Numerous studies have attributed parental support for assisting their adolescent through

this often difficult developmental period. Foreman (1988) believed parental support had the

greatest predictive impact on a students behavior. Nolton (1994) found parental support to be

negatively correlated with teachers ratings of problem behaviors.

Other studies have found academic achievement affected by parental support (Karam,

2006). Specifically, students who experience high support from parents had significantly higher

academic achievement. In addition, high life satisfaction and low absenteeism were also

associated with high parental support (Suldo et al., 2005). Positive parental impact has been

seen in overall wellbeing. Family closeness and attachment in general, was deemed the most

important factor linked to not smoking, less use of drugs and alcohol, fewer suicide attempts, and

postponement in sexual intercourse for adolescents (Resnick, Bearman & Blum, 1997).

Identity development is often generally considered to be established in early childhood.

Research has indicated, however, that identity formation continues into young adulthood

Hillaker, (2004). Research has also indicated that for the adolescent, healthy identity

development involves a restructuring of the parent-child relationship, not a severing of ties or

21

attachments to parents (Brook, Whiteman & Finch, 2000). In fact, the provision of parental

emotional support and parental knowledge of their adolescents daily activities have been linked

with stronger identity achievement (Sartor & Youniss, 2002).

Gambone, Klem and Connell (2002) performed a meta-analysis of longitudinal data

based on what matters most for todays youth. They confirmed the importance and the impact of

the supportive parent. The researchers stated:

The dimensions of support from parents that matter are; they offer help when needed,

discuss school and future plans with their child, check up on homework, know what the

child is doing with his/her time, know his/her friends, discipline consistently, and are

emotionally supportive. When children have these supports they get better grades, have

higher test scores, better attendance, participate in more extra curricula activities, and are

less likely to drop out are more likely to have adaptive coping mechanisms and less

likely to engage in risky behavior. (p 29-30)

No study of adolescent support should ignore the value, impact, or enormous influence of

parents. Thus, this study takes into account the effects of social support from parents. It

assesses the emotional, instrumental, appraisal and instrumental support offered by parents as

they raise their son or daughter from early adolescence into young adulthood.

Teacher Support

Children bring to school a multitude of problems and many of these negative experiences

have to do with problems in emotional and social behavior related to adult child interactions

(Erickson & Pianta, 1989). According to Pianta (1999) adult child relationships are crucial for

the healthy development of the child and underlie much of what a child is called to do in school.

Pianta believes that the strain, placed on these relationships, contributes to the rates of school

related difficulties faced by our children.

Extant research suggests that adult-child relationships can be some of the most frequently

reported protective factors in relation to associations with competence in school age children (Garmez

22

1993). An under researched source of such adults is teachers and other adults in school settings (Pinata et

al, 1999). These relationships may be a crucial key in helping a child succeed in school.

In 1989, Pianta and Nimetz did a pilot study examining the student-teacher relationships

of 72 kindergartners and 24 teachers. Three instruments were used gathering information from

the perspective of teachers and parents. The Student-Teacher Relationship Scale (STRS; Pianta,

1989) looked at the dimensions of security and insecurity in the teacher-child relationship.

Security was reflective of a secure, warm relation with the student, one with trust, where the

teacher felt in tune with the student, a perception that the student felt safe with the teacher and

the teacher could console the student. Insecurity was a rating given to children who were

perceived as a challenge to their efforts to teach, constantly sought reassurance and help, reacted

negatively to separation from the teacher and responded negatively to consolation. The Teacher-

Child Rating Scale (TCRS) assessed the teachers ratings of problem behaviors and

competencies of the students. It was a measure of childrens social, behavioral and academic

competencies and difficulties. The Preschool Behavior Rating Scale (PBRS) was a behavior

rating scale administered to the parent and assessed their childs competence, acting out, and

anxiety.

The results indicated a positive correlation between the teachers rating of security and

competency and between ratings of insecurity and acting out. A similar correlation existed

between the parents rating of their childs relationship score and childs competence and acting

out score. Reported by the teachers, children who had more secure relationships were rated to

have more competence: insecure children were rated as having more behavior problems and less

competence. Thus, the relationship between the teacher and student was believed to effect

competence and behavior.

23

Karam, (2006) identified critical variables in the students perceptions of good student-

teacher relationships. Her sample was composed of 575 middle school students in grades 6-8.

She hypothesized that students would express a preference for teachers who promote class

structure, autonomy, and emotional support. Students completed four self reports in order to

assess attendance, life satisfaction, perception of social support, and academic success.

Results indicated that academic achievement was related to teachers provision of

autonomy support, emphasis on mastery learning, and on high expectations. Self-reported life

satisfaction was related to teachers emotional support (teacher involvement), emphasizing

mastery over performance learning, and having high expectations, while attendance was related

to teachers emphasizing mastery learning. Teacher support was also linked to student

engagement and to academic achievement.

In summary, research has indicated that teacher relationships and support are crucial for

the success of the child. The teacher-student relationship had an impact on academic

competence and acting out behaviors for kindergarten children (Pianta). For middle school

children, teacher support was a positive link to academic success and life satisfaction (Karam,

2006). Unfortunately, far less research exists focusing on the importance of these relationships

to high school adolescents. Thus, in addition to peers and parents, no study of adolescent

support should ignore the impact of the teacher. This study takes assesses the emotional,

instrumental, appraisal, and instrumental support offered by teachers as the students progress

through their high school journey.

School Support

A school is more that the sum of its parts, it is an environment, a community in which an

adolescent spends approximately eight hours a day for five days a week, and often more if a

24

student is actively involved in sports, clubs, or other related school social activities. The school

community has a climate that is acknowledged by the Search Institute of Minnesota as having an

important role in creating developmental assets in youth. Creating a caring school community is

systemic, and involves fostering positive relationships between and among students, teachers,

parents, counselors, administrators, hall monitors, secretaries, custodians, cafeteria workers, and

security guards, all of whom have some form of interaction with the students (Scales, 1999).

According to Starkman, Scales and Roberts (1999), it is necessary to use relationships as a lens

through which to: view school policies, procedures, and practices; create permanent changes in

school organization; develop school support services and cocurricular programs; effect changes

in curriculum and instruction; foster community partnerships, all in an attempt to make the entire

school environment a caring community and more conducive to school engagement, academic

achievement, great teaching, and learning. Unfortunately, schools often adopt organizational

practices that can undermine an adolescents experience of membership in a supportive school

community (Osterman, 2000). Schools that focus on the inadequacy and pathology of the student

miss the opportunity to discover systemic deficiencies that maybe causing the original problem.

A persons functioning should be viewed as the product of reciprocal interplay between

person and environment (Bandura, 1978) thus, this study assessed how school, as a community,

offers support that impacts students ability to be successful. It assessed the emotional,

instrumental, appraisal, and instrumental support offered by the school, to the students as they

progress through their high school years.

In summary, sources of support are critical and their analysis is essential when

researching the construct of social support. Each source plays a different role, and possesses

different opportunities to impact students. This study examines social support from class mates,

25

close friends, parents, teachers, and the school. These sources are an integral part of the high

schools adolescents daily life, and impact their ability to be successful.

Types of Support

Traditionally social support was viewed and measured in global terms. In 1993,

Winemiller, Mitchell, Sutliff, and Cline performed a meta-analysis, categorizing studies of adult

social support conducted between 1980 and 1987. Their findings indicated that 68.3% of the

studies focused on global support, 37.8% focused on esteem support 28.2 % focused on

instrumental support, 20.2 % assessed informational support. More recently, Malecki and

Demaray (2003), believed that studies have demonstrated that support played an important role

impacting outcomes however, these conclusions often did not consider the type of support

investigated. Despite the existence of a conceptual framework necessary to investigate types of

support, this aspect has been overlooked. Theoretical examinations of social support indicate

however, that content/type of support needs to be incorporated when examining this construct

(Winemiller et al., 1993).

Richmond, Rosenfeld, and Bowen, (1998) looked at types of support and their impact on

several dependent variables for middle school children. Their findings indicated that different

types of support affect different aspects of ones life. For example, listening support from peers

correlated with student grades, technical challenge support from parents correlated with

attendance; emotional support, emotional challenge support, and reality confirmation support,

from parents, peers, and teachers was associated with school satisfaction.

Cheng (1998) looked at Chinese adolescents and types of support. He found gender

differences in the relationship between support types and outcomes. Depression for adolescent

males was associated with a lack of instrumental support; depression for females was associated

26

with a lack of socioemotional support. Thus, Cheng found that there may be significant

differences in the interaction of gender, type of support, and outcome.

This present study is an extension of the research from Malecki and Demaray, (2003) that

focused on the type of social support children need. The researchers had two main hypotheses;

1.) that certain types of support (emotional, informational, appraisal, and instructional) were

most often perceived from certain sources of support (parent, teacher, classmate, and close

friend) and 2.) that certain types of support (emotional, informational, appraisal, and

instructional), from specific sources, were more frequently related to students social, behavioral,

and academic indicators.

The subjects of the Malecki et al., (2003) study were middle school age children.

Included were 263 students from grades 5 through 8, and 49 teachers. All were given a self-

report instrument. Teachers completed the Social Skills Rating System-Teacher version (SSRS-

T, Gresham & Elliott, 1990), focusing on the social skills, problem behaviors, and academic

competence of their students. Students were given the Child and Adolescent Social Support

Scale (Malecki et al., 2000) focusing on the source and type of perceived social support.

Frequency scores were indicators of the number of times a student perceived specific

types of support from within a specific source. Emotional and informational supports were

reported most frequently from parents; informational support was reported most frequently from

teachers and the school; emotional and instrumental supports were reported most frequently from

classmates and close friends. Not surprisingly, teacher informational support was perceived

significantly higher than teacher emotional, appraisal, and instrumental support.

Importance scores were an indicator of the value students placed on the type and source

of support. The importance scores had a similar pattern to the frequency scores. The most

27

important type of supports from within a specific source were; emotional support from parents;

informational support from the teacher and the school; emotional support from classmates and

close friends. Again, teacher informational support was rated significantly more important than

emotional, appraisal and instrumental support.

In looking at the sources and types of support as predictors of social skills, behavioral,

and academic indicators, no type of parental support was a significant predictor, however, all

types of parental support collectively were related to personal adjustment. Researchers suggest

that parental support is related to students well-being. Unexpectedly, no type of classmate or

close friend support was significantly correlated with any of the outcome variables. Past

research had associated peer support types with student successes (Demaray and Malecki, 2002a,

2002b). Surprisingly, teacher emotional support was the only significant predictor of social skills

and academic competence.

In summary, the Malecki et al., (2003) study of social support type and source proved

valuable, in terms of the detailed results. Most interesting were the data on support type as an

academic predictor. Though teacher informational support was perceived significantly higher

and significantly more important than teacher emotional support, it was teachers emotional

support that was the sole predictor of students academic success and social skills. Though

parental and peer emotional support were perceived as frequent, and important, they were not

predictors on any outcome variables. Teachers need to be aware that there should be a balance

between informational and emotional support provided by them to ensure student success and

well-being.

28

Gender and Developmental Differences in Social Support

It is crucial to consider the factor of gender when examining social support (Rhodes,

1998). Although both males and females value their friendships, there are gender differences in

the quality of their relationships (Buhrmester, 1996; Rhodes, 1998). In general, young males are

more involved with action oriented pursuits with friends, and girls are more interested in talking

(Smith, 1997). The age of a child also affects the structure of ones social support network.

Middle school adolescents tend to spend more time in groups where as the high school

adolescent often replace peer groups with one-on-one friendships and romantic relationships

(Micucci, 1998). It is difficult to separate the factors of gender and age when examining social

support. They have an interaction effect that needs to be assessed (Demaray & Malecki, 2003),

in addition to separate effects of their own.

Nolton (1994) developed the Student Social Support Scale in order to consider both

sources and content of support, and to investigate details of the construct of social support. In

the first phase, teachers, parents and students helped to develop and refine test items (N = 25). In

the second phase he verified the psychometric properties of the scale and validation of the

construct (N = 298 third through eighth grade students).

Results indicated that the perception of social support varied depending on the students

grade and gender. As predicted, females perceived higher levels of support than males within all

grade levels, from all sources of support. Both males and females reported a decrease of parent

support as the grade level increased, while the perception of classmate and close friend support

remained constant across all grade levels.

Malecki and Demaray (2002) examined the differences in students perception of social

support based on their age, gender, and race. They combined data from several studies, which

29

assessed support through the use of the Child and Adolescent Social Support Scale. In addition

280 sixth through eighth grade students were recruited school wide and added to the study. The

total sample was 1110 students from grades 3 to 12.

Results were as predicted; age, gender and race all had a significant impact on perceived

support. The pattern of social support in relation to age indicated a developmental trend.

Support scores were high with the younger children, and decreased with age. Specifically,

perceived parent and teacher support was significantly higher for middle school students than for

high school adolescents. The gender of the student had a significant impact; females Total

support score was significantly higher than the male Total support score. Elementary females

perceived higher support from classmates than elementary males. Middle school and high school

females perceived more support from close friends and classmates, than did their male

counterparts. The study also reported that race and disability status also had an impact on social

support.

In 2003, Demaray and Malecki researched the developmental (elementary, middle, and

high school) and group (race, disability and gender) differences in students perceptions of

support. This study utilized data from extant research resulting in 1,688 students in grades 3

through 12 from seven states.

Results indicated gender differences and grade differences. In terms of gender, girls

reported higher importance scores than boys F (1, 1681) = 15.61, p <.001. Specifically, girls

reported more importance on support from teachers, classmates and close friends, than did boys.

In terms of grade, elementary students considered support to be more important than middle

school students, who considered support to be more important than high school students. The

younger students reported all sources of support as more important.

30

A significant grade and gender interaction was reported, F (2, 1521) = 11.18, p < .001. In

elementary and middle school, both girls and boys reported similar importance scores for social

support. At the high school level, females reported significantly higher rating on the importance

of support than the males. In high school, the females ratings remained consistent, and the

males important ratings dropped. Thus, the gender differences did not occur until the high

school level.

Thus no study of adolescent support should ignore the impact of gender and age. A

preponderance of support studies considering these variables focus on younger children, and

leave the adolescent less explored. The current study takes into account the effects of gender and

age on the perceptions of social support from the high school adolescent.

Adolescent Perceptions of Support

One last aspect to examine from the multifaceted construct of social support is

perception. Whose perception should be taken into account? Demaray & Malecki, (2003)

believe that adolescents perceptions of social support can be the basis for the development of

effective interventions intended to improve academic outcomes. An adolescents perception and

reporting are informative and provide researchers and educators with valuable information on

supportive teacher behaviors that they prefer (Karam, 2006) as well as appropriate parental and

peer behaviors. They articulate their perceptions in a reliable and consistent manner. Research

has shown a direct and positive relationship between students reports of perceived teacher

support and school achievement, academic motivation, and social-emotional and behavior status

(Brand & Felner, 1996; Eccles & Midgley, 1989). According to Wentzel (1997) adolescent

reporting of teacher support is probably a more powerful measurement method than other-person

reporting. Unfortunately, the predominance of the literature does not focus on the perception of

31

the student but from an adults perspective (Major-Ahmed, 2002). Differences between adult

reporting and student perceptions can lead to a misinterpretation of the situation. This current

study relies on the perception of the adolescents as they assess and report on their social support

network.

Conclusion

Several conclusions can be drawn from the extant research and from the empirical studies

in this literature review on social support. Few studies have examined the effects of social

support and the adolescent population, focusing far more on younger children or adults. Many

believe that by third grade, a childs pathways are fairly set (Alexander & Entwisle, 1988). This

generally accepted belief has taken the focus off of examining the adolescent, leaving this age

comparatively less explored (Pianta, 2000).

Traditionally, studies of perceived social support are global in nature, at times

considering one or two sources, and possibly one type of support, usually emotional. This

approach short changes the multifaceted nature of the construct of support. As indicated in the

empirical studies reviewed, more knowledge has been extracted from an examination of the

details of both source and type of support. Support from specific sources, (i.e. parent, teacher,

classmate) offers different forms of support (i.e. emotional, appraisal) that assists the recipient in

accomplishing different tasks and completing various goals. Utilizing only a global examination

of perceived support may result in an inaccurate analysis.

In addition, specific factors of age and gender separately and interactively have been seen

to change the benefits provided by support, and impact the strength of its consequences, yet they

too have been overlooked in the majority of studies. The quantity (frequency) of support has

been far more examined than quality (importance) of support, even though some studies have

32

shown they are two separate constructs resulting in different reactions from subjects. Lastly, the

preponderance of studies are reactive in nature (buffering model), instead of proactive (main

effect model). They focus on how to help people out of bad situations, instead of how to prevent

the occurrence in the first place. Considering all the adolescent violence on the streets and the

recent shootings on school campuses, Columbine and Virginia Tech, researchers need to focus

more time, effort, and, resources on social support as a source of strength for all individuals as it

has been shown to guide adolescents on the path to success, happiness, and, life satisfaction.

This study adds to existing research by studying the impact of the adolescents social

support network. It is an extension of the Malecki and Demaray (2003) study that focused on

middle school students adjustment based on the type of support (emotional, informational,