Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Auscan Issue Paper II

Transféré par

oyyo86Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Auscan Issue Paper II

Transféré par

oyyo86Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Issues Paper II

The Challenge of

Human Resource

Management in

ConflictProne

Situations

The University of New South Wales

Health and Conflict Project

School of Public Health and Community Medicine,

School of Psychiatry, School of Sociology and Anthropology

and the Centre for Culture and Health,

The University of New South Wales

December 2004

Prologue

In September 2003, AusAID funded the Australia-Canada Consortium on Health and Conflict to draw on the

experience of academics and practitioners from Australia and Canada at the interface between health systems and

conflict prevention and peace-building, conflict management and reduction, and support for post-conflict recovery.

The study aims to contribute to the knowledge of, and evidence around, the interface between health and conflict by

documenting experience and identifying good practice.

The initial year of the project was largely devoted to exploring the vast area of health and conflict, types of conflict situations,

and specific country situations. The countries forming part of this study are East Timor, Sri Lanka, Solomon Islands,

Bougainville/PNG, and Cambodia. A two-phase approach has been adopted to drive the project forward. The first phase

predominantly involved secondary research and concentrated largely on framing the research questions. The two initial papers

cover what the team deems essential to introduce the area of health, conflict and peace-building:

I. Health and Peace-building: Securing the Future

II. The Challenge of Human Resource Management in Conflict-Prone Situations

Issues Paper I: Health and Peace-building: Securing the Future sets the scene for contemplating the relationship between

health and peace-building in humanitarian crises and development, specifically focusing on the long-term health and social

impact of violence.

Issues Paper II: The Challenge of Human Resource Management in Conflict-Prone Situations explores the characteristics of

post-conflict and transition periods, and challenges they present to the health workforce.

Preamble

The growing number of states in crisis internationally has created the need for new approaches to global governance to address

the effects of political violence, to prevent conflict, and to build more peaceful societies. The international consensus is that

previous strategies of national development have not realised their goals and that growing levels of poverty are a major cause

of political violence and social insecurity. Moreover it is now realised that any response to humanitarian emergencies must go

beyond relief to address the longer term well-being of populations in distress. Humanitarian responses have been integrated

with development strategies in order to improve human security by addressing the root causes of conflict.

The complexity of current conflicts makes a simple analysis of them hazardous. Too often conflicts are approached as if they

were between clearly identifiable protagonists when in fact they are dynamic and reflect shifting and competing interests both

within and between groups.

Conflict is not just about social breakdown but is also about social transformation. The requirement that humanitarian

assistance and development projects need to be conflict sensitive is recognition of this reality. The do no harm imperative

warns us that current conflicts become symbiotically connected to the social and economic resources introduced into conflict

areas. On both sides there are state and non-state actors as well as legal and illegal business interests which can overlap

producing patterns of cooperative conflict.

The reality that any intervention becomes part of the dynamic of a conflict means we should be modest in evaluating the

conflict prevention and peace-building potential of any particular initiative

Political violence has both human rights and health implications. Addressing the health needs of populations is an important

first step to minimising the effects of violence and promoting peace. But the wider peace benefits of health initiatives must

eventually be linked to broader questions of justice.

Comments on these materials would be appreciated: please submit these to the Project Coordinator, Anne Bunde-Birouste

(ab.birouste@unsw.edu.au) or to the Project Leader, Anthony Zwi (a.zwi@unsw.edu.au). For information on related projects, please

check the project website at http://healthandconflict.sphcm.med.unsw.edu.au/

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Commonwealth of Australia. The Commonwealth

of Australia accepts no responsibility for any loss, damage or injury resulting from reliance on any of the information or views contained in this publication.

Commonwealth of Australia 2004

This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written

permission from the Commonwealth available from the Department of Communications, Information Technology and the Arts. Requests and inquiries

concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Commonwealth Copyright Administration, Intellectual Property Branch, Department of

Communications, Information Technology and the Arts, GPO Box 2154, Canberra ACT 2601 or posted at http://www.dcita.gov.au

Issues Paper II: The Challenge of Human Resource Management in Conflict-Prone Situations

Introduction

Human resources are cited as the most costly

component of health budgets; in many countries

salaries represent 65% to 80% of health system

expenditures. The World Health Report 2000 defines

human resources for health as the stock of all

individuals engaged in the promotion, protection or

improvement of population health. Without skilled

human resources, health services could not be

provided to diagnose, cure, treat and prevent illness

and promote health. Human resource issues are

always sensitive, especially in societies riven by

ethnic, class and other cleavages, when

unemployment is high and the resource base is

limited.

In conflict-prone settings, health services can be a

barometer for tensions in the area. Where conflict is

present public health services tend to disintegrate and

health professionals leave as conflict escalates,

resulting in the closure of hospitals, clinics and aid

posts. This paper discusses the role health workers

may play in unstable settings and responds to five

key questions related to the management and

development of human resources in a conflict prone

environment:

What are the issues to consider in restructuring

the health workforce?

How does one respond to Brain Drain as a result

of insecurity?

How can one get health services up and running

without undermining local capacity?

What is the emerging better practice in

coordinating NGO and donor inputs in the human

resource arena?

What are the issues in financing and funding

human resources in health?

Note: This issues paper is derived from a more comprehensive

background paper. Within the text, the following symbol, ,

accompanied by a reference page number indicates where more

information can be found in the background paper.

Health workers in conflict-prone

settings

Health workers may be among the first to detect

increasing cases of violence or abuse against

particular groups. Less directly they may also see

declining use of services or weakened access to

health care. These warning signs may signal

vulnerability and grievances which in turn may

heighten perceptions of inequalities and injustice.

A situation that could signal a forerunner to

conflict is the deterioration of the economy,

governance and public services such that public

health staff are irregularly paid and supported. For

most skilled staff, this forces them to consider

their options in how and where they work [ 5].

Pre-conflict training during times of relative

peace may be useful

Sri Lanka has been actively involved in the WHO Health

as a Bridge to Peace (HBP) initiative since 1999. HBP

training aims to provide health personnel with the skills

and knowledge to seek out opportunities for peace

building and provides frameworks for delivering health

services in conflict-prone situations.

http://www.who.int/disasters/bridge.cfm

Where salaries are irregular, health workers cope

by undertaking private work, requesting or

demanding something from community members

who use their services, and drawing on their

public position and access to further their private

practice. High rates of absenteeism are common

as staff attend to personal matters and pursue

other economic opportunities. Coping behaviours,

such as directing patients into the private sector,

misappropriating drugs and other strategies

undermine the public health system. Early

appreciation and response to these emerging

practices is important.

The provision of a safe working environment and

personal and professional support for staff who

remain in less secure areas demands innovative

responses. These include:

Decentralising supplies, communications and

logistic support;

Strengthening linkages between the health

workers and the communities they serve;

Facilitating alternative payment systems for

services received and;

Boosting morale by recognising the difficult

circumstances in which health workers operate

and assisting them to see the important role

they have in their community.

Retention of staff may enable services to operate

for longer, may help prevent breakdown of civil

services and could play a role in preventing the

escalation of violence.

The under-explored issue of HIV/AIDS and

Human Resources

HIV/AIDS is often exacerbated in periods of conflict.

Health workers are prone to HIV infection as are other

community members. Rising levels of HIV reduce staff

morale and result in increased workloads and pressure

for remaining health workers. Training and education of

health workers must address both issues affecting their

own risk as well as the role they may play in preventing

HIV transmission in the community. Ongoing attention to

spiralling rates of HIV in some conflict affected areas in

the Asia-Pacific region is warranted.

UNSW Health and Conflict Project 1

Issues Paper II: The Challenge of Human Resource Management in Conflict-Prone Situations

What are the issues to consider in

reconstructing the health

workforce?

needs were so great, that service provision

became an end in itself. In the end we

questioned how much good we have done there.

Human Resources and East Timor

The early stages of rebuilding in East Timor saw a

large proportion of senior staff sponsored to train

overseas at the time, severely reducing the

capacity within the Ministry of Health.

Currently in East Timor, 65 nurses with certificates

or diplomas in nursing have been appointed as

Community Health Centre Managers, a role

requiring a complex set of skills. Training for their

new tasks and responsibilities is required

Skill mix, job design and training

The health system requires a wide range of health

personnel for efficient functioning. In post-conflict

situations, often past expectations cannot be sustained

and more innovative and lower cost mechanisms of

providing services are required. This typically

involves review of roles, up-skilling lower cadre of

staff and involving communities in prevention and

care. The rebuilding phase is likely to result in

reform of the health sector generally; these changes

need to be incorporated into a systematic Health

Workforce, Education and Training Plan [ 3].

Selection for training must be done sensitively

and in line with priority needs to avoid fuelling

perceptions of bias or nepotism that may exist.

Training (through associated per diems)

represents a significant income source for staff

[ Case study 2, 10].

Availability of staff - Staff undertaking training

are absent from regular duties. Training needs

must be balanced against availability of staff to

maintain health services (especially where re-

establishment of community trust in the public

health sector is a concern). Developing

innovative, on the job and distance based

training programs helps overcome this.

Key considerations include:

Management training is a crucial early step,

especially where clinical medical and nursing

staff have been given responsibility for health

service planning and management.

Recognition of existing capacity - Learning

needs of the staff should direct the theme and

content of training rather than the assumptions

of donors or the requirements of particular

vertical programs. Monitor impact of training - Training inputs

must be linked to sustainable change in skill

level and practice. Evaluation of training in the

post-conflict period is often neglected.

Documentation and accreditation systems are

required to recognise and regulate training

undertaken. During periods of conflict,

opportunities for training by different agencies

or in different countries, with different value

systems and approaches, may occur. Subsequent

integration of these personnel is challenging.

Long-term commitment - Investment in training

and building capacity requires a long-term view.

Coordination of training requirements - Ad-

hoc training by multiple donors and NGOs

contributes to the fragmentation of the

workforce. Agreement on the categories of staff,

level of skill required, and reimbursement levels

demands consultation and central planning.

Capacity building and enhancement are

important concepts in development. Many

NGO-employed staff operating in post-conflict

areas reported that while they were told they

were there to develop local capacity, the reality

was they ended up being service providers. The

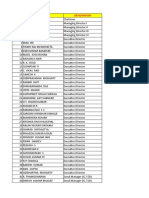

Health Human Resources in North Eastern

Province, Sri Lanka 2000

(Source Tudor Kalinga Silva, 2004)

Category Cadre Vacancies %Vacant

MO-specialist 51 40 78

MO 402 86 21

Pharmacist 133 59 44

PHI 383 139 36

Nurses 1191 511 43

Midwife 1231 679 55

MLT 59 22 37

Microscopist 40 14 35

East Timor: 100 students are to graduate per year

from a new Public Health Worker course offered

through a private university in Dili. There is currently

no agreement with the Ministry of Health as to how

such staff might be utilised.

Sri Lanka: Population Services Lanka (affiliated with

Marie Stopes) has provided on the job training up to

the level of midwife, for more than 300 female

volunteers from local communities. These volunteers

have no educational qualifications and can not be

integrated into current government services.

2 UNSW Health and Conflict Project

Issues Paper II: The Challenge of Human Resource Management in Conflict-Prone Situations

How to respond to Brain Drain

as a result of insecurity?

The loss of skilled staff from the health workforce is

one of the major human resource consequences of

conflict [ 5-7].

External Migration The migration of trained health

personnel often begins at the early stages of

instability; health professionals are more mobile and

are often among the first to flee the country when

conflict breaks out. This exodus during conflict

generally exacerbates an already substantial problem

with loss of skilled personnel to developed countries.

The rebuilding phase should look to address both the

immediate concerns of repatriation of staff and the

broader issues of health personnel migration. Options

which may be considered include:

establishing a register of health personnel that could

return for brief periods of in-country service during

rebuilding phase;

creative contracting with national health services of

receiving countries, including twinning agreements

and joint training arrangements and;

harnessing the support of the Diaspora in structured

ways [ Case study 4, 12].

Internal displacement Staff often move toward secure

areas in the lead up to violent conflict, resulting in

overstaffing in some areas (such as urban hospital

facilities) while health services in other areas are

abandoned. Supporting staff to remain in post in rural

or remote areas requires:

maintenance of basic communication lines;

some system of debriefing and support to assist

workers who are taking on additional roles and

making difficult decisions about who is treated;

maintenance of access to basic supplies required

for service delivery;

building local support networks for personnel

outside the urban centres and;

providing a safer working and living environment

through collaboration with local communities.

Migration out of the public health sector Both

during and following conflict, migration of staff from

the public health system to the private health sector

and to other job opportunities can further weaken

capacity to deliver services. Migration may be

temporary or permanent. NGOs are often accused of

poaching the most competent and committed staff

from public health sector positions to work on their

own projects and programs. Awareness of these

problems and a coordinated response from donors

and other relevant stakeholders is essential as trust

and confidence in the public health services is being

rebuilt.

How can one get health services

up and running without

undermining local capacity?

In post-conflict settings, several cultures and

value systems may be operating. Alongside

available national staff, an influx of foreign staff

and resources associated with humanitarian relief

is common. The challenge facing donors is to

establish functional health services while limiting

interference with the regular workforce. The

following principles may assist donors and other

stakeholders to provide external inputs in a

manner that strengthens local capacity in the

longer term [ 7-9].

Invest early in developing the health sectors

human resources.

Fiji: I left Fiji because I was concerned for my safety

and my familys. The children needed to go to school

where they would not be taunted or threatened. I have

not had my medical qualifications recognised yet in

Australia, but I work in the health system as a

Multicultural Health Worker where my public health

training and skills are being utilisedI am not sure I

would ever return to Fiji, but maybe in time

People in Aid provides resources which may be

useful in bolstering support for health personnel

and addressing Brain Drain concerns.

http://www.peopleinaid.org.uk/

Support the central health authority with

expertise to formulate policy, develop medium

to long term plans and direct service activities.

Work with partners to develop a workforce and

training plan within the framework of National

Health Service planning.

Address the organisational culture of the health

system. The post-conflict period is likely to see

a mix of staff (local and international)

operating in the field under different guidance,

policy assumptions and frameworks. Clinicians

and staff who come from external agencies

may not be sufficiently sensitive to the issues

of working in complex teams where role

delineations are unclear.

Support the integration of traditional health

systems. Conflict may rekindle traditional or

UNSW Health and Conflict Project 3

Issues Paper II: The Challenge of Human Resource Management in Conflict-Prone Situations

What are the issues in financing

and funding human resources in

health?

alternative systems of health care which

continue to be used in the post-conflict period.

Understanding health seeking behaviours and

adopting flexible approaches to supporting the

health of communities is crucial.

Staff salaries, wages, allowances and other benefits

are generally the largest single item of recurrent

expenditure in national health budgets. Immediate

steps to ensure staff continue to receive salaries

during and after conflict may assist in retaining

health personnel in public services and their local

area.

Consider how to accommodate and or regulate

the private health sector. Private provision

often accelerates where governance and public

services are poor. Policy and planning must be

informed by understanding of who provides

services, to whom and how, at what cost and

with what quality.

Understanding different funding streams and

sources of finance are essential for planning

human resource budgets. The transition from

immediate humanitarian relief, where generous

resources are often available for direct service

provision, to more long-term development, which

requires a focus on sustainability, has

implications for who will fund what activities and

how finances will be managed. Despite high

levels of need, donors and multilateral bodies are

often reluctant to contribute to recurrent salary

budgets. They may seek to intervene directly by

establishing vertical programs which they can

monitor or may top-up salaries in selected areas.

This has the potential to contribute to inequalities

and tensions.

A range of providers deliver health services and

contribute to producing health outcomes for the

community. Historically, donors have tended to support

human resource development only within the public

sector. It has been assumed that this will lead to

improved quality and greater demand. Often however,

users prefer traditional or other private practitioners

and use public sector clinics and hospitals as a last

resort. Donors and other stakeholders must recognise

that interventions to enhance the quality of traditional

and private sector care may also be of value.

What is the emerging better

practice in coordinating

NGOs and donor inputs in

the human resource arena?

NGOs often provide critical services in the

immediate relief period. When they withdraw,

the base to continue service provision is often

limited. Planning for the recurrent costs of

delivering care must be undertaken when new

initiatives are being planned.

The responsibility of coordination often falls to a

newly established human resource department

whose staff may have limited capacity to take on this

role. Pressure from individual donors seeking to

implement their own pre-determined projects and or

programs can be especially difficult for the Ministry

of Health (MoH) staff. The establishment of a policy

setting body within the MoH in the form of a

coordinating committee (such as CoCom in

Cambodia) has many benefits. Such a committee

may adopt a variety of roles: identifying the

categories of staff and agreed skill level for health

workers and minimum training required for each

category; acting as a mechanism for monitoring and

evaluating international aid agencies; advising the

MoH regarding planning coordination and

implementation of services; overseeing training

activities and ensuring that development and

distribution of skilled personnel is consistent with

national health service plans; and promoting

coordination of local payment scales between

international agencies [ Case study 3, 11].

There is a clear need to build information

systems to manage, deploy and develop the

human resource base. Attention needs to be

devoted to updating and maintaining data on staff

at appropriate levels in the system. Personnel

files may become outdated, central authorities

may lose contact with remote staff and ghosting,

where salaries are being drawn for staff who are

no longer serving in the public sector, may occur.

Protecting and developing the human resource

base in conflict-prone and post-conflict settings is

a challenge. Although human resources appear to

be simply technical they need to be examined in

relation to broader peace-building needs and

related policy and planning. Early and sustained

attention is a necessary element for effective

response.

Investing early in long-term HR development is a key component of building more

effective and sustainable health systems which can address the legacy of conflict.

4 UNSW Health and Conflict Project

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Salary Data 18092018Document5 124 pagesSalary Data 18092018pjrkrishna100% (1)

- Buffett Wisdom On CorrectionsDocument2 pagesBuffett Wisdom On CorrectionsChrisPas encore d'évaluation

- Contoh Kuda-Kuda Untuk Pak Henry Truss D&EKK1L KDocument1 pageContoh Kuda-Kuda Untuk Pak Henry Truss D&EKK1L KDhany ArsoPas encore d'évaluation

- Account Statement From 1 Oct 2018 To 15 Mar 2019: TXN Date Value Date Description Ref No./Cheque No. Debit Credit BalanceDocument8 pagesAccount Statement From 1 Oct 2018 To 15 Mar 2019: TXN Date Value Date Description Ref No./Cheque No. Debit Credit BalancerohantPas encore d'évaluation

- Why Is Inventory Turnover Important?: ... It Measures How Hard Your Inventory Investment Is WorkingDocument6 pagesWhy Is Inventory Turnover Important?: ... It Measures How Hard Your Inventory Investment Is WorkingabhiPas encore d'évaluation

- Manual de Parts ES16D6Document36 pagesManual de Parts ES16D6Eduardo CortezPas encore d'évaluation

- Caso 1 - Tunel Sismico BoluDocument4 pagesCaso 1 - Tunel Sismico BoluCarlos Catalán CórdovaPas encore d'évaluation

- UNIT 2 - ConnectivityDocument41 pagesUNIT 2 - ConnectivityZain BuhariPas encore d'évaluation

- DuraBlend 4T Newpi 20W50Document2 pagesDuraBlend 4T Newpi 20W50Ashish VashisthaPas encore d'évaluation

- Goal of The Firm PDFDocument4 pagesGoal of The Firm PDFSandyPas encore d'évaluation

- S No. Store Type Parent ID Partner IDDocument8 pagesS No. Store Type Parent ID Partner IDabhishek palPas encore d'évaluation

- UntitledDocument1 pageUntitledsai gamingPas encore d'évaluation

- The 8051 Microcontroller & Embedded Systems: Muhammad Ali Mazidi, Janice Mazidi & Rolin MckinlayDocument15 pagesThe 8051 Microcontroller & Embedded Systems: Muhammad Ali Mazidi, Janice Mazidi & Rolin MckinlayAkshwin KisorePas encore d'évaluation

- Republic vs. CA (G.R. No. 139592, October 5, 2000)Document11 pagesRepublic vs. CA (G.R. No. 139592, October 5, 2000)Alexandra Mae GenorgaPas encore d'évaluation

- DOL, Rotor Resistance and Star To Delta StarterDocument8 pagesDOL, Rotor Resistance and Star To Delta StarterRAMAKRISHNA PRABU GPas encore d'évaluation

- Book Shop InventoryDocument21 pagesBook Shop InventoryAli AnsariPas encore d'évaluation

- BBA Lecture NotesDocument36 pagesBBA Lecture NotesSaqib HanifPas encore d'évaluation

- Manual On Power System ProtectionDocument393 pagesManual On Power System ProtectionSakthi Murugan88% (17)

- Autonics KRN1000 DatasheetDocument14 pagesAutonics KRN1000 DatasheetAditia Dwi SaputraPas encore d'évaluation

- Rule 63Document43 pagesRule 63Lady Paul SyPas encore d'évaluation

- AbDocument8 pagesAbSehar BanoPas encore d'évaluation

- NATIONAL DEVELOPMENT COMPANY v. CADocument11 pagesNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT COMPANY v. CAAndrei Anne PalomarPas encore d'évaluation

- Ex-Capt. Harish Uppal Vs Union of India & Anr On 17 December, 2002Document20 pagesEx-Capt. Harish Uppal Vs Union of India & Anr On 17 December, 2002vivek6593Pas encore d'évaluation

- Forod 2bac en s2 6 PDFDocument4 pagesForod 2bac en s2 6 PDFwwe foreverPas encore d'évaluation

- STAAD Seismic AnalysisDocument5 pagesSTAAD Seismic AnalysismabuhamdPas encore d'évaluation

- HAART PresentationDocument27 pagesHAART PresentationNali peterPas encore d'évaluation

- Transparency in Organizing: A Performative Approach: Oana Brindusa AlbuDocument272 pagesTransparency in Organizing: A Performative Approach: Oana Brindusa AlbuPhương LêPas encore d'évaluation

- Gears, Splines, and Serrations: Unit 24Document8 pagesGears, Splines, and Serrations: Unit 24Satish Dhandole100% (1)

- Food Truck Ordinance LetterDocument7 pagesFood Truck Ordinance LetterThe Daily News JournalPas encore d'évaluation

- Meeting Protocol and Negotiation Techniques in India and AustraliaDocument3 pagesMeeting Protocol and Negotiation Techniques in India and AustraliaRose4182Pas encore d'évaluation