Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Analysis of Parmegianis Incidences-Resonances-libre

Transféré par

John HawkwoodCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Analysis of Parmegianis Incidences-Resonances-libre

Transféré par

John HawkwoodDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

MMus Electroacoustic Music Composition

An Analysis of

Bernard Parmegianis Incidences/Resonances

through Spectromorphology, Spectral Analysis

and Graphical Score.

Craig Burgess

$

Introduction.

The intention of this paper is to analyse Bernard Parmegianis

Incidences/Resonances

1

and explore the relationships between the various

forms of transformed sound material present within the work.

The aim of the analysis is to explore compositional structure and sound

material through spectromorphology, spectral analysis and graphical score to

gain insight and interpret the material present, developing an understanding

of the intrinsic relationships that sound objects share as they interact.

This investigation into the sound material will be supported through the

implementation of a graphical score and spectrogram to illustrate the structure

and aesthetic make-up of the work.

1

See Bernard Parmegiani, Parmegiani: De Natura Sonorum (Version Integrale), INA-GRM

Ina C 3001, 2000 (reissue of 1975 recording).

%

Methods of Analysis and Historical Background.

In order to fully explore the sound objects

2

and compositional framework

present in Parmegianis Incidences/Resononances, a method of analysis

was sough to explain the detail inherent within the material.

There are a number of theoretical concepts, approaches and techniques

widely implemented within the electroacoustic compositional framework which

help to enable the description and interpretation of sound objects.

Pierre Schaeffer developed one of the first techniques and approaches with

which to classify and interpret sound objects in his publication Trait des

objets musicaux (1966), lauded as the first significant work to elaborate on

the spectral and morphological characteristics of sound.

3

However it has been found to be difficult to interpret and apply Pierre

Schaeffers typomorphology in a practical context, as commented on by

Thoresen (2007):

!developed in the 1960s, Schaeffer proposed a variety of novel

terms, but they have not been widely used since they unfortunately

did not lend themselves very well to practical analysis.

4

2

Sound objects are created from combining source material, be it the onset from a

percussive hit on a metallic surface or the continuant bell-like drone that emanates from each

initial hit, gradually fluctuating and growing, morphing into the next sound object.

3

See Aki Pasoulas, in: An Overview of Score and Performance in Electroacoustic Music,

Canadian Electroacoustic Community, (Accessed 4th December 2011),

<http://cec.sonus.ca/econtact/10_4/pasoulas_score.html>.

4

See Lasse Thoresen and Andreas Hedman, Spectromorphological analysis of sound

objects: an adaptation of Pierre Schaeffer's typomorphology, Organised Sound, Vol. 12, No.

2, (2007), 129.

&

Spectromorphology

Denis Smalley claims his concept of spectromorphology

5

could be a useful

tool for the purpose of analytical and descriptive exploration as it enables a

comprehensive and detailed approach that builds on the groundwork put in

place by Pierre Schaeffers Trait des objets musicaux. He states:

A spectromorphological approach sets out spectral and

morphological models and processes, and provides a framework

for understanding structural relations and behaviours as

experienced in the temporal flux of the music.

6

On this basis spectromorphology could be useful as a method of investigating

sound object relationships within Incidences/Resonances as it allows a way

of describing and analysing sound object material in both a focused and wider

context. This allows the listener to comment on the relationships and concepts

present within he work on a number of levels. Smalley continues by stating:

Spectromorphology is not a compositional theory or method, but a

descriptive tool based on aural perception. It is intended to aid

listening, and seeks to help explain what can be apprehended in

over four decades of electroacoustic repertory.

7

5

Smalley expresses the concept and terminology of spectromorphology as tools for

describing and analysing listening experience. The two parts of the term refer to the

interaction between sound spectra (spectro-) and the ways they change and are shaped

through time (-morphology). The spectro- cannot exist without the -morphology and vice

versa: something has to be shaped, and a shape must have sonic content. See Denis

Smalley, Spectromorphology: explaining sound-shapes, Organised Sound, Vol. 2, No. 2.

(1997), 107.

6

Ibid.

7

Ibid. 113.

'

Spectromorphological Expectation.

One particularly effective aspect of Smalleys spectromorphological

framework, in terms of exploring the intrinsic details of the sound object

material and therefore its inter-relationships and characteristics, is the

category of spectromorphological expectation.

Smalley describes spectromorphological expectation in the following way:

Every note must start in some way; some may be sustained or

prolonged for a time and some may not; every note stops.

8

Smalley continues by discussing three linked temporal phases, which he

refers to as onset, continuant and termination:

They are not distinctly separable: we cannot tell the very moment

when an onset passes into a continuant phase, nor when a

continuant passes into the terminal phase. Nor do all three phases

have to be present in the note-gesture.

9

Incidences/Resonances incorporates what could be described as multiple

instances of onset, continuation and termination in terms of sound object

relationships that occur, not just within the individual sound objects

themselves but also across wider sections of the piece as sound objects

combine. These sections lead into one another to create the piece as a whole.

Therefore it is useful to consider Smalleys concept in different contexts and

on different levels when referring to Incidences/Resonances as a whole.

8

Ibid. 112.

9

Ibid. 113.

(

Each phase of Smalleys spectromorphological expectation category has an

accompanying set of archetypes that Smalley uses to describe specific

features and phases of the sound object. He asserts that In all three models

spectral richness is assumed to be congruent with the dynamic shape of the

morphology, the louder, the more spectral energy, the brighter and/or richer

the sound.

10

Smalley details these three archetypes in his Spectromorphology article as:

The attack alone. This is a momentary energetic impulse. Two temporal

phases are merged into one there is a sudden onset, which is also

the termination. Awareness is focused on the attack-energy.

The attack-decay. The attack is extended by a resonance. The onset

and terminatory phases are present, and there may be a hint of the

continuant. In this archetype an initial gesture is enough to set a

spectromorphology in motion, after which there is no gestural

intervention as the sound continues towards termination.

The graduated continuant. In this archetype all three phases are

present. The onset starts gradually as if faded in, and the note

terminates gradually as if faded out. In between, the note is sustained

for a time.

11

10

Ibid. 113.

11

Ibid. 113.

)

This form of description is useful in relation to Incidences/Resonances as it

allows us to accurately describe individual sound objects commonly found

within the material as well as considering the work as a whole. In addition, it

also provides us with precise terminology with which to do so. For example,

at a peripheral level the piece has several sections that combine to create

larger sections, which eventually form the piece as a whole. The opening

section could be described as a combination of attack alone and attack decay

onsets that precede a graduated continuant stage populated by sustained

drones.

A number of sound objects found within Incidences/Resonances are created

by the transformation of original source material from both natural sounds and

electronically generated material. In keeping with the acousmatic tradition of

decoupling source-bonded

12

material, Parmegiani manipulates sound objects

to create new material that has little or no resemblance to the original source.

He achieves through the manipulation of source material by removing a

constituent portion of original sound material and marrying it with another,

unrelated sound object. The combination of concrete with electronically

generated material is utilized frequently to create sound objects that have little

to do with the original source. This concept is at the very essence of the piece

and is reflected not only in its title of but also in Smalleys terms, onsets,

continuants and terminations. Trevor Wishart comments on the combining of

12

See Denis Smalley, Space-form and the acousmatic image, Organised Sound, Vol. 12,

No. 1, (2007), 38.

#

sound material stating duality refers to the use of recognisable sounds which

have been reordered in such a way as to appear almost abstract.

13

There are numerous relationships and events present, not only between the

individual sound objects but also the differing sections of the work, collectively

creating larger sound objects, interactions and parts. Smalley reinforces this

in his article stating:

At one moment in a work one may be following discrete, short

units, and at another a large-scale structure whose continuity and

coherence refuse to be dissected and demand to be considered

more as a whole than as the sum of minute parts.

14

13

Wishart, Trevor, On Sonic Art - Revised Edition London, 1996,137

14

See also the comments in Smalley, Spectromorphology: explaining sound-shapes, 114.

*

The First Listen Graphical Score+

When first approaching the task of analysing and detailing the piece the

decision was made to create a set of rough graphical sketches to highlight

sound objects inherent within the work and to provide a visual representation.

(See Appendix A: First listening score).

The first listen graphical score was undertaken at an early stage to enable an

overview of the work as a whole, as a comparative alternative to the

spectrogram. It was also helpful in aiding the realisation of a final, detailed

analysis of Incidences/Resonances.

The shapes used were simple, intuitive, graphical interpretations of what the

sound objects might look like if one was to visualize the sonic material. An

approach followed which involved the quick jotting down of shapes as they

first came to mind, allowing the capture of initial visual interpretation of the

sound material. This enabled a further level of familiarisation with the piece.

,"

Spectral Analysis

Spectral analysis (See Appendix B: Spectrogram) was applied to the piece to

reinforce the information provided by the first listening graphical scores.

15

In

addition, a further visual aid was generated utilising SPEAR spectral analysis,

editing and synthesis software

16

(See Appendix C: SPEAR spectral partial

analysis) to highlight spectral relationships.

This information helped to provide an initial insight into the relationships

shared between sound objects. Relationships such as harmonic, spectral,

duration and comparative levels were easily identifiable from the spectral

analysis. This information was then used to define events that could be

deemed onset, continuant and termination properties of the sound objects as

well as collective sections.

Figure 1 illustrates the entirety of Incidences/Resonances in the form of a

spectrogram. From this initial first glance of the material in spectral form it is

easy to pick out some of the more obvious sound object events within the

piece. For example, the extended resonant material, appearing as horizontal

lines stretching across the graph, and short percussive based incidences that

dissect the graph from top to bottom as vertical lines at various points. The

resultant visual information also highlights some material that appeared to be

missing from the graphical score in terms of harmonic relationships, exact

temporal information and durations.

15

See Alexander Kojevnikov,, in: SPEK Spectral Analysis Software, Spek Acoustic

Spectrum Analyser, (Accessed 2

nd

November 2011), <http://spek-project.org>.

16

See Michael Klingbeil, in: SPEAR Sinusoidal Partial Editing Analysis and Resynthesis

Spear Spectral Analysis and Resynthesis Software, (Accessed 5th November 2011),

<http://www.klingbeil.com/spear>.

,,

Fig 1: Spectral analysis

The piece is introduced (0:00-0:48) with a series of attack alone transients,

momentary energetic impulses that suddenly terminate. The sudden onsets

then combine with extended resonant fluctuations, morphing and combining to

create graduated continuants. The continuant drones are broken by attack

alone onsets that briefly combine with, and at other junctures, abruptly

terminate the existing drone material

The transition to the next section occurs through an abrupt (0:48-0:50)

succession of attack alone onsets. These introduce intermittent, attack decay

sound objects (0:48-1:14) that pan left and right at a steady temporal rate.

Sound object material is reintroduced, in the form of resonant continuant

drone, (1:00) from the introductory section. The gradual attack of the drone

continuants is masked by the sharp attack alone onsets, which then introduce

,$

a splitting of the continuant into harmonic partials, creating a spectrally rich

bed.

This relationship between the attack alone, attack decay and graduated

continuant sound objects is a recurring theme within Parmegiani!s piece.

Fig 2: 2 minutes 40 seconds illustrating harmonic relationships.

,%

The spectrogram enables a detailed focus on the piece, highlighting key

information within the work. In particular the spectrogram in Figure 2

illustrates quite clearly that in the final section of Incidences/Resonances

there are fluctuating harmonic relationships (2:30-4:00) between the

continuant drone material. Visually this information manifests itself as

horizontal parallel lines that stretch out across the latter duration of the piece.

The spectrally bright drone builds through this harmonic stacking of partials

that fill out the piece and are caused by the introduction of additional material.

These delicate fluctuations create an overall feeling of instability in the section

as they oscillate and intertwine. This continuant drone is punctuated again

and again, creating a building sense of suspense and drama. This relationship

between the continuant drone and the attack onsets occur at regular junctures

within the piece and form a key aspect of the work. At many parts the attack

onsets terminate the continuant drone signaling the end of one oscillation and

creating another.

Over the course of the piece (1:30-2:30) the resonant drone continuant

material takes on a more menacing role, fading only to return, as a result of

this termination by the attack onset. It then builds, overwhelming other

elements until they are reintroduced in startling fashion by another onset,

bringing us back into the context of the whole piece. Thomas Blum in his 1981

article reinforces this aspect of Incidences/Resonances stating:

,&

[The piece] is successful in that it integrates contradictory sonic

materials in such a way that they form a whole musical

environment.

17

The incident attack onset elements have clear transient detail that force the

listener to take notice alerting them to the start and/or end of a sound object

relationship. The initial incident attack onset is followed by more attack

onsets, which morph into graduated drone continuant sound objects. The

relationship between the abrupt attack onset and the continuant drone is a

common feature of the piece. There are examples of this at the beginning of

the piece (0:14) as well as at a number of other junctures (0:30-1:40, 2:00-

2:40, 3:18) where the incident onsets punctuate the drone and produce

variations in the steady underlying continuant. There is an element of

combination within the material that is broken by the abrupt interruptions of

the incidental sound objects. This termination yields new relationships and

signals new sections. The onset attacks slightly increase in both amplitude

and spectral brightness as the piece continues within its first minute, which

can be seen from the spectrogram as increasingly defined vertical lines.

(Figure 3)

17

See Thom Blum, De Natura Sonorum Review, Computer Music Journal: Vol. 5 No.2,

(1981), 70.

,'

Fig 3: Attack onsets increase in both spectral brightness and amplitude.

As discussed, interesting examples of multiple attack onsets and their

interactions are clear within the piece at numerous stages. Parmegiani uses

the incident attack onsets as signifiers or instructions as to the potential sonic

pathway the drone-like continuant sound objects must take. It is almost

analogous with an army general relaying commands and orders to his troops.

Caleb Deupree, in his English interpretation of Jean-Jacques Nattiezs 1982

publication L'Envers d'une oeuvre

18

comments on the interrupting nature of

the attack onsets stating:

18

See Philippe Mion, Jean-Jacques Nattiez and Jean-Christophe Thomas, L'envers d'une

uvre. De Natura Sonorum de Bernard Parmegiani, Paris, 1982.

,(

[There is an] interruption of an incident into a resonance (or a

continuum) [where the] incidents are "foreign bodies" that interfere

with the development of the sound; taken from a material different

from the continuum (for example a crystal strike in a long metallic

resonance), the foreign body perturbs the continuum in different

ways; in general by modifying the harmonic web, thickening,

doubling!sometimes completely changing the continuum.

19

The attack onset sound objects are utilised in other ways to signify changes in

the continuant drone material, as can be heard in the first minute of the piece.

(0:48-0:52) There is repetition of the same metallic-like transient onset attacks

at specific points. These then terminate abruptly, introducing a division of the

drone into short, intermittent, regular bursts that resemble telephonic beeps.

This relationship is mirrored in the latter sections of the piece (2:40-3:40),

although the continuant material is retained. In this section the attack onsets

create fluctuations in the drone continuant that cause it to change in terms of

its fundamental frequency and overall stability.

Considering the information provided by the first listening of the graphical

score and the spectrogram, an awareness of the detail of the piece and of its

shape and sound object relationships was formed, creating a mental picture of

the work. Through this sectioning and defining of sound object placement

19

See Caleb Deupree, in: De Natura Sonorum 1 & 4 Classic Drone (Accessed 23rd

November 2011), <http://classicaldrone.blogspot.com/2010/05/de-natura-sonorum-1-and-

4.html>.

,)

within the material, how the sound objects combined and interacted became

clearer.

Incidences/Resonances has a narrative quality where sound object

relationships are explored through transformation and acousmatic practice.

Each successive sound object is perceived in context with the last. This raised

questions relating to Parmegianis own compositional strategies and structure

and intended use of sound object relationships based on time and memory. In

particular these questions relate to the relationships between sound objects,

temporal information, placement and intrinsic qualities of individual sound

object material present and how the juxtaposed sound object material

changes how we perceive the piece as a whole.

Emmerson comments on the use of time within the structure of

electroacoustic compositions in Time Regained:

Our apprehension of the present and its apparent trajectory within

an immediately perceived environment: the changing now. What

happened an instant ago may influence what I am hearing now.

20

There are numerous examples within Incidences/Resonances (0:48-0:50,

1:14, 1:20, 3:12-4:00) where sound objects of differing structure interact and

affect the listeners perception of the work. As previously discussed, at the

beginning of the piece there is a sharp, incident attack onset that gives rise to

an elongated drone continuant that leads us into the next sound object. Later

20

See Simon, Emmerson, Time Regained, Bourges Academy: Time in Electroacoustic

Music, (2000), 84.

,#

in the piece, (1:30, 2:45) as the material progresses, the drone continuants

combine with other continuant sound objects, creating denser, spectrally

richer beds that are then smashed by sudden and unexpected percussive

attack onsets, varying in timbre, texture and velocity.

Smalley describes these sharp, incident attack onsets as attack-impulses that

are modelled on the single detached note: a sudden onset, which is

immediately terminated. In this instance the attack-onset is also the

termination.

21

This combining of sound objects to create new larger scale sound objects is a

recurrent theme within Incidences/Resonances. Parmegiani ultilises this

method, using contrasting sound object material to expand on perceptions

and interpretation of the listening material. The way the sound object material

interacts and progresses is an important aspect of the piece. The continuous

morphing of the resonant pitched material interact creating rich harmonic

content in sections of the piece. (1:28-2:30, 2:42-3:50) The resulting

combinations create fluctuations that are then cut off by sharp, abrupt,

percussive elements. (Figure 4) Examples of this can be found in abundance

in the piece but especially after the first and beyond the second minutes

(1:31-2:30), and also in the latter section, before they ebb away at the close.

(2:32-4:00) The spectrogram clearly illustrates this relationship, which can be

seen as spectrally bright groupings of parallel lines stretching across several

sections of the piece.

$,

See also the comments in Smalley, Spectromorphology: explaining sound-shapes, 115.

,*

Fig 4: Harmonically richer sections that are abruptly terminated by attack onsets.

An exploration by Parmegiani himself into the transitional, morphological

nature of the transformed compositional material provides clues to the

compositional strategy and methodologies employed in the creation of

Incidences/Resonances. There is a distinct pairing of sound object content

that deliberately juxtapose material that belongs to only one of either the

incidences or resonances categories.

Caleb Deupree reinforces this concept in his English interpretation of Jean-

Jacques Nattiezs L'Envers d'une oeuvre

22

commenting:

Parmegiani demonstrated a real mastery of the theoretical

principles detailed in Schaeffer's massive Trait des objets

22

See also comments in Philippe Mion, Jean-Jacques Nattiez and Jean-Christophe Thomas,

L'envers d'une uvre. De Natura Sonorum de Bernard Parmegiani,

$"

musicaux and catalogued all of his sounds for De Natura Sonorum

using Schaeffer's typology.

23

Unfortunately there is a lack of primary information or official translations into

English relating to Parmegianis thoughts on De Natura Sonorum. Therefore

attempts to interpret Jean-Jacques Nattiez ideas on Parmegiani need to be

approached with caution.

Within his work Parmegiani presents material in a number of different contexts

and from a range of sources. He attempts to explore the possibilities of

combining material and the interactive qualities and relationships that are

formed through this exploration. Parmegiani comments on his initial intentions

when composing the work in L'Envers d'une oeuvre:

I wanted to check out the different ways that concrete elements

could combine with electronic elements, always seeking a certain

homogeneity. It was about making composite objects, where the

attack was concrete and the resonance electronic. In spite of the

artificial operation of the montage, I stayed within the natural logic

of the percussive objects (percussion-resonance).

24

There is evidence at numerous points within the work of this exploration in

terms of the placement and combining of material that can be seen within the

spectrogram and graphical score. Clear examples of recorded, percussive

and metallic sound objects (0:50, 1:01, 1:21, 1:30, 2:03, 2:12-2:21, 2:40)

23

See Caleb Deupree, in: Bernard in book Classic Drone (Accessed 10th November 2011),

<http://classicaldrone.blogspot.com/2010/05/bernard-in-book.html>.

24

See also comments in Caleb Deupree, in: De Natura Sonorum 1 & 4 Classic Drone

(Accessed 23rd November 2011), <http://classicaldrone.blogspot.com/2010/05/de-natura-

sonorum-1-and-4.html>.

$,

married with the continuant passages and prolongations are found in a

number of places. These attack onsets play an agentive role, triggering the

continuants that tie together and transition not just the sound objects

themselves but also the sections of the piece. They bring rise to the very

make up of the piece, creating resonant continuants that gradually fade into

the piece or are abruptly terminated by the onset of more percussive attacks.

Nattiez again details Parmegianis own thoughts on combining concrete with

electronically generated material:

In this piece, concrete sounds only appear as points, and

everything that is prolonged is electronic!the sounding objects

that I used don't have long resonance!They obey the law of rapid

decay, well known and rather banal. When all is said and done,

striking a crystal glass (one of the sources in the piece) and

removing its attack is nothing more or less than a very poor

resonance, almost pure, which one could create electronically. So

it's the sharpness, the attack, that's interesting. This is why I sought

in this piece to play with a variety of different attacks.

25

Relationships between sound objects are at the forefront of

Incidences/Resonances along with how these relationships manifest

themselves as resultant sonic material. An interesting aspect of the work is

how these relationships offer clues as to how the next sound object may be

interpreted, having perceived the last, concentrating on the formation of new

relationships!between two sets of sounds with contrasting sonic

25

See also comments in Philippe Mion, Jean-Jacques Nattiez and Jean-Christophe Thomas,

L'envers d'une uvre. De Natura Sonorum de Bernard Parmegiani,

$$

properties.

26

In addition to looking at the onset, continuant and termination properties of the

sound objects present it is useful to briefly explore the intrinsic spectral

density of the sound object material found within Incidences/Resonances.

An interesting aspect of Incidences/Resonances is the harmonic relationship

between the sustained, resonant drone-like material, as well as the attack

onsets. There are frequent occurrences across the duration of the piece

where the sustained drones combine and interact in terms of their spectral

content. In addition the attack onsets act as punctuating instances that

terminate the drone and bring about a change, either in fundamental pitch

and/or spectral/harmonic stability. As previously discussed, much of the attack

onset material is captured concrete material from sources such as bells and

other metallic objects. Smalley comments on harmonicity, stating:

!bell and metallic resonances are the usual examples of

inharmonicity, and they suitably represent the inharmonic dilemma

because inharmonic spectra can be ambiguous in that they can

include some intervallic pitches. To be regarded as properly

authentic, an inharmonic spectrum cannot be resolved as a single

note, and its pitch-components need to be considered relative, not

intervallic. As a result, continuous inharmonic spectra have a

tendency to disperse into streams.

27

26

See also comments in Thom Blum, De Natura Sonorum Review, Computer Music Journal:

Vol. 5 No.2, (1981), 68.

27

See also comments in Denis Smalley, Spectromorphology: explaining sound-shapes,

Organised Sound, Vol. 2, No. 2. (1997), 120.

$%

When analyzing Incidences/Resonances, for example, at 1 minute 30

seconds and 2 minutes 30, the attack onset brings on a splitting of spectral

and harmonic content that combines to create a rich inharmonic bed that

gradually rises in frequency until fading towards the end of the piece.

$&

Conclusion.

The descriptive terminology of spectromorphological expectation was

reinforced with information highlighted by the spectrogram and first listen

score thus enabling a mixed perspective to be applied when analysing the

material.

Many of the concepts and details within Smalleys Spectromorphology

framework are useful as descriptive and analytical tools, in particular, when

investigating the relationships within the piece in relation to individual sound

objects and their constituent parts. However, due the vastness of Smalleys

research and work it is difficult to include an exhaustive list here and many of

the associated facets of the work are beyond the scope of this paper.

In terms of taking an initial view of Parmegianis compositional techniques,

spectromorphological expectation is effective in supporting the relationships

between the sound objects and sections of the work by providing a stable

platform to expand with future research. The terminology and descriptive

qualities aid the exploration of sound objects and their relationships at multiple

levels across the duration of the piece; not just individual sound objects but

also larger sections and the work as a whole.

$'

Appendix A:

First Listen Graphical Score.

$(

$)

Appendix B:

Spectrogram created using SPEK spectral analysis software.

$#

Appendix C:

SPEAR spectral analysis, editing and synthesis software.

$*

Bibliography:

Blum, Thom, De Natura Sonorum Review, Computer Music Journal: Vol. 5

No.2, (1981), 68-70.

Deupree, Caleb, in: De Natura Sonorum 1 & 4 Classic Drone (Accessed 23rd

November 2011), <http://classicaldrone.blogspot.com/2010/05/de-natura-

sonorum-1-and-4.html>.

Deupree, Caleb, in: Bernard in book Classic Drone (Accessed 10th

November 2011), <http://classicaldrone.blogspot.com/2010/05/bernard-in-

book.html>.

Emmerson, Simon, Time Regained, Bourges Academy: Time in

Electroacoustic Music, (2000), 84-86.

Klingbeil, Michael, in: SPEAR Sinusoidal Partial Editing Analysis and

Resynthesis Spear Spectral Analysis and Resynthesis Software, (Accessed

5th November 2011), <http://www.klingbeil.com/spear>.

Kojevnikov, Alexander, in: SPEK Spectral Analysis Software, Spek Acoustic

Spectrum Analyser, (Accessed 2

nd

November 2011), <http://spek-

project.org>.

Mion, Philippe, Jean-Jacques Nattiez and Jean-Christophe Thomas, L'envers

d'une uvre. De Natura Sonorum de Bernard Parmegiani, Paris, 1982.

Parmegiani Bernard, Parmegiani: De Natura Sonorum (Version Integrale),

INA-GRM Ina C 3001, 2000 (reissue of 1975 recording).

Pasoulas, Aki, in: An Overview of Score and Performance in Electroacoustic

Music, Canadian Electroacoustic Community, (Accessed 4th December

2011), <http://cec.sonus.ca/econtact/10_4/pasoulas_score.html>.

Smalley, Denis, Space-form and the acousmatic image, Organised Sound,

Vol. 12, No. 1, (2007), 35-58.

Smalley, Denis, Spectromorphology: explaining sound-shapes, Organised

Sound, Vol. 2, No. 2. (1997), 107-126.

Thoresen, Lasse and Andreas Hedman, Spectromorphological analysis of

sound objects: an adaptation of Pierre Schaeffer's typomorphology,

Organised Sound, Vol. 12, No. 2, (2007), 129-141.

Wishart, Trevor, On Sonic Art - Revised Edition, London, 1996.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Lasse Thoresen - SoundObjectsDocument13 pagesLasse Thoresen - SoundObjectschmr thrPas encore d'évaluation

- Kompositionen für hörbaren Raum / Compositions for Audible Space: Die frühe elektroakustische Musik und ihre Kontexte / The Early Electroacoustic Music and its ContextsD'EverandKompositionen für hörbaren Raum / Compositions for Audible Space: Die frühe elektroakustische Musik und ihre Kontexte / The Early Electroacoustic Music and its ContextsPas encore d'évaluation

- Spectromorphological Analysis of Sound Objects PDFDocument13 pagesSpectromorphological Analysis of Sound Objects PDFlupustarPas encore d'évaluation

- SLAWSON - The Color of SoundDocument11 pagesSLAWSON - The Color of SoundEmmaPas encore d'évaluation

- P.Kokoras - Towards A Holophonic Musical TextureDocument3 pagesP.Kokoras - Towards A Holophonic Musical TextureuposumasPas encore d'évaluation

- Electroacoustic Music Studies and Accepted Terminology: You Can't Have One Without The OtherDocument8 pagesElectroacoustic Music Studies and Accepted Terminology: You Can't Have One Without The OtherJonathan HigginsPas encore d'évaluation

- Music For Solo Performer by Alvin Lucier in An Investigation of Current Trends in Brainwave SonificationDocument23 pagesMusic For Solo Performer by Alvin Lucier in An Investigation of Current Trends in Brainwave SonificationJeremy WoodruffPas encore d'évaluation

- An Introduction To Acoustic EcologyDocument4 pagesAn Introduction To Acoustic EcologyGilles Malatray100% (1)

- Straebel-Sonification MetaphorDocument11 pagesStraebel-Sonification MetaphorgennarielloPas encore d'évaluation

- Process Orchestration A Complete Guide - 2020 EditionD'EverandProcess Orchestration A Complete Guide - 2020 EditionPas encore d'évaluation

- Kontakte by Karlheinz Stockhausen in Four Channels: Temporary Analysis NotesDocument16 pagesKontakte by Karlheinz Stockhausen in Four Channels: Temporary Analysis NotesAkaratcht DangPas encore d'évaluation

- Contemporary Music Review: Publication Details, Including Instructions For Authors and Subscription InformationDocument17 pagesContemporary Music Review: Publication Details, Including Instructions For Authors and Subscription InformationJoao CardosoPas encore d'évaluation

- Luigi NonoDocument3 pagesLuigi NonomikhailaahteePas encore d'évaluation

- Alvin Lucier's Natural Resonant FrequenciesDocument3 pagesAlvin Lucier's Natural Resonant FrequenciesKimberly SuttonPas encore d'évaluation

- The Emancipation of Referentiality Through The Use of Microsounds and Electronics in The Music of Luigi NonoDocument7 pagesThe Emancipation of Referentiality Through The Use of Microsounds and Electronics in The Music of Luigi NonoFelipe De Almeida RibeiroPas encore d'évaluation

- Being Within Sound PDFDocument5 pagesBeing Within Sound PDFR.s. WartsPas encore d'évaluation

- John Cage - Experimental Music DoctrineDocument5 pagesJohn Cage - Experimental Music Doctrineworm123_123Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Road To Plunderphonia - Chris Cutler PDFDocument11 pagesThe Road To Plunderphonia - Chris Cutler PDFLeonardo Luigi PerottoPas encore d'évaluation

- Pierre Schaeffer in Search of A Concrete PDFDocument3 pagesPierre Schaeffer in Search of A Concrete PDFLeena LeePas encore d'évaluation

- Interview With Maryanne AmacherDocument6 pagesInterview With Maryanne AmacherSimon Baier100% (1)

- WISHART Trevor - Extended Vocal TechniqueDocument3 pagesWISHART Trevor - Extended Vocal TechniqueCarol MoraesPas encore d'évaluation

- Sonification of GesturesDocument18 pagesSonification of GesturesAndreas AlmqvistPas encore d'évaluation

- Gerard Grisey: The Web AngelfireDocument8 pagesGerard Grisey: The Web AngelfirecgaineyPas encore d'évaluation

- Questions For K StockhausenDocument5 pagesQuestions For K StockhausenPabloPas encore d'évaluation

- Stockhausen On Electronics, 2004Document8 pagesStockhausen On Electronics, 2004Mauricio DradaPas encore d'évaluation

- PKokoras WestPole ScoreDocument30 pagesPKokoras WestPole ScoreKodokuna BushiPas encore d'évaluation

- (Article) Momente' - Material For The Listener and Composer - 1 Roger SmalleyDocument7 pages(Article) Momente' - Material For The Listener and Composer - 1 Roger SmalleyJorge L. SantosPas encore d'évaluation

- The Studio As Compositional ToolDocument4 pagesThe Studio As Compositional ToolpauljebanasamPas encore d'évaluation

- Sound Listening and Place The Aesthetic PDFDocument9 pagesSound Listening and Place The Aesthetic PDFMickey ValleePas encore d'évaluation

- Scelsi - AionDocument3 pagesScelsi - AionFrancisVincent0% (1)

- Towards A Grammatical Analysis of Scelsi's Late MusicDocument26 pagesTowards A Grammatical Analysis of Scelsi's Late MusicieysimurraPas encore d'évaluation

- Horacio Vaggione - CMJ - Interview by Osvaldo BudónDocument13 pagesHoracio Vaggione - CMJ - Interview by Osvaldo BudónAlexis PerepelyciaPas encore d'évaluation

- Terrible Freedom: The Life and Work of Lucia DlugoszewskiD'EverandTerrible Freedom: The Life and Work of Lucia DlugoszewskiPas encore d'évaluation

- Dhomont InterviewDocument13 pagesDhomont InterviewImri TalgamPas encore d'évaluation

- Irin Micromontage in Graphical Sound Editing and Mixing Tool PDFDocument4 pagesIrin Micromontage in Graphical Sound Editing and Mixing Tool PDFAnonymous AqIXCfpPas encore d'évaluation

- Stephane Roy - Form and Referencial Citation in A Work by Francis Dhomont - 1996 - Analise - EletroacusticaDocument13 pagesStephane Roy - Form and Referencial Citation in A Work by Francis Dhomont - 1996 - Analise - Eletroacusticaricardo_thomasiPas encore d'évaluation

- Morris-Letters To John CageDocument11 pagesMorris-Letters To John Cagefrenchelevator100% (1)

- Sound in Space, Space in Sound Session 6Document23 pagesSound in Space, Space in Sound Session 6speculPas encore d'évaluation

- Contemporary Music Review: To Cite This Article: François Bayle (1989) Image-Of-Sound, or I-Sound: Metaphor/metaformDocument7 pagesContemporary Music Review: To Cite This Article: François Bayle (1989) Image-Of-Sound, or I-Sound: Metaphor/metaformHansPas encore d'évaluation

- Spectral MusicDocument6 pagesSpectral MusicTheWiki96Pas encore d'évaluation

- Alvin Lucier, Music 184, by Nic CollinsDocument73 pagesAlvin Lucier, Music 184, by Nic CollinsEduardo Moguillansky100% (1)

- Space Form and The Acousmatic Image - Denis Smalley PDFDocument25 pagesSpace Form and The Acousmatic Image - Denis Smalley PDFPaul Chauncy100% (1)

- Improvisation As Dialectic in Vinko Globokar's CorrespondencesDocument36 pagesImprovisation As Dialectic in Vinko Globokar's CorrespondencesMarko ŠetincPas encore d'évaluation

- Desintegrations y Analisis EspectralDocument12 pagesDesintegrations y Analisis EspectralDavid Cuevas SánchezPas encore d'évaluation

- Essay On Cage & SchaferDocument8 pagesEssay On Cage & SchaferMestre AndréPas encore d'évaluation

- From Organs To Computer MusicDocument16 pagesFrom Organs To Computer Musicjoesh2Pas encore d'évaluation

- Hernandez Lanza Aschenblume PDFDocument29 pagesHernandez Lanza Aschenblume PDF1111qwerasdf100% (1)

- Imaginary Landscape - John CageDocument10 pagesImaginary Landscape - John CageagusxiaolinPas encore d'évaluation

- Charles Ivess Use of Quartertones Are TH PDFDocument8 pagesCharles Ivess Use of Quartertones Are TH PDFEunice ng100% (1)

- AS-Cross Synthesis Handbook PDFDocument80 pagesAS-Cross Synthesis Handbook PDFArchil GiorgobianiPas encore d'évaluation

- Maryanne Amacher, "City-Links"Document14 pagesMaryanne Amacher, "City-Links"Christoph Cox100% (1)

- Jonty Harrison Sound DiffusionDocument11 pagesJonty Harrison Sound DiffusionfilipestevesPas encore d'évaluation

- Analisis Electronic Music - Marco StroppaDocument7 pagesAnalisis Electronic Music - Marco StroppadavidPas encore d'évaluation

- D Sound Spatialization Using Ambisonic T PDFDocument14 pagesD Sound Spatialization Using Ambisonic T PDFMariana Sepúlveda MoralesPas encore d'évaluation

- Jurg Frey - Life Is Present (1996)Document1 pageJurg Frey - Life Is Present (1996)Enrique R. PalmaPas encore d'évaluation

- SpectralDocument5 pagesSpectralTimónPas encore d'évaluation

- Graphic ScoreDocument5 pagesGraphic ScoreAlmasi GabrielPas encore d'évaluation

- B Tech ECE Courses NBADocument4 pagesB Tech ECE Courses NBAPratyush ChauhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Document Trafag PD3.4Document7 pagesDocument Trafag PD3.4Rick Van den BosPas encore d'évaluation

- Introductory Circuit Theory by Guillemin ErnstDocument580 pagesIntroductory Circuit Theory by Guillemin ErnstJunaid IqbalPas encore d'évaluation

- Section 133123Document11 pagesSection 133123Dian Aplimon JohannisPas encore d'évaluation

- Leica CME ManualDocument24 pagesLeica CME ManualMaria DapkeviciusPas encore d'évaluation

- Chemical Engineering Design Problems (Undergrad Level)Document10 pagesChemical Engineering Design Problems (Undergrad Level)smeilyPas encore d'évaluation

- Form 4 Chemistry Yearly Plan 2019Document2 pagesForm 4 Chemistry Yearly Plan 2019Jenny WeePas encore d'évaluation

- Design and Evaluation of Sustained Release Microcapsules Containing Diclofenac SodiumDocument4 pagesDesign and Evaluation of Sustained Release Microcapsules Containing Diclofenac SodiumLia Amalia UlfahPas encore d'évaluation

- GGHHHDocument3 pagesGGHHHjovica37Pas encore d'évaluation

- Flexibility FactorsDocument61 pagesFlexibility FactorsCarlos BorgesPas encore d'évaluation

- Sample 7613Document11 pagesSample 7613VikashKumarPas encore d'évaluation

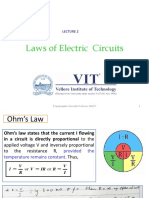

- Laws of Electric Circuits: R.Jayapragash, Associate Professor, SELECT 1Document25 pagesLaws of Electric Circuits: R.Jayapragash, Associate Professor, SELECT 1Devansh BhardwajPas encore d'évaluation

- Calculus OnlineDocument2 pagesCalculus Onlineapi-427949627Pas encore d'évaluation

- 7UT51x Manual UsDocument232 pages7UT51x Manual UsMtdb Psd100% (1)

- 2017 - OPUS Quant Advanced PDFDocument205 pages2017 - OPUS Quant Advanced PDFIngeniero Alfonzo Díaz Guzmán100% (1)

- Positioning of Air Cooled CondensersDocument9 pagesPositioning of Air Cooled CondensersAlexPas encore d'évaluation

- Nastran DST Group TN 1700Document69 pagesNastran DST Group TN 1700Minh LePas encore d'évaluation

- Lab 2Document5 pagesLab 2Adeem Hassan KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- En Jkm320pp (4bb)Document2 pagesEn Jkm320pp (4bb)Ronal100% (1)

- 6226 e CTM Second EditionDocument228 pages6226 e CTM Second EditionNuriaReidPas encore d'évaluation

- Engine Control SystemDocument7 pagesEngine Control SystemFaisal Al HusainanPas encore d'évaluation

- ECB Non Turf Cricket Wicket PDFDocument23 pagesECB Non Turf Cricket Wicket PDFJames OttaPas encore d'évaluation

- Bio Well InformationDocument5 pagesBio Well InformationPradyuman PatelPas encore d'évaluation

- Answer of Midterm Exam 2 PDFDocument6 pagesAnswer of Midterm Exam 2 PDFFaisal Al-assafPas encore d'évaluation

- Sound Power and IntensityDocument8 pagesSound Power and Intensitymandeep singhPas encore d'évaluation

- Calculus For Business and Social SciencesDocument5 pagesCalculus For Business and Social SciencesMarchol PingkiPas encore d'évaluation

- Abrasive SDocument3 pagesAbrasive SmurusaPas encore d'évaluation

- False-Position Method of Solving A Nonlinear Equation: Exact RootDocument6 pagesFalse-Position Method of Solving A Nonlinear Equation: Exact Rootmacynthia26Pas encore d'évaluation

- 2nd Semester Latest 21Document75 pages2nd Semester Latest 21Mugars Lupin ArsenePas encore d'évaluation