Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Gr174585 Ledesma Vs NLRC

Transféré par

Nesrene Emy Lleno0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

31 vues13 pagesGr174585 Ledesma vs Nlrc

Titre original

Gr174585 Ledesma vs Nlrc

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

DOCX, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentGr174585 Ledesma vs Nlrc

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme DOCX, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

31 vues13 pagesGr174585 Ledesma Vs NLRC

Transféré par

Nesrene Emy LlenoGr174585 Ledesma vs Nlrc

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme DOCX, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 13

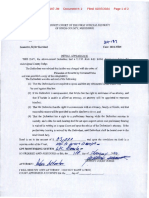

THIRD DIVISION

FEDERICO M. LEDESMA, JR.,

Petitioner,

- versus -

NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS

COMMISSION (NLRC-SECOND

DIVISION) HONS. RAUL T.

AQUINO, VICTORIANO R.

CALAYCAY and ANGELITA A.

GACUTAN ARE THE

COMMISSIONERS, PHILIPPINE

NAUTICAL TRAINING INC., ATTY.

HERNANI FABIA, RICKY TY, PABLO

MANOLO, C. DE LEON and TREENA

CUEVA,

Respondents.

G.R. No. 174585

Present:

YNARES-SANTIAGO, J.,

Chairperson,

AUSTRIA-MARTINEZ,

CORONA,

CHICO-NAZARIO, and

NACHURA, JJ.

Promulgated:

October 19, 2007

x- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -x

D E C I S I O N

CHICO-NAZARIO, J.:

This a Petition for Review on Certiorari under Rule 45 of the Revised Rules

of Court, filed by petitioner Federico Ledesma, Jr., seeking to reverse and set aside

the Decision,

1

dated 28 May 2005, and the Resolution,

2

dated 7 September 2006,

of the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R. SP No. 79724. The appellate court, in its

assailed Decision and Resolution, affirmed the Decision dated 15 April 2003, and

Resolution dated 9 June 2003, of the National Labor Relations Commission

(NLRC), dismissing petitioners complaint for illegal dismissal and ordering the

1

Penned by Associate Justice Ruben T. Reyes (now a member of this Court) with Associate

Justices Josefina Guevarra-Salonga and Fernanda Lampas-Peralta , concurring. Rollo, pp. 38-50.

2

Rollo, pp. 52-53.

private respondent Philippine National Training Institute (PNTI) to reinstate

petitioner to his former position without loss of seniority rights.

The factual and procedural antecedents of the instant petition are as follows:

On 4 December 1998, petitioner was employed as a bus/service driver by the

private respondent on probationary basis, as evidenced by his appointment.

3

As

such, he was required to report at private respondents training site in Dasmarias,

Cavite, under the direct supervision of its site administrator, Pablo Manolo de Leon

(de Leon).

4

On 11 November 2000, petitioner filed a complaint against de Leon for

allegedly abusing his authority as site administrator by using the private

respondents vehicles and other facilities for personal ends. In the same complaint,

petitioner also accused de Leon of immoral conduct allegedly carried out within

the private respondents premises. A copy of the complaint was duly received by

private respondents Chief Accountant, Nita Azarcon (Azarcon).

5

On 27 November 2000, de Leon filed a written report against the petitioner

addressed to private respondents Vice-President for Administration, Ricky Ty

(Ty), citing his suspected drug use.

In view of de Leons report, private respondents Human Resource

Manager, Trina Cueva (HR Manager Cueva), on 29 November 2000, served a copy

of a Notice to petitioner requiring him to explain within 24 hours why no

disciplinary action should be imposed on him for allegedly violating Section 14,

Article IV of the private respondents Code of Conduct.

6

On 3 December 2000, petitioner filed a complaint for illegal dismissal

against private respondent before the Labor Arbiter.

3

Id. at 82.

4

Id.

5

Id. at 85-86.

6

Id. at 107.

In his Position Paper,

7

petitioner averred that in view of the complaint he

filed against de Leon for his abusive conduct as site administrator, the latter

retaliated by falsely accusing petitioner as a drug user. VP for Administration Ty,

however, instead of verifying the veracity of de Leons report, readily believed his

allegations and together with HR Manager Cueva, verbally dismissed petitioner

from service on 29 November 2000.

Petitioner alleged that he was asked to report at private respondents main

office in Espaa, Manila, on 29 November 2000. There, petitioner was served by

HR Manager Cueva a copy of the Notice to Explain together with the copy of de

Leons report citing his suspected drug use. After he was made to receive the

copies of the said notice and report, HR Manager Cueva went inside the office of

VP for Administration Ty. After a while, HR Manager Cueva came out of the

office with VP for Administration Ty. To petitioners surprise, HR Manager

Cueva took back the earlier Notice to Explain given to him and flatly declared that

there was no more need for the petitioner to explain since his drug test result

revealed that he was positive for drugs. When petitioner, however, asked for a

copy of the said drug test result, HR Manager Cueva told him that it was with the

companys president, but she would also later claim that the drug test result was

already with the proper authorities at Camp Crame.

8

Petitioner was then asked by HR Manager Cueva to sign a resignation letter

and also remarked that whether or not petitioner would resign willingly, he was no

longer considered an employee of private respondent. All these events transpired

in the presence of VP for Administration Ty, who even convinced petitioner to just

voluntarily resign with the assurance that he would still be given separation pay.

Petitioner did not yet sign the resignation letter replying that he needed time to

think over the offers. When petitioner went back to private respondents training

7

Id. at 71-81.

8

Id.

site in Dasmarias, Cavite, to get his bicycle, he was no longer allowed by the

guard to enter the premises.

9

On the following day, petitioner immediately went to St. Dominic Medical

Center for a drug test and he was found negative for any drug substance. With his

drug result on hand, petitioner went back to private respondents main office in

Manila to talk to VP for Administration Ty and HR Manager Cueva and to show to

them his drug test result. Petitioner then told VP for Administration Ty and HR

Manager Cueva that since his drug test proved that he was not guilty of the drug

use charge against him, he decided to continue to work for the private

respondent.

10

On 2 December 2000, petitioner reported for work but he was no longer

allowed to enter the training site for he was allegedly banned therefrom according

to the guard on duty. This incident prompted the petitioner to file the complaint

for illegal dismissal against the private respondent before the Labor Arbiter.

For its part, private respondent countered that petitioner was never dismissed

from employment but merely served a Notice to Explain why no disciplinary

action should be filed against him in view of his superiors report that he was

suspected of using illegal drugs. Instead of filing an answer to the said notice,

however, petitioner prematurely lodged a complaint for illegal dismissal against

private respondent before the Labor Arbiter.

11

Private respondent likewise denied petitioners allegations that it banned the

latter from entering private respondents premises. Rather, it was petitioner who

failed or refused to report to work after he was made to explain his alleged drug

use. Indeed, on 3 December 2000, petitioner was able to claim at the training site

his salary for the period of 16-30 November 2000, as evidenced by a copy of the

pay voucher bearing petitioners signature. Petitioners accusation that he was no

longer allowed to enter the training site was further belied by the fact that he was

9

Id.

10

Id.

11

Id. at 91-105.

able to claim his 13

th

month pay thereat on 9 December 2000, supported by a copy

of the pay voucher signed by petitioner.

12

On 26 July 2002, the Labor Arbiter rendered a Decision,

13

in favor of the

petitioner declaring illegal his separation from employment. The Labor Arbiter,

however, did not order petitioners reinstatement for the same was no longer

practical, and only directed private respondent to pay petitioner backwages. The

dispositive portion of the Labor Arbiters Decision reads:

WHEREFORE, premises considered, the dismissal of the [petitioner] is

herein declared to be illegal. [Private respondent] is directed to pay the

complainant backwages and separation pay in the total amount of One Hundred

Eighty Four Thousand Eight Hundred Sixty One Pesos and Fifty Three Centavos

(P184, 861.53).

14

Both parties questioned the Labor Arbiters Decision before the NLRC.

Petitioner assailed the portion of the Labor Arbiters Decision denying his prayer

for reinstatement, and arguing that the doctrine of strained relations is applied only

to confidential employees and his position as a driver was not covered by such

prohibition.

15

On the other hand, private respondent controverted the Labor

Arbiters finding that petitioner was illegally dismissed from employment, and

insisted that petitioner was never dismissed from his job but failed to report to

work after he was asked to explain regarding his suspected drug use.

16

On 15 April 2003, the NLRC granted the appeal raised by both parties and

reversed the Labor Arbiters Decision.

17

The NLRC declared that petitioner failed

to establish the fact of dismissal for his claim that he was banned from entering the

training site was rendered impossible by the fact that he was able to subsequently

claim his salary and 13

th

month pay. Petitioners claim for reinstatement was,

however, granted by the NLRC. The decretal part of the NLRC Decision reads:

12

Id.

13

Id. at 65-70.

14

Id.

15

Id. at 144-160.

16

Id. at 160-172.

17

Id. at 54-64.

WHEREFORE, premises considered, the decision under review is, hereby

REVERSED and SET ASIDE, and another entered, DISMISSING the complaint

for lack of merit.

[Petitioner] is however, ordered REINSTATED to his former position

without loss of seniority rights, but WITHOUT BACKWAGES.

18

The Motion for Reconsideration filed by petitioner was likewise denied by

the NLRC in its Resolution dated 29 August 2003.

19

The Court of Appeals dismissed petitioners Petition for Certiorari under

Rule 65 of the Revised Rules of Court, and affirmed the NLRC Decision giving

more credence to private respondents stance that petitioner was not dismissed

from employment, as it is more in accord with the evidence on record and the

attendant circumstances of the instant case.

20

Similarly ill-fated was petitioners

Motion for Reconsideration, which was denied by the Court of Appeals in its

Resolution issued on 7 September 2006.

21

Hence, this instant Petition for Review on Certiorari

22

under Rule 45 of the

Revised Rules of Court, filed by petitioner assailing the foregoing Court of

Appeals Decision and Resolution on the following grounds:

I.

WHETHER, THE HON. COURT OF APPEALS COMMITTED A

MISAPPREHENSION OF FACTS, AND THE ASSAILED DECISION IS NOT

SUPPORTED BY THE EVIDENCE ON RECORD. PETITIONERS

DISMISSAL WAS ESTABLISHED BY THE UNCONTRADICTED

EVIDENCES ON RECORD, WHICH WERE MISAPPRECIATED BY PUBLIC

RESPONDENT NLRC, AND HAD THESE BEEN CONSIDERED THE

INEVITABLE CONCLUSION WOULD BE THE AFFIRMATION OF THE

LABOR ARBITERS DECISION FINDING ILLEGAL DISMISSAL

II.

WHETHER, THE HON. COURT OF APPEALS SUBVERTED DUE PROCESS

OF LAW WHEN IT DID NOT CONSIDER THE EVIDENCE ON RECORD

SHOWING THAT THERE WAS NO JUST CAUSE FOR DISMISSAL AS

18

Id. at 63.

19

Id. at 42.

20

Id. at 38-50.

21

Id. at 52-53.

22

Id. at 12-36.

PETITIONER IS NOT A DRUG USER AND THERE IS NO EVIDENCE TO

SUPPORT THIS GROUND FOR DISMISSAL.

III.

WHETHER, THE HON. COURT OF APPEALS COMMITTED REVERSIBLE

ERROR OF LAW IN NOT FINDING THAT RESPONDENTS SUBVERTED

PETITIONERS RIGHT TO DUE PROCESS OF THE LAW.

23

Before we delve into the merits of this case, it is best to stress that the issues

raised by petitioner in this instant petition are factual in nature which is not within

the office of a Petition for Review.

24

The raison detre for this rule is that, this

Court is not a trier of facts and does not routinely undertake the re-examination of

the evidence presented by the contending parties for the factual findings of the

labor officials who have acquired expertise in their own fields are accorded not

only respect but even finality, and are binding upon this Court.

25

However, when the findings of the Labor Arbiter contradict those of the

NLRC, departure from the general rule is warranted, and this Court must of

necessity make an infinitesimal scrunity and examine the records all over again

including the evidence presented by the opposing parties to determine which

findings should be preferred as more conformable with evidentiary facts.

26

The primordial issue in the petition at bar is whether the petitioner was

illegally dismissed from employment.

The Labor Arbiter found that the petitioner was illegally dismissed from

employment warranting the payment of his backwages. The NLRC and the Court

of Appeals found otherwise.

In reversing the Labor Arbiters Decision, the NLRC underscored the settled

evidentiary rule that before the burden of proof shifts to the employer to prove the

23

Id. at 236-237.

24

Limketkai Sons Milling, Inc. v. Llamera, G.R. No. 152514, 12 July 2005, 463 SCRA 254, 260.

25

Dusit Hotel Nikko v. National Union of Workers in Hotel, Restaurant and Allied Industries (NUWHRAIN),

Dusit Hotel Nikko Chapter, G.R. No. 160391, 9 August 2005, 466 SCRA 374, 387-388; The Philippine

American Life and General Insurance Co. v. Gramaje, G.R. No. 156963, 11 November 2004, 442 SCRA

274, 283.

26

Sta. Catalina College v. National Labor Relations Commission, 461 Phil. 720, 730 (2003).

validity of the employees dismissal, the employee must first sufficiently establish

that he was indeed dismissed from employment. The petitioner, in the present

case, failed to establish the fact of his dismissal. The NLRC did not give credence

to petitioners allegation that he was banned by the private respondent from

entering the workplace, opining that had it been true that petitioner was no longer

allowed to enter the training site when he reported for work thereat on 2 December

2000, it is quite a wonder he was able to do so the very next day, on 3 December

2000, to claim his salary.

27

The Court of Appeals validated the above conclusion reached by the NLRC

and further rationated that petitioners positive allegations that he was dismissed

from service was negated by substantial evidence to the contrary. Petitioners

averments of what transpired inside private respondents main office on 29

November 2000, when he was allegedly already dismissed from service, and his

claim that he was effectively banned from private respondents premises are belied

by the fact that he was able to claim his salary for the period of 16-30 November

2000 at private respondents training site.

Petitioner, therefore, is now before this Court assailing the Decisions handed

down by the NLRC and the Court of Appeals, and insisting that he was illegally

dismissed from his employment. Petitioner argues that his receipt of his earned

salary for the period of 16-30 November 2000, and his 13

th

month pay, is neither

inconsistent with nor a negation of his allegation of illegal dismissal. Petitioner

maintains that he received his salary and benefit only from the guardhouse, for he

was already banned from the work premises.

We are not persuaded.

Well-entrenched is the principle that in order to establish a case before

judicial and quasi-administrative bodies, it is necessary that allegations must be

supported by substantial evidence.

28

Substantial evidence is more than a mere

27

Rollo, pp. 118-119.

28

Philippine Air Line v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 159556, 26 May 2005, 459 SCRA 236, 251.

scintilla. It means such relevant evidence as a reasonable mind might accept as

adequate to support a conclusion.

29

In the present case, there is hardly any evidence on record so as to meet the

quantum of evidence required, i.e., substantial evidence. Petitioners claim of

illegal dismissal is supported by no other than his own bare, uncorroborated and,

thus, self-serving allegations, which are also incoherent, inconsistent and

contradictory.

Petitioner himself narrated that when his presence was requested on 29

November 2000 at the private respondents main office where he was served with

the Notice to Explain his superiors report on his suspected drug use, VP for

Administration Ty offered him separation pay if he will just voluntarily resign

from employment. While we do not condone such an offer, neither can we

construe that petitioner was dismissed at that instance. Petitioner was only being

given the option to either resign and receive his separation pay or not to resign but

face the possible disciplinary charges against him. The final decision, therefore,

whether to voluntarily resign or to continue working still, ultimately rests with the

petitioner. In fact, by petitoners own admission, he requested from VP for

Administration Ty more time to think over the offer.

Moreover, the petitioner alleged that he was not allowed to enter the training

site by the guard on duty who told him that he was already banned from the

premises. Subsequently, however, petitioner admitted in his Supplemental

Affidavit that he was able to return to the said site on 3 December 2000, to

claim his 16-30 November 2000 salary, and again on 9 December 2000, to

receive his 13

th

month pay. The fact alone that he was able to return to the training

site to claim his salary and benefits raises doubt as to his purported ban from the

premises.

Finally, petitioners stance that he was dismissed by private respondent was

further weakened with the presentation of private respondents payroll bearing

29

Government Service Insurance System v. Court of Appeals, 357 Phil. 511, 531 (1998).

petitioners name proving that petitioner remained as private respondents

employee up to December 2000. Again, petitioners assertion that the payroll was

merely fabricated for the purpose of supporting private respondents case before

the NLRC cannot be given credence. Entries in the payroll, being entries in the

course of business, enjoy the presumption of regularity under Rule 130, Section 43

of the Rules of Court. It is therefore incumbent upon the petitioner to adduce clear

and convincing evidence in support of his claim of fabrication and to overcome

such presumption of regularity.

30

Unfortunately, petitioner again failed in such

endeavor.

On these scores, there is a dearth of evidence to establish the fact of

petitioners dismissal. We have scrupulously examined the records and we found

no evidence presented by petitioner, other than his own contentions that he was

indeed dismissed by private respondent.

While this Court is not unmindful of the rule that in cases of illegal

dismissal, the employer bears the burden of proof to prove that the termination was

for a valid or authorized cause in the case at bar, however, the facts and the

evidence did not establish a prima facie case that the petitioner was dismissed from

employment.

31

Before the private respondent must bear the burden of proving that

the dismissal was legal, petitioner must first establish by substantial evidence the

fact of his dismissal from service. Logically, if there is no dismissal, then there

can be no question as to the legality or illegality thereof.

In Machica v. Roosevelt Services Center, Inc.,

32

we had underscored that the

burden of proving the allegations rest upon the party alleging, to wit:

The rule is that one who alleges a fact has the burden of proving

it; thus, petitioners were burdened to prove their allegation that respondents

dismissed them from their employment. It must be stressed that the evidence to

prove this fact must be clear, positive and convincing. The rule that the

30

Id. at 529.

31

Schering Employees Labor Union (SELU) v. Schering Plough Corporation, G.R. No. 142506, 17

February 2005, 451 SCRA 689, 695.

32

G.R. No. 168664, 4 May 2006, 389 SCRA 534.

employer bears the burden of proof in illegal dismissal cases finds no application

here because the respondents deny having dismissed the petitioners.

33

In Rufina Patis Factory v. Alusitain,

34

this Court took the occasion to

emphasize:

It is a basic rule in evidence, however, that the burden of proof is on the

part of the party who makes the allegations ei incumbit probatio, qui dicit, non

qui negat. If he claims a right granted by law, he must prove his claim by

competent evidence, relying on the strength of his own evidence and not upon

the weakness of that of his opponent.

35

It is true that the Constitution affords full protection to labor, and that in

light of this Constitutional mandate, we must be vigilant in striking down any

attempt of the management to exploit or oppress the working class. However, it

does not mean that we are bound to uphold the working class in every labor dispute

brought before this Court for our resolution.

The law in protecting the rights of the employees, authorizes neither

oppression nor self-destruction of the employer. It should be made clear that when

the law tilts the scales of justice in favor of labor, it is in recognition of the inherent

economic inequality between labor and management. The intent is to balance the

scales of justice; to put the two parties on relatively equal positions. There may be

cases where the circumstances warrant favoring labor over the interests of

management but never should the scale be so tilted if the result is an injustice to

the employer. Justitia nemini neganda est -- justice is to be denied to none.

36

WHEREFORE, premises considered, the instant Petition is DENIED. The

Court of Appeals Decision dated 28 May 2005 and its Resolution dated 7

September 2006 in CA-G.R. SP No. 79724 are hereby AFFIRMED. Costs against

the petitioner.

33

Id. at 544-545.

34

G.R. No. 146202, 14 July 2004, 434 SCRA 418.

35

Id. at 428.

36

JPL Marketing Promotions v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 151966, 8 July 2005, 463 SCRA 136,

149-150.

SO ORDERED.

MINITA V. CHICO-NAZARIO

Associate Justice

WE CONCUR:

CONSUELO YNARES-SANTIAGO

Associate Justice

Chairperson

MA. ALICIA AUSTRIA-MARTINEZ RENATO C. CORONA

Associate Justice Associate Justice

ANTONIO EDUARDO B. NACHURA

Associate Justice

ATTESTATION

I attest that the conclusions in the above Decision were reached in

consultation before the case was assigned to the writer of the opinion of the

Courts Division.

CONSUELO YNARES-SANTIAGO

Associate Justice

Chairperson, Third Division

CERTIFICATION

Pursuant to Section 13, Article VIII of the Constitution, and the Division

Chairpersons Attestation, it is hereby certified that the conclusions in the above

Decision were reached in consultation before the case was assigned to the writer of

the opinion of the Courts Division.

REYNATO S. PUNO

Chief Justice

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Branch - : People of The Philippines Criminal Case No. XXXXX For: "Malicious Mischief"Document2 pagesBranch - : People of The Philippines Criminal Case No. XXXXX For: "Malicious Mischief"Nesrene Emy LlenoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Demand Letter VacateDocument1 pageDemand Letter VacateNesrene Emy LlenoPas encore d'évaluation

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- House Bill NoDocument242 pagesHouse Bill NoNesrene Emy LlenoPas encore d'évaluation

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Demand Letter VacateDocument1 pageDemand Letter VacateNesrene Emy LlenoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Demand Letter VacateDocument1 pageDemand Letter VacateNesrene Emy LlenoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Rules Adoption LocalDocument15 pagesRules Adoption LocalNesrene Emy LlenoPas encore d'évaluation

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Duties of A LawyerDocument4 pagesDuties of A LawyerNesrene Emy LlenoPas encore d'évaluation

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Demand Letter VacateDocument1 pageDemand Letter VacateNesrene Emy LlenoPas encore d'évaluation

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Cagayan Valley Drug Vs CIR DigestDocument1 pageCagayan Valley Drug Vs CIR DigestNesrene Emy LlenoPas encore d'évaluation

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- Cagayan Valley Drug Vs CirDocument6 pagesCagayan Valley Drug Vs CirNesrene Emy LlenoPas encore d'évaluation

- Cezar vs. RTCDocument7 pagesCezar vs. RTCherbs22225847Pas encore d'évaluation

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Reasons For Lawyers To Cease From Practicing Their ProfessionDocument5 pagesReasons For Lawyers To Cease From Practicing Their ProfessionNesrene Emy LlenoPas encore d'évaluation

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Atuel Vs ValdezDocument8 pagesAtuel Vs ValdezNesrene Emy LlenoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Ballatan Vs CADocument9 pagesBallatan Vs CANesrene Emy LlenoPas encore d'évaluation

- Gr149177 Hasegawa Vs KitamuraDocument13 pagesGr149177 Hasegawa Vs KitamuraNesrene Emy LlenoPas encore d'évaluation

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Cecilia Castillo Vs Angeles BalinghasayDocument5 pagesCecilia Castillo Vs Angeles BalinghasayNesrene Emy LlenoPas encore d'évaluation

- Gr160325 Duterte Vs KingswoodDocument10 pagesGr160325 Duterte Vs KingswoodNesrene Emy LlenoPas encore d'évaluation

- Disini v. Secretary of Justice GR 203335Document38 pagesDisini v. Secretary of Justice GR 203335Eric RamilPas encore d'évaluation

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- GR L-18660 People Vs DelimaDocument1 pageGR L-18660 People Vs DelimaNesrene Emy LlenoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Corporal v. NLRCDocument7 pagesCorporal v. NLRCLansingPas encore d'évaluation

- Gr182498 Razon V TagitisDocument69 pagesGr182498 Razon V TagitisNesrene Emy LlenoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- GR 171053Document8 pagesGR 171053Nesrene Emy LlenoPas encore d'évaluation

- Gr178920 Manalo V PNP ChiefDocument18 pagesGr178920 Manalo V PNP ChiefNesrene Emy LlenoPas encore d'évaluation

- Gr204819 Imbong V OchoaDocument98 pagesGr204819 Imbong V OchoaNesrene Emy LlenoPas encore d'évaluation

- GR146494 Gsis VS MontesclarosDocument12 pagesGR146494 Gsis VS MontesclarosNesrene Emy LlenoPas encore d'évaluation

- Gr182795 Canlas V NapicoDocument5 pagesGr182795 Canlas V NapicoNesrene Emy LlenoPas encore d'évaluation

- B. Mayor LIM V CADocument9 pagesB. Mayor LIM V CARadz BolambaoPas encore d'évaluation

- Gr192935 Biraogo V PTCDocument38 pagesGr192935 Biraogo V PTCNesrene Emy LlenoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Gr145848 Namada Vs Davao SugarDocument5 pagesGr145848 Namada Vs Davao SugarNesrene Emy LlenoPas encore d'évaluation

- Gr166152 Villamor Golf Vs PehidDocument16 pagesGr166152 Villamor Golf Vs PehidNesrene Emy LlenoPas encore d'évaluation

- Poblete Construction v. SSCDocument1 pagePoblete Construction v. SSCLoreen DanaoPas encore d'évaluation

- Case DigestDocument12 pagesCase DigestMareniela Nicole MergenioPas encore d'évaluation

- People vs. GonzalesDocument1 pagePeople vs. GonzalesRobPas encore d'évaluation

- Buryakov Plea AgreementDocument5 pagesBuryakov Plea AgreementmashablescribdPas encore d'évaluation

- Alabang Development Corp. Vs ValenzuelaDocument11 pagesAlabang Development Corp. Vs ValenzuelaMarizPatanaoPas encore d'évaluation

- Cases in Support of CJI As RespondentDocument1 pageCases in Support of CJI As RespondentRaviteja PadiriPas encore d'évaluation

- Wilson Ong Ching Kian Chuan v. CADocument6 pagesWilson Ong Ching Kian Chuan v. CAMadam JudgerPas encore d'évaluation

- Secretary of Justice Vs Lantion and Mark JimenezDocument1 pageSecretary of Justice Vs Lantion and Mark JimenezJalefaye BasiliscoPas encore d'évaluation

- Virginia Calalang: Register of Deeds of Quezon CityDocument9 pagesVirginia Calalang: Register of Deeds of Quezon CityAlianna Arnica MambataoPas encore d'évaluation

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Rule 110 Prosecution of OffensesDocument3 pagesRule 110 Prosecution of OffensesPatrick SilveniaPas encore d'évaluation

- Rule 42, Section 1-4 - MAGNODocument38 pagesRule 42, Section 1-4 - MAGNOMay RMPas encore d'évaluation

- Petition To Enforce Parenting Time OrderDocument3 pagesPetition To Enforce Parenting Time Orderrpotter122914Pas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Randall, 472 F.3d 763, 10th Cir. (2006)Document8 pagesUnited States v. Randall, 472 F.3d 763, 10th Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Velasquez v. Bledsoe - Document No. 4Document2 pagesVelasquez v. Bledsoe - Document No. 4Justia.comPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Harold Lynch, 792 F.2d 269, 1st Cir. (1986)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Harold Lynch, 792 F.2d 269, 1st Cir. (1986)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Pcu Spec Pro SyllabusDocument3 pagesPcu Spec Pro SyllabusBoms BomsPas encore d'évaluation

- People v. MagatDocument1 pagePeople v. MagatRidzanna AbdulgafurPas encore d'évaluation

- People vs. OlvisDocument11 pagesPeople vs. OlvisbreeH20Pas encore d'évaluation

- 2Sps. Sabitsana vs. Muertegui DigestDocument2 pages2Sps. Sabitsana vs. Muertegui DigestEnrique BentoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Civil Procedure Outline: Abernathy, Fall 2015 I. Phases of Litigation Pleadings: Complaint (Class 3 or 9/4)Document48 pagesCivil Procedure Outline: Abernathy, Fall 2015 I. Phases of Litigation Pleadings: Complaint (Class 3 or 9/4)Lauren MikePas encore d'évaluation

- Seamster BondDocument2 pagesSeamster Bondaswarren77Pas encore d'évaluation

- Muscogee Indictment1Document6 pagesMuscogee Indictment1Jessie GarciaPas encore d'évaluation

- Javier v. SandiganbayanDocument3 pagesJavier v. SandiganbayanTeff QuibodPas encore d'évaluation

- Pennoyer v. Neff 95 U.S. 714 Rule:: SyllabusDocument11 pagesPennoyer v. Neff 95 U.S. 714 Rule:: SyllabusShaiPas encore d'évaluation

- Adonis v. TesoroDocument2 pagesAdonis v. TesoroAntonJohnVincentFriasPas encore d'évaluation

- Same Evidence Test RuleDocument1 pageSame Evidence Test RuleMichelle Joy ItablePas encore d'évaluation

- Index of Authorities: LegislationDocument4 pagesIndex of Authorities: LegislationSwarnimaPas encore d'évaluation

- Zabavsky DismissalDocument38 pagesZabavsky DismissalMartin AustermuhlePas encore d'évaluation

- Ejectment 07Document5 pagesEjectment 07Richard TenorioPas encore d'évaluation

- Digest PP vs. UBIÑADocument1 pageDigest PP vs. UBIÑAStef OcsalevPas encore d'évaluation

- The Art of Fact Investigation: Creative Thinking in the Age of Information OverloadD'EverandThe Art of Fact Investigation: Creative Thinking in the Age of Information OverloadÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (2)

- Litigation Story: How to Survive and Thrive Through the Litigation ProcessD'EverandLitigation Story: How to Survive and Thrive Through the Litigation ProcessÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- Courage to Stand: Mastering Trial Strategies and Techniques in the CourtroomD'EverandCourage to Stand: Mastering Trial Strategies and Techniques in the CourtroomPas encore d'évaluation

- Winning with Financial Damages Experts: A Guide for LitigatorsD'EverandWinning with Financial Damages Experts: A Guide for LitigatorsPas encore d'évaluation

- Greed on Trial: Doctors and Patients Unite to Fight Big InsuranceD'EverandGreed on Trial: Doctors and Patients Unite to Fight Big InsurancePas encore d'évaluation

- Busted!: Drug War Survival Skills and True Dope DD'EverandBusted!: Drug War Survival Skills and True Dope DÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (7)

- 2017 Commercial & Industrial Common Interest Development ActD'Everand2017 Commercial & Industrial Common Interest Development ActPas encore d'évaluation