Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Journal New

Transféré par

1983gonzoCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Journal New

Transféré par

1983gonzoDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Self-evaluations of the stream of thought in

journal writing

James L. Myers*

Applied English Department, Ming Chuan University, Taoyuan, Taiwan

Received 1 March 2001; accepted 8 August 2001

Abstract

William James theoretical model of consciousness known as the stream of thought has

been applied in this study as an impetus for English as a foreign language learners self-

reections on the purpose of journal writing. They evaluated their thought processes by fol-

lowing a guided questionnaire designed to elicit thought patterns based on James concept.

After having written their journals over a 3-month period, students were able to trace their

strengths and weaknesses and describe their own learning patterns and needs in regard to

learning how to write in English for both personal expression and academic writing. Through

an analysis of their reections, certain general patterns emerged in relation to vocabulary

acquisition, organizational strategies, invention, personal expression, and thought. These

patterns are described as well as examples of individual variation regarding students con-

scious awareness of their writing processes. # 2001 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Student journals; Consciousness; Meta-cognitive learning; Academic writing; Psychology and

language learning

1. Introduction

This paper applies aspects of Jamess (1950/1890) famous theory of the stream of

thought, to journal writing. It takes a case study approach to delineate individual

dierences by focusing on 15 students writing processes. By using James model of

consciousness as a heuristic for Taiwanese students self-ruminations while writing

System 29 (2001) 481488

www.elsevier.com/locate/system

0346-251X/01/$ - see front matter # 2001 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved.

PI I : S0346- 251X( 01) 00037- 9

* Present address: 1, 6th oor, Alley 7, Lane 50, Chien Kuo Road, Pateh Hsih, Taoyaun Hsien, Tai-

wan, ROC. Fax: +886-3-3651583.

E-mail address: jmyers@ms10.hinet.net (J.L. Myers).

their journals, I hoped to discover to what degree self-reection about their journal

writing also inuenced their writing for academic purposes. My interest in this was

partially motivated by a study by Leki and Carson (1994). Undergraduates reported

that English for Academic Purposes (EAP) courses do not prepare them well for

writing in other disciplines besides English. A popular activity in such courses is

journal writing. Hence, Leki and Carson question its appropriateness in preparing

students to write in EAP courses (p. 96). However, this paper contends, as EAP

writing courses cannot meet every students needs, journal writing can be an eective

method for them to independently discover and develop their individual academic

interests and their EAP writing capacities. Thus, this study applies a theoretical

model of consciousness in order to see to if it can be practically benecial in

improving EFL students journal writing and also examines the academic value of

journal writing itself in EFL composition classes.

Prior to being capable of academic writing, EFL students must also be able to

develop such skills as invention and organization. I wondered if journal writing

could aid students in acquiring these abilities. What patterns might emerge from

their self-reections in terms of reoccurring images and topics that demonstrated an

enhancement and increased awareness of logical organization and inventiveness in

essay writing?

Journals or diaries can be used as introspective tools, but as Bailey has contended

(1990, p. 224), to acquire maximum benets, writers should re-read the entries and

attempt to locate the patterns in their writing. Moreover, as Halbach (2000) con-

cludes in a case study of learning strategies in diary writing, weaker students lack the

strategies of self-evaluation while more successful students are able to make full use

of a wide range of resources and re-enforce their learning with follow-up activities

(2000, p. 93). Therefore, I wondered to what extent re-reading journals helped indi-

vidual students, especially weaker ones, to clarify and realize their language learning

objectives.

2. Writing, self-reection, and the stream of thought

Even though James wrote Chapter IX The Stream of Thought in his Principles

of Psychology in the nineteenth century, many modern researchers probing into the

nature of consciousness such as Baars (1997), Natsoulas (1997) and Singer (1998)

view it as one of the most signicant and inuential models of consciousness. As

Singer (1975, p. 32) points out, much great literature has been established on interior

monologues taken from streams of thoughts. Twentieth century writers such as

Proust, Kerouac, and Joyce come readily to mind.

James described the stream of thought as having ve characteristics: (1) every

thought is a part of an individuals consciousness; (2) each thought is always

changing; (3) each is sensibly continuous; (4) every thought is directed toward

objects outside itself; (5) and thought discriminates among those objects, including

some while rejecting others (James, p. 225). James also sees the stream of thought as

developmental in that a baby does not have one and even lacks a pure principle of

482 J.L. Myers / System 29 (2001) 481488

subjectivity. . .(but certainly needs a stream of thought) to make him sensible at all to

anything, to make him discriminate. (James, 1950/1890, p. 321). Of course, the

stream of thought is a metaphor of consciousness which not everyone may agree

with, but James uses such a metaphor to emphasize that thought processes happen

so rapidly that by the time one can report them they have disappeared. Most likely,

everyone can agree that describing ones experiences completely in words is virtually

impossible. Thus, introspection must also involve retrospection to truly capture the

most signicant aspects of ones own experiences. In journal writing, a re-reading of

their journals may provide most students, who take such an activity seriously, with

both a retrospective and introspective perspective on their writing.

As Vygotsky (1999/1934) contends, thought and speech are the essence of human

consciousness and writing is speech in thought and image (p. 181). If this is the case,

it appears then that writing can be a means by which a person can understand and

rene her personal language development, especially by studying her own writing

and seeing within it a reection of her attitude toward learning and experience as

seen in her recorded thoughts at dierent periods of time.

3. Method

3.1. The population and setting

In this study, 15 Mandarin-speaking Taiwanese students were randomly selected

from two second-year university composition classes for Applied English majors at

Ming Chuan University in Taiwan. The classes had a total of 68 students. Most

of the students lived o-campus, near the university. Their ages ranged from 19 to

25 years. Three of the 15 students were males and 12 were females. These ratios

reected the preponderance of females at Ming Chuan and in the Applied English

Department. Their English ability was at an intermediate level; the writing class was

a required subject for their major and was intended to teach them practical and

academic writing skills. The department oered specialized Applied English courses

in three career tracks: teaching, business, and tourism.

3.2. Procedures

The students had the assignment of writing journals for 3 months, three times

per week. Although not every student in the class managed to faithfully write

three entries per week, the 15 random selections in this study fell into a range of 30

34 entries over the 3-month period. I told the class that their grade would be based

on quantity, coherence, and interesting content rather than on grammar. They had

the option of choosing from a list of 50 topics which allowed them to practise such

invention skills as comparison and contrast and persuasion or to indulge in guided

fantasies. They also had the option of writing about anything that they wished to

write about. They exchanged journals once during the semester with a student of

their choice in order to increase the communicative aspect of the activity and to

J.L. Myers / System 29 (2001) 481488 483

expand their audience to not just themselves and the instructor but to other students

as well. This aspect of the study was inuenced by Cole, Raer, Rogan, and

Schleicher (1998) and Huangs (2000) research into journal exchanges. Two weeks

prior to the nal collection of their journals I gave them a set of self-evaluation

questions based on James stream of thought, which they were to respond to in their

journals as three entries.

A month later, after I had collected, graded and returned their journals I asked

them to nd a partner and interview each other about their self-evaluations and then

re-write them in class. Thus, they had two opportunities to write their reections

about their stream of thought in their writing.

3.3. The guided self-evaluation questionnaire and its underlying rationale

The rst entry consisted of two sets of questions. The rst set asked: Since you

began writing your journal, how have you changed as a writer? Have you personally

changed in any way in the past few months as seen in your writing? If so, how? As

James observes, our thoughts continue to change along with our life experiences and

as Heraclitus long ago noted, we never step down into the same stream twice (James,

1950/1890, p. 233). Thus, I wanted to see to what extent students looked back at

their experiences and their writing in a fresh light. The second set of questions asked:

As you re-read your journal, do you see any topics or images that re-occur? What are

they? Why do you think they re-occur? In asking about topics that reoccur I was

considering the process of invention. As James notes, as we voluntarily engage in

thinking, our thoughts sometimes revolve around a particular topic and sometimes

it involves some unresolved problem. Images may arise that relate to solving the

problem (James, 1950/1890, p. 259).

The second entry also asked two sets of questions. The rst set included: As you

have been writing have you had a purpose or have you been writing whatever you feel?

If you had a purpose, what was it? James sees the stream of thought as made up

sometimes of strands of imagery which wander around such as in reverie or day-

dreaming, but most of the time our ideas are guided by a purpose which we always

return to even if our thoughts may occasionally drift away onto other trajectories. I

wondered if the students were able to see their own goals more clearly through such

meta-cognitive questioning. The second set of questions asked: Do you have any

words or sentences that you often repeat in your writing? Why do you repeat them do

you think? I asked these questions to see how students used repetition in their writ-

ing. Repetition can be used to establish rhythm or for emphasis; on the other hand,

it might be used because of a lack of sucient vocabulary. James observed that

rhythms are an important ingredient in our consciousness and are characterized by

such repeated phenomena as breathing, pulse, heart-beats, and word or sentence

fragments that pass by in our imaginations (James, 1950/1890, p. 620). By noting

reoccurring words I might be able to discover what the students were thinking about

most when they were writing.

The third entry also asked two sets of questions. The rst set of questions asked:

Do you think the content of your journal has a lot of variety? Why or why not? I asked

484 J.L. Myers / System 29 (2001) 481488

these questions on the premise that an interesting journal should describe a variety

of events or topics. Also, by asking themselves these questions students could

evaluate to what extent they were actually observing their own experiences or

environment or developing ideas and attempting to depict them in their journals. As

James says, many objects, events, changes, many subdivisions, immediately widen

the view as we look back. Emptiness, monotony, familiarity make it shrivel up.

(James, 1950/1890, p. 624).

The nal question was: What do you think you can learn from writing a journal?

From this, I hoped the students might provide an overall assessment of themselves

or reveal some new aspect to the process.

3.4. A discussion of the responses to the questionnaire

The students responses indicate a great deal of individual variation in their writ-

ing processes. I have identied each student by a letter A through O and analyzed

the self-monitoring of each ones (1) language use, (2) rhetorical organization (3)

invention; (4) the role of their thoughts and (5) emotions in regard to their experi-

ences as writers and learners by seeking statements that reected these items in their

self-evaluations. I derived these ve points inductively by means of an analysis of the

patterns, which emerged from the students replies. I was also informed by informal

interviews that I held with several students. Moreover, as the students exchanged

journals with each other once during the semester and wrote down their reactions to

each others journals, I have also interpreted these responses in regard to the ve

categories above.

In terms of language use, the most outstanding concern was with vocabulary.

Eight of the 15 students in this study directly expressed or suggested that a lack of

vocabulary was a problem while writing. Six of these eight stated that they simply

repeated the same words over and over because of this lack of vocabulary. In terms

of individual variation, student C reported that she strove for variety and deleted

entries where she was being redundant. Student F stated that in certain cases she

repeated certain words for emphasis and not because they were redundant, but in

other cases it was because of a vocabulary deciency. Student B stated that she had

had no vocabulary improvement and her English vocabulary had been deteriorating

since she had entered the university and she only wrote supercially about topics.

Two of these eight students also mentioned that journal writing was a good way to

improve their vocabulary, as did an additional two students who otherwise did not

state that a lack of vocabulary was a problem. Additionally, in terms of language

use, two students showed a concern for grammar and wanted more feedback about

their grammar errors. Thus, vocabulary and to a lesser extent grammar, were their

two main concerns about language use.

In terms of organizational strategies, 11 students stated or suggested that journal

writing was a way of improving their organizational skills in general.

Eight students discussed invention strategies which also seemed to contain pos-

sibilities toward enhancing their academic writing. Student I, for example, used

mind-maps before she wrote about a topic in her journal and felt that she had

J.L. Myers / System 29 (2001) 481488 485

improved her organizational skills and generated ideas with this strategy. Student L

imagined herself as a popular writer who interacted with her readers and that they

gave her suggestions as to what to write about; student N took a problem solving

attitude toward dierent topics; she also found it fascinating to look up infor-

mation that could support her viewpoint; students G and K also found that journal

writings provided the impetus to research and read about various topics before

writing; student O drew from her past childhood experiences to write her journal;

student E compared the dierence between free-writing and structured writing and

preferred structured writing such as writing a topic sentence, supporting sentences,

and a conclusion which he thought was easier than free-writing. Student E also

observed that journal writing helped his observational skills and he felt that this led

him to have more ideas. Several more students felt that they noticed things more

than before; such as student H, and the above mentioned L and K.

Thirteen students directly referred to how journal writing inuenced their

thoughts or cognitive skills. For example, both students H and K stated that not

only had they become more observant but also wrote in more detail than before.

Students H, F, and G, stated that they often repeated the words, I think. Student

H wrote that she repeated these words because she had a purpose behind her writ-

ing: to collect her thoughts. Student F wrote that she repeated I think along with

so and added that she had become more independent in her thinking. Student G

emphasized that the journal made her realize the importance of thinking and she

strove for variety and tried to avoid cliche s. Student I repeated although and

she thought she did this because everything has two sides. Student J wrote that she

had begun to think more before she wrote and did this to avoid making mistakes.

Student L stated somewhat paradoxically that her sensitivity to the environment had

increased, but at that the same time she was unable to really see any change in her

writing because she just wrote about her thoughts. Also in relation to the cognitive

aspects of journal writing, Students A and E saw their journals as aids for memory.

Moreover, Student B wrote how sometimes something that happened led her to

connect things and she wrote it down. Almost all of the students stressed that

thinking was an important aspect of their writing processes. Journal writing was an

impetus for thinking about themselves, their learning processes, current events, their

interests, social life, and environment.

Ten students discussed matters of an emotional or aective nature which emerged

in their journals. Often they were reoccurring topics which dealt with their social life,

family, or childhood. Student O, for example, noted that she wrote frequently about

her feelings concerning these three aspects of her life. She also personally felt that she

had become a more energetic person during the 3-month period of her life while

she was writing the journal. Student O also wrote about her childhood and her

relationships with others. Student A expressed her feelings and moods and said she

loved doing this. Student E wrote frequently about the news and music which were

his interests. Student G wrote about her mothers laugh, country trees and owers.

Not all factors were positive, student L wrote that she lacked self-condence, and

this is where she recognized that she needed to make improvements. These are a few

examples of aective factors the students saw in their writing.

486 J.L. Myers / System 29 (2001) 481488

After performing this analysis, I asked another experienced EFL teacher to

evaluate the 15 students. I did not tell her the nature of my research questions, but

requested that she try to nd ve patterns in the writings. Her categories did not

completely match mine, but what she provided conrmed most of my observations.

Three patterns corresponded almost identically with mine; that is, the components

that dealt with emotions, thoughts, and organization. With regard to these cat-

egories, she saw that some students preferred to develop topics rather that write

emotionally whereas other preferred to be more personally expressive. The two

other patterns she observed were that the responses contained students reections

of past experience and this especially provided an aid to memory; and they self-

evaluated their own learning strategies to determine their learning needs. She saw

four types of writers emerging from the journals: historical; rational; metacognitive;

and emotional. Some writers possessed a combination of these characteristics and

others were purely of one type.

3.5. Journal exchange

In addition, six of the 15 students in this study commented on the journal

exchange and had positive comments about its value. For example, one commented

that she learned from the other students mistakes; another said she learned to

improve her study habits and to seek out ideas from various sources as her exchange

partner had done; another student analyzed the other students journal for simi-

larities and contrasts with her writing; yet another student appreciated the encour-

agement which she received from her exchange partner.

4. Conclusion

These results suggest that students reections induced by a Jamesian model of the

stream of thought, involved students in an increased self-monitoring of their

writing skills which led them to increased insights into their strengths and weak-

nesses as writers. Several patterns emerged. Many of the students became especially

aware of their vocabulary deciencies and the need to strengthen their vocabulary

through increased reading and writing. Journal writing also provided opportunities

for the development of their own individual invention strategies, and several stu-

dents saw factual knowledge as the basis and jumping o point to further creativ-

ity and discovery. This suggests that journal writing contributes to academic writing

and can be used for discovery, research, and data collection directed toward future

essay writing in which students develop and rene essays around topics that interest

them which they have already initially explored in their journals. Moreover, in the

aective realm, many students felt comfortable expressing their feelings in the non-

threatening way which journal writing provided.

Signicantly, for most students, a reoccurring theme that they recognized in their

writing involved thinking itself. Many of them saw themselves as improved thinkers

and saw a connection between thinking and writing. Perhaps Vygotsky made an apt

J.L. Myers / System 29 (2001) 481488 487

point when he wrote, Experience teaches us that thought does not express itself in

words, but realizes itself in them (Vygotsky, 1999/1934, p. 251).

Self-knowledge through journal writing can be accomplished by allowing students

to structure and write their journals in their individual ways, thus fostering creativity

rst, and teachers might suggest revision through self-questioning and re-reading of

their journals later as done in this study, so that learners can fully appreciate the

advances they have made and the deciencies they still need to correct. Also, this

process allows the students a greater measure of autonomy as they learn to make

their own connections to research and personal experience.

References

Baars, J.B., 1997. In the Theater of Consciousness: The Workplace of the Mind. Oxford University Press,

New York.

Baily, K.M., 1990. The use of dairy studies in teacher education programs. In: Richard, J.C., Nunan, D.

(Eds.), Second Language Teacher Education. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 215226.

Cole, R., Raer, L.M., Rogan, P., Schleicher, L., 1998. Interactive group journals: learning as a dialogue

among learners. TESOL Quarterly 32 (3), 556567.

Halbach, A., 2000. Finding out about students learning strategies by looking at the diaries: a case study.

System 28, 8596.

Huang, J.Y., 2000. Eective journal writing: a pilot study. In: Huang, T., Katchen, J., Dai, W., Leung, Y.

(Eds.), Selected Papers from the Ninth International Symposium on English Teaching. Crane Publish-

ing, Taipei, pp. 348358.

Natsoulas, T. 1997-1998. The stream of consciousness: XV. James in recent context (19811986). In:

Pope, K.S., Singer, J.L. (Eds.), Imagination, Cognition and Personality. Vol. 17 (2) pp. 123140.

James, W., 1950. The Principles of Psychology, Vol. 1. Dover, New York. (First published in 1890).

Leki, I., Carson, J., 1994. Students perceptions of EAP writing instruction and writing needs across the

disciplines. TESOL Quarterly 28 (1), 81101.

Singer, J.L., 1975. The Inner World of Daydreaming. Harper and Row, New York.

Singer, J.L., 1998. Daydreams, the stream of consciousness, and self-representations. In: Bornstein, R.F.,

Masling, J.M. (Eds.), Empirical Perspectives on the Psychoanalytic Unconscious. American Psycho-

logical Association, Washington DC, pp. 141186.

Vygotsky, L., 1999. Thought and Language. The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. (Original work published

in 1934).

488 J.L. Myers / System 29 (2001) 481488

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Okinawan Shorei-Kempo Karate Shawano Dojo Class MaterialsDocument14 pagesOkinawan Shorei-Kempo Karate Shawano Dojo Class Materials1983gonzo100% (1)

- Free Dont Wear Your Gi To The Bar ArtechokepdfDocument164 pagesFree Dont Wear Your Gi To The Bar Artechokepdf1983gonzo100% (1)

- Turbine Start-Up SOPDocument17 pagesTurbine Start-Up SOPCo-gen ManagerPas encore d'évaluation

- A New Writing Classroom: Listening, Motivation, and Habits of MindD'EverandA New Writing Classroom: Listening, Motivation, and Habits of MindPas encore d'évaluation

- The Politics of Inner Power: The Practice of Pencak SilatDocument338 pagesThe Politics of Inner Power: The Practice of Pencak Silat1983gonzo100% (4)

- Teaching Writing Through Genre-Based Approach PDFDocument16 pagesTeaching Writing Through Genre-Based Approach PDFPutri Shavira RamadhaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Skirmishes Graham Harman PDFDocument383 pagesSkirmishes Graham Harman PDFparaiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Teaching Literature & Writing in the Secondary School ClassroomD'EverandTeaching Literature & Writing in the Secondary School ClassroomPas encore d'évaluation

- Assignments across the Curriculum: A National Study of College WritingD'EverandAssignments across the Curriculum: A National Study of College WritingÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1)

- GP 09-04-01Document31 pagesGP 09-04-01Anbarasan Perumal100% (1)

- Student's Expository WritingDocument7 pagesStudent's Expository WritingKeziaPas encore d'évaluation

- Writing Theories and Writing PedagogiesDocument20 pagesWriting Theories and Writing PedagogiesDanh VuPas encore d'évaluation

- Allwright 1983Document195 pagesAllwright 1983academiadeojosazulesPas encore d'évaluation

- Approaches To Teaching Second Language WritingDocument5 pagesApproaches To Teaching Second Language WritingJuraidah Nadiah RahmatPas encore d'évaluation

- DLL Drafting 7Document4 pagesDLL Drafting 7Ram Dacz100% (3)

- Application of Discourse Analysis in College Reading ClassDocument29 pagesApplication of Discourse Analysis in College Reading Classmahmoudsami100% (1)

- Book Reported "Teaching and Researching Writing Ken Hyland Second Edition Page "Document29 pagesBook Reported "Teaching and Researching Writing Ken Hyland Second Edition Page "andini gita hermawanPas encore d'évaluation

- Writing and Teaching Writing: Learning OutcomesDocument19 pagesWriting and Teaching Writing: Learning OutcomesEsther Ponmalar CharlesPas encore d'évaluation

- Teaching LiteratureDocument8 pagesTeaching LiteratureFlorina Kiss89% (9)

- Genre-Based Writing InstructionDocument16 pagesGenre-Based Writing Instructionmalik amanullahPas encore d'évaluation

- Smagorinsky Personal NarrativesDocument37 pagesSmagorinsky Personal NarrativesBlanca Edith Lopez CabreraPas encore d'évaluation

- Focused and CtiticalDocument15 pagesFocused and Ctiticalnero daunaxilPas encore d'évaluation

- Draft Proposal For Dissertation UpdatedDocument17 pagesDraft Proposal For Dissertation UpdatedPriest is My slavePas encore d'évaluation

- Bab 1Document5 pagesBab 1Willy SuryaPas encore d'évaluation

- Sites of Invention Genre and The Enactment of First-Year Writing Outline - Sofia ADocument5 pagesSites of Invention Genre and The Enactment of First-Year Writing Outline - Sofia Aapi-710656920Pas encore d'évaluation

- Seconda Language Learning Theoretical FoundationsDocument4 pagesSeconda Language Learning Theoretical FoundationsforscribforscribPas encore d'évaluation

- Text PDFDocument79 pagesText PDFMohammed MansorPas encore d'évaluation

- Engaging Literary Competence Through Critical Literacy in An EFL SettingDocument4 pagesEngaging Literary Competence Through Critical Literacy in An EFL SettingCyril FalculanPas encore d'évaluation

- Beittel 2002Document4 pagesBeittel 2002Agustin PellegrinettiPas encore d'évaluation

- A GenreDocument9 pagesA GenreThu HuệPas encore d'évaluation

- MegcasDocument37 pagesMegcasMeg StraussPas encore d'évaluation

- Autonomy and HedgingDocument7 pagesAutonomy and HedgingSMBPas encore d'évaluation

- The Esl Student and The Revision Process: Some Insights From Schema TheoryDocument12 pagesThe Esl Student and The Revision Process: Some Insights From Schema TheoryرونقالحياةPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 4 - Discourse and GenreDocument5 pagesChapter 4 - Discourse and GenreRocio A RuartePas encore d'évaluation

- Beyond "Is This OK?": High School Writers Building Understandings of GenreDocument10 pagesBeyond "Is This OK?": High School Writers Building Understandings of Genreapi-297629759Pas encore d'évaluation

- Communicative Purpose in Student Genres: Evidence From Authors and TextsDocument13 pagesCommunicative Purpose in Student Genres: Evidence From Authors and Textshello yaPas encore d'évaluation

- Research Article 2Document21 pagesResearch Article 2api-371673914Pas encore d'évaluation

- An Overview of Writing Theory and Research: From Cognitive To Social-Cognitive View Lucy Chung-Kuen YaoDocument20 pagesAn Overview of Writing Theory and Research: From Cognitive To Social-Cognitive View Lucy Chung-Kuen YaoMiko BosangitPas encore d'évaluation

- Improving Reading Attitudes of College StudentsDocument9 pagesImproving Reading Attitudes of College StudentsMarelie GarciaPas encore d'évaluation

- Interweaving Conceptual and Substantial Problems of Writing Instruction: Socio Reflective On Exploring Hortatory and Analytical ExpositionDocument15 pagesInterweaving Conceptual and Substantial Problems of Writing Instruction: Socio Reflective On Exploring Hortatory and Analytical ExpositionAntonius Riski Yuliando SesePas encore d'évaluation

- Student's Expository WritingDocument7 pagesStudent's Expository WritingGewazano Kezia PareraPas encore d'évaluation

- Running Head: Annotated Bibliographies 1Document5 pagesRunning Head: Annotated Bibliographies 1Ramon Alberto Santos ReconcoPas encore d'évaluation

- Ed 208411Document37 pagesEd 208411janice MAGTOTOPas encore d'évaluation

- Teaching Writing Through LiteratureDocument9 pagesTeaching Writing Through LiteratureSamori CamaraPas encore d'évaluation

- Students of Low Proficiency May Encounter Some Problems While WritingDocument4 pagesStudents of Low Proficiency May Encounter Some Problems While WritingJannat Tupu100% (1)

- Student Research N WritingDocument10 pagesStudent Research N WritingLia NA Services TradingPas encore d'évaluation

- Annotated Bibliography: Science Scope, Biography in ContextDocument4 pagesAnnotated Bibliography: Science Scope, Biography in Contextapi-339109791Pas encore d'évaluation

- English Language CompDocument10 pagesEnglish Language Compapi-237174033Pas encore d'évaluation

- Teaching and Researching WritingDocument4 pagesTeaching and Researching WritingcookinglikePas encore d'évaluation

- In The Following Pages You Will Be Able To See The Different Example of Each Six General Classifications of Academic TextsDocument27 pagesIn The Following Pages You Will Be Able To See The Different Example of Each Six General Classifications of Academic TextsGarcia Khristine Monique BadongPas encore d'évaluation

- Integrating Reading and Writing For Effective Language TeachingDocument5 pagesIntegrating Reading and Writing For Effective Language TeachingurielPas encore d'évaluation

- ReadingsDocument95 pagesReadingsAne LarraPas encore d'évaluation

- Discourse Analysis: The Questions Discourse Analysts Ask and How They Answer ThemDocument3 pagesDiscourse Analysis: The Questions Discourse Analysts Ask and How They Answer Themabida bibiPas encore d'évaluation

- Literary Media Theory Adapted To ImproveDocument222 pagesLiterary Media Theory Adapted To ImprovealinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Academic Writing HandoutDocument5 pagesAcademic Writing Handoutkhaela tendidoPas encore d'évaluation

- Learning Activities in Studying LiteratuDocument8 pagesLearning Activities in Studying LiteratuYến Nguyễn Thị KimPas encore d'évaluation

- Writing Theories and Writing Pedagogies: January 2008Document20 pagesWriting Theories and Writing Pedagogies: January 2008Razif Ismaiel SoulflyPas encore d'évaluation

- 11337397n7p208 PDFDocument3 pages11337397n7p208 PDFel adha ilhamPas encore d'évaluation

- Reader Response and OdysseyDocument18 pagesReader Response and OdysseySer PanosPas encore d'évaluation

- Rws Discourse Community EssayDocument9 pagesRws Discourse Community Essayapi-385793077Pas encore d'évaluation

- Wesley - LearnerAttitudes, Perceptions, Andbeliefs inLangLearningDocument21 pagesWesley - LearnerAttitudes, Perceptions, Andbeliefs inLangLearningHồ Thị Thùy Dung THCS&THPT U Minh Thượng - Kiên GiangPas encore d'évaluation

- Ockerstrom 2007 Positive Expectations - A Reflective Tale On The Teaching of WritingDocument7 pagesOckerstrom 2007 Positive Expectations - A Reflective Tale On The Teaching of WritinghooriePas encore d'évaluation

- Final Research PaperDocument24 pagesFinal Research Paperapi-602041021Pas encore d'évaluation

- Article Review - Writing As Linguistic Mastery - The Development of Genre Based PedagogyDocument9 pagesArticle Review - Writing As Linguistic Mastery - The Development of Genre Based PedagogyNicoSuryadiPas encore d'évaluation

- 0a6cc6e66500 PDFDocument13 pages0a6cc6e66500 PDFKritika RamchurnPas encore d'évaluation

- Choose A Topic: IntroduceDocument5 pagesChoose A Topic: IntroduceAyra YayenPas encore d'évaluation

- SLM Q1 English For Academic and Professional Purpose CompleteDocument32 pagesSLM Q1 English For Academic and Professional Purpose Completexuxa meg palomaresPas encore d'évaluation

- Georgopoulou and Griva-2Document7 pagesGeorgopoulou and Griva-21983gonzoPas encore d'évaluation

- Journal of Research and PracticeDocument188 pagesJournal of Research and Practice1983gonzoPas encore d'évaluation

- Parents - 2Document146 pagesParents - 21983gonzoPas encore d'évaluation

- Swot Matrix Strengths WeaknessesDocument6 pagesSwot Matrix Strengths Weaknessestaehyung trash100% (1)

- Group 4 - When Technology and Humanity CrossDocument32 pagesGroup 4 - When Technology and Humanity CrossJaen NajarPas encore d'évaluation

- Kowalkowskietal 2023 Digital Service Innovationin B2 BDocument48 pagesKowalkowskietal 2023 Digital Service Innovationin B2 BAdolf DasslerPas encore d'évaluation

- CadburyDocument21 pagesCadburyramyarayeePas encore d'évaluation

- Namagunga Primary Boarding School: Primary Six Holiday Work 2021 EnglishDocument10 pagesNamagunga Primary Boarding School: Primary Six Holiday Work 2021 EnglishMonydit santinoPas encore d'évaluation

- Evidence MODULE 1 Evidence DefinitionDocument8 pagesEvidence MODULE 1 Evidence Definitiondave BarretoPas encore d'évaluation

- Hydrology Report at CH-9+491Document3 pagesHydrology Report at CH-9+491juliyet strucPas encore d'évaluation

- Topic 3 Intellectual RevolutionDocument20 pagesTopic 3 Intellectual RevolutionOlive April TampipiPas encore d'évaluation

- Comparative Study On Analysis of Plain and RC Beam Using AbaqusDocument9 pagesComparative Study On Analysis of Plain and RC Beam Using Abaqussaifal hameedPas encore d'évaluation

- Dissertation MA History PeterRyanDocument52 pagesDissertation MA History PeterRyanePas encore d'évaluation

- Analysis Chart - Julie Taymor-ArticleDocument3 pagesAnalysis Chart - Julie Taymor-ArticlePATRICIO PALENCIAPas encore d'évaluation

- JVC tm1010pnDocument4 pagesJVC tm1010pnPer VigiloPas encore d'évaluation

- A New Procedure For Generalized Star Modeling Using Iacm ApproachDocument15 pagesA New Procedure For Generalized Star Modeling Using Iacm ApproachEdom LazarPas encore d'évaluation

- Sop GC6890 MS5973Document11 pagesSop GC6890 MS5973Felipe AndrinoPas encore d'évaluation

- n4 HandoutDocument2 pagesn4 HandoutFizzerPas encore d'évaluation

- Lennox IcomfortTouch ManualDocument39 pagesLennox IcomfortTouch ManualMuhammid Zahid AttariPas encore d'évaluation

- KSP Solutibilty Practice ProblemsDocument22 pagesKSP Solutibilty Practice ProblemsRohan BhatiaPas encore d'évaluation

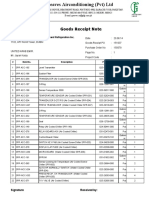

- Goods Receipt Note: Johnson Controls Air Conditioning and Refrigeration Inc. (YORK) DateDocument4 pagesGoods Receipt Note: Johnson Controls Air Conditioning and Refrigeration Inc. (YORK) DateSaad PathanPas encore d'évaluation

- Problems: C D y XDocument7 pagesProblems: C D y XBanana QPas encore d'évaluation

- Control System PPT DO1Document11 pagesControl System PPT DO1Luis AndersonPas encore d'évaluation

- UntitledDocument5 pagesUntitledapril montejoPas encore d'évaluation

- WicDocument6 pagesWicGonzalo Humberto RojasPas encore d'évaluation

- Why We Need A Flying Amphibious Car 1. CarsDocument20 pagesWhy We Need A Flying Amphibious Car 1. CarsAsim AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- Practice Test - Math As A Language - MATHEMATICS IN THE MODERN WORLDDocument8 pagesPractice Test - Math As A Language - MATHEMATICS IN THE MODERN WORLDMarc Stanley YaoPas encore d'évaluation

- Afa Coursework ExamplesDocument6 pagesAfa Coursework Examplesiuhvgsvcf100% (2)