Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Hours, Flexibility, and The Gender Gap in Pay

Transféré par

Center for American Progress100%(1)100% ont trouvé ce document utile (1 vote)

96 vues3 pagesThere is a large hourly wage penalty associated with working fewer hours per week. While the effect is similar by gender, because women are more likely to work fewer than 40 hours per week, they experience the wage penalty more often.

Titre original

Hours, Flexibility, and the Gender Gap in Pay

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentThere is a large hourly wage penalty associated with working fewer hours per week. While the effect is similar by gender, because women are more likely to work fewer than 40 hours per week, they experience the wage penalty more often.

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

100%(1)100% ont trouvé ce document utile (1 vote)

96 vues3 pagesHours, Flexibility, and The Gender Gap in Pay

Transféré par

Center for American ProgressThere is a large hourly wage penalty associated with working fewer hours per week. While the effect is similar by gender, because women are more likely to work fewer than 40 hours per week, they experience the wage penalty more often.

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 3

1 Center for American Progress | Hours, Flexibility, and the Gender Gap in Pay

Hours, Flexibility, and

the Gender Gap in Pay

By Claudia Goldin June 20, 2014

Introduction and summary

Te issues facing workers and their families are currently in the spotlight. Te gender

wage gap, minimum wage, and expansions of paid leave have all been the subjects of

media atention and increasing political action. As part of the conversation about the

need to update the nations labor standards, considerable atention is focused on the

working hours and scheduling of lower-wage workers, particularly hourly workers.

Te weak labor market of the past several years has exacerbated the problem; employees

ofen struggle with fewer hours than desired and unpredictable hours. Some of these

trends are increasing with the growing use of just-in-time scheduling sofware, which

allows employers and managers to adjust stafng levels throughout the course of a busi-

ness day. In retail sales, where demand varies with weather conditions, this sofware has

led workers to experience less predictable and more unstable schedules. Some workers

in retail sales have been asked to appear with litle noticeknown as on-call shifs

while others may be sent home during slow periods only to be called back in later.

1

Te

inability of workers to have foreseeable schedules imposes hardships that are especially

severe for parentsparticularly mothersas well as for students and dual-job employ-

ees. Many would like to work part time to accommodate family and student life, but

unpredictable scheduling reduces the ability to work even part time. Others are unable

to work more hours when they want.

However, the problems facing those who work fewer than 40 hours per week and those

with variable schedules go beyond the logistical issues associated with not having reli-

able work hours. Workers with low to moderate incomes are more likely to be paid on an

hourly basis than they are to receive a fxed salary. Wages are higher for nonhourly workers

than they are for hourly workers, even for the same occupations, primarily because non-

hourly workers have supervisory responsibilities and labor more hours per week.

2 Center for American Progress | Hours, Flexibility, and the Gender Gap in Pay

If all equally productive workers were paid the same on an hourly basis for identical

workindependent of the number and timing of hours workeddiferences in pay,

paid as or calculated as an hourly rate, would disappear. Women, far more so than men,

ofen work fewer hours at some point in their lives. During those periods in their life

cycle, some prefer to work specifc hours, including students who cannot work dur-

ing class and parents who must be home to care for children, even if they work regular

or long hours. Furthermore, many prefer to work predictable hours rather than being

on call or working at the whim of an employer even if they work 40 hours or more per

week. Many of these considerations regarding the temporality of work are harder to

measure empirically than the number of hours. Due to data limitations, the need to

work particular hours cannot be directly considered in the calculations for this report,

but it will loom large in the background.

Tis report begins with a summary of research on the role of hours in determining earn-

ings at the higher end of the income distribution. More hours of work in some of the

higher-income occupations are associated with signifcantly greater earnings per hour.

Te relationship is strongest in the business, fnance, and legal felds. Advances in infor-

mation technology and various organizational changes in certain sectors have weakened

the relationship between hours worked and earnings per hour. Tese technological

changes have increased the ability of employees to hand of clients, customers, and

patients with litle loss in efciency and have made employees beter substitutes for each

other. What this change implies is that an individual working 50 hours per week is no

longer worth much more than twice what two 25-hour-per-week workers are worth to

an employer. Tus, these changes have served to increase the earnings of women relative

to those of men when calculated as earnings per hour, even for salaried workers.

High-income professional workers in many occupations receive a wage premium for

working long hours compared with those working fewer hours, but the wage efects for

lower-income workers follow a diferent patern. Tis report fnds that further down the

income scale, the impact of hours worked on pay is less one of receiving an hourly wage

premium for working more hours than it is one of experiencing a penalty for working

fewer hours. Te analysis reported here fnds that there is a large hourly wage penalty

for working fewer than 40 hours per week for moderate- to lower-income workers. For

most occupational groups, however, the penalty is not a function of gender: Both men

and women who work fewer hours get less pay per hour. But because women work fewer

hours than men on average per week, they are afected the most.

Tis report also demonstrates that of the occupational groups studied, those in the

technician group who work fewer than 40 hours per week are the least likely to have a

wage penalty among both men and women; the food, operator, and sales groups are the

most likely to have a wage penalty among hourly workers. Relative to men, women do

less well in terms of their implicit hourly wage in nonhourly sales jobs, especially if they

work fewer than 40 hours per week.

3 Center for American Progress | Hours, Flexibility, and the Gender Gap in Pay

Te forthcoming report delves into these issues in greater detail through original data

analysis using the U.S. Census Bureaus Current Population Survey Merged Outgoing

Rotation Groups. Te fndings, previewed here, provide a new perspective on the wage

issues facing low- to moderate-income workers. Although developing solutions to these

concerns is beyond the scope of this report, a beter understanding of wage disparities is

an important frst step to address the needs of the modern workforce.

Endnote

1 See, for example, Steven Greenhouse, A Part-Time Life, as Hours Shrink and Shift, The New York Times, October 27, 2012,

available at http://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/28/business/a-part-time-life-as-hours-shrink-and-shift-for-american-workers.

html?pagewanted=all&_r=0; Saki Knafo, On-Call Shifts Keep Low-Wage Workers From Getting Ahead,The Hufngton Post,

March 13, 2013.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Leveraging U.S. Power in The Middle East: A Blueprint For Strengthening Regional PartnershipsDocument60 pagesLeveraging U.S. Power in The Middle East: A Blueprint For Strengthening Regional PartnershipsCenter for American Progress0% (1)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- A Progressive Agenda For Inclusive and Diverse EntrepreneurshipDocument45 pagesA Progressive Agenda For Inclusive and Diverse EntrepreneurshipCenter for American ProgressPas encore d'évaluation

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Rhetoric vs. Reality: Child CareDocument7 pagesRhetoric vs. Reality: Child CareCenter for American ProgressPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Aging Dams and Clogged Rivers: An Infrastructure Plan For America's WaterwaysDocument28 pagesAging Dams and Clogged Rivers: An Infrastructure Plan For America's WaterwaysCenter for American ProgressPas encore d'évaluation

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Paid Leave Is Good For Small BusinessDocument8 pagesPaid Leave Is Good For Small BusinessCenter for American ProgressPas encore d'évaluation

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Housing The Extended FamilyDocument57 pagesHousing The Extended FamilyCenter for American Progress100% (1)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Preventing Problems at The Polls: North CarolinaDocument8 pagesPreventing Problems at The Polls: North CarolinaCenter for American ProgressPas encore d'évaluation

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- An Infrastructure Plan For AmericaDocument85 pagesAn Infrastructure Plan For AmericaCenter for American ProgressPas encore d'évaluation

- Addressing Challenges To Progressive Religious Liberty in North CarolinaDocument12 pagesAddressing Challenges To Progressive Religious Liberty in North CarolinaCenter for American ProgressPas encore d'évaluation

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- 3 Strategies For Building Equitable and Resilient CommunitiesDocument11 pages3 Strategies For Building Equitable and Resilient CommunitiesCenter for American ProgressPas encore d'évaluation

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Closed Doors: Black and Latino Students Are Excluded From Top Public UniversitiesDocument21 pagesClosed Doors: Black and Latino Students Are Excluded From Top Public UniversitiesCenter for American ProgressPas encore d'évaluation

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Fast Facts: Economic Security For Arizona FamiliesDocument4 pagesFast Facts: Economic Security For Arizona FamiliesCenter for American ProgressPas encore d'évaluation

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Preventing Problems at The Polls: FloridaDocument7 pagesPreventing Problems at The Polls: FloridaCenter for American ProgressPas encore d'évaluation

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- How Predatory Debt Traps Threaten Vulnerable FamiliesDocument11 pagesHow Predatory Debt Traps Threaten Vulnerable FamiliesCenter for American ProgressPas encore d'évaluation

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- A Market-Based Fix For The Federal Coal ProgramDocument12 pagesA Market-Based Fix For The Federal Coal ProgramCenter for American ProgressPas encore d'évaluation

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Preventing Problems at The Polls: OhioDocument8 pagesPreventing Problems at The Polls: OhioCenter for American ProgressPas encore d'évaluation

- America Under Fire: An Analysis of Gun Violence in The United States and The Link To Weak Gun LawsDocument46 pagesAmerica Under Fire: An Analysis of Gun Violence in The United States and The Link To Weak Gun LawsCenter for American Progress0% (1)

- Fast Facts: Economic Security For Illinois FamiliesDocument4 pagesFast Facts: Economic Security For Illinois FamiliesCenter for American ProgressPas encore d'évaluation

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Path To 270 in 2016, RevisitedDocument23 pagesThe Path To 270 in 2016, RevisitedCenter for American ProgressPas encore d'évaluation

- Fast Facts: Economic Security For New Hampshire FamiliesDocument4 pagesFast Facts: Economic Security For New Hampshire FamiliesCenter for American ProgressPas encore d'évaluation

- Fast Facts: Economic Security For Virginia FamiliesDocument4 pagesFast Facts: Economic Security For Virginia FamiliesCenter for American ProgressPas encore d'évaluation

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- Fast Facts: Economic Security For Wisconsin FamiliesDocument4 pagesFast Facts: Economic Security For Wisconsin FamiliesCenter for American ProgressPas encore d'évaluation

- The Missing Conversation About Work and FamilyDocument31 pagesThe Missing Conversation About Work and FamilyCenter for American ProgressPas encore d'évaluation

- Federal Regulations Should Drive More Money To Poor SchoolsDocument4 pagesFederal Regulations Should Drive More Money To Poor SchoolsCenter for American ProgressPas encore d'évaluation

- Opportunities For The Next Executive Director of The Green Climate FundDocument7 pagesOpportunities For The Next Executive Director of The Green Climate FundCenter for American ProgressPas encore d'évaluation

- Great Leaders For Great Schools: How Four Charter Networks Recruit, Develop, and Select PrincipalsDocument45 pagesGreat Leaders For Great Schools: How Four Charter Networks Recruit, Develop, and Select PrincipalsCenter for American ProgressPas encore d'évaluation

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- A Clean Energy Action Plan For The United StatesDocument49 pagesA Clean Energy Action Plan For The United StatesCenter for American ProgressPas encore d'évaluation

- A Quality Alternative: A New Vision For Higher Education AccreditationDocument25 pagesA Quality Alternative: A New Vision For Higher Education AccreditationCenter for American ProgressPas encore d'évaluation

- The Hyde Amendment Has Perpetuated Inequality in Abortion Access For 40 YearsDocument10 pagesThe Hyde Amendment Has Perpetuated Inequality in Abortion Access For 40 YearsCenter for American ProgressPas encore d'évaluation

- Workin' 9 To 5: How School Schedules Make Life Harder For Working ParentsDocument91 pagesWorkin' 9 To 5: How School Schedules Make Life Harder For Working ParentsCenter for American ProgressPas encore d'évaluation

- ICT ContactCenterServices 9 Q1 LAS3 FINALDocument10 pagesICT ContactCenterServices 9 Q1 LAS3 FINALRomnia Grace DivinagraciaPas encore d'évaluation

- Difference Between Gram Positive and GramDocument3 pagesDifference Between Gram Positive and Grambaraa aburassPas encore d'évaluation

- CW Catalogue Cables and Wires A4 En-2Document1 156 pagesCW Catalogue Cables and Wires A4 En-2Ovidiu PuiePas encore d'évaluation

- Gastroschisis and Omphalocele PDFDocument8 pagesGastroschisis and Omphalocele PDFUtama puteraPas encore d'évaluation

- Photosynthesis Knowledge OrganiserDocument1 pagePhotosynthesis Knowledge Organiserapi-422428700Pas encore d'évaluation

- H.influenzae Modified 2012Document12 pagesH.influenzae Modified 2012MoonAIRPas encore d'évaluation

- Governance, Business Ethics, Risk Management and Internal ControlDocument4 pagesGovernance, Business Ethics, Risk Management and Internal ControlJosua PagcaliwaganPas encore d'évaluation

- Thornburg Letter of RecDocument1 pageThornburg Letter of Recapi-511764033Pas encore d'évaluation

- Web Script Ems Core 4 Hernandez - Gene Roy - 07!22!2020Document30 pagesWeb Script Ems Core 4 Hernandez - Gene Roy - 07!22!2020gene roy hernandezPas encore d'évaluation

- AST CatalogDocument44 pagesAST CatalogCRISTIANPas encore d'évaluation

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- ARI 700 StandardDocument19 pagesARI 700 StandardMarcos Antonio MoraesPas encore d'évaluation

- Sample UploadDocument14 pagesSample Uploadparsley_ly100% (6)

- Revised Man As A Biological BeingDocument8 pagesRevised Man As A Biological Beingapi-3832208Pas encore d'évaluation

- CO2 & SelexolDocument18 pagesCO2 & Selexolmihaileditoiu2010Pas encore d'évaluation

- Ulangan Tengah Semester: Mata Pelajaran Kelas: Bahasa Inggris: X Ak 1 / X Ak 2 Hari/ Tanggal: Waktu: 50 MenitDocument4 pagesUlangan Tengah Semester: Mata Pelajaran Kelas: Bahasa Inggris: X Ak 1 / X Ak 2 Hari/ Tanggal: Waktu: 50 Menitmirah yuliarsianitaPas encore d'évaluation

- 2 Avaliação Edros 2023 - 7º Ano - ProvaDocument32 pages2 Avaliação Edros 2023 - 7º Ano - Provaleandro costaPas encore d'évaluation

- 6 Adjective ClauseDocument16 pages6 Adjective ClauseMaharRkpPas encore d'évaluation

- C 08 S 09Document8 pagesC 08 S 09Marnel Roy MayorPas encore d'évaluation

- Hedayati2014 Article BirdStrikeAnalysisOnATypicalHeDocument12 pagesHedayati2014 Article BirdStrikeAnalysisOnATypicalHeSharan KharthikPas encore d'évaluation

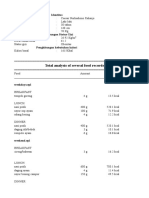

- Tugas Gizi Caesar Nurhadiono RDocument2 pagesTugas Gizi Caesar Nurhadiono RCaesar 'nche' NurhadionoPas encore d'évaluation

- Report On Marketing of ArecanutDocument22 pagesReport On Marketing of ArecanutsivakkmPas encore d'évaluation

- GEC PE 3 ModuleDocument72 pagesGEC PE 3 ModuleMercy Anne EcatPas encore d'évaluation

- Music Recognition, Music Listening, and Word.7Document5 pagesMusic Recognition, Music Listening, and Word.7JIMENEZ PRADO NATALIA ANDREAPas encore d'évaluation

- Network Access Control Quiz3 PDFDocument2 pagesNetwork Access Control Quiz3 PDFDaljeet SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Oseco Elfab BioPharmaceuticalDocument3 pagesOseco Elfab BioPharmaceuticalAdverPas encore d'évaluation

- Multiple AllelesDocument14 pagesMultiple AllelesSabs100% (2)

- Retrenchment in Malaysia Employers Right PDFDocument8 pagesRetrenchment in Malaysia Employers Right PDFJeifan-Ira DizonPas encore d'évaluation

- Plumber (General) - II R1 07jan2016 PDFDocument18 pagesPlumber (General) - II R1 07jan2016 PDFykchandanPas encore d'évaluation

- Development of Elevator Ropes: Tech Tip 15Document2 pagesDevelopment of Elevator Ropes: Tech Tip 15أحمد دعبسPas encore d'évaluation

- SCL NotesDocument4 pagesSCL NotesmayaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Great Displacement: Climate Change and the Next American MigrationD'EverandThe Great Displacement: Climate Change and the Next American MigrationÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (32)

- Heartland: A Memoir of Working Hard and Being Broke in the Richest Country on EarthD'EverandHeartland: A Memoir of Working Hard and Being Broke in the Richest Country on EarthÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (188)

- Workin' Our Way Home: The Incredible True Story of a Homeless Ex-Con and a Grieving Millionaire Thrown Together to Save Each OtherD'EverandWorkin' Our Way Home: The Incredible True Story of a Homeless Ex-Con and a Grieving Millionaire Thrown Together to Save Each OtherPas encore d'évaluation

- When Helping Hurts: How to Alleviate Poverty Without Hurting the Poor . . . and YourselfD'EverandWhen Helping Hurts: How to Alleviate Poverty Without Hurting the Poor . . . and YourselfÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (36)

- The Meth Lunches: Food and Longing in an American CityD'EverandThe Meth Lunches: Food and Longing in an American CityÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (5)

- Wordslut: A Feminist Guide to Taking Back the English LanguageD'EverandWordslut: A Feminist Guide to Taking Back the English LanguageÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (82)

- Not a Crime to Be Poor: The Criminalization of Poverty in AmericaD'EverandNot a Crime to Be Poor: The Criminalization of Poverty in AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (37)