Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Pinocchio Essay V 6

Transféré par

api-257416658Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Pinocchio Essay V 6

Transféré par

api-257416658Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

THE

NEVER-ENDING APPEAL

OF THE

FOREVER-GROWING NOSE

The Perpetual Illustrative Portrayals of Pinocchio,

Including their Importance and Persisting Implications

An extended essay by

Jack Taylor

B.A. Illustration

10,000 Word Research Report

2013-2014

Jack Taylor The Never-ending Appeal of the Forever-growing Nose

2

ABSTRACT

This essay aims to evaluate the various ways in which

the story of Pinocchio has been represented by

illustrators, both past and present, and their attempts to

continuously inject life into this classic tale. Beginning

with an assessment of the source text by Carlo Collodi

alongside the accompanying artwork (which was

provided by his friend Enrico Mazzanti), it may be

ascertained whether the cavalcades of future iterations

have handled their work with disrespect or only served to

enhance it for a new generation. A handful of notable

versions of both printed and filmic origin shall be

investigated, and in doing so, the recurrent themes and

devices as well as any potentially remnant avenues and

key considerations for people wishing to work with this

storied text in future will hopefully be uncovered.

Jack Taylor The Never-ending Appeal of the Forever-growing Nose

3

CONTENTS

Table of Illustrations........................................4-8

Introduction........................................................9

Chapter 1:

The Root of the Puppet...........................10-12

Chapter 2:

The Rise of the Puppet...........................13-21

Chapter 3:

The Retelling of the Puppet.....................22-35

Chapter 4:

The Repurposing of the Puppet...............36-41

Conclusion:

The Return of the Puppet............................42

Bibliography......................................................43

Jack Taylor The Never-ending Appeal of the Forever-growing Nose

4

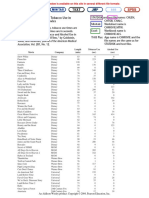

TABLE OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Figure

#

Page

Used

Artist Source Thumb

Chapter 2

1 13

Enrico

Mazzanti

Internet image retrieved from

http://www.daringtodo.com/

wp-

content/uploads/2011/03/Pin

occhio_visto_da_Enrico_Ma

zzanti_1883.jpg

2 14

Enrico

Mazzanti

Internet image retrieved from

http://ic.pics.livejournal.com/

nadezhdmorozova/20244507

/466243/466243_original.jpg

3 15

Enrico

Mazzanti

Internet image retrieved from

http://www.5cense.com/11/P

innochio/Gatto_e_volpe.jpg

4 16

Enrico

Mazzanti

Internet image retrieved from

http://upload.wikimedia.org/

wikipedia/commons/f/f1/Enri

co_Mazzanti_-

_the_hanged_Pinocchio_%2

81883%29.jpg

5 17

Enrico

Mazzanti

Internet image retrieved from

http://ic.pics.livejournal.com/

nadezhdmorozova/20244507

/466052/466052_original.jpg

6 18

Enrico

Mazzanti

Internet image retrieved from

http://www.imaginaria.com.a

r/21/0/ficciones-39-Pinocho-

Mazzanti.jpg

7 19

Enrico

Mazzanti

Internet image retrieved from

http://www.imaginaria.com.a

r/wp/wp-

content/uploads/2009/09/08-

pinocho-mazzanti.jpg

Jack Taylor The Never-ending Appeal of the Forever-growing Nose

5

Figure

#

Page

Used

Artist Source Thumb

8 20

Enrico

Mazzanti

Internet image retrieved from

http://upload.wikimedia.org/

wikipedia/en/d/dd/Terribile_

pescecane.jpg

9 21

Enrico

Mazzanti

Internet image retrieved from

http://3.bp.blogspot.com/-

3yBkUBVVixU/TYgSDHz0

UFI/AAAAAAAAANE/w32

YA9CwRHk/s400/pinocchio

_collodi_end.jpg

Chapter 3

10 22

James

Mayhew

Book scan from

Collodi, C. and Poole, J.

(1994) Pinocchio: Great

Britain: Simon & Schuster

Young Books

Page 17

11 23

James

Mayhew

Book scan from

Collodi, C. and Poole, J.

(1994) Pinocchio: Great

Britain: Simon & Schuster

Young Books

Page 75

12 24

Sara

Fanelli

Book scan from

Collodi, C. and Rose, E.

(2003) Pinocchio: London:

Walker Books

Page 148

13 25

Sara

Fanelli

Book scan from

Collodi, C. and Rose, E.

(2003) Pinocchio: London:

Walker Books

Page 50-51

14 26 (left)

James

Mayhew

Book scan from

Collodi, C. and Poole, J.

(1994) Pinocchio: Great

Britain: Simon & Schuster

Young Books

Page 30

Jack Taylor The Never-ending Appeal of the Forever-growing Nose

6

Figure

#

Page

Used

Artist Source Thumb

15

26

(right)

Sara

Fanelli

Book scan from

Collodi, C. and Rose, E.

(2003) Pinocchio: London:

Walker Books

Page 38

16 27

Sara

Fanelli

Book scan from

Collodi, C. and Rose, E.

(2003) Pinocchio: London:

Walker Books

Page 189

17 28 (top)

James

Mayhew

Book scan from

Collodi, C. and Poole, J.

(1994) Pinocchio: Great

Britain: Simon & Schuster

Young Books

Page 92

18

28

(bottom)

Scott

McCloud

Book scan from

McCloud, S. (1993)

Understanding Comics: The

Invisible Art: USA:

HarperCollins

Page 36

19 29

Sara

Fanelli

Book scan from

Collodi, C. and Rose, E.

(2003) Pinocchio: London:

Walker Books

Page 42-43

20 30

James

Mayhew

Book scan from

Collodi, C. and Poole, J.

(1994) Pinocchio: Great

Britain: Simon & Schuster

Young Books

Page 14

21 31 (left)

Sara

Fanelli

Book scan from

Collodi, C. and Rose, E.

(2003) Pinocchio: London:

Walker Books

Page 82

22

31

(right)

James

Mayhew

Book scan from

Collodi, C. and Poole, J.

(1994) Pinocchio: Great

Britain: Simon & Schuster

Young Books

Page 35

Jack Taylor The Never-ending Appeal of the Forever-growing Nose

7

Figure

#

Page

Used

Artist Source Thumb

23 33 (left)

James

Mayhew

Book scan from

Collodi, C. and Poole, J.

(1994) Pinocchio: Great

Britain: Simon & Schuster

Young Books

Page 2

24

33

(right)

Sara

Fanelli

Book scan from

Collodi, C. and Rose, E.

(2003) Pinocchio: London:

Walker Books

Page 14

25 34 (left)

James

Mayhew

Book scan from

Collodi, C. and Poole, J.

(1994) Pinocchio: Great

Britain: Simon & Schuster

Young Books

Page 37

26

34

(right)

Sara

Fanelli

Book scan from

Collodi, C. and Rose, E.

(2003) Pinocchio: London:

Walker Books

Page 87

27 35 (left)

James

Mayhew

Book scan from

Collodi, C. and Poole, J.

(1994) Pinocchio: Great

Britain: Simon & Schuster

Young Books

Page 48

28

35

(right)

Sara

Fanelli

Book scan from

Collodi, C. and Rose, E.

(2003) Pinocchio: London:

Walker Books

Page 103

Chapter 4

29 37 Unknown

Internet image retrieved from

http://petebooth.com/wp-

content/uploads/2014/02/An

nex-Bergen-Edgar_02.jpg

Original located at

http://filmstills.photoshelter.c

om/image/I0000TF2CZnr0Y

gg

Jack Taylor The Never-ending Appeal of the Forever-growing Nose

8

Figure

#

Page

Used

Artist Source Thumb

30 38

Walt Disney

animation

team

Still photographic image

capture from Disney, W. and

Sharpsteen, B. (1940)

Pinocchio [BD]: Walt

Disney

31 39

Golden Films

animation

team

Still screenshot capture from

Eskanazi, D. (1992)

Pinocchio [DVD]: Golden

Films

32 40

Golden Films

animation

team

Still screenshot capture from

Eskanazi, D. (1992)

Pinocchio [DVD]: Golden

Films

33 41

Walt Disney

animation

team

Still photographic image

capture from Disney, W. and

Sharpsteen, B. (1940)

Pinocchio [BD]: Walt

Disney

End of Table of Illustrations

Jack Taylor The Never-ending Appeal of the Forever-growing Nose

9

INTRODUCTION

The following essay intends, by way of example, to explore and deliberate the reasons

that publishers and illustrators may have for continually drawing upon classic

literature. More specifically, the devices that illustrators have employed whilst

handling a text shall be investigated, with the disparity in reception between those that

stick by the original perception or those that attempt to take liberties with it being

considered. This should verify the necessity, or lack thereof, for a text to be refreshed

in changing times. Due to the swathes of popular classics available, the focus shall be

upon one with a storied history of reinterpretation, Pinocchio, but both illustrative and

filmic variations of the classic tale will be dissected to produce a clearer picture that

details the various ways this story has been tackled.

To begin, the core themes and ideals behind the original version of the story by Carlo

Collodi shall be explained, so as to ascertain the audience that it was intended to

resonate with and the message that it was trying to impart, both through the writing

itself and via the illustrations provided by Enrico Mazzanti. Once this is established, it

can be used as a benchmark to evaluate how future illustrators have interpreted the

source to cater, perhaps, to a different demographic, or one that has since changed

during the time proceeding the original tales publishing in 1881.

In modern times, at least amongst those with an eye for distinctive illustration, the

2003 version with artwork provided by Sara Fanelli appears to be held in high regard,

and as such, this version shall be critically evaluated as the contemporary equivalent

to determine if its high esteem is justified. Keeping within the realms of literature, a

1994 retelling, which was illustrated in a very traditionally-minded manner by James

Mayhew, shall be given a look in contrast to Fanellis version; do these different

approaches retain similar design sensibilities?

Casting the line beyond print, the feature animation produced by Walt Disney in 1940

shall also be examined, mostly because this version is widely recognised in popular

culture and, in fact, is perhaps the only exposure certain people have had to the story

in question. Disney was able to condense the tale into a coherent film but also took

many artistic liberties when doing so; how this changed the way that Pinocchio is

perceived is an interesting topic of discussion. This adaptation will be studied

alongside the 1992 short animated film by Golden Films to see how this

representation of the tale was realised, and if when compared to the cinematic

Disney version it appears similar techniques may have been called upon.

With all of the above in mind, a considered judgement can be reached as to which of

the versions is the most successful in maintaining the spirit of the source. But most

significantly, any room still available for future interpretations to present a unique

spin on this classic tale can also be ascertained.

Jack Taylor The Never-ending Appeal of the Forever-growing Nose

10

CHAPTER 1

The Root of the Puppet

The following chapter introduces the original story and the importance of its

underlying meaning to the target audience, as well as illustrations place in

conveying this.

The original story of Pinocchio (in full: Le Avventure di Pinocchio) was written by

Carlo Lorenzini in 1881, under the pseudonym Carlo Collodi; it was first published in

an Italian childrens periodical on a chapter-by-chapter basis.

1

Whilst his target audience would imply certain characteristics about the tone of the

story, Collodi had apparently had enough with writing and attempted to kill off

Pinocchio, having him hung by assassins.

2

By todays standards, this would be a

surprisingly grim final for a piece of childrens literature (this event, whilst still

present in his finished story, instead acts as a watershed event around the midpoint.)

Being akin to a classic fairy tale, there is a frequent juxtaposition of fantasy and

reality to create a certain shock factor; the storys setting seems to be almost

subdivided into two realms, one of which is bizarrely fantastical and dreamlike, and

one that is relatively normal. This manner of contrast is often seen in this genre of

storytelling, a subject Bruno Bettelheim explores in his book The Uses of

Enchantment:

The fairy tale clearly does not refer to the outer world, although it may begin

realistically enoughThe unrealistic nature of these talesis an important device,

because it makes obvious that the fairy tales concern is not useful information about

the external world, but the inner process taking place in an individual.

3

Some of the events, like the aforementioned hanging, are strangely nightmarish and

potentially frightening to young readers; however, children can also relate to this, as

one would assume that they are also subjected to certain, terrible nightmares that they

cant wake up from; this is part of the inner process described above. The ultimate

realisation of this idea is when Pinocchio, after a string of misfortunes, becomes a

donkey and has to perform at the circus; this certainly echoes the harrowing sensation

of an inescapable nightmare (and one which, of course, only ends the moment that

Pinocchio finally wakes up as a real boy). Bettelheim explains at length how a fairy

tale which steadfastly refuses to shy away from dark subject matter is in fact much

more beneficial to a childs psychological development:

1

The story of Pinocchio was originally published in instalments begun inthe first Italian periodical

for children: the Giornale per i bambini (paper for children). - Nicolini, C. (2013) Puppet Power.

Illustration Magazine, Summer 2013 [Pg. 9]

2

Collodi continued his tale until he lost interest and decided to kill Pinocchio off. In Chapter 15the

Fox and the Cat disguised as assassins hung the puppet from a tree. - Nicolini, C. (2013) Puppet

Power. Illustration Magazine, Summer 2013 [Pg. 9]

3

Bettelheim, B. (1976) The Uses of Enchantment: Great Britain: Thames and Hudson [Pg. 25]

Jack Taylor The Never-ending Appeal of the Forever-growing Nose

11

Safe stories mention neither death northe limits to our existenceThe fairy

tale, by contrast, confronts the child squarely with the basic human predicamentsit

is characteristic of fairy tales to state an existential dilemma briefly and pointedly.

This permits the child to come to grips with the problem in its most essential form.

4

Having to confront (and eventually overcome) existential dilemmas and terrible

predicaments is certainly a recurrent theme throughout Pinocchio, in which the titular

puppet is increasingly faced with the threat of poverty, starvation and death.

Interestingly, the puppets troubles are almost always engineered by his own hand,

which bestows upon him the bizarre honour of essentially being the tales protagonist

and antagonist simultaneously; Pinocchio is his own worst enemy. This particular

brand of character is, in fact, especially useful for a child reader attempting to

overcome his inner demons:

The fairy tale begins with the hero at the mercy of those who think little of himand

even threaten his lifeas the story unfolds, the hero is often forced to depend

onmagic animalsat the tales end the hero has mastered all trials andhas

achieved his true selfhoodIn fairy talesvictory isonly over oneself and over

[ones own] villainy.

5

Although the above quote is referring to fairy tales in general, it is an incredibly

accurate description of Pinocchios underlying plot progression. From the outset,

Pinocchio is portrayed as a wholly unlikeable character; a miscreant and a vagabond

subject to the scorn of the readership. But although it might initially seem difficult to

identify with such a rambunctious character, children can relate because [they] know

that they are not always goodand [that] therefore makes the child a monster in his

own eyes.

6

The way that this is of use to the child, then, is in how Pinocchio (as

impish as he may initially seem) does not remain a monster forever; he finds a

solution to the problems that hound him and is purged of all contempt by the storys

end. In fact, the level of character development afforded for Pinocchio throughout the

tale is an astonishing feat of literature, as Collodi transforms a character that we

immediately revile into someone with emotions and ambition who we genuinely care

about; strong and well-written characters such as this are what may initially attract

illustrators to take up the mantle.

Attractive a proposition as this may be, in reality the manner in which Pinocchio must

be presented as a character through illustration is a tough scale to balance; outward

appearances carry heavy connotations towards a characters alignment, as indicated

by Perry Nodelman: there are rarely ugly heroes or handsome villains in illustrated

versions of fairy tales assuming, of course, our usual societal values about what

constitutes beauty and ugliness.

7

To elaborate, it is for this very reason that Martin

Salisbury affirms the incredible difficulty one must face to ascertain how best to

depict a character:

Whether or not any genuine research has been carried out in the way children

respond to the various stylistic approaches to character representation is

4

Bettelheim, B. (1976) The Uses of Enchantment: Great Britain: Thames and Hudson [Pg. 8]

5

Bettelheim, B. (1976) The Uses of Enchantment: Great Britain: Thames and Hudson [Pg. 127/128]

6

Bettelheim, B. (1976) The Uses of Enchantment: Great Britain: Thames and Hudson [Pg. 8]

7

Nodelman, P. (1988) Words About Pictures: Georgia: University of Georgia Press [Pg. 112]

Jack Taylor The Never-ending Appeal of the Forever-growing Nose

12

unclear[but] it is surprising how frequently artists character studies are rejected

as being too ugly or not pretty enough.

8

Pinocchio, contrary to the above, must be both convincingly loathsome and

mischievous one moment, yet loyal and resolute the next; depicting him as merely

despicable or admirable instantly hamstrings his developmental horizons by branding

his nature with one of only two sensibilities. How would one go about conveying a

characters moralistic evolution simply through one consistently beautified

appearance? Bettelheim argues that it is, in fact, essentially impossible to depict such

philosophically significant plots without demeaning its original substance:

Illustrated storybooksdo not serve the childs best needs. The illustrations are

distracting rather than helpful[and] direct the childs imagination away from

how[they] would experience the story [it] is robbed of muchpersonal meaning

which it could bring to the child who applied only his own visual associations to the

story, instead of those of the illustrator.

9

On the other hand, this opinion stubbornly refuses to admit that illustrations can, in

certain circumstances, convey meanings to a child much more transparently than

perhaps the accompanying text would on its own. This is especially pertinent to

younger children with a lower standard of reading comprehension, who are more

likely to react to the significance attached to visual stimuli. Martin Salisbury

acknowledges the importance of a childs exposure to imagery:

For children, pictures in books are often their first means of making sense of a world

they have not yet begun to fully experienceillustration is a subtle and complex art

form that can communicate on many levels and leave a deep imprint on a childs

consciousness.

10

Clearly, there is an apparent need for artists to lend their visual skills to stories such as

Collodis timeless narrative, as their imagery can help convey substance to their

developing, impressionable audience. It is with this in mind that we shall henceforth

begin our journey through the puppets everlasting venture within the world of

illustration.

8

Salisbury, M. (2004) Illustrating Childrens Books: London: A&C Black Publishers [Pg. 66]

9

Bettelheim, B. (1976) The Uses of Enchantment: Great Britain: Thames and Hudson [Pg. 59/60]

10

Salisbury, M. (2004) Illustrating Childrens Books: London: A&C Black Publishers [Pg. 6]

Jack Taylor The Never-ending Appeal of the Forever-growing Nose

13

CHAPTER 2

The Rise of the Puppet

The following chapter aims to describe the aesthetic of the original story, the message

that it was attempting to portray and how these relate to its most notable scenes and

characters.

The preceding chapter established that Carlo Collodi first wrote and eventually

published his story, Le Avventure di Pinocchio, in 1881. Before his death in 1890 he

saw only one illustrator attempt to envisage his manuscript Enrico Mazzanti, who

was a close friend of Collodis and specifically entrusted with this task by the

aforementioned writer.

11

Whilst one can merely speculate, assumedly this personal

association would suggest that Mazzantis portrayal of the character had been

influenced and shaped to the whim of Collodi himself and therefore not simply that of

the illustrator; perhaps, one could argue, this makes it the one true likeness of the

hero and his world. Therefore, we shall begin by examining both Mazzantis drawings

and the content of the original book side by side, as they are indubitably related:

It is impossible to talk sensibly about the meaning of the picturesin isolation from

the words that evoked their creation in the first place.

12

To anyone familiar with prettified, modern

interpretations of the character, Mazzantis

depiction may come as a bit of a surprise;

surely this isnt the same happy-go-lucky

puppet weve come to expect? But in many

ways, this interpretation is as close to the

original description as one could reach. Two

of Pinocchios most iconic features, his nose

[that] was as long as if there was no end to

it

13

as well as his suit [made] out of

flowered paper

14

, are both readily evident.

Pinocchio is also very angular and pointy

(especially his almost demonic, claw-like

hands) giving him a tangible air of

unpredictability and menace, yet his thin

limbs also imply a brittleness consistent with

his tendency to be continually subjected to

dire situations which threaten his life. The

protruding spike of his nose is echoed by the

11

Its illustration was entrusted to Enrico Mazzanti, a close friend of Collodis who had already

illustrated his translations of French fairy tales. This was the only version of Pinocchio to be

illustrated in Collodis lifetime. Nicolini, C. (2013) Puppet Power. Illustration Magazine, Summer

2013 [Pg. 10-11]

12

Nodelman, P. (1988) Words About Pictures: Georgia: University of Georgia Press [Pg. 40]

13

Collodi, C. and Harden, E. (1882) Pinocchio: Australia: Consolidated Press [Pg. 14]

14

Collodi, C. and Harden, E. (1882) Pinocchio: Australia: Consolidated Press [Pg. 34]

Fig. 1

Jack Taylor The Never-ending Appeal of the Forever-growing Nose

14

backwards taper of his hat, which affords a sense of imbalance and makes his image

appear slightly unsettling. Finally, his lankiness suggests a haughtily arrogant attitude,

amplifying his resolve to not ever be told what to do:

Of all the trades in the world, there is only one which really attracts meTo eat,

drink, sleep, and amuse myself, and to lead a vagabond life from morning to night.

15

This all adds up to a lead character whom we despise and feel repulsed by; within

narrative context, the traits imbued by this image serve to amplify Collodis written

characterisation of Pinocchio as being an obnoxious character. And whilst this may

seem like a dangerous attribute to attach to ones protagonist, as outlined in Chapter

1, it is also exactly what Collodi intended, for it is clear at the beginning of the novel

that the reader is supposed to identify not with Pinocchio but with the poor father,

Geppetto, who has been cursed with such an unruly child:

Wretched son! And to think I worked so hard to make a fine puppet! But serve me

right. I ought to have known what would happen.

16

As previously suggested, Pinocchio begins as the villain of the piece, bringing

misfortune not only to himself but to all those around him; in the novels third

chapter, Geppetto is arrested and imprisoned in place of his son, for Pinocchio pushes

the blame for his misdeeds onto his

unsuspecting father; he is criminalised

by onlookers after he designs to teach

Pinocchio a stern lesson.

[Geppetto] took [Pinocchio] by the

nape of his neck, and as they walked

away he said, shaking his head

menacingly, You just come home,

and Ill settle your account when we

get there!

17

This image by Mazzanti does seem to

cast Geppetto as a rather threatening

and foreboding figure. The manner in

which Pinocchios pose mirrors that

of Geppettos shows that they are

inextricably connected, and that in

this situation they perhaps are, in fact,

as bad as each other; although

Pinocchio was born a mischievous

urchin, Geppetto is still having to come to terms with his apparently misplaced wish

for a son. However, as we are deprived of the characters expression, we therefore

cannot tell if Geppetto is truly angry and is merely attempting to lead Pinocchio away

from danger (appearing also to be having a difficult time in doing so); as such the

15

Collodi, C. and Harden, E. (1882) Pinocchio: Australia: Consolidated Press [Pg. 20]

16

Collodi, C. and Harden, E. (1882) Pinocchio: Australia: Consolidated Press [Pg. 17]

17

Collodi, C. and Harden, E. (1882) Pinocchio: Australia: Consolidated Press [Pg. 16]

Fig. 2

Jack Taylor The Never-ending Appeal of the Forever-growing Nose

15

puppet is still the vessel for our contempt, for he appears to care not for the thought of

his father; a feeling evidenced once he decides to run away from home once more.

Pinocchios misadventures in the wider world truly begin to unfold once he is

approached by a fox who was lame in one foot, and a cat who was blind in both eyes,

getting along as best they could, like good companions in misfortune.

18

Contrary to most modern depictions (see Fig. 10 and Fig. 13 later in this essay),

Mazzanti depicts the Fox and the Cat as ordinary quadrupedal animals. The cats

blindness is represented via closed eyes and the foxs lameness by an awkward gait

(however their invalidity is merely a sham). In this scene, we actually identify with

Pinocchio for likely the first time, as a character on the lower left with his back

turned to us will receive the most sympathy, for his position is most like our own in

relation to the picture.

19

In other words, we are both being confronted by these two

slightly suspicious looking animals together; Pinocchios pose and helpless

expression suggest he doesnt yet know what to make of them, as nor do we as the

reader.

Action usually moves from left to right in picture books; and obviously, then, time

conventionally passes from left to right.

20

Bearing this in mind, the above image now

implies halted progress, as though the animals are barricading Pinocchio and holding

his attention hostage. This works in the dialogues favour, as Pinocchio is incredibly

indecisive about whether or not he should join the pair or not:

Pinocchio thought for a momentNo, Im not going. Im nearly at home, and I

want to go to my father

18

Collodi, C. and Harden, E. (1882) Pinocchio: Australia: Consolidated Press [Pg. 50]

19

Nodelman, P. (1988) Words About Pictures: Georgia: University of Georgia Press [Pg. 136]

20

Nodelman, P. (1988) Words About Pictures: Georgia: University of Georgia Press [Pg. 163]

Fig. 3

Jack Taylor The Never-ending Appeal of the Forever-growing Nose

16

Well, then, said the fox, so you really want to go home? Run along, then, and so

much the worse for you!

Forgetting his father,[Pinocchio] said to the fox and the cat, Well, lets start! I

shall come with you.

21

If the Fox and the Cat can be said to embody bad influences (with the foxs cunning

and the cats impassiveness), then this idea of the pair impeding Pinocchios

progress in the image ties into a portion of the philosophy of fairy tales; Bettelheim

describes how seemingly unsolvable predicaments can naturally present themselves to

an individual:

Fairy tales [convey to the child that] severe difficulties in life [are] unavoidable,

[and are] an intrinsic part of human existence but that is if one does not shy away,

but steadfastly meetsall obstacles and at the end emerges victorious.

22

By the logic of the old saying birds of a feather flock together, the disobedient

Pinocchio travels for a time with these two delinquents, falling in with company

befitting his own current moralistic virtues. Unbeknownst to the puppet, this

relationship would in fact end in his untimely death.

A scene often missing from

recent adaptations,

Pinocchios hanging is the

result of Collodis intent to

kill off his character (see

Chapter 1.) The Fox and the

Cat endeavour to rob the

puppet by assassinating him

with knives, but upon

finding his wooden body

resisted their blades they

bound his arms behind his

back and, putting a running

noose around his throat, they

tied him to a branch of a big

oak tree.

23

Mazzanti, in

particular, appears to have

illustrated the moments

before his death rather than

the death itself:

A stormy north wind had begun to blow, and it raged, and it whistled, and blew the

poor puppet back and forth as fast as the bell-clapper on a wedding-day. It hurt him

dreadfully, and the running noose tightened around his throat so that he could not

breathe.

24

21

Collodi, C. and Harden, E. (1882) Pinocchio: Australia: Consolidated Press [Pg. 52/53]

22

Bettelheim, B. (1976) The Uses of Enchantment: Great Britain: Thames and Hudson [Pg. 8]

23

Collodi, C. and Harden, E. (1882) Pinocchio: Australia: Consolidated Press [Pg. 64]

24

Collodi, C. and Harden, E. (1882) Pinocchio: Australia: Consolidated Press [Pg. 65]

Fig. 4

Jack Taylor The Never-ending Appeal of the Forever-growing Nose

17

To avoid showing the finality of Pinocchios death, Mazzanti has opted to focus on

the above action specifically to keep the resolution implied:

Picture books are filled with pictures that show an action just before it reaches its

climaxin this storytelling medium, the evocation of action is of the essence.

25

On the other hand, closer inspection may render this implication superficial; despite

the gusting of the wind, as evidenced by the scattering of leaves and the swing of the

rope, Pinocchios body is entirely rigid, as though it may in fact already have

succumbed to death. It is quite clear from the wide-eyed expression of his face that

this is not the case; the stiffness of body rather serves to foreshadow his eventual fate.

Rescued by the Blue-haired Fairy that lives in the woods, the puppets lifeless body

is then examined by her three magical doctors.

The crow came forward first, and felt Pinocchios pulse; then he felt his nose, and

finally his little toe. Having examined them carefully he solemnly declared, It is my

opinion that this puppet is quite dead, but if, unfortunately, he is not dead, then that

would be a sure sign that he is still alive.

26

25

Nodelman, P. (1988) Words About Pictures: Georgia: University of Georgia Press [Pg. 160]

26

Collodi, C. and Harden, E. (1882) Pinocchio: Australia: Consolidated Press [Pg. 69]

Fig. 5

Jack Taylor The Never-ending Appeal of the Forever-growing Nose

18

It should be noted that, at odds with the realistic forms adopted by the Fox and Cat,

the doctors are clearly anthropomorphised by Mazzanti; the Crow even has what

appears to be a regular human hand. This suggestion of humanity perhaps ties in with

their comparative benevolence to the villainous assassins; the idea that they are

attempting to assist Pinocchio as opposed to conspiring to murder him. We relate

more to the image of a human because the minds of animals are difficult for us to

read, and therefore become more uncertain:

The actors in a story are usually humananimals have been introduced, butwe

know too little so far about their psychologyuntil [that] comes the actors in a story

are, or pretend to be, human beings.

27

On the other hand, it is also worth noting that this scene occurs directly after the

hanging, which was the initial ending of the story. Following the immediate

introduction of the Blue Fairy to bring the puppet back to life, it is therefore possible

that the anthropomorphised doctors are also indicative of Collodis shift to a plot

more cemented in a fantastical, fairy-story genre, less concerned with reality.

Despite the crows assessment, Pinocchio, it seems, is not yet dead, but refuses life-

saving medication from the Blue Fairy because he insists:

Its too

bitter!...I cant

drink it.

Are you not

afraid to die?

Not a bit! Id

rather die than

drink that horrid

medicine!

At that moment,

the door of the

room opened, and

four rabbits as

black as ink came

in, carrying a

little black coffin

on their shoulders.

28

Mazzanti has played up the description of the rabbits ink-black bodies by literally

rendering them incredibly densely with his own ink; this contrasts tremendously with

the lined-and-hatched drawing elsewhere, as though the rabbits really have arrived

from a very separate underworld to come and take Pinocchio away. Pinocchio is also

shaded rather solidly here; this connection establishes the rabbits relationship to him.

27

Forster, E. (1927) Aspects of the Novel: England: Penguin Books

28

Collodi, C. and Harden, E. (1882) Pinocchio: Australia: Consolidated Press [Pg. 72/73]

Fig. 6

Jack Taylor The Never-ending Appeal of the Forever-growing Nose

19

By this point, you cant help but feel slightly sorry for the puppet, especially in

conjunction with the alarmed and frenzied expression Mazzanti has bestowed upon

him.

Although the puppet eventually takes the medicine and gets better, no amount of

advice given by the Blue Fairy can coerce Pinocchio from committing further

misdemeanours. Even after being promised the realisation of his wish to become a

real boy, he runs away with Lampwick to Playland, lured by the promise of school-

free weeks and perpetual holidays; it is here that he is fated to become a donkey, and

not a boy. This bait-and-switch-esque reversal is somewhat of a trope in fairy stories,

but with good reason:

Evil is not without attractions [and often] a usurper succeeds for a time in seizing

the place which rightfully belongs to the heroThe child [identifies with the hero]

and the inner and outer struggles of the hero imprint morality on him.

29

Whereas the Fox and the

Cat filled a similar role

earlier in the story, the

usurper is now

Lampwick (as well as the

child-ferrying

Coachman.)

At last the coach

arrivedIt was drawn by

twelve pairs of donkeys,

all the same size. Some

were grey, some white,

some spotted, others

again were yellow and

blue in large stripes.

30

This image of the

Coachmans arrival with

his team of donkeys uses

a similar technique to the

above illustration of the

rabbits, creating an

incredibly dense form

which brings a sinister

mood, as though he were

also sent specifically

from a world of darkness to lead Pinocchio to his demise.

The nontextual elements that create mood or atmospherelikethe artists choice

of medium and style, the density of texturefocus our expectations even before we

29

Bettelheim, B. (1976) The Uses of Enchantment: Great Britain: Thames and Hudson [Pg. 8/9]

30

Collodi, C. and Harden, E. (1882) Pinocchio: Australia: Consolidated Press [Pg. 145]

Fig. 7

Jack Taylor The Never-ending Appeal of the Forever-growing Nose

20

explore the pictures closely enough to notice the relationships between their details;

they imply an overall mood or atmosphere that controls our understanding of the

scenes depicted.

31

Mazzanti seems to have used darkness to signify an unknown and impending threat;

the earlier image of the hanging is not dark, for its implications were already a known

quantity. In other words, this silhouette can be seen to be literally foreshadowing

the eventual transformation into a donkey.

Lamed at the circus, Pinocchio the donkey is sold on to a village band member, who

wishes to use his hide to re-skin a drum. Instead of drowning, Pinocchios flesh is

eaten by fish to reveal the puppet underneath, so the drummer decides to use his

wooden body to light his fire instead. Hearing this, Pinocchio escapes by swimming

out to sea, but then has a run-in with the terrible dogfish an overgrown shark.

Pinocchiosawa rock which looked like white marble[where] a beautiful little

goat was bleating, and beckoning him to come nearerdoubling his energy, he swam

towards the white rockwhen he saw, rushing towards hima sea monster with a

horrible head, and [a] mouthwith three rows of teeth that would have frightened

anyone, even in a picture.

32

Pinocchio is literally caught between a rock and a hard place as he desperately

attempts to join the goat in safety. His silhouette is barely noticeable in Mazzantis

illustration, lost to the waves and the towering form of the shark. The image seems to

focus on the juxtaposition between the sanctuary of the rock on one side and the

cavernous, gaping maw on the other; Pinocchios outstretched form links the two

31

Nodelman, P. (1988) Words About Pictures: Georgia: University of Georgia Press [Pg. 41/42]

32

Collodi, C. and Harden, E. (1882) Pinocchio: Australia: Consolidated Press [Pg. 170/171]

Fig. 8

Jack Taylor The Never-ending Appeal of the Forever-growing Nose

21

together. However, the shark itself actually appears slightly comical and non-

threatening besides its bared rows of teeth; perhaps the image of a monster described

as being so frightening is one thing best left to the imagination:

Asking childrenwhat a monster they have heard about in a story looks like, elicits

the wildest variations of embodimenteach of these details has great meaning to the

person who in his minds eye created this particular pictorial realizationseeing the

monster as painted by the artist in a particular waymay then leave us entirely cold,

having nothing of importance to tell us.

33

Although consumed by the shark, the puppet discovers his father Geppetto trapped

inside, and the two escape by riding aback a tuna fish. With his father unwell,

Pinocchio works night and day to return him to health, thus earning the right to

become a real boy at last.

Geppetto [pointed] to a large

puppet that was leaning against a

chairso that it was a miracle that

he could stand there.

Pinocchiosaid to himself

contentedly, How ridiculous I was

when I was a puppet! And how

happy I am to have become a real

boy!

34

The final scene is indicative of a

rebirth for the character, and thus

the human Pinocchio bears no

resemblance to the dislikeable

ruffian he once was; he has

developed so much as an individual

that they may as well be entirely

different people. The message

imparted to child and adult alike is

that you, too, may one day mature

as a dependable and respectable person and, as Mazzantis drawing shows, be able to

look down upon your former self and say with conviction that you are now able to

stand solidly on your own two feet.

What the child needs most is to be presented with symbolic images which reassure

him that there is a solutionthe fairy tale offers fantasy materials which suggest to

the child in symbolic form what the battle to achieve self-realisation is all about, and

it guarantees a happy ending.

35

33

Bettelheim, B. (1976) The Uses of Enchantment: Great Britain: Thames and Hudson [Pg. 60]

34

Collodi, C. and Harden, E. (1882) Pinocchio: Australia: Consolidated Press [Pg. 191]

35

Bettelheim, B. (1976) The Uses of Enchantment: Great Britain: Thames and Hudson [Pg. 39]

Fig. 9

Jack Taylor The Never-ending Appeal of the Forever-growing Nose

22

CHAPTER 3

The Retelling of the Puppet

The following chapter aims to evaluate the methods by which the Pinocchio story has

been presented through future illustration. Two different approaches shall be

compared: those employed by James Mayhew (1994) and Sara Fanelli (2003),

henceforth beginning with the former.

3.1 James Mayhew A Conventional Puppet

The version illustrated by James Mayhew has a very

intricate and traditional aesthetic, supposedly

tak[ing] inspiration from the colours and images of

the Italian landscape.

36

Although there appears to

be an emphasis on elaborate line-work, the colours

used are also very airy, approaching pastel shades.

However, the combination of line and form appears

perceptibly dense, and is therefore occasionally

reminiscent of an oil painting, despite rendering his

work us[ing] inks on china clay paper.

37

What this

lends to the story is a very dreamlike aura of whimsy

whilst retaining, paradoxically, an element of sure-

footed reality; a sensation most suitable for the

realms of fantasy-fiction, as Perry Nodelman

suggests:

Richly detailed environments [are] found mainly in

pictures that illustrate fantasiesthe more these

pictures look like traditional oil paintings, the more

solidly real seem the fantasy places and objects they

depict.

38

Mayhew enhances these feelings of realistic

involvement within his images via his equally strong

sense of composition; Nodelman, in a number of

instances, presents his allusion that illustrating a

story is, for all intents and purposes, much like

arranging a stage play during theatre:

Both stage directors and picture-book illustrators suggest the relationships of their

characters by placing them in ways that make use of the directed tensions of visual

imagerythe relative positions of characters within it [then] become meaningful.

39

36

Collodi, C. and Poole, J. (1994) Pinocchio: Great Britain: Simon & Schuster Young Books [Jacket]

37

Salisbury, M. (2004) Illustrating Childrens Books: London: A&C Black Publishers [Pg. 107]

38

Nodelman, P. (1988) Words About Pictures: Georgia: University of Georgia Press [Pg. 76]

39

Nodelman, P. (1988) Words About Pictures: Georgia: University of Georgia Press [Pg. 156]

Fig. 10

Jack Taylor The Never-ending Appeal of the Forever-growing Nose

23

Directed tensions here specifically refers to devices such as framing and the spatial

positioning of inclusive elements. Mayhews inherent grasp of such techniques clearly

derives from his own passion for theatre and costumery: Theatre [continues] to play

an important role in his work[his] illustrated collections and anthologies[reflect]

his cultural interests.

40

As such, he is able to perceive the illustrated world through the eyes of an established

stage designer; this may explain why he chooses to frame many of his pieces, for a

40

Salisbury, M. (2004) Illustrating Childrens Books: London: A&C Black Publishers [Pg. 106]

Fig. 11

Jack Taylor The Never-ending Appeal of the Forever-growing Nose

24

frame around a pictureimplies detachment and objectivity[a] worldseparate

from our own world, marked off for us to look at

41

, just as the performers of a stage

production are encapsulated within an isolated diorama for the audience to observe.

An excellent example of Mayhew employing his compositional eye can be seen

above; the curtains frame our glimpse at the circus like a view-finder. The curve of

the ring confines, and draws focus to, the characters and performers, separating them

further from us and the rest of the audience. Finally, the spotlight brings ultimate

attention to Pinocchio in the centre.

Now having briefly discussed the basic intrinsic qualities of James approach and

philosophy, we shall direct our attention on to Sara Fanelli.

3.2 Sara Fanelli A Contemporary Puppet

In conjunction with an all-new translation penned by Emma Rose, Fanelli offered a

more contemporary approach in 2003 to freshen up this aging tale as part of Walker

Books Illustrated Classics series, republished in 2009. Fanelli is said to have

undertaken the task of illustrating the story of Pinocchio for it was a part of [her]

childhood[she] fell for the energy and surrealism of the puppets escapades [and]

tried to create a world that would be playful and attractive to a contemporary child

yet which was also truthful to the original setting of the story.

42

The use of the surrealist label can

certainly be applied to the final

production (see Fig. 12), and

may in fact be a turn-off for

certain individuals when

compared to endeavours such as

Mayhews more conventional,

traditional approach; Martin

Salisbury has this to say of her

work:

[Sara Fanelli] possesses that

rare gift of a childlike approach

to shapes, colours and mark-

making combined with a deeply

sophisticated sense of design and

a passionate and cultured mind.

Books like Saras, which in many

ways can be seen as true artists

books, can invite criticism from

publishers and librarians, some

of whom feel that the books are

aimed over the heads of children.

43

41

Nodelman, P. (1988) Words About Pictures: Georgia: University of Georgia Press [Pg. 50]

42

Collodi, C. and Rose, E. (2003) Pinocchio: London: Walker Books [Pg. 1]

43

Salisbury, M. (2004) Illustrating Childrens Books: London: A&C Black Publishers [Pg. 19]

Fig. 12

Jack Taylor The Never-ending Appeal of the Forever-growing Nose

25

As suggested above, the most frequent form of this criticism is the assertion that the

imagery is far too conceptually abstract and as such only has value as a curio a

collectors piece as opposed to catering to the anticipated audience:

This picaresque narrative makes a strange partner to Fanelli's up-to-date paper

collages and loose pen-and-brush sketcheswith its variegated layout and wordless

full-bleed spreads, the volume most resembles an artist's handmade book;

[Fanellis]modish treatment, a far cry from conventional versions of the classic,

may be best suited to collectors.

44

However, this dismissive mindset is perhaps incredibly misguided, for without

slightly left-field approaches like Fanellis to really push the envelope of illustration,

the industry will be reluctant to change its attitudes and advance the medium,

particularly in terms of the approaches which become acceptable for any given

purpose (such as a dated fairy story). Salisbury elaborates:

We know from historythat what is regarded as radical or cutting edge can quickly

become mainstream and much imitatedwork taking place on the boundaries of any

creative discipline is essential for its all-around vitality.

45

That certain angles should be sequestered into an arbitrary suitability bracket for

collectors only shows how close-minded both the publishers and consumers can

be. As Perry Nodelman puts forward in Words About Pictures, having various takes

on a single narrative is clearly of no detriment and can be nothing but beneficial:

The illustrations in picture booksare merelyone out of many potentially

convincing ways of filling a gapsince they are incomplete by definition, picture-

44

Publishers Weekly (2004) Childrens Book Review: Pinocchio. Available from:

<http://www.publishersweekly.com/978-0-7636-2261-9> [Accessed 19 Feb 2014]

45

Salisbury, M. (2004) Illustrating Childrens Books: London: A&C Black Publishers [Pg. 19]

Fig. 13

Jack Taylor The Never-ending Appeal of the Forever-growing Nose

26

book texts can always be realisedand made into different stories, by different kinds

of pictures.

46

Approaches such as Fanellis may stir controversy, then, but when one is filling a

niche to cater to differing tastes it becomes exceedingly difficult to call foul,

especially when the creator in question has become distinguished, bestowed by

accolades such as the V&A Illustration Award (2004)

47

; if one should not like any

particular rendition, there are thousands of other takes available one may appreciate

instead; that Fanellis version coexists with Mayhews does not detract from the

existence of either interpretation, or indeed the original work by Mazzanti. Thus, the

following analysis attempts to evaluate these approaches from two seemingly very

different artists under the simple common stipulation of them having both lent their

talents to illustrating Pinocchio.

3.3 Depicting the Puppet

It wouldnt be Pinocchio without the titular hero himself, so we begin by contrasting

the manner in which both Mayhew and Fanelli have chosen to depict this mischievous

urchins wooden visage in detail.

On the left (Fig. 14) we have Pinocchio as portrayed by James Mayhew, and to the

right (Fig. 15) is Sara Fanellis incarnation of the character. As may seem readily

apparent, neither of these renditions bears any perceptible resemblance to one another

besides the colour of the puppets finish, his flowered-paper suit and trademark long

nose; all three of these features are also visualised reasonably dissimilarly between

the two representations.

46

Nodelman, P. (1988) Words About Pictures: Georgia: University of Georgia Press [Pg. 83]

47

V&A (2004) V&A Illustrations Awards 2004. Available from:

<http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/v/about-the-winning-artists/> [Accessed 19 Feb 2014]

Fig. 14

Fig. 15

Jack Taylor The Never-ending Appeal of the Forever-growing Nose

27

Evidently, Mayhew chooses to use a more realistic style with a fashion-sense which

echoes Mazzantis rendition: rimmed, pointed cap; a ruff around the neck; elegant

patterning in the clothing with a low hem; long, pointed shoes. Fanelli, on the other

hand, has utilised an approach that could go so far as to be called abstract, affording a

sense of individuality. This disparity may be attributable to a number of different

reasons, but the most likely is indubitably linked to the manner in which the artists

have interpreted the text on a personal level:

Illustrators must make the choices that create style in picture books deliberately in

the context of their conception of the narrative effect they intend/ So-called realistic

art inevitably implies an attitude of scientific objectivityWe assume that surrealism

is imaginative and mysterious because the surrealist style has traditionally been used

in relationship to mysterious, imaginative subjects.

48

As such, we view the world as depicted by Mayhew with a sense of almost helpless

disconnect because, at the same time, we feel a compulsion a strange sense of

ownership towards the puppet (as though we were Geppetto himself), by virtue of

the almost graspable tangibility of James images. Conversely, Fanelli chooses to play

up the absurdity of this fantasy world through the use of very basic geometry and, at

odds with Mayhew, a dream-like suspense of belief; Fanelli makes no attempt to say

that this is not just some bizarre, almost feverish fiction, whereas Mayhew wants you

to trust that this world and its characters are real. Thus, relating back to the narratives

intent to impart a lesson, Mayhews, then like a persistent schoolmaster is a story

that wants to be taken seriously with impactful gravitas, whereas Fanelli steers

towards a light-hearted,

playful nursery-like

atmosphere more

focused on nurturing

the imagination. An

example of this

disparity can be

observed below, by

contrasting the manner

in which both artists

have depicted the

moment that Pinocchio

becomes a real boy.

The image on the right

(Fig. 16) shows a detail

from a double-spread of

Fanellis, depicting a

collaged Pinocchio with

a giant, photographic

head, which cuts a very

bizarre figure. The

floral background and

the bold, zesty border

48

Nodelman, P. (1988) Words About Pictures: Georgia: University of Georgia Press [Pg. 78 / 88]

Fig. 16

Jack Taylor The Never-ending Appeal of the Forever-growing Nose

28

have an almost psychedelic vibe, and the cloud-like frame around the scene amplifies

the sensation of a dream: not only in the sense that the transformation is a dream

come true, but also that the entire story is a fantasy resonating with the childs

imagination.

Mayhew, however,

depicts a very

sentimental image

(Fig. 17), with a more

definitive frame to

give the story the

finality of closure or,

for the boy Pinocchio

at least, the gateway

to a new beginning.

Including the puppet

body (and the chair,

which implies setting)

makes it feel as

though the story

actually happened; we

are presented with

objects that suggest as

much. Being able to

observe the puppet

body objectively

serves as the proof.

However, it needs to

be said that the realistic tangibility of Mayhews depiction stems primarily from his

density of media, as suggested earlier, and not from the way in which his characters

are rendered; they, in fact, lean more heavily towards the realm of the cartoon. As

Scott McCloud demonstrates in Understanding Comics, the more a character has been

simplified to an iconic form, the more relatable that character inherently becomes:

Fig. 17

Fig. 18

Jack Taylor The Never-ending Appeal of the Forever-growing Nose

29

If you take another look at Pinocchio as drawn by Mayhew, paying particular

attention towards the simple iconography of the face McCloud describes in Fig. 18

above, you will notice that the characters features conform to this theory; two large,

dot-like eyes, a simple mouththis use of almost generic simplicity, which converges

towards gender-neutrality, aids in our collective relatability to a storys protagonist.

This is why we can still feel a connection towards Mayhews character despite the

sense of objectivity projected by his backgrounds, which attempt to consume its

inhabitants. Perry Nodelman explains this particular phenomenon:

The characters inchildrens books must show us[how] peoplemove and talk

and think and feel. So their faces and bodies usually have the simplicity, and

consequently the expressiveness, of cartooning, a simplicity at variance from the

frequent richness and detailed accuracy of their backgrounds, which give us a

different sort of narrative information.

49

This is not to say that Fanellis Pinocchio isnt relatable in a similar way; far from it.

There are many different devices that can be employed in order to afford characters a

sense of identity; in this instance, it pertains to the usage of a collaged human eye. We

identify with the icon of the human eye just as much as we identify with the icon of

the simplified human face; they are both symbolic of the human consciousness, and

therefore we pay particular attention to images which exhibit these attributes. An

important technique, then, because of how important it is that we feel an affinity

towards the main character, who is, generally speaking, not only at first otherwise

dislikeable, but also the primary constant throughout all featured images.

3.4 Illustrating the Puppet A Comparison

Now that the styles and sensibilities of both artists have been established, it is worth

studying how using their two very different styles both Mayhew and Fanelli have

illustrated particular instances of the narrative, and whether or not any comparisons

can be drawn about the approaches they have used whilst depicting the same scene.

49

Nodelman, P. (1988) Words About Pictures: Georgia: University of Georgia Press [Pg. 99 / 100]

Fig. 19

Jack Taylor The Never-ending Appeal of the Forever-growing Nose

30

Here, we see how both Fanelli (Fig. 19) and Mayhew (Fig. 20) have visualised the

scene in which Pinocchio is accosted by the Showman, named Fire-eater. Despite the

differing styles, both images do, in fact, use a number of common devices and draw

importance to similar elements. Particular attention seems to have been given to Fire-

eaters beard, which was like black ink...so long that it reached the ground

50

- this

becomes a central element. Another thing the images have in common is the use of

scale to render Pinocchio diminutive and Fire-eater as an imposing goliath:

The sizes of various objectsinfluence the way we understand [their] relationship

The tendency of large figures to dominate is useful in story situations involving

small creatures threatened by large ones.

51

Juxtaposing scale in this manner helps us to

further identify with Pinocchio in the imagery,

as we as the audience can share in the terror of

being confronted by these daunting, threatening

characters; they overwhelm the space of a page

and command our attention

Notably, both images also use a similar palette;

a dominant red background as well as orange

accents.

Artists can evoke particular moods by using

the appropriate colours[their] emotional

implicationsare particularly clear in

[pictures] in which one colour

predominates.

52

The artists, perceptibly, have chosen red to

symbolise anger and danger; to instil fear. The

orange may not carry similar connotations, but

the usage of it that is to say, of warm colours

carries the impact of the red throughout by

creating a sense of coherent mood lighting. In

this manner, the malevolence can be traced

back to Fire-eater and is thus attributable to

him; in Mayhews image the redness appears to

emanate from him, and in Fanellis image he

appears to coexist with it, via the

aforementioned association with warm colours.

A device that Mayhew uses that Fanelli does

not, however, is the use of shadow, particularly

that which is protruding from Fire-eaters boot,

which seems to cement him within the frame of

the picture and enhance his tall and commanding form:

50

Collodi, C. and Harden, E. (1882) Pinocchio: Australia: Consolidated Press [Pg. 42]

51

Nodelman, P. (1988) Words About Pictures: Georgia: University of Georgia Press [Pg. 128]

52

Nodelman, P. (1988) Words About Pictures: Georgia: University of Georgia Press [Pg. 60]

Fig. 20

Jack Taylor The Never-ending Appeal of the Forever-growing Nose

31

Shadows tend to suggest the power of the objects that cast them over the objects they

overlapthey usually appear only when illustrators need them to symbolise

something.

53

This technique goes hand-in-hand with the contrast of scale, as Fire-eater fills more of

the picture two whole edges and therefore appears to wield dominion over it the

other characters are merely encroaching on his space.

Shadows aside, for all intents and purposes the two images have largely been

conducted reasonably like-mindedly; in fact, both Fanelli and Mayhew have chosen to

illustrate a number of the major scenes throughout the book in a similarly equivalent

manner. Below are the artists illustrations for Pinocchios trial with the stern-looking

monkey judge; one may readily notice how the

same visual techniques described above also

come into play here.

The images have employed contrast of scale

again, this time to elevate the judges authority

against Pinocchios down-trodden role as the

accused; Fanellis image in particular (Fig. 21) is

especially daunting with its enlarged head and

penetrating gaze.

Oddly, there is also a jointly perceptible use of yellow, a colour generally used to

symbolise hope or happiness.

54

However, yellow is also used to embody cowardice,

53

Nodelman, P. (1988) Words About Pictures: Georgia: University of Georgia Press [Pg. 153]

Fig. 21 Fig. 22

Jack Taylor The Never-ending Appeal of the Forever-growing Nose

32

or perhaps the most relevant connotation in this situation to symbolise the giving

of caution or a warning; since the use of yellow is muted, it is much more sombre and

therefore less likely to derive from, and therefore be confused with, a more light-

hearted meaning.

One possible issue with Fanellis monkey is that, out of context, one may not be able

to correctly identify the characters occupation as a judge; it is missing much of the

iconography we traditionally associate with men of law, the judges wig and gavel

being the most significant; their absence is exacerbated when comparing the image to

Mayhews (Fig. 22) Pinocchio may just as well be pleading for a loan to Fanellis

angry monkey bank-manager, as the quill and inkwell do nothing to confirm his

position as judge. In this sense, Fanelli has, perhaps, overlooked one of the most

fundamental rules of illustration:

Illustratorsmust assume that their purpose is to provide visual information [such

as]settings and clothing that [are] not merely historically or sociologically

accurate but also almost always symbolic of atmosphere or character.

55

Whilst the above is true, it is also worth bearing in mind that when the image is given

context, the idea that the character is a judge is already a known quality. Fanelli is

therefore offering a manner of non-parallel information to the text, giving greater

concern to expression and action than to detail or description; things that the text is

designed to carry instead. This seems to fall in line with her pursuit for unique

abstraction, affording a looser and less constrained insight that previous illustrators

who adhered more closely to the text perhaps could not; continually freshening up the

portrayal of the story and its characters is, of course, important in the long term.

The following three pages present a brief overview of observed similarities between a

number of other notable scenes (left, Mayhew; right, Fanelli).

54

The connections between blue and melancholy, yellow and happiness, red and warmthappear to

derive fairly directly from our basic perceptions of water and sunlight and fire. Nodelman, P.

(1988) Words About Pictures: Georgia: University of Georgia Press [Pg. 60]

55

Nodelman, P. (1988) Words About Pictures: Georgia: University of Georgia Press [Pg. 82]

Jack Taylor The Never-ending Appeal of the Forever-growing Nose

33

In this scene, both artists have attempted to personify the piece of wood which

becomes Pinocchio by depicting it with its basic features, such as eyes and a nose.

They also both show Geppetto with his yellow wig, which looked very like a dish of

polenta

56

and depict him wearing white, which perhaps suggests purity and goodness

(supporting his role as a kindly father figure.) Since Mayhew shows Geppetto already

working on the puppet, the lighting and colour is hopeful and optimistic. The empty

darkness in Fanellis illustration is contemplative; Geppetto has yet to decide what to

do with the wood, and the image therefore has a sense of mystery.

56

Collodi, C. and Harden, E. (1882) Pinocchio: Australia: Consolidated Press [Pg. 9]

Fig. 23 Fig. 24

Jack Taylor The Never-ending Appeal of the Forever-growing Nose

34

Here, the serpent frightens Pinocchio, making

him fall down on his head. The composition of

both images is similar, showing the serpent

outstretched and towering above Pinocchio to the

right, with the puppet upturned in the lower-left.

Both artists have made the column of smoke

coming from [its] tail

57

a minor element which

emanates from the lower-right, instead giving

greater focus to Pinocchios reaction. As

established earlier in this essay, placing Pinocchio on the left in this manner implies

his impeded progress. Although both serpents possess fantastical elements, as

expected Fanellis design is more imaginative; Mayhews is closest to our real-world

perception of a snake.

57

Collodi, C. and Harden, E. (1882) Pinocchio: Australia: Consolidated Press [Pg. 88]

Fig. 25 Fig. 26

Jack Taylor The Never-ending Appeal of the Forever-growing Nose

35

Pinocchios meeting with Mr. Fish the dolphin is

visualised incredibly similarly by both artists, the

primary difference being Mayhews standard

vertical composition. Both imply a small snapshot

of a greater ocean by using vague edges around

the water, but only Mayhew suggests the same of

the island; Pinocchio looks as though hes

deserted in Fanellis image. Fanelli, however,

further personifies the character of Mr. Fish by

giving him a hat, thus perpetuating her penchant

for visual absurdity.

By observing the examples above, it is apparent that both artists have conveyed key

information presented in the text almost identically, with the core differentiating

factor being their intrinsic stylistic approach. As identified earlier in this chapter, this

is likely down to each artists personal resonance with the text the solidly realistic

and scientifically objective approach by Mayhew at odds with the bizarrely

fantastical, imaginative and mysterious approach by Fanelli with both being a

perfectly viable solution to the same problem. In other words, both illustrators are

merely serving a different flavour of Pinocchio; one which will resonate with

audiences with differing tastes, thus contributing to the universal and continued

appeal of the story a healthy thing indeed.

Fig. 27 Fig. 28

Jack Taylor The Never-ending Appeal of the Forever-growing Nose

36

CHAPTER 4

The Repurposing of the Puppet

The following chapter will attempt to briefly investigate the success of Pinocchios

translation to another media, specifically animation, via observation of illustrative

devices for characterisation.

Just how well does such a classic story transcend beyond its original context? If

Bettelheim is to be believed, this process is, in fact, anything but successful:

Most children now meet fairy tales only in prettified and simplified versions which

subdue their meaning and rob them of all deeper significance versions such as those

on films and TV shows, where fairy tales are turned into empty-minded

entertainment.

58

This opinion shall be attested by evaluating said filmic representation. Chiefly, the

1940 Walt Disney version shall be examined; the devices it has used in order to revise

the essence of the original story shall be broken down along with the illustrative

techniques it may have employed to convey meaning. This will be supplemented by

comparisons to another filmic version by Golden Films released in 1992.

4.1 The Problem with the Puppet

The Disney version of Pinocchio appears to be so ingrained in the peoples

conscience that many, in fact, often mistake it for the original version of the story.

This makes it an interesting interpretation to study, as, in many ways, a great deal of

artistic license had been had in the treatment of the source material, and in some

regards the tale is thematically at odds with the original; indeed, the largest deviation

is possibly the characterisation of Pinocchio himself.

As alluded to throughout this essay, Pinocchio is traditionally a very impish character,

and the plot of the story focuses much on his development into a more compassionate

individual. However, these attributes would soon pose problems during the process of

conveying the puppet to the big screen. Disney animator Ollie Johnston speaks about

how important it was for the whole family to be able to empathise with Pinocchios

dilemmas:

The audience [had] to be able to identify with [Pinocchio] like you would your own

kidhe had to choose between right and wrong and had a lot of trouble doing

that;something that people could see their own kids doing, and understand from

this picture;[Walt] wanted Pinocchio to bebelievable rather than just a

puppet.

59

58

Bettelheim, B. (1976) The Uses of Enchantment: Great Britain: Thames and Hudson [Pg. 24]

59

Johnston O. (2009) (audio commentary from Disney, W. and Sharpsteen, B. (1940) Pinocchio [BD]:

Walt Disney)

Jack Taylor The Never-ending Appeal of the Forever-growing Nose

37

Initially, the team had played with

the idea of retaining Pinocchios

rambunctious demeanour, even

going so far as to suggest that the

character be directly influenced by

Edgar Bergens sharp-tongued

dummy Charlie McCarthy, due to

his popularity at the time

60

; it was

decided, however, to produce their

own, similar character, but this

was met by opposition by Walt

part-way through development:

After about six or eight months

Walt looked at [our progress] and

said, stop working on

iteverybody had to start over

againthats when we begin to

develop the part of the cricket as

Pinocchios conscience; that was

the key to making that picture

work!

61

As this quote by director of animation, Ward Kimball, suggests, remaining faithful to

the original narrative actually hindered progress with the feature, as it was missing

key ingredients that would allow the story to translate coherently. One of these

ingredients was the necessary interactivity between Pinocchio and the character

eventually known as Jiminy this relationship would have been absent in the storys

original context, as Pinocchio squashes the cricket; the cricket is a minor character;

hey Pinoc, you shouldnt be-SPLFFFT hes gone in about two seconds flat!

62

To

fully appreciate the way in which the story was engineered for the screen, it is

pertinent to henceforth evaluate the expanded role of the cricket, and why the

dependence on the development of this character was so essential.

4.2 Pinocchios Official Conscience

It is important to realise that the side-character of the cricket in Walt Disneys version

has been promoted all the way up to secondary protagonist, becoming an intrinsic

main focus and even gaining his own underlying sub-plot. Nowadays, Jiminy seems

to have earned much more star power and lasting appeal than Disneys Pinocchio

60

[In] the original story [Pinocchio] was not innocent at all; he didnt know anything but he was a

real smart-alecthats where we started outone of [the] directors [said], well, why dont we just use

[Edgar] Bergens voice and base the character on Charlie McCarthy? Hes popular, we know what to

do with im, we know the gags hes good at; but the rest of em said, no, lets get our own [puppet]!

Thomas, F. (2009) (audio commentary from Disney, W. and Sharpsteen, B. (1940) Pinocchio [BD]:

Walt Disney)

61

Kimball, W. (2009) (audio commentary from Disney, W. and Sharpsteen, B. (1940) Pinocchio [BD]:

Walt Disney)

62

Maltin L., Goldberg E. and Kaufmann, J. (2009) (audio commentary from Disney, W. and

Sharpsteen, B. (1940) Pinocchio [BD]: Walt Disney)

Fig. 29

Jack Taylor The Never-ending Appeal of the Forever-growing Nose

38

himself and the root of this popularity becomes readily apparent during the film;

Jiminy takes precedence over Pinocchio in some scenes, and serves as a sort of comic

relief character; he appears slightly bumbling and not entirely efficient at his job at

being Pinocchios conscience:

Jiminy really is the lynch-pin for [the] film, because hes not only the narratorbut

kind of the glue, that holds the whole story together. He also serves as the comedy-

relief; even at the most serious moments hes there kind of making his wise-guy

comments, and that keeps the tone light.

63

A great example of Jiminy acting as the storys glue is that he is a perfect device for

visually (and audibly) symbolising Pinocchios conflicting thoughts; to make up for

an animations lack of accompanying

omniscient text, Jiminy brings the

voice of reason without the narrative

having to physically enter Pinocchios

own head:

We tend to regard Jiminy as the first

and best sidekick character in Disney

films, because he also serves the

function of being a mentorPinocchio

is tempted all the time and Jiminys the

guy who keeps him on the straight-and-

narrow.

64

This role of mentor is significant as it complements the shift in Pinocchios own

personality to one who is nave more than he is naughty; this is amplified by Dickie

Jones vocal work, [which] really got the innocencebut in a charming way; he