Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

TIWC Sample

Transféré par

astefCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

TIWC Sample

Transféré par

astefDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

S

P

A

N

I

S

H

H

O

R

R

O

R

F

I

L

M

L

o

r

e

m

ip

s

u

m

d

o

lo

r

s

it

a

m

e

t,

c

o

n

s

e

c

te

tu

e

r

a

d

ip

is

c

in

g

e

lit,

s

e

d

d

ia

m

n

o

n

u

m

m

y

n

ib

h

e

u

is

m

o

d

tin

-

c

id

u

n

t u

t la

o

r

e

e

t d

o

lo

r

e

m

a

g

n

a

a

liq

u

a

m

e

r

a

t v

o

lu

tp

a

t.

U

t w

is

i e

n

im

a

d

m

in

im

v

e

n

ia

m

,

q

u

is

n

o

s

tr

u

d

e

x

e

r

c

i ta

tio

n

u

lla

m

c

o

r

p

e

r

s

u

s

c

ip

it lo

b

o

r

tis

n

is

l u

t a

liq

u

ip

e

x

e

a

c

o

m

m

o

d

o

c

o

n

s

e

q

u

a

t.

D

u

is

a

u

te

m

v

e

l e

u

m

ir

iu

r

e

d

o

lo

r

in

h

e

n

d

r

e

r

it in

v

u

lp

u

ta

te

v

e

lit e

s

s

e

m

o

le

s

tie

c

o

n

s

e

q

u

a

t,

v

e

l illu

m

d

o

lo

r

e

e

u

fe

u

g

ia

t n

u

lla

~

a

c

ilis

is

a

t v

e

r

o

e

r

o

s

e

t a

c

c

u

m

s

a

n

e

t iu

s

to

o

d

io

d

ig

n

is

s

im

q

u

i b

la

n

d

it p

r

a

e

-

s

e

n

t

lu

p

ta

tu

m

z

z

r

il

d

e

le

n

it

a

u

g

u

e

d

u

is

d

o

lo

r

e

te

fe

u

g

a

it

n

u

lla

fa

c

ilis

i.

L

o

r

e

m

ip

s

u

m

d

o

lo

r

s

it

a

m

e

t,

c

o

n

s

e

c

te

tu

e

r

a

d

ip

is

c

in

g

e

lit,

s

e

d

d

ia

m

n

o

n

u

m

m

y

n

ib

h

e

u

is

m

o

d

tin

c

id

u

n

t

u

t

la

o

r

e

e

t

d

o

lo

r

e

m

a

g

n

a

a

liq

u

a

m

e

r

a

t v

o

lu

tp

a

t.

U

t

w

is

i

e

n

im

a

d

m

in

im

v

e

n

ia

m

,

q

u

is

n

o

s

tr

u

d

e

x

e

r

c

i

ta

tio

n

u

lla

m

c

o

r

p

e

r

s

u

s

c

ip

it

lo

b

o

r

tis

n

is

l

u

t

a

liq

u

ip

e

x

e

a

c

o

m

m

o

d

o

c

o

n

s

e

q

u

a

t.

D

u

is

a

u

te

m

v

e

l e

u

m

ir

iu

r

e

d

o

lo

r

in

h

e

n

d

r

e

r

it in

v

u

lp

u

ta

te

v

e

lit

e

s

s

e

m

o

le

s

tie

c

o

n

s

e

q

u

a

t,

v

e

l illu

m

d

o

lo

r

e

e

u

fe

u

g

ia

t n

u

lla

fa

c

ilis

is

a

t v

e

r

o

e

r

o

s

e

t a

c

c

u

m

s

a

n

e

t iu

s

to

.

L

o

r

e

m

ip

s

u

m

d

o

lo

r

s

it

a

m

e

t,

c

o

n

s

e

c

te

tu

e

r

a

d

ip

is

c

in

g

e

lit,

s

e

d

d

ia

m

n

o

n

u

m

m

y

n

ib

h

e

u

is

m

o

d

tin

-

c

id

u

n

t u

t la

o

r

e

e

t d

o

lo

r

e

m

a

g

n

a

a

liq

u

a

m

e

r

a

t v

o

lu

tp

a

t.

U

t w

is

i e

n

im

a

d

m

in

im

v

e

n

ia

m

,

q

u

is

n

o

s

tr

u

d

e

x

e

r

c

i ta

tio

n

u

lla

m

c

o

r

p

e

r

s

u

s

c

ip

it lo

b

o

r

tis

n

is

l u

t a

liq

u

ip

e

x

e

a

c

o

m

m

o

d

o

c

o

n

s

e

q

u

a

t.

A

n

t

o

n

io

L

z

a

r

o

-R

e

b

o

ll

D

u

is

a

u

te

m

v

e

l

e

u

m

ir

iu

r

e

d

o

lo

r

in

h

e

n

d

r

e

r

it

in

v

u

lp

u

ta

te

v

e

lit

e

s

s

e

m

o

le

s

tie

c

o

n

s

e

q

u

a

t,

v

e

l illu

m

d

o

lo

r

e

e

u

fe

u

g

ia

t n

u

lla

~

a

c

ilis

is

a

t v

e

r

o

e

r

o

s

e

t

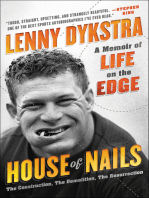

C

o

v

e

r

d

e

s

ig

n

:

R

iv

e

r

D

e

s

ig

n

,

E

d

in

b

u

r

g

h

Ja

c

k

e

t im

a

g

e

:

T

h

e

D

e

vils B

a

c

k

b

o

n

e

C

a

n

a

l+

E

s

p

a

n

a

/T

h

e

K

o

b

a

l C

o

lle

c

tio

n

E

d

in

b

u

r

g

h

U

n

iv

e

r

s

ity

P

re

s

s

2

2

G

e

o

r

g

e

S

q

u

a

re

,

E

d

in

b

u

r

g

h

E

H

8

9

L

F

w

w

w

.e

u

p

p

u

b

lis

h

in

g

.c

o

m

IS

B

N

0

7

4

8

6

3

6

3

8

9

A

N

T

O

N

I

O

L

Z

A

R

O

-

R

E

B

O

L

L

T

r

a

d

it

io

n

s

in

W

o

r

ld

C

in

e

m

a

S

e

r

ie

s

E

d

it

o

r

:

S

t

e

v

e

n

Ja

y

S

c

h

n

e

id

e

r

A

s

s

o

c

ia

t

e

E

d

it

o

r

s

:

L

in

d

a

B

a

d

le

y

a

n

d

R

.

B

a

r

t

o

n

P

a

lm

e

r

T

h

is

n

e

w

s

e

r

ie

s

in

tr

o

d

u

c

e

s

d

iv

e

r

s

e

a

n

d

fa

s

c

in

a

tin

g

m

o

v

e

m

e

n

ts

in

w

o

r

ld

c

in

e

m

a

.

E

a

c

h

v

o

lu

m

e

c

o

n

c

e

n

tr

a

te

s

o

n

a

s

e

t o

f film

s

fr

o

m

a

d

iffe

r

e

n

t n

a

tio

n

a

l o

r

r

e

g

io

n

a

l (in

s

o

m

e

c

a

s

e

s

c

r

o

s

s

-c

u

ltu

r

a

l)

c

in

e

m

a

w

h

ic

h

c

o

n

s

titu

te

a

p

a

r

tic

u

la

r

tra

d

itio

n

.

V

o

lu

m

e

s

c

o

v

e

r

to

p

ic

s

s

u

c

h

a

s

:

Ja

p

a

n

e

s

e

h

o

r

r

o

r

c

in

e

m

a

,

Ita

lia

n

n

e

o

r

e

a

lis

t

c

in

e

m

a

,

A

m

e

r

ic

a

n

b

la

x

p

lo

ita

tio

n

c

in

e

m

a

,

A

fr

ic

a

n

film

m

a

k

in

g

,

g

lo

b

a

l

p

o

s

t-p

u

n

k

c

in

e

m

a

,

C

z

e

c

h

a

n

d

S

lo

v

a

k

c

in

e

m

a

a

n

d

th

e

Ita

lia

n

s

w

o

r

d

-a

n

d

-s

a

n

d

a

l film

.

Edinburgh

b

a

r

c

o

d

e

S

P

A

N

I

S

H

H

O

R

R

O

R

F

I

L

M

SPANISH HORROR FILM

A

N

T

O

N

I

O

L

Z

A

R

O

-

R

E

B

O

L

L

ANTONIO LZARO-REBOLL

TRADITIONS

IN WORLD

CINEMA

SAMPLER

Series Editors:

Linda Badley & R. Barton Palmer

This series introduces diverse and fascinating movements

in world cinema. Each volume concentrates on a set of flms

from a diferent national, regional or, in some cases, cross-

cultural cinema which constitute a particular tradition.

Volumes cover topics such as Japanese horror cinema, new

punk cinema, African cinema, Italian neorealism, Czech

and Slovak cinema and the Italian sword-and-sandal flm.

S

P

A

N

I

S

H

H

O

R

R

O

R

F

I

L

M

L

o

r

e

m

ip

s

u

m

d

o

lo

r

s

it

a

m

e

t,

c

o

n

s

e

c

te

tu

e

r

a

d

ip

is

c

in

g

e

lit,

s

e

d

d

ia

m

n

o

n

u

m

m

y

n

ib

h

e

u

is

m

o

d

tin

-

c

id

u

n

t u

t la

o

r

e

e

t d

o

lo

r

e

m

a

g

n

a

a

liq

u

a

m

e

r

a

t v

o

lu

tp

a

t.

U

t w

is

i e

n

im

a

d

m

in

im

v

e

n

ia

m

,

q

u

is

n

o

s

tr

u

d

e

x

e

r

c

i ta

tio

n

u

lla

m

c

o

r

p

e

r

s

u

s

c

ip

it lo

b

o

r

tis

n

is

l u

t a

liq

u

ip

e

x

e

a

c

o

m

m

o

d

o

c

o

n

s

e

q

u

a

t.

D

u

is

a

u

te

m

v

e

l

e

u

m

ir

iu

r

e

d

o

lo

r

in

h

e

n

d

r

e

r

it

in

v

u

lp

u

ta

te

v

e

lit

e

s

s

e

m

o

le

s

tie

c

o

n

s

e

q

u

a

t,

v

e

l

illu

m

d

o

lo

r

e

e

u

fe

u

g

ia

t n

u

lla

~

a

c

ilis

is

a

t v

e

r

o

e

r

o

s

e

t a

c

c

u

m

s

a

n

e

t iu

s

to

o

d

io

d

ig

n

is

s

im

q

u

i b

la

n

d

it p

r

a

e

-

s

e

n

t

lu

p

ta

tu

m

z

z

r

il

d

e

le

n

it

a

u

g

u

e

d

u

is

d

o

lo

r

e

te

fe

u

g

a

it

n

u

lla

fa

c

ilis

i.

L

o

r

e

m

ip

s

u

m

d

o

lo

r

s

it

a

m

e

t,

c

o

n

s

e

c

te

tu

e

r

a

d

ip

is

c

in

g

e

lit,

s

e

d

d

ia

m

n

o

n

u

m

m

y

n

ib

h

e

u

is

m

o

d

tin

c

id

u

n

t

u

t

la

o

r

e

e

t

d

o

lo

r

e

m

a

g

n

a

a

liq

u

a

m

e

r

a

t v

o

lu

tp

a

t.

U

t

w

is

i

e

n

im

a

d

m

in

im

v

e

n

ia

m

,

q

u

is

n

o

s

tr

u

d

e

x

e

r

c

i

ta

tio

n

u

lla

m

c

o

r

p

e

r

s

u

s

c

ip

it

lo

b

o

r

tis

n

is

l

u

t

a

liq

u

ip

e

x

e

a

c

o

m

m

o

d

o

c

o

n

s

e

q

u

a

t.

D

u

is

a

u

te

m

v

e

l e

u

m

ir

iu

r

e

d

o

lo

r

in

h

e

n

d

r

e

r

it in

v

u

lp

u

ta

te

v

e

lit

e

s

s

e

m

o

le

s

tie

c

o

n

s

e

q

u

a

t,

v

e

l illu

m

d

o

lo

r

e

e

u

fe

u

g

ia

t n

u

lla

fa

c

ilis

is

a

t v

e

r

o

e

r

o

s

e

t a

c

c

u

m

s

a

n

e

t iu

s

to

.

L

o

r

e

m

ip

s

u

m

d

o

lo

r

s

it

a

m

e

t,

c

o

n

s

e

c

te

tu

e

r

a

d

ip

is

c

in

g

e

lit,

s

e

d

d

ia

m

n

o

n

u

m

m

y

n

ib

h

e

u

is

m

o

d

tin

-

c

id

u

n

t u

t la

o

r

e

e

t d

o

lo

r

e

m

a

g

n

a

a

liq

u

a

m

e

r

a

t v

o

lu

tp

a

t.

U

t w

is

i e

n

im

a

d

m

in

im

v

e

n

ia

m

,

q

u

is

n

o

s

tr

u

d

e

x

e

r

c

i ta

tio

n

u

lla

m

c

o

r

p

e

r

s

u

s

c

ip

it lo

b

o

r

tis

n

is

l u

t a

liq

u

ip

e

x

e

a

c

o

m

m

o

d

o

c

o

n

s

e

q

u

a

t.

A

n

t

o

n

io

L

z

a

r

o

-R

e

b

o

ll

D

u

is

a

u

te

m

v

e

l

e

u

m

ir

iu

r

e

d

o

lo

r

in

h

e

n

d

r

e

r

it

in

v

u

lp

u

ta

te

v

e

lit

e

s

s

e

m

o

le

s

tie

c

o

n

s

e

q

u

a

t,

v

e

l illu

m

d

o

lo

r

e

e

u

fe

u

g

ia

t n

u

lla

~

a

c

ilis

is

a

t v

e

r

o

e

r

o

s

e

t

C

o

v

e

r

d

e

s

ig

n

:

R

iv

e

r

D

e

s

ig

n

,

E

d

in

b

u

r

g

h

Ja

c

k

e

t im

a

g

e

:

T

h

e

D

e

vils B

a

c

k

b

o

n

e

C

a

n

a

l+

E

s

p

a

n

a

/T

h

e

K

o

b

a

l C

o

lle

c

tio

n

E

d

in

b

u

r

g

h

U

n

iv

e

r

s

ity

P

re

s

s

2

2

G

e

o

r

g

e

S

q

u

a

re

,

E

d

in

b

u

r

g

h

E

H

8

9

L

F

w

w

w

.e

u

p

p

u

b

lis

h

in

g

.c

o

m

IS

B

N

0

7

4

8

6

3

6

3

8

9

A

N

T

O

N

I

O

L

Z

A

R

O

-

R

E

B

O

L

L

T

r

a

d

it

io

n

s

in

W

o

r

ld

C

in

e

m

a

S

e

r

ie

s

E

d

it

o

r

:

S

t

e

v

e

n

Ja

y

S

c

h

n

e

id

e

r

A

s

s

o

c

ia

t

e

E

d

it

o

r

s

:

L

in

d

a

B

a

d

le

y

a

n

d

R

.

B

a

r

t

o

n

P

a

lm

e

r

T

h

is

n

e

w

s

e

r

ie

s

in

tr

o

d

u

c

e

s

d

iv

e

r

s

e

a

n

d

fa

s

c

in

a

tin

g

m

o

v

e

m

e

n

ts

in

w

o

r

ld

c

in

e

m

a

.

E

a

c

h

v

o

lu

m

e

c

o

n

c

e

n

tr

a

te

s

o

n

a

s

e

t o

f film

s

fr

o

m

a

d

iffe

r

e

n

t n

a

tio

n

a

l o

r

r

e

g

io

n

a

l (in

s

o

m

e

c

a

s

e

s

c

r

o

s

s

-c

u

ltu

r

a

l)

c

in

e

m

a

w

h

ic

h

c

o

n

s

titu

te

a

p

a

r

tic

u

la

r

tra

d

itio

n

.

V

o

lu

m

e

s

c

o

v

e

r

to

p

ic

s

s

u

c

h

a

s

:

Ja

p

a

n

e

s

e

h

o

r

r

o

r

c

in

e

m

a

,

Ita

lia

n

n

e

o

r

e

a

lis

t

c

in

e

m

a

,

A

m

e

r

ic

a

n

b

la

x

p

lo

ita

tio

n

c

in

e

m

a

,

A

fr

ic

a

n

film

m

a

k

in

g

,

g

lo

b

a

l

p

o

s

t-p

u

n

k

c

in

e

m

a

,

C

z

e

c

h

a

n

d

S

lo

v

a

k

c

in

e

m

a

a

n

d

th

e

Ita

lia

n

s

w

o

r

d

-a

n

d

-s

a

n

d

a

l film

.

Edinburgh

b

a

r

c

o

d

e

S

P

A

N

I

S

H

H

O

R

R

O

R

F

I

L

M

SPANISH HORROR FILM

A

N

T

O

N

I

O

L

Z

A

R

O

-

R

E

B

O

L

L

ANTONIO LZARO-REBOLL

S

P

A

N

I

S

H

H

O

R

R

O

R

F

I

L

M

L

o

r

e

m

ip

s

u

m

d

o

lo

r

s

it

a

m

e

t,

c

o

n

s

e

c

te

tu

e

r

a

d

ip

is

c

in

g

e

lit,

s

e

d

d

ia

m

n

o

n

u

m

m

y

n

ib

h

e

u

is

m

o

d

tin

-

c

id

u

n

t u

t la

o

r

e

e

t d

o

lo

r

e

m

a

g

n

a

a

liq

u

a

m

e

r

a

t v

o

lu

tp

a

t.

U

t w

is

i e

n

im

a

d

m

in

im

v

e

n

ia

m

,

q

u

is

n

o

s

tr

u

d

e

x

e

r

c

i ta

tio

n

u

lla

m

c

o

r

p

e

r

s

u

s

c

ip

it lo

b

o

r

tis

n

is

l u

t a

liq

u

ip

e

x

e

a

c

o

m

m

o

d

o

c

o

n

s

e

q

u

a

t.

D

u

is

a

u

te

m

v

e

l e

u

m

ir

iu

r

e

d

o

lo

r

in

h

e

n

d

r

e

r

it in

v

u

lp

u

ta

te

v

e

lit e

s

s

e

m

o

le

s

tie

c

o

n

s

e

q

u

a

t,

v

e

l illu

m

d

o

lo

r

e

e

u

fe

u

g

ia

t n

u

lla

~

a

c

ilis

is

a

t v

e

r

o

e

r

o

s

e

t a

c

c

u

m

s

a

n

e

t iu

s

to

o

d

io

d

ig

n

is

s

im

q

u

i b

la

n

d

it p

r

a

e

-

s

e

n

t

lu

p

ta

tu

m

z

z

r

il

d

e

le

n

it

a

u

g

u

e

d

u

is

d

o

lo

r

e

te

fe

u

g

a

it

n

u

lla

fa

c

ilis

i.

L

o

r

e

m

ip

s

u

m

d

o

lo

r

s

it

a

m

e

t,

c

o

n

s

e

c

te

tu

e

r

a

d

ip

is

c

in

g

e

lit,

s

e

d

d

ia

m

n

o

n

u

m

m

y

n

ib

h

e

u

is

m

o

d

tin

c

id

u

n

t

u

t

la

o

r

e

e

t

d

o

lo

r

e

m

a

g

n

a

a

liq

u

a

m

e

r

a

t v

o

lu

tp

a

t.

U

t

w

is

i

e

n

im

a

d

m

in

im

v

e

n

ia

m

,

q

u

is

n

o

s

tr

u

d

e

x

e

r

c

i

ta

tio

n

u

lla

m

c

o

r

p

e

r

s

u

s

c

ip

it

lo

b

o

r

tis

n

is

l

u

t

a

liq

u

ip

e

x

e

a

c

o

m

m

o

d

o

c

o

n

s

e

q

u

a

t.

D

u

is

a

u

te

m

v

e

l e

u

m

ir

iu

r

e

d

o

lo

r

in

h

e

n

d

r

e

r

it in

v

u

lp

u

ta

te

v

e

lit

e

s

s

e

m

o

le

s

tie

c

o

n

s

e

q

u

a

t,

v

e

l illu

m

d

o

lo

r

e

e

u

fe

u

g

ia

t n

u

lla

fa

c

ilis

is

a

t v

e

r

o

e

r

o

s

e

t a

c

c

u

m

s

a

n

e

t iu

s

to

.

L

o

r

e

m

ip

s

u

m

d

o

lo

r

s

it

a

m

e

t,

c

o

n

s

e

c

te

tu

e

r

a

d

ip

is

c

in

g

e

lit,

s

e

d

d

ia

m

n

o

n

u

m

m

y

n

ib

h

e

u

is

m

o

d

tin

-

c

id

u

n

t u

t la

o

r

e

e

t d

o

lo

r

e

m

a

g

n

a

a

liq

u

a

m

e

r

a

t v

o

lu

tp

a

t.

U

t w

is

i e

n

im

a

d

m

in

im

v

e

n

ia

m

,

q

u

is

n

o

s

tr

u

d

e

x

e

r

c

i ta

tio

n

u

lla

m

c

o

r

p

e

r

s

u

s

c

ip

it lo

b

o

r

tis

n

is

l u

t a

liq

u

ip

e

x

e

a

c

o

m

m

o

d

o

c

o

n

s

e

q

u

a

t.

A

n

t

o

n

io

L

z

a

r

o

-R

e

b

o

ll

D

u

is

a

u

te

m

v

e

l

e

u

m

ir

iu

r

e

d

o

lo

r

in

h

e

n

d

r

e

r

it

in

v

u

lp

u

ta

te

v

e

lit

e

s

s

e

m

o

le

s

tie

c

o

n

s

e

q

u

a

t,

v

e

l illu

m

d

o

lo

r

e

e

u

fe

u

g

ia

t n

u

lla

~

a

c

ilis

is

a

t v

e

r

o

e

r

o

s

e

t

C

o

v

e

r

d

e

s

ig

n

:

R

iv

e

r

D

e

s

ig

n

,

E

d

in

b

u

r

g

h

Ja

c

k

e

t im

a

g

e

:

T

h

e

D

e

vils B

a

c

k

b

o

n

e

C

a

n

a

l+

E

s

p

a

n

a

/T

h

e

K

o

b

a

l C

o

lle

c

tio

n

E

d

in

b

u

r

g

h

U

n

iv

e

r

s

ity

P

re

s

s

2

2

G

e

o

r

g

e

S

q

u

a

re

,

E

d

in

b

u

r

g

h

E

H

8

9

L

F

w

w

w

.e

u

p

p

u

b

lis

h

in

g

.c

o

m

IS

B

N

0

7

4

8

6

3

6

3

8

9

A

N

T

O

N

I

O

L

Z

A

R

O

-

R

E

B

O

L

L

T

r

a

d

it

io

n

s

in

W

o

r

ld

C

in

e

m

a

S

e

r

ie

s

E

d

it

o

r

:

S

t

e

v

e

n

Ja

y

S

c

h

n

e

id

e

r

A

s

s

o

c

ia

t

e

E

d

it

o

r

s

:

L

in

d

a

B

a

d

le

y

a

n

d

R

.

B

a

r

t

o

n

P

a

lm

e

r

T

h

is

n

e

w

s

e

r

ie

s

in

tr

o

d

u

c

e

s

d

iv

e

r

s

e

a

n

d

fa

s

c

in

a

tin

g

m

o

v

e

m

e

n

ts

in

w

o

r

ld

c

in

e

m

a

.

E

a

c

h

v

o

lu

m

e

c

o

n

c

e

n

tr

a

te

s

o

n

a

s

e

t o

f film

s

fr

o

m

a

d

iffe

r

e

n

t n

a

tio

n

a

l o

r

r

e

g

io

n

a

l (in

s

o

m

e

c

a

s

e

s

c

r

o

s

s

-c

u

ltu

r

a

l)

c

in

e

m

a

w

h

ic

h

c

o

n

s

titu

te

a

p

a

r

tic

u

la

r

tra

d

itio

n

.

V

o

lu

m

e

s

c

o

v

e

r

to

p

ic

s

s

u

c

h

a

s

:

Ja

p

a

n

e

s

e

h

o

r

r

o

r

c

in

e

m

a

,

Ita

lia

n

n

e

o

r

e

a

lis

t

c

in

e

m

a

,

A

m

e

r

ic

a

n

b

la

x

p

lo

ita

tio

n

c

in

e

m

a

,

A

fr

ic

a

n

film

m

a

k

in

g

,

g

lo

b

a

l

p

o

s

t-p

u

n

k

c

in

e

m

a

,

C

z

e

c

h

a

n

d

S

lo

v

a

k

c

in

e

m

a

a

n

d

th

e

Ita

lia

n

s

w

o

r

d

-a

n

d

-s

a

n

d

a

l film

.

Edinburgh

b

a

r

c

o

d

e

S

P

A

N

I

S

H

H

O

R

R

O

R

F

I

L

M

SPANISH HORROR FILM

A

N

T

O

N

I

O

L

Z

A

R

O

-

R

E

B

O

L

L

ANTONIO LZARO-REBOLL

S

P

A

N

I

S

H

H

O

R

R

O

R

F

I

L

M

L

o

r

e

m

ip

s

u

m

d

o

lo

r

s

it

a

m

e

t,

c

o

n

s

e

c

te

tu

e

r

a

d

ip

is

c

in

g

e

lit,

s

e

d

d

ia

m

n

o

n

u

m

m

y

n

ib

h

e

u

is

m

o

d

tin

-

c

id

u

n

t u

t la

o

r

e

e

t d

o

lo

r

e

m

a

g

n

a

a

liq

u

a

m

e

r

a

t v

o

lu

tp

a

t.

U

t w

is

i e

n

im

a

d

m

in

im

v

e

n

ia

m

,

q

u

is

n

o

s

tr

u

d

e

x

e

r

c

i ta

tio

n

u

lla

m

c

o

r

p

e

r

s

u

s

c

ip

it lo

b

o

r

tis

n

is

l u

t a

liq

u

ip

e

x

e

a

c

o

m

m

o

d

o

c

o

n

s

e

q

u

a

t.

D

u

is

a

u

te

m

v

e

l

e

u

m

ir

iu

r

e

d

o

lo

r

in

h

e

n

d

r

e

r

it

in

v

u

lp

u

ta

te

v

e

lit

e

s

s

e

m

o

le

s

tie

c

o

n

s

e

q

u

a

t,

v

e

l

illu

m

d

o

lo

r

e

e

u

fe

u

g

ia

t n

u

lla

~

a

c

ilis

is

a

t v

e

r

o

e

r

o

s

e

t a

c

c

u

m

s

a

n

e

t iu

s

to

o

d

io

d

ig

n

is

s

im

q

u

i b

la

n

d

it p

r

a

e

-

s

e

n

t

lu

p

ta

tu

m

z

z

r

il

d

e

le

n

it

a

u

g

u

e

d

u

is

d

o

lo

r

e

te

fe

u

g

a

it

n

u

lla

fa

c

ilis

i.

L

o

r

e

m

ip

s

u

m

d

o

lo

r

s

it

a

m

e

t,

c

o

n

s

e

c

te

tu

e

r

a

d

ip

is

c

in

g

e

lit,

s

e

d

d

ia

m

n

o

n

u

m

m

y

n

ib

h

e

u

is

m

o

d

tin

c

id

u

n

t

u

t

la

o

r

e

e

t

d

o

lo

r

e

m

a

g

n

a

a

liq

u

a

m

e

r

a

t v

o

lu

tp

a

t.

U

t

w

is

i

e

n

im

a

d

m

in

im

v

e

n

ia

m

,

q

u

is

n

o

s

tr

u

d

e

x

e

r

c

i

ta

tio

n

u

lla

m

c

o

r

p

e

r

s

u

s

c

ip

it

lo

b

o

r

tis

n

is

l

u

t

a

liq

u

ip

e

x

e

a

c

o

m

m

o

d

o

c

o

n

s

e

q

u

a

t.

D

u

is

a

u

te

m

v

e

l e

u

m

ir

iu

r

e

d

o

lo

r

in

h

e

n

d

r

e

r

it in

v

u

lp

u

ta

te

v

e

lit

e

s

s

e

m

o

le

s

tie

c

o

n

s

e

q

u

a

t,

v

e

l illu

m

d

o

lo

r

e

e

u

fe

u

g

ia

t n

u

lla

fa

c

ilis

is

a

t v

e

r

o

e

r

o

s

e

t a

c

c

u

m

s

a

n

e

t iu

s

to

.

L

o

r

e

m

ip

s

u

m

d

o

lo

r

s

it

a

m

e

t,

c

o

n

s

e

c

te

tu

e

r

a

d

ip

is

c

in

g

e

lit,

s

e

d

d

ia

m

n

o

n

u

m

m

y

n

ib

h

e

u

is

m

o

d

tin

-

c

id

u

n

t u

t la

o

r

e

e

t d

o

lo

r

e

m

a

g

n

a

a

liq

u

a

m

e

r

a

t v

o

lu

tp

a

t.

U

t w

is

i e

n

im

a

d

m

in

im

v

e

n

ia

m

,

q

u

is

n

o

s

tr

u

d

e

x

e

r

c

i ta

tio

n

u

lla

m

c

o

r

p

e

r

s

u

s

c

ip

it lo

b

o

r

tis

n

is

l u

t a

liq

u

ip

e

x

e

a

c

o

m

m

o

d

o

c

o

n

s

e

q

u

a

t.

A

n

t

o

n

io

L

z

a

r

o

-R

e

b

o

ll

D

u

is

a

u

te

m

v

e

l

e

u

m

ir

iu

r

e

d

o

lo

r

in

h

e

n

d

r

e

r

it

in

v

u

lp

u

ta

te

v

e

lit

e

s

s

e

m

o

le

s

tie

c

o

n

s

e

q

u

a

t,

v

e

l illu

m

d

o

lo

r

e

e

u

fe

u

g

ia

t n

u

lla

~

a

c

ilis

is

a

t v

e

r

o

e

r

o

s

e

t

C

o

v

e

r

d

e

s

ig

n

:

R

iv

e

r

D

e

s

ig

n

,

E

d

in

b

u

r

g

h

Ja

c

k

e

t im

a

g

e

:

T

h

e

D

e

vils B

a

c

k

b

o

n

e

C

a

n

a

l+

E

s

p

a

n

a

/T

h

e

K

o

b

a

l C

o

lle

c

tio

n

E

d

in

b

u

r

g

h

U

n

iv

e

r

s

ity

P

re

s

s

2

2

G

e

o

r

g

e

S

q

u

a

re

,

E

d

in

b

u

r

g

h

E

H

8

9

L

F

w

w

w

.e

u

p

p

u

b

lis

h

in

g

.c

o

m

IS

B

N

0

7

4

8

6

3

6

3

8

9

A

N

T

O

N

I

O

L

Z

A

R

O

-

R

E

B

O

L

L

T

r

a

d

it

io

n

s

in

W

o

r

ld

C

in

e

m

a

S

e

r

ie

s

E

d

it

o

r

:

S

t

e

v

e

n

Ja

y

S

c

h

n

e

id

e

r

A

s

s

o

c

ia

t

e

E

d

it

o

r

s

:

L

in

d

a

B

a

d

le

y

a

n

d

R

.

B

a

r

t

o

n

P

a

lm

e

r

T

h

is

n

e

w

s

e

r

ie

s

in

tr

o

d

u

c

e

s

d

iv

e

r

s

e

a

n

d

fa

s

c

in

a

tin

g

m

o

v

e

m

e

n

ts

in

w

o

r

ld

c

in

e

m

a

.

E

a

c

h

v

o

lu

m

e

c

o

n

c

e

n

tr

a

te

s

o

n

a

s

e

t o

f film

s

fr

o

m

a

d

iffe

r

e

n

t n

a

tio

n

a

l o

r

r

e

g

io

n

a

l (in

s

o

m

e

c

a

s

e

s

c

r

o

s

s

-c

u

ltu

r

a

l)

c

in

e

m

a

w

h

ic

h

c

o

n

s

titu

te

a

p

a

r

tic

u

la

r

tra

d

itio

n

.

V

o

lu

m

e

s

c

o

v

e

r

to

p

ic

s

s

u

c

h

a

s

:

Ja

p

a

n

e

s

e

h

o

r

r

o

r

c

in

e

m

a

,

Ita

lia

n

n

e

o

r

e

a

lis

t

c

in

e

m

a

,

A

m

e

r

ic

a

n

b

la

x

p

lo

ita

tio

n

c

in

e

m

a

,

A

fr

ic

a

n

film

m

a

k

in

g

,

g

lo

b

a

l

p

o

s

t-p

u

n

k

c

in

e

m

a

,

C

z

e

c

h

a

n

d

S

lo

v

a

k

c

in

e

m

a

a

n

d

th

e

Ita

lia

n

s

w

o

r

d

-a

n

d

-s

a

n

d

a

l film

.

Edinburgh

b

a

r

c

o

d

e

S

P

A

N

I

S

H

H

O

R

R

O

R

F

I

L

M

SPANISH HORROR FILM

A

N

T

O

N

I

O

L

Z

A

R

O

-

R

E

B

O

L

L

ANTONIO LZARO-REBOLL

CONTENTS

THE INTERNATIONAL MUSICAL, Edited by Corey Creekmur and Linda Mokdad

Chapter 8: Soviet Union by Richard Taylor

ITALIAN NEOREALIST CINEMA, by Torunn Haaland

Chapter 1: A Moment And A County

POST-BEUR CINEMA, by Will Higbee

Chapter 2: The (Magrebi-) French Connection: Diaspora Goes Mainstream

SPANISH HORROR FILM by Antonio Lzaro-Reboll

Chapter 1: The Spanish Horror Book: 196875

SAVE 15% off the books featured in this sample

Please call Macmillan Distribution Limited on +441256 329 242 and quote 6JG. Discount

available to individuals until 30 September 2014. P&P not included.

S

P

A

N

I

S

H

H

O

R

R

O

R

F

I

L

M

L

o

r

e

m

ip

s

u

m

d

o

lo

r

s

it

a

m

e

t,

c

o

n

s

e

c

te

tu

e

r

a

d

ip

is

c

in

g

e

lit,

s

e

d

d

ia

m

n

o

n

u

m

m

y

n

ib

h

e

u

is

m

o

d

tin

-

c

id

u

n

t u

t la

o

r

e

e

t d

o

lo

r

e

m

a

g

n

a

a

liq

u

a

m

e

r

a

t v

o

lu

tp

a

t.

U

t w

is

i e

n

im

a

d

m

in

im

v

e

n

ia

m

,

q

u

is

n

o

s

tr

u

d

e

x

e

r

c

i ta

tio

n

u

lla

m

c

o

r

p

e

r

s

u

s

c

ip

it lo

b

o

r

tis

n

is

l u

t a

liq

u

ip

e

x

e

a

c

o

m

m

o

d

o

c

o

n

s

e

q

u

a

t.

D

u

is

a

u

te

m

v

e

l e

u

m

ir

iu

r

e

d

o

lo

r

in

h

e

n

d

r

e

r

it in

v

u

lp

u

ta

te

v

e

lit e

s

s

e

m

o

le

s

tie

c

o

n

s

e

q

u

a

t,

v

e

l illu

m

d

o

lo

r

e

e

u

fe

u

g

ia

t n

u

lla

~

a

c

ilis

is

a

t v

e

r

o

e

r

o

s

e

t a

c

c

u

m

s

a

n

e

t iu

s

to

o

d

io

d

ig

n

is

s

im

q

u

i b

la

n

d

it p

r

a

e

-

s

e

n

t

lu

p

ta

tu

m

z

z

r

il

d

e

le

n

it

a

u

g

u

e

d

u

is

d

o

lo

r

e

te

fe

u

g

a

it

n

u

lla

fa

c

ilis

i.

L

o

r

e

m

ip

s

u

m

d

o

lo

r

s

it

a

m

e

t,

c

o

n

s

e

c

te

tu

e

r

a

d

ip

is

c

in

g

e

lit,

s

e

d

d

ia

m

n

o

n

u

m

m

y

n

ib

h

e

u

is

m

o

d

tin

c

id

u

n

t

u

t

la

o

r

e

e

t

d

o

lo

r

e

m

a

g

n

a

a

liq

u

a

m

e

r

a

t v

o

lu

tp

a

t.

U

t

w

is

i

e

n

im

a

d

m

in

im

v

e

n

ia

m

,

q

u

is

n

o

s

tr

u

d

e

x

e

r

c

i

ta

tio

n

u

lla

m

c

o

r

p

e

r

s

u

s

c

ip

it

lo

b

o

r

tis

n

is

l

u

t

a

liq

u

ip

e

x

e

a

c

o

m

m

o

d

o

c

o

n

s

e

q

u

a

t.

D

u

is

a

u

te

m

v

e

l e

u

m

ir

iu

r

e

d

o

lo

r

in

h

e

n

d

r

e

r

it in

v

u

lp

u

ta

te

v

e

lit

e

s

s

e

m

o

le

s

tie

c

o

n

s

e

q

u

a

t,

v

e

l illu

m

d

o

lo

r

e

e

u

fe

u

g

ia

t n

u

lla

fa

c

ilis

is

a

t v

e

r

o

e

r

o

s

e

t a

c

c

u

m

s

a

n

e

t iu

s

to

.

L

o

r

e

m

ip

s

u

m

d

o

lo

r

s

it

a

m

e

t,

c

o

n

s

e

c

te

tu

e

r

a

d

ip

is

c

in

g

e

lit,

s

e

d

d

ia

m

n

o

n

u

m

m

y

n

ib

h

e

u

is

m

o

d

tin

-

c

id

u

n

t u

t la

o

r

e

e

t d

o

lo

r

e

m

a

g

n

a

a

liq

u

a

m

e

r

a

t v

o

lu

tp

a

t.

U

t w

is

i e

n

im

a

d

m

in

im

v

e

n

ia

m

,

q

u

is

n

o

s

tr

u

d

e

x

e

r

c

i ta

tio

n

u

lla

m

c

o

r

p

e

r

s

u

s

c

ip

it lo

b

o

r

tis

n

is

l u

t a

liq

u

ip

e

x

e

a

c

o

m

m

o

d

o

c

o

n

s

e

q

u

a

t.

A

n

t

o

n

io

L

z

a

r

o

-R

e

b

o

ll

D

u

is

a

u

te

m

v

e

l

e

u

m

ir

iu

r

e

d

o

lo

r

in

h

e

n

d

r

e

r

it

in

v

u

lp

u

ta

te

v

e

lit

e

s

s

e

m

o

le

s

tie

c

o

n

s

e

q

u

a

t,

v

e

l illu

m

d

o

lo

r

e

e

u

fe

u

g

ia

t n

u

lla

~

a

c

ilis

is

a

t v

e

r

o

e

r

o

s

e

t

C

o

v

e

r

d

e

s

ig

n

:

R

iv

e

r

D

e

s

ig

n

,

E

d

in

b

u

r

g

h

Ja

c

k

e

t im

a

g

e

:

T

h

e

D

e

vils B

a

c

k

b

o

n

e

C

a

n

a

l+

E

s

p

a

n

a

/T

h

e

K

o

b

a

l C

o

lle

c

tio

n

E

d

in

b

u

r

g

h

U

n

iv

e

r

s

ity

P

re

s

s

2

2

G

e

o

r

g

e

S

q

u

a

re

,

E

d

in

b

u

r

g

h

E

H

8

9

L

F

w

w

w

.e

u

p

p

u

b

lis

h

in

g

.c

o

m

IS

B

N

0

7

4

8

6

3

6

3

8

9

A

N

T

O

N

I

O

L

Z

A

R

O

-

R

E

B

O

L

L

T

r

a

d

it

io

n

s

in

W

o

r

ld

C

in

e

m

a

S

e

r

ie

s

E

d

it

o

r

:

S

t

e

v

e

n

Ja

y

S

c

h

n

e

id

e

r

A

s

s

o

c

ia

t

e

E

d

it

o

r

s

:

L

in

d

a

B

a

d

le

y

a

n

d

R

.

B

a

r

t

o

n

P

a

lm

e

r

T

h

is

n

e

w

s

e

r

ie

s

in

tr

o

d

u

c

e

s

d

iv

e

r

s

e

a

n

d

fa

s

c

in

a

tin

g

m

o

v

e

m

e

n

ts

in

w

o

r

ld

c

in

e

m

a

.

E

a

c

h

v

o

lu

m

e

c

o

n

c

e

n

tr

a

te

s

o

n

a

s

e

t o

f film

s

fr

o

m

a

d

iffe

r

e

n

t n

a

tio

n

a

l o

r

r

e

g

io

n

a

l (in

s

o

m

e

c

a

s

e

s

c

r

o

s

s

-c

u

ltu

r

a

l)

c

in

e

m

a

w

h

ic

h

c

o

n

s

titu

te

a

p

a

r

tic

u

la

r

tra

d

itio

n

.

V

o

lu

m

e

s

c

o

v

e

r

to

p

ic

s

s

u

c

h

a

s

:

Ja

p

a

n

e

s

e

h

o

r

r

o

r

c

in

e

m

a

,

Ita

lia

n

n

e

o

r

e

a

lis

t

c

in

e

m

a

,

A

m

e

r

ic

a

n

b

la

x

p

lo

ita

tio

n

c

in

e

m

a

,

A

fr

ic

a

n

film

m

a

k

in

g

,

g

lo

b

a

l

p

o

s

t-p

u

n

k

c

in

e

m

a

,

C

z

e

c

h

a

n

d

S

lo

v

a

k

c

in

e

m

a

a

n

d

th

e

Ita

lia

n

s

w

o

r

d

-a

n

d

-s

a

n

d

a

l film

.

Edinburgh

b

a

r

c

o

d

e

S

P

A

N

I

S

H

H

O

R

R

O

R

F

I

L

M

SPANISH HORROR FILM

A

N

T

O

N

I

O

L

Z

A

R

O

-

R

E

B

O

L

L

ANTONIO LZARO-REBOLL

THE INTERNATIONAL

FILM MUSICAL

Edited by Corey Creekmur and Linda Mokdad

A Sample From Chapter 8: Soviet Union

by Richard Taylor

S

P

A

N

I

S

H

H

O

R

R

O

R

F

I

L

M

L

o

r

e

m

ip

s

u

m

d

o

lo

r

s

it

a

m

e

t,

c

o

n

s

e

c

te

tu

e

r

a

d

ip

is

c

in

g

e

lit,

s

e

d

d

ia

m

n

o

n

u

m

m

y

n

ib

h

e

u

is

m

o

d

tin

-

c

id

u

n

t u

t la

o

r

e

e

t d

o

lo

r

e

m

a

g

n

a

a

liq

u

a

m

e

r

a

t v

o

lu

tp

a

t.

U

t w

is

i e

n

im

a

d

m

in

im

v

e

n

ia

m

,

q

u

is

n

o

s

tr

u

d

e

x

e

r

c

i ta

tio

n

u

lla

m

c

o

r

p

e

r

s

u

s

c

ip

it lo

b

o

r

tis

n

is

l u

t a

liq

u

ip

e

x

e

a

c

o

m

m

o

d

o

c

o

n

s

e

q

u

a

t.

D

u

is

a

u

te

m

v

e

l

e

u

m

ir

iu

r

e

d

o

lo

r

in

h

e

n

d

r

e

r

it

in

v

u

lp

u

ta

te

v

e

lit

e

s

s

e

m

o

le

s

tie

c

o

n

s

e

q

u

a

t,

v

e

l

illu

m

d

o

lo

r

e

e

u

fe

u

g

ia

t n

u

lla

~

a

c

ilis

is

a

t v

e

r

o

e

r

o

s

e

t a

c

c

u

m

s

a

n

e

t iu

s

to

o

d

io

d

ig

n

is

s

im

q

u

i b

la

n

d

it p

r

a

e

-

s

e

n

t

lu

p

ta

tu

m

z

z

r

il

d

e

le

n

it

a

u

g

u

e

d

u

is

d

o

lo

r

e

te

fe

u

g

a

it

n

u

lla

fa

c

ilis

i.

L

o

r

e

m

ip

s

u

m

d

o

lo

r

s

it

a

m

e

t,

c

o

n

s

e

c

te

tu

e

r

a

d

ip

is

c

in

g

e

lit,

s

e

d

d

ia

m

n

o

n

u

m

m

y

n

ib

h

e

u

is

m

o

d

tin

c

id

u

n

t

u

t

la

o

r

e

e

t

d

o

lo

r

e

m

a

g

n

a

a

liq

u

a

m

e

r

a

t v

o

lu

tp

a

t.

U

t

w

is

i

e

n

im

a

d

m

in

im

v

e

n

ia

m

,

q

u

is

n

o

s

tr

u

d

e

x

e

r

c

i

ta

tio

n

u

lla

m

c

o

r

p

e

r

s

u

s

c

ip

it

lo

b

o

r

tis

n

is

l

u

t

a

liq

u

ip

e

x

e

a

c

o

m

m

o

d

o

c

o

n

s

e

q

u

a

t.

D

u

is

a

u

te

m

v

e

l e

u

m

ir

iu

r

e

d

o

lo

r

in

h

e

n

d

r

e

r

it in

v

u

lp

u

ta

te

v

e

lit

e

s

s

e

m

o

le

s

tie

c

o

n

s

e

q

u

a

t,

v

e

l illu

m

d

o

lo

r

e

e

u

fe

u

g

ia

t n

u

lla

fa

c

ilis

is

a

t v

e

r

o

e

r

o

s

e

t a

c

c

u

m

s

a

n

e

t iu

s

to

.

L

o

r

e

m

ip

s

u

m

d

o

lo

r

s

it

a

m

e

t,

c

o

n

s

e

c

te

tu

e

r

a

d

ip

is

c

in

g

e

lit,

s

e

d

d

ia

m

n

o

n

u

m

m

y

n

ib

h

e

u

is

m

o

d

tin

-

c

id

u

n

t u

t la

o

r

e

e

t d

o

lo

r

e

m

a

g

n

a

a

liq

u

a

m

e

r

a

t v

o

lu

tp

a

t.

U

t w

is

i e

n

im

a

d

m

in

im

v

e

n

ia

m

,

q

u

is

n

o

s

tr

u

d

e

x

e

r

c

i ta

tio

n

u

lla

m

c

o

r

p

e

r

s

u

s

c

ip

it lo

b

o

r

tis

n

is

l u

t a

liq

u

ip

e

x

e

a

c

o

m

m

o

d

o

c

o

n

s

e

q