Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Microsatellite Distribution On Sex Chromosomes at Different Stages of Heteromorphism and Heterochroma

Transféré par

Asesino Guerrero0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

21 vues7 pagesMicrosatellite distribution on sex chromosomes at different stages of heteromorphism and heterochromatinization in two lizard species. Accumulation of repetitive sequences such as microsatellites has not been studied in most squamate reptiles.

Description originale:

Titre original

Microsatellite Distribution on Sex Chromosomes at Different Stages of Heteromorphism and Heterochroma

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentMicrosatellite distribution on sex chromosomes at different stages of heteromorphism and heterochromatinization in two lizard species. Accumulation of repetitive sequences such as microsatellites has not been studied in most squamate reptiles.

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

21 vues7 pagesMicrosatellite Distribution On Sex Chromosomes at Different Stages of Heteromorphism and Heterochroma

Transféré par

Asesino GuerreroMicrosatellite distribution on sex chromosomes at different stages of heteromorphism and heterochromatinization in two lizard species. Accumulation of repetitive sequences such as microsatellites has not been studied in most squamate reptiles.

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 7

RESEARCH ARTI CLE Open Access

Microsatellite distribution on sex chromosomes at

different stages of heteromorphism and

heterochromatinization in two lizard species

(Squamata: Eublepharidae: Coleonyx elegans and

Lacertidae: Eremias velox)

Martina Pokorn

1,2

, Luk Kratochvl

1*

and Eduard Kejnovsk

3

Abstract

Background: The accumulation of repetitive sequences such as microsatellites during the differentiation of sex

chromosomes has not been studied in most squamate reptiles (lizards, amphisbaenians and snakes), a group which

has a large diversity of sex determining systems. It is known that the Bkm repeats containing tandem arrays of

GATA tetranucleotides are highly accumulated on the degenerated W chromosomes in advanced snakes. Similar,

potentially homologous, repetitive sequences were found on sex chromosomes in other vertebrates. Using FISH

with probes containing all possible mono-, di-, and tri-nucleotide sequences and GATA, we studied the genome

distribution of microsatellite repeats on sex chromosomes in two lizard species (the gecko Coleonyx elegans and

the lacertid Eremias velox) with independently evolved sex chromosomes. The gecko possesses heteromorphic

euchromatic sex chromosomes, while sex chromosomes in the lacertid are homomorphic and the W chromosome

is highly heterochromatic. Our aim was to test whether microsatellite distribution on sex chromosomes

corresponds to the stage of their heteromorphism or heterochromatinization. Moreover, because the lizards lie

phylogenetically between snakes and other vertebrates with the Bkm-related repeats on sex chromosomes, the

knowledge of their repetitive sequence is informative for the determination of conserved versus convergently

evolved repetitive sequences across vertebrate lineages.

Results: Heteromorphic sex chromosomes of C. elegans do not show any sign of microsatellite accumulation. On

the other hand, in E. velox, certain microsatellite sequences are extensively accumulated over the whole length or

parts of the W chromosome, while others, including GATA, are absent on this heterochromatinized sex

chromosome.

Conclusion: The accumulation of microsatellite repeats corresponds to the stage of heterochromatinization of sex

chromosomes rather than to their heteromorphism. The lack of GATA repeats on the sex chromosomes of both

lizards suggests that the Bkm-related repeats on sex chromosomes in snakes and other vertebrates evolved

convergently. The comparison of microsatellite sequences accumulated on sex chromosomes in E. velox and in

other eukaryotic organisms suggests that historical contingency, not characteristics of particular sequences, plays a

major role in the determination of which microsatellite sequence is accumulated on the sex chromosomes in a

particular lineage.

* Correspondence: lukkrat@email.cz

1

Department of Ecology, Faculty of Science, Charles University in Prague,

Vinin 7, 128 44 Praha 2, Czech Republic

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article

Pokorn et al. BMC Genetics 2011, 12:90

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2156/12/90

2011 Pokorn et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in

any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Background

The evolution of sex chromosomes from autosomes has

been documented many times in different organisms [1];

recently reviewed e.g. in [2]; but see e.g. [3]]. During

their evolution, sex chromosomes go progressively

through several steps. Briefly, the first step is the acqui-

sition of sex determining locus or loci. Subsequently,

the genetic content of both members of the pair diverge.

The specialization of sex chromosomes for their sex-

specific roles [e.g. [4]] selects for the reduction of the

interchange of genetic material between sex chromo-

somes and thus for lower levels of recombination. How-

ever, lack of recombination leaves the unpaired sex

chromosomes (Y and W) without the possibility to cor-

rect mutations in coding sequences, which leads to an

unusually low content of functional genes. Moreover,

cessation of recombination opens doors for the accumu-

lation of various repeats on sex chromosomes (e.g.

microsatellites, transposons, rDNA sequences; [5]).

Alternatively, the accumulation of repetitive sequences

may not be a consequence of reduced recombination,

but its cause [6]. By generating asynchrony in the DNA

replication pattern of X and Y, respectively Z and W

chromosomes, it can reduce the crossing-over frequency

between them [e.g. [7]]. The accumulation of repeats on

a heterogametic sex chromosome (Y or W) may be so

massive that the chromosome is finally much larger

than its homologous counterpart in the pair. The het-

erogametic sex chromosome may even become the lar-

gest chromosome in the genome such as the Y

chromosome in the plant Silene latifolia [[8], [9]]. On

the other hand, in some lineages, heterogametic sex

chromosomes may progressively decrease in size [e.g.

[10]] and such degeneration can result in their elimina-

tion from the genome [e.g. [11]]. In yet other cases, sex

chromosomes may stay homomorphic for a long evolu-

tionary time [e.g. [10,12,13]]. In many organisms, the

heterogametic sex chromosome has been found to be

highly heterochromatinized [e.g. [12,14]]. The hetero-

chromatinization may be a mechanism for the defence

against the activity of transposable elements or other

repetitive sequences to safeguard genome integrity [e.g.

[15,16]].

Squamate reptiles, the lineage encompassing lizards,

snakes and amphisbaenians, represent an interesting

group for the exploration of the evolution of sex chro-

mosomes, as they possess substantial variability in sex

determining mechanisms [17-19]. Squamate reptiles

include species with environmental sex determination, i.

e. without sex chromosomes; species with homomorphic

sex chromosomes, and those with heteromorphic sex

chromosomes. All three situations can be found even in

a single family, for example in dragon lizards or eye-lid

geckos [20-22]. Sex chromosomes are at various stages

of the general process of sex chromosome evolution in

different squamate species and they evolved within

squamates independently several times as supported by

differences in their size, shape and type (male or female

heterogamety) but also by molecular-cytogenetic tests of

synteny of sex chromosomes and phylogenetic distribu-

tion of sex determining systems [10,19,20,23].

At the time of submitting, to our knowledge, the accu-

mulation of repeats during the degeneration of sex chro-

mosomes has been studied only in a single lineage of

squamate reptiles, in that of snakes [7,24,25]. Pythons,

the group in the rather basal position of snake phylo-

geny [26], with homomorphic sex chromosomes, do not

show any accumulation of repeats, while the degener-

ated W sex chromosomes in many advanced snakes

from the crown clade Colubroidea such as colubrids or

elapids, exhibit a massive accumulation of repeats

[24,25]. For example, the W chromosome in an elapid

snake Notechis scutatus is composed almost entirely of

repetitive sequences, including 18S rDNA and the

banded krait minor-satellite (Bkm) repeats [26]. The

Bkm repeats consist of tandem arrays of 26 and 12

copies, respectively, of two tetranucleotides, GATA and

GACA [27]. Bkm-related repeats are also accumulated

on the heterogametic sex chromosomes in many verte-

brates, including humans, and also in plants [28-33]. It

was speculated that the Bkm-related repeats are func-

tional, playing a role in the transcriptional activation of

sex chromosome heterochromatin [7]. A common origin

of the Bkm-related repeats across different eukaryotic

lineages was assumed [e.g. [34]], however, a convergent

evolution is also likely [35]. Recently, based on the

results of chicken W chromosome painting in snakes,

OMeally and colleagues [25] concluded that heteroga-

metic sex chromosomes in birds and derived snakes

may share repetitive sequences. They suggested that this

observation could be explained by yet undetected syn-

teny of parts of the sex chromosomes between these

lineages. The homology of repetitive sequences accumu-

lated on sex chromosomes could be tested by the eva-

luation of the identity of repeats on sex chromosomes

in other lineages of squamates phylogenetically nested

between snakes, birds and vertebrates with the Bkm-

related repeats.

The aim of the present study is to compare the distri-

bution of microsatellite sequences on differently differ-

entiated sex chromosomes in two lizard species with

independently evolved sex chromosomes and to deter-

mine whether the distribution of microsatellite repeats

on sex chromosomes corresponds to the stage of their

heteromorphism or heterochromatinization. Multiple

sex chromosomes (X

1

X

1

X

2

X

2

/X

1

X

2

Y) are heteromorphic

Pokorn et al. BMC Genetics 2011, 12:90

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2156/12/90

Page 2 of 7

and fully euchromatic in the first studied species, the

gecko Coleonyx elegans from the family Eublepharidae

[21]. On the other hand, the ZZ/ZW sex chromosomes

in the second species, Eremias velox from the family

Lacertidae, are homomorphic and the W chromosome

is highly heterochromatic [36]. Moreover, the gekkotan

lizards represent one of the basal groups of squamate

reptiles, while lacertids are much more closely related to

snakes [37]. The knowledge of repetitive sequences on

the sex chromosomes in the two selected species should

therefore be informative for the determination of the

homology of the Bkm-related and other repeats across

vertebrate lineages.

Methods

The lizard individuals involved in the study were captive

bred animals maintained in the breeding room at the

Faculty of Science, Charles University in Prague, Czech

Republic (accreditation No. 24773/2008-10001). The

procedures on animals were held under the approval

and supervision of the Ethical Committee of the Faculty

of Science, Charles University in Prague (permission No.

29555/2006-30). Metaphase chromosome spreads were

prepared from cultures of whole blood from a male of

C. elegans and a female of E. velox following the proto-

cols described by Ezaz and colleagues [14] with slight

modifications. C-banding was performed following the

method described by Pokorn and colleagues [21].

Oligonucleotides containing microsatellite sequences

were directly labelled with Cy3 at the 5 end during

synthesis by VBC-Biotech (Wien, Austria). All possible

mono- (d(A)

30

, d(C)

30

), di- (d(CA)

15

, d(GA)

15

, d(GC)

15

,

d(TA)

15

), and tri-nucleotides (d(CAA)

10

, d(CAG)

10

, d

(CGG)

10

, d(GAA)

10

, d(CAC)

10

, d(CAT)

10

, d(GAC)

10

, d

(GAG)

10

, d(TAA)

10

, d(TAC)

10

) and d(GATA)

8

were

used. The tetranucleotide was included to test for the

presence of the Bkm-related repeats. Slide denaturation

was performed in 7:3 (v/v) formamide:2xSSC for two

minutes at 72C, then the slides were dehydrated using

50%, 70% and 100% ethanol (-20C) serie and air-dried.

The probes were denatured at 70C for 10 minutes in a

mix containing 50% formamide (v/v), 2xSSC and 10%

dextransulfate (w/v) and subsequently applied to the

slides, covered with plastic coverslips, and hybridized for

18 hours at 37C. The slides were washed at room tem-

perature twice for 5 minutes in 2xSSC and twice for 5

minutes in 1xSSC. The slides were analysed using an

Olympus Provis microscope and the image analysis was

performed using ISIS software (Metasystems). The FISH

results were confirmed in at least three different meta-

phases per treatment.

The heterogametic sex chromosomes in both studied

species of lizards are easily recognizable. The Y chromo-

some is the largest and the only metacentric

chromosome in karyotype of C. elegans [21]. The W

chromosome of E. velox is an acrocentric chromosome

of similar size to the Z chromosome, but only the W is

conspicuously DAPI-positive [23].

Results

There was no accumulation of mono-, di-, tri-nucleo-

tides or GATA repeats detected on sex chromosomes in

C. elegans. All tested sequences showed relatively uni-

form distribution throughout the genome of this species.

Strong accumulations of several microsatellites were

detected either on the W chromosome or on some

autosomes in E. velox (Figure 1). The W chromosome

showed an interspersed distribution pattern of microsa-

tellite sequences typical for the Z chromosome and

autosomes only in three cases, i.e. in the probes d(C)

30

,

d(CAA)

10

and d(GAC)

10

. The d(CGG)

10

and d(CAC)

10

sequences exhibited notable accumulations just on small

autosomes. Only in two cases (d(A)

30

, d(TA)

15

) was

there a concurrently notable accumulation of microsa-

tellites on the whole W chromosome and on two differ-

ent pairs of autosomes. In all other cases, the W

chromosome showed a more highly distinct pattern

than the Z chromosome and all autosomal pairs. Some

microsatellites with tri-nucleotide motifs (d(CAG)

10

, d

(CAT)

10

, d(GAG)

10

, d(TAC)

10

, d(TAA)

10

) were exten-

sively accumulated over the whole length of the W

chromosome, while three di-nucleotide repeats (d(CA)

15

, d(GA)

15

, d(GC)

15

) were accumulated just in the cen-

tromeric parts of the W chromosome. Three microsatel-

lite sequences (d(GA)

15

, d(GAA)

10

, d(GATA)

8

) were

conspicuously lacking on the W chromosome, although

the signal was otherwise uniformly distributed across

the rest of the genome.

Discussion

The FISH patterns using the probes bearing microsatel-

lite repeats in the two lizard species contrasted greatly.

The FISH experiments did not reveal a substantial accu-

mulation of microsatellites neither on X

1

, X

2

and Y sex

chromosomes nor on autosomes in the gecko C. elegans.

The Y chromosome is the largest chromosome in the

karyotype and certain parts of the Y and the X

1

chro-

mosome consist largely of repetitive elements. Specifi-

cally, both these chromosomes carry notable

accumulations of 28S rDNA repeats [Figs. two d, i in

[21]]. Nevertheless, these accumulations are restricted to

just nucleolus organizer regions (NORs), although

rDNA-related repeats have the potential to spread over

sex chromosomes [38]. Previously, through chromosome

painting, we documented that the Y and X

1

and X

2

chromosomes in C. elegans share similar DNA content

and concluded that sex chromosomes of this species are

only poorly differentiated [21]. The results of the

Pokorn et al. BMC Genetics 2011, 12:90

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2156/12/90

Page 3 of 7

painting with the microsatellite probes further support

this conclusion.

The heterochromatinized W chromosome and some

autosomes show strong microsatellite accumulation in

the lacertid lizard E. velox (Figure 1). The distribution of

microsatellite sequences on the W chromosome differed

greatly in various microsatellites. We found enrichment

of some microsatellite sequences over the whole W

chromosome, while the accumulation of some sequences

(CA, GA, and GC repeats) was restricted to a part of the

W chromosome near the centromere. This unequal dis-

tribution could reflect constitutional characteristics of

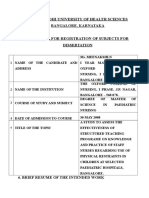

Figure 1 Mitotic metaphase chromosomes of Eremias velox females hybridized with different microsatellite-containing

oligonucleotides. Chromosomes were counterstained with DAPI (blue) and microsatellite probes were labelled with Cy3 (red signals). Last

figure represents C-banded metaphase chromosomes. Letters mark the W chromosomes, arrows indicate autosomal signals.

Pokorn et al. BMC Genetics 2011, 12:90

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2156/12/90

Page 4 of 7

individual microsatellites, e.g. their convenience for cen-

tromere formation; however, no accumulation of CA,

GA, and GC repetitive sequences was detected in the

centromeres of the Z chromosome and the autosomes

(Figure 1). Alternatively, the unequal distribution could

reflect an instantaneous stage of competition of indivi-

dual microsatellite sequences over a limited number of

positions on the W chromosome. Some sequences are

present on the Z chromosome and autosomes, but they

are notably lacking on the W chromosome (Figure 1).

Generally, sex chromosomes at the earliest stages of dif-

ferentiation mutually differ only in a small non-recom-

bining sex-determining region and are otherwise similar

to autosomes [e.g.[4]]. Therefore, it seems likely that the

comparable distribution of these sequences on the

recent Z chromosome and on autosomes in E. velox

reflects the ancestral situation and that the sequences

were present on the W chromosome at an early stage of

its differentiation as well and were later replaced by

more successful sequences. The alternative explanations

on unequal distribution of particular repeats can be

tested by the reconstruction of evolutionary dynamics of

microsatellite distribution on sex chromosomes across

lacertids in future comparative analyses.

The microsatellite distribution in C. elegans and E.

velox corresponds to the general scenario of sex chro-

mosome evolution. Sex chromosomes in C. elegans,

although heteromorphic, probably represent an early

stage of sex chromosome differentiation. The lack of

microsatellite accumulation on sex chromosomes in this

species is comparable to the situation on homomorphic

sex chromosomes in relatively basal snakes [7,25]. The

present study documents that the DNA content strongly

differs between the euchromatic Z and the heterochro-

matic W chromosomes in E. velox (Figure 1), although

the sex chromosomes are homomorphic in this species

and in many other lacertids [12]. Heteromorphic sex

chromosomes are not always simply more diverged than

homomorphic ones. The changes of DNA sequences

and of karyotype during the evolution of sex chromo-

somes can be quite different stories. However, in most

cases, the accumulation of microsatellites precedes the

evolution of the heteromorphy of sex chromosomes.

Heteromorphic sex chromosomes with accumulated

repeats, e.g. in the advanced snakes from the families

Elapidae and Colubridae [25], may represent only the

later stage of the evolution of sex chromosomes.

Members of many genera in the family Lacertidae

from both its subfamilies (Gallotiinae and Lacertinae)

have the ZZ/ZW sex-chromosome system with sex

chromosomes at various stage of differentiation

[12,39,40]. Phylogenetic distribution of species with

known sex chromosomes suggests that female hetero-

gamety is ancestral for the family [e.g. [19]; cf. to

phylogenetic relationships within the family in [39] or

[41]]. A molecular clock based on mitochondrial DNA

sequences indicates that the separation of the Gallotii-

nae and Lacertinae occurred around 20 My ago [39].

The mechanism keeping homomorphy of sex chromo-

somes in the lineage leading to E. velox and in other

lacertids for such a long time in the face of the highly

divergent DNA content of sex chromosomes is not

known.

The Bkm-related repeats containing tandem copies of

GATA sequence have been shown to be accumulated

on the sex chromosomes of various eukaryotes including

advanced snakes [25]. The GATA repeats are uniformly

distributed over the autosomes and sex chromosomes in

C. elegans, and the W chromosome of E. velox even

exhibits a conspicuous depletion of this sequence (Fig-

ure 1), which supports the independent origins of the

Bkm-related repetitions on sex chromosomes in snakes

and other vertebrates. OMeally and colleagues [25] rea-

soned that as derived snake and bird sex chromosomes

share common repetitive sequences, this may be due to

the cryptic homology of parts of the sex chromosomes

between these lineages. However, no FISH signal on the

W chromosome was observed after hybridization of the

Bkm probe to chicken metaphase chromosomes in their

study. Moreover, sex chromosomes in snakes and birds

evolved from different autosomal pairs [10], and basal

snake and avian lineages have homomorphic sex chro-

mosomes without an accumulation of repetitive

sequences [13,24,25]. The independent origins of repeti-

tive sequences on degenerated W sex chromosomes in

both these lineages therefore seem more likely, espe-

cially when high dynamism of repetitive DNA is taken

into account.

Due to different biochemical characteristics, particular

microsatellite sequences should differ in their potency

to accumulate on sex chromosomes. We should then

observe an accumulation of the same sequences on

independently evolved sex chromosomes in different

organisms. However, the data accumulated so far does

not support this prediction. For example, among all pos-

sible trinucleotide sequences, tandem copies of CAA,

CAG, GAA and TAA showed the most notable accumu-

lation on the Y chromosome in the plant Silene latifolia

[42]. However, out of these four sequences, only CAG

and TAA tandem copies are accumulated on the W

chromosome, while CAA repeats are uniformly distribu-

ted across all chromosomes and GAA repeats are even

lacking on the W chromosome in E. velox (Figure 1).

Similarly, the CGG repeats are accumulated on the Y

chromosome of the fish Hoplias malabaricus [43], but

they are missing on the W chromosome of the lizard. In

conclusion, various repetitive sequences follow very dif-

ferent trajectories on sex chromosomes in different

Pokorn et al. BMC Genetics 2011, 12:90

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2156/12/90

Page 5 of 7

organismal lineages. The identity of particular microsa-

tellite sequences accumulated on sex chromosomes

seems to largely reflect historical contingency.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our results support the view of sex chro-

mosome evolution as a colourful myriad of situations

and trajectories where many processes, often opposing,

are in action. The evolution of DNA sequences and the

evolution of karyotypes can represent different stories of

the shaping of sex chromosomes. Microsatellite

dynamics can be tied rather to heterochromatinization

than to heteromorphism of sex chromosomes. Microsa-

tellites are the most dynamic component of genomes,

and as non-recombining regions of the sex chromo-

somes give them the chance to expand here, their con-

tribution to sex chromosomes dynamics is significant. It

seems that historical contingency, not the characteristics

of particular sequences, plays a major role in the deter-

mination of which microsatellite sequence is accumu-

lated on the sex chromosomes in a particular lineage.

Acknowledgements

C.M. Johnson offered many valuable critical comments. The funding to MP

was provided by the Grant Agency of the Charles University (project No.

94209), to MP and LK by the Czech Science Foundation (project No. 506/10/

0718), and to EK by the Czech Science Foundation (project No. P305/10/

0930) and by the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic (projects Nos.

AV0Z50040507 and AV0Z50040702). The institutional support was given by

the Ministry of the Education of the Czech Republic (MSM0021620828). This

paper represents the fourth part of our series Evolution of sex determining

systems in lizards.

Author details

1

Department of Ecology, Faculty of Science, Charles University in Prague,

Vinin 7, 128 44 Praha 2, Czech Republic.

2

Department of Vertebrate

Evolutionary Biology and Genetics, Institute of Animal Physiology and

Genetics, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Rumbursk 89, 277 21

Libchov, Czech Republic.

3

Laboratory of Plant Developmental Genetics,

Institute of Biophysics, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic,

Krlovopolsk 135, 612 65 Brno, Czech Republic.

Authors contributions

MP carried out the leukocyte cultures preparation and chromosome

preparation and participated on the design of the study and the drafting

the manuscript. LK participated on the chromosome preparation, design of

the study, and led the drafting of the manuscript. EK carried out FISH

experiments, participated on the design of the study and the drafting of the

manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Received: 2 August 2011 Accepted: 20 October 2011

Published: 20 October 2011

References

1. Ohno S: Sex chromosomes and sex-linked genes Springer-Verlag Berlin.

Heidelberg. New York; 1967.

2. Charlesworth D, Mank J: The birds and the bees and the flowers and the

trees: Lessons from genetic mapping of sex determination in plants and

animals. Genetics 2010, 186:9-31.

3. Carvalho AB: Origin and evolution of the Drosophila Y chromosome. Curr

Opin Genet Dev 2002, 12:664-668.

4. Rice WR: Sex chromosomes and the evolution of sexual dimorphism.

Evolution 1984, 38:735-742.

5. Charlesworth B: The evolution of chromosomal sex determination. In

Genetics and Biology of Sex Determination. Edited by: Novartis Foundation.

John Wiley and sons Ltd; 2002:207-224.

6. Steinemann S, Steinemann M: Y chromosomes: born to be destroyed.

BioEssays 2005, 27:1076-1083.

7. Singh L, Purdom IF, Jones KW: Satellite DNA and evolution of sex

chromosomes. Chromosoma 1976, 59:43-62.

8. Kejnovsky E, Kubat Z, Hobza R, Lengerova M, Sato S, Tabata S, Fukui K,

Matsunaga S, Vyskot B: Accumulation of chloroplast DNA sequences on

the Y chromosome of Silene latifolia. Genetica 2006, 128:167-175.

9. Kejnovsky E, Hobza R, Kubat Z, Cermak T, Vyskot B: The role of repetitive

DNA in structure and evolution of sex chromosomes in plants. Heredity

2009, 102:533-541.

10. Matsubara K, Tarui H, Toriba M, Yamada K, Nishida-Umehara Ch, Agata K,

Matsuda Y: Evidence for different origin of sex chromosomes in snakes,

birds, and mammals and stepwise differentiation of snake sex

chromosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006, 103:18190-18195.

11. Fredga K: Aberrant chromosomal sex-determining mechanisms in

mammals, with special reference to species with XY females. Phil Trans R

Soc Lond B 1988, 322:83-95.

12. Olmo E, Odierna G, Capriglione T: Evolution of sex-chromosomes in

lacertid lizards. Chromosoma 1987, 96:33-38.

13. Tsuda Y, Nishida-Umehara C, Ishijima J, Yamada K, Matsuda Y: Comparison

of the Z and W sex chromosomal architectures in elegant crested

tinamou (Eudromia elegans) and ostrich (Struthio camelus) and the

process of sex chromosome differentiation in palaeognathous birds.

Chromosoma 2007, 116:159-173.

14. Ezaz T, Quinn AE, Miura I, Sarre D, Georges A, Graves JAM: The dragon

lizard Pogona vitticeps has ZZ/ZW micro-sex chromosomes. Chromosome

Res 2005, 13:763-776.

15. Biemont C: Are transposable elements simply silenced or are they under

house arrest? Trends Genet 2009, 25:333-334.

16. Grewal SIS, Jia S: Heterochromatin revisited. Nat Rev Genet 2007, 8:35-46.

17. Janzen FJ, Phillips PC: Exploring the evolution of environmental sex

determination, especially in reptiles. J Evol Biol 2006, 19:1775-1784.

18. Organ C, Janes DE: Evolution of sex chromosomes in Sauropsida. Integr

Comp Biol 2008, 48:512-519.

19. Pokorn M, Kratochvl L: Phylogeny of sex-dermining mechanisms in

squamate reptiles: Are sex chromosomes an evolutionary trap? Zool J

Linn Soc 2009, 156:168-183.

20. Ezaz T, Quinn AE, Sarre SD, OMeally D, Georges A, Graves JAM: Molecular

marker suggests rapid changes of sex-determining mechanisms in

Australian dragon lizards. Chromosome Res 2009, 17:91-98.

21. Pokorn M, Rbov M, Rb P, Ferguson-Smith MA, Rens W, Kratochvl L:

Differentiation of sex chromosomes and karyotypic evolution in the eye-

lid geckos (Squamata: Gekkota: Eublepharidae), a group with different

modes of sex determination. Chromosome Res 2010, 18:809-820.

22. Gamble T: A review of sex determining mechanisms in geckos (Gekkota:

Squamata). Sex Dev 2010, 4:88-103.

23. Pokorn M, Giovannotti M, Kratochvl L, Kasai K, Trifonov VA, OBrien PCM,

Caputo V, Olmo E, Ferguson-Smith MA, Rens W: Strong conservation of

the bird Z chromosome in reptilian genomes is revealed by

comparative painting despite 275 My divergence. Chromosoma 2011,

120:455-468.

24. Jones KW, Singh L: Snakes and evolution of sex chromosomes. Trends

Genet 1985, 1:55-61.

25. OMeally D, Patel HR, Stiglec R, Sarre SD, Geordes A, Graves JAM, Ezaz T:

Non-homologous sex chromosomes of birds and snakes share repetitive

sequences. Chromosome Res 2010, 18:787-800.

26. Lee MSY, Hugall AF, Lawson R, Scanlon JD: Phylogeny of snakes

(Serpentes): combining morphological and molecular data in likelihood,

Bayesian and parsimony analyses. Syst Biodiv 2007, 5:371-389.

27. Epplen JT, McCarrey JR, Sutou S, Ohno S: Base sequence of a cloned

snake W-chromosome DNA fragment and identification of a male-

specific putative mRNA in the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1982,

79:3798-802.

28. Jones KW, Singh L: Conserved repeated DNA sequences in vertebrate sex

chromosomes. Hum Genet 1981, 58:46-53.

29. Arnemann J, Jakubiczka S, Schmidtke J, Schfer R, Epplen JT: Clustered

GATA repeats (Bkm sequences) on the human Y chromosome. Hum

Genet 1986, 73:301-303.

Pokorn et al. BMC Genetics 2011, 12:90

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2156/12/90

Page 6 of 7

30. Schfer R, Bltz E, Becker A, Bartels F, Epplen JT: The expression of the

evolutionarily conserved GATA/GACA repeats in mouse tissues.

Chromosoma 1986, 93:496-501.

31. Nanda I, Feichtinger W, Schmid M, Schrder JH, Zischler H, Epplen JT:

Simple repetitive sequences are associated with differentiation of the

sex chromosomes in the guppy fish. J Mol Evol 1990, 30:456-462.

32. Nanda I, Zischler H, Epplen C, Guttenbach M, Schmid M: Chromosomal

organization of simple repeated DNA sequences. Electrophoresis 1991,

12:193-203.

33. Parasnis AS, Ramakrishna W, Chowdari KV, Gupta VS, Ranjekar PK:

Microsatellite (GATA)n reveals sexspecific differences in papaya. Theor

Appl Genet 1999, 99:1047-1052.

34. Epplen JT, Cellini A, Shorte M, Ohno S: On evolutionarily conserved simple

repetitive DNA sequences: Do sex-specific satellite components serve

any sequence dependent function? Differentiation 1983, 23(Suppl):

S60-S63.

35. Epplen JT: On simple repeated GATCA sequences in animal genomes: A

critical reappraisal. J Hered 1988, 79:409.

36. Ivanov VG, Bogdanov OP, Anislmova EY, Fedorova TA: Studies of the

karyotypes of three lizard species (Sauria, Scincidae, Lacertidae).

Tsitologiya 1973, 15:1291-1296.

37. Vidal N, Hedges SB: The phylogeny of squamate reptiles (lizards, snakes

and amphisbaenians) inferred from nine nuclear protein-coding genes.

C R Biol 2005, 328:1000-1008.

38. Kawai A, Nishida-Umehara C, Ishijima J, Tsuda Y, Ota H, Matsuda Y:

Different origins of bird and reptile sex chromosomes inferred from

comparative mapping of chicken Z-linked genes. Cytogenet Genome Res

2007, 117:92-102.

39. Arnold AN, Arrubas O, Carranza S: Systematics of the Palaearctic and

Oriental lizard tribe Lacertini (Squamata: Lacertidae: Lacertinae), with

descriptions of eight new genera. Zootaxa 2007, 1430:1-86.

40. Olmo E, Signorino GG: Chromorep: A reptile chromosomes database.

[http://ginux.univpm.it/scienze/chromorep/].

41. Mayer W, Pavlicev M: The phylogeny of the family Lacertidae (Reptilia)

based on nuclear DNA sequences: convergent adaptations to arid

habitats within the subfamily Eremiainae. Mol Phyl Evol 2007, 44:1155-63.

42. Kubat Z, Hobza R, Vyskot B, Kejnovsky E: Microsatellite accumulation on

the Y chromosome in Silene latifolia. Genome 2008, 51:350-356.

43. Cioffi MB, Kejnovsk E, Bertollo LAC: The chromosomal distribution of

microsatellite repeats in the genome of the Wolf Fish Hoplias

malabaricus, focusing on the sex chromosomes. Cytogenet Genome Res

2011, 132:289-296.

doi:10.1186/1471-2156-12-90

Cite this article as: Pokorn et al.: Microsatellite distribution on sex

chromosomes at different stages of heteromorphism and

heterochromatinization in two lizard species (Squamata: Eublepharidae:

Coleonyx elegans and Lacertidae: Eremias velox). BMC Genetics 2011 12:90.

Submit your next manuscript to BioMed Central

and take full advantage of:

Convenient online submission

Thorough peer review

No space constraints or color gure charges

Immediate publication on acceptance

Inclusion in PubMed, CAS, Scopus and Google Scholar

Research which is freely available for redistribution

Submit your manuscript at

www.biomedcentral.com/submit

Pokorn et al. BMC Genetics 2011, 12:90

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2156/12/90

Page 7 of 7

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Atlas of Feline Anatomy For VeterinariansDocument275 pagesAtlas of Feline Anatomy For VeterinariansДибензол Ксазепин100% (4)

- Giovannotti Et Al 2016Document16 pagesGiovannotti Et Al 2016lucaPas encore d'évaluation

- Sex ChromosomeDocument8 pagesSex ChromosomeJoshua BuffaloPas encore d'évaluation

- Genetic Diversity in The UV Sex Chromosomes of TheDocument18 pagesGenetic Diversity in The UV Sex Chromosomes of TheCarlos Lesmes DíazPas encore d'évaluation

- Pinto EtalDocument9 pagesPinto Etalapi-480736854Pas encore d'évaluation

- Genes 09 00264Document18 pagesGenes 09 00264Nhân Nguyễn HoàiPas encore d'évaluation

- Chatterjee2017 Article DosageCompensationAndItsRolesIDocument19 pagesChatterjee2017 Article DosageCompensationAndItsRolesIAngelicaPas encore d'évaluation

- L3-S5-Biodiv1-Ori Cell Euc (Eng) (x2)Document32 pagesL3-S5-Biodiv1-Ori Cell Euc (Eng) (x2)meliaekaPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 s2.0 S0960982213010270 MainDocument3 pages1 s2.0 S0960982213010270 MainPiyaaPas encore d'évaluation

- KaryotypeDocument9 pagesKaryotypeAppas SahaPas encore d'évaluation

- 2009 Kingsley Convergent Skeletal Evolution in NinespineDocument8 pages2009 Kingsley Convergent Skeletal Evolution in NinespineAntonio Jafar GarciaPas encore d'évaluation

- Karyotype and Its EvolutionDocument21 pagesKaryotype and Its Evolutionshagun brarPas encore d'évaluation

- Hal 00893898Document31 pagesHal 00893898Vesee KavezeriPas encore d'évaluation

- How Is Sex Determined in Insects?: PrefaceDocument2 pagesHow Is Sex Determined in Insects?: PrefaceZubia JabeenPas encore d'évaluation

- Sex Is Determined by XX/XY Sex Chromosomes in Australasian Side-Necked Turtles (Testudines: Chelidae)Document11 pagesSex Is Determined by XX/XY Sex Chromosomes in Australasian Side-Necked Turtles (Testudines: Chelidae)eeePas encore d'évaluation

- Chromosome Elimination in Sciarid FliesDocument9 pagesChromosome Elimination in Sciarid FliesTeumessiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Jurnal Meiosis Internasional PDFDocument14 pagesJurnal Meiosis Internasional PDFRina ArtatyPas encore d'évaluation

- Module 1: Introduction To GeneticsDocument3 pagesModule 1: Introduction To Geneticsrizza reyesPas encore d'évaluation

- Aphids and Ants, Mutualistic Species, Share A Mariner Element With An Unusual Location On Aphid Chromosomes - PMCDocument2 pagesAphids and Ants, Mutualistic Species, Share A Mariner Element With An Unusual Location On Aphid Chromosomes - PMC2aliciast7Pas encore d'évaluation

- HomeDocument8 pagesHomelonemudaserPas encore d'évaluation

- Genetics and Evolution1Document24 pagesGenetics and Evolution1Kankana BanerjeePas encore d'évaluation

- Some ProblemsDocument4 pagesSome ProblemsJoão Justino FloresPas encore d'évaluation

- Sym Chromista 2011Document18 pagesSym Chromista 2011Lailatul BadriyahPas encore d'évaluation

- Genome Assembly of Three Amazonian Morpho Butterfly Species Reveals Z-Chromosome Rearrangements Between Closely-Related Species Living in SympatryDocument18 pagesGenome Assembly of Three Amazonian Morpho Butterfly Species Reveals Z-Chromosome Rearrangements Between Closely-Related Species Living in SympatrySudip OfficialPas encore d'évaluation

- Kura Ku 2008Document13 pagesKura Ku 2008J.D. NoblePas encore d'évaluation

- The Organization of PericentroDocument33 pagesThe Organization of PericentroTunggul AmetungPas encore d'évaluation

- Chromosome MappingDocument4 pagesChromosome MappingJonelle U. BaloloyPas encore d'évaluation

- A Unique Chromosome Mutation in Pigs: Tandem Fusion-TranslocationDocument46 pagesA Unique Chromosome Mutation in Pigs: Tandem Fusion-TranslocationCaleb JenkinsPas encore d'évaluation

- Rowley ReviewDocument15 pagesRowley ReviewcienciaPas encore d'évaluation

- Crossover Interference Underlies Sex Differences in Recombination RatesDocument4 pagesCrossover Interference Underlies Sex Differences in Recombination RatesAlfiaPas encore d'évaluation

- SEXDocument9 pagesSEXAshish MakwanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Evolutionary Patterns of RNA-Based Duplication in Non-Mammalian ChordatesDocument9 pagesEvolutionary Patterns of RNA-Based Duplication in Non-Mammalian ChordatesFrontiersPas encore d'évaluation

- 5 Supplement - 1 1495Document10 pages5 Supplement - 1 1495Dika BrianPas encore d'évaluation

- Ellismar - 1802101010003 - Kelas 01Document17 pagesEllismar - 1802101010003 - Kelas 01EllismarPas encore d'évaluation

- Jurnal Meiosis InternasionalDocument14 pagesJurnal Meiosis InternasionalAgung Chandra100% (1)

- Sex - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument11 pagesSex - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopedialkdfjgldskjgldskPas encore d'évaluation

- Quim I Osen SoresDocument9 pagesQuim I Osen Soresnorma patriciaPas encore d'évaluation

- Early Journal Content On JSTOR, Free To Anyone in The WorldDocument7 pagesEarly Journal Content On JSTOR, Free To Anyone in The WorldramongonzaPas encore d'évaluation

- File 63e39a3b93de5Document6 pagesFile 63e39a3b93de5austrasan91Pas encore d'évaluation

- Molecular Phtlogeny of The Animal KingdomDocument10 pagesMolecular Phtlogeny of The Animal KingdomCarlos MeirellesPas encore d'évaluation

- Biolreprod 0247Document9 pagesBiolreprod 0247lucascotaPas encore d'évaluation

- GC% ContentDocument17 pagesGC% ContentRicky SenPas encore d'évaluation

- M - 23 Polytene ChromosomeDocument3 pagesM - 23 Polytene ChromosomeDr. Tapan Kr. DuttaPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 3Document7 pagesChapter 3candra mahardikaPas encore d'évaluation

- Genetics Course 3 M-1Document161 pagesGenetics Course 3 M-1Shiko LovePas encore d'évaluation

- Polytene Chromosomes in The Salivary Glands of DrosophilaDocument3 pagesPolytene Chromosomes in The Salivary Glands of DrosophilaRica Marquez100% (4)

- Research Review: Young Sex Chromosomes in Plants and AnimalsDocument13 pagesResearch Review: Young Sex Chromosomes in Plants and AnimalsGigi AnggiPas encore d'évaluation

- Outcrossing, Mitotic Recombination, and Life-History Trade-Offs Shape Genome Evolution in Saccharomyces CerevisiaeDocument6 pagesOutcrossing, Mitotic Recombination, and Life-History Trade-Offs Shape Genome Evolution in Saccharomyces CerevisiaeKaren VrPas encore d'évaluation

- Evolution and Origin of BiodiversityDocument13 pagesEvolution and Origin of Biodiversitykharry8davidPas encore d'évaluation

- Kel 5 - JURNAL UTAMA MikroDocument12 pagesKel 5 - JURNAL UTAMA MikroKholifah NyawijiPas encore d'évaluation

- Evidence For The Evolution of Bdelloid Rotifers Without Sexual ReproductionDocument5 pagesEvidence For The Evolution of Bdelloid Rotifers Without Sexual Reproductioningrid cazacu100% (1)

- Genetics: Genetics Is The Scientific Study of Heredity and Inherited VariationDocument13 pagesGenetics: Genetics Is The Scientific Study of Heredity and Inherited VariationDanielle GuerraPas encore d'évaluation

- Lecture2 - The Chromosome As Bassis of Heredity - ACPDocument33 pagesLecture2 - The Chromosome As Bassis of Heredity - ACPGideon CavidaPas encore d'évaluation

- Evolution of An ArsenalDocument32 pagesEvolution of An ArsenalVictor Isaac Perez soteloPas encore d'évaluation

- Venom Composition in Rattlesnakes TrendsDocument17 pagesVenom Composition in Rattlesnakes TrendsVictor Isaac Perez soteloPas encore d'évaluation

- The Role of Chromatin and Epigenetics in The Polyphenisms of Ant CastesDocument11 pagesThe Role of Chromatin and Epigenetics in The Polyphenisms of Ant CastesNina ČorakPas encore d'évaluation

- The Origin and Evolution of The Sexes Novel Insights F - 2016 - Comptes RendusDocument6 pagesThe Origin and Evolution of The Sexes Novel Insights F - 2016 - Comptes RendusarisPas encore d'évaluation

- Reciprocal Translocations: Tracing Their Meiotic BehaviorDocument9 pagesReciprocal Translocations: Tracing Their Meiotic BehaviorAsma HMILAPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 s2.0 S0093691X21001187 MainDocument8 pages1 s2.0 S0093691X21001187 MainMarta caracusaPas encore d'évaluation

- Microbiology Bacterial GeneticsDocument36 pagesMicrobiology Bacterial GeneticsSurabhiPas encore d'évaluation

- Modulacion Alosterica PDFDocument68 pagesModulacion Alosterica PDFAsesino GuerreroPas encore d'évaluation

- Origin and Evolution of The Vertebrate Telencephalon, With Special ReferenceDocument28 pagesOrigin and Evolution of The Vertebrate Telencephalon, With Special ReferenceAsesino GuerreroPas encore d'évaluation

- Canine Urinary IncontinenceDocument9 pagesCanine Urinary IncontinenceAsesino GuerreroPas encore d'évaluation

- Development of The Early Activity Scale For EnduranceDocument1 pageDevelopment of The Early Activity Scale For EnduranceAsesino GuerreroPas encore d'évaluation

- Development of The Early Activity Scale For EnduranceDocument1 pageDevelopment of The Early Activity Scale For EnduranceAsesino GuerreroPas encore d'évaluation

- Fisiopatología de La Placa VulnerableDocument35 pagesFisiopatología de La Placa VulnerableAsesino GuerreroPas encore d'évaluation

- Crayfish DissectionDocument6 pagesCrayfish DissectionAsesino GuerreroPas encore d'évaluation

- On The Functional Anatomy of Neuronal Units in The Abdominal of The Crayfish, Procambarus (Girard)Document20 pagesOn The Functional Anatomy of Neuronal Units in The Abdominal of The Crayfish, Procambarus (Girard)Asesino GuerreroPas encore d'évaluation

- J Exp Biol 1967 Atwood 249 61Document13 pagesJ Exp Biol 1967 Atwood 249 61Asesino GuerreroPas encore d'évaluation

- The Anatomy and Motor Nerve Distribution of The Eye Muscles in The CrayfishDocument18 pagesThe Anatomy and Motor Nerve Distribution of The Eye Muscles in The CrayfishAsesino GuerreroPas encore d'évaluation

- Anatomia de TupinambisDocument10 pagesAnatomia de TupinambisAsesino GuerreroPas encore d'évaluation

- Hubungan Body Image Dengan Pola Konsumsi Dan Status Gizi Remaja Putri Di SMPN 12 SemarangDocument7 pagesHubungan Body Image Dengan Pola Konsumsi Dan Status Gizi Remaja Putri Di SMPN 12 SemarangNanda MaisyuriPas encore d'évaluation

- Cyber Safety PP Presentation For Class 11Document16 pagesCyber Safety PP Presentation For Class 11WAZ CHANNEL100% (1)

- Test On QuantifiersDocument1 pageTest On Quantifiersvassoula35Pas encore d'évaluation

- Beckhoff Service Tool - USB StickDocument7 pagesBeckhoff Service Tool - USB StickGustavo VélizPas encore d'évaluation

- PV2R Series Single PumpDocument14 pagesPV2R Series Single PumpBagus setiawanPas encore d'évaluation

- Rajivgandhi University of Health Sciences Bangalore, KarnatakaDocument19 pagesRajivgandhi University of Health Sciences Bangalore, KarnatakaHUSSAINA BANOPas encore d'évaluation

- 99 AutomaticDocument6 pages99 AutomaticDustin BrownPas encore d'évaluation

- UgpeDocument3 pagesUgpeOlety Subrahmanya SastryPas encore d'évaluation

- Lecture 8 - ThermodynamicsDocument65 pagesLecture 8 - ThermodynamicsHasmaye PintoPas encore d'évaluation

- Series RL: Standards General DataDocument4 pagesSeries RL: Standards General DataBalamurugan SankaravelPas encore d'évaluation

- Sebaran Populasi Dan Klasifikasi Resistensi Eleusine Indica Terhadap Glifosat Pada Perkebunan Kelapa Sawit Di Kabupaten Deli SerdangDocument7 pagesSebaran Populasi Dan Klasifikasi Resistensi Eleusine Indica Terhadap Glifosat Pada Perkebunan Kelapa Sawit Di Kabupaten Deli SerdangRiyo RiyoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Problem of Units and The Circumstance For POMPDocument33 pagesThe Problem of Units and The Circumstance For POMPamarendra123Pas encore d'évaluation

- Shizhong Liang, Xueming Liu, Feng Chen, Zijian Chan, (2004) .Document4 pagesShizhong Liang, Xueming Liu, Feng Chen, Zijian Chan, (2004) .Kiệt LêPas encore d'évaluation

- Material Safety Data Sheet: Wonder Gel™ Stainless Steel Pickling GelDocument2 pagesMaterial Safety Data Sheet: Wonder Gel™ Stainless Steel Pickling GelTrần Thùy LinhPas encore d'évaluation

- Mdp36 The EndDocument42 pagesMdp36 The Endnanog36Pas encore d'évaluation

- Water Quality Index Determination of Malathalli LakeDocument16 pagesWater Quality Index Determination of Malathalli Lakeajay kumar hrPas encore d'évaluation

- Vital Statistics: Presented by Mrs - Arockia Mary Associate ProfDocument17 pagesVital Statistics: Presented by Mrs - Arockia Mary Associate ProfraghumscnPas encore d'évaluation

- Section 80CCD (1B) Deduction - About NPS Scheme & Tax BenefitsDocument7 pagesSection 80CCD (1B) Deduction - About NPS Scheme & Tax BenefitsP B ChaudharyPas encore d'évaluation

- Universal ING - LA.Boschi Plants Private LimitedDocument23 pagesUniversal ING - LA.Boschi Plants Private LimitedAlvaro Mendoza MaytaPas encore d'évaluation

- Complaint: Employment Sexual Harassment Discrimination Against Omnicom & DDB NYDocument38 pagesComplaint: Employment Sexual Harassment Discrimination Against Omnicom & DDB NYscl1116953Pas encore d'évaluation

- LECTURE NOTES-EAT 359 (Water Resources Engineering) - Lecture 1 - StudentDocument32 pagesLECTURE NOTES-EAT 359 (Water Resources Engineering) - Lecture 1 - StudentmusabPas encore d'évaluation

- Impression TakingDocument12 pagesImpression TakingMaha SelawiPas encore d'évaluation

- Glycolysis Krebscycle Practice Questions SCDocument2 pagesGlycolysis Krebscycle Practice Questions SCapi-323720899Pas encore d'évaluation

- Debunking The Evergreening Patents MythDocument3 pagesDebunking The Evergreening Patents Mythjns198Pas encore d'évaluation

- Classification of Nanostructured Materials: June 2019Document44 pagesClassification of Nanostructured Materials: June 2019krishnaPas encore d'évaluation

- Family Stress TheoryDocument10 pagesFamily Stress TheoryKarina Megasari WinahyuPas encore d'évaluation

- Maya Mendez ResumeDocument2 pagesMaya Mendez Resumeapi-520985654Pas encore d'évaluation

- 21A Solenoid Valves Series DatasheetDocument40 pages21A Solenoid Valves Series Datasheetportusan2000Pas encore d'évaluation

- Library PDFDocument74 pagesLibrary PDFfumiPas encore d'évaluation