Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Short-Course Prophylactic Zinc Supplementation For Diarrhea Morbidity in Infant 6-11 Month Children

Transféré par

listiarsasihDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Short-Course Prophylactic Zinc Supplementation For Diarrhea Morbidity in Infant 6-11 Month Children

Transféré par

listiarsasihDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

DOI: 10.1542/peds.

2012-2980

; originally published online June 3, 2013; 2013;132;e46 Pediatrics

Akash Malik, Davendra K. Taneja, Niveditha Devasenapathy and K. Rajeshwari

Infants of 6 to 11 Months

Short-Course Prophylactic Zinc Supplementation for Diarrhea Morbidity in

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/132/1/e46.full.html

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0031-4005. Online ISSN: 1098-4275.

Boulevard, Elk Grove Village, Illinois, 60007. Copyright 2013 by the American Academy

published, and trademarked by the American Academy of Pediatrics, 141 Northwest Point

publication, it has been published continuously since 1948. PEDIATRICS is owned,

PEDIATRICS is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly

at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on April 17, 2014 pediatrics.aappublications.org Downloaded from at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on April 17, 2014 pediatrics.aappublications.org Downloaded from

Short-Course Prophylactic Zinc Supplementation for

Diarrhea Morbidity in Infants of 6 to 11 Months

WHATS KNOWN ON THIS SUBJECT: Randomized controlled trials

have shown that zinc supplementation during diarrhea

substantially reduces the incidence and severity. However, the

effect of short-course prophylactic zinc supplementation has been

observed only in children .12 months of age.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS: The current study was able to show that

short-course prophylactic zinc supplementation signicantly

reduced diarrhea morbidity in apparently healthy infants of 6 to

11 months even after 5 months of follow-up.

abstract

BACKGROUND: Zinc supplementation during diarrhea substantially

reduces the incidence and severity of diarrhea. However, the effect

of short-course zinc prophylaxis has been observed only in children

.12 months of age. Because the incidence of diarrhea is comparatively

high in children aged 6 to 11 months, we assessed the prophylactic

effect of zinc on incidence and duration of diarrhea in this age group.

METHODS: In this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, we

enrolled infants aged 6 to 11 months froman urban resettlement colony in

Delhi, India, between January 1, 2011, and January 15, 2012. We randomly

assigned 272 infants to receive either 20 mg of zinc or a placebo

suspension orally every day for 2 weeks. The primary outcome was

the incidence of diarrhea per child-year. All analyses were done by

intention-to-treat.

RESULTS: A total of 134 infants in the zinc and 124 in the placebo groups

were assessed for the incidence of diarrhea. There was a 39% reduction

(crude incident rate ratio [IRR] 0.61, 95% condence interval [CI] 0.53

0.71) in episodes of diarrhea, 39% (adjusted IRR 0.61, 95% CI 0.540.69)

in the total number of days that a child suffered from diarrhea, and

reduction of 36% in duration per episode of diarrhea (IRR 0.64, 95% CI

0.560.74) during the 5 months of follow-up.

CONCLUSIONS: Short-course prophylactic zinc supplementation for

2 weeks may reduce diarrhea morbidity in infants of 6 to 11 months

for up to 5 months, in populations with high prevalence of wasting

and stunting. Pediatrics 2013;132:e46e52

AUTHORS: Akash Malik, MBBS,

a

Davendra K. Taneja, MD,

a

Niveditha Devasenapathy, MBBS, MSc,

b

and K. Rajeshwari,

MD

c

Departments of

a

Community Medicine, and

c

Paediatrics, Maulana

Azad Medical College, New Delhi, India; and

b

Indian Institute of

Public Health-Delhi, Public Health Foundation of India, New Delhi,

India

KEY WORDS

zinc, diarrhea, infants, randomized control trial

ABBREVIATIONS

CIcondence interval

IRRincident rate ratio

RRrate ratio

Dr Malik formulated the research question and contributed to

designing the study, wrote the research grants, carried out the

eld investigations, carried out the initial data analyses, and

drafted the initial manuscript; Dr Taneja contributed to

designing the study, contributed to developing the standard

operating procedures, implemented randomization and blinding,

and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Dr Devasenapathy

supervised the data collection and managed the data, analyzed

the data, and interpreted the ndings; Dr Rajeshwari supervised

the clinical data collection and management, and contributed to

developing the standard operating procedures; and all authors

approved the nal manuscript as submitted.

This trial was registered with the Clinical Trial Registry-India, No.

CTRI/2010/091/001417.

The Indian Council of Medical Research, Department of Health

Research (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare), Government of

India, which funded the study, had no role in the study design,

data collection, analysis, interpretation of results, or decision to

publish this research. AK, DKT, ND and KR had full access to all

the data in the study and had nal responsibility for the decision

to submit for publication.

www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2012-2980

doi:10.1542/peds.2012-2980

Accepted for publication Mar 25, 2013

Address correspondence to Akash Malik, MBBS, Department of

Community Medicine, Maulana Azad Medical College and

Associated Hospitals, Bahadur Shah Zafar Marg, New Delhi, India.

E-mail: drakashmalik28@gmail.com

PEDIATRICS (ISSN Numbers: Print, 0031-4005; Online, 1098-4275).

Copyright 2013 by the American Academy of Pediatrics

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have

no nancial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Supported by the Indian Council of Medical Research,

Department of Health Research (Ministry of Health and Family

Welfare), Government of India. Reference No. 3/2/2011/PG-thesis-

MPD-10.

e46 MALIK et al

at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on April 17, 2014 pediatrics.aappublications.org Downloaded from

Zinc is required for multiple cellular

tasks and the immune system depends

on the sufcient availability of this es-

sential trace element.

1

Zinc deciency

is common in several developing coun-

tries, including India. This is because the

commonly consumed staple foods have

lowzinc contents andare richinphytates,

which inhibit the absorption and utiliza-

tion of zinc.

2

Randomized controlled trials

have shown that zinc supplementation

during acute diarrhea reduces the du-

ration and severity, as well as the

incidence of subsequent diarrheal epi-

sodes.

37

However, recently published

meta-analyses conclude that pro-

phylactic zinc supplementation signi-

cantly reduces the incidence of diarrhea

only in children .12 months of age.

810

Because the incidence of diarrhea is

comparatively high in children 6 to 12

months of age (4.8 episode per year),

11

coinciding with the starting of comple-

mentary feeding, the current study

aimed to evaluate whether zinc pro-

phylaxis for a short duration has any

role in reducing the morbidity due to

diarrhea in this age group. Although the

original trial included additional out-

comes, such as acute respiratory tract

infections and growth, the results of

these will be reported separately.

METHODS

Study Setting and Participants

This is a community-based, randomized,

double-blind, parallel-arm placebo-

controlled trial, conducted from Jan-

uary 1, 2011, to January 15, 2012. We

included all children 6 to 11 months of

age residing in Gokulpuri, an urban

resettlement colony in the northeast dis-

trict of Delhi, India, who were likely to stay

until thecompletionof thestudy. Gokulpuri

has 2500 houses dividedinto 4 blocks, A,

B, C, and D, with a predominantly migrant

population of 23 000. Most of the pop-

ulation belongs to the middle and lower

socioeconomic strata. To achieve the -

nal sample size, additional children were

recruited from the similar adjacent area

of Gangavihar. The study was approvedby

the Institutional Ethical Committee of

Maulana Azad Medical College, NewDelhi,

and Associated Lok Nayak Hospitals. The

trial is registered with the Clinical Trial

Registry-India, number CTRI/2010/091/

001417.

We hypothesized that zinc prophylaxis

for 2 weeks would reduce the incidence

of diarrhea in subsequent months.

Thus, we excluded any child receiving

zinc supplement at the time of study or

who had received it in the preceding

3 months, those who were severely

malnourished, immune-decient, cur-

rently on steroid therapy, severely ill

requiring hospitalization, or of families

likely to migrate from the study area. A

house-to-house survey was done at the

beginning of the study to identify and

recruit the eligible infants. The study

purposewasexplainedtothefamilyand

aninformedconsent wasobtainedfrom

parents of all infants before they were

included in the trial. The recruitment

was done during the rst 2 weeks of

JanuaryandJuly, followedbysubsequent

5 months of follow-up, respectively. This

ensured the assessment of outcomes for

a complete year from January 2011 to

January 2012, to minimize the effect of

seasonality.

Randomization and Blinding

Random sequence was generated by

simple randomization method using

computer-generated random numbers

(Excel 2010). The bottles were labeled

with serial numbers in the Department

of Community Medicine, Maulana Azad

Medical College, by DKT, without the

knowledge of the eld investigator (AM).

The eld investigator and parents were

blinded to the treatment allocation and

unblinding was done at the end of the

follow-up period for all 272 infants.

Intervention

The zinc and placebo syrups were pre-

pared by Abyss Pharma (Delhi, India).

Each 5 mL of the preparation containing

placebo (syrup base) or zinc (20 mg

elemental zinc as zinc sulfate) was

packed in similar-looking bottles. The

syrups were of similar color, taste, and

consistency. During the survey, after

ascertainingthe eligibility andobtaining

informed consent, the infants were en-

rolled sequentially. The mother received

the bottles with prelabeled serial num-

bers. Theeldinvestigatoradministered

the rst dose of the intervention at the

time of enrollment and advised the

mother to give 5 mL of syrup (using

a standard 5-mL plastic spoon) daily to

the infant for the remaining 13 days.

Subsequently, visits were made on the

7th and the 14th days to ensure com-

pliance. If the syrup had not been given

regularly, a maximum of 1 week was

given to complete the dosages. We col-

lected data for any possible side effects

as reported by the caregivers during

these visits. To ensure that the childdid

not receive additional doses of zinc, we

provided mothers with identity cards

indicating the study title and that the

infants had received zinc syrup. These

cards were to be produced whenever

the child was taken to any medical

practitioner.

Outcomes and Follow-up

Theprimary outcomewas theincidence

of diarrhea per child-year. Diarrhea

was dened as 3 or more loose, liquid,

or watery stools or any change in

consistency or frequency of stools or

at least 1 loose stool containing blood

in a 24-hour period.

12

Secondary out-

comes included incidence density of

acute diarrhea, dysentery, and persis-

tent diarrhea; duration of diarrhea;

and side effects. Acute diarrhea was

dened as an episode of diarrhea

lasting up to 14 days. If an episode

lasted for .14 days, it was dened as

persistent diarrhea.

12

The episode was

classied as dysentery if the stool con-

tained blood.

12

Duration was assessed

as the number of days with diarrhea

ARTICLE

PEDIATRICS Volume 132, Number 1, July 2013 e47

at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on April 17, 2014 pediatrics.aappublications.org Downloaded from

and as mean number of days a di-

arrheal episode lasted. A baseline as-

sessment (Table 1) was done at the time

of recruitment, which included weight

and length measurements using a

Salter weighing scale (up to 100 g

[Model no. 235 6M; Salter India Ltd,

Daryaganj, New Delhi, India]) and an

Infantometer (up to 1 mm[model no: AM

1744; ATICO Medical Pvt Ltd, Haryana,

India]) respectively. All the outcomes

were assessed by a trained eld

investigator.

Follow-up for diarrhea began on the

15th day after intervention. Each child

was followed-up fortnightly 63 days

and the follow-up continued for 5

months after the completion of zinc/

placebo supplementation. At each

follow-up, the mother/caregiver was

asked about the occurrence of di-

arrhea during the previous 15 days.

Recovery from a diarrheal episode was

considered when the last day of di-

arrhea was followed by a 72-hour

diarrhea-free period.

6

Subsequent epi-

sodes were considered to be new di-

arrheal episodes.

Sample Size

The sample size was calculated taking

into account 4 primary outcomes: de-

crease in incidence of diarrhea, acute

respiratory tract infections, and in-

crease in length and weight. For di-

arrhea, previous studies in similar

populations estimated an incidence of

9.1 episodes (SD = 4.5) per child-year.

7,9

Thus, for a 20% reduction in the

incidence of diarrhea (a = 0.05 and

power 80%), we required 90 infants in

each group. However, the largest

sample size required (for acute re-

spiratory tract infection) was 258; thus,

we recruited the entire population of

216 infants from Gokulpuri and an

additional 56 infants from Gangavihar

(total = 272). The outcomes for di-

arrhea were assessed for all recruited

infants.

Statistical Analysis

Thedatawerecollectedandcheckedfor

accuracy on a daily basis and entered

into SPSS version 16 (IBM SPSS Sta-

tistics, IBM Corporation, Chicago, IL).

The incidence density was expressedas

episodes per child per year. The counts

were expressed by means and SD.

Difference between means was tested

using t-test, for normally distributed

data, or Mann-Whitney U test, for skewed

data.

Generalized estimating equations were

used to obtain an incident rate ratio

(IRR) with 95% condence intervals

(CIs), to compare monthwise number

of episodes and duration of diarrhea

using Poisson log linear distribution,

by intention-to-treat analysis. The ex-

changeable working correlation matrix

was selected for all the outcomes. We

included all children who had taken at

least 2 doses of the intervention for the

analyses. The follow-up visits for which

the infant outcomes were not available

were imputed using the worst-case (2

episodes of diarrhea) and best-case

scenarios (no episodes). However, this

did not change the study results; thus,

we present in this article results from

complete data set analysis. We decided

to adjust the IRRs for covariates that

appeared to be different at baseline in

the 2 groups. We also decided to com-

pare the monthwise mean episodes of

diarrhea in the 2 groups.

Socioeconomic status was assessed by

using the Modied Kuppuswamy Scale

(based on education and occupation of

family head and total family income)

modied for Consumer Price Index for

industrial workers of India for 2011.

13

The z-scores for length and weight were

calculated by using World Health Orga-

nization reference tables for length and

weight.

14,15

Observation and Results

From a total of 3155 households iden-

tied during the house to house survey,

we assessed 272 infants for eligibility

(Fig 1). As there were no exclusions and

refusals, all the infants were recruited.

A total of 141 infants received zinc

and 131 received placebo. Both groups

shared similar baseline characteristics

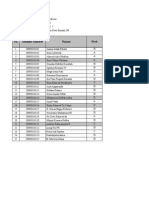

TABLE 1 Baseline Characteristics of the Study Subjects at the Time of Recruitment

Characteristic Zinc (n = 141) Placebo (n = 131)

Gender, n (%)

Male 67 (47.5) 68 (51.9)

Female 74 (52.5) 63 (48.1)

Age, mo, mean 6 SD 8.77 6 1.73 8.76 6 1.86

Socioeconomic status, n (%)

Upper 4 (2.8) 4 (3.1)

Upper Middle 39 (27.7) 30 (22.9)

Lower Middle 65 (46.1) 58 (44.3)

Lower 33 (23.4) 39 (29.8)

Average oor space per person, square meters 6 SD 7.75 6 4.13 8.26 6 5.21

Household water purication device, n (%)

Yes 31 (22.0) 23 (17.6)

No 110 (78.0) 108 (82.4)

Feeding type, n (%)

Exclusive breastfeeding 13 (9.2) 16 (12.2)

Complementary feeding 12 (8.5) 11 (8.4)

Both 116 (82.3) 104 (79.4)

Length, cm, mean 6 SD 67.4 6 3.86 67.6 6 3.82

Mean z score 21.76 6 1.46 21.69 6 1.48

Stunted (,2Z WHO) , n (%) 51 (36.0) 54 (41.0)

Weight, kg, mean 6 SD 7.26 6 1.1 7.21 6 1.2

Mean Z score 21.50 6 1.15 21.58 6 1.21

Wasted (,2Z WHO) , n (%) 44 (31.2) 53 (41.0)

WHO, World Health Organization.

e48 MALIK et al

at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on April 17, 2014 pediatrics.aappublications.org Downloaded from

(Table 1). Seven families (n = 4 in the

zinc group and n = 3 in the placebo

group, respectively) migrated during

the study period. The mean number of

follow-ups was 10 in each group (zinc:

10.0 6 0.75, placebo: 10.0 6 0.76, P =

.721). The nal analyses included 134

infants in the zinc group and 124 in the

placebo group, who had completed the

study. A total of 19 infants (13.5%) in

the zinc group and 26 infants (20%)

in the placebo group were given an

additional 1 week to complete the in-

tervention, as they were found to be

initially noncompliant.

Effect on Diarrhea

Zincsupplementationfor14dayscaused

a signicant reduction in the number of

episodes of diarrhea. Of the total 829

episodes observed, 329 episodes oc-

curred in the zinc group and 500 in the

placebo group, accounting for an in-

cidence of 6.07 and 9.90 per child year

respectively, at the end of 5 months

(Table 2). Generalized estimating equa-

tion regression model showed that there

was a reduction of 39% (adjusted IRR

0.61, 95% CI 0.530.71) in episodes of

diarrhea in the zinc group as compared

with the placebo group after the model

was adjusted for wasting.

When types of diarrhea were analyzed

separately (Table 2), we found a signif-

icant decrease of 31% in the episodes

of acute diarrhea (adjusted IRR 0.69,

95% CI 0.590.81), 70% in the episodes

of persistent diarrhea (adjusted IRR

0.30, 95% CI 0.170.51), and more than

95% in the episodes of dysentery (ad-

justed IRR 0.03, 95% CI 0.010.24) in the

zinc group.

Zinc supplementation led to a signicant

reductionof 39%(adjustedrateratio[RR]

0.61, 95% CI 0.540.69) in overall days

with diarrhea. There was also a signi-

cant reduction of 36% in duration per

episode of diarrhea (adjusted RR 0.64,

95% CI 0.560.74) observed in the zinc

group (Table 3).

Zinc signicantly reduced the mean

episodes of diarrhea for each of the

5 months (Table 4). However, the level of

signicance decreased after the third

month.

Side Effects

Reported side effects were diarrhea,

vomiting, and constipation. The per-

centage of children reporting these

were 9.0%, 10.4%, and1.5%, respectively,

in the zinc group and 7.3%, 4.8%, and0%,

respectively, in the placebo group, and

the difference was nonsignicant in the

2 groups.

Onedeathduetodiarrheawasreportedin

thezincgroup3monthsafterrecruitment.

Verbal autopsy revealed severe de-

hydrationduetononadministrationof oral

rehydrationsolutionortheavailablehome

uids were the cause of death. The fact

that the death took place 3 months after

intervention, and the incorrect man-

agement revealed in the verbal autopsy,

rules out any possible role of zinc.

DISCUSSION

In the current trial, we report that

prophylactic zinc supplementation for

2 weeks signicantly reduced the in-

cidence and duration of diarrhea dur-

ing follow-up of 5 months. Although we

studied additional outcomes (ie, acute

respiratory tract infections andgrowth),

the results of these will be reported

separately.

Zinc depletion leads to upregulation of

neuropeptides, such as cyclic guanosine

monophosphate, and acute-phase reac-

tants, such as interleukin 1, which cre-

ates secretory conditions in the intestine

leading to diarrheal episodes.

16

Thus,

zinc prophylaxis in zinc-decient pop-

ulations reduces diarrheal morbidity.

The major limitation of this study is that

serum zinc levels were not done to as-

sess the deciency and the subsequent

effect onserumzinclevels. Nevertheless,

previous studies in similar populations

FIGURE 1

Trial Prole.

ARTICLE

PEDIATRICS Volume 132, Number 1, July 2013 e49

at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on April 17, 2014 pediatrics.aappublications.org Downloaded from

of Delhi have shown high prevalence of

zinc deciency (normal: 11.522.2 mM)

to the extent of 73.3% for values

,10.4 mM and 33.8% for values ,9.0

mM.

3

Moreover, in our study, the pro-

portion of stunted infants was .20%,

which suggests an elevated risk of zinc

deciency, because stunting is a proxy

indicator of zinc deciency in population

studies.

17

Also, baseline data on in-

cidence density of diarrhea in this age

group were not available.

Among the studies in which short-

course zinc prophylaxis of 2 weeks

was used, only 1 study had shown sig-

nicant reduction in the incidence

of diarrhea in a 12- to 35-month age

group.

18

Previous studies, which were

carried out in infants of 6 to 11 months,

have shown similar results to the

current trial but after continuous zinc

supplementation.

1922

One of these tri-

als was carried out in a cohort of low

birth weight infants.

20

Trials have also

shown the effectiveness of continuous

zinc prophylaxis among wider age groups

(641 months and 635 months, re-

spectively), but subgroup analysis for

children ,12 months of age was not

done.

23,24

In a large study done in a sim-

ilar population of Delhi as the current

trial, zinc prophylaxis of 4 months was

found to be effective only in children .12

months of age.

25

Thus, unlike the previous

studies, the current trial showed that

short-course zinc prophylaxis signi-

cantly reduced diarrheal incidence in an

age group of 6 to 11 months.

Zinc prophylaxis was shown to reduce

the incidence of diarrhea in both con-

tinuous as well as short-course sup-

plementationtrials, in2meta-analyses.

8,9

However, the benecial effect was lim-

ited to children .12 months of age.

In the current trial, a signicant re-

duction of days with diarrhea per child

and duration per episode of diarrhea

was observed. In contrast, results of 2

previous trials have shown no effect of

continuous zinc prophylaxis on the

duration of diarrhea. Of these, 1 study

was done in the age group of 6 to

9 months and another in the age group

of 18 to 36 months.

19,26

Of the 2 meta-

analyses, 1 with continuous zinc sup-

plementation trials showed fewer total

days with diarrhea,

27

whereas the other,

which included studies with continuous

and short-course zinc supplementa-

tion, showed no effect on duration of

diarrhea.

7

A signicant reduction in incidence

was seen when diarrhea was further

classied into acute diarrhea, persis-

tent diarrhea, and dysentery in the

current trial. In the past, only 1 study

concluded that the incidence of acute

diarrhea was reduced signicantly by

zinc supplementation, but in a wider

age group (635 months).

28

Three

studies, which had a similar age group

or analyzed results for children ,12

months of age, showed no signicant

decrease in persistent diarrhea in

the zinc group.

6,22,24

Although both

the meta-analyses show that risk of

persistent diarrhea did decrease

with zinc supplementation, subgroup

analysis for the 6 to 11 months

age group is not available.

9,27

Also

one of these meta-analyses included

studies with continuous zinc supple-

mentation only. Regarding dysentery,

only 1 study showed signicant re-

duction in incidence of dysentery fol-

lowing zinc supplementation, that too

in a wide age group of 6 to 35 months

with continuous supplementation.

24

TABLE 2 Effect of Zinc Supplementation on Incidence of Diarrhea on the Study Subjects

Intervention Child Years

Observed

Incidence

(Episodes Child

1

year

21

)

Crude IRR

(95% CI)

Adjusted IRR

a

(95% CI)

All forms of diarrhea

Zinc 54.08 6.07 0.61 (0.560.74) 0.61 (0.530.71)

Placebo 50.25 9.90 1.00 1.00

Acute diarrhea

Zinc 54.08 5.77 0.68 (0.570.83) 0.69 (0.590.81)

Placebo 50.25 8.33 1.00 1.00

Persistent diarrhea

Zinc 54.08 0.28 0.29 (0.170.51) 0.30 (0.180.53)

Placebo 50.25 1.01 1.00 1.00

Dysentery

Zinc 54.08 0.02 0.032 (0.0040.24) 0.030 (0.010.24)

Placebo 50.25 0.58 1.00 1.00

a

Adjusted for wasting.

TABLE 3 Effect of Zinc Supplementation on Days with Diarrhea and Duration per Episode of

Diarrhea

Duration Intervention P Value

b

Crude RR

(95% CI)

Adjusted RR

c

(95% CI)

Zinc

(n = 118)

a

Placebo

(n = 116)

a

Mean 6SD of days with diarrhea 10.10 6 7.06 23.19 6 13.8 ,.001 0.60 (0.530.76) 0.61 (0.540.69)

Mean 6 SD days per episode 3.60 6 2.23 5.34 6 2.16 ,.001 0.63 (0.550.77) 0.64 (0.560.74)

RRrate ratio.

a

The children with 0 episodes were excluded.

b

Mann-Whitney U test, P , .05 considered signicant.

c

Adjusted for wasting.

TABLE 4 Monthwise Episodes of Diarrhea in

the 2 Study Groups

Month Zinc Placebo P Value

a

Mean (SD) Mean (SD)

First 0.44 (0.60) 0.85 (0.84) ,.0001

Second 0.40 (0.56) 0.83 (0.87) ,.0001

Third 0.49 (0.65) 0.88 (0.77) ,.0001

Fourth 0.58 (0.65) 0.82 (0.78) .014

Fifth 0.61 (0.80) 0.77 (0.73) .037

a

Mann-Whitney U test, P , .05 considered signicant.

e50 MALIK et al

at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on April 17, 2014 pediatrics.aappublications.org Downloaded from

A study with short-course zinc sup-

plementation showed a nonsignicant

reduction in incidence of dysentery

in the age group of 12 to 35 months.

18

Of the 2 meta-analyses, 1 is in agree-

ment with the current trial, although

the age group is wide in this meta-

analysis and studies with only con-

tinuous zinc supplementation have

been included.

9,27

Among the previous studies in similar

populations, we found that 1 study

may have insufcient power to detect

a signicant decrease in diarrhea

morbidity in infants 6 to 11 months of

age.

25

In other studies, zinc pro-

phylaxis was given to a subset of the

population that had already received

therapeutic zinc for acute diarrhea,

which might have led to reduced ef-

fectiveness of the subsequent zinc

prophylaxis.

5,7,24,28

However, the cur-

rent study was done in a population

that had not received zinc supple-

mentation for the preceding 3 months,

was apparently healthy, and had

a high proportion of wasted and

stunted infants. This, coupled with the

fact that the maximum burden of di-

arrhea is seen in the age group of 6

to 11 months,

11

may have been re-

sponsible for such signicant results

in the current study.

CONCLUSIONS

Previous trials and meta-analyses have

shown the benecial effect of zinc

prophylaxis on diarrhea either by

continuous supplementation for a long

duration, ranging from 3 months to

1 year, or in age groups of .12 months.

The current study was able to show

signicant reduction in diarrhea mor-

bidity in infants of 6 to 11 months,

even 5 months after short-course zinc

prophylaxis.

The advantage of zinc given as a

community-based prophylactic interven-

tion is that all children in the target

population will be covered. This in turn

will reduce the overall incidence of

diarrhea in the community compared

with administration of zinc only to

children who seek treatment for di-

arrhea. This is because many children

suffering from diarrhea may not come

to a health facility, as is common in the

slum populations, and thus keep suf-

fering from repeated episodes of di-

arrhea. The difculty of having to give

zinc to apparently healthy children is

that the delivery strategy has to be

community based, thus requiring ad-

ditional time and work on the part

of the health workers/community

volunteers.

The results of this study have important

cost and operational implications, as

short-course prophylaxis of zinc in an

adequate dose might be more feasible

than continuous therapies.

The results of this study may be

extrapolated to similar zinc-decient

populations only. Future trials on the

effect of zinc prophylaxis on diarrhea

should concentrate on zinc-decient

pockets in both developed and de-

veloping countries. It is desirable that

such trials follow a standardized pro-

cedureregardingthedurationanddose

of zinc prophylaxis. This would ensure

that policy makers have reliable and

valid evidence to implement zinc pro-

phylaxis programs for those child

populations that will benet the most

from them.

REFERENCES

1. Beisel WR. Single nutrients and immunity.

Am J Clin Nutr. 1982;35(suppl 2):417468

2. Black RE. Zinc deciency, immune function,

and morbidity and mortality from in-

fectious disease among children in de-

veloping countries. Food Nutr Bull. 2001;22:

155162

3. Baqui AH, Black RE, El Arifeen S, et al. Effect

of zinc supplementation started during

diarrhea on morbidity and mortality in

Bangladeshi children: community random-

ized trial. BMJ. 2002;325(7372):1059

4. Walker CL, Black RE. Zinc for the treatment

of diarrhoea: effect on diarrhoea morbid-

ity, mortality and incidence of future epi-

sodes. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(suppl 1):

i63i69

5. Sazawal S, Black RE, Bhan MK. Effect of zinc

supplementation during acute diarrhea on

duration and severity of the episode

a community based double-blind controlled

trial. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:839844

6. Sazawal S, Black RE, Bhan MK, et al. Zinc

supplementation reduces the incidence of

persistent diarrhea and dysentery among

low socioeconomic children in India. J Nutr.

1996;126(2):443450

7. Sazawal S, Black RE, Bhan MK, Jalla S,

Sinha A, Bhandari N. Efcacy of zinc sup-

plementation in reducing the incidence and

prevalence of acute diarrheaa community-

based, double-blind, controlled trial. Am J

Clin Nutr. 1997;66(2):413418

8. Brown KH, Peerson JM, Baker SK, Hess SY.

Preventive zinc supplementation among

infants, preschoolers, and older prepubertal

children. Food Nutr Bull. 2009;30(suppl 1):

S12S40

9. Bhutta ZA, Black RE, Brown KH, et al. Pre-

vention of diarrhea and pneumonia by zinc

supplementation in children in developing

countries: pooled analysis of randomized

controlled trials. Zinc Investigators Col-

laborative Group. J Pediatr. 1999;135(6):

689697

10. Brown KH, Rivera JA, Bhutta Z, et al; In-

ternational Zinc Nutrition Consultative

Group (IZiNCG). Assessment of the risk of

zinc deciency in populations. Food Nutr

Bull. 2004;25(1 suppl 2):S99S203

11. Kosek M, Bern C, Guerrant RL. The global

burden of diarrhoeal disease, as estimated

from studies published between 1992 and

2000. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81:

197204

12. World Health Organization. Diarrhoeal dis-

ease. Available at: www.who.int/mediacentre/

ARTICLE

PEDIATRICS Volume 132, Number 1, July 2013 e51

at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on April 17, 2014 pediatrics.aappublications.org Downloaded from

factsheets/fs330/en/index.html. Accessed

October 7, 2010

13. Kuppuswamy B. Manual of Socioeconomic

Status (Urban). Delhi, India: Manasayan; 1981

14. World Health Organization. Child growth

standards. Weight-for-age. Available at: www.

who.int/childgrowth/standards/weight_for_

age/en/index.html. Accessed July 23, 2011

15. World Health Organization. Child growth

standards. Length/height-for-age. Available

at: www.who.int/childgrowth/standards/

height_for_age/en/index.html. Accessed

July 23, 2011

16. Wapnir RA. Zinc deciency, malnutrition

and the gastrointestinal tract. J Nutr. 2000;

130(suppl 5S):1388S1392S

17. de Benoist B, Darnton-Hill I, Davidsson L,

Fontaine O, Hotz C. Conclusions of the joint

WHO/UNICEF/IAEA/IZiNCG interagency meet-

ing on zinc status indicators. Food Nutr

Bull. 2007;28(suppl 3):S480S484

18. Rahman MM, Vermund SH, Wahed MA,

Fuchs GJ, Baqui AH, Alvarez JO. Simulta-

neous zinc and vitamin A supplementation

in Bangladeshi children: randomised dou-

ble blind controlled trial. BMJ. 2001;323

(7308):314318

19. Ruel MT, Rivera JA, Santizo MC, Lnnerdal B,

Brown KH. Impact of zinc supplementation

on morbidity from diarrhea and respiratory

infections among rural Guatemalan chil-

dren. Pediatrics. 1997;99(6):808813

20. Sur D, Gupta DN, Mondal SK, et al. Impact of

zinc supplementation on diarrheal mor-

bidity and growth pattern of low birth

weight infants in Kolkata, India: a ran-

domized, double-blind, placebo-controlled,

community-based study. Pediatrics. 2003;

112(6 pt 1):13271332

21. Brooks WA, Santosham M, Naheed A, et al.

Effect of weekly zinc supplements on in-

cidence of pneumonia and diarrhoea in

children younger than 2 years in an urban,

low-income population in Bangladesh:

randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;

366(9490):9991004

22. Long KZ, Montoya Y, Hertzmark E, Santos JI,

Rosado JL. A double-blind, randomized,

clinical trial of the effect of vitamin A and

zinc supplementation on diarrheal disease

and respiratory tract infections in children

in Mexico City, Mexico. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;

83(3):693700

23. Gupta DN, Mondal SK, Ghosh S, Rajendran

K, Sur D, Manna B. Impact of zinc supple-

mentation on diarrhoeal morbidity in rural

children of West Bengal, India. Acta Pae-

diatr. 2003;92(5):531536

24. Penny ME, Marin RM, Duran A, et al. Ran-

domized controlled trial of the effect of

daily supplementation with zinc or multiple

micronutrients on the morbidity, growth,

and micronutrient status of young Peruvian

children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79(3):457

465

25. Bhandari N, Bahl R, Taneja S, et al. Sub-

stantial reduction in severe diarrheal mor-

bidity by daily zinc supplementation in

young north Indian children. Pediatrics.

2002;109(6). Available at: www.pediatrics.

org/cgi/content/full/109/6/e86

26. Rosado JL, Lpez P, Muoz E, Martinez H,

Allen LH. Zinc supplementation reduced

morbidity, but neither zinc nor iron sup-

plementation affected growth or body

composition of Mexican preschoolers. Am J

Clin Nutr. 1997;65:1319

27. Aggarwal R, Sentz J, Miller MA. Role of zinc

administration in prevention of childhood

diarrhea and respiratory illnesses: a meta-

analysis. Pediatrics. 2007;119(6):11201130

28. Larson CP, Nasrin D, Saha A, Chowdhury MI,

Qadri F. The added benet of zinc supple-

mentation after zinc treatment of acute

childhood diarrhoea: a randomized, double-

blind eld trial. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15

(6):754761

e52 MALIK et al

at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on April 17, 2014 pediatrics.aappublications.org Downloaded from

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2012-2980

; originally published online June 3, 2013; 2013;132;e46 Pediatrics

Akash Malik, Davendra K. Taneja, Niveditha Devasenapathy and K. Rajeshwari

Infants of 6 to 11 Months

Short-Course Prophylactic Zinc Supplementation for Diarrhea Morbidity in

Services

Updated Information &

ml

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/132/1/e46.full.ht

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

ml#ref-list-1

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/132/1/e46.full.ht

at:

This article cites 24 articles, 14 of which can be accessed free

Citations

ml#related-urls

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/132/1/e46.full.ht

This article has been cited by 1 HighWire-hosted articles:

Subspecialty Collections

cs_sub

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/therapeuti

Therapeutics

ogy_sub

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/pharmacol

Pharmacology

rology_sub

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/gastroente

Gastroenterology

the following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in

Permissions & Licensing

tml

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xh

tables) or in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures,

Reprints

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

Information about ordering reprints can be found online:

rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0031-4005. Online ISSN: 1098-4275.

Grove Village, Illinois, 60007. Copyright 2013 by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All

and trademarked by the American Academy of Pediatrics, 141 Northwest Point Boulevard, Elk

publication, it has been published continuously since 1948. PEDIATRICS is owned, published,

PEDIATRICS is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly

at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on April 17, 2014 pediatrics.aappublications.org Downloaded from

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Primary Surgery Versus Chemoradiotherapy For Advanced Oropharyngeal Cancers: A Longitudinal Population StudyDocument7 pagesPrimary Surgery Versus Chemoradiotherapy For Advanced Oropharyngeal Cancers: A Longitudinal Population StudyLuvita Amallia SyadhatinPas encore d'évaluation

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Incident Reporting FormDocument1 pageIncident Reporting FormCollin NguPas encore d'évaluation

- Neuro AnatomyDocument26 pagesNeuro AnatomylistiarsasihPas encore d'évaluation

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Pimsleur - French III - Course TextDocument14 pagesPimsleur - French III - Course TextFlávio José LindolfoPas encore d'évaluation

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Meningitis (Hal 225) Daftar Pustaka: Penyakit Jilid 2Document2 pagesMeningitis (Hal 225) Daftar Pustaka: Penyakit Jilid 2listiarsasihPas encore d'évaluation

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The New FriendDocument1 pageThe New FriendlistiarsasihPas encore d'évaluation

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- 603-606 12.27 Saima Hafeez KhokharDocument4 pages603-606 12.27 Saima Hafeez KhokharlistiarsasihPas encore d'évaluation

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Critical Review Qual Form1Document4 pagesCritical Review Qual Form1Ekhy BarryPas encore d'évaluation

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Spiritual LeadershipDocument11 pagesSpiritual Leadershipmisy_musyPas encore d'évaluation

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Migra inDocument9 pagesMigra inlistiarsasihPas encore d'évaluation

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- English ScoreDocument1 pageEnglish ScorelistiarsasihPas encore d'évaluation

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Cardiopulmonary System: Blok 16Document1 pageCardiopulmonary System: Blok 16listiarsasihPas encore d'évaluation

- Jurnal BSC 6Document5 pagesJurnal BSC 6FazaKhilwanAmnaPas encore d'évaluation

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Indonesia's Policy On CDM Implementation: Prasetyadi Utomo Ministry of Environment of IndonesiaDocument14 pagesIndonesia's Policy On CDM Implementation: Prasetyadi Utomo Ministry of Environment of IndonesialistiarsasihPas encore d'évaluation

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Blok 22Document1 pageBlok 22listiarsasihPas encore d'évaluation

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Fluid Resuscitation in Acute Illness PDFDocument2 pagesFluid Resuscitation in Acute Illness PDFlistiarsasihPas encore d'évaluation

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Role of Transrectal Ultrasound-Guided Biopsy in Diagnosis of Prostate CancerDocument7 pagesThe Role of Transrectal Ultrasound-Guided Biopsy in Diagnosis of Prostate CancerlistiarsasihPas encore d'évaluation

- Blok 24Document1 pageBlok 24listiarsasihPas encore d'évaluation

- Blok 22Document1 pageBlok 22listiarsasihPas encore d'évaluation

- 7 Ways To Love YourselfDocument7 pages7 Ways To Love YourselflistiarsasihPas encore d'évaluation

- Blok 21Document1 pageBlok 21listiarsasihPas encore d'évaluation

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Elective Block of Research: Blok 20Document1 pageElective Block of Research: Blok 20listiarsasihPas encore d'évaluation

- Blok 19Document1 pageBlok 19listiarsasihPas encore d'évaluation

- CLASSROOM LANGUAGE - Creating A WorkshopDocument5 pagesCLASSROOM LANGUAGE - Creating A WorkshoplistiarsasihPas encore d'évaluation

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Public Health and Community Medicine: Blok 23Document1 pagePublic Health and Community Medicine: Blok 23listiarsasihPas encore d'évaluation

- Blok 12Document1 pageBlok 12listiarsasihPas encore d'évaluation

- Blok 14Document1 pageBlok 14listiarsasihPas encore d'évaluation

- Blok 24Document1 pageBlok 24listiarsasihPas encore d'évaluation

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (120)

- Infection and Immunity: Blok 6Document1 pageInfection and Immunity: Blok 6listiarsasihPas encore d'évaluation

- Blok 18Document1 pageBlok 18listiarsasihPas encore d'évaluation

- Togaf Open Group Business ScenarioDocument40 pagesTogaf Open Group Business Scenariohmh97Pas encore d'évaluation

- Network Function Virtualization (NFV) : Presented By: Laith AbbasDocument30 pagesNetwork Function Virtualization (NFV) : Presented By: Laith AbbasBaraa EsamPas encore d'évaluation

- K3VG Spare Parts ListDocument1 pageK3VG Spare Parts ListMohammed AlryaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Special Warfare Ma AP 2009Document28 pagesSpecial Warfare Ma AP 2009paulmazziottaPas encore d'évaluation

- Gee 103 L3 Ay 22 23 PDFDocument34 pagesGee 103 L3 Ay 22 23 PDFlhyka nogalesPas encore d'évaluation

- What Is SCOPIC Clause - A Simple Overview - SailorinsightDocument8 pagesWhat Is SCOPIC Clause - A Simple Overview - SailorinsightJivan Jyoti RoutPas encore d'évaluation

- TEsis Doctoral en SuecoDocument312 pagesTEsis Doctoral en SuecoPruebaPas encore d'évaluation

- Final Module in Human BehaviorDocument60 pagesFinal Module in Human BehaviorNarag Krizza50% (2)

- Chain of CommandDocument6 pagesChain of CommandDale NaughtonPas encore d'évaluation

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Q & A Set 2 PDFDocument18 pagesQ & A Set 2 PDFBharathiraja MoorthyPas encore d'évaluation

- Laboratory Methodsin ImmnunologyDocument58 pagesLaboratory Methodsin Immnunologyadi pPas encore d'évaluation

- DMSCO Log Book Vol.25 1947Document49 pagesDMSCO Log Book Vol.25 1947Des Moines University Archives and Rare Book RoomPas encore d'évaluation

- List of Vocabulary C2Document43 pagesList of Vocabulary C2Lina LilyPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction To Philosophy of The Human Person: Presented By: Mr. Melvin J. Reyes, LPTDocument27 pagesIntroduction To Philosophy of The Human Person: Presented By: Mr. Melvin J. Reyes, LPTMelvin J. Reyes100% (2)

- Gamboa Vs Chan 2012 Case DigestDocument2 pagesGamboa Vs Chan 2012 Case DigestKrissa Jennesca Tullo100% (2)

- Monastery in Buddhist ArchitectureDocument8 pagesMonastery in Buddhist ArchitectureabdulPas encore d'évaluation

- Pediatric ECG Survival Guide - 2nd - May 2019Document27 pagesPediatric ECG Survival Guide - 2nd - May 2019Marcos Chusin MontesdeocaPas encore d'évaluation

- SANDHU - AUTOMOBILES - PRIVATE - LIMITED - 2019-20 - Financial StatementDocument108 pagesSANDHU - AUTOMOBILES - PRIVATE - LIMITED - 2019-20 - Financial StatementHarsimranSinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Contoh RPH Ts 25 Engish (Ppki)Document1 pageContoh RPH Ts 25 Engish (Ppki)muhariz78Pas encore d'évaluation

- Answers To Quiz No 19Document5 pagesAnswers To Quiz No 19Your Public Profile100% (4)

- Outline - Criminal Law - RamirezDocument28 pagesOutline - Criminal Law - RamirezgiannaPas encore d'évaluation

- HTTP Parameter PollutionDocument45 pagesHTTP Parameter PollutionSpyDr ByTePas encore d'évaluation

- Entrep Bazaar Rating SheetDocument7 pagesEntrep Bazaar Rating SheetJupiter WhitesidePas encore d'évaluation

- Thomas Noochan Pokemon Review Final DraftDocument6 pagesThomas Noochan Pokemon Review Final Draftapi-608717016Pas encore d'évaluation

- Sample A: For Exchange Students: Student's NameDocument1 pageSample A: For Exchange Students: Student's NameSarah AuliaPas encore d'évaluation

- Wwe SVR 2006 07 08 09 10 11 IdsDocument10 pagesWwe SVR 2006 07 08 09 10 11 IdsAXELL ENRIQUE CLAUDIO MENDIETAPas encore d'évaluation

- MPU Self Reflection Peer ReviewDocument3 pagesMPU Self Reflection Peer ReviewysaPas encore d'évaluation

- RSA ChangeMakers - Identifying The Key People Driving Positive Change in Local AreasDocument29 pagesRSA ChangeMakers - Identifying The Key People Driving Positive Change in Local AreasThe RSAPas encore d'évaluation

- Scientific Errors in The QuranDocument32 pagesScientific Errors in The QuranjibranqqPas encore d'évaluation

- Government College of Engineering Jalgaon (M.S) : Examination Form (Approved)Document2 pagesGovernment College of Engineering Jalgaon (M.S) : Examination Form (Approved)Sachin Yadorao BisenPas encore d'évaluation