Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Ivler Vs Hon. Modesto-San Pedro

Transféré par

Paolo MendioroTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Ivler Vs Hon. Modesto-San Pedro

Transféré par

Paolo MendioroDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

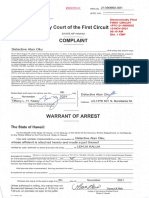

IVLER VS Hon.

MODESTO-SAN PEDRO

2010

Carpio

Petitioners Non-appearance at the Arraignment in

Criminal Case No. 82366 did not Divest him of Standing

to Maintain the Petition in S.C.A. 2803

Dismissals of appeals grounded on the appellants escape from custody or violation of the terms of his

bail bond are governed by the second paragraph of Section 8, Rule 124,

8

in relation to Section 1, Rule

125, of the Revised Rules on Criminal Procedure authorizing this Court or the Court of Appeals to "also,

upon motion of the appellee or motu proprio, dismiss the appeal if the appellant escapes from prison or

confinement, jumps bail or flees to a foreign country during the pendency of the appeal." The "appeal"

contemplated in Section 8 of Rule 124 is a suit to review judgments of convictions.

Petitioners Conviction in Criminal Case No. 82367

Bars his Prosecution in Criminal Case No. 82366

The accuseds negative constitutional right not to be "twice put in jeopardy of punishment for the

same offense"

13

protects him from, among others, post-conviction prosecution for the same offense,

with the prior verdict rendered by a court of competent jurisdiction upon a valid information.

14

It is not

disputed that petitioners conviction in Criminal Case No. 82367 was rendered by a court of

competent jurisdiction upon a valid charge. Thus, the case turns on the question whether Criminal

Case No. 82366 and Criminal Case No. 82367 involve the "same offense." Petitioner adopts the

affirmative view, submitting that the two cases concern the same offense of reckless imprudence.

The MeTC ruled otherwise, finding that Reckless Imprudence Resulting in Slight Physical Injuries is

an entirely separate offense from Reckless Imprudence Resulting in Homicide and Damage to

Property "as the [latter] requires proof of an additional fact which the other does not."

15

We find for petitioner.

Reckless Imprudence is a Single Crime,

its Consequences on Persons and

Property are Material Only to Determine

the Penalty

The two charges against petitioner, arising from the same facts, were prosecuted under the same

provision of the Revised Penal Code, as amended, namely, Article 365 defining and penalizing quasi-

offenses. The text of the provision reads:

..........

Reckless imprudence consists in voluntary, but without malice, doing or failing to do an act from which

material damage results by reason of inexcusable lack of precaution on the part of the person performing

or failing to perform such act, taking into consideration his employment or occupation, degree of

intelligence, physical condition and other circumstances regarding persons, time and place.

Simple imprudence consists in the lack of precaution displayed in those cases in which the damage

impending to be caused is not immediate nor the danger clearly manifest.

Indeed, the notion that quasi-offenses, whether reckless or simple, are distinct species of crime,

separately defined and penalized under the framework of our penal laws, is nothing new. As early as the

middle of the last century, we already sought to bring clarity to this field by rejecting in Quizon v. Justice

of the Peace of Pampanga the proposition that "reckless imprudence is not a crime in itself but simply a

way of committing it x x x"

17

on three points of analysis: (1) the object of punishment in quasi-crimes (as

opposed to intentional crimes); (2) the legislative intent to treat quasi-crimes as distinct offenses (as

opposed to subsuming them under the mitigating circumstance of minimal intent) and; (3) the different

penalty structures for quasi-crimes and intentional crimes:

The proposition (inferred from Art. 3 of the Revised Penal Code) that "reckless imprudence" is not a crime

in itself but simply a way of committing it and merely determines a lower degree of criminal liability is too

broad to deserve unqualified assent. There are crimes that by their structure cannot be committed

through imprudence: murder, treason, robbery, malicious mischief, etc. In truth, criminal negligence in our

Revised Penal Code is treated as a mere quasi offense, and dealt with separately from willful offenses. It

is not a mere question of classification or terminology. In intentional crimes, the act itself is punished; in

negligence or imprudence, what is principally penalized is the mental attitude or condition behind the act,

the dangerous recklessness, lack of care or foresight, the imprudencia punible. x x x x

Were criminal negligence but a modality in the commission of felonies, operating only to reduce the

penalty therefor, then it would be absorbed in the mitigating circumstances of Art. 13, specially the lack of

intent to commit so grave a wrong as the one actually committed. Furthermore, the theory would require

that the corresponding penalty should be fixed in proportion to the penalty prescribed for each crime

when committed willfully. For each penalty for the willful offense, there would then be a corresponding

penalty for the negligent variety. But instead, our Revised Penal Code (Art. 365) fixes the penalty for

reckless imprudence at arresto mayor maximum, to prision correccional [medium], if the willful act would

constitute a grave felony, notwithstanding that the penalty for the latter could range all the way from

prision mayor to death, according to the case. It can be seen that the actual penalty for criminal

negligence bears no relation to the individual willful crime, but is set in relation to a whole class, or series,

of crimes.

18

(Emphasis supplied)

This explains why the technically correct way to allege quasi-crimes is to state that their commission

results in damage, either to person or property

The doctrine that reckless imprudence under Article 365 is a single quasi-offense by itself and not merely

a means to commit other crimes such that conviction or acquittal of such quasi-offense bars subsequent

prosecution for the same quasi-offense, regardless of its various resulting acts, undergirded this Courts

unbroken chain of jurisprudence on double jeopardy as applied to Article 365 starting with People v.

Diaz,

25

decided in 1954. There, a full Court, speaking through Mr. Justice Montemayor, ordered the

dismissal of a case for "damage to property thru reckless imprudence" because a prior case against the

same accused for "reckless driving," arising from the same act upon which the first prosecution was

based, had been dismissed earlier. Since then, whenever the same legal question was brought before the

Court, that is, whether prior conviction or acquittal of reckless imprudence bars subsequent prosecution

for the same quasi-offense, regardless of the consequences alleged for both charges, the Court

unfailingly and consistently answered in the affirmative in People v. Belga....etc. These cases uniformly

barred the second prosecutions as constitutionally impermissible under the Double Jeopardy Clause.

The reason for this consistent stance of extending the constitutional protection under the Double

Jeopardy Clause to quasi-offenses was best articulated by Mr. Justice J.B.L. Reyes in Buan, where, in

barring a subsequent prosecution for "serious physical injuries and damage to property thru reckless

imprudence" because of the accuseds prior acquittal of "slight physical injuries thru reckless

imprudence," with both charges grounded on the same act, the Court explained:

34

Reason and precedent both coincide in that once convicted or acquitted of a specific act of reckless

imprudence, the accused may not be prosecuted again for that same act. For the essence of the quasi

offense of criminal negligence under article 365 of the Revised Penal Code lies in the execution of an

imprudent or negligent act that, if intentionally done, would be punishable as a felony. The law penalizes

thus the negligent or careless act, not the result thereof. The gravity of the consequence is only taken into

account to determine the penalty, it does not qualify the substance of the offense. And, as the careless

act is single, whether the injurious result should affect one person or several persons, the offense

(criminal negligence) remains one and the same, and can not be split into different crimes and

prosecutions

Hence, we find merit in petitioners submission that the lower courts erred in refusing to extend in his

favor the mantle of protection afforded by the Double Jeopardy Clause. A more fitting jurisprudence could

not be tailored to petitioners case than People v. Silva,

41

a Diaz progeny. There, the accused, who was

also involved in a vehicular collision, was charged in two separate Informations with "Slight Physical

Injuries thru Reckless Imprudence" and "Homicide with Serious Physical Injuries thru Reckless

Imprudence." Following his acquittal of the former, the accused sought the quashal of the latter, invoking

the Double Jeopardy Clause. The trial court initially denied relief, but, on reconsideration, found merit in

the accuseds claim and dismissed the second case. In affirming the trial court, we quoted with approval

its analysis of the issue following Diaz and its progeny People v. Belga:

....

...

One of the tests of double jeopardy is whether or not the second offense charged necessarily includes or

is necessarily included in the offense charged in the former complaint or information (Rule 113, Sec. 9).

Another test is whether the evidence which proves one would prove the other that is to say whether the

facts alleged in the first charge if proven, would have been sufficient to support the second charge and

vice versa; or whether one crime is an ingredient of the other. x x x

x x x x

Article 48 Does not Apply to Acts Penalized

Under Article 365 of the Revised Penal Code

The confusion bedeviling the question posed in this petition, to which the MeTC succumbed, stems from

persistent but awkward attempts to harmonize conceptually incompatible substantive and procedural

rules in criminal law, namely, Article 365 defining and penalizing quasi-offenses and Article 48 on

complexing of crimes, both under the Revised Penal Code. Article 48 is a procedural device allowing

single prosecution of multiple felonies falling under either of two categories: (1) when a single act

constitutes two or more grave or less grave felonies (thus excluding from its operation light felonies

46

);

and (2) when an offense is a necessary means for committing the other. The legislature crafted this

procedural tool to benefit the accused who, in lieu of serving multiple penalties, will only serve the

maximum of the penalty for the most serious crime.

In contrast, Article 365 is a substantive rule penalizing not an act defined as a felony but "the mental

attitude x x x behind the act, the dangerous recklessness, lack of care or foresight x x x,"

47

a single mental

attitude regardless of the resulting consequences. Thus, Article 365 was crafted as one quasi-crime

resulting in one or more consequences.

A becoming regard of this Courts place in our scheme of government denying it the power to make laws

constrains us to keep inviolate the conceptual distinction between quasi-crimes and intentional felonies

under our penal code. Article 48 is incongruent to the notion of quasi-crimes under Article 365. It is

conceptually impossible for a quasi-offense to stand for (1) a single act constituting two or more grave or

less grave felonies; or (2) an offense which is a necessary means for committing another. This is why,

way back in 1968 in Buan, we rejected the Solicitor Generals argument that double jeopardy does not

bar a second prosecution for slight physical injuries through reckless imprudence allegedly because the

charge for that offense could not be joined with the other charge for serious physical injuries through

reckless imprudence following Article 48 of the Revised Penal Code:

The Solicitor General stresses in his brief that the charge for slight physical injuries through reckless

imprudence could not be joined with the accusation for serious physical injuries through reckless

imprudence, because Article 48 of the Revised Penal Code allows only the complexing of grave or less

grave felonies. This same argument was considered and rejected by this Court in the case of People vs.

[Silva] x x x:

...

Indeed, this is a constitutionally compelled choice. By prohibiting the splitting of charges under Article

365, irrespective of the number and severity of the resulting acts, rampant occasions of constitutionally

impermissible second prosecutions are avoided, not to mention that scarce state resources are

conserved and diverted to proper use.

Hence, we hold that prosecutions under Article 365 should proceed from a single charge regardless of

the number or severity of the consequences. In imposing penalties, the judge will do no more than apply

the penalties under Article 365 for each consequence alleged and proven. In short, there shall be no

splitting of charges under Article 365, and only one information shall be filed in the same first level court.

55

Our ruling today secures for the accused facing an Article 365 charge a stronger and simpler protection of

their constitutional right under the Double Jeopardy Clause. True, they are thereby denied the beneficent

effect of the favorable sentencing formula under Article 48, but any disadvantage thus caused is more

than compensated by the certainty of non-prosecution for quasi-crime effects qualifying as "light offenses"

(or, as here, for the more serious consequence prosecuted belatedly). If it is so minded, Congress can re-

craft Article 365 by extending to quasi-crimes the sentencing formula of Article 48 so that only the most

severe penalty shall be imposed under a single prosecution of all resulting acts, whether penalized as

grave, less grave or light offenses. This will still keep intact the distinct concept of quasi-offenses.

Meanwhile, the lenient schedule of penalties under Article 365, befitting crimes occupying a lower rung of

culpability, should cushion the effect of this ruling.

WHEREFORE, we GRANT the petition.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5795)

- Annex 2. BSP Circular No. 730 and Frequently Asked QuestionsDocument9 pagesAnnex 2. BSP Circular No. 730 and Frequently Asked QuestionsPaolo MendioroPas encore d'évaluation

- Angeles Vs MAMAUAGDocument5 pagesAngeles Vs MAMAUAGPaolo MendioroPas encore d'évaluation

- Nuwhrain Apl Iuf Vs CADocument16 pagesNuwhrain Apl Iuf Vs CAPaolo MendioroPas encore d'évaluation

- Andres Vs Judge MajaduconDocument8 pagesAndres Vs Judge MajaduconPaolo MendioroPas encore d'évaluation

- Amante-Descallar Vs RamasDocument7 pagesAmante-Descallar Vs RamasPaolo MendioroPas encore d'évaluation

- Air Transportation Office Vs CADocument13 pagesAir Transportation Office Vs CAPaolo MendioroPas encore d'évaluation

- Shang Vs DcgiDocument5 pagesShang Vs DcgiPaolo MendioroPas encore d'évaluation

- Gonzales Vs RamosDocument3 pagesGonzales Vs RamosPaolo Mendioro100% (1)

- Mirpuri Vs CsDocument5 pagesMirpuri Vs CsPaolo MendioroPas encore d'évaluation

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- CHAPTER III Circumstances Affecting Criminal LiabilityDocument9 pagesCHAPTER III Circumstances Affecting Criminal Liabilityrosyelllll05Pas encore d'évaluation

- Frequently Asked Objective Questions in Criminal Law: Error in Personae and Praeter Intentionem? DoDocument49 pagesFrequently Asked Objective Questions in Criminal Law: Error in Personae and Praeter Intentionem? DoTori PeigePas encore d'évaluation

- 7 Felonies Filed Against Missoula High-Speed Chase SuspectDocument16 pages7 Felonies Filed Against Missoula High-Speed Chase SuspectNBC MontanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Martinez V MorfeDocument17 pagesMartinez V MorfeyousirneighmPas encore d'évaluation

- Criminal Law 1 NotesDocument14 pagesCriminal Law 1 NotesMaeBulang100% (1)

- SPL-cases Part 3-6 PDFDocument210 pagesSPL-cases Part 3-6 PDFjinuPas encore d'évaluation

- Handguns and Drugs - ArrestDocument2 pagesHandguns and Drugs - ArrestACSOtweetPas encore d'évaluation

- Dental Assistant Employment ApplicationDocument2 pagesDental Assistant Employment Applicationmarklola12Pas encore d'évaluation

- CRIMREV - SummaryDocument9 pagesCRIMREV - SummaryIssang BalasangPas encore d'évaluation

- Our Lost Border: Essays On Life Amid The Narco-Violence by Sarah Cortez and Sergio TroncosoDocument305 pagesOur Lost Border: Essays On Life Amid The Narco-Violence by Sarah Cortez and Sergio TroncosoArte Público Press0% (1)

- Letter To From CCRC Re-Amendment To RCCADocument3 pagesLetter To From CCRC Re-Amendment To RCCAmaustermuhlePas encore d'évaluation

- Julius Hall Appeal Against DisqualificationDocument14 pagesJulius Hall Appeal Against Disqualificationsavannahnow.comPas encore d'évaluation

- Criminal Law 1 (SY 2022-2023) SyllabusDocument28 pagesCriminal Law 1 (SY 2022-2023) SyllabusEugene ValmontePas encore d'évaluation

- Reckless ImprudenceDocument29 pagesReckless ImprudenceKriska Herrero TumamakPas encore d'évaluation

- Draft 1 With CommentsDocument13 pagesDraft 1 With Commentsapi-309897595Pas encore d'évaluation

- Lowndes County Voter Guide 2015Document10 pagesLowndes County Voter Guide 2015The Dispatch0% (1)

- Robert Barton Arrest ReportDocument3 pagesRobert Barton Arrest ReportKrystyna MayPas encore d'évaluation

- Translation and Terminology in The Development of African Languages The Case of Legal Terminology in Mbafeung Ijariie20766 PDFDocument10 pagesTranslation and Terminology in The Development of African Languages The Case of Legal Terminology in Mbafeung Ijariie20766 PDFKamta FomekongPas encore d'évaluation

- Martin Garcia CardielDocument2 pagesMartin Garcia CardielMcKenzie StaufferPas encore d'évaluation

- CLJ Criminal Law Book1 Atty JMFDocument494 pagesCLJ Criminal Law Book1 Atty JMFJed DizonPas encore d'évaluation

- Be It Enacted by The People of The State of Illinois, Represented in The General AssemblyDocument321 pagesBe It Enacted by The People of The State of Illinois, Represented in The General AssemblyNgân Hàng Ngô Mạnh TiếnPas encore d'évaluation

- People vs. Lizada - GR 143468-71 - Case DigestDocument2 pagesPeople vs. Lizada - GR 143468-71 - Case DigestJohn100% (2)

- TortsDocument155 pagesTortsJoy OrenaPas encore d'évaluation

- Cases On Criminal LawDocument191 pagesCases On Criminal LawMadz LuniePas encore d'évaluation

- Stages of Commission To Habitual DelinquencyDocument82 pagesStages of Commission To Habitual DelinquencyCamille CanlasPas encore d'évaluation

- People V ElarcosaDocument8 pagesPeople V ElarcosacessyJDPas encore d'évaluation

- Lehua Kalua ComplaintDocument12 pagesLehua Kalua ComplaintHonolulu Star-AdvertiserPas encore d'évaluation

- Trial Memorandum Guide-1Document11 pagesTrial Memorandum Guide-1Pinky De Castro Abarquez100% (2)

- United States v. Matthew Cordero, 4th Cir. (2015)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Matthew Cordero, 4th Cir. (2015)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Characteristics of Criminal LawDocument2 pagesCharacteristics of Criminal LawMikail Lee Bello100% (1)