Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

A Sustainable Future For Bangladeshi Shrimp

Transféré par

Md. Nurunnabi SarkerTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

A Sustainable Future For Bangladeshi Shrimp

Transféré par

Md. Nurunnabi SarkerDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

A sustainable future for shrimp

production in Bangladesh?

An ethical perspective on the conventional and organic

supply chain of shrimp aquaculture in Bangladesh.

Loni Hensler

SEAT - Sustaining Ethical Aquaculture Trade

2

A sustainable future for shrimp production in Bangladesh?

In recent years aquaculture has become more and more important for Asia, particularly in Bangladesh. It repre-

sents the second largest export industry for Bangladesh afer garments with 97% of the shrimp produced being

exported

1

, contributing about 4% to national GDP

2

and employing approximately 1.2 million people for produc-

tion, processing and marketing activities. Including their families, this sees approximately 4.8 million Bangladeshi

people directly dependent on this sector for their livelihood

3

. However, while the Bangladeshi shrimp industry

grows, it has also drawn some controversy. Some groups argue in favour of the industry, asserting that it pro-

duces nutritious food, releases the pressure on our overfshed oceans and meat production, and contributes to

the income of poor farmers who have no other possibilities for improving their situation. Others warn against

buying these shrimps and accuse the industry of a variety of abuses, ranging from environmental degradation, to

endangering local food security, to social considerations of low salaries, insecure work and bad working condi-

tions. Tese diverse aspects are all the more important considering that Bangladesh is the country with the highest

population density in the world, is one of the most threatened by climate change, and has a large number of people

below the poverty line. Consumers in countries importing Bangladeshi shrimp must navigate diferent one-sided

perspectives and rarely have a balanced opportunity to weigh advantages and disadvantages, to help them judge

what ethical and sustainable aquaculture production and consumption should look like. In this discussion the

voice of the most afected is rarely heard: the Bangladeshi farmers.

I spent three weeks in the feld in Bangladesh in December 2012 to get an impression of the shrimp value-chain

to be able to tell a story of Bangladeshi shrimp to European consumers

4

. In the following pages, I want to give my

perspective on whether the trade of shrimps from Bangladesh to Europe can be considered as sustainable and

ethical, based on the things I saw and the people I spoke to. Te narrative is my own, and tells the story of how

I came to discover the Bangladeshi shrimp sector. My background is in International Economics with a focus

on trade and sustainable (rural) development, and working experience in the feld of certifcation of sustainable

products and research on ethics in sciences and humanities. Before embarking on this project my knowledge of

shrimp aquaculture was limited to what I had read, and I had never been to Bangladesh before, so this presented

1 "#$%&''() (*+ ,-+. /01/

2Paque, M.M., Wahab, M. A., Llule, u.C. and Murray l.!. (2012)

3aul, 8.C. and vogl, C.8. (2012)

41hls research was conducLed accordlng Lo an approach comblnlng meLhods ln eLhnography and rapld rural appralsal,

whlch nd wldespread expresslon ln Lhe elds of developmenL sLudles for example. Cbservauons were made along

Lhe lengLh of Lhe value chaln, and Lhe surroundlng communlues, comblned wlLh seml-sLrucLured lnLervlews wlLh key

sLakeholders. lleen organlc and een convenuonal shrlmp famers were lnLervlewed abouL one hour each, wlLh Lhelr

selecuon allowlng for a dlverse accounLs as posslble, ranglng from large scale Lo small scale farmers, as well as from rlch

Lo poor. Moreover, one seml-lnLenslve large scale farmer was lnLervlewed. ln addluon Lhree experLs from Lhe praxls ln

favour and Lhree agalnsL shrlmp farmlng where lnLervlewed. Moreover Lwo rofessors from khulna unlverslLy enrlched

Lhe research perspecuve. 8eslde Lhe shrlmp farmers l lnLervlewed Lhree rlce farmers and slx mlddlemen ln dlerenL sell-

lng posluons, as well as a depoL owner and Lhe Crganlc Shrlmp rocesslng Company ln ShaLklra.

3

an eye-opening voyage of discovery for me too. Tis research was undertaken within the auspices of a European

Commission 7th-Framework-funded research project Sustaining Ethical Aquaculture Trade, or SEAT. Where

possible my own experiences of Bangladeshi shrimp were augmented with research results gleaned from SEAT,

but it must be emphasised that this narrative is my own, and is not representative of the whole SEAT Project.

Tis narrative will be as broad as possible, following the whole value-chain of conventional and organic shrimp in-

cluding the historical, social, economic, environmental and cultural aspects, and trying not to lose the people and

their stories between the facts. Let me share my journey, following one shrimp through the whole conventional

supply-chain, with a focus on the problems that arise, and listening to the farmers views. I will also present the

alternative presented by organic shrimp, which claims to be more environmentally friendly and socially just, and

demonstrate its opportunities and barriers.

Te story of a shrimp born into the conventional supply-chain in Bangladesh

Te history of the shrimp industry in Bangladesh is an explosive one, described both in terms of rapid growth and

growing pains. Te industry has certainly had a chequered past (see Box 1). Today, 250,000 - 300,000 Bangladeshi

shrimp farmers are producing about 170,000 million tons of shrimp per year

5

in a cultivation area of over 217,877

ha of land

6

, mainly in the districts around Khulna, Satkhira and Bagerhat in the south-west of Bangladesh. Tis

area for shrimp cultivation has doubled in the last 20 years. In total about 1.2 million people are working along the

entire shrimp production value-chain: growing, harvesting, transporting, processing and selling. Following the

whole value-chain of shrimp, I was truly amazed at how many hands are involved in bringing the shrimp from the

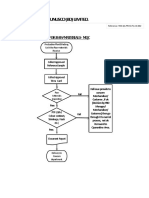

farmers pond to Europeans plates. But let us follow the life of one shrimp, step by step (see Figure 1).

3 llsherles 8esources Survey SysLem, 2007, clLed ln krul[sseneL. al., 2012

6Paque, M.M., Wahab, M. A., Llule, u.C. and Murray l.!. (2012)

8ox 1: A h|stor|ca| perspecnve, from subs|stence r|ce farm|ng to an exp|od|ng shr|mp |ndustry

Shrlmp farmlng ln 8angladesh ls a very young lndusLry. 1he lndusLry sLarLed by colncldence". AbouL 40 years

ago some small rlce farmers dlscovered LhaL Lhe markeL prlce for Lhe wlld shrlmp LhaL had naLurally enLered

Lhelr ponds was very hlgh, and sLarLed Lo dellberaLely collecL Lhe shrlmp fry from Lhe rlvers Lo be able Lo

culuvaLe shrlmp ln Lhelr ponds. As Lhe demand for shrlmp ln counLrles of Lhe global norLh lncreased ln Lhe

1980s, farmers sLarLed Lo lnLroduce sallne waLer lnLo Lhelr rlce elds Lo fosLer ourlshlng shrlmp farmlng. lL

was from Lhls polnL LhaL convenuonal shrlmp culuvauon sLarLed, and saw large farmers, pollucally lnuen-

ual people and organlzauons enLer Lhe secLor. A complex and chaouc sysLem of shrlmp selllng and process-

lng developed. AL Lhe same ume, lssues of land grabblng occurred as shrlmp farmlng became favoured as very

proLable. 1he landless populauons and marglnallzed farmers were parucularly aecLed, and were 'forced' Lo

leave and nd work caLchlng [uvenlle or posL larvae (L) shrlmp ln Lhe wlld. lrom Lhe 1980's onwards, lnLer-

nauonal and nauonal organlzauons sLarLed Lo supporL poor and marglnal rlce farmers Lo adopL shrlmp farm-

lng, and pushed Lhe lndusLry Lo new helghLs, Lhough unforLunaLely wlLhouL addresslng some of lLs lll-eecLs.

Whlle ln Lhe beglnnlng shrlmp farmlng was hlghly proLable, lL also became seen as very rlsky, wlLh vlral dlseases

enLerlng Lhe counLry from 1halland ln 1984 and desLroylng Lhe whole harvesL aL LhaL ume. Some research lnsu-

Luuons, llke Lhe 8angladesh 8lce 8esearch lnsuLuLe, sLarLed Lo look lnLo meLhods Lo reduce Lhe rlsk from Lhese

lnfecuons, lncludlng Lhrough crop roLauon and waLer LreaLmenL, buL Lhe rlsk from dlsease sull remalns Lo Lhls day.

As Lhe lndusLry maLured lL sLarLed Lo address lLs negauve lmpacLs, whlch were drawlng lncreaslng crluclsm

from boLh nauonal and lnLernauonal groups. 1he 8angladeshl governmenL banned Lhe removal of mangrove

foresLs Lhrough shlng ln 1989 and Lhe collecuon of wlld shrlmp fry ln 1993, Lo halL Lhe desLrucuon of man-

grove foresLs and rlver blodlverslLy. Shrlmp posL larvae (L) sLarLed Lo be grown ln speclal haLcherles. More

regulauon concernlng quallLy and Lhe use of pesucldes followed aer Lhe Luropean unlon banned Lhe lmporL

of shrlmp for Lhree monLhs ln 1997 due Lo unhyglenlc producuon, poor quallLy producLs and corrupL prac-

uces. Slnce 2003 lnLernauonal and local nCCs have ralsed quesuons on Lhe susLalnablllLy of Lhe secLor and

dlerenL governmenLal and non-governmenLal organlzauons were formed Lo lmprove Lhe quallLy of farmed

shrlmp, Lhelr LraceablllLy and Lhe soclal and envlronmenLal lmpacLs of Lhe secLor. Cne of Lhese ls Lhe Cr-

ganlc Shrlmp ro[ecL LhaL clalms Lo presenL a susLalnable alLernauve Lo Lhe convenuonal shrlmp producuon.

4

From the hatchery to the nursery

Our shrimp frst sees the light in this world in one of the 60 pri-

vate sector hatcheries in Coxs Bazar, in the south-east of Bangla-

desh, probably in January. A hatchery is where the shrimp eggs are

grown to the post-larvae (PL) stage. Te hatcheries have a system

of tanks for water treatment, and raise the small naupli (the frst

stage afer hatching) in aerated tanks, where algae and plankton

are encouraged to grow to feed them, before moving the naupli to

diferent ponds for the later stages of their growth. While many of

the PL used to be caught in the rivers, today wild fry collection is

prohibited to protect the local ecosystems. Now 80% of the shrimp

originate in hatcheries and only 20% are caught in the wild. Our

shrimp grows bigger and bigger before one day it is caught by a net

and transported by car, bus (80% survive) or airplane (100% survive) to the nursery in the cultivation areas in the

south-west of Bangladesh. Here our shrimp stays for some days to recover from the journey and become familiar

with the local water, before being released into its new home: green little ponds in traditional extensive

7

shrimp farms.

to the farm

Te farmer prepares the shrimp pond every winter and con-

structs stable dikes that allow a water depth of about 1.5m. With

a canal system, the farmer channels in the saline water from a

nearby river. In the pond, our shrimp lives together with other

aquatic species, including diferent species of fsh, crabs and

frogs; all living together in water rich with algae and plank-

ton that serve as food. Some shrimp are cultivated in semi-

saline water where they share their space with rice and other

fsh species. Te farmers call this polyculture production in

ghers. Te shrimp grows until it is about 4 months old, when it

has the urge to travel back to the sea to breed. When the moon

is in the correct phase and the tides are high, our shrimp decides to start its travel and swims around the pond to

fnd its way out. But the farmer has put net traps in the pond to trap our shrimp.

then via the middle-man

Early in the morning the farmer harvests our shrimp from the trap, and takes it to a nearby shrimp market in

a bag, where it is sold to a middle-man. Tere are a number of diferent routes for how the shrimp reaches the

processing plant:

1. A Local Purchaser is waiting somewhere on the street in the local vil-

lage close to the ponds. Te shrimp is weighed and then the farmer and

purchaser bargain about the price. Te purchaser normally gets 2 % in

commission. Te shrimp is then kept in a bag or bucket with water, until

it is taken in the afernoon to a depot.

2. A Foria, is a kind of middleman that waits in the local market for the

shrimp or collects it directly from the farm. Te shrimp is sorted and in-

spected on the foor before the farmer and Foria bargain about the price.

Te shrimp then stays in a bag without ice until it is taken to a depot at

lunch time or in the afernoon.

3. A Set is a kind of small store in the shrimp market, with a desk in front

of it. First the shrimp are weighed, then displayed on the desk and the

7 Pere a dlsuncuon can be made beLween exLenslve, seml-lnLenslve and lnLenslve aquaculLure based on Lhe levels

of lnpuLs of feed, ferullzer or energy, and Lhe sLocklng denslLy. lnLenslve aquaculLure Lyplcally supporLs Lhe maxlmum

posslble sLocklng denslLy, by relylng on commerclal feed and Lhrough oxygenaung Lhe ponds. LxLenslve aquaculLure has

sLocklng denslues closer Lo LhaL whlch mlghL occur 'naLurally', and largely encourage Lhe growLh of naLurally-growlng

planLs and plankLon as feed, wlLh Lhls aL umes supplemenLed by oLher locally-produced feeds llke cereals, or agrlculLural

by-producLs. no oxygen needs Lo be added Lo Lhe ponds.

5

Figure1: A representation of the conventional Bangladeshi shrimp supply chain

price is negotiated. As soon as it is sold, the weight and price is documented and the shrimp are stored in a box

with ice. Te owner of the Set gets a commission of 2-3%. From here the shrimp are taken to a depot. Normally

the farmers are paid the negotiated price, but sometimes farmers take out loans with the Set, for the preparation of

their pond for example, and in this case the farmer receives a lower price for the shrimp so as to pay back the loan.

8

4. A Sub-depot, is a small room somewhere in the village, where farmers can bring the shrimp. Here they are

weighed and then they bargain over the price. Once the price is agreed, it is written down and then the shrimp are

kept the shrimp in a small water container sometimes overnight before they are transported to the depot.

to the depot

Via all four routes, the shrimp fnds its way to a depot; a single room with some boxes and ice, where they are

weighed again and stored in ice. Tere our shrimp stays until a truck picks it up and takes it to one of 145 pro-

cessing plants (though only 65 are operational) which have a combined capacity of about 265,000 million tons.

Delivery to the processing plant can be once a day or every other day or even every third day.

and on to the processing plant.

Here it gets cold for our shrimp. It is washed and sorted by

an automatic machine, its head is removed by the processing

workers (mainly female), it is washed again, gutted and cleaned

inside, frozen, packed and storedready for a long trip to Eu-

rope (50.07%), the USA (26,8%), India (7,8%) or Japan (3,6%)

9

,

or for dinner in a middleclass Bangladeshi home (though only

3% are consumed within Bangladesh). Te shrimp from the

processing plant are monitored by the National Fish Inspec-

tion and Quality Control Service to make sure that they are of

a good quality, with no traces of pesticides or antibiotics. Tey

approve processing plants and take shrimp samples to a lab,

where they give permission for export or halt processing in case of pesticide residues. When our shrimp arrives

in Europe, it likely enters the retail or foodservice chain and is sold to a supermarket from where it fnally gets

prepared in a restaurant or private kitchen.

8noLe ln Lhls case Lhe 'SeL' ls acung as a small scale mlcro-lender wlLh Lhe farmers' currenL and fuLure shrlmp produc-

uon belng Lhe securlLy for Lhe small scale loans or credlL

9"#$%&''() (*+ ,-+. /01/

6

What are the issues facing the conventional Bangladeshi shrimp value-chain?

1+ Quality and Traceability

Te quality of Bangladeshi shrimp can in the majority of cases be considered as quite high at the time of harvesting,

because a signifcant number of farmers engage in extensive production which does not use any harmful chemi-

cals. Tis noted, there are still many farmers who use chemicals, especially if there is disease, and the high number

of small farmers makes general conclusions difcult. It is post-harvest that the quality of the shrimp can at times

deteriorate, for a number of reasons. First, the long and uncontrolled system of selling the harvested shrimp,

where the middlemen (foria, sub-depot and set) rarely store the shrimp with ice, but rather in unhygienic condi-

tions, sometimes for extended periods of time in warm temperatures. Second, as the weight and price agreed on

with the farmer is not documented, there is also a fnancial incentive to manipulate the weight of the shrimp by in-

jecting (dirty) water or gelatine into the body of the shrimp. Tird, when the shrimp arrive at the processing plant,

it is normally not possible to retrace where the shrimp has come from, how it was produced, who sold it at what

price to the depot, and how old it is. With this lack of traceability and the complex supply-chain, it makes quality

assurance impossible. Even the best processing plants cannot improve the quality of what arrives through their

doors. As conventional processing plants do not open their doors to foreigners, due to controversy surrounding

working conditions in the past, I could not visit them. However, there is some evidence that the conventional

processing plants do not always follow high hygienic standards.

/+ Te insecurity and powerlessness of the shrimp farmers

While prices between retailer and the processing plants are negotiated, at the lower end of the value-chain among

fry collectors and middlemen bargaining is very limited. Small farmers depend very ofen on larger, dominant

buyers and have very little ability to infuence the price

10

. Beside the fact that the farmers are mainly price takers,

they face some other disadvantages: Firstly, the price is very unstable and can fuctuate greatly. Secondly, farmers

lose a part of their proft because they have to pay a fee to the middlemen and the payment is irregular. Tirdly,

only rarely do they receive payments directly. Usually farmers need to wait between 2 weeks and up to 3 months

for payment, and sometimes they are never paid. Moreover, the payment is normally not documented, hindering

any transparency. For the farmer, especially if he is very poor and uneducated, this means a lot of stress selling

and bargaining the price in the market and then not having the security of receiving payment, making it impos-

sible to plan for the future, and even impossible to support his family in acceptable living conditions. Some of the

poorer farmers have had to take out loans, because they do not have the means to save money and are unable to

accommodate the irregular prices and payments on their own. Compared to the time when the farmers produced

rice, now only the richer farmers still have rice farming land and the poor have to buy all their rice at the market.

Terefore, in terms of food securety, many small-scale and poor farmers are not self-sufcient anymore.

10uSAlu 8angladesh, 2006

7

2+ Environmental issues and animal welfare

Shrimp farming increasing soil salinity

Shrimp production is highly criticized in the public discourse for its environmental impact, especially its efect

on the salinity of the soil

11

. Trough the construction of canals and the fooding of the former rice felds with salt

water, the soil quality is afected. Some people even equate these regions to deserts, because of the high levels

of salinity. Te Bangladesh Soil Research Institute describes the growth in saline areas and the rise of areas with

high salinity as truly alarming

12

. It afects mainly the coastal areas, where 30% of Bangladeshs cultivable land is

situated.

However it should be considered, that the reasons for this increase in salinity are numerous and the shrimp pro-

duction itself only contributes partly to this problem. Firstly, the efect of climate change has to be considered.

Bangladesh is one of the most afected countries from climate change

13

. With rising sea levels, and an increase

in extreme weather conditions, this sees salt water from the ocean surging further inland along the rivers, and

through an increase in temperature, the salinity in the rivers increases even more. Secondly, the fresh water con-

trol of India contributes signifcantly to salinity. Trough the embankment dam (Farakka Barrage)in India the

pressure of fresh water in the rivers decreases and allows seawater to extend further up-river.

With the increased salinity of the soil, rice farming becomes less productive, with rice having little tolerance for

saline soils. In some coastal regions agriculture is only possible once a year, during the wet seasons, whereas in

more fertile highland regions rice can be grown up to 3 or 4 times a year. Shrimp production can be seen as an ad-

aptation of former rice farmers to the changes in their environment; as rice production has become less proftable

on the low-lands, shrimp production has become a more suitable use of the land

14

. Moreover, while prices for rice

have been constant, the international demand for aquaculture products has risen sharply, providing farmers with

important market signals to swap rice farming for more proftable shrimp production in these areas. However,

this shrimp cultivation is contributing to higher levels of salinity in the ponds and surrounding areas, particularly

in the absence of water management best practice, such as alternating saline water in the ponds with fresh water,

or drying out the ponds during the winter months. Tis means that when farmers in an area start to use salt water

for shrimp production, their rice farming neighbours are ofen forced to also switch to aquaculture production,

since rice production becomes impossible.

Te main aim should be to identify the suitable area for

diferent types of production and use it for that in order to

be efcient and provide, in the end, enough food for every-

one. Te coastal areas are normally good for shrimp farm-

ing because of the salt water and shrimp. For the moment

the shrimp farming area should not be expanded artif-

cially, but the goal should be to increase the productivity

within the suitable areas in an environmentally friendly

way. Dr. Khandaker Anisul Hug, Professor at Khulna

University in Fisheries and Marine Resource Technology.

Te harmful use of chemicals in shrimp aquaculture

Te harmful use of fertilizer and pesticides in shrimp aquaculture can afect soil quality, the ground water and the

local ecosystem. Many farmers reported that they learned shrimp farming from their neighbours and that in case

of any problem in their pond; they visit the local chemical shop to ask for help. People I spoke to said that normally

the shopkeeper is not especially fuent in aquaculture best practice and is just steered by what is written on the

back of the bottle. I spoke with Dr. Khandaker Anisul Hug at Khulna University and he said:

Te main problem is the lack of information and education of the farmers, which as a consequence leads in some

cases to irresponsible actions like the wrong use of chemicals and poor water management. Training is neces-

11 See e.g. SSnC (hup://www.youLube.com/waLch?v=rlln48Sw?CL)

12Slehe Ahsan, Malnul eL al. (2012): Sallne Solls ln 8angladesh. Soll ferullLy AssessmenL, Soll degradauon, and lLs lm-

pacL on AgrlculLure rogram. Soll 8esource uevelopmenL lnsuLuLe, uhaka.

138rouwer aL al. (2007): Socloeconomlc vulnerablllLy and AdapLauon Lo LnvlronmenLal 8lsk: A Case SLudy of CllmaLe

Change and lloodlng ln 8angladesh

14rawn on Lhe oLher hand can be produced ln fresh or sllghLly sallne waLer l.e. bracklsh, LhaL's why lLs name ls also

Lhe lresh WaLer rawn

8

sary to emphasize the importance of environmentally friendly

production and to enable the farmer to follow good and ef-

fcient farming practices. But it has to be considered that this

is a general problem which is also true for modern monocul-

ture rice farming and waste management. Tese subjects and

broader environmental problems need to be integrated in the

whole educational system to raise awareness.

Generally in extensive traditional shrimp farming no ar-

tifcial feed is used, which reduces its impact on the natural

environment when compared to intensive farms. Across

the whole of Bangladesh there exist only four semi-in-

tensive shrimp farms, because they are considered as not

proftable, with a higher risk of disease and also higher input costs. To reduce the risk of diseases, the water

in semi-intensive farms is disinfected with chlorine, but this also removes most of the naturally-occurring

feed in the ponds (e.g. algae), which is then insufcient to support such high stocking densities. Te farmer

must therefore supply artifcial (pelletized) feed. Moreover the higher stocking densities and the use of arti-

fcial feed make it necessary to aerate the water by electric paddlewheels, to maintain healthy oxygen levels.

Terefore, the main increase in input costs of semi-intensive farming are associated with feed and electricity.

Impacts of aquaculture on biodiversity

Tere has also been some critique levelled at shrimp farming

for destroying the local biodiversity. But what I have seen from

the shrimp harvests were a huge range of diferent aquaculture

species in the pond, ranging from crabs and small insects, to a

variety of fsh. Some of these fnd their way naturally into the

ponds and some are stocked and grown deliberately. Terefore

aquaculture (meaning integrated polyculture) is a more appro-

priate term than shrimp production. Tis is confrmed by SEAT

project research

15

that notes that in most farms that were sur-

veyed there was a high biodiversity in the pond. Te larger, ed-

ible species of fsh contribute to about half of a farmers income

from the gher through sale on the local market, but they also

augment a familys own consumption and even provide food gifs for their relatives, friends and the poor. Te

smaller pond life serves as natural feed to the shrimp. Compared to modern monoculture rice production, shrimp

farming provides more security for the farmer in the form of a diversity of income options, and can be considered

more environmentally neutral. What is notable, however, is that the biodiversity of vegetation on the banks of the

ponds is reduced, because only salt tolerant plants can grow. Moreover shrimp farming in the early years went

hand in hand with the destruction of valuable mangrove forests, which represented a signifcant source of local

biodiversity and contributed to oxygen production. Now there are regulations protecting these mangrove forests.

Te welfare of farmed shrimp

Te welfare of the shrimp in shrimp farms is rarely considered

by shrimp producers or consumers. Animal welfare is most

commonly concerned with the well-being of animals relative

to their ability to feel pain, fear or sufering; ofen described in

terms of a hierarchy of species from those animals most able

to sufer like chimpanzees, down to those unable to sufer like

crustaceans or molluscs

16

. Using this hierarchy many see that

shrimp as invertebrates do not have the sophisticated nervous

system needed to experience feelings of sufering, with this

backed-up by the science for the time being

17

. Tis actually saw

well-known animal ethicist Peter Singer (1990) drawing a bot-

tom-line on this hierarchy somewhere between a shrimp and

13Carbonara (2012)

16Sande and Simonsen (1992)

17PasLeln, Scarfe and kunde (2003)

9

a mussel when considering which animals should be considered able to sufer. In this way, for those producers

and other in the value chain I spoke to animal welfare was not a very important consideration for shrimp farming.

However this noted, there are a number of factors that might stress shrimp and afect the quality of the shrimp

products, including the quality of the water in the farm and the stocking density, the quality of the feed, the way

the shrimp are transported, any outbreak of disease, and the way the shrimp are killed for processing

18

. Many of

these factors will by defnition afect the growth rates and well-being of the shrimp and then also their quality

within the post-harvest transportation phase. As such this in turn will efect market prices and the incomes and

proftability of the producers themselves. As such it is in their interest to be more concerned with welfare.

4. Social Issues: Working conditions, inequality and gender

Te efect of shrimp aquaculture on women and the landless

Tere are diferent views on the social impacts of shrimp farms.

While land-owners, including rice farmers, have been afected,

there has been a much more signifcant impact on the people

who depend on the work at the farms; the landless and margin-

al, small-scale farmers. Some research gives evidence that there

are fewer working opportunities in shrimp farming compared

to rice farming

19

, while other research shows that there is more

work available

20

. I myself came across this same disagreement in

my discussions with the Bangladeshi people. What they agree

on is that shrimp farming most heavily afects the landless and

poor women. As women traditionally worked in agriculture,

there is now less work for them. Some women also stated that

they preferred the work in the rice felds, because the casual labour on the shrimp farms is more physically demand-

ing. Employment along the shrimp supply-chain is usually characterized by insecure and seasonal casual labour in

farming, processing and fry catching. Moreover, there is widespread gender discrimination along the shrimp sup-

ply-chain, with women getting only about 60% of the wages men earn

21

, particularly in the processing plants where

60-80% of workers

22

are female. Te selling and auctioning, as well as farming is almost execusively done by men.

Food security

Shrimp is considered as good for the rich and bad for the

poor, particularly in terms of food security. Te landless

and small scale farmers are worst afected by the increase in

soil salinity, as their vegetable and fruit production is ham-

pered or more expensive. Tey become dependent on buying

their food from the market and need therefore a higher in-

come through daily labour. Also the quantity of wild fsh in

the rivers or homestead ponds is reduced, forcing them to

buy more at the market. Tis also leads to changes in social

interaction, as in Bangladesh the ability to present gifs to

guests, friends and relatives is considered as very important.

Everywhere I went the people were very happy if they could

ofer me some fresh fruit from their own garden. Overall polyculture and engaging in a variety of economic

activities is becoming more and more important; where families have a diversity of diferent livelihood strategies

this improves their security. Some small farmers would prefer growing rice, but as their neighbours switched

to shrimp farming they had to do the same. However, normally this was considered a proftable alternative.

18ConLe (2004)

19eg. uaua eL al. (2010) sLaLe LhaL Lhe work would be reduced Lo only 23 of Lhe work ln rlce farmlng, rlmavera 1997

found ouL, LhaL culLurlng one hecLor of an average rlce crop requlres around 76 worklng days whlle exLenslve shrlmp cul-

Lure only needs 43 worklng days

20e.g. SLelnberg (2012) concludes LhaL Lhe shrlmp lndusLry raLher lncreased labour opporLunlues Lhan decreased

(SLelnberg 2012: 24)

21SLelnberg 2012: p.17, uSAlu 8angladesh, 2006

22Ahmed eL al., 2008, clLed ln krul[ssen eL. al., 2012

10

Working conditions

Te working conditions at the farms and in the processing

plants have, especially in the past, been criticized due to long

working hours, a lack of work contracts, poor housing, child

labour and an unhealthy working environment. Even though

the Bangladesh government set minimum wages for workers

in the shrimp processing industry, a study of SAFE (2012) dis-

covered in interviews with 700 permanent and contract work-

ers in 2010 that nearly 25% of permanent workers and 75% of

contract workers did not get those minimum wages. Moreover

the majority did not receive breaks and meals as laid out in the

Bangladesh Labour Act 2006, nor did they receive their salary

in time. Furthermore, 96% of the respondents reported that

children/teenagers between 14-18 years were working in their plants

23

. As I could not visit a conventional process-

ing plant I cannot pass any personal judgment on this, but it has to be considered that bad working conditions,

gender discrimination and child labour are not a specifc problem of only the shrimp industry, but are endemic to

all industries in Bangladesh (compared to garments, leather, etc.

24

).

Broader questions on the sustainability of global food trade?

Finally, shrimp production fosters discussions on whether international trade is positive or not; whether food

should be produced regionally or globally. For shrimp this question is especially salient, because shrimp is con-

sidered as a luxury food product in the western world, meaning the shrimp farmers become dependent on the

economic well-being of the west. In case of a fnancial crisis and recession in Europe and other western economies,

the demand for shrimp will probably decrease, as happened in 2009.

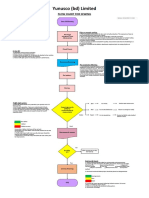

Figure 2: Worldmap of shrimp export from Bangladesh

23SAlL, 2012

24aul-Ma[umder eL al. (2000), Absar (2001)

Europe

50.07%

USA

26.80%

India

7.8%

Japan

3%

11

Can conventional shrimp farming be considered ethical or sustainable?

From a European point of view, sustainable development is still largely considered as development which meets

the needs of current generations without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs

(defnition of the Brundtland Commission 1987

25

). From this perspective, the economic, environmental and so-

cial issues aficting conventional shrimp farming may make it difcult for Europeans to call it sustainable or

ethical trade. But it is also important to couch notions of sustainability in the Bangladeshi cultural context and to

listen to the voices of the Bangladeshi conventional shrimp farmers, like that of Oshri Mridha for instance:

Oshri Mridha, 65 years old, non-organic shrimp farmer for the past 30 years.

With rice farming I could not sustain my family, but now as a shrimp famer the

income is sufcient to eat well every day and pay for the studies of my son. I still do

the hard work in the feld with the help of my son, and when the shrimp are afected

by disease it is difcult for the family to get enough food. Te vegetables in the gar-

den are growing less because of the salinity of the area and the lack of grass makes it

difcult to feed the goats. Te salt also afects the house and we need to reconstruct

the walls every year. But shrimp production is a good job and sustainable, because

in this region there is no other practical way to make an income and we are happy

now.

MD Shabtar Rahran, 40 years old, non-organic shrimp farmer and local admin-

istrator. I think that shrimp farming is good for me and Bangladesh, because the

people in this area are now economically solvent and happier than when producing

rice. Te lifestyle has improved a lot, new roads have been constructed and food

security is now a lot better than 20 years before when rice was sometimes not avail-

able on the markets. Te rice price is a little higher as we cannot produce it in this

area, but as the income is higher we can aford it. Shrimp farming has had a negative

impact on the environment; we are in a totally saline area and no rice can be grown

anymore, but there are enough rice felds in other parts of the country. With shrimp

farming we can sustain our families.

Like Oshri Mridha and Shabatar Rahran, all of the other shrimp farmers I talked to highlighted the positive f-

nancial aspects of shrimp farming. Many of them had problems sustaining their families before they engaged in

shrimp farming, even if they had rice for their own consumption. Environmental aspects were rarely mentioned,

but in the perspective of a poor farmer the most important thing is to have something to eat every day and some

kind of security that this does not change suddenly. For them sustainability means to receive a stable long-term

23 World Commlsslon on LnvlronmenL and uevelopmenL (8rundLland Commlsslon) ln lLs reporL 1987

12

income. Moreover shrimp farming has brought changes in local infrastructure, like roads, markets and more

schools to the areas, as more farmers become able to aford the costs of education.

Whose sustainability counts? Should we follow a European idea of what is ethical and sustainable, or should we

be steered by the voices of the most disadvantaged of our generation? Are future or present generations more

important? Ought we look at improving the welfare of those people living today, in Bangladesh for example, or

think rather of their childrens children. Tese questions are especially important when exploring the Bangladeshi

shrimp industry.

Creating ethical alternatives the Organic Shrimp Project

Codes of Conduct, certifcation and education in good farming practices could provide ways of making aquacul-

ture in Bangladesh more ethical and sustainable, and to bring together the diferent views on what constitutes an

ethical and sustainable industry. To explore the opportunities and barriers of ethical shrimp production, I visited

the Organic Shrimp Project (OSP) in the south-west of Bangladesh. Te OSP is a signifcant small-holder project

for organic shrimp production in the region of Satkhira in the southwest of Bangladesh. It was initiated in 2005 by

the Swiss Import Promotion Programme (SIPPO) and implemented in partnership with the local NGO Shushilan,

with the goal of promoting small and medium enterprises through providing training and consultation services,

and facilitating trade. When in 2007 the focus of SIPPO shifed towards Europe, Africa and Latin America, WAB

Trading International (Asia) Ltd took over responsibility and management of the project. Te goal of the project

is to provide a sustainable alternative to wild fshing. Now more than 1800 farmers are certifed organic as per

EU organic regulations, with this certifcation underwritten by the private German organic farmers association

Naturland, and monitored by an independent third-party body called IMO`- Institute for Market-Ecology. By

the end of 2012, 250 people were employed in the OSP.

What is Organic Shrimp Farming?

Organic Shrimp Farming is an approach to aquaculture that follows the criteria of EU and other organic regula-

tions, to minimise any adverse efects on the environment. Tis means: (i) the protection of adjacent ecosystems;

(ii) a prohibition on the use of chemicals; (iii) natural treatment in the case of disease; (iv) employing only natural

and necessary inputs; and (v) a prohibition on the use of genetically modifed organisms. It also demands an

extensive culture technique with a low stocking density (max 15 larvae/m

2

). Organic shrimp farming does not al-

low the use of any chemical inputs (such as fertiliser, pesticides or antibiotics), or wild caught PL (post larvae) for

stocking, and if feed is used it must be organic certifed as well.

In the context of Bangladesh and the OSP, no artifcial feed is used at all. Te shrimp nourish themselves on food

naturally occurring in the ponds. Te OSP supports the farmers to prepare natural compost for the regular use in

the shrimp farm to support the development of natural food. Tis allows the farmers to save on input-costs (like

chemical fertilisers) but nearly achieve the same production per hectare. In this way it increases the farmers prof-

its, while at the same time reducing the environmental impact. Moreover for this organic certifcation, 50-70% of

13

the dikes surrounding the gher must be greened with natural vegetation. To ensure traceability the farmer needs

detailed documentation about all inputs and outputs of his farm. In addition there are many more criteria regulat-

ing the organic value-chain, from larvae to the processed product.

Te Organic Shrimp Project from a supply-chain to a value-chain

Te OSP is organised with an Internal Control System (ICS), comprising of quality management procedures,

training and inspection undertaken by 47 staf members to ensure both compliance with organic regulations and

the quality of the product. One key aspect is to provide traceability. All farmers who want to join the OSP must

frst sign a contract and are registered, including an evaluation of the actual status of their farm before joining the

OSP. Every pond is registered in a GPS system together with information on its important features. Following this,

the farmer receives training on the following topics:

1. General issues of organic shrimp farming

2. Pre-stocking management; how to prepare a shrimp pond organically

3. Stocking management, and compost and Bokashi (another type of compost) preparation

4. Post-harvest and treatment management, such as how to ice the shrimp to obtain best quality

At least once a year every farmer is evaluated on a broad variety of issues and there are all sorts of quality tests.

Afer the frst approval of the farmer as organic, he receives his own OSP Identifcation Card and can sell to the

collection centres.

Box 2: Te day a mad magician came the story of Md. Abdur Rahim

Mr. Rahim is 51 years old and lives with his wife, his son and his grandson in a little house in the rural region of

Kaliganj. Life is not always easy in this region, with Mr. Rahim having lost two daughters. Afer fnishing school

20 years ago, he became a rice paddy farmer like his father. When shrimp cultivation came to the area, he also

started to grow shrimp in the low lying areas of his land, where rice farming was risky and harvests were little. At

frst shrimp farming was very proftable and his fnancial situation improved. But then diseases began to threaten

his shrimp and harvests were lower. He had to take out a loan with his father-in-law to survive, and as he could not

pay back the money, this caused some problems in the family.

One day, a man came to his feld (Mr.Aksya, the manager of the Organic Shrimp Project (OSP)). Te man told him,

that he should prepare and treat his gher in an organic way, to increase profts from his ponds. He should stop

using fertilizer and chemicals and use organic compost instead. Tis would reduce his cost of pond preparation,

reduce the risk of diseases and increase the productivity of the pond. Te other farmers laughed at this man and

called him a mad magician how can it be possible to reduce the inputs and still harvest the same or even more?

But Mr.Aksya persisted, and as Mr. Rahims situation became more hopeless, he fnally accepted to meet with

Mr.Aksya. In this meeting the organic principles and rules were explained, and Mr. Rahim decided to trust the or-

ganic way of production for one year, to see what happens. Together with Mr. Rahim only a few farmers in the area

decided to start organic shrimp farming.

Mr. Rahim and the others received basic training from the OSP to become some of the frst organic shrimp farm-

ers in Bangladesh. Tey reduced the cost of inputs and found organic alternatives, without using any chemicals.

Te result was incredible: very big shrimp. Tis convinced Mr. Rahim and he continued growing in an organic way.

Indeed, the other farmers of the area (totally 140) were also convinced by these good results and joined the OSP in

the same year.

Now, fve years later, the fnancial situation of Mr. Rahim has

changed for the better. Every year he is able to save some money

and was able to buy three more bigha of land (1 ha = 7,5bigha).

He constructed a small house with electricity, and has a TV and a

fridge. He was able to purchase a motorcycle and can aford to buy

medicine for himself and his family, and pay for the studies of his

son. Other farmers do not laugh anymore, but come and ask him

how he is cultivating the shrimp. Mr. Rahim is one example. Like

him there are many farmers who have had the same problems. A

lot of people have sold their land and house and migrated to India

or Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh, to become rickshaw-drivers.

Besides shrimp farming Mr. Rahim grows also many kinds of fruit

and vegetables, cultivated by his wife, and he still has rice paddy

felds for their own consumption.

14

Te OSP has a totally diferent and shorter value-chain to conventional shrimp production. In the organic value-

chain the harvested shrimp are put into an insulated container with ice, which sees the shrimp fall into a sleeping

state at 0-5 degrees celsius. From here the shrimp is brought

directly to a collection centre, which in some ways combines

the role of the middle-men and the depot in the convention-

al shrimp chain, under the supervision of internal inspectors.

Here, at the collection centre parts of the shrimp are removed

before they are sorted in size, weighed, iced again and the price

is documented with the farmers identifcation number. Te

price is fxed for every harvest (new/full-moon), as calculated

on the basis of the international organic shrimp price. Te

shrimp is then transported in a truck directly to the nearby

processing plant where it is processed the same day, and re-

mains continuously at -18 C. Te shrimp farmer receives their

payment within 2-3 days.

Te PL used by organic farmers are produced in an approved hatchery, clearly separated from conventional PL,

as well as controlled and certifed. Te main diference is that no chemicals or medicines are used for the organic

production; only natural inputs. Te price of the organic PL is higher because they take longer to grow. Te OSP

collection centre receives orders for the PL from the farmers in advance, then collects the PL and distributes them

to the farms, making it easier and quicker for farmers to access high quality PL, with a lower risk of disease.

At the specialised processing plant only organic shrimp is produced, to avoid mixing them with conventional

shrimp products. As it was not possible to enter a conventional processing plant, I cannot compare the quality

and working conditions, but there is some evidence that the organic processing plant I visited is of the highest

standard. To ensure high quality products, free of any traces of chemical inputs, taste and scientifc tests are car-

ried out continuously and no shipment can leave without passing these tests. Within the OSP, value is added to the

product at every step (or at least the quality is not degraded), such that it can truly be called a value-chain. Tis is

not necessarily the case for the conventional supply-chain, where a lot of the value of the shrimp is lost through

the more lengthy stages of selling, transporting and processing.

Finally, the Naturland certifcation and therefore also the OSP

are steered by broad social criteria, ranging from worker con-

tracts and working conditions, to gender justice and workers

associations. As it is culturally quite difcult at the moment to

realize some principles like gender equality or working con-

tracts in Bangladesh, the OSP tries to raise awareness on so-

cial issues like workers rights and gender issues through addi-

tional workshops and other activities. Naturland Certifcation

schemes also addresses mangrove reforestation, where shrimp

projects need to reinstate 60% of the mangrove forest that ex-

isted prior to deforestation. As the OSP in Bangladesh is situ-

ated in areas where no mangrove forest was destroyed at least

over the last 30 years, they are not afected by this regulation.

Te organic shrimp is directly shipped to Hamburg (Germany) where it arrives afer spending four to six weeks

at sea. Here it gets packed by a German packing company into the fnal packaging, designed for the diferent su-

permarkets where it will be sold, before being transported to these supermarkets. Te organic shrimp from OSP,

with added value compared to conventional shrimp, is sold to big supermarkets in the region like Aldi, Edeka

and ReWe, and additionally to some restaurants that purchase wholesale. For the moment the market is limited

to Germany, where organic food has a 3.9 % share of food sales

26

, however it is planned to soon expand to France.

Owing to economies of scale, large supermarkets were chosen as the main outlets, even though in Germany there

exist a broad range of organic food stores. In flling the large orders placed by large supermarkets, this reduces time

and resources needed to reach smaller retailers, and moreover, WAB International wants to make extensive small

holder organic shrimp available to the majority of the population, which are consumers in these supermarkets.

26 Accordlng Lo a sLudy of Lhe Cerman 8und kologische LebensmittelwirtschaIt e.V. (8CLW) (2013): 1he Crganlc Sec-

Lor 2013: llgures, uaLa, lacLs.

15

Does everyone beneft along the OSP value-chain?

Benefts for the farmers

For the farmers, the main benefts of the OSP includes the higher income due to low input costs and higher

productivity, together with the security of a continuous income, even if the price they get for the shrimp is not

necessarily as high as they could receive from the middle men on good days, (verifed in Paul, B.G. and Vogl, C.R.

(2012)). Tese advantages are captured in the voices of some of the organic shrimp farmers I spoke with:

Abdul Sattar, 32 years old, is an organic shrimp farmer. He is married and has a one-year-old daughter,

but works to support his extended family.

Before switching to organic we faced problems every month to care for the fam-

ily, which has a total of 20 members. Te fruit and vegetables around the house,

as well as the 5 bigha of land I lease for rice cultivation, are not sufcient and

it was necessary to use the profts from the shrimp farm to buy food from the

market as well. Before I used to sell the shrimp to a middleman, who did not

pay me directly and sometimes we had to wait two months for the income.

Te price I got for the shrimp also varied a lot; sometimes it was very high,

sometimes very low. In the organic system I regularly receive cash in hand and

there is no need to worry. Switching to organic production I could increase my

production, which combined with the lower input cost, allows a higher overall

income. Tis consistency ensures that my family has enough to eat every day.

and for the communities

Organic shrimp farming provides space for a new defnition of community and opportunities for better com-

munity development. Te farmers get professional support to improve their farming techniques, including the

management of water and soil quality, and through this they become more sensitive to environmental and social

issues. Some farmers reported that they did not think much about nature before they entered the OSP but that

the people are now more conscious of their natural environment. Moreover the organic farming is more labour

intensive, which is positive for the landless people who engage in work as daily labour.

Md Nurul Islam, 57 years old, is the president of one community and an

organic shrimp farmer.

Te main advantages of organic shrimp in my view can be seen in the whole

community; before the people were not solvent and engaged in illegal activi-

ties in order to have enough to eat. Tere were a lot of thieves. Now they have

enough money and they can buy food and clothing. Te poor ofen get the pos-

sibility to fsh Pangasius from the ponds.

MD Masarof Hossain, 39 years old, rice farmer

Since the Organic Shrimp Project started, the people in this region are more developed and also small scale

farmers can increase their income. I am personally not really afected by the conventional shrimp nor by

the organic shrimp, because my rice feld is in a highland area and I cannot switch to shrimp production.

but, there are those lef out.

Tose actors most negatively afected by the OSP are largely those who were engaged in the conventional value-

chain, including the middlemen working as foria, at the depots and the auctioning centre, as well as the collectors

of wild fry and those providing chemicals and medicine as inputs to conventional farms. One of the middlemen

stated that his profts have decreased since the OSP started, from 200 taka (about 2 Euro) per day to only 20-30

taka per day, and he relies on another business he runs to survive. Te OSP does provide work for 250 people in

the Internal Control System and collection centres, but they need comparatively fewer workers than the number

engaged in the conventional shrimp chain. Tis much noted, the OSP claims that jobs ofered by them represent

full-time employment and further education, which is an improvement over the less certain, casual labour in the

conventional trade. Te wild fry collectors around the large Sundarban national park, who are mainly poor and

landless people, are also likely to be negatively afected, but it must be remembered that wild fry catching is illegal

because it destroys the biodiversity of the rivers.

16

Challenges and areas for improvement

Te risk of disease

Te main negative aspect of (organic) shrimp farming mentioned by all farmers is the risk of disease. Tis risk is gen-

erally considered as lower if the quality of the PL and the water is high, and as this is normally the case in organic pro-

duction, the risk for diseases is a little lower compared to conventional production. But there are still cases of disease

which greatly afect the income of the farmers. More research on how to avoid disease outbreaks, together with train-

ing for the farmers is necessary. One possibility could be the use of probiotics (like Lactobacillus), which are benef-

cial bacteria that can increase the soil, water and feed quality. Researchers at Khulna University are investigating this.

Te collection centre

Te organic shrimp farmers were overall satisfed with their switch to organic, but noted some areas for improve-

ment in the value-chain. Tey noted that some issues arise at the collection centre during good and long harvests,

when the OSP cannot accept all the shrimp farmers bring, because the processing plant does not have sufcient

capacity to process the shrimp the same day. Tis forces farmers to sell some of their shrimp on the conventional

market, where the middlemen ofen ofer a lower price out of spite that the organic farmers no longer rely on

them. Te collection centre also limits the size of shrimp because the large shrimp are very expensive and rarely

bought on the European market, with this causing some difculties for farmers. Finally, the farmers would like

to explore the possibility of selling the other fsh species that grow in their ponds to the OSP collection centre.

Te price farmers receive for organic shrimp

Some organic farmers are dissatisfed with the price ofered for organic shrimp. Tey complain that the price they

receive for their high quality, environmentally friendly product is not necessarily higher, and sometimes even

lower than the conventional shrimp market price. However, all farmers I spoke with agreed that they will continue

selling to the collection centre, because of the good infrastructure and reliability of payments. Te question of price

is an important one, with the OSP not certifed fair trade and not (yet) fulflling the criteria for becoming fair trade

certifed. Te price at the moment is fxed every harvest according to market prices. An alternative could be a fair

bargaining of the price with the representative of each area and the project management, or a price calculation that

includes a fair trade premium. Farmers complained that the low price did not allow them to fully realise the organic

concept, which demands signifcant investment in things like dike greening. In comparison with the price the con-

sumer pay for the organic shrimp, the farmer gets approx. 25% as an income

27

. In diferent studies analysing the in-

come in comparison to the fnal selling price of other organically produced species, the same relation can be shown.

Te greening of the dikes

As the OSP is relatively new, there remain some manage-

ment problems as well as criteria that are only basically met.

For example the dike greening could still be improved, as

few farmers are really successful in growing trees or vegeta-

bles on their dikes. However, these examples show that it is

possible to promote some greenery; not only grass but also

mangrove and neem trees can be grown along the dikes, as

well as vegetables. A vegetable patch requires three years of

preparation, but they can provide an additional income as

well as food for the family. A special task is to make farmers

aware of the importance of dike greening to prevent erosion,

and that there are not any negative impacts on the shrimp.

Within the frame of a development project supported by the German government (GIZ), the OSP is working

in cooperation with Bangladesh Agricultural University to develop the most appropriate plantations for green-

ing dikes. Te greenery must be able to cope with salt water and protect the dikes. Te fruits of this research

will be passed on to the OSP farmers, but also to other communities and the government of Bangladesh. Te

aim is to stabilize not only the dikes on the farms, but also the embankments; protecting land and people from

27rlce for Crganlc Shrlmp ln a Cerman supermarkeL approx. 2 Luro per 100g, Lhe farmer geLs abouL 3 Luro (320 Laka)

per kllo, whaL means 30 CenL per 100g.

17

fooding and other natural hazards. Tis type of interaction between organizations provides spaces for further

holistic improvements to the shrimp industry in every sense: environmental, social, cultural and economic.

Maintaining organic status

A central challenge for the project is to make sure that the product can be considered as organic. As there is a canal

system providing the saline water for the aquaculture, all shrimp farms rely on the same water, and are subject to the

same contaminants

28

. Tis is why the OSP implements farm clusters. Te disadvantage is that this includes farmers

who may not be really convinced of organic principles and may be more likely to cheat, or not to comply with the

standards. To avoid this risk, the OSP has an internal control and certifcation system and farmers are punished or

excluded from the project in case of fraud. But this system demands signifcant monitoring, with high documenta-

tion and staf and resource costs, as well as the cost of independent third party certifcation. Tis makes the product

more expensive. It could be more fruitful to realize more environmental education and less control to ensure that the

farmers are convinced of the worth of organic principles, while even developing their own solutions and innovations.

Social aspects

While the Naturland certifcation does also include social crite-

ria such as gender equality and working contracts, the project

has some difculties in realising these criteria. Te main reason

is cultural. How can one convince farmers to give equal pay-

ment to female workers, when they are culturally accustomed

to paying them less? How can one persuade them to make con-

tracts with their daily workers, if they cannot read and without

money have no access to the courts? Tese issues demand a lot

of time, patience and education. Te project started by initi-

ating training to explain these important subjects to farmers,

but it will take a long time to ensure the realization of these

social criteria. Te Naturland Certifcation does have certain requirements to demonstrate an efort is being made

and advances taken as a result of the project, even accepting that these criteria cannot be changed immediately.

Creating markets for Bangladeshi organic shrimp

It is particularly challenging to sell organic shrimp in Europe, for two reasons. Firstly it is difcult to establish access

to supermarkets, as Bangladesh in general and particularly the shrimp industry, has had a bad image concerning cor-

ruption, exploitation and poor quality. Moreover, big supermarkets prefer large-scale, intensive production where

they have supply chain security. According to the director of the OSP, Erdmann Wischhusen, the German food mar-

ket is especially focused on the price and there is very little consideration for ethical values when German consum-

ers are at the checkout. Even though the organic market in Germany is signifcant in comparison to other countries

in Europe, the majority of German consumers still buy their food in non-organic supermarkets, where relatively

few organic brands are ofered and they are criticised for fulflling only the most basic organic requirements. Te

second challenge in selling Bangladeshi organic shrimp is related to convincing the consumer. With exotic shrimp

having been roundly criticised in the media in the past, it is difcult to convince consumers that organic, extensive

shrimp production can present a sustainable alternative to the monoculture rice production and the overfshed sea.

Future developments and improvements

As the demand for organic shrimp is increasing, the new delivery commitments present new challenges expanding

the number of new farmers in the project. In the following year the goal of the OSP is to increase the number of

farmers from 1 800 to 3 000. Te problem is that this will also necessitate greater coordination and bureaucracy as

well as fnancial investment for traceability and quality management, as well as the construction of the necessary

structure. In addition, the OSP is planning improvements in their communication both with the consumers and

the farmers, to increase farmers engagement and empowerment within farmer communities, and there is an idea

of developing access of farmers to bank accounts to increase their ability to save.

288eslde Lhe lnows lnLo Lhe ponds Lhe ouulows are very lmporLanL ln Lerms of dlsease Lransmlsslon, lf noL separaLed

from Lhe lnow canals.

18

Te future for Bangladeshi shrimp

Amongst the public controversy around conventional Bangladeshi shrimp are some arguments that are well justifed,

while others not well grounded or are very one-sided. Conventional shrimp production brings, on the one hand,

economic profts for the farmers and foreign currency to Bangladesh, while on the other hand there are some neg-

ative environmental and social impacts. It has to be considered that shrimp farming was internationally promoted

in the past and is an adaptation of the farmers to a changing landscape, brought on in large part by climate change

and Indias water management, such that coastal lowlands are today more suitable and proftable for shrimp aqua-

culture. In these increasingly saline lowland soils, agriculture like rice farming is at the moment not productively

possible. Terefore it can meaningfully be argued that it is irresponsible to simply cut the trade of Bangladeshi

shrimp, leaving the 1.2 million people currently engaged in the industry, and their families, without any income.

Te question should be how the cultivation of shrimp or other alternatives can be developed such that the trade

can be considered as ethical or sustainable from both Bangladeshi and European points of view. One approach

is presented by the Organic Shrimp Project, which has shown that the situation for the farmers, the environment

and the consumers can be greatly improved. As shrimp production in Bangladesh is mainly extensive, traditional

and family based, this presents a good starting point to promote more environmentally friendly and more socially

just shrimp production. Organic production potentially presents a more sustainable and ethical way forward both

in the short and long term, while also presenting a better option technically, though there is a lot of work needed

to convince the farmers to change their ways of production. Research and education will play an important role in

empowering people to judge on their own what they consider as positive for their country, their community and

their environment. Te Organic Shrimp Project is still in its early stages and may not yet do enough to be called ful-

ly sustainable, but in my point of view they should be encouraged to go one step further, together with the farmers.

Everybody needs to decide on his or her own whether it is ethical or sustainable to consume organic shrimp, tak-

ing into account a number of broad considerations. Tese range from a broader discussion on the sustainability

of global food trade, to the opportunity for farmers of a very impoverished and climate change-ravaged country

to improve their situation in the short and the long run. What makes shrimp from Bangladesh so special are the

families and stories involved in the process of producing them, so that every shrimp has its own story.

Acknowledgements: I would like to acknowledge the support of the European Commissions SEAT Project for the

funding that made this research possible, the consortium partners from the University of Bergen for facilitating

this work, and the partners from the Bangladesh Agricultural University for organizing my trip in Bangladesh

particularly Mohammed Haque and Roni. Tanks must also go to the wider consortium that contributed to this

fnal version of my narrative with their comments.

19

References:

Absar, S. S. (2001). Problems surrounding wages: the readymade garments sector in Bangladesh. Labour and Management

in Development, 2(7), 1-17.

Ahmed, Fauzia Erfan (2004): Te Rise of the Bangladesh Garment Industry: Globalization, Women Workers, and Voice. In:

NWSA Journal Vol 16, No.2, Summer 2004, pp. 34-45.

Ahmed, N., Wahab, M.A., Harakansingh Tilsted (2008): Integrated aquaculture-agriculture systems in Bangladesh: Potential

for sustainable livelihoods and nutritional security of the rural poor. Aquaculture Asia Magazine. Jan-March 2007, 15-21;

sighted in WP 5.1

Ahsan, Mainul et al. (2012): Saline Soils in Bangladesh. Soil fertility Assessment, Soil degradation, and its Impact on Agricul-

ture Program. Soil Resource Development Institute, Dhaka.

Bocquillet, Xavier and Stark, Michle (2009): Improving aquaculture practices in smallholder shrimp farming. A training

Manual. Finances by Swiss Import Promotion Program with a Cooperation of Institute for Market Ecology.

Bund kologische Lebensmittelwirtschaf e.V. (BLW) (2013): Te Organic Sector 2013: Figures, Data, Facts. http://www.

boelw.de/uploads/media/pdf/Dokumentation/Zahlen__Daten__Fakten/ZDF_2013_Endversion_01.pdf (03.04.2013)

Brouwer, Roy; Akter, Sonia; Brander, Luke and Haque, Enamul (2007): Socioeconomic Vulnerability and Adaptation to

Environmental Risk: A Case Study of Climate Change and Flooding in Bangladesh. In: Risk Analysis Vol. 27, No. 2, 2007

Carbonara, Stefano (2012): Assessing the contribution of aquatic by-catch from shrimp and prawn farming to rural liveli-

hoods in southeast Bangladesh. Master Tesis.

Datta, D.K., Roy, K., Hassan, N. (2010) Shrimp Culture: Trend, Consequences and Sustainability in the South-western Coast-

al Region of Bangladesh

DoF (2010).Annual Report. Department of Fisheries, Peoples Republic of Bangladesh, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Fisheries Resources Survey System (2007): Fisheries Statistical Yearbook of Bangladesh. Department of Fisheries, Ministry

of Fisheries and Livestock.

GATE Project and Development & Training Services (2006) A pro-poor analysis of the shrimp sector in Bangladesh. USAID

Bangladesh

Haque, M. M., Wahab, M. A., Little, D.C. and Murray F.J. (2012): Development trends and sustainability issues of four com-

mercially important farmed seafood trade in Bangladesh.

Kruijssen, Froukje, Ingrid Kelling, Hong MeeChee, Karen Jespersen and Stefano Ponte (2012): Value Chains of Selected

Aquatic Products from four Asian Countries. A review of literature and secondary data. March 2012 (draf version).

Naturland (2011) Naturland Standards for Organic Aquaculture. Naturland Association for organic Agriculture, Registered

Association. Grfelfng, Germany

Paul, B.G. and Vogl, C.R. (2012): Key Performance Characteristics of Organic Shrimp Aquaculture in Southwest Bangladesh.

In: Sustainability 2012, N 4, pp 995-1012.

Primavera, J.H. (2006) Overcoming the impacts of aquaculture on the coastal zone. Ocean & Coastal Management 49, 531-

545

Sande, P. and Simonsen, H. B. (1992) Assessing Animal Welfare: Where Does Science End and Philosophy Begin? Animal

Welfare(1)4, pp 257-267

SAFE (2012): Te plight of shrimp-processing workers of South-western Bangladesh. Te Solidarity enter and Social Activi-

ties for Environment (SAFE), Solidarity Center.Org: 1-36.

Steinberg, Kathrin (2012): Socio-economic impacts of shrimp farming in Bangladesh. M.Sc. Project Dissertation. Funded by

SEAT project.

SSNC (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=riIn4RSwYGE); revised 14.03.2013

Pictures and Layout: Loni Hensler

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Outback Training ManualDocument25 pagesOutback Training ManualAnonymous TDI8qdY100% (2)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Yunusco (BD) Limited.: Flow Chart For Raw-Materials-MqcDocument1 pageYunusco (BD) Limited.: Flow Chart For Raw-Materials-MqcMd. Nurunnabi SarkerPas encore d'évaluation

- Molding Qa Flow ChartDocument1 pageMolding Qa Flow ChartMd. Nurunnabi SarkerPas encore d'évaluation

- Yunusco (BD) Limited: Flow Chart For SewingDocument1 pageYunusco (BD) Limited: Flow Chart For SewingMd. Nurunnabi SarkerPas encore d'évaluation

- Organic and Recycle Training ManualDocument47 pagesOrganic and Recycle Training ManualMd. Nurunnabi Sarker100% (4)

- Development and Status of Freshwater Aquaculture in BangladesDocument85 pagesDevelopment and Status of Freshwater Aquaculture in BangladesMd. Nurunnabi SarkerPas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment On VitaminDocument4 pagesAssignment On VitaminMd. Nurunnabi Sarker100% (1)

- Integrated Aquaculture Practice in Bangladesh Assignment Part 2Document8 pagesIntegrated Aquaculture Practice in Bangladesh Assignment Part 2Md. Nurunnabi Sarker100% (1)

- Accounting Information SystemDocument55 pagesAccounting Information SystemMd. Nurunnabi SarkerPas encore d'évaluation

- FAO Fisheries & Aquaculture - National Aquaculture Sector Overview - BangladeshDocument13 pagesFAO Fisheries & Aquaculture - National Aquaculture Sector Overview - BangladeshMd. Nurunnabi SarkerPas encore d'évaluation

- OpecDocument12 pagesOpecMd. Nurunnabi SarkerPas encore d'évaluation

- Business PlanDocument11 pagesBusiness PlanMd. Nurunnabi SarkerPas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment On ManagementDocument5 pagesAssignment On ManagementMd. Nurunnabi SarkerPas encore d'évaluation

- Business PlanDocument11 pagesBusiness PlanMd. Nurunnabi SarkerPas encore d'évaluation

- Banking Law & PracticeDocument9 pagesBanking Law & PracticeMd. Nurunnabi SarkerPas encore d'évaluation