Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Treatment of Diabetes in Women Who Are Pregnant: Pharmacist'S Letter / Prescriber'S Letter

Transféré par

carramrod20 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

9 vues5 pagesReading for MMS course Monthly Prescriber's Letter.

Titre original

230913123qrwefefrgqergerger

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentReading for MMS course Monthly Prescriber's Letter.

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

9 vues5 pagesTreatment of Diabetes in Women Who Are Pregnant: Pharmacist'S Letter / Prescriber'S Letter

Transféré par

carramrod2Reading for MMS course Monthly Prescriber's Letter.

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 5

More. . .

Copyright 2007 by Therapeutic Research Center

Pharmacists Letter / Prescribers Letter ~ P.O. Box 8190, Stockton, CA 95208 ~ Phone: 209-472-2240 ~ Fax: 209-472-2249

www.pharmacistsletter.com ~ www.prescribersletter.com

Detail-Document #230913

This Detail-Document accompanies the related article published in

PHARMACISTS LETTER / PRESCRIBERS LETTER

September 2007 ~ Volume 23 ~ Number 230913

Treatment of Diabetes in Women Who Are Pregnant

Introduction

Diabetes during pregnancy is a challenging

condition which must be closely monitored and

carefully treated. Within the last 15 years, a

number of new agents have been approved for

the treatment of diabetes. However, the role of

these agents in pregnancy is unclear. In

addition, there is controversy regarding many

issues including how to diagnose gestational

diabetes, whether treatment is necessary, and the

risks of hyperglycemia for the mother and fetus.

1

Prevalence and Risk Factors

Diabetes in a pregnant woman can be

classified as either pregestational (diabetes

existing before the onset of pregnancy) or

gestational (diabetes which begins or is first

recognized during pregnancy and goes away

after pregnancy).

1

It is estimated that more than eight million

women in the United States have pregestational

diabetes, with the majority of these cases

considered type 2 diabetes.

2,3

However, by far,

the majority of cases of diabetes in pregnancy

are gestational. It is estimated that up to 95% of

all cases of diabetes during pregnancy are

gestational diabetes.

4

The incidence of gestational diabetes varies

considerably depending on the population being

studied. Two of the most important factors

appear to be age and ethnic origin.

1

Although

there are a variety of other risk factors for the

development of gestational diabetes, the degree

to which these factors increase the risk of

gestational diabetes is difficult to quantify.

Consequently, it is easier to define low risk

individuals. In general, a woman is considered

low risk for the development of gestational

diabetes if she meets all of the following:

1,2

less than 25 years old

not a member of a high-risk ethnic group

such as Hispanic, African American, or

Native American

body mass index of 25 or less

no previous history of abnormal glucose

tolerance or adverse neonatal outcome

commonly associated with

hyperglycemia during pregnancy

no known family history of diabetes in a

first degree relative

Pathophysiology

In general, during pregnancy, an increase in

insulin resistance and reduction in the action of

insulin is noted. During the first trimester,

however, high estrogen concentrations increase

insulin sensitivity. In combination with nausea

and vomiting, this increase in insulin sensitivity

can lead to maternal hypoglycemia. As the

pregnancy continues, placental hormones such

as progesterone, prolactin, placental growth

hormone, and others lead to an increase in

insulin resistance.

3

Diagnosis of Gestational Diabetes

Although there are a number of different

screening tests, the most information exists

using a 100 gram oral glucose load. In this test,

a 100 gram oral glucose load is given in the

morning after an overnight (eight to 14 hours)

fast. Prior to the test, there should be at least

three days of unrestricted diet and unlimited

physical activity. Two or more of the following

values must be exceeded in order to establish the

diagnosis of gestational diabetes:

5,6

fasting venous plasma concentration

95 mg/dL or higher

one hour venous plasma concentration

180 mg/dL or higher

two hour venous plasma concentration

155 mg/dL or higher

(Detail-Document #230913: Page 2 of 5)

More. . .

Copyright 2007 by Therapeutic Research Center

Pharmacists Letter / Prescribers Letter ~ P.O. Box 8190, Stockton, CA 95208 ~ Phone: 209-472-2240 ~ Fax: 209-472-2249

www.pharmacistsletter.com ~ www.prescribersletter.com

three hour venous plasma concentration

140 mg/dL or higher

Preconception Care in a Woman with

Diabetes

In a woman with pregestational diabetes,

preconception care should focus on control of

diabetes, most commonly with insulin, and

maintenance of an A1c less than 1% above the

normal A1c range.

6

Glucose goals include

fasting capillary plasma glucose of 80 to

110

mg/dL and a two-hour postprandial capillary

plasma glucose less than 155 mg/dL.

6

Treatment of Diabetes During Pregnancy

Despite the differences in the pathogenesis of

pregestational and gestational diabetes,

treatment is similar. Ultimately, the goal of

treatment is a reduction of pregnancy

complications associated with hyperglycemia

such as macrosomia (babies who are large for

their gestation age), shoulder dystocia (condition

where the shoulders of the baby are stuck during

delivery), and other birth trauma, and metabolic

effects in the neonate such as hypoglycemia,

hypocalcemia, and hyperbilirubinemia.

1,7

Tight glucose control is imperative during

pregnancy. This is best achieved by a

combination of diet, exercise and pharmacologic

therapy.

2,3

According to the American Diabetes

Association and the Canadian Diabetes

Association, all women with gestational diabetes

should receive nutritional counseling. The diet

should include adequate calories and nutrients to

meet the needs of pregnancy. In obese women,

a calorie restriction of approximately 30% can

reduce hyperglycemia and plasma triglycerides

and a restriction of carbohydrates to about 40%

of total calories can reduce maternal glucose

levels and improve maternal and fetal

outcomes.

2,8

The goals of glycemic control are lower in a

woman who is pregnant compared to a woman

who is not pregnant. In a woman prescribed diet

therapy, pharmacologic therapy for diabetes

should be considered when:

2

Fasting plasma glucose are 105 mg/dL or

greater, or

One hour postprandial plasma glucose

are 155

mg/dL or greater, or

Two hour postprandial plasma glucose

are 130

mg/dL or greater

Despite nonpharmacologic therapy, it is

estimated that approximately 30% to 40% of

women diagnosed with gestational diabetes

require pharmacologic therapy.

9

Of all of the

medications used in the treatment of diabetes,

insulin has the most data to support its use and

has been shown

to reduce fetal morbidities.

Human insulin should be used when insulin

is

prescribed and the woman should be instructed

to carefully monitor plasma glucose

concentrations at home.

2,3,5,8

No particular insulin regimen has been

shown to be more effective in a pregnant woman

who requires insulin. Consequently, a simple

regimen should be started. For example, NPH

insulin at bedtime to control fasting blood

glucose can be prescribed. It should be

remembered that insulin requirements usually

increase throughout pregnancy, especially

during weeks 28 to 32 of gestation.

1,5,8

If the

patient continues to experience elevated premeal

or postmeal hyperglycemia, regular human

insulin can be added at meals and at bedtime.

1,5

A recent guideline published by the

American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology

recommends that in women with pregestational

diabetes, the goal of therapy is to maintain

capillary glucose levels as close to normal as

possible.

In these women, the fasting glucose

should be 95 mg/dL or lower, and one-hour and

two-hour postprandial glucose concentrations

should be less than 140 mg/dL and 120 mg/dL,

respectively. An older guideline published by

the American College of Obstetrics and

Gynecology for the treatment of gestational

diabetes does not specify treatment goals in

women receiving insulin therapy.

1,2

Previously, the use of insulin analogs had not

been

adequately tested in women who are

pregnant. However, recently a number of

clinical trials evaluating some of the newer

insulins have been published.

Rapid-acting

insulin lispro (Humalog) and insulin aspart

(Novolog) are pregnancy category B and likely

as safe as regular human insulin.

10-13

No human

data exists for insulin glulisine (Apidra)

(Pregnancy Category C) and it is therefore not

yet recommended in women who are pregnant.

10

Long-acting insulin analogs insulin glargine

(Lantus) or insulin detemir (Levemir) are

(Detail-Document #230913: Page 3 of 5)

More. . .

Copyright 2007 by Therapeutic Research Center

Pharmacists Letter / Prescribers Letter ~ P.O. Box 8190, Stockton, CA 95208 ~ Phone: 209-472-2240 ~ Fax: 209-472-2249

www.pharmacistsletter.com ~ www.prescribersletter.com

typically not used in women who are pregnant.

Both of these agents are considered Pregnancy

Category C. Although preliminary studies have

demonstrated that these insulins are effective

and safe, more information is needed before

these agents can be routinely recommended.

10,14-

16

In the past, oral agents for diabetes were not

recommended

during pregnancy. Although oral

agents were studied in the 1970s and 1980s,

because of concerns about effects on the fetus,

oral agents were not recommended.

17

Early

sulfonylureas crossed the placenta and were able

to stimulate the pancreas of the fetus. In

addition, there was concern about the potential

for teratogenicity.

17

However, a number of

recent trials evaluating the use of glyburide, a

second-generation sulfonylurea which minimally

crosses the placenta, and metformin in women

who are pregnant have been published.

One of the first large, randomized, controlled

trials evaluating glyburide was published in

2000. Langer and colleagues compared

metabolic control in 404 women with gestational

diabetes who failed to achieve glycemic control

with diet and exercise treated with glyburide or

traditional insulin therapy. Overall, only eight

women

(4%) in the glyburide group did not

achieve adequate glycemic

control and those

who received glyburide had significantly less

hypoglycemia compared with those women who

received insulin. In addition, there were no

reports of neonatal hyperinsulinemia due to

transplacental passage of

the sulfonylurea drug,

and there was no difference in the incidence of

macrosomia or neonatal

hypoglycemia.

18

More recently, Jacobson and colleagues

found that after controlling for confounding

factors, in a study of more than 500 women with

gestational diabetes, women who were treated

with glyburide achieved better glycemic control

than those who received insulin. Although the

rates of macrosomia and large infants were

similar between the two treatment groups, there

was an increased rate of preeclampsia, neonatal

birth injury and the need for neonatal

phototherapy in the glyburide-treated group.

However, it is important to recognize that the

study was a retrospective review, and selection

bias of those women chosen to receive glyburide

may have occurred.

9,19

In another study, Kahn and colleagues

conducted a trial to attempt to identify patient

characteristics which could predict glyburide

treatment failure in women with gestational

diabetes. A total of 95 women were included in

the study. Of these women, 19% failed

glyburide therapy and subsequently required

insulin therapy. The authors found that

predictors of glyburide failure included older

maternal age, earlier diagnosis of gestational

diabetes, higher number of previous

pregnancies, multiparity, and higher

pretreatment fasting blood glucose. The authors

hypothesized that these factors were associated

with more advanced insulin resistance.

20,21

At this time, glyburide therapy, which is

considered Pregnancy Category C, is not

approved by the Food and Drug Administration

for the

treatment of diabetes in women who are

pregnant. Additional, randomized controlled

trials evaluating the efficacy and safety of

glyburide are needed before it can be routinely

recommended for treatment of gestational

diabetes.

Metformin (Glucophage, others) is

Pregnancy Category B meaning that although

there are no adequate and well-controlled studies

in pregnant women, in rats and rabbits no

teratogenic effects were noted at high doses.

However, because metformin crosses the

placenta, concern over its use in pregnancy

continues.

There is evidence to support the use of

metformin in women with polycystic ovary

syndrome [Evidence level B; lower quality

RCT]. In these women, metformin has been

shown to be effective in the treatment of

anovulation, thereby increasing the rate of

pregnancy.

22-24

In addition, in preliminary trials,

continued use of metformin throughout

pregnancy may reduce the rate of spontaneous

abortion, and reduce fasting insulin levels.

22-24

Although there are no well-controlled,

published clinical trials evaluating the use of

metformin in women without polycystic ovary

syndrome, many case reports suggest that it is

safe to use in women with gestational diabetes.

In these reports, metformin was shown to reduce

the rate of spontaneous abortion, with no effects

on birth weight or height, or social or motor

development up to six months of age.

22-24

(Detail-Document #230913: Page 4 of 5)

More. . .

Copyright 2007 by Therapeutic Research Center

Pharmacists Letter / Prescribers Letter ~ P.O. Box 8190, Stockton, CA 95208 ~ Phone: 209-472-2240 ~ Fax: 209-472-2249

www.pharmacistsletter.com ~ www.prescribersletter.com

In an audit by Hughes and colleagues, the

outcomes of 93 women who took metformin

during pregnancy were compared with the

outcomes in 121 pregnancies which were the

controls. A total of 32 of the women continued

metformin until delivery and 23 of these women

took metformin throughout their pregnancy.

Although the women treated with metformin

weighed more and had a higher rate of chronic

hypertension, there was no difference in the

rates of pre-eclampsia, perinatal mortality, or

neonatal morbidity between those who received

metformin and those who did not.

25

As with glyburide, although preliminary

evidence shows that metformin appears to be

effective and safe, caution should be used until

more information is available.

Conclusion

Treatment of diabetes in women who are

pregnant remains a common yet challenging

issue. Although the most clinical data is with

NPH and regular human insulin therapy, recent

information supports the efficacy and safety of

the rapid-acting insulin lispro and insulin aspart.

In addition, there is increasing evidence that the

oral agents, glyburide and metformin may be

effective and safe in women who are pregnant

and are sometimes used. Although these agents

seem to be effective and safe, insulin therapy is

still preferred.

Users of this document are cautioned to use their

own professional judgment and consult any other

necessary or appropriate sources prior to making

clinical judgments based on the content of this

document. Our editors have researched the

information with input from experts, government

agencies, and national organizations. Information

and Internet links in this article were current as of

the date of publication.

Project Leader in preparation of this Detail-

Document: Neeta Bahal OMara, Pharm.D.,

BCPS

References

1. Hollander MH, Paarlberg KM, Huisjes AJ.

Gestational diabetes: a review of the current

literature and guidelines. Obstet Gynecol Survey

2007;62:125-36.

2. American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

ACOG Practice Bulletin. Gestational diabetes.

Obstet Gynecol 2001;98:525-38.

3. American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

ACOG Practice Bulletin. Pregestational diabetes

mellitus. Obstet Gynecol 2005;105:675-85.

4. Langer O. Management of gestational diabetes:

pharmacologic treatment options and glycemic

control. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am

2006;35:53-78.

5. American Diabetes Association. Gestational

diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2004;27(Suppl

1):S88-S90.

6. American Diabetes Association. Preconception

care of women with diabetes. Diabetes Care

2004;27(Suppl 1):S76-S78.

7. Crowther CA, Hiller JE, Moss JR, et al. Effect of

treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus on

pregnancy outcomes. N Eng J Med

2005;352:2477-86.

8. Canadian Diabetes Association. Gestational

diabetes mellitus. Can J Diabetes 2003;27(Suppl

2):S99-105.

9. Durnwald C, Landon MB. Glyburide: the new

alternative for treating gestational diabetes? Am J

Obstet Gynecol 2005;193:1-2.

10. Briggs GG, Freeman RK, Yaffe, SJ. Insulin

aspart, insulin detemir, insulin glargine, insulin

glulisine updates. Briggs Update - Drugs in

Pregnancy and Lactation. 2007 Jun;20(2):11-4.

11. Mathiesen ER, Kinsley B, Amiel SA, et al.

Maternal glycemic control and hypoglycemia in

type 1 diabetic pregnancy. Diabetes Care

2007;30:771-6

12. Carr KJ, Lindow SW, Masson EA. The potential

for the use of insulin lispro in pregnancy

complicated by diabetes. J Matern Fetal

Neonatal Med 2006;19:323-9.

13. Product information for insulin aspart (Novolog).

Novo Nordisk, Inc. Princeton, NJ 08540. January

2007.

14. Price N, Bartlett C, Gillmer MD. Use of insulin

glargine during pregnancy: a case-control pilot

study. BJOG 2007;114:453-7.

15. Devlin JT, Hothersall L, Wilkis JL. Use of insulin

glargine during pregnancy in a type 1 diabetic

woman. Diabetes Care 2002;25:1095-6.

16. Graves DE, White JC, Kirk JK. The use of insulin

glargine with gestational diabetes mellitus.

Diabetes Care 2006;29:471-2. (letter)

17. Tran ND, Hunter SK, Yankowitz J. Oral

hypoglycemic agents in pregnancy. Obstet

Gynecol Surv 2004;59:456-62.

18. Langer O, Conway DL, Bekus M, Xenakis EMJ,

Gonzales O. A comparison of glyburide and

insulin in women with gestational diabetes. N

Engl J Med 2000;343;1134-8.

19. Jacobson GF, Ramos GA, Ching JY, et al.

Comparison of glyburide and insulin for the

management of gestational diabetes in a large

managed care organization. Am J Obstet

Gynecol 2005;193:118-24.

20. Kahn BF, Davies JK, Lynch AM, Reynolds RM,

Barbour LA. Predictors of glyburide failure in the

treatment of gestational diabetes. Obstet Gynecol

2006;107:1303-9.

(Detail-Document #230913: Page 5 of 5)

21. Rochon M, Rand L, Roth L, Gaddipati S.

Glyburide for the management of gestational

diabetes: risk factors predictive of failure and

associated pregnancy outcomes. Am J Obstet

Gynecol 2006;195:1090-4.

22. Lord JM, Flight IHK, Norman RJ. Metformin in

polycystic ovary syndrome: systematic review

and meta-analysis. BMJ 2003;327:951-3.

23. Hawthorne G. Metformin use and diabetic

pregnancy---has its time come? Diabet Med

2006;23:223-7.

24. Checa MA, Requena A, Salvador C, et al. Insulin-

sensitizing agents: use in pregnancy and as

therapy in polycystic ovary syndrome. Human

Repro Update 2005;11:375-90.

25. Hughes RC, Rowan JA. Pregnancy in women

with type 2 diabetes: who takes metformin and

what is the outcome? Diabet Med 2006;23:318-

22.

Levels of Evidence

In accordance with the trend towards Evidence-Based

Medicine, we are citing the LEVEL OF

EVIDENCE for the statements we publish.

Level Definition

A High-quality randomized controlled trial (RCT)

High-quality meta-analysis (quantitative

systematic review)

B Nonrandomized clinical trial

Nonquantitative systematic review

Lower quality RCT

Clinical cohort study

Case-control study

Historical control

Epidemiologic study

C Consensus

Expert opinion

D Anecdotal evidence

In vitro or animal study

Adapted from Siwek J, et al. How to write an evidence-based

clinical review article. Am Fam Physician 2002;65:251-8.

Cite this Detail-Document as follows: Treatment of diabetes in women who are pregnant. Pharmacists

Letter/Prescribers Letter 2007;23(9):230913.

Evidence and Advice You Can Trust

3120 West March Lane, P.O. Box 8190, Stockton, CA 95208 ~ TEL (209) 472-2240 ~ FAX (209) 472-2249

Copyright 2007 by Therapeutic Research Center

Subscribers to Pharmacists Letter and Prescribers Letter can get Detail-Documents, like this one, on any

topic covered in any issue by going to www.pharmacistsletter.com or www.prescribersletter.com

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Gestational Diabetes GuideDocument7 pagesGestational Diabetes GuideAndres, Peter Pol D.Pas encore d'évaluation

- Diabetes Pregestacional ACOGDocument21 pagesDiabetes Pregestacional ACOGarturoPas encore d'évaluation

- Gestational Diabetes MellitusDocument4 pagesGestational Diabetes MellitusMaykel de GuzmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Inpatient Glycemic ManagementDocument13 pagesInpatient Glycemic Managementmiss betawiPas encore d'évaluation

- Gestational DiabetesDocument34 pagesGestational DiabetesAHm'd Metwally100% (1)

- Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM) .TriceDocument47 pagesGestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM) .TricejerrydanfordfxPas encore d'évaluation

- Gestational Diabetes and Diabetes in PregnancyDocument4 pagesGestational Diabetes and Diabetes in PregnancyIbrar AliPas encore d'évaluation

- Gestational Diabetes 1Document12 pagesGestational Diabetes 1Kyla Isobel DalonosPas encore d'évaluation

- Gestational Diabetes MellitusDocument47 pagesGestational Diabetes MellitusHasan A AsFourPas encore d'évaluation

- 2023 OGClinNA Medications For Managing Preexisting and Gestational Diabetes in PregnancyDocument16 pages2023 OGClinNA Medications For Managing Preexisting and Gestational Diabetes in PregnancynataliaPas encore d'évaluation

- DM in PregnancyDocument11 pagesDM in Pregnancyميمونه عبد الرحيم مصطفىPas encore d'évaluation

- OB CH20 NotesDocument16 pagesOB CH20 NotesVeronica EscalantePas encore d'évaluation

- GDMDocument3 pagesGDMErika RubionPas encore d'évaluation

- 60-2005 - Pregestational Diabetes MellitusDocument11 pages60-2005 - Pregestational Diabetes MellitusGrupo Atlas100% (1)

- Diabetes and Pregnancy - SpencerDocument59 pagesDiabetes and Pregnancy - SpencerZH. omg sarPas encore d'évaluation

- Type1Diabetesinpregnancy: David R. Mccance,, Claire CaseyDocument15 pagesType1Diabetesinpregnancy: David R. Mccance,, Claire Caseyjose ricardo escalante perezPas encore d'évaluation

- Pa Tho Physiology of Gestational Diabetes MellitusDocument3 pagesPa Tho Physiology of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus-Aldear Franze MillaPas encore d'évaluation

- Dm InpregnancyDocument16 pagesDm Inpregnancyliathmahmood15Pas encore d'évaluation

- Gestational Diabetes MellitusDocument3 pagesGestational Diabetes MellitusJustine DumaguinPas encore d'évaluation

- GDM FOGSI Text Book FinalDocument29 pagesGDM FOGSI Text Book FinalKruthika Devaraja GowdaPas encore d'évaluation

- Definition, Detection, and DiagnosisDocument7 pagesDefinition, Detection, and Diagnosismeen91_daqtokpaqPas encore d'évaluation

- MEDICAL COMPLICATIONS OF PREGNANCY ModuleDocument12 pagesMEDICAL COMPLICATIONS OF PREGNANCY ModuleWynjoy NebresPas encore d'évaluation

- sullivan1998 ເອກະສານອ້າງອີງ ຈາກ ວິທີວິທະຍາDocument10 pagessullivan1998 ເອກະສານອ້າງອີງ ຈາກ ວິທີວິທະຍາKab Zuag HaamPas encore d'évaluation

- Diabetes in PregnancyDocument88 pagesDiabetes in PregnancyKathleenZunigaPas encore d'évaluation

- Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: New Diagnostic CriteriaDocument7 pagesGestational Diabetes Mellitus: New Diagnostic CriteriaRambuPas encore d'évaluation

- dminpregnancy-201109140122 (1)Document76 pagesdminpregnancy-201109140122 (1)EndalePas encore d'évaluation

- GDMDocument12 pagesGDMJennicaPas encore d'évaluation

- Diabetic DiatDocument15 pagesDiabetic Diatannarao80Pas encore d'évaluation

- DR Farah Deeba Nasrullah Asst Prof Dept of Obgyn Unit Ii Chk/DuhsDocument14 pagesDR Farah Deeba Nasrullah Asst Prof Dept of Obgyn Unit Ii Chk/DuhsUloko ChristopherPas encore d'évaluation

- Clecture 2Document20 pagesClecture 2zahrabokerPas encore d'évaluation

- 2010 Update On Gestational DiabetesDocument13 pages2010 Update On Gestational DiabetesAde Gustina SiahaanPas encore d'évaluation

- Diabetes in PregnencyDocument51 pagesDiabetes in PregnencyMuneeb JanPas encore d'évaluation

- Diabetes Mellitus: Dr. Aldilyn J. Sarajan 2 Year OB-GYNE ResidentDocument34 pagesDiabetes Mellitus: Dr. Aldilyn J. Sarajan 2 Year OB-GYNE ResidentDee SarajanPas encore d'évaluation

- Diagnosis and Treatment of Gestasional DiabetesDocument18 pagesDiagnosis and Treatment of Gestasional DiabetesDevi Christina Damanik (Papua medical School)Pas encore d'évaluation

- Gestational DiabetesDocument24 pagesGestational Diabeteshhpr9709Pas encore d'évaluation

- GDM PresetationDocument26 pagesGDM PresetationYondri Mandaku TasidjawaPas encore d'évaluation

- Li Ruzhi Ob&Gy Hospital, Fudan UniversityDocument40 pagesLi Ruzhi Ob&Gy Hospital, Fudan UniversityJenny A. BignayanPas encore d'évaluation

- Neonatal Hypoglycemia PaperDocument22 pagesNeonatal Hypoglycemia PaperhenryrchouinardPas encore d'évaluation

- DIABETES MELLITUS IN PREGNANCYDocument38 pagesDIABETES MELLITUS IN PREGNANCYAngela Joy AmparadoPas encore d'évaluation

- Pre Gestational ConditionsDocument17 pagesPre Gestational Conditionslarissedeleon100% (2)

- Diabetes in Pregnancy ADA 2018Document7 pagesDiabetes in Pregnancy ADA 2018Reisa Maulidya TazamiPas encore d'évaluation

- Pregnant Woman Diabeties ComplicationsDocument3 pagesPregnant Woman Diabeties ComplicationsAdvanced Research PublicationsPas encore d'évaluation

- Antepartum and Intra-Partum Insulin Management of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetic Women: Impact On Clinically Signifi..Document9 pagesAntepartum and Intra-Partum Insulin Management of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetic Women: Impact On Clinically Signifi..Anggi NoviaaPas encore d'évaluation

- Recent Advances in Management of Gestational Diabetes and Pre-EclampsiaDocument36 pagesRecent Advances in Management of Gestational Diabetes and Pre-EclampsiaSyed Zahed AliPas encore d'évaluation

- STATEMENTS ADIPS GDM Management GuidelinesDocument10 pagesSTATEMENTS ADIPS GDM Management Guidelineskitten garciaPas encore d'évaluation

- Joslin Diabetes Center and Joslin Clinic Guideline For Detection and Management of Diabetes in PregnancyDocument10 pagesJoslin Diabetes Center and Joslin Clinic Guideline For Detection and Management of Diabetes in Pregnancyyulia fatma nstPas encore d'évaluation

- Dean OfficeDocument73 pagesDean Officearief19Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Elusive Diagnosis of Gestational Diabetes: Guest EditorialDocument4 pagesThe Elusive Diagnosis of Gestational Diabetes: Guest EditorialSarly FebrianaPas encore d'évaluation

- Gestational DiabetesDocument51 pagesGestational Diabeteskhadzx100% (2)

- Diabetes Mellitus & Pregnancy by D.a.mehtaDocument31 pagesDiabetes Mellitus & Pregnancy by D.a.mehtadr.d.a.mehta11Pas encore d'évaluation

- GDM CSDocument13 pagesGDM CSADRIATICO JAROSLUVPas encore d'évaluation

- GDM PDFDocument20 pagesGDM PDFAnn Michelle TarrobagoPas encore d'évaluation

- MC1 Ch16 Test Review GuideDocument11 pagesMC1 Ch16 Test Review Guidekerit76Pas encore d'évaluation

- Buletin Farmasi 1/2014Document14 pagesBuletin Farmasi 1/2014afiq83100% (1)

- Pregestational Diabetes Mellitus Guidelines for Maternal and Fetal ComplicationsDocument11 pagesPregestational Diabetes Mellitus Guidelines for Maternal and Fetal Complicationsilyu ainun najiePas encore d'évaluation

- Gestational DiabetesDocument42 pagesGestational Diabetesjohn jumborock100% (1)

- Eat Well Live Well with Diabetes: Low-GI Recipes and TipsD'EverandEat Well Live Well with Diabetes: Low-GI Recipes and TipsPas encore d'évaluation

- Managing Your Gestational Diabetes: A Guide for You and Your Baby's Good HealthD'EverandManaging Your Gestational Diabetes: A Guide for You and Your Baby's Good HealthÉvaluation : 1 sur 5 étoiles1/5 (2)

- The Diabetes Ready Reference for Health ProfessionalsD'EverandThe Diabetes Ready Reference for Health ProfessionalsPas encore d'évaluation

- Diabetes in Pregnancy: The Complete Guide to ManagementD'EverandDiabetes in Pregnancy: The Complete Guide to ManagementLisa E. MoorePas encore d'évaluation

- Comparison of Common Meds For Diabetic Neuropathy: Pharmacist'S Letter / Prescriber'S LetterDocument5 pagesComparison of Common Meds For Diabetic Neuropathy: Pharmacist'S Letter / Prescriber'S Lettercarramrod2Pas encore d'évaluation

- 250803111111Document4 pages250803111111carramrod2Pas encore d'évaluation

- Selecting A Sulfonylurea: Pharmacist'S Letter / Prescriber'S LetterDocument3 pagesSelecting A Sulfonylurea: Pharmacist'S Letter / Prescriber'S Lettercarramrod2Pas encore d'évaluation

- 1214Document4 pages1214carramrod2Pas encore d'évaluation

- 1253Document3 pages1253carramrod2Pas encore d'évaluation

- 1215Document11 pages1215carramrod2Pas encore d'évaluation

- DfsefDocument4 pagesDfsefcarramrod2Pas encore d'évaluation

- Thiazides and Diabetes: Pharmacist'S Letter / Prescriber'S LetterDocument2 pagesThiazides and Diabetes: Pharmacist'S Letter / Prescriber'S Lettercarramrod2Pas encore d'évaluation

- Proper Disposal of Expired or Unwanted DrugsDocument9 pagesProper Disposal of Expired or Unwanted Drugscarramrod2Pas encore d'évaluation

- 205rfqergqergDocument4 pages205rfqergqergcarramrod2Pas encore d'évaluation

- Initiation and Adjustment of Insulin Regimens For Type 2 DiabetesDocument2 pagesInitiation and Adjustment of Insulin Regimens For Type 2 Diabetescarramrod2Pas encore d'évaluation

- 3807Document2 pages3807carramrod2Pas encore d'évaluation

- 1107Document5 pages1107carramrod2Pas encore d'évaluation

- Prescribing For Self or FamilyDocument15 pagesPrescribing For Self or Familycarramrod2100% (2)

- Tablet Splitting - To Split or Not To SplitDocument2 pagesTablet Splitting - To Split or Not To Splitcarramrod2Pas encore d'évaluation

- Generic Drug VariabilityDocument5 pagesGeneric Drug Variabilitycarramrod2Pas encore d'évaluation

- Management of Common Skin DiseasesDocument17 pagesManagement of Common Skin Diseasescarramrod2Pas encore d'évaluation

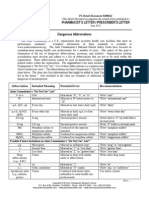

- Dangerous AbbreviationsDocument3 pagesDangerous Abbreviationscarramrod2Pas encore d'évaluation

- Unsatisfactory Progress of LabourDocument13 pagesUnsatisfactory Progress of LabourQp NizamPas encore d'évaluation

- Revista CienciaDocument126 pagesRevista CienciaMario SantayanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Sheffield Diabetes Resource PackDocument195 pagesSheffield Diabetes Resource Packhappyman1978Pas encore d'évaluation

- Gestational Diabetes MellitusDocument11 pagesGestational Diabetes Mellitusjohn jumborockPas encore d'évaluation

- Module Answers 1 60 MCN 2Document151 pagesModule Answers 1 60 MCN 2bekbekk cabahug100% (6)

- Diabetes Mellitus - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument19 pagesDiabetes Mellitus - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaAre Pee EtcPas encore d'évaluation

- (MT6317) Unit 6.1 Introduction To Carbohydrates and Glucose DeterminationDocument12 pages(MT6317) Unit 6.1 Introduction To Carbohydrates and Glucose DeterminationJC DomingoPas encore d'évaluation

- Jurnal Insulin NovorapidDocument5 pagesJurnal Insulin NovorapidSupingahPas encore d'évaluation

- Board Exams Ob Gyn 2009Document12 pagesBoard Exams Ob Gyn 2009filchibuff50% (2)

- Revision Long Case Obs GynaeDocument10 pagesRevision Long Case Obs GynaeHo Yong WaiPas encore d'évaluation

- Optimizing Postpartum CareDocument11 pagesOptimizing Postpartum Carengga.makasihPas encore d'évaluation

- Research Paper - DiabetesDocument10 pagesResearch Paper - Diabetesapi-312645878Pas encore d'évaluation

- Gestational Diabetus MellitusDocument28 pagesGestational Diabetus MellitusSanthosh.S.U100% (1)

- What Is DiabetesDocument6 pagesWhat Is DiabetesNgaire TaylorPas encore d'évaluation

- ANDIDocument455 pagesANDIandi_rao3147Pas encore d'évaluation

- A 34-Year-Ol... y at 24 Weeks GestationDocument4 pagesA 34-Year-Ol... y at 24 Weeks Gestationblndffl100% (1)

- Fdocuments - in Metabolic Disorders of Pregnancy Gestational Disorders of Pregnancy GestationalDocument42 pagesFdocuments - in Metabolic Disorders of Pregnancy Gestational Disorders of Pregnancy GestationalSoniya100% (1)

- Diabetes EbookDocument61 pagesDiabetes EbookDiabetes Care83% (6)

- QuestionsDocument16 pagesQuestionsclarPas encore d'évaluation

- Eng Ver - Guidelines For The Diagnosis and Management of Hyperglycemia in PregnancyDocument41 pagesEng Ver - Guidelines For The Diagnosis and Management of Hyperglycemia in PregnancyReza Prima M.DPas encore d'évaluation

- Pregnancy GuidelinesDocument2 pagesPregnancy Guidelinespainah sumodiharjo100% (1)

- Pcos RRL 2Document71 pagesPcos RRL 2Rosher Deliman JanoyanPas encore d'évaluation

- PPT Inggris DMDocument9 pagesPPT Inggris DMtria WidiastutiPas encore d'évaluation

- DIABETES AND PREGNANCY: MANAGING COMPLICATIONSDocument27 pagesDIABETES AND PREGNANCY: MANAGING COMPLICATIONSMartina RizkiPas encore d'évaluation

- Abella-First Level AssessmentDocument2 pagesAbella-First Level AssessmentWenalyn Grace Abella LlavanPas encore d'évaluation

- Diabetes MallitusDocument33 pagesDiabetes Mallitushammu hothi100% (2)

- Revised GDM Teaching PlanDocument4 pagesRevised GDM Teaching PlanJhon LazagaPas encore d'évaluation

- Diabetes Prediction Using Different Machine Learning Techniques PDFDocument5 pagesDiabetes Prediction Using Different Machine Learning Techniques PDFLucas Micael Gonçalves da SilvaPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Study (Diabetes Mellitus)Document24 pagesCase Study (Diabetes Mellitus)Sweetie Star88% (33)

- Obgyn Revalida Review 2022 RcsDocument248 pagesObgyn Revalida Review 2022 RcsSophia SaquilayanPas encore d'évaluation