Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Pineda v. Dela Rama case analysis under 40 characters

Transféré par

Patricia Jazmin PatricioDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Pineda v. Dela Rama case analysis under 40 characters

Transféré par

Patricia Jazmin PatricioDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

1. Pineda v.

Dela Rama

FACTS: Pineda was caught in a case against the NARIC for his alleged

misappropriation of many cavans of palay. He hired Atty. Dela Rama to

delay the filing of the complaint against him, on alleged representation of

the lawyer that he is a friend of the NARIC administrator. Pineda then issued

a promissory note in favor of dela Rama to pay for the advances that the

lawyer made to the administrator to delay the filing of the complaint. Dela

Rama on the other hand contended that the promissory note was for the

loan advanced to Pineda by him. Dela Rama filed an action against Pineda

for the collection of the amount of the note.

Issue: Whether the PN is invalid because of the fact of absence of

consideration. YES

Held: The lower courts state that a person who is a man of business would

not sign a promissory note without a consideration. However, reliance of

the lower court is based on Section 24 of NIL which states the prima facie

presumption of consideration which can be rebutted by proof to the

contrary.

The claims of dela Rama that the promissory note was for a loan advanced

to Pineda is unbelievable. The grant of a loan by a lawyer to a moneyed

client and whom he has known for only 3 months cannot be relied on.

Pineda had actually just purchased numerous properties. It is highly illogical

that he would loan from dela Rama P9500 for 5 days apart.

The consideration for the promissory note - to influence public officers in

the performance of their duties - is contrary to law and public policy. The

promissory note is void ab initio and no cause of action for the collection

cases can arise from it.

2. Phil Bank of Commerce v. Aruego

FACTS: Aruego, who is a president of Philippine Education Foundation

Company, executed 22 transactions involving trust receipts in favor of

PBCom to avail of the services of World Current Events. The proceeds of the

publication of the companys periodicals are held in trust and promise to

turnover to PBCom. The instruments are signed by Aruego, without any

indication that he is an agent of World Current Events. When he was being

held liable by PBCom, he averred that he only signed the instrument in the

capacity of agent of the company. Also, he averred that he only signed the

bill of exchange as an accommodation party or additional party obligor, to

add security.

ISSUES:

1. Whether Aruego should not be held liable because he only signed as

an agent of Philippine Education Foundation Company. No, he

should be held liable

2. Whether Aruego should not be held liable because he only signed as

an accommodation party. No, he should be held liable

HELD:

1. Section 20 of the Negotiable Instruments Law provides that "Where

the instrument contains or a person adds to his signature words

indicating that he signs for or on behalf of a principal or in a

representative capacity, he is not liable on the instrument if he was

duly authorized; but the mere addition of words describing him as

an agent or as filing a representative character, without disclosing

his principal, does not exempt him from personal liability."

An inspection of the drafts accepted by the defendant shows that

nowhere has he disclosed that he was signing as a representative of

the Philippine Education Foundation Company. For failure to

disclose his principal, Aruego should be personally liable.

2. An accommodation party is one who has signed the instrument as

maker, drawer, indorser, without receiving value therefor and for

the purpose of lending his name to some other person. Such person

is liable on the instrument to a holder for value, notwithstanding

such holder, at the time of the taking of the instrument knew him to

be only an accommodation party. In lending his name to the

accommodated party, the accommodation party is in effect a surety

for the latter. He lends his name to enable the accommodated party

to obtain credit or to raise money. He receives no part of the

consideration for the instrument but assumes liability to the other

parties thereto because he wants to accommodate another. In the

instant case, the defendant signed as a drawee/acceptor. Under the

Negotiable Instrument Law, a drawee is primarily liable. Thus, if the

defendant who is a lawyer, he should not have signed as an

acceptor/drawee. In doing so, he became primarily and personally

liable for the drafts.

3. Clark v. Sellner

FACTS: Sellner with two other persons, signed a promissory note solidarily

binding themselves to pay to the order of R.N Clark. The note matured but

the amount wasn't paid. The defendant alleges that he didn't receive any

amount of the debt; that the instrument wasn't presented to him for

payment and being an accommodation party, he is not liable unless the

note is negotiated, which wasn't done.

Issues: Should Sellner be held liable to Clark for being an accommodation

party and without proper negotiation? YES

Held: On the first issue, the liability of Sellner as one of the signers of the

note, is not dependent on whether he has or has not, received any part of

the debt. The defendant is really and expressly one of the joint and several

debtors of the note and as such he is liable under the provisions of Section

60 of the NIL.

As to the presentment for payment, such action is not necessary in order to

charge the person primarily liable, as is the defendant Sellner.

As to whether or not Sellner is an accommodation party, it should be taken

into account that by putting his signature to the note, he lent his name, not

to the creditor, but to those who signed with him placing him in the same

position and with the same liability as the said signers. It should be

notedthat the phrasewithout receiving value therefore as used in section

29 means without receiving value by virtue of the instrument and not, as

it apparently is supposed to mean, without receiving payment for lending

his name. It is immaterial as far as the creditor is concerned, whether one

of the signers has or has not received anything in payment for the use of his

name. In this case, the legal situation of Sellner is that of a joint surety who

upon the maturity of the note, pay the debt, demand the collateral security

and dispose of it to his benefit. As to the plaintiff, he is a holder for value.

4. PNB v. Maza

Facts: Maza and Macenas executed a total of five promissory notes. These

were not paid at maturity. And to recover the amounts stated on the face of

the promissory notes, PNB initiated an action against the two. The special

defense posed by the two is that the promissory notes were delivered to

them in blank by a certain Enchaus and were made to sign the notes so that

the latter could secure a loan from the bank. They also alleged that they

never negotiated the notes with the bank nor have they received any value

thereof. They also prayed that Enchaus be impleaded in the complaint but

such was denied. The trial court then held in favor of the bank.

Issue: Whether Maza and Macenas should be held liable for the 5

promissory notes. YES

Held: The defendants attested to the genuineness of the instruments sued

on. Neither did they point out any mistake in regard to the amount and

interest that the lower court sentenced them to pay. Given such, the

defendants are liable. They appear as the makers of the promissory notes

and as such, they must keep their engagement and pay as promised.

And assuming that they are accommodation parties, the defendants having

signed the instruments without receiving value thereof, for the purpose of

lending their names to some other person, are still liable for the promissory

notes. The law now is such that an accommodation party cannot claim no

benefit as such, but he is liable according to the face of his undertaking, the

same as he himself financially interest in the transaction. It is also no

defense to say that they didn't receive the value of the notes. To fasten

liability however to an accommodation maker, it is not necessary that any

consideration should move to him. The accommodation which supports the

promise of the accommodation maker is that parted with by the person

taking the note and received by the person accommodated.

5. Sadaya v. Sevilla

FACTS:

Sadaya, Sevilla and Varona signed solidarily a promissory note in favor of

the bank. Varona was the only one who received the proceeds of the note

Sadaya and Sevilla both signed as co-makers to accommodate Varona.

Thereafter, the bank collected from Sadaya. Varona failed to reimburse.

Consequently, Sevilla died and intestate estate proceedings were

established. Sadaya filed a creditors claim on his estate for the payment he

made on the note. The administrator resisted the claim on the ground that

Sevilla didn't receive any proceeds of the loan. The trial court admitted the

claim of Sadaya though tis was reversed by the CA.

ISSUE: Whether Sadaya could reimburse payment he made to the Bank with

the estate of Sevilla?

Held: Sadaya could have sought reimbursement from Varona, which is right

and just as the latter was the only one who received value for the note

executed. There is an implied contract of indemnity between Sadaya and

Varona upon the formers payment of the obligation to the bank.

Surely enough, the obligations of Varona and Sevilla to Sadaya cannot be

joint and several. For indeed, had payment been made by Varona, Varona

couldn't had reason to seek reimbursement from either Sadaya or Sevilla.

After all, the proceeds of the loan went to Varona alone.

On principle, a solidary accommodation makerwho made paymenthas

the right to contribution, from his co-accomodation maker, in the absence

of agreement to the contrary between them, subject to conditions imposed

by law. This right springs from an implied promise to share equally the

burdens thay may ensue from their having consented to stamp their

signatures on the promissory note.

The following are the rules:

1. A joint and several accommodation maker of a negotiable

promissory note may demand from the principal debtor

reimbursement for the amount that he paid to the payee

2. A joint and several accommodation maker who pays on the said

promissory note may directly demand reimbursement from his co-

accommodation maker without first directing his action against the

principal debtor provided that

a. He made the payment by virtue of a judicial demand

b. A principal debtor is insolvent.

It was never shown that there was a judicial demand on Sadaya to pay the

obligation and also, it was never proven that Varona was insolvent. Thus,

Sadaya cannot proceed against Sevilla for reimbursement.

6. Republic Bank v. Ebrada

FACTS: Ebrada encashed check issued by the Bureau of Treasury (BoT) to

Republic Bank. The bank later advised BoT that the indorsement of Martin

Lorenzo, the original payee, was a forgery since the later died before the

endorsement was made. Bank refunded BoT, and subsequently demanded

a refund from Ebrada. Ebrada refused alleging that she was a holder in due

course. Third, fourth and so-on party complaint had been filed with the

following, as indorsers,

MARTIN LORENZO RAMON R. LORENZO DELIA DOMINGUEZ

EBRADA.

Issue: Does the existence of a forged signature voids all other negotiations

of the check with respect to the other parties whose signature are genuine?

Can the drawee bank recover from the one who encashed the check?

Held: No, according to jurisprudence only the negotiation based on the

forged or unauthorized signature is inoperative. It can be safely concluded

that it is only the negotiation predicated on the forged indorsement that

should be declared inoperative. This means that the negotiation of the

check in question from Martin Lorenzo, the original payee, to Ramon R.

Lorenzo, the second indorser, should be declared of no affect, but the

negotiation of the aforesaid check from Ramon R. Lorenzo to Adelaida

Dominguez.

Yes, it was held that the drawee of a check can recover from the holder the

money paid to him on a forged instrument. It is not supposed to be its duty

to ascertain whether the signatures of the payee or indorsers are genuine or

not. This is because the indorser is supposed to warrant to the drawee that

the signatures of the payee and previous indorsers are genuine, warranty

not extending only to holders in due course. One who purchases a check or

draft is bound to satisfy himself that the paper is genuine and that by

indorsing it or presenting it for payment or putting it into circulation before

presentation he impliedly asserts that he has performed his duty and the

drawee who has paid the forged check, without actual negligence on his

part, may recover the money paid from such negligent purchasers. In such

cases the recovery is permitted because although the drawee was in a way

negligent in failing to detect the forgery, yet if the encasher of the check

had performed his duty, the forgery would in all probability, have been

detected and the fraud defeated.

In the case at bar, Ebrada upon receiving the check in question from

Adelaida Dominguez, was duty-bound to ascertain whether the check in

question was genuine before presenting it to Republic Bank.

7. United General Industries v. Paler

FACTS: Paler and his wife purchased a TV from United General Industries on

an installment basis which the former secured with PN and a CHM over the

TV. The former defaulted in the installment payments, and also due to

violation in the terms and condition of the CHM an criminal case of estafa

was filed. They settled the criminal case of Paler extra-judicially, and

executed a PN, with Dela Rama as an accommodation party, amounting to

3,083PHP plus 12% interest. And herein after, they also failed to pay the PN

after repeated demands thus the institution of the appeal of the case. Paler

and Dela Rama claim in their appeal that the complaint should have been

dismissed because "the obligation sought to be enforced by plaintiff-

appellee against defendants-appellants arose or was incurred in

consideration for the compounding of a crime."

ISSUE: Whether the PN is void to Paler and Dela Rama by the fact that its

consideration is against public policy? To Paler NO, To Dela Rama YES

HELD: Under the law and jurisprudence, there can be no recovery against

Jose de la Rama who incidentally appears to have been an accommodation

signer only of the promissory note which is vitiated by the illegality of the

cause. But it is different with Jose Paler who bought a television set from

the appellee, did not pay for it and even sold the set without the written

consent of the mortgagee which accordingly brought about the filing of the

estafa case. He has an obligation to the appellee independently of the

promissory note which was co-signed by Jose de la Rama. For Paler to

escape payment of a just obligation will result in an untrust enrichment at

the expense of another. This we cannot in conscience allow.

8. Prudencio v. CA

Doctrine: Notwithstanding that an accommodation party is primarily liable

to a holder for value of NI, if by the acts of the payee the accommodation

party is prejudiced, the holder for value is subject to personal defenses

available to the accommodation party.

FACTS: Prudencio obtained a loan with PNB and secured it with their own

land. They issued a corresponding PN as regards to the loan, which was

signed by Jose Torribio, an attorney-in-fact by the company, and Prudencio.

Such transaction was in consideration of the construction contract of the

principal debtor, Concepcion and Tamayo Construction Company. However,

the 3rd installment releasing of loan as regards the funding of the labor and

materials was not released because of the fact that the loan was already

overdue. The construction contract was rescinded between the Company

and the Bureau of Public Works. As a consequence, the Company

abandoned the work. Prudencio herein now is requesting to cancel the

mortgage in consideration of the loan because the release of funds of the

PN was with the Company and not with them. This is because of the

changes of the terms and conditions of the surrounding contract as the

Deed of Assignments release of payments of Bureau to apply to the loan.

PNB refused. The petitioners were ordered to pay jointly and severally with

their co-makers Ramon C. Concepcion and Manuel M. Tamayo the sum of

P11,900.19 with interest at the rate of 6% per annum from the date of the

filing of the complaint on June 27, 1959 until fully paid and Pl,000.00

attorney's fees. They defaulted. The mortgaged properties were sold in a

public auction and, thus, the institution of this case.

Issue: Whether the disposition of their mortgaged property is proper being

that they are only accommodation party therefore should not be included in

the new contract supporting the accessory contract (mortgage contract). No

it is not proper.

Held: The petitioners contend that as accommodation makers, the nature of

their liability is only that of mere sureties instead of solidary co-debtors such

that "a material alteration in the principal contract, effected by the creditor

without the knowledge and consent of the sureties, completely discharges

the sureties from all liability on the contract of suretyship. " They state that

when respondent PNB did not apply the initial and subsequent payments to

the petitioners' debt as provided for in the deed of assignment, they were

released from their obligation as sureties and, therefore, the real estate

mortgage executed by them should have been cancelled.

Section 29 of the Negotiable Instrument Law provides:

Liability of accommodation party. An accommodation party is one who

has signed the instrument as maker, drawer, acceptor, or indorser, without

receiving value therefor, and for the purpose of lending his name to some

other person. Such a person is liable on the instrument to a holder for value,

notwithstanding such holder at the time of taking the instrument knew him

to be only an accommodation party.

Unlike in a contract of suretyship, the liability of the accommodation party

remains not only primary but also unconditional to a holder for value such

that even if the accommodated party receives an extension of the period for

payment without the consent of the accommodation party, the latter is still

liable for the whole obligation and such extension does not release him

because as far as a holder for value is concerned, he is a solidary co- debtor.

There is, therefore, no question that as accommodation makers, petitioners

would be primarily and unconditionally liable on the promissory note to a

holder for value, regardless of whether they stand as sureties or solidary co-

debtors since such distinction would be entirely immaterial and

inconsequential as far as a holder for value is concerned. Consequently, the

petitioners cannot claim to have been released from their obligation simply

because the time of payment of such obligation was temporarily deferred

by PNB without their knowledge and consent. There has to be another basis

for their claim of having been freed from their obligation. The question

which should be resolved in this instant petition, therefore, is whether or

not PNB can be considered a holder for value under Section 29 of the

Negotiable Instruments Law such that the petitioners must be necessarily

barred from setting up the defense of want of consideration or some other

personal defenses which may be set up against a party who is not a holder

in due course.

A holder for value under Section 29 of the Negotiable Instruments Law is

one who must meet all the requirements of a holder in due course under

Section 52 of the same law except notice of want of consideration.

As to the question if PNB here is a holder in due course, Bureau's release of

three payments directly to the Company instead of paying the same to the

Bank. This approval was in violation of the Deed of Assignment and without

any notice to the petitioners who stood to lose their property once the

promissory note falls due without the same having been paid because the

PNB, in effect, waived payments of the first three releases. From the

foregoing circumstances, PNB can not be regarded as having acted in good

faith which is also one of the requisites of a holder in due course under

Section 52 of the Negotiable Instruments Law. The PNB knew that the

promissory note which it took from the accommodation makers was signed

by the latter because of full reliance on the Deed of Assignment, which, PNB

had no intention to comply with strictly. Worse, the third payment to the

Company in the amount of P4,293.60 was approved by PNB although the

promissory note was almost a month overdue, an act which is clearly

detrimental to the petitioners. Therefore, PNB is not a holder in due course

and subject to the personal defenses such as this.

9. Crisologo-Jose v. CA

DOCTRINE: Signatories of purported agents over a NI without proper

authorities renders them personally liable.

FACTS: Santos, VP of Mover Enterprises in-charge of marketing and sales,

and Benares is the president. Atty. Benares issued check amounting to

45,000 in accommodation to his clients, Jaime and Clarita Ong. Such check

was payable to Ernestina Crisologo-Jose and under the name of Mover

Enterprises. As it is a company check it must be signed by both president

and treasurer, however, the treasurer at that time was not available, VP

Santos signed in behalf of the treasurer as alternate. Consideration of the

check is the waiver or quitclaim by Crisologo-Jose which GSIS sold to Jaime

and Clarita Ong, with the understanding that upon approval by the GSIS of

the compromise agreement with the spouses Ong, the check will be

encashed accordingly. Since the compromise agreement was not yet

completed at the time, Atty Benares and VP Santos replaced the check with

the same amount. When Crisologo-Jose deposited the check, it was

dishonored by the bank because of insufficiency of funds. Therefore,

Crisologo-Jose instituted BP 22.

ISSUE: Whether the accommodation party in this case is Mover Enterprises,

Inc. and not private respondent who merely signed the check in question in

a representative capacity, that is, as vice-president of said corporation,

hence he is not liable thereon under the Negotiable Instruments Law.

NO, MOVER ENTERPRISE NOT HELD LIABLE, Atty. Benares and VP Santos

is.

HELD: To be considered an accommodation party, a person must (1) be a

party to the instrument, signing as maker, drawer, acceptor, or indorser, (2)

not receive value therefor, and (3) sign for the purpose of lending his name

for the credit of some other person. Based on the foregoing requisites, it is

not a valid defense that the accommodation party did not receive any

valuable consideration when he executed the instrument. From the

standpoint of contract law, he differs from the ordinary concept of a debtor

therein in the sense that he has not received any valuable consideration for

the instrument he signs. Nevertheless, he is liable to a holder for value as if

the contract was not for accommodation in whatever capacity such

accommodation party signed the instrument, whether primarily or

secondarily. Thus, it has been held that in lending his name to the

accommodated party, the accommodation party is in effect a surety for the

latter.

An accommodation party liable on the instrument to a holder for value,

although such holder at the time of taking the instrument knew him to be

only an accommodation party, does not include nor apply to corporations

which are accommodation parties. This is because the issue or indorsement

of negotiable paper by a corporation without consideration and for the

accommodation of another is ultra vires. Hence, one who has taken the

instrument with knowledge of the accommodation nature thereof cannot

recover against a corporation where it is only an accommodation party. If

the form of the instrument, or the nature of the transaction, is such as to

charge the indorsee with knowledge that the issue or indorsement of the

instrument by the corporation is for the accommodation of another, he

cannot recover against the corporation thereon. 9

By way of exception, an officer or agent of a corporation shall have the

power to execute or indorse a negotiable paper in the name of the

corporation for the accommodation of a third person only if specifically

authorized to do so. Corollarily, corporate officers, such as the president

and vice-president, have no power to execute for mere accommodation a

negotiable instrument of the corporation for their individual debts or

transactions arising from or in relation to matters in which the corporation

has no legitimate concern. Since such accommodation paper cannot thus be

enforced against the corporation, especially since it is not involved in any

aspect of the corporate business or operations, the inescapable conclusion

in law and in logic is that the signatories thereof shall be personally liable

therefor, as well as the consequences arising from their acts in connection

therewith.

10. Travel-on v. CA

FACTS: Petitioner Travel-on was a travel agency involved in ticket sales on a

commission basis for and on behalf of different airline companies. Miranda

has a revolving credit line with the company. He procured tickets on behalf

of others and derived commissions from it. Petitioner filed a collection suit

against Miranda for the unpaid amount of six checks. Petitioner alleged that

Miranda procured tickets from them which he paid with cash and checks

but the checks were dishonored upon presentment to the bank. This was

being refuted by Miranda by saying that he actually paid for his obligations,

even in the excess. He argued that the checks were for accommodation

purposes only of the General Manager. The General Manager needed to

show to its Board of Directors that its accounts receivable was in good

standing. The RTC and CA held Miranda not to be liable.

ISSUE: Whether Miranda should be held liable for the 6 checks.

HELD: Reliance by the lower and appellate court on the companys financial

statements were wrong, to see if Miranda was liable or not. These financial

statements were actually not updated to show that there was indebtedness

on the part of Miranda. The best evidence that the courts should have

looked at were the checks itself. There is a prima facie presumption that a

check was issued for valuable consideration and the provision puts the

burden upon the drawer to disprove this presumption. Miranda was unable

to relieve himself of this burden.

Only clear and convincing evidence and not mere self-serving evidence of

drawer can rebut this presumption. The company was entitled to the

benefit conferred by the statutory provision. Miranda failed to show that

the checks werent issued for any valuable consideration. The checks were

clear by stating that the company was the payee and not a mere

accommodated party. And also, notice was given to the fact that the checks

were issued after a written demand by the company regarding Mirandas

unpaid liabilities.

11. Town Savings and Loan Bank (TSLB) v. CA

FACTS: The Hipolitos was granted a loan amounting to 700K from TSLB. A

PN was issued with a maturity period of three (3) years and an acceleration

clause upon default in the payment of any amortization, plus a penalty of

36% and 10% attorney's fees, if the note were referred to an attorney for

collection. Hipolitos defaulted. The loan was allegedly for the account of

Pilarita H. Reyes, the Sister of Miguel Hipolito, making the Hipolitos mere

guarantors. They did so because of persuasion of the President of TSLB.

When they received the demand letters, they confronted him but they were

told that the Bank had to observe the formality of sending notices and

demand letters. The real purpose was only to pressure Pilarita to comply

with her undertaking. The trial court held that they were liable as

accommodation parties to the promissory note. This was reversed by the

Court of Appeals.

ISSUE: Whether the Hipolitos are liable on the promissory note which they

executed in favor of the petitioner. YES HIPOLITOS ARE LIABLE HAHA!

HELD: An accommodation party is one who has signed the instrument as

maker, drawer, indorser, without receiving value therefore and for the

purpose of lending his name to some other person. Such person is liable on

the instrument to a holder for value, notwithstanding such holder, at the

time of the taking of the instrument knew him to be an accommodation

party. In lending his name to the accommodated party, the accommodation

party is in effect a surety for the latter. He lends his name to enable the

accommodated party to obtain credit or to raise money. He receives no part

of the consideration for the instrument but assumes liability to the other

parties thereto because he wants to accommodate another. In the case at

bar, it is indisputable that the spouses signed the promissory note to enable

Reyes to secure a loan from the bank. She was the actual beneficiary of the

loan and the spouses accommodated her by signing the note.

12. Claude Bautista v. Auto Plus Traders

FACTS: Claude Bautista, President of Cruiser Bus Lines and Transport

Corporation, purchased spare parts from Auto Plus Traders and issued two

post-dated checks for it. The checks were subsequently dishonored. Thus

the institution of BP 22 by Auto Plus Traders. Demurrer of evidence was

granted because of reasonable doubt upon the guilt of the accused however

Cruiser Bus Lines and Transport Corporation is directed to pay, THROUGH

THE BAUTISTA, of the amount of the 2 issued checks.

ISSUE: Whether Bautista, as an officer of the corporation, is personally and

civilly liable to the private respondent for the value of the two checks.

Deemed an accommodation party to the check of the firm, deemed not an

accommodation party as to the personal check he issued absent the 3

rd

element which is he must sign for the purpose of lending his name or

credit to some other person.

HELD: Under Section 29 of the Negotiable Instruments Law, an

accommodation party is liable on the instrument to a holder for value.

Private respondent adds that petitioner should also be liable for the value of

the corporation check because instituting another civil action against the

corporation would result in multiplicity of suits and delay. Of the two

checks, one was found to that of the corporation and the other one that of a

personal check of Bautista. To be an accommodation party: (1) he must be

a party to the instrument, signing as maker, drawer, acceptor, or indorser;

(2) he must not receive value therefor; and (3) he must sign for the purpose

of lending his name or credit to some other person. Therefore, Bautista is

deemed not an accommodation party as to the personal check he issued

absent the 3rd element; Cruiser Bus Lines and Transport Corporation,

however, remains liable for the checks especially since there is no evidence

that the debts covered by the subject checks have been paid.

13. Eusebio Gonzales v. PCIB

FACTS: Gonzales obtained a credit-on-hand loan agreement (COHLA) serving

his deposits as his collateral. Gonzales drew from the line thru issuance of a

check thru FCD account. Subsequently Gonzales and his wife, with the

Panlilios obtained 3 loans totaling amount of 1.8 million with a REM.

Panlilios obtained the proceeds of the loan. Panlilios interest dues were

made payment thru automatic debit of their account in PCIB, however, they

defaulted on July 1998 because they did not maintained enough deposits.

Meanwhile, Gonzales issued another check in favor of Unson drawn against

COHLA, however, upon presentment of Unson it was dishonored by PCIB

because of withdrawal of the line, unpaid periodic interest dues.

Consequently, PCIB froze the FCD account. Gonzales had a falling out with

Unson due to the dishonor of the check. Gonzales demanded PCIB to credit

back its account as it is sufficient. PCIB refused, thus this case.

ISSUE: Whether Gonzales is solidarily liable with the 1.8M YES

HELD: First, Gonzales admitted that he is an accommodation party which

PCIB did not dispute. In his testimony, Gonzales admitted that he merely

accommodated the spouses Panlilio at the suggestion of Ocampo, who was

then handling his accounts, in order to facilitate the fast release of the loan.

The first note for PhP 500,000 was signed by Gonzales and his wife as

borrowers, while the two subsequent notes showed the spouses Panlilio

sign as borrowers with Gonzales. It is, thus, evident that Gonzales signed, as

borrower, the promissory notes covering the PhP 1,800,000 loan despite

not receiving any of the proceeds. Therefore, as an accommodation party,

Gonzales is solidarily liable with the spouses Panlilio for the loans. 2.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Accounting concepts and journal entriesDocument5 pagesAccounting concepts and journal entriesvarun02208438% (8)

- Motions, Affidavits, Answers, and Commercial Liens - The Book of Effective Sample DocumentsD'EverandMotions, Affidavits, Answers, and Commercial Liens - The Book of Effective Sample DocumentsÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (13)

- The 5 Elements of the Highly Effective Debt Collector: How to Become a Top Performing Debt Collector in Less Than 30 Days!!! the Powerful Training System for Developing Efficient, Effective & Top Performing Debt CollectorsD'EverandThe 5 Elements of the Highly Effective Debt Collector: How to Become a Top Performing Debt Collector in Less Than 30 Days!!! the Powerful Training System for Developing Efficient, Effective & Top Performing Debt CollectorsÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- Walmart's $16 Billion Acquisition of FlipkartDocument2 pagesWalmart's $16 Billion Acquisition of FlipkartAmit Dharak100% (1)

- Negotiable Law Doctrines (Sundiang)Document25 pagesNegotiable Law Doctrines (Sundiang)KarellMarieLascano100% (2)

- Kauffman Vs PNBDocument3 pagesKauffman Vs PNBNoeh Ella de ChavezPas encore d'évaluation

- Junio Vs Atty GrupoDocument2 pagesJunio Vs Atty GrupoCookie CharmPas encore d'évaluation

- Philippine promissory note cases analyzedDocument13 pagesPhilippine promissory note cases analyzedRufino Gerard MorenoPas encore d'évaluation

- Negotiable Instruments Cases (Atty. Francis Ampil)Document105 pagesNegotiable Instruments Cases (Atty. Francis Ampil)Kyle Torres ViolaPas encore d'évaluation

- Nego Week 3 Case DigestDocument53 pagesNego Week 3 Case DigestKarlo Marco Cleto100% (1)

- December 16, 1914 Lessons Applicable: Consideration and Party (Negotiable Instruments) FactsDocument6 pagesDecember 16, 1914 Lessons Applicable: Consideration and Party (Negotiable Instruments) FactsJasfher CallejoPas encore d'évaluation

- Nego 9Document1 pageNego 9Shally Lao-unPas encore d'évaluation

- Negotiable Instruments Law Accommodation PartyDocument5 pagesNegotiable Instruments Law Accommodation PartyDarlene GanubPas encore d'évaluation

- Nego Case Digests June 10, 2013 Pineda V. Dela RamaDocument6 pagesNego Case Digests June 10, 2013 Pineda V. Dela RamaChic PabalanPas encore d'évaluation

- Guaranty & Suretyship - CasesDocument361 pagesGuaranty & Suretyship - CasesClarice Joy Sj100% (1)

- Negotiable Law DoctrinesDocument22 pagesNegotiable Law DoctrineswichupinunoPas encore d'évaluation

- Sadaya v. Sevilla case on accommodation partiesDocument16 pagesSadaya v. Sevilla case on accommodation partiesAdrian HilarioPas encore d'évaluation

- PNB v. Maza and MecenasDocument1 pagePNB v. Maza and MecenasEdwin VillaPas encore d'évaluation

- Digest 3Document24 pagesDigest 3Kathlene JaoPas encore d'évaluation

- CRISOLOGO JOSE V. CA - Accommodation Party 177 SCRA 594 Facts: Gempesaw V. Ca 218 SCRA 682 FactsDocument7 pagesCRISOLOGO JOSE V. CA - Accommodation Party 177 SCRA 594 Facts: Gempesaw V. Ca 218 SCRA 682 FactsSheila May Panganiban LumardaPas encore d'évaluation

- Palmares V. Court of AppealsDocument12 pagesPalmares V. Court of AppealsayasuePas encore d'évaluation

- Negotiable Instruments Case DigestDocument5 pagesNegotiable Instruments Case DigestCazzandhra BullecerPas encore d'évaluation

- "Quickie" Philippine Bank of Commerce V. AruegoDocument15 pages"Quickie" Philippine Bank of Commerce V. AruegoRhaegar TargaryenPas encore d'évaluation

- Crisologo Vs CADocument19 pagesCrisologo Vs CALance RonquiloPas encore d'évaluation

- Nature of liability and indorser obligationsDocument5 pagesNature of liability and indorser obligationsjobelle barcellanoPas encore d'évaluation

- Travel-On Vs CADocument4 pagesTravel-On Vs CAjoshstrike21Pas encore d'évaluation

- 05 Palmares Vs CA PDFDocument21 pages05 Palmares Vs CA PDFEliePas encore d'évaluation

- 124731-1998-Palmares v. Court of AppealsDocument18 pages124731-1998-Palmares v. Court of Appealsaspiringlawyer1234Pas encore d'évaluation

- Obligations and Contracts CasesDocument9 pagesObligations and Contracts CaseslazylawstudentPas encore d'évaluation

- Dev't Bank of Rizal Vs Sima WeiDocument7 pagesDev't Bank of Rizal Vs Sima WeiAlpheus Shem ROJASPas encore d'évaluation

- BANK LIABLE FOR UNAUTHORIZED WITHDRAWALSDocument6 pagesBANK LIABLE FOR UNAUTHORIZED WITHDRAWALSChaPas encore d'évaluation

- Credit Transactions Case Assignment No. 3 Guaranty/SuretyshipDocument39 pagesCredit Transactions Case Assignment No. 3 Guaranty/SuretyshipMAASIN CPSPas encore d'évaluation

- Promissory Notes and Negotiable Instruments CasesDocument3 pagesPromissory Notes and Negotiable Instruments CasesMica DGPas encore d'évaluation

- Guaranty DigestDocument11 pagesGuaranty DigestArgel Joseph CosmePas encore d'évaluation

- Ang vs. Associated BankDocument3 pagesAng vs. Associated Bankmichi barrancoPas encore d'évaluation

- Manila Banking vs Teodoro Assignment as CollateralDocument2 pagesManila Banking vs Teodoro Assignment as CollateralSoltan Michael AlisanPas encore d'évaluation

- Parties Liable on Negotiable InstrumentsDocument21 pagesParties Liable on Negotiable InstrumentsElyn ApiadoPas encore d'évaluation

- Pledge Credit Transactions DigestDocument3 pagesPledge Credit Transactions DigestMasterboleroPas encore d'évaluation

- State Investment House Inc. vs. CADocument18 pagesState Investment House Inc. vs. CAJeremy MorenoPas encore d'évaluation

- R. N. Clark vs George C. Sellner - Negotiable Instruments Law and Liability of Accommodation MakerDocument3 pagesR. N. Clark vs George C. Sellner - Negotiable Instruments Law and Liability of Accommodation MakercitizenPas encore d'évaluation

- Compiled Digests Credit TransactionsDocument54 pagesCompiled Digests Credit TransactionsReuel RealinPas encore d'évaluation

- Nego Bar Exam QuestionsDocument4 pagesNego Bar Exam QuestionsKuhe DSPas encore d'évaluation

- Midterms Case Doctrines NegoDocument6 pagesMidterms Case Doctrines NegoAlex Viray LucinarioPas encore d'évaluation

- 25 Siga-An Vs VillanuevaDocument2 pages25 Siga-An Vs VillanuevaJanno Sangalang100% (1)

- 1921-Clark v. SellnerDocument3 pages1921-Clark v. SellnerKathleen MartinPas encore d'évaluation

- Negotiable Instruments Law Question and AnswerDocument7 pagesNegotiable Instruments Law Question and AnswerCyrusPas encore d'évaluation

- YbanezDocument4 pagesYbanezAlicia Jane NavarroPas encore d'évaluation

- Negotiable Instruments Law Case Digests A. RamosDocument3 pagesNegotiable Instruments Law Case Digests A. RamosLope Nam-iPas encore d'évaluation

- 121 Garcia vs. LlamasDocument2 pages121 Garcia vs. LlamasKaren Faith MallariPas encore d'évaluation

- Yang V. Court of Appeals: FactsDocument13 pagesYang V. Court of Appeals: Factsarhe gaudelPas encore d'évaluation

- D9 - Agro Conglomerates, Inc. - ZamudioDocument1 pageD9 - Agro Conglomerates, Inc. - ZamudioDis CatPas encore d'évaluation

- Philippine Bank vs Heirs Clarifies Scope of Dragnet ClauseDocument7 pagesPhilippine Bank vs Heirs Clarifies Scope of Dragnet ClauseMikkolet100% (1)

- EDITED Agency Case Digests - March 25, 2021Document5 pagesEDITED Agency Case Digests - March 25, 2021Moon MoonPas encore d'évaluation

- State Investment v. CA: Holder in Due Course StatusDocument13 pagesState Investment v. CA: Holder in Due Course StatusMike Zaccahry MilcaPas encore d'évaluation

- Module 2 (A)Document15 pagesModule 2 (A)Shubham JainPas encore d'évaluation

- Negotiable Instruments Law DoctrinesDocument21 pagesNegotiable Instruments Law DoctrinesMarc Daniel MolinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Rivera, Andrei Nicole MDocument7 pagesRivera, Andrei Nicole MAndrei Nicole Mendoza RiveraPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Digest CreditDocument9 pagesCase Digest CreditCrestu JinPas encore d'évaluation

- Negotiable Instrument CasesDocument9 pagesNegotiable Instrument CasesQuinnee VallejosPas encore d'évaluation

- Ang Tek Lian V. Ca 87 Phil 383Document10 pagesAng Tek Lian V. Ca 87 Phil 383Eliza Klein GonzalesPas encore d'évaluation

- UERM Memorial Medical Center Resident Doctors' Union Vs Laguesma DigestDocument1 pageUERM Memorial Medical Center Resident Doctors' Union Vs Laguesma DigestEl G. Se ChengPas encore d'évaluation

- NIL Digests 6.6.2014Document3 pagesNIL Digests 6.6.2014Patricia Jazmin PatricioPas encore d'évaluation

- Ymbong V Abs-CbnDocument2 pagesYmbong V Abs-CbnPatricia Jazmin PatricioPas encore d'évaluation

- Raul Sembreno v. CA, Delta CorporationDocument1 pageRaul Sembreno v. CA, Delta CorporationPatricia Jazmin PatricioPas encore d'évaluation

- CORP Lim Tong LimDocument22 pagesCORP Lim Tong LimPatricia Jazmin PatricioPas encore d'évaluation

- Patriciopd - Nil Atty AmpilDocument7 pagesPatriciopd - Nil Atty AmpilPatricia Jazmin PatricioPas encore d'évaluation

- Chan Wan V Tan Kim and Chen SoDocument2 pagesChan Wan V Tan Kim and Chen SoPatricia Jazmin Patricio100% (2)

- LIKHA-PMPB v. Burlingame CorporationDocument2 pagesLIKHA-PMPB v. Burlingame CorporationPatricia Jazmin PatricioPas encore d'évaluation

- Aliviado V P&GDocument3 pagesAliviado V P&GPatricia Jazmin PatricioPas encore d'évaluation

- PNB v. Picornell Facts: Picornell Bought Bales of Tobacco From PNB For AnDocument6 pagesPNB v. Picornell Facts: Picornell Bought Bales of Tobacco From PNB For AnPatricia Jazmin PatricioPas encore d'évaluation

- Spec Pro DigestsDocument2 pagesSpec Pro DigestsPatricia Jazmin PatricioPas encore d'évaluation

- Ra 10354Document13 pagesRa 10354CBCP for LifePas encore d'évaluation

- NIL Digests 6.13.2014Document5 pagesNIL Digests 6.13.2014Patricia Jazmin PatricioPas encore d'évaluation

- Legal Profession - Finals 2Document6 pagesLegal Profession - Finals 2Patricia Jazmin PatricioPas encore d'évaluation

- Legal Profession - FinalsDocument29 pagesLegal Profession - FinalsPatricia Jazmin PatricioPas encore d'évaluation

- Legal Profession - Finals 3Document11 pagesLegal Profession - Finals 3Patricia Jazmin PatricioPas encore d'évaluation

- Huhn - Syllogistic Reasoning in Briefing Cases PDFDocument51 pagesHuhn - Syllogistic Reasoning in Briefing Cases PDFpoppo1960Pas encore d'évaluation

- 2013 ATP&JV Outline PDFDocument68 pages2013 ATP&JV Outline PDFPatricia Jazmin PatricioPas encore d'évaluation

- Huhn - Deductive Logic in Legal ReasoningDocument50 pagesHuhn - Deductive Logic in Legal ReasoningPatricia Jazmin PatricioPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction to Legal LogicDocument54 pagesIntroduction to Legal LogicPatricia Jazmin PatricioPas encore d'évaluation

- Dissolution QuizDocument2 pagesDissolution QuizveriPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Study of The Moldovan Bank FraudDocument20 pagesCase Study of The Moldovan Bank FraudMomina TariqPas encore d'évaluation

- Engineering Economic Analysis 11th Edition EbookDocument61 pagesEngineering Economic Analysis 11th Edition Ebookdebra.glisson665100% (48)

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument13 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Financial Markets and Institutions PowerPoint SlidesDocument24 pagesFinancial Markets and Institutions PowerPoint Slideshappy aminPas encore d'évaluation

- MMM Made SimpleDocument30 pagesMMM Made Simplecrazy fudgerPas encore d'évaluation

- Corporate Liquidation CaseDocument1 pageCorporate Liquidation CaseASGarcia24Pas encore d'évaluation

- Impact of Fundamentals on IPO ValuationDocument21 pagesImpact of Fundamentals on IPO ValuationManish ParmarPas encore d'évaluation

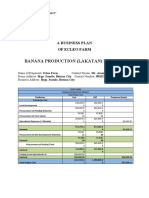

- Banana Production (Lakatan) Project: A Business Plan of Ecleo FarmDocument20 pagesBanana Production (Lakatan) Project: A Business Plan of Ecleo Farmmarkgil1990Pas encore d'évaluation

- Mathematical Modeling and Computation in FinanceDocument4 pagesMathematical Modeling and Computation in FinanceĐạo Ninh ViệtPas encore d'évaluation

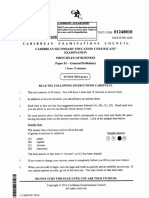

- CSEC POB June 2016 P1 With AnswersDocument8 pagesCSEC POB June 2016 P1 With AnswersJAVY BUSINESSPas encore d'évaluation

- SGC Composition and FunctionsDocument2 pagesSGC Composition and FunctionsDecember Cool100% (5)

- Section 2. Original Certificates of Title Shall Be Reconstituted From Such of TheDocument2 pagesSection 2. Original Certificates of Title Shall Be Reconstituted From Such of TheAlexylle ConcepcionPas encore d'évaluation

- INFINITI RETAIL LIMITED (Trading As Cromā) : Tax InvoiceDocument3 pagesINFINITI RETAIL LIMITED (Trading As Cromā) : Tax Invoice2018hw70285Pas encore d'évaluation

- Gift Case InvestigationsDocument17 pagesGift Case InvestigationsFaheemAhmadPas encore d'évaluation

- SERPDocument2 pagesSERPBill BlackPas encore d'évaluation

- ICT Forex - The Weekly Bias - Excellence in Short Term TradingDocument8 pagesICT Forex - The Weekly Bias - Excellence in Short Term TradingOG BerryPas encore d'évaluation

- Time Value - Future ValueDocument4 pagesTime Value - Future ValueSCRBDusernmPas encore d'évaluation

- PPE PART 1 SummaryDocument3 pagesPPE PART 1 SummaryunknownPas encore d'évaluation

- Ifnotes PDFDocument188 pagesIfnotes PDFmohammed elshazaliPas encore d'évaluation

- Written Math Solutions and Word ProblemsDocument1 pageWritten Math Solutions and Word ProblemsShakir AhmadPas encore d'évaluation

- 1.a. PPT1 CR COLL Nature and Functions of CreditDocument41 pages1.a. PPT1 CR COLL Nature and Functions of CreditRoi Martin A. De VeyraPas encore d'évaluation

- CH 7 Stocks Book QuestionsDocument9 pagesCH 7 Stocks Book QuestionsSavy DhillonPas encore d'évaluation

- PRESENT VALUE TABLE TITLEDocument2 pagesPRESENT VALUE TABLE TITLEChirag KashyapPas encore d'évaluation

- FICO Configuration Transaction CodesDocument3 pagesFICO Configuration Transaction CodesSoumitra MondalPas encore d'évaluation

- City College of Calamba: Business Education DepartmentDocument71 pagesCity College of Calamba: Business Education DepartmentDae JaserPas encore d'évaluation

- Modern Greek Debt Tragedy Was Created by Goldman Sachs: Flying MachineDocument2 pagesModern Greek Debt Tragedy Was Created by Goldman Sachs: Flying MachineZerina BalićPas encore d'évaluation

- INTERMEDIATE ACCOUNTING-Unit01Document24 pagesINTERMEDIATE ACCOUNTING-Unit01Rattanaporn TechaprapasratPas encore d'évaluation