Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Nephrology Quiz Questionnaire - 2

Transféré par

Lp Saikumar DoradlaTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Nephrology Quiz Questionnaire - 2

Transféré par

Lp Saikumar DoradlaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Special Feature

Nephrology Quiz and Questionnaire: Transplantation

Donald E. Hricik (Discussant),* Richard J. Glassock (Co-Moderator),

and Anthony J. Bleyer (Co-Moderator)

Summary

Presentation of the Nephrology Quiz and Questionnaire (NQQ) has become an annual tradition at the meetings of

the American Society of Nephrology. It is a very popular session judged by consistently large attendance. Members of

the audience test their knowledge and judgment on a series of case-oriented questions prepared and discussed by

experts. They can also compare their answers in real time, using audience response devices, to those of program

directors of nephrology training programs in the United States, acquired through an Internet-based questionnaire.

Topics presented here include transplantation issues. These cases, along with single best answer questions, were

prepared by Dr. Hricik. After the audience responses, the correct and incorrect answers were then briey

discussed and the results of the questionnaire were displayed. This article aims to recapitulate the session and re-

produce its educational value for a larger audiencethat of the readers of the Clinical Journal of the AmericanSociety

of Nephrology. Have fun.

Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 0: cccccc, 2012. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01730212

Case 1: Donald E. Hricik (Discussant)

A 53-year-old man with ESRD secondary to IgA

nephropathy received a kidney transplant from a

deceased donor 6 months ago. The patient received

induction antibody therapy with rabbit antithymo-

cyte globulin. Serum creatinine concentrations ranged

between 1.3 and 1.6 mg/dl during the previous 4

months. Maintenance immunosuppression consisted

of tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone.

Other medications include metoprolol, trimethoprim-

sulfamethoxazole, omeprazole, and ergocalciferol. One

week earlier, a serum creatinine concentration was 1.8

mg/dl and a repeat level was 2.0 mg/dl. Results on

surveillance blood PCR for BK polyoma virus were

negative 3 months after transplantation but now show

a viral level of 5000 copies/mL. The patient is entirely

asymptomatic. On examination, his body temperature is

37.2C and his BP is 138/88 mmHg. There is no allo-

graft tenderness. Doppler ultrasonography of the trans-

planted kidney shows no hydronephrosis and mildly

increased resistive indices. A biopsy of the trans-

planted kidney is performed. The pathologist reviews

the light microscopic ndings and notes lymphocytic

inltrates in 20% of the core, as well as mild tubulitis.

Findings are Banff grade suspicious for acute rejec-

tion. No glomerular abnormalities are present.

Question 1A

An immunostain of the transplant renal biopsy to

which ONE of the following antigens would be MOST

helpful in guiding subsequent management (see Figure 1)?

A. C4d complement

B. IgA

C. Simian virus 40 (SV40)

D. JC polyomavirus

E. C3 complement

Discussion of Case 1 (Question 1A)

The best choice is C. The detection of BK polyoma

viremia in a kidney transplant recipient with an in-

creasing serum creatinine concentration raises a

serious concern for BK polyoma virus nephropathy.

Transplant renal biopsy represents the gold standard

for diagnosis of BK polyoma virus nephropathy. How-

ever, in the early stages of this disorder, classic cyto-

pathic changes in epithelial cells may be minimal, and

interstitial inammation, including tubulitis, can be

confused with acute cellular rejection (1,2).

The polyoma viruses are a group of species-specic

small-DNA viruses that include human pathogens

(BK and JC viruses) and the primate pathogen (SV40)

(1). The BK virus shares 70% of DNA sequence ho-

mology with SV40, and immunostaining against the

latter virus forms the basis for the immunohistochem-

ical diagnosis of BK polyoma nephropathy. Antibodies

to BK polyoma virus can be detected in approximately

80% of adults. Viral infection typically occurs in child-

hood and is then followed by a latent state with viral

presence in the uroepithelium, lymphoid tissues, and

brain (3). In the rst year after transplantation, 10%20%

of kidney transplant recipients develop BK viremia.

Reduction of immunosuppression is the mainstay of

therapy (4). With aggressive surveillance protocols,

aimed to detect viremia before the development of

impaired kidney function, graft loss now occurs in less

than 5% of viremic patients. The risk for graft loss is

related to histologic stage, starting with mild inam-

mation (tubulitis), increasing to cytopathic changes in

tubular epithelial cells, and followed by progressive

brosis.

Immunostaining for IgA and C3 would be of some

interest in this patient with underlying IgA nephrop-

athy. However, the absence of glomerular abnor-

malities rules against recurrent IgA nephropathy.

*Division of

Nephrology and

Hypertension,

Department of

Medicine, University

Hospitals Case

Medical Center,

Cleveland, Ohio;

David Geffen School

of Medicine at UCLA,

Los Angeles,

California; and

Section on

Nephrology, Wake

Forest Medical

School, Winston-

Salem, North Carolina

Correspondence: Dr.

Anthony J. Bleyer,

Section on Nephrology,

Wake Forest University

School of Medicine,

Medical Center

Boulevard, Winston-

Salem, NC 27157.

Email: ableyer@

wakehealth.edu

www.cjasn.org Vol 0 , 2012 Copyright 2012 by the American Society of Nephrology 1

. Published on May 17, 2012 as doi: 10.2215/CJN.01730212 CJASN ePress

Furthermore, recurrence of the original disease would

probably not account for marked interstitial inammation

noted on light microscopy. The detection of C4d deposits in

peritubular capillaries represents the histopathologic hall-

mark of acute humoral rejection (5). Unless the pathologist

noted peritubular capillaritis on light microscopy, acute

humoral rejection would not be a serious concern in this

case at this point. The presence of BK viremia, with or

without overt nephropathy, is generally believed to reect

overimmunosuppression (4), in which concurrent cellular

or humoral rejection would be distinctly unusual.

Case 1, continued

Tacrolimus treatment was discontinued and the dose of

mycophenolate mofetil was reduced by 25%. One month

later, results of blood PCR for BK polyoma virus were

negative and the serum creatinine level decreased slightly

to 1.7 mg/dl. Two months later, routine laboratory testing

revealed a serum creatinine concentration of 3.2 mg/dl.

Repeat biopsy showed acute humoral rejection with pos-

itive staining for C4d. Two donor-specic antibodies were

detectable in high titers. Tacrolimus treatment was renewed.

Despite a trial of pulse steroid therapy, plasmapheresis, and

intravenous immunoglobulin, the patient exhibited pro-

gressive renal dysfunction and returned to dialysis treat-

ment 6 months later. One month later, the patient tells you

that a friend from his church wishes to be evaluated as a

possible living donor (Figure 2). He continues to receive

tacrolimus and prednisone.

Question 1B

What is your BEST advice regarding retransplantation

with a living unrelated donor?

A. The rst transplanted kidney is a reservoir for BK polyoma

virus and must be removed before a second transplant.

B. Deceased-donor transplantation is preferred because the

risk for recurrent BK polyoma virus nephropathy is lower

than that with a related donor.

Figure 1. | Responses to question 1A: Immunostaining against which antibody is most likely to guide subsequent management? (Correct

answer: C.)

Figure 2. | Responses to question 1B: What is the best advice regarding re-transplantation with a living unrelated donor? (Correct answer: C.)

2 Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology

C. Repeat BKpolyoma blood PCRshould be performed. If result

is negative, he should continue current immunosuppression

until the second transplantation is performed.

D. Irrespective of the current BKviral load, tacrolimus must be

weaned and discontinued before a second transplant.

Discussion of Case 1 (Question 1B)

The best choice is C. The clinical predicament presented

by this case brings up two controversial management issues:

(1) the role of transplant nephrectomy before retransplanta-

tion in a patient with a previous graft loss due to BK poly-

oma nephropathy and (2) general management of a patient

with a previously failed allograft.

Because BK polyoma virus can become latent in uro-

epithelial tissues, there is a logical concern that retention of

the failed allograft will create a reservoir for re-infection

of a new graft. However, there is some evidence that BK

present in the donor kidney may serve as the source of the

infection in the recipient, at least in the rst year after

transplantation (3). Moreover, clinical experience has sug-

gested that the risk for BK polyoma nephropathy in a sec-

ond transplant is not inuenced by removal of a previous

graft (6,7). In a recent retrospective study of 31 patients

undergoing retransplantation within a median of 6 months

after graft failure from BK nephropathy, 35% developed

recurrent BK viremia but only 6% developed overt ne-

phropathy (7). Clearance of previous BK viremia was the

only factor associated with lack of recurrence, and the ef-

fects of prior nephrectomy were not signicant.

Controversies regarding the general management of the

patient with a failed graft focus on practices for weaning

immunosuppression and on the role of transplant nephrec-

tomy (8). It is generally recognized that complete weaning

of immunosuppression can lead to increased generation of

anti-HLA antibodies that may limit opportunities for re-

transplantation. However, for patients requiring long

waiting times for deceased-donor kidney transplantation,

continued immunosuppression will increase the risk for

infection. Retrospective studies suggest that removal of a

failed allograft and discontinuation of immunosuppression

may decrease mortality rates and increase the chances of

retransplantation (9). One theory behind these observations

is that the allograft tissue acts as a source of inammation.

However, such studies are fundamentally awed by retro-

spective designs that fail to consider important biases in the

selection of patients for transplant nephrectomy (10). More-

over, other studies suggest that removal of the allograft

actually increases the circulating levels of anti-HLA anti-

bodies (11). The theory here is that the allograft tissue acts

as a sponge for circulating antibodies. There is no con-

sensus about the optimal timing of nephrectomy and wean-

ing of immunosuppression after graft failure. However, in

this case, the availability of a live donor will allow for rel-

atively rapid retransplantation, and one can make a strong

argument to continue immunosuppression to prevent HLA

sensitization, so long as BK viremia is under control. Donor

source (i.e., living versus deceased donor) has not been

identied as a risk factor for BK polyoma viremia after

kidney retransplantation (12).

Case 2: Donald E. Hricik (Discussant)

A 65-year-old man with ESRD due to chronic GN (of

unknown nature) had a previous kidney transplant that

failed 3 years ago. He then began receiving long-term

hemodialysis and was on the waiting list for another kidney

transplant. He continued to work full-time as an attorney. Two

years ago, he was hospitalized for an upper gastrointestinal

hemorrhage resulting from gastric erosions and received 6

units of packed red blood cells. He is now highly sensitized

against HLA antigens; recent ow cytometrymeasured

panel-reactive antibody levels were 92% for class I antigens

Figure 3. | Responses to question 2: Which fact concerning donors after cardiac death is correct? (Correct answer: C.)

Table 1. Criteria for dening an expanded-criteria donor

1. Deceased donor age . 60 yr

OR

2. Deceaseddonor age 5059 yr with $2 of the following:

history of hypertension

terminal serum creatinine concentration .1.5 mg/dl

death from cerebral vascular accident

Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 0: cccccc, , 2012 Nephrology Quiz and Questionnaire: Transplantation, Hricik et al. 3

and 94% for class II antigens. He had previously signed a

consent form agreeing to consider an expanded-criteria

donor (ECD). The patient has been allocated a kidney allo-

graft from a donor after cardiac death (DCD), a 49-year-old

male drowning victim (Figure 3).

Question 2

The patients concerns about accepting this allograft would

BEST be allayed by which ONE of the following facts?

A. Kidneys fromDCDdonors exhibit rates of allograft survival

equivalent to those from ECDs.

B. Kidneys from DCD donors exhibit rates of delayed graft

function similar to those from standard-criteria donors

(SCDs).

C. Kidneys from DCD donors exhibit allograft survival rates

equivalent to those from SCDs.

D. Kidneys from DCD donors exhibit rates of primary non-

function lower than those from ECDs.

Discussion of Case 2 (Question 2)

The correct choice is C, given data from the Scientic

Registry for Transplant Recipients. The denition of an

ECD (Table 1) was derived from a large multivariate

analysis that sought to identify risk factors that collec-

tively posed a 70% increase in the relative risk for graft

loss compared with relatively healthy, younger donors,

also known as SCDs (13). DCDs are donors with terminal

illnesses but intact brain function. Organs from DCDs are

harvested quickly after declaration of asystole. Because

varying degrees of warm ischemia are involved in the

harvesting of DCD organs, it is no surprise that recipients

of these organs experience relatively high rates of delayed

graft function or even primary nonfunction (14). How-

ever, long-term follow-up of patients receiving kidneys

from DCDs indicate that both patient and graft survival

are similar to those achieved with brain-dead donors (15)

(Figure 4), whereas graft survival of DCD recipients is

actually superior to that of ECD recipients (15).

Disclosures

None.

References

1. Wiseman AC: Polyomavirus nephropathy: A current perspec-

tive and clinical considerations. Am J Kidney Dis 54: 131142,

2009

2. Drachenberg CB, Papadimitriou JC: Polyomavirus-associated

nephropathy: Update in diagnosis. Transpl Infect Dis 8: 6875,

2006

3. Bohl DL, Storch GA, Ryschkewitsch C, Gaudreault-Keener M,

Schnitzler MA, Major EO, Brennan DC: Donor origin of BK virus

in renal transplantation and role of HLA C7 in susceptibility to

sustained BK viremia. Am J Transplant 5: 22132221, 2005

4. Babel N, Fendt J, Karaivanov S, Bold G, Arnold S, Sefrin A, Lieske

E, Hoffzimmer M, Dziubianau M, Bethke N, Meisel C, Gru tz G,

Reinke P: Sustained BK viruria as an early marker for the de-

velopment of BKV-associated nephropathy: Analysis of 4128

urine and serum samples. Transplantation 88: 8995, 2009

5. Colvin RB: Antibody-mediated renal allograft rejection: Di-

agnosis and pathogenesis. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 10461056,

2007

6. Hirsch HH, Ramos E: Retransplantation after polyomavirus-

associated nephropathy: Just do it? Am J Transplant 6: 79, 2006

7. Geetha D, Sozio SM, Ghanta M, Josephson M, Shapiro R,

Dadhania D, Hariharan S: Results of repeat renal transplantation

after graft loss from BK virus nephropathy. Transplantation 92:

781786, 2011

8. Gill JS: Managing patients with a failed kidney transplant: How

can we do better? Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 20: 616621,

2011

9. Ayus JC, Achinger SG, Lee S, Sayegh MH, Go AS: Transplant

nephrectomy improves survival following a failed renal allograft.

J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 374380, 2010

10. Schaefer HM, Helderman JH: Allograft nephrectomy after

transplant failure: should it be performed in all patients returning

to dialysis? J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 207208, 2010

Figure 4. | Allograft and patient survival after kidney transplantation using donors after cardiac death (DCD) and donors after brain death

(DBD). Data obtained from reference 14.

4 Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology

11. Knight MG, Tiong HY, Li J, Pidwell D, Goldfarb D: Transplant

nephrectomy after allograft failure is associated with allosensi-

tization. Urology 78: 314318, 2011

12. Dharnidharka VR, Cherikh WS, Neff R, Cheng Y, Abbott KC: Re-

transplantation after BKvirus nephropathy in prior kidney transplant:

An OPTNdatabase analysis. Am J Transplant 10: 13121315, 2010

13. Merion RM, Ashby VB, Wolfe RA, Distant DA, Hulbert-Shearon

TE, Metzger RA, Ojo AO, Port FK: Deceased-donor character-

istics and the survival benet of kidney transplantation. JAMA

294: 27262733, 2005

14. Cohen DJ, St Martin L, Christensen LL, Bloom RD, Sung

RS: Kidney and pancreas transplantation in the United

States, 1995-2004. Am J Transplant 6[suppl 2]: 11531169,

2006

15. Rao PS, Ojo A: The alphabet soup of kidney transplantation: SCD,

DCD, ECDfundamentals for the practicing nephrologist. Clin

J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 18271831, 2009

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.

cjasn.org.

Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 0: cccccc, , 2012 Nephrology Quiz and Questionnaire: Transplantation, Hricik et al. 5

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- S2 Sample1Document5 pagesS2 Sample1Lp Saikumar DoradlaPas encore d'évaluation

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Critical Care Emergency Medicine 03Document5 pagesCritical Care Emergency Medicine 03Cynthia CameliaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Kidney BiopsyDocument6 pagesKidney BiopsyLp Saikumar DoradlaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Itas2010 - Indiantakayasu'S Arteritis Activity ScoreDocument2 pagesItas2010 - Indiantakayasu'S Arteritis Activity ScoreLp Saikumar DoradlaPas encore d'évaluation

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Polymixin Vs ColistinDocument2 pagesPolymixin Vs ColistinLp Saikumar DoradlaPas encore d'évaluation

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Vascular AccessDocument6 pagesVascular AccessLp Saikumar DoradlaPas encore d'évaluation

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

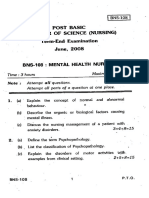

- Post Basic Bachelor of Sctence (Nursing) ' Term-End Examination June, 2OO8Document2 pagesPost Basic Bachelor of Sctence (Nursing) ' Term-End Examination June, 2OO8Lp Saikumar DoradlaPas encore d'évaluation

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Indian CKD GuidelinesDocument63 pagesIndian CKD GuidelinesLp Saikumar DoradlaPas encore d'évaluation

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- First Clinical Guidelines On Acute Kidney Injury Issued (Printer-Friendly)Document3 pagesFirst Clinical Guidelines On Acute Kidney Injury Issued (Printer-Friendly)Lp Saikumar DoradlaPas encore d'évaluation

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Electrolyte Quiz 2008Document38 pagesElectrolyte Quiz 2008Lp Saikumar Doradla100% (2)

- AKI BiomarkersDocument6 pagesAKI BiomarkersLp Saikumar DoradlaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- 2014 DM MCH ProspectusDocument22 pages2014 DM MCH ProspectusLp Saikumar DoradlaPas encore d'évaluation

- DM MCH 14 Bhu NotificationDocument4 pagesDM MCH 14 Bhu NotificationLp Saikumar DoradlaPas encore d'évaluation

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- UrologyDocument22 pagesUrologyLp Saikumar DoradlaPas encore d'évaluation

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Indian CKD GuidelinesDocument63 pagesIndian CKD GuidelinesLp Saikumar DoradlaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- CardiologyDocument30 pagesCardiologyLp Saikumar DoradlaPas encore d'évaluation

- IrcDocument129 pagesIrcFreddy RojasPas encore d'évaluation

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Renal BiopsyDocument11 pagesRenal BiopsyKiess11Pas encore d'évaluation

- TGA Letter of Demand - 4 July 2023Document30 pagesTGA Letter of Demand - 4 July 2023Tim BrownPas encore d'évaluation

- Oncogenic VirusesDocument83 pagesOncogenic VirusespthamainiPas encore d'évaluation

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Midterm Micro-2 Virology Lesson-2Document3 pagesMidterm Micro-2 Virology Lesson-2MYLENE POSTREMOPas encore d'évaluation

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Oncogenic VirusesDocument25 pagesOncogenic VirusesMedicina 19Pas encore d'évaluation

- Enveloped and Non Enveloped VirusDocument10 pagesEnveloped and Non Enveloped ViruspixholicPas encore d'évaluation

- Viral OncogenesisDocument36 pagesViral OncogenesisyuanlupePas encore d'évaluation

- Oncogene: Viral OncogenesDocument12 pagesOncogene: Viral OncogenesIlyas Khan AurakzaiPas encore d'évaluation

- Viro 1Document6 pagesViro 1Elsa YuniaPas encore d'évaluation

- 16 Oncogenic Viruses)Document32 pages16 Oncogenic Viruses)Ahmed EisaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- PapovavirusesDocument25 pagesPapovavirusesIGA ABRAHAMPas encore d'évaluation

- COMPREHENSIVE MycoviroDocument208 pagesCOMPREHENSIVE MycoviroMartin JustoPas encore d'évaluation

- Simian Virus 40 Infection in Humans and Association With Human Diseases: Results and HypothesesDocument9 pagesSimian Virus 40 Infection in Humans and Association With Human Diseases: Results and HypothesesMilan PetrikPas encore d'évaluation

- Malaria and Some Polyomaviruses (Sv40, BK, JC, and Merkel Cell Viruses)Document365 pagesMalaria and Some Polyomaviruses (Sv40, BK, JC, and Merkel Cell Viruses)zahidPas encore d'évaluation

- MCQs in Medical MicrobiologyDocument14 pagesMCQs in Medical Microbiologysidharta_chatterjee100% (8)

- សំណួរត្រៀមDocument1 480 pagesសំណួរត្រៀមNobel PelPas encore d'évaluation

- WartsDocument167 pagesWartseva yustianaPas encore d'évaluation

- Diagnosis of Viral Infections in Animal TissuesDocument3 pagesDiagnosis of Viral Infections in Animal TissuesRandy Butternubs100% (2)

- Horowitz Aids and EbolaDocument11 pagesHorowitz Aids and EboladeliriousheterotopiasPas encore d'évaluation

- Poliomavirus BKDocument30 pagesPoliomavirus BKRobin Gonzalez100% (1)

- Virus-Klasifikasi, Sifat, GenetikaDocument24 pagesVirus-Klasifikasi, Sifat, GenetikaRamano Untoro PutroPas encore d'évaluation

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Viral Oncogenesis DR - Fokam-JosephDocument31 pagesViral Oncogenesis DR - Fokam-JosephRosemary FuanyiPas encore d'évaluation

- Understanding Genitourinary System CytologyDocument130 pagesUnderstanding Genitourinary System Cytologyaaes2Pas encore d'évaluation

- 4-Week UFAPS With FA 2021Document2 pages4-Week UFAPS With FA 2021susannahshinyPas encore d'évaluation

- Cam4 5 1239Document12 pagesCam4 5 1239kadiksuhPas encore d'évaluation

- Virus-Klasifikasi, Sifat, GenetikaDocument26 pagesVirus-Klasifikasi, Sifat, Genetikanovia putriPas encore d'évaluation

- Polyomavirus LectureDocument60 pagesPolyomavirus Lecturerggefrm75% (4)

- French Molt Disease: Nasih Hamad Ali College of Veterinary Medicine University of SulaimaniDocument12 pagesFrench Molt Disease: Nasih Hamad Ali College of Veterinary Medicine University of Sulaimaninasih hamadPas encore d'évaluation

- Pox, Parvo, Adeno and Papova VirusesDocument33 pagesPox, Parvo, Adeno and Papova VirusesmicroperadeniyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Clinical Virology Manual (PDFDrive)Document639 pagesClinical Virology Manual (PDFDrive)Shweta KumariPas encore d'évaluation

- Cancer Associated Viruses, (2012) (UnitedVRG)Document868 pagesCancer Associated Viruses, (2012) (UnitedVRG)anon ankon100% (2)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedD'EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (80)

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossD'EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (6)