Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Finland Edu System

Transféré par

Ibrahim AbuDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Finland Edu System

Transféré par

Ibrahim AbuDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

European Commission

Organisation of

the education system in

Finland

2009/2010

FI

E URYBAS E F I NL AND

1

1. POLITICAL, SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC BACKGROUND AND TRENDS.............................................................. 7

1.1. Historical Overview.................................................................................................................................. 7

1.2. Main Executive and Legislative Bodies ................................................................................................... 8

1.3. Religions................................................................................................................................................. 10

1.4. Official and Minority Languages ........................................................................................................... 10

1.5. Demographic Situation ......................................................................................................................... 10

1.6. Economic Situation................................................................................................................................ 11

1.7. Statistics ................................................................................................................................................. 11

2. GENERAL ORGANISATION OF THE EDUCATION SYSTEM AND ADMINISTRATION OF EDUCATION........... 17

2.1. Historical Overview................................................................................................................................ 17

2.2. Ongoing Debates and Future Developments....................................................................................... 18

2.3. Fundamental Principles and Basic Legislation...................................................................................... 18

2.4. General Structure and Defining Moments in Educational Guidance................................................... 20

2.5. Compulsory Education .......................................................................................................................... 22

2.6. General Administration ......................................................................................................................... 23

2.6.1. National Level ................................................................................................................................. 23

2.6.2. Regional Level ................................................................................................................................. 25

2.6.3. Local Level....................................................................................................................................... 25

2.6.4. Educational Institutions, Administration, Management................................................................ 27

2.7. Internal and External Consultation between Levels of Education....................................................... 30

2.7.1. Internal Consultation...................................................................................................................... 30

2.7.2. Consultation Involving Players in Society at Large........................................................................ 31

2.8. Methods of Financing Education .......................................................................................................... 34

2.8.1. Pre-primary Level ............................................................................................................................ 34

2.8.2. Basic Education and General Upper Secondary Level ................................................................... 34

2.8.3. Vocational Upper Secondary Level ................................................................................................ 35

2.8.4. Higher Education Level................................................................................................................... 36

2.8.5. Adult Education and Training......................................................................................................... 37

2.9. Statistics ................................................................................................................................................. 40

3. PRE-PRIMARY EDUCATION........................................................................................................................... 42

3.1. Historical Overview................................................................................................................................ 43

3.2. Ongoing Debates and Future Developments....................................................................................... 44

3.3. Specific Legislative Framework ............................................................................................................. 45

3.4. General objectives ................................................................................................................................. 45

3.5. Geographical Accessibility..................................................................................................................... 46

3.6. Admission Requirements and Choice of Institution/Centre ................................................................ 46

3.7. Financial Support for Pupils Families ................................................................................................... 47

3.8. Age Levels and Grouping of Children................................................................................................... 47

3.9. Organisation of Time ............................................................................................................................. 48

3.9.1. School Year...................................................................................................................................... 48

3.9.2. Weekly and Daily Timetable ........................................................................................................... 48

3.10. Curriculum, Types of Activity, Number of Hours ................................................................................ 48

3.11. Teaching Methods and Materials........................................................................................................ 49

3.12. Evaluation of Children ......................................................................................................................... 49

3.13. Support Facilities ................................................................................................................................. 50

3.14. Private Sector Provisions ..................................................................................................................... 50

3.14.1. Historical overview........................................................................................................................ 51

3.14.2. Ongoing Debates and Future Development ............................................................................... 51

3.14.3. Specific legislative framework...................................................................................................... 51

3.15. Organisational Variations and Alternative Structures ........................................................................ 51

3.16. Statistics ............................................................................................................................................... 51

4. SINGLE STRUCTURE EDUCATION ................................................................................................................. 53

4.1. Historical Overview................................................................................................................................ 53

4.2. Ongoing Debates and Future Developments....................................................................................... 54

4.3. Specific Legislative Framework ............................................................................................................. 55

4.4. General Objectives................................................................................................................................. 56

4.5. Geographical Accessibility..................................................................................................................... 56

4.6. Admission Requirements and Choice of School................................................................................... 56

E URYBAS E F I NL AND

2

4.7. Financial Support for Pupils Families ................................................................................................... 57

4.8. Age Levels and Grouping of Pupils ....................................................................................................... 57

4.9. Organisation of School Time ................................................................................................................. 57

4.9.1. School Year in Basic Education....................................................................................................... 57

4.9.2. Weekly and Daily Timetable in Compulsory Basic Education........................................................ 58

4.10. Curriculum, Subjects, Number of Hours ............................................................................................. 58

4.10.1. The Syllabus of Basic Education ................................................................................................... 58

4.11. Teaching Methods and Materials........................................................................................................ 60

4.12. Pupil Assessment ................................................................................................................................. 61

4.13. Progression of Pupils ........................................................................................................................... 62

4.14. Certification.......................................................................................................................................... 62

4.15. Educational Guidance.......................................................................................................................... 63

4.16. Private Education................................................................................................................................. 64

4.17. Organisational Variations and Alternative Structures ........................................................................ 65

4.18. Statistics ............................................................................................................................................... 65

5. UPPER SECONDARY AND POST- SECONDARY NON-TERTIARY EDUCATION.............................................. 67

5.1. Historical Overview................................................................................................................................ 68

5.1.1. General Upper Secondary Education............................................................................................. 68

5.1.2. Vocational Upper Secondary Education and Training................................................................... 68

5.2. Ongoing Debates and Future Developments....................................................................................... 69

5.2.1. General Upper Secondary Education............................................................................................. 70

5.2.2. Vocational Upper Secondary Education and Training................................................................... 70

5.3. Specific Legislative Framework ............................................................................................................. 71

5.4. General Objectives................................................................................................................................. 72

5.4.1. General Upper Secondary Education............................................................................................. 72

5.4.2. Vocational Upper Secondary Education and Training................................................................... 73

5.5. Types of Institution................................................................................................................................ 74

5.5.1. General Upper Secondary Education............................................................................................. 74

5.5.2. Vocational Upper Secondary Education and Training................................................................... 74

5.6. Geographical Accessibility..................................................................................................................... 75

5.7. Admission Requirements and Choice of School................................................................................... 75

5.7.1. General Upper Secondary Education............................................................................................. 76

5.7.2. Vocational Upper Secondary Education ........................................................................................ 76

5.8. Registration and/or Tuition Fees........................................................................................................... 77

5.9. Financial Support for Pupils .................................................................................................................. 77

5.10. Age Levels and Grouping of Students ................................................................................................ 78

5.11. Specialisation of Studies...................................................................................................................... 79

5.11.1. General Upper Secondary Education........................................................................................... 79

5.11.2. Vocational Upper Secondary Education and Training................................................................. 79

5.12. Organisation of School Time............................................................................................................... 80

5.12.1. School Year.................................................................................................................................... 80

5.12.2. Weekly and Daily Timetable ......................................................................................................... 80

5.13. Curriculum, Subjects, Number of Hours ............................................................................................. 81

5.13.1. General Upper Secondary Education........................................................................................... 81

5.13.2. Vocational Upper Secondary Education and Training................................................................. 83

5.14. Teaching Methods and Materials........................................................................................................ 85

5.14.1. General Upper Secondary Education........................................................................................... 85

5.14.2. Vocational Upper Secondary Education and Training................................................................. 85

5.15. Pupil Assessment ................................................................................................................................. 86

5.15.1. General Upper Secondary Education........................................................................................... 86

5.15.2. Vocational Upper Secondary Education and Training................................................................. 87

5.16. Progression of Pupils ........................................................................................................................... 89

5.16.1. General Upper Secondary Education........................................................................................... 89

5.16.2. Vocational Upper Secondary Education and Training................................................................. 90

5.17. Certification.......................................................................................................................................... 90

5.17.1. General Upper Secondary Education........................................................................................... 90

5.17.2. Vocational Upper Secondary Education and Training................................................................. 92

5.18. Educational/ Vocational Guidance, Education/ Employment links.................................................... 93

E URYBAS E F I NL AND

3

5.18.1. General Upper Secondary Education........................................................................................... 93

5.18.2. Vocational Upper Secondary Education and Training................................................................. 94

5.19. Private Education................................................................................................................................. 95

5.19.1. General Upper Secondary Level ................................................................................................... 95

5.19.2. Upper Secondary Vocational Level .............................................................................................. 95

5.20. Organisational Variations and Alternative Structures ........................................................................ 95

5.21. Statistics ............................................................................................................................................... 96

6. TERTIARY EDUCATION................................................................................................................................ 102

6.1. Historical Overview.............................................................................................................................. 104

6.1.1. University Education..................................................................................................................... 104

6.1.2. Professionally Oriented Higher Education................................................................................... 105

6.2. Ongoing Debates and Future Developments..................................................................................... 106

6.3. Specific Legislative Framework ........................................................................................................... 107

6.4. General Objectives............................................................................................................................... 108

6.4.1. University Education..................................................................................................................... 108

6.4.2. Professionally Oriented Higher Education................................................................................... 109

6.5. Types of Institution.............................................................................................................................. 109

6.5.1. University Education..................................................................................................................... 109

6.5.2. Professionally Oriented Higher Education................................................................................... 110

6.6. Admission Requirements .................................................................................................................... 110

6.6.1. University Education..................................................................................................................... 110

6.6.2. Professionally Oriented Higher Education................................................................................... 112

6.7. Registration and/or Tuition Fees......................................................................................................... 113

6.8. Financial Support for Students............................................................................................................ 113

6.9. Organisation of the Academic Year .................................................................................................... 114

6.10. Branches of Study, Specialisation...................................................................................................... 114

6.10.1. University Education................................................................................................................... 114

6.10.2. Professionally Oriented Higher Education................................................................................. 114

6.11. Curricula............................................................................................................................................. 115

6.11.1. University Education................................................................................................................... 115

6.11.2. Professionally Oriented Higher Education................................................................................. 116

6.12. Teaching Methods ............................................................................................................................. 117

6.13. Student Assessment .......................................................................................................................... 117

6.14. Progression of Studies ....................................................................................................................... 118

6.14.1. University Education................................................................................................................... 118

6.14.2. Professionally Oriented Higher Education................................................................................. 118

6.15. Certification........................................................................................................................................ 119

6.16. Educational/Vocational Guidance, Education/Employment Links .................................................. 120

6.17. Private Education............................................................................................................................... 120

6.17.1. Private professionally oriented higher education ..................................................................... 120

6.18. Organisational Variations and Alternative Structures ...................................................................... 121

6.18.1. Graduate Schools........................................................................................................................ 121

6.18.2. Open University Instruction ....................................................................................................... 121

6.19. Statistics ............................................................................................................................................. 122

7. CONTINUING EDUCATION AND TRAINING FOR YOUNG SCHOOL LEAVERS AND ADULTS...................... 127

7.1. Historical Overview.............................................................................................................................. 128

7.2. Ongoing Debates and Future Developments..................................................................................... 129

7.3. Specific Legislative Framework ........................................................................................................... 131

7.4. General Objectives............................................................................................................................... 132

7.5. Types of Institution.............................................................................................................................. 133

7.5.1. General Upper Secondary Schools for Adult Students................................................................ 134

7.5.2. Folk High Schools.......................................................................................................................... 134

7.5.3. Adult Education Centres............................................................................................................... 135

7.5.4. Study Centres and Educational Organisations ............................................................................ 135

7.5.5. Physical Education Centres........................................................................................................... 135

7.5.6. Institutions Providing Basic Art Education................................................................................... 136

7.5.7. Summer Universities..................................................................................................................... 136

E URYBAS E F I NL AND

4

7.5.8. Institutions Providing Vocational Education and Training and Vocational Adult Education

Centres.................................................................................................................................................... 136

7.5.9. Specialised Vocational Institutions............................................................................................... 137

7.5.10. Continuing Education Centres of Universities........................................................................... 137

7.5.11. Polytechnics ................................................................................................................................ 137

7.5.12. Counselling Organisations ......................................................................................................... 138

7.6. Geographical Accessibility................................................................................................................... 138

7.7. Admission Requirements .................................................................................................................... 139

7.8. Registration and Tuition Fees.............................................................................................................. 139

7.9. Financial Support for Learners ............................................................................................................ 139

7.9.1. Financial aid for students.............................................................................................................. 139

7.9.2. Adult education allowance........................................................................................................... 139

7.9.3. Scholarship for Qualified Employee............................................................................................. 140

7.9.4. Other ............................................................................................................................................. 140

7.10. Main Areas of Specialisation.............................................................................................................. 140

7.11. Teaching Methods ............................................................................................................................. 140

7.11.1. General adult education............................................................................................................. 140

7.11.2. Vocational Adult Education and Training .................................................................................. 141

7.12. Trainers............................................................................................................................................... 142

7.13. Learner Assessment/ Progression..................................................................................................... 142

7.13.1. General Adult Education............................................................................................................. 142

7.13.2. Vocational Adult Education and Training .................................................................................. 142

7.14. Certification........................................................................................................................................ 143

7.14.1. General adult education............................................................................................................. 143

7.14.2. Vocational Adult Education and Training .................................................................................. 143

7.15. Education/ Employment links ........................................................................................................... 143

7.16. Private Education............................................................................................................................... 143

7.17. Statistics ............................................................................................................................................. 144

8. TEACHERS AND EDUCATION STAFF........................................................................................................... 147

8.1. Initial Training of Teachers .................................................................................................................. 148

8.1.1. Historical Overview....................................................................................................................... 149

8.1.2. Ongoing Debates and Future Developments.............................................................................. 149

8.1.3. Specific Legislative Framework .................................................................................................... 150

8.1.4. Institutions, Levels and Models of Training.................................................................................. 151

8.1.5. Admission Requirements.............................................................................................................. 152

8.1.6. Curriculum, Special Skills, Specialisation...................................................................................... 154

8.1.7. Evaluation, Certificates ................................................................................................................. 159

8.1.8. Alternative Training Pathways...................................................................................................... 160

8.2. Conditions of Service of Teachers ....................................................................................................... 160

8.2.1. Historical Overview....................................................................................................................... 160

8.2.2. Ongoing Debates and Future Developments.............................................................................. 161

8.2.3. Specific Legislative Framework and Future Developments ........................................................ 161

8.2.4. Planning Policy.............................................................................................................................. 162

8.2.5. Entry to the Profession.................................................................................................................. 162

8.2.6. Professional Status........................................................................................................................ 163

8.2.7. Replacement measures ................................................................................................................ 163

8.2.8. Supporting Measures for Teachers............................................................................................... 163

8.2.9. Evaluation of Teachers.................................................................................................................. 164

8.2.10. In-service Teacher Training......................................................................................................... 164

8.2.11. Salaries ........................................................................................................................................ 167

8.2.12. Working Time and Holidays........................................................................................................ 168

8.2.13. Promotion, Advancement .......................................................................................................... 169

8.2.14. Transfers...................................................................................................................................... 169

8.2.15. Dismissal...................................................................................................................................... 169

8.2.16. Retirement and Pensions............................................................................................................ 170

8.3. School Administrative and Management Staff ................................................................................... 170

8.3.1. Requirements for Appointment as a School Head ...................................................................... 170

8.3.2. Conditions of Service.................................................................................................................... 171

E URYBAS E F I NL AND

5

8.4. Staff Involved in Monitoring Educational Quality............................................................................... 171

8.4.1. Requirements for Appointment as an Inspector ......................................................................... 171

8.4.2. Conditions of Service.................................................................................................................... 171

8.5. Educational Staff Responsible for Support and Guidance ................................................................. 171

8.6. Other Educational Staff or Staff working with Schools....................................................................... 171

8.7. Statistics ............................................................................................................................................... 173

9. EVALUATION OF EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS AND THE EDUCATION SYSTEM..................................... 175

9.1. Historical Overview.............................................................................................................................. 176

9.2. Ongoing Debates and Future Developments..................................................................................... 177

9.3. Administrative and Legislative Framework ........................................................................................ 177

9.4. Evaluation of Schools/Institutions....................................................................................................... 180

9.5. Evaluation of the Education System................................................................................................... 182

9.5.1. Evaluation at National Level ......................................................................................................... 182

9.5.2. Evaluation at Regional and Local Level ........................................................................................ 185

9.6. Research into Education linked to the Evaluation of the Education System..................................... 186

9.6.1. Databases and Registers supporting the Evaluation and Research of Education ...................... 186

10. SPECIAL EDUCATIONAL SUPPORT ........................................................................................................... 194

10.1. Historical Overview............................................................................................................................ 194

10.2. Ongoing Debates and Future Developments .................................................................................. 197

10.3. Definition and Diagnosis of the Target Groups(s) ............................................................................ 198

10.3.1. Separate education..................................................................................................................... 199

10.3.2. Mainstream education................................................................................................................ 199

10.4. Financial Support for Pupils' Families ............................................................................................... 200

10.5. Special Provision within Mainstream Education .............................................................................. 201

10.5.1. Specific Legislative Framework .................................................................................................. 203

10.5.2. General Objectives...................................................................................................................... 204

10.5.3. Specific Support Measures ......................................................................................................... 206

10.6. Separate Special Provision ................................................................................................................ 215

10.7. Special Measures for the benefit of immigrant Children/Pupils and those from ethnic minorities 216

10.7.1. Pre-primary Education................................................................................................................ 216

10.7.2. Basic Education........................................................................................................................... 216

10.8. Statistics ............................................................................................................................................. 218

11. EUROPEAN AND INTERNATIONAL DIMENSIONS IN EDUCATION........................................... 219

11.1. Historical Overview............................................................................................................................ 220

11.2. Ongoing Debates and Future Developments .................................................................................. 221

11.3. National Policy Guidelines/Specific Legislative Framework............................................................. 225

11.4. National Programmes and Initiatives................................................................................................ 227

11.4.1. Bilateral Programmes and Initiatives.......................................................................................... 228

11.4.2. Multilateral Programmes and Initiatives .................................................................................... 229

11.4.3. Other National Programmes and Initiatives............................................................................... 231

11.5. European/International Dimension through the National Curriculum........................................... 232

11.5.1. Pre-primary Education................................................................................................................ 232

11.5.2. Primary Education....................................................................................................................... 232

11.5.3. Upper Secondary and Post-Secondary Non-Tertiary Education............................................... 233

11.5.4. Tertiary Education....................................................................................................................... 234

11.5.5. Continuing Education and Training for Adults .......................................................................... 234

11.5.6. Teachers and Education Staff ..................................................................................................... 234

11.6. Mobility and Exchange...................................................................................................................... 234

11.7. Statistics ............................................................................................................................................. 235

GLOSSARY....................................................................................................................................................... 239

LEGISLATION................................................................................................................................................... 243

INSTITUTIONS ................................................................................................................................................. 252

BIBLIOGRAPHY................................................................................................................................................ 274

E URYBAS E F I NL AND

6

E URYBAS E F I NL AND

7

1. POLITICAL, SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC BACKGROUND

AND TRENDS

Education and research 20072012. Development Plan.

Government Institute for Economic Research

Institute for Educational Research

Ministry of Education

Ministry of Employment and the Economy

Ministry of Social Affairs and Health

National Institute for Health and Welfare (THL)

Research Unit for the Sociology of Education (RUSE)

Statistics Finland

The Association of Finnish Local and Regional Authorities

The Research Institute of the Finnish Economy

The Social Insurance Institution of Finland

Work Research Centre, University of Tampere

1.1. Historical Overview

Finland was annexed by Sweden during the Crusades (in the 12

th

century). Social and religious influences

from Sweden gave Finland connections to western culture. The Finnish written language was developed in

1543 by Mikael Agricola who wrote the first Finnish book, a textbook for teaching children to read and write.

The first grammar school where the language of instruction was Finnish was founded in 1858.

As a result of the Napoleonic Wars, Sweden surrendered Finland to Russia in 1809, and Finland then became

an autonomous Grand Duchy of Russia for one hundred years. However, legislation and the social system

from the Swedish era were preserved. After the Russian revolution in 1917, Finland started to disengage from

Russia in order to gain independence. Finland has been an independent state since December 6

th

1917.

The first complete reform of Finlands Constitution came into force on 1 March 2000. The new Constitution of

Finland replaced the old Constitution Act (1919), the Parliament Act (1928) and several other acts. The new

Constitution makes it easier to understand Finlands political system and different actors powers and mutual

relations.

E URYBAS E F I NL AND

8

Finlands political system has been developed in a more parliamentary direction by strengthening the role of

Parliament and the Government in relation to the President of the Republic. For example, the Prime Minister

is elected by Parliament. As a result of the new Constitution, Parliament has an even stronger position as the

supreme organ of state.

From the point of view of the countrys political system, an important event was the parliamentary reform of

1906, which led to the establishment of the unicameral Parliament. Universal and equal suffrage came into

force and also applied to women. Most of the parties whose members were elected to the first unicameral

Parliament still exist today.

In the 2007 parliamentary elections, the major parties won the following number of seats:

Finnish Centre Party 51

National Coalition Party 50

1)

Finnish Social Democratic Party 45

Left Alliance 17

Green Party of Finland 15

1)

Swedish Peoples Party 9

Christian Democrats 7

True Finns Party 5

Representative of the land islands (autonomous region) 1

2)

1)

One member of the Greens changed to National Coalition Party in February 2008.

2)

The autonomous region of the land Islands has the right to elect one representative to the Finnish

Parliament.

After the election in spring 2007 the new government was formed by the Finnish Centre Party, the National

Coalition Party, Green Party of Finland and the Swedish Peoples Party.

Finland joined the European Union in 1995.

1.2. Main Executive and Legislative Bodies

Finland is a parliamentary republic. The highest legislative power is vested in Parliament. The people elect

200 representatives to the Parliament every four years. In addition to legislative functions, Parliament

decides on the state budget, supervises Government actions and controls administration

General executive powers in administration are vested in the Government, which is responsible for the

preparation of legislation. In addition, the Government can also make decisions specifying statutes. The

Government must enjoy the confidence of Parliament.

The President of the Republic has a fairly independent status with respect to Parliament. The people elect the

President by direct vote for a term of six years. The President introduces government bills to Parliament and

ratifies laws. The President may choose not to ratify an act passed by Parliament and the law is thus deferred.

In addition, the President issues decrees. He or she is also Commander-in-Chief of the Defence Forces.

E URYBAS E F I NL AND

9

The Constitution of Finland was reformed at the turn of the century. The Constitution was confirmed by

Parliament on 11 June 1999 and came into force on 1 March 2000. It redefines the status of the President, for

example, by stipulating that the foreign policy of Finland is directed by the President of the Republic in co-

operation with the Government, no longer with sovereign authority.

The administrative system functioning under the executive and legislative bodies consists of central

administrative units, as well as intermediate level authorities and local level administration operating under

the former.

Central Administration

Traditionally, two structural principles have been followed within the States central administration in

Finland: the ministerial administrative system and the system of central administrative agencies. Each

ministry is led by someone with political responsibility, namely the minister. The central administrative

agencies function under the ministries; for example, the Finnish National Board of Education is a central

agency operating under the Ministry of Education. The ministries direct the central bodies in general, but

they do not intervene in their decisions in individual cases. Thus, the central bodies are comparatively

independent within their own field. They are publicly liable for the legality of their actions.

The system of central administrative agencies originated during the Swedish era. The number of central

agencies increased up until the 1970s. Subsequently, their number has been reduced by abolishing and

combining agencies. Thus, the administrative system has been developed towards the ministerial

administrative system.

Intermediate Level Administration

The intermediate level administration functions under the central administration. The intermediate level

administration was reformed from the beginning of 2010. All state provincial offices, employment and

economic centres, regional environmental centres, environmental permit agencies, road districts and

occupational health and safety districts were phased out and their functions and tasks were reorganised and

streamlined into two new regional state administrative bodies: the Regional State Administrative Agencies

(AVI) and the Centres for Economic Development, Transport and the Environment (ELY). The areas of

responsibility of the AVIs are basic public services, legal rights and permits, occupational safety and health,

environmental permits, fire and rescue services and preparedness and police. The areas of responsibility of

the ELYs are economic development, labour force, competence and cultural activities; transport and

infrastructure as well as the environment and natural resources. Both AVIs and ELYs have responsibilities in

the education sector.

Local Administration

The basic unit of local administration is the municipality (local authority). Every Finnish citizen belongs to a

municipality and there are 348 of them in total. The basis of municipal administration is an old principle of

self-government, and the municipalities opportunities for self-government have improved in recent years. In

order to realise the principles of self-government, the inhabitants of the municipalities elect representatives

to the municipal council. The highest power in the municipality is vested in the council. Executive and

administrative authority is entrusted to the municipal executive board and certain other bodies. Each local

authority is responsible for providing its population with services according to applicable legislation. The

local authorities may tax their inhabitants in order to produce services. The local authorities receive 16.8 per

cent (2007) of their income from the State.

E URYBAS E F I NL AND

10

The Ministry of Education

The Ministry of Education works a part of the Government. It promotes education and culture and also

creates requirements for know-how and creativity as well as the activity and well-being of the people. For

example education, science, young people and student financial aid fall within its field of responsibilities.

There are two ministers at the Ministry of Education: the Minister of Education and Science is responsible for

matters relating to education and research and the Minister of Culture and Sport for matters relating to

culture, sports, youth, copyright, student financial aid, and church affairs.

The Finnish National Board of Education

The Finnish National Board of Education is responsible for developing pre-primary education, basic

education, upper secondary school education, vocational upper secondary education, adult education and

liberal education (e.g. adult education centres (Finnish: kansalaisopisto, Swedish: medborgarinstitut), folk

high schools (Finnish: kansanopisto, Swedish: folkhgskola ), study centres, (Finnish: opintokeskus Swedish:

studiecentral ) and summer universities, Finnish: kesyliopisto Swedish: sommaruniversitet). The Finnish

National Board of Education develops education, evaluates education and offers information and support

services.

1.3. Religions

Finland has a Freedom of Religion Act, which guarantees the right to practise any religion, provided that the

law and/or common decency are not violated. The Evangelical Lutheran Church and the Orthodox Church

have special status among religious denominations; they have taxation rights, for example. The majority of

the population, 79.7 per cent, are members of the Evangelical Lutheran Church. Approximately 1 per cent of

the population are members of the Orthodox Church, and 17 per cent are not members of any religious

denomination.

Uskonnonvapauslaki

1.4. Official and Minority Languages

The official languages of Finland are Finnish and Swedish. Approximately 91.2 per cent of the population

have Finnish as their mother tongue, and about 5.4 per cent speak Swedish. Although the Swedish

population is concentrated on the coast, Finnish and Swedish are equal languages throughout the country

with respect to dealing with the authorities. The third of the languages Spoken in Finland is the regional

language, Saami (Lappish), which is spoken by approximately 1 800 people (0.03 per cent of the population)

as their mother tongue. The Saami-speaking population lives in the northernmost part of Finland, Lapland,

and they have the right to receive services from society in their mother tongue.

The official languages are languages of instruction in educational institutions on all educational levels.

Usually the institutions have either Finnish or Swedish as their languages of instruction, but there are upper

secondary vocational institutions and universities which bilingual. Saami is the language of instruction in

some basic education, upper secondary general and vocational institutions on the Saami-speaking areas.

1.5. Demographic Situation

E URYBAS E F I NL AND

11

There are about 5.3 million people in Finland over an area of 338 000 square kilometres. The average

population density is 17 inhabitants per km

2

. The population is concentrated in the south of the country,

particularly in the Helsinki capital area, which accounts for about a fifth of the entire population, equivalent

to approximately one million people. Approximately 84.3 per cent of the population live in densely

populated areas. In all, there are eight cities with more than 100 000 inhabitants.

According to the population forecast of Statistics Finland, the Finnish population will increase considerably

until the year 2040 if the current development continues. The total population is expected to be over 5.7

million people in 2040. The proportion of working-age population will decline from the current 66 percent

to 57 percent in 2040. In 2040, about a quarter of the population will be over 65 years of age.

There are relatively few foreign nationals in Finland they account for approximately 2.7 per cent of the

entire population. The largest group is formed by people from the territory of the former Soviet Union.

About one fifth have come from European Union countries.

1.6. Economic Situation

The economy and welfare have grown steadily in Finland throughout the period of independence until the

1990s. The strong growth trend has only been broken by the depression in the 1930s and the Second World

War, when production declined. After the war, there was another lengthy period of growth, during which

time the GDP increased by about 5 per cent a year. At the beginning of the 1990s, the Finnish national

economy was hit by the worst depression since the war.

The Finnish economy surged upwards again towards the end of 1993. At the same time, Finland started to

recover from the collapse of eastern trade caused by the disintegration of the Soviet Union, compensation

for which came through directing exports to other countries. Membership of the European Economic Area

and subsequent integration into the European Union increased the volume of trade with other Western

European countries.

In Finland the current global recession meant a constriction of the GDP by 7.5 per cent in 2009. In 2010 and

2011 it is expected that the GDP will grow again which would indicate that the recession is over in Finland.

However, the economy will be weak for several years and the unemployment rate will continue to increase. It

has been forecasted that the total production in Finland will reach the level of the year 2008 as late as in

2012.

Employment continued to rise up to the end of 2008. However, in early 2009 unemployment started

growing. The decline in labour supply, on the other hand, will bring labour shortages back in a few years'

time. Slower inflation and tax cuts will boost household purchasing power, but uncertainties related to the

future are hampering consumption growth.

1.7. Statistics

Political parties at the Parliament of Finland

The name of the party Seats at the Parliament,

E URYBAS E F I NL AND

12

elections in March 2007

Finnish Centre Party 51

National Coalition Party* 51

Finnish Social Democratic Party 45

Left Alliance 17

The Green Party of Finland* 14

Swedish People's Party 9

Christian Democrats 7

True Finns Party 5

Representative of the land islands (autonomous region) 1

Total 200

*A member of the Green Party changed to the National Coalition Party at the beginning of 2008 thus changing the seat distribution. At

the elections the Greens received 15 seats and the Coalition Party.

Population trends 1950 - 2030, by gender

Gender 1950 2000 2008 2010* 2030*

Men 1 926 161 2 529 341 2 611 653 2 627 306 2 798 428

Women 2 103 642 2 651 774 2 714 661 2 729 260 2 884 754

Total 4 029 803 5 181 115 5 326 314 5 356 566 5 683 182

* forecast

Source: Statistics Finland.

Population trends 1950 - 2030, by age group (as a percentage)

Age group 1950 2000 2008 2010 * 2030 *

0 14 30 18 17 16 16

15 64 63 67 67 66 58

65 7 15 17 17 26

* forecast

Source: Statistics Finland.

Population density, regional division 1 January 2008

Region

Land area km2 Population Population density per km2

E URYBAS E F I NL AND

13

1.1.2009 31.12.2008 1) 31.12.2008

Uusimaa 6 371 1 408 020 221.0

Eastern Uusimaa 2 761 93 491 33.9

Southwest Finland 10 664 461 177 43.2

Satakunta 7 956 227 652 28.6

Tavastia Proper 5 199 173 041 33.3

Pirkanmaa 12 446 480 705 38.6

Pijnne Tavastia 5 127 200 847 39.2

Kymenlaakso 5 112 182 754 35.8

South Karelia 5 613 134 448 24.0

Southern Savonia 13 997 156 632 11.2

Northern Savonia 16 772 248 423 14.8

North Karelia 17 763 166 744 9.4

Central Finland 16 708 271 747 16.3

Southern Ostrobothnia 13 444 193 511 14.4

Ostrobothnia 7 749 175 985 22.7

Central Ostrobothnia 5 273 71 029 13.5

Northern Ostrobothnia 35 230 386 144 11.0

Kainuu 21 506 83 160 3.9

Lapland 92 666 183 963 2.0

land Islands 1 553 27 456 17.7

Whole country 303 901 5 326 314 17.5

Source: Statistics Finland

GDP per capita 1990-2008, euros

Year EUR

E URYBAS E F I NL AND

14

1990 18 000

1991 17 092

1992 16 470

1993 16 566

1994 17 312

1995 18 778

1996 19 367

1997 20 939

1998 22 727

1999 23 765

2000 25 555

2001 26 960

2002 27 682

2003 27 995

2004 29 144

2005 29 964

2006 31 713

2007 33 947

2008* 34 663

*advance information.

Source: Statistics Finland.

Labour force and economically inactive population in 2008

(population aged 15 - 74, per 1 000)

Population

aged 15 - 74

Labour force Employed

Un-

employed

Econo-

mically

inactive

Labour force

partici-

pation rate

Un-

employm

ent rate

Women 2 011 1 301 1 202 99 710 59.8 % 7.6 %

Men 2 014 1 377 1 255 122 637 62.3 % 8.9 %

Total 4 025 2 678 2 457 221 1 347 61.1 % 8.2 %

Source: Statistics Finland

Immigration, emmigration and net immigration from 1987 to 2008

E URYBAS E F I NL AND

15

Year Immigration Emmigration Net immigration

1987 9 142 8 475 667

1988 9 720 8 447 1 273

1989 11 219 7 374 3 845

1990 13 558 6 477 7 081

1991 19 001 5 884 13 017

1992 14 554 6 055 8 499

1993 14 795 6 405 8 390

1994 11 611 8 672 2 939

1995 12 222 8 957 3 265

1996 13 294 10 587 2 707

1997 13 564 9 854 3 710

1998 14 192 10 817 3 375

1999 14 744 11 966 2 778

2000 16 895 14 311 2 584

2001 18 955 13 153 5 802

2002 18 113 12 891 5 222

2003 17 838 12 083 5 755

2004 20 333 13 656 6 677

2005 21 355 12 369 8 986

2006 22 451 12 107 10 344

2007 26 029 12 443 13 586

2008 29 114 13 657 15 457

Source: Statistics Finland

E URYBAS E F I NL AND

16

Foreign nationals living in Finland by their country of citizenship from 1990 to 2008

Country of citizenship: 1990 2000 2008

Russia - 20 552 26 909

Estonia - 10 839 22 604

Sweden 6 051 7 887 8 439

Somalia 44 4 190 4 919

China 312 1 668 4 620

Thailand 239 1 306 3 932

Germany 1 568 2 201 3 502

Turkey 310 1 784 3 429

Iraq 107 3 102 3 238

United Kingdom 1 365 2 207 3 213

India 270 756 2 736

Former Serbia and Montenegro - 1 204 2 637

Iran 336 1 941 2 508

United States 1 475 2 010 2 282

Viet Nam 292 1 814 2 270

Afghanistan 3 386 2 189

Poland 582 694 1 888

Ukraine - 961 1 798

Bosnia and Herzegovina - 1 627 1 723

Others 13 301 23 945 38 420

Total 26 255 91 074 143 256

Source: Statistics Finland

E URYBAS E F I NL AND

17

2. GENERAL ORGANISATION OF THE EDUCATION

SYSTEM AND ADMINISTRATION OF EDUCATION

2.1. Historical Overview

Finlands state administration during the Swedish era comprised a system of central administrative bodies

introduced in the 17th century; decision-making power in the system was held by field-specific central

bodies. The educational administration and the national board managing educational issues were not

established until the late 19th century; the Church took care of all educational matters until the State and the

Church were separated in 1869. In the same year, the Board of Education was founded, and it functioned as a

central body managing educational matters for over one hundred years.

The Board of Education, later known as the National Board of General Education, was primarily responsible

for general education. The administration of vocational education and training remained dispersed under

the auspices of different ministries. It was not until 1966 that a central administrative board in charge of

vocational education and training, the National Board of Vocational Education, was established to work

alongside the National Board of General Education. In 1991, these central boards were combined to form the

Finnish National Board of Education, which still functions and is responsible for both general education and

vocational education and training, with the exception of higher education. The Ministry of Education is the

responsible body for the higher education institutions. The Ministry concludes a so called agreement of

results with the higher education institutions for three-years-periods.

However, the traditional role of central administrative boards, which has included the strong steering of the

implementation of legislation, has changed during recent decades. Central boards have been combined and

dismantled as part of an overall streamlining of administration and a reduction in bureaucracy, and their

tasks have partly been transferred to ministries and partly to regional and local authorities. The aim has been

to shift from the system of central administrative agencies to the ministerial administrative system, which is

more common in other European countries. On the other hand, the objective has been to develop the

remaining central boards into expert and planning agencies operating under the auspices of the ministries.

Thus, the Government Decision-in-Principle, which led to the establishment of the Finnish National Board of

Education, speaks about the "expert body in education.

The transition towards the ministerial administrative system has strengthened the role of the Ministry of

Education. The influence of the Ministry on education policy decision-making has also become stronger,

particularly in the 1990s. The Ministrys more active role alongside the increased amount of planning

functions is demonstrated, for example, by two ministerial posts: since the 1970s there have usually been

two Ministers in the Ministry of Education, one handling matters related to education and science, and the

other cultural affairs. This division was also introduced to the Ministrys internal organisation in 1990, the

Minister of Education and Science has been responsible for education and science policies and the Minister

of Culture for cultural, sport and youth policies.

The educational administration was previously characterised by the States precise steering and control.

Since the 1980s, school legislation has been reformed, which has resulted in a continuous increase in the

decision-making powers of local authorities and educational institutions. Steering and control of the local

authorities educational administration through government subsidies has decreased dramatically, and the

local authorities cultural and educational administration is no longer steered by field-specific legislation to

any significant extent. The qualifications requirements for cultural and educational administrative posts have

E URYBAS E F I NL AND

18

been left at the discretion of the local authorities, and obligatory administrative offices, excluding school

heads, have been dismantled.

2.2. Ongoing Debates and Future Developments

The whole local administration system of Finland is under a process of reform. Within a few years, the

cooperation structure between the state and the municipalities may change, and also the number of the

independent municipalities may decrease.The funding reform is a part of the reform of municipalities and

services. There is a need to simplify the system for statutory government transfers to the municipalities. The

government funding for pre-primary and basic education was combined with the funding for social, health

and certain other types of expenditure at the beginning of 2010. These are transferred as a lump sum to the

local authorities. At the same time the municipalities are encouraged to mergings or increasing co-operation

with each others. At the beginning of 2010 the number of municipalities was 342, which is 73 municipalities

less than in 2008.

According to the Development Plan for 20072012 an objective is to strengthen the provider network for

vocational education and training. With a view to enhancing the service capacity of the network of training

providers in accordance with the vocational college strategy, providers will be merged into regional or

otherwise strong training providers, whose operations cover all vocational education and training services,

development activities and teaching units. The strategy aims also to strengthen the role of VET in regional

development. The concrete decisions about merging organisations are made by the VET providers

themselves, but the starting point is that there is at least a population of 50 000 in the region of one VET

provider.

The quality of operations, effectiveness and international competitiveness of higher education needs

strengthening in a changing and global operating environment. Developing the structures of higher

education is part of the present government programme. The new structures should be implemented by

2010. The aim is to decrease the number of polytechnics and universities and to make their profiles clearer. In

addition, their organisational structures should be based on bigger and more effective units. Also strategic

alliances between universities and polytechnics are encouraged. A few such alliances, mainly regional

alliances, have already been formed.

The administration of universities is being centralised. The new service centre Certia produces services for

financial and human resources management for the universities. The centre also offers expert services

related to IT management.

2.3. Fundamental Principles and Basic Legislation

Principles

The main objective of Finnish education policy is to offer all citizens equal opportunities to receive

education, regardless of age, domicile, financial situation, sex or mother tongue. Education is considered to

be one of the fundamental rights of all citizens. Firstly, provisions concerning fundamental educational rights

guarantee everyone (not just Finnish citizens) the right to free basic education; the provisions also specify

compulsory education. Basic and compulsory education is stipulated in more detail in the Basic Education

Act (see below). Secondly, the public authorities are also obligated to guarantee everyone an equal

opportunity to obtain other education besides basic education according to their abilities and special needs,

and to develop themselves without being prevented by economic hardship.

E URYBAS E F I NL AND

19

In addition, the public authorities are obligated to provide for the educational needs of the Finnish- and

Swedish-speaking population according to the same criteria. Approximately 5.5 per cent of the population

have Swedish as their mother tongue. Both language groups have the right to education in their own

mother tongue. Regulations on the language of instruction are stipulated in legislation concerning different

levels of education. The entirely Swedish-speaking Province of land has its own educational legislation.

Members of the Saami population living in the northernmost parts of Finland are an indigenous people, and

they have the right to maintain and develop their own language and culture. The Act on the Saami

Parliament came into force on 1 January 1996. The Act guarantees the Saami-speaking population cultural

autonomy concerning their language and culture. The Saami language can be the language of instruction in

basic education as well as in general and vocational upper secondary education and training, and it can also

be taught as the mother tongue or as a foreign language. In the four municipalities located in the Saami

domicile area, pupils speaking the Saami language must primarily be provided with basic education in that

language, should their parents so choose.

The aims of immigrant education, for both children and adults, include equality, functional bilingualism and

multiculturalism. The objective of immigrant education provided by different educational institutions is to

prepare immigrants for integration into the Finnish education system and society, to support their cultural

identity and to provide them with as well-functioning bilingualism as possible so that, in addition to Finnish

(or Swedish), they will also have a command of their own native language.

A major objective of Finnish education policy is to achieve as high a level of education and competence as

possible for the whole population. One of the basic principles behind this has been to offer post-compulsory

education to whole age groups. In international terms, a high percentage of each age group goes on to

upper secondary education when they leave comprehensive school, (Finnish: peruskoulu Swedish:

grundskola): almost 95 per cent of those completing basic education continue their studies in general upper

secondary schools, (Finnish: lukio Swedish: gymnasium) or vocational upper secondary education and

training. Issues of educational equality are among the key topics in the new Development Plan for Education

and Research for 20072012. Its objectives include raising the level of education of the population. The aim is

that in 92.5 per cent of the age group 25-34 years-olds will in 2015 pass an examination on upper secondary

or tertiary level. Other focuses of the development plan are the quality of education and training, securing

the availability of competent labour force, the development of higher education and the teachers as

important resources.

Legislation

The legislation governing primary and secondary level education as well as part of the legislation governing

adult education were reformed on 1 January 1999. The detailed legislation based on institutions has thus

been replaced with more uniform legislation concerning the objectives, contents, evaluation and levels of

education as well as students rights and responsibilities. The education system has remained unchanged,

but the new legislation has substantially increased the independent decision-making powers of the local

authorities, other education providers and schools. For example, education providers will decide

independently on the institutions to provide education. There is no regulation of working hours in general

upper secondary schools, lukio, and in vocational education and training, and arrangements for working

hours are decided locally. Similarly, providers of general upper secondary education and vocational

education and training may decide to purchase educational services, which means in practical terms that

general upper secondary schools, lukio, for instance, may purchase their religious instruction from the local

parish. In terms of basic education, the most significant change is the abolishment of the division of

comprehensive school, peruskoulu, into lower and upper stages. However, a comprehensive school place

E URYBAS E F I NL AND

20

will still be guaranteed to everyone, in accordance with the "local school principle. Local school principle

means that every child has a right to go to the nearest school to her/his place of residence.

Legislation governing universities took effect on 1 August 1998. The Universities Act (645/1997) and Decree

(115/1998) lay down provisions on issues such as the mission of universities, their research and instruction,

organisation and administration, staff and official language, students, appeals against decisions made by

universities and legal protection for students. Amendments to the Universities Act concerning, among other

things, the two-tier degree structure, came into force on 1 August 2005.

Legislation concerning academic degrees comprises the Decree on the System of Higher Education Degrees

(464/1998) and one national decree covering all educational fields. The decree stipulates, for example, the

objectives and scope of degrees, their general structure and content, as well as the distribution of

educational responsibility between different universities.

The Decree on the System of Higher Degrees also provides for the polytechnic degrees. The degree

programmes are confirmed by the Ministry of Education. The new Polytechnics Act (351/2003) and Decree

(352/2003), governing polytechnics, were approved in the spring of 2003. The legislation on polytechnics

defines, for example, the status, mission and administration of polytechnics. Further, the Ministry of

Education reformed the degree structure of polytechnics. The changes in the Polytechnics Act and Decree

came into force August 2005.

Under the new Universities Act, which was passed by Parliament in June 2009, Finnish universities are

independent corporations under public law or foundations under private law (Foundations Act). The

universities operate in their new form from 1 January 2010 onwards. Their operations are based on the

freedom of education and research and university autonomy. According to the new act the university can do

business which supports its basic mission to promote free research and scientific and artistic education,

provide higher education based on research, and educate students to serve their country and humanity.

Asetus korkeakoulututkintojen jrjestelmst

Basic Education Act

Polytechnics Act

Polytechnics Decree

Universities Act (2009)

Universities Decree

2.4. General Structure and Defining Moments in Educational

Guidance

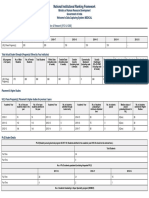

Organisation of the education system in Finland, 2009/10

E URYBAS E F I NL AND

21

4 1 0 2 3 5 6 7 8 9 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 10

PI VKOTI DAGHEM

3

ESI OPETUS

FRSKOLEUNDERVI SNI NG

PERUSOPETUS GRUNDLGGANDE UTBI LDNI NG

LUKI O GYMNASI UM

YLI OPI STO / KORKEAKOULU UNI VERSI TET / HGSKOLA

AMMATTI KORKEAKOULU YRKESHGSKOLA AMMATI LLI NEN KOULUTUS

YRKESUTBI LDNI NG

Pre-primary ISCED 0

(for which the Ministry of Education is not responsible)

Pre-primary ISCED 0

(for which the Ministry of Education is responsible)

Primary ISCED 1 Single structure

(no institutional distinction between ISCED 1 and 2)

Lower secondary general ISCED 2

(including pre-vocational)

Lower secondary vocational ISCED 2

Upper secondary general ISCED 3 Upper secondary vocational ISCED 3

Post-secondary non-tertiary ISCED 4