Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

1 PB

Transféré par

Tara WandhitaTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

1 PB

Transféré par

Tara WandhitaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Global J ournal of Health Science; Vol. 4, No.

5; 2012

ISSN 1916-9736 E-ISSN 1916-9744

Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education

140

Incidence of Birth Asphyxia as Seen in Central Hospital and GN

Childrens Clinic both in Warri Niger Delta of Nigeria: An Eight Year

Retrospective Review

G. I. Mcgil Ugwu

1

, H. O. Abedi

2

& E. N. Ugwu

3

1

Department of Paediatrics, Delta State University Teaching Hospital, Oghara, Nigeria

2

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Delta State University Teaching Hospital, Oghara, Nigeria

3

Chevron Hospital Warri, Nigeria

Correspondence: Dr. G. I. Mcgil Ugwu, Department of Paediatrics, Delta State University Teaching Hospital, P.

O. Box 3217, Warri, Delta State, Nigeria. E-mail: gnclinic@yahoo.com

Received: July 3, 2012 Accepted: July 17, 2012 Online Published: August 9, 2012

doi:10.5539/gjhs.v4n5p140 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/gjhs.v4n5p140

Abstract

Background: Birth asphyxia is one of the commonest causes of neonatal morbidity and mortality in developing

countries. Together with prematurity and neonatal sepsis, they account for over 80% of neonatal deaths.Aim: To

determine the incidence and mortality rate of birth asphyxia in Warri Niger Delta of Nigeria. Materials and

Method: Recovery of case notes of all the newborn babies seen from J anuary 2000 to December 2007 at Central

Hospital Warri and GN childrens Clinic, Warri, was undertaken. They were analyzed and those with birth

asphyxia were further analyzed, noting the causes, severity of asphyxia, sex of the babies, management given.

Results: A total of 864 out of 26,000 neonates seen within this period had birth asphyxia. 525 (28/1000 live

births) had mild asphyxia while 32% were severely asphyxiated. 61.5% of the asphyxiated were born at

maternities, churches or delivered by traditional birth attendants or at home. Prolonged labour was the

commonest cause of asphyxia and asphyxia was more in neonates from unbooked patients. Conclusion: The

incidence of bith asphyxia in Warri is 28/1000. Majority of patients are from prolonged labour and delivery at

unrecognized centres. Health education will dratically reduce the burden of asphyxia neanatorum as

unsubtanciated religous beliefs have done a great havoc.

Keywords: birth asphyxia, warri, Nigeria

1. Introduction

Birth asphyxia is a major cause of neonatal death especially in developing countries and is defined as the

inability of the newborn to initiate and sustain adequate respiration after delivery (Ezechukwu, Ugochukwu,

Egbuonu, & Chukwuka, 2004).

.

Of the 130 million infants born every year globally, about four million die in the

first four weeks of life- the newborn period (Iawn, Cousens, & Zupan, 2005). According to the World Health

Organization (WHO), between four and nine million newborns develop birth asphyxia each year. Of these, an

estimated 1.2 million die and at least same number develop severe consequences such as cerebral palsy, epilepsy

and developmental delay (The World Health Report, 2003). Historically, asphyxia was categorized into two

grades of severity namely asphyxia pallida or pale asphyxia and asphyxia livida, indicating the degree of

affliction. Infants with asphyxia pallida were generally regarded as severely affected, requiring immediate

resuscitation (Haider & Butta, 2006). However, this was replaced by a more objective measure such as Apgar

score by Dr Virginia Apgar (1953) an anesthesiologist in 1952.

However using apgar score alone has been found to be very unreliable especially in predicting outcome

(Leuthner & Ug, 2004). Controversies have continued even in the 21

St

century and Papile has commented on

apgar score in the 21

st

century (Papile, 2001). Birth asphyxia remains one of the commonest causes of new born

admissions in some centers (Butta 1990; Azam, Khan, & Malik, 2004; Ekwempu, Maine, Olvukobu, Esien, &

Kisseka, 1990). Some of the factors that influence the success of management of the illness include; the place of

birth, the level of prenatal care, the cause of the birth asphyxia, the gestational age of the neonate, maternal ill

health and events during pregnancy and delivery, the availability of resources, including the specialized

personnel to manage the disease (Madqbool, 1997). Many of the babies delivered outside the specialized centers

www.ccsenet.org/gjhs Global J ournal of Health Science Vol. 4, No. 5; 2012

141

for the treatment of these babies in the developing countries do not reach the centers on time as a result of

poverty and poor infrastructural development, so that by the time they arrive at these centers, complications have

already set in. There are also few of such centers in these countries which are not only under staffed but also are

relatively under equipped compared to the developed countries (Nguigi, 2009). Religious beliefs and ignorance

also play a major role in the occurrence of birth asphyxia and its complications (Hashima-E-Nasreen, 2009).

The Central Hospital in Warri and the GN childrens and General Medical clinic, one of the four major

childrens clinic in Warri, where this review was undertaken both serve about three local Government Areas in

Delta State of Nigeria with a combined population of two million three hundred and fifty persons, using the 2006

Nigerian census figures (Federal Republic of Nigeria Official Gazette, 2007).

The review was for a period of eight years, from J anuary 2000 to December 2007. Eight hundred and forty

babies with birth asphyxia were managed in these hospitals and the outcome will be discussed. These will

include the pattern of presentation, place of birth, the severity of the asphyxia, the possible causes and the

outcome of the management.

2. Materials and Method

The case notes of all the babies delivered in the hospitals and those neonates referred to the hospitals within the

period of review for any ailment including asphyxia neonatorum were retrieved and analyzed. The information

obtained included; place of birth, booked or unbooked, gestation age at delivery, mode of delivery, place of

prenatal care, events during pregnancy and delivery of the child, socio-economic status of the parents, including

the level of education of both parents. Other information obtained include the parity of the mother, the age of the

mother, the Apgar score of the baby if recorded, the method of resuscitation if where indicated, the gestational

age at birth, the sex of the child and the treatment given before referral, including the time interval between the

birth and referral of the child, presence of seizures, cyanosis, pallor, the level of consciousness on admission.

Other information obtained included the management instituted at the Central hospital and GN Children and

General Medical clinic, and the outcome.

Asphyxia was defined as Apgar score of less than 7 after five munites or baby did not cry immediately after birth

(Ibe, 1990). The severity was classified as mild, if the Apgar score at five minutes is 6-7 or required just

suctioning to establish a cry (Olowu & Azubuike, 1999). It is moderate if the five minute Apgar score is 4-5, or

required stimulation and oxygen administration before a cry and severe if the score is 0-3 and or required major

intervention or is associated with seizures central cyanosis or coma, or opisthotonic posture (Ibe, 1990; Olowu &

Azubuike, 1999).

Information on the follow up (including subspecialty follow ups) of these patients was documented, including

the duration of follow up. Deaths after discharge from the hospitals following birth asphyxia were not included

in this study.

3. Results

From the twenty six thousand four hundred and twenty thousand neonates delivered or referred to these

hospitals, eight hundred and forty had asphyxia, giving a rate of approximately twenty eight per one thousand

live birth (28/1000).

The yearly distribution of the incidence of aspyxia neonatorum is shown in table 1. This showed a steady decline

from 2005.

Table 1. Showing the yearly distribution

Year Number of Patients

2000 116

2001 107

2002 112

2003 108

2004 109

2005 102

2006 96

2007 90

Total 840

Five hundred males were seen, compared to three hundred and thirty four females, giving a ratio of 3:2

www.ccsenet.org/gjhs Global J ournal of Health Science Vol. 4, No. 5; 2012

142

Figure 1. Bar chart showing place of birth

Three hundred and thirty six, representing 40% of the asphyxiated babies were born in maternities and churches.

Infact 61.5% of the babies were born in the maternities, churches, traditional birth attendants or at home. About

2.5% or twenty one of the babies were born in transit (delivered on the way to the anticipated place of birth). The

mothers of five hundred and four babies did not book for antenatal care representing 60% of the asphyxiated

babies.

About 51% of the asphyxiated babies (which is four hundred and twenty nine) resulted from prolonged labour.

Antepatum haemorrahage accounted for 10% of the cases. Only 25 of the asphyxiated babies were premature

while multiple gestations accounted for 8%. Abnormal presentation including cord prolapse and cord prolapse

with fetal distress accounted for 8%. Other causes apart from prematurity include hypertension in pregnancy

which accounted for 12% of the cases, age of the mother, maternal pyrexia during the perinatal period, anaemia

in pregnancy and others. These are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Pie chart showing the causes of birth asphyxia

Prolonged Labour; 429

Antepatum Hemorrhage; 84

Abnormal Presentation/Cord

Compression/ Prolapse; Fetal distress; 66

Precipitate labour; 51

Multiple Gestation; 66

Prematurity; 25

Hypertension in Pregnancy; 17

Others: Mixed Causes, Maternal Pyrexia,

Maternal Anaemia young age etc.; 102

7.3

0

17.9

0

28.3

0

21.9

0

28.3

0

36

0

183.9

0

43.7

0

www.ccsenet.org/gjhs Global J ournal of Health Science Vol. 4, No. 5; 2012

143

324 had mild asphyxia which is 38.2% while 250 of these had severe birth asphyxia. These are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Showing the number of babies with various degrees of severities

Degree of Severity Number Percentage

Mild 321 38.2%

Moderate 269 32%

Severe 250 29.8%

Total 840 100%

The mortality rate was 27.3% which is two hundred and twenty nine patients. Of these, 52%, about one hundred

and nineteen had severe birth asphyxia. 43% of the deceased neonates had moderate asphyxia which translated to

ninety eight patients, while twelve of these had mild asphyxia which is 5%. One hundred and fifty three of the

deceased children were males and seventy six females, giving a ratio of 2:1.Mortality ratio as shown in table 3

was highest in neonates born in maternity/ churches. The least was from private hospitals with a percentage of

7.5%.

Table 3. Showing mortality ratios from various place of delivery

Place of Birth Number of Deaths Percentage

Maternity/Churches 125 54.5%

TBA/Home 46 20%

Government Hospital 23 10%

Private Clinics 17 7.5

In Transit 18 8%

Total 229 100%

TBA =Traditional Birth Attendant

4. Discussion

Birth asphyxia remains a leading cause of neonatal morbidity and mortality in Nigeria.

1

A study by Okolo and

Omene (1985) in Benin City showed that neonatal mortality dropped from 49/1000 live births to 16.9/1000 from

the 1970s to 1981 just by the reduction of birth asphyxia in term neonates (Okolo & Omene, 1985). WHOs fact

sheath (2006) shows that it is a major cause of under- 5 mortality (Mortality Fact Sheath, 2006). A study (2010)

in Warri Niger Delta between 2000 and 2007 in the same hospitals showed that the incidence of birth asphyxia

was higher than prematurity within the same period (840 for birth asphyxia and 639 for prematurity) (Ugwu,

2010).

The incidence of 28/1000 live births in our study is slightly more than Airedes experience of 26.5/1000 live

births from Fox University, Nigeria (1991) (Airede, 1991) and another study in Nigeria and Central Africa

(1993) with incidence of 26/1000 (Kinoti, 1993). Its much higher than the incidence of 4.6/1000 in Cape town

(Hall Dr. Smith, 1996), and a far cry from what obtains in developed countries at less than 0.1/1000 (Badawi et

al., 1998). On the other hand, it is much lower than the hospital incidence of 93.7/1000 at Wesley hospital in

Ilesha Nigeria (Ogunlesi & Oseni, 2008). Even at the same centers, the incidence varied at different periods.

While Okolo and Omene (1985) noted a decrease between the 1970s and the 1980s, Ogunlesi and colleague

infact noted an increase when 1994 to 1998 was compared to 1999 and 2003 (93.7/1000 vs. 102/1000

respectively). The marked difference may be in the study design. While Ogunlesi and Oseni (2008) used

admitted sick babies as the denominator, we used all newborns seen in our hospitals within the study period.

Moreover, criteria for diagnosing asphyxia may vary in both studies. According to the American Academy of

Pediatrics and American College of Obstetrics, a neonate is labeled to be asphyxiated if the following conditions

are satisfied. (a) umbilical cord arterial pH less than 7 (b) Apgar score of 0-3 for longer than 5minutes, (c)

neonatal neurological manifestations such as seizures, coma, hypotonia and (d) multisystem organ dysfunction

such as cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, hematological, pulmonary and renal functions (Committee on Fetus and

www.ccsenet.org/gjhs Global J ournal of Health Science Vol. 4, No. 5; 2012

144

Newborn, 1996); American Academy of Pediatrics and American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (2002).

Following this strict definition will certainly reduce its incidence.

There was also no significant difference in the yearly distribution in Airedis study which was carried out over

three consecutive years (Airede, 1991). Our study showed a similar experience.

The incidence was higher in males probably because of females resistance to diseases as a result of their XX

chromosomes, X being the site of immunoglobulin production, giving them double protection (Susan & Clark,

2009). Birth asphyxia is an index of obstetric care (Haider, Butta, 2006). In general, a study has shown that, 50%

of causes of birth asphyxia is Antepatum, 40% intrapatum, with 10% due to postpartum causes (Dilenge,

Majnemer, & Shevell, 2001). Our study shows that it was commoner in unbooked than booked patients, which is

similar to the experience of Owolabi and collegues (2008) and in Ilesha, and Etuk in Calabar (Etuk, Etuk, Ekoh,

& Udoma, 2000).

Our study also showed that the major cause of asphyxia Neonatorum is prolonged labour, which is same result in

other center (Shireeni, Nahar, & Mollah, 2009). The incidence and mortality was commoner in babies delivered

in maternities and churches and this is the same experience at Wesley hospital in Ilesha (Ogunlesi & Oseni,

2008). The reason is because of ignorance and traditional belief. When a woman is offered a caesarian section

due to feto-pelvic disproportion by an obstetrician, she goes to a maternity where she is assured of delivery

without operation. Also delivery in churches is believed to offer protection. Feto-pelvic disproportion as in our

study is known to cause birth asphyxia (Leclerg, Shretsha, & Christine, 2009). In contrast to the Iesha study

however, neonates delivered in private hospital had the least presentation as birth asphyxia (Ogunlesi & Oseni,

2008). This may reflect the level of care given by the pravite practioners at various localities. Our study also

showed that mal-presentation is a major cause of this illness. On the whole, while Antepatum problems

especially with the fetus are more likely to be the cause in developed countries (McIntosh, 2008), intrapatum

problems are likely to be responsible in developing countries (Ellis & de L Costello, 1999; Ellis, Mananadhar,

Mahudi, & Costella, 2000). These are majorly preventable, but occur because of lack of manpower, equipments

and poor infrastructural development (Ellis, Mananadhar, Mahudi, & Costella, 2000). These are also our

experience in this study.

Mortality rate in those with severe birth asphyxia was also similar with other studies (Anochie & Eke, 2005;

Hankins & Speer, 2003; Wammanda, Onalo, & Adama, 2007). In fact, WHO in its article Countdown To 2015:

Nigeria: maternal, newborn and child survival indicates that birth asphyxia accounts for 29% of deaths with

infections accounting for 26%(Ogunlesi, Ogundeyi, Ogunfoware, & Olowu, 2008).

5. Conclusion

Birth asphyxia remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in developing countries, not only neonatal

mortality but under five mortality. It is also a major setback in achievement of the 4

TH

millennium goal. This is a

major reflection of the obstetric care in the countries. Ignorance and poverty of the populace are other major

reasons for birth asphyxia. Prof Babatunde Oshotumihien of Nigera as the minister of health tried to implement a

policy where midwives will be posted to rural areas with an incentive of earning triple the salary of their

contemporaries in the urban areas (Olusanya & Okolo, 2006). This would have helped to reduce the incidence of

birth asphyxia. However a greater impact in the reduction of this preventable illness lies on the provision of basic

infrastructures by the government and increase in the budget for health as recommended by World Health

Organization (WHO). A propective study of the incidence and complications of birth asphyxia is currently being

undertaken in these centres, so as to compare with this study and also obtain true prevalence as some of these

patients are lost to follow up.

Acknoledgement

I acknowledge most sincerely the contributions of Drs Chukwu Uche, Chukwuemeka Moforn and Akpos for

their tremendous help.

References

Airede, A. I. (1991). Birth Asphyxia and Hypoxic-ischemic Encephalopathy: Incidence and Severity. Ann Trop

Paediatr, 11(4), 331-335.

American Academy of Pediatrics and American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Guidelines for perinatal

care. Giltrap LC, Oh W, editors. Elk Grove Village (IL): America Academic of Pediatrics; 2002. P196-197

Anochie, I. C., Eke, F. U. (2005). Acute Renal Failure in Nigerian Children: Port Harcourt Experience. Pediatric

Nephrology, 20(11), 1610-1614. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00467-005-1984-8

www.ccsenet.org/gjhs Global J ournal of Health Science Vol. 4, No. 5; 2012

145

Apgar, V. (1953). Proposal for a New Method of Evaluation of the Newborn Infant. Curr Res Anaesthesia and

Analgesia, (4), 260-267.

Azam, M., Khan, P. A., & Malik, F. A. (2004). Birth Asphyxia: Risk Factors. The Professional, 11(4), 416-423.

Badawi. N., Kurinezuk, J . J ., Keogh, J . M., Alessandri, L. M., OSullivan. F., Barton, P. R. (1998). Intrapatum

Risk Factors for Newborn Encephalopathy: The Western Australian Case-Control Study. BMJ, 317(172),

1554-1558. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.317.7172.1554

Butta, Z. A. (1990). Neonatal Care in Pakistan: Current Studies and Prospects of the Future. Journal Pak Paed

Assoc, 4, 11-22.

Committee on Fetus and Newborn. (1996). American Academy of Pediatrics and Committee on Obstetric

Practice, America College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Use and Abuse of the Apgar Score. Pediatrics, 98,

141-142.

Dilenge, M. E., Majnemer, A., & Shevell, M. I. (2001). Long Term Developmental Outcome of Asphyxiated

Term Neonates. J Child Neurol, 102, 628-636.

Ekwempu, C. C., Maine, D., Olvukobu, M. P., Esien, E. S., & Kisseka, M. N. (1990). Structural Adjustment and

Health Care in Africa. Lancet, 336, 56-57. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0140-6736(90)91573-S

Ellis, M., & de L Costello M., (1999). Antepatum Risk Factors for Newborn Encephalopathy. Intrapatum Risk

Factors are Important in Developing World. BMJ, 318, 1414. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.318.7195.1414

Ellis, M., Mananadhar, N., Mahudi, D. S., & Costella, M., (2000). Risk for Neonatal Encephalopathy in

Kathmandu, Nepal, a Developing Country: Unmatched Case-control Study. BMJ, 320, 1229-1236.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7244.1229

Etuk, S. J ., Etuk, I. S., Ekoh, M. I., & Udoma, E. J . (2000). Prenatal Outcome in Pregnancies Booked for

Antenatal Care but Delivered Outside Health Facilities in Calabar, Nigeria. Acta Trop, 75, 29-33.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0001-706X(99)00088-1

Ezechukwu, C. C., Ugochukwu, E. F., Egbuonu, I., & Chukwuka, J . O. (2004). Risk Factors for Neonatal

Mortality in a Regional Tertiary Hospital in Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice, 7, 50-55.

Federal Republic of Nigeria Official Gazette (2007). Vol. 94(4):B47-53.

Haider, B. A., & Butta, Z. A. (2006). Birth Asphyxia in Developing Countries: Current Status and Public Health

Implications. Curr. Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care, 178-188.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cppeds.2005.11.002

Hall Dr. Smith J . (1996). Maternal Factors Contributing to Asphyxia Neonatorum. J Trop. Pediatr, 42, 192-19.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/tropej/42.4.192

Hankins, G. D., & Speer, M. (2003). Defining the Pathogenesis and Neonatal Encephalopaphy and Cerebral

Palsy. Obstel Gynecol, 102, 628-636. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0029-7844(03)00574-X

Hashima-E-Nasreen. (2009). Maternal, Neonatal and Child Health in Selected Northern Bangladesh. Bangladesh

Research and Evaluation Commission. Retrieved from http://www.bracresearch.org/reports/MNCH_base

line_2008_new.pdf

Iawn, J . E., Cousens, S., & Zupan, J . (2005). 4 Million Deaths. When? Where? Why? Lancet, 365(9462),

891-900. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71048-5

Ibe, B. C. (1990). Birth Asphyxia and Apgar Scoring: A Review. Nigerian Med Practitioner, 20, 111-113.

Kinoti, S. N. (1993). Asphyxia of the Newborn in the East, Central and Southern Africa. East Afri Med J., 70,

422-433.

Leclerg, C. B., Shretsha, S. R., Christine, P. (2009). Materno-Fetal Disproportion and Birth Asphyxia in Rural

Sarlahi, Nepal. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med, 16(7), 616-62.

Leuthner, S. R., Ug. D. (2004). Low Apgar Score and the Definition of Birth Asphyxia. Pediatr Clin N Am; 51:

737-745. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2004.01.016

Madqbool S. (1997). Birth Asphyxia: In Hand of Neonatal Care. 4

th

Ed. 515-532.

McIntosh N. (2008). The Newborn In: McIntosh, N., Helms, P. J ., Smyth, L. R. Editors. Forfar and Arneils

Textbook of Paediatrcs 7

TH

Edition, New York: Churchill Livingstone, p. 117-392.

www.ccsenet.org/gjhs Global J ournal of Health Science Vol. 4, No. 5; 2012

146

Mortality Fact Sheath. (2006). Under -5 Mortality in Nigeria: Age Specific Mortality Rates: DHS1990, 1999,

2003. World Health Organization Statistics.

Nguigi, W. E. The Standard of Kenya. Retrieved from http://www.easterndard.net/InsidePage.php?id=1144007

581&cid=4

Ogunlesi, T. A., & Oseni, S. B. A. (2008). Severe Birth Asphyxia in Wesley Guild Ilesha- A Persistent Plague.

Nig Med Pract, 53(3), 40-43. http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/nmp.v53i3.28928

Ogunlesi, T., Ogundeyi, M., Ogunfoware, O., & Olowu, A. (2008). Socio-clinical Issues in Cerebral Palsy in

Sagamu Nigeria. South African J Child Health, 2(3), 120-124.

Okolo, A. A., Omene, J . A. (1985). Trends in Neonatal Mortality in Benin. International Journal of

Gynaecology and Obstetrics, 23(30), 191-195. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0020-7292(85)90103-1

Olowu, J . A., & Azubuike, J . C. (1999). Assessment and Care of the Newborn Infant: Paediatrics and Child

Health in a Tropical Region. Azubuike and Nkanginieme Eds. African Educational Series, 38-43.

Olusanya, B. O., & Okolo, A. A. (2006). Causes of Hearing Impairment in Inner City, Lagos. Paediatric and

Perinatology Epidemiology, 20(5), 366-371. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3016.2006.00733.x

Owolabi, A. T., Fatasi, A. O., Kuti, O., Adeyemi, A., Faluroti, S. O., & Obiajuwa, P. O. (2008). Booked and

Unbooked Patients in Wesley Hospital in Ilesha. Singapore Med Journal, 49(7), 562-531.

Papile, L. A., (2001). The Apgar Score in the 21

st

Century. N Engl J Med, 344(519-520).

Shireeni, N., Nahar, N., & Mollah A. (2009). Risk Factors and Short Out-come of Birth Asphyxiated Babies in

Dhaka Medical College Hospital. Bangladesh J Child Health, 33(3), 83-89.

Susan Furdon, & Clark, D. A. (2009). E-medicine. Retrieved fromhttp://emedicine.com/article/975909-overview.June2009

The World Health Report (2003). Shaping the Future, Geneva.

Ugwu, G.I.M (2010). Prematurity in Central Hospital and GN Childrens Clinic in Warri Niger Delta. Nigerian

Journal of Medicine, 51(1), 10-13.

Wammanda, R. D., Onalo, R., & Adama, S. J . (2007). Pattern of Neurological Disorder Presenting at a

Paediatric Neurological Clinic in Nigeria. Ann Afri Med, 6, 73-75.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/1596-3519.55712

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5795)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1091)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Ce Mark - Application FormDocument3 pagesCe Mark - Application Formrajivsinghal90Pas encore d'évaluation

- CHAPTER 8 f4 KSSMDocument19 pagesCHAPTER 8 f4 KSSMEtty Saad0% (1)

- Hyponatremia in Brain InjuryDocument11 pagesHyponatremia in Brain InjuryTara WandhitaPas encore d'évaluation

- New Osteo Peros Is GuidelinesDocument20 pagesNew Osteo Peros Is GuidelinesTara WandhitaPas encore d'évaluation

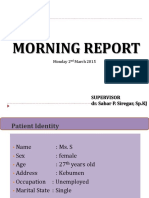

- Morning Report: Supervisor Dr. Sabar P. Siregar, SP - KJDocument49 pagesMorning Report: Supervisor Dr. Sabar P. Siregar, SP - KJTara WandhitaPas encore d'évaluation

- Oxalate Intake and The Risk For Nephrolithiasis: Clinical ResearchDocument7 pagesOxalate Intake and The Risk For Nephrolithiasis: Clinical ResearchTara WandhitaPas encore d'évaluation

- Ticagrelor Versus Aspirin in Acute Stroke or Transient Ischemic AttackDocument9 pagesTicagrelor Versus Aspirin in Acute Stroke or Transient Ischemic AttackTara WandhitaPas encore d'évaluation

- Schizophr Bull 2011 Simonsen 73 83Document11 pagesSchizophr Bull 2011 Simonsen 73 83Tara WandhitaPas encore d'évaluation

- Schizophr Bull 2011 Chan 177 88Document12 pagesSchizophr Bull 2011 Chan 177 88Tara WandhitaPas encore d'évaluation

- Company Catalogue 1214332018Document40 pagesCompany Catalogue 1214332018Carlos FrancoPas encore d'évaluation

- RCMaDocument18 pagesRCMaAnonymous ffje1rpaPas encore d'évaluation

- Guimbungan, Core Competency Module 1 - Part 3 PDFDocument11 pagesGuimbungan, Core Competency Module 1 - Part 3 PDFSharlyne K. GuimbunganPas encore d'évaluation

- Minerals and Resources of IndiaDocument11 pagesMinerals and Resources of Indiapartha100% (1)

- W01 M58 6984Document30 pagesW01 M58 6984MROstop.comPas encore d'évaluation

- Uni of Glasgow Map PDFDocument1 pageUni of Glasgow Map PDFJiaying SimPas encore d'évaluation

- Silage Sampling and AnalysisDocument5 pagesSilage Sampling and AnalysisG_ASantosPas encore d'évaluation

- City of Atlanta - Structural Checklist: All Items Listed Herein Shall Be Complied With If Applicable To The ProjectDocument16 pagesCity of Atlanta - Structural Checklist: All Items Listed Herein Shall Be Complied With If Applicable To The ProjectSandip SurPas encore d'évaluation

- Natu Es Dsmepa 1ST - 2ND QuarterDocument38 pagesNatu Es Dsmepa 1ST - 2ND QuarterSenen AtienzaPas encore d'évaluation

- Ethics, Privacy, and Security: Lesson 14Document16 pagesEthics, Privacy, and Security: Lesson 14Jennifer Ledesma-Pido100% (1)

- Stanford-Binet Test Scoring Explained - Stanford-Binet IQ TestDocument3 pagesStanford-Binet Test Scoring Explained - Stanford-Binet IQ TestLM R50% (2)

- 1 A Finalexam FNH330 June 2015 Final Review QuestionsDocument6 pages1 A Finalexam FNH330 June 2015 Final Review QuestionsChinley HinacayPas encore d'évaluation

- Course Weekly Schedule Health Science TheoryDocument6 pagesCourse Weekly Schedule Health Science Theoryapi-466810096Pas encore d'évaluation

- Geometry of N-BenzylideneanilineDocument5 pagesGeometry of N-BenzylideneanilineTheo DianiarikaPas encore d'évaluation

- Occlusal Appliance TherapyDocument14 pagesOcclusal Appliance TherapyNam BuiPas encore d'évaluation

- This Is No Way To Treat An Aorta.: Edwards EZ Glide Aortic CannulaDocument5 pagesThis Is No Way To Treat An Aorta.: Edwards EZ Glide Aortic CannulaAhmadPas encore d'évaluation

- Risk Appetite PresentationDocument10 pagesRisk Appetite PresentationAntonyPas encore d'évaluation

- An Assignment On "Mycology Laboratory Technique"Document1 pageAn Assignment On "Mycology Laboratory Technique"BsksvdndkskPas encore d'évaluation

- Sikadur 42 HSDocument2 pagesSikadur 42 HSthe pilotPas encore d'évaluation

- Qualitative Tests Organic NotesDocument5 pagesQualitative Tests Organic NotesAdorned. pearlPas encore d'évaluation

- Ancamine Teta UsDocument2 pagesAncamine Teta UssimphiwePas encore d'évaluation

- Electronic Price List June 2022Document55 pagesElectronic Price List June 2022MOGES ABERAPas encore d'évaluation

- The Lion and The AntDocument4 pagesThe Lion and The AntDebby Jean ChavezPas encore d'évaluation

- Distilled Witch Hazel AVF-SP DWH0003 - June13 - 0Document1 pageDistilled Witch Hazel AVF-SP DWH0003 - June13 - 0RnD Roi SuryaPas encore d'évaluation

- 2 - Pizeo Electric SensorDocument33 pages2 - Pizeo Electric SensorNesamaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Broucher Design - 02Document8 pagesBroucher Design - 02ಉಮೇಶ ಸಿ. ಹುಕ್ಕೇರಿ ಹುಕ್ಕೇರಿPas encore d'évaluation

- EBANX Beyond Borders 2020Document71 pagesEBANX Beyond Borders 2020Fernanda MelloPas encore d'évaluation

- MINUZA Laptop Scheme Programs ThyDocument9 pagesMINUZA Laptop Scheme Programs Thyanualithe kamalizaPas encore d'évaluation