Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Why The Sky Is Blue

Transféré par

Travis Wood0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

12 vues11 pagesraman effect

Titre original

WHY THE SKY IS BLUE

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

DOC, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentraman effect

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme DOC, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

12 vues11 pagesWhy The Sky Is Blue

Transféré par

Travis Woodraman effect

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme DOC, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 11

WHY THE SKY IS BLUE?

When I was asked to choose a scientific subject for my lecture I had no

difficulty at all in choosing the subject of "Why the sky is blue." Fortunately,

nature has been kind today; as I look up and see, the sky is blue: not

eerywhere, as there are many clouds. I chose this subject for the simple

reason that this is an e!ample of something you do not hae to go to the

laboratory to see. "ust look up look at the sky. #nd I think it is also an

e!ample of the spirit of science. $ou learn science by keeping your eyes and

ears open and looking around at this world. %he real inspiration of science,

at least to me, has been essentially the loe of nature. &eally, in this world,

whereer we see, we see all kind of miracles happening in nature. %o me,

eerything I see is something incredible something absolutely incredible. We

take it all for granted. 'ut I think the essence of the scientific spirit is to look

behind and beyond and to reali(e what a wonderful world it is that we lie

in. #nd eerything that we see presents to us not a subject for curiosity, but a

challenge, a challenge to the spirit of man to try to understand something of

this ast mystery that surrounds us.

)cience continually attempts to meet this challenge to the spirit of man. #nd

the great problem today, which *r. )arabhai has addressed himself to, is

how to rouse the younger generation of our country to meet this great

challenge before us, once again to build up India into a great center of

knowledge and learning and endeaor. Well, I wish you all success. +ow let

me turn back to my problem "Why the sky is blue,"

I raised this -uestion because it is an easy subject. I only hae to look up and

see that the sky is blue. 'ut why is it blue,

%he interesting point is that it is easy to answer that -uestion in a casual

way. If you ask a 'otanist, why are leaes green, .e murmurs,

/0hlorophyll/. Finished. $ou see all scientific -uestions can be disposed of in

that summary fashion, in one or two words. $ou can surely pass your

e!aminations with that kind of answer, but that is not the real answer. #s I

said before, the scientific challenge of nature is to think not only to discoer

but also to think, to think continually and to try to penetrate this mystery:

"Why is it blue," %hat is a ery interesting problem, because two things are

there. %he sky is there and I am here. I see it is blue. It is the human brain

and the human mind as well that are inoled in this problem. +ow suppose

we put this problem before the young people. *on/t read any book about it;

don/t ask your teacher. 1et us sit dawn and try to think out this problem:

Why is the sky blue, 1ook at it as if it is a completely new scientific

problem about which nobody has troubled himself before. $ou sit down and

think it out and you will find it a most e!citing thing to ask yourself that

-uestion and see if you can discoer the answer for yourself. +ow I will put

it to you in this way. %he best way to answer a -uestion is to ask another. #t

night, we all see the stars. 2n a fairly clear night you see the stars twinkling

in the sky. Why are the stars not isible in daytime, 3lease ask yourself this

modest -uestion. Well, the reason obiously is that the earth, as a lady, has

hidden herself under a eil. %he sky is a eil, which she has thrown around

us. We cannot see the stars during the day, because the eil hides the stars.

#nd what is this eil, %he eil obiously is the atmosphere of the earth. %he

same eil, which at night is so transparent that we can see the faintest star

and the 4ilky Way, is coered up in daytime. 2biously, it is the

atmosphere, which is the eil. #nd we see the sky as blue only because we

hae not got other thicker eils like these clouds. $ou see for e!ample, those

clouds high in the blue sky. 2biously therefore, for the sky to be really

blue, there must be nothing else, no clouds and perhaps no dust. %he clearer

the sky is, the bluer it is. )o the sky is not always blue; it is sometimes blue

and sometimes not blue at all. )o that the mere looking at the sky enables us

to understand the condition of the atmosphere.

1et me say one thing more. 2biously, the sky and the atmosphere are lit up

by the sunlight. )unlight is passing through this great column of air and

obiously it is the atmosphere, something that is transparent and inisible at

night, that is seen to us by the light 5 sunlight 5 passing through the

atmosphere. +ow I want you to ask yourself another -uestion. I don/t know

if any of you hae had the curiosity to look at the clear sky on a full5moon

night. $ou know that moonlight is only the sunlight incident on the moon

and is diffused or reflected. I don/t know if any of you hae really watched

the sky on a clear full5moon night. $ou will be astonished to find that the

sky is not blue. It appears pale, you just see some light and you see some of

the stars een under the full5moon sky, but the sky is not blue. Why is it that

the sky, which appears blue in sunlight, does not appear blue in moonlight,

%he answer obiously is 5 the illumination is far less powerful. $ou don/t

re-uire to be much of a mathematician to calculate the ratio of the intensities

of full5 moon light and sunlight. I present it to same young mathematician to

sit down and work out. .ow big is the moon, What should be the brightness

of moonlight, It is a little astronomical problem. &ough arithmetic would

tell you that moonlight is something like half a millionth part as bright as

sunlight; you would think it is terribly small. 'ut moonlight, when it is there

seems ery bright though it is only half a millionth part of the brightness of

sunlight. Why does it look so bright, Well, the eyes hae got accustomed to

much lower leels of illumination. )o moonlight appears ery bright but not

so bright, as to eil all the stars. 'ut the sky, it does not appear blue. )o this

comparison of sunlight and moonlight brings to our notice a ery remarkable

fact. It is an absolutely fundamental aspect of human ision that to perceie

colour, you must hae a high leel of illumination. %he sky is blue, merely

because sunlight is brilliant: moonlight is much less brilliant and so you

don/t perceie colour. %his is a principle, which perhaps is not so widely

appreciated as it ought to be. 0olour is only perceied at high leels of

illumination. %he higher the illumination the brighter are the colours. $ou go

down to low leels of illumination, say, a millionth part, half a millionth or a

hundred thousandth part of sunlight, the sense of colour disappears. +ow

this is a ery fundamental fact of human ision, which simply comes out of

nothing else but just obseration and thinking, that/s all. I can go on giing

any number of illustrations. 3erhaps the most striking illustration emerges

when you look at the stars or such objects as the 2rion nebula through small

telescopes. 1et me say here and now, my belief that there is no science so

grand, so eleating, so intensely interesting as astronomy. It is ama(ing to

see how many people high up hae neer seen the sky through the telescope.

I want to tell them something which is absolutely incredible: +othing more

than a pair of binoculars, a good pair of binoculars is needed to educate

oneself in the facts of astronomy I think a man who does not look at the sky

een through that modest e-uipment 5 a pair of binoculars 5 cannot be called

an educated person, because he has missed the most wonderful thing and

that is the unierse in which he lies. $ou must hae a look at it. $ou don/t

see much of it, but you see a little and een this little is enough to eleate the

human soul and make us reali(e what a wonderful thing this world is.

I come back now to the problem of the blue sky. I want to pose to you a ery

difficult -uestion. Why is it that we perceie the blue colour only under

intense illumination in sunlight, and not in moonlight, I will bypass that and

come back to the -uestion: Why is the sky blue, Well, we all know that

white light is composed of all the colours in the spectrum. $ou diide white

light into arious colours; you start with deep red at one end, light red,

orange, yellow, green, blue and iolet, so on, the whole range of colours.

When I look up at the sky, I see only the blue; what has happened to the rest

of the spectrum, %his is the basic -uestion. %he -uestion becomes a ery

pressing one when I remark that when we actually spread out sunlight into a

spectrum, the blue part of it is the least intense part. 1ess than 6789th of the

whole energy of the brightness of the sunlight appears in the blue of the

spectrum and we see only that 6789

th

part. $ou don/t see the rest of the

spectrum. It has simply anished. It is not there at all. $ou can look ery

ery hard and try to see if you can see any red or yellow or green in blue sky.

We don/t see it. %he blue has just masked the rest of the spectrum. %his is a

ery remarkable fact. If you watch the sky on some occasions, you get great

masses of white clouds, what they call the cumulus clouds not huge things,

just little bunches. It is a beautiful sight to see the blue sky and these little

masses soaring aboe. I hae deried great satisfaction in just doing nothing

at all and looking at these masses of clouds and the blue sky. %he interesting

point is precisely when you hae the clouds moing about that the sky is

bluest. What it means is that these cumulus clouds in the course of their

formation just cleaned up the rest of the atmosphere. %hey take up the dust

particles and concentrate them on the white clouds. %he rest is left nice and

clean. $ou see the beautiful blue iew against the brilliant white; it is a ery

loely sight. # sight for the :ods; only you don/t bother to look at it because

it is so common. $ou may ask me, how is the cleaning process

accomplished, +ow here is a wonderful story. When I ask the young people,

"What is the cloud," ;2h< )ir, it is steam". %he usual answer you get is that

the cloud is steam, but it is nothing of the sort. %he cloud consists of

particles and what looks to us, as great masses of white clouds are just

droplets of water. Water is heay but why does it not fall down, We find it

floating in the air< $ou see that is another problem. #lready I am going from

one problem to another. We ask ourseles, what is a cloud, Why is it

floating in the air, %he moment you ask the -uestion, //Why the sky is blue,"

you go deeper and deeper into some of the deepest problems of 3hysics.

+ow the interesting point is this you cannot hae a cloud unless you hae

dust particles about which it can form.

%here must be particles of some sort, may be ery small, maybe ery large.

%hey call it in learned language /+uclei/. If there is no dust in the air, there

will be no cloud and no rain. $ou see how from the blue sky, we hae got on

to the origin of rain, rainfall and so on. 2ne thing leads to another. %hat is

the essence of science. $ou must go deeper where it leads you. $ou cannot

go thus far and no further. %he moment you raise a -uestion, another

-uestion arises, then another -uestion, so on and so on. =ltimately, you find

that you hae to trael the whole field of science before you get the answer

to the -uestion: Why the sky is blue, )o I told you this fact about the clouds.

Well, I should say the clouds clean up the atmosphere. 0louds form and then

leae the atmosphere clean, comparatiely free from dust particles and other

nuclei and that is why the sky is blue. )o we came down at last to getting

some kind of answer to the problem. %he sky is blue because the atmosphere

is clean and free from dust and all nuclei. %he clearer it is, the bluer it looks,

proided there is enough light. )o you come somewhere near the answer to

the -uestion. What is it you are able to see, %he fact is that when we see a

blue sky, we see the atmosphere of the earth, the gases of the atmosphere,

they diffuse the light and we see the blue light of the sky. 'ut still we are far

from the answer.

I told you that blue is only 6789th part of the sunlight. What happens to the

rest of the light, the sunlight, %hat is the -uestion. +ow this -uestion can be

answered in the following fashion. $ou look at the white cloud and look at

the blue sky. $ou can compare them with the help of a pocket spectroscope

and you find strangely enough that you hae to look ery5ery carefully

before you find any difference in the spectrum of the blue sky and the

spectrum of the white cloud. White cloud is certainly ery much brighter.

'ut so far as the spectrum is concerned, you see in the blue sky and in the

cloud the same spectrum. It also starts with the red end and goes on till the

blue. 'ut in one case you see the blue, in the other case you see the white.

#nd with great trouble, you look ery carefully; you see that there is some

difference in the relatie brightness. $ou can see the yellow and the red, not

so bright relatiely. 4ind you, it is a mental calculation. $ou see the relation

of brightness between the blue part of the sky, the blue part of the spectrum

and the iolet part and the rest of the spectrum. &elatiely to the red, the

yellow and the green, the blue and iolet are stronger in the scattered light in

the diffused light of the blue sky. )till you are ery far from the answer. It

does not e!plain why don/t we see the rest of the spectrum. #ctually in the

blue sky the green and the yellow and the red are still there, they are still far

brighter, perhaps not so perhaps not 89 limes but perhaps ten times brighter

than the blue. %hen why do we see the blue and why don/t we see the rest,

.ere again you come across an e!tremely difficult -uestion to answer. %he

actual brightness of the blue part of the spectrum in skylight is still much

smaller than the brightness of the rest of the spectrum but we don/t perceie

that part of the spectrum. +ow this is ery simple and ery surprising. 'ut

there is a nice little e!periment which, perhaps one day, will be shown at the

)cience 0enter which will enable you to see at least that it is not an

e!ceptional phenomenon. It is one of the most fundamental facts of human

ision that the blue part of the spectrum inspite of its weakness dominates

the spectrum in certain conditions and plays a role tremendously far more

important that its actual brightness warrants. +ow the e!periment is the

following it is a ery easy e!periment. $ou take water and put a little copper

sulphate in it and then put e!cess ammonia in it. $ou will get a solution

called cuprammonium. It is ery strong it will transmit only deep iolet

light. 3ut it in a cell. $ou go on adding water in the cell and look at the

colour of the bright lamp and see that the following thing happens. %he deep

iolet changes into blue. %he blue changes to a lighter blue and so on. 'ut

till the ery last, it remains blue. In the spectrum of the light the solution is

transmitting red light, green light, not of course yellow. 1ot of light comes

through the spectrum and the blue is still only a minor part of the whole.

Whateer light comes through the spectrum you cannot see and you cannot

een imagine any other colour coming through. #nd the reason for it is as

follows. If you e!amine the transmitted light through a spectroscope you

will find that the yellow part of the spectrum is diminished by the influence

of cuprammonium. It absorbs and cuts out the small part of the width of the

spectrum, but a ery important part and that ery important part is the

yellow of the spectrum.

+eer mind how it absorbs the yellow part and controls the colour. %he light

is blue simply because the yellow is absorbed and the blue comes into

ision. If you take the whole spectrum and if you reduce the strength of the

yellow part of the spectrum, at once you find the blue part of the spectrum

and the blue colour dominates. %his is again a fact of physiology. If you

want any colour whatsoeer to be showy, you must take out the yellow. %ake

for e!ample that red carpet which has been spread in my honor, I suppose.

$ou look at it through a spectroscope. I can tell you beforehand, there will

be no yellow in it at all. %o get any colour, red, green or blue, you must take

out the yellow.

$ellow is the deadly enemy of colour. #ll other colours I mean. 1ook at the

green leaf. #ll the leaes are green, not because of the presence of

chlorophyll 5 the chlorophyll has a strong absorption of red no doubt. 'ut

the real factor, which makes the color green, is the fact that the yellow is

taken off chlorophyll has enough absorption of the yellow to reduce the

strength of yellow. Well, I e!amined silks for this. 'angalore is a great place

for silk manufacture. I managed to purchase about >?5@9 blouse pieces. I got

them to erify the proposition that all brilliant colours re-uire the

suppression of the yellow region of the spectrum. 1ook at the rice field. It is

wonderful.

1ook at the rice field with a spectroscope.

It looks ery much like the spectrum of the blue sky. 'ut the only isible

difference you can actually see at a glance between the blue sky and the

green rice field is that the blue part of the spectrum has been cut off and that

is produced by the so5called carotenoid pigments that are present here,

which cut off the blue; the rest of the spectrum looks almost alike. 'ut if you

look ery carefully, you will see that in the colour of the rice field, you do

not get the yellow. %he remoal of yellow is essential, before you can

perceie the leaes as green. $ou see always this predominance of the

yellow. 2n the contrary, if the yellow is taken off, the blue dominates. If you

don/t take off the yellow, the yellow dominates. %he two are contradictory

and they are enemies to each other. %he fact is that you can diide 55 the

physical e!planation is deeper still 5 you can diide the whole spectrum into

two pelts. %he diision is just where green the blue ends: that part of the

spectrum e!tending to green, yellow, orange and red amounts only to yellow.

%he other parts of the spectrum summed up amount to blue. +ow if you take

off this or reduce this you get the other. %his is the real e!planation of the

blue colour of the sky and is ery significant. $ou reduce 55 not that you

abolish 55 the intensity of the yellow in the spectrum and of course of the

green and the red. It is the reduction of the yellow of the spectrum that is to

say the predominance of the blue, which is responsible for the blue light of

the sky. Well, one can carry further and say that it is the reduction of yellow

that is basic. #nd why is it reduced, )o here comes the second part of it. I

could hae started with that and said, "Why is the sky blue," ;2h, the

scattering of light by the molecules of the atmosphere". I could hae

dismissed the whole lecture in one sentence. I could hae said just as the

botanist says "Why is it green," ""ust chlorophyll". I could hae said, "Why

is the sky blue," ")cattering of light by the molecules of the atmosphere."

2ne sentence, "%hen sir" you would ask me, ;why this entire lecturerA.

'ecause, my young friends, I want you to reali(e that the spirit of science is

not finding short and -uick answers, the spirit of science is to dele deeper 55

and that is what I want to bring home to my audience and deeper. *on/t be

satisfied with the short and ready -uick answers. $ou must neer be content

with that: you must look around and think and ask all sorts of -uestions;

look round the problem and search, and search and go on searching. In the

course of time you will find some of the truth, but you neer reach the end.

%he end, as I told you, is the human brain, but that is ery far away yet. %his

is the spirit of science. I should gie you an illustration of how by pursuing a

simple -uestion, I can go on talking to you as if I hae just begun, the real

subject of my lecture: "Why the sky is blue". "%he sky is blue because the

illumination of the sky light is due to the scattering of light by the molecules

of the atmosphere". +ow this is a discoery, which came rather slowly. %he

person who first stated this e!planation was the late 1ord &ayleigh.

I think that dreams are the best part of life. It is not the reali(ation, but the

anticipation; I am going to make a discoery tomorrow, that makes a man of

science work hard, whether he makes the discoery or not. #nd this is what I

want to emphasi(e once again. )cience is essentially and entirely a matter of

the human spirit. What does a poet do, What does a painter do, What does a

great sculptor do, .e takes a block of marble, chips, goes on chipping and

chipping. #t the end of it, he produces the dream in the marble. We admire

it. 'ut, my young friends please remember what a tremendous amount of

concentrated effort has gone in to producing that marble piece. It is the hope

of reali(ing something, which will last, foreer, which we will admire

foreer that made him undertake all that work. Bssentially, I do not think

there is the least difference whateer between the urge that dries a man of

science to deote his life to science, to the search for knowledge and the

urge that makes workers in other fields deote their lies to achieing

something. %he greatest thing in life is not the achieement but it is the

desire to achiee. It is the effort that we put in, that ultimately is the greatest

satisfaction. Bffort to achiee something in the hope of getting something;

let it come or not come, but it is the effort that makes life worth liing and if

you don/t feel the urge towards the search for knowledge, you can neer

hope to be a man of science. $ou can perhaps get a job in some of the

departments, get a nice comfortable salary, in which you don/t hae to do

anything e!cept to wait for the monthly che-ue: but that is not science. %he

real business of a scientific man is to try to find something real and to look

forward to the ac-uirement of knowledge.

.aing said all this, may I again come back to the blue sky, I hae not

finished yet. In fact, to tell you the honest truth, I hae only just begun my

lecture. Why is it that the molecules of the air scatter light, %he obious

thing is this, as I told you, the long waes in the spectrum 55 I am using the

language of wae optics 55 the long waes of the red, yellow and the green

are scattered less in the diffused light and the rest -uite strongly, with the

result that the eye perceies this and not that. +ow why is that, %he answer

is ery obious. %he molecules of the atmosphere are e!tremely small in

si(e, incredibly small compared with what is the standard of comparison, the

waelength of light. %he same thing you notice, for e!ample, if you look at a

big lake. %he wind blows on the waes and you hae a piece of cork or

wood floating on it. $ou see the wood trembling. Why, 'ecause the si(e of

the wood is comparable with the si(e of the waes. 'ut suppose you had a

big boat going on the lake; I don/t know how big the boat can be, but you see

that the big boat is not disturbed so much as the small particle. It is the

relationship between the si(e of the disturbance and the si(e of the particle

that determines the effect the waes produce on the particles and ice ersa,

the effect produced by the particles on the waes. %his is the basic principle,

which results in the scattering of the shorter waes by preference. $ou can

show that by any number of e!periments in the laboratory; for that, you don/t

re-uire molecules of air. $ou re-uire just some water and put in it some

substance like bit of soap. $ou can also make the e!periment with smoke:

particles small enough will scatter the shorter waes by preference. 'ut you

don/t get the real rich blue colour unless the particles are e!tremely small.

#nd as I hae already indicated, you must hae ade-uate illumination.

=nless the illumination is strong enough, the sensation will be just the palest

of pale blues. +ow I hae came from the scattering of blue sky to the study

of molecules. #nd there the subject begins and it goes on. In fact, I started

the subject in the year 6C96. What I told you was known pretty well e!cept

the ision part of which I hae spoken about. %hat is my most recent work,

but what I spoke about molecules and so on was all known in 6C>6. #t that

time, we thought it was finished. %oday, we know that the faculty of ision

and the -uality of ision play an immense role in the subject.

%he subject of my lecture is not the blue of the sky, but as you must hae all

understood by this time 5 it is the spirit of science. What is science, #nd

how can we in this country hope to adance science, .ow can we try to

really make ourseles worthy of our ancestors in the past, %hat is the real

topic of my lecture. It is only the peg to hang the subject upon. Well, the

story begins there. %he -uestion is how does light interacts with molecules

and what happens with molecules and what are molecules and so on. )cience

neer stops. It is going on. %he more you find, the more appears that you

hae to find. %hat is the attraction of science, proided you are not distressed

too much by other people getting in front of you. *on/t bother about them.

%he real point is that it is an endless -uest and eery new discoery opens

new paths for discoery. +ew -uestions arise, re-uiring new answers.

'ut then, I cannot gie this lecture without making some reference at least as

to how all this I am talking about is united up with meteorology all the time.

'ut the real interest in the subject is not in meteorology at all. %he real

interest in the subject is the scattering of light, which is the most powerful

weapon we hae today for understanding the ultimate nature of the

molecules of the air. $ou can count the molecules. $ou can make the

e!periment in the laboratory. It is an e!periment, which eery student of

science ought to hae seen. $ou take a glass bottle, a flask and a cork and

get all the dust out of it and send a beam of light, it may be sunlight, it may

be any thing else but see that the beam of the light goes through the air. $ou

can see the air. %he air is not such a transparent, colourless gas; it is not

inisible. $ou can make air isible by means of this scattered light. %his is a

ery simple e!periment and ought to be seen by eery student of science at

least once in his lifetime. $ou can see air. $ou can see any gas. $ou can see

any apor, by the strength of the light diffused by the indiidual particles.

#nd the more particles you hae, the stronger the diffusion. From the

strength of the diffusion, you can actually count the number of molecules. I

use the word counting, not like one, two, three, four: it is a son of differed

type of counting. When I was in the currency office, they used to count the

rupees. $ou know what they did; they did not count the rupees. %hey

counted the bags: they weighed the bags; each bag was supposed to contain

>,999 rupees 55 that had to be taken on trust D and then multiply the number

of bags and you get a crore E69 millionF of rupees. 1ike that, you count the

molecules of the atmosphere. It is only a sort of estimate. 'ut more than

that, we can actually see the scattering of light simply by looking through an

instrument; you can find out whether a molecule is short or long, whether it

is spherical or tetrahedral shape and so on. %he study of the blue sky is an

immense field of research, an unlimited field of research, which was opened

up and is still being pursued.

%he -uest, you see, is the more the deeper you go. %hen the -uestion arises

what about light, I cannot possibly enter into all that. 'ecause, my idea, as I

told you is just to gie you a simple glimpse into how a familiar

phenomenon is linked up with deeper problems of 3hysics and 0hemistry.

%hat is the lesson we learn today. From the familiar fact, it is not necessary

to hunt round the te!tbooks to find problems of science. $ou keep your eyes

open and you see that all round you, the whole world bristles with problems

to sole; but you must hae the wit to sole it; and you must hae the

strength of mind to keep going at it until you get something. %his is the

lesson, which I want to bring home to the younger generation in front of me.

What is the use of all this, .ere again, I want to stress the philosophy of my

life. +eer to ask what is the use of all this.

#s I told you before, it is the striing that is worthwhile. 'ecause we hae

certain inherent powers gien to us to use 5 obseration and thinking 55 we

must use them. %he more we use them, the sharper they become, the more

powerful they become and ultimately something will come out of it so that

humanity is benefited, science is benefited. =ltimately the aim of scientific

knowledge is to benefit human life. #nd that comes automatically because

the problems with which we are concerned in science are always those that

lie nearest to hand. %hey are concerned with things about us. )o long as we

deal with the problem which arise our of our enironment, you neer can

say that any particular piece of work can be useless. %he most important, the

most fundamental inestigations, though at first might seem an abstraction

of nature, are precisely those, which in due course, affect human life and

human actiities most profoundly. %his is a ery heartening thing because

one should not think that scientific work in order to be aluable should be

useful. )cientific work is aluable because it will ultimately proe its alue

for the whole of human life and human actiity. %hat is the history of

modem science. )cience has altered the comple!ion of things around us.

#nd precisely those scientists who hae labored not with the aim of

producing this or that, but who hae worked with the sole desire to adance

knowledge, ultimately proe to be the greatest benefactors of humanity.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Gear Design For Quiet Reduction GearDocument8 pagesGear Design For Quiet Reduction GearTravis WoodPas encore d'évaluation

- Re Voltage StabilityDocument27 pagesRe Voltage StabilityTravis WoodPas encore d'évaluation

- April Is The Cruellest MonthDocument1 pageApril Is The Cruellest MonthTravis WoodPas encore d'évaluation

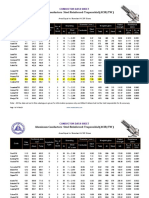

- Aluminum Conductors Steel Reinforced-Trapezoidal (ACSR/TW)Document4 pagesAluminum Conductors Steel Reinforced-Trapezoidal (ACSR/TW)Travis WoodPas encore d'évaluation

- KSEB Technical SPec PDFDocument279 pagesKSEB Technical SPec PDFTravis WoodPas encore d'évaluation

- Anandaram BaruaDocument1 pageAnandaram BaruaTravis WoodPas encore d'évaluation

- Unidirectional Corona RingDocument2 pagesUnidirectional Corona RingTravis WoodPas encore d'évaluation

- Overhead Conductor Installation Guide: Recommended PracticesDocument20 pagesOverhead Conductor Installation Guide: Recommended Practicesvjs270385Pas encore d'évaluation

- Effect of Grading Ring On Voltage Distribution of ArrestorsDocument7 pagesEffect of Grading Ring On Voltage Distribution of ArrestorsTravis WoodPas encore d'évaluation

- Ceramic Manufacturing PDFDocument41 pagesCeramic Manufacturing PDFTravis WoodPas encore d'évaluation

- Enhanced Performance of Zinc Oxide Arrester by Simple Modification in Processing and Design 2169 0022.1000135Document6 pagesEnhanced Performance of Zinc Oxide Arrester by Simple Modification in Processing and Design 2169 0022.1000135Travis WoodPas encore d'évaluation

- SPEED Continuous Panels Plants Design IssuesDocument18 pagesSPEED Continuous Panels Plants Design IssuesTravis WoodPas encore d'évaluation

- 1363 Bolts and Nut Standard PDFDocument7 pages1363 Bolts and Nut Standard PDFTravis WoodPas encore d'évaluation

- Double Sampling-Wha It Means PDFDocument17 pagesDouble Sampling-Wha It Means PDFTravis WoodPas encore d'évaluation

- Fretting Fatigue in Overhead ConductorsDocument16 pagesFretting Fatigue in Overhead ConductorsTravis WoodPas encore d'évaluation

- Ehv Disconnectors For Smart GridDocument2 pagesEhv Disconnectors For Smart GridTravis WoodPas encore d'évaluation

- Study of Single and Double Sampling PlansDocument14 pagesStudy of Single and Double Sampling PlansTravis WoodPas encore d'évaluation

- 3 Sec-III-Hardware Fittings & AccessoriesDocument49 pages3 Sec-III-Hardware Fittings & AccessoriesTravis WoodPas encore d'évaluation

- CT Grounding To Avoid Nuisance TrippingDocument2 pagesCT Grounding To Avoid Nuisance TrippingTravis WoodPas encore d'évaluation

- Transformer Factory Assembly Area LayoutDocument55 pagesTransformer Factory Assembly Area LayoutTravis Wood100% (2)

- SPEED Continuous Panels Plants Design IssuesDocument18 pagesSPEED Continuous Panels Plants Design IssuesTravis WoodPas encore d'évaluation

- ElectricalDocument34 pagesElectricalTravis WoodPas encore d'évaluation

- Spacer Damper IssuesDocument5 pagesSpacer Damper IssuesTravis WoodPas encore d'évaluation

- En 10204-2004 Metallic Products - Types of Inspection DocumentsDocument10 pagesEn 10204-2004 Metallic Products - Types of Inspection DocumentsDalamagas KwnstantinosPas encore d'évaluation

- Innovative Adhesive For Sandwich SystemsDocument20 pagesInnovative Adhesive For Sandwich SystemsTravis WoodPas encore d'évaluation

- Mud Architecture: I J I R S E TDocument6 pagesMud Architecture: I J I R S E TJazzPas encore d'évaluation

- Anil Agarwal: Research: Mud As A Traditional Building MaterialDocument10 pagesAnil Agarwal: Research: Mud As A Traditional Building MaterialTravis WoodPas encore d'évaluation

- CB Spec SvenskaDocument44 pagesCB Spec SvenskaTravis WoodPas encore d'évaluation

- An Introduction To Conway's Games and NumbersDocument30 pagesAn Introduction To Conway's Games and NumbersSilentSparrow98Pas encore d'évaluation

- Bolt InterlocksDocument5 pagesBolt InterlocksTravis WoodPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- CASBA Directive 2074Document17 pagesCASBA Directive 2074vijaycool85Pas encore d'évaluation

- Haberman Data Logistic Regression AnalysisDocument5 pagesHaberman Data Logistic Regression AnalysisEvelynPas encore d'évaluation

- One Wavelength To Loop SkywireDocument2 pagesOne Wavelength To Loop SkywireRobert TurnerPas encore d'évaluation

- Lab Report 1Document23 pagesLab Report 1hadri arif0% (1)

- Q1 Practical Research 2 - Module 1bDocument15 pagesQ1 Practical Research 2 - Module 1bRhea Mae MacabodbodPas encore d'évaluation

- Thursday / January 2019 Thursday / January 2019Document572 pagesThursday / January 2019 Thursday / January 2019Zie EikinPas encore d'évaluation

- Cable Systems For High and Extra-High Voltage: Development, Manufacture, Testing, Installation and Operation of Cables and Their AccessoriesDocument1 pageCable Systems For High and Extra-High Voltage: Development, Manufacture, Testing, Installation and Operation of Cables and Their AccessorieseddisonfhPas encore d'évaluation

- St. Louis College of Bulanao: Title/Topic Technical English I Introduction To Police Report WritingDocument41 pagesSt. Louis College of Bulanao: Title/Topic Technical English I Introduction To Police Report WritingNovelyn LumboyPas encore d'évaluation

- INS2015 Fundamentals of Finance HungCV 1Document3 pagesINS2015 Fundamentals of Finance HungCV 1Phương Anh NguyễnPas encore d'évaluation

- Cooling and Sealing Air System: Gas Turbine Training ManualDocument2 pagesCooling and Sealing Air System: Gas Turbine Training ManualVignesh SvPas encore d'évaluation

- ISO 20000-1 Gap Analysis QuestionaireDocument15 pagesISO 20000-1 Gap Analysis QuestionaireUsman Hamid67% (6)

- Mech Syllabus R-2017 - 1Document110 pagesMech Syllabus R-2017 - 1goujjPas encore d'évaluation

- PienaDocument1 pagePienaMika Flores PedroPas encore d'évaluation

- The Extension Delivery SystemDocument10 pagesThe Extension Delivery SystemApril Jay Abacial IIPas encore d'évaluation

- Electromechanical Instruments: Permanent-Magnet Moving-Coil InstrumentsDocument13 pagesElectromechanical Instruments: Permanent-Magnet Moving-Coil InstrumentsTaimur ShahzadPas encore d'évaluation

- Anatomy & Physiology MCQsDocument26 pagesAnatomy & Physiology MCQsMuskan warisPas encore d'évaluation

- Accommodating Expansion of Brickwork: Technical Notes 18ADocument13 pagesAccommodating Expansion of Brickwork: Technical Notes 18AWissam AlameddinePas encore d'évaluation

- Parkinson S Disease Detection Based On SDocument5 pagesParkinson S Disease Detection Based On SdaytdeenPas encore d'évaluation

- Critique of Violence - Walter BenjaminDocument14 pagesCritique of Violence - Walter BenjaminKazım AteşPas encore d'évaluation

- ResumeDocument3 pagesResumeSaharsh MaheshwariPas encore d'évaluation

- Law of DemandDocument16 pagesLaw of DemandARUN KUMARPas encore d'évaluation

- Studi Tentang Pelayanan Terhadap Kapal Perikanan Di Pelabuhan Perikanan Pantai (PPP) Tumumpa Kota ManadoDocument9 pagesStudi Tentang Pelayanan Terhadap Kapal Perikanan Di Pelabuhan Perikanan Pantai (PPP) Tumumpa Kota ManadoAri WibowoPas encore d'évaluation

- Canadian-Solar Datasheet Inverter 3ph 75-100KDocument2 pagesCanadian-Solar Datasheet Inverter 3ph 75-100KItaloPas encore d'évaluation

- Miracle Mills 300 Series Hammer MillsDocument2 pagesMiracle Mills 300 Series Hammer MillsSPas encore d'évaluation

- Full TextDocument167 pagesFull Textjon minanPas encore d'évaluation

- Response 2000 IntroductionDocument24 pagesResponse 2000 IntroductionRory Cristian Cordero RojoPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction To Rhetorical Analysis: Week 1Document16 pagesIntroduction To Rhetorical Analysis: Week 1Will KurlinkusPas encore d'évaluation

- Permeability Estimation PDFDocument10 pagesPermeability Estimation PDFEdison Javier Acevedo ArismendiPas encore d'évaluation

- PCBDocument5 pagesPCBarampandey100% (4)

- Entrepreneurship: Presented By: Marlon N. Tabanao JR., LPTDocument14 pagesEntrepreneurship: Presented By: Marlon N. Tabanao JR., LPTRoj LaguinanPas encore d'évaluation