Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Rice Today Vol. 13, No. 3 The Two Faces of Rice Prices

Transféré par

Rice TodayTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Rice Today Vol. 13, No. 3 The Two Faces of Rice Prices

Transféré par

Rice TodayDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

40 Rice Today July-September 2014

I

n the wake of the world food price

crisis of 2007-08, the consensus

view is that, because of several

trends (climate change, biofuels,

scarcity of land and water, increased

consumption of meat), we are

entering a new era in which food

prices will be higher. How has this

played out so far in the case of rice?

Cheaper on the world market

Certainly, world market rice prices

have increased. The price of Thai 5%

broken milled rice was 56% higher

in 2013 than in 2007. But, this is

misleading because, after adjusting

for ination, the price of Thai 5%

broken rice increased by just 39%

during that time. More importantly,

Thailand is no longer the center of

the world rice market, and prices

from other sources have increased by

much less. In real terms, the price of

Vietnamese 5% broken rice increased

by just 11% over the same interval,

and the prices of 25% broken rice

from India and Pakistan increased by

24% and 14%, respectively.

But even these numbers overstate

the extent of eective changes in

world prices, because the currencies

of most Asian countries appreciated

in real terms vis--vis the U.S. dollar

by 1020% during this time, thus

mitigating the extent of the world

price increase. When real exchange

rates appreciate, that means it is

cheaper to buy products on the world

market in local currency. Thus, for all

large Asian developing countries, the

opportunity cost of Vietnamese rice

in real local currency terms in 2013

(i.e., after adjusting for ination and

real exchange rate appreciation) was

about equal to or lower than it was in

2007 before the crisis.

Simply put, this means that,

for those who need to purchase

it, rice was cheaper in 2013 than it

was before the crisis in 2007. And,

world market prices have fallen even

further in the rst few months of

2014.

Higher domestic prices

Despite the constant or lower

opportunity cost of rice on the

world market, domestic rice prices

increased in real terms in these

same countries from 2007 to 2013

(see gure). One of the key recent

developments in the Asian rice

economy has been the increase in

buying prices paid to farmers in

some countries. This trend has been

particularly pronounced in Thailand

and China, where buying prices

paid to farmers have increased by

92% and 59%, respectively, over the

past 6 years. In contrast, buying

prices in India have increased by

17%, while in Bangladesh they have

increased by only a modest 6%

(all changes are in local currency

terms, adjusted for ination). In

both Thailand and China, broader

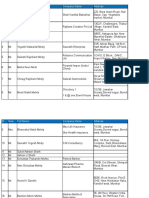

International and domestic prices are moving in dierent directions, thus creating two

dierent eects on farmers and consumers

Percentage changes in world and domestic prices, ination-adjusted local currency terms, 2007-13.

Source: National statistical agencies, International Monetary Fund.

40

30

20

10

0

10

20

30

Bangladesh

Cambodia

China

India Indonesia

Lao PDR

World price

Domestic price

Nepal

Pakistan

Philippines Sri Lanka

Thailand

Vietnam

Percentage

The two faces

of rice prices

f a c e s

by David Dawe

Rice facts

RT13-3 (p24-44).indd 40 7/15/2014 4:57:22 PM

41 Rice Today July-September 2014

measures of domestic rice prices

have also increased substantially:

comparing 2013 with 2007, wholesale

market prices increased by 20%

and 38%, respectively, in real terms.

These large increases took place

although the baht and the yuan

have appreciated by more than the

world price of Vietnamese 5% broken

has increased. In other words, the

opportunity cost of rice on the world

market has actually declined in real

local currency terms for both of

these countries.

Why have domestic prices

increased so much in these two

countries? Both of them have

witnessed exceptional economic

growth rates over the past few

decades, leading to a structural

transformation of their economies.

At the same time, the share of

agriculture in employment remains

well above its share in gross domestic

product (GDP), meaning that

agricultural producers and workers

are less productiveand have lower

incomesthan those in other sectors

of the economy. This economic

change is di cult for many people

who rely on farming as a key source

of incomeand add to this the fact

that China and Thailand have the

highest income inequality in the

region. Thus, these countries are

raising domestic prices to provide

more support to farmers and to

reduce inequality, both politically

popular. China has also carried out

other measures to support farmer

income, such as cash transfers and

income tax exemptions.

A second key development

in recent years has been the push

toward self-su ciency in the wake of

the world rice price crisis, especially

by Indonesia and the Philippines,

which are traditionally the largest

importers in the region. These two

countries have occasionally lowered

their rice imports during the past

decade although domestic rice

prices have been well above prices

on the international market. This

push toward self-su ciency has

meant that domestic prices in these

countries are rising even higher:

rice prices in the Philippines in 2013

were 16% higher than they were in

2007, and 17% higher in Indonesia

(both after adjusting for ination). In

Indonesia, local prices in 2013 were

88% higher than the average during

1975-95, when domestic prices were

stable around the trend of world

prices.

The rising prices in these

two countries are partially due

to the same factors of structural

transformation in China and

Thailand, but also because their

status as traditional importers makes

them more vulnerable to uctuations

on the international rice marketa

market that is now viewed as more

unstable than in the wake of the food

price crisis.

The trends of rising domestic

prices are not found everywhere in

the regionprices have declined

in poor countries such as Vietnam,

Lao PDR, and Nepal. Prices have

increased, but by small amounts,

in other poor countries such as

Bangladesh and Cambodia. Because

these countries are substantially

poorer than the countries discussed

above, they are less advanced in

the process of structural economic

transformation. Their income

inequality is also generally lower.

When domestic prices are higher

What are the consequences of higher

domestic prices? Higher domestic

prices are not generally good for

poverty as they harm poor rice

consumers (who in countries such

as Indonesia and the Philippines

are the poorest of the poor). Even in

exporting countries such as Thailand,

most of the benets of higher prices

end up with the farmers with the

most land because benets accrue

only when marketed surplus is sold.

Higher rice prices can also raise

workers wages to compensate for the

higher food prices, thereby reducing

the competitiveness of the industrial

sector without beneting workers.

Although higher domestic rice prices

may eventually be inevitable, as in

Japan and Korea, the rise in domestic

prices in some ASEAN countries is

probably happening too early in the

development process.

These costs are important to note,

but political imperatives often dictate

that farmers must be supported in

some way. In this case, it is important

to design programs that transfer

the needed nancial resources at

the lowest possible cost, avoiding

excessive losses due to leakage to

people who are not poor. It is also

desirable to avoid large distortions

in resource allocation that delay

agricultural diversication. Some

types of cash transfer programs,

either unconditional or conditional on

school atendance, may help in this

regard.

What do rising domestic prices

mean for the world rice market? As

domestic prices increase above world

market prices in some countries,

farmers are encouraged to produce

more rice and consumers to buy less.

These added supplies and lower

demand mean fewer imports from

some countries, and eventually more

exports from others (assuming the

rice is not allowed to rot in storage).

These trends will lead to downward

pressure on international prices,

possibly negating the consensus view

that we are now in a new era of high

world rice prices.

Lower world prices in turn

will make it harder to continually

nance the high domestic farm

prices. Many developed countries

can aord such subsidies because

their agricultural sector is a much

smaller share of the economy. They

can provide substantial benets to

farmers without undue strain on

the government budget. But, the

opportunity cost of subsidies is much

higher in poor countries, and it is

not clear whether such subsidies

are sustainablewitness the recent

unwinding of the paddy pledging

program in Thailand (see more on

the Thai situation in the Rice facts on

pages 38-39). If such subsidies do not

continue, the world price, after falling

for a time in the near term, will then

eventually rise again.

Dr. Dawe is a senior economist in the

Agricultural Development Economics

Division of the Food and Agriculture

Organization of the United Nations.

RT13-3 (p24-44).indd 41 7/15/2014 4:57:22 PM

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Rice Today Special Supplement For The Philippine Department of Agriculture Management Committee Meeting, 6-8 April 2015Document48 pagesRice Today Special Supplement For The Philippine Department of Agriculture Management Committee Meeting, 6-8 April 2015Rice TodayPas encore d'évaluation

- Rice Today Vol. 14, No. 2Document37 pagesRice Today Vol. 14, No. 2Rice TodayPas encore d'évaluation

- Rice Today Vol. 14, No. 2 GOTDocument2 pagesRice Today Vol. 14, No. 2 GOTRice TodayPas encore d'évaluation

- Rice Today Vol. 14, No. 2 Home-Made Noodles From GhanaDocument1 pageRice Today Vol. 14, No. 2 Home-Made Noodles From GhanaRice TodayPas encore d'évaluation

- Rice Today Vol. 14, No. 2 What Kind of Rice Do Consumers Want?Document1 pageRice Today Vol. 14, No. 2 What Kind of Rice Do Consumers Want?Rice TodayPas encore d'évaluation

- Rice Today Vol. 14, No. 2 Revisiting 50 Years of Indian Rice ResearchDocument2 pagesRice Today Vol. 14, No. 2 Revisiting 50 Years of Indian Rice ResearchRice TodayPas encore d'évaluation

- Rice Today Vol. 14, No. 2 Indian Farmer Kick-Starts Two Green RevolutionsDocument1 pageRice Today Vol. 14, No. 2 Indian Farmer Kick-Starts Two Green RevolutionsRice TodayPas encore d'évaluation

- Rice Today Vol. 14, No. 2 A Schoolboy at Heart: Celebrated Indian Scientist Speaks His MindDocument3 pagesRice Today Vol. 14, No. 2 A Schoolboy at Heart: Celebrated Indian Scientist Speaks His MindRice TodayPas encore d'évaluation

- Rice Today Vol. 14, No. 2 Rice Scientists From India Helping AfricaDocument1 pageRice Today Vol. 14, No. 2 Rice Scientists From India Helping AfricaRice TodayPas encore d'évaluation

- Rice Today Vol. 14, No. 2 Yield Rises With WeRiseDocument1 pageRice Today Vol. 14, No. 2 Yield Rises With WeRiseRice TodayPas encore d'évaluation

- Rice Today Vol. 14, No. 2 DRR Rice Museum Features Traditional Wisdom and Scientific BreakthroughsDocument1 pageRice Today Vol. 14, No. 2 DRR Rice Museum Features Traditional Wisdom and Scientific BreakthroughsRice TodayPas encore d'évaluation

- Rice Today Vol. 14, No. 2 What Latin America's Rice Sector Offers The WorldDocument2 pagesRice Today Vol. 14, No. 2 What Latin America's Rice Sector Offers The WorldRice TodayPas encore d'évaluation

- Rice Today Vol. 14, No. 2 India Reaches The Pinnacle in Rice ExportsDocument3 pagesRice Today Vol. 14, No. 2 India Reaches The Pinnacle in Rice ExportsRice TodayPas encore d'évaluation

- Rice Today Vol. 14, No. 2 Nuggets of Planetary TruthDocument1 pageRice Today Vol. 14, No. 2 Nuggets of Planetary TruthRice TodayPas encore d'évaluation

- Rice Today Vol. 14, No. 2 Regional Cooperation Speeds Up The Release of Rice VarietiesDocument1 pageRice Today Vol. 14, No. 2 Regional Cooperation Speeds Up The Release of Rice VarietiesRice TodayPas encore d'évaluation

- Rice Today Vol 14, No. 2 Averting Hunger in Ebola-Hit CountriesDocument1 pageRice Today Vol 14, No. 2 Averting Hunger in Ebola-Hit CountriesRice TodayPas encore d'évaluation

- Rice Today Special SupplementDocument27 pagesRice Today Special SupplementRice TodayPas encore d'évaluation

- Rice Today Vol. 14, No. 2 Celebrating 50 Years of Impact Through Rice Research in IndiaDocument1 pageRice Today Vol. 14, No. 2 Celebrating 50 Years of Impact Through Rice Research in IndiaRice TodayPas encore d'évaluation

- Rice Today Vol. 14, No. 2 Striking A Balance Through Ecologically Engineered Rice EcosystemsDocument2 pagesRice Today Vol. 14, No. 2 Striking A Balance Through Ecologically Engineered Rice EcosystemsRice TodayPas encore d'évaluation

- Rice Today Vol. 14, No. 1 Uruguayan Rice The Secrets of A Success StoryDocument2 pagesRice Today Vol. 14, No. 1 Uruguayan Rice The Secrets of A Success StoryRice TodayPas encore d'évaluation

- Rice Today Vol. 14, No. 1 Where's My GM RiceDocument1 pageRice Today Vol. 14, No. 1 Where's My GM RiceRice TodayPas encore d'évaluation

- Rice Today Special Supplement For Farmers' DayDocument23 pagesRice Today Special Supplement For Farmers' DayRice TodayPas encore d'évaluation

- Rice Today Vol. 14, No. 1 Unleashing The Rice MarketDocument2 pagesRice Today Vol. 14, No. 1 Unleashing The Rice MarketRice TodayPas encore d'évaluation

- GRiSP: Partnerships For SuccessDocument1 pageGRiSP: Partnerships For SuccessRice TodayPas encore d'évaluation

- Rice Today Vol. 14, No. 1 Making Rice More Competitive in Latin AmericaDocument2 pagesRice Today Vol. 14, No. 1 Making Rice More Competitive in Latin AmericaRice TodayPas encore d'évaluation

- Rice Today Vol. 14, No. 1 Tah Chin Saffron Rice and ChickenDocument1 pageRice Today Vol. 14, No. 1 Tah Chin Saffron Rice and ChickenRice TodayPas encore d'évaluation

- Rice Today Vol. 14, No. 1 Trends in Global Rice TradeDocument2 pagesRice Today Vol. 14, No. 1 Trends in Global Rice TradeRice Today100% (1)

- Rice Today Vol. 14, No. 1 The Rise of Rice On Peru's Sacred GroundDocument2 pagesRice Today Vol. 14, No. 1 The Rise of Rice On Peru's Sacred GroundRice TodayPas encore d'évaluation

- Rice Today Vol. 14, No. 1 Green Revolutions 2.0 & 3.0 No Farmer Left BehindDocument2 pagesRice Today Vol. 14, No. 1 Green Revolutions 2.0 & 3.0 No Farmer Left BehindRice TodayPas encore d'évaluation

- Rice Today Vol. 14, No. 1 Korea The Good BrothersDocument1 pageRice Today Vol. 14, No. 1 Korea The Good BrothersRice TodayPas encore d'évaluation

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5782)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (72)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- BIR issues electronic letters of authorityDocument3 pagesBIR issues electronic letters of authorityAatDeskHelperPas encore d'évaluation

- The Contribution of Subsidies On The Welfare of Fishing Communities in MalaysiaDocument8 pagesThe Contribution of Subsidies On The Welfare of Fishing Communities in Malaysiahaidawati amriPas encore d'évaluation

- Actg Coach Actg Princ1Document3 pagesActg Coach Actg Princ1Amir IrfanPas encore d'évaluation

- BG To Be Issued by A Local Foreign Bank of The Required Country (Counter Guarantee Issuance)Document3 pagesBG To Be Issued by A Local Foreign Bank of The Required Country (Counter Guarantee Issuance)TicketReelPas encore d'évaluation

- BCOM VI Sem GST topicsDocument3 pagesBCOM VI Sem GST topicsVikram KatariaPas encore d'évaluation

- Thesis On Insurance Sector in IndiaDocument6 pagesThesis On Insurance Sector in Indiaaprilchesserspringfield100% (2)

- RocketBlocks - Techniques - MarketSizingDocument3 pagesRocketBlocks - Techniques - MarketSizingSunny SouravPas encore d'évaluation

- Credit Agricole - SWOTDocument1 pageCredit Agricole - SWOTMandula KumarasinghaPas encore d'évaluation

- Fringe BenefitDocument20 pagesFringe BenefitlalithagurungPas encore d'évaluation

- Advantages and Disadvantages of The Fisheries Trade: Yoshiaki MatsudaDocument11 pagesAdvantages and Disadvantages of The Fisheries Trade: Yoshiaki MatsudaKristine M. BarcenillaPas encore d'évaluation

- Non Linear DynamicsDocument309 pagesNon Linear DynamicsZomishah Kakakhail100% (4)

- Infosys Strategic AnalysisDocument39 pagesInfosys Strategic Analysisshahidnmims100% (29)

- Istory of The Company KsfeDocument16 pagesIstory of The Company KsfeAjayanKavilPas encore d'évaluation

- Lehman Examiner's Report, Vol. 4Document493 pagesLehman Examiner's Report, Vol. 4DealBookPas encore d'évaluation

- IGCSE MCQ ChecklistDocument8 pagesIGCSE MCQ ChecklistDhrisha GadaPas encore d'évaluation

- Course Title: Macroeconomics I: Chapter 1 of HeijdraDocument2 pagesCourse Title: Macroeconomics I: Chapter 1 of Heijdrakthesmart4Pas encore d'évaluation

- Telecom Sector in IndiaDocument0 pageTelecom Sector in IndiaSonny JosePas encore d'évaluation

- Lets Do Business Together Participant InfoDocument25 pagesLets Do Business Together Participant InfoRakesh JainPas encore d'évaluation

- Comfort & Harmony: Bouncer Asiento Transat Wiegewippe Balanço-bercinho кресло-качалкаDocument28 pagesComfort & Harmony: Bouncer Asiento Transat Wiegewippe Balanço-bercinho кресло-качалкаJohn SmithPas encore d'évaluation

- Perspective of ColonialismDocument21 pagesPerspective of Colonialismtarishi aroraPas encore d'évaluation

- CNFC Media PVT LTDDocument21 pagesCNFC Media PVT LTDshekhar_cnfcmedia100% (1)

- PEP Assignment 2Document3 pagesPEP Assignment 2Wajeeha NadeemPas encore d'évaluation

- (1955) How To Build and Operate A Mobile Home ParkDocument160 pages(1955) How To Build and Operate A Mobile Home ParkHerbert Hillary Booker 2nd100% (3)

- جديد كبارى-1 LRFDDocument35 pagesجديد كبارى-1 LRFDamaary31Pas encore d'évaluation

- CanadaDocument2 pagesCanadaapi-301526689Pas encore d'évaluation

- Netflix Case StudyDocument57 pagesNetflix Case StudyPurna Wayan100% (7)

- Mixed Economy The Three Economic QuestionsDocument4 pagesMixed Economy The Three Economic QuestionsBasco Martin JrPas encore d'évaluation

- Apply for Social Security Card OnlineDocument5 pagesApply for Social Security Card OnlinecesarPas encore d'évaluation

- Few Successful Entrepreneurship Stories For RecruitmentDocument15 pagesFew Successful Entrepreneurship Stories For RecruitmentpallavcPas encore d'évaluation

- Pecking Order TheoryDocument2 pagesPecking Order TheoryBijoy SalahuddinPas encore d'évaluation