Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

5 Race and Racism in Marx's Camera Obscura

Transféré par

DaysilirionDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

5 Race and Racism in Marx's Camera Obscura

Transféré par

DaysilirionDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

http://crs.sagepub.

com/

Critical Sociology

http://crs.sagepub.com/content/32/4/617

The online version of this article can be found at:

DOI: 10.1163/156916306779155207

2006 32: 617 Crit Sociol

Paul Paolucci

Race and Racism in Marx's Camera Obscura

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

can be found at: Critical Sociology Additional services and information for

http://crs.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Email Alerts:

http://crs.sagepub.com/subscriptions Subscriptions:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Reprints:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Permissions:

http://crs.sagepub.com/content/32/4/617.refs.html Citations:

What is This?

- Jul 1, 2006 Version of Record >>

by Pepe Portillo on July 29, 2014 crs.sagepub.com Downloaded from by Pepe Portillo on July 29, 2014 crs.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Critical Sociology, Volume 32, Issue 4 also available online

2006 Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden www.brill.nl

* For correspondence: Paul Paolucci, Department of Anthropology, Sociology, and

Social Work, Eastern Kentucky University, 107 Keith Building, Richmond, KY 40475,

USA, E-mail: paul.paolucci@eku.edu.

Race and Racism in Marxs

Camera Obscura

P.tr P.ortcci*

(Eastern Kentucky University)

Ans+n.c+

The charge that Marxs work leaves sociologists few tools with

which to understand the phenomena of race and racism has

been a common one. Against such claims, this essay attempts

to mobilize several analytical devices in Marxs work that help

us grasp race and racism as sociological realities. These include

an understanding of the inversion process (referred to here as

the camera obscura) Marx asserted was inherent to bourgeois

ideology, his method of addressing the issue of tautology in

the philosophy of science, and his approach to political-economic

analysis. These aspects of Marxs work are essential for any

study of race and racism in modern capitalist societies.

Krv vonrs: camera obscura, Marx, race and racism, slavery,

colonialism, Christianity, taxonomy, biology, world-system.

Racism persists, but not simply or only because of fallacious beliefs held

by a critical mass of people. Racism is something other and more than

a collection of attitudes and its persistence cannot be explained by some

deep-seated aw in the human character. Racism is at its core a sociological

phenomenon and the social conditions which underlie it persist. Systematic

racism is the outcome of interrelationships between political-economic

factors unique to modernity and forms of discursive knowledge both

CS 32,4_f6_617-648I 11/13/06 1:46 PM Page 617

by Pepe Portillo on July 29, 2014 crs.sagepub.com Downloaded from

618 Paolucci

1

While Marx, unlike Weber or Durkheim, cannot be accused of supporting national

prejudicial allegiance over commitment to the working class as an international movement,

he can be accused of being trapped within forms of racial thinking common to his

period. For example, one of the premises of racial thinking is the assumption of a corre-

lation between physical and character traits. Marx accepted, at least in part, this view,

once writing to Kugelmann that phrenology is not the baseless art which Hegel imag-

ined ( Letter to Kugelmann, January 11, 1868, in Padover 1979:241). More than once

he referred to niggers, with only a slightly less condescending posture expected for the

time period. Of his son-in-law, a mulatto from Cuba, Marx wrote: Lafargue has the

usual stigma of the Negro tribe: no sense of shame, I mean thereby no modesty about

making himself ridiculous ( Letter to Engels, November 11, 1882, in Padover 1979:399).

Marx often referred to Lassalle, his competitor / comrade, Jew-boy Braun, Jewish

Nigger, and Itzig, another anti-Semitic tag (see: Letters to Engels, in Padover 1979:435,

466, 473). In all fairness, Marx was ecumenical, allowing negative racial traits for all

nationalities: full of pretensions to that superiority with which the true Briton, thanks to

a special gift for stupid ignorance, is lled ( Letter to Pyotr Lavrovich Lavrov, January 23,

1882, in Padover 1979:356). Also, in reference to the American Civil War, Marx wrote:

You will have rejoiced, as I did, at the defeat of President Johnson at the last election.

The workers of the North have nally come to understand very well: that a white skin

cannot emancipate itself so long as a black skin is branded ( Letter to Francois Lafargue,

November 12, 1866, in Padover 1979:223).

pre-dating it and internal to it. Understood in this context, a Marxist

perspective can assist in explaining how race as a form of knowledge

and racism as a social institution came to be.

Though sociological frameworks for studying the relation between racial

identities and institutional racism exist, it is commonly assumed that

Marxs work fails to oer useful, sucient, and / or necessary tools with

which to understand their dynamics. His direct comments on racial ques-

tions often support this conclusion.

1

In his defense, this paper argues

three features of Marxs work are crucial for understanding the rela-

tionship between historical events, the rise of race as an element of dis-

cursive knowledge, and racism as a key variable in the stratication

system in the modern capitalist world-economy: (1) his assertion that

knowledge in capitalist society becomes inverted as if in a camera

obscura; (2) his sensitivity to tautological reasoning in the philosophy of

science; and, (3) his political-economic analysis of the historico-structural

dynamics of capitalism.

Before laying out the argument, a statement of the specic relevance

of this inquiry is necessary. Several of the arguments below have been

covered elsewhere and this paper does not pretend to bring its reader

groundbreaking research on racist science (see: Gould 1981; Fredrick-

son 1981; Shipman 1994; Graves 2001; Harding 1993). Indeed, this essay

relies heavily upon them. What this paper attempts to show is how a

CS 32,4_f6_617-648I 11/13/06 1:46 PM Page 618

by Pepe Portillo on July 29, 2014 crs.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Race and Racism in Marxs Camera Obscura 619

Marxist view brings necessary insights to such issues and to the topic of

racism itself, something which is not addressed in these otherwise excel-

lent analyses.

The Camera Obscura

Marxs conceptual-analytical strategies related to the camera obscura

eect have been covered previously in the pages of Critical Sociology

(Paolucci 2001). Nevertheless, a brief review of its origins and how it

nds use in Marxs ideas is necessary in order to develop the concept

anew for the issue of race and racism in history.

In constructing concepts, sociologists must abstract structural wholes

out from history, and from structural wholes they must abstract out the

essential parts that comprise those wholes. However, not all possible con-

cepts that can be used to think about the world require the same pre-

cision in their construction. The idea of beauty is necessarily less

precisely denable than is the speed of light. Conceptual abstractions

can be plotted on a hypothetical line stretching form very arbitrary to

very systematic. Ideally, scientic concepts are abstracted as systemati-

cally as possible. In reference to the dierence between these two poles,

it is a matter of where and how one draws boundaries and establishes

units . . . in which to think about the world (Ollman 1993:11).

In the social sciences, an attempt is made to create sound and logi-

cal categories that hang together well and correspond to appropriate

ontological and epistemological assumptions as well as empirical obser-

vations. In his critique of poorly formed conceptualizations, Marx claimed

several times that a reversal of ideas, concepts, and truth-value occurred

in bourgeois thought. The German Ideology, for example, asserts, If in all

ideology men and their relations appear upside-down as in a camera

obscura, this phenomenon arises just as much from their historical life-

process as the inversion of objects on the retina does from their physi-

cal life-process (Marx and Engels 1976:36). Marx and Engels used this

phraseology to depict a process whereby knowledge and reality are pre-

sented to consciousness in an inverted form of their real historical rela-

tions. Was this analogy simply a literary device that oers only fuzzy

analytical value? Or, does Marxs exposition provide comment on the

mechanisms in intellectual discourse that function as a conceptual cam-

era obscura? Three are developed here and applied to the history of

racism as a way of putting this concept, and by extension Marxs con-

tribution to race studies, to work. Before applying this concept to the

history of race and racism, its origins deserve a brief historical note.

CS 32,4_f6_617-648I 11/13/06 1:46 PM Page 619

by Pepe Portillo on July 29, 2014 crs.sagepub.com Downloaded from

620 Paolucci

Aristotle is credited with one of the earliest observations of the invert-

ing eect natural processes such as light go through under special con-

ditions. According to tradition, during an eclipse he noticed that the

shadows of leaves become fragmented. While he did not understand why

this was so, he did take moment to comment on it. Pope John XII later

asserted this was Satans work. Over time, dierent observers began to

understand the process much better and even learned how to build

devices that reproduced the eect, one of which was the camera obscura

and became a foundation of later photographic technology. Initially used

in both the apprenticeship of artists and as attractions at fairs and expo-

sitions, in it an image was manufactured on one side that would appear

to the viewer on the other in an inverted or upside down form. In its

physical-mechanical form, this eect was clearly seen, if not always under-

stood. Marxs contention, conversely, is that the same eect material con-

ditions have on ideological constructions is not always clearly seen and

more rarely understood. It is the task of scientic thought to locate and

solve this problem. Inspection of Marxs methodological principles reveals

three mechanisms which account for this camera obscura eect.

Mechanism One: Mis-specication of Historical Data

The appropriate historico-structural context in which to interpret data is

vitally important. Marx believed that when a social relation, such as the

capitalist mode of production, is interpreted as eternal and natural, the

result is a mis-specication of the historical context of the data made

possible by this system. Pitched at the universal level, the conceptualized

present is treated as an example of the sociologically general. This treats

capitalism, a unique set of structural relationships, as a transhistorical

social fact. According to Marx (1988:7071), this falsely universalizes a

historically specic social relation:

Do not let us go back to a ctitious primordial condition as the political

economist does, when he tries to explain. Such a primordial condition explains

nothing. He merely pushes the question away into a gray nebulous distance.

He assumes in the form of fact, of an event, what he is supposed to deduce

namely, the necessary relationship between two things between, for exam-

ple, division of labor and exchange. Theology in the same way explains the

origin of evil by the fall of man; that is, it assumes as a fact, in historical

form, what has to be explained.

If all of history has been a repetition of universal processes, then the

specic historical relationships that account for the present tend to be

obscured in such a framework.

CS 32,4_f6_617-648I 11/13/06 1:46 PM Page 620

by Pepe Portillo on July 29, 2014 crs.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Race and Racism in Marxs Camera Obscura 621

Mechanism Two: The Modernistic Fallacy

The second mechanism, extending the rst, uses concepts whose conditions

of possibility rest upon recently developed structural relations to inter-

pret empirical events occurring at prior levels of historical generality. If

unaware how recent a phenomenon and its attendant concept are, then

an analyst is likely to interpret all previous history, whether in moder-

nitys mode of production but at a dierent era of its development, or

even all historical social systems, through concepts more applicable to

the immediate present (or the very recent past). Assuming that many

concepts are historical, Marx (1973:83) complained about Smith and

Ricardo . . .

. . . in whose imaginations this eighteenth century individual the product on

one side of the dissolution of the feudal forms of society, on the other side of

the new forces of production developed since the sixteenth century appears

as an ideal, whose existence they project into the past. Not as a historic

result but as historys point of departure. As the Natural Individual appro-

priate to their notion of human nature, not arising historically, but posited

by nature. This illusion has been common to each new epoch to this day.

Conceptual frameworks made possible by modernity should not be used

as the interpretive basis for prior historical systems. Marx asserts that

this problem, while exemplied in bourgeois ideology, has thus far in his-

tory been a consistent problem in human knowledge in general.

Mechanism Three: The Forward Imposition

of Modernity on History

In his discussion of the fetishism of commodities, Marx (1992:80) con-

tinued to develop this analytical framework:

Mans reections on the forms of social life, and consequently, also, his

scientic analysis of those forms, take a course directly opposite to that of

their actual historical development. He begins, post festum, with the results of

the process of development ready to hand before him. The characters that

stamp products as commodities, and whose establishment is a necessary pre-

liminary to the circulation of commodities, have already acquired the stabil-

ity of natural, self-understood forms of social life, before man seeks to decipher,

not their historical character, for in his eyes they are immutable, but their

meaning . . . The categories of bourgeois economy consist of such like forms.

They are forms of thought expressing with social validity the conditions and

relations of a denite, historically determined mode of production, viz. the

production of commodities.

CS 32,4_f6_617-648I 11/13/06 1:46 PM Page 621

by Pepe Portillo on July 29, 2014 crs.sagepub.com Downloaded from

622 Paolucci

This nal mechanism imposes modern, usually ocial and dominant,

frameworks of knowledge on a forward reading of history. Summarizing

the entire process just reviewed, the analyst rst assumes that all socio-

logical processes in history are pitched at the same level of historical and

structural reality. Next, they mistake a concept (usually not recognized

to have been) built on a current and historically specic social form as

a social universal and/or the product of an eternal human nature. This

concept is then used as a sieve to lter out (supposed) historical cases of

the same for analysis, cases that are now taken as representative expres-

sions of a universal phenomenon. This method allows the analyst

depending on their topic of interest to choose an arbitrary moment

in the linear past and then do a forward history of the phenomenon

armed with a conceptual framework founded in modernitys material

relations. The result is a form of discursive knowledge that reies the

present and inverts its real history by reading the present into the past.

In a very backward manner, analysis of social structure subsequently

tends to be both reied and obscured by such a construction of subject

matter (for previous discussion, see Paolucci 2001:107110).

Race and Racism in the Camera Obscura:

Reversing the Relationship

Idealism in bourgeois discourse assumes the opinions of aggregated indi-

viduals are the primary causal factors of historical and social relations.

Conceptualized as such, European elites attitudes about physical appear-

ance have been commonly assumed to be the primary motive factor for

the introduction of chattel slavery in the colonial sphere. This is perhaps

the most commonplace and sociologically erroneous assumption about

race/ethnic relations in modern discourse, whether held by the lay public

or by social scientists. In a previous conceptualization of Marxs camera

obscura framework, a comment on its relationship to racism was made:

instances of labor exploitation in ancient Rome and the antebellum South

are both understood as slavery, but the dierences between them are often

not noted and thus the qualitatively divergent aspects of them are obscured

e.g. slavery in Rome was not lifelong, humans never became the status of

non-human chattel, nor was it a rationalized and commodied industry.

Equating them minimizes the harshness of the US slave industry by rela-

tivizing it to Romes version of the spoils of war. Additionally, failure to get

the causal mechanisms in the right order forces one to make illogical and

empirically unsupportable assumptions/conclusions. For example, students are

constantly surprised to learn that racial-ideology came after rather than before

the institutionalization of European and American slavery. (Paolucci 2001:109)

CS 32,4_f6_617-648I 11/13/06 1:46 PM Page 622

by Pepe Portillo on July 29, 2014 crs.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Race and Racism in Marxs Camera Obscura 623

Source: Russell Naughton, Adventures in Cybersound. Reprinted with Permission.

Retrieved from: http://www.acmi.net.au/AIC/CAMERA_OBSCURA.html,

August 21, 2006.

Figure 1. Figurative Model of the Camera Obscura Eect from 16th Century:

Reinerus Gemma-Frisius, 1544.

Unfortunately, this statement was left unsubstantiated. Here, an attempt

is made to defend this claim. Mis-specication of modern European slav-

ery as being of the same as Roman or all historical forms of slavery

obscures its systematic and extraordinarily cruel nature. But more impor-

tant, such an approach obscures inquiry into the specic and unique

features of capitalist slavery, including how the US stratication system

evolved and the internal relationship among systems of thought domi-

nating social and scientic discourse.

In neither the Greek nor the Roman civilization was there a rela-

tionship between slavery and race (Graves 2001:20). Nor, it might be

added, did American slavery begin as a racial system. American slavery

was the most intense result of modern European forms of worldwide

labor exploitation (Cox 1976). To assume enslavement of Africans in the

Americas was the outcome of the irrational opinions of English, Spanish,

Portuguese and/or American elites overlooks and thus obscures those

same elites attempts to enslave, visit genocide upon, or otherwise violently

subjugate almost every indigenous, peasant, and proletarian population

CS 32,4_f6_617-648I 11/13/06 1:46 PM Page 623

by Pepe Portillo on July 29, 2014 crs.sagepub.com Downloaded from

624 Paolucci

Source: Bright Bytes Studio, Jack & Beverly Wilgus. Reprinted with Permission.

Figure 2. Depiction of Camera Obscura at Weston-Super-Mare Pier, England.

they encountered, from the Irish, to the Native Americans and Indians

of Mexico, to West Africans, South Africans, and South East Asians. As

a result of this mis-specication, racisms place is often misconstrued as

a causal historical variable in modern relations of exploitation.

It was not racism in favor of the masses in Europe and racism against

African tribesmen that turned Africans into slaves. The British enslaved

the Irish for a time and both Irish and British peasants were viewed as

lesser breeds. While it is true that pre-capitalist European ideological

discourse posited Africans (and others) as exotic, primitive, or otherwise

as an other, this status was not at rst based solely on skin color but

rather a whole set of additional factors including language, region, and

religion, among others. In the Cape of South Africa, a large proportion

of slaves were imported from East Asia, not Africa, though an attempt

CS 32,4_f6_617-648I 11/13/06 1:46 PM Page 624

by Pepe Portillo on July 29, 2014 crs.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Race and Racism in Marxs Camera Obscura 625

was made to enslave the local population there. The South African

colonists ran into the same problem as experienced by the colonists in

North America, that is, enslaving local populations was extremely dicult

(Fredrickson 1981). Early English attitudes toward Africans were hardly

worse or more acidic than their attitudes toward European peasant classes

(though one should not underestimate the European ideological baggage

that associated the color black with dirtiness and white with purity; see:

Jordan 1974). Early on there was no mention of race or skin color in

debates on who was and who was not eligible for slavery. Portuguese,

Spanish, Dutch, and English colonial elites made no distinctions based

on skin color (or any other supposed racial criteria) as to whether those

in Ireland, South America, Africa, South East Asia, or North America

were t for enslavement. The evidence strongly suggests that Africans

and other non-Europeans were initially enslaved not so much because

of their color and physical type as because of their legal and cultural

vulnerability, writes Fredrickson. The combination of so-called hea-

thenness (i.e., non-Christian status) and captivity (as in a captured solider

of war) was stressed. Therefore, it is misleading and anachronistic to

read the overt physical racism that emerged later back into the thought

of this era (Fredrickson 1981:70, 73).

Early colonial legal theory viewed slaves as spoils of war, where enslave-

ment was viewed as an alternative to execution. The individual lost their

rights as prisoners and became the property of the victor (based on

Lockes philosophy), a status that did not change if bought or sold. While

slavery was made illegal in England and Holland, their laws did not pre-

vent their citizens from engaging in the trade (called the custom of mer-

chants for Christian nations). Purchasing slaves whether from Africa

or Asia was thus an international trade. While European traders some-

times provoked wars to encourage it, by the modern era the tradition

of enslaving captured soldiers had ended, bringing the need for new psy-

chological justications for slavery. The claim that Africans were hea-

thens constructed the slave trade as contributing to the mission of

Christianizing the world. Viewed the other way around, the growth of

the Christian mission of civilizing the world contributed to the growth

of slavery because the justications for slavery began to shift, in part, to

heathenism. Was not the African, a beast of burden, delivered by divine

Providence to labor for the benet of the noble and Christian Europe,

Graves (2001:25) writes of the emerging ethos. Whatever the case, clearly

an interactive relationship between Christianity and slavery existed.

Ideological justications for enslavement based on religious and mili-

tary grounds were followed by political action in the colonies that shifted

the basis from these grounds to a supposed racial origin. How did this

CS 32,4_f6_617-648I 11/13/06 1:46 PM Page 625

by Pepe Portillo on July 29, 2014 crs.sagepub.com Downloaded from

626 Paolucci

occur? Though Christians were not allowed to enslave other Christians,

European and Church law allowed the enslavement of non-Christians,

i.e., heathens. Fredrickson (1981:75) summarizes nicely: Empirically

speaking, the enslaved can be described as nonwhite heathens who were

vulnerable to acquisition by whites as a form of property, either because

they were literally captured in war or because a slave trade existed or

could be inaugurated in their societies of origin. On an ideological plane,

it was the combination of heathenism and captivity that was initially

stressed. But the ideological sphere would change. In the link between

theology and science, the Christian doctrine of the unity of man gave

way to polygenism, the doctrine of multiple origins and thus multiple

species (Graves 2001; Gould 1981). This inuenced the political-legal dis-

course as, inevitably, the issue of whether or not Christians could enslave

those who had converted arose. In the 1660s, a Virginia law said that

converted slaves could henceforth be held in bondage. Later, a loophole

was closed in 1682 when heathen descent rather than actual heathenism

was the legal basis for slavery in Virginia . . . the concept of heathen

ancestry was a giant step toward making racial dierences in the foun-

dation of servitude . . . The legal developments and semantic tendencies

that in eect made the disabilities of heathenism inheritable and inex-

tricably associated with blackness laid the framework for . . . societal

racism (Fredrickson 1981:7879). People could escape heathenism by

demonstrating they had converted to Christianity; they could not escape

heathen descent. This set the possibilities for racial slavery.

Since it was usually assumed that everyone with brown skin color in

the colonies had descended from Africa or was otherwise a heathen,

as the discourse shifted from a focus on ones religious spirit to ones

physical makeup the link between Christianity / heathenism and free-

dom / slavery was severed throughout the colonies, leaving physical

appearance as the lone criteria that marked Africans as the slave class.

Thus, the criterion of heathen ancestry was signicant ideologically

and legally in creating a physical-appearance / racial-category system of

enslavement. Baptism was no longer a reason for manumission and the

more Americanized African descendants became, the more the biblical

Pauline doctrine of obedience to masters as a Christian duty was imported

to the plantation and the colonies. The emerging Black / White dichotomy

led almost directly to a caste-like social-legal-political relationship. It

would probably confuse cause and eect, however to view the transition

to racial slavery as motivated primarily by color prejudice . . . planters

also had very strong economic and social incentives to create a caste of

hereditary bondsmen, argues Fredrickson. As slaves became a better

CS 32,4_f6_617-648I 11/13/06 1:46 PM Page 626

by Pepe Portillo on July 29, 2014 crs.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Race and Racism in Marxs Camera Obscura 627

long term investment in Virginia by 1660s, laws were changed to indi-

cate that conversion to Christianity did not require manumission. Blackness

became the criteria of a legal caste-like status. Thus, the original decision

to create what amounted to a racially derived status probably arose less

from a consciousness of racial privilege than from palpable self-interest

on the part of members of a dominant class who had been fortunate

enough to acquire slaves to supplement or replace their uctuating force

of indentured servants. This shift to racial slavery helped to cultivate

the belief that the normal status of dark-skinned people was servitude

(Fredrickson 1981:7880).

In this outline of the historical events, slavery in the West occurred before

the designation of skin color as a marker of slavery and before the devel-

opment of a specically racist ideology. The subsequent drawing of a color

line during the institutionalizing of slavery in the US colonies resulted

in dierential allotment of political, economic, and social resources, status,

and power (Du Bois 1903). This structuring of the color-line into the

political-economic system is why persists in a stubbornly intractable way.

Playing a covering role for capitalism, the inverted knowledge of race

and racism that marks modernity is often confused with the suspicions

and rancor between other groups in historically competing social sys-

tems, or what is known as xenophobia. Wallerstein (1983:7779) explains

the dierence:

What we mean by racism has little to do with the xenophobia that existed

in various historical systems . . . Racism was the ideological justication for

the hierarchization of the work-force and its highly unequal distributions of

reward. What we mean by racism is that set of ideological statements com-

bined with that set of continuing practices which have had the consequence

of maintaining a high correlation of ethnicity and work-force allocation over

time. The ideological statements have been in the form of allegations that

genetic and/or long-lasting cultural traits of various groups are the major

cause of dierential allocation to positions in the economic structures . . .

However, [this] came into being after, rather than before, the location of

these groups in the work-force . . . Racism served as an overall ideology jus-

tifying inequality.

Getting the causal mechanisms in an incorrect historical order encour-

ages illogical and empirically unsupportable positions. If racial ideology

came after rather than before the institutionalization of European and American

slavery, then the cause of slavery could not be racism. Popular concep-

tions that racism caused slavery are backwards. And when the history

of racial ideology and slavery are expressed as outcomes of the collective

consciousness of aggregated individuals, the systems that work on them

CS 32,4_f6_617-648I 11/13/06 1:46 PM Page 627

by Pepe Portillo on July 29, 2014 crs.sagepub.com Downloaded from

628 Paolucci

as an external and coercive forces are let o the hook. And, when the

causes of racism are obscured, methods to solve the problem are obscured.

The Philosophy of Science and Sociological Tautology:

Taxonomy and Bourgeois Ideology

The philosophy of science is concerned with what makes scientic knowl-

edge possible and the forms of reasoning scientists should accept. In their

observations, descriptions, and explanations, scientists try to separate out

identities (what things are or so they think or claim or assume) from

dierences (what things are not or so they think or claim or assume).

They are also concerned with creating useful conceptualizations so that

they can make logical comparisons of objects of knowledge in order to

make successful generalizations. Terms and analyses must work within

such constraints. Systematically created categories, relationally commensu-

rable and internally logical, make taxonomic categorization possible.

Here, the problem arises that a line of thought might make a tauto-

logical formulation by mistake. The logic of taxonomic analysis helps us

understand Marxs approach to tautological fallacies in sociological dis-

course.

Using observable and logical characteristics to dierentiate phenom-

ena is a key feature of scientic thought. The taxonomic method for

estimating relationships between phenomena, popularized by the botanist

Linnaeus, allows for the creation of a grid on which ranges of concrete

data can be displayed and analyzed. In one of his reections on his

study of systems of power and knowledge particular to modernity, Foucault

(1977:148149) remarked that in regards to taxonomy, the . . .

. . . drawing up of tables was one of the great problems of the scientic,

political and economic technology of the eighteenth century; how one was

to arrange botanical and zoological gardens, and construct at the same time

rational classications of living beings; how one was to observe, supervise,

regularize the circulation of commodities and money and thus build up an

economic table that might serve as the principle of the increase in wealth;

how one was to inspect men, observe their presence and absence and con-

stitute a general and permanent register of the armed forces; how one was

to distribute patients, separate them from one another, divide up the hospi-

tal space and make a systematic classication of diseases: these were twin

operations in which the two elements distribution and analysis, supervision

and intelligibility are inextricably bound up. In the eighteenth century, the

table was both a technique of power and a procedure of knowledge. It was

a question of organizing the multiple, of providing oneself with an instrument

to cover it and to master it; it was a question of imposing upon it an order.

CS 32,4_f6_617-648I 11/13/06 1:46 PM Page 628

by Pepe Portillo on July 29, 2014 crs.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Race and Racism in Marxs Camera Obscura 629

Foucault captures one role scientic thinking played in modern thought,

both internal to science itself but also extended through its relations with

other social institutions. Pitched at the level of the universal, taxonomic

analysis of human variation attempted to organize regular and concretely

observed characteristics, things that were supposed to be indicative of

key categories of the human condition in general. This form of knowl-

edge was inserted into the political-economic apparatus of modern society

and wielded in the racial programs developing in the modern world.

The technique of taxonomy is used to disperse a range of related phe-

nomena into meaningful categories based on varying specied criteria

that are supposed to dierentiate essential dierences and similarities,

i.e., meaningful in the sense that the criteria tell us something impor-

tant about the object in question and essential in the sense that the

characteristics the criteria target are necessary components of the objects

in question. To create a category, sensuously observable and measura-

ble dierences in the objects of study are used. Once abstract categories

are carved, comparison moves forward treating the two (or more) objects

as really qualitatively dierent facts. Among such rules for dividing obser-

vations into separate categories include the following: (1) categories must

be theoretically informed and based on non-arbitrary criteria; (2) crite-

ria are held constant throughout a table; and, (3) mutual exclusivity

(Suppe 1989).

2

In natural science, taxonomic analysis has proved useful for organizing

data and it is understandable that the human sciences would adopt it.

2

By a taxonomy (or taxonomic system) I mean a system of categories for classifying indi-

viduals on the basis of similarities; these similarities may be morphological, functional,

social, or whatever. A standard taxonomy for domain D is a nite collection of taxa (classes

of individuals in D) such that each taxon is assigned a unique category in a hierarchal

ordering of categories, and each individual in D belongs to exactly one taxon of each

category. More precisely, a standard taxonomy must meet the following conditions:

(1) There is a nite serially ordered sequence of taxonomic categories, C1. . . . . Cn;

(2) each taxonomic category Ci (1 I n) contains mi taxa, Ti, 1, Ti, 2, . . . . . ,Ti, mi;

(3) the Ti, 1, . . . , Ti, mi are each collections of individuals in D such that each member

of D is a member of exactly one Ti, j (1 j mi );

(4) all individuals in a given Ti, j (1 I n; 1 j mi ) must be members of the same

Ti + 1, k (1 I n; 1 k mi + 1).

Most biological taxonomies are taxonomies of this sort . . . Certain features of standard

taxonomies need to be emphasized. A given taxon of whatever taxonomic category will

always be a collection of individuals in D . . . Taxa of whatever taxonomic category are

collections of individuals groups on the basis of some similarity. A given taxon . . . is

dened by specifying the similarity characteristic of its members, the similarity by virtue

CS 32,4_f6_617-648I 11/13/06 1:46 PM Page 629

by Pepe Portillo on July 29, 2014 crs.sagepub.com Downloaded from

630 Paolucci

Both types of science possess discursive traditions that assume all observ-

able life can conceivably be dispersed onto a logical grid, one that includes

all the pertinent information relevant to any knowledge of life, either

today or in all of history.

Marxs materialism reminds us that knowledge and historical processes

always have been intertwined. In the capitalist world-economy, expan-

sion and growth across the globe is an inherent material tendency of the

system as a whole. Scientic knowledge about races and indigenous

peoples has followed the path of growth of this core-periphery relation-

ship (Wallerstein 1974a, 1974b). The destruction of pre-capitalist societies

became the data gathering grounds for the disciplines of anthropology,

geography, sociology, and social work. The subjects of these elds stand

as the real life empirical data used to justify the putatively circumscribed

distinctions between the disciplines. The racial ideology the disciplines

helped develop in the core was taken to the periphery and institutionalized

to a signicant extent.

However, it has never been obvious what criteria any one taxonomic

scheme succeeds or fails to establish (Graves 2001). Some are patently

absurd e.g. creating a scheme for all trees based on their number of

leaves; bark characteristics and annual leaf cycles have been much more

fruitful criteria. During capitalisms growth, taxonomies of human groups

were adopted, with illogical criteria but also with extraordinary eect,

one of which was to establish the belief that humans could be divided

into discrete subgroups based on apparent physical distinctions. An atten-

dant belief was that these groups could be ranked in a meaningful hier-

archical fashion. However, the stratied racial grid used in modernity

has never proven consistent over time and space. Rather it has been in

relative ux, gyrating with the movement of the world-economy. The

subsequent institutionalization of racial privilege and reward both

directly and indirectly rippled through a wide range of western thought

and social positions of power. A scientic racism produced by imperialism

of which they are classed together. The hierarchical nature of standard taxonomies

simplies the denition of a given taxon . . . Depending on what sorts of similarities are

chosen to dene taxa, a number of dierent standard taxonomies may be dened for a

given domain, D. For example, one may dene plant species on the basis of morpho-

logical similarity, genetic similarity, similarity of sexual parts, anity by common ances-

try, size, and so on. Some choices (e.g. length of body) may result in highly arbitrary

taxonomies. Since the recorded beginnings of taxonomy (Aristotle and Theophrastus),

the attempt has been made to distinguish such articial from natural taxonomies, and

throughout the history of taxonomy much theoretical dispute has centered on the issue

of what makes a taxonomy natural. Most accounts accept the intuitive idea that natural

taxonomies are those which classify in accord with the objective reality confronting us in nature, but

dier in what is required to do so (Suppe 1989:202204).

CS 32,4_f6_617-648I 11/13/06 1:46 PM Page 630

by Pepe Portillo on July 29, 2014 crs.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Race and Racism in Marxs Camera Obscura 631

and exploitation presented itself as neutral knowledge (see Harding 1993).

It has always been tautological.

A taxonomic analysis, which assumes the categories which data have

been divided into result in logically discreet groups based on meaning-

ful criteria, moves forward with the assumption that its categories are

not false divisions imposed on groups best left whole if their essential

identity is to be kept intact and meaningful. A sound taxonomic scheme

should not therefore split a natural unity in two and compare the results

as if they represent real dierences. The result is to mistake similarity

for dierence in one or another part of the equation, a tautological fal-

lacy. In such a tautological statement, one that is true by virtue of its

logical form alone (Websters), the formulation is its own proof and evi-

dence is rendered irrelevant, e.g., if A, then A, or, A = A. In mistaking

two objects that are qualitatively equal for objects that are essentially

dierent, an analyst is subject to assuming they are comparing two sep-

arate things that are in fact the same in their most important charac-

teristics, i.e., they think they are making an A versus B comparison when

they are in fact comparing A with A.

The form of tautology Marx cautions against is related to his camera

obscura warning and the reifying inuence it has on scientic knowl-

edge. For example, Marx (1982:140) states:

To M. Proudhon . . . abstractions, categories are the primordial cause.

According to him they, and not men, make history. The abstraction, the cat-

egory taken as such, i.e., apart from men and their material activities, is of

course immortal, unchangeable, unmoved; it is only one form of the being

of pure reason; which is only another way of saying that the abstraction as

such is abstract. An admirable tautology!

When a concept is assumed to capture universal human phenomena and

empirical evidence of its existence is gathered at qualitatively different

historical moments but is treated as representing qualitatively equal social

facts, then this evidence is likely to be interpreted as conrmation that

the concept indicates a transhistorical reality. This is a tautological and

thus fallacious formulation. Tautology is important to understand in con-

junction with implications of taxonomic thinking. Racial ideology devel-

oped in a taxonomical way but was done through the inverting eect

of the camera obscura. The outcome was a racist science condemned to

perpetual tautological fallacies.

The Great Chain of Being and Modern Racial Knowledge

Attempts to organize its experiences are probably as old as human cog-

nition itself. Many modern institutional discourses have accepted the

CS 32,4_f6_617-648I 11/13/06 1:46 PM Page 631

by Pepe Portillo on July 29, 2014 crs.sagepub.com Downloaded from

632 Paolucci

premise that taxonomic and hierarchical relationships exist which separate

groups from one another both between and within human, natural, and

cosmic orders. Originating as far back as Aristotle, one historical form

of knowledge in Western society that attempts to order reality is the idea

of a Great Chain of Being, a model of the universe that depicts the

place of matter, animals, and humans in it (Lovejoy 1936). This cosmology

depicts a hierarchical natural order organized in terms of increasing

levels of complexity among families of plant and animal groups. While

Aristotles original vision (Scala Naturae) was altered over time, the basic

conceptual premise was retained and set the foundation for both the

religious and the scientic discourse that would follow.

Religious discourse picked up on this way to order reality, tting nicely

as it did with Christianitys hierarchical vision of human life, with its

Godhead at the top, Jesus as his earthly representative, the Church as

carrying on Jesus ministry, and human and animal life next, all sitting

on top of physical nature, and then hell. The authority of the Catholic

Church over human society was built into this cosmology. To go against

church teaching or leadership was a crime against both oor and nis

natural order. This hierarchical vision set the stage for a moral order to

be applied to supposedly scientic taxonomies of the human species. With

hell below, earth in between, and then animals, humans, archangels and

then oor, the clear message was that the closer to the top one or ones

group, the greater their moral worth. This construct was imported to

early racist science.

The human sciences initially accepted the concept of race as a biologically

self-evident fact and placed humans in several dierent taxonomic schemes.

One scheme was based on the Christian versus heathen identity grafted

onto broad notions of regional and aristocratic identity. Equating European

identity with whiteness was not an initial taxonomic categorical form.

Like the African = slave / identity = racial group dynamic of early colo-

nialism, the invention of whiteness was caught up in class struggles.

Initially, identity was associated with families, clans, regions and some-

times country, with the categories of white or Caucasian taking time

to develop. Once conceived, white identity was extended to various

European groups groups previously organized in terms of ethnic identities

such as Italian, Polish, and Irish laborers as the American labor move-

ment needed increasing numbers of eligible members united in larger

unions during its struggles with capital (Gallaher 2002). It is in such ways

that the white / black racial dichotomy was a historical product wrapped

up in a socio-political-scientic complex. The relationship between changes

in the political-economic and the scientic spheres was regular though

CS 32,4_f6_617-648I 11/13/06 1:46 PM Page 632

by Pepe Portillo on July 29, 2014 crs.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Race and Racism in Marxs Camera Obscura 633

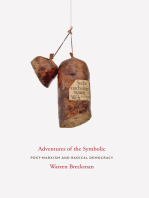

Man

Mammals

Whales

Reptiles & Fish

Octopuses & Squids

Jointed Shellfish

Insects

Molluscs

Jelly -

Fish

Sponges

Higher Plants

Ascidians

Zoophytes

Lower Plants

Inanimate Matter

Figure 3. Aristotles Great Chain of Being.

uneven, where science often followed political-economic dynamics but

also foundered on its own forms of logic.

One racial taxonomy in nineteenth-century biological sciences in the

West included the races of Anglos, Saxons, Celts, Teutons, American-

Negroes, Toltecans, Pelasgics, Hottentots, Nilotics, Peruvians, Australians,

and Barbarous Tribes, and others (Gould 1981). These racial categories

violate rules for valid taxonomic categorization, i.e., they are not mutually

exclusive nor do they use consistent criteria to dierentiate them. Over time,

biological scientists found that any criteria used in racial taxonomic

category construction displayed as much variation within supposed groups

as between them. As a result, even when theoretically informed criteria

have been provisionally established, subsequent empirical testing nds

that holding them constant produces considerable overlap and contra-

diction in measured cases, e.g., individuals of supposed racial groups

could be eligible for membership in two or more categories, a failure of

the rule of mutual exclusivity and therefore taxonomically invalid.

CS 32,4_f6_617-648I 11/13/06 1:46 PM Page 633

by Pepe Portillo on July 29, 2014 crs.sagepub.com Downloaded from

634 Paolucci

Figure 4. Rhetorica Christiana, Didacus Valads, 1579.

Source: By permission of The British Library, Shelfmark C. 107.e.3.

CS 32,4_f6_617-648I 11/13/06 1:46 PM Page 634

by Pepe Portillo on July 29, 2014 crs.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Race and Racism in Marxs Camera Obscura 635

Anthropologists once worked with at tripartite taxonomy composed of

Mongoloid, Caucasoid, and Negroid racial stocks. These categories

were supposed to be distinguished via skin color, eye shape, hair kink,

and other extraneous characteristics. Recognizing the impending problem,

anthropologists asserted that everyone is composed of some combination

of all three. These constructions are today thoroughly discredited. Criteria

as quality of eyes, nose, skin, and hair each socially and scientically

constructed as meaningful have no logical theory that justies using

them for taxonomic category construction. Further, such outward appear-

ances produce fallacious racial knowledge that often fails to comport with

biological measurement. For example, on the genetic level, two people

with very dierent outward appearances say one from Germany and

one from Somalia might be closer biological cousins than two people

with very similar outward appearance for example from Sudan and

Cameroon, or Germany and France, Japan and Korea. No matter what

criteria have been chosen, supposed racial groupings have never passed

scientic muster, making the establishment of a human taxonomy an

impossibility (for previous discussions of this problem in addition to the

literature already cited here, see: Montague 1942; Livingstone 1993; also

see literature about The Genome Project).

Skin colors do not exist as discrete categories, reminds Graves (2001:30).

In fact, race has no biological basis at all.

3

Race, as a biological fact,

3

Scientists have long suspected that the racial categories recognized by society are

not reected on the genetic level. But the more closely researchers examine the human

genome the genetic material encased in the heart of almost every cell of the body the

more most of them are convinced that the labels used to distinguish people by race

have little or no biological meaning . . . They say that while it may seem easy to tell

whether a person is Caucasian, African or Asian, the ease dissolves when one probes

beneath surface characteristics and scans the genome for DNA hallmarks of race.

Scientists say that the human species is so evolutionarily young, and its migratory pat-

terns so wide, restless and elaborate, that it has not had a chance to divide itself into

separate biological groups or races in any but the most supercial ways . . . Race is a

social concept, not a scientic one, said Dr. J. Craig Venter, head of the Celera Genomics

Corp. in Rockville, Md. We all evolved in the last 100,000 years from the same small

number of tribes that migrated out of Africa and colonized the world . . . Venter and

scientists at the National Institutes of Health recently announced that they had put

together a draft of the entire sequence of the human genome, and the researchers had

declared there is only one race the human race. Venter and other researchers say traits

most commonly used to distinguish race, like skin and eye color, are controlled by a

relatively small number of genes, and thus have been able to change rapidly in response

to environmental pressures. So equatorial populations evolved dark skin, presumably to

protect against ultraviolet radiation, while people in northern latitudes evolved pale skin,

CS 32,4_f6_617-648I 11/13/06 1:46 PM Page 635

by Pepe Portillo on July 29, 2014 crs.sagepub.com Downloaded from

636 Paolucci

is a social and scientic myth. Anthropologists and biologists have con-

cluded that . . .

the concept of race seems to be losing its usefulness in describing [human

genetic] variability . . . [I]t seems impossible even to divide . . . populations

into races . . . [ This] does not imply that there is no biological or genetic

variability among populations of organisms which comprise a species, but

simply that this variability does not conform to the discreet packages labeled

races or subspecies. For man the position can be stated in other words: There

are no races, there are only clines . . . Thus, although it is possible to divide

a group of related species into discrete units, namely the species, it is impossible

to divide a single species into groups larger than the panmictic population.

(Livingstone 1993:133134)

However, when taxonomy was applied to humans as a species, once sep-

arated into discrete groups and then compared as if dierent sub-species

were real, all conclusions in the racial sciences that followed were invalid

because of the initial tautological formulation. Race then, in addition to

racism, is a sociological-historical phenomenon.

Criteria for taxonomies social and scientic have changed from

religion, to region, to language, to lore, to physical traits. In reality, it

was not science but imperialist assumptions that informed racial cate-

gories. Upon invasion, if indigenous peoples survived, they became the

object of labor exploitation, Oriental objects of science (Said 1978),

or, in one memorable phrasing, the wretched of the earth: rst vic-

timized, then imprisoned and hated (Fanon 1965). The result has been

the creation and destruction of ethnicities across and within state bound-

aries in the global division of labor (for discussion see: Wallerstein 1983,

2003). As socially unequal groups were observed, their outward charac-

teristics were used to formulate biological hypotheses of dierence.

With no sound theory or data to inform them, the number of possible

racial categories has had virtually no theoretical limit, being established

the better to produce vitamin D from pale sunlight . . . If you ask what percentage of

your genes is reected in your external appearance, the basis by which we talk about

race, the answer seems to be in the range of .01 percent, said Dr. Harold P. Freeman

of North General Hospital in Manhattan. By contrast, scientists say traits like intelli-

gence, talent and social skills are likely shaped by thousands, if not tens of thousands,

of the 80,000 or so genes in the human genome. In Freemans view, the science of

human origins can help to heal any number of wounds . . . . Science got us into this

problem in the rst place, with its measurements of skulls and its emphasis on racial

dierences and racial classications, Freeman said. Scientists should now get us out

of it (Angier 2000).

CS 32,4_f6_617-648I 11/13/06 1:46 PM Page 636

by Pepe Portillo on July 29, 2014 crs.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Race and Racism in Marxs Camera Obscura 637

Bonnet - 1764 Lamarck - 1809

- Humans Worms

Mollusks

- Monkeys

- Bats

- Ostrich

- Birds

Fish & Reptiles

- Flying Fish

- Fish (Whales?)

Birds

Amphibious

Mammals - Eels

- Serpents

- Reptiles Whales

Hoofed Mammals

- Shellfish

- Insects

- Worms Mammals

Insects

Figure 5. Two Great Chains of Being From Early Biological Science.

at as little as two and as many as 63, perhaps more. The problem of

counting the number of races was created by the inability of nineteenth-

century biologists to properly identify phenotypic traits that had taxo-

nomic signicance . . . Before Darwin, the prevailing view in natural

science was that all biological traits had signicance because they were

the result of divine plan (Graves 2001:6566). Though older racial tax-

onomies seem archaic and nonsensical in retrospect, it is still common

to nd racial categorizations in surveys e.g., White, African-American,

Hispanic, Asian, Pacic Islander, Native American, and Other with

criteria ranging from skin color, to geography, to language, to time-

period. As a result, modern categories fail the taxonomical rule of con-

sistency much as they did a century-and-a-half before. It was / is not

science or self-evident biological dierences that determine(d) racial cat-

egories but politics and power. In the United States, for example,

Hispanic terminologically rooted in the criteria of language and geog-

raphy (i.e., inconsistency) was created by the US government and

wielded to unify everyone with a South or Central American heritage,

regardless of color, even if the peoples of a country such as, say

Argentina, Bolivia, or Peru do not dene themselves as Hispanic

(for a discussion on this see Gimenez 1989). Revealing the racism embed-

ded in the term, while Americans are extended license to stress their

European heritage, Mexicans typically are not, i.e., Hispanic is rarely

seen as European though it is clear Spain is as European as any

Anglo-Saxon nation, a real contradiction in modern racial ideology.

CS 32,4_f6_617-648I 11/13/06 1:46 PM Page 637

by Pepe Portillo on July 29, 2014 crs.sagepub.com Downloaded from

638 Paolucci

Figures 68. Racial Chains of Being.

If they are not based on real biological dierences, what has made

racial categories sociologically real? Racial categories have always reected

real relations of social inequality more so than signicant biological real-

ities. Goulds list above (i.e., Anglos, Saxons, Celts, Teutons, American-

Negroes, Toltecans, etc.) shows an early-middle period of imperialist

knowledge. When the development of the world-economy brought dierent

groups into a similar location in the global division of labor, they lost

their status as a racial group apart. As the various European groupings

the Anglos, the Saxons, the Teutons, etc. became white, their habits,

tastes, ideas, norms, and forms of knowledge became the standards by

which others were categorized and judged. The Mongolians, Chinese,

Malayans, and Polynesians became Asians and the Toltecans and

Peruvians became Hispanic. Such racial categories retain their mean-

ing for their audiences and users to the extent they reect real social

status and inequalities in power and wealth within the capitalist world-

system.

Source: From Graves, Jr., Joseph, The Emperors New Clothes. Copyright 2001

Joseph Graves, Jr. Reprinted by permission of Rutgers University Press.

CS 32,4_f6_617-648I 11/13/06 1:46 PM Page 638

by Pepe Portillo on July 29, 2014 crs.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Race and Racism in Marxs Camera Obscura 639

The Tautology of Racial Taxonomy

4

In the history of racial thinking, various beliefs emerged about how things

such as intelligence, morality, athleticism, sexuality, and even genital size

were associated with various groups (for discussion see: Hoberman 1997).

In one form of contemporary racial research, such characteristics are

measured and, after all conceivable control variables are statistically

accounted for, any resulting statistical dierences between groups

assumed, dened, and divided a priori as separate racial groups (e.g.,

white, black, Hispanic, Asian, etc.) are assumed to be accounted for

by biological-racial dierences. Though none have been studied, genes

emerge as causal factors by default. This is a tautological formulation.

Why? Such an inquiry is really asking two covert questions: Are our

racial categories justied? And, can athleticism (or intelligence, or brain-

pan size, or skin color . . . or genes) stand as criteria of real racial

dierence? The answer to the rst question is answered yes prior to data

collection by arbitrarily using cultural prejudice (e.g. skin color) to divide

groups into separate taxonomic categories. This allows almost any signicant

statistical correlation to count as racial in character once other variables

are controlled. The answer to the second question is thus also answered

yes by denition, i.e., athleticism (etc.), like skin color, is assumed

to be a meaningful marker of race. Translated: if racial dierences exist,

4

The argument in this section is informed by the work of Barbara Jean Fields (1990).

Source: From Graves, Jr., Joseph, The Emperors New Clothes. Copyright 2001 Joseph

Graves, Jr. Reprinted by permission of Rutgers University Press.

The facial angles of Petrus Camper: A, a young orangutan; B, a young Negro;

C, a typical European. From J. R. Baker, Race (Oxford: Oxford University

Press, 1974), 29.

CS 32,4_f6_617-648I 11/13/06 1:46 PM Page 639

by Pepe Portillo on July 29, 2014 crs.sagepub.com Downloaded from

640 Paolucci

Source: From Graves, Jr., Joseph, The Emperors New Clothes. Copyright 2001 Joseph

Graves, Jr. Reprinted by permission of Rutgers University Press.

then racial dierences exist. Researchers must argue that racial dierences

cause racial dierences, an empty scientic claim but one which has a

political usefulness that is readily apparent (Graves 2001:111 discusses

contradiction and tautology in common racial denitions).

Race, Racism and Marxs Political-Economy

For Marxs approach, the capitalist mode of production is not assumed

to be coterminous with either modernity or society. The capitalist mode

of production is the political-economic structure historically becoming

increasingly regular across time/space in modernity. This does not mean,

however, that Marxs method provides no tools for studying wider ques-

tions of social inequality not directly conceived as class relations. True,

Marxs work often does focus directly on political-economic issues. On

the questions of race, gender, nationalism, and religion, the reason Marx

ignores them, at least in his systematic writings, [is] because they all

predate capitalism, and consequently cannot be part of what is distinc-

tive about capitalism . . . Uncovering the laws of motion of the capitalist

mode of production, however, which was the major goal of Marxs inves-

tigative eort, simply required a more restrictive focus (Ollman 1998:348).

Nevertheless, there is nothing incompatible with a Marxist study of capitalism

The facial profiles from Robert Knox, The Races of Men. This figure shows

no transition between the sub-90 angle of the orangutan and the 90 angle

of the European. The Negro is inferred to have a sub-90 angle. Robert Knox,

The Races of Men: A Fragment (Philadelphia: Lea & Blanchard, 1869; reprint,

Miami, Fla.: Mnemosyne and Co., 1969).

CS 32,4_f6_617-648I 11/13/06 1:46 PM Page 640

by Pepe Portillo on July 29, 2014 crs.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Race and Racism in Marxs Camera Obscura 641

C

o

u

n

t

r

y

&

T

r

a

i

t

s

R

e

l

a

t

i

v

e

t

o

S

e

p

a

r

a

t

e

Y

e

a

r

E

x

a

m

i

n

e

d

E

u

r

o

p

e

a

n

s

H

e

r

i

t

a

b

l

e

?

E

n

v

i

r

o

n

m

e

n

t

?

S

p

e

c

i

e

s

?

F

.

B

e

r

n

i

e

r

F

r

a

n

c

e

,

1

6

8

4

G

e

n

e

r

a

l

N

e

u

t

r

a

l

?

?

N

o

G

.

W

.

v

o

n

L

e

i

b

n

i

z

G

e

r

m

a

n

y

,

1

6

9

0

G

e

n

e

r

a

l

N

e

u

t

r

a

l

N

o

Y

e

s

N

o

H

.

H

.

L

o

r

d

K

a

m

e

s

U

.

K

.

,

1

7

7

4

S

k

i

n

c

o

l

o

r

,

l

i

p

s

,

h

a

i

r

,

s

m

e

l

l

I

n

f

e

r

i

o

r

Y

e

s

N

o

N

o

J

.

F

.

B

l

u

m

e

m

b

a

c

h

G

e

r

m

a

n

y

,

1

7

7

5

S

k

i

n

c

o

l

o

r

,

l

i

p

s

,

h

a

i

r

,

s

m

e

l

l

N

o

r

a

n

k

i

n

g

Y

e

s

Y

e

s

N

o

S

.

T

.

S

o

m

m

e

r

i

n

g

G

e

r

m

a

n

y

,

1

7

8

4

G

e

n

e

r

a

l

N

o

t

a

l

w

a

y

s

i

n

f

e

r

i

o

r

Y

e

s

N

o

N

o

P

.

C

a

m

p

e

r

N

e

t

h

e

r

l

a

n

d

s

,

1

7

8

6

S

k

u

l

l

a

n

g

l

e

I

n

f

e

r

i

o

r

Y

e

s

N

o

N

o

G

.

B

u

V

o

n

F

r

a

n

c

e

,

1

7

8

9

S

k

i

n

c

o

l

o

r

,

s

m

e

l

l

,

i

n

t

e

l

l

e

c

t

I

n

f

e

r

i

o

r

Y

e

s

N

o

N

o

C

.

M

e

i

n

e

r

s

G

e

r

m

a

n

y

,

1

7

9

0

G

e

n

e

r

a

l

I

n

f

e

r

i

o

r

Y

e

s

N

o

N

o

C

.

W

h

i

t

e

U

.

K

.

,

1

7

9

9

S

k

u

l

l

s

,

s

e

x

o

r

g

a

n

s

,

S

k

u

l

l

s

s

m

a

l

l

e

r

,

Y

e

s

N

o

Y

e

s

s

e

x

u

a

l

i

t

y

s

e

x

o

r

g

a

n

s

l

a

r

g

e

r

S

.

S

t

a

n

h

o

p

e

S

m

i

t

h

U

.

S

.

,

1

8

1

0

S

k

i

n

c

o

l

o

r

,

g

e

n

e

r

a

l

I

n

f

e

r

i

o

r

N

o

Y

e

s

N

o

J

.

P

r

i

c

h

a

r

d

U

.

K

.

,

1

8

1

3

S

k

i

n

c

o

l

o

r

,

c

i

v

i

l

i

z

a

t

i

o

n

I

n

f

e

r

i

o

r

Y

e

s

Y

e

s

N

o

S

i

r

W

.

L

a

w

r

e

n

c

e

U

.

K

.

,

1

8

2

3

G

e

n

e

r

a

l

,

c

i

v

i

l

i

z

a

t

i

o

n

I

n

f

e

r

i

o

r

Y

e

s

N

o

Y

e

s

G

.

C

u

r

v

i

e

r

F

r

a

n

c

e

,

1

8

3

1

G

e

n

e

r

a

l

I

n

f

e

r

i

o

r

Y

e

s

N

o

Y

e

s

S

.

M

o

r

t

o

n

U

.

S

.

,

1

8

4

9

S

k

u

l

l

v

o

l

u

m

e

s

I

n

f

e

r

i

o

r

Y

e

s

N

o

Y

e

s

L

.

A

g

a

s

s

i

z

U

.

S

.

,

1

8

5

0

S

k

i

n

c

o

l

o

r

,

s

m

e

l

l

,

i

n

t

e

l

l

e

c

t

I

n

f

e

r

i

o

r

Y

e

s

N

o

Y

e

s

J

.

B

a

c

h

m

a

n

U

.

S

.

,

1

8

5

5

F

e

r

t

i

l

i

t

y

o

f

h

y

b

r

i

d

s

E

q

u

a

l

Y

e

s

N

o

N

o

J

.

N

o

t

t

U

.

S

.

,

1

8

5

7

G

e

n

e

r

a

l

I

n

f

e

r

i

o

r

Y

e

s

N

o

Y

e

s

G

.

G

l

i

d

d

o

n

U

.

K

.

,

1

8

5

7

G

e

n

e

r

a

l

I

n

f

e

r

i

o

r

Y

e

s

N

o

Y

e

s

P

a

u

l

B

r

o

c

a

F

r

a

n

c

e

,

1

8

6

2

S

k

e

l

e

t

a

l

I

n

f

e

r

i

o

r

Y

e

s

N

o

Y

e

s

S

o

u

r

c

e

:

F

r

o

m

G

r

a

v

e

s

,

J

r

.

,

J

o

s

e

p

h

,

T

h

e

E

m

p

e

r

o

r

s

N

e

w

C

l

o

t

h

e

s

.

C

o

p

y

r

i

g

h

t

2

0

0

1

J

o

s

e

p

h

G

r

a

v

e

s

,

J

r

.

R

e

p

r

i

n

t

e

d

b

y

p

e

r

m

i

s

s

i

o

n

o

f

R

u

t

g

e

r

s

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

P

r

e

s

s

.

T

a

b

l

e

1

.

E

i

g

h

t

e

e

n

t

h

a

n

d

N

i

n

e

t

e

e

n

t

h

C

e

n

t

u

r

y

N

a

t

u

r

a

l

i

s

t

s

o

n

t

h

e

R

a

c

i

a

l

T

r

a

i

t

s

o

f

t

h

e

N

e

g

r

o

.

CS 32,4_f6_617-648I 11/13/06 1:46 PM Page 641

by Pepe Portillo on July 29, 2014 crs.sagepub.com Downloaded from

642 Paolucci

and a concern with the inequalities and dynamics of race (and gender,

it might be added). Marx was trying to understand capitalism as a sys-

tem and while he did believe this system possessed a powerful inuence

on other social institutions, including discursive knowledge, his method

is not the economic reductionism it has been accused of being. Marxs

perspective brings to the study of race and racism not an economic deter-

minism but rather an understanding that capitalism possesses central

components that played a crucial role in constructing systematic racism.

Skin color alone had nothing to do with original racial categories,

even in the initial racist sciences. As forms of knowledge, racial cate-

gories have actually been based on political-economic time-space crite-

ria. As Wallerstein has continually stressed, a supposed races empirical

conditions of possibility rest not in a unique biology but rather at the

point in space and time when dierent peripheral peoples were incor-

porated by imperialist powers into the worldwide division of labor in the

capitalist world-economy. This is by no means a trivial matter. It was

and is of momentous importance for the subsequent relationships of hier-

archy and subordination involved in the history of racism. But it stands

to ask: Was this racism uniquely European in heritage? Is historical

racism something that should be pinned on European thought for devel-

oping and spreading? Was capitalism a white-supremacist event because

of the ideas of its progenitors? What is to blame? Capitalism? Capitalists?

European elites? European thought?

European xenophobia was no more extraordinary than the disdain

held by elites for the average person in other social systems. While it

was the ruling classs ideology of superiority that was imported into the

relationships they forged with their own working classes and the indigenous