Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Burma Through Western Novels

Transféré par

maayera0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

35 vues13 pagesJSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content. "If you want to write a real Burmese story", U Nu once told an audience of Burmese writers, "you "must know the real Burmese background" fiction provides a popular entry way for the "average" reader to reach beyond his normal range of knowledge and imagination.

Description originale:

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentJSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content. "If you want to write a real Burmese story", U Nu once told an audience of Burmese writers, "you "must know the real Burmese background" fiction provides a popular entry way for the "average" reader to reach beyond his normal range of knowledge and imagination.

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

35 vues13 pagesBurma Through Western Novels

Transféré par

maayeraJSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content. "If you want to write a real Burmese story", U Nu once told an audience of Burmese writers, "you "must know the real Burmese background" fiction provides a popular entry way for the "average" reader to reach beyond his normal range of knowledge and imagination.

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 13

Department of History, National University of Singapore

Burma through the Prism of Western Novels

Author(s): Josef Silverstein

Source: Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 16, No. 1 (Mar., 1985), pp. 129-140

Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of Department of History, National University

of Singapore

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20070844 .

Accessed: 29/04/2014 02:04

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

.

Cambridge University Press and Department of History, National University of Singapore are collaborating

with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Southeast Asian Studies.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 14.139.69.54 on Tue, 29 Apr 2014 02:04:49 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Burma

through

the Prism of Western Novels

JOSEF SILVERSTEIN

"If

you

want to write a real Burmese

story",

U Nu once told an

audience of Burmese

writers, you

"must know the real Burmese

background".

It is advice that

applies

to

foreign

as well as

indigenous

writers

and,

in most

cases,

non-Burmese writers have

followed it. The recommendation is

important

because fiction

provides

a

popular entry

way

for the

"average"

reader to reach

beyond

his normal

range

of

knowledge

and

imagination;

it is more

likely

that he will have read a novel or short

story

rather than a

history

or a

scholarly

work and it is from this source that he will have formed his ideas

and

adopted

his

stereotypes.

Thus,

it is

necessary

that the available literature is

good,

that it is accurate in its

descriptions

of the locale and the behaviour of the

people,

that

it catches the nuance of local

speech

and

expression,

that it reflects the

psychology

of

the

subjects

when it discusses them rather than

imputing

alien

speech,

values,

and

attitudes.

Burma's Western

interpreters

have,

in the

main,

tried to

present

accurate

descriptions

and true

representations

of the

people

and the

country.

Most of the writers have

lived in Burma for a

period

of time and have travelled

fairly widely

in the

countryside.

Although

the stories that

they

tell are more

likely

to interest non-Burmese audiences

than local

ones, nevertheless,

their observations and

descriptions together

with their

presentation

of local conditions and the

problems

of

change

contain rich

insights

from

which all

?

indigenous

and alien alike?can benefit.

Any survey

of this

genre

of Burmese fiction will reveal that the

subject

matter and

themes that interest most non-Burmese writers are the

problems

of the Westerner

?

and in one

case,

the

Japanese

?

in a

strange

and distant land.

They

focus more on

how the non-Burmese survive and remain untainted

by

their alien environment than

they

do on how Westerners

adapt

to new circumstances and

develop

new and broader

perspectives.

In most

respects

their novels

depict

the clash of cultures with neither

group

really being

affected

by

the other. A few

writers,

especially

those with

missionary

backgrounds, emphasized

the

triumph

of Western culture and Christian values. The

great

event for most who have written about Burma in the last

thirty years

was World

War II and how

Europeans, trapped

in

Burma,

or

Japanese,

left after the war's

end,

either

escaped capture

or

responded

to the

victory

of the Allies.

Few,

if

any,

have

attempted

to write about

independent

Burma and the

problems

its

people

faced from

civil

war,

military

rule,

and isolation in a world

growing

closer

through

travel and

communications.

American writers have shown a

particular

interest in the

minority peoples

of

Burma,

especially

the Karens and the Kachins. Some of this interest stems from the fact that the

writers were

Baptist

missionaries who lived and worked

amongst

the Karens while

others were American

Special

Forces who

fought alongside

the Kachins in the war.

Here,

the writers either treat the minorities as

primitive peoples benefitting

from

129

This content downloaded from 14.139.69.54 on Tue, 29 Apr 2014 02:04:49 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

130

Josef

Silver stein

conversion to

Christianity

or as noble

savages

from whom modern Western man can

recover the eternal truths about himself and his

relationship

to nature.

Only

a few Western novelists have tried to write historical novels in which the

subject

matter is

exclusively

Burman. Part of the reason for this is that the writers are not

Burmese scholars and most are unfamiliar with the

language

and local literature. The

few

attempts

that were successful were so because their authors either had the

necessary

knowledge

or

they

had

access to a

body

of documents that allowed them to reconstruct

history

in a fictional form and tell a Burmese and not a Western

story.

With the

exception

of the historical

novels,

Western writers have not

placed

Burman

heroes at the center of their stories.

When,

on

occasion,

a

Burman is offered as a

major

figure

in the

narrative,

he is not

typical. Usually,

he is a member of the

?lite,

has had a

Western

education,

speaks English fluently

and

may

have lived

part

of his life in

Europe.

Thus,

he is able to fit

easily

into a

European

environment and be absorbed

by

it rather

than

move the

story

into a Burmese arena.

Also,

one finds that where a

non-European

is an

important

character he

usually

is

an

Anglo-Burman

or

Anglo-Indian

and is a

bridge

between East and West. A second characteristic of this

body

of fiction is that the

story

is

placed

in a rural rather than an urban

setting.

This allows the writer to

give long

and

detailed

descriptions

of the

country

and the

people

and to

provide

a context for the clash

of cultures as the

tiny

"island" of

Europeans struggle

to create what

they

believe to be a

corner of

England

in the colonial

outpost. Burma,

in the

main,

is

background

and

many

of the

plots

and characters could

just

as

easily

fit into the Indian or

Malay

scene.

For all

practical purposes,

the end of colonial rule in Burma

brought

an end to

Western writers

using

the nation as a locus for their stories or its

people

and their

problems

as their

subject

matter. There are a number of reasons for this: the war and

independence

saw the end of a

permanent expatriate population

from which so

many

of the earlier writers were

spawned;

the nation

discouraged foreigners

from

coming

through

limitations on both visits and

residence; few, except

scholars and

diplomats,

knew

enough

about the

country

to

say

more than what could be

gleaned

from

past

works

of literature or travel

books,

which in the main were drawn from limited

secondary

sources;

there were too

many

other

places

in the world to write about where one did not

have to know the

language,

customs,

or the

people

from

personal experience.

If new

novels

are not

being

written

by

non-Burmese

writers,

there at least is a

corpus

of old

ones which are useful for what

they

have to

say

about the

country,

its

people

and the

Westerners who lived

amongst them;

at least two still are

widely

read and

help shape

attitudes and values of readers toward Burma and its

people.

In answer to U

Nu,

the

Burmese

backgrounds

are real even if the novels do not

always

tell real Burmese stories.

There

are four

major

themes which unite the novels of Burma: colonial rule and

its

impact

on

Europeans

and Burmese

alike;

religion

and the clash of

culture; war,

especially

World War

II;

and Burmese

history

at moments of

great change.

Probably

the best known work on Burma is

George

Orwell's Burmese

Days.

In

it,

the

author

provides

his reader with

a

damning

indictment of

imperialism

as a

corrupting

influence

on the

Europeans

who serve it. Shrouded in the

myth

of the "white man's

burden",

they

claim the

right

to rule and

special privilege.Yet,

beneath the

mantle, they

are

ordinary Englishmen,

no better or worse than their

countrymen

who remain at

home.

However,

once

they

arrive in the

colonies, they change

and Orwell sees such

banal characteristics as

pretentiousness

and

arguing, scheming

and boredom as the

elements of colonial life that transform these otherwise

ordinary

individuals into

unpleasant,

and in some

cases,

dangerous sojourners

in a

foreign

land.

This content downloaded from 14.139.69.54 on Tue, 29 Apr 2014 02:04:49 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Burma

through

Western Novels 131

Orwell draws the reader's attention to the fact that in

Burma,

as elsewhere in the

East,

the club is the center of

European

life. It

represents

an exclusive world where

entry

depends upon

one's skin

colour, race,

nationality,

and

position

in the

ruling

?lite.

Despite

efforts of liberal

administrators,

located at

great

distances in the

capital

cities,

to

open

these clubs to

"natives",

the denizens scheme to remain

exclusive,

believing

that

any

crack in the wall of their closed

society

would create a flood and

they

would be lost in a

sea of local

people.

At the root of their

reactionary

stance was their belief that

change

would diminish their material standard of

living

to a level

probably

no better than if

they

had remained in

England

and it would

destroy

their

pr?tentions

as members of a

ruling

class.

Other novelists who have written of Burma have examined the club and its

members,

but no one has been as harsh as Orwell. Maurice

Collis,

who is better known for his

histories and

biography,

than for his

fiction,

presents

a less

damning

view in Sanda

Mala;

but he too finds

very

little that is

redeeming

in it or its members.

Here,

as in Burmese

Days, Europeans gather

to

drink,

gossip,

and

plot against

all outsiders.

Although

the

period

about which Collis

writes,

the

early 1920s,

is more

pacific

than the next

decade,

the focus of Orwell's

novel, nevertheless,

the

behaviour, values,

and attitudes of the

members is

nearly

the same. In Sanda

Mala,

the

Europeans expect

the

government's

representative

to

uphold

them even when

they

have cheated their

indigenous

business

rivals. When officials do

not,

the club members are

prepared

to

appeal

to

high quarters

in order to

triumph

or

plot

the downfall of all who stand in their

way.

If the club is the locus of

action,

it is the members who tell and act out the

story

of the

corruption

of colonial rule. Orwell created a number of

stereotypes

that successive

authors used. There is the District Commissioner and

Inspector

of Police who are

there to maintain law and order. While

they

are

expected

to deal

even-handedly

with

Europeans

and natives

alike,

as

representatives

of a

paternalistic government,

their

sympathies

are with the

expatriates

who

represent

British business

?

timber

extraction,

mining,

rice

milling,

etc. It is

amongst

the latter that the reader finds the clearest

examples

of racists and defenders of

privilege.

It also is

amongst

the latter that one finds

the

outsider,

the individual who

rejects

the

system

and even

fights

to

change

it. Orwell's

hero,

Flory, employed

in timber

extraction,

hates himself for

sharing

the false

lifestyle

of British

society

in

Burma;

yet,

he is too weak to abandon it or

fight permanently

against

it in order to force

change. Flory,

unlike his fellow

countrymen,

finds and

appreciates

the natural

beauty

of the

country

and the charm of

many aspects

of its culture.

To

bridge

the

dichotomy

between the

lifestyle

he dislikes and the

country

he

loves,

he finds

friendship

in an

Indian

doctor,

solace in

drink,

and

pleasure

in the charms of his

Burmese mistress. He has the

potential

for

leadership

and demonstrates it when the club

is under

physical

attack,

but when he must face his fellow club members and seek their

approval

for the

membership

of his

friend, Veraswami,

the Indian

doctor,

he fails. In the

end the

conflicting

forces and treacherous

plotting

of his mistress and a

Burmese

magistrate

overwhelm and

destroy

him and he finds

escape

in suicide.

In other novels of

Burma,

there are

many

variations of

Flory. Patterson,

in H.E.

Bates,

The Jacaranda

Tree,

is a

stronger individual; he, too,

is

part

of the commercial

establishment and like

Flory,

is involved in timber. Unlike

Flory,

he finds both

pleasure

and love with his Burmese mistress and does

nothing

to hide his

relationship

with her

from the others.

Also,

unlike

Flory,

he

rejects

the club and lives outside its walls and its

rules.

Patterson,

like

Flory,

rises to the

challenge

of

danger

?

this time from the war

?

by organizing

and

leading

the

Europeans

out of Burma as the

Japanese

advance.

This content downloaded from 14.139.69.54 on Tue, 29 Apr 2014 02:04:49 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

132

Josef

Silver stein

In Cecilie Leslie's The Golden

Stairs,

a third variation of

Flory

is reflected in the

character of Hamish. This

time,

the unorthodox and nonconformer to the club ethic is

the

Superintendent

of Police.

He,

unlike

Flory

or

Patterson,

is

obliged

to follow orders

from above and

carry

them out with

impartiality.

However,

when he sees the contradic

tion between the

commands,

which were issued from

afar,

and the realities

on the

spot,

he

too,

rises to the

challenge

of war and does what he thinks is

right

and

good regardless

of the rules and orders.

Against

these

opponents

of the

system

stand the defenders and

perpetuators.

In

Burmese

Days,

it is Elizabeth Lackersteen. She came to Burma

mainly

because her

chances for

marriage

and social advancement were

poor

or nonexistent. In the male

dominated

society

of the

club,

her faded

beauty

is revived and she is

sought

after

by

the

lonely

men of rank or

position.

For

Orwell,

she

represents

the

tragedy

of the colonial

system

?

the

never-ending

stream of new recruits who

accept

its rules and

keep

it

alive. In The Golden

Stairs,

Monica

Wadley

is the

counterpart

to Elizabeth.

She, too,

comes from mean circumstances in

England

and sets her

goal

on

succeeding

in the new

opportunity

that Burma offers. Monica is older than Elizabeth and is more determined

in her

quest.

She, too,

is faced with a

greater challenge

?

the

collapse

of

empire

and the

irregular flight

of the

ill-prepared Europeans

from the

advancing Japanese.

One is

unlikely

to read a more

devastating critique

of this

type

than in the author's account of

the unreal life at the hill-station in

Maymyo

where its

emptiness

and

pretentiousness

are

starkly

drawn and

vividly portrayed against

the

background

of the

retreating

British

army

and the

disintegration

of

empire.

Bates introduces

a third variation of Elizabeth in The Jacaranda Tree. Connie

McNair,

like the other

two,

came to Burma to find a better

life,

but unlike Elizabeth

or

Monica,

she is dominated

by

her mother and therefore cannot realize her own

potential

until it is

too late. The

savage

death of her mother

brings

freedom but not

marriage

because illness

and death overtake her before she can blossom.

It is

through

the characters and the club that the reader learns that it is the

European

and not the Burmese who are

corrupted by

the

political system

and that the

Burmese,

in their

isolation,

remain

relatively

untouched

by

it.

By concentrating

on hinterland

rather than the

city,

the authors fail to

explore

the direct

impact

of the colonial

system

on the local

people

who must serve it. How it alters and arouses them and the

impact

it

leaves on their lives and

thought

is an area

unfortunately

none of the Western writers

explore

or even consider.

If the novel is to be the source of one's

knowledge

of the Burmese and their

culture,

the several that have been

published

offer a

variety

of views. In Burmese

Days,

Orwell

looks

closely

at

particular

Burmans and finds

very

little to

say

about them that is

positive.

Of the four he

presents

in

detail,

Po Khin

?

the

magistrate

?

is the villain who not

only

understands the colonial

system

and its weaknesses but is able to

manipulate

it and its

servants,

European

and native

alike,

to achieve

promotion,

wealth,

and

membership

in

the club.

By focusing

on the

thought

and action of Po

Khin,

Orwell

presents

a harsh

picture

of Buddhism

as an

opportunistic

faith that one can use for one's own ends.

Po Khin

piles

one evil deed

upon

another

as he

acquires

power

and

position

with the

clear intention of

using

his

ill-gotten gains

to make

religious

merit in his

declining years.

Even

though

he fails to achieve his

ends,

the

negative impression

of Buddhism remains.

Ma Hla

May, Flory's

mistress,

is the classic

example,

in

any culture,

of the woman

scorned who

gets revenge.

Ma

Khin,

Po Khin's

wife,

on the other

hand,

believes in her

faith and worries about her husband's fate because she is aware of all of his evil deeds.

This content downloaded from 14.139.69.54 on Tue, 29 Apr 2014 02:04:49 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Burma

through

Western Novels 133

Finally,

there is

Maung

San

Hla,

or as he is

called,

Ko S'la. As

Flory's

manservant he is

wily, pragmatic,

amoral,

and devoted to his

employer.

Given the situation where

Flory

is

away

a

good

deal of the time

and,

when he is

home,

his lack of interest in his house

hold,

his

drunken-state,

and his

long

association with Ko

S'la,

the manservant is allowed

to act in

ways

that are more universal than

Burmese,

and one should not

generalize

Burmese

behaviour, culture,

or values from the

things

he does or

says. Although

Orwell

presents,

in

general,

a

positive

and accurate

picture

of some

aspects

of Burmese

life,

the

overall

impression

of the faith and the

people

is

very negative.

An

opposite

view of the

Burman,

his

religion

and

society,

is offered in Ethel Mannin's

The

Living

Lotus. Here Burman

society

in rural

upper

Burma is described in

loving

detail. The

people

are shown

realistically

with

warmth,

jealousy,

and

treachery being

as

much a

part

of their lives as one finds in

any

other culture. Buddhism and its rituals are

described with care and

understanding.

The

people

who

emerge?the

heroine

Mala,

an

Anglo-Burman girl

who is raised

by

a Burman

family during

the war

years,

Ma Hla

her foster

sister,

and others

?

are shown in a traditional

setting

that is detailed and

believable. The author makes

many digressions

in order to

explain aspects

of the faith

and

ritual,

which would do credit to an

anthropologist

or

sociologist.

Mannin also

provides

a clear

picture

of the clash of cultures as the heroine is seen

first,

in her

early

years, living

in a home where the cultures of her

parents

are in

conflict; then,

through

an

accident of

war,

she is

brought

to a Burman

village

and raised

by

her

adopted family

as one

of their own.

Finally, through

a

trick,

she is taken to

England

and there her father tries

to

supplant

her Buddhism with

Christianity.

In the end she chooses to

give up

her

English heritage

and return to Burma and the husband and

family

she left. In this

novel,

the reader is

challenged

to consider the Buddhist faith as

practised by genuine

believers

against

the Christian faith and its misuse

by

those who

represent

it. A careful

reading

of

this book will not

only provide

entertainment but a

great

deal of information about the

Burman

people

and their culture.

The theme of

mixing

cultures is

repeated

in several of the novels of Burma. In Sanda

Mala,

Nat Shin

Me,

the

heroine,

is the

daughter

of a Burman

prince

and a Shan

princess

who has been educated in the West.

Although

betroth to a

Burman,

she is

unhappy

with

the man her

parents

have chosen.

Thus,

when the

hero,

Mangin,

arrives from

England

to

paint

the

portraits

of her

parents,

she acts first as a

bridge

between her

parents

and

him

and,

gradually,

falls in love. Her

mother,

Sanda

Mala,

not

only approves

but

manipulates

events so

that,

in the

end,

her

daughter

is able to

marry Mangin.

Her

father,

who

speaks

no

English,

remains in the

background.

While the author

gives

details of his

life and

personality,

the father never

emerges

as a central

figure

in the

way

his

English

educated

daughter

and

worldly

wife do.

A less make-believe version of the

European-Burmese

union is found in The Golden

Stairs,

where Tom

McNeil,

a

forestry

officer and Hla

Gale,

a

wealthy

Burman woman

are married and their

son, Ken,

is raised first as a Burman Buddhist and then sent off to

school in

England only

to return to his

family

as war

envelops

Burma. He

represents

the

ambivalence and confusion of the

person

of two cultures in a

period

of

change.

Ne vil

Shute

presents

the

problem slightly differently

in The

Chequer

Board.

There,

the

European

is at best an

agnostic;

the author allows the British

airman,

through living

with

a Burman

family

and

falling

in love with one of its

members,

to be drawn into Burmese

life and to understand and

respect

it.

Here, too,

the reader is

given

some fine detail of

the faith and its

place

in Burmese life.

There is one other non-Burman

tragic type

to be found in the environment of the

This content downloaded from 14.139.69.54 on Tue, 29 Apr 2014 02:04:49 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

134

Josef

Silver stein

Burma

outpost,

the Indian and the

Anglo-Indian. Again,

it is Orwell who draws a bitter

picture

of

Veraswami,

the doctor

living

on the

edge

of the

European

enclave and

Burmese

society,

without

membership

in either. He

represents

the Asian who succeeds

in

mastering

Western science

by becoming

a doctor and is convinced of the

superiority

of Western culture and literature. He is like those

nineteenth-century

Indians who

manned the ranks of the infant Indian

Congress Party

and saw the West as

superior

to the

East. Veraswami's

tragedy

is that his skin colour and race bar his

entry

into the "sacred"

club while at the same time he is

rejected by

the local

population amongst

whom he lives.

In The Jacaranda Tree the author

provides

the reader with an

Anglo-Indian

nurse,

Miss

Allison,

who while

accepted nominally by

the

European community

never

really

feels a

part

of it.

Initially,

she

joins

with the small band of

Europeans

as

they

seek to

escape

to India. But as the caravan moves

forward,

she realizes that she is not a

part

of

the

European group

and India is not her home. She deserts the

group

and

disappears

amongst

the local

population,

who are left behind. The author

gives

no

clue whether or

not she is successful either in

surviving

or

being accepted by

the

people.

The

Anglo

Indian,

like the

Indian,

was never

accepted by

the Burmese and when

independence

came to

Burma,

in

1948, many

in both communities left the

country

either for

England

or India. Those who remained behind either tried to

submerge

themselves into Burmese

society

or resolved to remain

permanent

outsiders and retained their

identity

and their

culture.

For most of the authors who wrote of the

war,

heroism and

tragedy

were the twin

themes

they repeated

most often. Bates wrote two novels about Burma in World War

II,

The Jacaranda Tree and The

Purple

Plain. In the

former,

he dwells

upon

the character

of

Patterson,

the

hero,

who rises to the

challenges

the war

presented

and

triumphs

because of his

good

common

sense,

personal courage,

and an

unswerving

devotion to

the

goal

of

escape.

In the

end,

he achieves his

goal

while those who desert his

leadership

meet

tragic

ends. In The

Purple

Plain,

Bates created a

counterpart

to Patterson in

Squadron

Leader

Forrester,

whose

plane

crashes and who assumes the

leadership

of the

survivors;

against impossible

odds,

he leads them to

safety.

Heroism is so central to the

novel that it could have been located

anywhere

as the

setting,

the

people,

and the

country

are

only

incidental to the

story.

Even the Burmese

village,

where Forrester finds

love,

is a Christian

village

and, therefore,

is

very atypical

of Burma.

One of the best and least well-known stories of the war in Burma is The Golden Stairs.

Again,

the central theme is

escape

from the

Japanese.

A

group

of

Europeans,

Indians,

and

Anglo-Burmans

encounter a

variety

of

dangers

as

they pass through

the heart

of Burma to the

deadly Hukong Valley

to reach

safely

in India. The author writes

accurately

and

sensitively

of the

country

and its

people

as the

Europeans

and their

retainers make their

way

out of the

country.

In

choosing

to focus on

the last

leg

of the

escape,

the author is able to

give

a vivid

feeling

of the remote areas of northern Burma

where few Westerners have been. The "Golden Stairs" is the final test for the evacuees

as

they

descend

through

a

quagmire,

which the rains have made of the thousand

steps

of

clay

that divides this area of Burma from India. The book

provides

vivid and accurate

descriptions

of the human

struggle along

this route because the author relied

upon

diaries

and interviews with evacuees as the main sources of her information. The

story

of the

exodus allows her to introduce actual historical events and characters. It also

permits

her

to introduce a new character not found in the other literature of Burma. Daw Hal

Palai,

the sister of Hla Gale and the aunt of

Ken,

is the

bridge

between the Nationalists of the

1930s and the Burmese revolutionaries of the war

period.

She is

represented

as

having

This content downloaded from 14.139.69.54 on Tue, 29 Apr 2014 02:04:49 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Burma

through

Western Novels 135

been a follower of

Saya

San in the futile revolt in the

early

1930s and a

supporter

of the

Burmans who saw the war as a means of

achieving

the nation's

independence.

The

presence

of the Nationalists and Daw Hal Palai

provides

one set of

pulls upon young Ken,

which are counterbalanced

by

those exerted

by

Monica

Wadley,

Ken's

father,

and the

other Christian

Europeans. Again,

the clash of cultures creates the tensions within the

characters and

gives depth

and

meaning

to the

story.

If Bates and Leslie were concerned with the war's effect on the

Europeans,

there is an

important

novel about its

impact

on the

Japanese.

Michio

Takeyama's Harp of Burma,

is

truly unique.

It was written

by

a man who never visited

nor,

before he wrote the

novel,

studied Burma.

Nevertheless,

he

produced

an

exceedingly

accurate

picture

ofthat land.

More

important,

he

gives

rich

insights

to the

meaning

of Buddhism.to the

people

of

Burma. He wrote his

story

from the information he

gleaned

from the soldiers who were

repatriated

from Burma. It is directed at the

Japanese

who,

in the first

years

after the

war's

end,

were

trying

to understand

it,

their

defeat,

and themselves.

Like the novels about the British in

Burma,

Harp of

Burma is about the

Japanese

in

Burma at the war's end.

Throughout

the earlier

days

of

combat,

a

company

of soldiers

were

inspired by

one

among them,

Corporal

Mizushima,

who led them in

song through

the

accompaniment

of a Burmese

harp,

which he had

taught

himself to

play.

When the

war ended and his

company surrendered,

he

escaped,

and

having

donned the

yellow

robe of the local Burmese monks he

gradually

learned its

meaning

and found his

life's mission

?

to find and

bury

the bodies of the fallen

Japanese

?

and

gives up

the

opportunity

of

returning

to his homeland.

Unlike the

Europeans writing

about themselves in the environment of

Burma,

but

really

untouched

by it, Takeyama

looks at Burma's

impact upon

the

Japanese

who went

there as soldiers and

stayed long enough

to be affected

by

their

experiences

with

Burmese culture. One

gets

to know rural Burma and its

people through Japanese eyes

and

especially gains

a

positive

view of Burmese Buddhism. Unlike

Orwell,

Takeyama

does not see Burmese character

differing

from Buddhist

teachings.

The

question

he asks

at the end is a universal one: cannot

everyone

learn from the Burmese and recover a bit

of their humanness from their material and scientific

preoccupations?

It is a

question

neither Orwell nor

any

other writer about Burma ventured to ask.

Patrick Cruttwell

provides

a different kind of war novel and

insight

to Burmese life.

In A Kind

of Fighting,

his

hero,

Lin

Soe,

is a

thinly disguised

version of Burma's national

hero,

Aung

San. If read

only

as a novel about the war's

impact upon Burma,

it

provides

an

interesting story

of a

young

man who knows that he is destined for

greatness

and

early

death. As a fictionalized version of modern Burmese

history

it is a

poor

imitation of life.

In order to

develop

his

narrative,

the author

places

himself at the center of the

story,

as

the link between Lin Soe and the world. He

provides

a number of

snapshots

of the man

and his time: the

university

where Lin Soe

studies;

in

hiding

where the author and the

hero meet and

plan

for

unity

between the Burmese Nationalists and the

British;

the

hero's final hours. But

through

all of this the reader learns little about

Burma,

the

rising

generation

of nationalist

leaders,

or

the values and ideals of the

people.

Unlike in the

other novels noted

earlier,

in this one the author is the man in between. As the univer

sity professor,

he teaches the hero about the ideals and values of the

West; later,

as the

agent

for the

Allies,

he is called

upon

to return to wartime Burma and convince the hero

to

join

forces with the British in the final

stages

of the war.

Finally,

he is asked

by

the

Burman

Nationalists,

who succeed Lin

Soe,

to write of their fallen leader so that

they

can

learn more about him.

Thus,

the author sees himself both

instructing

the Burmese about

This content downloaded from 14.139.69.54 on Tue, 29 Apr 2014 02:04:49 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

136

Josef

Silver stein

the West and about their own

hero,

while he informed the British and the Allies about

the new Burman man whom

they

will have to deal with at war's end.

Overall,

the novel

fails to

give

a clear and consistent

picture

of Burmese

society

in the throes of war and a

highly unlikely picture

is

presented

of the nation's future hero and those who

supported

him. It does

represent

an

original attempt

to create a

truly

Burman hero

who,

although

a

product

of Western

education,

never

really

loses his national

identity.

It also

departs

from the other novels of modern Burma in that it treats the hero and his

supporters

as

secular

figures.

This is not the

story

of

Aung

San

; instead,

it is a view

through

a

prism

that

distorts

reality

as it allows little of the man's

strength

of character and

unswerving

devotion to an ideal to shine

through.

From the

perspective

of a

purely

American war

story, probably

the best that has been

published

thus far is Tom Chamales' Never So Few. The locale is in northern Burma

where a small

group

of American forces live and

fight alongside

the Kachins. This

special

group

of American

fighting

men is the forerunner of the modern CIA who work behind

the lines with local resistance

fighters.

The author

provides

rich

descriptions

of Kachin

life

and,

especially,

the Kachin

fighting

man. The

Americans,

who make the rules that

they

live

by

as

they go along, anticipate

the

cruelty

and

inhumanity

in war the American

public

will come to know and feel a

generation

later as national shame for their

behaviour at

My

Lai. Con

Reynolds

is the American hero in Never So Few. In his war

deeds,

his

intelligence,

and his

revenge,

he is

larger

than life. He drinks

excessively,

he

administers

justice by

a code he makes

up

as situations

arise,

and

fights

to win

regardless

of the method or tactic. He stands in awe of

Nautaung,

the Kachin whom the author

idealizes as an

example

of native

nobility.

The Kachins and their

way

of life not

only

stimulate the author's and the hero's

interest,

but

provide

a frame of reference for

considering

their

own. No

anthropologist

has

provided

a more

positive picture

of the

Kachin value

system,

rituals and behaviour both in

peace

and battle.

This is a

uniquely

American

story

and one not

likely

to interest the Burmese or British

reader.

Yet,

it

provides

an

important

dimension to the war stories in that it examines the

conflict from the

perspective

of the

minorities,

who the author believes will

lose,

regard

less of the outcome. It

suggests

some of the

problems

that were bound to arise after the

war when the Kachins were left to fend for themselves

against

the

Burmans,

and it

expresses

the fear that

they might

not be able to retain their

political

freedom and

way

of life once the

fighting

ends. As

part

of the literature

on

Burma,

it offers one of the best

descriptions

of life

amongst

the Kachins one is

likely

to find in

popular

literature.

If Chamales sees the minorities as noble

savages, Harry

I. Marshall sees them

quite

differently.

Given his

background

as an American

Baptist missionary

and a trained

anthropologist

whose

scholarly study

of the Karens is a

classic,

his novel Naw Su is a

mixture of both traditions.

Looking

at the Karens as a backward hill

people,

he makes

the case for

Christianity

as a

civilizing

and

enlightening

vehicle. The Karens in this

novel,

which was set in the

period just following

the third

Anglo-Burmese

War

(1885?

86),

are hill

dwellers, primitive, dirty,

and filled with

superstitions

and fears of the

Burmans who have dominated them. Naw Su is the

story

of a Karen

girl

who

rejects

native

superstitions

and searches for

something

different and better. She finds it when

she leaves the hills and enters a

missionary

school where she learns to read and to live in

a different

way. Cleanliness, godliness,

and self reliance

gradually

transform her. In time

she returns to the hills to

bring

new ideas and

techniques

to her

people. Although

written

very simply

and almost as a

parable,

it nevertheless contains excellent cultural detail

which

gives

an accurate

picture

of Karen life in the hills of Burma

where,

even

today,

This content downloaded from 14.139.69.54 on Tue, 29 Apr 2014 02:04:49 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Burma

through

Western Novels

137

there are

many

who have had little or no contact with the outside world and still live

much as

they

did before the arrival of the Westerner. This

author, too,

sees a kind of

nobility amongst

the

Karens,

especially

when

they

allow themselves to surrender to the

teachings

of the missionaries and

gain

new

strength

from their

foreign

doctrines and

techniques.

If,

in this

case,

the clash of cultures is

uneven,

it is intended to be. For the

reader who will not be

put

off

by

the

special pleading

of the

author,

the novel will reward

him with the best

portrait

of the hill Karens he is

likely

to find in fiction.

John

Slimming,

a British writer who earned his

reputation

as a novelist of books on

Malaya, joins

his American

counterparts,

Chamales and

Marshall,

in

presenting

a

sympathetic portrait

of the

minorities,

again

the

Kachins,

in his novel The Pass. This is

one of the few books on Burma that is set in the

post-independence period

and its action

takes

place against

the

background

of the Cold War.

Again,

the conditions of the

people

and the action of the

story

is narrated

by

a Western

journalist

who comes to this area in

search of a

story

of

escape

from Communist China. Under the

Chinese,

the Kachins are

forced to labour

long

hours under the most difficult conditions and therefore are

willing

to seek

escape

rather than remain. Within this frame of

reference,

the author is able to

compare

the life of the Kachins in China and the

majority

who live under Burmese rule.

He makes modest criticisms of the Burma

government

for its failure to

give refuge

to all

who are

lucky enough

to

escape

from China and for its

general neglect

of the minorities.

Once

again,

Christian missionaries are found

living amongst

the

Kachins; however,

unlike their

counterparts

in Naw

Su,

these are less certain of their mission and their

place

in

independent

Burma.

Living

with this Western

family

is a

young

Kachin

woman,

who

embraced

Christianity

while still

very young

and

living

in

China;

persecuted

for her

attachment to this Western

belief,

she

escaped

across the

pass,

found

religious

freedom

and devoted herself to work in the

missionary hospital

that is run

by

her

protectors.

Although Slimming

is not the

equal

of Chamales in

providing

detailed and

graphic

portraits

of individual Kachins and does not share the latter's reverence for the native

nobility

of the

Kachins, nevertheless,

he does

provide interesting

and accurate

portraits

of this

minority group

as

they

existed in the 1950s. His discussions of the Kachins bear

out some of the fears for their future that Chamales had

expressed

in his earlier novel.

Finally,

there are two historical novels which deserve attention. Maurice

Collis,

She

was a

Queen,

is set

against

the

reigns

of the last two monarchs of the

Pagan dynasty,

Usana and

Narathihapate,

while F.

Tennyson

Jesse,

The

Lacquer Lady,

takes

place

during

the

reign

of the last

king

of the

Konbaung dynasty,

Thibaw. In

style,

content,

and

source,

they

are as different as two novels can be. Collis used the

English

translation of

the Hmannan Yazawun or the Glass Palace

Chronicles,

which were

prepared

in 1829

by

Burman scholars under the direction of the

king,

as his chief source.

Jesse,

on the other

hand,

relied on documents and interviews with Burmese and

Europeans

who either had

first-hand

knowledge

of events or assured her that

they

had received their information

from

participants

or observers. Collis tells the

story

of the rise of a

peasant girl,

who was

destined for

greatness,

to the station of chief

queen,

and the life she

spent

at the

court;

Jesse follows the

intrigues

of a

jealous

and

demanding

chief

queen, Supayalat,

as she

maneuvers and dominates her

husband, Thibaw,

and

helps bring

down the

empire.

Unlike

Collis,

Jesse

provides

a

lady-in-waiting, Fanny,

the

Lacquer Lady,

who,

if the

story

is to be

believed,

caused the third

Anglo-Burmese

War

through

her

jealous

actions. In a historical

sense,

the two stories are

similar;

both

dynasties

fell to

foreign

invaders,

the Chinese in the case of the

Pagan dynasty

and the British in the time of the

Konbaung dynasty,

while in fact both

dynasties

are in the

process

of internal

collapse.

This content downloaded from 14.139.69.54 on Tue, 29 Apr 2014 02:04:49 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

138

Josef

Silver stein

Ma

Saw,

the heroine of She Was A

Queen,

is shown from two

perspectives:

as a

girl

growing up

in an

upper

Burma

village

and as a

queen

at the court. In

each,

the author

provides insightful

discussion of the

interrelationships

between the

people,

their

lifestyle

and,

more

important,

their belief

system.

Here,

the reader is introduced to the

magical

world of

omens,

signs, spirits,

and other

supernatural

forces that

govern

the beliefs of

commoners and

royalty

alike. Collis also

gives

an

excellent

picture

of court

instability

through

his

descriptions

of

intrigue

and

plotting,

reward and

revenge,

which were the

ongoing

activities of the courtiers as

they sought power

and

authority

in a

system

that did

not have an

orderly process

of succession

or a stable civil service. In this brief

volume,

the reader

finally

will feel that he has entered the world of the Burman

people

and is

seeing

them from within.

Granting

the fact that the author is

an outsider who

depended

upon

translations from his

sources, nevertheless,

he has tried to remain faithful to the

chronicles

and,

in

Burma,

his work

generally

is

recognized

as reliable.

The

Lacquer Lady

will seem more familiar to the Western reader who knows

nothing

of Burma or the area. Jesse fills her

pages

with detailed

descriptions

of the court

and

palace,

the

city

of

Mandalay

and its

European

and Burmese inhabitants and the

influences

upon

both

by Rangoon,

Calcutta, London,

and Paris. Once

again,

the

bridge

is an

Anglo-Burman, Fanny;

she was the

daughter

of a Burman mother and an Italian

father,

who was educated in

England,

and became a

lady-in-waiting

at the Burman

court. Given her

knowledge

of both

worlds,

she moves

easily

between them as she

slips

in and out of the

palace. Through

her,

the reader meets a host of historical as well as

fictional characters who mesh and clash as the

story

unfolds. For the reader who is

interested in

learning

about life at court or

comparing

the court of the nineteenth

century

with that of the

thirteenth,

the

period

of She Was A

Queen,

he will find the

descriptions

and

dialogue

to be rich and colourful in their detail. He also will find excellent

descrip

tions of architecture of the old

palace,

which still stood at the time the novel was

written,

the

daily

life of the

queen

and her

ladies-in-waiting,

the

relationship

between the

king

and his

queens

as well as the

intrigue

both in and outside the

palace.

Many

have

quarreled

with the author's

interpretation

of life at the court and the

sprawling city

outside. Burmese have been offended

by

her

presentation

of their last

king

as

easily manipulated

and not in

complete

control of his mental

faculties;

his

cruelty

and lack of

judgement

were

widely publicized during

his lifetime in the Western

press.

Supayalat,

the

queen, too,

is

presented

in the most

negative

fashion

possible.

She, too,

is shown as

cruel, petty, revengeful,

and

ignorant

of the outside world as she seeks

power

and influence. Whether later

day

historians will reverse these

judgements

remains to be

seen. Jesse

presents

the court and its inhabitants as Western historians have described

them and makes no allowances for the biases that

they may

have harboured.

It is

Fanny

who

provides

not

only

the link between the Burman court and the outside

but,

in

addition, represents

the different mentalities found in the two

places.

When

Fanny

is in the court she behaves as do the other

women;

when

outside,

she is the

modern and for her

times, liberated,

woman who is in contact with missionaries and

businessmen, government

officials and charlatans.

Through

her,

the reader

gets

the

feeling

of

being

a

part

of this Asian

capital

where traditional Burma is in

open

conflict

with the

agents

and ideas of the West.

The narrative is filled with real historical

figures

and Jesse

brings

them to life. Arthur

Phayre,

Dr.

Marks,

the Kinwun

Mingyi

and

many

others

leap

from the

pages

of

history

and

are

presented,

not as idealized

types,

but as

living

characters with known

strengths

and weaknesses.

Fanny, Captain Bagshaw

her

husband,

and Bonvoisin her

lover, may

This content downloaded from 14.139.69.54 on Tue, 29 Apr 2014 02:04:49 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Burma

through

Western Novels 139

or

may

not be

real,

but

they

are

believable and

they help

the reader to understand both

the

Anglo-Burman

and the

Europeans

who

populated

Burma

during

the last

days

of

Thibaw's

reign.

Historians

may

quarrel

with Jesse over her

subplot,

the

jilting

of

Fanny by

her French

lover and the heroine's

revenge:

revelations to the British of a

French

plot

to dis

place

their

European

rival as the

ally

of Burma. Burmese

historians, especially,

Dr.

Maung Maung, dispute

the notion of a French

plot

as the basis of British

aggression

against

the Burmans in 1885.

Certainly

it was a

factor,

and Jesse tries to make it more

important

than it

probably

was.

Nevertheless,

it is a

plausible story and,

given

the British

fears of French advancement westward from

Indochina,

it borders

so

closely

to real

events that the reader will find the fictionalized account of

big power rivalry

to be a

useful

way

of

examining

both the behaviour of the court and its

European

adversaries.

The era of Westerners

writing

about Burma is over. The restrictions on

travel and

residence in Burma makes it

impossible

for an

outsider to learn and observe the nation

and its

people

in their

daily

lives. More

important,

the

era of

expatriates living

at a

higher

standard than

they

would at home is finished. The novels of Burma in the future will be

written

by

Burmese writers. A

large body

of Burmese novels

exist,

but have not been

translated.

Therefore,

the writers and their stories are all but unknown to the outside

world; thus,

the modern

epics

of Burma's

struggle

for

independence,

for

unity amongst

its

people,

and for modernization without loss of national

character,

exist or are in the

process

of

being

written.

However,

until either Burmese or

Western translators make

these novels available in

English

and Western

publishing

houses

bring

out these

works,

they

are

likely

to remain unknown to the world

beyond

Burma. That in the end would

be a

tragedy

because it would be a

part

of the

perpetuation

of Burma's isolation and a

loss of contact between

peoples

at a

very

time when communications and media are

bringing

the

peoples

of the world

together.

The novels of Burma do

provide

an

important prism through

which the strands of

light

propel images

and ideas of Burma to the reader that

help

him to understand

aspects

of

Burmese life and culture.

They

are

useful to scholar and

layman

alike and it is

hoped

that

the

growing body

of those written

by

Burmese novelists will soon refract their

light

on

independent

Burma and

help

us to know it better.

This content downloaded from 14.139.69.54 on Tue, 29 Apr 2014 02:04:49 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

140

Josef

Silverstein

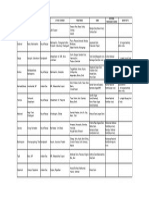

A BRIEF ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY

1.

Bates, H.E., The Jacaranda Tree

(London: Penguin

Books,

1977),

250

pp. (available only

in

England).

The

story

of

escape

from the

Japanese

invasion of Burma

by

a small

party

of

Europeans

and Burmese.

2.

_

, The

Purple

Plain

(London: Penguin

Books,

1977),

233

pp. (available only

in

England).

The

story

of war heroism as a small

party

of downed fliers make their

way

to

safety.

This novel was made into a film.

3.

Collis, Maurice,

She Was A

Queen (London:

Faber and Faber

Limited,

1952),

248

pp.

(out

of

print).

A historical novel of the last

years

of the

Pagan dynasty.

Follows the rise of

a

peasant girl

to chief

queen

and life at court.

4. _, Sanda Mala

(New

York: Carrick and

Evans, Inc.,

1940),

328

pp.

Also

published

in

England by

Faber and Faber Limited

(out

of

print).

A love

story

between a

European

painter

and a Burmese

girl,

and life in lower Burma in the 1920s.

5.

Chamales,

Tom

T.,

Never So Few

(New

York: Charles Scribner's

Sons,

1957) (out

of

print).

An

outstanding

war

story

about American

special

forces

fighting alongside

Kachins

in Northern Burma. This novel was made into a film.

6.

Cruttwell, Patrick,

A Kind

of Fighting (New

York: Macmillan

Company, 1960),

272

pp.

(out

of

print).

A

thinly disguised story

of Burma's nationalist

leader, Aung

San.

7.

Marshall,

Harry

I.,

Naw Su

(Portland,

Maine: Falmouth

Publishing

House, 1947),

351

pp. (out

of

print).

A

simple story

of a

young

Karen

girl

who leaves her

village

and lives

with American

Baptists

as she

adopts Christianity

and later

imparts

it to her

people

8.

Jesse,

F.

Tennyson,

The

Lacquer Lady (New

York: Macmillan

Company, 1930),

441

pp.

(available

in new

paperback edition).

A historical novel of courtlife and

intrigue during

the

reign

of Burma's last

monarch,

Thibaw.

9.

Leslie, Cecilie,

The Golden Stairs

(Garden City: Doublday

and

Company,

Inc.,

1968),

286

pp. (out

of

print).

A

haunting

and sensitive

story

of

escape

from the

Japanese

invaders

by

a

group

of

Europeans

and Asians who

eventually

reach India.

10.

Orwell,

George,

Burmese

Days (London: Penguin

Books,

1969),

272

pp.

The best known

novel of Burma. The

story

of a small

group

of

Europeans living

in

upper

Burma who are

corrupted by

the colonial

system they

serve.

11.

Mannin, Ethel,

The

Living

Lotus

(New

York: G. P. Putnam's

Sons,

1956),

255

pp. (out

of

print).

The

story

of an

Anglo-Burman girl

who is raised

by

a Burman

family during

World

War

II;

later she is lured to

England by

her father who tries to make her a Christian and

English

and fails on both counts.

12.

Shute, Nevil,

The

Chequer

Board

(New

York: William Morrow and

Company, 1947) (out

of

print). Only

a

portion

of the novel deals with

Burma;

it

provides

the

background

of

a

subplot

about an

English pilot

who is shot down

during

the war and finds love and

happiness

amongst

the Burmese.

13.

Slimming,

John,

The Pass

(New

York:

Harper

Bros.,

1962),

256

pp.

A novel set in

post

independent

Burma,

which takes

place

in the border

region

of the Kachin State where

Kachins,

against

difficult

odds,

seek to

escape

from China.

14.

Takeyama,

Michio, Harp of

Burma

(Rutland,

Vermont;

Charles E. Tuttle

Co.,

1968),

132

pp. (translated by

Howard

Hibbett).

The

unique story

of Burma's

impact upon

a

defeated

company

of

Japanese

soldiers who await

repatriation

home.

This content downloaded from 14.139.69.54 on Tue, 29 Apr 2014 02:04:49 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- 1 The Novel in Its Context: ObjectivesDocument10 pages1 The Novel in Its Context: ObjectivesmaayeraPas encore d'évaluation

- Un T 6 Critical Perspectives: ObjectivesDocument8 pagesUn T 6 Critical Perspectives: ObjectivesmaayeraPas encore d'évaluation

- 2 Main Themes in Pride A N D: ObjectivesDocument7 pages2 Main Themes in Pride A N D: ObjectivesmaayeraPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit 3 Main Themes: PrideDocument6 pagesUnit 3 Main Themes: PridemaayeraPas encore d'évaluation

- Jane AustenDocument6 pagesJane AustenmaayeraPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit Characters in The Novel: 4.0 ObjectivesDocument9 pagesUnit Characters in The Novel: 4.0 ObjectivesmaayeraPas encore d'évaluation

- Governance in IndiaDocument33 pagesGovernance in IndiaRohan KoliPas encore d'évaluation

- Elizabethan Revenge Tragedy: An OutlineDocument4 pagesElizabethan Revenge Tragedy: An Outlinetvphile1314Pas encore d'évaluation