Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Platonist Guide to Love

Transféré par

Daniel Perrone100%(1)100% ont trouvé ce document utile (1 vote)

70 vues7 pagesThe document discusses evidence for the existence of a "Platonist Ars Amatoria", or art of love, within the philosophical tradition of Platonism. It finds references to an "art of love" in Plato's Phaedrus and in the writings of later Platonists like Hermeias and Alcinous. Alcinous in particular described the art of love as having three steps: (1) discerning a worthy object of love, (2) gaining possession of them through acquaintance, and (3) using them by encouraging virtue training so that true friendship may result. The document argues this shows Platonists attempted to systematically outline the proper steps of an erotic relationship, influenced by discussions

Description originale:

Titre original

Dillon -A Platonist Ars Amatoria

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentThe document discusses evidence for the existence of a "Platonist Ars Amatoria", or art of love, within the philosophical tradition of Platonism. It finds references to an "art of love" in Plato's Phaedrus and in the writings of later Platonists like Hermeias and Alcinous. Alcinous in particular described the art of love as having three steps: (1) discerning a worthy object of love, (2) gaining possession of them through acquaintance, and (3) using them by encouraging virtue training so that true friendship may result. The document argues this shows Platonists attempted to systematically outline the proper steps of an erotic relationship, influenced by discussions

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

100%(1)100% ont trouvé ce document utile (1 vote)

70 vues7 pagesPlatonist Guide to Love

Transféré par

Daniel PerroneThe document discusses evidence for the existence of a "Platonist Ars Amatoria", or art of love, within the philosophical tradition of Platonism. It finds references to an "art of love" in Plato's Phaedrus and in the writings of later Platonists like Hermeias and Alcinous. Alcinous in particular described the art of love as having three steps: (1) discerning a worthy object of love, (2) gaining possession of them through acquaintance, and (3) using them by encouraging virtue training so that true friendship may result. The document argues this shows Platonists attempted to systematically outline the proper steps of an erotic relationship, influenced by discussions

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 7

A Platonist Ars Amatoria

Author(s): John Dillon

Reviewed work(s):

Source: The Classical Quarterly, New Series, Vol. 44, No. 2 (1994), pp. 387-392

Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of The Classical Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/639642 .

Accessed: 19/12/2012 15:20

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

.

Cambridge University Press and The Classical Association are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve

and extend access to The Classical Quarterly.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded on Wed, 19 Dec 2012 15:20:24 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Classical

Quarterly

44

(ii)

387-392

(1994)

Printed in Great Britain 387

A PLATONIST ARS AMA TORIA'

The

concept

of an 'art of love' has been

popularised

for all time

by

the

naughty

masterpiece

of Ovid. A

good

deal of critical attention has been devoted to this work

in recent

times,2 including

some to his

possible sources,3

but under this latter rubric

attention has

chiefly

been directed rather to his

parody

of more serious

types

of

handbook,

such as an ars

medica,

an ars

grammatica,

or an ars

rhetorica,

than to the

possibility

of his

having predecessors

in the actual 'art' of love.

However,

there is some evidence that even in the area of erotic instruction Ovid had

predecessors.

What I

propose

to do in this

essay

is to

explore

the evidence for

something

like an 'art of

love'

in the

philosophical tradition,

and in

particular

in that

of Platonism. The evidence for such a

development

is

largely very late,

but it

may

be

none the less useful on that

account,

as it

gives

the

strong impression

of

reflecting

a

long-standing

tradition.

Let us start from a

programmatic passage

near the

beginning

of the Ars

Amatoria,

at I 35-40:

Principio, quod

amare

velis, reperire

labora

qui

nova nunc

primum

miles in arma venis.

Proximus huic labor est

placitam

exorare

puellam;

tertius, ut

longo tempore

duret amor.

Hic

modus;

haec nostro

signabitur

area

curru;

haec erit admissa meta

premenda

rota.

From this

passage

we

may,

in

prosaic terms,

extract three

principles

of

procedure:

(1)

Select a

proper object

of love

(quod

amare

velis, reperire labora).

(2)

Commend

yourself

to

your

chosen beloved

(placitam

exorare

puellam).

(3)

Strive to ensure that the love shall be

long-lasting (tertius (labor),

ut

longo

tempore

duret

amor).

Ovid

proceeds

to elaborate on each of these

injunctions

in

ways

that we need not

go

into in the

present

context. Let us turn instead to the Platonist

tradition,

to see if we

can come

up

with

anything comparable.

We find a mention of an 'art of love'

(Epwr0TLK r

7X~Vr)

-

the Greek

original

of ars

amatoria - in

Plato's Phaedrus,

at

257a,

in the course of Socrates' ironic final

prayer

at the close of his

'palinode',

where he

prays

to Eros not to

deprive

him of 'that

EpwCO-K7) rTXV-r

which

you

bestowed

upon me',

but here the

phrase

does not refer to

anything very

technical -

simply

the 'feel' for love that Socrates

prides

himself on

having.

For the scholastic minds of later

Platonists, however,

such a reference would

naturally

be

taken,

in the

light

of

subsequent developments

in the Hellenistic

era,

to

refer to

something systematic.

1

This

essay

was first delivered to a

colloquium

at the

University

of

Washington

in Seattle.

I am most

grateful

to

colleagues there, especially Stephen

Hinds and

Mary

Whitlock

Blundell,

for much useful discussion. A

subsequent airing

at the

University

of California at

Berkeley

produced

valuable

comments,

in

particular

from Alexander Nehamas and John Ferrari.

2

See

e.g.

A. S.

Hollis, Ovid,

Ars

Amatoria,

Book

I,

ed. with introduction and

commentary

(Oxford, 1974) and,

more

recently, Molly Myerowitz,

Ovid's Games

of

Love

(Wayne

State

U.P.,

Detroit, 1985).

3

There is a useful article

by

Knut

Kleve,

'NASO MAGISTER

ERAT

-

sed

quis

Nasonis

magister?', Symbolae

Osloenses 58

(1983), 89-109,

where a

good many analogies

between Ovid

and

previous

sources are

discussed,

but he addresses himself

only minimally

to the

particular

subject

of this

paper.

The older work of R.

Biirger,

De Ovidi carminum amatoriorum inventione

et arte

(Wolfenbiittel, 1901),

is of no relevance to the

present enquiry

either.

This content downloaded on Wed, 19 Dec 2012 15:20:24 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

388 JOHN DILLON

The

Neoplatonist Hermeias,

in

commenting

on this

passage (In

Phaedr.

207,

17ff.

Couvreur),

sees here a reference to the

system presented by

Socrates in the Alcibiades:

'What is the nature of this "art of love"? It is what he himself has demonstrated in the

Alcibiades,

where he teaches that one must first seek out the

worthy object

of love

(6 d.idpaauros)

and

discern whom one should love

(for

one should not love

everyone,

but

only

the

large-minded

[/LEyaAdopwv],

who

despises secondary things); then,

after

deciding

to

love,

not even to

speak

to him until the critical moment comes when he is

ready

to listen to

philosophical discourses;

and

then,

when he is

ready

to

listen,

take him in hand and teach him the

principles

of

love,

and so

generate

in him a

reciprocal

love

(dv-rpwso).'

Here there seems to me to be a reference not to

any particular passage

of the

Alcibiades,4

but rather to the theme of the whole

dialogue,

which constituted for later

Platonists a

paradigm

case of how the wise man should conduct a love-affair.

Hermeias,

however

(or

rather

Syrianus,

since Hermeias is

really just transcribing

the

proceedings

of his master

Syrianus' seminar),

was not the first Platonist to

attempt

to formalise the various

steps

to be

gone through

in an erotic

relationship.

We find

a similar effort recorded

already

in the

(probably) second-century

A.D.

handbook of

Platonism

by

Alcinous' known as the Didaskalikos. In ch. 33 of that

work,

which

concerns

friendship (tA~'a),

there is

appended

to the discussion of that

topic

a

discussion of erotic love

(187, 20ff.),

which leads in turn

(187, 37ff.)

to the

propounding

of a sort of ars amatoria. This

linking

of a discussion of

Epws

to that of

tA~'a is both obvious enough and sanctioned by age-old usage. In Plato's Lysis, after

all,

a discussion of

Epwcs

leads in to the more

important attempt

to

analyse tA~'a,

while Aristotle in the Nicomachean Ethics

brings ipws

in at EN VIII 4

(though

without

using

the

word),

under the

heading

of

'friendship

for the sake of

pleasure'.

Later,

in the first

century B.C., Arius Didymus

mentions

'pwcs just

before

tA~ha

in his

review of

Peripatetic

ethics

(ap.

Stob. Anth.

2.142,

24-6

Wachsmuth),

which indicates

that this

conjunction

of

topics

in a handbook is not an innovation of Alcinous'.

Alcinous first lists

(as, indeed,

did

Arius)

three levels of

Epoos,

'good', 'bad',

and

'middling',

the

good having

as its

object

the soul

alone,

the bad the

body alone,

and

the

middling

sort both.

Only

the

good,

he then

says, being

free from

passion,

takes

on the nature of an art

(rExVLKnc

7rT

TarPXEL).

Being

a

7Exv-4,

it has

OEowp-g"pra,

and

these are as follows. There are three of

them,

and

they may

be considered with a

glance

back at the

passage

from Ovid

quoted

at the outset:

(1) getting

to know

(yvcovat)

or

discerning

(rTLKpVEw)v)

the

worthy object

of love

(6" detpaoros);

(2) gaining possession (KTo7iaat)

of him, by making

his

acquaintance;

(3) making

use

(XpgaOat)

of

him, by exhorting

him

to,

and

training

him in

virtue,

so

that he

may

become a

'perfect practitioner'

(daKT7

9

7,AEtoS)

of

it,

and that true

friendship may

result

(as

between

equals

who are also

good),

instead of the

relationship

of lover and beloved

-

in other

words,

that

Jvrpopws

should be

generated

in the

beloved,

as Hermeias discerns

being prescribed

in the

Alcibiades,

and as is

certainly

attested to

by

'Alcibiades'

himself,

in his famous tribute to Socrates in the

Symposium (222b).

4 'Discerning

whom one should love' seems to refer to Socrates'

opening speech

as a

whole,

while 'not

speaking

until the critical moment' refers in

particular

to Socrates' mention at 103a

of the

8atpdvwdv

ir

bvav7r(wla

which has hitherto held him back from

addressing

Alcibiades.

'Taking

in hand and

teaching' really

covers the remainder of the

dialogue.

5

Widely

known as

Albinus,

ever since the

monograph

of

Freudenthal,

Der Platoniker Albinos

und der

falsche

Alkinoos

(Berlin, 1879),

but I am now

persuaded by

the

arguments

of John

Whittaker

(in

a series of

articles,

but see now his

Bud6

edition

[Paris, 1989], Intro, pp. vii-xiii)

that the identification rests on

very shaky palaeographic

foundations.

This content downloaded on Wed, 19 Dec 2012 15:20:24 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A PLATONIST ARS AMA TORIA 389

We

may

note here the

postulation

of a triad

of

yvcaris,

KT"77oL,

and

Xprjas

(admittedly

in verbal

form),

such as is

obviously

relevant to the

acquisition

of

any

art

or craft. It

may be, though

I do not

regard

it as

likely,

that Alcinous is

being original

in

applying

this formulation to the art of love.

Apuleius,

in the

parallel

section of his

De

Platone

(II 13),

it must be

said,

shows no

sign

of such a

development.

For an extended

exposition

of the Platonist ars

amatoria,

we must turn to the

Neoplatonist exegesis

of the First

Alcibiades,

and in

particular

to that of Proclus

(who

was,

of

course,

like

Hermeias,

a

pupil

of

Syrianus).

Proclus chooses the lemma

104e7-105a

1

for an

exposition

of the Platonist doctrine of the

d.eEpaa-og,

or

'worthy

object

of love'. There Socrates

says:

'For if I saw

you, Alcibiades,

content with the

things

I set forth

just

now

(sc. beauty, good family, wealth, 104a-c),

and minded to

pass your

life in

enjoying them,

I should

long ago

have

put away my

love - so at least

I

persuade myself!'

'In these

words', says

Proclus

(133,

18ff. West),

'Socrates

clearly

shows what sort

of nature it is that is

worthy

of love. And even as in the

Republic

he has

given

us an

account of the elements of the character of the

philosopher,

so also here he seems to

me to be

setting

out certain elements in the character of the

worthy object

of love.

'These elements are

two-fold,

the one set

visible,

the other

invisible,

the one

manifesting

themselves in relation to the

body,

the other

being

movements observed

internally,

in the

soul;

the one set the

gift

of fate and

nature,

such as

beauty

and

stature,

the other the seeds of divine

providence

instilled in souls with a view to their

salvation,

as for instance the

quality

of

(military) leadership,

the

quality

of

(political)

command,

and the kind of life that is elevated to the

heights.'

Proclus

goes

on to note that it is

precisely

this

quality

of not

being

satisfied with

the external

goods

of life that attracts Socrates in Alcibiades.

Why

is

this,

he asks.

'Because,'

he

replies (135, 4ff.),

'this is characteristic of a soul which disdains what

is

vulgar,

is convinced of its

worthlessness,

and

yearns

to

behold,

I

presume, only

what is

great

and of

value,

not

realising

what has come over it'

(Phaedr. 250a),

but

in accordance with its innate notions

picturing

to itself some other

genuine greatness

and

sublimity.

We

may

note here how the Phaedrus is

brought

in to buttress the

exegesis

of the

Alcibiades,

even as the Alcibiades is

brought

in

by

Hermeias to elucidate the Phaedrus.

The reference to Phaedr. 250a7 should turn our minds to that section of the

Phaedrus,

particularly 253c-256e,

where

precisely,

one would

think,

one finds directions for

capturing

one's

beloved,

and

generating

in him a counter-love. As we

recall,

the

philosophic lover, having quelled

his

unruly horse, approaches

the

beloved,

rather as

Socrates is seen

doing

to Alcibiades in the

Alcibiades,

and

finally

the

beloved,

overcoming

all the

negative propaganda

about not

gratifying

lovers

put

about

by

his

school-mates

(255a),

welcomes his lover and finds

pleasure

and edification in his

company (255b).

Then, through repeated

contact in the

gymnasium

and

elsewhere,

the beloved comes

to see in the lover a sort of reflection of the love that is

being unremittingly

beamed

at

him,

and comes to feel a sort of love

himself,

at first for he knows not

what,

but

then for the lover. This is the much-vaunted

adv-pw6 (255el).

We do thus have in the Phaedrus, albeit in rather

high-flown

and

poetical terms, an

account of how the initial

approach

is to be made, and how a counter-love

may

be

generated

in the beloved, but from the scholastic

point

of view the Phaedrus account

might

seem to fall short of

utility

in various

ways,

in which the Alcibiades is more

satisfactory.

We are not

really

shown in the Phaedrus what sort of discourse we

This content downloaded on Wed, 19 Dec 2012 15:20:24 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

390 JOHN DILLON

should

indulge

in to

impress

our

beloved,

whereas this is

precisely

illustrated in the

Alcibiades,

as is the

satisfactory

reaction of the beloved.

This,

I

think,

is the solution to what

might

seem to us the

paradox

of

passing

over

the two

great

Platonic accounts of

love,

the

Symposium

and the

Phaedrus,

at least for

the

purpose

of

composing

a

practical handbook,

in favour of the more

pedestrian

treatment

presented

in the Alcibiades. There

remains,

I

suppose,

the

Lysis,

which is

also

passed

over for this

purpose.

I can

only suppose

that the

Lysis

was

regarded

as

rather too

aporetic

and

confusing

to form a basis for

positive doctrine, though

we can

certainly

derive some

positive principles

from it. The chief

principle, however,

the

need to demonstrate some

degree

of usefulness if one is to be

lovable, may

have

distressed later Platonist

theorists,

even as it has in recent times offended such a

great

Platonist as

Gregory Vlastos,6

so it

may

have been

disregarded

for that

reason,

as well

as because of its

aporetic

nature. Even the

Alcibiades,

after

all,

had to be

processed

through

the

meat-grinder

of later

scholasticism,

but at least the material was there in

reasonably adaptable

form.7

However,

if the later Platonist

theory

of Love takes its ultimate

inspiration

from

Plato,

it must also owe

something

to Stoic treatments of the

subject,

which will

themselves have been to a

large

extent scholastic formalisations of

positions

taken

up

by Plato,

and indeed

by Aristotle.8

We know that both Zeno and Cleanthes

composed

works entitled The Art

of

Love

(Epw-nCK'T

rVX7v,

DL

7.34; 174),

but we have

unfortunately

no idea of what

they

said

in them.9

Chrysippus, also, composed

both a treatise On Love

(HEp

EpwroSo,

DL

7.129)

and another On

Friendship (in

at least two

books,

Plut. Stoic.

Rep. 13, 1039b),

and we are

slightly

better informed about the contents of these. He also touched on

the

subject

of love in his treatise On

Ways of Life (HEpt

BtLuv,

DL 7.129

=

SVF III

716).

He

says there,

and in the

1HEpt

pwros-,

that the

Sage

will fall in love with

youths

who exhibit in their outward form a natural

tendency

to

virtue,

which is

very

much

what Socrates is

doing

in

respect

of Alcibiades. The

purpose

of noble love is said to

be

friendship,

or 'the creation of

friendship'

(tAtha

or

ktAoTrodta)10

not sexual

intercourse

(avvovoata)

and it is defined" as 'the science of

hunting

out

naturally

6

Cf. 'The Individual as

Object

of Love in

Plato',

in Platonic Studies

(Princeton U.P., 1973)

3-42.

7

We do not find

any

clues as to the views of Plato's immediate

successors, Speusippus

and

Xenocrates,

on the correct

indulgence in,

or use

of, love,

but a straw in the

wind,

I

think,

is

provided by

a rather obscure dictum of

Polemon,

last head of the Old

Academy, reported by

Plutarch

(in

his

essay

To an Uneducated Ruler

780d),

to the effect that 'Love is the service of

the

gods

for the care and

preservation

of the

young' (Oedv

brpealta

dEa

viov

EirLx?AeaV

Kat

aowrr-plav).

This at first

sight

rather

baffling

remark

might

seem to

gain

some

significance

if it

is

regarded

as a summation

by

Polemon of the 'doctrine' of the Alcibiades. Socrates' kind of

loving

can be seen as a service of the

gods

in the form of

conferring

benefits on the

youth.

If

so,

we have here the bare bones of the later

Stoic/Platonist

art of

love,

and our

appreciation

of

Polemon's contribution to Hellenistic

philosophy may

move

up

another notch.

8 There were

also,

it must be

said, Epicurean

treatments of the theme

(e.g.

a treatise

by

Epicurus

himself On

Love,

DL

10.118),

but Platonists are

hardly likely

to have borrowed much

from that source.

9

Of Zeno's other

followers,

Ariston is credited with Discourses on Love

(pw7-rtKaL aa-rptLa, DL

7.163),

and

Sphaerus

with

Dialogues

on Love

(8tdAoyot

pw-tKO',

DL

7.178),

but we are

no better informed about their contents.

10

The

point

of this latter

term,

if

pressed, might

be discerned as

being

the stimulation of

reciprocal

affection

(dv-erpwso)

in the

beloved,

which would constitute a further close connection

with later Platonist

theory

-

and,

of

course,

Socratic

practice.

11 ap.

Stob. Ecl.

2.65,

15ff. Wachs.

=

SVF

3.717;

and cf.

Cicero,

TD 4.72.

This content downloaded on Wed, 19 Dec 2012 15:20:24 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A PLATONIST ARS AMATORIA 391

gifted youths,

with a view to

exhorting

them to live in accordance with

virtue'.l*

All

this sounds as if a

process

of formalisation of the contents of the First Alcibiades has

been

taking place.

This is not an awful lot to

go on,

but it does

indicate,

I

think,

that there was an

appreciable body

of Stoic

theorizing

on the

subject

of

Love,

and on how and

why

it

is to be

indulged

in

by

the

Sage,

and that it followed

very

much the lines adumbrated

by Plato,

or whoever

may

be the author of the Alcibiades

(at

all

events, surely,

a

member either of the Socratic circle or of the Old

Academy).

As one would

expect

of

the

Stoics, things

are

very

much more formalized than

they

would be in a Platonic

dialogue.

I

suspect

that it is

here,

rather than

among

later

Platonists,

that one finds

the first

emergence

of

anything

like a formal

philosophic

ars

amatoria,

but on the

basis of the available evidence it would be rash to assert this.

There

seems, however,

to be a reference to treatises of this sort in the

Anonymous

Theaetetus

Commentary, dating probably

from the mid-second

century A.D.,13

where

the author

remarks,

a

propos

Theaet.

143d,

that 'in treatises on Love

(Ev To0g

EPCowTKot)

it is declared that it is the task of the

good

man

(6

a0rrovxaios)

to

identify

(yvc?vat)

the

proper object

of love

(6

detpa-ros

)'.

This has been

thought by

Diels and

Schubart,

the editors of the

Anon.,

and

by

John Whittaker

(in

his Bude edition of

Alcinous'

Didaskalikos,

n.

548),

to be a reference to

dialogues

of Plato such as the

Phaedrus or the

Symposium (though

indeed the Alcibiades would be more

apposite,

one would

think),

but it seems to me more

likely

that it is a reference to some treatise

such as that of

Chrysippus,

where the

detEpaariog

is

precisely

defined as one who is

worthy

of

a7rova&iog

ipws (SVF 3.717).

We

may

recall the first

GEOepJ7Lpa

of the art

of love set out in Did.

33,

yvc6vat

-Tv

d&tEpaarzov,

where the

terminology

matches

closely

that in the Anon. Theaetetus

Commentary, suggesting

a common source.

What, then, may

we derive from all this? One

thing

in

particular

that modern

students of Plato

may

find

interesting,

if not

paradoxical,

as I have said

already,

is

that on the

subject

of the art of love Platonists turned for

inspiration primarily,

not

to the

Symposium

or the

Phaedrus,

nor even to the

Lysis,

but to the First

Alcibiades.14

But after

all,

that is not so

strange.

We must bear in

mind,

in addition to the

considerations that I adduced

above,

that the First Alcibiades held a

very

much

higher

rank in the ancient Platonist tradition than it does with us. It

was,

of

course, accepted

as a

genuine

work of

Plato,

and as such was

placed

in later times

(certainly by

the

second

century A.D.,

to

judge

from Albinus' Introduction to

Plato)

as the first

dialogue

to be read in a course of

Platonism,

dealing,

as it was deemed to

do,

with the

subject

of

self-knowledge,

a

prerequisite

to

any deeper philosophical insights.

The second

thing

to be

noted,

I

think,

is a certain

development

on the rather self-

centred and

exploitative approach

to love exhibited in the

Symposium

and the

Phaedrus criticized

by Gregory

Vlastos in the article mentioned earlier

(above,

n.

6).

There,

the ultimate

purpose

of

loving

an individual could be construed as

being

the

attainment on the

part

of the

philosopher

lover of a vision of the essence of

Beauty,

12

Reading

rrl 7r(

>

?)>v

with

Meineke,

for the 'w'

r'

v of the MSS.

13

Harold

Tarrant,

Scepticism

or Platonism? The

Philosophy of

the Fourth

Academy

(Cambridge, 1985),

wishes to attribute this work to the Platonist

Eudorus,

and thus to the late

first

century B.C.,

which is an attractive

suggestion,

but

unfortunately

not

quite provable.

14

Not so modern

authorities,

however. A

perusal

of two substantial French works on the

subject,

Ludovic

Dugas, L'amitie

antique (Paris 1894; repr.

New

York, 1978),

and Jean-Claude

Fraisse, Philia,

la notion d'amitie dans la

philosophie antique (Paris,

2nd

ed., 1984)

reveals no

substantial attention

paid

to the

Alcibiades,

and the same is true for the recent

English

work of

A. W.

Price,

Love and

Friendship

in Plato and Aristotle

(Oxford, 1989).

This content downloaded on Wed, 19 Dec 2012 15:20:24 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

392 JOHN DILLON

without there

being

much in the whole

process,

to all

appearances,

for the beloved.

I

happen

to think that this is rather unfair to Plato

(there is, surely,

at the

very least,

for the

beloved,

the

opportunity

to learn how to become a

philosophic

lover in his

turn,

and so to

exploit

someone

else),

but I

agree

that this is an

impression

that can

be derived from the texts.

In the later handbook

tradition,

both Stoic and

Platonist,

on the other

hand,

it

would seem that much more

emphasis

was

put (building,

no

doubt,

on the

Alcibiades)

on the benefits to be derived

by

the

beloved,

and the

justification

for love is the

instilling

of noble

thoughts

in the

beloved,

and the institution of a

lasting friendship.

This

is, admittedly, envisaged

in the Phaedrus account at

least,

but it is undeniable

that the

emphasis

in the two central Platonic

dialogues

is on the benefits

accruing

to

the lover. It is

only

Aristotle who defines

tALta,

which for him includes

love,

as

'wishing

and

acting

for the

good,

or the

apparent good,

of one's

t'Aog,

or

wishing

for

the existence and life of one's

t'Aog

for that man's sake'

(EN 1166a2-5, cf.

also Rhet.

1380b35-1381

lal),

a

concept which, together

with the old

Pythagorean tag defining

a

0t'Ao

as

'another

self',

does

seem to have worked its

way

into the handbook

tradition.

In view of all

this,

it is

easily comprehensible that,

in the

light

of the

theorizing

of

Aristotle and of the Stoics about

perfect friendship (the

latter

perhaps, indeed,

itself

influenced

by

a

reading

of the

Alcibiades),

later Platonists should have turned from

the

primarily

self-directed accounts of the

Symposium

and the Phaedrus to the more

altruistic

portrayal

of Socrates'

amatory procedure

in the Alcibiades.15

Trinity College,

Dublin JOHN DILLON

15

The

possibility

has been

put

to me

by Mary

Whitlock Blundell of some influence

filtering

through

from other treatments of the Socrates-Alcibiades

relationship,

such as in

particular

that

of Aeschines of

Sphettus

in his

dialogue Alcibiades,

or

perhaps

in a

dialogue

where

Aspasia

took

on a role

analogous

to that of Diotima in the

Symposium.

I would

regard

this as an

attractive,

but not a

necessary, supposition.

The Platonic Alcibiades

provides,

I

think,

an

adequate

explanation

of the

phenomena. Further,

in Aeschines' Alcibiades

(Fr.

11

Dittmar),

Socrates

seems to attribute

any power

he has to

improve

Alcibiades to 'divine

dispensation'

(OEla

ozpa),

rather than

-rdxvmr,

which would militate

against

the

possibility

that this is a source.

This content downloaded on Wed, 19 Dec 2012 15:20:24 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Democritus On Politics and The Care of The SoulDocument26 pagesDemocritus On Politics and The Care of The SoulJess Lai-tusPas encore d'évaluation

- Plato's Theory of Recollection ReconsideredDocument19 pagesPlato's Theory of Recollection ReconsideredἈρχεάνασσαΦιλόσοφος100% (1)

- Phronesis Volume 28 Issue 1 1983 (Doi 10.2307/4182166) Harold Tarrant - Middle Platonism and The Seventh EpistleDocument30 pagesPhronesis Volume 28 Issue 1 1983 (Doi 10.2307/4182166) Harold Tarrant - Middle Platonism and The Seventh EpistleNițceValiPas encore d'évaluation

- The Importance of Silence in PrayerDocument1 pageThe Importance of Silence in PrayerJonathan McdonaldPas encore d'évaluation

- L. Campbell - On The Place of The Parmenides in The Chronological Order of The Platonic DialoguesDocument9 pagesL. Campbell - On The Place of The Parmenides in The Chronological Order of The Platonic DialoguesRashi BennettPas encore d'évaluation

- 02 Zahavi D. The Experiential Self - Objections and ClarificationsDocument12 pages02 Zahavi D. The Experiential Self - Objections and ClarificationsHanno VarresPas encore d'évaluation

- Orthodox MasculinityDocument24 pagesOrthodox MasculinityJosé Contreras0% (1)

- The Penguinification of Plato Trevor SaundersDocument11 pagesThe Penguinification of Plato Trevor SaundersabunasrPas encore d'évaluation

- Mayer, R. (2003) Persona Problems The Literary Persona in Antiquity Revisited - MD 50, Pp. 55-80Document27 pagesMayer, R. (2003) Persona Problems The Literary Persona in Antiquity Revisited - MD 50, Pp. 55-80n pPas encore d'évaluation

- NC Vocations 2 PDFDocument6 pagesNC Vocations 2 PDFMacariusPas encore d'évaluation

- The Seventh ST Andrew's Patristic SymposiumDocument20 pagesThe Seventh ST Andrew's Patristic SymposiumDoru Costache100% (1)

- Stephen Menn - Aristotle and Plato On God As Nous and As The Good PDFDocument32 pagesStephen Menn - Aristotle and Plato On God As Nous and As The Good PDFcatinicatPas encore d'évaluation

- Bett Richard - Immortality and The Nature of The Soul in The PhaedrusDocument27 pagesBett Richard - Immortality and The Nature of The Soul in The PhaedrusFelipe AguirrePas encore d'évaluation

- Justin Martyrs Theory of Seminal Logos ADocument11 pagesJustin Martyrs Theory of Seminal Logos ARene OliverosPas encore d'évaluation

- Aristotle on Xώρα in Plato's "Timaeus" ("Physics" IV-2, 209 B 6-17)Document19 pagesAristotle on Xώρα in Plato's "Timaeus" ("Physics" IV-2, 209 B 6-17)Zhennya SlootskinPas encore d'évaluation

- Cadden2012 Albertus Magnus On Vacua in The Living Body PDFDocument18 pagesCadden2012 Albertus Magnus On Vacua in The Living Body PDFEsotericist MaiorPas encore d'évaluation

- Alcmena and AmphitryonAncientModernDramaDocument48 pagesAlcmena and AmphitryonAncientModernDramametamilvyPas encore d'évaluation

- Daniel Murphy-Martin Buber's Philosophy of Education-Irish Academic Press (1988)Document122 pagesDaniel Murphy-Martin Buber's Philosophy of Education-Irish Academic Press (1988)Kabir Abud JasoPas encore d'évaluation

- Absolute Divine Simplicity and Hellenic Presuppositions - Jay Dyer - The Soul of The EastDocument18 pagesAbsolute Divine Simplicity and Hellenic Presuppositions - Jay Dyer - The Soul of The EaststefanosPas encore d'évaluation

- Person Vs Individual - YannarasDocument2 pagesPerson Vs Individual - YannarasantoniocaraffaPas encore d'évaluation

- Changing The Topic - Topic Position in Ancient Greek Word OrderDocument34 pagesChanging The Topic - Topic Position in Ancient Greek Word Orderkatzband100% (1)

- Personhood Cover PDFDocument4 pagesPersonhood Cover PDFgrey01450% (1)

- Annas, Julia E. - Hellenistic Philosophy of MindDocument151 pagesAnnas, Julia E. - Hellenistic Philosophy of Mindadrian floresPas encore d'évaluation

- Trinitarian Freedom - ZizoulasDocument15 pagesTrinitarian Freedom - ZizoulasObilor Ugwulali100% (1)

- The Doctrine of The Hypostatic Union AffDocument28 pagesThe Doctrine of The Hypostatic Union AffMeland NenoPas encore d'évaluation

- Aristotle's Great-Souled ManDocument31 pagesAristotle's Great-Souled ManDaniel PerronePas encore d'évaluation

- Plato's Concept of Eros ExploredDocument18 pagesPlato's Concept of Eros Exploredvrian v-iscaroPas encore d'évaluation

- The Lyric, History, and The Avant-Garde: Theorizing Paul CelanDocument19 pagesThe Lyric, History, and The Avant-Garde: Theorizing Paul CelangeoffreywPas encore d'évaluation

- Autopoiesis and Heidegger'sDocument117 pagesAutopoiesis and Heidegger'sHammadi AbidPas encore d'évaluation

- Existentialist PrimerDocument8 pagesExistentialist PrimerStan LundfarbPas encore d'évaluation

- Edelstein. L. The Relation of Ancient Philosophy To MedicineDocument19 pagesEdelstein. L. The Relation of Ancient Philosophy To MedicineLena SkPas encore d'évaluation

- The History of A Greek ProverbDocument32 pagesThe History of A Greek ProverbAmbar CruzPas encore d'évaluation

- Existential TherapyDocument19 pagesExistential TherapyJHAZZEL FAITH DARGANTESPas encore d'évaluation

- Contemplation Form PlotinusDocument15 pagesContemplation Form PlotinusMARIA DE LOS ANGELES GONZALEZPas encore d'évaluation

- C. Tsirpanlis - The Liturgical Theology of Nicolas CabasilasDocument15 pagesC. Tsirpanlis - The Liturgical Theology of Nicolas CabasilasMarco FinettiPas encore d'évaluation

- BRAICOVICH - Freedom and Determinism in Epictetus Discourses PDFDocument23 pagesBRAICOVICH - Freedom and Determinism in Epictetus Discourses PDFFernanda OliveiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Socratic Eros and Platonic Dialectic PDFDocument16 pagesSocratic Eros and Platonic Dialectic PDFAlex MadisPas encore d'évaluation

- FABIANO Fluctuation in Theocritus' StyleDocument21 pagesFABIANO Fluctuation in Theocritus' StylekatzbandPas encore d'évaluation

- The Photian Schism: History and Legend of an Ecclesiastical ConflictDocument518 pagesThe Photian Schism: History and Legend of an Ecclesiastical ConflictKris BoçiPas encore d'évaluation

- Phronema 25, 2010Document4 pagesPhronema 25, 2010Doru CostachePas encore d'évaluation

- 30224233Document4 pages30224233Fabiola GonzálezPas encore d'évaluation

- Johnston. The Book of Saint Basil The Great, Bishop of Caesarea in Cappadocia, On The Holy Spirit, Written To Amphilochius, Bishop of Iconium, Against The Pneumatomachi. 1892.Document256 pagesJohnston. The Book of Saint Basil The Great, Bishop of Caesarea in Cappadocia, On The Holy Spirit, Written To Amphilochius, Bishop of Iconium, Against The Pneumatomachi. 1892.Patrologia Latina, Graeca et Orientalis100% (2)

- Hopkins Poetry and PhilosophyDocument8 pagesHopkins Poetry and Philosophygerard.casey2051Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Uncanny Experience of Mirror Self-RecognitionDocument10 pagesThe Uncanny Experience of Mirror Self-RecognitionmancolPas encore d'évaluation

- Russian SymbolismDocument241 pagesRussian SymbolismLEE KUO-YINGPas encore d'évaluation

- The Philosophy of Spinoza (Volume 1)Document468 pagesThe Philosophy of Spinoza (Volume 1)Alexandre De Pomposo García-CohenPas encore d'évaluation

- Existentialism MounierDocument149 pagesExistentialism MouniermaxxPas encore d'évaluation

- Socratic ScepticismDocument20 pagesSocratic ScepticismRoger WertheimerPas encore d'évaluation

- PhA 132 - Leigh (Ed.) - The Eudemian Ethics On The Voluntary, Friendship, and Luck - The Sixth S. V. Keeling Colloquium in Ancient Philosophy 2012 PDFDocument227 pagesPhA 132 - Leigh (Ed.) - The Eudemian Ethics On The Voluntary, Friendship, and Luck - The Sixth S. V. Keeling Colloquium in Ancient Philosophy 2012 PDFPhilosophvs Antiqvvs100% (1)

- How Is Weakness of The Will PossibleDocument11 pagesHow Is Weakness of The Will PossibleAlberto GonzalezPas encore d'évaluation

- Paul Oskar Kristeller, Thomas A. Brady, Heiko Augustinus Oberman-Itinerarium Italicum_ The Profile of the Italian Renaissance in the Mirror of Its European Transformations (Studies in Medieval and Ref.pdfDocument580 pagesPaul Oskar Kristeller, Thomas A. Brady, Heiko Augustinus Oberman-Itinerarium Italicum_ The Profile of the Italian Renaissance in the Mirror of Its European Transformations (Studies in Medieval and Ref.pdfJefferson de AlbuquerquePas encore d'évaluation

- VERDENIUS, W. J. Parmenides' Conception of Light (1949)Document17 pagesVERDENIUS, W. J. Parmenides' Conception of Light (1949)jeremy_enigmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Puppet Theater in Plato's CaveDocument12 pagesPuppet Theater in Plato's CaveAllison De FrenPas encore d'évaluation

- Richard Gordon - Mater Magna and AttisDocument19 pagesRichard Gordon - Mater Magna and Attison77eir2Pas encore d'évaluation

- Byzantine Hesychasm in The 14th and 15thDocument55 pagesByzantine Hesychasm in The 14th and 15thGeorgel Rata100% (1)

- Tim Riggs - On The Absence of The Henads in The Liber de Causis: Some Consequences For Procline SubjectivityDocument22 pagesTim Riggs - On The Absence of The Henads in The Liber de Causis: Some Consequences For Procline SubjectivityDereck AndrewsPas encore d'évaluation

- Prophecies of Language: The Confusion of Tongues in German RomanticismD'EverandProphecies of Language: The Confusion of Tongues in German RomanticismPas encore d'évaluation

- "Every Valley Shall Be Exalted": The Discourse of Opposites in Twelfth-Century ThoughtD'Everand"Every Valley Shall Be Exalted": The Discourse of Opposites in Twelfth-Century ThoughtÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (1)

- Inheriting the Future: Legacies of Kant, Freud, and FlaubertD'EverandInheriting the Future: Legacies of Kant, Freud, and FlaubertPas encore d'évaluation

- Volition's Face: Personification and the Will in Renaissance LiteratureD'EverandVolition's Face: Personification and the Will in Renaissance LiteraturePas encore d'évaluation

- Griffiths - Kant's Psychological Hedonism PDFDocument11 pagesGriffiths - Kant's Psychological Hedonism PDFDaniel PerronePas encore d'évaluation

- Everitt - Kant's Discussion of The Ontological ArgumentDocument21 pagesEveritt - Kant's Discussion of The Ontological ArgumentDaniel PerronePas encore d'évaluation

- Anselm's Ontological Arguments: Does Existence Add PerfectionDocument23 pagesAnselm's Ontological Arguments: Does Existence Add PerfectionDaniel PerronePas encore d'évaluation

- Griffiths - Kant's Psychological Hedonism PDFDocument11 pagesGriffiths - Kant's Psychological Hedonism PDFDaniel PerronePas encore d'évaluation

- Lazos Ochoa - On The Concept of A Practical Deduction in Kant's Moral PhilosophyDocument14 pagesLazos Ochoa - On The Concept of A Practical Deduction in Kant's Moral PhilosophyDaniel PerronePas encore d'évaluation

- Hintikka - Kant On Existence, Predication, and Ontological ArgumentDocument21 pagesHintikka - Kant On Existence, Predication, and Ontological ArgumentDaniel PerronePas encore d'évaluation

- Hintikka - Kant On Existence, Predication, and Ontological ArgumentDocument21 pagesHintikka - Kant On Existence, Predication, and Ontological ArgumentDaniel PerronePas encore d'évaluation

- Kant and Greek Ethics - 1 (K. Reich)Document18 pagesKant and Greek Ethics - 1 (K. Reich)Daniel PerronePas encore d'évaluation

- Brancacci Antistene Pensiero Politico PDFDocument32 pagesBrancacci Antistene Pensiero Politico PDFDaniel PerronePas encore d'évaluation

- Mary B. Hesse Models and Analogies in ScienceDocument185 pagesMary B. Hesse Models and Analogies in ScienceDaniel Perrone100% (2)

- Isaacs - Proto-Racism in Graeco-Roman AntiquityDocument17 pagesIsaacs - Proto-Racism in Graeco-Roman AntiquityDaniel PerronePas encore d'évaluation

- Thilly - Kant and Teleological EthicsDocument17 pagesThilly - Kant and Teleological EthicsDaniel PerronePas encore d'évaluation

- Silber - The Copernican Revolution in Ethics. The Good Re-Examined (Kant.1960.51.1-4.85)Document17 pagesSilber - The Copernican Revolution in Ethics. The Good Re-Examined (Kant.1960.51.1-4.85)Daniel PerronePas encore d'évaluation

- TurriDocument11 pagesTurriZenón DeviaggePas encore d'évaluation

- NUDLER (2011), Controversy SpacesDocument99 pagesNUDLER (2011), Controversy SpacesDaniel Perrone100% (1)

- Kant 2011 015Document11 pagesKant 2011 015Daniel PerronePas encore d'évaluation

- Burnet - Plato's PhaedoDocument328 pagesBurnet - Plato's PhaedoDaniel Perrone100% (4)

- Lendvai - Concept and Use of The 'Historical Sign' in Kant's Philosophy of HistoryDocument8 pagesLendvai - Concept and Use of The 'Historical Sign' in Kant's Philosophy of HistoryDaniel PerronePas encore d'évaluation

- Vuk Stefanovic Karadzic: Srpski Rjecnik (1898)Document935 pagesVuk Stefanovic Karadzic: Srpski Rjecnik (1898)krca100% (2)

- Eudaimonism A Brief Reception History PDFDocument8 pagesEudaimonism A Brief Reception History PDFDaniel PerronePas encore d'évaluation

- Rare Kants BooksDocument6 pagesRare Kants BooksDaniel PerronePas encore d'évaluation

- EngstromWhitingReview PDFDocument8 pagesEngstromWhitingReview PDFDaniel PerronePas encore d'évaluation

- Knox - Hegel's Attitude To Kant's (Kant.1958.49.1-4.70)Document12 pagesKnox - Hegel's Attitude To Kant's (Kant.1958.49.1-4.70)Daniel PerronePas encore d'évaluation

- Allison - Kant's Concept Ofthe Transcendental Object (1968.59.1-4.165) PDFDocument22 pagesAllison - Kant's Concept Ofthe Transcendental Object (1968.59.1-4.165) PDFDaniel PerronePas encore d'évaluation

- Griffiths - Kant's Psychological HedonismDocument11 pagesGriffiths - Kant's Psychological HedonismDaniel PerronePas encore d'évaluation

- Bondeson - Perception, True Opinion and Knowledge in Plato's TheaetetusDocument13 pagesBondeson - Perception, True Opinion and Knowledge in Plato's TheaetetusDaniel PerronePas encore d'évaluation

- Beck - Apodictic Imperatives (Kant.1958.49.1-4.7)Document18 pagesBeck - Apodictic Imperatives (Kant.1958.49.1-4.7)Daniel PerronePas encore d'évaluation

- Plato's Parmenides and Theaetetus Order DebateDocument4 pagesPlato's Parmenides and Theaetetus Order DebateDaniel PerronePas encore d'évaluation

- Sachs - Observations On Plato's Cratylus PDFDocument11 pagesSachs - Observations On Plato's Cratylus PDFDaniel PerronePas encore d'évaluation

- Instruction Hal Leonard Music Theory For Guitarists Review PDFDocument3 pagesInstruction Hal Leonard Music Theory For Guitarists Review PDFnitish nair0% (3)

- Arranging Guidelines: Yale CollegeDocument6 pagesArranging Guidelines: Yale Collegemoromarino3663Pas encore d'évaluation

- A Short Adaptation of James and The Giant PeachDocument13 pagesA Short Adaptation of James and The Giant PeachmiddleCmusicPas encore d'évaluation

- Florence + The Machine - Stand by Me (Cover)Document2 pagesFlorence + The Machine - Stand by Me (Cover)Cariss CrosbiePas encore d'évaluation

- Natya ShikaraDocument55 pagesNatya Shikararaaz_chitraPas encore d'évaluation

- 4-way switch wiring diagram for a 2 pickup guitarDocument1 page4-way switch wiring diagram for a 2 pickup guitarNebojša JoksimovićPas encore d'évaluation

- A Musical Fantasy: Commissioned by KunstfactorDocument3 pagesA Musical Fantasy: Commissioned by KunstfactorMarlon AgapitoPas encore d'évaluation

- Program Prosposal1Document2 pagesProgram Prosposal1Jobelle De Vera TayagPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Sofar Sounds NCDocument14 pagesCase Sofar Sounds NCAnchal Gupta SinghalPas encore d'évaluation

- I Feel PrettyDocument1 pageI Feel Prettysaaalaaah0% (1)

- Romantic Period in MusicDocument4 pagesRomantic Period in Musiccarlos nolascoPas encore d'évaluation

- Tom Quayle - Have Yourself A Merry Little Christmas PDFDocument2 pagesTom Quayle - Have Yourself A Merry Little Christmas PDFLuis Carlos RodriguesPas encore d'évaluation

- 10cc - Don't Hang Up (Bass)Document4 pages10cc - Don't Hang Up (Bass)Anonymous 5EVS9avPas encore d'évaluation

- Scaldaferri 2022 Zampogne PollinoDocument28 pagesScaldaferri 2022 Zampogne PollinokagwlegalPas encore d'évaluation

- ITV Christmas HighlightsDocument41 pagesITV Christmas HighlightsLukáš PolákPas encore d'évaluation

- Ghetto Joshua SobolDocument6 pagesGhetto Joshua SobolChristos Nasiopoulos50% (2)

- May 2007Document1 pageMay 2007rmcelligPas encore d'évaluation

- Students RollDocument8 pagesStudents RollkaamaayanamPas encore d'évaluation

- EF3e Intplus Filetest 07aDocument4 pagesEF3e Intplus Filetest 07aviktorialarinPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction to Literature Forms, Divisions, and SubgenresDocument4 pagesIntroduction to Literature Forms, Divisions, and Subgenresnoriko0% (1)

- CPEBACH Counterpoint ContestDocument1 pageCPEBACH Counterpoint ContestRicardo SalvadorPas encore d'évaluation

- Nearer My God To Thee Hymn Sheet MusicDocument1 pageNearer My God To Thee Hymn Sheet MusicAriel GalvánPas encore d'évaluation

- The Song Machine Inside The Hit Factory PDFDocument246 pagesThe Song Machine Inside The Hit Factory PDFNando SilvaPas encore d'évaluation

- Meeting Miss Irby PreviewDocument16 pagesMeeting Miss Irby PreviewJosh IrbyPas encore d'évaluation

- How To Pass The Bar Exam Seminar by Atty Jim Lopez of Up LawDocument28 pagesHow To Pass The Bar Exam Seminar by Atty Jim Lopez of Up LawLorebeth España93% (14)

- Puccini Messa Di Gloria Programme NotesDocument4 pagesPuccini Messa Di Gloria Programme NotesHansPas encore d'évaluation

- Dies Irae A Guide To Requiem MusicDocument730 pagesDies Irae A Guide To Requiem Musicbobjoeman100% (1)

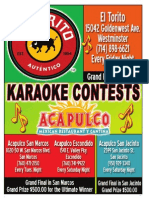

- Karaoke Scene Magazine1Document30 pagesKaraoke Scene Magazine1Yunran100% (1)

- Research TaskDocument7 pagesResearch Taskapi-663899245Pas encore d'évaluation

- Definition of Song: A. Intro B. VerseDocument3 pagesDefinition of Song: A. Intro B. VerseRika Rahayu NingsihPas encore d'évaluation