Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

MRT Working Paper

Transféré par

mymarvelousdd0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

217 vues36 pagesMRT WORKING PAPER

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentMRT WORKING PAPER

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

217 vues36 pagesMRT Working Paper

Transféré par

mymarvelousddMRT WORKING PAPER

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 36

The Center for Transportation and Logistics Studies (PUSTRAL)

Universitas Gadjah Mada

Bulaksumur E-9 Yogyakarta 55281

Tel. +62-274-556928, 6491075. Fax. +62-274-6491076

Email: pustral-ugm@indo.net.id

Project website: www.great.pustral-ugm.org

Governance Reform initiativE in trAnsporT sector Project

GREAT-Project

pustral-ugm

Working Paper 06

Case Studies of Mass Rapid Transit (MRT),

Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) and Transit Oriented

Development (TOD)

Authors

Professor John Black (University of Sydney)

Harya Setyaka S Dillon (Urban and Regional Development Institute, Jakarta)

The Center for Transportation and Logistics Studies (PUSTRAL)

Universitas Gadjah Mada

Bulaksumur E-9 Yogyakarta 55281

Tel. +62-274-556928, 6491075. Fax. +62-274-6491076

Email: pustral-ugm@indo.net.id

Project website:www.great.pustral-ugm.org

Governance Reform initiativE in trAnsporT sector Project

GREAT-Project

Working Paper 06

Case Studies of Mass Rapid Transit (MRT),

Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) and

Transit Oriented Development (TOD)

Authors:

Professor John Black (University of Sydney)

Harya Setyaka S Dillon (Urban and Regional Development Institute, Jakarta)

This research is funded through the Australia Indonesia Governance Research Partnership - an Australian Government

initiative managed by the Crawford School of Economics and Government at the Australian National University

Disclaimer:

The content of the report is solely the responsibility of the researchers and does not represent the policy of The Australian

National University nor The Australian Government

pustral-ugm

Working Paper 06:

Case Studies of Mass Rapid Transit (MRT),

Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) and Transit Oriented Development (TOD)

2

Perpustakaan Nasional : Katalog Dalam Terbitan (KDT)

Working Paper 06 Case Studies of Mass Rapid Transit (MRT), Bus Rapid

Transit (BRT) and Transit Oriented Development (TOD)/ authors,

John Black, Harya Setyaka S Dillon, -- Yogyakarta :

Pusat Studi Transportasi dan Logistik,

Universitas Gadjah Mada, 2008.

32 hlm.; 28 cm.

ISBN 978-979-19115-5-9

1. Working Paper. I. John Black. II. Harya Setyaka S Dillon

001.42

GREAT-Project

3

Foreword

The GREAT research project aims to provide material and recommendations that can later

form policy guidelines for Indonesia as well as appropriate training modules/activities for policy makers,

regulators, project developers and academics to promote transparent and accountable transport

infrastructure delivery and services. That such an approach is needed is underscored in the Vancouver

Framework for Enhanced Public-Private Partnerships for Infrastructure Development with its voluntary

principles of sound and stable economic and legal frameworks, transparent and accountable processes,

appropriate risk management, and ensuring that the infrastructure supports the achievement of

economic, environmental and social goals, and the follow up report with practical recommendations

for governments, private partners and the financial sector (Pacific Economic Cooperation Council,

2006).

The GREAT project focuses primarily on land transport (roads, bridges, tunnels, rail, monorail,

and bus systems). The research project covers the following sub-themes:

a. Subsidy policy and public service obligation in transport services;

b. The design of concession agreements for private sector-financed projects in transportation

infrastructure and service provision (including the role of government subsidies);

c. Policy and regulatory frameworks for contracting and procurement for transport projects, especially

strategic planning and the scoping of work for transparent guidelines for private finance initiatives

(PFI).

The project identifies the current situation in Indonesia, as well as indicates the possible future

scenarios about policy and regulatory frameworks for contracting and procurement in the both public

and privately-financed transport projects.

The outline of the methodology of the project takes the following steps:

a. Stock-take current Indonesian policies on the concession agreement for private sector financed-

transport infrastructure, design of tariff and user charges, and subsidy policy for transport services;

b. Study the sustainable planning and assessment guidelines based on Australian experience, and

other relevant overseas experience;

c. Identify common transport sector policies in Indonesia and Australia related to procurement,

concession agreement, user charge design and subsidy policy;

d. Indicate the appropriate and feasible reform framework, policies and strategies that can be applied

to the Indonesian transport sector; and

e. Consolidate the findings in training packages that eventually will form the basis of Indonesian PPP

guidelines and contribute to the on-going Government of Indonesia initiatives (these guidelines are

not part of the GREAT research design and deliverables).

During the progress of the research, 7 (seven) working papers have been produced with the

following titles:

WP 01 : Action Research Methodology

WP 02 : The Development of Indonesian Toll Road

WP 03 : Review of Public Service Obligation in the Transport Sector: Way Forward for Indonesia

WP 04 : Subsidies, Community Service Obligations and Concessions in the Transport Sector

WP 05 : Public - Private Partnerships (PPP) and the Australian Transport Sector

WP 06 : Case Studies of Mass Rapid Transit (MRT), Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) and Transit Oriented

Development (TOD)

WP 07 : Indonesian Local Government Perspectives on Public Private Partnerships and Capacity

Building Needs

This Working Paper 06 will describe several case studies of Mass Rapid Transit (MRT), Bus

Rapid Transit (BRT) and Transit Oriented Development (TOD) in Indonesia, Australia and Japan.

Further, explanation on donor agency i.e Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) as a major

player in the infrastructure development of Indonesia will also be described.

Working Paper 06:

Case Studies of Mass Rapid Transit (MRT),

Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) and Transit Oriented Development (TOD)

4

Table of Contents

Foreword 3

Introduction 5

1. Japan Bank for International Cooperation, JBIC 5

2. Jakarta MRT 7

Choice of Technology 9

The Need for Capacity Building 9

Current status 10

Sudirman Section 10

3. Planning The Urban Metro in Metropolitan Sydney 11

Liverpool to Parramatta Transitway 13

4. Busways and BRT in Nagoya 14

5. Transit Oriented Developments - Definitions from USA 15

Transit Adjacent Developments 16

TOD Objectives 16

Recommended Planning and Assessment Framework 18

a. Review of Government Policy 18

b. Study Area 19

c. Base Case Data Collection Transport and Land Use 19

d. Goals and Visions for Study Area 19

e. Evaluation of Alternatives 20

Quality of the Streetscape and Built Environment and Accessibility 20

Economic Performance 20

Environmental Performance 20

Social Diversity and Public Perception 21

Travel Behaviour 21

6. Transit Oriented Development in Japan 21

Japanese Context 21

Example Tama New Town ( , Tama Nytaun) 22

Sendai City and Miyagi Prefecture Japanese Leader in TOD Planning? 24

Land Re-adjustment Program 27

Conclusions 27

Direction and Actions 28

Acknowledgements 29

References 29

GREAT-Project

5

Introduction

The GREAT project has selected several case studies in Jakarta (Mass Rapid Transit

- MRT) and in Australia (NSW Roads and Traffic Authority busways or T-ways in the outer

suburbs of Sydney, and the North West Metro project in metropolitan Sydney and transit

oriented development (TOD) in Japan. Discussions with a wide range of stakeholders during

this research project has confirmed that TOD is an integrated land-use and transport solution

as part of urban change management and station revitalization that can add value to transport

infrastructure projects such as mass rapid transit and bus rapid transit.

The Jakarta MRT will be funded by a loan from the Japan Bank for International

Cooperation (JBIC) - expected to be signed by the end of the fiscal year 2008/9. The Japan

Bank for International Cooperation is a major player in the infrastructure development of

Indonesia, and its re-alignment with JICA as of 1 October, 2008, promises a much more

seamless approach in the cycle of projects. For this reason, the first section summarises this

re-organisation, and discusses the relevance of its current initiatives for Indonesia. The

progress of the MRT Jakarta project is also described.

In Sydney, in March, 2008, the Premier of New South Wales announced that the

Treasury would fully fund the construction of the North West Metro line as in Jakarta, it will

be the first such transport technology application. Progress with the planning of this project

is also included in this working paper, although a change in political leadership in New South

Wales and concerns about the States true financial position may mean a review in the

implementation of the NW Metro in the November, 2008 State mini-budget. Both Jakarta

and Sydney have built busways (BRT) and are operating commercial services along key

routes. These experiences, together with the key bus routes and guided busway experience

in Nagoya, Japan, where one of the authors conducted research are summarised.

It is clear from research that integrated land-use and transport projects have a greater

potential to achieve long-term, economic, social and environmental development than single,

transport mode solutions. The JIBC SAPI team gave a seminar in Jakarta in May, 2008

where rail station revitalization was recognised as a significant challenge for Jakarta, as in

other cities of the developing world considering the implementation of MRT. For this reason,

we include reference to previous research by the University of Sydney Planning Research

Centre on transit oriented development for the New South Wales Government that is updated

with some of the latest information emerging from Japan based on interviews and fieldwork

conducted as part of this GREAT project. Finally, the key findings that have relevance for

Indonesia are summarised in the conclusions.

1. Japan Bank for International Cooperation, JBIC

Phase 1 of the Jakarta Mass Rapid Transit

system will be financed by of a loan from the Japan

Bank for International Cooperation. It is the first

experience in Indonesia of designing, constructing,

operating and maintaining such a new technology. This

case study is especially timely to investigate as part

of the GREAT research project because the MRT

Jakarta Company was formed as a legal entity on 27

June, 2008, and JBIC will undergo organizational

realignment in October, 2008. Its new organizational

chart is contained in the 2007 Annual Report {Japan

Bank for International Cooperation, 2008, p. 4}. In

addition, the Japan Bank for International Cooperation

Working Paper 06:

Case Studies of Mass Rapid Transit (MRT),

Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) and Transit Oriented Development (TOD)

6

is co-financing with the Asian Development Bank (ADB) a loan amount of 11,777 million

(approximately Aus $120 million) for a Infrastructure Reform Sector Development Program

(IRSDP) to support policy and institutional reforms related to infrastructure so as to improve

the investment climate in Indonesia.

Following the passage of the Japan Finance Corporation Law on May 18, 2007, during

the 166th Ordinary Diet Session, the International Financial Operations (IFOs) of the Japan

Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC), the National Life Finance Corporation (NLFC),

the Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Finance Corporation (AFC) and the Japan Finance

Corporation for Small and Medium Enterprise (JASME) will be merged on October 1, 2008,

to become a new policy-based financing institution, tentatively called the Japan Finance

Corporation (JFC). Of the two types of operations conducted by the current JBIC, JFC will

take over IFOs in its international finance sector. However, to maintain the international trust

and confidence currently enjoyed by JBIC, the international finance sector of JFC will continue

to use the name of JBIC as it conducts international finance operations. The Japan Bank for

International Cooperation (JBIC; Governor: Koji Tanami) realigned its departments which

conduct International Financial Operations (IFOs) from July 1, 2008, with a view to responding

more flexibly and efficiently to diverse financial needs. This organisational realignment is a

reflection of the comments and desires communicated to JBIC by its domestic and overseas

clients (http://www.jbic.go.jp/autocontents/english/news/2008/000063/index.htm accessed 3

July 2008).

After the merger, all rights and obligations pertaining to IFOs of JBIC have been taken

over by the new JBIC. Therefore, there will be no adverse effects on the interests of the

clients who have been utilising the financial and other services that constitute IFOs and the

holders of securities issued by JBIC to fund IFOs. The new JBIC will devote itself to conducting

more effective and efficient operations to fulfill its mission, which includes support for

economic and social development as well as economic stability in developing countries

{Japan Bank for International Cooperation, 2008, p. 6}.

Importantly for infrastructure financing in Indonesia from 2009 onwards is that the

Overseas Economic Cooperation Operations (OECOs) of JBIC will be succeeded by the

new Japan International Cooperation Agency (new JICA) on October 1, 2008. The view of

JBIC officials is that better coordination of activities on the technical side and the aid loan

side will result from a greater sharing of knowledge and information. JIBC will be better

positioned to manage all aspects of the aid process which will be a clear benefit for recipient

governments. For example, the new organizational arrangements with JBIC and JICA are

currently developing a strategic plan for Indonesia with its preparation due for completion by

the end of September, 2008. This strategy has relevance for this GREAT project, but the

contents of the Indonesia country paper are unlikely to be released publicly during the time-

frame of this research - but they may be anticipated in early 2009.

From a foreign loan agencies perspective there are a number of bottlenecks to overcome

for more effective and efficient infrastructure delivery.

a. The slowness of the Indonesian bureaucracy to act (see the case of Jakarta transport

and its chronology in Table 1);

b. Inadequate performance of government officials in their duties;

c. Weak capacity by government officials in the understanding of the major elements of the

project cycle;

d. Problems of existing legal structures even for government-led projects, such as land

acquisition;

GREAT-Project

7

e. Extensive bidding procedures on government tenders to the considerable frustration of

the private sector; and

f. Even when loan agreement has been signed, there is a slow dispersal of funds, or no

action at all.

These, and other problems, are fully documented in the on-going study ADB-JBIC co-

financed Indonesia Reform Sector Development Program, IRSDP. The World Bank is also

carrying out a similar exercise in IDPL.

2. Jakarta MRT

As for specific issues on the MRT Jakarta loan, work is still underway in loan preparation,

especially due diligence, and there is an expectation that the loan will be signed by

representatives of the Indonesian Government by the end of this financial year, which is the

end of March, 2009. The financial structure of the MRT project is currently unclear, although

5 scenarios have been suggested by the Japanese consultants. Much is dependent on the

policy direction from the Indonesian government and any legal restrictions for example,

the Thai government has preferred a PPP approach to the construction and operation of the

Bangkok metro system. Indonesian Government policy is required on the subsidy issue, in

particular to assist the mobility of low income residents of Jakarta.

Table 1. Numerous Plans for Transport in Jakarta and Lack of Implementation

No Year Implementer Title

1. 1978 JICA Study of Jakarta Ring-Road Project

2. 1981 JICA Urban-Suburban Railway Transportation in Jabotabek

3. 1981 Cipta Karya Jakarta Metropolitan Development Planning

4. 1990 JICA Integrated Transportation System Improvement by Railway and Feeder Service in Jabotabek Area

5. 1990 JICA Jakarta Mass Rapid Transit System Study (JMTSS-BPPT-GTZ)

6. 1993 Directorate General Jabotabek Mass Rapid Network (TNPR)

of Land Transport

7. 1996 Jakarta Urban Busway Feasibility Study

Transport System

Integration/JUTSI

8. 1996 Recommendation on MRT Fatmawati - Kota (SAUM AJA)

9. 1997 JICA The Study on the Integrated Air Quality Management for Jakarta Area

10. 1997 World Bank Urban Air Quality Management Strategy in Asia: Jakarta Report

11. 1999 Directorate General Revised basic design study for MRT system

of Land Transport

12. 2000 JICA Study on Integrated Transportation Master-Plan I

13. 2002 JICA study on integrated transportation master-plan II

14. 2003/2004 Jakarta Provincial Macro-Level Transportation Pattern

Government

15. 2003 ADB, The Integrated Vehicle Emission Reduction Strategy for Greater Jakarta

16. 2006 ADB Urban Air Quality in Indonesia (UAQI)

Future projects of MRT in Jakarta, or in any other city of the developing world, could be

formulated as integrated station development, or transit oriented developments, TOD, and

rail construction operation and maintenance, and JBIC loan applications could be made for

such integrated projects in the future. Private-sector involvement in land assembly,

architectural design and building development would be required with a PPP partnership

Working Paper 06:

Case Studies of Mass Rapid Transit (MRT),

Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) and Transit Oriented Development (TOD)

8

clearly articulated within a coherent policy framework for all parties concerned. This is also

recognised as a future potential project by MRT Jakarta for funding (see also, JBIC Study

Team, 2008) and for this reason a later section of this Working Paper is devoted to the

important topic of transit oriented development and the creation of more sustainable cities.

Total project cost of The Jakarta MRT System Project is Rp 10.264 trillion. This project

is funded by JBIC loan (96.1 billion or Rp 8.359 trillion), State budget (APBN) Republic of

Indonesia (Rp 1.254 trillion) and Provincial Governments budget (APBD) Province of DKI

Jakarta (Rp 651 billion).

a. Detail specification of loan portion to MOF is as follows:

b. interest rate: 0.4%

c. length payment period: 30 years 6 months

d. grace period: 10 years

As agreed, this loan will be channeled in two loan steps, Loan Agreement 1 (LA1) and

Loan Agreement 2 (LA2). LA 1 totals Rp 163 billion, and is used to fund the Planning, Design

and Engineering Phase. LA 2 is estimated at Rp 8.196 trillion and will be used to fund the

Construction Phase. To date, LA 2 is under negotiation.

The funding process is as follows. 58% of the total loan will be in the form of on-

lending to DKI Jakarta provincial government with an interest of 0.9%. The rest of the loan

(42%) will be in the form of on-granting to DKI Jakarta provincial government. Therefore,

the Central Government is liable for 42% of the total loan, and the DKI Jakarta provincial

government is liable for 58%.

Afterwards, the DKI provincial government will channel the 58% loan from Ministry of

Finance to the MRTC (MRT Company, PT MRT Jakarta, a special purpose vehicle company

for the project) through an on-lending scheme, while the other 42% will be channelled to

MRTC as a form of equity and subordinated loan, amounting to Rp 2.018 trillion and Rp

1.342 trillion, respectively. Within this whole funding process, DKI will only act as the distributor

of loan as well as the shareholder.

Payback of the loan from MRTC to the DKI provincial government is in IDR currency,

while from DKI to MoF and then MoF to JBIC are in the form of Japanese Yen currency. This

condition implies that the DKI provincial government must prepare themselves with adequate

currency hedging fund in order to avoid any potential currency risk. Forecasted currency

hedging fund is Rp 353 billion for the payment period.

State budget APBN portion of the funding will be provided in the form of administration

process and tax exemptions to support the construction phase. Land acquisition and working

capital of the MRTC in its pre-operation phase will be funded by the DKI Jakarta Budget

(APBD). This is done by establishing MRTC (PT MRT-Jakarta) as a company owned by DKI

Jakarta (provincial government owned enterprise/BUMD).

To render the MRT project successful, DKI and MRTC need to secure all their needs in

the upfront concession agreement. All parties will strictly follow the agreement to secure

MRTC financial sustainability in the future. This concession will consist of a financial structure,

a commercial structure and an ownership structure.

As regional regulator, DKI will support MRTC with regulations pertaining to:

a. financial structure - to sustain MRTC cash flow in the future by injecting equity and subsidy;

b. commercial structure :-to make a conducive business environment;

GREAT-Project

9

c. ownership structure - to clarify assets ownership and concession agreement.

As the major shareholder, DKI injects equity in the form of land acquisition (Rp 161

billion) and working capital (Rp 490 billion) before the MRTC starts its Operation Phase. This

number (Rp 651 billion) will be counted as equity in the MRTC balance sheet. For sustaining

a financial cash flow for MRTC, DKI will inject Rp 85 billion annually in the form of subsidy for

10 years, totaling Rp. 850 billion.

Therefore, DKIs main financial responsibilities are hedging costs and providing subsidy.

It is vital that DKI carefully and prudently steward its fiscal capacity for the scheduled

disbursements.

In the case of ownership, MRTC will own all assets, including infrastructure and facilities

(rolling stock). With full asset ownership, it is expected that MRTC will operate to its best

performance.

Choice of Technology

As a JICA/JBIC funded project, the loan agreement for MRT stipulates the following:

a. Local content, up to 30%

b. Japanese content, at least 30%

c. Joint venture with Japanese shareholder; 40% in which the Japanese counterpart shall

own 51% of the share and others up to 49%.

d. In reality then, it is 70% Japanese, 30% (maximum) local.

Such circumstances call for a strategy and negotiation to safeguard national interest

and ensure value for money in the project. After all, as it is the Indonesian counterparts who

pay in the end there must be assurance that the money spent is money well spent.

As an answer to this challenge, MRTC commissioned an independent (non-Japanese)

technological appraisal to ensure value for money in choice of MRT technology. The

consultancy service is provided with local funding to maintain independence from outside

interest. In this regard, MRTC have closely followed the Indian experience in negotiating

with the Government of Japan. The Indians managed to out-savvy their Japanese partners

by procuring a Japanese technology (Japanese content) at a Korean priceJapanese

design, Japanese materials, Korean manufacturing. This was made possible because the

Korean company was at the end of the outsourced assembly line. Although the end product

was made in Korea, the Japanese component-requirement was met.

The Need for Capacity Building

Traditionally, officers of the government of Indonesia were trained as a law and order

person. Not many senior officers within the DKI Government are equipped with basic

knowledge/skills in accounting. This is a challenge in pushing forward the MRT project,

which is a large-scale infrastructure project necessitating capacity building in the business

process. Asset management is also an issue. The DKI Government must ably secure all

assets pertaining to the MRT project, andbe best equipped with a team of legal advisors to

provide stewardship along the key stages of the project.

As earlier mentioned, this large scale project will need decision makers with sufficient

business and financial intelligence. Unfortunately, such endowments are not the strong points

of the public sector in Indonesia. The Monorail project is an example of what not to do.

Working Paper 06:

Case Studies of Mass Rapid Transit (MRT),

Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) and Transit Oriented Development (TOD)

10

Furthermore, negotiation skills will come in handy, as the project will largely deal with Japanese

interest. Such skills would render more value for money to the Indonesian people.

Current status

PT MRT Jakarta (MRTC) was established in June 2008, ending a lengthy debate in the

Municipal Council on the MRT project. As anticipated, the early stages will be bumpy. Project

stakeholders must clearly understand their roles in the project and avoid unnecessary dispute

on who does what and who gets what. MRTC is firm that all the legal procedural details are

in place as a ruling to the above concern.

PT MRT Jakarta (MRTC) was established in June 2008, ending a lengthy debate in the

Municipal Council on the MRT project. As anticipated, the early stages will be bumpy. Project

stakeholders must clearly understand their roles in the project and avoid unnecessary dispute

on who does what and who gets what. MRTC is firm that all the legal procedural details are

in place as a ruling to the above concern.

Unfortunately as of November 2008, loans for infrastructure construction are yet to be

finalized. Delays in loan disbursement will cause delay in the subsequent phases. To improve

intermodal connectivity, the Governor has sanctioned for the development of intermodal

station in Dukuh Atas. Following Shinjuku station TOD concept, this station will connect the

BRT, MRT, commuter rail (KA Jabodetabek), Monorail (if and when implemented) and the

airport-rail link.

Sudirman Section

Figure 1 Planned MRT System for Jakarta 2015, including the 1

st

MRT Route (shown in black) from Lebak Bulus to

Dukuh Atas

Source: Jakarta Transportation Agency

GREAT-Project

11

3. Planning The Urban Metro in Metropolitan Sydney

The current metropolitan plan City of Cities: A Plan for Sydneys Future (2005) - is a

whole of Government document endorsed by the Cabinet. The lead agency in the formulation

of this strategy is the NSW Department of Planning. The Metro Strategy is significant because

it embodies real and significant policy decisions by Government, including the implementation

mechanisms to translate the Plan with 231 actions. These mechanisms include the Metro

CEOs group and the linkage between the Metro Strategy, the State Infrastructure Strategy

and the State Budget process. It is a whole of Government strategy, adopted by cabinet as

the planning and development framework for the next 25 years.

The two new railway lines in the strategy link the north-west and south-west growth

centres into the metropolitan rail network, and the new CBD line will further enhance the

public transport accessibility of the CBD and North Sydney. In December, 2006, the Premier

of New South Wales released a statement on passenger transport and committed to a detailed

investigation of a high speed railway connecting Penrith, Parramatta and the city centre. By

2008, a metro-style system had replaced the suburban railway plan for the north-west sector

(Figure 2).

On March 18, 2008 the Premier of New South Wales unveiled a $12 billion (escalated

cost for completion in 2017) European-style metro for the 38 km route from Rouse Hill in the

northwest growth sector of Sydney to the CBD (Australia, New South Wales Government,

2008, p. 3). It is important to emphasise that these initiatives arose from a strategic plan for

passenger transport in Sydney - the Premiers Urban Transport Statement released in

November, 2006 (http://www.nsw.gov.au/urban_transport.asp ). The section of the route from

Rouse Hill to Epping had already been subject to environmental assessment as a heavy rail

line had been proposed as part of Sydneys Metropolitan Strategy in 2005.

Figure 2 Major New Railway Lines Proposed under the 2005 Metro Strategy

Working Paper 06:

Case Studies of Mass Rapid Transit (MRT),

Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) and Transit Oriented Development (TOD)

12

A confidential report - Sydney Transport Review - written by Jim Steer, a world-leading

transport consultant and executive with Britains former Strategic Rail Authority, says the

planned 38-kilometre Euro-style subway - from Rouse Hill to St James Station - is too long to

be viable as a metro, is predicated on a poor business case

1

. Among other criticisms is that

the north-western half of the metro would service a low-density and fairly affluent area that is

wedded to its cars. With 30 kilometres of tunnel, it would be hugely expensive with no

guarantee of high patronage.

Figure 3 Proposed North West Metro Line, Sydney, March 2008

Source: http://www.sydlink.com.au/site/page.cfm?u=26, accessed 6 May, 2008

Notwithstanding this, the Premiers Urban Transport Statement also anticipated that

the West Metro to Parramatta and the South East Metro to Malabar would be priorities for

investigation. Whereas the Premiers press release emphasised that the North West Metro

(Figure 3) had been included in the States forward budget there is likely to be opportunities

for private sector involvement. An invitation by Government to the private sector companies

to hear of business opportunities with MRT was held in Sydney on DATE??? This could

take the form of private-sector operations and maintenance of the North West Metro and

greater participation in the funding and operations of other, future, lines. The meeting called

for invitations to tender for a shadow operator of MRT to assist in the design of the total

system. The shadow operator is ineligible to become a tenderer for the Sydney NW Metro.

On May, 15, 2008, two alternative metro routes connecting the CBD to Parramatta,

and costing of upwards of $10 billion, were unveiled by the Premier of New South Wales, as

part of a possible network expansion (Figure 4). The Government indicated that it was

seeking Federal funding for this (and other major road infrastructure in Sydney) but that they

still might to turn to the private sector for partnerships (The Sydney Morning Herald, 15 May,

2008, p. 2)

GREAT-Project

13

Figure 4 Possible Metro Lines for Metropolitan Sydney Under Consideration

Source: Metro Strategy, 2005

Liverpool to Parramatta Transitway

The NSW Government began contemplating major non-rail public transport solutions

for its low density western suburbs in the early 1980s, even reserving two public transport

corridors aimed at bringing a transit service such as light rail to new residents of release

areas then being planned. A regional environmental plan was promulgated. The Sydney

Regional Environmental Plan No. 18 Public Transport Corridors which aimed to:

a. make provision for future public transport facilities,

b. improve accessibility by public transport to centers of commerce, recreation, education,

culture and employment,

c. improve, and extend, the existing regional public transport network, and increase the

range of public transport facilities available to residents of the region,

d. identify certain pieces of land as public transport corridors,

e. provide for the acquisition of certain land for the purposes of the public transport corridors

so identified,

f. control the carrying out of development within the public transport corridors so identified,

and

g. require consent authorities, when considering development applications in respect of

land in the vicinity of a public transport corridor, to take into account the effect of the

proposed development on the development of the public transport corridor.

However, the political and financial commitment to these corridors was not forthcoming

for another 15 years (under the NSW Governments adventurous Action for Transport 2010

program), ).but by that time, low-density land development had taken place in many areas

and compromises had been made to the modest 20m wide corridor (such as co-location of

electricity easements, rear fences of houses abutting the corridor and incorporation of the

corridor into local streets with regular driveway access). Zonings along the corridor did not

reflect any major departures from that of adjacent areas. These indicators suggest that TOD

Working Paper 06:

Case Studies of Mass Rapid Transit (MRT),

Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) and Transit Oriented Development (TOD)

14

was not at the forefront of the thinking of government planners, let alone that there was

confidence in the delivery of a transport project.

The induction into development of these transport corridors came with the commitment

to a rapid bus roadway (Transitway) project between Liverpool and Parramatta. This prototype

(for Sydney) was not the most glorious of starts for application of land-use and transport

integration and project delivery due to mis-timing. While the route was reconsidered in parts

so that it could better link land-use activity and employment nodes (Faber, 2005), and reference

was given to progressive integrated land-use objectives in the Environmental Impact

Assessment (Sinclair Knight Merz 2000), the urban change agenda fundamentally suffered

from:

a. the already established car-dependent, low density residential and employment

environment where house values and consumer preferences have not been such to entice

medium density, let alone high density residential developments or employee-intensive

commercial uses;

b. multiple and small lot land ownership that compound inter-agency coordination problems

and introduce funding barriers;

c. un-met urban structure retro-fitting needs brought on by the use of a wide, sometimes

flood affected, and limited access, road corridor. The physical environment through which

the LPT runs and consequent urban design approach bears some resemblance to

Adelaides linear park along the O-bahn system, which, on one hand, seeks to screen the

surrounding residents from noise and other impacts and to be visually pleasant, but at the

same time restricts urban change opportunities.

Delivering a multi-faceted transport and urban change program takes time, bravado

and stamina by a number of agencies. Planning is the easy bit - at implementation the

rhetoric can be exposed. With the comfort of hindsight, the examples of where things went

wrong are rife.

a. Once the approval green light was given, infrastructure delivery became sacrosanct and

isolated from risky activities such as bus servicing strategies (due to a hostile bus industry

pre-reform) and land-use speculation (which was seen as an electoral threat due to then

community disquiet over urban consolidation).

b. The urban change agenda, when it was finally broached, tended to be oriented towards

where the (car dependent) real estate market was at - not at where the need for Government

intervention was required for urban structure retrofitting and possible development

incentives to deliver these. The matter was dealt with at a strategic level only and rarely

translated to implementation at a local government level.

4. Busways and BRT in Nagoya

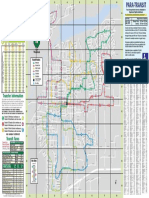

Figure 5 shows a map of the public transport network of Nagoya, together with

photographs of the bus priority the first in Japan - and the guided busway system. These

two systems are poorly integrated with adjacent land uses and stations. Spatial development

has not occurred along the routes and hence patronage is about half that projected (see

Figure 6).

GREAT-Project

15

Figure 5 Nagoya Busway Routes and Photographs of Key Bus Routes and Guided Bus

Figure 6 Failure for TOD to Follow the Guided Bus Route in Nagoya and Implications for Patronage and Business

5. Transit Oriented Developments - Definitions from USA

A search of the international, especially the US literature (for example, Cervero, et al.,

2004) by the Planning Research Centre with Jackson Teece Architects (2007), suggests that

a true TOD includes:

a. Development that lies within a five-minute walk of the transit stop, or about a quarter-mile

from stop to edge. For major stations offering access to frequent high-speed service this

catchment area may be extended to the measure of a 10-minute walk.

b. A balanced mix of uses of residential and commercial space located adjacent to a major

transit stop with a 24-hour ridership

c. A place-based zoning code at or near transit stops that generates buildings that shape

and define memorable streets, squares, and plazas, while allowing uses to change easily

over time.

d. A built form with public transit included that presents an average block perimeter limited

to no more than 1,350 feet. This generates a fine-grained network of streets, dispersing

traffic and allowing for the creation of quiet and intimate thoroughfares.

Working Paper 06:

Case Studies of Mass Rapid Transit (MRT),

Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) and Transit Oriented Development (TOD)

16

e. Minimum parking requirements are abolished since the goal is to reduce private motor

vehicles and make them more, and not less, convenient for pedestrians and users of

public transport.

f. Maximum parking requirements are instituted as a counter to the usual notion of providing

parking for every peak demand. For every 1,000 workers, no more than 500 spaces and

as few as 10 spaces are provided.

g. Parking costs in TOD are unbundled, and full market rates are charged for all parking

spaces to promote less car use.

h. Major stops provide Bike Stations, offering free attended bicycle parking, repairs, and

rentals. At minor stops, secure and fully enclosed bicycle parking is provided.

i. Transit service is fast, frequent, reliable, and comfortable, with headways of 15 minutes,

or less.

j. Roadway space is allocated and traffic signals timed primarily for the convenience of

walkers and cyclists.

k. Traffic is calmed, with roads designed to limit speed to 30 mph (50km/h) on major streets

and 20 mph (30km/h) on lesser streets.

Transit Adjacent Developments

A related concept but at the opposite end of the spectrum to a TOD - is a transit-

adjacent development (TAD). The urban design of a TAD is usually focused on automobiles

and parking. TADs are difficult for pedestrians and bicyclists, which discourages public

transport usage. One of the best examples in the world of a transit station that was originally

a Transit Adjacent Development (TA) and later redeveloped into a TOD, is Subiaco, Western

Australia. The difference between TOD and TAD are illustrated in Figure 7.

TOD Objectives

The US Federal Mass Transit Administration emphasizes the integration of complete

systems and not just a partial transport program. They are guided by:

a. The impact of the transit on auto use reductions of greenhouse gases;

b. The opportunity for transit to support high density residential development;

c. The integration of a variety of development forms;

d. The capacity of the system and flexibility to add new components or be used by other

segments of a system such as bus lanes to rail lanes

e. The innovations in transit on the routes such as low impact vehicles, alternative fuels and

related innovations;

f. The cost per passenger mile and social equity of the system;

g. The contribution of local taxes and other revenues in the effort.

TOD Goals The absence of any working definition of TOD hampers the ability to set

agreed upon goals. However, some guidance may be drawn from the relative frequency of

goals as stated by public transport agencies in the USA, which are to:

GREAT-Project

17

a. Increase public transport ridership (20 per cent of stated goals)

b. Promote economic development (16 per cent)

c. Raise revenues (13 per cent)

d. Enhance liveability (11 per cent)

e. Widen housing choices (9 per cent).

Role of Governments Possible roles for state governments in the USA include:

a. Promote co-ordination

b. Forge collaborative working relationships

c. Develop a set of goals to promote TOD

d. Implement programs and funding initiatives that achieve these goals

e. Provide financial incentives

f. Remove regulatory and statutory barriers to land use

g. Promote public sector private sector partnerships

h. Promote planning, policy research, technical assistance, and information support, and

help local governments employ innovative redevelopment strategies

i. Establish pilot programs to test and show by example how the new modes of thinking can

work in practice.

Transit-Oriented Development Transit-Adjacent Development

Working Paper 06:

Case Studies of Mass Rapid Transit (MRT),

Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) and Transit Oriented Development (TOD)

18

Recommended Planning and Assessment Framework

a. Review of Government Policy

Planning for transport in cities takes place within a regulatory and policy framework. In

terms of broad planning policy directions, all levels of government in Australia are adopting

sustainability as the overarching goal the triple bottom line of economic, social and

environmental outcomes. Internationally, green transport modes (specifically, public

transport, and facilities for pedestrians and cyclists) are widely promoted in government

vision documents on sustainable metropolitan transport aimed at achieving more sustainable

cities. These generalisations are only a reminder that the first step in planning a transitway

and transit oriented development in a specific metropolitan corridor is to identify the relevant

policies of government that bear on the subject matter. In New South Wales, this will entail a

review of both state and local government policies.

There is a need for new institutional arrangements that take a holistic approach to the

problem of integrating land use along public transport corridors. The role of government in

the planning of transit oriented development is to:

- Forge collaborative working relationships

- Promote co-ordination

- Develop a set of goals to promote TOD

- Implement programs and funding initiatives that achieve these goals

- Provide financial incentives

- Remove regulatory and statutory barriers to land use

Transit-Oriented Development Transit-Adjacent Development

Copyright Photo Credits (Clockwise starting at the upper left photo): John Renne, John Renne, John Renne, Subiaco

Redevelopment Authority, Urban Land Institute, Urban Land Institute, Subiaco Redevelopment Authority, John Renne

Figure 7 The Difference between Transit-Adjacent Development and Transit-Oriented Development

GREAT-Project

19

- Promote public sector private sector partnerships

- Promote planning, policy research, technical assistance, and information support, and

help local governments employ innovative redevelopment strategies

b. Study Area

The boundary of the relevant study area for investigation is identified taking into account

the route location, or alternatives, for the transitway. Although this will be a corridor, the inter-

change and inter-connectivity of bus routes dictates that the area of influence of public

transport will extend beyond the study area of relevance in the planning of transit oriented

development.

c. Base Case Data Collection Transport and Land Use

As with the environmental impact assessment (EIA) of any major development, the

base case situation (without the proposed transitway and associated transit oriented

development) must be established from data routinely collected by governments, or from

special surveys, including the convening of stakeholder workshops to tease out all relevant

information.

A specific transit oriented development will have plural goals. These relate to:

- Institutional Performance

- Quality of the Streetscape and Built Environment and Accessibility

- Economic Performance

- Environmental Performance

- Social Diversity and Public Perception

- Travel Behaviour.

Base-line data, before any transit oriented development can be planned, must be

collected to determine feasibility of a proposal. If a new transport link has been proposed,

such as a busway, transitway, or light/heavy rail, the environmental impact statement (EIS)

will provide information on the current land use and transport situation.

d. Goals and Visions for Study Area

Implicit in any planning of a TOD project is the articulation of goals and a vision for the

study area. The planning of transit oriented developments will generate alternative urban

design concepts for the same locality sometimes with conflicting goals and trade-offs

depending on the local circumstances, and these must be tested for commercial feasibility,

probably involving re-zoning and the like.

It is clear that TOD goals must be agreed upon in the local context through stakeholder

workshops and other forms of community participation. For these reasons, experience is

sometimes hard to transfer from the international experience. The absence of any universal

working definition of TOD hampers the ability to set agreed upon goals. However, some

guidance may be drawn from the relative frequency of goals as stated by public transport

agencies in the USA which are to:

- Increase public transport ridership;

Working Paper 06:

Case Studies of Mass Rapid Transit (MRT),

Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) and Transit Oriented Development (TOD)

20

- Promote economic development;

- Raise revenues;

- Enhance livability; and

- Widen housing choices.

e. Evaluation of Alternatives

Quality of the Streetscape and Built Environment and Accessibility

The streetscape and associated buildings should be of high quality. The road

environment should encourage pedestrian activity with slow vehicular speeds and bus stops

(and access modes such as bicycles) designed as an integral part of the overall concept.

Such public transport nodes are attractive to developers of residential properties.

One aspect of residential amenity is accessibility to a wide range of urban goods and

services such as employment, education, retailing, health and recreation. Transit oriented

development aims for higher levels of local accessibility by providing land uses in close

proximity. Public transport confers access to destinations along designated routes. A key

factor for developers of a site is location. A strategic assessment of the proposed TOD site

and its accessibility properties is desirable and should be made in comparison with accessibility

by car as the main competing mode. The public transport services provide wider regional

accessibility as a direct alternative to the accessibility provided by the motor vehicle.

Economic Performance

Integration of complete systems, and not just a partial transport program, is the main

economic objective. Efficiency is guided by:

- the impact of the transit on auto use reductions of greenhouse gases;

- the opportunity for transit to support high density residential development;

- the integration of a variety of development forms;

- the capacity of the system and flexibility to add new components or be used by other

segments of a system such as bus lanes to rail lanes

- the innovations in transit on the routes such as low impact vehicles, alternative fuels and

related innovations;

- the cost per passenger mile and social equity of the system; and

- the contribution of local taxes and other revenues in the effort.

Environmental Performance

Road corridors have environmental loads in the form of vehicle emissions and road

traffic noise and social impacts through the road trauma. Many of these negative externalities

of private transport are in proportion to the vehicle-kilometres travelled and speed. The aim

of TOD development around busways is to reduce VKT travel by private transport and achieve

environmental benefits. This translates into reductions in vehicle emissions and energy

consumption, which must be quantified.

GREAT-Project

21

Social Diversity and Public Perception

In all mass transit systems it is important to capture all categories of riders and not

have the system just service lower income, school age or seniors. As a result, routes, quality

for the system, maintenance and reliability are key ingredients.

Travel Behaviour

Transit oriented developments are aimed at supporting the broad thrust of many

approaches throughout the world, including in Australia, of encouraging green modes of

transport to help achieve more sustainable cities. Well-designed TOD neighbourhoods also

encourage more pedestrian activity and cycling and aim to switch travel from private car to

public transport.

6. Transit Oriented Development in Japan

Time in Japan on fieldwork for this research allowed two site visits to be made: the

Tama Garden City development (and meetings with the private sector developer, Tokyu

Company in Tokyo); and the TOD plans for the City of Sendai and Miyagi Prefecture in the

Tohoku region of Japan. We also draw on previous field work conducted in Nagoya on key

bus routes and the guided bus system. The acknowledgements at the end of this working

paper indicate those people who greatly assisted in providing a great deal of information and

data some of which is summarised in this working paper.

A brief context for the issues facing urban development in Japan is given. It illustrates

this with a case study of sprawling urban development in Sendai (population: 1 million).

Sendai is currently formulating plans to implement transit oriented development (TOD) around

selected nodes of busways acting as extensions into the suburbs of the existing east-west

north-south subway system. There are many examples in Japan of coordinated land-use

and public transport development by the private sector and Tama Garden City is a good

example. The case study of investing in bus infrastructure and new bus technologies in

Nagoya emphasizes the dangers of not proceeding with a parallel suite of land use policies

to support the intensification of development at key notes that might increase patronage in

the corridor.

Japanese Context

The growth of the Japanese economy from the 1960s onwards is one of the great

Asian economic miracles of the modern era. A rapid influx of population into Tokyo led land

prices to skyrocket, causing many to settle on the cheaper outskirts of the city, leading to an

uncoordinated and unplanned, rapid urban sprawl. It was feared that, left to private sector

developer interests, the uncontrolled expansion of built-up areas would lead to poorly planned

communities with insufficient infrastructure to support the population and with poor access

to amenities and transport. Overall, the Japans New Town program consists of a many

diverse projects, most of which focus on a primary function, but also aspire to create an all-

inclusive urban environment. Japans New Town program is heavily informed by the Anglo-

American Garden City tradition, American neighborhood design, as well as Soviet strategies

of industrial development (Hein, 2003). Borrowing from the New Town movement in the UK,

some 30 new towns have been built in Japan all over the country. Most of these constructions

were initiated during the period of rapid economic growth in the 1960s, but construction

continued into the 1980s.

Working Paper 06:

Case Studies of Mass Rapid Transit (MRT),

Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) and Transit Oriented Development (TOD)

22

Example Tama New Town ( , Tama Nytaun)

There are numerous examples in Japan where the private sector has initiated and

successfully initiated a coordinated approach to land use development and public transport,

and the case study of Tama Garden City development represents one of the most successful

examples. Tama New Town is a large residential development, straddling the municipalities

of Hachiji, Tama, Inagi and Machida cities. Administratively, Tama New Town is not a

municipality in itself because it straddles the pre-existing boundaries of Tama, Hachiji, Inagi

and Machida cities, and each area is administered by its respective municipal authorities, all

of which come under the jurisdiction of Tokyo Metropolis.

It is approximately 14km long stretching east-west, and between 1 and 3km wide,

located in an expanse of hills known as Tama Hills about 20km west of central Tokyo. It

currently has a population of about 200,000, making it the largest housing development in

Japan. Planned in 1965 to attempt to ease the growth pressure in Tokyo it provides hundreds

of thousands of housing units in a planned, pleasant urban environment that was once the

former green belt encircling Tokyo. The planning and development was carried out jointly by

The Housing and Urban Development Corporation, Tokyo, the Metropolitan Housing Supply

Corporation and Tokyo Metropolitan Government. Construction began in 1966 and the first

phase opened in 1971. Construction continued in phases for the next few decades and

interviews with the development agency indicate the land bank will be exhausted by the end

of this decade.

Implementation is achieved through a super developer. Figure 8 illustrates the

components of the activities of this super developer.

Figure 8 Denen Toshi Railway Company, Tokyu Company Concept of a Super Developer

The six main characteristics of Denen Toshi Development Project are:

a. One enterprise developed both land and railway

Complete internalisation of external economy of the Railway Development.

b. Well-planned land-use and land readjustment (see below)

Infrastructure development and acquisition of land for the railway and public use.

GREAT-Project

23

c. Extension of the railway in accordance with settlement development

Stable revenue from fares.

d. Shopping complex developed by the same enterprise

agglomeration effects by economies of scale and scope.

e. Well-coordinated feeder service to the station

f. High level of accessibility to public transport

These characteristics of coordinated development have lessons for urban development

generally and for TOD in particular. Tama New Town is divided into 21 neighbourhoods,

each with about 3000 to 5000 houses and flats, each with two elementary schools and one

junior high school as well as a neighbourhood centre with shops, police station, post office,

medical clinics and so on. Several neighbourhoods form one district, each of which are

centred around a commuter rail station. Tama New Town is served by more than ten railway

stations, most of them on the Keio Sagamihara Line and Odakyu Tama Line, both of which

provide a direct service to Shinjuku Station in central Tokyo. JR Nambu Line and Tama Toshi

Monorail Line also serve the area.

Its development pre-dated the New Urbanism movement from the USA that gave rise

to transit oriented development but nevertheless the railway stations have a wide range of

urban functions located nearby. For example, the area surrounding the Tama Center Station

complex, in the municipality of Tama, is the designated centre of Tama New Town. The area

is separated into business, commercial and leisure zones. The Tama Centre Station itself is

serviced by the Tama Toshi Monorail Line, as well as Keio Sagamihara and Odakyu Tama

Railway Lines which links it to Shinjuku Station, Tokyo. The station complex also includes

shopping arcades and a bus terminal.

In 2002, Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi announced the end of new town construction,

although the new towns continue to receive government funding and redevelopment. By the

turn of the 21st Century the context for urban development had dramatically changed. Today,

Japan faces challenges of an ageing and declining population, reductions in revenue for

local government, declining urban population densities (see Figure 9 for typical trends from

1960 to 2000 in selected prefectures) and sprawling outer suburban development that is car

dependent. Residential development has been occurring outside of municipal boundaries

Figure 9 Decline in Population Density in Urbanized Regions of Japan, 1960 to 2000

Working Paper 06:

Case Studies of Mass Rapid Transit (MRT),

Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) and Transit Oriented Development (TOD)

24

Sendai City and Miyagi Prefecture Japanese Leader in TOD Planning?

Throughout Japan the problem of urban sprawl is recognized including the declining

revenue base and increase in costs of government maintenance. Sendai is one example

where development has occurred away from railways and subways (Figure 10). Research

by one of the authors into sustainable urban transport policies in the 10 largest cities of

Japan outside of the Tokyo and Osaka regions noted that the compact city was a common

vision of policymakers yet few specific policies (for example, parking policies) had been

introduced to achieve multi-centric nodes nor to encourage transit oriented development.

Sendai is one of the few cities in Japan that is striving to develop TOD around key

nodes on the public transport network, and positioning itself to be a leader in TOD in Japan

(Miyamoto, Kazuaki pers. comm..) . The Miyagi Prefecture Government has formed a

committee to investigate the issue. Some of its development scenarios are summarised

below in Figure 9 where the text is .from a translation English from the original Japanese.

The current Master Plan for the City of Sendai was authorised in 1999 and this TOD scenario

document aims to shape the direction of its revision. Already, the City Government has

published Creation and Communication Sendai City Urban Vision in January 2007 where

there is are two pages (pp. 30 31) that describe the need for more concentrated city

developments into major sub-centres yet with little reference to TOD.

Figure 10 Residential Development Away from Public Transport in Sendai 1988-95

In recent research (Miyamoto, et al, 2007) the three scenarios in Table 1 were prepared

based on the following three assumptions:

a. Scenario of low population density and urban sprawl (Target 2025): Continuation of the

current trends. This is the case that the least effects of plans and policies for land use will

be observed.

b. Guidelines for planning of urban area scenario (Target 2025): Scenario that abides by the

current master plan. This is the case that almost all effects of existing plans and policies

will be observed.

GREAT-Project

25

c. Consolidated planning of city areas on transportation corridors (Long-term model): Model

case scenario of city envisioned beyond the current planning framework. This is the case

that the most desirable city structure will be established in the context of population

decrease and diminishing city areas. Conditions for infrastructure development of the

first scenario were applied to all the scenarios.

The transportation measures will preserve the maximum accessibility of public

transportation within a TOD city area and between different TOD city areas.

Table 2 Three Scenarios for the Development of Sendai to 2025

Working Paper 06:

Case Studies of Mass Rapid Transit (MRT),

Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) and Transit Oriented Development (TOD)

26

The comparison of the performance of each scenario is important. The key concept is

the public transport 30 minutes sphere for the population from Sendai Station. The residence

population that can arrive at JR Sendai Station using public transport within 30 minutes

increases for both scenarios compared with the present situation. The increase population

remains at about 60,000 with scenario 1, but with scenario 2 increases to about 160,000 -

more than the double - and scenario 3 increases to about 260,000. Access with the scenario

3-related improvement is big; about half of the ten surrounding cities, towns and villages

population can access it from JR Sendai Station within public transport use within 30 minutes.

A place of life, the access characteristics to a city / the local action rose than with scenario 2

and 3 and were able to confirm that public transport use access characteristics rose in

particular again than the existing development trends.

Scenario I, which is characterized by the current trend, has difficulties in achieving the

above four targets and requires radical changes in the development of the city structure.

Scenario III appears to be a better alternative than the other two in accomplishing the urban

transportation targets, but it requires a longer timeframe to achieve a significant reorganization

of the city structure and land use, supported by the development of dependable corridors.

Therefore, it is difficult to achieve these targets in 20 years, but it should be a long-term goal

in the aging and sparsely populated society.

Although Scenario II would achieve improvements in most indices, it would not be at

par with Scenario III; however, it could be considered as a mid-point in achieving the long-

term described in Scenario III, in both land use and transportation. Hence, it seems reasonable

that Scenario II will be realized by 2025: Policies that would guide the integrated city area

while developing urban transportation policies, such as the development of feasible

transportation facilities and soft transportation measures (measures promoting public

transportation use and reducing car traffic).

Notes: The setting of the scenario went for ten cities, towns and villages where a Sennen wide area city planning area was

appointed.

GREAT-Project

27

Moreover, in order to make these measures effective to a certain level, it is necessary

for the local government to undertake promotions to establish a system for collaboration

with local residents in the metropolitan area and private stakeholders. It is also important to

implement these policies in tandem with measures that change travel behavior, such as

Transport Demand Management (TDM) and other measures that vigorously change the

daily travel modes to public transportation.

The Sendai City Hall has also established a Scientific Committee of TOD that met in

December 2007 and is aiming to finalise its work by the end of 2008. The representation is

from Tohoku University (specialist in transport engineering, specialist in urban and regional

planning), Tohoku Private University (specialist in geography) and from Fukushima University

(specialist in Architecture). The current situation at the end of July, 2008 (the committee met

in early August, 2008) is that a detailed analysis of urban trends and an identification of the

problems of implementing TOD have been undertaken. The difficulties are mainly of a political

nature with the TOD sub-centres being allocated to every ward. However, the market cannot

sustain so many centres. There is also a lack of willing cooperation between local government

and Japan Railways (JR). For example, to the south of the Sendai CBD at Atsutonagamachi

the former JR railway sidings have been removed leaving vacant land with potential for TOD

but a nearby shopping centre development has already occurred thereby comprising a TOD

with mixed land uses on former railway land.

Land Re-adjustment Program

Japan has a long and successful history using the land re-adjustment program. In

particular this has been successfully applied to many station revitalisation and redevelopment

schemes (for example, JBIC Study Team, 2008). Its application to Asian cities has been

studied and its principles (see Figure 11) are worthy of examination in the context of land

acquisition in Jakarta around MRT stations.

Figure 11. Principles of Japanese Land Readjustment System

Conclusions

The threat resides within the limitations of todays paradigm to be convincing about the

future.

To recap a few obtainable outcomes required for Sydney that can be empirically shown

to be able to be delivered by Metro:

Working Paper 06:

Case Studies of Mass Rapid Transit (MRT),

Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) and Transit Oriented Development (TOD)

28

Metro lines open up the possibility of new choices in neighbourhood design whereby

transit stations anchor and reflect the communities they serve.

Efficient and reliable Metro Lines shrink cities and their carbon footprints.

Interconnected neighbourhoods at a metropolitan scale widen social inclusion and

opportunity.

In the new global economy, fast and reliable public transport widens the geographical

coverage of spatial labour markets.

Pedestrian-friendly neighbourhoods replete with civic, commercial and cultural amenity,

infused with health and education services, temper the need to travel.

Inspiring change management lead by government, alliances or agents will help deliver a

more sustainable city.

New and revived neighbourhoods can be designed to embrace the highest possible levels

of social equity, livability, ecological sustainability and economic prosperity.

The greater sustainability and social dividend of Metro resides outside the hours of

commuting and is available at no additional community cost.

The design of highly accessible Metro neighbourhoods is perhaps more important

than the design of the metro transport system itself. There are opportunities along the route

for major civic spaces that create new neighbourhood hearts, sources of pride and identity

as well as serving a transit interchange can be created that demonstrate civic commitment,

enhance community pride and encourage local investment.

Understandably, in a paradigm of suburban lifestyles, the Metro and the potential of its

neighbourhoods are poorly understood in Australia because of a shortage of desirable local

precedents.

Direction and Actions

To be worlds best practice in Metro implementation requires a holistic approach to city

building that moves well beyond the logistics of the location of Metro routes and stations.

Two major ingredients to achieving holistic outcomes and securing Pelham 123s hero

reside in the establishment of alliances and a trans-disciplinary approach to implementation.

The establishment of Metro route neighbourhood alliances has been used overseas.

They are cost effective ways of empowering communities, businesses and other stakeholders

to take responsibility for delivering greater patronage, sustainability, social and economic

dividends from Metro implementation.

As potential beneficiaries, they take responsibility for putting in place the important

ingredients of successful Metro neighborhoods such as multi-modal accessibility and

connectivity, enhanced public domains and community facility, activities and opportunity.

This provides the framework for intensification arising less from Government dictate and

more from community demand for access to desirable and sustainable city environments.

Importantly, well-constructed alliances can become the hero promoter and defender of

Metro schemes and thereby significantly reduce political risk to optimising benefits.

Establishing alliances starts with local agendas. A positive way to commence and

maintain the dialogue includes the following actions.

GREAT-Project

29

Put in place local community and business reference groups;

Seek local definition and understanding of each Metro neighborhood;

Undertake accessibility and mobility studies;

Prepare neighbourhood accessibility and public domain improvement plans;

Establishment travel demand behaviour change programs;

Identify and implement targeted local innovations in urban design and transport integration;

Commence a process early that identifies and plans for model Metro neighbourhood/s on

the route.

Establishing a network for local alliances creates more sophisticated route or regional

alliances that can embrace bigger concepts such as economic development through Regional

Enterprises as well as act as Metro scheme champions.

At a technical level, bridging the inevitable gulf between the technical demands of

route and station design and construction, and a positive process of creating desirable Metro

Neighbourhoods requires a trans-disciplinary approach to the problem (see Higginbotham,

et al, 2001; Black, 2007).

Acknowledgements

A number of people have willing given their time to assist the GREAT project and we

thank the following; Ir. Eddi Santosa, Director, MRT Jakarta, Balai Kota DKI Jakarta; Dr

Masafumi Ota, Manager, Project Coordinating Secretariat, Planning and Administration

Division, Railway Headquarters, Tokyu Corporation, Tokyo; Mr Dongkun Oh, Assistant

Manager, Residential Realty Division, Residential (Development) Headquarters, Tokyu

Corporation, Tokyo; Professor Yoshitsugu Hayashi, Dean, Graduate School of Environmental

Management, Nagoya University; Professor Kazuaki Miyamoto, Musashi University of

Technology, Yokohama; Professor Makoto Okumura, Director, CNEAS, Tohoku University,

Sendai, Japan; Dr Hiroshi Mori, Chief Consultant, Social-System Policy Department, Mitsubishi

Research Institute, Inc, Otemachi 2 Chome, Tokyo; Dr Masy Arioka, Kumagai Gumi

Company, Iidabashi, Tokyo; Dr Hiroshi Mr Yoneda Gen, Deputy Director, Division 2 and

Division 1, Development Assistance Department, Japan Bank for International Cooperation,

4-1, Ohtemachi 1-chome, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo; Mr Michihiko Ogawa, Program Officer, Division

2, Indonesia, Japan Bank for International Cooperation, 4-1, Ohtemachi 1-chome, Chiyoda-

ku, Tokyo; Mr John Hart, Multi-modal Transport Manager, NSW Roads and Traffic Authority;

Professor John Renne, University of New Orleans, New Orleans.

References

Black, J. (2007) Innovative Management of Airport Environmental Issues, 2007 International

Conference on Management Sciences and Innovation Theme: for Blue Ocean

Strategy, College of Management, Chang Jung Christian University, April 24

26, 2007, Tainan County, Taiwan, Abstracts, p. 29 (CD ROM).

Cervero, R., et al. (2004). Transit Oriented Development in America: Experiences, Challenges,

and Prospects. National Academy Press: Washington, D.C.

Faber, M. (2005). Transitways: Regional Road-based Public Transport Supporting Urban

Change on Sydneys Growth Frontier. Unpublished Conference paper.

Working Paper 06:

Case Studies of Mass Rapid Transit (MRT),

Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) and Transit Oriented Development (TOD)

30

Hein, C. (2003) Visionary Plans and Planners: Japanese Traditions and Western Influences,

in Nicholas Fiv and Paul Waley (eds) Japanese Capitals in Historical

Perspective, New York: Routledge Curzon, pp. 309-43.

Higginbotham, N., G (eds.) (2001) Health Social Science: A Trans-disciplinary and Complexity

Perspective. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

JBIC Study Team (2008) Study on Railway Stations Revitalization Workshop Material.

Jakarta May 28, 2008.

Japan Bank for International Cooperation 2008 Japan Bank for International Cooperation

Annual Report 2007. Tokyo, Chiyoda-ku Japan Bank for International Cooperation.

http.//www.jbic.go.jp.english

Miyamoto, Kazuaki, Kazushige Hayashi, Nobuhiro Akimoto and Yoshiyuki Tokunaga (2007)

Comprehensive Transportation Plan with a Proposal for City Structure Reform:

Sendai Metropolitan Area Transportation Plan 2005, paper presented at the

World Conference on Transport Research, University of California, Berkeley,

California, July, 2007 (Conference CD-ROM).

Planning Research Centre with Jackson Teece Architects (2007) Transit Oriented

Developments for Busways A Report to the NSW Roads and Traffic Authority.

Sydney, The Planning Research Centre of the University of Sydney, May, 2007.

Sendai City (2007) Creation and Communication Sendai City Urban Vision. Sendai City,

January, 2007.

Sinclair Knight Merz (2000). Liverpool - Parramatta Rapid Bus Transitway Environmental

Impact Assessment. Sinclair Knight Merz for the NSW Roads and Traffic Authority:

St Leonards, NSW.

Suisman, D. (n.d.). The Los Angeles metro rapid system: Designing rapid bus service from

the sidewalk up, mimeo.

Swope, C. (2006). L.A. Banks on Buses. Planning Magazine, American Planning Association,

May 2006, www.planning.org/planning/member/2006may/LAbuses.htm.

accessed on 15 May 2006.

http://www.adb.org/Projects/project.asp?id=40009

ht t p: / / web. worl dbank. org/ ext ernal / proj ects/ mai n?pagePK=64283627&pi PK=

73230&theSitePK= 40941&menuPK=228424&Projectid=P107163

GREAT-Project

31

Working Paper 06:

Case Studies of Mass Rapid Transit (MRT),

Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) and Transit Oriented Development (TOD)

32

The Center for Transportation and Logistics Studies (PUSTRAL)

Universitas Gadjah Mada

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Uganda Road Project Implementation ManualDocument32 pagesUganda Road Project Implementation Manualpeter093100% (1)

- Airport Layout and Airport TerminalDocument94 pagesAirport Layout and Airport TerminalChouaib Ben Boubaker80% (10)

- GIS AccidentsDocument5 pagesGIS Accidentsali110011Pas encore d'évaluation