Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

The Genetic Revolution: Vincent Sarich Allan Wilson Blood Serum Albumin Chimpanzees Gorillas

Transféré par

Sanket PatilTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

The Genetic Revolution: Vincent Sarich Allan Wilson Blood Serum Albumin Chimpanzees Gorillas

Transféré par

Sanket PatilDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

The genetic revolution[edit]

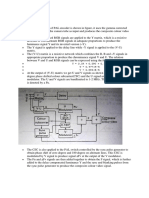

The genetic revolution in studies of human evolution started when Vincent Sarich and Allan

Wilson measured the strength of immunological cross-reactions of blood serum albumin between

pairs of creatures, including humans and African apes (chimpanzees and gorillas).

[20]

The strength of

the reaction could be expressed numerically as an immunological distance, which was in turn

proportional to the number of amino acid differences between homologous proteins in different

species. By constructing a calibration curve of the ID of species' pairs with known divergence times

in the fossil record, the data could be used as a molecular clock to estimate the times of divergence

of pairs with poorer or unknown fossil records.

In their seminal 1967 paper in Science, Sarich and Wilson estimated the divergence time of humans

and apes as four to five million years ago,

[20]

at a time when standard interpretations of the fossil

record gave this divergence as at least 10 to as much as 30 million years. Subsequent fossil

discoveries, notably Lucy, and reinterpretation of older fossil materials, notably Ramapithecus,

showed the younger estimates to be correct and validated the albumin method. Application of

the molecular clock principle revolutionized the study of molecular evolution.

The quest for the earliest hominin[edit]

In the 1990s, several teams of paleoanthropologists were working throughout Africa looking for

evidence of the earliest divergence of the Hominin lineage from the great apes. In 1994, Meave

Leakey discovered Australopithecus anamensis. The find was overshadowed by Tim White's 1995

discovery of Ardipithecus ramidus, which pushed back the fossil record to 4.2 million years ago.

In 2000, Martin Pickford and Brigitte Senut discovered in the Tugen Hills of Kenya a 6-million-year-

old bipedal hominin which they named Orrorin tugenensis. And in 2001, a team led by Michel

Brunet discovered the skull of Sahelanthropus tchadensis which was dated as 7.2 million years ago,

and which Brunet argued was a bipedal, and therefore a hominid.

Human dispersal[edit]

A model of human migration, based from divergence of themitochondrial DNA (which indicates

the matrilineage).

[21]

Timescale (kya) indicated by colours.

A "trellis" (as Wolpoff called it) that emphasizes back-and-forth gene flow among geographic regions.

[22]

Different models for the beginning of the present human species.

See also: Early human migrations, Recent African origin of modern humans and Multiregional

hypothesis

Anthropologists in the 1980s were divided regarding some details of reproductive barriers and

migratory dispersals of the Homo genus. Subsequently, genetics has been used to investigate and

resolve these issues. According to the Sahara pump theory evidence suggests that

genus Homo have migrated out of Africa at least three times (e.g. Homo erectus, Homo

heidelbergensis and Homo sapiens).

The Out-of-Africa model proposed that modern H. sapiens speciated in Africa recently (approx.

200,000 years ago) and the subsequent migration through Eurasia resulted in nearly complete

replacement of otherHomo species. This model has been developed by Chris Stringer and Peter

Andrews.

[23][24]

In contrast, themultiregional hypothesis proposed that Homo genus contained only a

single interconnected population as it does today (not separate species), and that its evolution took

place worldwide continuously over the last couple million years. This model was proposed in 1988

by Milford H. Wolpoff.

[25][26]

Progress in DNA sequencing, specifically mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and then Y-chromosome

DNAadvanced the understanding of human origins.

[27][28][29]

Sequencing mtDNA and Y-DNA sampled

from a wide range of indigenous populations revealed ancestral information relating to both male

and female genetic heritage.

[30]

Aligned in genetic tree differences were interpreted as supportive of

a recent single origin.

[31]

Analyses have shown a greater diversity of DNA patterns throughout Africa,

consistent with the idea that Africa is the ancestral home of mitochondrial Eve and Y-chromosomal

Adam.

[32]

Out of Africa has gained support from research using female mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and the

male Y chromosome. After analysing genealogy trees constructed using 133 types of mtDNA,

researchers concluded that all were descended from a female African progenitor,

dubbed Mitochondrial Eve. Out of Africa is also supported by the fact that mitochondrial genetic

diversity is highest among African populations.

[33]

A broad study of African genetic diversity, headed by Sarah Tishkoff, found the San people had the

greatest genetic diversity among the 113 distinct populations sampled, making them one of 14

"ancestral population clusters". The research also located the origin of modern human migration in

south-western Africa, near the coastal border of Namibia andAngola.

[34]

The fossil evidence was

insufficient for Richard Leakey to resolve this debate.

[35]

Studies of haplogroups in Y-chromosomal

DNA and mitochondrial DNA have largely supported a recent African origin.

[36]

Evidence from

autosomal DNA also predominantly supports a Recent African origin. However evidence

for archaic admixture in modern humans had been suggested by some studies.

[37]

Recent sequencing of Neanderthal

[38]

and Denisovan

[39]

genomes shows that some admixture

occurred. Modern humans outside Africa have 2-4% Neanderthal alleles in their genome, and

some Melanesians have an additional 4-6% of Denisovan alleles. These new results do not

contradict the Out of Africa model, except in its strictest interpretation. After recovery from a genetic

bottleneck that might be due to the Toba supervolcano catastrophe, a fairly small group left Africa

and briefly interbred with Neanderthals, probably in the middle-east or even North Africa before their

departure. Their still predominantly African descendants spread to populate the world. A fraction in

turn interbred with Denisovans, probably in south-east Asia, before populating

Melanesia.

[40]

HLA haplotypes of Neanderthal and Denisova origin have been identified in modern

Eurasian and Oceanian populations.

[14]

There are still differing theories on whether there was a single exodus or several. A multiple

dispersal model involves the Southern Dispersal theory,

[41]

which has gained support in recent years

from genetic, linguistic and archaeological evidence. In this theory, there was a coastal dispersal of

modern humans from the Horn of Africa around 70,000 years ago. This group helped to populate

Southeast Asia and Oceania, explaining the discovery of early human sites in these areas much

earlier than those in the Levant.

[41]

A second wave of humans may have dispersed across the Sinai peninsula into Asia, resulting in the

bulk of human population for Eurasia. This second group possibly possessed a more sophisticated

tool technology and was less dependent on coastal food sources than the original group. Much of

the evidence for the first group's expansion would have been destroyed by the rising sea levels at

the end of each glacial maximum.

[41]

The multiple dispersal model is contradicted by studies

indicating that the populations of Eurasia and the populations of Southeast Asia and Oceania are all

descended from the same mitochondrial DNA lineages, which support a single migration out of

Africa that gave rise to all non-African populations.

[42]

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Dogs: Their Fossil Relatives & Evolutionary HistoryD'EverandDogs: Their Fossil Relatives & Evolutionary HistoryÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (12)

- Dispersal of Modern Homo Sapiens: Known H. Sapiens Migration Routes in The PleistoceneDocument2 pagesDispersal of Modern Homo Sapiens: Known H. Sapiens Migration Routes in The Pleistocenenikita bajpaiPas encore d'évaluation

- Institute of Biology University of The Philippines Diliman, Quezon CityDocument26 pagesInstitute of Biology University of The Philippines Diliman, Quezon CityRaven Fame TupaPas encore d'évaluation

- Human EvolutionDocument9 pagesHuman EvolutionVinod BhaskarPas encore d'évaluation

- Anth1020 RPDocument4 pagesAnth1020 RPapi-245685187Pas encore d'évaluation

- We Are All AfricanDocument5 pagesWe Are All AfricanMaajid BashirPas encore d'évaluation

- Evolution of Modern Humans - StoriesDocument6 pagesEvolution of Modern Humans - StoriesBinodPas encore d'évaluation

- Early Modern Human: Name and TaxonomyDocument29 pagesEarly Modern Human: Name and TaxonomySebastian GhermanPas encore d'évaluation

- Bottlenecks Volcanic WinterDocument29 pagesBottlenecks Volcanic Winterfacb52Pas encore d'évaluation

- Anthropology 1020 Research PaperDocument4 pagesAnthropology 1020 Research Paperapi-253314993Pas encore d'évaluation

- NOTES - EssayDocument5 pagesNOTES - EssayDenisa Cretu100% (1)

- Research PaperDocument6 pagesResearch Paperapi-356015122Pas encore d'évaluation

- AnthropologyresearchpaperDocument5 pagesAnthropologyresearchpaperapi-356008696Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Real EveDocument2 pagesThe Real EveKangMaru_025Pas encore d'évaluation

- Neandertal Demise An Archaeological AnalDocument43 pagesNeandertal Demise An Archaeological AnaltoddsawickiPas encore d'évaluation

- An Indian Ancestry, A Key For Understanding Human Diversity in Europe Kivisild2000Document11 pagesAn Indian Ancestry, A Key For Understanding Human Diversity in Europe Kivisild2000shinkaron88100% (2)

- Case Studies in Anthropology Optional UpscDocument8 pagesCase Studies in Anthropology Optional UpscSaiVenkatPas encore d'évaluation

- O'Shea, Delson2018 - The Origin of UsDocument5 pagesO'Shea, Delson2018 - The Origin of UshioniamPas encore d'évaluation

- EvolutionistDocument347 pagesEvolutionistKatalinPas encore d'évaluation

- Interbreeding Between Archaic and Modern HumanDocument22 pagesInterbreeding Between Archaic and Modern HumanPlanet CscPas encore d'évaluation

- Human EvolutionDocument23 pagesHuman EvolutionArpit Shukla100% (2)

- Match The Terminology With The Definitions.: The Incredible Journey Taken by Our GenesDocument2 pagesMatch The Terminology With The Definitions.: The Incredible Journey Taken by Our GenesazbestosPas encore d'évaluation

- Cioclovina (Romania) : Affinities of An Early Modern EuropeanDocument15 pagesCioclovina (Romania) : Affinities of An Early Modern EuropeanTudor HilaPas encore d'évaluation

- Modern Human OriginsDocument6 pagesModern Human Originsapi-240548615Pas encore d'évaluation

- Regional ContinuityDocument4 pagesRegional Continuityapi-242352239Pas encore d'évaluation

- Biology Investigatory ProjectDocument6 pagesBiology Investigatory ProjectHiromi Minatozaki100% (1)

- 2005 - EswaranDocument18 pages2005 - EswaranyodoidPas encore d'évaluation

- Research PaperDocument5 pagesResearch Paperapi-241126921Pas encore d'évaluation

- How Did Homo Sapiens Evolve?: Genetic and Fossil Evidence Challenges Current Models of Modern Human EvolutionDocument4 pagesHow Did Homo Sapiens Evolve?: Genetic and Fossil Evidence Challenges Current Models of Modern Human EvolutionAldy AnggharaPas encore d'évaluation

- (2022 Article) Chris Stringer - The Development of Ideas About A Recent African OriginDocument14 pages(2022 Article) Chris Stringer - The Development of Ideas About A Recent African OriginhioniamPas encore d'évaluation

- Ancient Genomes From Southern Africa Pushes Modern Human Divergence Beyond 1,260,000 Years AgoDocument23 pagesAncient Genomes From Southern Africa Pushes Modern Human Divergence Beyond 1,260,000 Years AgoMercurio157Pas encore d'évaluation

- Jurnal Arthopoda PDFDocument12 pagesJurnal Arthopoda PDFBenny UmbuPas encore d'évaluation

- About Homo SapiensDocument9 pagesAbout Homo Sapiensearly yearlyPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit 5Document18 pagesUnit 5Yuuka HiềnPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 3: Africa and Human Origins: Sapiens SapiensDocument6 pagesChapter 3: Africa and Human Origins: Sapiens SapiensJane Onyechekoloyi AuduPas encore d'évaluation

- The First PeopleDocument2 pagesThe First PeopleLuana GuerreroPas encore d'évaluation

- Comas, The Genetics of Human MigrationDocument8 pagesComas, The Genetics of Human MigrationElizabeth CamachoPas encore d'évaluation

- Nature 09710Document8 pagesNature 09710oldno7brandPas encore d'évaluation

- Human EvolutionDocument1 pageHuman EvolutionCkrhayzxiel SorianoPas encore d'évaluation

- Ehret, C. Early Humans: Tools, Language, and CultureDocument23 pagesEhret, C. Early Humans: Tools, Language, and CultureHenrique Espada LimaPas encore d'évaluation

- Human EvolutionDocument48 pagesHuman Evolutionstevensteeler083Pas encore d'évaluation

- Homo Sapiens: Human Evolution, The Process by WhichDocument4 pagesHomo Sapiens: Human Evolution, The Process by WhichAndrewPas encore d'évaluation

- Ancient DNA fro-WPS OfficeDocument10 pagesAncient DNA fro-WPS Officeannisa krismadayantiPas encore d'évaluation

- Human EvolutionDocument9 pagesHuman EvolutionAndrew JonesPas encore d'évaluation

- The Origins of Modern HumansDocument3 pagesThe Origins of Modern Humans039QONITA INDAH ARRUSLIPas encore d'évaluation

- In Search of Our PastDocument19 pagesIn Search of Our Pastomprakash2592Pas encore d'évaluation

- Neanderthal and DenisovanDocument2 pagesNeanderthal and Denisovannikita bajpaiPas encore d'évaluation

- Bahasa Inggris To Sec 4Document17 pagesBahasa Inggris To Sec 4Auliya RamdhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Modern Human Origins Research PaperDocument4 pagesModern Human Origins Research Paperapi-295153175Pas encore d'évaluation

- Discuss The Two Theories of Modern Human Origins-EnesoguzDocument5 pagesDiscuss The Two Theories of Modern Human Origins-Enesoguzapi-291653188Pas encore d'évaluation

- Human Evolution: The Southern Route To Asia: Todd R. DisotellDocument4 pagesHuman Evolution: The Southern Route To Asia: Todd R. Disotellapi-198310771Pas encore d'évaluation

- Test 2 Wednesday 28 September 2016 - DAY 3: Study Guide - History (1A, 1B, 1C)Document1 pageTest 2 Wednesday 28 September 2016 - DAY 3: Study Guide - History (1A, 1B, 1C)Batool MirzaPas encore d'évaluation

- 138 Alpha Series Human EvolutionDocument9 pages138 Alpha Series Human Evolutionrofidatul04Pas encore d'évaluation

- Homo Homo Sapiens: Human Evolution Is TheDocument2 pagesHomo Homo Sapiens: Human Evolution Is TheSanket PatilPas encore d'évaluation

- Early Human MigrationsDocument26 pagesEarly Human MigrationsPlanet CscPas encore d'évaluation

- Research Paper Anth 1020Document4 pagesResearch Paper Anth 1020api-340985654Pas encore d'évaluation

- Wolpoff, Wu and Thorne - Modern Homo Sapiens Origins, A General Theory of Hominid Evolution, Involving The Fossil Evidence From East Asia - 84Document73 pagesWolpoff, Wu and Thorne - Modern Homo Sapiens Origins, A General Theory of Hominid Evolution, Involving The Fossil Evidence From East Asia - 84gabrah100% (2)

- Review Article The Use of Racial, Ethnic, and Ancestral Categories in Human Genetics ResearchDocument14 pagesReview Article The Use of Racial, Ethnic, and Ancestral Categories in Human Genetics ResearchBoda Andrea BeátaPas encore d'évaluation

- From Africa To Eurasia - Early DispersalsDocument11 pagesFrom Africa To Eurasia - Early DispersalsPGIndikaPas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment On Numerical - Unit2Document2 pagesAssignment On Numerical - Unit2Sanket Patil0% (1)

- PAL Encoder: Y 0.3R + 0.59G + 0.11B U 0.477 (R-Y) V 0.895 (B-Y)Document3 pagesPAL Encoder: Y 0.3R + 0.59G + 0.11B U 0.477 (R-Y) V 0.895 (B-Y)Sanket Patil100% (1)

- ComparisonsDocument2 pagesComparisonsSanket PatilPas encore d'évaluation

- Travelling Wave Tube: =V (Pitch/2πr)Document7 pagesTravelling Wave Tube: =V (Pitch/2πr)Sanket PatilPas encore d'évaluation

- Image CompressionDocument2 pagesImage CompressionSanket PatilPas encore d'évaluation

- All All 'Football - JPG': %morphological OperationsDocument4 pagesAll All 'Football - JPG': %morphological OperationsSanket PatilPas encore d'évaluation

- The Hit or Miss TransformDocument10 pagesThe Hit or Miss TransformSanket PatilPas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment 11Document8 pagesAssignment 11Sanket PatilPas encore d'évaluation

- CMOS ' Design RulesDocument2 pagesCMOS ' Design RulesSanket PatilPas encore d'évaluation

- Functions of Image PlanesDocument5 pagesFunctions of Image PlanesSanket PatilPas encore d'évaluation

- Jin DynastyDocument5 pagesJin DynastySanket PatilPas encore d'évaluation

- TCP UDP Acronym For Connection Function: InternetDocument3 pagesTCP UDP Acronym For Connection Function: InternetSanket PatilPas encore d'évaluation

- Experiment No 1 PDFDocument17 pagesExperiment No 1 PDFSanket PatilPas encore d'évaluation

- Input Distribution FormatDocument14 pagesInput Distribution FormatSanket PatilPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit 5: Data Communication & Physical LayerDocument98 pagesUnit 5: Data Communication & Physical LayerSanket PatilPas encore d'évaluation

- Northern China Sinicised: Moukes Formed A Meng-An (Battalion)Document2 pagesNorthern China Sinicised: Moukes Formed A Meng-An (Battalion)Sanket PatilPas encore d'évaluation

- Jin Dynasty 3Document2 pagesJin Dynasty 3Sanket PatilPas encore d'évaluation

- Protection Circuits: by Murtuza Bohari Sanket Patil Ankit KhandekarDocument21 pagesProtection Circuits: by Murtuza Bohari Sanket Patil Ankit KhandekarSanket PatilPas encore d'évaluation

- Metallogeny: The Rationale Behind Space (WHERE?) - Time (WHEN?) : Distribution of Ore DepositsDocument8 pagesMetallogeny: The Rationale Behind Space (WHERE?) - Time (WHEN?) : Distribution of Ore DepositsdeepuvibhalovePas encore d'évaluation

- Human EvolutionDocument10 pagesHuman Evolution11 E Harsh dagarPas encore d'évaluation

- The Sixth Extinction: Niles EldredgeDocument8 pagesThe Sixth Extinction: Niles EldredgevanessaPas encore d'évaluation

- Walton On The Naze 2012-13Document46 pagesWalton On The Naze 2012-13Jack LinsteadPas encore d'évaluation

- StratumDocument42 pagesStratumAchmad WinarkoPas encore d'évaluation

- P-27 Geological Time ScaleDocument2 pagesP-27 Geological Time ScaleFelix Joshua.B 10 BPas encore d'évaluation

- Places To Visit WalesDocument10 pagesPlaces To Visit WalesAlex PinballPas encore d'évaluation

- Họ, tên thí sinh:.......................................................................... Số báo danh:..............................................................................Document3 pagesHọ, tên thí sinh:.......................................................................... Số báo danh:..............................................................................nguyen Thanh PhuongPas encore d'évaluation

- Two Cretaceous Echinoids From PeruDocument4 pagesTwo Cretaceous Echinoids From PeruEduardo Alejandro Hidalgo NichoPas encore d'évaluation

- 2) Petroleum GeologyDocument55 pages2) Petroleum GeologyRainaClarisaLahliantiPas encore d'évaluation

- Kekura Project ProductionDocument10 pagesKekura Project ProductionBeatriceWasongaPas encore d'évaluation

- Coastal Dispersal: of Pleistocene HomoDocument14 pagesCoastal Dispersal: of Pleistocene HomoAnonymous wWRphADWzPas encore d'évaluation

- EGI Oceans - South Atlantic: in ProgressDocument9 pagesEGI Oceans - South Atlantic: in Progressdino_birds6113Pas encore d'évaluation

- Mollusks & EchinodermDocument18 pagesMollusks & EchinodermRoselle GuevaraPas encore d'évaluation

- FishesDocument28 pagesFishesMilla ZahiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Mini Diagnostic Test Written v21Document15 pagesMini Diagnostic Test Written v21Riska MaharaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Revised Stratigraphy of Indus Basin (Pakistan) : Sea Level ChangesDocument5 pagesRevised Stratigraphy of Indus Basin (Pakistan) : Sea Level ChangesSidra ShahPas encore d'évaluation

- Borderlands Vol XLIX No 3, Third Quarter 1993Document52 pagesBorderlands Vol XLIX No 3, Third Quarter 1993Thomas Joseph Brown100% (2)

- Cape Basin South AfricaDocument15 pagesCape Basin South AfricaAmy Lauren SassPas encore d'évaluation

- STPDocument2 pagesSTPAZERPas encore d'évaluation

- GEOL 1122K WEEK 3 LAB Hadean Eon Plate TectonicsDocument3 pagesGEOL 1122K WEEK 3 LAB Hadean Eon Plate Tectonicsmathman166Pas encore d'évaluation

- COE RKY MTN Disposal Well Report PDFDocument216 pagesCOE RKY MTN Disposal Well Report PDFellsworsPas encore d'évaluation

- Evolution of Paleogene PeriodDocument8 pagesEvolution of Paleogene PeriodHisyam Azhar AziziPas encore d'évaluation

- Hominid SpeciesDocument8 pagesHominid Speciesrey_fremyPas encore d'évaluation

- Human Evolution: Mr. H. JonesDocument23 pagesHuman Evolution: Mr. H. Jonessccscience100% (1)

- Creature IDs - Official ARK Survival Evolved WikiDocument1 pageCreature IDs - Official ARK Survival Evolved WikiJust A harmless PotatoPas encore d'évaluation

- Geological Time Scale and TimelineDocument18 pagesGeological Time Scale and TimelineDarren RepuyanPas encore d'évaluation

- Le Haut-Atlas Central (Maroc) - Stratigraphie Et Paléontologie Du Lias Supérieur Et Du Dogger Inférieur. Dynamique Du Bassin Et Des PeuplementsDocument243 pagesLe Haut-Atlas Central (Maroc) - Stratigraphie Et Paléontologie Du Lias Supérieur Et Du Dogger Inférieur. Dynamique Du Bassin Et Des Peuplementslatifa bellaPas encore d'évaluation

- Niperbdm-0225 (California Oil) PDFDocument150 pagesNiperbdm-0225 (California Oil) PDFjoescribd55Pas encore d'évaluation

- Geology IN - Safety in The Field and General Guidance For Geological Fieldwork PDFDocument3 pagesGeology IN - Safety in The Field and General Guidance For Geological Fieldwork PDFpranowo_ibnuPas encore d'évaluation

- 10% Human: How Your Body's Microbes Hold the Key to Health and HappinessD'Everand10% Human: How Your Body's Microbes Hold the Key to Health and HappinessÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (33)

- Masterminds: Genius, DNA, and the Quest to Rewrite LifeD'EverandMasterminds: Genius, DNA, and the Quest to Rewrite LifePas encore d'évaluation

- When the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisD'EverandWhen the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityD'EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (6)

- Return of the God Hypothesis: Three Scientific Discoveries That Reveal the Mind Behind the UniverseD'EverandReturn of the God Hypothesis: Three Scientific Discoveries That Reveal the Mind Behind the UniverseÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (52)

- Gut: the new and revised Sunday Times bestsellerD'EverandGut: the new and revised Sunday Times bestsellerÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (393)

- All That Remains: A Renowned Forensic Scientist on Death, Mortality, and Solving CrimesD'EverandAll That Remains: A Renowned Forensic Scientist on Death, Mortality, and Solving CrimesÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (397)

- The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs: A New History of a Lost WorldD'EverandThe Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs: A New History of a Lost WorldÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (597)

- Tales from Both Sides of the Brain: A Life in NeuroscienceD'EverandTales from Both Sides of the Brain: A Life in NeuroscienceÉvaluation : 3 sur 5 étoiles3/5 (18)

- Seven and a Half Lessons About the BrainD'EverandSeven and a Half Lessons About the BrainÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (111)

- A Brief History of Intelligence: Evolution, AI, and the Five Breakthroughs That Made Our BrainsD'EverandA Brief History of Intelligence: Evolution, AI, and the Five Breakthroughs That Made Our BrainsÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (6)

- Moral Tribes: Emotion, Reason, and the Gap Between Us and ThemD'EverandMoral Tribes: Emotion, Reason, and the Gap Between Us and ThemÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (116)

- The Molecule of More: How a Single Chemical in Your Brain Drives Love, Sex, and Creativity--and Will Determine the Fate of the Human RaceD'EverandThe Molecule of More: How a Single Chemical in Your Brain Drives Love, Sex, and Creativity--and Will Determine the Fate of the Human RaceÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (517)

- Who's in Charge?: Free Will and the Science of the BrainD'EverandWho's in Charge?: Free Will and the Science of the BrainÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (65)

- The Other Side of Normal: How Biology Is Providing the Clues to Unlock the Secrets of Normal and Abnormal BehaviorD'EverandThe Other Side of Normal: How Biology Is Providing the Clues to Unlock the Secrets of Normal and Abnormal BehaviorPas encore d'évaluation

- Buddha's Brain: The Practical Neuroscience of Happiness, Love & WisdomD'EverandBuddha's Brain: The Practical Neuroscience of Happiness, Love & WisdomÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (216)

- Undeniable: How Biology Confirms Our Intuition That Life Is DesignedD'EverandUndeniable: How Biology Confirms Our Intuition That Life Is DesignedÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (11)

- Remnants of Ancient Life: The New Science of Old FossilsD'EverandRemnants of Ancient Life: The New Science of Old FossilsÉvaluation : 3 sur 5 étoiles3/5 (3)

- Good Without God: What a Billion Nonreligious People Do BelieveD'EverandGood Without God: What a Billion Nonreligious People Do BelieveÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (66)

- The Ancestor's Tale: A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of EvolutionD'EverandThe Ancestor's Tale: A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of EvolutionÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (812)

- A Series of Fortunate Events: Chance and the Making of the Planet, Life, and YouD'EverandA Series of Fortunate Events: Chance and the Making of the Planet, Life, and YouÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (62)

- Darwin's Doubt: The Explosive Origin of Animal Life and the Case for Intelligent DesignD'EverandDarwin's Doubt: The Explosive Origin of Animal Life and the Case for Intelligent DesignÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (19)

- Human: The Science Behind What Makes Your Brain UniqueD'EverandHuman: The Science Behind What Makes Your Brain UniqueÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (38)

- Change Your Brain, Change Your Life (Before 25): Change Your Developing Mind for Real-World SuccessD'EverandChange Your Brain, Change Your Life (Before 25): Change Your Developing Mind for Real-World SuccessÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (18)

- Darwin's Doubt: The Explosive Origin of Animal Life and the Case for Intelligent DesignD'EverandDarwin's Doubt: The Explosive Origin of Animal Life and the Case for Intelligent DesignÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (39)