Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Sculpture 2010 01-02

Transféré par

paulstefan2002Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Sculpture 2010 01-02

Transféré par

paulstefan2002Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

sculpture

January/February 2010

Vol. 29 No. 1

A publication of the

International Sculpture Center

www.sculpture.org

Anish Kapoor

Kader Attia

Ann Hamilton

Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out Search Issue | Next Page For navigation instructions please click here

Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out Search Issue | Next Page For navigation instructions please click here

s

c

u

l

p

t

u

r

e

J

a

n

u

a

r

y

/

F

e

b

r

u

a

r

y

2

0

1

0

V

o

l

.

2

9

N

o

.

1

A

p

u

b

l

i

c

a

t

i

o

n

o

f

t

h

e

I

n

t

e

r

n

a

t

i

o

n

a

l

S

c

u

l

p

t

u

r

e

C

e

n

t

e

r

________________________

_______________________

Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

sculpture

B

A

M S a

G E

F

Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

sculpture

B

A

M S a

G E

F

_______________

Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

sculpture

B

A

M S a

G E

F

Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

sculpture

B

A

M S a

G E

F

___________

____________

Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

sculpture

B

A

M S a

G E

F

Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

sculpture

B

A

M S a

G E

F

_____________________________________

Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

sculpture

B

A

M S a

G E

F

Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

sculpture

B

A

M S a

G E

F

Strategic planning: with the exception of donor pyramid, these

two words may be fraught with more anxiety and optimism than nearly

any others in the minds of nonprofit boards and staffs. Strategic plan-

ning is undertaken by most nonprofit organizations every three to five

years, and the ISC is no different. The board and staff of the ISC are

excited to undertake the process, and we have begun our work with

the assistance of a wonderful consultant. Participation in interviews,

conference calls, and meetings has been active and enthusiastic.

The positive attitude and momentum is due in large part to the recent

stability of the ISC under Johannah Hutchisons leadership. Johannah

and the ISCs dedicated and capable staff have made it possible for the

ISC board to enjoy the prospect of looking into the future and envision-

ing, along with staff, readers, and members, what the ISC might look

like in the years to comelong after we have completed our board

terms.

It is, of course, too early to tell what will come of this process, what

decisions will be made, and what will change over the coming years,

but I can share a small sample of the topics that have engaged us in

deep discussion.

Again, we are considering the I in our name. What does it mean,

and what will it mean in the future, for the ISC to be international? Is

the ISC a U.S. organization with global relationships, or is it a global

organization merely based in the U.S.? Is our international credential

to be measured by the language of Sculpture? The content of Sculpture?

The language and content of our Web site? The location of our confer-

ences? Or all of the above?

Similarly, we have begun lengthy discussions about what we do

and should doto serve our membership. While Sculpture and the

Web site bind ISC members together, and conferences bring our mem-

bers together, among other things, we are exploring ways to make

better use of new mediathe Internet, our Web site, blogs, Facebook,

Twitter, and other, developing technologiesto connect with the

sculpture community and allow our members to connect with each

other and the information, services, and opportunities important to

them. We are also exploring just what our many different constituen-

ciesemerging artists, struggling artists, successful artists, collectors,

art lovers, art administrators, and othersfind valuable.

Of course, no strategic planning discussion would be complete with-

out a splash of economic cold water, so we will pepper these discus-

sions with how to pay for the grandiose ideas that we dream up. Rest

assured, however, that long-term financial stability is, and will remain,

a top priority for the ISC staff and board.

Whether this process is completed next month or next year, I am

confident that the ISC board and staff are engaging in this exercise

deliberately and with care; whatever the outcome, the organization,

and you, its supporters, will be better served in the years to come. I

look forward to telling you more about our progress in the coming

months.

Josh Kanter

Chairman, ISC Board of Directors

From the Chairman

4 Sculpture 29.1

ISC Board of Directors

Chairman: Josh Kanter, Salt Lake City, UT

Chakaia Booker, New York, NY

Robert Edwards, Naples, FL

Bill FitzGibbons, San Antonio, TX

David Handley, Australia

Richard Heinrich, New York, NY

Paul Hubbard, Philadelphia, PA

Ree Kaneko, Omaha, NE

Gertrud Kohler-Aeschlimann, Switzerland

Marc LeBaron, Lincoln, NE

Patricia Meadows, Dallas, TX

George W. Neubert, Brownville, NE

Albert Paley, Rochester, NY

Henry Richardson, New York, NY

Russ RuBert, Springfield, MO

Walter Schatz, Nashville, TN

Sebastin, Mexico

STRETCH, Kansas City, MO

Steinunn Thorarinsdottir, Iceland

Boaz Vaadia, New York, NY

Chairmen Emeriti: Robert Duncan, Lincoln, NE

John Henry, Chattanooga, TN

Peter Hobart, Italy

Robert Vogele, Hinsdale, IL

Founder: Elden Tefft, Lawrence, KS

Lifetime Achievement

in Contemporary

Sculpture Recipients

Magdalena Abakanowicz

Fletcher Benton

Louise Bourgeois

Anthony Caro

Elizabeth Catlett

John Chamberlain

Eduardo Chillida

Christo & Jeanne-Claude

Mark di Suvero

Richard Hunt

William King

Manuel Neri

Claes Oldenburg & Coosje van Bruggen

Nam June Paik

Arnaldo Pomodoro

Gio Pomodoro

Robert Rauschenberg

George Rickey

George Segal

Kenneth Snelson

Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

sculpture

B

A

M S a

G E

F

Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

sculpture

B

A

M S a

G E

F

Departments

12 News

14 Itinerary

20 Commissions

80 ISC News

Reviews

69 Helsinki: Aaron Heino

70 Ridgefield, Connecticut: Edward Tufte

71 Boston: Beth Galston

72 Holyoke, Massachusetts: David Poppie

and Roger Sayre

72 New York: Jessica Stockholder

73 New York: Julianne Swartz

74 Cleveland: Jake Beckman

74 Lancaster, Pennsylvania: Deborah Sigel

75 London: Rebecca Warren

76 Barcelona: Tere Recarens

76 Tokyo: Ryoji Ikeda

77 Dispatch: Shanghai

On the Cover: Anish Kapoor, Hive, 2009.

Cor-ten steel, 5.6 x 10.07 x 7.55 meters.

Photograph: Dave Morgan, Courtesy the

artist, Lisson Gallery, London, and Gladstone

Gallery, New York.

Features

22 Anish Kapoor: Transcending the Object by Ina Cole

26 Anish Kapoor at the Guggenheim: The Dimensions of Memory by Jan Garden Castro

28 The Space In Between: A Conversation with Kader Attia by Rebecca Dimling Cochran

36 Extreme Precision: A Conversation with Margaret Evangeline by D. Dominick Lombardi

40 Acts of Finding: A Conversation with Ann Hamilton by Jan Garden Castro

48 Rebecca Ripple: Orgy in the Sky by Jessica Rath

50 John Atkin: Sculpture that Declares the Space Around It by Robert C. Morgan

54 The Beauty of Thinking: A Conversation with Giuseppe Panza by Sarah Tanguy

28

sculpture

January/February 2010

Vol. 29 No.1

A publication of the

International Sculpture Center

Sculpture January/February 2010 5

40

71

48

36

Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

sculpture

B

A

M S a

G E

F

Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

sculpture

B

A

M S a

G E

F

6 Sculpture 29.1

S CUL PT URE MAGAZ I NE

Editor Glenn Harper

Managing Editor Twylene Moyer

Editorial Assistants Elizabeth Lynch, Deborah Clarke

Design Eileen Schramm visual communication

Advertising Sales Manager Brenden OHanlon

Contributing Editors Maria Carolina Baulo (Buenos Aires), Roger Boyce (Christchurch), Susan Canning

(New York), Marty Carlock (Boston), Jan Garden Castro (New York), Collette Chattopadhyay (Los Angeles),

Ina Cole (London), Ana Finel Honigman (Berlin), John K. Grande (Montreal), Kay Itoi (Tokyo), Matthew

Kangas (Seattle), Zoe Kosmidou (Athens), Angela Levine (Tel Aviv), Brian McAvera (Belfast), Robert C.

Morgan (New York), Robert Preece (Rotterdam), Brooke Kamin Rapaport (New York), Ken Scarlett

(Melbourne), Peter Selz (Berkeley), Sarah Tanguy (Washington), Laura Tansini (Rome)

Advertising information E-mail <advertising@sculpture.org>

Each issue of Sculpture is indexed in The Art Index and the Bibliography of the History of Art (BHA).

isc

Major Donors ($50,000+)

Fletcher Benton

Rob Fisher

John Henry

Richard Hunt

Johnson Art and Education

Foundation

J. Seward Johnson, Jr.

Robert Mangold

Fred & Lena Meijer

I.A. OShaughnessy Foundation

Arnaldo Pomodoro

Russ RuBert

Jon & Mary Shirley Foundation

James Surls

Bernar Venet

Directors Circle ($5,0009,999)

Chairmans Circle ($10,00049,999)

Sydney & Walda Besthoff

Otto M. Budig Family

Foundation

Lisa Colburn

Bob & Terry Edwards

Carol Feuerman

Bill FitzGibbons

Linda Fleming

Gagosian Gallery

The James J. and Joan A.

Gardner Foundation

Michael D. Hall

David Handley

Peter C. Hobart

Joyce & Seward Johnson

Foundation

Mary Ann Keeler

Cynthia Madden Leitner/

Museum of Outdoor Arts

Susan Lloyd

Marlene & William

Louchheim

Patricia Meadows

Merchandise Mart

Properties

Peter Moore

Ralph S. OConnor

Mary OShaughnessy

Frances & Albert Paley

Barry Parker

Patricia Renick

Henry Richardson

Melody Sawyer Richardson

Riva Yares Gallery

Wendy Ross

Walter Schatz

Sculpture Community/

Sculpture.net

Sebastin

Katherine and

Kenneth Snelson

Duane Stranahan, Jr.

Takahisa Suzuki

Steinunn Thorarinsdottir

Laura Thorne

Boaz Vaadia

Robert E. Vogele

Harry T. Wilks

Isaac Witkin

STRETCH

Magdalena Abakanowicz

John Adduci

Atlantic Foundation

Bill Barrett

Blue Star Contemporary

Art Center

Debra Cafaro & Terrance

Livingston

William Carlson

Sir Anthony Caro

Dale Chihuly

Erik & Michele Christiansen

Citigroup

Clinton Family Fund

Woods Davy

Stephen De Staebler

Karen & Robert Duncan

Lin Emery

Virginio Ferrari

Doris & Donald Fisher

Gene Flores

Viola Frey

Neil Goodman

Michael Gutzwiller

Richard Heinrich

John Hock

Stephen Hokanson

Jon Isherwood

Joyce and Seward Johnson

Foundation

Jun & Ree Kaneko

Joshua S. Kanter

Kanter Family Foundation

Keeler Foundation

William King

Gertrud & Heinz Kohler-

Aeschlimann

Anne Kohs Associates

Koret Foundation

Marc LeBaron

Toby D. Lewis

Philanthropic Fund

Lincoln Industries

Marlborough Gallery

Denise Milan

David Nash

National Endowment

for the Arts

Alissa Neglia

Manuel Neri

Tom Otterness

Joel Perlman

Pat Renick Gift Fund

Estate of John A. Renna

Salt Lake Art Center

Lincoln Schatz

June & Paul Schorr, III

Judith Shea

Dr. and Mrs. Robert

Slotkin

Kiki Smith

Mark di Suvero

Nadine Witkin, Estate of

Isaac Witkin

Address all editorial correspondence to:

Sculpture

1633 Connecticut Avenue NW, 4th Floor

Washington, DC 20009

Phone: 202.234.0555, fax 202.234.2663

E-mail: gharper@sculpture.org

Sculpture On-Line on the International

Sculpture Center Web site:

www.sculpture.org

ISC Headquarters

19 Fairgrounds Road, Suite B

Hamilton, New Jersey 08619

Phone: 609.689.1051, fax 609.689.1061

E-mail: isc@sculpture.org

This issue is supported in part by a grant

from the National Endowment for the Arts.

I NT E RNAT I ONAL SCUL PT URE CE NT E R CONT E MPORARY SCUL PT URE CI RCL E

The International Sculpture Center is a 501(c)3 nonprofit organization

that provides programming and services supported by contributions, grants,

sponsorships, and memberships.

The ISC Board of Directors gratefully acknowledges the generosity of our members

and donors in our Contemporary Sculpture Circle: those who have contributed

$350 and above.

I NT E RNAT I ONAL S CUL PT URE CE NT E R

Executive Director Johannah Hutchison

Conference and Events Manager Dawn Molignano

Office Manager Denise Jester

Membership Coordinator Lauren Hallden-Abberton

Membership Associate Emily Fest

Web and Portfolio Manager Frank Del Valle

Conferences and Events Associate Valerie Friedman

Executive Assistant Kara Kaczmarzyk

Administrative Associate Eva Calder Powel

Patrons Circle ($2,5004,999)

Henry Buhl

Elizabeth Catlett

Chateau Ste. Michelle Winery

John Cleveland

Ric Collier

Federated Department

Stores Foundation

Francis Ford Coppola Presents

Frederik Meijer Gardens &

Sculpture Park

Ghirardelli Chocolates

Grounds for Sculpture

Agnes Gund & Daniel Shapiro

Mary Kuechenmeister

Nanci Lanni

McFadden Winery

Museum of Glass

Salt Lake Art Center

Edward Tufte

Geraldine Warner

Marsha & Robin Williams

____________

_________

______________

Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

sculpture

B

A

M S a

G E

F

Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

sculpture

B

A

M S a

G E

F

Sculpture January/February 2010 7

About the ISC

The International Sculpture Center, a member-supported, nonprofit organization

founded in 1960, advances the creation and understanding of sculpture and its

unique, vital contribution to society. The ISC seeks to expand public understanding

and appreciation of sculpture internationally, demonstrate the power of sculpture

to educate, effect social change, engage artists and arts professionals in a

dialogue to advance the art form, and promote a supportive environment for

sculpture and sculptors. Members include sculptors, collectors, patrons, educa-

tors, and museum professionalsanyone with an interest in and commitment

to the field of sculpture.

Membership

ISC membership includes subscriptions to Sculpture and Insider; access to

International Sculpture Conferences; free registration in Portfolio, the ISCs

on-line sculpture registry; and discounts on publications, supplies, and services.

International Sculpture Conferences

The ISCs International Sculpture Conferences gather sculpture enthusiasts

from all over the world to network and dialogue about technical, aesthetic,

and professional issues.

Sculpture Magazine

Published 10 times per year, Sculpture is dedicated to all forms of contemporary

sculpture. The members edition includes the Insider newsletter, which contains

timely information on professional opportunities for sculptors, as well as a list

of recent public art commissions and announcements of members accomplish-

ments.

www.sculpture.org

The ISCs award-winning Web site <www.sculpture.org> is the most comprehensive

resource for information on sculpture. It features Portfolio, an on-line slide

registry and referral system providing detailed information about artists and their

work to buyers and exhibitors; the Sculpture Parks and Gardens Directory, with

listings of over 250 outdoor sculpture destinations; Opportunities, a membership

service with commissions, jobs, and other professional listings; plus the ISC

newsletter and extensive information about the world of sculpture.

Education Programs and Special Events

ISC programs include the Outstanding Sculpture Educator Award, the Outstanding

Student Achievement in Contemporary Sculpture Awards, and the Lifetime

Achievement Award in Contemporary Sculpture and gala. Other special events

include opportunities for viewing art and for meeting colleagues in the field.

/c| .), |c : C .o:o :o||o|e (|| o33),.3\; | o||||eo mcn|||,, e\:e| |e||oc|, cno /oo|, |, ||e |n|e|nc||cnc| :o||o|e ten|e| |o||c||c| c|||:e :o,, tcnne:||:o| /.e |H, !|| ||cc|, Hc||n|cn, |t

.ooo) |t |em|e||| cno o|:||||cn c|||:e :) |c|||cono |o, o||e 3, |cm|||cn, || o3o:), |/ e| oo)o3):o,: |c\ oo)o3):oo: |mc|| |:_:o||o|ec| /nnoc| mem|e||| ooe c|e | ,:oo,

o|:||||cn cn|,, | ,,, (|c| o|:||||cn c| mem|e||| co||oe ||e |, tcncoc, cno |e\|:c coo | ,.o, |n:|ooe c||mc|| oe||.e|,; |e|m||cn | |eo||eo |c| cn, |e|coo:||cn :o||o|e | nc| |ecn|

||e |c| onc||:||eo mc|e||c| ||ece eno cn /| u||| mc|e||c| |eo|||n |e|o|n 0|n|cn e\|eeo cno .c||o||, c| |n|c|mc||cn |e|e|n c|e ||e |ecn||||||, c| ||e co||c|, nc| ||e |t /o.e||||n |n :o||o|e

| nc| cn |no|:c||cn c| enoc|emen| |, ||e |t, cno ||e |t o|:|c|m ||c|||||, |c| cn, :|c|m mcoe |, co.e|||e| cno |c| |mce |e|coo:eo |, co.e|||e| |e||co|:c| c|ce c|o c| Hc||n|cn, |t, cno coo|

||cnc| mc|||n c|||:e |c|mc|e| eno :|cne c| coo|e |c |n|e|nc||cnc| :o||o|e ten|e|, :) |c|||cono |o, o||e 3, |cm|||cn, || o3o:), |/ | neu|cno o|||||o||cn |, t|6, |n:, .,o H ,,||

||ee|, |eu 'c||, |' :oo:), |/ e| 3oo!,,!3oo |c\ 3,3o,,,.,,

Ruth AbernethyLinda Ackley-EakerAcklie Charitable FoundationMine

AkinElizabeth AraliaMichelle ArmitagePorter ArneillUluhan Atac

Michael AurbachJacqueline AvantHelena Bacardi-KielyMaryAnn Baker

Jon Barlow-HudsonBrooke BarrieJerry Ross BarrishBruce Beasley

Edward BenaventeJoseph BeneveniaPatricia Bengtson JonesHelen

BensoConstance BergforsRoger BerryCharles BienvenuCindy

BillingsleyMartin BlankRebecca & Robert BlattbergRita BlittSandra

BloodworthChristian BoltRudolf BoneKurtis BomarGilbert V. Boro

Antonia BostromJames Bud BottomsLouise BourgeoisMichael Bray

J.Clayton BrightCurt BrillJudith BritainSteven S. BrownCharles

BrummellGil BruvelHal BucknerH. Edward BurkeMaureen Burns-

BowieKeith BushEvan CampbellJohn CarlsonPaulette H. Carr

Christopher CarterKati CasidaMary Ann Ellis CasselDavid CaudillJohn

ChallengerGary ChristophersonAsherah CinnamonJohn Clement

Jonathan ClowesMarco CochraneAustin CollinsLin CookRon Cooper

Wlodzimierz CzupinkaSukhdev DailArianne DarJohn B. Davidson

Martin DaweArabella DeckerG.S. DemirokChristine DesireePatrick

DiamondAlbert DicruttaloPeter DiepenbrockAnthony DiFrancesco

Karen DimitLaury DizengremelKatherine DonnellyDorit DornierJim

DoubledayPhilip S. DrillKathryn D. DuncanThomas J. DwyerWard

ElickerElaine EllisHelen EscobedoJohn EvansJanet EvelandPhilip

John EvettZhang FengHelaman FergusonJosephine FergusonHeather

FerrellTalley FisherTrue FisherDustine FolwarcznyBasil C. FrankMary

Annella FrankGayle & Margaret FranzenJames GallucciDenise & Gary

GardnerRonald GarriguesScott GentryShohini GhoshJohn Gill

Michael GodekMasha GoldsteinThomas GottslebenTristan Govignon

Todd GrahamGabriele Poehlmann GrundigRose Ann Grundman

Barbara GrygutisSimon GudgeonNohra HaimeCalvin HallWataru

HamasakaBob HaozousPortia HarcusJacob J. HarmelingSusan

HarrisonChristie HefnerMichael HelbingDaniel A. HendersonTom

HendersonSally HeplerDavid B. HickmanJoyce HilliouHenry L. Hillman

Anthony HirschelAri HirschmanDave HoffmanDar HornRuth Horwich

Bernard HoseyJill HotchkissJack Howard-PotterBrad HowePaul

HubbardGordon HuetherRobert HuffDavid A. HulsebergYoshitada

IharaEve IngallsKevin JefferiesRoy Soren JespersenJulia JitkoffKirk K.

JohnsonJohanna JordanYvette Kaiser SmithWolfram KaltKent Karlsson

Terrence KarpowiczRay KatzMary Ann KeelerColin KerriganNancy

KienholzSilya KieseGloria KischStephen KishelBernard Klevickas

Karley KlopfensteinEsmoreit KoetsierJeffrey KraftTodji KurtzmanLynn

E. La CountJennifer LaemleinDale LamphereEllen LanyonKarl Lautman

Henry LautzWon LeeMichael Le GrandWendy LehmanDennis Leri

Levin & Schreder, Ltd.Evan LewisJohn R. LightKen LightRobert Lindsay

Robert LonghurstSharon LoperCharles LovingJeff LoweNoriaki Maeda

Steve MaloneyMasha Marjanovich-RussellLenville MaxwellJeniffer

McCandlessJoseph McDonnellJane Allen McKinneyDarcy MeekerRon

MehlmanJames MeyerCreighton MichaelGina MichaelsRuth Aizuss

Migdal-BrownLowell MillerJB. & Nana MillikenBrian Monaghan

Norman MooneyAiko MoriokaBrad MortonKeld MoseholmSerge

MozhnevskyW.W. MuellerAnna MurchMorley MyersArnold Nadler

Marina NashNathan Manilow Sculpture ParkIsobel NealStuart Neilsen

John & Anne NelsonMiriam (Mimi) NelsonGeorge NeubertJohn Nicolai

Eleanor NickelJames NickelBrenda NoelDonald NoonJoseph OConnell

Thomas OHaraMichelle OMichaelJames ONealMica OnonPeter

OsborneScott PalsceGertrud ParkerJames T. ParkerRomona Payne

Vernon PeasenellCarol PeligianBeverly PepperRobert PerlessAnne &

Doug PetersonDirk PetersonAngela Ping-OngDaniel PostellonJonathan

QuickMichael QuinteroMadeline Murphy RabbMorton Rachofsky

Marcia RaffVicky RandallKate RaudenbushAdam ReederJeannette

ReinWellington ReiterEllie RileyKevin RobbCarl H. RohmanSalvatore

RomanoAnn RorimerHarvey SadowJames B. SaguiNathan Sawaya

Tom ScarffMarilyn SchanzeMark SchcachterPeter SchifrinAndy

ScottJoseph H. SeipelJerry ShoreDebra SilverJerry SimmsWilliam

SimpsonJames & Nana SmithSusan Smith-TreesStan SmoklerSam

SpiczkaJohn StallingsEric SteinLinda SteinEric StephensonMichael

SternsJohn StewartPasha StinsonElizabeth Strong-CuevasTash

TaskaleAnn TaulbeeCordell TaylorTimothy TaylorAna ThielStephen

TironeCliff TisdellRein TriefeldtWilliam TuckerThomas TuttleLeonidas

TzavarasEdward UhlirJosiah UpdegraffHans Van de BovenkampVasko

VassilevMartine VaugelAles VeselyJill VineyJames WakeLeonard

WalkerMartha WalkerBlake WardMark WarwickRichard WattsDavid

WeinbergGeorgia WellesPhilip WicklanderRaymond Wicklander

Adam L. WiedmannJohn WiederspanMadeline WienerStuart

WilliamsonW.K. Kellogg FoundationJean WolffDr. Barnaby WrightEfat

YahyaogluCigdem YapanarRiva YaresLarry YoungHisham Youssef

Steve ZaluskiGavin Zeigler

Friends Circle ($1,0002,499)

Bishop & Mrs. Claude

Alexander

Neil Bardack

Verina Baxter

Joseph Becherer

Tom Bollinger & Kim

Nikolaev

Chakaia Booker

Paige Bradley

Sylvia Brown

Elizabeth Burstein

Chihuly Studio

Paula Cooper Gallery

Cornish College of the Arts

James Cottrell

Les & Ginger Crane

Charles Cross

Rick & Dana Davis

Richard & Valerie Deutsch

James Dubin

Bob Emser

Forrest Gee

James Geier

Piero Giadrossi

Helyn Goldenberg

Christina Gospondnetich

Paul & Dedrea Gray

Richard Green

Francis Greenburger

Ralf Gschwend

Dr. LaRue Harding

Ed Hardy Habit/Hardy LLC

Michelle Hobart

Vicki Hopton

Iowa West Foundation

George Johnson

Philip & Paula Kirkeby

Howard Kirschbaum

Stephen & Frankie Knapp

Alvin & Judith Kraus

John & Deborah Lahey

Jon Lash

Eric & Audrey Lester

Daryl Lillie

Peter Lundberg

Steve Maloney

Lewis Manilow

Martin Margulies

Robert E. McKenzie &

Theresia Wolf-McKenzie

Jill & Paul Meister

Kenneth Merlau

Jon Miller

Museum of Contemporary

Art, Chicago

Alan Osborne

Raymond Nasher

Sassona Norton

Claes Oldenburg & Coosje

van Bruggen

Steven Oliver

Angelina Pacaldo

William Padnos & Mary

Pannier

Philip Palmedo

Justin Peyser

Meinhard Pfanner, art

connection international

Playboy Enterprises, Inc

Cynthia Polsky

Allen Ralston

Mel & Leta Ramos

Carl & Toni Randolph

Andre Rice

Benjamin & Donna Rosen

Milton Rosenberg

Saul Rosenzweig

Aden Ross

Carmella Saraceno

Noah Savett

Jean & Raymond V. J. Schrag

Marc Selwyn

Stephen Shapiro

Alan Shepp

Marvin & Sondra Smalley

Thomas Smith

Storm King Art Center

Julian Taub

The Todd and Betiana Simon

Foundation

Tootsie Roll Industries

William Traver Gallery

UBS Art

De Wain & Kiana Valentine

Allan & Judith Voigt

Ursula Von Rydingsvard

Alex Wagman

Michael Windfelt

Professional Circle ($350999)

_______

Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

sculpture

B

A

M S a

G E

F

Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

sculpture

B

A

M S a

G E

F

Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

sculpture

B

A

M S a

G E

F

Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

sculpture

B

A

M S a

G E

F

__________________________

Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

sculpture

B

A

M S a

G E

F

Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

sculpture

B

A

M S a

G E

F

___________________

_____________________

Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

sculpture

B

A

M S a

G E

F

Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

sculpture

B

A

M S a

G E

F

_____________________________ _________________________ __________________

Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

sculpture

B

A

M S a

G E

F

Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

sculpture

B

A

M S a

G E

F

12 Sculpture 29.1

Winners Circle

Ryan Trecartin, who works in video and sculpture, has won

the inaugural Jack Wolgin International Competition in the

Fine Arts. The other shortlisted artists for the $150,000 prize

were Sanford Biggers and Michael Rakowitz.

David Altmejd has received the $50,000 Sobey Art

Award, Canadas top prize for contemporary Canadian

art.

Isa Genzken has won the 2009 Yanghyun Prize, a

KRW100,000 international award sponsored by Koreas

Yanghyun Foundation.

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation recently

announced the shortlist for the 2010 Hugo Boss Prize. Cao Fei, Hans-Peter Feldmann, Natascha

Sadr Haghighian, Roman Ondk, Walid Raad, and Apichatpong Weerasethakul are finalists for

the eighth edition of the award.

Creative Time recently presented the inaugural Leonore Annenberg Prize for Art and Social

Change, an annual $25,000 award, to The Yes Men in honor of their legendary culture jamming.

Two Korean and two international artists are sharing the inaugural Nam June Paik Art Center

Prize, a new annual award of $50,000. Eun-me Ahn, Ceal Floyer, Seung-taek Lee, and Robert

Adrian X were selected for their embrace of technology, multi-directional communications flow,

and viewer participation.

Britains Public Monuments and Sculpture Association and the Marsh Christian Trust recently

announced the winners of the 2009 Marsh Award for Public Sculpture. Three new works were honored:

Jaume Plensas ||ecm (:o||o|e, October 2009); Sarah Lucass |e|:e.c| (:o||o|e, June 2008); and

|e ||cn by Royal College of Art graduates Hsaio-Chi Tsai and Kimiya Yoshikawa.

news

Two Cutting-Edge Commissions for MAXXI

Italys new National Museum of XXI Century Arts (MAXXI) in Rome

will soon host two commissions as innovative as its Zaha Hadid-

designed building. Jurors for the international competition MAXXI

2per100 recently selected their winning projects, one outdoor

and one indoor, from among a shortlist of 11 artists, including

Piero Golia, Jenny Holzer, Daniel Buren, and Olaf Nicolai.

Maurizio Mochettis project for the indoor atrium, ||nee |e||e o|

|o:e ne|||e|c|c :o|.|||nec, uses sculptural and lighting elements

to choreograph relations between viewers and the curving, sensu-

ous space surrounding them. According to the jury, ||nee |e||e best

interprets the conception of internal space of the museum

an ambitious design that attempts to capture contemporaneity

Hans-Peter Feldmann, Shadowplay, 2009.

Left: Massimo Grimaldi, Emergencys Paediatric Centre in Juba Supported by MAXXI.

Above: Maurizio Mochetti, 2 views of Linee rette di luce nellIperspazio curvilineo.

Newsbriefs

Olafur Eliasson, who co-designed the 2007 Serpentine

Pavilion in London, returns to architecture in an

upcoming project for Copenhagena bridge over the

Christianshavn Kanal. Eliasson says that he wants

pedestrians to come as close to the water as possible

and to make part of the structure transparent. No

timetable for the construction has been announced.

Nearly 2,000 works by Hlio Oiticica were destroyed

in an October 2009 fire at a storage facility attached

to the home of Csar Oiticica, the artists brother and

director of the nonprofit Projeto Hlio Oiticica. The

facility was equipped with a fire alarm, as well as tem-

perature and humidity controls. Investigations continue

into the cause of the fire; the works, valued at $200

million, were uninsured.

Contemporary sculpture is on hiatus fromTrafalgar

Square until later this year. After 100 days of elevating

ordinary people, along with their whims, causes,

and concerns, the Fourth Plinth nowhonors Battle of

Britain hero Air Chief Marshal Sir Keith Park. Leslie

Johnsons fiberglass statue will remain in place until

later this year, when it will be replaced by a new

commissionYinka Shonibares scale model of the

HMS |e|cn in a glass bottle. F

E

L

D

M

A

N

N

:

C

O

U

R

T

E

S

Y

3

0

3

G

A

L

L

E

R

Y

,

N

Y

/

G

R

I

M

A

L

D

I

A

N

D

M

O

C

H

E

T

T

I

:

C

O

U

R

T

E

S

Y

M

A

X

X

I

,

M

I

N

I

S

T

E

R

O

D

E

L

L

E

I

N

F

R

A

S

T

R

U

T

T

U

R

E

,

A

N

D

M

I

N

I

S

T

E

R

O

P

E

R

I

B

E

N

I

E

L

E

A

T

T

I

V

I

T

C

U

L

T

U

R

A

L

I

through flow and forward momentum. Blending essential functionality and decorative color,

Mochettis interventions offer subtle surprises and serve as what he calls a space barometer.

Massimo Grimaldis |me|en:, |ceo|c|||: ten||e |n |o|c oc||eo |, |/\\| translates

public art into direct social activism. Installed outside MAXXIs entrance, the photographic/

video work will offer a changing array of images sent from the construction and subsequent

activities at a new medical facility built by Emergency in Juba, Sudan. The pediatric center,

which will offer free, specialized cardiac services to children up to the age of 14, is being

funded with 92 percent of the artworks 700,000 budget. Back in Rome, viewers can watch

true reportage, screened in a double synchronous video-projection that links the two sites,

in Grimaldis words, by their architecturesone made possible by the other.

MAXXI 2per100which attacted 554 proposals, more than half from international

artistswas sponsored by the Inter-Regional Superintendency for Public Works of Lazio,

Abruzzo, and Sardinia, in collaboration with the PARC General Directorate for the Quality

of the Contemporary Landscape, Architecture and Art, and funded through the 2% Law.

The museum and the new commissions are slated to be inaugurated in spring 2010.

Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

sculpture

B

A

M S a

G E

F

Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

sculpture

B

A

M S a

G E

F

________________________

Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

sculpture

B

A

M S a

G E

F

Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

sculpture

B

A

M S a

G E

F

14 Sculpture 29.1

M

A

R

T

I

N

:

C

O

U

R

T

E

S

Y

S

I

E

S

+

H

K

E

,

D

S

S

E

L

D

O

R

F

/

L

P

E

Z

:

C

O

U

R

T

E

S

Y

D

E

N

V

E

R

A

R

T

M

U

S

E

U

M

/

I

G

L

E

S

I

A

S

:

C

O

U

R

T

E

S

Y

T

H

E

A

R

T

I

S

T

A

N

D

M

A

R

I

A

N

G

O

O

D

M

A

N

G

A

L

L

E

R

Y

,

N

Y

Aspen Art Museum

/en, tc|c|coc

Kris Martin

||co| |cnoc|, .!, .o:o

For Martin, time is subject, object,

and material. His arresting sculp-

tural objects and provocative con-

ceptual pieces explore the temporal

elements of creation and the futile

quest for permanence/immortality.

In a new, site-referential installa-

tion, he examines a different aspect

of hubris, constructing a rocky envi-

ronment that captures the moun-

taineers extreme compulsion to defy

peaks and conquer nature. Shifts

in scale allow viewers a heady tran-

scendental perspective that plays

with the normal course of percep-

tion. The show also features a limited

print run of Martins hand-written

edition of Fyodor Dostoevskys |e

|o|c|. Here, the novels protagonist,

Myshkin, is replaced by a doppel-

ganger named Kris Martin in a hum-

bling act of adulation and identifica-

tion with the heros desire for spiri-

tual transformation.

Tel: 970.925.8050

Web site

<www.aspenartmuseum.org>

Denver Art Museum

|en.e|

Embrace!

||co| /||| !, .o:o

While many of todays name-brand

architects would eschew Frank Lloyd

Wright, they proudly follow his exam-

ple in designing museums as sculp-

tural statementsthree-dimension-

al objects that all but eclipse their

contents. Savvy artists and curators

have now learned to treat these

sometimes difficult containers as

mutable raw material to be explored

and altered at will. In the dialogue

between art and architecture, the

building is no longer sacrosanct: Urs

Fischer, with his interventions and

multi-million-dollar modifications to

the New Museum, is just the most

extreme example. In Denver, 17

artistsincluding El Anatsui, Kristin

Baker, Katharina Grosse, Christian

Hahn, Nicola Lpez, Rupprecht

Matthies, Tobias Rehberger, Jessica

Stockholder, Timothy Weaver +

eMAD, Lawrence Weiner, and Zhong

Biaowere invited to take over the

Daniel Libeskind-designed structure

and transform its already unusual

spatial configurations. Their site-

specific commissions work with and

against the host building in order

to break down traditional barriers

between artist and viewer.

Tel: 720.865.5000

Web site

<www.denverartmuseum.org>

Fondazione Arnaldo Pomodoro

|||cn

Cristina Iglesias

||co| |e||oc|, ,, .o:o

A sculptor of mazes, trellis-work fol-

lies, and tapestry-like gardens,

Iglesias immerses viewers in spaces

of the imagination. Giant ceilings fly

through the air, intricate Moorish

screens multiply into labyrinths, and

rooms transform into forests. Fusing

traditions and techniques from archi-

tecture, theater, printmaking, and

photography, her installations

approach the world through allusion.

This show features 19 works unified

into a single intricate motif of invigo-

rating magic. Water, earth, light,

bronze gardens, living plants, and

alabaster and glass transparencies

guide viewers through a present-

day Arcadia of timeless suspension,

where matter ceases to obey the

laws of nature and crosses into the

realm of metamorphosis and myth.

Tel: + 39 (0) 289075394/5

Web site <www.

fondazionearnaldopomodoro.it>

Hamburger Kunsthalle

|cm|o|

Pedro Cabrita Reis

||co| |e||oc|, .), .o:o

Since the early 1990s, Cabrita Reiss

work has revolved around themes

of housing, habitation, construction,

and territory. A keen collector of

civilizations refuse and of evocative

itinerary

Top left: Kris Martin, Idiot. Left:

Nicola Lpez, installation for

Embrace!, view of work in pro-

gress. Above: Cristina Iglesias,

Santa Fe (Celosias I) and Santa

Fe (Celosias II).

___

_________________

Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

sculpture

B

A

M S a

G E

F

Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

sculpture

B

A

M S a

G E

F

Sculpture January/February 2010 15

sensory impressions, he finds his

inspiration in abandoned building

sites and his treasure in discards.

Like his sculptures based on com-

monplace furnishings, such as tables

and chairs and doors and windows,

his architecturally inflected installa-

tions transform the ordinary fabric

of everyday life, drab surroundings,

and banal construction materials

into new worlds that border on the

sublime. These expansive environ-

ments, often formed from complex

and imposing structures, counter

the classic white cube with massive

brick walls, found objects, industrial

neon tubes, steel girders, and rough

wooden planks. This large-scale sur-

veythe artists most comprehen-

sive to datefeatures 60 sculptures

and installations, including new

works developed especially for the

show.

Tel: + 49 (0) 40 428 131 200

Web site

<www.hamburger-kunsthalle.de>

Inverleith House

|o|n|o||

Karla Black

||co| |e||oc|, ), .o:o

Black describes her work as almost

painting, performance, or installa-

tion while actually, and quite defi-

nitely, being sculpture. Ephemeral,

floor-based pieces and remarkable

hanging sculptures appear untouch-

ably fragile, exuding a vulnerable

and provocative beauty that masks

a serious dialogue with nature and

culture. In addition to addressing

developmental experience, complete

with sensory recollections awak-

ened through powder paint, crushed

chalk, and sugar paper, her work

slyly alludes to tired associations

with the feminine. Lipstick, nail

varnish, self-tanners, and other tools

of enhancement (some permanently

wet and festering) interrupt other-

wise clean surfaces, but their role

extends beyond critique. For this

show, she has made new installa-

tions for seven rooms in Inverleith

House, all using ephemeral materi-

als to evoke the landscape.

Tel: + 44 (0) 131 248 2971

Web site <www.rbge.org.uk/

inverleith-house>

Kunsthalle Dsseldorf

|oe|oc||

Eat Art

||co| |e||oc|, .3, .o:o

As an institutionalized art form, Eat

Art originated in Dsseldorf in 1970,

when Daniel Spoerri founded the

Eat Art Galerie on Burgplaz. There,

prominent artists such as Dieter

Roth, Joseph Beuys, and Roy Licht-

enstein exhibited objects made

of food. This exhibition attempts to

document the use of edible materials

in art from the 1970s to the pre-

sent day. More than just delectable

curiosities, foodstuffs allow artists

such as Jana Sterbak, Sonja

Alhuser, and Thomas Rentmeister

to explore a wide range of con-

cernsfrom identity formation

through eating habits and rituals

to affluence and gluttony, global-

ization, trade, and the politics of

food supply.

Tel: + 49 (0) 211-89 962 43

Web site

<www.kunsthalle-duesseldorf.de>

Modern Art Oxford

0\|c|o, ||

Pawel Althamer

Miroslaw Balka

||co| |c|:| ,, .o:o

A traditional sculptor of highly real-

istic figures as well as a radical

interventionist, Althamer orches-

trates situations and events that

place real peopleincluding the

Above: Sonja Alhuser, Butterskulptur, from Eat Art. Top right: Pedro

Cabrita Reis, Les dormeurs. Right: Karla Black, Platonic Solid (detail).

A

L

H

U

S

E

R

:

V

G

B

I

L

D

-

K

U

N

S

T

,

B

O

N

N

,

2

0

0

9

/

C

A

B

R

I

T

A

R

E

I

S

:

B

L

A

I

S

E

A

D

I

L

O

N

,

P

E

D

R

O

C

A

B

R

I

T

A

R

E

I

S

/

B

L

A

C

K

:

C

O

U

R

T

E

S

Y

T

H

E

A

R

T

I

S

T

A

N

D

M

A

R

Y

M

A

R

Y

,

G

L

A

S

G

O

W

________

Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

sculpture

B

A

M S a

G E

F

Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

sculpture

B

A

M S a

G E

F

itinerary

16 Sculpture 29.1

homeless, prison inmates, illegal

workers, street musicians, and chil-

drenin alternative or parallel real-

ities where they have the power of

creative input and execution. In his

new work, tcmmcn c|, Althamer

joins neighbors from his Brodn

housing estate in an inventive form

of time travel. The show includes

various souvenirs collected by these

intrepid tourists during their travels

across the globe.

One of todays most important

sculptors, Balka translates the lan-

guage of Minimalism and conceptu-

alism into breathtaking scenarios of

subjective narrative. In conjunction

with his Unilever commission for Tate

Moderns Turbine Hall, this exhibi-

tion features a survey of related

video works. Presented as a multi-

dimensional installation, Topog-

raphy, which sifts elements of the

poetic and the insufferable from

the discordant layers of history, offers

a fresh perspective on Balkas

explorations of the body and its

limitations, memory, and the

space between looking and knowing.

Tel: + 44 (0) 1865 813830

Web site

<www.modernartoxford.org.uk>

Museum of Arts and Design

|eu 'c||

Slash: Paper Under the Knife

||co| /||| !, .o:o

The third in a series of MAD exhibi-

tions exploring the renaissance

of traditional handcraft materials in

contemporary art and design, Slash

picks up where MoMAs Paper left

off, focusing on current uses of paper

as a creative medium and source of

inspiration. Works by more than 50

artists, including Thomas Demand,

Olafur Eliasson, Tom Friedman, Nina

Katchadourian, Judy Pfaff, Lesley

Dill, and Kara Walker, demonstrate

how paper can become more than

a surface receptacle for images.

Process-oriented artists submit their

material to burning, tearing, laser-

cutting, and shredding, while others

modify books to create new objects

or use cut paper for film and video

animations. Among the highlights

of this richly diverse collection are

12 new site-specific installations by

Andreas Kocks, Clio Braga, Tomas

Rivas, and Michael Velliquette,

among others.

Tel: 212.299.7777

Web site <www.madmuseum.org>

Museum of Contemporary Art

t||:cc

Italics: Italian Art Between

Tradition and Revolution 19682008

||co| |e||oc|, :!, .o:o

Italics explores creativity, originality,

and artistic production in a country

where cultural change is all too often

weighed down by the persistence

of the past. Whether reinterpreting

historical precedent or breaking

away from tradition, Italian artists

active during the past 40 years are

at ease with the realities of social

transformation. Reflecting their idio-

syncratic paths and resisting the

artificiality of groupings and move-

ments such as Arte Povera, the show

(curated by Francesco Bonami)

attempts to counter the Italian

aversion to individuality and experi-

mentation. Works by more than 80

artists, including Mario and Marisa

Top left: Miroslaw Balka, video still from Bambi. Top right: Pawel

Althamer, Common Task, Brasilia. Left: Mia Pearlman, EDDY, from

Slash. Above: Maurizio Cattelan, All, from Italics.

B

A

L

K

A

:

M

I

R

O

S

L

A

W

B

A

L

K

A

/

A

L

T

H

A

M

E

R

:

C

O

U

R

T

E

S

Y

T

H

E

A

R

T

I

S

T

A

N

D

O

P

E

N

A

R

T

P

R

O

J

E

C

T

S

/

P

E

A

R

L

M

A

N

:

J

A

S

O

N

M

A

N

D

E

L

L

A

,

C

O

U

R

T

E

S

Y

M

U

S

E

U

M

O

F

A

R

T

S

A

N

D

D

E

S

I

G

N

/

C

A

T

T

E

L

A

N

:

C

O

U

R

T

E

S

Y

K

U

N

S

T

H

A

U

S

B

R

E

G

E

N

Z

,

B

R

E

G

E

N

Z

,

A

U

S

T

R

I

A

Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

sculpture

B

A

M S a

G E

F

Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

sculpture

B

A

M S a

G E

F

Sculpture January/February 2010 17

Merz, Alighiero Boetti, Lucio Fon-

tana, Maurizio Cattelan (who has

created a dramatic new sculpture),

Stefano Arienti, Paola Pivi, Patrick

Tuttofuoco, and Giuseppe Gabellone

span various visual media to exca-

vate an ancient and contemporary

civilization split between a glorious

past and an uncertain future.

Tel: 312.280.2660

Web site <www.mcachicago.org>

Museum of Contemporary Art

cn ||ec

Tara Donovan

||co| |e||oc|, .3, .o:o

Donovan bases each of her phenom-

enologically charged installations

on the physical properties and

structural capabilities of a single

accumulated everyday material.

In a leap from the mundane to the

miraculous, she responds to the

texture, density, mass, and size of

everything from electrical cables,

paper plates, straws, and straight

pins to roofing felt and toothpicks,

building large quantities of individual

components into distinctive forms.

Layered, twisted, piled, or clustered

with almost viral repetition, her

work grows via processes that mimic

those of the natural world while

seeming to defy the laws of nature.

This survey exhibition (at MCASDs

Jacobs Building) features 17 sculp-

tures and site-responsive installa-

tions by the MacArthur genius grant

winner.

Tel: 858.454.3541

Web site <www.mcasd.org>

Museum of Fine Arts

|co|cn

Your Bright Future: 12

Contemporary Artists from Korea

||co| |e||oc|, :!, .o:o

Your Bright Future features a gen-

eration of artists who have emerged

since the mid-1980ssome well-

known and others on the brink of

recognitionall of whom work on

the cutting- edge of international

art trends, including sculpture and

installation, video, and computer

animation, and within a distinctly

Korean context. Bahc Yiso, Choi

Jeong-Hwa, Gimhongsok, Jeon

Joonho, Kim Beom, Kim Sooja, Koo

Jeong-A, Minouk Lim, Jooyeon Park,

Do Ho Suh, Haegue Yang, and the

collaborative Young-Hae Chang

Heavy Industries came of age amid

political turmoil and increased free-

doms; their experience has inspired

work that focuses, often humorously,

on the ephemeral nature of life,

time, and identity, as well as the

limitations of communication

across languages, cultures, and

generations.

Tel: 713.639.7300

Web site <www.mfah.org>

Museum Ludwig

|c|n

Franz West

||co| |c|:| :!, .o:o

For the past 30 years, West has

played a critical role in redefining

the possibilities of sculpture as

social and environmental experi-

ence. Coming out of a powerful

1960s performance scene led by the

Viennese Actionists, he developed

an early interest in the potential

of objects to trigger an array of psy-

chological states and experiences.

His unique manipulations of found

objects, papier-mch, and furniture

inspire bizarre applications and sce-

narios. Though fundamentally sculp-

Top left: Tara Donovan, Untitled. Left: Do Ho Suh, Fallen Star 1/5, from

Your Bright Future. Above: Franz West, Caiphas & Kepler.

D

O

N

O

V

A

N

:

D

E

N

N

I

S

C

O

W

L

E

Y

,

C

O

U

R

T

E

S

Y

T

H

E

A

R

T

I

S

T

A

N

D

P

A

C

E

W

I

L

D

E

N

S

T

E

I

N

,

N

Y

/

S

U

H

:

D

O

H

O

S

U

H

,

C

O

U

R

T

E

S

Y

T

H

E

A

R

T

I

S

T

A

N

D

L

E

H

M

A

N

N

M

A

U

P

I

N

G

A

L

L

E

R

Y

,

N

Y

/

W

E

S

T

:

C

O

U

R

T

E

S

Y

G

A

G

O

S

I

A

N

G

A

L

L

E

R

Y

,

N

Y

Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

sculpture

B

A

M S a

G E

F

Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

sculpture

B

A

M S a

G E

F

18 Sculpture 29.1

tural in their construction, his works

veer toward the biomorphic and

prosthetic, possessing an awkward

beauty that responds to both

painterly abstraction and trash art.

This exhibition, devised in close col-

laboration with the artist, features

more than 90 objects, including an

outdoor sculpture and brand-new

work.

Tel: + 49 221 221 26165

Web site

<www.museum-ludwig.de>

Museum of Modern Art

|eu 'c||

Gabriel Orozco

||co| |c|:| :, .o:o

Orozco creates his sculptures, instal-

lations, photographs, and paintings

from everyday objects and situa-

tions, twisting conventional notions

of reality by inserting the ordinary

into unexpected contexts. From one

project to the next, he deliberately

blurs the boundaries between art

object and prosaic environment, sit-

uating his contributions in a hybrid

place ruled by imagination. Poetic

and intriguing, his works are influ-

enced by his extensive travels,

as well as by political commitment.

This exhibition brings many of his

works to New York for the first time,

including the now-classic |c |,

a Citron car surgically reduced to

two-thirds its normal width.

Tel: 212.708.9400

Web site <www.moma.org>

Museum of Modern Art

|eu 'c||

Paul Sietsema

||co| |e||oc|, :,, .o:o

Working in sculpture, video, and

photography, Sietsema conducts an

ongoing conceptual investigation

into the relationship between three-

dimensional objects and their two-

dimensional images. His sculptures

carefully reconstruct indigenous

artifacts, re-interpreted from black

and white reproductions found in

catalogues, archaeological manu-

als, and explorers diaries. This show

features large-format drawings, as

well as the film ||o|e ,, in which

Sietsema documents five years

of his reconstructed antiquities. As

meticulous as these reconstructions

are, their purpose is not fakery;

instead, their creation is intended

as a means to explore the passage

of time while opening a dialogue

between the conventions of making

and reproducing, between the lan-

guages of two and three dimensions.

Allowing his subjects to migrate from

a static two-dimensional source to

a three-dimensional state to a time-

based, cinematic vision, he investi-

gates how different forms of repre-

sentation affect our understanding.

Tel: 212.708.9400

Web site <www.moma.org>

Neues Museum

|o|em|e|

Daniel Buren

||co| |e||oc|, :!, .o:o

Buren is considered one of the

fiercest critics of contemporary art

and its display in museums and

galleries. For over 40 years, he has

applied his mischievous sensibility

to works that play directly on their

surroundings. From the Guggenheim

in New York to the Muse Picasso

in Paris, to various outdoor loca-

tions, he has created breathtaking

installations that give heightened

visibility to selected aspects of

reality. In Nuremberg, he brings

new perspectives to the striking

architecture of Volker Staab in

installations that combine light and

movement in singular situations.

Tel: + 49 (11) 240 20 10

Web site <www.nmn.de>

Socrates Sculpture Park

|cn ||cno t||,, |eu 'c||

Emerging Artist Fellowship

Exhibition 2009

||co| |c|:| ,, .o:o

EAF artists are selected through an

open call for proposals and awarded

a grant and residency at Socrates

outdoor studio; for many, this is

their first opportunity to work out-

side on a large scale. This years

results represent a broad range of

materials, methods, and subject

matterfrom a playfully inconve-

nient boardwalk through a grove

of trees to a visual manifestation of

childhood nightmares, an urban-

scale confectionary of threatening

proportions, and a cowardly yellow-

brick road to nowhere. Works

by David Brooks, Pilar Conde, Zack

Left: Paul Sietsema, still from Figure 3.

Above: Daniel Buren, view of

Modulation. Top right: Gabriel

Orozco, La DS. Right: Lan Tuazon,

Riot City, from Socrates, EAF 2009.

S

I

E

T

S

E

M

A

:

2

0

0

9

P

A

U

L

S

I

E

T

S

E

M

A

/

B

U

R

E

N

:

R

A

L

P

H

S

T

E

N

Z

E

L

(

Z

O

N

E

B

A

T

T

L

E

R

.

N

E

T

)

/

O

R

O

Z

C

O

:

F

L

O

R

I

A

N

K

L

E

I

N

E

F

E

N

N

,

P

A

R

I

S

,

2

0

0

9

G

A

B

R

I

E

L

O

R

O

Z

C

O

/

T

U

A

Z

O

N

:

B

I

L

Y

A

N

A

D

I

M

I

T

R

O

V

A

,

C

O

U

R

T

E

S

Y

S

O

C

R

A

T

E

S

S

C

U

L

P

T

U

R

E

P

A

R

K

Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

sculpture

B

A

M S a

G E

F

Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

sculpture

B

A

M S a

G E

F

itinerary

Sculpture January/February 2010 19

Davis, Christian de Vietri, Aaron

King, Zak Kitnick, Lynn Koble, Tamara

Kostianovsky, Mads Lynnerup, Wyatt

Nash, Navin June Norling, Andra

Stanislav, Brina Thurston, Kon

Trubkovich, Lan Tuazon, and Erik &

Ninh Vysocan are installed against

the parks spectacular waterfront

view of the Manhattan skyline.

Tel: 718.956.1819

Web site

<www.socratessculpturepark.org>

Tate Modern

|cnocn

Miroslaw Balka

||co| /||| ,, .oo)

Anyone who fears the dark should

stay away from |cu || |, Balkas

Unilever commission for Turbine

Hall. The enormous, elevated steel

chamber plunges those who climb

the ramp and enter its confines

into a pitch-black void. The matter-

of-fact title, which comes from a

Samuel Beckett novel, gives noth-

ing away. While it is intended to

be about everything and nothing,

the resonances are clear and

unremittingly bleak: the ramp at the

entrance to the Warsaw Ghetto,

the cattle cars that shipped Jews and

others to the camps, the biblical

plague of darkness, black holes, the

abyss, and eternal nothingness.

Regardless of interpretative frame,

its the experience itself that mat-

ters here, and it has been almost

unanimously praised as disturbing,

unnerving, awe-inspiring, and terri-

fying. Entering is an act of faith

in oneself and in others (the almost

invisible and equally blind others

feeling their way through the same

impenetrable darkness). Balka

hopes that people will visit |cu || |

multiple times, using it as a space

for contemplation, but its hard to

imagine that such a physical and

psychological blackout, despite the

frisson of the unknown, will inspire

the same feel- good, communal

atmosphere of Eliassons sunny

Hec||e| ||ce:|.

Tel: + 44 (0) 20 7887 8888

Web site <www.tate.org.uk>

Walker Art Center

||nnecc||

Haegue Yang

||co| |e||oc|, .3, .o:o

Working with non-traditional mate-

rials such as customized Venetian

blinds and sensory devices, includ-

ing lights, infrared heaters, scent

emitters, and fans, Yang (who repre-

sented the Republic of Korea in the

2009 Venice Biennale) constructs

complex and nuanced installations

that collapse the space between

the concrete and the ephemeral. Her

recent work explores real and

metaphorical relationships between

material surroundings and emotional

responses, attempting to give form

and meaning to experiences beyond

conventional order. Despite their

rigorous and minimal abstraction,

these micro- environments do not

negate narrative; instead, as Yang

says, they allow a narrative to be

achieved without constituting its

own limits. Her first solo museum

exhibition in the U.S. features a

major installation, 'ec|n|n |e|cn

:|c|, |eo (2008), co-commissioned

by REDCAT, Los Angeles, and the

Walker, along with selections of

recent work.

Tel: 612.375.7600

Web site <www.walkerart.org>

Whitney Museum of American Art

|eu 'c||

Roni Horn

||co| |cnoc|, .!, .o:o

From Icelands hot springs to the

murky Thames, Horn draws inspira-

tion from the elements. For more

than 30 years, she has created work

of concentrated visual power and

intellectual rigor that connects the

world around us with our interior

landscapes. Gender, identity,

androgyny, and the complex rela-

tionship between object and subject

find their equivalent resonances in

water, ice, volatile geology, and the

fluctuations of weather. Materials

used with virtuosity and sensitivity

display the same fluidity, taking on

metaphorical qualities and primal

potency. This retrospective brings

together sculptures (including

works in copper and gold, as well as

ethereal cast-glass landscape mass-

es), large-scale installations, pho-

tography, drawings, and books, all

demonstrating Horns unwavering

commitment to reconciling materi-

als and personal experience and

to tracing the ever-mutable states

of being in the world.

Tel: 212.570.3600

Web site <www.whitney.org>

Top left: Haegue Yang, Yearning

Melancholy Red. Left: Roni Horn,

Rationalists Would Wear Sombreros.

Above: Miroslaw Balka, How It Is.

Y

A

N

G

:

G

A

L

L

E

R

Y

B

A

R

B

A

R

A

W

I

E

N

,

B

E

R

L

I

N

/

H

O

R

N

:

R

O

N

I

H

O

R

N

/

B

A

L

K

A

:

C

O

U

R

T

E

S

Y

T

A

T

E

M

O

D

E

R

N

Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

sculpture

B

A

M S a

G E

F

Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

sculpture

B

A

M S a

G E

F

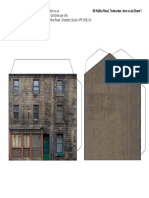

MAtt 8Akk

CairnsmoreSurfacemen

Cairnsmore of Fleet, Scotland

Sited at Cairnsmore of Fleet National Nature Reserve in southwest-

ern Scotland, Matt Bakers CairnsmoreSurfacemen scatters five

sculptural elements through the landscape to be discovered by hik-

ers. The approximately 7.5-square-mile reserve protects upland

moorland, moss-covered bog and heath habitats supporting diverse

plants and wildlife. Baker was commissioned by Scottish National

Heritage (SNH), along with the poet Mary Smith, to create works

responding to the land (the work is now managed by the Dumfries

and Galloway Arts Association). Baker describes the parallel pro-

jects as collaboration on the research aspect of the commission.

Together, they identified five dominant themesHush, Heart,

Erratic, Ocean, and Scene Shiftersthen continued independently,

with Baker using the themes as titles for individual sculptures.

He selected sites throughout the park: I was delighted by the

risk-taking attitude of the commissioner[Hush and Erratic] are in

very remote areas that require walking over challenging terrain

SNH took the position that the spirit of the place and the project

was this very terrain. His evocative works suggest the sparse

human influences on this landscape over timeHush and Heart,

in carved granite with interwoven bronze chains, both depict por-

tions of human faces emerging from the rock, and Erratic, Ocean,

and Scene Shifters incorporate mysterious tool-like forms. Bakers

works will evolve in response to the effects of nature: Moss

is growing over the subtle carving on Heartthe bronze casting in

Scene Shifters is worn away when the stream floods and abrades

the sculpture against the granite boulderErratic is moved around

the reserve by people who find it and take up the invitation to

move it. (Erratic, named for the glacial boulders that identify

patterns of ice flow, is a large piece of granite attached to a chain

and handle, enabling visitors to drag it around.)

A brochure distributed to residents in two adjoining towns

describes the sculptures and includes five related poems by

Smith, fostering a spirit of local ownership. As Baker summa-

rizes Surfacemen, the idea of finding is importantPeople

may be inspired to go looking for a sculpture but may discover

other thingsand never actually find the work. Also someone

walking in the reserve may happen across a sculpture by chance

and have a wholly fresh experience.

0tAruk fttAsson

The parliament of reality

Annandale-on-Hudson, NY

The parliament of reality, Olafur Eliassons intervention on the

campus of Bard College, offers a new way to interpret, examine,

and live in an academic environment. The site-specific work,

installed in an empty field across from the schools performing arts

center, consists of a manmade island in the center of a 135-foot-

diameter lake. Eliasson calls the islands round, flat surface, dotted

with boulders, a meeting platform. The concept refers to

the Icelandic Parliament, the Althing, meaning a space for all

things, which Eliasson interprets to include negotiation and dia-

logue, where engagement and critical reflection are the end itself,

not just the meansWith The parliament of realityI would like

to emphasize the fact that negotiation should be at the core of any

educational scheme. It is only by questioning what one is taught

that real knowledge is produced and a critical attitude sustained.

20 Sculpture 29.1

B

A

K

E

R

:

A

L

L

A

N

D

E

V

L

I

N

/

E

L

I

A

S

S

O

N

:

K

A

R

L

R

A

B

E

,

S

T

U

D

I

O

O

L

A

F

U

R

E

L

I

A

S

S

O

N

commissions

Left, top and bottom: Matt Baker, CairnsmoreSurfacemen (with Hush,

Heart, Erratic, Ocean, and Scene Shifters), 2008. Hush (top): granite, bronze

chain, and cast bronze pins, 20 in. high; Ocean (bottom): greywacke slates,

bronze chain, cast bronze yoke, glass, and sea water, 3.5 ft. wide.

commissions

Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

sculpture

B

A

M S a

G E

F

Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

sculpture

B

A

M S a

G E

F

The central island can be reached only by walking down a cov-

ered pathway of arced stainless steel. This elaborate passageway,

Eliasson says, emphasizes the transition from mainland into the

area of negotiation. Its intricate structure is inspired by research

into orientation and our experience of temporality: it cannot be

experienced at a glance, but requires time for people to move

through it. The platform itself is made of stone with an incised

pattern alluding to nautical charts and compass points, mirroring

how people align themselves with ideas and organize negotiations.

Eliassons landscape designaround the circular lake, 24 newly

planted trees will grow to create a groveheightens the difference

in perspective between viewers on the island and those standing

outside the lake.

Jaime Baird, an administrator at the Bard College Center for

Curatorial Studies, says that the work is used by students, faculty,

and staffas an informal gathering place or a place to relax; it has

also been used for classes. Responsive to [its] context, Eliasson

says, The parliament of reality challenges viewers to co-produce

[the artwork]through their perceptions and expectations.

AtunA 1AcuA

Muhammad Ali Plaza

Louisville, KY

Athena Tacha, in collaboration with the design firm EDAW, recently

designed the 5,000-square-meter Muhammad Ali Plaza, adjacent to

the Muhammad Ali Center in downtown Louisville. With a tiered

amphitheater, a waterfall, and a central illuminated fountain of 48

glass columns, the design defines the large site and unifies dis-

parate elements into a dramatic whole. The upper level supports

a paved area with Tachas gently flowing Chadar Waterfall, which

she says is reminiscent ofa standard feature of Mogul gardens.

Connected by runnels to an additional pool, water flows in a wide

curve down through the stepped seating area and into the fountain.

Tacha created the sculptural amphitheater, Dancing Steps

evocative of Alis famous dancing boxing techniqueand an

ascending fountain in the form of a spiraling [16-pointed]

starDennis Carmichael of EDAW created a spiraling pavement

radiating from the points of the star-shaped poolOne of the spi-

raling arms becomes a runnel through the amphitheater, bringing

water from the top level into the basin of Star Fountain. The foun-

tains nighttime illumination is a repeating seven-minute program

that Tacha designed in collaboration with Color Kinetics. The col-

ors twist, rise, and fall, she says, enhancing the dancing effect

of the seating while echoing the multi-colored tile faade of the

nearby Ali Center. (The fountain and waterfall were fabricated

by Architectural Glass Art, a Louisville studio.)

Tachas recently completed Friendship Plaza in Washington, DC,

also combines paving, an arcade of lighting, and a central fountain

containing an obelisk with streaming text. Like her previous

public spaces, these new plazas add life to their locations and

welcome visitors to the urban outdoors.

Elizabeth Lynch

Sculpture January/February 2010 21

E

L

I

A

S

S

O

N

:

K

A

R

L

R

A

B

E

,

S

T

U

D

I

O

O

L

A

F

U

R

E

L

I

A

S

S

O

N

/

T

A

C

H

A

:

R

I

C

H

A

R

D

E

.

S

P

E

A

R

Juries are convened each month to select works for Commissions.

Information on recently completed commissions, along with quality

35mm slides/transparencies or high-resolution digital images (300 dpi

at 4 x 5 in. minimum) and an SASE for return of slides, should