Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Attachment

Transféré par

Kate LoringCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Attachment

Transféré par

Kate LoringDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Attached:

Children Living in Institutionalised Care Facilities

by Kate Loring and Ella James

It changed my life.

As long term volunteers who are volunteering in an institutionalised care facility, we have heard this

sentence used many times to describe the experience that a volunteer has had after volunteering

their time to help care for vulnerable children. It is this sentence that has resonated with us and

caused us to reect on our own approach to volunteering, and that of our fellow volunteers. Is it

possible that we are getting so caught up with our own emotions, that we are forgetting about the

emotional needs of the children?

We would like to take this opportunity to explore the impact that short term volunteers and visitors

have on children who are living within an institutionalised care facility, and the long term effects on

the children who are being exposed to continual broken attachments.

We are both Early Childhood Educators from Australia with different looking resumes, but similar

experiences. We met at the institutionalised care facility in Vietnam last year where we spent

several months volunteering with children who have multiple and profound learning difculties,

some of whom are terminally ill. We returned home for Christmas and by the time April rolled

around, we had quit our jobs, sold our cars, left our family and friends behind and moved to

Vietnam.

We have been here long enough now to watch the dry season turn wet, and as the seasons have

changed, so have the very many faces of the constant ow of people coming and going.

Some people visit the children for a minute, an hour, a day. Some pass through the rooms, only

stopping to pose with a child, or take a photo of a baby with a swelling head. Some are unable to

hold back their tears, and stand over the beds of these children and cry. Some pick children up,

only to put them back into their bed several minutes later. Some just stare.

There are people who stay longer, for a week or two or three. They are often encouraged to make

intimate connections with the children in care. They cuddle them, feed them, play with them,

change their nappies and inhabit a part of the childrens world And then they leave. We are as

unsure as the children are, as to whether they will return or not.

In a life lled with so many inconsistencies, we have however noticed that there is always one

constant.

For anyone who has ever been to an institutionalised out of home care setting for children, you will

be able to identify the small smiling face of a child, eager to greet you, who is ready to climb onto

your knee, grab your hand or be swooped into your arms for a hug.

For us, this child is a ten year old girl. She is one of the only children amongst the sixty in the ward

where we work who is able to move and communicate independently. Despite her challenges with

steady walking, from the moment she hears voices on the stairs it takes just a few seconds for her

to cross the small room to greet them. She grins brightly with her arms raised, waiting for the next

visitor or volunteer to pick her up. She interacts with them as if she has known them for her entire

life, despite having never met them before. Most people believe that she is just a friendly kid

wanting or needing someone to play with, but it is so much more than just this

2 (2014)

To really understand what is happening for this child, and children just like her, it is necessary to

rst understand attachment.

The British psychiatrist, John Bowlby, pioneered the concept of attachment in the 1940s, and used

the term attachment bond to describe a warm, intimate and continuous relationship with a parent

or consistent caregiver in which both nd satisfaction and enjoyment. Having a secure attachment

enables a child to explore the world, learn new skills, regulate emotions and have condence that

they will be protected. Children with secure attachments build mental models of a secure self,

compassionate people and a kind world. A secure attachment frees a child from fear and anxiety

that accompanies a sense of being alone and abandoned.

1

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) states that all children have the

2

right for protection against experiences that are harmful for them. This protection includes the right

to be protected against repeated broken attachments. The Guidelines for the Alternative Care of

Children are an extension of, or an implementation guide for the CRC, highlights this right by

including the guideline that frequent changes in care settings are detrimental to the childs

development and ability to form attachments, and should be avoided. The guidelines also

recognise that a safe and continuous attachment to their caregivers, with permanency

generally being a key goal, is a basic need.

3

While all volunteers generally have good intentions, when considering the United Nations

Convention on the Rights of the Child, it cannot be denied that the revolving door of short term

volunteers and visitors, causing attachments to be continually broken, is signicantly compromising

these children's right for protection and reinforcing a cycle of abandonment.

This high turnover of visitors and short term volunteers, has been shown to negatively impact

children in care, who repeatedly try to form emotional connections with different adults. Few

tourists or volunteers are qualied to interact with traumatised and vulnerable children. Many

volunteers see it as their role to provide love and affection, thus building an emotional bond with

the children. However, when the volunteers leave, these bonds are broken and the children are

once again left feeling abandoned and confused.

4

According to Kali Miller, a Ph.D and researcher in psychology , some of the common effects of

5

insecure attachments for children experiencing constant abandonment within institutionalised care

settings are;

- behaves in an overly affectionate or indiscriminately friendly manner towards any adult (even

strangers)

- willingness to go off with unfamiliar adult with minimal or no hesitation

- supercially engaging and charming, phoney

- destructive to self, others and material things

- no impulse control, frequently acts hyperactive

- inappropriately demanding and/or clingy

- extreme attempts to control and/or manipulate

- has an excessive need for attention, praise and/or approval

- heightening their emotion expression to gain attention from adults

- overly clingy and/or proximity seeking

- trying to please the adult in order to receive praise and attention

- impaired play (often needs adult direction)

- impaired sense of trust (asking where you are going? are you coming back?)

- difculty focusing

Early insecure attachment does not necessarily predict difculties, but it is a liability for the child,

particularly if similar caregiving behaviours continue throughout childhood. Compared to that of

2 (2014)

securely attached children, the adjustment of insecure children in many spheres of life is not as

soundly based, putting their future relationships in jeopardy.

6

We are not against volunteering and we encourage and support volunteers who have given careful

consideration to the impact that they will have on the children.

For the ten year old girl we mentioned earlier, even a simple smile or a hello from a visitor or

volunteer can give her the expectation or false hope of creating a new attachment with them.

It is important for us to continually examine and adapt our own interactions and practices with all of

the children. While we are long term volunteers, it is still more important for us to reinforce and

support the attachments between the children and their primary Vietnamese caregivers who will

continue to be a constant and reliable source of care.

We have been lucky enough to witness some very genuine moments between the primary

caregivers and the children. These moments need to be celebrated and encouraged. Rather than

volunteers trying to take on a short term caregiving role, they should be advocating for the children

and their permanent caregivers to develop a more secure attachment. This means that the

permanent carers are the ones who should be doing the caregiving tasks such as; feeding,

bathing, nappy changing, comforting and playing with them. The interactions that occur during

these daily routine tasks are an important opportunity to build and secure the attachment between

the children and their permanent carers.

We ask you to imagine your own child, or a child that you love and care for, running into the arms

of stranger, attempting to secure an attachment with them, only to be left behind

This is the situation we see these children in everyday.

References

3 (2014)

John Bowlby (1988), A Secure Base: Parent-Child Attachment and Healthy Human Development. Great Britian and U.S.A. Perseus

1

Books Group.

United Nations (2013): Convention on the Rights of the Child. Adopted and opened for signature, ratication and accession by

2

General Assembly (1989) entry into force 2 September 1990, in accordance with article 49

United Nations, (2009) HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL Eleventh session. Agenda item 3.

3

UNICEF (2011), With the Best Intentions.: A study of Attitudes Towards Residential Care in Cambodia. UNICEF Cambodia Child

4

Protection Team

Kali Miller, Ph. D, 2014, Taming Tiny Tigers: Understanding and Treating Reactive Attachment Disored (RAD), Corinthia Councelling

5

Centre, Inc

Karen R. (1998). Becoming Attached: First Relationships and how they Shape Our Capasity to Love. Oxford and New York: Oxford

6

University Press

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5795)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Vespers Conversion of Saint PaulDocument7 pagesVespers Conversion of Saint PaulFrancis Carmelle Tiu DueroPas encore d'évaluation

- Alcpt 27R (Script)Document21 pagesAlcpt 27R (Script)Matt Dahiam RinconPas encore d'évaluation

- Double JeopardyDocument5 pagesDouble JeopardyDeepsy FaldessaiPas encore d'évaluation

- Torrens System: Principle of TsDocument11 pagesTorrens System: Principle of TsSyasya FatehaPas encore d'évaluation

- Capability' Brown & The Landscapes of Middle EnglandDocument17 pagesCapability' Brown & The Landscapes of Middle EnglandRogério PêgoPas encore d'évaluation

- Housing Project Process GuideDocument52 pagesHousing Project Process GuideLelethu NgwenaPas encore d'évaluation

- Oscam FilesDocument22 pagesOscam Filesvalievabduvali2001Pas encore d'évaluation

- Intro To OptionsDocument9 pagesIntro To OptionsAntonio GenPas encore d'évaluation

- Faith in GenesisDocument5 pagesFaith in Genesischris iyaPas encore d'évaluation

- APH Mutual NDA Template - V1Document4 pagesAPH Mutual NDA Template - V1José Carlos GarBadPas encore d'évaluation

- Rolando Solar's Erroneous Contention: The Evidence OnDocument6 pagesRolando Solar's Erroneous Contention: The Evidence OnLuis LopezPas encore d'évaluation

- Republic of The Philippines Department of Education Region Iv - A Calabarzon Schools Division Office of Rizal Rodriguez Sub - OfficeDocument6 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Department of Education Region Iv - A Calabarzon Schools Division Office of Rizal Rodriguez Sub - OfficeJonathan CalaguiPas encore d'évaluation

- Guyana Budget Speech 2018Document101 pagesGuyana Budget Speech 2018stabroeknewsPas encore d'évaluation

- Classification and Use of LandDocument5 pagesClassification and Use of LandShereenPas encore d'évaluation

- The River Systems of India Can Be Classified Into Four GroupsDocument14 pagesThe River Systems of India Can Be Classified Into Four Groupsem297Pas encore d'évaluation

- MidtermDocument30 pagesMidtermRona CabuguasonPas encore d'évaluation

- TcasDocument7 pagesTcasimbaPas encore d'évaluation

- 173 RevDocument131 pages173 Revmomo177sasaPas encore d'évaluation

- CPAR FLashcardDocument3 pagesCPAR FLashcardJax LetcherPas encore d'évaluation

- Code of Ethics For Public School Teacher: A. ResponsibiltyDocument6 pagesCode of Ethics For Public School Teacher: A. ResponsibiltyVerdiebon Zabala Codoy ArtigasPas encore d'évaluation

- Exam 6 PrimariaDocument5 pagesExam 6 PrimariaEdurne De Vicente PereiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Change Management and Configuration ManagementDocument5 pagesChange Management and Configuration ManagementTống Phước HuyPas encore d'évaluation

- The Customary of The House of Initia Nova - OsbDocument62 pagesThe Customary of The House of Initia Nova - OsbScott KnitterPas encore d'évaluation

- The Champion Legal Ads 04-01-21Document45 pagesThe Champion Legal Ads 04-01-21Donna S. SeayPas encore d'évaluation

- Kukurija: Shuyu KanaokaDocument10 pagesKukurija: Shuyu KanaokaMarshal MHVHZRHLPas encore d'évaluation

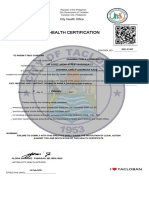

- Health CertsxDocument2 pagesHealth Certsxmark marayaPas encore d'évaluation

- Army Aviation Digest - Jan 1994Document56 pagesArmy Aviation Digest - Jan 1994Aviation/Space History Library100% (1)

- S. 1964 Child Welfare Oversight and Accountability ActDocument27 pagesS. 1964 Child Welfare Oversight and Accountability ActBeverly TranPas encore d'évaluation

- BPM at Hindustan Coca Cola Beverages - NMIMS, MumbaiDocument10 pagesBPM at Hindustan Coca Cola Beverages - NMIMS, MumbaiMojaPas encore d'évaluation

- LWB Manual PDFDocument1 pageLWB Manual PDFKhalid ZgheirPas encore d'évaluation