Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Labor Law Second Batch of Cases

Transféré par

Adrian MiraflorCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Labor Law Second Batch of Cases

Transféré par

Adrian MiraflorDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

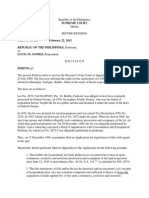

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

FIRST DIVISION

G.R. No. L-50999 March 23, 1990

JOSE SONGCO, ROMEO CIPRES, and AMANCIO MANUEL, petitioners,

vs

NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS COMMISSION (FIRST DIVISION), LABOR ARBITER FLAVIO AGUAS, and

F.E. ZUELLIG (M), INC., respondents.

RaulE.Espinosaforpetitioners.

LucasEmmanuelB.CanilaoforpetitionerA.Manuel.

Atienza,Tabora,DelRosario&Castilloforprivaterespondent.

MEDIALDEA, J.:

This is a petition for certiorari seeking to modify the decision of the National Labor Relations

Commission in NLRC Case No. RB-IV-20840-78-T entitled, "JoseSongcoandRomeoCipres,

Complainants-Appellants,v.F.E.Zuellig(M),Inc.,Respondent-Appellee" and NLRC Case No. RN-

IV-20855-78-T entitled, "AmancioManuel,Complainant-Appellant,v.F.E.Zuellig(M),Inc.,

Respondent-Appellee," which dismissed the appeal of petitioners herein and in effect affirmed

the decision of the Labor Arbiter ordering private respondent to pay petitioners separation pay

equivalent to their one month salary (exclusive of commissions, allowances, etc.) for every year

of service.

The antecedent facts are as follows:

Private respondent F.E. Zuellig (M), Inc., (hereinafter referred to as Zuellig) filed with the

Department of Labor (Regional Office No. 4) an application seeking clearance to terminate the

services of petitioners Jose Songco, Romeo Cipres, and Amancio Manuel (hereinafter referred to

as petitioners) allegedly on the ground of retrenchment due to financial losses. This application

was seasonably opposed by petitioners alleging that the company is not suffering from any

losses. They alleged further that they are being dismissed because of their membership in the

union. At the last hearing of the case, however, petitioners manifested that they are no longer

contesting their dismissal. The parties then agreed that the sole issue to be resolved is the basis

of the separation pay due to petitioners. Petitioners, who were in the sales force of Zuellig

received monthly salaries of at least P40,000. In addition, they received commissions for every

sale they made.

The collective Bargaining Agreement entered into between Zuellig and F.E. Zuellig Employees

Association, of which petitioners are members, contains the following provision (p. 71, Rollo):

ARTICLE XIV Retirement Gratuity

Section l(a)-Any employee, who is separated from employment due to old age,

sickness, death or permanent lay-off not due to the fault of said employee shall

receive from the company a retirement gratuity in an amount equivalent to one

(1) month's salary per year of service. One month of salaryas used in this

paragraph shall be deemed equivalent to the salary at date of retirement; years

of service shall be deemed equivalent to total service credits, a fraction of at least

six months being considered one year, including probationary employment.

(Emphasis supplied)

On the other hand, Article 284 of the Labor Code then prevailing provides:

Art. 284. Reductionofpersonnel. The termination of employment of any

employee due to the installation of labor saving-devices, redundancy,

retrenchment to prevent losses, and other similar causes, shall entitle the

employee affected thereby to separation pay. In case of termination due to the

installation of labor-saving devices or redundancy, the separation pay shall be

equivalent to one (1) month pay or to at least one (1) month payfor every year of

service, whichever is higher. In case of retrenchment to prevent losses and other

similar causes, the separation pay shall be equivalent to one (1) month pay or at

least one-half (1/2) month pay for every year of service, whichever is higher. A

fraction of at least six (6) months shall be considered one (1) whole year.

(Emphasis supplied)

In addition, Sections 9(b) and 10, Rule 1, Book VI of the Rules Implementing the Labor Code

provide:

x x x

Sec. 9(b). Where the termination of employment is due to retrechment initiated

by the employer to prevent losses or other similar causes, or where the employee

suffers from a disease and his continued employment is prohibited by law or is

prejudicial to his health or to the health of his co-employees, the employee shall

be entitled to termination pay equivalent at least to his one month salary, or to

one-half month pay for every year of service, whichever is higher, a fraction of at

least six (6) months being considered as one whole year.

x x x

Sec. 10. Basisofterminationpay. The computation of the termination pay of

an employee as provided herein shall be based on his latest salary rate, unless the

same was reduced by the employer to defeat the intention of the Code, in which

case the basis of computation shall be the rate before its deduction. (Emphasis

supplied)

On June 26,1978, the Labor Arbiter rendered a decision, the dispositive portion of which reads

(p. 78, Rollo):

RESPONSIVE TO THE FOREGOING, respondent should be as it is hereby, ordered

to pay the complainants separation pay equivalent to their one month salary

(exclusive of commissions, allowances, etc.) for every year of service that they

have worked with the company.

SO ORDERED.

The appeal by petitioners to the National Labor Relations Commission was dismissed for lack of

merit.

Hence, the present petition.

On June 2, 1980, the Court, acting on the verified "Notice of Voluntary Abandonment and

Withdrawal of Petition dated April 7, 1980 filed by petitioner Romeo Cipres, based on the ground

that he wants "to abide by the decision appealed from" since he had "received, to his full and

complete satisfaction, his separation pay," resolved to dismiss the petition as to him.

The issue is whether or not earned sales commissions and allowances should be included in the

monthly salary of petitioners for the purpose of computation of their separation pay.

The petition is impressed with merit.

Petitioners' position was that in arriving at the correct and legal amount of separation pay due

them, whether under the Labor Code or the CBA, their basic salary, earned sales commissions

and allowances should be added together. They cited Article 97(f) of the Labor Code which

includes commission as part on one's salary, to wit;

(f) 'Wage' paid to any employee shall mean the remuneration or earnings,

however designated, capable of being expressed in terms of money, whether

fixed or ascertained on a time, task, piece, or commission basis, or other method

of calculating the same, which is payable by an employer to an employee under a

written or unwritten contract of employment for work done or to be done, or for

services rendered or to be rendered, and includes the fair and reasonable value,

as determined by the Secretary of Labor, of board, lodging, or other facilities

customarily furnished by the employer to the employee. 'Fair reasonable value'

shall not include any profit to the employer or to any person affiliated with the

employer.

Zuellig argues that if it were really the intention of the Labor Code as well as its implementing

rules to include commission in the computation of separation pay, it could have explicitly said so

in clear and unequivocal terms. Furthermore, in the definition of the term "wage", "commission"

is used only as one of the features or designations attached to the word remuneration or

earnings.

Insofar as the issue of whether or not allowances should be included in the monthly salary of

petitioners for the purpose of computation of their separation pay is concerned, this has been

settled in the case of Santosv.NLRC,etal., G.R. No. 76721, September 21, 1987, 154 SCRA 166,

where We ruled that "in the computation of backwages and separation pay, account must be

taken not only of the basic salary of petitioner but also of her transportation and emergency

living allowances." This ruling was reiterated in Sorianov.NLRC,etal., G.R. No. 75510, October

27, 1987, 155 SCRA 124 and recently, in PlantersProducts,Inc.v.NLRC,etal.,G.R. No. 78524,

January 20, 1989.

We shall concern ourselves now with the issue of whether or not earned sales commission

should be included in the monthly salary of petitioner for the purpose of computation of their

separation pay.

Article 97(f) by itself is explicit that commission is included in the definition of the term "wage". It

has been repeatedly declared by the courts that where the law speaks in clear and categorical

language, there is no room for interpretation or construction; there is only room for application

(Cebu Portland Cement Co. v. Municipality of Naga, G.R. Nos. 24116-17, August 22, 1968, 24

SCRA 708; Gonzaga v. Court of Appeals, G.R.No. L-2 7455, June 28,1973, 51 SCRA 381). A plain

and unambiguous statute speaks for itself, and any attempt to make it clearer is vain labor and

tends only to obscurity. How ever, it may be argued that if We correlate Article 97(f) with Article

XIV of the Collective Bargaining Agreement, Article 284 of the Labor Code and Sections 9(b) and

10 of the Implementing Rules, there appears to be an ambiguity. In this regard, the Labor Arbiter

rationalized his decision in this manner (pp. 74-76, Rollo):

The definition of 'wage' provided in Article 96 (sic) of the Code can be correctly be

(sic) stated as a general definition. It is 'wage ' in its generic sense. A careful

perusal of the same does not show any indication that commission is part of

salary. We can say that commission by itself may be considered a wage. This is not

something novel for it cannot be gainsaid that certain types of employees like

agents, field personnel and salesmen do not earn any regular daily, weekly or

monthly salaries, but rely mainly on commission earned.

Upon the other hand, the provisions of Section 10, Rule 1, Book VI of the

implementing rules in conjunction with Articles 273 and 274 (sic) of the Code

specifically states that the basis of the termination pay due to one who is sought

to be legally separated from the service is 'his latest salary rates.

x x x.

Even Articles 273 and 274 (sic) invariably use 'monthly pay or monthly salary'.

The above terms found in those Articles and the particular Rules were

intentionally used to express the intent of the framers of the law that for

purposes of separation pay they mean to be specifically referring to salary only.

.... Each particular benefit provided in the Code and other Decrees on Labor has

its own pecularities and nuances and should be interpreted in that light. Thus, for

a specific provision, a specific meaning is attached to simplify matters that may

arise there from. The general guidelines in (sic) the formation of specific rules for

particular purpose. Thus, that what should be controlling in matters concerning

termination pay should be the specific provisions of both Book VI of the Code and

the Rules. At any rate, settled is the rule that in matters of conflict between the

general provision of law and that of a particular- or specific provision, the latter

should prevail.

On its part, the NLRC ruled (p. 110, Rollo):

From the aforequoted provisions of the law and the implementing rules, it could

be deduced that wage is used in its generic sense and obviously refers to the

basic wage rate to be ascertained on a time, task, piece or commission basis or

other method of calculating the same. It does not, however, mean that

commission, allowances or analogous income necessarily forms part of the

employee's salary because to do so would lead to anomalies (sic), if not absurd,

construction of the word "salary." For what will prevent the employee from

insisting that emergency living allowance, 13th month pay, overtime, and

premium pay, and other fringe benefits should be added to the computation of

their separation pay. This situation, to our mind, is not the real intent of the Code

and its rules.

We rule otherwise. The ambiguity between Article 97(f), which defines the term 'wage' and

Article XIV of the Collective Bargaining Agreement, Article 284 of the Labor Code and Sections

9(b) and 10 of the Implementing Rules, which mention the terms "pay" and "salary", is more

apparent than real. Broadly, the word "salary" means a recompense or consideration made to a

person for his pains or industry in another man's business. Whether it be derived from

"salarium," or more fancifully from "sal," the pay of the Roman soldier, it carries with it the

fundamental idea of compensation for services rendered. Indeed, there is eminent authority for

holding that the words "wages" and "salary" are in essence synonymous (Words and Phrases,

Vol. 38 Permanent Edition, p. 44 citing Hopkins vs. Cromwell, 85 N.Y.S. 839,841,89 App. Div. 481;

38 Am. Jur. 496). "Salary," the etymology of which is the Latin word "salarium," is often used

interchangeably with "wage", the etymology of which is the Middle English word "wagen". Both

words generally refer to one and the same meaning, that is, a reward or recompense for services

performed. Likewise, "pay" is the synonym of "wages" and "salary" (Black's Law Dictionary, 5th

Ed.). Inasmuch as the words "wages", "pay" and "salary" have the same meaning, and

commission is included in the definition of "wage", the logical conclusion, therefore, is, in the

computation of the separation pay of petitioners, their salary base should include also their

earned sales commissions.

The aforequoted provisions are not the only consideration for deciding the petition in favor of

the petitioners.

We agree with the Solicitor General that granting, ingratiaargumenti, that the commissions

were in the form of incentives or encouragement, so that the petitioners would be inspired to

put a little more industry on the jobs particularly assigned to them, still these commissions are

direct remuneration services rendered which contributed to the increase of income of Zuellig .

Commission is the recompense, compensation or reward of an agent, salesman, executor,

trustees, receiver, factor, broker or bailee, when the same is calculated as a percentage on the

amount of his transactions or on the profit to the principal (Black's Law Dictionary, 5th Ed., citing

Weiner v. Swales, 217 Md. 123, 141 A.2d 749, 750). The nature of the work of a salesman and

the reason for such type of remuneration for services rendered demonstrate clearly that

commission are part of petitioners' wage or salary. We take judicial notice of the fact that some

salesmen do not receive any basic salary but depend on commissions and allowances or

commissions alone, are part of petitioners' wage or salary. We take judicial notice of the fact

that some salesman do not received any basic salary but depend on commissions and allowances

or commissions alone, although an employer-employee relationship exists. Bearing in mind the

preceeding dicussions, if we adopt the opposite view that commissions, do not form part of

wage or salary, then, in effect, We will be saying that this kind of salesmen do not receive any

salary and therefore, not entitled to separation pay in the event of discharge from employment.

Will this not be absurd? This narrow interpretation is not in accord with the liberal spirit of our

labor laws and considering the purpose of separation pay which is, to alleviate the difficulties

which confront a dismissed employee thrown the the streets to face the harsh necessities of life.

Additionally, in Sorianov.NLRC,etal.,supra, in resolving the issue of the salary base that should

be used in computing the separation pay, We held that:

The commissions also claimed by petitioner ('override commission' plus 'net

deposit incentive') are not properly includible in such base figure since such

commissions must be earned by actual market transactions attributable to

petitioner.

Applying this by analogy, since the commissions in the present case were earned by actual

market transactions attributable to petitioners, these should be included in their separation pay.

In the computation thereof, what should be taken into account is the average commissions

earned during their last year of employment.

The final consideration is, in carrying out and interpreting the Labor Code's provisions and its

implementing regulations, the workingman's welfare should be the primordial and paramount

consideration. This kind of interpretation gives meaning and substance to the liberal and

compassionate spirit of the law as provided for in Article 4 of the Labor Code which states that

"all doubts in the implementation and interpretation of the provisions of the Labor Code

including its implementing rules and regulations shall be resolved in favor of labor" (Abella v.

NLRC, G.R. No. 71812, July 30,1987,152 SCRA 140; Manila Electric Company v. NLRC, et al., G.R.

No. 78763, July 12,1989), and Article 1702 of the Civil Code which provides that "in case of

doubt, all labor legislation and all labor contracts shall be construed in favor of the safety and

decent living for the laborer.

ACCORDINGLY, the petition is hereby GRANTED. The decision of the respondent National Labor

Relations Commission is MODIFIED by including allowances and commissions in the separation

pay of petitioners Jose Songco and Amancio Manuel. The case is remanded to the Labor Arbiter

for the proper computation of said separation pay.

SO ORDERED.

Narvasa(Chairman),Cruz,GancaycoandGrio-Aquino,JJ.,concur.

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

THIRD DIVISION

G.R. No. 121927 April 22, 1998

ANTONIO W. IRAN (doing business under the name and style of Tones Iran

Enterprises), petitioner,

vs.

NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS COMMISSION (Fourth Division), GODOFREDO O. PETRALBA,

MORENO CADALSO, PEPITO TECSON, APOLINARIO GOTHONG GEMINA, JESUS BANDILAO, EDWIN

MARTIN, CELSO LABIAGA, DIOSDADO GONZALGO, FERNANDO M. COLINA, respondents.

ROMERO, J.:

Whether or not commissions are included in determining compliance with the minimum wage

requirement is the principal issue presented in this petition.

Petitioner Antonio Iran is engaged in softdrinks merchandising and distribution in Mandaue City,

Cebu, employing truck drivers who double as salesmen, truck helpers, and non-field personnel in

pursuit thereof. Petitioner hired private respondents Godofredo Petralba, Moreno Cadalso,

Celso Labiaga and Fernando Colina as drivers/salesmen while private respondents Pepito Tecson,

Apolinario Gimena, Jesus Bandilao, Edwin Martin and Diosdado Gonzalgo were hired as truck

helpers. Drivers/salesmen drove petitioner's delivery trucks and promoted, sold and delivered

softdrinks to various outlets in Mandaue City. The truck helpers assisted in the delivery of

softdrinks to the different outlets covered by the driver/salesmen.

As part of their compensation, the driver/salesmen and truck helpers of petitioner received

commissions per case of softdrinks sold at the following rates:

SALESMEN:

Ten Centavos (P0.10) per case of Regular softdrinks.

Twelve Centavos (P0.12) per case of Family Size softdrinks.

TRUCK HELPERS:

Eight Centavos (P0.08) per case of Regular softdrinks.

Ten Centavos (P0.10) per case of Family Size softdrinks.

Sometime in June 1991, petitioner, while conducting an audit of his operations, discovered cash

shortages and irregularities allegedly committed by private respondents. Pending the

investigation of irregularities and settlement of the cash shortages, petitioner required private

respondents to report for work everyday. They were not allowed, however, to go on their

respective routes. A few days thereafter, despite aforesaid order, private respondents stopped

reporting for work, prompting petitioner to conclude that the former had abandoned their

employment. Consequently, petitioner terminated their services. He also filed on November 7,

1991, a complaint for estafa against private respondents.

On the other hand, private respondents, on December 5, 1991, filed complaints against

petitioner for illegal dismissal, illegal deduction, underpayment of wages, premium pay for

holiday and rest day, holiday pay, service incentive leave pay, 13th month pay, allowances,

separation pay, recovery of cash bond, damages and attorney's fees. Said complaints were

consolidated and docketed as Rab VII-12-1791-91, RAB VII-12-1825-91 and RAB VII-12-1826-91,

and assigned to Labor Arbiter Ernesto F. Carreon.

The labor arbiter found that petitioner had validly terminated private respondents, there being

just cause for the latter's dismissal. Nevertheless, he also ruled that petitioner had not complied

with minimum wage requirements in compensating private respondents, and had failed to pay

private respondents their 13th month pay. The labor arbiter, thus, rendered a decision on

February 18, 1993, the dispositive portion of which reads:

WHEREFORE, premises considered, judgment is hereby rendered ordering the

respondent Antonio W. Iran to pay the complainants the following:

1. Celso Labiaga P10,033.10

2. Godofredo Petralba 1,250.00

3. Fernando Colina 11,753.10

4. Moreno Cadalso 11,753.10

5. Diosdado Gonzalgo 7,159.04

6. Apolinario Gimena 8,312.24

7. Jesus Bandilao 14,729.50

8. Pepito Tecson. 9,126.55

Attorney's Fees (10%) 74,116.63

of the gross award 7,411.66

GRAND TOTAL AWARD P81,528.29

========

The other claims are dismissed for lack of merit.

SO ORDERED.

1

Both parties seasonably appealed to the NLRC, with petitioner contesting the labor arbiter's

refusal to include the commissions he paid to private respondents in determining compliance

with the minimum wage requirement. He also presented, for the first time on appeal, vouchers

denominated as 13th month pay signed by private respondents, as proof that petitioner had

already paid the latter their 13th month pay. Private respondents, on the other hand, contested

the findings of the labor arbiter holding that they had not been illegally dismissed, as well as

mathematical errors in computing Jesus Bandilao's wage differentials. The NLRC, in its decision

of December 21, 1994, affirmed the validity of private respondent's dismissal, but found that

said dismissal did not comply with the procedural requirements for dismissing employees.

Furthermore, it corrected the labor arbiter's award of wage differentials to Jesus Bandilao. The

dispositive portion of said decision reads:

WHEREFORE, premises considered, the decision is hereby MODIFIED in that

complainant Jesus Bandilao's computation for wage differential is corrected from

P154.00 to P4,550.00. In addition to all the monetary claim (sic) originally

awarded by the Labor Arbiter aquo, P1,000.00 is hereby granted to each

complainants (sic) as indemnity fee for failure of respondents to observe

procedural due process.

SO ORDERED.

2

Petitioner's motion for reconsideration of said decision was denied on July 31, 1995, prompting

him to elevate this case to this Court, raising the following issues:

1. THE HONORABLE COMMISSION ACTED WITH GRAVE ABUSE OF DISCRETION

AND CONTRARY TO LAW AND JURISPRUDENCE IN AFFIRMING THE DECISION OF

THE LABOR ARBITER AQUOEXCLUDING THE COMMISSIONS RECEIVED BY THE

PRIVATE RESPONDENTS IN COMPUTING THEIR WAGES;

2. THE HONORABLE COMMISSION ACTED WITH GRAVE ABUSE OF DISCRETION IN

FINDING PETITIONER GUILTY OF PROCEDURAL LAPSES IN TERMINATING PRIVATE

RESPONDENTS AND IN AWARDING EACH OF THE LATTER P1,000.00 AS

INDEMNITY FEE;

3. THE HONORABLE COMMISSION GRAVELY ERRED IN NOT CREDITING THE

ADVANCE AMOUNT RECEIVED BY THE PRIVATE RESPONDENTS AS PART OF THEIR

13TH MONTH PAY.

The petition is impressed with merit.

The NLRC, in denying petitioner's claim that commissions be included in determining compliance

with the minimum wage ratiocinated thus:

Respondent (petitioner herein) insist assiduously that the commission should be

included in the computation of actual wages per agreement. We will not fall prey

to this fallacious argument. An employee should receive the minimum wage as

mandated by law and that the attainment of the minimum wage should not be

dependent on the commission earned by an employee. A commission is an

incentive for an employee to work harder for a better production that will benefit

both the employer and the employee. To include the commission in the

computation of wage in order to comply with labor standard laws is to negate the

practice that a commission is granted after an employee has already earned the

minimum wage or even beyond it.

3

This holding is unsupported by law and jurisprudence. Article 97(f) of the Labor Code defines

wage as follows:

Art. 97(f) "Wage" paid to any employee shall mean the remuneration or

earnings, however designated, capable of being expressed in terms of money,

whether fixed or ascertained on a time, task, piece, or commissionbasis, or other

method of calculating the same, which is payable by an employer to an employee

under a written or unwritten contract of employment for work done or to be

done, or for services rendered or to be rendered and includes the fair and

reasonable value, as determined by the Secretary of Labor, of board, lodging, or

other facilities customarily furnished by the employer to the employee.

xxx xxx xxx (Emphasis supplied)

This definition explicitly includes commissions as part of wages. While commissions are, indeed,

incentives or forms of encouragement to inspire employees to put a little more industry on the

jobs particularly assigned to them, still these commissions are direct remunerations for services

rendered. In fact, commissions have been defined as the recompense, compensation or reward

of an agent, salesman, executor, trustee, receiver, factor, broker or bailee, when the same is

calculated as a percentage on the amount of his transactions or on the profit to the principal.

The nature of the work of a salesman and the reason for such type of remuneration for services

rendered demonstrate clearly that commissions are part of a salesman's wage or salary.

4

Thus, the commissions earned by private respondents in selling softdrinks constitute part of the

compensation or remuneration paid to drivers/salesmen and truck helpers for serving as such,

and hence, must be considered part of the wages paid them.

The NLRC asserts that the inclusion of commissions in the computation of wages would negate

the practice of granting commissions only after an employee has earned the minimum wage or

over. While such a practice does exist, the universality and prevalence of such a practice is

questionable at best. In truth, this Court has taken judicial notice of the fact that some salesmen

do not receive any basic salary but depend entirely on commissions and allowances or

commissions alone, although an employer-employee relationship exists.

5

Undoubtedly, this

salary structure is intended for the benefit of the corporation establishing such, on the apparent

assumption that thereby its salesmen would be moved to greater enterprise and diligence and

close more sales in the expectation of increasing their sales commissions. This, however, does

not detract from the character of such commissions as part of the salary or wage paid to each of

its salesmen for rendering services to the corporation.

6

Likewise, there is no law mandating that commissions be paid only after the minimum wage has

been paid to the employee. Verily, the establishment of a minimum wage only sets a floor below

which an employee's remuneration cannot fall, not that commissions are excluded from wages

in determining compliance with the minimum wage law. This conclusion is bolstered

by PhilippineAgriculturalCommercialandIndustrialWorkersUnionvs. NLRC,

7

where this Court

acknowledged that drivers and conductors who are compensated purely on a commission basis

are automatically entitled to the basic minimum pay mandated by law should said commissions

be less than their basic minimum for eight hours work. It can, thus, be inferred that were said

commissions equal to or even exceed the minimum wage, the employer need not pay, in

addition, the basic minimum pay prescribed by law. It follows then that commissions are

included in determining compliance with minimum wage requirements.

With regard to the second issue, it is settled that in terminating employees, the employer must

furnish the worker with two written notices before the latter can be legally terminated: (a) a

notice which apprises the employee of the particular acts or omissionsforwhichhisdismissalis

sought, and (b) the subsequent notice which informs the employee of the employer's decision to

dismiss him.

8

(Emphasis ours) Petitioner asseverates that no procedural lapses were committed

by him in terminating private respondents. In his own words:

. . . when irregularities were discovered, that is, when the misappropriation of

several thousands of pesos was found out, the petitioner instructed private

respondents to report back for work and settle their accountabilities but the

latter never reported for work. This instruction by the petitioner to report back

for work and settle their accountabilities served as notices to private respondents

for the latter to explain or account for the missing funds held in trust by them

before they disappeared.

9

Petitioner considers this return-to-work order as equivalent to the first notice apprising the

employee of the particular acts or omissions for which his dismissal is sought. But by petitioner's

own admission, private respondents were never told in said notice that their dismissal was being

sought, only that they should settle their accountabilities. In petitioner's incriminating words:

It should be emphasized here that at the time the misappropriation was

discovered and subsequently thereafter, the petitioner's first concern was not

effecting the dismissal of private respondents but the recovery of the

misappropriated funds thus the latter were advised to report back to work.

10

As above-stated, the first notice should inform the employee that his dismissal is being sought.

Its absence in the present case makes the termination of private respondents defective, for

which petitioner must be sanctioned for his non-compliance with the requirements of or for

failure to observe due process.

11

The twin requirements of notice and hearing constitute the

essential elements of due process, and neither of these elements can be disregarded without

running afoul of the constitutional guarantee. Not being mere technicalities but the very essence

of due process, to which every employee is entitled so as to ensure that the employer's

prerogative to dismiss is not exercised arbitrarily,

12

these requisites must be complied with

strictly.

Petitioner makes much capital of private respondents' failure to report to work, construing the

same as abandonment which thus authorized the latter's dismissal. As correctly pointed out by

the NLRC, to which the Solicitor General agreed, Section 2 of Book V, Rule XIV of the Omnibus

Rules Implementing the Labor Code requires that in cases of abandonment of work, notice

should be sent to the worker's last known address. If indeed private respondents had abandoned

their jobs, it was incumbent upon petitioner to comply with this requirement. This, petitioner

failed to do, entitling respondents to nominal damages in the amount of P5,000.00 each, in

accordance with recent jurisprudence,

13

to vindicate or recognize their right to procedural due

process which was violated by petitioner.

Lastly, petitioner argues that the NLRC gravely erred when it disregarded the vouchers presented

by the former as proof of his payment of 13th month pay to private respondents. While

admitting that said vouchers covered only a ten-day period, petitioner argues that the same

should be credited as amounts received by private respondents as part of their 13th month pay,

Section 3(e) of the Rules and Regulations Implementing P.D. No. 851 providing that the employer

shall pay the difference when he pays less than 1/12th of the employee's basic salary.

14

While it is true that the vouchers evidencing payments of 13th month pay were submitted only

on appeal, it would have been more in keeping with the directive of Article 221

15

of the Labor

Code for the NLRC to have taken the same into account.

16

Time and again, we have allowed

evidence to be submitted on appeal, emphasizing that, in labor cases, technical rules of evidence

are not binding.

17

Labor officials should use every and all reasonable means to ascertain the

facts in each case speedily and objectively, without regard to technicalities of law or

procedure.

18

It must also be borne in mind that the intent of P.D. No. 851 is the granting of additional income

in the form of 13th month pay to employees not as yet receiving the same and not that a double

burden should be imposed on the employer who is already paying his employees a 13th month

pay or its equivalent.

19

An employer who pays less than 1/12th of the employees basic salary as

their 13th month pay is only required to pay the difference.

20

The foregoing notwithstanding, the vouchers presented by petitioner covers only a particular

year. It does not cover amounts for other years claimed by private respondents. It cannot be

presumed that the same amounts were given on said years. Hence, petitioner is entitled to

credit only the amounts paid for the particular year covered by said vouchers.

WHEREFORE, in view of the foregoing, the decision of the NLRC dated July 31, 1995, insofar as it

excludes the commissions received by private respondents in the determination of petitioner's

compliance with the minimum wage law, as well as its exclusion of the particular amounts

received by private respondents as part of their 13th month pay is REVERSED and SET ASIDE. This

case is REMANDED to the Labor Arbiter for a recomputation of the alleged deficiencies. For non-

observance of procedural due process in effecting the dismissal of private respondents, said

decision is MODIFIED by increasing the award of nominal damages to private respondents from

P1,000.00 to P5,000.00 each. No costs.

SO ORDERED.

Narvasa,C.J.,KapunanandPurisima,JJ.,concur.

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

FIRST DIVISION

G.R. No. L-44169 December 3, 1985

ROSARIO A. GAA, petitioner,

vs.

THE HONORABLE COURT OF APPEALS, EUROPHIL INDUSTRIES CORPORATION, and CESAR R.

ROXAS, Deputy Sheriff of Manila, respondents.

FedericoC.AlikpalaandFedericoY.Alikpala,Jr.forpetitioner.

BorbeandPalmaforprivaterespondent.

PATAJO, J.:

This is a petition for review on certiorari of the decision of the Court of Appeals promulgated on

March 30, 1976, affirming the decision of the Court of First Instance of Manila.

It appears that respondent Europhil Industries Corporation was formerly one of the tenants in

Trinity Building at T.M. Kalaw Street, Manila, while petitioner Rosario A. Gaa was then the

building administrator. On December 12, 1973, Europhil Industries commenced an action (Civil

Case No. 92744) in the Court of First Instance of Manila for damages against petitioner "for

having perpetrated certain acts that Europhil Industries considered a trespass upon its rights,

namely, cutting of its electricity, and removing its name from the building directory and gate

passes of its officials and employees" (p. 87 Rollo). On June 28, 1974, said court rendered

judgment in favor of respondent Europhil Industries, ordering petitioner to pay the former the

sum of P10,000.00 as actual damages, P5,000.00 as moral damages, P5,000.00 as exemplary

damages and to pay the costs.

The said decision having become final and executory, a writ of garnishment was issued pursuant

to which Deputy Sheriff Cesar A. Roxas on August 1, 1975 served a Notice of Garnishment upon

El Grande Hotel, where petitioner was then employed, garnishing her "salary, commission

and/or remuneration." Petitioner then filed with the Court of First Instance of Manila a motion

to lift said garnishment on the ground that her "salaries, commission and, or remuneration are

exempted from execution under Article 1708 of the New Civil Code. Said motion was denied by

the lower Court in an order dated November 7, 1975. A motion for reconsideration of said order

was likewise denied, and on January 26, 1976 petitioner filed with the Court of Appeals a

petition for certiorari against filed with the Court of Appeals a petition for certiorari against said

order of November 7, 1975.

On March 30, 1976, the Court of Appeals dismissed the petition for certiorari. In dismissing the

petition, the Court of Appeals held that petitioner is not a mere laborer as contemplated under

Article 1708 as the term laborer does not apply to one who holds a managerial or supervisory

position like that of petitioner, but only to those "laborers occupying the lower strata." It also

held that the term "wages" means the pay given" as hire or reward to artisans, mechanics,

domestics or menial servants, and laborers employed in manufactories, agriculture, mines, and

other manual occupation and usually employed to distinguish the sums paid to persons hired to

perform manual labor, skilled or unskilled, paid at stated times, and measured by the day, week,

month, or season," citing 67 C.J. 285, which is the ordinary acceptation of the said term, and that

"wages" in Spanish is "jornal" and one who receives a wage is a "jornalero."

In the present petition for review on certiorari of the aforesaid decision of the Court of Appeals,

petitioner questions the correctness of the interpretation of the then Court of Appeals of Article

1708 of the New Civil Code which reads as follows:

ART. 1708. The laborer's wage shall not be subject to execution or attachment,

except for debts incurred for food, shelter, clothing and medical attendance.

It is beyond dispute that petitioner is not an ordinary or rank and file laborer but "a responsibly

place employee," of El Grande Hotel, "responsible for planning, directing, controlling, and

coordinating the activities of all housekeeping personnel" (p. 95, Rollo) so as to ensure the

cleanliness, maintenance and orderliness of all guest rooms, function rooms, public areas, and

the surroundings of the hotel. Considering the importance of petitioner's function in El Grande

Hotel, it is undeniable that petitioner is occupying a position equivalent to that of a managerial

or supervisory position.

In its broadest sense, the word "laborer" includes everyone who performs any kind of mental or

physical labor, but as commonly and customarily used and understood, it only applies to one

engaged in some form of manual or physical labor. That is the sense in which the courts

generally apply the term as applied in exemption acts, since persons of that class usually look to

the reward of a day's labor for immediate or present support and so are more in need of the

exemption than are other. (22 Am. Jur. 22 citing Briscoevs.Montgomery,93 Ga 602, 20 SE

40;Millervs.Dugas,77 Ga 4 Am St Rep 192; StateexrelI.X.L.Groceryvs. Land, 108 La 512, 32 So

433; Wildnervs.Ferguson,42 Minn 112, 43 NW 793; 6 LRA 338; Anno 102 Am St Rep. 84.

In Olivervs.MaconHardwareCo.,98 Ga 249 SE 403, it was held that in determining whether a

particular laborer or employee is really a "laborer," the character of the word he does must be

taken into consideration. He must be classified not according to the arbitrary designation given

to his calling, but with reference to the character of the service required of him by his employer.

In Wildnervs.Ferguson,42 Minn 112, 43 NW 793, the Court also held that all men who earn

compensation by labor or work of any kind, whether of the head or hands, including judges,

laywers, bankers, merchants, officers of corporations, and the like, are in some sense "laboring

men." But they are not "laboring men" in the popular sense of the term, when used to refer to a

must presume, the legislature used the term. The Court further held in said case:

There are many cases holding that contractors, consulting or assistant engineers,

agents, superintendents, secretaries of corporations and livery stable keepers, do

not come within the meaning of the term. (Powellv.Eldred,39 Mich, 554, Atkinv.

Wasson,25 N.Y. 482; Shortv.Medberry,29 Hun. 39; Deanv.DeWolf,16 Hun.

186; Krausenv.Buckel,17 Hun. 463; Ericsonv.Brown,39 Barb. 390; Coffinv.

Reynolds,37 N.Y. 640; Brusiev.Griffith,34 Cal. 306; Davev.Nunan,62 Cal. 400).

Thus, inJonesvs.Avery, 50 Mich, 326, 15 N.W. Rep. 494, it was held that a traveling salesman,

selling by sample, did not come within the meaning of a constitutional provision making

stockholders of a corporation liable for "labor debts" of the corporation.

In Klinevs.Russell 113 Ga. 1085, 39 SE 477, citing Olivervs.MaconHardwareCo.,supra,it was

held that a laborer, within the statute exempting from garnishment the wages of a "laborer," is

one whose work depends on mere physical power to perform ordinary manual labor, and not

one engaged in services consisting mainly of work requiring mental skill or business capacity, and

involving the exercise of intellectual faculties.

So, also in Wakefieldvs.Fargo, 90 N.Y. 213, the Court, in construing an act making stockholders

in a corporation liable for debts due "laborers, servants and apprentices" for services performed

for the corporation, held that a "laborer" is one who performs menial or manual services and

usually looks to the reward of a day's labor or services for immediate or present support. And

in Weymouthvs.Sanborn,43 N.H. 173, 80 Am. Dec. 144, it was held that "laborer" is a term

ordinarily employed to denote one who subsists by physical toil in contradistinction to those who

subsists by professional skill. And in ConsolidatedTankLineCo.vs.Hunt,83 Iowa, 6, 32 Am. St.

Rep. 285, 43 N.W. 1057, 12 L.R.A. 476, it was stated that "laborers" are those persons who earn

a livelihood by their own manual labor.

Article 1708 used the word "wages" and not "salary" in relation to "laborer" when it declared

what are to be exempted from attachment and execution. The term "wages" as distinguished

from "salary", applies to the compensation for manual labor, skilled or unskilled, paid at stated

times, and measured by the day, week, month, or season, while "salary" denotes a higher degree

of employment, or a superior grade of services, and implies a position of office: by contrast, the

term wages " indicates considerable pay for a lower and less responsible character of

employment, while "salary" is suggestive of a larger and more important service (35 Am. Jur.

496).

The distinction between wages and salary was adverted to inBellvs.IndianLivestockCo.(Tex.

Sup.), 11 S.W. 344, wherein it was said: "'Wages' are the compensation given to a hired person

for service, and the same is true of 'salary'. The words seem to be synonymous, convertible

terms, though we believe that use and general acceptation have given to the word 'salary' a

significance somewhat different from the word 'wages' in this: that the former is understood to

relate to position of office, to be the compensation given for official or other service, as

distinguished from 'wages', the compensation for labor." Annotation 102 Am. St. Rep. 81, 95.

We do not think that the legislature intended the exemption in Article 1708 of the New Civil

Code to operate in favor of any but those who are laboring men or women in the sense that

their work is manual. Persons belonging to this class usually look to the reward of a day's labor

for immediate or present support, and such persons are more in need of the exemption than any

others. Petitioner Rosario A. Gaa is definitely not within that class.

We find, therefore, and so hold that the Trial Court did not err in denying in its order of

November 7, 1975 the motion of petitioner to lift the notice of garnishment against her salaries,

commission and other remuneration from El Grande Hotel since said salaries, Commission and

other remuneration due her from the El Grande Hotel do not constitute wages due a laborer

which, under Article 1708 of the Civil Code, are not subject to execution or attachment.

IN VIEW OF THE FOREGOING, We find the present petition to be without merit and hereby

AFFIRM the decision of the Court of Appeals, with costs against petitioner.

SO ORDERED.

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

FIRST DIVISION

G.R. No. 164772 June 8, 2006

EQUITABLE BANKING CORPORATION (now known as EQUITABLE-PCI BANK), petitioner,

vs.

RICARDO SADAC, Respondent.

D E C I S I O N

CHICO-NAZARIO, J.:

Before Us is a Petition for Review on Certiorari with Motion to Refer the Petition to the Court En

Banc filed by Equitable Banking Corporation (now known as Equitable-PCI Bank), seeking to

reverse the Decision

1

and Resolution

2

of the Court of Appeals, dated 6 April 2004 and 28 July

2004, respectively, as amended by the Supplemental Decision

3

dated 26 October 2004 in CA-G.R.

SP No. 75013, which reversed and set aside the Resolutions of the National Labor Relations

Commission (NLRC), dated 28 March 2001 and 24 September 2002 in NLRC-NCR Case No. 00-11-

05252-89.

The Antecedents

As culled from the records, respondent Sadac was appointed Vice President of the Legal

Department of petitioner Bank effective 1 August 1981, and subsequently General Counsel

thereof on 8 December 1981. On 26 June 1989, nine lawyers of petitioner Banks Legal

Department, in a letter-petition to the Chairman of the Board of Directors, accused respondent

Sadac of abusive conduct, inter alia, and ultimately, petitioned for a change in leadership of the

department. On the ground of lack of confidence in respondent Sadac, under the rules of client

and lawyer relationship, petitioner Bank instructed respondent Sadac to deliver all materials in

his custody in all cases in which the latter was appearing as its counsel of record. In reaction

thereto, respondent Sadac requested for a full hearing and formal investigation but the same

remained unheeded. On 9 November 1989, respondent Sadac filed a complaint for illegal

dismissal with damages against petitioner Bank and individual members of the Board of Directors

thereof. After learning of the filing of the complaint, petitioner Bank terminated the services of

respondent Sadac. Finally, on 10 August 1989, respondent Sadac was removed from his office

and ordered disentitled to any compensation and other benefits.

4

In a Decision

5

dated 2 October 1990, Labor Arbiter Jovencio Ll. Mayor, Jr., dismissed the

complaint for lack of merit. On appeal, the NLRC in its Resolution

6

of 24 September 1991

reversed the Labor Arbiter and declared respondent Sadacs dismissal as illegal. The decretal

portion thereof reads, thus:

WHEREFORE, in view of all the foregoing considerations, let the Decision of October 2, 1990 be,

as it is hereby, SET ASIDE, and a new one ENTERED declaring the dismissal of the complainant as

illegal, and consequently ordering the respondents jointly and severally to reinstate him to his

former position as bank Vice-President and General Counsel without loss of seniority rights and

other privileges, and to pay him full backwages and other benefits from the time his

compensation was withheld to his actual reinstatement, as well as moral damages of

P100,000.00, exemplary damages of P50,000.00, and attorneys fees equivalent to Ten Percent

(10%) of the monetary award. Should reinstatement be no longer possible due to strained

relations, the respondents are ordered likewise jointly and severally to grant separation pay at

one (1) month per year of service in the total sum of P293,650.00 with backwages and other

benefits from November 16, 1989 to September 15, 1991 (cut off date, subject to adjustment)

computed at P1,055,740.48, plus damages of P100,000.00 (moral damages), P50,000.00

(exemplary damages) and attorneys fees equal to Ten Percent (10%) of all the monetary award,

or a grand total of P1,649,329.53.

7

Petitioner Bank came to us for the first time via a Special Civil Action for Certiorari assailing the

NLRC Resolution of 24 September 1991 in Equitable Banking Corporation v. National Labor

Relations Commission, docketed as G.R. No. 102467.

8

In our Decision

9

of 13 June 1997, we held respondent Sadacs dismissal illegal. We said that the

existence of the employer-employee relationship between petitioner Bank and respondent

Sadac had been duly established bringing the case within the coverage of the Labor Code, hence,

we did not permit petitioner Bank to rely on Sec. 26, Rule 138

10

of the Rules of Court, claiming

that the association between the parties was one of a client-lawyer relationship, and, thus, it

could terminate at any time the services of respondent Sadac. Moreover, we did not find that

respondent Sadacs dismissal was grounded on any of the causes stated in Article 282 of the

Labor Code. We similarly found that petitioner Bank disregarded the procedural requirements in

terminating respondent Sadacs employment as so required by Section 2 and Section 5, Rule XIV,

Book V of the Implementing Rules of the Labor Code. We decreed:

WHEREFORE, the herein questioned Resolution of the NLRC is AFFIRMED with the following

MODIFICATIONS: That private respondent shall be entitled to backwages from termination of

employment until turning sixty (60) years of age (in 1995) and, thereupon, to retirement benefits

in accordance with law; that private respondent shall be paid an additional amount of P5,000.00;

that the award of moral and exemplary damages are deleted; and that the liability herein

pronounced shall be due from petitioner bank alone, the other petitioners being absolved from

solidary liability. No costs.

11

On 28 July 1997, our Decision in G.R. No. 102467 dated 13 June 1997 became final and

executory.

12

Pursuant thereto, respondent Sadac filed with the Labor Arbiter a Motion for

Execution

13

thereof. Likewise, petitioner Bank filed a Manifestation and Motion

14

praying that

the award in favor of respondent Sadac be computed and that after payment is made, petitioner

Bank be ordered forever released from liability under said judgment.

Per respondent Sadacs computation, the total amount of the monetary award is P6,030,456.59,

representing his backwages and other benefits, including the general increases which he should

have earned during the period of his illegal termination. Respondent Sadac theorized that he

started with a monthly compensation of P12,500.00 in August 1981, when he was appointed as

Vice President of petitioner Banks Legal Department and later as its General Counsel in

December 1981. As of November 1989, when he was dismissed illegally, his monthly

compensation amounted to P29,365.00 or more than twice his original compensation. The

difference, he posited, can be attributed to the annual salary increases which he received

equivalent to 15 percent (15%) of his monthly salary.

Respondent Sadac anchored his claim on Article 279 of the Labor Code of the Philippines, and

cited as authority the cases of East Asiatic Company, Ltd. v. Court of Industrial Relations,

15

St.

Louis College of Tuguegarao v. National Labor Relations Commission,

16

and Sigma Personnel

Services v. National Labor Relations Commission.

17

According to respondent Sadac, the catena of

cases uniformly holds that it is the obligation of the employer to pay an illegally dismissed

employee the whole amount of the salaries or wages, plus all other benefits and bonuses and

general increases to which he would have been normally entitled had he not been dismissed;

and therefore, salary increases should be deemed a component in the computation of

backwages. Moreover, respondent Sadac contended that his check-up benefit, clothing

allowance, and cash conversion of vacation leaves must be included in the computation of his

backwages.

Petitioner Bank disputed respondent Sadacs computation. Per its computation, the amount of

monetary award due respondent Sadac is P2,981,442.98 only, to the exclusion of the latters

general salary increases and other claimed benefits which, it maintained, were unsubstantiated.

The jurisprudential precedent relied upon by petitioner Bank in assailing respondent Sadacs

computation is Evangelista v. National Labor Relations Commission,

18

citing Paramount Vinyl

Products Corp. v. National Labor Relations Commission,

19

holding that an unqualified award of

backwages means that the employee is paid at the wage rate at the time of his dismissal.

Furthermore, petitioner Bank argued before the Labor Arbiter that the award of salary

differentials is not allowed, the established rule being that upon reinstatement, illegally

dismissed employees are to be paid their backwages without deduction and qualification as to

any wage increases or other benefits that may have been received by their co-workers who were

not dismissed or did not go on strike.

On 2 August 1999, Labor Arbiter Jovencio Ll. Mayor, Jr. rendered an Order

20

adopting

respondent Sadacs computation. In the main, the Labor Arbiter relying on Millares v. National

Labor Relations Commission

21

concluded that respondent Sadac is entitled to the general

increases as a component in the computation of his backwages. Accordingly, he awarded

respondent Sadac the amount of P6,030,456.59 representing his backwages inclusive of

allowances and other claimed benefits, namely check-up benefit, clothing allowance, and cash

conversion of vacation leave plus 12 percent (12%) interest per annum equivalent to

P1,367,590.89 as of 30 June 1999, or a total of P7,398,047.48. However, considering that

respondent Sadac had already received the amount of P1,055,740.48 by virtue of a Writ of

Execution

22

earlier issued on 18 January 1999, the Labor Arbiter directed petitioner Bank to pay

respondent Sadac the amount of P6,342,307.00. The Labor Arbiter also granted an award of

attorneys fees equivalent to ten percent (10%) of all monetary awards, and imposed a 12

percent (12%) interest per annum reckoned from the finality of the judgment until the

satisfaction thereof.

The Labor Arbiter decreed, thus:

WHEREFORE, in view of al (sic) the foregoing, let an "ALIAS" Writ of Execution be issued

commanding the Sheriff, this Branch, to collect from respondent Bank the amount of

Ph6,342,307.00 representing the backwages with 12% interest per annum due complainant.

23

Petitioner Bank interposed an appeal with the NLRC, which reversed the Labor Arbiter in a

Resolution,

24

promulgated on 28 March 2001. It ratiocinated that the doctrine on general

increases as component in computing backwages in Sigma Personnel Services and St. Louis was

merely obiter dictum. The NLRC found East Asiatic Co., Ltd. inapplicable on the ground that the

original circumstances therein are not only peculiar to the said case but also completely strange

to the case of respondent Sadac. Further, the NLRC disallowed respondent Sadacs claim to

check-up benefit ratiocinating that there was no clear and substantial proof that the same was

being granted and enjoyed by other employees of petitioner Bank. The award of attorneys fees

was similarly deleted.

The dispositive portion of the Resolution states:

WHEREFORE, the instant appeal is considered meritorious and accordingly, the computation

prepared by respondent Equitable Banking Corporation on the award of backwages in favor of

complainant Ricardo Sadac under the decision promulgated by the Supreme Court on June 13,

1997 in G.R. No. 102476 in the aggregate amount of P2,981,442.98 is hereby ordered.

25

Respondent Sadacs Motion for Reconsideration thereon was denied by the NLRC in its

Resolution,

26

promulgated on 24 September 2002.

Aggrieved, respondent Sadac filed before the Court of Appeals a Petition for Certiorari seeking

nullification of the twin resolutions of the NLRC, dated 28 March 2001 and 24 September 2002,

as well as praying for the reinstatement of the 2 August 1999 Order of the Labor Arbiter.

For the resolution of the Court of Appeals were the following issues, viz.:

(1) Whether periodic general increases in basic salary, check-up benefit, clothing

allowance, and cash conversion of vacation leave are included in the computation of full

backwages for illegally dismissed employees;

(2) Whether respondent is entitled to attorneys fees; and

(3) Whether respondent is entitled to twelve percent (12%) per annum as interest on all

accounts outstanding until full payment thereof.

Finding for respondent Sadac (therein petitioner), the Court of Appeals rendered a Decision on 6

April 2004, the dispositive portion of which is quoted hereunder:

WHEREFORE, premises considered, the March 28, 2001 and the September 24, 2002 Resolutions

of the National Labor Relations Commissions (sic) are REVERSED and SET ASIDE and the August 2,

1999 Order of the Labor Arbiter is REVIVED to the effect that private respondent is DIRECTED TO

PAY petitioner the sum of PhP6,342,307.00, representing full back wages (sic) which sum

includes annual general increases in basic salary, check-up benefit, clothing allowance, cash

conversion of vacation leave and other sundry benefits plus 12% per annum interest on

outstanding balance from July 28, 1997 until full payment.

Costs against private respondent.

27

The Court of Appeals, citing East Asiatic held that respondent Sadacs general increases should

be added as part of his backwages. According to the appellate court, respondent Sadacs

entitlement to the annual general increases has been duly proven by substantial evidence that

the latter, in fact, enjoyed an annual increase of more or less 15 percent (15%). Respondent

Sadacs check-up benefit, clothing allowance, and cash conversion of vacation leave were

similarly ordered added in the computation of respondent Sadacs basic wage.

Anent the matter of attorneys fees, the Court of Appeals sustained the NLRC. It ruled that our

Decision

28

of 13 June 1997 did not award attorneys fees in respondent Sadacs favor as there

was nothing in the aforesaid Decision, either in the dispositive portion or the body thereof that

supported the grant of attorneys fees. Resolving the final issue, the Court of Appeals imposed a

12 percent (12%) interest per annum on the total monetary award to be computed from 28 July

1997 or the date our judgment in G.R. No. 102467 became final and executory until fully paid at

which time the quantification of the amount may be deemed to have been reasonably

ascertained.

On 7 May 2004, respondent Sadac filed a Partial Motion for Reconsideration

29

of the 6 April 2004

Court of Appeals Decision insofar as the appellate court did not award him attorneys fees.

Similarly, petitioner Bank filed a Motion for Partial Reconsideration thereon. Following an

exchange of pleadings between the parties, the Court of Appeals rendered a Resolution,

30

dated

28 July 2004, denying petitioner Banks Motion for Partial Reconsideration for lack of merit.

Assignment of Errors

Hence, the instant Petition for Review by petitioner Bank on the following assignment of errors,

to wit:

(a) The Hon. Court of Appeals erred in ruling that general salary increases should be

included in the computation of full backwages.

(b) The Hon. Court of Appeals erred in ruling that the applicable authorities in this case

are: (i) East Asiatic, Ltd. v. CIR, 40 SCRA 521 (1971); (ii) St. Louis College of Tuguegarao v.

NLRC, 177 SCRA 151 (1989); (iii) Sigma Personnel Services v. NLRC, 224 SCRA 181 (1993);

and (iv) Millares v. NLRC, 305 SCRA 500 (1999) and not (i) Art. 279 of the Labor Code; (ii)

Paramount Vinyl Corp. v. NLRC, 190 SCRA 525 (1990); (iii) Evangelista v. NLRC, 249 SCRA

194 (1995); and (iv) Espejo v. NLRC, 255 SCRA 430 (1996).

(c) The Hon. Court of Appeals erred in ruling that respondent is entitled to check-up

benefit, clothing allowance and cash conversion of vacation leaves notwithstanding that

respondent did not present any evidence to prove entitlement to these claims.

(d) The Hon. Court of Appeals erred in ruling that respondent is entitled to be paid legal

interest even if the principal amount due him has not yet been correctly and finally

determined.

31

Meanwhile, on 26 October 2004, the Court of Appeals rendered a Supplemental Decision

granting respondent Sadacs Partial Motion for Reconsideration and amending the dispositive

portion of the 6 April 2004 Decision in this wise, viz.:

WHEREFORE, premises considered, the March 24 (sic), 2001 and the September 24, 2002

Resolutions of the National Labor Relations Commission are hereby REVERSED and SET ASIDE

and the August 2, 1999 Order of the Labor Arbiter is hereby REVIVED to the effect that private

respondent is hereby DIRECTED TO PAY petitioner the sum of P6,342,307.00, representing full

backwages which sum includes annual general increases in basic salary, check-up benefit,

clothing allowance, cash conversion of vacation leave and other sundry benefits "and attorneys

fees equal to TEN PERCENT (10%) of all the monetary award" plus 12% per annum interest on all

outstanding balance from July 28, 1997 until full payment.

Costs against private respondent.

32

On 22 November 2004, petitioner Bank filed a Supplement to Petition for Review

33

contending in

the main that the Court of Appeals erred in issuing the Supplemental Decision by directing

petitioner Bank to pay an additional amount to respondent Sadac representing attorneys fees

equal to ten percent (10%) of all the monetary award.

The Courts Ruling

I.

We are called to write finis to a controversy that comes to us for the second time. At the core of

the instant case are the divergent contentions of the parties on the manner of computation of

backwages.

Petitioner Bank asseverates that Article 279 of the Labor Code of the Philippines does not

contemplate the inclusion of salary increases in the definition of "full backwages." It controverts

the reliance by the appellate court on the cases of (i) East Asiatic; (ii) St. Louis; (iii) Sigma

Personnel; and (iv) Millares. While it is in accord with the pronouncement of the Court of

Appeals that Republic Act No. 6715, in amending Article 279, intends to give more benefits to

workers, petitioner Bank submits that the Court of Appeals was in error in relying on East Asiatic

to support its finding that salary increases should be included in the computation of backwages

as nowhere in Article 279, as amended, are salary increases spoken of. The prevailing rule in the

milieu of the East Asiatic doctrine was to deduct earnings earned elsewhere from the amount of

backwages payable to an illegally dismissed employee.

Petitioner Bank posits that even granting that East Asiatic allowed general salary increases in the

computation of backwages, it was because the inclusion was purposely to cushion the blow of

the deduction of earnings derived elsewhere; with the amendment of Article 279 and the

consequent elimination of the rule on the deduction of earnings derived elsewhere, the rationale

for including salary increases in the computation of backwages no longer exists. On the

references of salary increases in the aforementioned cases of (i) St. Louis; (ii) Sigma Personnel;

and (iii) Millares, petitioner Bank contends that the same were merely obiter dicta. In fine,

petitioner Bank anchors its claim on the cases of (i) Paramount Vinyl Products Corp. v. National

Labor Relations Commission;

34

(ii) Evangelista v. National Labor Relations Commission;

35

and (iii)

Espejo v. National Labor Relations Commission,

36

which ruled that an unqualified award of

backwages is exclusive of general salary increases and the employee is paid at the wage rate at

the time of the dismissal.

For his part, respondent Sadac submits that the Court of Appeals was correct when it ruled that

his backwages should include the general increases on the basis of the following cases, to wit: (i)

East Asiatic; (ii) St. Louis; (iii) Sigma Personnel; and (iv) Millares.

Resolving the protracted litigation between the parties necessitates us to revisit our

pronouncements on the interpretation of the term backwages. We said that backwages in

general are granted on grounds of equity for earnings which a worker or employee has lost due

to his illegal dismissal.

37

It is not private compensation or damages but is awarded in furtherance

and effectuation of the public objective of the Labor Code. Nor is it a redress of a private right

but rather in the nature of a command to the employer to make public reparation for dismissing

an employee either due to the formers unlawful act or bad faith.

38

The Court, in the landmark

case of Bustamante v. National Labor Relations Commission,

39

had the occasion to explicate on

the meaning of full backwages as contemplated by Article 279

40

of the Labor Code of the

Philippines, as amended by Section 34 of Rep. Act No. 6715. The Court in Bustamante said, thus:

The Court deems it appropriate, however, to reconsider such earlier ruling on the computation

of backwages as enunciated in said Pines City Educational Center case, by now holding that

conformably with the evident legislative intent as expressed in Rep. Act No. 6715, above-quoted,

backwages to be awarded to an illegally dismissed employee, should not, as a general rule, be

diminished or reduced by the earnings derived by him elsewhere during the period of his illegal

dismissal. The underlying reason for this ruling is that the employee, while litigating the legality

(illegality) of his dismissal, must still earn a living to support himself and family, while full

backwages have to be paid by the employer as part of the price or penalty he has to pay for

illegally dismissing his employee. The clear legislative intent of the amendment in Rep. Act No.

6715 is to give more benefits to workers than was previously given them under the Mercury

Drug rule or the "deduction of earnings elsewhere" rule. Thus, a closer adherence to the

legislative policy behind Rep. Act No. 6715 points to "full backwages" as meaning exactly that,

i.e., without deducting from backwages the earnings derived elsewhere by the concerned

employee during the period of his illegal dismissal. In other words, the provision calling for "full

backwages" to illegally dismissed employees is clear, plain and free from ambiguity and,

therefore, must be applied without attempted or strained interpretation. Index animi sermo

est.

41

Verily, jurisprudence has shown that the definition of full backwages has forcefully evolved. In

Mercury Drug Co., Inc. v. Court of Industrial Relations,

42

the rule was that backwages were

granted for a period of three years without qualification and without deduction, meaning, the

award of backwages was not reduced by earnings actually earned by the dismissed employee

during the interim period of the separation. This came to be known as the Mercury Drug

rule.

43

Prior to the Mercury Drug ruling in 1974, the total amount of backwages was reduced by

earnings obtained by the employee elsewhere from the time of the dismissal to his

reinstatement. The Mercury Drug rule was subsequently modified in Ferrer v. National Labor

Relations Commission

44

and Pines City Educational Center v. National Labor Relations

Commission,

45

where we allowed the recovery of backwages for the duration of the illegal

dismissal minus the total amount of earnings which the employee derived elsewhere from the

date of dismissal up to the date of reinstatement, if any. In Ferrer and in Pines, the three-year

period was deleted, and instead, the dismissed employee was paid backwages for the entire

period that he was without work subject to the deductions, as mentioned. Finally came our

ruling in Bustamante which superseded Pines City Educational Center and allowed full recovery

of backwages without deduction and without qualification pursuant to the express provisions of

Article 279 of the Labor Code, as amended by Rep. Act No. 6715, i.e., without any deduction of

income the employee may have derived from employment elsewhere from the date of his

dismissal up to his reinstatement, that is, covering the entirety of the period of the dismissal.

The first issue for our resolution involves another aspect in the computation of full backwages,

mainly, the basis of the computation thereof. Otherwise stated, whether general salary increases

should be included in the base figure to be used in the computation of backwages.

In so concluding that general salary increases should be made a component in the computation

of backwages, the Court of Appeals ratiocinated, thus:

The Supreme Court held in East Asiatic, Ltd. v. Court of Industrial Relations, 40 SCRA 521 (1971)

that "general increases" should be added as a part of full backwages, to wit:

In other words, the just and equitable rule regarding the point under discussion is this: It is the

obligation of the employer to pay an illegally dismissed employee or worker the whole amount

of the salaries or wages, plus all other benefits and bonuses and general increases, to which he

would have been normally entitled had he not been dismissed and had not stopped working, but

it is the right, on the other hand of the employer to deduct from the total of these, the amount

equivalent to the salaries or wages the employee or worker would have earned in his old

employment on the corresponding days he was actually gainfully employed elsewhere with an

equal or higher salary or wage, such that if his salary or wage in his other employment was less,

the employer may deduct only what has been actually earned.

The doctrine in East Asiatic was subsequently reiterated, in the cases of St. Louis College of

Tugueg[a]rao v. NLRC, 177 SCRA 151 (1989); Sigma Personnel Services v. NLRC, 224 SCRA 181

(1993) and Millares v. National Labor Relations Commission, 305 SCRA 500 (1999).

Private respondent, in opposing the petitioners contention, alleged in his Memorandum that

only the wage rate at the time of the employees illegal dismissal should be considered private

respondent citing the following decisions of the Supreme Court: Paramount Vinyl Corp. v. NLRC

190 SCRA 525 (1990); Evangelista v. NLRC, 249 SCRA 194 (1995); Espejo v. NLRC, 255 SCRA 430

(1996) which rendered obsolete the ruling in East Asiatic, Ltd. v. Court of Industrial Relations, 40

SCRA 521 (1971).

We are not convinced.

The Supreme Court had consistently held that payment of full backwages is the price or penalty

that the employer must pay for having illegally dismissed an employee.

In Ala Mode Garments, Inc. v. NLRC 268 SCRA 497 (1997) and Bustamante v. NLRC and Evergreen

Farms, Inc. 265 SCRA 61 (1996) the Supreme Court held that the clear legislative intent in the

amendment in Republic Act 6715 was to give more benefits to workers than was previously

given them under the Mercury Drug rule or the "deductions of earnings elsewhere" rule.

The Paramount Vinyl, Evangelista, and Espejo cases cited by private respondent are inapplicable

to the case at bar. The doctrines therein came about as a result of the old Mercury Drug rule,

which was repealed with the passage of Republic Act 6715 into law. It was in Alex Ferrer v. NLRC

255 SCRA 430 (1993) when the Supreme Court returned to the doctrine in East Asiatic, which

was soon supplanted by the case of Bustamante v. NLRC and Evergreen Farms, Inc., which held

that the backwages to be awarded to an illegally dismissed employee, should not, as a general

rule, be diminished or reduced by the earnings derived from him during the period of his illegal

dismissal. Furthermore, the Mercury Drug rule was never meant to prejudice the workers, but

merely to speed the recovery of their backwages.

Ever since Mercury Drug Co. Inc. v. CIR 56 SCRA 694 (1974), it had been the intent of the

Supreme Court to increase the backwages due an illegally dismissed employee. In the Mercury

Drug case, full backwages was to be recovered even though a three-year limitation on recovery

of full backwages was imposed in the name of equity. Then in Bustamante, full backwages was

interpreted to mean absolutely no deductions regardless of the duration of the illegal dismissal.

In Bustamante, the Supreme Court no longer regarded equity as a basis when dealing with illegal

dismissal cases because it is not equity at play in illegal dismissals but rather, it is employers

obligation to pay full back wages (sic). It is an obligation of the employer because it is "the price

or penalty the employer has to pay for illegally dismissing his employee."

The applicable modern definition of full backwages is now found in Millares v. National Labor

Relations Commission 305 SCRA 500 (1999), where although the issue in Millares concerned

separation pay separation pay and backwages both have employees wage rate at their

foundation.

x x x The rationale is not difficult to discern. It is the obligation of the employer to pay an illegally

dismissed employee the whole amount of his salaries plus all other benefits, bonuses and

general increases to which he would have been normally entitled had he not been dismissed and

had not stopped working. The same holds true in case of retrenched employees. x x x

x x x x

x x x Annual general increases are akin to "allowances" or "other benefits."

46

(Italics ours.)

We do not agree.

Attention must be called to Article 279 of the Labor Code of the Philippines, as amended by

Section 34 of Rep. Act No. 6715. The law provides as follows:

ART. 279. Security of Tenure. In cases of regular employment, the employer shall not terminate

the services of an employee except for a just cause or when authorized by this Title. An