Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Articolo-581 Different Translation Strategies For Luigi Pirandello's La Giara

Transféré par

uobraziljaTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Articolo-581 Different Translation Strategies For Luigi Pirandello's La Giara

Transféré par

uobraziljaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Mirjam Friediger 2006

1

Different translation strategies for Luigi Pirandellos La Giara

The Italian short story La Giara, first published in the Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera in

1909, about two monomaniacs, the stingy and hostile landlord Don Loll Zirafa and the old and

proud jar mender Uncle Dima Licasi, is written in a rich and metaphoric language with regional

(Sicilian) linguistic characteristics. The translator of this text therefore has to choose whether to

attempt to make a word-to-word translation or rather endeavour to reproduce the feeling of the

text.

In the translation into English by Stanley Appelbaum from 1994, the first translation strategy is the

dominant one. Appelbaum translates every Italian word into (one of) its English equivalent(s) in a

very consistent manner.

This is an optimal strategy choice since the translation is meant to appear

next to the Italian original version in a dual-language book containing eleven of Pirandellos short

stories, created for English speaking students of Italian language and literature. With this type of

translation it is possible to constantly compare the two texts and go back and forth between them,

thus being able to read (or at least get an impression of) the original version without a perfect Italian

comprehension ability. The translation serves, so to say, as an aid to enter the original text, and does

not therefore need to transmit the richness of the Italian language; this will be transmitted by the

original text itself once it is read (with the help of the English translation). As a result, the English

language in this translation (being completely bound by the original) seems lifeless and complicated

and does not represent Pirandellos writing very well, since what might work in Italian does not

necessarily do so in English.

A translation into German by Hans Hinterhuser, which appear in a German collection of

Pirandellos short stories from 1997, seems to be concentrated more on conveying the sensation of

the text to the reader, rather than present a disciplined text loyal translation. This translation

which, contrary to the English one, has to stand alone is much clearer and seems to have its own

distinctiveness; its own life. Obviously, this translation is not meant to serve as a language aid and

is certainly not apt to do so, as the translator has chosen to make several modifications of the

original text in order to make the story and the stile work in the German language. Not only does

he omit words, but he also alters whole paragraphs and changes the order of them. In a sense it

seems as if Hinterhuser tries to create a German Pirandello.

Mirjam Friediger 2006

2

In comparing the two different translations I will focus solely on the very first part of the text,

which I find quite emblematic for the two different translation strategies.

Starting off with the title, both translations exemplify the jar to be an oil jar (in English The Oil

Jar, in German Der lkrug). A giara is however not necessarily meant for oil, as it is the case in

this short story, and the former English translation was in effect simply The Jar, which seems a

more precise translation. Apart from this consensus regarding the title of the story, the two

translations take separate directions in terms of translation method.

The first phrase of the text is perhaps the most difficult to translate because of its compactness and

use of agricultural metaphors:

Piena anche per gli olivi, quellannata. Piante massaie, cariche lanno avanti, avevano

raffermato tutte, a dispetto della nebbia che le aveva oppresse sul fiorire.

The English translation is:

A bumper crop of olives, too, that year. Productive trees, laden down the year before,

had all borne firm fruit, in spite of the fog that had stifled them when in blossom.

The first line keeps the syntactical form of the original without a verb, but as a translation for the

simple piena per gli olivi [italics added] the translator chooses the more practical a bumper crop

of olives [italics added]. Piena refers to a noun (with a feminine genus), but the fact that this

noun is not specified, gives the phrase an interpretative quality; the reader has to fill out the

Leerstelle

1

. Appelbaum does the filling out for the reader and interprets the noun to be raccolta/

coltura (English: crop), and in doing this he makes the phrase loose the dynamism it has in its

original version.

The piante massaie becomes productive trees, which again is a very flat

translation with the explicit noun trees instead of the more suggestive piante and the adjective

productive which gives more businesslike associations than the untranslatable massaie which

suggests something female, fertile and authentically rural.

As done in the translation of the word piena, Appelbaum chooses to translate

cariche with two words: laden down. It gives the same meaning as in Italian, but offers a

slightly different image of the olive trees, which in Italian seems to be bursting with fruit in an

1

Term from the Reception Theoy of Wolfgang Iser, translated as gap or blank.

Mirjam Friediger 2006

3

almost carnal sense (a signification which was first implied by the piante massaie), while the

English version gives the more innocent image of the branches being so heavy with fruit as to reach

for the ground below.

The verb raffermare means to renew but is translated borne firm fruit, perhaps

since it is an untranslatable agricultural term.

The rest of the translation of this first paragraph is very precise and loyal to the

original; not a word is left out or invented, and the syntax is kept intact.

The German translation is also rather loyal to this first part of the text but does insert slight

inventions to make the text more comprehensible for the reader:

Auch die Oliven brachten eine reiche Ernte. Schon im vorausgegangenen Jahr hatten die

braven Bume ber und ber vollgehangen; jetzt trugen sie aber mals eine ergiebige Last,

trotz des Nebels, der sie whrend der Bltezeit heimgesucht hatte.

The first insertion appears already in the first line as the verb bringen (to bring, here in past

tense plural: brachten). Where the English version kept unrevised the Italian construction without

a verb, the German version makes the meaning of the phrase more transparent by inserting a verb.

The same intention seems to be the case for the next phrase which begins with the addition schon

(already) and is followed in the succeeding phrase by jetzt (now) clarifying the temporal

levels of the text.

As in the English translation, piena becomes reiche Ernte, which means more or

less the same as bumper crop.

The piante massaie turn into brave Bame in German, which seems even more

off than the English productive trees. Baum means tree, but the adjective brav is like the

English brave, which does have the connotation good/ excellent, but lacks the significance of

fertile.

Cariche is translated into ber und ber vollgehangen which very nearly

transmits the sense of abundance and the trees bursting with fruits, accentuated through the

repetition of ber as well as the for the purpose invented composite adjective vollgehangen

(hanging full).

As in the English translation, the German translator chooses to rewrite the phrase

avevano raffermato tutte, but this time a little more elaborated and perhaps even closer to the

original meaning than the English translation. As mentioned, the phrase starts with jetzt to

emphasize the time relation (last year now). trugen sie eine ergiebige Last is close to the

Mirjam Friediger 2006

4

English had all borne firm fruit, even though the Italian tutte expressed by all in the English

version is missing in German, but trugen sie does imply a plural (they bore) and so the sense is

transmitted by the pronoun (and the form of the verb, which is not morphologically possible in

English). The heavy pluperfect which was maintained in the English version even though the

participle raffermato was not directly translated, becomes a past tense in German, which is made

possible by the change of the comma into semicolon and the insertion of jetzt, and so once again

the German version proves to be more light (as was the case with the insertion of the verb bringen

in the first phrase). Ergiebige Last (fertile load) refers to the connotations of massaie, which

were not successfully expressed by the adjective brav used for the trees earlier in the sentence.

Another addition abermals conveys the sense of to renew in raffermare, and so the sense in

the whole from the original is maintained in this German translation.

We have seen from the analysis of the translations of the first paragraph of La giara, that the

antiquated, dense, and metaphoric language of Pirandello is difficult to reproduce in the two

Germanic languages English and German, and that it is necessary to make certain changes to make

the language flow while keeping the original signification, as has been done in the German

translation. The English version on the other hand comes out heavier than the Italian original which

it so accurately attempts to follow.

A consideration of the second paragraph of the short story will make this even more evident. The

original text is:

Lo Zirafa, che ne aveva un bel giro nel suo podere delle Quote a Primosole, prevedendo

che le cinque giare vecchie di coccio smaltato, che aveva in cantina, non sarebbero

bastate a contener tutto lolio della nuova raccolta, ne aveva ordinata a tempo una

sesta pi capace a Santo Stefano di Camastra, dove si fabbricavano: alta a petto

duomo, bella panciuta e maestosa, che fosse delle altre cinque la badessa.

Except for a few necessary alterations, the English translation is once again very precise and

devoted to the original:

Zirafa, who had a fair number of them on his farm Le Quote at Primosole, foreseeing

that the five old glazed ceramic oil jars he had in his cellar wouldnt be enough to hold

all the oil from the new harvest, had ordered a sixth, larger one in advance from Santo

Mirjam Friediger 2006

5

Stefano di Camastra, where they were made: as tall as a mans chest, beautiful, big-

bellied and majestic, it would be the abbess of the five others.

Merely mentioning the linguistic adaptations, the first word lo is a definite article which for

linguistic reasons can not be translated (in English the only definite article is the which is not

placed in front of personal names). Regarding the translation of Un bel giro, it can either be

interpreted to have the abstract meanings; giro daffari (turnover) or the stroll one can take in

the olive garden belonging to Zirafa. A more concrete meaning would be the perimeter of the olive

garden. Appelbaum has chosen this third and more concrete meaning, but instead of designating the

size of the land, he indicates directly the number of trees, a fair number (referring to the object in

the Italian version ne; the olive trees). Appelbaum suggest the same concrete translation of the

abstract expression nel suo podere delle Quote, which is translated with on his farm Le Quote;

the Italian text holds implicit that Le Quote is a farm and mainly states that Zirafa is the owner

(once again a dynamic aspect of the text which activates the reader to fill out the gaps), but in this

case, the translator is forced to be more explicit for fear of being confusing. Another insertion is the

personal pronoun in in his cellar which is a necessary translation of in cantina (another option

would be in the cellar).

There is a slight change in meaning with the translation of a Santo Stefano di

Camastra with from Santo Stefano di Camastra. While the preposition a indicates, that Zirafa

went to the town to order the jar, the preposition from does not indicate a presence in the town at

the time of ordering (he could might as well have sent someone else in his place). It might have

been more accurate to translate with in.

There seem to be some confusion with regards to the description of the jar, which is

bella panciuta e maestosa. This does not mean that it is beautiful as the translation suggests, but

rather beautifully big-bellied. Bella in this context is not an adjective but an adverb.

In the last phrase, abbess is put in quotation marks even though this is not the case

in the original. Maybe the translator was afraid, that the metaphor would not be understood and

therefore wishing to make the figurative sense more explicit to the reader.

The German translation is again freer with respect to both words and tenses:

Zirafa besa einen schnen kleinen Olivenhain in seinem Gut in Primosole. Und da er

sich ausgerechnet hatte, da die fnf alten, emaillierten Tonkrge, die er im Keller

verwahrte, nicht gengen wrden, die neue Ernte zu fassen, hatte er beizeiten in Santo

Mirjam Friediger 2006

6

Stefano di Camastra einen sechsten bestellt: brusthoch, mit majesttisch ausladendem

Bauch, der Pater Prior der anderen.

In German it is possible to put the definite article (der) in front of the name as in Italian (lo),

but the translator has chosen not to do so in the first phrase. Apart from that, the first phrase is a

rewriting of the Italian original, stating that Zirafa possessed a nice small olive garden on his estate

in Primosole. Instead of the olives, the narrator in this translation talks about the olive garden,

which was in fact also implied by the one of the abstracts meanings of giro, but that it is nice

(schn) and small (klein) seems more like an interpretation (schn is obviously translated

from bel, but I consider that adjective meant more in the sense of quantity than the quality

expressed by schn, as does also the English translator with his translation of the construction in

question; fair number). As is done in the English translation, Hinterhuser chooses to speak

explicitly of the farm, but chooses not to mention its name, Le Quote, in this way taking a different

direction than the original (not only aiding the reader as the English translation aspires to do).

In the second phrase, instead of copying the Italian gerund (prevedendo in the

English translation foreseeing), the German version makes use of the pluperfect (ausgerechnet

hatte, which is very common in German and is linguistically more elegant than the hypothetical

gerund ausgerechnend would have been. As the grammatically necessary specification of the

cellar, the text uses the definite article (im = in + dem) as an alternative for the personal pronoun in

the English version (his), but instead of just translating the aveva into hatte, Hinterhuser

chooses a different verb: verwahren (to preserve/to keep). This is probably an aesthetic choice,

since hatte is already used as the auxiliary verb in the pluperfect and it would sound monotonous

to repeat it so soon after.

In the succeeding phrase, the German version leaves out another part of the original:

tutto lolio it just mentions the new harvest (die neue Ernte).

The translation for the preposition a with regards to the ordering of the jar is here

in, which preserves the idea of Zirafa actually going to the town himself and is thus more accurate

than the English translation.

It seems as if also Hinterhuser has misunderstood the description of the jar in the last

phrase. Mit majesttisch ausladendem Bauch means with majestically outstretched belly. In the

translation bella has been left out, and the adjective majestosa has become an adverb

(majesttisch).

The last part of the paragraph has been somewhat altered. The problem of translating

the conditional mood (che fosse) has been avoided by completely leaving out the verb, and the

abbess (a clerical position that does not exist in the protestant part of Germany, where there are no

Mirjam Friediger 2006

7

nuns) has been converted into the Pater Prior (the Prior) of the others (der anderen) without

announcing the quantity of the jars as in the original text.

To conclude this comparison of two different translations (in two different languages) of the first

part of Pirandellos short story (which in my opinion is representative for the translations of the

entire text), I would like to stress the fact, that even though the English version so loyal to the

original seems heavier than the German version which attempts to reproduce the richness of the

language of the author, it satisfies its purpose; that of serving as a linguistic guide for the original

text in a dual-language book. The much freer German translation (which becomes even more so

further on in the text) is able to stand alone and convey to the reader more successfully the sensation

of the brilliant writing style of Pirandello.

Bibliography:

Pirandello, Luigi: La giara. The Oil Jar in Eleven Short Stories. Unidici Novelle. A Dual-

Language Book. Trans. and ed. by Appelbaum, Stanley. Dover Publications, New York, 1994.

pp 92-111.

Pirandello, Luigi: Der lkrug in Feuer ans Stroh. Sizilianische Novellen. Verlag Klaus

Wagenbach, Berlin, 1997. pp 228-239.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Thurneysen 1946.G of Old IrishDocument567 pagesThurneysen 1946.G of Old Irishfinnfolcwalding100% (2)

- Kingdom Interlinear Translation 1969Document595 pagesKingdom Interlinear Translation 1969Calea Creştină100% (4)

- Transposition and Modulation + Other TechniquesDocument12 pagesTransposition and Modulation + Other TechniquesAngel David VillabonaPas encore d'évaluation

- Cartilla Espacio Publico Neiva PDFDocument189 pagesCartilla Espacio Publico Neiva PDFWendy QuevedoPas encore d'évaluation

- PLOSOne Formatting Sample Title Authors AffiliationsDocument1 pagePLOSOne Formatting Sample Title Authors AffiliationsMichiel Angelo Albaladejo PerojaPas encore d'évaluation

- Korean DuolingoDocument45 pagesKorean DuolingoSe Rin100% (1)

- The Idiomatic Translation of The New Testament: Prepublication EditionDocument380 pagesThe Idiomatic Translation of The New Testament: Prepublication Editionharoldpsb100% (1)

- Guide To The Names in The Lord of The RingsDocument23 pagesGuide To The Names in The Lord of The Ringsdragic90100% (3)

- Is Everything Translatable?Document1 pageIs Everything Translatable?AndresPas encore d'évaluation

- Concise Etymological DictionaryDocument674 pagesConcise Etymological Dictionarysakariaxa97% (36)

- Swedish VerbDocument16 pagesSwedish VerbViculescu50% (2)

- Heidegger Introduction To Metaphysics PDFDocument333 pagesHeidegger Introduction To Metaphysics PDFJean-Yves Heurtebise67% (3)

- Bambara Manual 2Document156 pagesBambara Manual 2Francisco José Da Silva100% (2)

- Group A Group B: Speculating SpeculatingDocument1 pageGroup A Group B: Speculating Speculatingleandro lozanoPas encore d'évaluation

- 6th Grade Grammar WorkbookDocument56 pages6th Grade Grammar WorkbookAbdullah Ibn Mubarak80% (5)

- Unit 3 Test Level 1: Vocabulary and GrammarDocument2 pagesUnit 3 Test Level 1: Vocabulary and Grammarrox purdeaPas encore d'évaluation

- Being and Time - Martin HeideggerDocument21 pagesBeing and Time - Martin HeideggerQuinn HegartyPas encore d'évaluation

- The Two German Past Tenses and How To Use ThemDocument3 pagesThe Two German Past Tenses and How To Use ThemGaurav KapoorPas encore d'évaluation

- ئینگلیزی گرامەرDocument10 pagesئینگلیزی گرامەرAsya KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Indirect or Oblique Translation Techniques - Bastia, GabrielDocument4 pagesIndirect or Oblique Translation Techniques - Bastia, GabrielGabriel Bastia GarcíaPas encore d'évaluation

- My Name Is Aram Is A Collection of Short Stories With Topics From The Armenian-CalifornianDocument6 pagesMy Name Is Aram Is A Collection of Short Stories With Topics From The Armenian-CalifornianPerfil InexistentePas encore d'évaluation

- English-German Contrasts - ScriptDocument68 pagesEnglish-German Contrasts - ScriptAlex MunteanuPas encore d'évaluation

- BookletDocument13 pagesBookletapi-106074229Pas encore d'évaluation

- German HSKDocument27 pagesGerman HSKprajktabhaleraoPas encore d'évaluation

- Easy Ways to Enlarge Your German VocabularyD'EverandEasy Ways to Enlarge Your German VocabularyÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (15)

- Malone's Translation StrategiesDocument3 pagesMalone's Translation StrategiesNico Picerno100% (3)

- Aeneid I.227-241 Artful TranslationDocument2 pagesAeneid I.227-241 Artful TranslationChinmay DeshpandePas encore d'évaluation

- False Friend - WikipediaDocument4 pagesFalse Friend - WikipediaRommelBaldagoPas encore d'évaluation

- Names: Suny Suntoro Nonny Cahyani Risma Devi Sulstyani Williatun NurdinDocument19 pagesNames: Suny Suntoro Nonny Cahyani Risma Devi Sulstyani Williatun NurdinSuny AsepPas encore d'évaluation

- Plath Translates RilkeDocument24 pagesPlath Translates RilkeAlexandrePas encore d'évaluation

- Angol Nyelv TörténeteDocument12 pagesAngol Nyelv TörténeteKunajomiPas encore d'évaluation

- Venuti How To Read TranslationDocument4 pagesVenuti How To Read Translationapi-25898869Pas encore d'évaluation

- False FriendDocument7 pagesFalse Friendseanwindow5961Pas encore d'évaluation

- Present Perfect: Passé ComposéDocument4 pagesPresent Perfect: Passé Composéزينه اللاميPas encore d'évaluation

- 65 Vulgar LatinDocument72 pages65 Vulgar LatinAlex Fernandes100% (1)

- B. Kirschbaum - German VerbsDocument242 pagesB. Kirschbaum - German VerbsDavid_BCPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Masculine Feminine Neuter Plural: Nominative Der Die Das DieDocument3 pagesCase Masculine Feminine Neuter Plural: Nominative Der Die Das DieDeni AndiansyahPas encore d'évaluation

- Verbs in SwedishDocument16 pagesVerbs in SwedishMaria TudorPas encore d'évaluation

- Dynamic Equivalence in TranslationDocument1 pageDynamic Equivalence in TranslationAde GumilarPas encore d'évaluation

- Amelioration of Semantics and DemilorationDocument2 pagesAmelioration of Semantics and DemilorationMona SarahPas encore d'évaluation

- Genesis, Critically and Exegetically Expounded, Vol. 1, Dillmann, 1897Document436 pagesGenesis, Critically and Exegetically Expounded, Vol. 1, Dillmann, 1897David BaileyPas encore d'évaluation

- HEGEL Philosophy of Religion 1Document374 pagesHEGEL Philosophy of Religion 1Fer_1984Pas encore d'évaluation

- 00 False Friends Croatian EnglishDocument86 pages00 False Friends Croatian EnglishskhaliquePas encore d'évaluation

- Nautical GermanDocument444 pagesNautical Germansorinn1987100% (2)

- Non Separable Prefixes LanguagesDocument6 pagesNon Separable Prefixes LanguagesLoki97 0Pas encore d'évaluation

- Danish Grammar (W)Document7 pagesDanish Grammar (W)Marcelo A. IngrattaPas encore d'évaluation

- M18. Natural Translation and Re-Creation Translation, and TranscreationDocument20 pagesM18. Natural Translation and Re-Creation Translation, and TranscreationNajma Asum0% (1)

- Wieder Ist Ein Schiff Untergegangen! Russell SchuhDocument6 pagesWieder Ist Ein Schiff Untergegangen! Russell SchuhTim TangPas encore d'évaluation

- Translation Procedures Readings in Translation TheoriesDocument7 pagesTranslation Procedures Readings in Translation TheoriesSorica DianaPas encore d'évaluation

- Old English Vs GermanDocument11 pagesOld English Vs GermanRandall840% (1)

- English Article: Elementary School Teacher Education Univercity of Lampung 2012Document8 pagesEnglish Article: Elementary School Teacher Education Univercity of Lampung 2012Fajar Dwi RohmadPas encore d'évaluation

- Raspunsuri Seminar I TerminologieiDocument5 pagesRaspunsuri Seminar I TerminologieiMissC0RAPas encore d'évaluation

- Word Formation in EsperantoDocument17 pagesWord Formation in EsperantoSceptic GrannyPas encore d'évaluation

- Collins Concise German Dictionary Deutsch-Englisch, English-German (PDFDrive)Document4 128 pagesCollins Concise German Dictionary Deutsch-Englisch, English-German (PDFDrive)mike scottPas encore d'évaluation

- Bauer - Rose Ausländer's American PoetryDocument13 pagesBauer - Rose Ausländer's American PoetrySinae DaseinPas encore d'évaluation

- A Rose by Any Other NameDocument4 pagesA Rose by Any Other NameIleana CosanzeanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Balg, Braune. A Gothic Grammar With Selections For Reading and A Glossary. 1895.Document252 pagesBalg, Braune. A Gothic Grammar With Selections For Reading and A Glossary. 1895.Patrologia Latina, Graeca et Orientalis100% (2)

- Germanforenglish PagenumberDocument91 pagesGermanforenglish PagenumberdenizhanozbeyliPas encore d'évaluation

- Slogan As Form of A Verbal Logo ComprisesDocument2 pagesSlogan As Form of A Verbal Logo ComprisesVlad SochinskyPas encore d'évaluation

- Power Point DavidDocument11 pagesPower Point Davideduvigesror5079Pas encore d'évaluation

- German As A Language of PhilosDocument6 pagesGerman As A Language of PhilosCharles MorrisonPas encore d'évaluation

- Stephen M. Dickey: The "Third Language" in Translations From Bosnian, Croatian and SerbianDocument4 pagesStephen M. Dickey: The "Third Language" in Translations From Bosnian, Croatian and SerbianVictor O. KrausskopfPas encore d'évaluation

- SUSTANTIVOS 1 y PracticasDocument2 pagesSUSTANTIVOS 1 y PracticasMichael GoncaloPas encore d'évaluation

- Multi DEXDocument182 pagesMulti DEXliviu_dot_com5398Pas encore d'évaluation

- Comprehension: in Schools, Libraries and OfficesDocument11 pagesComprehension: in Schools, Libraries and OfficesAndrew OwnelPas encore d'évaluation

- Technical Writing SkillsDocument33 pagesTechnical Writing Skillsapi-3797188Pas encore d'évaluation

- Frequency-Likes and Dislikes by Daniel PérezDocument2 pagesFrequency-Likes and Dislikes by Daniel PérezIsai HernandezPas encore d'évaluation

- Getting Started On Classical Latin PrintableDocument34 pagesGetting Started On Classical Latin PrintableJack BlackPas encore d'évaluation

- TGS 2 Structure - Sheilla RivandaDocument3 pagesTGS 2 Structure - Sheilla RivandaLILISPas encore d'évaluation

- English ErrorsDocument3 pagesEnglish ErrorsBog VPas encore d'évaluation

- English Quiz PDFDocument3 pagesEnglish Quiz PDFUsman KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Eyes Open Level 1 Students Book Sample UnitDocument13 pagesEyes Open Level 1 Students Book Sample UnitBrian Sullivan50% (2)

- Lesson Plan in RelativeDocument4 pagesLesson Plan in RelativeJac FloresPas encore d'évaluation

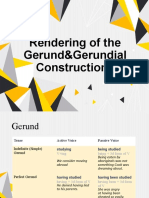

- The Gerundial ConstructionDocument10 pagesThe Gerundial ConstructionАлёнка ПрийдунPas encore d'évaluation

- Imaginative Writing - Lesson 2 Using Noun PhrasesDocument9 pagesImaginative Writing - Lesson 2 Using Noun PhrasesSeval AkyolPas encore d'évaluation

- Compositions - 4th ESODocument11 pagesCompositions - 4th ESOvilacalabuigPas encore d'évaluation

- Verb List Patterns FITDocument4 pagesVerb List Patterns FITJonathan ValdezPas encore d'évaluation

- French 2 WFD10201: Me You Him / Her / One Us You ThemDocument2 pagesFrench 2 WFD10201: Me You Him / Her / One Us You ThemEmyza Amirah100% (1)

- Rules On Adjective and AdverbsDocument2 pagesRules On Adjective and AdverbsAudrey100% (1)

- Passive Voice and Causative Structure 17969Document2 pagesPassive Voice and Causative Structure 17969Darmesta I Ketut67% (3)

- Toki PonaDocument2 pagesToki PonaNicholas FletcherPas encore d'évaluation

- Commas With Complex Sentences PDFDocument2 pagesCommas With Complex Sentences PDFLal Bux SoomroPas encore d'évaluation

- Possessive Adjectives With The Verb To BeDocument3 pagesPossessive Adjectives With The Verb To BePriscila Beatriz Cabrera CabralPas encore d'évaluation

- Techical Institute Private of HealthDocument2 pagesTechical Institute Private of HealthAdilson Barbosa AvbPas encore d'évaluation

- Grade 9 TqsDocument4 pagesGrade 9 TqsAteneo Novy Joy100% (2)