Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Clinical Ass Unstable Hemidynamic

Transféré par

Fetria Melani0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

17 vues9 pagesclinical assessment about hemodynamic

Titre original

clinical ass unstable hemidynamic

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentclinical assessment about hemodynamic

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

17 vues9 pagesClinical Ass Unstable Hemidynamic

Transféré par

Fetria Melaniclinical assessment about hemodynamic

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 9

Clinical Assessment of Hemodynamically Unstable Patients

Jonathan Sevransky, MD, MHS

Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine The J ohns Hopkins University Baltimore MD

Abstract

Purpose of ReviewClinical examination of hemodynamically unstable patients provides timely,

low risk and potentially useful diagnostic and prognostic information. This review will examine the

evidence behind the use of clinical examination findings to drive treatment decisions and predict

outcomes in patients with hemodynamic instability. An additional goal of the review is to place the

use of clinical examination in context of more invasive techniques to diagnose and treat

hemodynamically unstable patients.

Recent FindingsThe development of novel diagnostic tests based on recently developed

technology has focused attention on methods to determine when a test should enter routine clinical

use. The widespread incorporation of pulmonary artery catheterization into clinical practice prior to

formal evaluation of it's to improve outcomes highlights the importance of properly evaluating

diagnostic tests in critically ill patients. Formal evaluation of clinical examination as a diagnostic

test will allow better understanding of its role in the hemodynamic evaluation in the critically ill.

SummaryClinical examination remains an important initial step in the diagnosis and risk

stratification of patients. Despite limitations of current techniques, the availability, low risk and

ability to perform repetitive tests ensure that clinical examination of the hemodynamically unstable

patient will continue to be a useful tool for the intensivist until more useful tests are validated in this

patient population.

Keywords

physical examination; shock; septic shock; critical illness

Introduction

Clinical examination plays a key role in the diagnosis of hemodynamic instability. From the

emergency room to the intensive care unit, the use of physical findings to risk stratify and treat

patients has long been an important part of the clinician's armamentarium. The use of selected

physical examination findings has been validated to replicate the findings of more invasive

methodologies, and to serve as a surrogate marker for short-term treatment efficacy.

This review will cover the use of physical examination findings to guide physician's diagnostic

and treatment decisions in the hemodynamically unstable patient. The risks and benefits of

clinical examination will be compared to more invasive diagnostic testing. The rationale for

use of individual components of the clinical examination including vital signs, toe temperature,

Corresponding Author: J onathan Sevransky, MD, MHS Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine The J ohns Hopkins University

5501 Hopkins Bayview Circle Suite 4B-73 Baltimore MD 21224 Phone: (410) 550-0546 Fax: (410) 550-2612 jsevran1@@jhmi.edu.

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this

early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is

published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content,

and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

NIH Public Access

Author Manuscript

Curr Opin Crit Care. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2010 J une 1.

Published in final edited form as:

Curr Opin Crit Care. 2009 June ; 15(3): 234238. doi:10.1097/MCC.0b013e32832b70e5.

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

toe-ambient temperature gradient and capillary refill time will be discussed. In addition, this

manuscript will describe key concepts regarding when to incorporate a diagnostic test into

routine clinical practice.

Development of Clinical Assessment in the Triaging of Critically Ill Patients

Beecher and colleagues proposed the use of capillary refill time to diagnose the presence of

shock in injured patients. In 1947, he categorized patients as having normal, definite slowing

and very sluggish capillary refill time (CRT), and correlated these findings with the presence

and severity of shock in patients(1). This discrete classification of CRT was more useful than

pulse, or systolic blood pressure in the classification of patients with shock(1).

Initial trauma scores(2) have also included the presence of capillary refill time as part of a

scoring index to predict the need for emergency surgical evaluation(3). Other clinical

examination techniques used as diagnostic tests of hemodynamic instability in a broad range

of critically ill patients include urinary output, mental status, temperature change, and blood

pressure. These measurements have been included in severity of illness scoring systems,

consensus guidelines for the treatment of the critically ill, and in protocols for randomized

clinical trials.

Clinical Examination as a Diagnostic Test in the Critically Ill

Diagnostic tests are used to detect the presence of disease in patients. They can therefore be

used to classify patients with a disease (or syndrome), to follow a patient's response to therapy,

to risk stratify patients, to identify asymptomatic patients with disease, and to rule out disease.

Clinical examination in the critically ill is primarily used for the first three purposes: for

example to determine whether the patient has hemodynamic instability, to determine whether

the patient is responding to therapy and to stratify risk. A new diagnostic test for the critically

ill should enter general use (or remain in use) if the test assists a clinician in answering one of

the questions listed above(4).

The use of the clinical exam can therefore be evaluated as a diagnostic test. When a clinician

measures the systolic blood pressure or capillary refill time the measurements taken should be

precise, accurate, and provide the clinician additional information about whether a specific

disease or syndrome is present. If clinical examination fits the criteria of a diagnostic test, it

should, for example, improve the ability of the clinician to make the diagnosis of hemodynamic

instability or shock(4). Some tests are also useful as an umpire test when there is diagnostic

uncertainty or divergence between different tests. (4). Recent rules have been created to guide

the analysis of a proposed diagnostic test(5). It An additional criteria for some diagnostic tests

is whether the tests results are correlated with a patient's outcome.(6)

Relative Merits of Clinical Assessment

Clinical assessment provides a number of advantages over the use of invasive methods to assess

severity of illness and adequacy of the initial resuscitation of the hemodynamically unstable

patient. Clinical assessment methods are readily available and can be performed without the

use of additional specialized equipment. Several types of clinical assessment including change

in temperature and mean arterial pressure have been validated to predict mortality in patients

with critical illness in different patient populations. In addition, there is evidence that response

to therapy in hemodynamically unstable patients may predicted by changes in clinical exam.

Further, clinical assessment is low risk and can be repeated as often as necessary

Clinical examination has some obvious limitations. The methodology used for common types

of clinical assessment may vary between clinicians. One such example is the use of capillary

Sevransky Page 2

Curr Opin Crit Care. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2010 J une 1.

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

refill time (CRT), where either pulp pressure or fingernail pressure may be used for

determination of the capillary refill time. CRT measurement may have substantial inter-

observer variability. Some components of the clinical exam may lack accuracy; a non invasive

cuff blood pressure may not accurately reflect intra-arterial blood pressures in patients with

shock(7). Further, clinical examination often will not provide additional information about the

etiology of a patient's hemodynamic instability. Finally, some measures, including CRT, while

commonly used, have not been validated using modern statistical methods to predict outcome

in patients. Table 1 lists the advantages and disadvantages of using clinical assessment to assess

hemodynamic instability in patients.

Comparison of clinical exam versus invasive methodologies to assess

hemodynamically unstable patients

While clinical examination is frequently limited by issues of validation and inter-observer

variability, it may be useful to compare the use of clinical examination versus more

sophisticated monitoring devices to assess critically ill patients. Many of the limitations of

clinical examination are shared with more invasive diagnostic testing. For example, the use of

the pulmonary artery catheter has led to concerns about intra-observer variability in readings,

inability to use the monitor to improve outcomes, and failure of the monitor to predict response

to therapy(8). While there are many novel methods to measure cardiac output and filling

pressure, none of these novel techniques have yet been shown to improve patient outcomes

when used in critically ill patients. Table 2 compares the risks and benefits of clinical

examination versus invasive diagnostic testing in hemodynamically unstable patients.

Methods of Clinical Assessment of Hemodynamic Instability

Vital signs and surrogates of organ specific perfusion such as capillary refill time and urine

output are the most commonly used clinical examination methods to evaluate hemodynamic

instability. In the sections below, the evidence supporting the use of these techniques as a

diagnostic test for hemodynamic instability will be reviewed.

Vital signs

Vital signs are often the first method of clinical assessment in the evaluation of whether a

patient has hemodynamic instability. Vital signs are commonly used for triage decisions,

activation of medical emergency teams, and as a component of severity of illness scoring

systems. However, individual vital signs often will not substantially alter the pretest probability

of a patient having a specific diagnosis such as shock. A short discussion of individual vital

signs can be found below

Pulse

Alterations in pulse may provide a first indication that a patient is developing hemodynamic

instability. While many factors may influence the pulse rate, including fever, exercise,

medications, and thyroid hormone status, a high pulse rate is often a sign of high levels of

endogenous catecholamines, blood loss or dehydration. Studies of normal volunteers

undergoing phlebotomy and acutely ill patients suggest that the change in pulse related to

postural changes may be a useful marker for hypovolemia (9) In addition, a high or low pulse

rate has been used as a criteria for activation of a medical emergency team (10). However, the

presence of a high or low pulse rate is neither sensitive nor specific for the diagnosis of

hemodynamic instability.

Sevransky Page 3

Curr Opin Crit Care. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2010 J une 1.

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

Respiratory rate

Respiratory rates have been included in most severity of illness scoring systems, are a

diagnostic criteria for acute respiratory failure, and have also been incorporated into the criteria

for initiating a medical emergency team. Although respiratory rates may provide useful

information about the severity of illness, they lack adequate specificity or sensitivity to serve

as a stand-alone diagnostic test for hemodynamic instability. The change in respiratory rates

may be more useful as a marker of response to therapy.

Blood Pressure (Mean Arterial Pressure)

Adequate blood pressure is necessary to maintain appropriate perfusion to organs that

autoregulate blood flow such as the brain and kidney. It is therefore reasonable to consider

blood pressure or mean arterial pressure (MAP) as appropriate indicators of critical illness or

clinical instability. A systolic blood pressure <90 mm hg or decrease in systolic blood pressure

>40 mm hg are diagnostic criteria for severe sepsis and septic shock(11). In addition,

orthostatic blood pressure changes may be a useful marker of hypovolemia or blood loss (9).

It is important to note that non- invasively measured blood pressure may not accurately reflect

intra-arterial pressures(7).

MAP and length of time a patient's MAP is <65 mm hg are independent predictors of mortality

in patients with septic shock.(12) However, a treatment that increased blood pressure increased

mortality rates in patients with septic shock(13), and the target MAP used in clinical trials

varies widely(14).

Temperature

Extremes of temperature are highly suggestive of clinical instability, and temperature is one

of the components of most severity of illness scoring systems. However, temperature is not a

sensitive indicator of hemodynamic instability, and medications and exposure, in addition to

severe sepsis may cause hyperthermia. In addition to core temperature, information on skin

and extremity temperatures have been correlated with patient outcomes. Kaplan and colleagues

examined 264 consecutive surgical ICU patients to determine whether a dichotomized

determination of skin temperature was able to stratify patients into high or low cardiac outputs.

Those patients with warm extremities had higher cardiac outputs (8.2 versus 5.3) and higher

venous oxygen saturations that did those with cool extremities. Those patients who had warm

versus cold extremities did not have differences in pulse, systolic or diastolic blood pressure,

or paO2(15). In 100 patients with signs of shock, J oly and Weil showed that toe temperature

was correlated with cardiac index at 3 hours of admission; other measurements of temperature,

including toe- ambient temperature gradient, rectal or finger temperature, were less well

correlated with cardiac index compared with toe temperature(16). In 15 patients with shock,

toe temperature was correlated with cardiac index in cardiogenic but not septic shock(17).

Given the relatively small number of patients enrolled and the divergent findings of these trials,

skin or toe temperature does not provide adequate sensitivity or specificity to be a stand-alone

marker of clinical instability.

Toe- Temperature Gradient

Since toe or rectal temperature measurement may be affected by ambient temperature, several

authors have proposed the use of a temperature gradient to determine adequacy of circulation.

As noted above, J oly and Weil showed that the toe- ambient temperature gradient does not

correlate with cardiac output or index, and is a less useful measure than toe temperature alone

(16) In a larger series of 71 patients, Hening and colleagues compared toe temperature with

toe-ambient temperature gradient, cardiac index, lactate, and MAP as a predictor of mortality

Sevransky Page 4

Curr Opin Crit Care. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2010 J une 1.

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

at during patients ICU course(18). Using jackknife analysis, toe temperature and toe- ambient

temperature difference were better at discriminating between survivors or non survivors than

were MAP, lactate, or cardiac index after admission to the ICU.

Clinical Surrogates of Organ Perfusion

Urine output and capillary refill time are commonly used clinical surrogates of organ perfusion.

Their utility as diagnostic tests for hemodynamic instability will be discussed below

Urine Output

Oliguria is one of the signs of organ-specific hypoperfusion suggestive of inadequate renal

perfusion or cardiac output. It is a useful tool to evaluate whether additional volume challenges

may improve cardiac output, and has been incorporated as a marker of improved perfusion in

many clinical trials. Since oliguria may have causes other than renal hypoperfusion, it may not

be a specific marker of hemodynamic instability, but oliguria can be used as a marker of adverse

outcomes and can assist with risk stratification. Recent consensus recommendations have

recommended a treatment goal of 0.5ml/kg/hour urine output of a surrogate treatment endpoint

in patients with severe sepsis. (19) While this treatment goal is commonly used in clinical

practice and clinical trials, it has not yet been validated against more invasive diagnostic tests

Capillary refill time

Capillary refill time (CRT) is frequently used to assess the degree of instability in patients

presenting to the emergency room or ICU. Since the original description by Beecher and

colleagues, CRT has been incorporated into clinical practice, severity of illness scoring systems

and clinical trial design. CRT is commonly measured at either the fingernail bed or the pulp

of a finger, and the time for the return of normal coloration after temporary occlusion is

measured.

CRT with a cutoff of >6 seconds has been shown to be a sensitive measure of hypovolemia

in children. (20). However, age, gender, and ambient temperature have all been shown to affect

the measure of CRT in normal volunteers, and the presence of a CRT >2 or 3 seconds was not

predictive of blood loss in phlebotomized volunteers(9). In addition, the CRT has been shown

to have poor intra-observer agreement when a cutoff a two seconds was used in adult emergency

room patients(21)(21).

Capillary refill time, in conjunction with urine output and cardiac index, was used as part of a

treatment algorithm in a study of liberal versus conservative fluid strategies in 1000 patients

with acute lung injury(22). Work is underway to validate the utility of CRT in these patients

as a marker of filling pressures (Todd Rice, personal communication). In addition, a recent

study using CRT and a subjective measure of peripheral perfusion found that resuscitated

critically ill patients with either CRT >4.5 seconds or cool extremities (to an examiners hands),

or both, were more likely to have an elevated lactate or an increase in Sequential Organ Failure

Assessment Scores (SOFA) over the first 48 hours of ICU admission compared with those

patients who had neither(23). Of note, these measurements were made within the first 24 hours

of ICU admission after the patient had been resuscitated to a MAP >65 without requiring

changes in vasopressor dosing for >2hours. (23)

Conclusion

Clinical examination allows for rapid and repeated assessment of a critically ill patient. In

conjunction with patient's history and diagnostic testing, clinical examination provides

additional useful information that may increase the likelihood of making a proper diagnosis.

Sevransky Page 5

Curr Opin Crit Care. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2010 J une 1.

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

Limitations of clinical examination as a diagnostic test of hemodynamic instability include

lack of validation when used as a diagnostic test or marker of treatment efficacy or outcome.

It is likely that clinical examination will remain an important part of the clinician's

armamentarium until better diagnostic tests are available. Clinical examination should be one

of the benchmarks against which novel diagnostic tests in the hemodynamically unstable

patient are compared.

Acknowledgments

Dr Sevransky is supported by NIH grant by K-23 GMO7-1399

References

1. Beecher HK, Simeone FA, Burnett CH, et al. The internal state of the severely wounded man on entry

to the most forward hospital. Surgery 1947;22:672681. [PubMed: 20266131]

2. Champion HR, Sacco WJ , Hannan DS, et al. Assessment of injury severity: The triage index. Crit Care

Med 1980;8:201208. [PubMed: 7357873]

3. Champion HR, Sacco WJ , Carnazzo AJ , et al. Trauma score. Crit Care Med 1981;9:672676. [PubMed:

7273818]

4. Glasziou P, Irwig L, Deeks J J . When should a new test become the current reference standard? Ann

Intern Med 2008;149:816822. [PubMed: 19047029] A useful summary that describes methods to

evaluate the utility of novel diagnostic tests..

5. Bossuyt PM, Reitsma J B, Bruns DE, et al. Towards complete and accurate reporting of studies of

diagnostic accuracy: The STARD initiative. Ann Intern Med 2003;138:4044. [PubMed: 12513043]

6. Sonke GS, Verbeek ALM, Kiemeney LALM. A philosophical perspective supports the need for patient-

outcome studies in diagnostic test evaluation. J ournal of Clinical Epidemiology 2009;62:5861.

[PubMed: 18619792] An opinion piece that suggests that clinical outcomes are the appropriate

marker to evaluate novel diagnostic tests

7. Cohn J N. Blood pressure measurement in shock. mechanism of inaccuracy in ausculatory and palpatory

methods. J AMA 1967;199:118122. [PubMed: 5336422]

8. Rubenfeld GD, McNamara-Aslin E, Rubinson L. The pulmonary artery catheter, 1967 2007: Rest in

peace? J AMA 2007;298:458461. [PubMed: 17652302]

9. McGee S, Abernethy WB 3rd, Simel DL. The rational clinical examination. is this patient hypovolemic?

J AMA 1999;281:10221029. [PubMed: 10086438]

10. Hillman K, Chen J , Cretikos M, et al. Introduction of the medical emergency team (MET) system: A

cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2005;365:20912097. [PubMed: 15964445]

11. Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB, et al. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the

use of innovative therapies in sepsis. the ACCP/SCCM consensus conference committee. american

college of chest Physicians/Society of critical care medicine. Chest 1992;101:16441655. [PubMed:

1303622]

12. Varpula M, Tallgren M, Saukkonen K, et al. Hemodynamic variables related to outcome in septic

shock. Intensive Care Med 2005;31:10661071. [PubMed: 15973520]

13. Lopez A, Lorente J A, Steingrub J , et al. Multiple-center, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-

blind study of the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor 546C88: Effect on survival in patients with septic

shock. Crit Care Med 2004;32:2130. [PubMed: 14707556]

14. Sevransky J E, Nour S, Susla GM, et al. Hemodynamic goals in randomized clinical trials in patients

with sepsis: A systematic review of the literature. Crit Care 2007;11:R67. [PubMed: 17584921]

15. Kaplan LJ , McPartland K, Santora TA, et al. Start with a subjective assessment of skin temperature

to identify hypoperfusion in intensive care unit patients. J Trauma 2001;50:6207. discussion 627

8. [PubMed: 11303155]

16. J oly H, Weil M. Temperature of the great toe as an indication of the severity of shock. Circulation

1969;39:1318. [PubMed: 5782801]

17. Vincent J L, Moraine J J , van der Linden P. Toe temperature versus transcutaneous oxygen tension

monitoring during acute circulatory failure. Intensive Care Med 1988;14:6468. [PubMed: 3343431]

Sevransky Page 6

Curr Opin Crit Care. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2010 J une 1.

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

18. Henning RJ , Wiener F, Valdes S, et al. Measurement of toe temperature for assessing the severity of

acute circulatory failure. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1979;149:17. [PubMed: 451819]

19. Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Carlet J M, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: International guidelines for

management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2008. Crit Care Med 2008;36:296327. [PubMed:

18158437] Consensus guidelines on the management of patients with severe sepsis and septic

shock. Many of the recommendations on the use of clinical examination in the hemodynamically

unstable patient are summarized here.

20. Steiner MJ , DeWalt DA, Byerley J S. Is this child dehydrated? J AMA 2004;291:27462754. [PubMed:

15187057]

21. Anderson B, Kelly A, Kerr D, et al. Capillary refill time in adults has poor intraobsever agreement.

Hong Kong J ournal of Emergency Medicine 2008;15:714.

22. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Clinical

Trials Network. Wiedemann HP, Wheeler AP, et al. Comparison of two fluid-management strategies

in acute lung injury. N Engl J Med 2006;354:25642575. [PubMed: 16714767]

23. Lima L, J ansen TC, van Bommel J , Ince C, et al. The prognostic value of the subjective assessment

of peripheral perfusion in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 2009;37:9348. [PubMed: 19237899]

An observational trial to evaluate the subjective assessment of peripheral perfusion in patients that

have undergone initial resuscitation

Sevransky Page 7

Curr Opin Crit Care. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2010 J une 1.

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

Sevransky Page 8

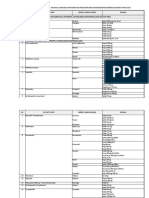

Table 1

Benefits and Drawbacks Of Clinical Examination For Risk Stratification

Benefits Drawbacks

Immediate Information Available Cannot Distinguish Between Forms of Shock

Some Measures Validated for Risk Stratification Many Measures Not Validated for Risk

Stratification

Repeated Measures Feasible Can Tailor Therapy to Results Less emphasis placed on teaching clinical skills in

many medical schools

Measurements Low Risk

Skills are easily taught- do not require technical skills

Curr Opin Crit Care. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2010 J une 1.

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

Sevransky Page 9

Table 2

Comparison of Clinical Examination Versus Invasive Diagnostic Testing For Diagnosis and Treatment of Clinical

Instability

Clinical Examination Invasive Diagnostic Testing

Immediate Information Available Requires Procedure Prior to Results

Some Measures Validated for Risk Stratification Some Measures Validated for Risk Stratification

Repeated Measures Feasible Can Tailor Therapy to

Results, but primarily unproven as a method to titrate

therapy

Repeated Measures Feasible Can Tailor Therapy to

Results, but primarily unproven as a method to titrate

therapy

Measurements Low Risk Measurements Higher Risk

Cannot distinguish between forms of shock Can distinguish between many forms of shock

Curr Opin Crit Care. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2010 J une 1.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Hemodynamic Management Pocket Card PDFDocument8 pagesHemodynamic Management Pocket Card PDFjenn1722Pas encore d'évaluation

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Endocrine SystemDocument14 pagesThe Endocrine SystemCrisanto Christopher Bidan Sanares100% (3)

- Mount Sinai Obstetrics and Ginecology 2020Document414 pagesMount Sinai Obstetrics and Ginecology 2020David Bonnett100% (1)

- Nutrition For AdultDocument60 pagesNutrition For AdultFetria MelaniPas encore d'évaluation

- AntioxidantDocument22 pagesAntioxidantFetria MelaniPas encore d'évaluation

- How to Lower Your LDL CholesterolDocument7 pagesHow to Lower Your LDL CholesterolFetria MelaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Antioxidants and Stress Tolerance 2010Document22 pagesAntioxidants and Stress Tolerance 2010AKICA023Pas encore d'évaluation

- Olahraga Kekuatan OtotDocument8 pagesOlahraga Kekuatan OtotFetria MelaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Cerebral Blood FlowDocument37 pagesCerebral Blood FlowFetria MelaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Stroke Imaging AlgorithmDocument8 pagesStroke Imaging AlgorithmFetria MelaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Dash Diet PamphletDocument64 pagesDash Diet PamphletbohnjucurPas encore d'évaluation

- StrokeDocument2 pagesStrokeFetria MelaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Malnutrition in Stroke PatientDocument8 pagesMalnutrition in Stroke PatientFetria MelaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Stroke PatofDocument22 pagesStroke PatofderiPas encore d'évaluation

- Dysphagia Nutrition Hydration in Stroke 2012Document8 pagesDysphagia Nutrition Hydration in Stroke 2012Fetria MelaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Fisiologi Kulit MenuaDocument1 pageFisiologi Kulit MenuaFetria MelaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Immunity and Aging1742-4933!5!15Document10 pagesImmunity and Aging1742-4933!5!15Fetria MelaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Patient EducationDocument18 pagesPatient EducationFetria MelaniPas encore d'évaluation

- DehydrationDocument10 pagesDehydrationEko SetiawanPas encore d'évaluation

- FitokimiaDocument0 pageFitokimiaFetria MelaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Muscle Atrophy DialysisDocument8 pagesMuscle Atrophy DialysisFetria MelaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Clinical NutritionDocument7 pagesClinical NutritionFetria MelaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Living With Uc Brochure FinalDocument19 pagesLiving With Uc Brochure FinalJon Wafa AzwarPas encore d'évaluation

- BUN Creatinin RatioDocument5 pagesBUN Creatinin RatioFetria MelaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Klasifikasi WagnerDocument8 pagesKlasifikasi WagnerNina AmeliaPas encore d'évaluation

- Full Liquid DietDocument1 pageFull Liquid DietFetria MelaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Mna Short FormDocument1 pageMna Short FormFetria MelaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Nutrisi Ulseratif KolitisDocument1 pageNutrisi Ulseratif KolitisFetria MelaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Algorithm Pyloric StenosisDocument15 pagesAlgorithm Pyloric StenosisFetria MelaniPas encore d'évaluation

- The Anatomy of A Great Poster: Richard Gerkin, M.D. Bridget Stiegler, D.ODocument31 pagesThe Anatomy of A Great Poster: Richard Gerkin, M.D. Bridget Stiegler, D.OFetria MelaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Modul 0 Introduction To Clinical Nutrition PDFDocument7 pagesModul 0 Introduction To Clinical Nutrition PDFEko SetiawanPas encore d'évaluation

- Clear Liquid DietDocument3 pagesClear Liquid DietFetria Melani100% (1)

- Rare Obstetric Emergency: Amniotic Fluid EmbolismDocument5 pagesRare Obstetric Emergency: Amniotic Fluid EmbolismDenim Embalzado MaghanoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Immunization Case-Based Register: DHIS2 Tracker Data Model in PracticeDocument11 pagesImmunization Case-Based Register: DHIS2 Tracker Data Model in PracticeGerald ThomasPas encore d'évaluation

- Cutaneous Leishmania: Dr. Vijayakumar Unki Asst Professor VCGDocument16 pagesCutaneous Leishmania: Dr. Vijayakumar Unki Asst Professor VCGLohith MCPas encore d'évaluation

- 10.1007@s11604 019 00901 8Document15 pages10.1007@s11604 019 00901 8sayed hossein hashemiPas encore d'évaluation

- Psychosis 2020Document10 pagesPsychosis 2020moebius70Pas encore d'évaluation

- Annotated Bibliography On Internet AddictionDocument4 pagesAnnotated Bibliography On Internet AddictionJanet Martel100% (3)

- Lesson 3 BloodDocument50 pagesLesson 3 BloodJulius Memeg PanayoPas encore d'évaluation

- Ajab SinghDocument2 pagesAjab SinghapPas encore d'évaluation

- Brain Tumor Segmentation and Detection Using Nueral NetworksDocument9 pagesBrain Tumor Segmentation and Detection Using Nueral Networksjoshi manoharPas encore d'évaluation

- Early Psychosis DeclarationDocument6 pagesEarly Psychosis Declarationverghese17Pas encore d'évaluation

- Acute Appendicitis Made EasyDocument8 pagesAcute Appendicitis Made EasyTakpire DrMadhukarPas encore d'évaluation

- Standar Obat Nayaka Siloam Okt 2019 Receive 30092019Document33 pagesStandar Obat Nayaka Siloam Okt 2019 Receive 30092019Retno Agusti WulandariPas encore d'évaluation

- 1ST Summative Test-Health ViDocument4 pages1ST Summative Test-Health ViDell Nebril SalaPas encore d'évaluation

- Saint Paul University Philippines: School of Nursing and Allied Health Sciences College of NursingDocument4 pagesSaint Paul University Philippines: School of Nursing and Allied Health Sciences College of NursingimnasPas encore d'évaluation

- Revised Jones Criteria JurdingDocument41 pagesRevised Jones Criteria JurdingddantoniusgmailPas encore d'évaluation

- Using Long-Acting Injectable Antipsychotics as First-Line Treatment for Early-Episode SchizophreniaDocument3 pagesUsing Long-Acting Injectable Antipsychotics as First-Line Treatment for Early-Episode SchizophreniaFan TomasPas encore d'évaluation

- Starting an IV: Preparation, Equipment, Venipuncture StepsDocument10 pagesStarting an IV: Preparation, Equipment, Venipuncture StepsNurse NotesPas encore d'évaluation

- Guidelines For The Surgical Treatment of Esophageal Achalasia PDFDocument24 pagesGuidelines For The Surgical Treatment of Esophageal Achalasia PDFInomy ClaudiaPas encore d'évaluation

- ComprehensiveDocument4 pagesComprehensiveDeekshitha Turaka0% (1)

- ROM Machine TranslationDocument2 pagesROM Machine TranslationResha Noviane PutriPas encore d'évaluation

- Guideline - Anesthesia - RodentsDocument2 pagesGuideline - Anesthesia - Rodentsdoja catPas encore d'évaluation

- Edema Por Destete Teboul - MonnetDocument8 pagesEdema Por Destete Teboul - MonnetLuis Felipe Villamarín GranjaPas encore d'évaluation

- Lifestyle DiseasesDocument44 pagesLifestyle Diseaseskyro draxPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Pre Ovarian CystDocument56 pagesCase Pre Ovarian Cystthesa1201Pas encore d'évaluation

- OmronDocument19 pagesOmrondekifps9893Pas encore d'évaluation

- Radiologic Features of Lung Lymphoma: A Review of Imaging PatternsDocument42 pagesRadiologic Features of Lung Lymphoma: A Review of Imaging PatternsMoch NizamPas encore d'évaluation

- Blood Collection and Blood Smear PreparationDocument6 pagesBlood Collection and Blood Smear PreparationSol Kizziah MeiPas encore d'évaluation