Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Attorney Makes The Case For A Civil Gideon Policy - 2014-Fall-California Courts Monitor - California Supreme Court Tani Cantil-Sakauye - 3rd District Court of Appeal Vance Raye

Transféré par

California Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Attorney Makes The Case For A Civil Gideon Policy - 2014-Fall-California Courts Monitor - California Supreme Court Tani Cantil-Sakauye - 3rd District Court of Appeal Vance Raye

Transféré par

California Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Monitored

inside:

James Preston Allen: When

court administrators close the

local courthouse, they remove

part of the communitys heart.

The longtime Los Angeles

journalist takes a look close

to home. PAGE 3

Time for a civil Gideon?:

A lawyer makes the case that

the guarantee of a government-

provided attorney, already set

for criminal cases, should be

extended to certain civil issues

especially when human

needs like housing are

concerned. PAGE 3

Toward a clients

bill of rights: Its not

exactly thou shalt not steal,

but a California attorney helps

draft ten commandments for

anyone hoping to get a fair

shake from their contingency

lawsuit. Actually, hes accepting

a challenge from Courts Moni-

tor Publisher Sara Corcoran

Warner. PAGE 4

Confessions of a jury-duty

scofaw: Consolidating court-

houses, and the resulting travel

times, have impacted the states jury

pool. With travel hardships the latest

easy out for potential jurors, some

who are called are less than zealous

about being chosen. You can count

best-selling author Dan Dunn among

that group. PAGE 6

The new normal?: The chief

justice wanted a billion dollars to

bring Golden State courts up to

standards. She did not get it. Instead,

there is a three-year plan to make

things better but nobody is talking

about opening those closed courts or

returning to pre-cut staff levels. We take

a look at the new normal. PAGE 10

The best court movies:

A legendary West L.A. movie critic,

Nicky Hernandez, comes out of

retirement to list his favorite court-

focused movies. Yeah, you probably

got number one right, but good

luck with the down-list selections.

PAGE 12

Editors note: This Ted Rall illustrated column was

originally published in The Los Angeles Times and

is reproduced here under special agreement with the

artist. For more on the ongoing crisis, see PAGE 6. For

more political commentary from Ted Rall, visit rall.com.

Equal justice under the law. Thats the promise

American courts make to plaintiffs and defendants

alike. But year after year of budget austerity has

forced Californias court system to slash its services

so deeply that it has made a mockery of that sacred

pledge.

Maura Dolan reports that recession-driven cut-

backs in Californias huge court system have produced

long lines and short tempers at courthouses through-

out the state. Civil cases are facing growing delays in

getting to trial, and court closures have forced resi-

dents in some counties to drive several hours for an

appearance.

Backups in the courts are affecting Californians

love lives: Clerks in Contra Costa County said they

have received complaints from people who divorced

and wanted to remarry but couldnt because clerks

had not yet processed the paperwork for judges sig-

natures.

Every cloud has a silver lining. Because so many

courthouses have closed, some Californians are auto-

matically getting exempted from jury duty: In San

Bernardino County, the Superior Court has stopped

summoning jurors from Needles, making the guaran-

tee of a jury of ones peers elusive. Because of court

closures in the High Desert, a trip to court from Nee-

dles can take some residents 3-1/2 hours.

But its still a damned dark cloud.

We are really on the borderline of a constitutional

crisis, Marsha Slough, San Bernardino Countys pre-

siding judge says. We have victims who want to give

up because they dont want to testify in criminal trials

because of the driving distances and costs.

Whether youre ghting a trafc ticket, fending off

a neighbor over a property dispute or waiting for a

divorce, everyone winds up in court sooner rather than

later. And contrary to what conservatives keep saying,

starving government institutions of cash doesnt make

... borderline of a constitutional crisis

Your daily ration of civil justice rationing

CALIFORNIA COURTS MONITOR

www.CaliforniaCourtsMonitor.com @cacourtsmonitor

ASBESTOS REPORTING PROJECT: The nations longest-running personal injury tort system is undergoing constant change, and that is

reected in California and courts across the country. The California Courts Monitor is joining with its sister website, the National Courts Monitor,

and other partners including Washington, D.C.-based Paul Johnson Films to create the Asbestos Reporting Project. The in-depth series begins over

the summer and for more information, visit our website or follow us on Twitter. SERIES BEGINS PAGE 9.

Special Print Edition Los Angeles, California August/September 2014

11

BY TED RALL

SPECIAL TO THE COURTS MONITOR

see CRISIS page 6

Follow us on Twitter @cacourtsmonitor CALIFORNIA COURTS MONITOR, A Special Report UPDATE Page 3

Tino, the Cambodian-Texan bar owner of

Crimsin, stood across the street as the state main-

tenance workers unbolted the letters which once

read, San Pedro Superior Court. It was just two

Latino guys with a ladder and some tools. By the

time we noticed what was occurring, the letters

were half gone, leaving only erior court an omi-

nous and foreboding reference to the demise of

100 years of local justice in this southern part of

Los Angeles County.

Can we at least

have a few letters

from the sign as

memorabilia? we

asked.

No, was the

answer. They belong

to the State of Cali-

fornia. The work-

men looked over

their shoulders at us

like we were either

drunk or crazy, con-

tinuing their work.

Well of course they

do but who would

miss a few letters?

We the people of Sixth Street might like to have

some proof of what once was here. The workers

continued pulling the letters off the building until

they were all gone.

It was back in 1909 that the Los Angeles Con-

solidation Committee promised the residents of

the Harbor area a police court as part of the deal

to annex to the city of Los Angeles and there has

been a court here in some form or another until

June of 2013.

Here, however, are the sad facts the San Pedro

Courthouse along with the Avalon Court on Cata-

lina Island generated enough revenue in terms of

nes and fees to more than cover their own costs

of operating both courts ($715 million in scal

year 2011-12). The bulk of that money (54%)

goes to the state general revenue fund, then the

county (37%), and lastly the city (6%). The Supe-

rior Courts retains only single-digit amounts (1%)

of the funds it generates. And, this formula is true

throughout the state, which is why the courts

are completely underfunded. They retain little of

what they generate in revenues and then expect

to get it back from the legislature. Its kind of like

the taxes we pay for schools that go to the state

and then get redistributed back to the districts.

The statewide impact on the courts looks like

this:

Court closures have deprived more than 2

million Californians of access to justice in their

local communities.

51 court houses and a total of 205 court rooms

have been closed.

30 courts have had to reduce hours at public

service counters.

15 courts have had to institute limited court

service days (where the majority of court rooms

and clerks ofces are closed).

Nearly 4,000 court staff have lost their jobs.

Many courts are leaving vacant positions unlled,

and some courts continue to furlough employees.

And, on top of this civil cases no longer have court

reporters to record their proceedings.

This elimination of access to justice falls more

heavily on the poor and minority communities

than on those who can afford to wait for justice or

who dont have to depend on public transit to get

to court 30 miles from home at 8:30 in the morn-

ing.

Recently, in the Legal Newsline, Richard

Burdge, the president of the Los Angeles County

Bar Association and owner of The Burdge Law

Firm in Los Angeles, said, Theyre cutting into

the bone, not just the fat of the court system.

The Legal Newsline article goes on to state,

According to the Judicial Council of California, in

the past ve years, the court systems budget was

cut by more than $1 billion. In the same period, the

court system lost about 65 percent of the funds it

receives from the states general fund. More than

114 court rooms and 22 court houses were closed,

and 30 courts have reduced their hours.

To put this in perspective, the Superior Court of

Los Angeles County maintains the states largest

court system and it continues to experience some

of the deepest funding cuts. And recently, the

Superior Court announced its plan to eliminate

511 more positions! As a result, 177 people lost

their jobs and 139 people were demoted to pre-

viously held positions. An additional 223 people

were reassigned to new locations.

This, of course, can be explained by the States

post-2008 budget crisis or the fact that the end

result of Proposition 220, an initiative approved

Cutting into the bone of the court system

BY JAMES PRESTON ALLEN

SPECIAL TO THE COURTS MONITOR

you have the right to an attorney. If you

cannot afford an attorney, one will be appointed

for you

Most Americans are more than familiar with

these words, part of

the Miranda rights

we have heard time

and time again on TV

and in the movies; if

you cannot afford

your own criminal

defense attorney, the

state will provide

you one, a public

defender.

However, criminal

courts are not the

only places where

people, including

poor people, will

interact with the

legal system against

their will, and fre-

quently not even the most life-altering. Decisions

made in civil courts involving housing, suste-

nance, medical benets, or child custody issues

can have as great or, frequently, greater long-term

consequences in peoples lives than many crimi-

nal verdicts.

When someone is facing eviction, or the possi-

bility of losing need-based government assistance,

the odds of them being able to afford their own

attorney are slim; individuals in these proceed-

ings frequently go in on their own, unaware of the

substance of the law or the courts procedures.

Over the last decade, there has been a growing

movement to create a right to counsel in certain

civil cases, an idea usually called civil Gideon.

The name comes from Gideon v. Wainwright, the

1963 case that established that the Sixth Amend-

ments right to counsel meant that, in criminal

felony cases in both state and federal courts, not

only must the court allow the defendant to have a

lawyer, but indigent defendants must be provided

representation.

Prior to that, the positive right to counsel had

been limited to federal cases, or in state capital

trials. Following Gideon, the right to counsel was

extended to misdemeanor cases that might result

in jail time, to civil juvenile proceedings, and to

prisoners in civil proceedings to transfer them

from a prison to a mental institution. Unfortu-

nately, the expansion of the right to counsel was

halted in 1981, when the Lassiter decision found

there was no right to counsel in proceedings for

termination of parental rights and created a pre-

sumption that there is only a right to counsel

when an indigent litigant risks being deprived of

his or her physical liberty.

The idea of a guarantee of right to counsel

in certain civil proceedings, through litigation

and legislation, has traction in several state bar

associations, the ABA, among legal scholars and

judges who see the consequences of unrepre-

sented litigants, and some state legislators.

So, why do we need civil Gideon?

In one of the cases leading up to Gideon, the

Court noted that ... the right to be heard would

be, in many cases, of little avail if it did not com-

prehend the right to be heard by counsel. Even

the intelligent and educated layman has small

and sometimes no skill in the science of law.

He is unfamiliar with the rules of evidence. He

lacks both the skill and the knowledge adequately

to prepare his defense, even though he has a per-

fect one. He requires the guiding hand of counsel

at every step in the proceedings against him.

Of course, the Court was speaking of crimi-

nal proceedings, but the same holds true in civil

courts. Those who cant afford an attorney are at

a massive disadvantage, and experience much

worse outcomes.

Take the area of housing. A pilot project in Mas-

sachusetts housing courts found that approxi-

mately 1/3 of unrepresented tenants were able

to stay in their homes following an eviction pro-

ceeding, whereas 2/3 of tenants with representa-

tion were able to remain. Every time a family is

evicted, it has to contend with the loss of personal

property, destabilization that affects employment

and education, and the prospect of homelessness.

And while the impact of eviction on a family, and

its consequences, are massive, there are also sig-

nicant effects on state and local governments,

and society as a whole.

In Massachusetts, the Boston Bar Association

reported that the state spent $161 million each

year on homeless shelters and related services.

If 50% of homelessness starts with eviction, then

cutting evictions by just 10% could save the state

$8 million. Similarly, New York City social ser-

vices department calculated that for every $1

spent on representing tenants in eviction proceed-

ings, the city saved $4 in shelter and other social

services costs. Additionally, the employment

prospects of evicted adults suffer, and eviction

disrupts the education of children, both of which

have long-term economic consequences for society

as a whole, in addition to the individual.

BY MICHAEL PAGE

SPECIAL TO THE COURTS MONITOR

see ALLEN page 7

Attorney makes the case for a civil Gideon policy

see GIDEON page 8

OPINION

This elimination of access to justice

falls more heavily on the poor and

minority communities than on those

who can afford to wait for justice or

who dont have to depend on public

transit to get to court 30 miles from

home at 8:30 in the morning.

Page 8 CALIFORNIA COURTS MONITOR, A Special Report UPDATE Follow us on Twitter @cacourtsmonitor

GIDEON from page 3

A growing number of offcials recognize the scope of the problem

The pattern plays out in other types of civil legal

proceedings that touch upon basic human needs.

Victims of domestic violence are often unable to

take the necessary legal steps to protect them-

selves and, frequently, their children, from their

abusers. Parents without proper representation

may lose custody of their children. All of these

possibilities are easily as signicant to someones

life as a possible short jail term.

There are, of course, legal aid organizations

whose mission it is to help people who need rep-

resentation in these areas. But by no measure

can they provide the necessary representation for

more than a small fraction of those who need it.

Funding for legal services has been on the decline

for years, particularly in the recent recession and

the subsequent budgetary contractions. There

simply arent enough lawyers at legal services

organizations to provide representation for the

people who need it.

Twenty years ago, an ABA study showed that

70% of poor people with serious legal needs were

unable to nd help. More recently, in 2003, the

District of Columbia Bar Foundation estimated

that only 10% of the need for legal assistance

was being met. Similar studies in Washington

and Massachusetts showed that roughly 12% and

13%, respectively, of the households needing legal

assistance were able to obtain it. Legal services

agencies are forced to turn away roughly 80% of

those people who come to them for assistance.

There is no way around the fact that more needs

to be done.

So how would civil Gideon work? Would local,

state, and federal governments simply provide

lawyers for everyone who came forward and

claimed to have suffered a legal wrong? No. Vari-

ous proposals have differing details, but similar

basic structures. The idea behind civil Gideon is

to establish a right to counsel in situations where

someone below certain income thresholds is in an

adversarial proceeding, in cases where the most

basic of human needs are at stake.

A recent San Francisco ordinance establishing

a civil Gideon pilot program would limit repre-

sentation to people making 200% of the poverty

level or less, and only for cases dealing with issues

such as housing, safety, or child custody. A peti-

tion to the Wisconsin Supreme Court, which was

denied, sought to require circuit court judges to

appoint representation for indigent litigants

in cases regarding the litigants rights to basic

human needs, including sustenance, shelter, cloth-

ing, heat, medical care, safety and child custody

and placement; the American Bar Associations

Resolution 112A specically mentions shelter,

sustenance, safety, health or child custody.

Of course, there are arguments against civil

Gideon, for reasons either ideological or prag-

matic.

Some of the more ideological objections have

been articulated by Ted Frank, formerly of the

American Enterprise Institute, a consistent advo-

cate of limiting the average citizens access to

courts through tort reform. He suggests that by

providing free counsel, the courts will be ooded

with meritless cases. He also argues that when

poor litigants decide to spend their meager

resources on an attorney, it signals to judges that

they have a serious case, with merit; this, of

course, does nothing for those with meritorious

cases that dont have the resources to do so.

And, nally, he advocates that we switch from

the American rule, where each party pays its

own attorneys fees, to the English rule, where

the losing party has to pay the winners attorneys

fees in addition to whatever damages they are

held liable for. The claim is that private attorneys

would happily take meritorious cases no matter

what the income level of the plaintiff or defen-

dant.

This idea is tort reform boilerplate, and not even

really applicable to the kind of cases with which

the civil Gideon movement is concerned; Franks

references to defendants who are currently forced

to settle extortionate meritless cases because they

cannot afford the overwhelming costs of defense

and an unreasonable plaintiff who attempted to

sue his dry cleaner for millions of dollars in dam-

ages for a lost pair of pants bear no relation at

all to the non-tort proceedings envisioned by civil

Gideon proponents. The apparent actual purpose

of this suggestion is to make it too risky for a

plaintiff with a legitimate, but not ironclad, case

to seek justice for harm done to them, through the

very real possibility that they may be ruined by

having to pay the fees for attorneys representing

someone who could out delay, out lawyer, and ulti-

mately out spend them. The disingenuousness of

this claim is clear when the same author ridicules

cases that are frivolous in the colloquial sense,

albeit not in the technical legal sense and result

in awards, including attorneys fees, that he seems

to feel are extravagant.

On the other hand, there are objections to civil

Gideon that are more pragmatic. Bluntly put,

Gideon itself has not been implemented as well it

should, largely due to budgetary restraints.

Public defenders ofces are underfunded, even

compared to the prosecutors they face off against

in court. The lack of resources means there are

fewer lawyers to cover more cases, spending less

and less time on each.

The Brennan Center reported that in New

Orleans, the public defenders were able to spend

on average 7 minutes on each case; in Minnesota,

it was 12 minutes, not including time in court.

Court-appointed attorneys frequently do not have

the time or resources to properly perform factual

investigations, interview witnesses, or consult

experts; in extreme cases, court-appointed attor-

neys have slept through parts of capital trials.

In less extreme situations, this assembly line

approach to criminal defense has led to an over-

use of plea bargaining, which serves the interest

of prosecutors and overworked defense attorneys,

but not the defendants.

All this considered, its entirely reasonable to

worry that expanding representation to civil pro-

ceedings, without an adequate increase in fund-

ing, will lead to further overburdening of civil

servants.

Another civil Gideon critic, Benjamin Barton,

has suggested that, rather than more money for

more lawyers to represent more indigent litigants,

we would be better served by reforming the treat-

ment of pro se litigants. As he points out, pro se

litigants frequently dont know the basic process:

what forms to ll out, or what or how to argue for

themselves before a judge. Further, court clerks

are instructed to not give legal advice, and judges

dont view the situation as one they have any

responsibility to mitigate.

All of this is true, and no advocate of increased

representation would argue the point. The more

modest reforms he suggests include setting up

special courts for pro se litigants, allowing clerks

to give limited advice, and treating pro se liti-

gants respectfully. Although allowing clerks to

explain peoples legal rights, or court procedure,

would be helpful, there is a danger that litigants

would try to draw them into advocacy roles. And

while there is no question that court staff should

treat all litigants with respect, judges already fre-

quently allow greater leeway to people acting pro

se, which contributes to the role pro se litigants

play in clogging up the courts.

Other pro se reforms would go quite a bit far-

ther changing the role of judges in these pro-

ceedings from that of a neutral arbiter to an

active participant, and changing court rules,

procedures, and forms for pro se litigants. These

changes would greatly alter the nature of the civil

legal system, and actually codify that there would

literally be a different laws for the poor.

Barton even goes so far as to suggest that courts

should base pro se proceedings on eBays online

dispute resolution; how that could possibly work

in a legal setting isnt explained.

Some of these are interesting suggestions, but

despite the fact that everyone obviously has the

right to act as his or her own attorney, it simply

isnt a good idea to increase reliance on people

acting as their own attorneys.

Beyond clogging up the courts with confused

arguments and missing paperwork, pro se litigants

are also able to bring meritless suits for nonexistent

causes of action that no lawyer would bring for fear

of sanction. Representation eases a complicated

process, reduces truly meritless claims, and enables

people to reach settlements where otherwise they

might not be able to recover anything at all after

taking up time and resources that the courts need

for other cases. For example, the Minnesota Legal

Services Coalition has estimated that by helping

cases settle pre-trial and reducing meritless claims,

it has saved the court $5.1 million annually.

Unfortunately, we cant pretend that increasing

efciency in the courts will fully offset the costs

of providing representation in all the cases that

involve these basic human needs. But even in

purely economic terms, there are other benets

reduced necessity for social services spending,

long term educational benets of being able to

stay in ones home instead of being evicted and the

increased prosperity they bring, someone receiv-

ing medical care that allows them to work rather

than go on disability. From a societal standpoint,

increased real access to the courts will reinforce

peoples faith in the system.

And, ultimately, it is a moral question; in the

words of one California Court of Appeals Justice,

poor people have access to the American courts

in the same sense that the Christians had access

to the lions when they were dragged into a Roman

arena. Are we willing to accept that as a society?

Luckily, a growing number of legal scholars,

judges, bar associations and legislators have

recognized the scope of the problem. While the

Supreme Court is unlikely to overturn Lassiter

any time soon, and recognize a constitutional

right to civil counsel in all the necessary situa-

tions, the Court is not the only option. Litigation

in state courts may lead to those rights being

recognized under those states constitutions,

and there is nothing to prevent legislatures

with the necessary will from creating those rights

by law. Many states provide the right to counsel

in some civil proceedings, and limited pilot pro-

grams have started in Massachusetts, Illinois and

California.

The task now is to continue this work and

expand those rights so that nobody will have to go

into court without adequate representation when

their basic human needs are at stake.

(Michael Page is a Washington, D.C.-based

attorney and legal rights activist. This is his

rst contribution to the Courts Monitor, and the

conversation continues online. You can respond

to his argument for Civil Gideon at www.nation-

alcourtsmonitor.com.)

The Brennan Center reported that in New

Orleans, the public defenders were able

to spend on average 7 minutes on each

case; in Minnesota, it was 12 minutes, not

including time in court. Court-appointed

attorneys frequently do not have the time

or resources to properly perform factual

investigations, interview witnesses, or

consult experts; in extreme cases, court

appointed attorneys have slept through

parts of capital trials.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Prosecutorial Misconduct: Jeff Rosen District Attorney Subordinate Jay Boyarsky - Santa Clara CountyDocument2 pagesProsecutorial Misconduct: Jeff Rosen District Attorney Subordinate Jay Boyarsky - Santa Clara CountyCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasPas encore d'évaluation

- Prosecutor Misconduct: Jeff Rosen District Attorney of Santa Clara County Controversy - Silicon Valley Criminal JusticeDocument1 pageProsecutor Misconduct: Jeff Rosen District Attorney of Santa Clara County Controversy - Silicon Valley Criminal JusticeCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasPas encore d'évaluation

- Angelina Jolie V Brad Pitt: Order On Misconduct by Judge John OuderkirkDocument44 pagesAngelina Jolie V Brad Pitt: Order On Misconduct by Judge John OuderkirkCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasPas encore d'évaluation

- Respondent's Statement of Issues in Re Marriage of Lugaresi: Alleged Human Trafficking Case Santa Clara County Superior Court Judge James ToweryDocument135 pagesRespondent's Statement of Issues in Re Marriage of Lugaresi: Alleged Human Trafficking Case Santa Clara County Superior Court Judge James ToweryCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasPas encore d'évaluation

- Angelina Jolie V Brad Pitt: Disqualification of Judge John Ouderkirk - JAMS Private JudgeDocument11 pagesAngelina Jolie V Brad Pitt: Disqualification of Judge John Ouderkirk - JAMS Private JudgeCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasPas encore d'évaluation

- 2016 US DOJ MOU With St. Louis County Family CourtDocument24 pages2016 US DOJ MOU With St. Louis County Family CourtCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasPas encore d'évaluation

- Federal Class Action Lawsuit Against California Chief Justice Tani Cantil-Sakauye For Illegal Use of Vexatious Litigant StatuteDocument55 pagesFederal Class Action Lawsuit Against California Chief Justice Tani Cantil-Sakauye For Illegal Use of Vexatious Litigant StatuteCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story Ideas100% (1)

- District Attorney Jeff Rosen Misconduct: Santa Clara County District Attorney's Office - Silicon Valley Criminal JusticeDocument1 pageDistrict Attorney Jeff Rosen Misconduct: Santa Clara County District Attorney's Office - Silicon Valley Criminal JusticeCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasPas encore d'évaluation

- Silicon Valley District Attorney Threatens Whistleblower Complaint Against Public Defender Over Protest Blog PostsDocument8 pagesSilicon Valley District Attorney Threatens Whistleblower Complaint Against Public Defender Over Protest Blog PostsCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasPas encore d'évaluation

- DA Jeff Rosen Prosecutor Misconduct: Assistant DA Boyarsky Rebuked by Court - Santa Clara County - Silicon ValleyDocument4 pagesDA Jeff Rosen Prosecutor Misconduct: Assistant DA Boyarsky Rebuked by Court - Santa Clara County - Silicon ValleyCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasPas encore d'évaluation

- "GENERAL ORDER RE: EXPRESSIVE ACTIVITY" Restricting Free Speech Outside Santa Clara County Courthouses Issued by Presiding Judge Patricia Lucas on February 22, 2017 - Civil Rights - Free Speech - Freedom of Association - Constitutional RightsDocument4 pages"GENERAL ORDER RE: EXPRESSIVE ACTIVITY" Restricting Free Speech Outside Santa Clara County Courthouses Issued by Presiding Judge Patricia Lucas on February 22, 2017 - Civil Rights - Free Speech - Freedom of Association - Constitutional RightsCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasPas encore d'évaluation

- Judge Jack Komar: A Protocol For Change 2000 - Santa Clara County Superior Court Controversy - Judge Mary Ann GrilliDocument10 pagesJudge Jack Komar: A Protocol For Change 2000 - Santa Clara County Superior Court Controversy - Judge Mary Ann GrilliCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasPas encore d'évaluation

- Motion to Dismiss for Loss or Destruction of Evidence (Trombetta) Filed July 5, 2018 by Defendant Susan Bassi: People v. Bassi - Santa Clara County District Attorney Jeff Rosen, Deputy District Attorney Alison Filo - Defense Attorney Dmitry Stadlin - Judge John Garibaldi - Santa Clara County Superior Court Presiding Judge Patricia Lucas - Silicon Valley California -Document15 pagesMotion to Dismiss for Loss or Destruction of Evidence (Trombetta) Filed July 5, 2018 by Defendant Susan Bassi: People v. Bassi - Santa Clara County District Attorney Jeff Rosen, Deputy District Attorney Alison Filo - Defense Attorney Dmitry Stadlin - Judge John Garibaldi - Santa Clara County Superior Court Presiding Judge Patricia Lucas - Silicon Valley California -California Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story Ideas100% (2)

- Opposition to Motion to Dismiss (Trumbetta) Filed August 9, 2018 by Plaintiff People of the State of California:: People v. Bassi - Santa Clara County District Attorney Jeff Rosen, Deputy District Attorney Alison Filo - Defense Attorney Dmitry Stadlin - Judge John Garibaldi - Santa Clara County Superior Court Presiding Judge Patricia Lucas - Silicon Valley California -Document4 pagesOpposition to Motion to Dismiss (Trumbetta) Filed August 9, 2018 by Plaintiff People of the State of California:: People v. Bassi - Santa Clara County District Attorney Jeff Rosen, Deputy District Attorney Alison Filo - Defense Attorney Dmitry Stadlin - Judge John Garibaldi - Santa Clara County Superior Court Presiding Judge Patricia Lucas - Silicon Valley California -California Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasPas encore d'évaluation

- Judge Bruce Mills Misconduct Prosecution by the Commission on Judicial Performance: Report of the Special Masters: Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law - Contra Costa County Superior Court Inquiry Concerning Judge Bruce Clayton Mills No. 201Document38 pagesJudge Bruce Mills Misconduct Prosecution by the Commission on Judicial Performance: Report of the Special Masters: Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law - Contra Costa County Superior Court Inquiry Concerning Judge Bruce Clayton Mills No. 201California Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story Ideas100% (1)

- E.T. v. Ronald George Class Action Complaint USDC EDCADocument55 pagesE.T. v. Ronald George Class Action Complaint USDC EDCACalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasPas encore d'évaluation

- Terry Houghton and Valerie Houghton Felony Criminal Complaint and DocketDocument64 pagesTerry Houghton and Valerie Houghton Felony Criminal Complaint and DocketCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasPas encore d'évaluation

- Federal Criminal Indictment - US v. Judge Joseph Boeckmann - Wire Fraud, Honest Services Fraud, Travel Act, Witness Tampering - US District Court Eastern District of ArkansasDocument13 pagesFederal Criminal Indictment - US v. Judge Joseph Boeckmann - Wire Fraud, Honest Services Fraud, Travel Act, Witness Tampering - US District Court Eastern District of ArkansasCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasPas encore d'évaluation

- Opposition to Murgia Motion to Compel Discovery Filed August 9, 2018 by Plaintiff People of the State of California: People v. Bassi - Santa Clara County District Attorney Jeff Rosen, Deputy District Attorney Alison Filo - Defense Attorney Dmitry Stadlin - Judge John Garibaldi - Santa Clara County Superior Court Presiding Judge Patricia Lucas - Silicon Valley California -Document6 pagesOpposition to Murgia Motion to Compel Discovery Filed August 9, 2018 by Plaintiff People of the State of California: People v. Bassi - Santa Clara County District Attorney Jeff Rosen, Deputy District Attorney Alison Filo - Defense Attorney Dmitry Stadlin - Judge John Garibaldi - Santa Clara County Superior Court Presiding Judge Patricia Lucas - Silicon Valley California -California Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasPas encore d'évaluation

- In The Court of Appeal of The State of California: Third Appellate DistrictDocument13 pagesIn The Court of Appeal of The State of California: Third Appellate DistrictCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story Ideas100% (1)

- Garrett Dailey Attorney Misconduct - Perjury Allegations in Marriage of Brooks - Attorney Bradford Baugh, Joseph RussielloDocument2 pagesGarrett Dailey Attorney Misconduct - Perjury Allegations in Marriage of Brooks - Attorney Bradford Baugh, Joseph RussielloCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasPas encore d'évaluation

- Placing Children at Risk: Questionable Psychologists and Therapists in The Sacramento Family Court and Surrounding Counties - Karen Winner ReportDocument153 pagesPlacing Children at Risk: Questionable Psychologists and Therapists in The Sacramento Family Court and Surrounding Counties - Karen Winner ReportCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story Ideas50% (2)

- Profile of Justice Coleman A. Blease, California Appellate Courts - Third DistrictDocument3 pagesProfile of Justice Coleman A. Blease, California Appellate Courts - Third DistrictCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasPas encore d'évaluation

- In The Court of Appeal of The State of California: Appellant'S Reply BriefDocument19 pagesIn The Court of Appeal of The State of California: Appellant'S Reply BriefCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story Ideas100% (1)

- Appellant'S Opening Brief: in The Court of Appeal of The State of CaliforniaDocument50 pagesAppellant'S Opening Brief: in The Court of Appeal of The State of CaliforniaCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasPas encore d'évaluation

- Judicial Profile: Coleman Blease, 3rd District Court of Appeal CaliforniaDocument3 pagesJudicial Profile: Coleman Blease, 3rd District Court of Appeal CaliforniaCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasPas encore d'évaluation

- Qeourt of Peal of TBT S Tatt of Qealifomia: Third Appellate DistrictDocument2 pagesQeourt of Peal of TBT S Tatt of Qealifomia: Third Appellate DistrictCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasPas encore d'évaluation

- In The Court of Appeal of The State of California: AppellantDocument4 pagesIn The Court of Appeal of The State of California: AppellantCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasPas encore d'évaluation

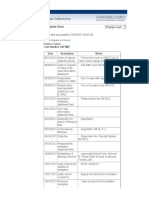

- 3rd Appellate District Change Court: Court Data Last Updated: 03/26/2017 08:40 AMDocument9 pages3rd Appellate District Change Court: Court Data Last Updated: 03/26/2017 08:40 AMCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasPas encore d'évaluation

- In The Court of Appeal of The State of CaliforniaDocument9 pagesIn The Court of Appeal of The State of CaliforniaCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasPas encore d'évaluation

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Training and DevelopmentDocument46 pagesTraining and DevelopmentRavi JoshiPas encore d'évaluation

- Level of GovernmentDocument17 pagesLevel of GovernmentPAULOPas encore d'évaluation

- 2016-2019 Sip MinutesDocument2 pages2016-2019 Sip Minutesloraine mandapPas encore d'évaluation

- Balance and Safety Mechanism PDFDocument11 pagesBalance and Safety Mechanism PDFKhesmin KapilPas encore d'évaluation

- The Poems of Henry Van DykeDocument493 pagesThe Poems of Henry Van DykeChogan WingatePas encore d'évaluation

- Journey of The Company:: Carlyle Group Completes 10 % Exit in SBI Card Through IPODocument3 pagesJourney of The Company:: Carlyle Group Completes 10 % Exit in SBI Card Through IPOJayash KaushalPas encore d'évaluation

- Additional Illustrations-5Document7 pagesAdditional Illustrations-5Pritham BajajPas encore d'évaluation

- Deposition Hugh Burnaby Atkins PDFDocument81 pagesDeposition Hugh Burnaby Atkins PDFHarry AnnPas encore d'évaluation

- CASE DIGEST - Metrobank vs. CADocument7 pagesCASE DIGEST - Metrobank vs. CAMaria Anna M Legaspi100% (1)

- Entrep 3Document28 pagesEntrep 3nhentainetloverPas encore d'évaluation

- AH 0109 AlphaStarsDocument1 pageAH 0109 AlphaStarsNagesh WaghPas encore d'évaluation

- Bjorkman Teaching 2016 PDFDocument121 pagesBjorkman Teaching 2016 PDFPaula MidãoPas encore d'évaluation

- Deadly Force Justified in Roosevelt Police ShootingDocument6 pagesDeadly Force Justified in Roosevelt Police ShootingGeoff LiesikPas encore d'évaluation

- Metaswitch Datasheet Perimeta SBC OverviewDocument2 pagesMetaswitch Datasheet Perimeta SBC OverviewblitoPas encore d'évaluation

- Syllabus 2640Document4 pagesSyllabus 2640api-360768481Pas encore d'évaluation

- 71english Words of Indian OriginDocument4 pages71english Words of Indian Originshyam_naren_1Pas encore d'évaluation

- Problems On Financial AssetsDocument1 pageProblems On Financial AssetsNhajPas encore d'évaluation

- Career CenterDocument5 pagesCareer Centerapi-25949018Pas encore d'évaluation

- 2023 Commercial and Taxation LawsDocument7 pages2023 Commercial and Taxation LawsJude OnrubiaPas encore d'évaluation

- EGN - 5622 - Warehouse Management - Part 1 Lab 8Document32 pagesEGN - 5622 - Warehouse Management - Part 1 Lab 8kkumar1819Pas encore d'évaluation

- Title Investigation Report (Tir)Document6 pagesTitle Investigation Report (Tir)surendragiria100% (1)

- Module 2Document30 pagesModule 2RarajPas encore d'évaluation

- Kashmir DisputeDocument13 pagesKashmir DisputeAmmar ShahPas encore d'évaluation

- Josefa V MeralcoDocument1 pageJosefa V MeralcoAllen Windel BernabePas encore d'évaluation

- OSH Standards 2017Document422 pagesOSH Standards 2017Kap LackPas encore d'évaluation

- The Fox That Killed My GoatDocument7 pagesThe Fox That Killed My Goatsaurovb8Pas encore d'évaluation

- Spear v. Place, 52 U.S. 522 (1851)Document7 pagesSpear v. Place, 52 U.S. 522 (1851)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- DDI - Company Profile 2024Document9 pagesDDI - Company Profile 2024NAUFAL RUZAINPas encore d'évaluation

- Annexes G - Attendance SheetDocument2 pagesAnnexes G - Attendance SheetrajavierPas encore d'évaluation