Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Mycenaean Craft Economy and Market Exchange

Transféré par

Muammer İreçDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Mycenaean Craft Economy and Market Exchange

Transféré par

Muammer İreçDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

American Journal of Archaeology 117 (2013) 43745

437

Crafts, Specialists, and Markets in Mycenaean Greece

Exchanging the Mycenaean Economy

DANIEL J. PULLEN

available online as open access FORUM

Abstract

This article examines the palatial and nonpalatial

organization of craft production and exchange in the

Late Bronze Age Argolid. The Late Bronze Age elites

controlled markers of status and prestige, which were

institutionalized in palatial control of the production

and consumption of prestige goods. At Mycenae, the

existence of attached ceramic workshops is evidence for

palatial interest in the production and distribution of

a wider range of ceramics than existed at the palace at

Pylos, which was interested only in kylikes. Communities

in Mycenaes territory, such as Tsoungiza, used ceramic

assemblages nearly identical to those of the palatial elites.

Given the quantities of ceramic vessels needed annually

to supply the entire polity, it is unlikely that these were

allocated via mechanisms of palatial control. Instead, we

must consider multiple mechanisms of distribution in

addition to redistribution, including market exchange.

Likewise, we must consider one individual to be engaged

in transactions both with the palace (redistribution, tax

payments) and with the surrounding communities (reci-

procity and market exchange). Markets serve to horizon-

tally integrate households in a community or region and

to vertically integrate those households with the center.

Other evidence for market exchange, such as weights and

measures and the road network, is explored.*

introduction

One of the principal methods of studying the po-

litical economy of a society is to examine how the

production, distribution, and consumption of goods

and commodities are controlled by the various insti-

tutions of that society. In this article, I focus on craft

production and its distribution, particularly the role

that exchange of manufactured items, such as ce-

ramics, may have played in the political economy of

the Late Bronze Age (ca. 16001100 B.C.E.) Argolid,

Greece. The Argolid presents an interesting case, for

it holds at least three palace centers, perhaps com-

peting with one another, in a region similar in size to

Messenia, which has a single palace center (ca. 2,000

km

2

). Although Linear B has been found at several

sitesMycenae, Tiryns, Mideawe lack a large, well-

studied Linear B archive such as that of the Palace of

Nestor at Pylos in Messenia. We have arguably more

excavations of Late Bronze Age sites in the Argolid

than of any other similar region in mainland Greece,

but for some topics, such as the palatial economy, our

understanding of the region is less comprehensive

than our understanding of the palatial economy of

Late Bronze Age Messenia.

1

Nevertheless, my aim is to

construct a model of craft production and exchange

that emphasizes both the palatial and the nonpalatial

components. Because I emphasize variability within

the Argolid, I use the term Mycenaean only in ref-

erence to the site of MycenaeI use the term Late

Bronze Age for all other sites and areas within the

Argolid and elsewhere.

the political organization of the argolid

Perhaps one of the most important results of recent

work on the nature of the state in the Aegean is the real-

ization of great variability among the Late Bronze Age

mainland polities (as well as among the Bronze Age

Cretan polities) based in part on different historical

*

I would like to thank the organizers of the colloquium at

the 113th Annual Meeting of the Archaeological Institute of

America (Philadelphia, 2012), Bill Parkinson, Dimitri Nakas-

sis, and Mike Galaty, for their invitation to participate; Gary

Feinman and Cynthia Shelmerdine for their insightful com-

ments; and Julie Hruby and Jamie Aprile for providing me

copies of their contributions in advance. I thank all of them

for their input. I would also like to thank AJA Editor-in-Chief

Naomi J. Norman for her enthusiastic support of this Forum

and our previous one on redistribution (Galaty et al. 2011). I

would like to dedicate this article to the memory of Harold K.

Schneider, who rst introduced me to the study of economics

in anthropology as a graduate student at Indiana University

I hope I have succeeded in meeting his expectations.

1

Shelmerdine and Bennet 2008, 28990.

DANIEL J. PULLEN 438 [AJA 117

trajectories.

2

Detailed architectural studies of the pal-

aces at Pylos and Mycenae have demonstrated very

different developmental histories of those structures,

and this certainly contributes to our questioning of

how different the societies were in the two regions.

3

The political geography of the Argolid is very different

from that of Messenia, and one wonders how different

the political organization was as well. The political ge-

ography of the Argolid is complicated by the presence

of multiple palaces, fortified citadels, and other major

centers, most of which are within but a few hours walk

from one another.

4

This has led to several different

mappings of the political geography, from one with

Mycenae as the only true administrative center, and

Tiryns thus subordinate,

5

to one with six or more inde-

pendent polities.

6

Cherry, largely following Renfrews

division based on the presence of Linear B tablets at

Mycenae and Tiryns,

7

suggested that the Argolid was

divided into two states.

8

Rather than imposing a model derived from the

Linear B texts at Pylos as in the previous models,

Voutsaki uses the data from the Argolid itself to sug-

gest three centers, Mycenae, Tiryns, and Midea, in

the peak palatial period, Late Helladic (LH) IIIB.

9

She employs a diachronic approach to illustrate the

shifting importance of sites in the Argolid,

10

from the

beginning of the Middle Helladic to LH IIIB. Her

analysis is based on the appearance of valuable items

in mortuary contexts, the only body of evidence she

believes suitable for this diachronic study. Voutsakis

study has the advantage of reconstructing the process

of centralization toward the palatial sites of Mycenae,

Tiryns, and Midea/Dendra at the expense of sites such

as Argos, Lerna, and Asine. In addition to the mortu-

ary evidence, she uses the settlement evidence in LH

IIIB to label Mycenae, Tiryns, and Midea the three

palatial centers of the Argive Plain. Here, I follow her

identification of three palatial centers for the Argolid

in LH IIIB, but with the caveat that the relationships

among these three centers are still open for debate.

More important than the division of the Argolid into

distinct states is the application to Late Bronze Age

Greece of Renfrews peer-polity interaction model,

11

in which multiple small-scale states share a number

of featurespolitical, ideological, linguistic, symbolic,

and materialat a level of specificity which does not

find ready explanation in terms of common descent or

environmental constraint.

12

As Voutsaki and Parkin-

son and I, among others, argue, the Argolid political

geography developed in a system of intense compe-

tition and interaction among similar-sized polities.

13

Craft production and distribution, I believe, played a

key role in that system.

palatial and nonpalatial craft production

in the political economy of the argolid

As several scholars have noted recently,

14

our un-

derstanding of Late Bronze Age political economies

has radically changed in the last few years. No longer

do we characterize the political economy of a Late

2

Parkinson and Galaty 2007; Nakassis et al. 2010. Kilians

(1988, 293, g. 1) hierarchical model of the Mycenaean state,

which he based on the Linear B tablets from Pylos, is often

used to illustrate the political organization, and by extension

the economic organization, of the Late Bronze Age king-

doms. While this makes for a neat illustration, it glosses over

a number of issues, such as the assumption that all the Late

Bronze Age states functioned in an identical manner.

3

For Pylos, see Nelson 2001. For Mycenae, see Fitzsimons

2006.

4

Voutsaki 2010a, 606.

5

Bintliff 1977.

6

Kilian (1988, 297, g. 3) applied his hierarchical model of

the Late Bronze Age state to the Argolid, making each of the

ve fortied citadel sites, Mycenae, Midea, Tiryns, Argos, and

Nauplion, as well as the sites of Lerna and Asine, centers of

independent kingdoms, with each controlling smaller sites in

the surrounding region in a classic central place model; see

also Burns 2010a, 168.

7

Renfrew 1975; Cherry 1986. Midea has produced only

Linear B nodules so far (Walberg 2007, 179).

8

This division of the Argolid (and indeed the entire north-

eastern Peloponnese, including the Corinthia and much of

Arcadia and Achaia) into two polities of roughly equal size, by

employing Thiessen polygons, was corroborated, in Cherrys

(1986) view, by the rough equivalence of the theoretical poly-

gon drawn on Pylos with the territory of the Pylian kingdom

as delineated in the Linear B archives, as well as the similar-

ity between the proposed Thiessen territories and Homers

(Il. 2.55980) assignment of towns in the Argolid contribut-

ing men to the Trojan expedition under either Agamemnon

or Diomedes in the Catalogue of the Ships; see also Burns

2010a. Cf. the arguments of Pullen and Tartaron (2007) that

the northern Corinthia was not part of the territory of Myce-

nae, at least before Late Helladic (LH) IIIB.

9

Voutsaki 2010b.

10

I.e., Asine, Argos, Mycenae, Tiryns, Midea, and Berbati.

11

Renfrew 1986.

12

Cherry 1986, 19. Aspects of the peer-polity interaction

model have been invoked by other scholars in the study of

Late Bronze Age polities (e.g., Galaty and Parkinson 2007;

Parkinson and Galaty 2007). Renfrew (1975, 1216), in his

original formulation of the early state module, based in part

on Late Bronze Age Greece, suggested 1,500 km

2

for the av-

erage size of the individual territories within a group of peer

polities, with an average distance between centers of ca. 40 km

(though that could vary from 20 to 100 km). A circle of 1,500

km

2

has a radius of ca. 22 km, similar to the estimated daily

distance of human or animal portage.

13

Voutsaki 2010b; Parkinson and Pullen (forthcoming).

14

See papers in Pullen 2010a; Parkinson et al. 2013.

EXCHANGING THE MYCENAEAN ECONOMY 2013] 439

Bronze Age state as a monolithic, redistributive in-

stitution controlled entirely by the palaces. It is now

clear that there were large segments of the economy

that the palatial centers were not heavily involved in

or ignored completely.

15

Instead, we now understand

that the palatial component of the economy coexisted

and interacted with the nonpalatial component, espe-

cially in economic realms such as agriculture, ceram-

ics, and chipped stone. Still, recent studies of political

economy continue to focus on the nonpalatial com-

ponent from the perspective of the palatial centers,

and consumption studies rarely move beyond mortu-

ary consumption of elite products at palatial centers.

16

In part, this focus on the palatial centers is due to our

data sources: most of our data comes from mortuary

contexts and palatial and other large centers, but very

little comes from domestic contexts. Regional surveys,

exploration of nonpalatial centers, and new readings

of the Linear B texts have greatly contributed to this

revised understanding of the Late Bronze Age palatial

economies. The use of the plural economies should

be noted; because there is variation among the Late

Bronze Age states, we should consider each states

political economy on its own.

17

The Late Bronze Age elites were concerned with the

control of markers of status and prestige. This became

institutionalized in palatial control of the production

and consumption of prestige goods, whether through

control of the raw (and often imported) materials

or the distribution of the finished goods to selected

consumers. This pattern is well established in both

the Linear B data at Pylos and in the distribution of

material in tombs in the Argolid. But the pattern of

palatial involvement varies from one center to another,

even within the Argolid. Voutsaki has gathered data

on the production and consumption of valuable items

at the three palatial sites in the Argolid. Her table of

the workshops working with precious materials at the

three sites clearly shows that Mycenae controlled the

production of items in ivory and gold,

18

though Midea

and Tiryns have evidence for production of items (esp.

jewelry) made of glass, semiprecious stones, and metals

such as bronze and lead. Likewise, her table of con-

sumption of valuables in the domestic sphere, rather

than in mortuary contexts,

19

shows that Mycenae far

exceeds the number of items at Tiryns and Midea. Fur-

thermore, Mycenae has a greater diversity of materials

and more unique items, such as the famous Ivory Trio,

than the other two sites. From these data, Voutsaki ar-

gues that the evidence suggests that Mycenae exerted

control over both the production and consumption of

prestige items, primarily the most coveted ones such

as gold and ivory, and thereby controlled the means

for social reproduction . . . [and] the means by which

people negotiated their position and competition

for status.

20

This control was through networks of al-

liances, as can be seen in the shifting importance of

sites across the Argolid from Middle Helladic (MH) I

to LH IIIB. As Voutsaki emphasizes, however, this con-

trol was not over all aspects of life, nor indeed over all

aspects of production, exchange, and consumption,

but over the means to create social distance between

elites and nonelites, as well as between those elites at

Mycenae and those elites at Tiryns and Midea.

But what about nonprestige craft items, such as

ceramics, or nonpalatial craft production, exchange,

and consumption? This is an area that has seen little

attention, other than studies of, for example, chipped

stone and ceramics.

21

This is in part due to the inher-

ent assumption by many that the more important com-

ponents in the political economy were controlled by

the elites. But perhaps the greatest hindrance for the

issue at hand is the great lack of data from household

contexts.

22

We can discuss craft production at palatial

centers, such as Midea, but without data for household

production and consumption we cannot really address

the full range of craft production and consumption in

the economy.

Sjberg, in her review of the settlement data from

the Late Bronze Age Argolid, was hard-pressed to find

much evidence for workshops outside the palatial

centers, other than the well-known pottery kiln at the

Berbati Mastos site.

23

But we must keep in mind that

there is very little domestic architecture of Late Bronze

15

Halstead 1992, 2007; Sjberg 2004.

16

Whitelaw 2001.

17

Pullen 2010b. This is not to deny that there may well have

been great similarities among the various states, as modeled

by peer-polity interaction, but until we understand the indi-

vidual political economies of the Late Bronze Age states we

cannot generalize to the Late Bronze Age Political Econo-

my. For an example of new interpretations of Linear B texts,

see Nakassis 2006, (forthcoming).

18

Voutsaki 2010b, 102, table 5.4.

19

Voutsaki 2010b, 102, table 5.5.

20

Voutsaki 2010b, 102.

21

Parkinson 2007, 2010; Galaty 2010.

22

E.g., we lack much botanical or faunal evidence for exam-

ining agriculture. See Dabney (1997, 471) for a plea for the

excavation of more domestic structures to better understand

the scale of craft production throughout the Late Bronze Age

economy.

23

Sjberg 2004; see also kerstrm 1968.

DANIEL J. PULLEN 440 [AJA 117

Age date from any Argolid site outside the three pala-

tial centers.

24

Farther afield, in the Corinthia, domes-

tic architecture appears at Zygouries and Tsoungiza,

which may have been connected to the Argolid in the

Palatial period.

25

At LH III Tsoungiza, there is virtu-

ally no evidence for craft products other than ceramic

items,

26

yet Thomas study of the LH IIIB1 pottery sug-

gests consumption patterns of ceramics at Tsoungiza

that emulate those of the elites at Mycenae.

27

If this is

the case, then the inhabitants of Tsoungiza most likely

obtained their ceramics from the same sources as the

elites did at Mycenae. The question of relevance here,

then, is the mechanism by which the inhabitants of

Tsoungiza obtained those ceramics.

Given that ceramics seem to be one of the principal

sets of data available for examining the issue of palatial

control of the political economy,

28

I focus on pottery

production, exchange, and consumption. In a paper

to be published soon, Parkinson and I argue that there

are differences between the ways pottery distribution

and consumption were organized in the Argolid com-

pared with Messenia.

29

The scale and organization of

specialized ceramic production seems to have been

similar in Mycenae and Pylos, but the distribution and

consumption of the specialized ceramics produced in

these different regions were significantly different. The

Messenian elite attempted to control the production

of kylikes, which were used during feasts sponsored

by the palatial elite to promote alliance formation.

30

At Mycenae, though, the elites seem to have con-

trolled a wide variety of ceramic forms, in part for

export consumption. Mycenae developed within the

context of intense peer-polity interaction among the

centers in the Argolid. One strategy employed by the

elite at Mycenae was the control of exotic items and

materials obtained through long-distance trade and

the transformation through attached workshops of

these materials into objects that could be used to ce-

ment alliances with elites at lower levels and in neigh-

boring polities.

31

Palatial administrators needed to

co-opt craft production, such as production of ceram-

ics, in part to fuel this alliance building. As a result

of this peer-polity interaction, there was increased

urgency for the elite at Mycenae to control not only

those aspects of specialized production that related

to internal systems of alliance formation and status

negotiation (i.e., the workshops specializing in high-

value items) but also those aspects, such as ceramic

production, that articulated with external systems of

exchange. The relative uniformity of Late Bronze Age

ceramic products in the Argolid, and elsewhere, sug-

gests a few large-scale producers, which would have

been likely candidates for palatial control.

32

But did

the palatial elite at Mycenae control the entire pro-

duction and distribution of ceramic vessels from these

workshops? Were there alternate mechanisms for the

distribution of ceramic vessels?

exchange and markets in the late bronze

age aegean

The study of exchange in Aegean archaeology in

particular has been hindered by the very data that al-

low detailed knowledge of the economy: the Linear B

tablets. A particular lacuna has been the study of mar-

kets, in large part because of the adherence to Finley

and Polanyis model, based on the tablets from Pylos,

of the total redistributive economy controlled by the

palace.

33

Renfrew, in his study of trade that featured

24

Only Asine and Berbati have produced domestic archi-

tecture with signicant preservation. Buildings G, I, and K at

Asine were originally dated to LH IIIB (Frdin and Persson

1938, 90) but are now dated to LH IIIC, along with Building

H (Sjberg 2004, 319). At Berbati, the building succeeding

the kiln is still dated to LH IIIA2B (Schallin 2002; Sjberg

2004, 73).

25

Blegens (1928, 308) so-called Potters Shop at Zygou-

ries is now identied as a mixed domestic and workshop

structure, not for the manufacture of pottery but for some

other product (Thomas 1992). For Tsoungiza, see Wright et

al. 1990, 62938. In addition, there is limited domestic archi-

tecture from Korakou (Houses P, M, and H from LH IIIBC)

(Blegen 1921). The extensive LH IIIB architecture at Kalami-

anos has not been excavated (Tartaron et al. 2011).

26

Dabney (1997, 469) mentions a bronze dagger of Pe-

schiera type as one of the few exceptions to the lack of non-

ceramic craft products.

27

Thomas 2005, 540; see also Dabney 1997, 46970.

28

Whitelaw (2001) also sees ceramics as an appropriate

data set to address the question of palatial controlin this

case, those ceramics found in the palace at Pylos.

29

Parkinson and Pullen (forthcoming).

30

Galaty and Parkinson 2007; Galaty 2010; Nakassis 2010.

31

For long-distance trade, see Burns 2010a. For attached

workshops, see Shelton 2010; Voutsaki 2010b. Shelton (2002

2003) suggests that the intensive ceramic production at My-

cenaes Petsas House seems to have been in the process of

becoming attached to the palace; some of the earliest Linear

B tablets known on the mainland, dating to LH IIIA2, are

found in the Petsas House. The Mastos workshop in the Ber-

bati Valley (kerstrm 1968), which was used through LH

IIIB, is another example of intensive, attached ceramic pro-

duction. Both the Petsas House and Berbati workshops are

associated with the Mycenae-Berbati instrumental neutron

activation analysis (INAA) chemical group and shared a com-

mon clay source (Mommsen et al. 2002), and they likely were

associated with the palatial center at Mycenae.

32

Thomas 2005, 540 (citing Sherratt 1982).

33

Polanyi 1968; Finley 1973.

EXCHANGING THE MYCENAEAN ECONOMY 2013] 441

variations on distance-decay models, found similar

patterns in central-place redistribution and central-

place marketplace exchange,

34

and, as Stark and Gar-

raty comment, this similarity in product dissemination

contributed to the lack of interest in pursuing market

exchange.

35

Sjberg, in an attempt to test whether cen-

tralized redistribution or market exchange could be

identified in the Late Bronze Age Argolid, concludes

that a controlled and centralized economy based

on redistribution could not be confirmed,

36

in large

part because of the lack of large-scale storage facili-

ties. She argues that the poor archaeological evidence

for workshops does not indicate that production was

concentrated in the palatial centers. As noted above,

the workshop evidence from the Argolid is primarily

associated with palace centers, and these workshops

were producing goods for obvious elite consumption.

She emphasizes exchange at various levels, from lo-

cal household-to-household exchange to the vertical

flow of goods to the three palatial centers in LH IIIB.

Exchange not associated with the palaces most likely

involved reciprocity or, as she seems to prefer, market

exchange. In the literature of the Aegean Bronze Age,

occasionally a reference will be made to exchange

without specifying the mode, and one wonders wheth-

er markets were in the mind of the writer; more of-

ten, however, the term exchange is attached to the

word trade and means international trade.

37

In the last few years, though, the study of mar-

kets in other regions of the world by archaeologists

has grown.

38

This increased interest coincides with

the reconsideration of political economies and the

emergence of the state, coupled with an increasing

critique of the Polanyian paradigm. The identifica-

tion of markets, market exchange, and marketplaces

is problematic,

39

but a number of studies point to the

integration of several different institutions in the po-

litical economy of a culture, including elite control of

prestige goods, market exchange (with involvement,

even outright control, by elites), reciprocity, and so

on, as Hruby discusses.

40

Thus, we should consider

market exchange along with gift exchange, redistri-

bution, and other modes of distribution of products.

If the palace at Mycenae was heavily involved in pot-

tery distribution and consumption, how did a small

community like Tsoungiza (with perhaps only 10

households) obtain its large quantity of pottery that

seems to mirror that of Mycenae in assemblage, shapes,

and decoration? Was it through means of allocations

by the palatial authorities? Could the palatial authori-

ties handle, or would they want to, the necessary 700

1,000 vessels per annum suggested for replacement

of broken pots at Tsoungiza?

41

And if we consider the

larger territory dependent on the center at Mycenae

to consist of 5,000 or even 10,000 households, the scale

of production and distribution of ceramic vessels be-

comes enormous.

42

While it is possible that the palace

allocated the pots needed by individual households, it

would seem more likely that communities in Mycenaes

orbit used other means of obtaining these vessels, such

as the mechanism of market exchange.

43

The palace at

Mycenae would have constituted the largest consumer

of ceramics, commanding a higher percentage of ce-

ramic production than did the palace at Pylos for the

purposes of export, and thus could well have set the

standards of consumption that a community like

34

Renfrew 1975, 423.

35

Stark and Garraty (2010, 401). Renfrew (1975, 52) iden-

tied storage facilities as a necessary feature of redistribu-

tion, but it is unclear whether he thought such facilities were

a dening criterion of redistribution as opposed to market

systems (Stark and Garraty 2010, 41). This criterion of large

storage facilities was later examined by Sjberg (2004) and

was found to be lacking in the Argolid. For a reassessment of

the role of redistribution in the Aegean Bronze Age, see the

contributions in Galaty et al. 2011, esp. Nakassis et al. 2011;

Pullen 2011.

36

Sjberg 2004, 144.

37

E.g., Burns 2010b.

38

Some 25 ago, Morris (1986) addressed the issue of the

dominance of the redistribution model in Late Bronze Age

archaeology and the possibility of other modes of exchange,

specically markets. She focused on Nichoria, not Pylosas

of course Aprile (2013) also does. Morris, in a foreshadowing

of Hirths (1998) regional distribution model, concluded that

local and regional consumption patterns would reect mar-

ket and other forms of exchange, not the redistribution that

would characterize the palatial center of Pylos. Unfortunately,

her study languished for years, ignored by most scholars.

39

Feinman and Garraty 2010; Garraty and Stark 2010.

Much of the literature on Mesoamerican markets seems to

focus on the identication of marketplaces per se (e.g., Shaw

2012).

40

Hruby 2013.

41

See Thomas (2005, 53637) for discussion of ceramic ves-

sel breakage and replacement rates.

42

Whitelaw (2001, 645), in his discussion of palatial in-

volvement in ceramic production in Late Bronze Age Mes-

senia, estimates 50100 vessels per household per annum for

a replacement rate; a polity the size of Messenia, with an es-

timated population of 12,500 households, would therefore

need 612,5001,225,000 ceramic vessels per year. Consump-

tion by the palace, Whitelaw suggests, constituted no more

than 12% of this total, though the palace still remained the

single largest consumer.

43

Stark and Garraty (2010, 434) also conclude that prod-

ucts such as ceramics, produced by a few specialists, could not

have been effectively supplied through redistribution.

DANIEL J. PULLEN 442 [AJA 117

Tsoungiza would emulate. Thomas, though, points out

that subtle differences in painting particular motifs on

the most common shapes is highly reminiscent of how

high-volume manufacturers in modern economies pro-

duce masses of similar, yet subtly differentiated, prod-

ucts to meet a paradoxical desire for both individuality

and commonality,

44

suggesting an interest in meeting

the demands of the market.

There are two sets of Late Bronze Age material

culture independent of ceramics that I believe point

to the existence of market exchange, if not markets

themselves. The first set comprises the weights and

measures present in a wide variety of contexts, both

palatial and nonpalatial.

45

The topic of weights in it-

self is a large one, but suffice it to say that systems of

weights surely indicate the establishment of equiva-

lent values for commodities, whether for market ex-

change or reciprocal exchange. Halstead noted that

the payment of some tax assessments on individual

subcenters, as recorded in the Pylos tablets, of small

and indivisible commodities such as oxhides would

have been impracticable without some sort of prior

exchange in different commodities among liable tax-

payers.

46

The instances of purchases by the Pylos

palace of linen textiles and alum would have neces-

sitated the establishment of equivalences for the ex-

change to take place.

47

The second set is the Late Bronze Age road systems,

best known in the Argolid. One criterion character-

izing market systems is the construction of facilities

for exchange to take place or the construction or

establishment of ways to facilitate exchanges.

48

The

Argolid road system would be ideal for transporting

agricultural products, raw materials, and finished craft

products among the various communities and centers,

as Sjberg notes.

49

Some of these roads run to or near

Mycenae; some converge on Tiryns and Midea. The

evidence for the roads beyond the Argolid is paltry, but

that has not prevented some from positing that they

were intended to connect the far-flung corners of a

state centered on Mycenae.

50

Jansen, however, suggests

that a number of these roads were for local circulation

and connected areas of agricultural production with

the urban centers.

51

Sjberg extends this suggestion to

argue that the roads facilitated horizontal integration

in the Argolid, thus linking communities beyond the

local neighbors in horizontal arrangements, perhaps

in the periodic markets that are so common through-

out the world.

52

One can easily imagine the local elites

involved in these markets providing a means of verti-

cal integration between the common households of

the countryside and the palatial centers.

This is where Nakassis work on the multiple roles

played by actors in the Late Bronze Age economy helps

explain how this integration might work.

53

Nakassis

demonstrates that individuals named in the Linear B

tablets at Pylos often recur in different contexts, sug-

gesting that an individual could be involved in more

than one role in the Pylian political economy. Some

roles seem to be directly associated with the palace,

while other roles seem to be associated with the re-

gions, district capitals, and other places outside the

palace. This implies that individual actors operated at

multiple levels within the hierarchy of the Pylian state.

While we have cautioned against assuming similar pat-

terns among the Late Bronze Age states without direct

evidence, in this instance the assumption of multiple

roles played by an individual is well grounded in an-

thropological theory of the social persona. Indeed,

it would be surprising to find that individuals do not

play multiple roles in their interactions with others. It

is likely, then, that local elites, interacting occasionally

with the palace centers, also interacted with individuals

in their own communities; in economic interactions,

this would have involved market exchange. One of

the characteristics of markets is how they facilitate the

horizontal integration of many actors as well as pro-

vide opportunity for relationships to emerge between

actors at different levels.

In the model of craft production and distribu-

tion advocated here, the owner of the Petsas House

ceramic workshop would play (at least) two roles in

the political economy of the Mycenae polity. As part

of the elite with palatial ties, he would be obligated

to provide the palace with certain quantities of ce-

ramic vessels, perhaps receiving in return landthe

large, well-appointed Petsas House indicates a wealthy

owner. This type of transaction would perhaps be re-

corded in the palace archives. Production of ceramic

vessels beyond the needs of the palace would be dis-

tributed through other mechanisms, including mar-

ket exchange, whether at Mycenae itself or in one of

44

Thomas 2005, 540.

45

Halstead 1992, 72; Sjberg 2004, 17.

46

Halstead 1992, 72.

47

Halstead 1992, 71; see also Hruby 2013.

48

Hruby (2013) suggests a similar motive behind the con-

struction of the articial harbor in Messenia; see also Zang-

ger 2008.

49

Sjberg 2004, 144.

50

E.g., Hope Simpson 1998.

51

Jansen 2002.

52

Supra n. 49.

53

Nakassis 2006, (forthcoming).

EXCHANGING THE MYCENAEAN ECONOMY 2013] 443

the communities easily reached via the extensive road

system. The Petsas House ceramics merchant, then,

would serve to integrate vertically the communities

around Mycenae with the palatial center.

There are many dimensions to the study of mar-

kets that cannot be examined here, such as the scale

of markets and market exchange, the periodicity or

regularity of markets, or the presence of physical

marketplaces. But by way of conclusion, I would like

to speculate about exchange after the palaces col-

lapsed. There seems to have been a shift in the LH

IIIC period to small workshops that strove to produce

items for marking prestige and status, and items of

exotic origin or heirlooms seem to have increased in

significance to their owners,

54

since monumental ar-

chitecture and tombs had gone out of existence. With

the palace-centered redistributive component of the

political economy removed, this freed individuals to

pursue alternate modes of obtaining goods, such as

the market. Perhaps those local elites who had already

established local authority after the collapse of the pal-

aces found it necessary to manipulate the market, and

not the palatial redistributive system, to maintain their

power. Tiryns and Asine in the LH IIIC period fit this

model. This new reliance on market exchange as the

main mode for economic transactions among elites and

nonelites set the stage for the eventual appearance of

marketplaces such as the Athenian Agora, where one

found everything sold together.

55

department of classics

florida state university

tallahassee, florida 32306-1510

dpullen@fsu.edu

Works Cited

kerstrm, . 1968. A Mycenaean Potters Factory at

Berbati near Mycenae. In Atti e Memorie del I Congresso

Internazionale di Micenologia, Roma, 27 settembre3 ottobre

1967, 4853. Incunabula Graeca 25. Rome: Edizioni

dellAteneo.

Aprile, J.D. 2013. The New Political Economy of Nicho-

ria: Using Intrasite Distributional Data to Investigate

Regional Institutions. AJA 117(3):42936.

Bintliff, J.L. 1977. Natural Environment and Human Settle-

ment in Prehistoric Greece. BAR Suppl. 28. 2 vols. Oxford:

British Archaeological Reports.

Blegen, C.W. 1921. Korakou: A Prehistoric Settlement near

Corinth. Boston: American School of Classical Studies

at Athens.

. 1928. Zygouries: A Prehistoric Settlement in the Valley

of Cleonae. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press,

for the American School of Classical Studies at Athens.

Burns, B.E. 2010a. Mycenaean Greece, Mediterranean Com-

merce, and the Formation of Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

. 2010b. Trade. In The Oxford Handbook of the Bronze

Age Aegean, edited by E.H. Cline, 291304. Oxford: Ox-

ford University Press.

Cherry, J.F. 1986. Polities and Palaces: Some Problems

in Minoan State Formation. In Peer Polity Interaction

and Socio-Political Change, edited by C. Renfrew and J.F.

Cherry, 1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dabney, M.K. 1997. Craft Product Consumption as an

Economic Indicator of Site Status in Regional Studies.

In TEXNH: Craftsmen, Craftswomen, and Craftsmanship in

the Aegean Bronze Age. Proceedings of the 6th International

Aegean Conference, Philadelphia, 1821 April 1996, edited

by R. Laffineur and P.P. Betancourt. Vol. 2, 46771.

Aegaeum 16. Lige and Austin: Universit de Lige and

University of Texas at Austin.

Dickinson, O.T.P.K. 2006. The Aegean from Bronze Age to Iron

Age: Continuity and Change Between the Twelfth and Eighth

Centuries B.C. London: Routledge.

Feinman, G.M., and C.P. Garraty. 2010. Preindustrial

Markets and Marketing: Archaeological Perspectives.

Annual Review of Anthropology 39:16791.

Finley, M.I. 1973. The Ancient Economy. Sather Classical

Lectures 43. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Fitzsimons, R.D. 2006. Monuments of Power and the

Power of Monuments: The Evolution of Elite Architec-

tural Styles at Bronze Age Mycenae. Ph.D. diss., Univer-

sity of Cincinnati.

Frdin, O., and A.W. Persson. 1938. Asine: Results of the Swed-

ish Excavations, 19221930. Stockholm: Generalstabens

Litografiska Anstalts F rlag.

Galaty, M.L. 2010. Wedging Clay: Combining Competing

Models of Mycenaean Pottery Industries. In Political

Economies of the Aegean Bronze Age: Papers from the Langford

Conference, Florida State University, Tallahassee, 2224 Febru-

ary 2007, edited by D.J. Pullen, 23047. Oxford: Oxbow.

Galaty, M.L., and W.A. Parkinson. 2007. Mycenaean Pal-

aces Rethought. In Rethinking Mycenaean Palaces II. 2nd

rev. ed., edited by M.L. Galaty and W.A. Parkinson, 117.

Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Monograph 60. Los

Angeles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology.

Galaty, M.L., D. Nakassis, and W.A. Parkinson, eds. 2011.

Redistribution in Aegean Palatial Societies. AJA 115(2):

175244.

Garraty, C.P., and B.L. Stark, eds. 2010. Archaeological Ap-

proaches to Market Exchange in Ancient Societies. Boulder:

University Press of Colorado.

Halstead, P. 1992. The Mycenaean Palatial Economy: Mak-

ing the Most of the Gaps in the Evidence. PCPS 38:5786.

. 2007. Toward a Model of Mycenaean Palatial Mo-

bilization. In Rethinking Mycenaean Palaces II. 2nd rev.

ed., edited by M.L. Galaty and W.A. Parkinson, 6673.

Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Monograph 60. Los An-

geles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology.

Hirth, K.G. 1998. The Distributional Approach: A New

54

Dickinson 2006, 72.

55

Ath. 14.640bc.

D.J. PULLEN, EXCHANGING THE MYCENAEAN ECONOMY 444

Way to Identify Marketplace Exchange in the Archaeo-

logical Record. CurrAnthr 39:45167.

Hope Simpson, R. 1998. The Mycenaean Highways. Ech-

Cl 42, n.s. 17:23960.

Hruby, J. 2013. The Palace of Nestor, Craft Production,

and Mechanisms for the Transfer of Goods. AJA 117

(3):42327.

Jansen, A.G. 2002. A Study of the Remains of Mycenaean Roads

and Stations of Bronze-Age Greece. Mellen Studies in Archae-

ology 1. Lewiston, Me.: Edwin Mellen Press.

Kilian, K. 1988. The Emergence of Wanax Ideology in the

Mycenaean Palaces. OJA 7:291302.

Mommsen, H., T. Beier, and A. Hein. 2002. A Complete

Chemical Grouping of the Berkeley Neutron Activation

Analysis Data on Mycenaean Pottery. JAS 29:61337.

Morris, H.J. 1986. An Economic Model of the Late My-

cenaean Kingdom of Pylos. Ph.D. diss., University of

Minnesota.

Nakassis, D. 2006. The Individual and the Mycenaean

State: Agency and Prosopography in the Linear B Texts

from Pylos. Ph.D. diss., University of Texas at Austin.

. 2010. Reevaluating Staple and Wealth Finance

at Mycenaean Pylos. In Political Economies of the Aegean

Bronze Age: Papers from the Langford Conference, Florida

State University, Tallahassee, 2224 February 2007, edited

by D.J. Pullen, 12748. Oxford: Oxbow.

. Forthcoming. Individuals and Society in Mycenaean

Pylos. Mnemosyne Suppl., History and Archaeology of

Classical Antiquity 358. Leiden and Boston: Brill.

Nakassis, D., M.L. Galaty, and W.A. Parkinson. 2010. State

and Society. In The Oxford Handbook of the Bronze Age

Aegean, edited by E.H. Cline, 23950. Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

Nakassis, D., W.A. Parkinson, and M.L. Galaty. 2011. Re-

distributive Economies from a Theoretical and Cross-

Cultural Perspective. AJA 115(2):17784.

Nelson, M.C. 2001. The Architecture of Epano Englianos,

Greece. Ph.D. diss., University of Toronto.

Parkinson, W.A. 2007. Chipping Away at the Mycenaean

Economy: Obsidian Exchange, Linear B, and Palatial

Control in Late Bronze Age Messenia. In Rethinking

Mycenaean Palaces II. 2nd rev. ed., edited by M.L. Galaty

and W.A. Parkinson, 87101. Cotsen Institute of Archae-

ology Monograph 60. Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute of

Archaeology.

. 2010. Beyond the Peer: Social Interaction and Po-

litical Evolution in the Bronze Age Aegean. In Political

Economies of the Aegean Bronze Age, Papers from the Langford

Conference, Florida State University, Tallahassee, 2224 Febru-

ary 2007, edited by D.J. Pullen, 1134. Oxford: Oxbow.

Parkinson, W.A., and M.L. Galaty. 2007. Secondary States

in Perspective: An Integrated Approach to State Forma-

tion in the Prehistoric Aegean. American Anthropologist

109:11329.

Parkinson, W.A., and D.J. Pullen. Forthcoming. The Emer-

gence of Craft Specialization on the Greek Mainland.

In KE-RA-ME-JA: Studies Presented to Cynthia Shelmerdine,

edited by D. Nakassis, J. Gulizio, and S.A. James. Phila-

delphia: INSTAP Academic Press.

Parkinson, W.A., D. Nakassis, and M.L. Galaty. 2013. Crafts,

Specialists, and Markets in Mycenaean Greece: Intro-

duction. AJA 117(3):41322.

Polanyi, K. 1968. Primitive, Archaic, and Modern Economies:

Essays of Karl Polanyi. Edited by G. Dalton. Boston: Bea-

con Press.

Pullen, D.J., ed. 2010a. Political Economies of the Aegean Bronze

Age: Papers from the Langford Conference, Florida State Uni-

versity, Tallahassee, 2224 February 2007. Oxford: Oxbow.

. 2010b. Introduction: Political Economies of the

Aegean Bronze Age. In Political Economies of the Aegean

Bronze Age: Papers from the Langford Conference, Florida State

University, Tallahassee, 2224 February 2007, edited by D.J.

Pullen, 110. Oxford: Oxbow.

. 2011. Before the Palaces: Redistribution and Chief-

doms in Mainland Greece. AJA 115(2):18595.

Pullen, D.J., and T.F. Tartaron. 2007. Wheres the Palace?

The Absence of State Formation in the Late Bronze Age

Corinthia. In Rethinking Mycenaean Palaces II. 2nd rev.

ed., edited by M.L. Galaty and W.A. Parkinson, 14658.

Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Monograph 60. Los An-

geles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology.

Renfrew, C. 1975. Trade as Action at a Distance: Ques-

tions of Integration and Communication. In Ancient

Civilizations and Trade, edited by J.A. Sabloff and C.C.

Lamberg-Karlovsky, 359. Albuquerque: University of

New Mexico Press.

. 1986. Introduction: Peer Polity Interaction and

Socio-Political Change. In Peer Polity Interaction and So-

cio-Political Change, edited by C. Renfrew and J.F. Cherry,

118. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schallin, A.-L. 2002. Pots for Sale: The Late Helladic IIIA

and IIIB Ceramic Production at Berbati. In New Research

on Old Material from Asine and Berbati in Celebration of the

Fiftieth Anniversary of the Swedish Institute at Athens, edited

by B. Wells, 14155. ActaAth 8, 17. Stockholm: Svenska

Institutet i Athen.

Shaw, L.C. 2012. The Elusive Maya Marketplace: An Ar-

chaeological Consideration of the Evidence. Journal of

Archaeological Research 20:11755.

Shelmerdine, C.W., and J. Bennet. 2008. Mycenaean States:

Economy and Administration. In The Cambridge Com-

panion to the Aegean Bronze Age, edited by C.W. Shelmer-

dine, 289309. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Shelton, K. 20022003. A New Linear B Tablet from Pet-

sas House, Mycenae. Minos 3738:38796.

. 2010. Citadel and Settlement: A Developing Econ-

omy at Mycenae, the Case of Petsas House. In Political

Economies of the Aegean Bronze Age: Papers from the Langford

Conference, Florida State University, Tallahassee, 2224 Febru-

ary 2007, edited by D.J. Pullen, 184204. Oxford: Oxbow.

Sherratt, E.S. 1982. Patterns of Contact: Manufacture and

Distribution of Mycenaean Pottery, 14001100. In Inter-

action and Acculturation in the Mediterranean: Proceedings of

the Second International Congress of Mediterranean Pre- and

Protohistory, Amsterdam, 1923 November 1980, edited by

J. Best and N. Devries, 17779. Amsterdam.

Sjberg, B.L. 2004. Asine and the Argolid in the Late Helladic

III Period: A Socio-Economic Study. BAR-IS 1225. Oxford:

Archaeopress.

Stark, B.L., and C.P. Garraty. 2010. Detecting Marketplace

Exchange in Archaeology: A Methodological Review.

In Archaeological Approaches to Market Exchange in Ancient

Societies, edited by C.P. Garraty and B.L. Stark, 3358.

Boulder: University of Colorado Press.

Tartaron, T.F., D.J. Pullen, R.K. Dunn, L. Tzortzopoulou-

Gregory, A. Dill, and J.I. Boyce. 2011. The Saronic

Harbors Archaeological Research Project (SHARP):

Investigations at Mycenaean Kalamianos, 20072009.

Hesperia 80:559634.

Thomas, P.M. 1992. LH IIIB:1 Pottery from Tsoungiza

EXCHANGING THE MYCENAEAN ECONOMY 2013] 445

and Zygouries. Ph.D. diss., University of North Caro-

lina at Chapel Hill.

. 2005. A Deposit of Late Helladic IIIB1 Pottery

from Tsoungiza. Hesperia 74:451573.

Voutsaki, S. 2010a. Argolid. In The Oxford Handbook of the

Bronze Age Aegean, edited by E.H. Cline, 599613. Oxford:

Oxford University Press.

. 2010b. From the Kinship Economy to the Palatial

Economy: The Argolid in the Second Millennium BC.

In Political Economies of the Aegean Bronze Age: Papers from

the Langford Conference, Florida State University, Tallahas-

see, 2224 February 2007, edited by D.J. Pullen, 86111.

Oxford: Oxbow.

Walberg, G. 2007. Midea: The Megaron Complex and Shrine

Area. Excavations on the Lower Terraces, 19941997. Pre-

history Monographs 20. Philadelphia: INSTAP Aca-

demic Press.

Whitelaw, T.M. 2001. Reading Between the Tablets: As-

sessing Mycenaean Palatial Involvement in Ceramic

Production and Consumption. In Economy and Politics

in the Mycenaean Palace States: Proceedings of a Conference

Held on 13 July 1999 in the Faculty of Classics, Cambridge,

edited by S. Voutsaki and J.T. Killen, 5179. Cambridge

Philological Society Suppl. 27. Cambridge: Cambridge

Philological Society.

Wright, J.C., J.F. Cherry, J.L. Davis, E.E. Mantzourani, S.B.

Sutton, and R.F. Sutton. 1990. The Nemea Valley Ar-

chaeological Project: A Preliminary Report. Hesperia

59:579659.

Zangger, E. 2008. The Port of Nestor. In Sandy Pylos: An

Archaeological History from Nestor to Navarino. 2nd ed., ed-

ited by J.L. Davis, 6974. Princeton: American School of

Classical Studies at Athens.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- 1 Redistribution in Aegean Palatial Societies. Introduction. Why RedistributionDocument2 pages1 Redistribution in Aegean Palatial Societies. Introduction. Why RedistributionJorge Cano MorenoPas encore d'évaluation

- Ancient Egypt Before Writing: From Markings to HieroglyphsD'EverandAncient Egypt Before Writing: From Markings to HieroglyphsPas encore d'évaluation

- 3 Before The PalacesDocument11 pages3 Before The PalacesJorge Cano MorenoPas encore d'évaluation

- 3662685Document4 pages3662685Benek ÇınarPas encore d'évaluation

- Neer Athenian Treasury at DelphiDocument36 pagesNeer Athenian Treasury at DelphiMaria Reyes100% (1)

- Neer, Athenian Treasury at DelphiDocument36 pagesNeer, Athenian Treasury at DelphiKaterinaLogotheti100% (1)

- Ahhiyawa and The World of Great Kings A Reevaluation of Mycenaean Political StructuresDocument12 pagesAhhiyawa and The World of Great Kings A Reevaluation of Mycenaean Political StructuresGürkan ErginPas encore d'évaluation

- 2012 Kelder Talanta 44-LibreDocument12 pages2012 Kelder Talanta 44-Librericardo_osoPas encore d'évaluation

- Vlassopoulos, 2007 - The Greek Poleis As Part of A World-SystemDocument21 pagesVlassopoulos, 2007 - The Greek Poleis As Part of A World-SystemGabriel Cabral BernardoPas encore d'évaluation

- Bronze Age Interactions between the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean RevisitedDocument20 pagesBronze Age Interactions between the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean RevisitedthismuskyPas encore d'évaluation

- Representing the anthropomorphic form in the Minoan world: Περιληψεισ Εισηγησεων abstractsDocument74 pagesRepresenting the anthropomorphic form in the Minoan world: Περιληψεισ Εισηγησεων abstractsChristianna FotouPas encore d'évaluation

- Mediterranean Crossroads: Edited by Sophia Antoniadou and Anthony PaceDocument40 pagesMediterranean Crossroads: Edited by Sophia Antoniadou and Anthony PaceJordi Teixidor AbelendaPas encore d'évaluation

- Archaeological Views of Aztec Culture: Mary G. HodgeDocument42 pagesArchaeological Views of Aztec Culture: Mary G. Hodgecicero_csPas encore d'évaluation

- 6 by Apponointment To His Majesty The WanaxDocument9 pages6 by Apponointment To His Majesty The WanaxJorge Cano MorenoPas encore d'évaluation

- Julio Escalona, Orri Vésteinsson and Stuart Brookes (Eds.) : Polity and Neighbourhood in Early Medieval EuropeDocument42 pagesJulio Escalona, Orri Vésteinsson and Stuart Brookes (Eds.) : Polity and Neighbourhood in Early Medieval Europewa undmePas encore d'évaluation

- Bronze Age CollapseDocument9 pagesBronze Age Collapsemark_schwartz_41100% (1)

- Contacts Between Greece and Pannonia in The Early Iron Agewith Special Concern To The Area of ThessalonicaDocument26 pagesContacts Between Greece and Pannonia in The Early Iron Agewith Special Concern To The Area of ThessalonicaMirza Kapetanović100% (1)

- Imperial Surplus and Local Tastes: A Comparative Study of Mediterranean Connectivity and TradeDocument29 pagesImperial Surplus and Local Tastes: A Comparative Study of Mediterranean Connectivity and TradebillcaraherPas encore d'évaluation

- Moreno Pines Maat and Tianxia FinalDocument44 pagesMoreno Pines Maat and Tianxia FinalZhadum QuestPas encore d'évaluation

- Classical Archaeology by Susan E Alcock and Robin OsborneDocument8 pagesClassical Archaeology by Susan E Alcock and Robin Osborneblock_bhs50% (2)

- Egypt at Its Origins 4 - AbstractsDocument44 pagesEgypt at Its Origins 4 - AbstractsLaura GarcíaPas encore d'évaluation

- Halstead From Sharing To Hoarding PDFDocument12 pagesHalstead From Sharing To Hoarding PDFMaria Pap.Andr.Ant.Pas encore d'évaluation

- Aspect of State Formation Processes in Relation To Economical (And Cultural Changes) in Hellenistic BactriaDocument12 pagesAspect of State Formation Processes in Relation To Economical (And Cultural Changes) in Hellenistic BactriaMeilin LuPas encore d'évaluation

- This Content Downloaded From 62.1.171.122 On Wed, 22 Jul 2020 09:58:45 UTCDocument4 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 62.1.171.122 On Wed, 22 Jul 2020 09:58:45 UTCgordianknot2020Pas encore d'évaluation

- Elymeans, Parthians, and The Evolution of Empires in Southwestern IranDocument14 pagesElymeans, Parthians, and The Evolution of Empires in Southwestern IranCANELO_PIANOPas encore d'évaluation

- Nol 2021 Defining Cities and Non Cities Through Emic and Etic Perspectives A Case Study From Israel Palestine DuringDocument28 pagesNol 2021 Defining Cities and Non Cities Through Emic and Etic Perspectives A Case Study From Israel Palestine Duringarheo111Pas encore d'évaluation

- State and Society in the Bronze Age AegeanDocument14 pagesState and Society in the Bronze Age AegeanSteven melvin williamPas encore d'évaluation

- Purcell Pallas 90 2012Document15 pagesPurcell Pallas 90 2012Giovan NascimentoPas encore d'évaluation

- Hellenising' The Cypriot Goddess'Document16 pagesHellenising' The Cypriot Goddess'Paula Pieprzyca100% (1)

- Article - Maritime Commerce and Geographies of Mobility in The Late Bronze Age of The Eastern MediterrDocument45 pagesArticle - Maritime Commerce and Geographies of Mobility in The Late Bronze Age of The Eastern MediterrRebeca Fermandez PuertaPas encore d'évaluation

- Stein 2005. The Archeology of Colonial Encounters PDFDocument29 pagesStein 2005. The Archeology of Colonial Encounters PDFNelly GracielaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Collapse and Regeneration of Complex Society in Greece 1500-500Document15 pagesThe Collapse and Regeneration of Complex Society in Greece 1500-500Angelo_ColonnaPas encore d'évaluation

- Angelis - 2006 - Going Against The Grain in Sicilian Greek EconomicDocument19 pagesAngelis - 2006 - Going Against The Grain in Sicilian Greek EconomicphilodemusPas encore d'évaluation

- A Reluctant Servant: Ugarit Under Foreign Rule During The Late Bronze AgeDocument42 pagesA Reluctant Servant: Ugarit Under Foreign Rule During The Late Bronze Agebialas.kamil99Pas encore d'évaluation

- ChaniotisGreatInscriptionGortyn Libre PDFDocument20 pagesChaniotisGreatInscriptionGortyn Libre PDFJesus MccoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Horseshoe Structures for Ancient Greek Funeral RitualsDocument10 pagesHorseshoe Structures for Ancient Greek Funeral RitualsAntoniu Claudiu SirbuPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction Tophet As A Historical Pro PDFDocument8 pagesIntroduction Tophet As A Historical Pro PDFkamy-gPas encore d'évaluation

- Preface: Miltiades B. Hatzopoulos Emphasizes The Value of Historical Geography and EpigraDocument6 pagesPreface: Miltiades B. Hatzopoulos Emphasizes The Value of Historical Geography and EpigraMouhamadAlrifaiiPas encore d'évaluation

- Onno Van Nijf Political Culture TermessosDocument18 pagesOnno Van Nijf Political Culture TermessosOnno100% (2)

- Garcia, Recent Developments in The Social and Economic History of Ancient Egypt PDFDocument31 pagesGarcia, Recent Developments in The Social and Economic History of Ancient Egypt PDFKostas VlassopoulosPas encore d'évaluation

- THOMAS, Carol G. (1995) - The Components of Political Identity in Mycenaean Greece. Aegaeum. 12 349-354.Document6 pagesTHOMAS, Carol G. (1995) - The Components of Political Identity in Mycenaean Greece. Aegaeum. 12 349-354.Daniel BarboLulaPas encore d'évaluation

- Palaima, Thomas G. Sacrificial Feasting in The Linear B Documents.Document31 pagesPalaima, Thomas G. Sacrificial Feasting in The Linear B Documents.Yuki Amaterasu100% (1)

- Osborne R and Cunliffe B MediterraneanDocument4 pagesOsborne R and Cunliffe B MediterraneanСергей ГаврилюкPas encore d'évaluation

- Necipoglu ThessalonikiDocument21 pagesNecipoglu ThessalonikiRadivoje MarinovicPas encore d'évaluation

- The Homonoia Coins of Asia Minor and EphesiansDocument16 pagesThe Homonoia Coins of Asia Minor and EphesiansНеточка НезвановаPas encore d'évaluation

- 4 Redistribution and Political Economies in Broze Age CreteDocument9 pages4 Redistribution and Political Economies in Broze Age CreteJorge Cano MorenoPas encore d'évaluation

- Callimachus Romanus Propertius Love Eleg PDFDocument33 pagesCallimachus Romanus Propertius Love Eleg PDFNéstor ManríquezPas encore d'évaluation

- Dunn 1994, The Transition From Polis To Kastron in The BalkansDocument22 pagesDunn 1994, The Transition From Polis To Kastron in The Balkansvladan stojiljkovicPas encore d'évaluation

- Society of Fellows application writing sample examines hybridity in Hellenistic EastDocument6 pagesSociety of Fellows application writing sample examines hybridity in Hellenistic EastXibalba KimPas encore d'évaluation

- Late Bronze Age Cyprus: Crisis, Colonization, Continuity or HybridizationDocument0 pageLate Bronze Age Cyprus: Crisis, Colonization, Continuity or HybridizationPaula PieprzycaPas encore d'évaluation

- Coinage of The Cilician Cities As A Mirror of Historical and Cultural Changes (V C. Bce - Iii C. Ce)Document23 pagesCoinage of The Cilician Cities As A Mirror of Historical and Cultural Changes (V C. Bce - Iii C. Ce)Артур ДегтярёвPas encore d'évaluation

- Benaissa Rural Settlements of The Oxyrhynchite Nome. A Papyrological SurveyDocument496 pagesBenaissa Rural Settlements of The Oxyrhynchite Nome. A Papyrological Surveymontag2Pas encore d'évaluation

- Linguistic Evidence On The Macedonian Question (By Ioannis Kallianiotis)Document22 pagesLinguistic Evidence On The Macedonian Question (By Ioannis Kallianiotis)Macedonia - The Authentic TruthPas encore d'évaluation

- History_inof_Hellenistic_ThessalyDocument23 pagesHistory_inof_Hellenistic_ThessalyBarbara SilvaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Creation of The Late Antique CityDocument52 pagesThe Creation of The Late Antique CityJavier Martinez EspuñaPas encore d'évaluation

- Dynasty0-Raffaele AH17Document43 pagesDynasty0-Raffaele AH17Assmaa KhaledPas encore d'évaluation

- Herzfeld-Spatial CleansingDocument23 pagesHerzfeld-Spatial CleansingsheyPas encore d'évaluation

- The Archaeology of Ancient State EconomiesDocument31 pagesThe Archaeology of Ancient State EconomiesCyrus BanikazemiPas encore d'évaluation

- Anthony Kurgan HorseDocument24 pagesAnthony Kurgan HorseMuammer İreçPas encore d'évaluation

- Adapted From Adding English, Ch. 9 and Http://Edweb - Sdsu.Edu/People/Jmora/Almmethods - Htm#GrammarDocument1 pageAdapted From Adding English, Ch. 9 and Http://Edweb - Sdsu.Edu/People/Jmora/Almmethods - Htm#GrammarMuammer İreçPas encore d'évaluation

- Marxism Childe Archaeology PDFDocument8 pagesMarxism Childe Archaeology PDFMuammer İreçPas encore d'évaluation

- Glascock and Neff 2004-LibreDocument11 pagesGlascock and Neff 2004-LibreMuammer İreçPas encore d'évaluation

- Georgio UDocument14 pagesGeorgio UMuammer İreçPas encore d'évaluation

- Bachvar Legendary Migrations-LibreDocument53 pagesBachvar Legendary Migrations-LibreMuammer İreçPas encore d'évaluation

- Santorini Antiquity 2003Document14 pagesSantorini Antiquity 2003Muammer İreçPas encore d'évaluation

- Szuchman 09 NUZI18Document14 pagesSzuchman 09 NUZI18Muammer İreçPas encore d'évaluation

- OLA202 MacSweeneyDocument16 pagesOLA202 MacSweeneyMuammer İreçPas encore d'évaluation

- Nodet 2000Document27 pagesNodet 2000Muammer İreçPas encore d'évaluation

- Festschrift Niemeier DriessenFarnouxLangohr LibreDocument12 pagesFestschrift Niemeier DriessenFarnouxLangohr LibreMuammer İreçPas encore d'évaluation

- Greek Culture To 500 BCDocument33 pagesGreek Culture To 500 BCMuammer İreçPas encore d'évaluation

- Emanuel War at Sea Iawc 2013Document45 pagesEmanuel War at Sea Iawc 2013Muammer İreçPas encore d'évaluation

- Reconsidering the Value of Hieroglyphic Luwian Sign *429 and its Implications for Ahhiyawa in CiliciaDocument15 pagesReconsidering the Value of Hieroglyphic Luwian Sign *429 and its Implications for Ahhiyawa in CiliciaMuammer İreçPas encore d'évaluation

- Mycenaean & Dark Age Tombs & Burial PracticesDocument32 pagesMycenaean & Dark Age Tombs & Burial PracticesMuammer İreçPas encore d'évaluation

- Wright 2008b LibreDocument12 pagesWright 2008b LibreMuammer İreç100% (1)

- European Archaeology Impacted by ColonialismDocument10 pagesEuropean Archaeology Impacted by ColonialismMuammer İreçPas encore d'évaluation

- Devecchi ZA 2010-LibreDocument15 pagesDevecchi ZA 2010-LibreMuammer İreçPas encore d'évaluation

- German Archaeology and Its Relation ToDocument26 pagesGerman Archaeology and Its Relation ToMuammer İreçPas encore d'évaluation

- Mommsen Pavuk 2007 Studia Troica 17-LibreDocument20 pagesMommsen Pavuk 2007 Studia Troica 17-LibreMuammer İreçPas encore d'évaluation

- Bachvar Legendary Migrations-LibreDocument53 pagesBachvar Legendary Migrations-LibreMuammer İreçPas encore d'évaluation

- Marx Childe Trigger-LibreDocument19 pagesMarx Childe Trigger-LibreMuammer İreçPas encore d'évaluation

- CL 244 Shaft GraveDocument31 pagesCL 244 Shaft GraveMuammer İreçPas encore d'évaluation

- Voutsaki-Creation of ValueDocument19 pagesVoutsaki-Creation of ValueMuammer İreçPas encore d'évaluation

- Mycenaean TradeDocument25 pagesMycenaean TradeMuammer İreçPas encore d'évaluation

- ARCH0420Lec9 Trojan War&InterconnectionsDocument45 pagesARCH0420Lec9 Trojan War&InterconnectionsMuammer İreçPas encore d'évaluation

- Trading in Prehistory and Protohistory: Perspectives From The Eastern Aegean and BeyondDocument37 pagesTrading in Prehistory and Protohistory: Perspectives From The Eastern Aegean and BeyondMuammer İreçPas encore d'évaluation

- Release Final - João GordoDocument2 pagesRelease Final - João GordoHomero JanuncioPas encore d'évaluation

- The Key Game - Ida FinkDocument2 pagesThe Key Game - Ida FinkLydia SheldonPas encore d'évaluation

- Deadly Little Secret Discussion GuideDocument4 pagesDeadly Little Secret Discussion GuideDisney HyperionPas encore d'évaluation

- Humanistica Lovaniensia Vol. 29, 1980 PDFDocument363 pagesHumanistica Lovaniensia Vol. 29, 1980 PDFVetusta MaiestasPas encore d'évaluation

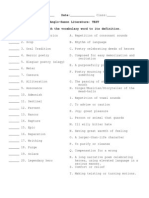

- Anglo-Saxon TestDocument4 pagesAnglo-Saxon Testapi-239793654Pas encore d'évaluation

- Mass Civilization and Minority Culture PressDocument4 pagesMass Civilization and Minority Culture PressEmanuelle SantosPas encore d'évaluation

- Everything About Harry Houdini PDFDocument2 pagesEverything About Harry Houdini PDFAllison0% (1)

- Palaungic PhonologyDocument7 pagesPalaungic Phonologyraubn111Pas encore d'évaluation

- Complete Robert Johnson RecordingsDocument2 pagesComplete Robert Johnson RecordingsBeryl PorterPas encore d'évaluation

- A Complete History of American Comic Books Afterword by Steve GeppiDocument2 pagesA Complete History of American Comic Books Afterword by Steve Geppinita0% (3)

- Bledsoe Unit PlanDocument13 pagesBledsoe Unit PlanSamantha BledsoePas encore d'évaluation

- The Anglo Saxons and The VikingsDocument4 pagesThe Anglo Saxons and The VikingsGIOVANNI CANCELLIPas encore d'évaluation

- Bataille - Human FaceDocument6 pagesBataille - Human Faceod_torrePas encore d'évaluation

- (Slavery and Slaving in World History) Joseph C. Miller - Slavery and Slaving in World History - A Bibliography, 1992-1996. 2-M.E. Sharpe (1998)Document274 pages(Slavery and Slaving in World History) Joseph C. Miller - Slavery and Slaving in World History - A Bibliography, 1992-1996. 2-M.E. Sharpe (1998)Margo AwadPas encore d'évaluation

- Dead StarsDocument27 pagesDead StarsAudrey Kristina Maypa71% (7)

- Malay Annals: 1 Compilation HistoryDocument5 pagesMalay Annals: 1 Compilation HistoryNagentren Subramaniam100% (1)

- Chinook - A History and DictionaryDocument182 pagesChinook - A History and DictionarysjheissPas encore d'évaluation

- Native Americans - 16th To 17th Century ImagesDocument89 pagesNative Americans - 16th To 17th Century ImagesThe 18th Century Material Culture Resource Center100% (9)

- CityInAmericanCulture Bibliography 1Document4 pagesCityInAmericanCulture Bibliography 1Anonymous FHCJucPas encore d'évaluation

- Ivan SilenDocument8 pagesIvan SilenElena GerashchenkoPas encore d'évaluation

- Surrealism in 20th-Century Russian PoetryDocument14 pagesSurrealism in 20th-Century Russian PoetryJillian TehPas encore d'évaluation

- Types of Primary SourcesDocument3 pagesTypes of Primary SourcesZyrhiemae Kyle EhnzoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Routledge Handbook To Nineteenth-Century British Periodicals Andd Newspapers PDFDocument74 pagesThe Routledge Handbook To Nineteenth-Century British Periodicals Andd Newspapers PDFEva AngeliniPas encore d'évaluation

- Arthur & The Anglo-Saxon Wars PDFDocument17 pagesArthur & The Anglo-Saxon Wars PDFatcho75100% (2)

- Deis Equeunubo - The Divine Twins in AstDocument14 pagesDeis Equeunubo - The Divine Twins in AstCristobo CarrínPas encore d'évaluation

- Book March 2015EBOOKDocument25 pagesBook March 2015EBOOKmiller999Pas encore d'évaluation

- Prehistoric ArtDocument4 pagesPrehistoric ArtParkAeRaPas encore d'évaluation

- MUS 2 Referencing SystemDocument4 pagesMUS 2 Referencing SystemJuan Sebastian CorreaPas encore d'évaluation

- Miscellanea: Arab-Sasanian Copper P Esents Varie Ypo OgyDocument24 pagesMiscellanea: Arab-Sasanian Copper P Esents Varie Ypo Ogy12chainsPas encore d'évaluation

- Michael F. Suarez S.J., H. R. Woudhuysen-The Book - A Global History-Oxford University Press (2014)Document769 pagesMichael F. Suarez S.J., H. R. Woudhuysen-The Book - A Global History-Oxford University Press (2014)Diana Paola Guzmán Méndez100% (6)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityD'EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (13)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityD'EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2)

- The Body Is Not an Apology, Second Edition: The Power of Radical Self-LoveD'EverandThe Body Is Not an Apology, Second Edition: The Power of Radical Self-LoveÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (365)

- Cult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryD'EverandCult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (44)

- Prisoners of Geography: Ten Maps That Explain Everything About the WorldD'EverandPrisoners of Geography: Ten Maps That Explain Everything About the WorldÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (1143)

- Briefly Perfectly Human: Making an Authentic Life by Getting Real About the EndD'EverandBriefly Perfectly Human: Making an Authentic Life by Getting Real About the EndPas encore d'évaluation

- If I Did It: Confessions of the KillerD'EverandIf I Did It: Confessions of the KillerÉvaluation : 3 sur 5 étoiles3/5 (132)

- Selling the Dream: The Billion-Dollar Industry Bankrupting AmericansD'EverandSelling the Dream: The Billion-Dollar Industry Bankrupting AmericansÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (17)

- 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed: Revised and UpdatedD'Everand1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed: Revised and UpdatedÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (109)

- Troubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social ClassD'EverandTroubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social ClassÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (23)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.D'EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (110)

- The Exvangelicals: Loving, Living, and Leaving the White Evangelical ChurchD'EverandThe Exvangelicals: Loving, Living, and Leaving the White Evangelical ChurchÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (12)

- His Needs, Her Needs: Building a Marriage That LastsD'EverandHis Needs, Her Needs: Building a Marriage That LastsÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (99)

- The Wicked and the Willing: An F/F Gothic Horror Vampire NovelD'EverandThe Wicked and the Willing: An F/F Gothic Horror Vampire NovelÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (20)

- Hey, Hun: Sales, Sisterhood, Supremacy, and the Other Lies Behind Multilevel MarketingD'EverandHey, Hun: Sales, Sisterhood, Supremacy, and the Other Lies Behind Multilevel MarketingÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (102)

- Dark Psychology: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Manipulation Using Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Mind Control, Subliminal Persuasion, Hypnosis, and Speed Reading Techniques.D'EverandDark Psychology: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Manipulation Using Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Mind Control, Subliminal Persuasion, Hypnosis, and Speed Reading Techniques.Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (88)

- Crypt: Life, Death and Disease in the Middle Ages and BeyondD'EverandCrypt: Life, Death and Disease in the Middle Ages and BeyondÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (3)

- Viral Justice: How We Grow the World We WantD'EverandViral Justice: How We Grow the World We WantÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (11)

- Little Princes: One Man's Promise to Bring Home the Lost Children of NepalD'EverandLittle Princes: One Man's Promise to Bring Home the Lost Children of NepalPas encore d'évaluation

- For the Love of Men: From Toxic to a More Mindful MasculinityD'EverandFor the Love of Men: From Toxic to a More Mindful MasculinityÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (56)

- The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America's Great MigrationD'EverandThe Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America's Great MigrationÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (1568)

- The Perfection Trap: Embracing the Power of Good EnoughD'EverandThe Perfection Trap: Embracing the Power of Good EnoughÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (24)

- American Jezebel: The Uncommon Life of Anne Hutchinson, the Woman Who Defied the PuritansD'EverandAmerican Jezebel: The Uncommon Life of Anne Hutchinson, the Woman Who Defied the PuritansÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (66)

- Double Lives: True Tales of the Criminals Next DoorD'EverandDouble Lives: True Tales of the Criminals Next DoorÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (34)