Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

ASSESS and ASSIST - Capacity Building For ALL Teachers of Students

Transféré par

Ricardo LizanaDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

ASSESS and ASSIST - Capacity Building For ALL Teachers of Students

Transféré par

Ricardo LizanaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Australian Council for Educational Research

ACEReSearch

Student Learning Processes Teaching and Learning and Leadership

9-1-2007

ASSESS and ASSIST: Capacity building for ALL

teachers of students with and without learning

difculties

Ken Rowe

ACER

Follow this and additional works at: htp://research.acer.edu.au/learning_processes

Part of the Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Research Commons

Tis Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Teaching and Learning and Leadership at ACEReSearch. It has been accepted for

inclusion in Student Learning Processes by an authorized administrator of ACEReSearch. For more information, please contact

mcdowell@acer.edu.au.

Recommended Citation

Rowe, Ken, "ASSESS and ASSIST: Capacity building for ALL teachers of students with and

without learning difculties" (2007).

htp://research.acer.edu.au/learning_processes/7

ASESS and ASSIST 1 K.J . Rowe

_____________________________________________________________________________________

ASSESS and ASSIST: Capacity building for ALL teachers of

students with and without learning difficulties

Ken Rowe

Australian Council for Educational Research

Background paper to keynote address presented at the

Combined LDA, RSTAQ & SPELD Associations Conference

1

Brisbane Convention & Exhibition Centre, 21-22 September 2007

Abstract: Following a brief discussion of the fundamental importance of monitoring growth,

this paper draws from emerging findings from evidence-based research and state-of-the art

practice in assessment and reporting of students developmental and learning progress whether

or not students experience learning difficulties. The monitoring of individual progress over time

requires both diagnostic and developmental assessments of such progress on well-constructed

scales (or maps) that are qualitatively described. The use of such maps enables early

detection of potential risk factors, and the monitoring of both individuals and groups across the

years of schooling. Such maps and their reporting products constitute major aids in: (a) the

integration of assessment into the teaching and learning cycle, (b) assisting children and

adolescents to take ownership of their learning and achievement progress, and (c)

communicating with parents and other interested stakeholders. The paper concludes by arguing

that since teachers are the most valuable resource available to any school, there is a crucial need

for capacity building in teacher professionalism in terms of what teachers should know and be

able to do. These include: (1) knowledge gained from quality assessment, and (2) teaching

practices that are demonstrably effective in assisting ALL students to grow, informed by

findings from evidence-based research.

Introductory comments

In the context of schooling especially during the early and middle years the word assessment

invariably invokes mixed reactions (Rowe, 2006a). On the one hand, for many educators who

fail to understand the essential interdependence of assessment and pedagogy (see Westwood,

2000, 2001, 2005), the term assessment conjures negative notions of testing, labelling and

categorisation that are claimed to have potentially deleterious effects on childrens self-esteem

and their on-going engagement in learning. On the other hand, it is important to note that

teachers assess students continuously and intuitively by observation, interaction, questioning,

directing, evaluating and supporting students in the process of teaching and learning (Rowe &

Hill, 1996). In this regard, Nuttall (1986, p. 1) has made the commonsense observation that:

In one guise, assessment of educational achievement is an integral part of teaching, though most

assessment is carried out informally through questions and answers in class, through

observation of students at work rather than through the formal and means of tests and

examinations.

Further, Nitko (1995) coined the term formative continuous assessment that ...provides a

teacher and the students with information that guides learning from day-to-day (p. 326). Nitko

also made a useful distinction between formative and summative assessment as follows:

What distinguishes formative from summative techniques, however, is not their formal or

informal nature. Rather the distinction lies in the purposes for which the results are used:

formative continuous assessments focus on monitoring and guiding student progress through the

curriculum. Formative continuous assessments primarily serve purposes such as: (a) identifying a

students learning problems on a daily and timely basis; and (b) giving feedback to a student

about his or her learning (Nitko, 1995, p. 328).

1

Correspondence related to this paper should be directed to: Dr Ken Rowe, Research Director Learning

Processes Research Program, Australian Council for Educational Research, Private Bag 55,

Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia; Email: rowek@acer.edu.au.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Combined RSTAQ & LDA Associations Conference: 21-22 September 2007

ASESS and ASSIST 2 K.J . Rowe

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Torrence and Pryor (1995) made a similar distinction between what they termed divergent and

convergent teacher assessment. More recently, in making the case for formative assessment, a

recent OECD report asserts:

Formative assessment refers to frequent, interactive assessments of student progress and

understanding to identify learning needs and adjust teaching appropriately (OECD, 2005, p.21).

As experienced teachers consistently affirm, this formative, analytical and intuitive

assessment constitutes one of the most powerful influences on the promotion of students

educational growth and development (Black & William, 1998; OECD, 2005; Rowe, 2005,

2007a; Rowe & Hill, 1996). Moreover, each of these methods of assessment provides an

opportunity to observe students learning behaviours that can be used both diagnostically and

developmentally as indicators of learning progress, and provide invaluable information for

intervention purposes especially for students experiencing learning difficulties. However,

each indicator (on its own), provides only a small part of the overall picture of learning and

development (Rowe, 2002). At this point, a brief discussion of the fundamental notion of

growth in monitoring students learning development is helpful.

The fundamental notion of growth

2

No concept is more central to the concerns of both parents and teachers than the concept of

growth. As parents and educators we use many different terms to describe physical, cognitive,

affective and behavioural growth, including development, learning, progress and improvement.

However it is described, the concept of individual growth lies at the heart of teachers

professional work. It underpins our efforts to assist learners to move from where they are to

where they could be: to develop higher levels of literacy competence, broader behavioural and

social skills, more advanced problem solving skills, and greater respect for the rights of others.

Closely linked to the concept of individual growth is our fundamental belief that all children

and adolescents are capable of progressing beyond their current levels of development and

attainment including those with developmental and learning difficulties. As educators we

understand that students of the same age are at different stages in their learning and

development, and are progressing at different rates. Nonetheless, we share a belief that every

student is on a path of learning development. The challenge is to understand each learners

current level of progress and to provide opportunities likely to facilitate further growth, and to

minimise the influence of factors that may impede such growth particularly during the early

and middle years of schooling.

A professional commitment to supporting growth requires a deep understanding of growth

itself. What is the nature of progress in an area of learning? What are typical paths and

sequences of child development? What does it mean to grow and improve? What can be

watched for as indicators of progress, and what needs to be done to maximise progress?

Teachers who are focused on supporting and monitoring the long-term growth of individuals

have well-developed understandings of how learning in an area typically advances and of

common obstacles to progress tacit understandings grounded in everyday observations and

experience that may also be informed by theory and research.

3

The assessment and monitoring of developmental progress

Parents are familiar with the percentile growth charts for height and weight that are often used

by developmental paediatricians, as illustrated in Figure 1 below in this case for weight. An

important feature of Figure 1 is that progress is measured against calibrated scales that are

universally defined (i.e., weight in pounds and/or kilograms in this case), based on normative

2

Adapted from Masters, Meiers and Rowe (2003).

3

For a longitudinal, essentially qualitative study of factors affecting childrens educational progress

during the early years of schooling, see: Hill et al. (1998, 2002).

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Combined RSTAQ & LDA Associations Conference: 21-22 September 2007

ASESS and ASSIST 3 K.J . Rowe

_____________________________________________________________________________________

data obtained from population and/or large numbers of children and adolescents. Whereas the

mapping of growth in learning has yet to achieve such precision, major advances in educational

measurement and reporting are encouraging (see: Embretson & Hershberger, 1999; Masters,

1999, 2004a,b; Masters & Keeves, 1999; Masters & Forster, 1996a,b; Wilson, 2005).

Age (Years) Age (Years)

C

a

l

i

b

r

a

t

e

d

w

e

i

g

h

t

s

c

a

l

e

(

g

i

r

l

s

)

Figure 1. A percentile growth chart for weight (females), by age

Monitoring individual learners and their progress over time requires assessments of

childrens progress on similar well-constructed, common, empirical scales (or quantitative

maps) that are qualitatively described. The use of such maps enables the monitoring of both

individuals and groups across the years of schooling (and sometimes beyond). Such maps and

their reporting products (see Figure 2) provide deeper understandings of learning progress than

can be obtained from cross-sectional snap-shots that merely assess the achievements of

students at different ages and/or times. Moreover, the maps are a major aid in monitoring

students progress, as well as communicating with parents and other teachers.

By tracking the same individuals across a number of years it is possible to identify

similarities in learners patterns of learning and achievement. Assessments of these kind show

that, in most areas of school learning, it is possible to identify typical patterns of learning

progress, due in part to natural learning sequences (the fact that some learning inevitably builds

onto and requires earlier learning), but also due to common conventions for sequencing teaching

and learning experiences.

The fact that most students make progress through an area of learning in much the same way

makes group teaching possible. However, not all students learn in precisely the same way, and

some appear to be markedly different in the way they learn. An understanding of typical

patterns of learning facilitates the identification and appreciation of individuals who learn in

uniquely different ways, including those experiencing learning difficulties.

Based on the notion of developmental assessment, a map of typical progress through an

area of learning provides a useful framework for measuring, describing and monitoring growth

over time at the individual and group levels, as illustrated in Figure 2.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Combined RSTAQ & LDA Associations Conference: 21-22 September 2007

ASESS and ASSIST 4 K.J . Rowe

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Longitudinal Literacy and Numeracy Study (LLANS)

Australian Council for Educational Research

LITERACY SCALE DESCRIPTION & NORMATIVE DISTRIBUTIONS

Writes a variety of simple sentences; selects and controls

content of own writing. Listens to a text and infers the reason

for an event without picture clues. Uses full stops and capital

letters to separate sentences. Identifies the purpose of parts

of a text (eg, glossary, caption).

Recognises implied meaning in a short section of a simple

written text. Reads with word-for-word accuracy, an unseen,

illustrated reader with a narrative structure, varied sentences

and a wide range of common vocabulary. Segments and

blends to pronounce unfamiliar words correctly. Spells some

common words with irregular patterns, eg., Basket. Controls

content in writing, eg, selects specific details appropriate to

the piece, or includes some explanations, opinions or

reasons.

Fromown reading or listening, identifies and explains key

events, and follows steps in procedures of a picture story

book and early readers. Reads common words with difficult

spelling patterns, eg, because. Spells some high frequency

words with common patterns. Manipulates sounds in words,

eg, swaps m in smell with p to make spell. J oins simple

sentences using conjunctions

Offers simple explanations for a characters behavior, and

locates explicit details fromown reading or listening to picture

story books. Reads unseen early readers with moderate

accuracy (ie, omissions or substitutions do not consistently

maintain meaning of text. Writes simple sentences that are

mostly readable using phonetically plausible spelling for most

common words. Lists ideas with little elaboration..

After listening to a picture story book, includes several key

aspects in a retelling.

Reads simple common words. Identifies

all the sounds in simple words. Writes one main idea with

mostly recognisable words.

Describes the main idea in an illustration after listening to a

picture story book. Identifies writing and distinguishes words

and letters. Writes a string of letters or scribble.

Reads some very high frequency words. Recognises the same

initial sounds in short words. Writes some recognisable words

with spaces. Communicates some meaning in writing

Describes an event or gives a limited retelling after listening to

a picture story book. Reads a single word label by linking to the

illustration. Names and sounds many letters. Writes own name

correctly.

Locates the front of a picture story book. Identifies a word.

Note: The indicators listed on this side of the scale have been

derived from the tasks completed in the LLANS assessments.

Only a selected sample of these indicators has been used to

describe developing achievement in literacy.

L

L

A

N

S

S

c

a

l

e

o

f

d

e

v

e

l

o

p

i

n

g

l

i

t

e

r

a

c

y

a

c

h

i

e

v

e

m

e

n

t

9Oth%tile

75th%tile

50th%tile

25th%tile

10th%tile

Achievement

of all students

in the study

Mean cohort

achievement

Explains a story complication and resolution in a picture story

book. Links images and text to construct meaning fromown

reading or listening. Reads with word-for-word accuracy, an

unseen, factual early reader with a repetitive structure, varied

content and some support fromillustrations. Spells high

frequency words with a range of patterns. Writes a piece that

shows some overall coherence, eg, a sequence of events or

a detailed list

Angelico Jeffereson

Warra School of Excellence

Figure 2. A growth map of achievement progress in literacy showing individual and

norm-referenced growth against descriptions of domain-referenced criteria

Such maps make explicit what is meant by growth (or progress) and introduces the

possibility of plotting and studying the growth trajectories for both individuals and groups of

learners. For example, Figure 2 illustrates the progress map of literacy learning during the

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Combined RSTAQ & LDA Associations Conference: 21-22 September 2007

ASESS and ASSIST 5 K.J . Rowe

_____________________________________________________________________________________

early years of school developed as part of ACERs Longitudinal Literacy and Numeracy Study

(LLANS).

4

Using modern measurement theory (or more particularly, Rasch measurement),

5

the map

describes how the literacy skills of participating children typically developed over their first few

years of school.

6

Growth in literacy is described on the left of each map, from early skills at the

bottom to more advanced competencies at the top. Moreover, the summary descriptions are

valuable in that they provide a window that opens-up to more detailed information about

what students have achieved (as documented in portfolio records, student diaries, class/school-

based assessments, and so on), as well as providing useful pointers to what has yet to be learnt

and achieved. Similarly, this information is valuable for reporting learning and achievement

progress to relevant stake-holders, namely: students, parents, teachers, schools and system

authorities.

The literacy achievement progress of children in the LLANS study on five occasions is

shown on the right of Figure 2. For example, the map shows that: (a) on average, childrens

literacy skills developed steadily during their first three years of school; and (b) the achievement

progress of Angelico Jefferson indicates less-than-expected progress during the second and third

years of school.

Above all, the administration of the developmental and diagnostic LLANS assessment

instruments provides opportunities for both students and teachers to not only use the constituent

tasks for the assessment of learning, but also for assessment as and for learning. In terms of

assessment as learning, feedback from teachers using the LLANS instruments continues to be

strongly positive to the extent that they as teachers, together with their students, learn a great

deal (see Meiers, Khoo et al., 2006). Likewise, the diagnostic nature of the items provide

teachers and parents with valuable information in terms of assessment for learning by

highlighting strategic pedagogical interventions for individuals and groups at any given point

throughout the achievement distribution and across time. At this point, it is helpful to highlight

key distinctions between two major but contrasting approaches to assessment.

Two contrasting approaches to assessment

Common to most methods of assessment is an emphasis on first specifying what students are

expected to do and then checking to see whether they can. This emphasis has led to two major

but contrasting approaches to assessment.

4

For specific details of this on-going study, see: Meiers (1999a,b, 2000); Meiers and Forster (1999);

Meiers, Khoo et al. (2006); Meiers and Rowe (2002); Stephanou, Meiers and Forster (2000). Note

also, the LLANS assessment instruments were used by Louden et al. (2005a,b).

5

See: Embretson and Hershberger (1999); Masters (1982, 1999, 2004a,b); Masters and Keeves (1999);

Masters and Wright (1997); Rowe (2002, 2005a); Stephanou (2000); Wilson (2005); Wright and Mok

(2000). Note that the unit of measurement for the constructed scale shown in Figure 2 is expressed

in logits. The logit is a unit of measurement derived from the natural logarithm of the odds of an

event, where the odds of that event is defined as the ratio of the probability that the event will occur to

the probability that the event will not occur. A logit scale is used in educational assessment because it

has interval scale properties. That is, if the difficulty of an assessment task (e.g., Task A) is 1.0 logit

greater than the difficulty of Task B, then the odds of a student responding correctly to Task B are 2.7

times the odds of the same student responding correctly to Task A, regardless of whether this student

has high or low ability. Similarly, if the ability of Student A is 1.0 logit greater than the ability of

Student B, then the odds of Student A responding correctly to a task are 2.7 times the odds of Student

B responding correctly to the same task, regardless of task difficulty.

6

Note that the initial sample of 1000 children in their first year of formal schooling was drawn from a

national, randomly-selected sample of 100 government Catholic and independent schools. The

LLANS project is currently in its ninth year, involving assessments of students developing

achievement progress in Literacy and Numeracy throughout the early and middle years of schooling.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Combined RSTAQ & LDA Associations Conference: 21-22 September 2007

ASESS and ASSIST 6 K.J . Rowe

_____________________________________________________________________________________

The first approach is what can be referred to as the can-do, checklist or outcomes-based

model that continues to be strongly influenced by the behavioural objectives, mastery learning

and criterion-referenced testing movements of the 1960s and 1970s (e.g. Glaser, 1963;

Popham, 1978). Characteristic of this first approach is the development of broadly-specified

lists of observable, mostly decontextualised statements of student outcomes. For example, one

of the desired outcomes for Standard 1.0 for Reading of the current Victorian Essential

Learning Standards (VELS), states (inter alia): At Level 1, students match print and spoken

text in their immediate environment. While this approach constitutes a start towards more

explicit specifications of the kinds of knowledge, skills and understandings we might wish to

see students to develop during the early (and later) years of schooling, it is highly unlikely that

...meaningful can/cannot do judgements can be made about broad outcomes of this kind

(Masters, 1994, p. 6). In fact, Noss, Goldstein & Hoyles (1989) have warned: Notions of

decontextualised can-do statements must be strictly meaningless in any criterion-referenced

sense (p. 115).

Even with more explicit specifications of outcome statements and the delineation of

contexts, J essup (1991), Masters (1994, 2004a,b), Noss et al. (1989), Nuttall and Goldstein

(1986), Wolf (1991), among others, have long since warned that the key difficulties confronting

the checklist or can do model is that: (1) the outcome statements are subject to wide variability

in interpretation, (2) are often too loosely defined to ensure comparability, and (3) are unlikely

to provide reliable bases for monitoring student performance standards over time. Further, since

the outcome statements of the VELS kind have not been empirically verified, and are not

calibrated on a common developmental scale, their utility in terms of monitoring achievement

growth is severely limited. A particular concern is that since such statements are not

sufficiently fine-grained, they: (a) lack diagnostic utility, and (b) provide minimal guidance for

subsequent pedagogical intervention and assistance by teachers whether or not students

experience learning difficulties.

Similar limitations apply to most standardised age/grade/stage-appropriate assessment tools.

For example, the six Observation Survey (OS) assessment tasks of Clays (2002) early literacy

achievement constitute stand-alone, age/grade-appropriate assessments that lack recent

concurrent validity estimates.

7

Moreover, the most recent norms are based on a limited sample

of only 796 New Zealand school children (aged 5-7 years).

8

More importantly, the OS tasks

have yet to be calibrated onto a common scale capable of being linked to the State/Territory

monitoring programs for Literacy (and Reading in particular) that begin for students during their

fourth year of formal schooling (i.e., Grade 3 in some jurisdictions and Year 4 in others).

In the context of prevailing national policy agendas for the assessment of students

developmental and learning progress in Years K-2 (or Years 1-3) and Years 3, 5, 7 and 9 (or,

Year 4, 6, 8 and 10), it is vital that the OS tasks not be discarded, or superseded by current

attempts to develop alternative assessment instruments for children during the pre-school,

beginning and early years of schooling.

9

If such attempts were to be successful, the prognosis

for the on-going use of the OS (and the survival of Reading Recovery in Australia) would be

problematic. Given the established utility of the Observation Survey and its wide usage

throughout Australia (and internationally), this would be tantamount to an unjustified and

expensive throwing-out-the-baby-with-the-bath-water situation.

7

For validity and reliability definitions and estimates for the OS tasks, see Clay (2002, pp. 159-162).

8

See Clay (2002, Appendix 1, p. 148).

9

One such attempt is the recent development of the Australian Early Development Index (AEDI).

However, consistent with the warnings of its developers, the AEDI is strictly a population/

epidemiological screening instrument for the assessment of community-based cohorts of children at

the time of school entry (see CCCH & TICHR, 2005). As such, and despite widespread discussions

concerning its potential for developmental screening at the individual child level at school entry, the

AEDI can/cannot do or present/absent items related to its five domains do not have pedagogical

utility for teachers.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Combined RSTAQ & LDA Associations Conference: 21-22 September 2007

ASESS and ASSIST 7 K.J . Rowe

_____________________________________________________________________________________

The second approach to assessment, and characteristic of the LLANS example illustrated in

Figure 2 above, is what Griffin (1989) and Masters (1994; Masters & Forster, 1995a,b; Masters

et al., 1990) refer to as developmental achievement maps

10

. Masters (1994, p. 9) notes:

This approach, like the first, seeks to provide a more explicit identification of outcomes and a

framework against which the progress of an individual, a school, or an entire education system

can be mapped and followed. But this approach is built not around the notion of an outcomes

checklist, but around the concept of growth...Student progress is conceptualised and measured on

a growth continuum, not as the achievement of another outcome on a checklist.

As shown in Figure 2, locations along this growth continuum are illustrated by descriptive

indicators of stages or levels of increasing competence typically displayed by students at those

locations. However, unlike the can/cannot do, checklist model which describes students

performances deterministically, the levels of performance along the growth continuum are

described and reported probabilistically. That is, rather than attempting to make unequivocal

can/cannot do judgements, this growth model approach to the assessment of learning ans

achievement progress aims to provide estimates of a students current and developing levels of

performance and,

...provides an accompanying description of the kinds of understandings and skills typically

displayed by students at that level. To estimate a students current level of achievement, a wide

variety of assessment instruments can be used (Masters, 1994, p. 11).

The Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER) has developed several growth

model assessment instruments, the most notable of which include: the Developmental

Assessment Resource for Teachers (DART English) by Forster, Mendelovits and Masters

(1994). More recently, in collaboration with the New Zealand Council for Educational

Research (NZCER), ACER has developed the widely acclaimed Progressive Achievement Tests

in: (a) Reading: Comprehension and Vocabulary (PAT-R; ACER, 2005a), and (b) Mathematics

(PAT-Maths; ACER, 2005b). [For recent applications of the PAT-R and PAT-Maths

instruments in the context of monitoring the progress of students with learning difficulties, see:

Rowe, Stephanou & Hoad, 2007; and Rowe, Stephanou & Urbach, 2006].

A key feature of the PAT instruments, for example, is that because all test forms are

calibrated on a common developmental logit scale from school entry to Year 9/10, they are

particularly useful for teachers in: (a) monitoring students learning and achievement progress,

(b) diagnosing specific student learning strengths and weaknesses, and (c) providing teachers

with pointers for pedagogical intervention, whether for remediation and/or extension purposes.

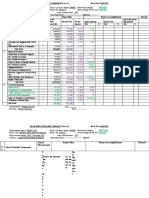

Figures 3 and 4 following illustrates student achievement profiles on the PAT-Reading

Comprehension and PAT-Maths scales, showing normative achievement growth distributions,

percentiles and stanines from school entry to Year 9 (or year 10). Note that the PAT manuals

(ACER, 2005a,b) provide the relevant qualitative descriptors of typical growth.

The utility of progress maps

The LLANS and PAT examples provided in Figures 2, 3 and 4 respectively, illustrate three

important advantages of monitoring learners achievement progress over time. First, the focus

is on understanding learning as it is experienced by the learners. Through such approaches an

attempt is made to understand the nature of growth within an area of learning across the years of

school, and provides vital information for teachers in assisting students learning and

achievement progress. The use of progress maps of learning to monitor and study progress

stands in contrast to more traditional curriculum-based approaches that impose a list of learning

objectives (or outcomes) that students are expected to learn, followed by assessments to

determine the extent to which these objectives have been achieved.

10

There are many local and international examples that could be cited here, but for recent examples, see:

Rowe (2007a); Rowe and Stephanou (2003, 2006); Schwartz (2005).

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Combined RSTAQ & LDA Associations Conference: 21-22 September 2007

ASESS and ASSIST 8 K.J . Rowe

_____________________________________________________________________________________

65.2 8.9 45.8 50.7 56.9 57.7 62.0

Mean

score

(patc)

Prep Year 4 Year 5 Year 6 Year 7 Year 8 Year 9 Year 3 Year 2 Year 1

33.5 22.5 39.5

Prep

Year 4

Year 5

Year 6

Year 7

Year 8

Year 9

Year 3

Year 2

Year 1

95

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

2

1

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

5

95

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

2

1

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

5

95

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

2

1

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

5

95

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

2

1

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

5

95

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

2

1

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

5

95

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

2

1

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

5 10

95

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

2

1

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

5

95

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

10

95

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

2

1

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

5

10

95

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

2

1

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

5

85

75

65

55

45

35

25

15

5

-5

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

-10

Scale score

(patc)

Figure 3. Student achievement profiles on the PAT-Reading Comprehension scale

showing normative achievement growth distributions, percentiles and

stanines from school entry to Year 9 (or year 10)

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Combined RSTAQ & LDA Associations Conference: 21-22 September 2007

ASESS and ASSIST 9 K.J . Rowe

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Figure 4. Student achievement profiles on the PAT-Maths scale showing normative

achievement growth distributions, percentiles and

stanines from school entry to Year 9 (or year 10)

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Combined RSTAQ & LDA Associations Conference: 21-22 September 2007

ASESS and ASSIST 10 K.J . Rowe

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Second, empirically-based maps of learning provide a basis not only for charting individual

and group progress, but also for studying influences on childrens learning trajectories similar

to those reported by Hill et al. (1998, 2002) from qualitative perspectives, and those reported by

Meiers, Khoo et al. (2006) from both quantitative and qualitative perspectives. The potential of

such maps lies in the opportunity they provide to identify and understand the nature of factors

associated with successful learning and rapid progress, as well as those that work to impede

student growth. Third, such maps provide a valuable framework for: (a) actively engaging

students in the monitoring of their own learning progress; (b) reporting to parents; and (c)

communicating with other teachers in the same school or with those in different schools,

regardless of their location. Typical of the comments made by parents upon receipt of their

childs achievement progress as illustrated in Figure 2 are:

This report of my childs progress at school is great! For the first time, I have both descriptions

and the evidence of what my child has achieved, what is currently being achieved, and what has

yet to be learnt and achieved. With the teachers guidance, I now know how best to help my

child at home. Before, I had no real idea of what was expected or how to help.

Similarly, teachers continue to make positive comments about the utility of these progress

maps. Typical of such comments include:

Using these maps, I can monitor the learning progress of each child in the class, as well as the

whole class against the norms for their age and grade levels. I can also identify what I need to

do to help those children who are not progressing as well as they could and should.

Clearly, these advantages point to important implications for how educational progress is

measured, monitored and reported over time. In contrast, when evidence about a students

achievement is reduced to a yes/no decision, or to a can/cannot do judgement concerning a

year-level performance standard, or to the progression points between the standards, including

the provision of mere judgmental gradings of the A-E variety, for example, valuable

information about that students learning and achievement progress is lost.

11

Rather, the

improvement of students school learning and its reporting depends on an understanding of the

variation in students levels of development and achievement; a willingness to monitor, map

and report individual growth in an area of learning across their years at school; and a

commitment to tailoring teaching and learning strategies/activities to students current levels of

achievement regardless of their age/grade levels, and whether or not they experience learning

difficulties (see Westwood, 2006).

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, developmental achievement maps of the kind

advocated and illustrated here, together with their reporting products, constitute major aids in:

(a) the integration of assessment into the teaching and learning cycle (see Westwood, 2000,

2001, 2005), (b) assisting children and adolescents to take ownership of their learning and

achievement progress, and (c) communicating with parents and other interested stakeholders.

By every criteria of educational effectiveness, this is basic commonsense. Regretfully, such

commonsense is not so common.

The imperative of building capacity in teacher professionalism

Three major principles underlie the imperative of building capacity in teacher professionalism.

First, young Australians are the most valuable resource for our nations social and economic

prosperity. Second, the key to such prosperity at both the individual and national level is the

provision of quality schooling (see Ingvarson & Rowe, 2007). Third, because teachers are the

11

In contrast to progress maps, letter grades (A, B, C, D, E) are an inadequate basis for monitoring and

reporting growth across the years of school. That is, a student who achieves the same grade (e.g., a

grade of D) year after year can appear to be making no progress at all; nor are such grades able to

describe and communicate what a student has actually achieved or is capable of achieving.

Moreover, due to contextual variations in teachers expectations and subsequent judgments of student

performance, an A grading in one context could well be equivalent to a D grading in another.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Combined RSTAQ & LDA Associations Conference: 21-22 September 2007

ASESS and ASSIST 11 K.J . Rowe

_____________________________________________________________________________________

most valuable resource available to schools, it is vital that teachers be equipped with evidence-

based teaching and assessment practices that are demonstrably effective in monitoring and

meeting the developmental and learning needs of all students for whom they have responsibility

regardless of students ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds, and whether or not they

experience learning difficulties (e.g., Hoad, Munro et al., 2007; Rowe KS, Pollard & Rowe,

2003, 2004, 2005, 2006).

Nowhere are these three principles more important than for teaching and learning in literacy

and numeracy, since being both literate and numerate are foundational, not only for school-

based learning, but also for students psychosocial wellbeing, further education and training,

occupational success, as well as for productive and fulfilling participation in social and

economic activity (DeWatt, Berkman et al., 2004; Hinshaw, 1992; Rowe & Rowe, 1999, 2000;

Sanson, Prior, Smart, 1996).. Moreover, the rapidly changing nature of global communication

systems, including computer-based technologies, demand competence in increasingly complex

multiliteracies, of which high levels of literacy and numeracy skill are essential (see Rowe,

2005a,b, 2006b).

Equipping young people to engage productively in the knowledge economy and in society

more broadly is fundamental to both individual and national prosperity. This objective depends

primarily on two factors: (a) students ability to read, write and undertake mathematical

computation; and (b) the provision of quality teaching and by teachers who have acquired

during their pre-service teacher education and subsequent in-service professional learning,

evidence-based teaching and assessment practices that are effective in monitoring and meeting

the developmental and learning needs of all students. Our young people and their teachers

require no less. Indeed, there is a strong body of evidence indicating that many cases of

learning difficulty and related under-achievement can be attributed to inappropriate or

insufficient teaching, rather than to deficiencies intrinsic to students such as cognitive, affective

and behavioural difficulties, as well as their socioeconomic, socio-cultural backgrounds and

contexts (see: Farkota, 2005; Rowe, 2006b, 2007a-c; Westwood, 2000, 2001, 2005, 2006;

Wheldall, 2006; Wheldall & Beaman, 1999). Clearly, the ultimate success of ASSESS and

ASSIST rests on the imperative of building capacity in teacher professionalism in terms of

quality assessment methods and evidenced-based pedagogical practices.

References

ACER (2005a). Progressive Achievement Tests in Reading: Comprehension and vocabulary (3

rd

edition).

Camberwell, VIC: Australian Council for Educational Research [ISBN 0 86431 384 5].

ACER (2005b). Progressive Achievement Tests in Mathematics (3

rd

edition). Camberwell, VIC:

Australian Council for Educational Research [ISBN 0 86431 644 5].

Black, P., & William, D. (1998). Assessment and classroom learning. Assessment in Education:

Principles, Policies and Practice, 5(1), 7-74.

CCCH & TICHR (2005). Australian Early Development Index: Building better communities for children.

Authored and produced by Centre for Community Child Health and Telethon Institute for Child

Health Research. Canberra, ACT: Commonwealth of Australia.

Clay, M.M. (2002). An observation survey of early literacy achievement (2nd ed.). Portsmouth, NH:

Heinemann Education.

DeWatt, D., Berkman, N.D, Sheridan, S., Lohr, K.N., & Pignone, M.P. (2004). Literacy and health

outcomes: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 19(12), 1228-

1239.

Embretson, S.E., & Hershberger, S.L. (Eds.) (1999). The new rules of measurement: What every

psychologist and educator should know. Mahwah, NJ : Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Farkota, R.M. (2005). Basic math problems: The brutal reality! Learning Difficulties Australia Bulletin,

37(3), 10-11.

Forster, M., Mendelovits, J ., & Masters, G.N. (1994). Developmental Assessment Resource for Teachers

(DART English). Camberwell, VIC: Australian Council for Educational Research.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Combined RSTAQ & LDA Associations Conference: 21-22 September 2007

ASESS and ASSIST 12 K.J . Rowe

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Glaser, R. (1963). Instructional technology and the measurement of learning outcomes: Some questions.

American Psychologist, 18, 519-521.

Griffin, P.E. (1989). Monitoring childrens growth towards literacy. The John Smyth Memorial Lecture,

University of Melbourne, September 5, 1989.

Hill, S., Comber, B., Louden, W., Rivalland, J ., & Reid, J -A. (1998). 100 children go to school. Canberra,

ACT: Department of Employment, Education, Training and Youth Affairs.

Hill, S., Comber, B., Louden, W., Rivalland, J ., & Reid, J -A. (2002). 100 children turn 10. Canberra,

ACT: Department of Employment, Education, Training and Youth Affairs.

Hinshaw, S.P. (1992). Externalizing behavior problems and academic under-achievement in childhood

and adolescence: Causal relationships and underlying mechanisms. Psychological Bulletin, 111, 127-

155.

Hoad, K-A., Munro, J., Pearn, C., Rowe, K.S., & Rowe, K.J. (2007). Working Out What Works (WOWW)

Training and Resource Manual: A teacher professional development program designed to support

teachers to improve literacy and numeracy outcomes for students with learning difficulties in Years 4,

5 and 6 (2nd edition). Canberra, ACT: Australian Government Department of Education, Science and

Training; and Camberwell, VIC: Australian Council for Educational Research [ISBN 978-0-86431-

766-7].

Ingvarson, L.C., & Rowe, K.J . (2007). Conceptualising and evaluating teacher quality: Substantive and

methodological issues. Background paper to keynote address presented at the Economics of Teacher

Quality conference, Australian National University, 5 February 2007. Available for download at:

http://www.acer.edu.au/documents/LP_Ingvarson_Rowe_TeacherQualityFeb2007.pdf.

Louden, W., Rohl, M., Barrat-Pugh, C., Brown, C., Cairney, T., Elderfield, J ., House, H., Meiers, M.,

Rivaland, J ., & Rowe, K.J. (2005a). In teachers hands: Effective literacy teaching practices in the

early years of schooling. Canberra, ACT: Australian Government Department of Education, Science

and Training.

Louden, W., Rohl, M., Barrat-Pugh, C., Brown, C., Cairney, T., Elderfield, J ., House, H., Meiers, M.,

Rivaland, J ., & Rowe, K.J . (2005b). In teachers hands: Effective literacy teaching practices in the

early years of schooling. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 28(3), 173-252.

Masters, G.N. (1982). A Rasch model for partial credit scoring. Psychometrika, 47, 149-174.

Masters, G.N. (1999). Objective measurement. In G.N. Masters and J .P. Keeves (Eds.), Advances in

Measurement in Educational Research and Assessment (Chapter 2). New York: Pergamon (Elsevier

Science).

Masters, G.N. (2004a). Objective measurement. In S. Alagumalai, D. Curtis, & N. Hungi (Eds.), Applied

Rasch Measurement: A book of exemplars (Chapter 2). London: Springer-Kluwer Academic

Publishers.

Masters, G.N. (2004b). Continuity and growth: Key considerations in educational improvement and

accountability. Background paper to keynote address presented at the joint Australian College of

Educators and Australian Council for Educational Leaders national conference, Perth, Western

Australia, 6-9 October 2004.

Masters, G.N., & Forster, M. (1995a). ARK Guide to Developmental Assessment. Camberwell, Vic: The

Australian Council for Educational Research.

Masters, G.N., & Forster, M. (1995b). Using Profiles for assessing and reporting students educational

progress: An overview of current ACER research and development. Paper presented at the conference

- Assessing and Reporting Students Educational Progress: Current Research, Policy and Practice;

National and State Developments. Graduate School of Management, the University of Melbourne,

March 1, 1995.

Masters, G.N., Lokan, J., Doig, B., Khoo, S.T., Lindsay, J ., Robinson, L., & Zammit, S. (1990). Profiles

of Learning: The Basic Skills Testing Program in New South Wales - 1989. Hawthorn, Vic: The

Australian Council for Educational Research.

Masters, G.N., & Forster, M. (1996a). Developmental Assessment. Assessment Resource Kit (ARK).

Camberwell, VIC: Australian Council for Educational Research.

Masters, G.N., & Forster, M. (1996b). Progress Maps. Assessment Resource Kit (ARK). Camberwell,

VIC: Australian Council for Educational Research.

Masters, G.N., & Forster, M. (1997). Mapping literacy achievement: Results of the National School

English Literacy Survey. Canberra, ACT: Commonwealth Department of Education, Training and

Youth Affairs.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Combined RSTAQ & LDA Associations Conference: 21-22 September 2007

ASESS and ASSIST 13 K.J . Rowe

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Masters, G.N., & Keeves, J .P. (Eds.) (1999). Advances in measurement in educational research and

assessment. New York: Pergamon (Elsevier Science).

Masters, G.N., Meiers, M., & Rowe, K.J. (2003). Understanding and monitoring childrens growth.

Educare News, 136 (May 2003), 52-53.

Masters, G.N., & Wright, B.D. (1997). The partial credit model. In W.J. van der Linden and R.K.

Hambleton (Eds.), Handbook of item response theory. New York: Springer.

Meiers, M. (1999a, September). A national longitudinal literacy and numeracy study. Paper presented at

the 24

th

Annual Congress of the Applied Linguistics Association of Australia, Perth, Western

Australia.

Meiers, M. (1999b, J uly and November). The Longitudinal Literacy and Numeracy Study. Paper

presented to Targeting Excellence, the 1999 Early Years of Schooling P-4 Conferences, Melbourne,

Victoria.

Meiers, M. (2000). Assessing literacy development and achievement: The importance of classroom

assessments. Australian Language Matters, 8(3), Aug/Sept 2000.

Meiers, M., & Forster, M. (1999, October). The Longitudinal Literacy and Numeracy Study (LLANS).

Paper presented at the ACER Research Conference 1999, Improving Literacy Learning, Adelaide.

Meiers, M., Khoo, S.T, Rowe, K.J ., Stephanou, A., Anderson, P., & Nolan, K. (2006). Growth in literacy

and numeracy in the first three years of school. ACER Research Monograph No. 61. Camberwell,

VIC: Australian Council for Educational Research [ISBN 0 86431 589 9]. Available at:

http://www.acer.edu.au/documents/LP_monograph61.pdf.

Meiers, M., & Rowe, K.J. (2002, December). Modelling childrens growth in literacy and numeracy in

the early years of schooling. Paper presented at the 2002 Annual Conference of the Australian

Association for Research in Education, University of Queensland, December 1-5, 2002 [Paper Code:

MEI02176].

Nitko, A. (1995). Curriculum-based continuous assessment: a framework for concepts, procedures and

policy. Assessment in Education, 2, 321-337.

Noss, R., Goldstein, H., & Hoyles, C. (1989). Graded assessment and learning hierarchies in

mathematics. British Educational Research Journal, 15, 109-120.

Nuttall, D.L. (1986). Editorial. In D.L. Nuttall (Ed.), Assessing Educational Achievement (pp. 1-4).

London: The Falmer Press.

Nuttall, D., & Goldstein, H. (1986). Profiles and graded tests: The technical issues. In P.M. Broadfoot

(Ed.), Profiles and Records of Achievement: A review of issues and practice (pp. 183-202). London:

Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

OECD (2005). Formative assessment: Improving learning in secondary classrooms. Paris: Organisation

for Economic co-operation and development.

Popham, W.J . (1978). Criterion-Referenced Measurement. Englewood Cliffs, NJ : Prentice Hall.

Rowe, K.J . (2002). The measurement of latent and composite variables from multiple items or indicators:

Applications in performance indicator systems. Background paper to keynote address presented at the

RMIT Statistics Seminar Series, October 11, 2002. Camberwell, VIC: Australian Council for

Educational Research. Available at: http://www.acer.edu.au//learning_processes/.

Rowe, K.J . (2004, August). The importance of teaching: Ensuring better schooling by building teacher

capacities that maximize the quality of teaching and learning provision implications of findings from

the international and Australian evidence-based research. Background paper to invited address

presented at the Making Schools Better summit conference, Melbourne Business School, the

University of Melbourne, 26-27 August 2004. Available in PDF format from ACERs website at:

http://www.acer.edu.au//learning_processes/.

Rowe, K.J . (2005a). Evidence for the kinds of feedback data that support both student and teacher

learning. Research Conference 2005 Proceedings (pp. 131-146). Camberwell, VIC: Australian

Council for Educational Research [ISBN 0-86431-684-4]. Available in PDF format from ACERs

website at: http://www.acer.edu.au//learning_processes/.

Rowe, K.J . (Chair) (2005b). Teaching reading: Report and recommendations. Report of the Committee

for the National Inquiry into the Teaching of Literacy. Canberra, ACT: Australian Government

Department of Education, Science and Training [ISBN 0 642 77577 X]. Available for download in

PDF format at: http://www.dest.gov.au/nitl/report.htm.

Rowe, K.J. (Chair) (2005c). Teaching reading literature review: A review of the evidence-based research

literature on approaches to the teaching of literacy, particularly those that are effective in assisting

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Combined RSTAQ & LDA Associations Conference: 21-22 September 2007

ASESS and ASSIST 14 K.J . Rowe

_____________________________________________________________________________________

students with reading difficulties. A report of the Committee for the National Inquiry into the

Teaching of Literacy. Canberra, ACT: Australian Government Department of Education, Science and

Training [ISBN 0 642 77575 3]. Available at: http://www.dest.gov.au/nitl/report.htm.

Rowe, K.J . (2006a). Assessment during the early and middle years: Getting the basics right. Background

paper to keynote address presented at the NSW DET K-4 Early Years of Schooling conference.

Telstra Stadium, Sydney Olympic Park, Homebush, 12-13 July 2006. Available for download at:

http://www.acer.edu.au/documents/LP_Rowe-AssessmentintheearlyandmiddleyearsJ uly2006.pdf.

Rowe, K.J . (2006b). Effective teaching practices for students with and without learning difficulties: Issues

and implications surrounding key findings and recommendations from the National Inquiry into the

Teaching of Literacy (Leading article). Australian Journal of Learning Disabilities, 11(3), 99-115.

Rowe, K.J. (2007a). The imperative of evidence-based practices for the teaching and assessment of

numeracy. Invited submission to the National Numeracy Review. Camberwell, VIC: Australian

Council for Educational Research. Available at: http://www.acer.edu.au/learning_processes/.

Rowe, K.J . (2007b). The imperative of evidence-based instructional leadership: Building capacity within

professional learning communities via a focus on effective teaching practice. Centre for Strategic

Education Seminar Series, No. 164, April 2007 [ISBN: 1-920963-45-6]. Available at:

http://www.cse.edu.au/seminar_series_latest.php.

Rowe, K.J . (2007c). School and teacher effectiveness: Implications of findings from evidence-based

research on teaching and teacher quality. In A. Townsend (Ed.), International Handbook of School

Effectiveness and Improvement Building on the past to chart the future: A critical review of

research, policy and practice in school effectiveness and improvement (Vol 2, Chapter 41, pp. 767-

786). New York: Springer [ISBN 1-4020-4805-X].

Rowe, K.J ., & Hill, P.W. (1996). Assessing, recording and reporting students educational progress: The

case for Subject Profiles. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policies and Practice, 3, 309-352.

Rowe, K.J., & Rowe, K.S. (1999). Investigating the relationship between students attentive-inattentive

behaviors in the classroom and their literacy progress. International Journal of Educational Research,

31(1-2), 1-138 (Whole Issue).

Rowe, K.J., & Rowe, K.S. (2000). Literacy and behavior: Preventing the shift from what should be an

educational issue to what has become a major health issue. International Journal of Behavioral

Medicine, 7 (Supp. 1), 81-82.

Rowe, K.J., & Stephanou, A. (2003). Performance audit of literacy standards in Victorian Government

schools, 1996-2002. A consultancy report to the Victorian Auditor Generals Office. Camberwell,

VIC: Australian Council for Educational Research.

Rowe, K.J ., & Stephanou, A. (2006, November). Assessment during the early and middle years: The

importance of monitoring growth. Invited paper presented at the National Roundtable on

Assessment and Reporting, Duxton Hotel, Perth WA, 13-14 November 2006.

Rowe, K.J ., Stephanou, A., & Hoad, K-A. (2007). A Project to investigate effective Third Wave

intervention strategies for students with learning difficulties who are in mainstream schools in Years

4, 5 and 6. Final report to the Australian Government Department of Education, Science and Training.

Camberwell, VIC: Australian Council for Educational Research [ISBN 978-0-86431-758-2].

Rowe, K.J ., Stephanou, A., & Urbach, D. (2006). Effective Teaching and Learning Practices Initiative for

Students with Learning Difficulties. Report to the Australian Government Department of Education,

Science and Training, the Department of Education and Training Victoria, Catholic Education Office

of Victoria, and the Association of Independent Schools of Victoria. Camberwell, VIC: Australian

Council for Educational Research.

Rowe, K.S., Pollard, J ., & Rowe, K.J . (2003). Auditory processing: Literacy, behaviour and classroom

practice. Speech Pathology Australia: ACQuiring Knowledge in Speech, Language and Hearing, 5(3),

134-137.

Rowe, K.S., Rowe, K.J., & Pollard, J. (2004). Literacy, behaviour and auditory processing: Building

fences at the top of the cliff in preference to ambulance services at the bottom. Research

Conference 2004 Proceedings (pp. 34-52). Camberwell, VIC: Australian Council for Educational

Research [ISBN 0-86431-755-7]. Available at: http://www.acer.edu.au/learning_processes/.

Rowe, K.S., Pollard, J ., & Rowe, K.J. (2005). Literacy, behaviour and auditory processing: Does teacher

professional development make a difference? Background paper to Rue Wright Memorial Award

presentation at the 2005 Royal Australasian College of Physicians Scientific Meeting, Wellington,

New Zealand, 8-11 May 2005. Available at: http://www.acer.edu.au/learning_processes/.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Combined RSTAQ & LDA Associations Conference: 21-22 September 2007

ASESS and ASSIST 15 K.J . Rowe

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Rowe, K.S., Pollard, J ., & Rowe, K.J (2006). Auditory Processing Assessment Kit: Understanding how

children listen and learn. Melbourne, VIC: Educational Resource Centre, The Royal Childrens

Hospital [ISBN 0-9775266-0-7]. Further information and an order form for the Kit is available at:

www.auditoryprocessingkit.com.au.

Sanson, A.V, Prior, M., & Smart, D. (1996). Reading disabilities with and without behaviour problems at

7-8 years: Prediction from longitudinal data from infancy to 6 years. Journal of Child Psychology and

Psychiatry, 37, 529-541.

Schwartz, R.M. (2005). Literacy learning of at-risk first-grade students in the Reading Recovery early

intervention. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97(2), 257-267.

Stephanou, A., Meiers, M., & Forster, M. (2000, October). Constructing scales for reporting growth in

numeracy: the ACER Longitudinal Literacy and Numeracy Study. Paper presented at the ACER

Research Conference 2000, Brisbane, 15-17 October 2000.

Torrence, H., & Pryor, J . (1995). Investigating teacher assessment in infant classrooms: Methodological

problems and emerging issues. Assessment in Education, 2, 305-320.

Westwood, P.S. (1999). Constructivist approaches to mathematical learning: A note of caution. In D.

Barwood, D. Greaves , and P. J effrey. Teaching numeracy and literacy: Interventions and strategies

for at risk students. Coldstream, Victoria: Australian Resource Educators Association.

Westwood, P.S. (2000). Numeracy and learning difficulties: Approaches to teaching and assessment.

Camberwell, VIC: Australian Council for Educational Research.

Westwood, P.S. (2001). Reading and learning difficulties: Approaches to teaching and assessment.

Camberwell, VIC: Australian Council for Educational Research.

Westwood, P.S. (2004). Learning and learning difficulties: A handbook for teachers. Camberwell, VIC:

Australian Council for Educational Research.

Westwood, P.S. (2005). Spelling: Approaches to teaching and assessment (2

nd

edition). Camberwell,

VIC: Australian Council for Educational Research.

Westwood, P.S. (2006). Teaching and learning difficulties: Cross-curricular perspectives. Camberwell,

VIC: Australian Council for Educational Research.

Wilson, M. (2005). Constructing measures: An Item Response Modelling approach. Mahwah, NJ :

Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Wheldall, K. (2006). Positive uses of behaviourism. In D.M. McInerney and V. McInerney, Educational

psychology: Constructing learning (4th ed., pp. 176-179). Frenchs Forrest, NSW: Pearson Education

Australia.

Wheldall, K., & Beaman, R. (1999). An evaluation of MULTILIT: Making up for lost time in literacy.

Canberra, ACT: Commonwealth Department of Education, Training and Youth Affairs.

Wolf, A. (1991). Assessing core skills: Wisdom or wild goose chase? Cambridge Journal of Education

21(2), 189-201.

Wright, B.D., & Mok, M. (2000). Rasch models overview. Journal of Applied Measurement, 1(1), 83-

106.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Combined RSTAQ & LDA Associations Conference: 21-22 September 2007

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Subject - Object Questions 4Document1 pageSubject - Object Questions 4Ricardo LizanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Soluciones A Condicionales y WishDocument0 pageSoluciones A Condicionales y Wishgaby38Pas encore d'évaluation

- Oral Practice Unit 7 English Consonants: Voiceless Palatoalvolar AffricateDocument1 pageOral Practice Unit 7 English Consonants: Voiceless Palatoalvolar AffricateRicardo LizanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Conditionals 0,1,2,3Document1 pageConditionals 0,1,2,3Ricardo Lizana100% (1)

- Perfect Tenses PracticeDocument3 pagesPerfect Tenses PracticeJuan Pablo Moreno BuenoPas encore d'évaluation

- My Family Tree-U2Document1 pageMy Family Tree-U2Ricardo LizanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Adverbs of Manner PDFDocument1 pageAdverbs of Manner PDFRicardo LizanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Reservas de Hoteles: Complete The Following Dialogues. You Have To Choose The Appropiate PhrasesDocument2 pagesReservas de Hoteles: Complete The Following Dialogues. You Have To Choose The Appropiate PhrasesRicardo LizanaPas encore d'évaluation

- 1st Graders 2Document2 pages1st Graders 2Ricardo LizanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Pronombre PosesivoDocument1 pagePronombre PosesivoRicardo LizanaPas encore d'évaluation

- 4 Grade Geomtery Test 1ADocument3 pages4 Grade Geomtery Test 1ARicardo LizanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Parts of The Car Nº1Document1 pageParts of The Car Nº1Ricardo LizanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Name: Code: Unit: Oral Presentación EvaluaciónDocument2 pagesName: Code: Unit: Oral Presentación EvaluaciónRicardo LizanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Pin, Spill, Upper, Lip.: Lesson 6 English ConsonantsDocument2 pagesPin, Spill, Upper, Lip.: Lesson 6 English ConsonantsRicardo LizanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Futuro Be GoingDocument2 pagesFuturo Be GoingRicardo LizanaPas encore d'évaluation

- WouldDocument2 pagesWouldRicardo LizanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Ultural Eprivation: Attitudes and ValuesDocument17 pagesUltural Eprivation: Attitudes and ValuesRicardo LizanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Consonants: Long Vowels Short VowelsDocument2 pagesConsonants: Long Vowels Short VowelsRicardo LizanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Vocabulary Prepositions in - On - atDocument2 pagesVocabulary Prepositions in - On - atRicardo LizanaPas encore d'évaluation

- 1.-USA A /anDocument1 page1.-USA A /anRicardo LizanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- WT Chapter 5Document34 pagesWT Chapter 5Wariyo GalgaloPas encore d'évaluation

- CH 13 RNA and Protein SynthesisDocument12 pagesCH 13 RNA and Protein SynthesisHannah50% (2)

- Corn Fact Book 2010Document28 pagesCorn Fact Book 2010National Corn Growers AssociationPas encore d'évaluation

- ODocument11 pagesOMihaela CherejiPas encore d'évaluation

- German Specification BGR181 (English Version) - Acceptance Criteria For Floorings R Rating As Per DIN 51130Document26 pagesGerman Specification BGR181 (English Version) - Acceptance Criteria For Floorings R Rating As Per DIN 51130Ankur Singh ANULAB100% (2)

- Mbs KatalogDocument68 pagesMbs KatalogDobroslav SoskicPas encore d'évaluation

- This Unit Group Contains The Following Occupations Included On The 2012 Skilled Occupation List (SOL)Document4 pagesThis Unit Group Contains The Following Occupations Included On The 2012 Skilled Occupation List (SOL)Abdul Rahim QhurramPas encore d'évaluation

- Manual Gavita Pro 600e SE EU V15-51 HRDocument8 pagesManual Gavita Pro 600e SE EU V15-51 HRwhazzup6367Pas encore d'évaluation

- Quarterly Progress Report FormatDocument7 pagesQuarterly Progress Report FormatDegnesh AssefaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Benefits of RunningDocument1 pageThe Benefits of Runningefendi odidPas encore d'évaluation

- Phenotype and GenotypeDocument7 pagesPhenotype and GenotypeIrish Claire Molina TragicoPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 Nitanshi Singh Full WorkDocument9 pages1 Nitanshi Singh Full WorkNitanshi SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Cranial Electrotherapy Stimulator (C.E.S.) Earlobe Stimulator, Pocket-Transportable, 9VDocument1 pageCranial Electrotherapy Stimulator (C.E.S.) Earlobe Stimulator, Pocket-Transportable, 9VemiroPas encore d'évaluation

- 2023 VGP Checklist Rev 0 - 23 - 1 - 2023 - 9 - 36 - 20Document10 pages2023 VGP Checklist Rev 0 - 23 - 1 - 2023 - 9 - 36 - 20mgalphamrn100% (1)

- Group 7 Worksheet No. 1 2Document24 pagesGroup 7 Worksheet No. 1 2calliemozartPas encore d'évaluation

- Durock Cement Board System Guide en SA932Document12 pagesDurock Cement Board System Guide en SA932Ko PhyoPas encore d'évaluation

- 2022.08.09 Rickenbacker ComprehensiveDocument180 pages2022.08.09 Rickenbacker ComprehensiveTony WintonPas encore d'évaluation

- Installation Manual (DH84309201) - 07Document24 pagesInstallation Manual (DH84309201) - 07mquaiottiPas encore d'évaluation

- Preservation and Collection of Biological EvidenceDocument4 pagesPreservation and Collection of Biological EvidenceanastasiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Chan v. ChanDocument2 pagesChan v. ChanjdpajarilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Reading Assignment Nuclear ChemistryDocument2 pagesReading Assignment Nuclear Chemistryapi-249441006Pas encore d'évaluation

- Birla Institute of Management and Technology (Bimtech) : M.A.C CosmeticsDocument9 pagesBirla Institute of Management and Technology (Bimtech) : M.A.C CosmeticsShubhda SharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Arann Magazine, Issue 1-2-Online VersionDocument36 pagesArann Magazine, Issue 1-2-Online VersionmujismilePas encore d'évaluation

- E3sconf 2F20187307002Document4 pagesE3sconf 2F20187307002Nguyễn Thành VinhPas encore d'évaluation

- UK FreshTECH Jammer RecipeBook 0Document24 pagesUK FreshTECH Jammer RecipeBook 0Temet NoschePas encore d'évaluation

- Moderated Caucus Speech Samples For MUNDocument2 pagesModerated Caucus Speech Samples For MUNihabPas encore d'évaluation

- BS7-Touch Screen PanelDocument96 pagesBS7-Touch Screen PanelEduardo Diaz Pichardo100% (1)

- UIP ResumeDocument1 pageUIP ResumeannabellauwinezaPas encore d'évaluation

- Wada Defending Cannabis BanDocument18 pagesWada Defending Cannabis Banada UnknownPas encore d'évaluation

- Virtual or Face To Face Classes Ecuadorian University Students' Perceptions During The Pandemic by Julia Sevy-BiloonDocument1 pageVirtual or Face To Face Classes Ecuadorian University Students' Perceptions During The Pandemic by Julia Sevy-BiloonPlay Dos ChipeadaPas encore d'évaluation