Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

An Analysis of Blasting Accidents in Coal Mines

Transféré par

polsiemprealdoDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

An Analysis of Blasting Accidents in Coal Mines

Transféré par

polsiemprealdoDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

AN ANALYSIS

OF BLASTING ACCIDENTS

IN COAL MINES

HARRY C. VERAKIS

U.S. Department of Labor

Mine Safety and Health Administration

Approval and Certification Center

Triadelphia, West Virginia

Talk for the

19th Annual Kentucky Blasting Conference,

Lexington, Kentucky

December 2-4, 1992

AN ANALYSIS OF BLASTING ACCIDENTS IN UNDERGROUND COAL MINES

by Harry C. Verakis

INTRODUCTION

The use of explosives in underground coal mines presents a

potential risk for serious injury and death to miners. A major

hazard associated with the use of explosives in coal mines is the

accidental ignition of methane and/or coal dust. Widespread

disasters (loss of 5 or more lives) have been caused by the

explosion of methane and/or coal dust initiated by blasting with

explosives. Many of these disasters occurred in the early 1900's

when the use of black powder in coal mines was prevalent. Since

that time great strides have been taken, making blasting- safer in

underground coal mines: (1) by eliminating the use of black

powder, (2) by the development, testing, approval and use of

safer explosives, (3) by the enactment and enforcement of safety

requirements, (4) by improvements in blasting techniques, (5) by

training and increasing the awareness of hazards. The combined

efforts of industry, labor, government agencies and trade

associations, such as the Society of Explosive Engineers (SEE)

and the Institute of Makers of Explosives (IME) have also been

very important in promoting safe blasting practices and reducing

accidents.

BLASTING ACCIDENT DISASTERS

As evidenced by events over the past 20 years, coal mine

disasters involving blasting continue to occur in spite of the

great progress made in explosives technology and blasting safety.

For example, the Hyden explosion which resulted in the loss of 38

lives occurred in December 1970, exactly one year after Congress

2

passed the comprehensive Federal Mine Health and Safety Act of

1969. The official agency report on this disaster (ref. 1)

concluded that the explosion occurred when coal dust was thrown

into suspension and ignited by detonating cord or by permissible

explosives used in a nonpermissible manner or by use of

nonpermissible explosives during the blasting of roof rock for a

loading point (boom hole). In another instance, two disasters

involving the use of explosives occurred within 6 weeks of each

other. These accidents, one in December 1981 and the other in

January 1982, were known by some as Topmost and RFH (Adkins Coal

Company No. 11 Mine and RFH Coal Company No. 1 Mine). These two

accidents resulted in the death of 8 and 7 miners, respectively.

The official agency report on the Topmost accident (ref. 2)

concluded that a coal dust explosion occurred when a blown-out

shot ignited coal dust.

In the RFH accident, the official agency

report (ref.

3) concluded that a coal dust explosion occurred

when a blown-out or blown-through shot ignited coal dust.

HISTORICAL ACCIDENT COMPARISON

In comparison to blasting accidents which occurred during

the first decade of the 1900's,

the reduction in injuries and

fatalities has been dramatic. For example, there were 111

explosion disasters with a total of 3,316 fatalities in the 10

year period from 1901-10 (ref. 4). Many of these disasters

resulted from the use of black powder and dynamite for blasting.

During the 23 year period from 1970-92, there were three (3)

blasting accidents, each involving 5 or more fatalities. These

three (3) accidents which resulted in a combined total of 53

fatalities were discussed earlier in this paper and are shown in

Table 1.

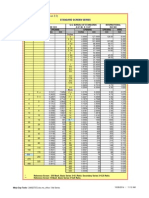

As the extraction of coal by the use of explosives in

underground coal mines continues to decline, so have fatalities

and injuries from blasting accidents. The consumption of

permissible explosives for blasting has fallen to 12.6 million

pounds in 1991 (ref. 7). Figure 1 shows the continual decrease

in the consumption of permissible explosives from 1980 through

1991. Nevertheless,, blasting accidents are still an important

safety concern. The concerted efforts of the mining and

explosives industry and labor and government agencies have

greatly improved the safety record of blasting in coal mines.

Great strides were made in reducing accidents in this Century as

the use of black powder for blasting was eliminated.

The use of

safer explosives and better blasting procedures and requirements

played an important role in improving the safety record. Serious

blasting accidents are a rarity today, compared to the early

1900's, when they were all too commonplace.

Although no disaster involving explosives has occurred since

1982, multiple fatalities have occurred in several accidents. A

recent accident resulting in three (3) fatalities from the use of

explosives occurred at the Granny Rose Coal Company's No. 3 Mine

in July 1990. This accident occurred when explosives located in

a scoop bucket attached to a battery-powered tractor were

unintentionally detonated simultaneously with routine production

blasting of a 3-way face (ref. 5).

Unfortunately, serious blasting accidents continue to

occur in coal mines. A previous analysis by the Bureau of Mines

showed that there were more blasting accident injuries in

underground coal mining than in any other type of mining (ref.

6).

BLASTING ACCIDENT ANALYSIS

In the 12 year period from 1980 through 1991, there were 45

fatalities from blasting accidents in underground coal mines.

Table 2 shows a list of these accidents which MSHA investigated

and the type or method of mining. The Youngs Branch No. 15 Mine

blasting accident is included in this list since it is an

underground coal mine. However, the accident occurred on the

surface of this mine from the burning of explosives. One

fatality and one injury resulted from this accident.

Several hundred underground coal mines use explosives to

extract coal, About 20 percent of these mines blast off-the-

solid. Forty (40) of the 45 fatalities from the blasting

accidents during the 12 year period (1980-91, Table 2) occurred

at mines that blasted coal off-the-solid. Six (6) of the 40

fatalities occurred in anthracite mines. Almost 90 percent of

these fatalities occurred in mines that blasted off-the-solid.

As discussed earlier, two of the accidents which occurred within

6 weeks of each other were major disasters.

Since the 1969 Coal

Mine Health and Safety Act, there have been three (3) major

disasters caused by blasting. These three (3) disasters, listed

in Table 1, resulted in 53 fatalities. An analysis of these

three (3) disasters show a feature common to them was the

resulting ignition and propagation of a coal dust explosion.

During the 12 year period from 1980-91, there were 16

accidents and 34 fatalities that occurred in mines that use

blasting-off-the-solid techniques. These accidents all occurred

in small mines employing less than 15 persons. A listing of the

accidents, extracted from Table 2, is shown in Table 3. Multiple

violations of federal mine safety standards occurred in each of

these accidents. It is important to note that none of these

accidents occurred as the result of using permissible explosives

in a permissible manner. Inadequate safety practices were

determined to be factors in all of these accidents. Each of the

accidents was analyzed and important factors in these accidents

were as follows:

* Use of nonpermissible explosive materials

* Failure to follow mine projection

* Poor ventilation

* Failure to withdraw persons from worksites adjacent to

blast site

* Drilling and loading of holes simultaneously

* Detonators were not shunted

* Explosives were not stored in a safe location

* Angled boreholes were drilled beyond the rib line

* Failure to conduct methane checks

6

* Loading boreholes with more, than 3 pounds of explosive

* Failure to stem explosive-loaded boreholes

* Shot blew out or blew through to adjacent work area

* Insufficient rock dusting

* Excessive accumulations of coal dust

* Lack of an accurate and up-to-date map of the mine

* Insufficient burden parallel to a loaded borehole

* Improper handling of misfires

As determined by a U.S. Bureau of Mines study published in

the proceedings of the Society of Explosive Engineers (ref. 6), a

lack of blast area security is a factor in about 50 percent of

the blasting accidents.

BLASTING REQUIREMENTS

In order to improve the safety requirements, extensive

revision has been made by MSHA on blasting regulations and

approval standards for explosives used in underground coal mines.

These final rules were published in the Federal Register on

November 18, 1988, with an effective date of January 17, 1989.

The revised regulations provide increased safety protection for

miners by addressing specific blasting hazards and including more

performance oriented requirements. The regulations also address

advances in technology such as the sheathed explosive for

unconfined blasting. These standards contain requirements for

qualification of persons handling and using explosives.

The

standards address the use of permissible explosives and blasting

equipment, transportation and storage of explosives and

7

detonators, preparation before blasting, blasting circuits,

methane checks, firing procedures, examination after blasting and

misfires. The standards also specify the amount of explosive

that is permitted to be used in a borehole and address stemming

and stemming material for boreholes.

A section in the revised standards addresses multiple-shot

blasting which includes blasting of cut coal and blasting-off-

the-solid. This standard addresses the sequence of firing and

the delay intervals between shots with a limitation placed on

total elapsed blasting time not to exceed 1000 milliseconds for

bituminous and lignite mines. Further details may be found in

Title 30, Code of Federal Regulations (ref. 8,9) and in several

MSHA papers (ref. 10,ll).

SUMMARY

The decline in the number of accidents and injuries in this

Century from blasting in coal mines is largely due to the

introduction and use of permissible explosives, improvements in

blasting practices and adherence to safety requirements.

In this analysis, many of the fatalities from blasting

accidents over the last 12 years occurred in mines that use

blasting off-the-solid methods. An analysis of these accidents

indicated that knowledge of and training on safe blasting

practices are important to avoid explosives accidents. Moreover,

constant vigilance and adherence to these safety practices and

the applicable regulations when using explosives must be

8

maintained and followed to minimize blasting accidents and

injuries.

9

REFERENCES

1. Westfield, J., Malesky, J. S., and Crawford

Department of the Interior,

J. W. U. S.

Bureau of Mines Official Report of

Major Mine Explosion Disaster, Nos. 15 and 16 Mines, Finley Coal

Company, Hyden, Leslie County, Kentucky, December 30, 1970.

2. Lusmork, C. E. and Elam, R. A.,

U. S. Department of Labor,

Mine Safety and Health Administration, Report of Investigation

Underground Mine Coal Dust Explosion, No. 11 Hine, Adkins Coal

Company, Kite, Knott Counts, Kentucky, December 7, 1981.

3. Elam, R. A. and Teaster, E. C., Jr., U. S. Department of

Labor, Mine Safety and Health Administration, Report of

Investigation Underground Coal Mine Dust Explosion, No. 1 Mine,

RFH Coal Company, Craynor, Floyd County, Kentucky, January 20.

1982.

4. Humphrey, H. B., Historical Summary of Coal-Mine Explosions

in the United States, 1810-1958, U. S. Bureau of Mines Bulletin

586, 1960.

5. McGraw, C, E., et.al., U. S. Department of Labor, Mine

Safety and Health Administration, Report of Investigation

Underground Coal Mine Explosives Accident, No. 3 Mine, Granny

Rose Coal Company, Barbourville, Knox County, Kentucky, July 31,

1990.

6. D'Andrea, D. V., Kopp, J. W., and Fletcher, L. R., Mine

Blasting Accident Update, Society of Explosive Engineers,

Proceedings of the 17th Conference on Explosives and Blasting

Techniques, Vol. 1, Las Vegas, NV., February 3-7, 1991.

7. Apparent Consumption of Industrial Explosives and Blasting;

Agents in the United States,

Explosives,

Mineral Industry Surveys,

Annual from 1980 through 1991, U. S. Bureau of Mines,

Washington, DC.

8. Code of Federal Regulations, Title 30, Chapter 1, Mine

Safety and Health Administration, U. S. Department of Labor, Part

15, Requirements for Approval of Explosives and Sheathed

Explosive Units,

DC.,

U. S. Government Printing Office, Washington,

July 1, 1992,

9. Code of Federal Regulations, Title 30, Mine Safety and

Health Administration,

75,

U. S. Department of Labor, Subpart N,

Explosives and Blasting, U. S. Government Printing Office

Part

Washington, DC., July 1, 1992.

10

10. Verakis, H. C.9 MSHA's New Regulations for Explosives Used

in Coal Mines, Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference

of Safety in Mines Research Institutes, sponsored by the U. S.

Bureau of Mines, Washington, DC., September 11-15, 1989,

11. Verakis, H. C., and Uraco, J. L., The Approval and Use of

Explosives in Coal Mines, Proceedings of the 18th Annual

Conference on Explosives and Blasting Technique, Orlando, FL,

International Society of Explosives Engineers, January 19-23,

1992,

Date

l/20/82

12/7/81

12/30/70

Table 1 -- Blasting accidents involving 5 or more

fatalities in coal mines, 1910-92

Name

RFH, No. 1 Mine

Adkins, No.11 Mine

Hyden, No. 15 & 16

mines

Fatalities

1

8

38

Injuries

0

0

1

(slightly)

Table 2 -- Blasting accidents in coal mines,

Date Mine Name

Type or

Method* Deaths

Inju-

ries

11/19/91 Wolf Branch Collieries, C 1

No. 1 Mine

11/15/91 Youngs Branch No. 15 Mine

9/13/90 " D " Shaft, VP-5 Mine

9/10/90 " D " Shaft, VP-5 Mine

8/26/90 "D" Shaft, VP-3 Mine

7/31/90 Granny Rose Coal Co.,

No. 3 Mine

3/29/89 Tippy Coal Co., No. 1 Mine

3/8/88 Gordon Coal Co., #6

l/9/88 Rent. Mt.Res., No. 1 Mine

9/22/86 T&R Coal Co. Mine No. 3A

12/12/85 Buck Mt. Slope

12/11/85 MSW Coal Co., No. 2 Slope Mine

8/15/85 R&R Coal Co., No. 3 Mine

7/9/85 G&G Coal Co., Mine No. 1

6/3/85 B&M Tunnel

3/16/84 Superior Coal Co., Mine No. 1

5/10/83 Consol, Arkwright No. 1 Mine

4/12/83 Golden Chip Coal Co.,

NO. 10 Mine

6/l/82 Coyt Earls, Jr. Coal Co.,

No. 1 Mine

l/20/82 RFH Coal Co., No. 1 Mine

l/5/82 W.R.W. Corp., No. 1 Mine

12/7/81 Adkins Coal Co., No. 11 Mine

11/30/81 Ensol Coal Co., No. 2 Mine

10/21/81 Meally Coal Co., No. 2 Mine

10/12/81 Big Hill Coal Co., No. 4 Mine

l/3/81 D.O. & W Coal Co., No. 5 Mine

12/18/80 Ziegler Coal Co., No. 5 Mine

10/27/80 Frank Crawford, Jr. Coal Co.,

No. 1 Mine

10/8/80 Adkins Coal Co., No. 11 Mine

g/3/80 Rebeca Coal Co., No. 2 Mine

9/1/80 C.S. and S. Coal Co.,

Mammoth Slope

UGS

x

x

x

S

S

S

S(O)

C

A

A

S

S

A

C

P

c

0

1

1

0

2

3

3

1

0

1

0

0

S 1

S 7

S 2

S 8

S 0

S 1

s 1

C 1

C 1

S 3

S

S-R

A

1

1

1

*

A , Anthracite

C, Cut coal

S, Solid coal

S-R, Solid with

rock partings

O, outby location

P, Coal pillar stumps

CGS Surface of underground mine

X, Shaft sinking

1980-91

0

1

0

0

0

2

1

2

0

1

0

1

1

0

4

0

3

1

2

0

0

0

3

0

1

1

0

0

2

2

1

Date

7/31/90

3/29/89

3/8/88

l/9/88

8/15/85

7/9/85

6/l/82

l/20/82

l/5/82

12/7/81

11/30/81

10/21/81

10/12/81

10/27/80

10/8/80

9/3/80

Table 3 -- Accidents that occurred during

blasting-off-the-solid

Mine Name State Fatalities

Granny Rose

Coal Co.,

No. 3 Mine

Tippy Coal Co.,

No. 1 Mine

Gordon Coal Co.,

#6

Kent. Mt.Res.,

No. 1 Mine

R&R Coal Co.,

No. 3 Mine

G&G Coal Co.,

Mine No. 1

Coyt Earls, Jr.

Coal Co.,

No. 1 Mine

RFH Coal Co.,

NO. 1 Mine

W.R.W. Corp.,

No. 1 Mine

Adkins Coal Co.,

No. 11 Mine

Ensol Coal Co.,

No. 2 Mine

Meally Coal Co.,

No. 2 Mine

Big Hill Coal Co.,

No. 4 Mine

Frank Crawford, Jr.

Coal Co., No. 1 Mine

Adkins Coal Co.,

NO. 11 Mine

Rebeca Coal Co.,

No. 2 Mine

KY

KY

KY

KY

KY

TN

KY

KY

KY

KY

KY

KY

KY

KY

KY

VA

3

Injuries

2

FIGURE 1

CONSUMPTION OF PERMISSIBLE EXPLOSIVES

YEARS

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Utilities MixerDocument1 pageUtilities MixerpolsiemprealdoPas encore d'évaluation

- Utilities - STD Sieve SeriesDocument1 pageUtilities - STD Sieve SeriespolsiemprealdoPas encore d'évaluation

- RodParam OpenDocument46 pagesRodParam OpenpolsiemprealdoPas encore d'évaluation

- Utilities - Storage Capacity - 4-Wall BinDocument2 pagesUtilities - Storage Capacity - 4-Wall BinpolsiemprealdoPas encore d'évaluation

- Utilities SlurriesDocument2 pagesUtilities SlurriespolsiemprealdoPas encore d'évaluation

- SAGParam OpenEJEMPLO2Document120 pagesSAGParam OpenEJEMPLO2polsiemprealdoPas encore d'évaluation

- HPGRSim Openpractica1Document83 pagesHPGRSim Openpractica1Aldo PabloPas encore d'évaluation

- SAGParam OpenEJEMPLO2Document120 pagesSAGParam OpenEJEMPLO2polsiemprealdoPas encore d'évaluation

- About ... Moly-Cop ToolsDocument4 pagesAbout ... Moly-Cop Toolspolsiemprealdo100% (1)

- Moly-Cop Tools (Version 3.0) : Particle Size Distribution (Double Weibull Distribution Fit)Document2 pagesMoly-Cop Tools (Version 3.0) : Particle Size Distribution (Double Weibull Distribution Fit)polsiemprealdoPas encore d'évaluation

- CVP Model ManualDocument28 pagesCVP Model ManualpolsiemprealdoPas encore d'évaluation

- SAGSim OpenDocument124 pagesSAGSim OpenpolsiemprealdoPas encore d'évaluation

- Media Charge Wear Rod MillsDocument3 pagesMedia Charge Wear Rod MillspolsiemprealdoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Disaster NursingDocument6 pagesDisaster NursingMark Zedrix MediarioPas encore d'évaluation

- 22 Minis Owners Manual 3 22Document8 pages22 Minis Owners Manual 3 22KenlerPas encore d'évaluation

- Atomic BombingsDocument12 pagesAtomic BombingsMethira DulsithPas encore d'évaluation

- TM 9 1300 251 20 Artillery Ammunition ManualDocument222 pagesTM 9 1300 251 20 Artillery Ammunition ManualM21 Halftrackus100% (1)

- People V UlitDocument2 pagesPeople V UlitFox MacalinoPas encore d'évaluation

- Cfi Weighted CriteriaDocument3 pagesCfi Weighted CriteriaFreddy José CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- Welcome To The Nra Basic Range Safety Officer Course: National Rifle AssociationDocument109 pagesWelcome To The Nra Basic Range Safety Officer Course: National Rifle AssociationCarmeloPas encore d'évaluation

- MDD1C - FGL+G02+G03+G04 Buildings T C For QCD Upload Master Tracking S... 09-09-18Document9 pagesMDD1C - FGL+G02+G03+G04 Buildings T C For QCD Upload Master Tracking S... 09-09-18asathish.eeePas encore d'évaluation

- RPD Daily Incident Report 8/27/23Document4 pagesRPD Daily Incident Report 8/27/23inforumdocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Emergency Action AND Fire Prevention Plan: Sample Written Safety Program ForDocument6 pagesEmergency Action AND Fire Prevention Plan: Sample Written Safety Program ForVinod ChaudhariPas encore d'évaluation

- Basic Concept OF Hazard: Disaster Risk Reduction and ReadinessDocument14 pagesBasic Concept OF Hazard: Disaster Risk Reduction and ReadinessYay SandovalPas encore d'évaluation

- Types of Disasters - 0Document8 pagesTypes of Disasters - 0William Jaya PrakashPas encore d'évaluation

- T2000 v2 Twilight-2000 2nd Edition Version 2.2 PDFDocument6 pagesT2000 v2 Twilight-2000 2nd Edition Version 2.2 PDFFranzis Landwehr44% (9)

- WFP FpasDocument2 pagesWFP FpasChanBoonKeatPas encore d'évaluation

- Hotworkpermit PDFDocument2 pagesHotworkpermit PDFjacobpm2010Pas encore d'évaluation

- Fire HazardDocument15 pagesFire HazardAudrey JanapinPas encore d'évaluation

- 10 Fire Safety Checklist Permanent StructuresDocument7 pages10 Fire Safety Checklist Permanent StructuresayselPas encore d'évaluation

- Safety Program Emergency Procedures For High-Rise Buildings PDFDocument57 pagesSafety Program Emergency Procedures For High-Rise Buildings PDFSiddique Ahmed0% (1)

- 09 Rendering CBR DevicesDocument3 pages09 Rendering CBR DevicesDavid GoldbergPas encore d'évaluation

- Mil STD 444Document161 pagesMil STD 444Vlad VladPas encore d'évaluation

- RGD 5Document7 pagesRGD 5Scimitar McmlxvPas encore d'évaluation

- US Experience With Sprinklers: Marty Ahrens October 2021Document18 pagesUS Experience With Sprinklers: Marty Ahrens October 2021Omar MohammedPas encore d'évaluation

- BSI Fire Standards Brochure UK enDocument4 pagesBSI Fire Standards Brochure UK enuttam bosePas encore d'évaluation

- Infinity Army ListDocument2 pagesInfinity Army ListFrederik RasaliPas encore d'évaluation

- Breechloading FlintlockDocument12 pagesBreechloading FlintlockNikos GatoulakisPas encore d'évaluation

- Bioterroris M: DR - Sakshi Mishra Mph-SemiDocument26 pagesBioterroris M: DR - Sakshi Mishra Mph-SemiSakshi MishraPas encore d'évaluation

- BATTLEGROUP WWII v1.2Document84 pagesBATTLEGROUP WWII v1.2VaggelisPas encore d'évaluation

- Sig P320 Owner ManualDocument80 pagesSig P320 Owner ManualDerek LoGiudicePas encore d'évaluation

- SFFD Payroll 2009Document142 pagesSFFD Payroll 2009SFAppealPas encore d'évaluation

- Advocacy PlanDocument3 pagesAdvocacy PlanSharon GuzmanPas encore d'évaluation