Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Novartis Pharms. Corp. Et Al. v. Par Pharm., Inc., C.A. No. 11-1077-RGA

Transféré par

YCSTBlog0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

274 vues16 pagesD. Del.

Titre original

Novartis Pharms. Corp. et al. v. Par Pharm., Inc., C.A. No. 11-1077-RGA

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentD. Del.

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

274 vues16 pagesNovartis Pharms. Corp. Et Al. v. Par Pharm., Inc., C.A. No. 11-1077-RGA

Transféré par

YCSTBlogD. Del.

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 16

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF DELA WARE

NOV ARTIS PHARMACEUTICALS

CORPORATION, NOVARTIS AG,

NOVARTIS PHARMA AG, NOVARTIS

INTERNATIONAL PHARMACEUTICAL

LTD., and LTS LOHMANN THERAPIE-

SYSTEME AG,

Plaintiffs,

v.

PAR PHARMACEUTICAL, INC.,

Defendant.

Civil Action No. 11-1077-RGA

(Consolidated)

TRIAL OPINION

Michael P. Kelly, Esq., and Daniel M. Silver, Esq., Mccarter & English, LLP, Wilmington, DE;

Nicholas N. Kallas, Esq., Charlotte Jacobsen, Esq., Fitzpatrick, Cella, Harper & Scinto, New

York, NY.

Attorneys for Plaintiffs Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, et al.

Steven J. Fineman, Esq., and Katharine C. Lester, Esq., Richards, Layton & Finger, P.A.,

Wilmington, DE; Daniel G. Brown, Esq., Latham & Watkins LLP, New York, NY; Roger J.

Chin, Esq., Latham & Watkins LLP, San Francisco, CA; Jennifer Koh, Esq., Latham & Watkins

LLP, San Diego, CA; Michelle Ma, Esq., Latham & Watkins LLP, Menlo Park, CA.

Attorneys for Defendant Par Pharmaceutical, Inc.

August 'Q._, 2014

I

I

r

!

l

I

I

l

~

ANDRE CT JUDGE:

Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, Novartis AG, Novartis Pharma AG, Novartis

International Pharmaceutical Ltd., and LTS Lohmann Therapie-Systeme AG (collectively,

"Novartis" or "Plaintiff') brought this suit against Watson Laboratories, Inc., Watson Pharma,

Inc., Watson Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (collectively "Watson"), and Par Pharmaceutical, Inc ("Par"

or "Defendant")

1

alleging infringement of U.S. Patents Nos. 6,335,031 ("the '031 patent") and

6,316,023 ("the '023 patent") (collectively, "the patents in suit"). Both patents share the same

specification.

2

Novartis sells an Exelon transdermal patch for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease that

contains rivastigmine. (D.I. 374-1at4).

3

Novartis listed the '031 and '023 patents in the Food

and Drug Administration's "Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence

Evaluations," frequently referred to as the "Orange Book," as covering the Exelon patches.

Par's Abbreviated New Drug Application 202,339 ("ANDA") seeks approval to engage in the

commercial manufacture, importation, use, or sale of a rivastigmine transdermal system, in 4.6

mg/24 hr, 9.5 mg/24 hr, and 13.3 mg/24hr dosage strengths. The basic design of the drug is

depicted

4

below:

1

Both the Par and Watson defendants were scheduled for trial beginning on August 26, 2013. Par and Novartis

informed the Court on the morning of the first day of trial that a settlement had been reached. Relying on this

representation, the Court entered an order staying the action with respect to Par for forty-five days and dismissed Par

from the trial. (D.1. 293). The settlement later fell through, and a trial for Par and Novartis took place on May 1,

2014.

2

Unless otherwise noted, all citations to the specification refer to the '031 patent.

3

Unless otherwise noted, all citations to the docket are to case l:l l-cv-01077-RGA.

4

The picture is modified from trial exhibit PDX 102. It is presented here only as a general demonstrative and no

part of it should be considered a factual finding by the Court.

1

Release Liner Backing Layer

Novartis asserts that Par's ANDA products infringe claim 7 of the '031 Patent because

acetaldehyde meets claim 7's antioxidant requirement. (D.I. 403 at 5). Par counters that if

acetaldehyde is found to be an antioxidant, then claim 7 fails to meet the requirements of 35

U.S.C. 112, as the claim is both indefinite and the claim does not meet the written description

requirement.

The Court held a two day bench trial on May 1 and 2, 2014. (D.I. 398, 399 (collectively

referred to as Tr.)). As explained below, Novartis failed to prove that Par's ANDA products

infringe by a preponderance of the evidence, and thus the Court does not reach the issue of

invalidity.

5

I. INFRINGEMENT

The one asserted claim in the '031 patent, claim 7, depends from non-asserted

independent claim 1. Claim 1 of the '031 patent recites:

A pharmaceutical composition comprising:

(a) a therapeutically effective amount of (S)-N-ethyl-3-{(1-

dimethylamino)ethyl}-N-methyl-phenyl-carbamate in free base

or acid addition salt form (Compound A);

5

Par's counterclaim for invalidity was based upon a finding of infringement. As there is no infringement, the Court

need not reach the issue of invalidity. Par specifically stated that it would only be pursuing its invalidity arguments

ifthere were a finding of infringement.

2

1

I

(b) about 0.01 to about 0.5 percent by weight of an antioxidant,

based on the weight of the composition, and

( c) a diluent or carrier.

'031 patent, claim 1. In the claim language "Compound A" refers to rivastigmine, the "S"

enantiomer of the racemic compound RA1. Claim 7 narrows claim 1 by limiting it to a specific

delivery method. Claim 7 reads:

Id. , claim 7.

A transdermal device comprising a pharmaceutical composition as defined

in claim 1, wherein the pharmaceutical composition is supported by a

substrate.

Claim 7 is a "presence" claim, and thus requires proof that Compound A and an

antioxidant are present. The Court defined "antioxidant" as an "agent that reduces oxidative

degradation." (D.I. 250, pp. 1-2). There is no additional requirement that the antioxidant

function with respect to Compound A because that is specifically required in the function claims.

(Id., p. 2 ("The patents repeatedly disclose the combination of Compound A and the antioxidant

without specifically requiring that the antioxidant affect Compound A. It would be improper to

preclude those embodiments by limiting 'antioxidant' to require that interaction." (internal

citations omitted))).

The parties agree that whether Par's ANDA product infringes raises only two issues: (1)

whether an antioxidant is present and (2) whether that antioxidant will be present in Par's ANDA

products in the amount claimed by the '031 patent. (D.1. 403 at 5; D.I. 410 at 6). Novartis

argues both that acetaldehyde is an antioxidant and that it is present in the patch in sufficient

quantities to infringe the '031 Patent. Par maintains that acetaldehyde is not an antioxidant, and

3

I

J

I

I

f

l

I

r

f:

even if it were, it would not be present in the final ANDA product at sufficient levels to violate

the '031 Patent.

A. LegalStandard

"Under [35 U.S.C.] 271(e)(2)(A), a court must determine whether, ifthe drug were

approved based upon the ANDA, the manufacture, use, or sale of that drug would infringe the

patent in the conventional sense." Glaxo, Inc. v. Novopharm, Ltd., 110 F.3d 1562, 1569 (Fed.

Cir. 1997). The application of a patent claim to an accused product is a fact-specific inquiry.

See Kustom Signals, Inc. v. Applied Concepts, Inc., 264 F.3d 1326, 1332 (Fed. Cir. 2001).

Literal infringement is present only when each and every element set forth in the patent claims is

found in the accused product.

6

See Southwall Techs., Inc. v. Cardinal JG Co., 54 F.3d 1570,

1575-76 (Fed. Cir. 1995). The patent owner has the burden of proving infringement by a

preponderance of the evidence. Envirotech Corp. v. Al George, Inc., 730 F.2d 753, 758 (Fed.

Cir. 1984) (citing Hughes Aircraft Co. v. United States, 717 F.2d 1351, 1361 (Fed. Cir. 1983)).

Infringement can be shown by "any method of analysis that is probative of the fact of

infringement," and, in some cases, "circumstantial evidence may be sufficient." Martek

Biosciences Corp. v. Nutrinova, Inc., 579 F.3d 1363, 1372 (Fed. Cir. 2009).

B. Findings of Fact

1. Oxidation is the process in which one compound, the reducing agent, transfers

an electron to another compound, the oxidizing agent.

2. Oxidative degradation is the process by which oxidation causes a chemical

compound to degrade.

3. Acetaldehyde is a reducing agent.

6

There are no assertions of infringement by the doctrine of equivalents.

4

4. Reducing agents can work as antioxidants.

5. Acetaldehyde does not form a stable radical and therefore it can also

contribute to oxidative degradation.

6. A stress test is when a researcher creates an oxidizing environment that is

capable of accelerating oxidative degradation.

7. Dr. Davies's stress test has not been performed prior to the present litigation.

8. Typical levels of confidence accepted in the scientific community are 0.9,

0.95 and 0.99.

9. Acetaldehyde has not been previously considered an antioxidant.

10. Plaintiff has not proven acetaldehyde is an antioxidant.

C. Conclusions of Law

1. The asserted claim does not require an antioxidant that acts upon Compound A

Three limitations of the presence claims are: Compound A, a certain weight percent of

antioxidant, and a diluent or carrier. See, e.g., '031 patent, claim 1. Unlike the function claims,

nowhere in the presence claims is any function of the antioxidant mentioned. Compare id.

(requiring Compound A and "about 0.01 to about 0.5 percent by weight of an antioxidant"), with

id., claim 11 (requiring Compound A "and an amount of antioxidant effective to stabilize

Compound A from degradation" (emphasis added)). The Court cautioned in its claim

construction opinion that it would be "improper to impute the antioxidant's stabilizing effect on

Compound A, explicitly claimed in some claims [i.e., the function claims], into claims that do

not contain that explicit limitation [i.e., the presence claims]." (D.I. 250, p. 2). Par nevertheless

maintains that "antioxidant," as used in the patents in suit, "requires the presence of an agent that

reduces oxidative degradation of some component in the claimed composition." (D.I. 318, pp.

5

l

I

I

I

f

l

f

I

12-13 {"The definition of 'antioxidant' adopted by the Court, 'an agent that reduces oxidative

degradation,' plainly recognizes that the term is a functional limitation that requires a reduction

of oxidative degradation in the claimed composition.")). This argument is rejected as being

inconsistent with the Court's claim construction.

2. It was not proven that acetaldehyde is an antioxidant

The Plaintiff argues that acetaldehyde is an antioxidant, while the Defendant maintains

that acetaldehyde is not an antioxidant.

a. The mere fact that acetaldehyde is a reducing agent does not make it

an antioxidant.

The Plaintiffs first argument is that acetaldehyde is a reducing agent, and as reducing

agents can act as antioxidants, acetaldehyde is an antioxidant. (D.I. 403 at 7). The parties do not

contest that acetaldehyde is a reducing agent. They do disagree whether the simple fact that

acetaldehyde is a reducing agent, by default, makes it an antioxidant. The Court agrees with the

parties that acetaldehyde is a reducing agent. See JTX06 l {VAN NOSTRAND'S CONCISE

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF SCIENCE ("[Acetaldehyde] also is used as a reducing agent. ... ")). The Court

finds, however, that the Plaintiff failed to put forth sufficient evidence to show that because

acetaldehyde is a reducing agent, it must be an antioxidant.

Oxidation is the process in which one compound, the reducing agent, transfers an

electron to another compound, the oxidizing agent. {Tr. 233).

7

When a compound accepts an

electron, it is reduced, and when a compound gives away an electron, it is oxidized. Id. This

process is generally referred to as the redox process. Id. The redox process leads to oxidative

degradation, "the process by which the oxidation level of [a] chemical compound results in [the

7

Par presents no explanation within its post-trial briefing as to how the oxidation cycle works. The Court relies upon

the Defendant's expert's testimony for how a redox reaction works. There was no meaningful disagreement

between the experts regarding how redox reactions work.

6

chemical's] degradation." Id. The process itself "begins with some organic compound[]," which

is oxidized to become a radical. Id at 233, 234. The radical then reacts with a molecule of

oxygen to form a peroxy radical. Id. at 234. When the "peroxy radical encounters another

organic molecule[,] such as the substance being degraded," "[t]he peroxy radical will abstract the

hydrogen and be reduced, thus forming ... a peroxide ... and regenerating the initial radical. ..

. " Id. This process is cyclical, and thus can cause a chain reaction and cause organic compounds

to transform into their oxidative degradation products. Id. This cyclical process can be broken

or slowed by the presence of an antioxidant, which the Court construed as an "agent that reduces

oxidative degradation." (D.I. 250 at 1). Antioxidants can be reducing agents that function by

forming a radical, after being oxidized, that is more stable than the degradation pathway, and

thus slows or stops the redox reaction. (Tr. at 236-37). As discussed above, reducing agents are

simply substances that will reduce some other compound. Id. at 238. Therefore, some reducing

agents form one class of antioxidants. (Tr. at 79, 238-39).

Both parties agree that acetaldehyde is a reducing agent. (D.I. 410 at 12; 417 at 6). The

question then is, has the Plaintiff put forth enough evidence to show that acetaldehyde

additionally is an antioxidant. While the Plaintiffs experts testified that some reducing agents

act as antioxidants, there was no testimony as to what portion of reducing agents are

antioxidants. Therefore, the most that can be garnered out of the Plaintiffs expert's testimony is

that, as acetaldehyde is a reducing agent, it may be an antioxidant. This is not sufficient to show,

by a preponderance of the evidence, that acetaldehyde is an antioxidant.

Par's expert, Dr. Ganem, convincingly testified that the likelihood that acetaldehyde is an

antioxidant is decreased because it does not form a stable radical. (Tr. 237). Instead, as Dr.

Ganem testified, acetaldehyde forms a highly reactive radical that itself can contribute to

7

t

I

f

!

I

I

f

I

I

oxidative degradation. Id. Furthermore, the principal review journal of the American Chemical

Society, Chemical Reviews, reports that when acetaldehyde undergoes oxidation it can form four

different chemical radicals, each of which can contribute to oxidative degradation. Id. at 240-42;

JTX 86 at 335. Dr. Ganem further testified that all of these reactive radicals form readily at

room temperature. (Tr. at 242-43). While the Plaintiff argues that these radicals would only

form at minus 30C, and thus are not relevant to this analysis, the Defendant's expert

persuasively explained that this temperature was used during the experiment so as to be able to

isolate the various compounds and that the various compounds would also form at room

temperature. Id. It is noteworthy that the Plaintiff's own experts are not cited by the Plaintiff as

discussing this issue. Thus the Court finds both that the Plaintiff has not demonstrated that

acetaldehyde is an antioxidant, merely because it is a reducing agent, and that the Defendant

demonstrated that acetaldehyde could promote oxidative degradation, thus making it an

"oxidant" rather than an "antioxidant."

b. Dr. Davies' Stress Test does not show that acetaldehyde is an

antioxidant.

The Plaintiff argues that Dr. Davies' stress test shows that acetaldehyde is an antioxidant,

while the Defendant argues that the test is not reliable and thus provides the Court with no

additional relevant evidence.

8

A stress test involves creating an oxidizing environment that is capable of accelerating

the degradation of a compound so that its degradation can be studied within a relatively short

period of time. (Tr. at 88). Thus by adding or subtracting variables, such as an additional

chemical or different lighting, stress tests can be used to determine a variable's effect on the

8

The parties dispute as to whether Dr. Davies' test meets the requirements of Daubert. The Court assumes without

deciding that the test does meet the Daubert standard.

8

I

l

I

I

f.

t

f

l

l

I

reaction. Id. at 89. Thus, if an experiment is properly conducted, by changing a single variable,

one can determine how the presence of a particular chemical alters the results of the chemical

reaction.

Dr. Davies, the Plaintiff's expert, conducted such a stress test. As described by the

Plaintiff, the stress test involved the following steps:

1. Preparing a single stock solution containing 0.36% rivastigmine and 1.3% of

the peroxide t-butyl hydroperoxide ("TBHP") in ethyl acetate solvent to

eliminate any variability that would result from multiple solutions;

2. Dividing the stock solution into two identical parts, added 0.0017%

acetaldehyde (an amount similar to that reported in some batches of Par's

ANDA product) to only one half of the stock solution, and used the other half

as a control;

3. Dividing each of the acetaldehyde-containing and control solutions into three

samples;

4. Stressing the samples at 60C; and

5. Measuring the extent of oxidative degradation after 6, 15, and 21 hours by

analyzing the samples using high performance liquid chromatography

("HPLC"), a common technique used in the pharmaceutical industry to identify

and quantify different compounds of a mixture.

(D.I. 403 at 8 (internal citations omitted)).

The credibility of Dr. Davies' test is diminished by the fact that, with the exception of its

use in the present case, Dr. Davies could not cite any literature or reference showing that the test

had ever been used to determine whether or not a compound was an antioxidant. (Tr. at 174).

Further because the experiment had not been conducted before, the potential rate of error for the

test is unknown. The test's unknown error rate is further compounded by the fact that Dr. Davies

did not repeat the test, or even run the test with a known antioxidant. Furthermore, Dr. Davies

failed to account for numerous substances in the experiment, which may have been generated by

side reactions with TBHP. Id. at 253. The Defendant's expert focuses on how this lack of

9

I

I

I

'

I

accounting would prevent the study from being published. Id. at 254. The Court is not so

concerned about whether the study is appropriate for publication. A study being appropriate for

publication would certainly provide a reason for the Court to provide greater weight to the study,

but the inability to publish the report, without more, is inconsequential, especially without

testimony as to the standards for publication, which was lacking here. Instead, the inability of

Dr. Davies to account for a large portion of the compounds present in the test, when combined

with the fact that this test has not been previously used, decreases the Court's confidence in the

persuasiveness of Dr. Davies' test. The Court notes that the Defendant also points out other

deficiencies of the test. For example, it does not properly model the conditions of the

transdermal patch. As the patent claim is a presence claim, however, these shortcomings are not

relevant to the present analysis. (D.I. 410 at 20).

The results of the test showed that the samples containing acetaldehyde resulted in more

rivastigmine and less rivastigmine oxidative degradation products than the control samples

without acetaldehyde. However, the two parties disagree as to how the results should be

interpreted. The Plaintiffs expert stated that he used a one-tail t-test, while the Defendant's

expert argued that a two-tail t-test was appropriate. Dr. Davies testified that a one-tail t-test was

appropriate as he expected that acetaldehyde would either have no effect or would be an

antioxidant. (Tr. at 129-30). The Defendant's expert, Dr. Michniak-Kohn, argued that a two-tail

t-test was appropriate as acetaldehyde could have promoted or reduced the rate of the

degradation cycle. Neither party put forth an expert on statistics to aid the Court in determining

which test is appropriate. Instead, the parties rely on argument, unsupported by persuasive

evidence, as to the appropriateness of the relevant tests. In the absence of evidence, the party

with the burden of proof fails. Thus, the lack of evidence as to which statistical test to use in

10

f

l

I

!

j

t

I

r

I

I

i

!:

l

I

!

determining whether the results of the stress test are significant prevents the Court from relying

on the test. However, ifthe Court were required to determine which test to rely upon, based on

the evidence presented, it seems more likely than not that the two-tail t-test is appropriate, as

evidence was presented at trial that acetaldehyde could act to both speed up and slow down the

redox cycle, which would support Dr. Michniak-Kohn's testimony. Further, choosing between

the testimony about statistics by two non-statisticians, the Court accepts Dr. Michniak-Kohn's

testimony that one-sided T-tests are rarely appropriate.

Using the two-tail t-test, the test results were inconclusive. There would be an 87 percent

level of confidence that the difference between the sample with acetaldehyde and without

acetaldehyde was significant. (Tr. at 401 ). The Plaintiff argues that this level of confidence is

above the necessary threshold to show that acetaldehyde is an antioxidant. The Court disagrees.

First, the Plaintiff cites Adams Respiratory Therapeutics, Inc. v. Perrigo Co. 616 F.3d 1283,

1287 (Fed. Cir. 2010). Adams turned on claim construction. The Federal Circuit found that it

was not necessary that the patentee prove that a drug was within a certain bioequivalent range to

a 90 percent confidence level because that requirement had not been incorporated into a relevant

claim construction. Id. Adams thus is of no assistance in deciding any issue before this Court.

Second, the confidence level is a determination of the likelihood that the differences between the

test results are statistically significant, that is, that the differences are real. It is not the case that a

confidence level of 87% means that 87% of the time acetaldehyde will be an antioxidant.

Instead a confidence level of 87% means that the difference between the results in the vials with

and without acetaldehyde have an 87% chance of being real. Dr. Michniak-Kohn testified that

such a result indicates that the one cannot draw a reliable conclusion from Dr. Davies' data as a

95% confidence level is scientifically preferable. (Tr. at 375). Her direct testimony was

11

I

I

t

f

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

supported by the Plaintiffs cross examination of her, in which an exhibit she relied on indicated

that typical confidence levels are 90, 95, and 99 percent with 95 percent being the most common.

Id. at 398. Eighty-seven percent falls below all of these confidence levels. While the Plaintiff

argues that 87% is still significant, the Plaintiff points to no evidence to support such a

conclusion. (D.I. 403 at 11 ). Argument is not evidence. Therefore, as there was no evidence

presented at trial that the parties cited in their briefing to show a confidence level of less than 90

percent is significant, the Court finds that the results of the stress test cannot be relied upon as

the results were not statistically significant.

The Court finds that the Plaintiffs stress test was not persuasive because: (1) Dr. Davies

failed to provide any evidence that the test had previously been used to determine whether a

chemical was an antioxidant, (2) the error rate for the test is unknown, and (3) Dr. Davies failed

to account for numerous unknown substances that formed as part of the test. However, even

accepting the test at face value, it did not yield statistically significant results because: ( 1) the

Plaintiff did not show that a one-tail t-test was the correct statistical tool to analyze the results,

and (2) under the two-tail t-test analysis, the results were not statistically significant. Thus

Plaintiff did not prove infringement.

c. Other Evidence

The Defendant presented other evidence to show that acetaldehyde is not an antioxidant.

First, Par presented evidence that acetaldehyde is not generally recognized as an

antioxidant. Dr. Buckton, an expert on drug substance testing, formulation development, and

stability testing of pharmaceutical products, testified that acetaldehyde is not listed as an

antioxidant in the '031 patent, the Handbook of Pharmaceutical Excipients, and other

pharmaceutical literature, because "acetaldehyde has never been used as and is not recognized as

12

l

I

I

I

an antioxidant." (Tr. at 436). Dr. Buckton's testimony was bolstered by that of Dr. Ganem who

testified that in his forty years as a chemistry professor with an expertise in oxidation and

reduction reactions he had never heard of acetaldehyde as an antioxidant. Id. at 238. Dr. Davies

additionally admitted that acetaldehyde is not listed as an antioxidant by the FDA. The Court

finds that while, the lack of acetaldehyde being listed as an antioxidant does not by itself prove

that acetaldehyde is not an antioxidant, it does move the needle in the Defendant's direction and

highlight the necessity of the Plaintiffs own testing demonstrating that acetaldehyde is an

antioxidant.

9

Second, Par performed stability testing, as described in the '031 patent, which Par argues

shows that acetaldehyde is not an antioxidant. (D .I. 410 at 14 ). The test involved comparing

batches of ANDA product that contained detectable levels of acetaldehyde with batches that did

not contain detectable levels of acetaldehyde. Dr. Buckton testified that the test showed

"absolutely no evidence at all that acetaldehyde can reduce oxidative degradation because the

product is clearly stable without any need for it." (Tr. 449-51). The Court finds this testimony

unhelpful. No evidence was presented that indicated what, if any, other compounds were either

present or not present within the batches. Furthermore, the Court was presented with no

testimony as to whether the results were statistically significant. In sum, the Court finds that

Par's testing was completely lacking in reliability and therefore the Court places no weight on it.

Third, Par argues that the Plaintiffs testing should be discredited because it was

conducted for the purpose of litigation. This argument is baseless. Parties in many cases (and

particularly in ANDA cases) regularly conduct testing for the purposes of litigation. When that

9

It occurs to me that this is a case in which claim construction has just confused the issues. The "presence" claims

require an antioxidant. No person of ordinary skill in the art would consider acetaldehyde to be an antioxidant.

Giving antioxidant its plain meaning, Par's ANDA product does not infringe because it does not contain what a

POSIT A would consider an antioxidant.

13

I

f

I

I

I

f;

f

!

i

!

'

i

testing is conducted, it has to be evaluated on its own merits, which is what I have tried to do

here. Dr. Davies is a reputable scientist. He has been subject to cross-examination, and Par

presented reputable experts to counter his work. I have evaluated the evidence in dispute.

d. Plaintiff has not shown by the preponderance of the evidence that

acetaldehyde is an antioxidant.

The Plaintiff has failed to prove by the preponderance of the evidence that acetaldehyde

is an antioxidant. First, the mere fact that acetaldehyde is a reducing agent does not show that

acetaldehyde is an antioxidant. Second, the experiment conducted by Dr. Davies provides no

usable evidence for the Court. The design of the experiment itself was uncertain. The Plaintiff

did not meet its burden of proving that the results of the experiment were significant. Therefore,

the Court finds that Dr. Davies' experiment does not show that acetaldehyde is an antioxidant.

Third, Par's testing provides no usable information for the Court. Fourth, Par's evidence that

acetaldehyde has never been considered an antioxidant is some evidence in Par's favor.

Considering all of this evidence, the Court finds that the Plaintiff has failed to provide sufficient

evidence to prove that it is more likely than not that acetaldehyde is an antioxidant. Therefore,

as the '031 patent requires the presence of an antioxidant and the Plaintiff identified no substance

other than acetaldehyde that could be an antioxidant, the '031 patent is not infringed.

II. INVALIDITY DEFENSES

Par indicated at both the trial and in its briefing that its asserted invalidity defenses are

only at play if acetaldehyde is found to be an antioxidant. (D.I. 401 at 6). As the Court did not

find acetaldehyde to be an antioxidant, the Court need not, and does not, make any findings

14

I

J

I

I

related to the Defendant's invalidity defenses. Judgment for Plaintiff will be entered on the

invalidity defenses.

10

III. CONCLUSION

Novartis did not prove that Par's ANDA products infringe claim 7 of the '031 patent. Par

should submit an agreed upon form of final judgment within two weeks.

10

Par's position was predicated on a non-infringement finding. Should the non-infringement finding be vacated or

reversed, I would not consider Par to have waived any right to argue its invalidity defenses on the record created at

trial.

15

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Gilead Sciences, Inc. v. Abbvie, Inc., C.A. No. 13-2034 (GMS) (D. Del. July 28, 2016) .Document3 pagesGilead Sciences, Inc. v. Abbvie, Inc., C.A. No. 13-2034 (GMS) (D. Del. July 28, 2016) .YCSTBlogPas encore d'évaluation

- AVM Technologies, LLC v. Intel Corp., C.A. No. 15-33-RGA/MPT (D. Del. May 3, 2016) .Document7 pagesAVM Technologies, LLC v. Intel Corp., C.A. No. 15-33-RGA/MPT (D. Del. May 3, 2016) .YCSTBlogPas encore d'évaluation

- Pfizer Inc. v. Mylan Inc., Civ. No. 15-960-SLR (D. Del. Aug. 12, 2016)Document14 pagesPfizer Inc. v. Mylan Inc., Civ. No. 15-960-SLR (D. Del. Aug. 12, 2016)YCSTBlogPas encore d'évaluation

- Idenix Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Gilead Sciences, Inc., C.A. No. 13-1987-LPS (D. Del. July 20, 2016)Document11 pagesIdenix Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Gilead Sciences, Inc., C.A. No. 13-1987-LPS (D. Del. July 20, 2016)YCSTBlogPas encore d'évaluation

- Delaware Display Group, LLC v. Lenovo Holding Co., Et Al., C.A. Nos. 13-2018-RGA, - 2109-RGA, - 2112-RGA (D. Del. May. 10, 2016) .Document3 pagesDelaware Display Group, LLC v. Lenovo Holding Co., Et Al., C.A. Nos. 13-2018-RGA, - 2109-RGA, - 2112-RGA (D. Del. May. 10, 2016) .YCSTBlogPas encore d'évaluation

- MiiCs & Partners America, Inc. v. Toshiba Corp., C.A. No. 14-803-RGA and v. Funai Electric Co., LTD., 14-804-RGA (D. Del. June 15, 2016) .Document6 pagesMiiCs & Partners America, Inc. v. Toshiba Corp., C.A. No. 14-803-RGA and v. Funai Electric Co., LTD., 14-804-RGA (D. Del. June 15, 2016) .YCSTBlogPas encore d'évaluation

- Inventor Holdings, LLC v. Bed Bath & Beyond Inc., C.A. No. 14-448-GMS (D. Del. May 31, 2016)Document9 pagesInventor Holdings, LLC v. Bed Bath & Beyond Inc., C.A. No. 14-448-GMS (D. Del. May 31, 2016)YCSTBlogPas encore d'évaluation

- GlaxoSmithKline LLC v. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc., C.A. No. 14-878-LPS-CJB (D. Del. July 20, 2016)Document39 pagesGlaxoSmithKline LLC v. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc., C.A. No. 14-878-LPS-CJB (D. Del. July 20, 2016)YCSTBlogPas encore d'évaluation

- Reckitt Benckiser Pharmaceuticals Inc., Et Al. v. Watson Laboratories, Inc., Et Al., C.A. No. 13-1674-RGA v. Par Pharmaceutical, Inc., Et Al., C.A. No. 14-422-RGA (D. Del. June 3, 2016)Document61 pagesReckitt Benckiser Pharmaceuticals Inc., Et Al. v. Watson Laboratories, Inc., Et Al., C.A. No. 13-1674-RGA v. Par Pharmaceutical, Inc., Et Al., C.A. No. 14-422-RGA (D. Del. June 3, 2016)YCSTBlogPas encore d'évaluation

- Viatech Techs., Inc. v. Microsoft Corp., C.A. No. 14-1226-RGA (D. Del. June 6, 2016) .Document2 pagesViatech Techs., Inc. v. Microsoft Corp., C.A. No. 14-1226-RGA (D. Del. June 6, 2016) .YCSTBlogPas encore d'évaluation

- IControl Networks, Inc. v. Zonoff Inc., C.A. No. 15-1109-GMS (D. Del. June 6, 2016)Document2 pagesIControl Networks, Inc. v. Zonoff Inc., C.A. No. 15-1109-GMS (D. Del. June 6, 2016)YCSTBlogPas encore d'évaluation

- Fidelity Nat'l Information Services, Inc. v. Plano Encryption Techs., LLC, Et Al., C.A. No. 15-777-LPS-CJB (D. Del. Apr. 25, 2016) .Document20 pagesFidelity Nat'l Information Services, Inc. v. Plano Encryption Techs., LLC, Et Al., C.A. No. 15-777-LPS-CJB (D. Del. Apr. 25, 2016) .YCSTBlogPas encore d'évaluation

- Toshiba Samsung Storage Technology Korea Corporation v. LG Electronics, Inc., Et Al., C.A. No. 15-691-LPS (D. Del. June 17, 2016)Document12 pagesToshiba Samsung Storage Technology Korea Corporation v. LG Electronics, Inc., Et Al., C.A. No. 15-691-LPS (D. Del. June 17, 2016)YCSTBlogPas encore d'évaluation

- Sanofi v. Glenmark Generics Inc. USA, C.A. No. 14-264-RGA (D. Del. June 17, 2016) .Document2 pagesSanofi v. Glenmark Generics Inc. USA, C.A. No. 14-264-RGA (D. Del. June 17, 2016) .YCSTBlogPas encore d'évaluation

- Interdigital Commc'ns, Inc. v. ZTE Corp., C.A. No. 13-009-RGA (D. Del. June 7, 2016) .Document7 pagesInterdigital Commc'ns, Inc. v. ZTE Corp., C.A. No. 13-009-RGA (D. Del. June 7, 2016) .YCSTBlogPas encore d'évaluation

- Blackbird Tech LLC d/b/a Blackbird Technologies v. Service Lighting and Electrical Supplies, Inc. d/b/a 1000bulbs.com et al., C.A. Nos. 15-53-RGA, 15-56-RGA, 15-57-RGA, 15-58-RGA, 15-59-RGA, 15-60-RGA, 15-61-RGA, 15-62-RGA, 15-63-RGA (D. Del. May 18, 2016).Document17 pagesBlackbird Tech LLC d/b/a Blackbird Technologies v. Service Lighting and Electrical Supplies, Inc. d/b/a 1000bulbs.com et al., C.A. Nos. 15-53-RGA, 15-56-RGA, 15-57-RGA, 15-58-RGA, 15-59-RGA, 15-60-RGA, 15-61-RGA, 15-62-RGA, 15-63-RGA (D. Del. May 18, 2016).YCSTBlogPas encore d'évaluation

- Walker Digital, LLC v. Google, Inc., C.A. No. 11-318-LPS (D. Del. Apr. 12, 2016)Document13 pagesWalker Digital, LLC v. Google, Inc., C.A. No. 11-318-LPS (D. Del. Apr. 12, 2016)YCSTBlogPas encore d'évaluation

- Visual Memory LLC v. Nvidia Corp., C.A. No. 15-789-RGA (D. Del. May 27, 2016) .Document17 pagesVisual Memory LLC v. Nvidia Corp., C.A. No. 15-789-RGA (D. Del. May 27, 2016) .YCSTBlogPas encore d'évaluation

- Segway Inc., Et Al. v. Inventist, Inc., Civ. No. 15-808-SLR (D. Del. Apr. 25, 2016)Document10 pagesSegway Inc., Et Al. v. Inventist, Inc., Civ. No. 15-808-SLR (D. Del. Apr. 25, 2016)YCSTBlogPas encore d'évaluation

- SRI Int'l, Inc. v. Cisco Sys., Inc., Civ. No. 13-1534-SLR (D. Del. Apr. 11, 2016) .Document45 pagesSRI Int'l, Inc. v. Cisco Sys., Inc., Civ. No. 13-1534-SLR (D. Del. Apr. 11, 2016) .YCSTBlogPas encore d'évaluation

- Scientific Telecommunications, LLC v. ADTRAN, Inc., C.A. No. 15-647-SLR (D. Del. Apr. 25, 2016) .Document4 pagesScientific Telecommunications, LLC v. ADTRAN, Inc., C.A. No. 15-647-SLR (D. Del. Apr. 25, 2016) .YCSTBlogPas encore d'évaluation

- Mobilemedia Ideas, LLC v. Apple Inc., C.A. No. 10-258-SLR (D. Del. Apr. 11, 2016) .Document19 pagesMobilemedia Ideas, LLC v. Apple Inc., C.A. No. 10-258-SLR (D. Del. Apr. 11, 2016) .YCSTBlogPas encore d'évaluation

- Hand Held Products 12-768Document14 pagesHand Held Products 12-768YCSTBlogPas encore d'évaluation

- Evonik Degussa GMBH v. Materia, Inc., C.A. No. 09-636-NHL/JS (D. Del. Apr. 6, 2016) .Document10 pagesEvonik Degussa GMBH v. Materia, Inc., C.A. No. 09-636-NHL/JS (D. Del. Apr. 6, 2016) .YCSTBlogPas encore d'évaluation

- Hand Held Products, Inc. v. Amazon - Com, Inc., Et Al., C.A. No. 12-768-RGA-MPT (D. Del. Mar. 31, 2016)Document5 pagesHand Held Products, Inc. v. Amazon - Com, Inc., Et Al., C.A. No. 12-768-RGA-MPT (D. Del. Mar. 31, 2016)YCSTBlogPas encore d'évaluation

- Carrier Corp 12-930Document2 pagesCarrier Corp 12-930YCSTBlogPas encore d'évaluation

- Bench and Bar Conference AgendaDocument5 pagesBench and Bar Conference AgendaYCSTBlogPas encore d'évaluation

- Sunpower Corporation v. PanelClaw, Inc., C.A. No. 12-1633-MPT (D. Del. Apr. 1, 2016)Document28 pagesSunpower Corporation v. PanelClaw, Inc., C.A. No. 12-1633-MPT (D. Del. Apr. 1, 2016)YCSTBlogPas encore d'évaluation

- Sunpower Corporation v. PanelClaw, Inc., C.A. No. 12-1633-MPT (D. Del. Apr. 1, 2016)Document28 pagesSunpower Corporation v. PanelClaw, Inc., C.A. No. 12-1633-MPT (D. Del. Apr. 1, 2016)YCSTBlogPas encore d'évaluation

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Biological Classification Class 11 Notes BiologyDocument6 pagesBiological Classification Class 11 Notes BiologyVyjayanthiPas encore d'évaluation

- Soal Pat Inggris Kelas 7 - 2021Document9 pagesSoal Pat Inggris Kelas 7 - 2021Bella Septiani FaryanPas encore d'évaluation

- Rankem SolventsDocument6 pagesRankem SolventsAmmar MohsinPas encore d'évaluation

- Composite Materials For Biomedical Applications: A ReviewDocument17 pagesComposite Materials For Biomedical Applications: A ReviewDuc Anh NguyenPas encore d'évaluation

- Psychology of Face Recognition Brief Introduction 2ndeditionDocument34 pagesPsychology of Face Recognition Brief Introduction 2ndeditionKevin Brewer100% (6)

- Methods, Method Verification and ValidationDocument14 pagesMethods, Method Verification and Validationjljimenez1969100% (16)

- Neural Network: Sudipta RoyDocument25 pagesNeural Network: Sudipta RoymanPas encore d'évaluation

- PDF 4Document19 pagesPDF 4Royyan AdiwijayaPas encore d'évaluation

- Cell Structure and Function ChapterDocument80 pagesCell Structure and Function ChapterDrAmit Verma0% (2)

- Chapter 15 - TeratogenesisDocument29 pagesChapter 15 - TeratogenesisMaula AhmadPas encore d'évaluation

- The Digestive System Challenges and OpportunitiesDocument9 pagesThe Digestive System Challenges and OpportunitiesPhelipe PessanhaPas encore d'évaluation

- Malting Process PDFDocument9 pagesMalting Process PDFRay TaipePas encore d'évaluation

- Pharmacogenetics Drug Drug Interactions1Document16 pagesPharmacogenetics Drug Drug Interactions1Marfu'ah Mar'ahPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Study On Dengue FeverDocument76 pagesCase Study On Dengue FeverMary Rose Silva Gargar0% (1)

- Competitive Intelligence AcceraDocument29 pagesCompetitive Intelligence AcceranarenebiowebPas encore d'évaluation

- Eosinophilic GastroenteritisDocument7 pagesEosinophilic GastroenteritisSotir LakoPas encore d'évaluation

- EstomagoDocument43 pagesEstomagoTanya FigueroaPas encore d'évaluation

- Karakterisasi Koleksi Plasma Nutfah Tomat Lokal Dan IntroduksiDocument7 pagesKarakterisasi Koleksi Plasma Nutfah Tomat Lokal Dan IntroduksiAlexanderPas encore d'évaluation

- Rmsa NotificationDocument17 pagesRmsa NotificationSrinivasu RongaliPas encore d'évaluation

- Antihuman GlobulinDocument18 pagesAntihuman GlobulinChariss Pacaldo ParungaoPas encore d'évaluation

- Salt IodateDocument2 pagesSalt IodateRKMPas encore d'évaluation

- Establishment of Cacao Nursery and ManagementDocument121 pagesEstablishment of Cacao Nursery and ManagementPlantacion de Sikwate100% (29)

- DMT of MNDDocument39 pagesDMT of MNDthelegend 2022Pas encore d'évaluation

- Water Indices For Water UsesDocument12 pagesWater Indices For Water UsesWayaya2009Pas encore d'évaluation

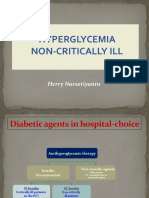

- Non-Critically Ill Hyperglycemia ManagementDocument39 pagesNon-Critically Ill Hyperglycemia ManagementHerry KongkoPas encore d'évaluation

- Udc Vol 1Document921 pagesUdc Vol 1Dani TrashPas encore d'évaluation

- Alexander Shekhtman, David S. Burz-Protein NMR Techniques (Methods in Molecular Biology, V831) - Springer (2011)Document533 pagesAlexander Shekhtman, David S. Burz-Protein NMR Techniques (Methods in Molecular Biology, V831) - Springer (2011)Alan Raphael MoraesPas encore d'évaluation

- Mcws Pamp (Final Pamp - Aug 8 2016)Document102 pagesMcws Pamp (Final Pamp - Aug 8 2016)Mount Calavite DENRPas encore d'évaluation

- Exampro GCSE Biology: B2.5 InheritanceDocument35 pagesExampro GCSE Biology: B2.5 InheritanceMeera ParaPas encore d'évaluation

- Pro67-A-13 Prep of McFarland StdsDocument6 pagesPro67-A-13 Prep of McFarland StdsWisnu Ary NugrohoPas encore d'évaluation