Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

The Teacher As Researcher

Transféré par

bibobib8100%(1)100% ont trouvé ce document utile (1 vote)

323 vues4 pagesSince 1970, Carlina Rinaldi has served as a Pedagogista and Director of the

Municipal Infant-Toddler Centers and Preschools of Reggio Emilia, Italy.

She is now a Pedagogical Consultant to Reggio Children, and a Professor at

the University of Modena and Reggio in the faculty of Science and Early

Education. The following is adapted from Carlina’s final presentation to the

United States delegation during the March 2003 study tour.

Titre original

THE TEACHER AS RESEARCHER

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentSince 1970, Carlina Rinaldi has served as a Pedagogista and Director of the

Municipal Infant-Toddler Centers and Preschools of Reggio Emilia, Italy.

She is now a Pedagogical Consultant to Reggio Children, and a Professor at

the University of Modena and Reggio in the faculty of Science and Early

Education. The following is adapted from Carlina’s final presentation to the

United States delegation during the March 2003 study tour.

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

100%(1)100% ont trouvé ce document utile (1 vote)

323 vues4 pagesThe Teacher As Researcher

Transféré par

bibobib8Since 1970, Carlina Rinaldi has served as a Pedagogista and Director of the

Municipal Infant-Toddler Centers and Preschools of Reggio Emilia, Italy.

She is now a Pedagogical Consultant to Reggio Children, and a Professor at

the University of Modena and Reggio in the faculty of Science and Early

Education. The following is adapted from Carlina’s final presentation to the

United States delegation during the March 2003 study tour.

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 4

Since 1970, Carlina Rinaldi has served as a Pedagogista and Director of the

Municipal Infant-Toddler Centers and Preschools of Reggio Emilia, Italy.

She is now a Pedagogical Consultant to Reggio Children, and a Professor at

the University of Modena and Reggio in the faculty of Science and Early

Education. The following is adapted from Carlinas final presentation to the

United States delegation during the March 2003 study tour.

We have now reached the moment of conclusions, of farewells. Concluding

means creating a meaning, a synthesis, a message to take with us after our experi-

ence together. Each of you will draw his or her own conclusions. Each of you will

decide what is useful and important, what to try to construct in your own con-

texts. I would like to underscore something that has been, and continues to be,

one of the most significant elements among those that we have tried to highlight

for you during these days . . . an element that has been fundamental to our expe-

rience: the concept of the teacher as a researcher.

Why is this concept so important? Why, among the many possibilities, do we

emphasize the qualification of researcher? Research is a word with many mean-

ings that can evoke laboratories, chemical formulas and science. It generally repre-

sents a clear and recognized methodology, and implies objectivity. The word

research has a serious tone, and tends to be reserved for the few people who

work in relationship with certain established and conventional procedures. It is a

concept that inhabits universities or specialized centers for research. It is a word

that does not circulate in the streets and squares. Research is not a word with

common usage and, above all, it is not a concept that we normally think about

putting into practice in our daily lives.

In schools, the word research usually means to gather a collection of information,

to compile what is already known about a certain topic. Experiences and emotions

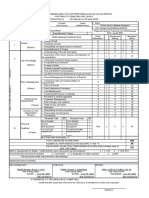

WHATS INSIDE

Thinking Together:

Teachers, Children and

Parents as Researchers

Book Review of

Bringing Learning to Life

When Pedagogy and

Design Intertwine:

The Story Behind the

NAREA Logo

Conference Calendar

New Resources

vol. 10, no. 2

Spring 2003

THE

TEACHER

AS

RESEARCHER

By Carlina Rinaldi

Innovations

Innovations

in early education: the international reggio exchange

P U B L I S H E D B Y T H E M E R R I L L - P A L M E R I N S T I T U T E , W A Y N E S T A T E U N I V E R S I T Y

continued on next page

THE QUARTERLY

PERIODICAL OF THE

NORTH AMERICAN

REGGIO EMILIA

ALLIANCE

I N N O V A T I O N S I N E A R L Y E D U C A T I O N

2

that characterize scientific research . . . such as

curiosity, the unknown, doubt, error, crisis, theory and

confusion . . . are not usually part of school work or

daily life. If they do enter into the context of life in the

school, they are viewed as weak moments . . .

moments of fragility, of uncertainty . . . that must be

overcome quickly.

In my opinion, this is why true innovations are so

difficult to accept and appreciate. They shake up

our frames of reference because they force us to look

at the world with new eyes. They open us up to what

is different and unexpected. We tend to accept the

status quo, that which we know and have already

tried out . . . even when it does not satisfy us, even

when it makes us feel stressed, confused or hopeless.

So, in this way, we try to defend our normality . . . the

norms and rules we already know . . . to the detriment

of the new. Only searching and researching can guar-

antee us that which is new, that which is moving for-

ward. Yet, this normality excludes research as an

everyday approach and, therefore, excludes doubt,

error, uncertainty, curiosity, marvel and amazement as

important values in our daily lives. Thus, we are

placing normality in opposition to research. I would

like, instead, to propose the concept of the normality

of research, which defines research as an attitude

and an approach in everyday living, in schools and in

life . . . as a way of thinking for ourselves and thinking

with others, a way of relating with others, with the

world around us and with life.

Where and how can we find the strength and the

courage for this radical change? Once again, we must

start with the children. The young child is the first

great researcher. Children are born searching for and,

therefore, researching the meaning of life, the mean-

ing of the self in relation to others and to the world.

Children are born searching for the meaning of their

existence . . . the meaning of the conventions, cus-

toms and habits we have, and of the rules and the

answers we provide.

Childrens questions (such as: Why are we born?

Why do we die?) are precious, as are their answers

because they are generative. Childrens theories (such

as: The sea is born from the mother wave. When

Children can give us the strength

of doubt and the courage of error.

They can transmit to us the joy of

searching and researching . . . the

value of research, as an openness

toward others and toward

everything new that is produced

by the encounter with others.

-Carlina Rinaldi

.

my interpretations of reality. This is why theories

should be continuously questioned and verified in an

exchange with others.

When we say that school is not a preparation for life

but is life, this means assuming the responsibility to

create a context in which words such as creativity,

change, innovation, error, doubt and uncertainty,

when used on a daily basis, can truly be developed

and become real. This means creating a context in

which the teaching-learning relationship is highly

evolved; that is, where the solution to certain prob-

lems leads to the emergence of new questions and

new expectations, new changes. This also means cre-

ating a context in which children, from a very young

age, discover that there are problems which are not

easily resolved, which perhaps cannot have an answer

and, for this reason, they are the most wonderful ones

because herein lies the spirit of research. Even

though the children are very young, we should not

convey to them the conviction that for every ques-

tion, there is a right answer. If we did so, perhaps we

would appear to be more important in their eyes and

they might feel more secure, but they would pay for

this security by losing the pleasure of research, the

pleasure of searching for answers and constructing the

answers with the help of others. Children are capable

of loving and appreciating us even when we appear

to be doubtful or we do not know how to answer,

because they appreciate the fact that we are side-by-

side with them in their search for answers: the child-

researcher and the teacher-researcher. Only in this

way will children return with full rights among the

builders of human culture and the culture of humani-

ty. Only in this way will they sense that their wonder

and their discoveries are truly appreciated because

they are useful. Only in this way can children and

childhood hope to reacquire their human dignity, and

no longer be considered objects of care or objects

of cruelty and abuse, both physical and moral. Life is

research.

The school of research is a school that is open to oth-

ers and to the new; indeed, it generates and proposes

the new within this encounter. Perhaps this is what

makes our encounter, the encounter with you, with a

country that we have been in dialogue with for about

twenty years, still current and vital. But above all, per-

haps this is what makes it possible for our teachers to

I N N O V A T I O N S I N E A R L Y E D U C A T I O N

3

you die, do you go into the belly of death and then

get born again?) highlight the strongest characteris-

tic of the identity of children and of humankind:

searching for and researching meaning, sharing and

constructing together the meaning of the world and

the events of life. All children are intelligent, different

from each other and unpredictable. If we know how

to listen to them, children can give back to us the

pleasure of amazement, of marvel, of doubt . . . the

pleasure of the why. Children can give us the

strength of doubt and the courage of error. They can

transmit to us the joy of searching and researching . .

. the value of research, as an openness toward others

and toward everything new that is produced by the

encounter with others.

These concepts give strength to the notion of educa-

tion and personal formation as an ongoing process of

research. They give meaning to the value of docu-

mentation and listening made visible, which are not

simply techniques that can be transported but ways of

guaranteeing that our thinking always involves reflec-

tion, exchange, different points of view, and differ-

ences in assessment or evaluation. They are not only

seen as didactic strategies but also as values that

inspire our view of the world. The documentation

materials we use attest not only to our path of knowl-

edge regarding children but also to our path of

knowledge about the child and humanity, and about

ourselves. They also attest to our idea of the teacher

as researcher, of school as a place of research and cul-

tural elaboration, a place of participation, in a process

of shared construction of values and meanings. The

school of research is a school of participation.

Moreover, this concept of the normality of research is

the best way to express what I believe is one of the

particular aspects of our experience, one of the most

topical cultural knots in these complex times: the

relationship between theory and practice. The

dichotomy of theory and practice, which has weighed

heavily on the world of school and on our culture,

could find a true dialectic and synthesis in this con-

cept of research. Within this concept, theory gener-

ates practice that, in turn, generates new theories and

new perspectives on the world. The theories come

from the practice, but also orient and guide it. The

theories are practical thoughts. My theories produce

I N N O V A T I O N S I N E A R L Y E D U C A T I O N

4

continue to work with pleasure and enthusiasm after

so many years. In fact, we feel that we can contribute

not only to the well-being of children and their

families, but also to changing the culture of our city.

Thanks to you and to our colleagues who come to

Reggio from all over the world, we can all contribute

together to changing the culture and the dialogue

in the world, raising the level of understanding

between us.

Today, like never before in the history of humanity

(as far as we know), we are in communication with

so many around the world. Our country is permeated

with faxes, cell phones, the Internet and other net-

works. The awareness of being connected, joined,

interdependent should bring people together but, in

reality, the lack of understanding persists. The problem

of understanding has become crucial for people every-

where. For this reason, understanding must be one of

the aims of education. Educating toward the under-

standing of math, science or any other discipline is

one thing; educating toward human understanding is

another. Information, though necessary, is not suffi-

cient for this depth of understanding. Explanations,

which are also indispensable, are still not enough for

true understanding.

Depth of understanding involves the ability to experi-

ence the curiosity, passions, joys and angers of others

with a process of empathy, perception and identifica-

tion, of human understanding. Always intersubjective,

human understanding requires openness, sympathy

and generosity. The children, the women and men of

today, more than ever, need understanding on the

part of other people who have open hearts and minds,

people who know how to recognize their own person-

al and cultural limitations. This is why I hope, above

all, that we have understood each other during this

week. It would be the ultimate outcome of our time

together.

When we say

that school is not a

preparation for life but is life,

this means assuming the

responsibility to create

a context in which words such

as creativity, change, innovation,

error, doubt and uncertainty,

when used on a daily basis,

can truly be developed

and become real.

-Carlina Rinaldi

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- (Early Childhood Education 86) Louise Boyd Cadwell, Carlina Rinaldi-Bringing Learning To Life - A Reggio Approach To Early Childhood Education - Teachers College Press (2002)Document229 pages(Early Childhood Education 86) Louise Boyd Cadwell, Carlina Rinaldi-Bringing Learning To Life - A Reggio Approach To Early Childhood Education - Teachers College Press (2002)Amykhine100% (4)

- Table Differences Between Reggio Montessori SteinerDocument5 pagesTable Differences Between Reggio Montessori SteinerAswiniie50% (2)

- The Importance of Intentional Socialization Among Children in Small Groups: A Conversation With Loris MalaguzziDocument5 pagesThe Importance of Intentional Socialization Among Children in Small Groups: A Conversation With Loris Malaguzzibibobib8Pas encore d'évaluation

- Consider The Walls PDFDocument5 pagesConsider The Walls PDFEdward Maldonado De La CruzPas encore d'évaluation

- Playing OutdoorsDocument174 pagesPlaying OutdoorsMelva YollaPas encore d'évaluation

- Abraham Maslow enDocument19 pagesAbraham Maslow enMenesteroso DesgraciadoPas encore d'évaluation

- Values and Principles of Reggio Emilia ApproachDocument2 pagesValues and Principles of Reggio Emilia Approachmariolipsy100% (1)

- GD402 Reading Friedman PDFDocument4 pagesGD402 Reading Friedman PDFIdol Yo0% (1)

- Reggio EmilioDocument16 pagesReggio Emilioapi-280357644Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Hundred Languages of ChildrenDocument3 pagesThe Hundred Languages of Childrenapi-547815045100% (1)

- Reggio Emilia For ParentsDocument3 pagesReggio Emilia For ParentsJelena JasicPas encore d'évaluation

- Article On Outdoor PlayDocument4 pagesArticle On Outdoor Playapi-559316869Pas encore d'évaluation

- Crisis ManagementDocument15 pagesCrisis Managementsimplexady100% (1)

- Script Arraignment and Pre-TrialDocument10 pagesScript Arraignment and Pre-TrialMarie80% (10)

- Five Stages of CEAC CycleDocument6 pagesFive Stages of CEAC CycleMica Alondra MendozaPas encore d'évaluation

- Philosophy Reggio EmiliaDocument5 pagesPhilosophy Reggio EmiliahuwainaPas encore d'évaluation

- Reggio Emilia ProgramDocument10 pagesReggio Emilia ProgramPrince BarnalPas encore d'évaluation

- New-Theory in To PracticeDocument9 pagesNew-Theory in To PracticetagiriPas encore d'évaluation

- The Relevance of Malaguzzi in ECEDocument20 pagesThe Relevance of Malaguzzi in ECESuzanne Axelsson80% (5)

- Developmental-milestonesDevelopmental Milestones and The EYLF and The NQSDocument20 pagesDevelopmental-milestonesDevelopmental Milestones and The EYLF and The NQSiamketul6340Pas encore d'évaluation

- Reggio Emilia ApproachDocument5 pagesReggio Emilia ApproachLow Jia HuanPas encore d'évaluation

- The Reggio Emilia Approach and CurriculuDocument6 pagesThe Reggio Emilia Approach and CurriculuRuchika Bhasin AbrolPas encore d'évaluation

- After Reggio Emilia: Let The Conversation Begin!Document9 pagesAfter Reggio Emilia: Let The Conversation Begin!David KennedyPas encore d'évaluation

- Reggio Emilia Approach1Document4 pagesReggio Emilia Approach1api-451874052Pas encore d'évaluation

- Malaysia Folk Literature in Early Childhood EducationDocument8 pagesMalaysia Folk Literature in Early Childhood EducationNur Faizah RamliPas encore d'évaluation

- YC1114 Quality Outdoor Play Spaces WrightDocument7 pagesYC1114 Quality Outdoor Play Spaces WrightwilliamsaminPas encore d'évaluation

- Early Years: Curriculum OverviewDocument8 pagesEarly Years: Curriculum Overviewshidik BurhaniPas encore d'évaluation

- The Philosophy Behind Froebel's Kindergarten ApproachDocument2 pagesThe Philosophy Behind Froebel's Kindergarten Approachmohanraj2purushothamPas encore d'évaluation

- Make Believe Play / Vygotskian Approach To Early Childhood EducationDocument14 pagesMake Believe Play / Vygotskian Approach To Early Childhood EducationAndreea ElenaPas encore d'évaluation

- Reggio Emilia ApproachDocument4 pagesReggio Emilia Approachmohanraj2purushothamPas encore d'évaluation

- Maria Montessori PDFDocument27 pagesMaria Montessori PDFvishnutej23Pas encore d'évaluation

- 11-Reggio Emilia ApproachDocument14 pages11-Reggio Emilia ApproachAmy Amilin Titamma100% (3)

- 1 The Reggio Emilia Concept or DifferentDocument14 pages1 The Reggio Emilia Concept or DifferentArian DinersPas encore d'évaluation

- 3period LessonokprintDocument3 pages3period LessonokprintFresia MonterrubioPas encore d'évaluation

- ASS Event 2-Documentation, Planning and Assessment 2Document13 pagesASS Event 2-Documentation, Planning and Assessment 2Liz LopezPas encore d'évaluation

- Chawla (2015) Benefits of Nature Contact For ChildrenDocument20 pagesChawla (2015) Benefits of Nature Contact For ChildrenAna FerreiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Loose Parts For Preschool - HandoutDocument3 pagesLoose Parts For Preschool - Handoutapi-330364939Pas encore d'évaluation

- Daily Schedule Examples - Creative Curriculum PDFDocument6 pagesDaily Schedule Examples - Creative Curriculum PDFstarfish26Pas encore d'évaluation

- Deca Parent Letter - EnglishDocument1 pageDeca Parent Letter - Englishapi-372771416Pas encore d'évaluation

- CambridgePapersInELT Play 2019 ONLINE PDFDocument24 pagesCambridgePapersInELT Play 2019 ONLINE PDFImran KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Emergent Curriculum Course FlyerDocument1 pageEmergent Curriculum Course Flyerjoanne_babalisPas encore d'évaluation

- The Role and Value of Creativity and Arts in Early EducationDocument7 pagesThe Role and Value of Creativity and Arts in Early EducationEmelda GreatPas encore d'évaluation

- Learning While Playing - Children's Forest School Experiences in The UKDocument20 pagesLearning While Playing - Children's Forest School Experiences in The UKAdli HakamaPas encore d'évaluation

- Access to Life Science: Investigation Starters for Preschool, Kindergarten and the Primary GradesD'EverandAccess to Life Science: Investigation Starters for Preschool, Kindergarten and the Primary GradesPas encore d'évaluation

- If You Give A Moose A MuffinDocument25 pagesIf You Give A Moose A Muffinapi-373177666Pas encore d'évaluation

- Spotlight On Play 21-1Document5 pagesSpotlight On Play 21-1api-238210311Pas encore d'évaluation

- Creating Indoor Environments For Young ChildrenDocument6 pagesCreating Indoor Environments For Young Childrenapi-264474189Pas encore d'évaluation

- CHD 215 Reggio Emilia 2Document34 pagesCHD 215 Reggio Emilia 2api-253286579Pas encore d'évaluation

- Loose Parts Play WebDocument72 pagesLoose Parts Play WebMargarita Lara RojasPas encore d'évaluation

- ART As Symbolic LanguageDocument15 pagesART As Symbolic LanguageNamrata SharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Plan - Building On Children's Interests PDFDocument5 pagesThe Plan - Building On Children's Interests PDFbeemitsuPas encore d'évaluation

- Creativity in Preschool AssessmentDocument15 pagesCreativity in Preschool AssessmentEstera Daniela GavrilutPas encore d'évaluation

- Reggio Children Publisher Catalogue LowDocument60 pagesReggio Children Publisher Catalogue LowRoxana SahanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Loose Parts Reggio EmiliaDocument10 pagesLoose Parts Reggio Emilialucycm158Pas encore d'évaluation

- 14 Oct PlanDocument4 pages14 Oct Planapi-223120833Pas encore d'évaluation

- Child Observations - N0ak95Document56 pagesChild Observations - N0ak95María Recio50% (2)

- Building on Emergent Curriculum: The Power of Play for School ReadinessD'EverandBuilding on Emergent Curriculum: The Power of Play for School ReadinessPas encore d'évaluation

- O'Brien, L. M. (2000) - Engaged Pedagogy - One Alternative To "Indoctrination" Into DAP. Childhood Education, 76 (5), 283-288.Document6 pagesO'Brien, L. M. (2000) - Engaged Pedagogy - One Alternative To "Indoctrination" Into DAP. Childhood Education, 76 (5), 283-288.Weiping WangPas encore d'évaluation

- Tools of The Mind: The Vygotskian-Based Early Childhood ProgramDocument16 pagesTools of The Mind: The Vygotskian-Based Early Childhood ProgramThe English TeacherPas encore d'évaluation

- Curriculum Approaches: Personal PhilosophyDocument3 pagesCurriculum Approaches: Personal Philosophyapi-360716367Pas encore d'évaluation

- What Shall We Do Next?: A Creative Play and Story Guide for Parents, Grandparents and Carers of Preschool ChildrenD'EverandWhat Shall We Do Next?: A Creative Play and Story Guide for Parents, Grandparents and Carers of Preschool ChildrenPas encore d'évaluation

- Pat Brunton, Linda Thornton - Understanding The Reggio Approach Early Years Education in Practice (2006)Document115 pagesPat Brunton, Linda Thornton - Understanding The Reggio Approach Early Years Education in Practice (2006)kirke anigard100% (6)

- Planning for the Early Years: The Local Community: How to plan learning opportunities that engage and interest childrenD'EverandPlanning for the Early Years: The Local Community: How to plan learning opportunities that engage and interest childrenPas encore d'évaluation

- Sample - Iper FtoDocument76 pagesSample - Iper FtoYeng CustodioPas encore d'évaluation

- UNFPA Career GuideDocument31 pagesUNFPA Career Guidealylanuza100% (1)

- Material Self. DiscussionDocument2 pagesMaterial Self. DiscussionRonald Tres ReyesPas encore d'évaluation

- Child Pornography-IJSRDocument4 pagesChild Pornography-IJSRparnitaPas encore d'évaluation

- 5S Housekeeping System: The Practice of Good Housekeeping by P.Vidhyadharan CBREDocument10 pages5S Housekeeping System: The Practice of Good Housekeeping by P.Vidhyadharan CBREBaskaran GopinathPas encore d'évaluation

- Work Immersion Narrative Report 190212121456Document25 pagesWork Immersion Narrative Report 190212121456Gener Rodriguez100% (6)

- African American Hair RevisedDocument4 pagesAfrican American Hair RevisedBonface OkelloPas encore d'évaluation

- Beg Borrow and Steal Ethics Case StudyDocument7 pagesBeg Borrow and Steal Ethics Case Studyapi-130253315Pas encore d'évaluation

- Chagos CaseDocument45 pagesChagos CaseReyar SenoPas encore d'évaluation

- Applications of Theory To Rehabilitation Counselling PracticDocument49 pagesApplications of Theory To Rehabilitation Counselling PracticShahinPas encore d'évaluation

- Background of The StudyDocument7 pagesBackground of The StudyMack harry Aquino100% (1)

- Payment of Gratuity The Payment of GratuityDocument4 pagesPayment of Gratuity The Payment of Gratuitysubhasishmajumdar100% (1)

- Munger 100Document7 pagesMunger 100Haryy MishraPas encore d'évaluation

- Good Reads ListDocument6 pagesGood Reads Listritz scPas encore d'évaluation

- The Holy Prophet's (Pbuh) Behavior Towards OthersDocument7 pagesThe Holy Prophet's (Pbuh) Behavior Towards OthersFatima AbaidPas encore d'évaluation

- Civil Suit For Permanent Prohibitory InjunctionDocument2 pagesCivil Suit For Permanent Prohibitory InjunctiongreenrosenaikPas encore d'évaluation

- Script LWR Report Noli MeDocument1 pageScript LWR Report Noli MeAngelEncarnacionCorralPas encore d'évaluation

- Media Ethic Chapter 3 Presentation Final PrintDocument17 pagesMedia Ethic Chapter 3 Presentation Final PrintfutakomoriPas encore d'évaluation

- ES 4498G Lecture 6 - 2010Document49 pagesES 4498G Lecture 6 - 2010Anonymous cSrSZu9Pas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 1Document2 pagesChapter 1Reno PhillipPas encore d'évaluation

- Operational Development PlanDocument3 pagesOperational Development PlanJob Aldin NabuabPas encore d'évaluation

- Asian Resurfacing of Road Agency Pvt. Ltd. and Ors. vs. Central Bureau of Investigation (28.03.2018)Document30 pagesAsian Resurfacing of Road Agency Pvt. Ltd. and Ors. vs. Central Bureau of Investigation (28.03.2018)Rishabh Nigam100% (1)

- Mactan - Cebu International Airport Authority vs. InocianDocument1 pageMactan - Cebu International Airport Authority vs. InocianremoveignorancePas encore d'évaluation

- LG Foods V AgraviadorDocument2 pagesLG Foods V AgraviadorMaica MahusayPas encore d'évaluation

- Vihit Namuna Annexure-XV - 270921Document1 pageVihit Namuna Annexure-XV - 270921Rajendra JanglePas encore d'évaluation

- Futrell3e Chap10Document27 pagesFutrell3e Chap10anitasengarphdPas encore d'évaluation

- Jean-Jacques Nattiez Analyses Et Interpr PDFDocument5 pagesJean-Jacques Nattiez Analyses Et Interpr PDFJosé Rafael Maldonado AbarcaPas encore d'évaluation