Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Case Digest 1

Transféré par

Hanna PentiñoDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Case Digest 1

Transféré par

Hanna PentiñoDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

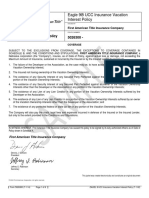

Aisporna v CA (1982)

Aisporna v CA (1982)

Facts

Mapalad Aisporna, the wife of one Rodolfo Aisporna, an insurance agent, solicited the

application of Eugenio Isidro in behalf of Perla Compana de Seguros without the

certificate of authority to act from the insurance commissioner. Isidro passed away while

his wife was issued Php 5000 from the insurance policy. After the death, the fiscal

instigated criminal action against Mapalad for violating sec 189 of the Insurance code

for feloniously acting as agent when she solicited the application form.

In the trial court, she claimed that she helped Rodolfo as clerk and that she solicited a

renewal, not a new policy from Isidro through the phone. She did this because her

husband was absent when he called. She only left a note on top of her husbands desk

to inform him of what transpired. (She did not accept compensation from Isidro for her

services)

Aisporna was sentenced to pay Php 500 with subsidiary costs in case of insolvency in

1971 in the Cabanatuan city court.

In the appellate court, she was found guilty of having violating par 1 of sec 189 of the

insurance code.

The OSG kept on repeating that she didnt violate sec 189 of the insurance code.

In seeking reversal of the judgment, Aisporna assigned errors of the appellate court:

1. the receipt of compensation was not a necessary element of the crime in par 1 of sec

189 of the insurance code

2. CA erred in giving due weight to exhibits F, F1, F17 inclusive sufficient to establish

petitioners guilt beyond reasonable doubt.

3. The CA erred in not acquitting the petitioner

Issues: Won a person can be convicted of having violated the 1

st

par of the sec 189 of

the IC without reference to the 2

nd

paragraph of the said section. Or

Is it necessary to determine WON the agent mentioned in the 1

st

paragraph of the

aforesaid section is governed by the definition of an insurance agent found on its

second paragraph

Decision: Aisporna acquitted

Ruling:

Sect 189 of the I.C., par 1 states that No insurance company doing business with the

Philippine Islands nor l any agent thereof shall pay any commission or other

compensation to any person for services in obtaining new insurance unless such person

shall have first procured from the Insurance Commissioner a certificate of authority to

act as an agent of such company as herein after provided.

No person shall act as agent, sub-agent, or broker in the solicitation of procurement of

applications for insurance without obtaining a certificate from the Insurance

Commissioner.

Par2 Any person who for COMPENSATION solicits or obtains insurance for any for any

insurance compna or offers or assumes to act in the negotiating of such insurance shall

be an insurance agent in the intent of this section and shall thereby become liable to all

liabilities to which an insurance agent is subject.

Par 3 500 pseo fine for person or company violating the provisions of the section.

The court held that the 1

st

par prohibited a person to act as agent without certificate of

authority from the commissioner

In the 2

nd

par, the definition of an insurance agent is stipulated

The third paragraph provided the penalty for violating the 1

st

2 rules

The appellate court said that the petitioner was penalized under the1st paragraph and

not the 1nd. The fact that she didnt receive compensation wasnt an excuse for her

acquittal because she was actually punished separately under sec 1 because she did

not have a certificate of authority as under par 1.

The SC held that the definition of an insurance agent was made by CA to be limited to

paragraph 2 and not applicable to the 1

st

paragraph.

The appellate court said that a person was an insurance agent under par 2 if she solicits

insurance for compensation, but in the 1

st

paragraph, there was no necessity that a

person solicits an insurance compensation in order to be called an agent.

The SC said that this was a reversible error.

The CA said that Aisporna didnt receive compensation.

The SC said that the definition of an insurance agent was found in the 2nd par of Sec

189 (check the law) The definition in the 2

nd

paragraph qualified the definition of an

agent used in the 1

st

and third paragraphs.

DOCTRINE: The court held that legislative intent must be ascertained from the

consideration of the statute as a whole. The words shouldnt be studied in isolated

explanations but the whole and every part of the statute must be considered in fixing the

meaning of any of its parts in order to pronounce the harmonious whole.

Noscitur a sociis provides that where a particular word or phrase in a statement is

ambiguous in itself, the true meaning may be made clear in the company it is fixed in. In

applying this, the court held that the definition of an insurance agent in the 2

nd

paragraph was applicable in the 1

st

paragraph.

To receive compensation be the agent is an essential element for violation of the 1

st

paragraph.

The appellate court said that she didnt receive compensation by the receipt of

compensation wasnt an essential element for violation of the 1

st

paragraph.

The SC said that this view wasnt correct owing to the American insurance laws which

qualified compensation as a qualifying factor in penalizing unauthorized persons who

solicited insurance (Texas code and snyders law)

CHINA BANKING CORPORATION and TAN KIM LIONG vs. HON. WENCESLAO

ORTEGA, as Presiding Judge of the Court of First Instance of Manila, Branch VIII,

and VICENTE G. ACABAN

G.R. No. L-34964

January 31, 1973

En banc

FACTS:

On December 17, 1968 Vicente Acaban filed a complaint in the court a quo against

Bautista Logging Co., Inc., B & B Forest Development Corporation and Marino Bautista

for the collection of a sum of money. Upon motion of the plaintiff the trial court declared

the defendants in default for failure to answer within the reglementary period, and

authorized the Branch Clerk of Court and/or Deputy Clerk to receive the plaintiffs

evidence. On January 20, 1970 judgment by default was rendered against the

defendants.

To satisfy the judgment, the plaintiff sought the garnishment of the bank deposit of the

defendant B & B Forest Development Corporation with the China Banking Corporation.

Accordingly, a notice of garnishment was issued by the Deputy Sheriff of the trial court

and served on said bank through its cashier, Tan Kim Liong. In reply, the bank cashier

invited the attention of the Deputy Sheriff to the provisions of Republic Act No. 1405

which, it was alleged, prohibit the disclosure of any information relative to bank

deposits. Thereupon the plaintiff filed a motion to cite Tan Kim Liong for contempt of

court.

In an order dated March 4, 1972 the trial court denied the plaintiffs motion. However,

Tan Kim Liong was ordered to inform the Court within five days from receipt of this

order whether or not there is a deposit in the China Banking Corporation of defendant B

& B Forest Development Corporation, and if there is any deposit, to hold the same intact

and not allow any withdrawal until further order from this Court. Tan Kim Liong moved

to reconsider but was turned down by order of March 27, 1972. In the same order he

was directed to comply with the order of this Court dated March 4, 1972 within ten (10)

days from the receipt of copy of this order, otherwise his arrest and confinement will be

ordered by the Court. Resisting the two orders, the China Banking Corporation and Tan

Kim Liong instituted the instant petition.

The pertinent provisions of Republic Act No. 1405 relied upon by the petitioners reads:

Sec. 2. All deposits of whatever nature with banks or banking institutions in the

Philippines including investments in bonds issued by the Government of the Philippines,

its political subdivisions and its instrumentalities, are hereby considered as of absolutely

confidential nature and may not be examined, inquired or looked into by any person,

government official, bureau or office, except upon written permission of the depositor, or

in cases of impeachment, or upon order of a competent court in cases of bribery or

dereliction of duty of public officials, or in cases where the money deposited or invested

is the subject matter of the litigation.

Sec 3. It shall be unlawful for any official or employee of a banking institution to disclose

to any person other than those mentioned in Section two hereof any information

concerning said deposits.

Sec. 5. Any violation of this law will subject offender upon conviction, to an

imprisonment of not more than five years or a fine of not more than twenty thousand

pesos or both, in the discretion of the court.

The petitioners argue that the disclosure of the information required by the court does

not fall within any of the four (4) exceptions enumerated in Section 2, and that if the

questioned orders are complied with Tan Kim Liong may be criminally liable under

Section 5 and the bank exposed to a possible damage suit by B & B Forest

Development Corporation. Specifically referring to this case, the position of the

petitioners is that the bank deposit of judgment debtor B & B Forest Development

Corporation cannot be subject to garnishment to satisfy a final judgment against it in

view of the aforequoted provisions of law.

ISSUE:

Whether or not a banking institution may validly refuse to comply with a court process

garnishing the bank deposit of a judgment debtor, by invoking the provisions of Republic

Act No. 1405.

HELD:

We do not view the situation in that light. The lower court did not order an examination

of or inquiry into the deposit of B & B Forest Development Corporation, as contemplated

in the law. It merely required Tan Kim Liong to inform the court whether or not the

defendant B & B Forest Development Corporation had a deposit in the China Banking

Corporation only for purposes of the garnishment issued by it, so that the bank would

hold the same intact and not allow any withdrawal until further order. It will be noted

from the discussion of the conference committee report on Senate Bill No. 351 and

House Bill No. 3977, which later became Republic Act 1405, that it was not the intention

of the lawmakers to place bank deposits beyond the reach of execution to satisfy a final

judgment. Thus:

Mr. MARCOS. Now, for purposes of the record, I should like the Chairman of the

Committee on Ways and Means to clarify this further. Suppose an individual has a tax

case. He is being held liable by the Bureau of Internal Revenue for, say, P1,000.00

worth of tax liability, and because of this the deposit of this individual is attached by the

Bureau of Internal Revenue.

Mr. RAMOS. The attachment will only apply after the court has pronounced sentence

declaring the liability of such person. But where the primary aim is to determine whether

he has a bank deposit in order to bring about a proper assessment by the Bureau of

Internal Revenue, such inquiry is not authorized by this proposed law.

Mr. MARCOS. But under our rules of procedure and under the Civil Code, the

attachment or garnishment of money deposited is allowed. Let us assume, for instance,

that there is a preliminary attachment which is for garnishment or for holding liable all

moneys deposited belonging to a certain individual, but such attachment or garnishment

will bring out into the open the value of such deposit. Is that prohibited by this

amendment or by this law?

Mr. RAMOS. It is only prohibited to the extent that the inquiry is limited, or rather, the

inquiry is made only for the purpose of satisfying a tax liability already declared for the

protection of the right in favor of the government; but when the object is merely to

inquire whether he has a deposit or not for purposes of taxation, then this is fully

covered by the law.

Mr. MARCOS. And it protects the depositor, does it not?

Mr. RAMOS. Yes, it protects the depositor.

Mr. MARCOS. The law prohibits a mere investigation into the existence and the amount

of the deposit.

Mr. RAMOS. Into the very nature of such deposit.

Mr. MARCOS. So I come to my original question. Therefore, preliminary garnishment or

attachment of the deposit is not allowed?

Mr. RAMOS. No, without judicial authorization.

Mr. MARCOS. I am glad that is clarified. So that the established rule of procedure as

well as the substantive law on the matter is amended?

Mr. RAMOS. Yes. That is the effect.

Mr. MARCOS. I see. Suppose there has been a decision, definitely establishing the

liability of an individual for taxation purposes and this judgment is sought to be executed

in the execution of that judgment, does this bill, or this proposed law, if approved,

allow the investigation or scrutiny of the bank deposit in order to execute the judgment?

Mr. RAMOS. To satisfy a judgment which has become executory.

Mr. MARCOS. Yes, but, as I said before, suppose the tax liability is P1,000,000 and the

deposit is half a million, will this bill allow scrutiny into the deposit in order that the

judgment may be executed?

Mr. RAMOS. Merely to determine the amount of such money to satisfy that obligation to

the Government, but not to determine whether a deposit has been made in evasion of

taxes.

xxx xxx xxx

Mr. MACAPAGAL. But let us suppose that in an ordinary civil action for the recovery of

a sum of money the plaintiff wishes to attach the properties of the defendant to insure

the satisfaction of the judgment. Once the judgment is rendered, does the gentleman

mean that the plaintiff cannot attach the bank deposit of the defendant?

Mr. RAMOS. That was the question raised by the gentleman from Pangasinan to which

I replied that outside the very purpose of this law it could be reached by attachment.

Mr. MACAPAGAL. Therefore, in such ordinary civil cases it can be attached?

Mr. RAMOS. That is so.

(Vol. II, Congressional Record, House of Representatives, No. 12, pp. 3839-3840, July

27, 1955).

It is sufficiently clear from the foregoing discussion of the conference committee report

of the two houses of Congress that the prohibition against examination of or inquiry into

a bank deposit under Republic Act 1405 does not preclude its being garnished to insure

satisfaction of a judgment. Indeed there is no real inquiry in such a case, and if the

existence of the deposit is disclosed the disclosure is purely incidental to the execution

process. It is hard to conceive that it was ever within the intention of Congress to enable

debtors to evade payment of their just debts, even if ordered by the Court, through the

expedient of converting their assets into cash and depositing the same in a bank.

Board of Administrators of the PVA v. Bautista GR L-37867, 22 February1982 (112 SRCA 59)First Division,

Guerrero (p): 5 concurring

Facts:

Calixto Gasilao was a veteran in good standing during the last World War that took

activeparticipation in theliberation drive against the enemy, and due to his military

service, he wasrendered disabled. The Philippine VeteransAdministration, formerly the

Philippine Veterans Board,(now Philippine Veterans Affairs Office) is an agency of the

Government charged with theadministration of different laws giving various benefits in

favor of veterans andtheir orphans/orwidows and parents. On July 23, 1955, Gasilao

filed a claim for disability pension under Section 9of Republic Act 65, with the Philippine

Veterans Board, alleging that he was suffering from PulmonaryTuberculosis

(PTB), which he incurred in line of duty. Due to Gasilaos failure to complete

hissupporting papers and submit evidence to establish his service-connected illness, his

claim wasdisapproved by the Board on 18 December 1955.On 8 August 1968, Gasilao

was able to complete hissupporting papers and, after due investigation and

processing,the Board of Administrators found outthat his disability was 100% thus he

was awarded the full benefits of section 9of Republic Act 65.Later on, Republic Act

5753 was approved on 22 June 1969, providing for an increase in the Basic pension

and additional pension for the wife and each of the unmarried minor children.

Gasilaosmonthly pension was, however, increased only on 15 January 1971, and by

25% of the increasesprovided by law, due to thefact that it was only on said date that

funds were released for thepurpose, and the amount so released was onlysufficient to

pay only 25% of the increase. On 15January 1972, more funds were released to

implement fullyRepublic Act 5753 and allow payment infull of the benefits thereunder

from said date.In 1973, Gasilao filed anaction against the Board to recover the pension,

which he claims he isentitled to, from July 1955, when he first filedhis application for

pension, up to 1968 when his pensionwas finally approved. The Board contends,

however, basedon Section 15 of Republic Act 65, thatsince the section impliedly

requires that the application filed should first beapproved by the Board of Administrators

before the claimant could receive his pension, therefore, an award of pension

benefitsshould commence from the date of approval of the application. I s

Whether Gasilao is entitled to the pension from 1955 instead of from 1968.

Held:

As it is generally known, the purpose of Congress in granting veteran pensions is to

compensatea class of men whosuffered in the service for the hardships they endured

and the dangers theyencountered, and more particularly, thosewho have become

incapacitated for work owing to sickness,disease or injuries sustained while in line of

duty. Aveteran pension law is, therefore, a governmentalexpression of gratitude to and

recognition of those who renderedservice for the country, especiallyduring times of war

or revolution, by extending to them regular monetary aid. Forthis reason, it is thegeneral

rule that a liberal construction is given to pension statutes in favor of those

entitledtopension. Courts tend to favor the pensioner, but such constructional

preference is to be consideredwith otherguides to interpretation, and a construction of

pension laws must depend on its ownparticular language. In thepresent case, Republic

Act 65 is a veteran pension law which must beaccorded a liberal construction

andinterpretation in order to favor those entitled to rights, privileges,and benefits

granted thereunder, among which arethe right to resume old positions in

government,educational benefits, the privilege to take promotion examinations, alife

pension for the incapacited,pension for widow and children, and hospitalization and

medical benefits. Upholdingthe Board that the pension awards are made effective only

upon approval of the application, this would be dependentupon thediscretion of the

Board which had been abused in this case through inaction extending for 12years. Such

stand,therefore does not appear to be, or simply is not, in consonance with the spirit

andintent of the law. Gasilaos claim was sustained.The Supreme Court modified the

judgment of the court a quo, ordering the Board of Administrators of the Philippine

Veterans Administration (now the Philippine Veterans Affairs Office) to make

Gasilaospension effective 18 December 1955 at the rate of P50.00 per month plus

P10.00 per month for eachof his then unmarriedminor children below 18, and the former

amount increased to P100.00 from 22June 1957 to 7 August 1968; anddeclaring the

differentials in pension to which said Gasilao, his wifeand his unmarried minor children

below 18 areentitled for the period from 22 June 1969 to 14January 1972 by virtue of

Republic Act 5753 subject to theavailability of Government fundsappropriated for the

purpose.

ROMAN CATHOLIC ARCHBISHOP OF MANILA vs. SOCIAL SECURITY

COMMISSION

Facts:

Roman Catholic Archbishop of Manila, thru counsel, filed a request with the respondent

Social SecurityCommission a request that they be exempted from coverage of RA No.

1161, otherwise known as theSocial Security Law of 1954 because said act is a labor

law and does not cover religious and charitableinstitutions.

Appellant contends that the term "employer" as defined in the law should following the

principle of ejusdem generis be limited to those who carry on "undertakings or activities

which have the element of profit or gain, or which are pursued for profit or gain,"

because the phrase ,activity of any kind" in thedefinition is preceded by the words "any

trade, business, industry, undertaking."

Respondent denied the request and the petitioners motion for reconsideration.

Act provides in the System shall be compulsory upon all members between the age of

sixteen and sixty years inclusive, if they have been for at least six months at the service

of an employer who is a member of the System, Provided,that the Commission may not

compel any employer to become member of the System unless he shall have been in

operation for at least two years and has at the time of admission, if admitted for

membership during thefirst year of the System's operation at least fifty employees, and

if admitted for membership the following year of operation and thereafter, at least six

employees

employer any person, natural or juridical, domestic or foreign, who carries in the

Philippines any trade, business, industry, undertaking, or activity of any kind and uses

the services of another person who is under hisorders as regards the employment,

except the Government and any of its political subdivisions, branches

or instrumentalities, including corporations owned or controlled by the Government"

(par. [c], see. 8)employee any person who performs services for an 'employer' in which

either or both mental and physicalefforts are used and who receives compensation for

such services"

(par. [d], see. 8).Employment covers any service performed by an employer except

those expressly enumerated thereunder,like employment under the Government, or any

of its political subdivisions, branches or instrumentalitiesincluding corporations owned

and controlled by the Government, domestic service in a private home,employment

purely casual, etc.

(paragraph [i] of said section 8)

Issue:

Whether or not the term employer following the principle of ejusdem generis be limited

to those who carry onactivities for gain.

Held:

No

Ratio:

ejusdem generis applies only where there is uncertainty. It is not controlling where the

plain purpose andintent of the Legislature would thereby be hindered and defeated.

Contributions are intended for the protection of said employees against the hazards of

disability, sickness, old age and death in line with the constitutional mandate to promote

social justice to in sure the well-being and economic security of all the people.

The law explicitly states those which are not covered by the contribution and the

petitioner is not among those cited.

significant to note that when Republic Act No. 1161 was enacted, services performed in

the employ of institutions organized for religious or charitable purposes were by express

provisions of said Act excludedfrom coverage thereof (sec. 8, par. [j] subpars. 7 and 8).

That portion of the law, however, has been deletedby express provision

of Republic Act No. 1792, which took effect in 1957. This is clear indication that the

Legislature intended to include charitable and religious institutions within the scope of

the law.

David v COMELEC

Panganiban, 1997

FACTS:

David, in his capacity as barangay chairman and as president of the Liga ng mga

Barangay sa Pilipinas, filed apetition to prohibit the holding of the barangay election

scheduled on the second Monday of May 1997.Meanwhile, Liga ng mga Barangay

Quezon City Chapter also filed a petition to seek a judicial review by certiorari

to declare as unconstitutional:

(1) Section 43(c) of R.A. 7160;

(2) COMELEC Resolution Nos. 2880 and 2887fixing the date of the holding of the

barangay elections on May 12, 1997 and other activities related thereto; and,

(3) The budgetary appropriation of P400 million contained in Republic Act No. 8250

(General AppropriationsAct of 1997) intended to defray the costs and expenses in

holding the 1997 barangay elections.

Petitioners contend that under RA 6679, the term of office of barangay officials is 5

years. Although the LGCreduced the term of office of all local elective officials to three

years, such reduction does not apply to barangayofficials.

As amicus curiae,former Senator Aquilino Q. Pimentel, Jr. urges the Court to deny the

petitions.

ISSUES & HELD:

Which law governs the term of office of barangay officials: RA 7160 or RA 6679? (RA

7160 3 years)

Is RA 7160 insofar as it shortened such term to only three years constitutional? (YES)

Are petitioners estopped from claiming a term other than that provided under RA 7160?

(YES)

RATIO:

Clear Legislative Intent and Design to Limit Term to Three Years

RA 7160 was enacted later than RA 6679. It is basic that in case of an irreconciliable

conflict between two laws,the later enactment prevails. ( Legis posteriores priores

contrarias abrogant .)

During the barangay elections held on May 9, 1994 (second Monday), the voters

actually and directly electedone punong barangay and seven kagawads (as in the

Code).

In enacting the general appropriations act of 1997, Congress appropriated the amount

of P400 million to coverexpenses for the holding of barangay elections this year.

Likewise, under Sec. 7 of RA 8189, Congress ordained

that a general registration of voters shall be held immediately after the barangay elections in 1997.

These areclear and express contemporaneous statements of Congress that barangay

officials shall be elected this May, inaccordance with Sec. 43-c of RA 7160.

In

Paras vs. Comelec,,this Court said that the next regular election involving the barangay office

concerned isbarely 7 months away, the same having been scheduled in May,

1997. This judicial decision is part of the legal system of the Philippines (NCC 8)

RA 7160 is a codified set of laws that specifically applies to local government units. It

specifically and definitivelyprovides in its Sec. 43-c that the term of office of barangay officials

shall be for three years. It is a special provision that applies only to the term of barangay

officials who were elected on the second Monday of May1994. With such particularity,

the provision cannot be deemed a general law.

Three-Year Term Not Repugnant to Constitution

barangay officials. It merely left the determination of such term to the lawmaking body,

without any specific limitation or prohibition,thereby leaving to the lawmakers full

discretion to fix such term in accordance with the exigencies of publicservice. It must be

remembered that every law has in its favor the presumption of constitutionality.

Thepetitioners have miserably failed to discharge this burden and to show clearly the

unconstitutionality they aver.

As may be determined by law; moreprecisely, as provided for in the Local Autonomy Code

(Sec 43-c limits their term to 3 years)

.

Petitioners Estopped From Challenging Their Three-Year Terms

ran for and were elected to,under the law governing their very claim to such offices:

namely, the LGC.

Petitioners belated claim of ignoranceas to what law governed their election to office in

1994 is unacceptable because under NCC 3

, ignorance of thelaw excuses no one from compliance therewith.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Sample Format of Investigation ReportDocument1 pageSample Format of Investigation ReportDon So Hiong100% (7)

- SalesmanDocument3 pagesSalesmanHanna PentiñoPas encore d'évaluation

- Philippine Institute of ArbitratorsDocument68 pagesPhilippine Institute of ArbitratorsAnonymous 5k7iGyPas encore d'évaluation

- Arb Agree PDFDocument30 pagesArb Agree PDFRuel Benjamin BernaldezPas encore d'évaluation

- Turkesa Vs ValeraDocument7 pagesTurkesa Vs ValeraHanna PentiñoPas encore d'évaluation

- Marketing Plan Targets For 1 YearDocument1 pageMarketing Plan Targets For 1 YearHanna PentiñoPas encore d'évaluation

- BTR Functions Draft 6-1-15Document16 pagesBTR Functions Draft 6-1-15Hanna PentiñoPas encore d'évaluation

- Land Titles: A C B O 2007 Civil LawDocument28 pagesLand Titles: A C B O 2007 Civil LawMiGay Tan-Pelaez86% (14)

- BTR Functions Draft 6-1-15Document16 pagesBTR Functions Draft 6-1-15Hanna PentiñoPas encore d'évaluation

- Reviewer On Land Titles and DeedsDocument23 pagesReviewer On Land Titles and Deedsmcben9100% (5)

- Land Titles: A C B O 2007 Civil LawDocument28 pagesLand Titles: A C B O 2007 Civil LawMiGay Tan-Pelaez86% (14)

- Legal EthicsDocument12 pagesLegal EthicsHelen Grace AbudPas encore d'évaluation

- Chaves vs. PEA and Amari Corp, G.R. No. 133250 July 9, 2002Document35 pagesChaves vs. PEA and Amari Corp, G.R. No. 133250 July 9, 2002KennethQueRaymundoPas encore d'évaluation

- Employee Requisition FormDocument1 pageEmployee Requisition FormHanna PentiñoPas encore d'évaluation

- CASES For STATCON AUG28Document41 pagesCASES For STATCON AUG28Hanna PentiñoPas encore d'évaluation

- ART4 #7 Case Digest On People V. Estrada (333 Scra 699 (2000) )Document23 pagesART4 #7 Case Digest On People V. Estrada (333 Scra 699 (2000) )Dana GoanPas encore d'évaluation

- Cases 2010Document93 pagesCases 2010Hanna PentiñoPas encore d'évaluation

- Qua Chee Gan VDocument2 pagesQua Chee Gan VmfspongebobPas encore d'évaluation

- When Is It Construction and When Is It Judicial Legislation?Document22 pagesWhen Is It Construction and When Is It Judicial Legislation?Hanna PentiñoPas encore d'évaluation

- When Is It Construction and When Is It Judicial Legislation?Document22 pagesWhen Is It Construction and When Is It Judicial Legislation?Hanna PentiñoPas encore d'évaluation

- Statutory Cases Case Title: G.R. No. L-19650 (September 29, 1966)Document82 pagesStatutory Cases Case Title: G.R. No. L-19650 (September 29, 1966)Nong Mitra100% (6)

- Case Digest 1Document12 pagesCase Digest 1Hanna PentiñoPas encore d'évaluation

- Statutory Cases Case Title: G.R. No. L-19650 (September 29, 1966)Document82 pagesStatutory Cases Case Title: G.R. No. L-19650 (September 29, 1966)Nong Mitra100% (6)

- Group 4 Report - Statutory ConstructionDocument10 pagesGroup 4 Report - Statutory ConstructionHanna PentiñoPas encore d'évaluation

- Aisporna Vs CADocument5 pagesAisporna Vs CAHanna PentiñoPas encore d'évaluation

- Legal Ethics CasesDocument78 pagesLegal Ethics CasesHanna PentiñoPas encore d'évaluation

- Legal EthicsDocument12 pagesLegal EthicsHelen Grace AbudPas encore d'évaluation

- Types of LawyersDocument5 pagesTypes of LawyersHanna PentiñoPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Digest Ethics 1Document5 pagesCase Digest Ethics 1Hanna PentiñoPas encore d'évaluation

- Code of Professional ResponsibilityDocument13 pagesCode of Professional ResponsibilityHanna PentiñoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- InventDocument172 pagesInventSafianu Abbas Abdul-RaheemPas encore d'évaluation

- HR Due Diligence Training Final2Document52 pagesHR Due Diligence Training Final2kaustubhsohoni100% (2)

- Part 3 - Bus Tax (Banggawan 2019)Document75 pagesPart 3 - Bus Tax (Banggawan 2019)viox reyesPas encore d'évaluation

- Annual Premium Statement: Bhupesh GuptaDocument1 pageAnnual Premium Statement: Bhupesh GuptaBhupesh GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Adjunct Health Insurance Certification FormDocument2 pagesAdjunct Health Insurance Certification FormElena GerashchenkoPas encore d'évaluation

- DMLCIIDocument2 pagesDMLCIIVu Tung LinhPas encore d'évaluation

- PolicyPrint DoDocument8 pagesPolicyPrint DoJabeen JuwaleyPas encore d'évaluation

- Signature Not Verified: Date: 18-JAN-2024 Ref No: 221797Document6 pagesSignature Not Verified: Date: 18-JAN-2024 Ref No: 221797Miten VoraPas encore d'évaluation

- Disability Critical Illness Medical Reimbursement or Hospitalization Claim FormDocument5 pagesDisability Critical Illness Medical Reimbursement or Hospitalization Claim FormAkoSiAudreyPas encore d'évaluation

- REVISED ORGANIC ACT 1954 3 Rights and ProhibitionsDocument22 pagesREVISED ORGANIC ACT 1954 3 Rights and ProhibitionsGenevieve WhitakerPas encore d'évaluation

- Great Pacific Life Vs CADocument2 pagesGreat Pacific Life Vs CADann ThrowerPas encore d'évaluation

- Walkovszky v. CarltonDocument8 pagesWalkovszky v. CarltonAmeya KulkarniPas encore d'évaluation

- Reliance General Insurance Company Limited: Reliance Private Car Package Policy-ScheduleDocument9 pagesReliance General Insurance Company Limited: Reliance Private Car Package Policy-Schedulehgfh hgfPas encore d'évaluation

- Itinerary: 1E PNR: Etkt NBR: Conj NBR: Airline PNR: Name: Lin/WeiDocument3 pagesItinerary: 1E PNR: Etkt NBR: Conj NBR: Airline PNR: Name: Lin/WeiWILSON LEEPas encore d'évaluation

- 003 UCC Insurance Vacation Interest Policy (UCC01-NP Rev.07-01-14) PDFDocument7 pages003 UCC Insurance Vacation Interest Policy (UCC01-NP Rev.07-01-14) PDFGerardo Enrique AlfonsoPas encore d'évaluation

- Annaul Report PDFDocument268 pagesAnnaul Report PDFMohd kasimPas encore d'évaluation

- Strategies For Trading Inverse VolatilityDocument6 pagesStrategies For Trading Inverse VolatilityLogical InvestPas encore d'évaluation

- Ameritas Dental BrochureDocument4 pagesAmeritas Dental BrochureSocialmobile TrafficPas encore d'évaluation

- Washington Health Benefit Exchange: Insurance 101Document37 pagesWashington Health Benefit Exchange: Insurance 101tarun.batra4686Pas encore d'évaluation

- Glove Box GuideDocument2 pagesGlove Box Guideevil_ironmindPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit Rates Build UpDocument6 pagesUnit Rates Build UpBernard KagumePas encore d'évaluation

- Consti Cases SummaryDocument17 pagesConsti Cases SummaryBrigittePas encore d'évaluation

- Sample Exam QuestionsDocument6 pagesSample Exam QuestionsTôn Nữ Hương Giang100% (1)

- Seven Principles of Insurance With ExamplesDocument7 pagesSeven Principles of Insurance With Examplessagar111033Pas encore d'évaluation

- Philippine International Trade Corp v. COA, G.R. No. 183517, June 22, 2010Document1 pagePhilippine International Trade Corp v. COA, G.R. No. 183517, June 22, 2010MonicaCelineCaroPas encore d'évaluation

- FWA Solution From MetamorphosysDocument7 pagesFWA Solution From Metamorphosyshaophantuan1Pas encore d'évaluation

- Financial Planning QuestionnaireDocument7 pagesFinancial Planning QuestionnairerosanajonesPas encore d'évaluation

- Service Tax Rules, 1994Document75 pagesService Tax Rules, 1994Gens GeorgePas encore d'évaluation

- What Is Insured? What Is Not Insured?: Travel InsuranceDocument2 pagesWhat Is Insured? What Is Not Insured?: Travel InsurancemikeionaPas encore d'évaluation

- CIDC Model EPC Agreement 22032018Document342 pagesCIDC Model EPC Agreement 22032018Chetan Kumar jainPas encore d'évaluation