Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Measuring Success With Claims Management

Transféré par

Mohammed 3014Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Measuring Success With Claims Management

Transféré par

Mohammed 3014Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Measuring Success with Claims Management

*

Stuart Ockman, President

Ockman & Borden Associates

Wallingford, Pennsylvania

*

Originally published in the Proceedings of the Project Management Institute.

INTRODUCTION

Let's examine a typical $30 million construction project with an

increasingly common problem, a $10 million plus end-of-contract delay

and disruption claim. How can we avoid similar claims on our projects?

Let's look at the corollary to an effective project management programby

the contractor: an effective claims management programby the owner.

And in particular, let's look at how an effective claims management

programwill avoid what can be millions of dollars of claims preparation

and legal fees spent by both the contractor and the owner long after the

project is complete.

The major categories of contractor claims during a project are the result

of delays, (e.g. failure to provide timely access or late vendor drawing

approval), changes and differing site conditions. However, acts of God,

value engineering change proposals, defective specifications, etc., may

also result in disputes. Similarly, lack of performance by the contractor

which may result in termination for default is a problemfromthe other

side. In order to measure the impact of these problems a good network-

based project management (CPM) system is essential with periodic

updates by the contractor at least once a month. We'll examine how to

specify such a system, what to look for when approving the contractor's

initial schedule submittals, and how to properly adjust the schedule to

account for owner delays.

Once a reasonable as-planned schedule has been approved, it becomes

the benchmark for measuring contractor and owner performance on the

project. We'll look at the basic tool for determining the effect of a delay

or change on the project milestones, the time impact analysis. What

should a time impact analysis include and how can it be incorporated in

the approved schedule? We'll also look at how to make sure the owner

gets what he pays for when he executes a change order. It's not always

easy.

Finally, we'll look at establishing goals for future projects. In particular,

how can you be sure (1) that the amount billed to date is fair and

adequate compensation for the work performed, and (2) that the current

contract amount is fair and adequatecompensation to performthe current

scope of work by the current contract completion date? If you can't be

sure, then your claims management programneeds review and you may

be heading toward an end-of-contract claim.

THE PROJECT

The project involves construction of the Cold Spring Lane Station &

Line and the Rogers/Reisterstown Line Contracts for the Baltimore

Region Rapid Transit System(BRRTS).

The $16.5 million Cold Spring Lane Contract consists of a double track

aerial structure, a center platformstation at Cold Spring Lane, a traction

power substation, and related sitework:

1. Aerial Structure - approximately 9140 feet of double precast

concrete girder trackway resting on cast-in-place concrete piers

with either spread footings or pile supported footings. As the

girders are erected, the spaces between adjacent girder ends are

filled with cast-in-place concrete; concrete walls supporting the

precast safety walk and sound barrier panels are placed; conduits

are installed beneath the safety walk; and safety walk and sound

barrier panels are installed to complete the structure.

2. Cold Spring Lane Station - a three level structure with entrances at

grade level and, via an aerial pedestrian walkway, directly from

the parking lot to the mezzanine; fare collection and the station

control center at the mezzanine; and access to the transit vehicles

at the platformlevel. The station is cast-in-place architectural

concrete with aluminumclad canopy and skylights, brick and

granite pavers, and stainless steel and granite accent panels.

3. Traction Power Substation - a single story structure with

cast-in-place concrete foundation, grade slab and partial basement;

concrete block walls; steel roof joists, and built-up roofing.

4. Sitework including clearing and grubbing, support of excavation,

utilities, paving, curbs and gutters, sidewalks, fencing, guard rails,

seeding and sodding.

The $11.4 million Rogers/Reisterstown Contract consists of an aerial

trackway structure, bridges over Northern Parkway, sub-ballasted

trackway on grade and on retained fill, a traction power substation and

related sitework:

1. Aerial Structure - approximately 4220 feet of single, double and

four track aerial structure including precast and cast-in-place

concrete girders. Construction is similar to the Cold Spring Lane

Contract except that the Rogers/Reisterstown Contract utilizes

single track piers while the standard Cold Spring Lane pier

supports two tracks.

2. Trackway on Grade and Retained Fill - approximately 3340 feet

of double and three track construction including six retained fill

abutments, sub-ballast, and 3630 feet of retaining walls.

3. Northern Parkway Bridges - three composite steel I-beamgirder

and concrete deck bridges supported by cast-in-place concrete

piers in the median, and abutments on either side of the Parkway.

4. Rogers Avenue Traction Power Substation - a single story

cast-in-place concrete structure located in retained fill beneath the

2

trackway. One wall of the substation is above grade in a retaining

wall.

5. Sitework including clearing and grubbing, support of excavation,

preload embankment, concrete slope protection, utilities, paving,

curbs and gutters, fencing, guard rails, and seeding.

THE PROJECT MANAGEMENT (CPM) SYSTEM

The scheduling specification for the Cold Spring Lane and

Rogers/Reisterstown Contracts is similar to the network analysis system

(NAS) specification used by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. It

specifies that:

1. The contractor is responsible for preparing and maintaining a

detailed progress schedule.

2. The detailed progress schedule shall be used to plan, organize and

execute the work; record and report actual performance and

progress; and forecast remaining work.

3. The progress schedule shall be submitted as a detailed network

diagramcomparable to that described in the Associated General

Contractors' Manual, CPM in Construction.

4. The detailed network diagramshall be supported by computerized

schedule reports, a manpower requirements forecast and a cash

flow projection.

5. A preliminary progress schedule shall be prepared and submitted

within 15 days of the notice to proceed, showing the work to be

performed during the first 90 days and the contractor's general

approach to the remaining work.

6. The contractor's detailed network diagram is to be submitted

within 45 days after receipt of notice to proceed.

7. Network activities shall include:

$ Procurement, fabrication, delivery, installation and testing

of major materials and equipment

$ Submittal and approval of shop drawings and material

samples

$ Availability of work areas

$ Delivery of owner furnished equipment

$ Interfaces with preceding, concurrent and follow-on

contractors

$ Manpower, material and equipment restrictions.

8. The selection and number of activities are subject to the approval

of the Engineer.

9. Estimated activity durations are to be in working days.

10. Construction activity durations shall not be more than 20

workdays unless approved by the Engineer.

11. Activity durations shall reflect manpower and resource planning

under contractually defined on-site working conditions.

12. The contractor shall supplement the initial network analysis with

information describing construction methods and resource

restraints so that the Engineer can evaluate the network diagram

for usefulness in monitoring job progress.

13. The network analysis shall include computerized schedule reports

sorted by activity number, early start, late finish and total float.

14. The contractor shall maintain full-time staff on the jobsite with

responsibility for updating the mathematical analysis (computer

printouts) and revising the network diagrams when necessary.

15. The contractor shall submit a manpower requirements forecast, in

accordance with the detailed network diagram, including:

$ Graphical manpower displays by principal trade and total

work force

$ A description of the type and number of work crews and

typical crew composition over the life of the project

$ Manpower relationships to the major work elements.

16. The contractor shall submit a cash flow projection graphically

displaying the estimated cash drawdown over the life of the

project.

17. The contractor shall review the initial schedule submittal with the

Engineer. Any revisions necessary shall be resubmitted within 15

days after review.

18. The Engineer will verify that the progress schedule and supporting

analysis satisfy the contract requirements.

19. The contractor shall submit monthly updates of the mathematical

analysis (computer printouts).

20. The contractor shall also submit a narrative report with each

monthly update including a description of the problemareas,

current and anticipated; delaying factors and their impact; and an

explanation of corrective actions taken or proposed.

21. The contractor shall submit a revised detailed network diagram

and supporting analysis whenever:

$ A change or delay significantly affects contract milestones

or the sequence of activities

$ The contractor changes any sequence of activities affecting

the critical path, or significantly changes the approved

work plan

$ In the opinion of the Engineer, the approved work plan is

no longer useful for planning the work and evaluating the

contractor's performance.

22. The contractor shall submit a time impact analysis when proposed

change orders are initiated or delays are experienced. The time

impact analysis shall demonstrate:

3

$ The impact of each change or delay on achieving the

contract milestone dates

$ How the contractor proposes to incorporate the change or

delay into the detailed progress schedule.

The time impact analysis shall be submitted within 30 days after a

delay occurs or a proposed change is identified. When both the

contractor and the Engineer agree on the impact of a change or

delay, the appropriate network logic revisions shall be

incorporated in the next monthly update of the detailed progress

schedule.

When the contractor and Engineer cannot agree on an appropriate

time extension before the next monthly schedule update, the

contractor shall incorporate logic revisions reflecting an interim

time extension as determined by the Engineer.

23. Float or slack is not time for the exclusive use or benefit of either

the owner or the contractor.

24. Time extensions will be granted only to the extent that equitable

time adjustments for the affected activities exceed the total float or

slack along the paths involved.

The one important difference between the BRRTS Specification and the

NAS requirements of the Corps of Engineers is that the Corps specifies

that a monetary value be assigned to applicable activities and the

schedule be used for requesting payment for work accomplished. The

Corps requirement not only assures timely monthly updating, but also

insures that both the contractor and the owner agree each month on

activity percent complete.

SCHEDULE APPROVAL

Too often schedule reviews are only cursory at best. With a proper

scheduling specification, the approved schedule becomes a benchmark

for assessing the contractor's performance throughout the project. It is

the basis for negotiating equitable time extensions for changes and

owner-caused delays and, thus, vital for determining equitable

compensation for delay damages. As the benchmark for measuring

performance, the schedule also becomes the owner's most effective tool

(or weapon) for keeping the project on schedule.

With so much importance resting on the initial approved progress

schedule, a thorough and timely review is vital. The following key items

must be considered:

1. Is It Reasonable? - This is the acid test. Does the schedule

accurately represent the contractor's thinking and will its

implementation result in the timely and efficient execution of the

project? Are the activity durations realistic considering

reasonable crew sizes, efficiency and equipment availability? Do

the logical restraints accurately reflect planned crew movement

and availability of resources?

The initial schedule submittal on the Rogers/ Reisterstown

Contract indicated the need for three clearing and grubbing crews

to work simultaneously early in the project to achieve the contract

milestones. However, the contractor's real plan (the one not

reflected by the schedule) was to use only a single crew.

Obviously the real plan and the approved plan must be one and

the same for the schedule to be effective.

2. Does It Meet the Contract Milestones? - This is extremely

important but, too often, it is the only criteria used for schedule

review and approval. Many schedule reviewers seemto believe

that if the schedule meets the contract completion milestones, it

complies with the contract. This is only true if it is reasonable,

represents the contractor's thinking, and is at the appropriate level

of detail.

3. What is the Appropriate Level of Detail? - On the Cold Spring

Lane and Rogers/Reisterstown Contracts, the contractor was

required to show network activities for:

$ procurement, fabrication, delivery, installation and testing

of major materials and equipment;

$ submittal and approval of shop drawings and material

samples;

$ availability of work areas;

$ delivery of owner furnished equipment;

$ interfaces with preceding, concurrent and follow-on

contractors; and

$ manpower, material and equipment restrictions.

Also, construction activity durations were to be less than or equal

to 20 workdays.

Still, both the initial and approved Cold Spring Lane schedules

included no procurement, fabrication, delivery and testing

activities; only ten activities for submittal and approval; no

activities indicating required delivery of owner furnished

equipment; and no interfaces with preceding, concurrent and

follow-on contractors other than those identified by contract

milestones.

Make sure that schedule submittals meet all the contract provisions prior

to approval.

THE TIME-SCALED NETWORK DIAGRAM

One of the problems confronting the owner in schedule review and

approval is that the traditional tools for scheduling, the logic diagramand

the computer printout are not easy to read or to fully comprehend. The

traditional logic diagramwith circles and arrows, dummies (sometimes

flowing fromright to left), and off-page connectors is often confusing to

the preparer and almost unintelligible to the reviewer. This is because

there is no easy way to see which activities are going on at the same

time. With computer printouts, it's easier to see which activities are

going on at the same time (e.g. with early start barcharts). However, with

traditional computer printouts it's difficult to follow the logical

relationships among activities. The solution is the time-scaled network

diagram. By requiring a time-scaled logic diagramas part of the initial

schedule submittal, not only is it an order of magnitude easier to review

and approve the initial schedule, but also errors in the initial schedule

submittal are substantially reduced by forcing the contractor to draw the

network logic to a time-scale.

4

COST ON ACTIVITIES

What good is a reasonable, approved progress schedule if it is not used

throughout the project? Not much. Sometimes it's very difficult to

insure that the schedule is effectively used by the contractor. However,

it's easy to insure that the schedule is updated monthly with accurate

estimates of activity percents complete and hopefully accurate actual start

and finish dates and remaining duration estimates as well. Just require

the contractor to assign costs to applicable activities and use the schedule

to request payment for work accomplished. By tying progress payments

to the monthly schedule updates, timely schedule updating is assured.

By contrast, schedule updates on the Cold Spring Lane Contract were

four to eight months apart after the initial schedule was approved.

Of course, using the schedule for progress payments introduces other

considerations in schedule approval including:

1. Front End Loading - Do the activity costs represent an equitable

amount for the work involved or will the contractor have been

paid for ninety percent of the work when twenty-five percent

remains to be done?

2. What Costs Are Included and When Is an Activity Complete? -

For example, does the activity, Form, Rebar and Place Mezzanine

Beams include costs for form stripping, scaffold removal,

patching and finishing? Or, is the activity complete when the

concrete is placed?

THE SCHEDULE REVIEW CONFERENCE

The schedule review conference should be held within a day or two of

the initial schedule submittal. On the Cold Spring Lane and

Rogers/Reisterstown Contracts, the schedules were submitted on June 23

and the schedule review conference was held on December 13. Prompt

schedule approval is in the interest of both the contractor and the owner

so that both parties should push for a timely conference and speedy

schedule approval. At the schedule review conference, the contractor's

superintendent should explain his plan in general terms, and the owner

should verify that the schedule reflects that plan. Any questions about

reasonableness and conformance with the contract requirements should

be discussed, and required changes and additions should be identified if

necessary for approval. The contract should specify the amount of time

allotted for the contractor to make the necessary revisions and resubmit

the schedule, in this case fifteen days.

TIME IMPACT ANALYSIS

The BRRTS Contracts state that "When proposed change orders are

initiated or delays are experienced, submit to the Engineer a written Time

Impact Analysis illustrating the influence of each change or delay on any

specified intermediate milestone dates and completion dates". The

Contracts further state that "Each Time Impact Analysis shall

demonstrate how the Contractor proposes to incorporate the change or

delay into the detailed progress schedule" and shall be "based on revised

activity logic and durations". But, what is a Time Impact Analysis?

By now, the term"Time Impact Analysis" should be as widely known in

the industry as the term"CPM". However, not only within the industry

in general, but also among the experts testifying on the merits of delay

and disruption claims, there seems to be a widespread lack of

understanding of this straightforward concept.

A time impact analysis is a step-by-step, network-based scheduling

method for evaluating the effect of a change or delay on achieving the

project milestone completion dates. Since most contract scheduling

specifications state that time extensions will be granted only to the extent

that equitable time adjustments for the affected activities exceed the total

float or slack available at the time a delay occurs or notice to proceed

with a change is issued, the time impact analysis methodology was

developed to demonstrate whether a change or delay exceeds the

available total float.

The steps for performing a time impact analysis during construction are:

1. Update the approved progress schedule to reflect the status of

construction immediately prior to the change or delay. This

update becomes the adjusted base schedule for measuring the

impact of the change.

2. Identify the scope of the change or the extent of delay.

3. Identify the activities affected by the change or delay including

any new activities required to perform changed or additional

work.

4. Prepare a subnetwork showing the sequence of activities required

to performthe changed work or to identify the impact of the

delay. The subnetwork should identify all interfaces with the

adjusted base schedule (see Step 1).

5. Develop support for the subnetwork from contract drawings,

sketches, correspondence, estimates, etc.

6. Determine whether incorporating the subnetwork logic in the

adjusted base schedule will impact any contract milestone dates.

The subnetwork and supporting documents along with the adjusted base

schedule are the time impact analysis. The time impact analysis should

be reviewed with the owner's representative to obtain approval for

incorporating the proposed subnetwork in the next schedule update.

And, if the time impact analysis indicates an impact on any contract

interimmilestone (i.e. if the change or delay exceeds the available float),

a contract modification must be negotiated with the owner to adjust the

affected milestone dates. If a change or owner-caused delay impacts the

contract completion date, the contract modification must be negotiated

for both a contract time extension and damages for delay.

A time impact analysis can also be performed upon completion of a

construction project to demonstrate entitlement to damages for delay.

The steps for performing an after the fact time impact analysis are:

1. Develop a reasonable as-planned schedule. The purpose of the

reasonable as-planned schedule is to illustrate the contractor's

original work plan to performthe scope of work in accordance

with the contract terms and within the specified period of time. If

a contemporaneous original progress schedule was prepared (and

particularly if the original progress schedule was approved by the

owner), the original progress schedule (with appropriate

adjustments to make it reasonable, if required) becomes the

reasonable as-planned schedule. The reasonable as-planned

schedule is the benchmark for measuring the impact of subsequent

changes or delays.

5

2. Develop an as-built schedule to illustrate the actual sequence and

performance of construction. The as-built schedule is developed

fromcontemporaneous project documents including schedules,

daily reports, diaries, time sheets, correspondence, progress

photographs, etc.

3. Compare the contractor's actual performance (the as-built

schedule) to his original plan (the reasonable as-planned schedule)

and identify chronologically the first activity which actually

started or finished after its scheduled late start or finish date (i.e.

the first activity which exceeded the float available). The delay to

the first activity exceeding the float available is the first

controlling delay experienced on the project or the first delay

impacting a contract milestone. The date when the first

controlling delay was resolved becomes the date of occurrence of

Impact No. 1.

4. Update the reasonable as-planned schedule to reflect (1) actual

progress to the date of occurrence of Impact No. 1, (2) the impact

of the controlling delay, and (3) any changes in the contractor's

plan for achieving the contract milestones reflected in

contemporaneous schedule updates or other contemporaneous

project documents. The updated reasonable as-planned schedule

becomes the adjusted benchmark for measuring the impact of the

next controlling delay.

5. Repeat steps 3 and 4 until all controlling delays have been

identified. Since the purpose of an after the fact time impact

analysis is to identify all schedule related events affecting each

interimcontract milestone as well as contract completion, it may

be necessary to show schedule improvements (e.g. where the

contractor performs two critical activities, originally scheduled

sequentially, in parallel to regain lost time) and schedule revisions

as impacts too.

6. Identify the causes of each impact fromthe project records. Be

sure to consider excusable, noncompensable delays (e.g. abnormal

weather or work stoppages) in determining equitable time

adjustments for each impact.

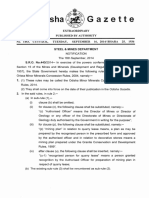

Figure 1, on the following page, is a sample time impact analysis

showing two controlling delays to achieving the "Building Enclosed"

contract milestone.

1. The As-Planned Schedule shows the approved logic for achieving

the September 1, 1986, contract milestone date (Step 1).

2. The As-Built Schedule shows the contractor's actual performance

developed fromthe project records (Step 2).

3. By comparing the As-Planned Schedule to the As-Built Schedule,

the first controlling delay to achieving the contract milestone can

be identified as the delayed start of steel erection. This delay was

resolved on May 26, 1986, the date of occurrence of Impact No. 1

(Step 3).

4. Impact No. 1 shows the contractor's actual performance to the left

of the date of occurrence and the contractor's adjusted plan for

achieving the contract milestone to the right of the date of

occurrence. Note that steel erection actually started 40 workdays

later than planned; and, since steel erection was critical to

achieving the contract milestone, the projected milestone

completion date has been delayed by 40 workdays (Step 4).

5. The next (and final) controlling delay, Impact No. 2, was the late

finish of glass and glazing. Since this delay was resolved when

the contract milestone was achieved, Impact No. 2 has been

shown together with the As-Built Schedule on the Time Impact

Analysis. Glass and glazing took three weeks longer than

planned, delaying the projected milestone completion by fifteen

additional workdays (Step 5).

6. The project records indicate that the start of steel erection was

delayed by eight weeks, or 40 work days, by a strike at the

structural steel fabricator's plant entitling the contractor to an eight

week excusable, noncompensable delay. From the notice to

proceed to the date of occurrence of Impact No. 1, the contractor

experienced no abnormal weather. Thus, as of May 26, 1986, the

date of occurrence of Impact No. 1, the properly adjusted

milestone completion date is October 27, 1986, and the contractor

is on schedule. The project records indicate that the late finish of

glass and glazing was due to the untimely performance of the

glazing subcontractor. However, fromthe date of occurrence of

Impact No. 1 to the actual milestone completion date, the

contractor experienced five work days of abnormal weather.

Thus, the properly adjusted milestone completion date at the

actual milestone completion is November 3, 1986, and the

contractor is liable for actual or liquidated damages, if any, for

finishing ten work days behind schedule (Step 6).

On the Cold Spring Lane Contract, the contractor submitted a narrative

"time impact analysis" alleging six to nine months of delay to all contract

milestones. The contractor's time impact analysis included a revised

schedule logic diagramand computer printout where the delays to each

contract milestone were "demonstrated" by assigning constraints to

downstreamactivities, artificially extending the schedule for achieving

each milestone and creating float for activities scheduled prior to the

constraints. The contractor's revised schedule was presented as reflecting

progress two months after notice to proceed when the contractor had

experienced a controlling delay to the contract milestone dates of one

week or less, and not the six to nine months claimed.

CHANGE ORDERS

Implicit in measuring success with claims management is successful

negotiation of change orders. As an owner, make sure you get what you

pay for. Don't negotiate a change order for a phantomchange!

PHANTOM CHANGES

There are at least two broad categories of phantomchanges: first, a

change order that pays a second time for work included in the original

contract (e.g., a change order for relocating pier cap reinforcing steel to

clear anchor bolt sleeves and canopy support brackets when the ACI

Code states that "Bars may be moved as necessary to avoid interference

with other reinforcing steel, conduits, or embedded items"), and second,

a change order that pays for a contractor's best efforts without specifying

an end result (e.g., a change order for overtime to regain time lost due to

previous delays. The net result of this type of phantomchange on one

project was that an owner negotiated a change order for $500,000 in

overtime premiums and achieved no gain in time at all).

5

J AN FEB MAR APR MAY J UN J UL AUG SEP OCT NOV

1986

1986

J UN J AN FEB APR MAR MAY OCT AUG J UL SEP NOV

J UN J AN FEB APR MAR MAY OCT AUG J UL SEP NOV

J UN

13

24

31

6

12

9

1

30 25

25

30

Building

Enclosed

7

4 25

25

20

20

27

Building

Enclosed

26

17

Building

Enclosed

Date of

Occurrence

May 26, 1986

1986

Time Impact Analysis

Figure 1

TIMELY NEGOTIATIONS

Timely negotiations are a necessity. In order to assure prompt payment

for changed work, it is imperative to submit prompt and reasonable

estimates and to reach an early agreement on the change order amount,

prior to the next invoice date if possible. The BRRTS Contracts required

that an estimate be submitted "within 30 days after receipt of a written

Change Order".

If a change order affects the ability to achieve a contract milestone date,

both a prompt estimate and a time impact analysis are required for

negotiating the contract modification. Only execute change orders with

reservations regarding time and cost as a last resort.

Many change orders on the BRRTS Projects had reservations stating for

example that "this Change Order covers the cost of performing the extra

work. The extension of contract time and delay costs, if any, will be

handled" later. These clauses increase the likelihood of end-of-contract

claims.

INDEPENDENT ESTIMATES

Another consideration in negotiating changes is the preparation of

independent estimates by both the contractor and the owner. A

contractor would not even consider negotiating a change order without

preparing an estimate, and neither should the owner. During

negotiations, the differences between estimates (both cost and time)

should be reconciled at a sufficient level of detail that both the contractor

6

and the owner understand what is included in the change order, how

much it will cost and how much additional time will be granted. This

understanding should be clearly defined on the face of the change order

document.

LOSS OF PRODUCTIVITY

Agreeing on cost and time are easy, but how about loss of productivity?

What about the ripple effect; the impact of changes and delays on base

contract work? It is the contractor's responsibility to motivate the

workers and to assign specific tasks to be performed. It is also the

contractor's responsibility to provide adequate supervision to perform

both the base contract work and the changed work. If the contractor

receives notice of a change in sufficient time to replan, incorporating the

additional work in the current schedule without interrupting the

workflow on site, then there is no loss of productivity. The changed

work should appear as base contract work to the craftsmen in the field.

On the other hand, if notice of a change is received or an owner-caused

delay occurs which requires work on an activity to stop and/or one or

more crews to be reassigned, then a reasonable amount for the work

stoppage and reassignment including learning curve losses should be

included in the change order. Also, even though it is the contractor's

responsibility to provide adequate supervision, if a change or owner

delay requires additional supervision, the cost of the additional

supervision should be included in the change. Another potential extra

cost itemin a change or owner delay is the impact on weather sensitive

work (e.g., additional costs for hot or cold weather concreting).

COMPENSABLE DELAYS

If a change or owner delay impacts achieving the contract completion

date, the contractor is entitled to damages for delay in addition to the

other costs associated with the change. Typically these costs would

include (1) extended site overhead for both supervision and equipment,

and (2) unabsorbed home office overhead. It is imperative that these

costs be negotiated with the direct costs of the change order to avoid an

end-of-contract claim.

ACCELERATION

Acceleration is a special situation where the contractor is using

extraordinary measures to performmore quickly than originally planned.

Acceleration can have a severe impact on productivity in several areas

including:

$ Stacking of Trades - several trades (or crews) working

simultaneously in a confined work area

$ Crew Size Inefficiency - use of more men than the optimum

originally planned

$ Shift Turnover - performing the same activities by different crews

on multiple shifts

$ Overtime - working more than forty hours per week.

Since acceleration, particularly when it involves extended periods of

overtime, can have a devastating impact on production, with productivity

losses of 30 to 65 percent or more, it is of limited use in recovering lost

time.

Acceleration is particularly unsuited for regaining time lost by the

contractor. The BRRTS Contracts state that "If, in the opinion of the

Engineer, the Contractor falls significantly behind the approved progress

schedule, the Contractor shall take any and all steps necessary to improve

his progress. The Engineer, in this instance, may require the Contractor

to increase the number of shifts, initiate or increase overtime operations,

increase days of work in the work week, or increase the amount of

construction plant, or all of them". Similar provisions appear in most

contracts, but enforcing these provisions is rarely successful in making

up a significant amount of lost time. The owner must monitor the

contractor's performance and insure that the contractor has sufficient

manpower, material and equipment on site and is achieving his planned

rate of productivity before the contractor falls significantly behind

schedule, not after it.

Another problemwith directing the contractor to improve his progress is

that, if the contractor is not behind a properly adjusted schedule at the

time of the directive, he may be able to recover damages for constructive

acceleration. In Norair Engineering Corporation v. The United States,

666 F.2d 546 (1981), the Court stated, "in order to recover for increased

costs of acceleration under a changes clause, plaintiff must establish three

things:

(1) that any delays giving rise to the order were excusable,

(2) that the contractor was ordered to accelerate, and

(3) that the contractor in fact accelerated performance and incurred

extra costs."

If a change order is negotiated to recover time lost by the owner, make

sure that the risk is born by the contractor and that the change order

includes penalties if the promised schedule improvement is not achieved.

GOALS FOR FUTURE PROJECTS

A CHECKLIST FOR THE CONTRACTOR

1. Reread the contract and make sure you understand the provisions

for delays, changes and disputes.

2. Give the owner timely notice of any non-contractor caused delays

or changes which will require additional time and/or money to

performthe required scope of work.

3. Since delays must be measured against a base schedule to

establish entitlement to delay damages, insist on owner approval

of a detailed CPM schedule on every project and performmonthly

schedule updates to monitor job progress. Make sure you

understand the cause of any schedule slippage and take immediate

corrective action.

4. Submit time impact analyses to demonstrate entitlement to time

extensions. Incorporate the agreed upon subnetwork logic into the

next schedule update.

7

5. Remember the contractor's duty to mitigate (lessen) damages;

notify the owner of potential problems which may have cost or

schedule impact and recommend least cost solutions.

6. Put all notices and recommendations in writing and insist on

timely written responses fromthe owner.

7. Finally, when submitting an invoice, if the current contract

amount does not represent fair and adequate compensation to

perform the current scope of work by the current contract

completion date, request a change order to adjust the contract

amount and/or time of completion accordingly. Note, on each

invoice, the amount due for work performed on pending change

orders, and sit down with the owner to negotiate approved change

order amounts prior to the next invoice. If negotiations break

down, consider the use of an independent expert to mediate the

dispute.

A CHECKLIST FOR THE OWNER

$ Institute an effective quality control/quality assurance program,

and

$ Make sure the contractor follows his checklist.

CONCLUSION

The preparation and evaluation of claims have recently imposed

significant additional costs on both contractor and owner in today's

construction market. In order to stemthe growth in claims against the

owner, both the owner and his construction manager must develop new

techniques in managing construction.

A promising approach is to require each contractor to sign a statement

accompanying each invoice stating, "The amount billed to date is fair and

adequate compensation for the work performed, and the current contract

amount is fair and adequate compensation to performthe current scope

of work by the current contract completion date." Any exceptions to this

statement would be noted with the invoice. A claims manager,

representing the owner, would then try to negotiate a change order

amending the contract to cover the contractor's exception(s) prior to the

next invoice.

This procedure, requiring both the contractor and owner to evaluate and

attempt to settle claims monthly, would be a giant step toward

eliminating the multimillion-dollar end-of-project claims now so

prevalent. As an added benefit, both the contractor and owner become

intimately aware of their schedule responsibilities and cost exposure over

the life of the project.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- 1 Technical ProposalDocument64 pages1 Technical ProposalNana BarimaPas encore d'évaluation

- Annex I - 20160721 BoQ Car Park Refurbishment and Security Upgrade UN SiteDocument49 pagesAnnex I - 20160721 BoQ Car Park Refurbishment and Security Upgrade UN SiteSolomon AhimbisibwePas encore d'évaluation

- Project Management in Thermal Power Plant-Ntpc'S ExperienceDocument54 pagesProject Management in Thermal Power Plant-Ntpc'S ExperienceSam100% (2)

- Exhibit A-Scope of Work and Deliverables Project OverviewDocument6 pagesExhibit A-Scope of Work and Deliverables Project OverviewSai Uddiep GonapaPas encore d'évaluation

- 13 CPM Schedules CMR Ctdcs Master Show Hide NotesDocument14 pages13 CPM Schedules CMR Ctdcs Master Show Hide NotesIzo SeremPas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment 1 - Part BDocument14 pagesAssignment 1 - Part BRaju SubediPas encore d'évaluation

- Entergy Estimate - New 230 KV SubstationDocument8 pagesEntergy Estimate - New 230 KV SubstationSam WinstromPas encore d'évaluation

- CO-227-2012 Schedule of Annexs PDFDocument441 pagesCO-227-2012 Schedule of Annexs PDFKorupoluPas encore d'évaluation

- Approaches and MethodologyDocument10 pagesApproaches and MethodologyRobins MsowoyaPas encore d'évaluation

- RFP Arpa ExtractDocument13 pagesRFP Arpa Extractgauravreddy96774Pas encore d'évaluation

- Aer Concrete Mix DesignDocument256 pagesAer Concrete Mix DesignleimrabottPas encore d'évaluation

- Building A Microwave Network: Ten Key Points For All Project ManagersDocument5 pagesBuilding A Microwave Network: Ten Key Points For All Project ManagersNwamadi BedePas encore d'évaluation

- EPC March17 (Sanjay)Document37 pagesEPC March17 (Sanjay)Dundi Kumar T & D Dept.0% (1)

- Case Assignment No 3Document2 pagesCase Assignment No 3VikasPas encore d'évaluation

- Design & Construction of the Contract Package ConceptD'EverandDesign & Construction of the Contract Package ConceptPas encore d'évaluation

- Tor Quezon BridgeDocument14 pagesTor Quezon BridgeAnonymous H44U1h1DIPas encore d'évaluation

- MOT Civil Enginer QuestionsDocument14 pagesMOT Civil Enginer QuestionsRaja Umar JavaidPas encore d'évaluation

- CMGC Nomination Fact Sheet Dist 08-SBD-Rte 058 - (PM) Kern County 143.5/143.9&SBD 0/12.9 Project EA 34770Document6 pagesCMGC Nomination Fact Sheet Dist 08-SBD-Rte 058 - (PM) Kern County 143.5/143.9&SBD 0/12.9 Project EA 34770initiative1972Pas encore d'évaluation

- Standard ConstructionDrawings AllDocument126 pagesStandard ConstructionDrawings Allcipele12Pas encore d'évaluation

- Construction and MaintenanceDocument47 pagesConstruction and MaintenanceErickPas encore d'évaluation

- KBrown Course Project Week 1Document3 pagesKBrown Course Project Week 1Kyle BrownPas encore d'évaluation

- Enquiry For 400 KV Substation ConsultancyDocument14 pagesEnquiry For 400 KV Substation ConsultancyMahebob JilanPas encore d'évaluation

- Understanding Personnel FormartsDocument58 pagesUnderstanding Personnel FormartsMwesigwa DaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Hand Book SEWERAGE Sector Modified Final Print 14.02.11Document40 pagesHand Book SEWERAGE Sector Modified Final Print 14.02.11Syed AliPas encore d'évaluation

- Director of Operations or ConstructionDocument5 pagesDirector of Operations or Constructionapi-77744273Pas encore d'évaluation

- Eversource Underground Specs WmaDocument58 pagesEversource Underground Specs WmaPj EstokPas encore d'évaluation

- Lecture 2Document15 pagesLecture 2Animesh PalPas encore d'évaluation

- Tower Crane Planning and Liaison ProcessDocument30 pagesTower Crane Planning and Liaison ProcessArun VasanPas encore d'évaluation

- Micro-Surfacing Construction Inspection GuidelinesDocument12 pagesMicro-Surfacing Construction Inspection Guidelinesvinay rodePas encore d'évaluation

- Contracts Management Assignment COBSCQSCM191P-008Document7 pagesContracts Management Assignment COBSCQSCM191P-008Shashi PradeepPas encore d'évaluation

- General Civil Works MethodologyDocument3 pagesGeneral Civil Works Methodologykanika05Pas encore d'évaluation

- CDR Electrical EngineerDocument13 pagesCDR Electrical Engineerfh63775% (4)

- APTRANSCO Technical Reference Book 2011 Vol IIDocument381 pagesAPTRANSCO Technical Reference Book 2011 Vol IIsandip royPas encore d'évaluation

- Lessons LearnedDocument16 pagesLessons Learneddani2611Pas encore d'évaluation

- (01 32 16) Construction Schedule Critical Path Method-CPMDocument7 pages(01 32 16) Construction Schedule Critical Path Method-CPMAmeer JoshiPas encore d'évaluation

- Flyover Project ManagementDocument4 pagesFlyover Project ManagementSheikh Nouman Mohsin Ramzi50% (2)

- 276-Task Appreciation (For RD 256) Loyang Delpot - 1311!27!1Document5 pages276-Task Appreciation (For RD 256) Loyang Delpot - 1311!27!1alfiePas encore d'évaluation

- BD01-100-CN-PP-008 (Constructability Review and Construction Risk Assessment ProcedureDocument11 pagesBD01-100-CN-PP-008 (Constructability Review and Construction Risk Assessment Proceduresamer8saifPas encore d'évaluation

- Project Quality Plan: ContentDocument25 pagesProject Quality Plan: ContentAbd Rahim40% (5)

- Approach Paper PDFDocument38 pagesApproach Paper PDFMichael Benhura100% (1)

- Safety Officer Cv4Document5 pagesSafety Officer Cv4Muhammad RamzanPas encore d'évaluation

- Construction Contracts ManagementDocument7 pagesConstruction Contracts ManagementNihar ReddyPas encore d'évaluation

- DESIGN AND CONSTRUCTION PROGRESS DOCUMENTATION Rev.1Document12 pagesDESIGN AND CONSTRUCTION PROGRESS DOCUMENTATION Rev.1mohdPas encore d'évaluation

- 2200521lbc Supinfo Construction Method StatementDocument20 pages2200521lbc Supinfo Construction Method Statementstephen OdongoPas encore d'évaluation

- APTRANSCO Technical Reference Book 2011 Vol IIDocument381 pagesAPTRANSCO Technical Reference Book 2011 Vol IIKrish Arumuru100% (1)

- Project Start-Diary-Progress Report - Section3Document14 pagesProject Start-Diary-Progress Report - Section3Jaganmohan GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- MW PDFDocument6 pagesMW PDFSefineh KetemawPas encore d'évaluation

- Complete Notes of 18cv71Document152 pagesComplete Notes of 18cv711cf20at115Pas encore d'évaluation

- DanapurBIDDOC 11Document1 pageDanapurBIDDOC 11Prasenjit DeyPas encore d'évaluation

- Construction Schedule RequirementsDocument4 pagesConstruction Schedule Requirementsedla3710Pas encore d'évaluation

- Project Management For Procurement Management ModuleD'EverandProject Management For Procurement Management ModulePas encore d'évaluation

- Construction Supervision Qc + Hse Management in Practice: Quality Control, Ohs, and Environmental Performance Reference GuideD'EverandConstruction Supervision Qc + Hse Management in Practice: Quality Control, Ohs, and Environmental Performance Reference GuideÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (2)

- Textbook of Urgent Care Management: Chapter 4, Building Out Your Urgent Care CenterD'EverandTextbook of Urgent Care Management: Chapter 4, Building Out Your Urgent Care CenterPas encore d'évaluation

- Contracts, Biddings and Tender:Rule of ThumbD'EverandContracts, Biddings and Tender:Rule of ThumbÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- Guide to Performance-Based Road Maintenance ContractsD'EverandGuide to Performance-Based Road Maintenance ContractsPas encore d'évaluation

- Handbook on Construction Techniques: A Practical Field Review of Environmental Impacts in Power Transmission/Distribution, Run-of-River Hydropower and Solar Photovoltaic Power Generation ProjectsD'EverandHandbook on Construction Techniques: A Practical Field Review of Environmental Impacts in Power Transmission/Distribution, Run-of-River Hydropower and Solar Photovoltaic Power Generation ProjectsÉvaluation : 2 sur 5 étoiles2/5 (1)

- Well Testing Project Management: Onshore and Offshore OperationsD'EverandWell Testing Project Management: Onshore and Offshore OperationsPas encore d'évaluation

- Integrated Project Planning and Construction Based on ResultsD'EverandIntegrated Project Planning and Construction Based on ResultsPas encore d'évaluation

- Contract Management GuidelinesDocument58 pagesContract Management Guidelinestigervg100% (1)

- Astm A325Document3 pagesAstm A325Mohammed 3014Pas encore d'évaluation

- HR Management - PMPNotesDocument10 pagesHR Management - PMPNotesMohammed 3014Pas encore d'évaluation

- ElbowDocument1 pageElbowMohammed 3014Pas encore d'évaluation

- CaptureDocument1 pageCaptureMohammed 3014Pas encore d'évaluation

- S141MDocument1 pageS141MMohammed 3014Pas encore d'évaluation

- CHQDocument1 pageCHQMohammed 3014Pas encore d'évaluation

- Pmbok 5th Edition MindmapDocument34 pagesPmbok 5th Edition MindmapMohammed 3014100% (6)

- IndraDocument1 pageIndraMohammed 3014Pas encore d'évaluation

- BieceDocument1 pageBieceMohammed 3014Pas encore d'évaluation

- PL12X325 X 502: 1 PROJ-NUM-4LO-15 No Item MKD'Document1 pagePL12X325 X 502: 1 PROJ-NUM-4LO-15 No Item MKD'Mohammed 3014Pas encore d'évaluation

- Circular Steel ColumnsDocument1 pageCircular Steel ColumnsMohammed 3014Pas encore d'évaluation

- Structural Steel Framing SolutionsDocument17 pagesStructural Steel Framing Solutionsuhu_plus6482Pas encore d'évaluation

- 10 MMDocument1 page10 MMMohammed 3014Pas encore d'évaluation

- Steel Insight 2Document7 pagesSteel Insight 2cblerPas encore d'évaluation

- IndraDocument1 pageIndraMohammed 3014Pas encore d'évaluation

- PIP - STD - STS05130 Struct Erection 2-2002Document11 pagesPIP - STD - STS05130 Struct Erection 2-2002John ClaytonPas encore d'évaluation

- G.R. No. 134239 May 26, 2005Document22 pagesG.R. No. 134239 May 26, 2005Nicole HinanayPas encore d'évaluation

- Kauffman v. PNBDocument2 pagesKauffman v. PNBReymart-Vin MagulianoPas encore d'évaluation

- Hodge v. GarrettDocument2 pagesHodge v. GarrettGabe Ruaro100% (2)

- L 1 Sales ActDocument16 pagesL 1 Sales ActIshuPas encore d'évaluation

- Article 1169 - Causing vs. BencerDocument2 pagesArticle 1169 - Causing vs. BencerDane Figuracion100% (3)

- All MCQSDocument302 pagesAll MCQSWaqar JuttPas encore d'évaluation

- OMMC (Amendment) 2014 PDFDocument14 pagesOMMC (Amendment) 2014 PDFsenhcirclesouth berhampurPas encore d'évaluation

- Gallery Exhibition Contract 1Document1 pageGallery Exhibition Contract 1api-275646456Pas encore d'évaluation

- Sample Logo ContractDocument1 pageSample Logo ContractjitheshprakahPas encore d'évaluation

- 1207 1225Document8 pages1207 1225Dan DiPas encore d'évaluation

- Cba CaseDocument31 pagesCba CasefullpizzaPas encore d'évaluation

- Snapdeal AgreementDocument4 pagesSnapdeal AgreementRajendra Jena33% (3)

- Labrev Cases 6Document47 pagesLabrev Cases 6Alelie BatinoPas encore d'évaluation

- Aldaba v. CareerDocument14 pagesAldaba v. CareerTibsPas encore d'évaluation

- Long Term Construction Contract Quiz2020Document10 pagesLong Term Construction Contract Quiz2020Riza Mae AlcePas encore d'évaluation

- Lecture 2 Intention To Create Legal RelationsDocument21 pagesLecture 2 Intention To Create Legal RelationsCathrina de CrabbyPas encore d'évaluation

- Terms Conditions Kalpataru 26TH May 2017Document6 pagesTerms Conditions Kalpataru 26TH May 2017Etrans 9Pas encore d'évaluation

- Law On Obligations and Contracts : General Provisions Part 1Document30 pagesLaw On Obligations and Contracts : General Provisions Part 1Jobelle Grace SorianoPas encore d'évaluation

- I-04 Florentino V PNBDocument1 pageI-04 Florentino V PNBG SPas encore d'évaluation

- Topic 3: Market Equilibrium & Market ApplicationDocument28 pagesTopic 3: Market Equilibrium & Market ApplicationHasdanPas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment 3 M Waleed BBFE-17-05Document4 pagesAssignment 3 M Waleed BBFE-17-05Waleed MalikPas encore d'évaluation

- UnpaidWork CompleteReport-2013Document382 pagesUnpaidWork CompleteReport-2013agikePas encore d'évaluation

- Semester Paper CostDocument4 pagesSemester Paper CostMd HussainPas encore d'évaluation

- FIDIC "Fédération Internationale Des Ingénieurs - Conseils" CLAUSE 1 ExplainedDocument6 pagesFIDIC "Fédération Internationale Des Ingénieurs - Conseils" CLAUSE 1 ExplainedMJBPas encore d'évaluation

- Section A: Miaqe September 2014 Scheme Set 1 Suggested AnswersDocument12 pagesSection A: Miaqe September 2014 Scheme Set 1 Suggested AnswersPraveena RaviPas encore d'évaluation

- Legal Room Rental AgreementDocument6 pagesLegal Room Rental AgreementMolly ClarkPas encore d'évaluation

- Taurus Taxi vs. Capital InsuranceDocument2 pagesTaurus Taxi vs. Capital Insuranceviva_33Pas encore d'évaluation

- FAR Diagnostic ExamDocument7 pagesFAR Diagnostic ExamDaniel Huet0% (1)

- Compiled Notes I NegoDocument16 pagesCompiled Notes I NegoDeanne ViPas encore d'évaluation

- Worksheet 4 - Consideration 2020Document9 pagesWorksheet 4 - Consideration 2020Niasha ThompsonPas encore d'évaluation